Abstract

This paper presents a self-contained powered knee and ankle prosthesis, intended to enhance the mobility of transfemoral amputees. A finite-state based impedance control approach, previously developed by the authors, is used for the control of the prosthesis during walking and standing. Experiments on an amputee subject for level treadmill and overground walking are described. Knee and ankle joint angle, torque, and power data taken during walking experiments at various speeds demonstrate the ability of the prosthesis to provide a functional gait that is representative of normal gait biomechanics. Measurements from the battery during level overground walking indicate that the self-contained device can provide more than 4500 strides, or 9 km, of walking at a speed of 5.1 km/h between battery charges.

Index Terms: Biomechatronics, gait analysis, impedance control, mechanical system design, powered prosthesis

I. INTRODUCTION

There are more than 300 000 transfemoral amputees in the United States [1] (i.e., an incidence of approximately one per thousand people), with 30 000 new transfemoral amputations conducted each year [2]. If similar trends hold across the world population, then one would expect approximately 7 million transfemoral amputees worldwide. One of the most significant limitations of current prosthetic technology is the inability to provide net power at the joints. This loss of net power generation at the lower limb impairs the ability of the prosthesis to restore biomechanically normal locomotive function during many locomotive activities, including level walking, walking up stairs and slopes, running, and jumping [3]–[10]. In the absence of net power generation at the knee and ankle, transfemoral amputees with passive prostheses have been shown to expend up to 60% more metabolic energy [11] and exert three times the affected-side hip power and torque [9] when compared to healthy subjects during level walking. It is the hypothesis of this work that an actively powered knee and ankle prosthesis with the capability of generating human-scale net positive power over a gait cycle will provide improved functional restoration relative to passive prostheses.

Some of the earliest work in powered transfemoral prostheses was conducted during 1970s and 1980s and is described in [12]–[18]. Specifically, an electrohydraulically actuated knee joint, which was tethered to a hydraulic power source and utilized off-board electronics and computation, was developed and tested on at least one amputee subject. As described in [16], an “echo control” scheme was developed for gait control. In this control approach, the modified knee trajectory from the sound leg was used as a desired knee joint angle trajectory on the contralateral side. Other prior work [19] reported the development of an active knee joint actuated by dc motors that utilized a finite-state knee controller with robust position tracking for gait control. Ossur, a prosthetics company, has recently introduced the “Power Knee” that uses a control approach, which like echo control, utilizes sensors on the sound leg to prescribe a trajectory for the knee joint of the prosthesis [20]. Martinez-Villalpando et al. [21], present a prosthesis with an agonist–antagonist knee, which is intended to restore knee function via biomimetic actuation.

Work in powered transtibial prostheses includes [22], which describes the design of an active ankle joint using McKibben pneumatic actuators. Ossur has also introduced a “powered” ankle prosthesis, called the “Proprio Foot,” which does not contribute net power to gait, but rather dorsiflexes the ankle angle during swing to avoid stumbling and during sitting to better accommodate a sitting posture [23]. Bellman et al. describe an active robotic ankle prosthesis with actuated DOFs in both the sagittal and frontal planes [24]. Au and Herr built a powered ankle–foot prosthesis that incorporates both parallel and series elasticity to reduce peak motor torque and power requirements and to provide a more suitable output impedance [25].

Unlike any of the aforementioned prior works, this paper describes a transfemoral prosthesis with both a powered knee and ankle. Note that, as described by Sup et al. [26], the authors have previously developed a pneumatically powered knee and ankle prosthesis prototype, which was designed to leverage recent advances in monopropellant based pneumatic actuation described in [27]–[30]. Despite this, the authors believe that the monopropellant technology in its current state is not ready for commercialization in the near-term. In order to provide a technology that is more appropriate for near-term use, the authors describe in this paper a powered knee and ankle prosthesis powered by a lithium-polymer battery. Such batteries have an energy density approaching 200 W·h/kg [31], which as described herein, enables the development of a transfemoral prosthesis with a reasonable weight and an acceptable, although limited, range of locomotion. The energy density of such batteries is expected to nearly double in the next decade (driven largely by the automotive industry’s needs for electrical vehicles) [31], which will provide a significantly improved range of locomotion. Prior to developing the self-contained, battery-powered active knee and ankle prosthesis described herein, Sup et al. [32] previously built a tethered, electrically powered knee and ankle prototype to explore the electrical power requirements of such a device.

Based on this preliminary work, the authors have developed an electrically powered self-contained active knee and ankle prosthesis, which is described herein. The self-contained prosthesis generates human-scale power at the joints and incorporates a torque-based control framework for stable and coordinated interaction between the prosthesis and the user. This paper describes the mechanical and electrical design of the prosthesis, provides an overview of the finite-state-based impedance control framework for walking and standing, presents experimental results on a single transfemoral amputee subject, and discusses the electrical power requirements in different activity modes. A video is included in the supplemental material that qualitatively conveys the performance of the approach.

II. PROSTHESIS DESIGN

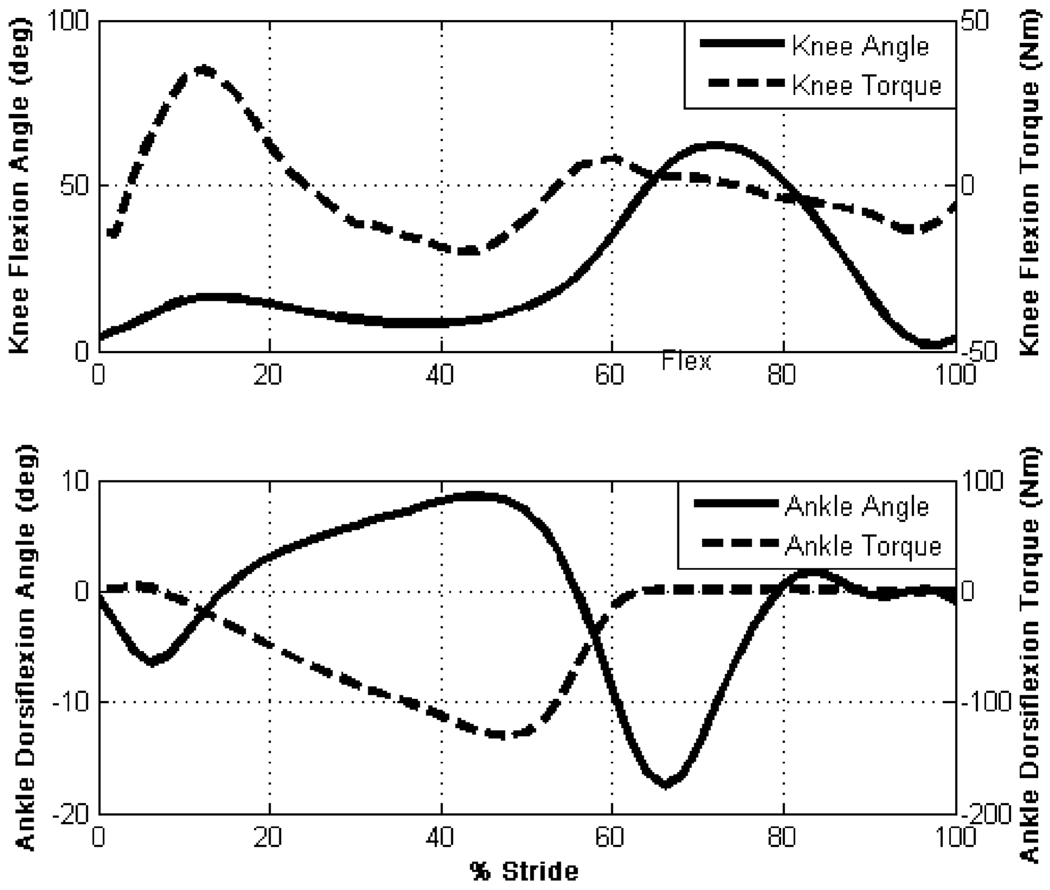

The joint torque specifications required of the knee and ankle joints were based on an 85 kg user for a walking cadence of 80 steps/min (see Fig. 1) and stair climbing, as derived from body-mass-normalized data [8], [9], while the joint power specifications were based on data from Winter [9], also for an 85 kg user. The design specifications are summarized in Table I. The resulting self-contained powered knee and ankle prosthesis is shown in Fig. 2. A detailed discussion of the mechanical, sensor and embedded system design is given in the following sections.

Fig. 1.

Normal biomechanical gait data for an 85 kg subject walking at a cadence of 80 steps/min [9].

TABLE I.

Design Specifications

| Specification | Value |

|---|---|

| Knee Range of Motion | 0° to 120° |

| Ankle Range of Motion | −45° to 20° |

| Maximum Knee Torque | 75 Nm |

| Maximum Ankle Torque | 130 Nm |

| Peak Knee Power | 150 W |

| Peak Ankle Power | 250 W |

| Knee centre High Adjustability | 0.45 m to 0.58 m |

| Maximum Total Weight | 4.5 kg |

| Minimum Factor of safety | 2 |

Fig. 2.

Self-contained powered knee and ankle transfemoral prosthesis: (left) front and (right) side views.

A. Mechanical Design

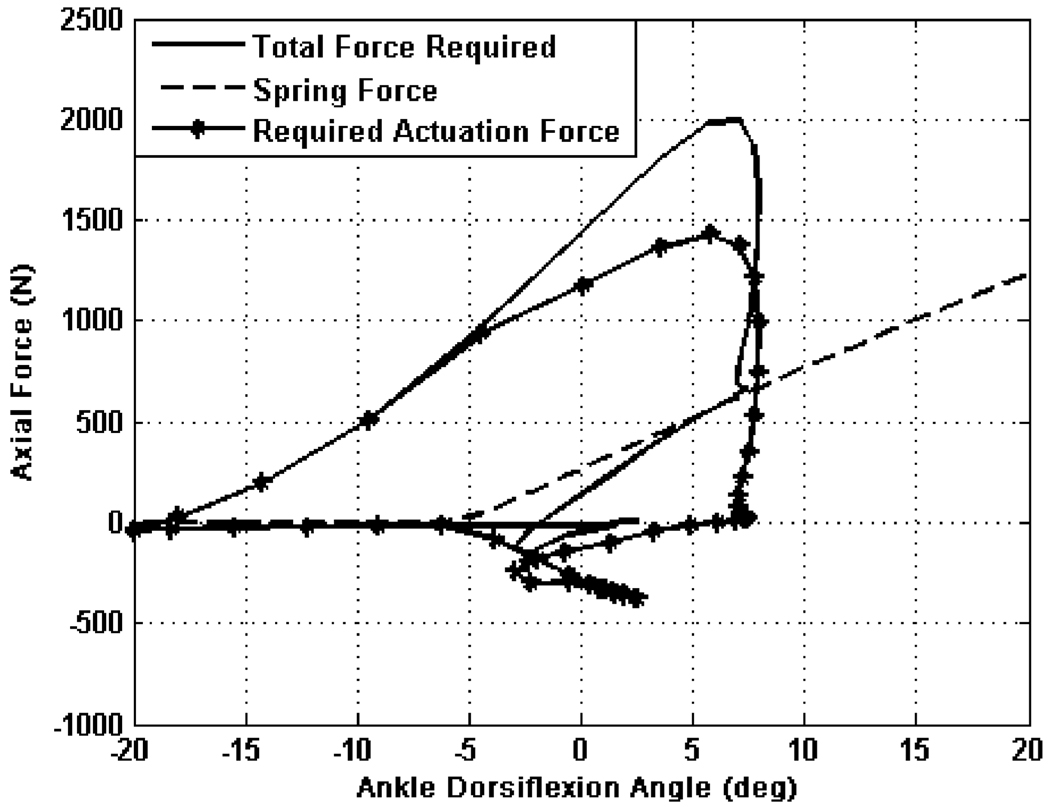

Actuation for the prosthesis is provided by two motor-driven ball screw assemblies that drive the knee and ankle joints, respectively, through a slider–crank linkage. The prosthesis is capable of 120° of flexion at the knee and 45° of planterflexion and 20° of dorsiflexion at the ankle. Each actuation unit consists of a Maxon EC30 Powermax brushless motor capable of producing 200 W of continuous power and intermittently capable of more. The motor is connected to a 12-mm diameter ball screw with 2 mm pitch, via helical shaft couplings. The ankle actuation unit additionally incorporates a 302 stainless steel spring (51 mm free length and 35 mm outer diameter), with three active coils and a stiffness of 385 N/cm in parallel with the ball screw. The purpose of the spring is to bias the motor’s axial force output toward ankle plantarflexion, and to supplement power output during ankle push off. The stiffness of the spring was chosen to allow for peak force output without limiting the range of motion at the ankle. The resulting axial actuation unit’s force versus ankle angle plot (see Fig. 3) graphically demonstrates for walking the reduction in linear force output supplied by the motor at the ankle through the addition of the spring. Note that the compression spring does not engage until approximately 5° of ankle plantarflexion.

Fig. 3.

Reduction of linear force output required by the ankle motor unit by the addition of a spring in parallel for walking at 120 steps/min, taken from averaged normal biomechanical data [9]. Note that the spring is engaged at −5° and achieves a peak spring force of 620 N at 7°

Each actuation unit includes a uniaxial load cell (Measurement Specialties ELPF-500L), positioned in series with the actuation unit for closed loop force control of the motor/ballscrew unit. Both the knee and ankle joints incorporate bronze bearings and, for joint angle measurement, integrated precision potentiometers (ALPS RDC503013). A strain-based sagittal plane moment sensor (see Fig. 4) is located between the knee joint and the socket connector, which measures the moment between the socket and prosthesis. The ankle joint connects to a custom foot design (see Fig. 5), which incorporates strain gages to measure the ground reaction forces on the ball of the foot and on the heel. The central hollow structure of the prosthesis houses a lithium-polymer battery and provides an attachment point for the embedded system hardware. To better fit within an anthropomorphic envelope, the ankle joint is placed slightly anterior to the centerline of the central structure.

Fig. 4.

Sagittal moment load cell: top and bottom views.

Fig. 5.

Sensorized prosthetic foot with and without strain gage covers.

The length of the shank segment is varied by changing the length of three components: the lower shank extension, the spring pull-down, and the coupler between the ball nut and ankle. Additional adjustability is provided by the pyramid connector that is integrated into the sagittal moment load cell for coupling the prosthesis to the socket (as is standard in commercial transfemoral prostheses). The structure of the prosthesis was fabricated from 7075 aluminum. The total mass of the self-contained device is 4.2 kg, which is within an acceptable range for transfemoral prostheses, and comparable to a normal limb segment [33]. A weight breakdown of the device is presented in Table II.

TABLE II.

Mass Breakdown of Self-Contained Powered Prosthesis

| Component | Mass (kg) | Mass Distribution |

|---|---|---|

| Structure | 0.90 | 21% |

| Ankle Motor Assembly | 0.89 | 21% |

| Knee Motor Assembly | 0.72 | 17% |

| Battery | 0.62 | 15% |

| Electronics | 0.36 | 9% |

| Sensorized Foot | 0.35 | 8% |

| Foot Shell | 0.24 | 6% |

| Sagittal Moment Sensor | 0.12 | 3% |

| Total | 4.20 | 100% |

B. Moment and Force Sensing

The sagittal plane moment between the user and prosthesis, and the force between the prosthesis and ground is sensed in order to infer user intent and coordinate prosthesis control. Based on biomechanical data [8], [9], the required range of measurements was determined to be 100 N·m of sagittal plane moment and a ground reaction force of 1000 N. The sagittal plane moment is measured above the knee joint at the socket interface and the ground reaction force is measured by the custom foot. The location of the sensors was chosen to avoid coupling the desired measured ground reaction force and sagittal moment with the joint torques. In addition, incorporating the ground reaction load cell into the structure of a custom foot eliminates the added weight of a separate load cell, and also enables separate measurement of the heel and ball of foot load.

The sagittal plane moment sensor, as shown in Fig. 4, is designed to have a low profile in order to accommodate longer residual limbs. The sensor incorporates a full bridge of semi-conductor strain gages that measure the strains generated by the sagittal plane moment. Finite-element analysis, using ProEngineer Mechanica, was used to minimize the overall design height and to achieve the desired strains in the load cell. The sensor is fabricated from 7075 aluminum and has an assembled weight of 120 g including the stainless steel pyramid connector. The overall height of the sensor including the pyramid connector is 32 mm, with a rectangular base of 78 mm × 44 mm. The device was calibrated for a measurement range of 100 N·m, and exhibited linearity within ±5% error over the full-scale output.

The custom foot, as shown in Fig. 5, was designed to measure the ground reaction force components at the ball of the foot and heel. The foot is comprised of heel and toe beams, rigidly attached to a central fixture and arranged as cantilever beams with an arch that allows for the load to be localized at the heel and ball of the foot, respectively. Each heel and toe beam incorporates a full bridge of semiconductor strain gages that measure the strains resulting from the respective ground contact forces. The foot utilized for the tests described herein measures 220 mm long, 56 mm wide, and is 35 mm tall to the top of the central fixture, and approximates a U.S. size 12 ft or EU size 46 ft. The foot is fabricated from 7075 aluminum and weighs 350 g. The dimensions and weight are similar to commercial low-profile carbon-fiber prosthetic feet, such as the Otto Bock Lo-Rider. The prosthetic foot was designed to be housed in a soft prosthetic foot shell, as shown in Fig. 2. The heel and ball of foot load sensors were calibrated for a measurement range of 1000 N, and demonstrated linearity within ±4% error for the full-scale output range.

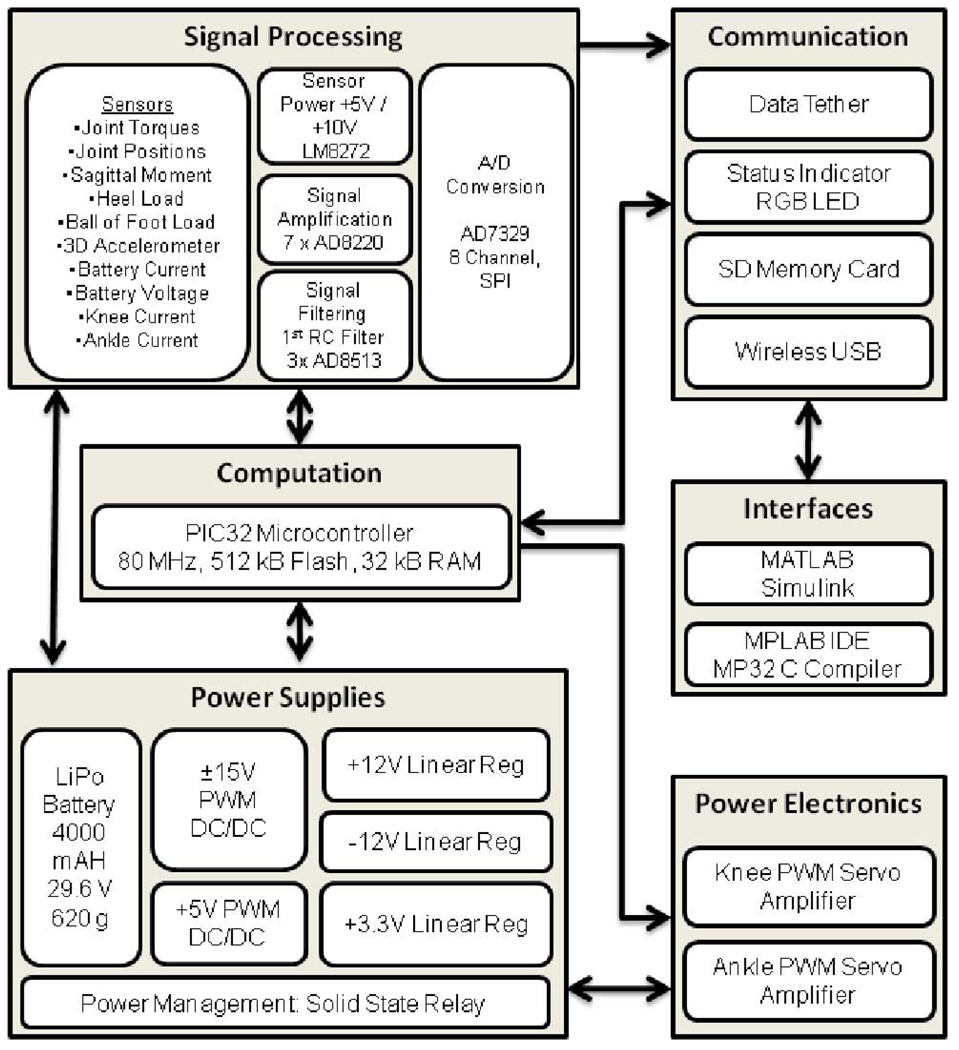

C. Embedded System

The powered prosthesis contains an embedded microcontroller that allows for either tethered or untethered operation. The embedded system consists of signal processing, power supply, power electronics, communications, and computation modules (see Fig. 6). The system is powered by a lithium polymer battery with 29.6 V nominal rating and 4000 mA·h capacity. The signal electronics require ±12 and +3.3 V, which are provided via linear regulators to maintain low noise levels. For efficiency, the battery voltage is reduced by pulsewidth-modulated (PWM) switching amplifiers to ±15 and +5 V prior to using the linear regulators. The power can be disconnected via a microcontroller that controls a solid-state relay. The power status is indicated by LED status indicators controlled also by the microcontroller.

Fig. 6.

Embedded system framework.

The analog sensor signals acquired by the embedded system include the prosthesis sensors signals (five strain gage signals and two potentiometer signals), analog reference signals from the laptop computer used for tethered operation, and signals measured on the board including battery current and voltage, knee and ankle servoamplifier currents and a three-axis accelerometer. The prosthesis sensor signals are conditioned using input instrumentation amplifiers (AD8220) over a range of ±10 V. The battery, knee motor and ankle motor currents are measured by current sensing across 0.02 Ohm resistors and via current sensing amplifiers (LT1787HV). The signals are filtered with a first-order RC filter with 1.6 kHz cut off frequency for the commercial load cells and joint angles and 160 Hz cutoff frequency for the sagittal moment, heel and ball of foot custom load cells and buffered with high slew rate amplifiers before the analog-to-digital conversion stage. Analog-to-digital conversion is accomplished by two 8-channel analog-to-digital converters (AD7329). The analog-to-digital conversion data are transferred to the microcontroller via serial peripheral interface (SPI) bus.

The main computational element of the embedded system is an 80 MHz PIC32 microcontroller with 512 kB flash memory and 32 kB RAM, which consumes approximately 400 mW of power. The microcontroller is programmed in C using MPLAB IDE and MP32 C Compiler. In addition to untethered operation, the prosthesis can also be controlled via a tether by a laptop computer running MATLAB Simulink RealTime Workshop. In the untethered operation state, the microcontroller performs the middle- and low-level controllers of the prosthesis at each sample time (1 ms) and data logging at every 5 ms. In the tethered operation state, the microcontroller drives the servoamplifiers based on analog reference signals from the laptop computer. A 1 GB memory card is used for logging time-stamped data acquired from the sensors and recording internal controller information. The memory card is interfaced to the computer via wireless USB protocol. The microcontroller sends PWM reference signals to two four quadrant brushless dc-motor drivers (Advanced Motion Control AZBDC20A8) rated at 12 A continuous and 20 A peak current output with regenerative capabilities in the second and fourth quadrants of the velocity/torque curve.

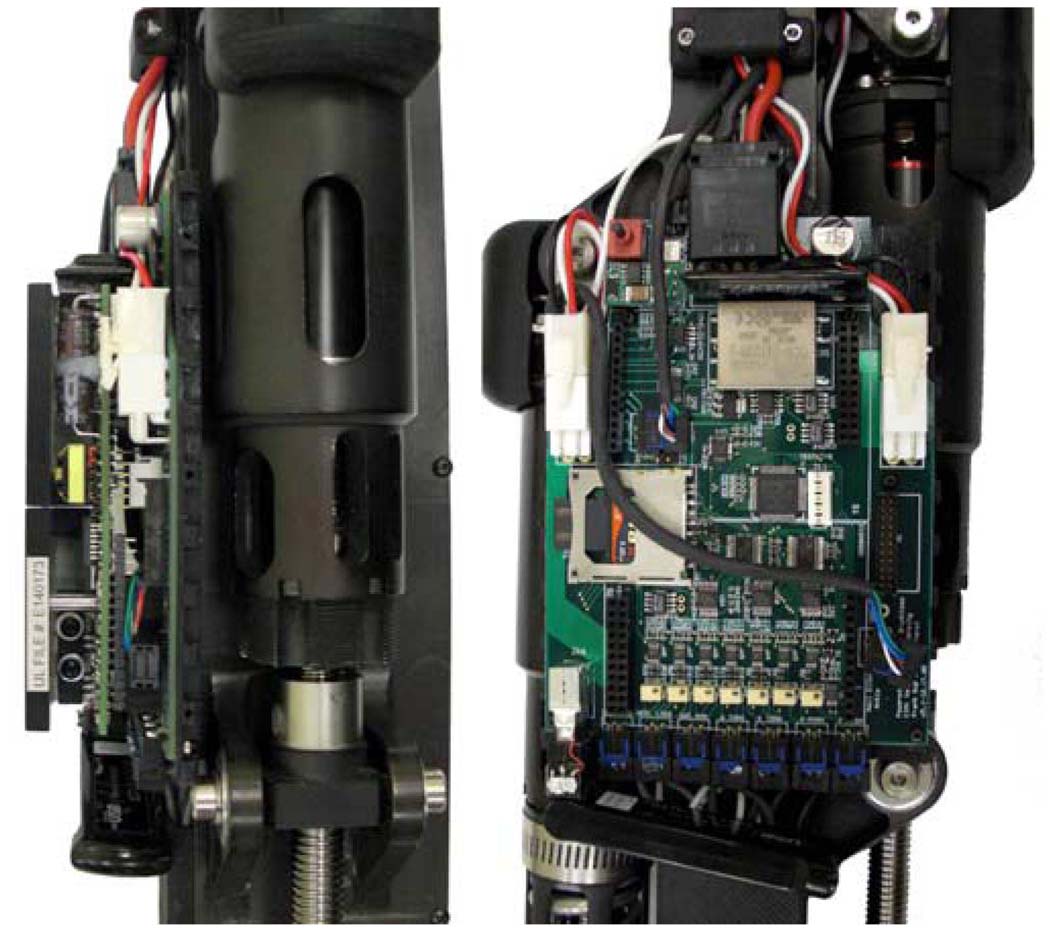

The embedded system printed circuit board is a 130 mm × 90 mm four-layer board designed for surface mount technology (SMT) components. To further reduce the footprint of the board, the removable servoamplifiers were raised to allow for the placement of components underneath, as shown in Fig. 7. The mass of the embedded system is 0.36 kg, which consists of the board and components (0.10 kg), servoamplifiers (0.19 kg), and protective cover (0.07 kg).

Fig. 7.

Embedded system hardware (left) with and (right) without servoamplifiers.

D. Control

The general control architecture of the prosthesis consists of three levels, as diagrammed in Fig. 8. The high-level supervisory controller, which is the intent recognizer, infers the user’s intent based on the interaction between the user and the prosthesis, and switches the middle-level controllers appropriately. Intent recognition is achieved by first generating a database containing sensor data from different activity modes and training a pattern recognizer that switches between activity modes in real time, as described in [34]. A middle-level controller is developed for each activity mode, such as walking, standing, sitting, and stair ascent/descent. The middle-level controllers generate torque references for the joints using a finite-state machine that modulates the impedance of the joints depending on the phase of the gait. The low-level controllers are the closed-loop joint torque controllers, which compensate for the transmission dynamics of the ball screw (i.e., primarily friction and inertia), and thus, enable tracking of the knee and ankle joint torque references (commanded by the middle-level controllers) with a higher bandwidth and accuracy than is afforded with an open-loop torque control approach.

Fig. 8.

Complete control architecture showing high, middle, and low levels.

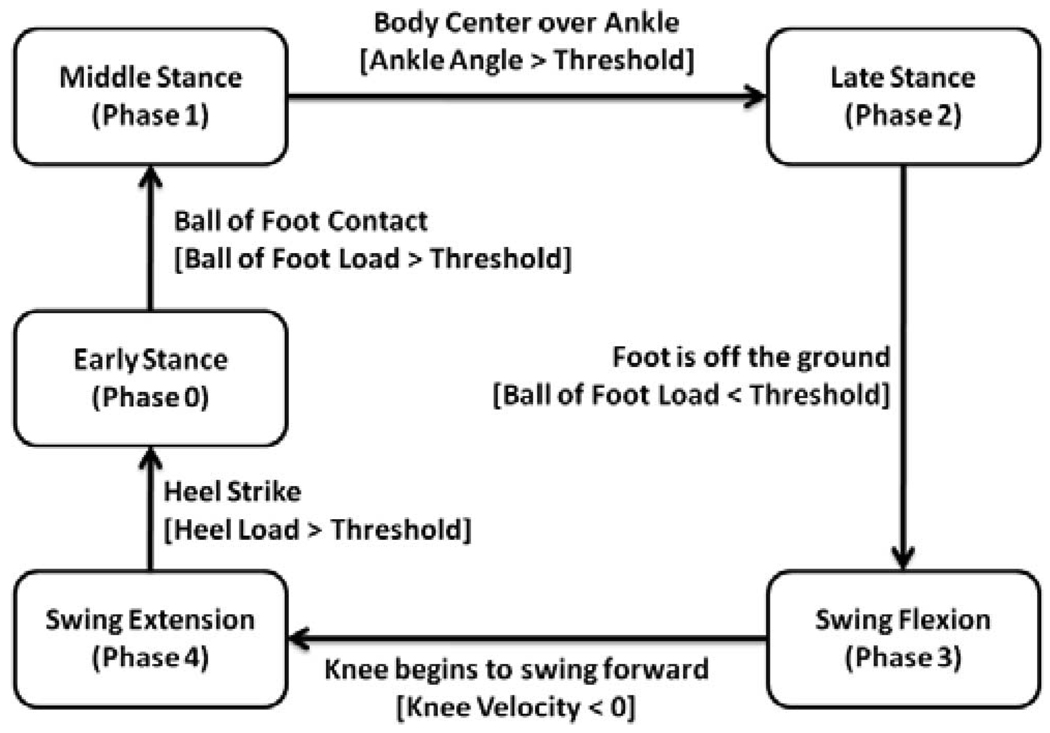

The finite-state impedance control developed by the authors utilizes an impedance-based approach to generate joint torques [26]. The joint torques for each activity mode, such as walking, standing, sitting, stair ascent/descent, are governed by separate finite-state machines, which modulate the joint impedance according to the phase of gait. The finite-state machines for walking and standing are diagrammed in Fig. 9 and Fig. 10, respectively. The state model for walking is described by five phases, three of which are stance phases (early stance, middle stance, and late stance) and two of which are swing phases (swing knee flexion and swing knee extension). The standing state model is described by two phases, which are a weight-bearing phase and a nonweight-bearing phase. Note that the distinction between torque commands and position commands is largely one of output impedance, i.e., accurate tracking of position trajectories requires a high joint output impedance, which is not characteristic of human gait. By generating torque trajectories rather than position trajectories, the output impedance of each joint can be more closely matched to the native limb, thus enabling the user to interact with the prosthesis by leveraging its dynamics in a manner similar to normal gait. In other words, the resulting motion of each prosthesis joint is due to the combination of the user input and the prosthesis input, rather than resulting from the prosthesis input alone (as would be the case with a position-based controller). In each phase, the knee and ankle torques, τi, are each described by a passive spring and damper with a fixed equilibrium point, given by

| (1) |

where ki, bi, and θki denote the linear stiffness, damping coefficient, and equilibrium point, respectively, for the ith state. Energy is delivered to the user by switching between appropriate equilibrium points (of the virtual springs) during transitions between phases. In this manner, the prosthesis is guaranteed to be passive within each phase, and thus, generates power simply by switching between phases. Since the user initiates phase switching, the result is a predictable controller that, barring phase switching input from the user, will always default to passive behavior.

Fig. 9.

Finite-state machine for level walking. Blocks represent states and arrows represent the corresponding transitions.

Fig. 10.

Finite-state machine for level standing. Blocks represent states and arrows represent the corresponding transitions.

III. EXPERIMENTS

The powered prosthesis was tested on a 20-year-old male (1.93 m, 75 kg) unilateral amputee three years post amputation. A photograph of the transfemoral amputee wearing the prosthesis is shown in Fig. 11. The length of the test subject’s residual limb measured from the greater trochanter to the amputated site was 55% of the length of the nonimpaired side measured from the greater trochanter to the lateral epicondyle. The subject uses an Otto Bock C-leg with a Freedom Renegade prosthetic foot for daily use. For testing of the powered prosthesis prototype, the subject’s daily-use socket was used, with the height and varus–valgus alignment of the prosthesis adjusted for the initial trial by a licensed prosthetist.

Fig. 11.

Unilateral transfemoral amputee test subject used for the powered prosthesis evaluation.

A. Parameter Tuning

Experiments were performed to characterize the knee and ankle joint angles, torques, and power while walking over ground at a self-selected walking speed, and also to characterize the system’s electrical power consumption, mechanical power generation, and efficiency. In order to conduct the overground characterization, a series of experiments were required to parameterize the middle-level controller to the subject at various walking cadences. The controller parameterization was conducted on a treadmill at three walking cadences. The nominal cadence used for parameter tuning was the subject’s self-selected cadence while wearing his daily-use prosthesis. For overground walking, the subject walked comfortably with his daily use (passive) prosthesis at 90 steps/min at 4.1 km/h. For treadmill walking, the speed indicator on the treadmill was covered and the subject adjusted the treadmill speed until he felt comfortable. The self-selected normal cadence of the subject was determined to be 75 steps/min at 2.8 km/h. Fast and slow cadences were set at ±15% of the normal treadmill cadence resulting in treadmill speeds of 2.2 and 3.4 km/h, respectively. The middle-level control parameters of the powered prosthesis were then tuned (with the prosthesis controlled in the tethered state) while walking on the treadmill at slow, normal and fast walking cadences (as determined by the daily use prosthesis), and also for standing. During the standing mode, the test subject alternately shifted his weight between limbs, turned in place, and stood still. Note that in all cases, the parameters were tuned using a combination of feedback from the user, and from visual inspection of the joint angle, torque, and power data. Note also that the tethered operating mode was utilized during treadmill parameter tuning because it enables quick and easy parameter variation and data visualization, and thus, greatly expedites the iterative parameter tuning process. The resulting middle-level controller parameters of the tuned impedance functions for standing and for the various walking cadences are listed in Table III and Table IV.

TABLE III.

Impedance Parameters for Treadmill Walking From Experimental Tuning

| Knee Impedance | Ankle Impedance | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speed km h−1 |

k Nm deg−1 |

b N s m−1 |

θk deg |

k Nm deg−1 |

b N s m−1 |

θk deg |

|

| 0 | 2.2 | 2.5 | 0.05 | 8 | 3.0 | 0.04 | −1 |

| 2.8 | 2.5 | 0.05 | 10 | 3.0 | 0.04 | −1 | |

| 3.4 | 2.5 | 0.05 | 10 | 3.0 | 0.04 | −1 | |

| 1 | 2.2 | 4.0 | 0.06 | 6 | 5.0 | 0.04 | 0 |

| 2.8 | 5.0 | 0.06 | 6 | 5.0 | 0.04 | 0 | |

| 3.4 | 5.0 | 0.06 | 6 | 5.0 | 0.04 | 0 | |

| 2 | 2.2 | 3.0 | 0.02 | 14 | 4.0 | 0.01 | −16 |

| 2.8 | 3.5 | 0.02 | 14 | 5.0 | 0.01 | −16 | |

| 3.4 | 5.0 | 0.02 | 14 | 5.0 | 0.01 | −16 | |

| 3 | 2.2 | 0.15 | 0.02 | 65 | 0.4 | 0.05 | 0 |

| 2.8 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 65 | 0.4 | 0.05 | 0 | |

| 3.4 | 0.10 | 0.01 | 65 | 0.4 | 0.05 | 0 | |

| 4 | 2.2 | 0.10 | 0.03 | 40 | 0.7 | 0.03 | 0 |

| 2.8 | 0.20 | 0.03 | 40 | 0.7 | 0.03 | 0 | |

| 3.4 | 0.25 | 0.03 | 40 | 0.7 | 0.03 | 0 | |

Highlighted parameters vary with walking speed.

TABLE IV.

Impedance Parameters for Standing From Experimental Tuning

| Knee Impedance | Ankle Impedance | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase |

k Nm deg−1 |

b N s m−1 |

θk deg−1 |

k Nm deg −1 |

b N s m −1 |

θk deg |

| 0 | 2.5 | 0.02 | 0 | 4.0 | 0.05 | −6 |

| 1 | 0 | 0.02 | 0 | 2.0 | 0.05 | −6 |

The measured joint angles from the prosthesis’ on-board sensors during level treadmill walking at cadences of 64, 75, and 87 steps/min are shown in Fig. 12. In comparing the knee and ankle angles to prototypical data from normal subject (see Fig. 1), one can observe that the powered prosthesis and controller provide knee and ankle joint angle profiles quite similar to those observed during normal gait. The ability of the device to provide stance flexion provides cushioning at heel strike and reduces the rise of the body’s center of mass to allow for more efficient gait [35]. A video from these trails is included in the supplemental material.

Fig. 12.

Measured joint angles of the powered prosthesis for ten consecutive gait cycles of treadmill walking at slow, normal, and fast cadences, 64, 75, and 86 steps/min, respectively.

B. Overground Walking

Once the middle-level controllers were fully parameterized for standing and slow, medium (i.e., self-selected), and fast cadences, the prosthesis was switched to the untethered operating mode, so that the subject could walk overground with the fully self-contained prosthesis (i.e., without a tether hindering movement). The subject walked on a straight, 50 m track (actually a hallway) at a self-selected cadence (87 steps/min). As has been documented by others (e.g., see [36]), the mechanics of treadmill walking are not entirely consistent with the dynamics of overground walking, and as such the self-selected speeds overground are typically significantly faster than self-selected speeds on a treadmill. Consistent with this phenomenon, the subject’s self-selected speed during the overground walking tests was 87 steps/min, which corresponded to a walking speed of 5.1 km/h, both of which are significantly greater than the self-selected treadmill walking (which were 75 steps/min and 2.8 km/h, respectively). Furthermore, the subject’s overground self-selected speed increased 24% from 4.1 to 5.1 km/h while using the powered prosthesis. The subject walked on the 50 m track at a self-selected speed for a total of ten trials while prosthesis data (i.e., servoamplifier currents, battery current and voltage, joint positions, velocities and torques, socket sagittal plane moment, heel and ball of foot loads, 3-D shank accelerations, and controller state information) were collected at a 200 Hz sampling rate. A video demonstrating the powered prosthesis in use overground is included in the supplemental material.

Measured joint angles, torques, and powers from walking on level ground at the self-selected cadence for ten consecutive strides are shown in Fig. 13. As indicated by the data, the powered prosthesis provides knee torques over 40 N·m (during stance flexion) and ankle torques approaching 120 N·m during toe-off. As shown in the power data, the prosthesis is contributing significant positive power (during stance) at both the knee joint (peak powers of 50 W) and ankle joint (peak powers approaching 250 W). For each stride, the prosthesis delivers 13.8 J of net energy on average at the ankle. Finally, the torque tracking for the knee and ankle joints, as shown in Fig. 14, indicates good torque tracking, and further indicates that the torque and power capabilities of the self-powered prosthesis are well suited to the demands of the controller.

Fig. 13.

Measured joint angles, torques, and powers of the powered prosthesis for ten consecutive gait cycles at self-selected speed (5.1 km/h at 87 steps/min).

Fig. 14.

References, and actual knee and ankle joint torques of the powered prosthesis for one stride at self-selected speed (5.1 km/h at 87 steps/min) on normal ground.

C. Power Consumption and Battery Life

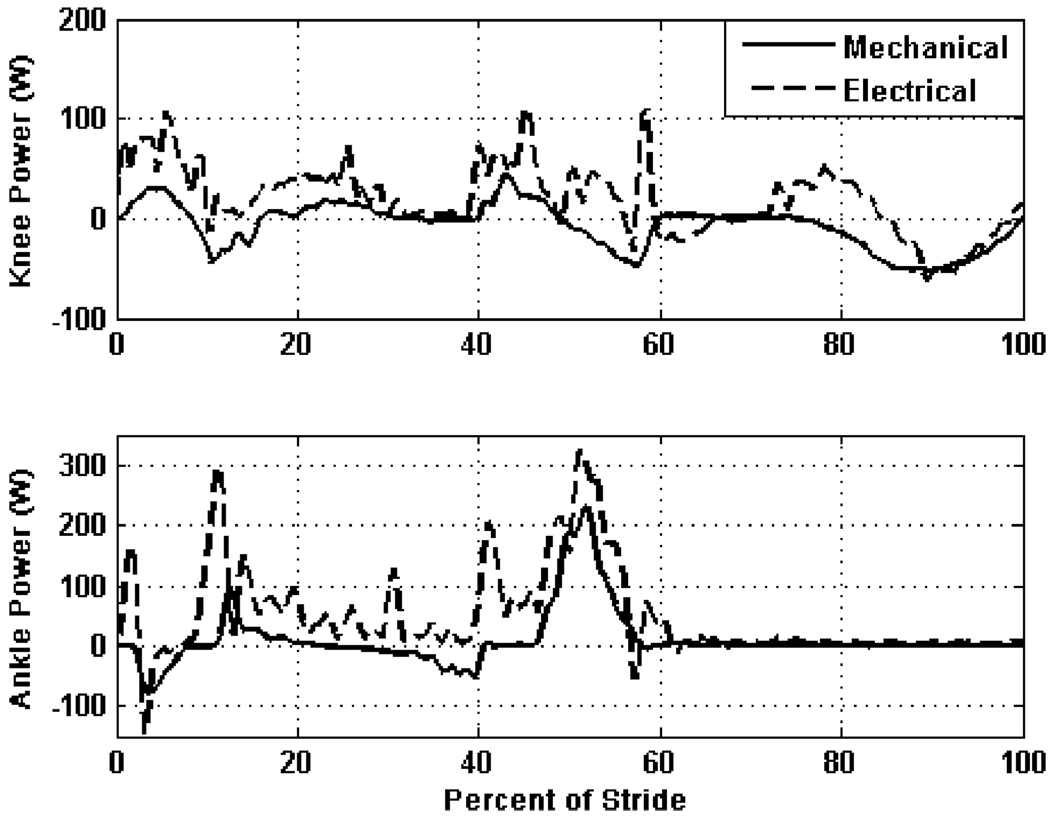

One of the primary constraints of the electrically powered knee and ankle prosthesis design is the power source. As such, the electrical power consumption was measured to characterize the potential battery life and range of the device. The electrical power consumed (by the servoamplifiers) and the mechanical power generated over one gait cycle are shown in Fig. 15. Electrical power regeneration (afforded by the regenerative servoamplifiers) is observed in the late swing gait phase in the knee. At the ankle joint, a peak mechanical power output of over 200 W is experienced at toe-off, which requires approximately 50% more electrical power at the motor leads.

Fig. 15.

Measured electrical and mechanical power at the knee and ankle joints of the powered prosthesis over one gait cycle at self-selected speed (5.1 km/h at 87 steps/min) on normal ground.

In order to characterize battery requirements, the average electrical power required by prosthesis (i.e., the embedded system, knee joint, and ankle joint) during standing and walking over level ground (at the self-selected speed of 5.1 km/h) is shown in Fig. 16. The total average power consumption for level ground walking and standing is 66 and 10 W, respectively. Since the prosthesis incorporates a (rechargeable) 118 W·h lithium polymer battery, such electrical power requirements suggest a battery life between charges of approximately 1.8 h of walking or 12 h of standing. With these figures, the prosthesis is capable of over 4500 strides (9000 steps by the user) with the prosthesis at the self-selected cadence. Given the walking speed of 5.1 km/h, the measured power requirements indicate a walking distance (for the amputee subject) of 9.0 km. Note that if the energy density of lithium ion battery technology doubles over the next five years (as is projected [31]), the walking range between battery charges would similarly double approaching 20 km.

Fig. 16.

Average electrical power consumption of the powered prosthesis for standing and walking at self-selected speed (5.1 km/h at 87 steps/min) on normal ground.

IV. CONCLUSION

This paper has described the design and control of a fully self-contained electrically powered knee and ankle prosthesis capable of producing human-scale power. Experimental results with a unilateral amputee indicate that the device can provide transfemoral amputee biomechanics during walking similar to those typically observed during healthy biomechanics. Power consumption measurements on level ground indicate that the device consumes 66 W at a walking speed of 5.1 km/h on a 75 kg subject. As such, given the specifications of the on-board battery pack, the prosthesis can provide 9.0 km of level, overground walking between recharges. Future work includes addressing the audible noise of the device and a comprehensive biomechanical evaluation of the powered prosthesis on multiple amputee subjects.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge the support of Otto Bock Healthcare Products for donation of prosthetic components and A. Fitzsimmons, CP, OTR/L for his assistance in prosthetic fitting and gait evaluation.

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health under Grant R01EB005684-01.

Biographies

Frank Sup (S’06–M’09) received the B.S. degree from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, Urbana, in 2001, and the M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in mechanical engineering from Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, in 2006 and 2009, respectively.

He is currently a Research Associate in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Vanderbilt University. His current research interests include the design, control, and testing of lower extremity prostheses, embedded systems, and robotics.

Huseyin Atakan Varol (S’01–M’09) received the B.S. degree in mechatronics engineering from Sabanci University, Istanbul, Turkey, in 2005, and the M.S. and Ph.D. degrees in electrical engineering from Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, in 2007 and 2009, respectively.

He is currently a Research Associate in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Vanderbilt University. His current research interests include biomechatronics with an emphasis on lower limb prostheses, control, signal processing, machine learning, and embedded systems.

Jason Mitchell received the B.S. degree from Tennessee Technological University, Cookeville, in 1999, and the M.S. degree from Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, in 2002, both in mechanical engineering.

He is currently an R&D Engineer in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Vanderbilt University. His current research interests include design and fabrication of upper and lower extremity prostheses.

Thomas J. Withrow (M’07) received the S.B. degree in engineering science with specialization in biomedical engineering from Harvard University, Cambridge, MA, in 2000, and the M.S.E. degree in biomedical engineering, a second M.S.E. degree in mechanical engineering, and the Ph.D. degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, in 2001, 2002, and 2005, respectively.

He is currently an Assistant Professor of the Practice in the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN. His current research interests include the development, design, and testing of upper and lower extremity prostheses, functional electrical stimulation, biomaterial testing, injury biomechanics, especially to the spine and the knee, and the biomechanics of injury prevention.

Michael Goldfarb (S’93–M’95) received the B.S. degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Arizona, Tucson, in 1988, and the S.M. and Ph.D. degrees in mechanical engineering from Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, in 1992 and 1994, respectively.

Since 1994, he has been with the Department of Mechanical Engineering, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, where he is currently the H. Fort Flowers Professor of Mechanical Engineering. His current research interests include the design and control of advanced upper and lower extremity prostheses, and gait restoration for spinal cord injured persons.

Footnotes

This paper has supplementary downloadable multimedia material available at http://ieeexplore.ieee.org, provided by the authors. This material includes one video (IEEETMECH_poweredprosthesis_video.wmv) demonstrating the Vanderbilt powered knee and ankle prosthesis worn by a transfemoral amputee subject. The video can be played with Windows and its size is 9.1 MB. Contact michael.goldarb@vanderbilt.edu for further questions about this work.

Color versions of one or more of the figures in this paper are available online at http://ieeexplore.ieee.org.

Contributor Information

Frank Sup, Email: frank.sup@vanderbilt.edu.

Huseyin Atakan Varol, Email: atakan.varol@vanderbilt.edu.

Jason Mitchell, Email: jason.mitchell@vanderbilt.edu.

Thomas J. Withrow, Email: thomas.j.withrow@vanderbilt.edu.

Michael Goldfarb, Email: michael.goldfarb@vanderbilt.edu.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams PF, Hendershot GE, Marano MA. Current Estimates From the National Health Interview Survey, 1996. Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 1999. (Vital and Health Statistics Series 10) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feinglass J, Brown JL, LaSasso A, Sohn MW, Manheim LM, Shah SJ, Pearce WH. Rates of lower-extremity amputation and arterial reconstruction in the United States, 1979 to 1996. Amer. J. Public Health. 1999 Aug;vol. 89(no. 8):1222–1227. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DeVita P, Torry M, Glover KL, Speroni DL. A functional knee brace alters joint torque and power patterns during walking and running. J. Biomech. 1996 May;vol. 29(no. 5):583–588. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00115-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jacobs R, Bobbert MF, van Ingen Schenau GJ. Mechanical output from individual muscles during explosive leg extensions: The role of biarticular muscles. J. Biomech. 1996 Apr;vol. 29(no. 4):513–523. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00067-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nadeau S, McFadyen BJ, Malouin F. Frontal and sagittal plane analyses of the stair climbing task in healthy adults aged over 40 years: what are the challenges compared to level walking? Clin. Biomech. 2003 Dec;vol. 18(no. 10):950–959. doi: 10.1016/s0268-0033(03)00179-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nagano A, Ishige Y, Fukashiro S. Comparison of new approaches to estimate mechanical output of individual joints in vertical jumps. J. Biomech. 1998 Oct;vol. 31(no. 10):951–955. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(98)00094-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prilutsky BI, Petrova LN, Raitsin LM. Comparison of mechanical energy expenditure of joint moments and muscle forces during human locomotion. J. Biomech. 1996 Apr;vol. 29(no. 4):405–415. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(95)00083-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riener R, Rabuffetti M, Frigo C. Joint powers in stair climbing at different slopes. Proc. 1st Joint BMES/EMBS Conf. 1999;vol. 1:530. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Winter D. The Biomechanics and Motor Control of Human Gait: Normal, Elderly and Pathological. 2nd ed. Waterloo, ON: Univ. Waterloo Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Winter DA, Sienko SE. Biomechanics of below-knee amputee gait. J. Biomech. 1988;vol. 21(no. 5):361–367. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(88)90142-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Waters RL, Perry J, Antonelli D, Hislop H. Energy cost of walking of amputees—Influence of level of amputation. J. Bone Joint Surg.-Amer. 1976;vol. 58(no. 1):42–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donath M. M.S. thesis. Cambridge, MA: Dept. Mech. Eng., Massachusetts Inst. Technol.; 1974. Proportional EMG control for above knee prostheses. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Flowers WC. Ph.D. dissertation. Cambridge, MA: Dept. Mech. Eng., Massachusetts Inst. Technol.; 1973. A man-interactive simulator system for above-knee prosthetics studies. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flowers WC, Mann RW. Electrohydraulic knee-torque controller for a prosthesis simulator. ASME J. Biomech. Eng. 1977;vol. 99(no. 4):3–8. doi: 10.1115/1.3426266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grimes DL. Ph.D. dissertation. Cambridge, MA: Dept. Mech. Eng., Massachusetts Inst. Technol.; 1979. An active multi-mode above knee prosthesis controller. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grimes DL, Flowers WC, Donath M. Feasibility of an active control scheme for above knee prostheses. ASME J. Biomech. Eng. 1977;vol. 99(no. 4):215–221. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stein JL, Flowers WC. Stance phase-control of above-knee prostheses—Knee control versus SACH foot design. J. Biomech. 1987;vol. 20(no. 1):19–28. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(87)90263-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stein JL. Ph.D. dissertation. Cambridge, MA: Dept. Mech. Eng., Massachusetts Inst. Technol.; 1983. Design issues in the stance phase control of above-knee prostheses. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Popovic D, Schwirtlich L. de Vries J, editor. Belgrade active A/K prosthesis. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Excerpta Medica; Electrophysiological Kinesiology. 1988:337–343. (International Congress Series 804)

- 20.Bedard S, Roy P. Actuated leg prosthesis for above-knee amputees. 7 314 490. U.S. Patent. 2003 Jun 17;

- 21.Martinez-Villalpando E, Weber J, Elliott G, Herr H. Design of an agonist-antagonist active knee prosthesis. Proc. IEEE/RAS-EMBS Int. Conf. Biomed. Robot. Biomechatron. 2008:529–534. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klute GK, Czerniecki J, Hannaford B. Muscle-like pneumatic actuators for below-knee prostheses. Proc. 7th Int. Conf. New Actuators. 2000:289–292. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koniuk W. Self-adusting prosthetic ankle apparatus. 6 443 993. U.S. Patent. 2001 Mar 23;

- 24.Bellman R, Holgate A, Sugar T. SPARKy 3: Design of an active robotic ankle prosthesis with two actuated degrees of freedom using regenerative kinetics. Proc. IEEE/RAS-EMBS Int. Conf. Biomed. Robot. Biomechatron. 2008:511–516. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Au S, Herr H. Powered ankle-foot prosthesis. IEEE Robot. Autom. Mag. 2008 Sep;vol. 15(no. 3):52–59. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sup F, Bohara A, Goldfarb M. Design and control of a powered transfemoral prosthesis. Int. J. Robot. Res. 2008 Feb;vol. 27(no. 2):263–273. doi: 10.1177/0278364907084588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fite KB, Goldfarb M. Design and energetic characterization of a proportional-injector monopropellant-powered actuator. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2006 Apr;vol. 11(no. 2):196–204. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fite KB, Mitchell JE, Barth EJ, Goldfarb M. A unified force controller for a proportional-injector direct-injection monopropellant-powered actuator. Trans. ASME, J. Dyn. Syst., Meas. Control. 2006 Mar;vol. 128(no. 1):159–164. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Goldfarb M, Barth EJ, Gogola MA, Wehrmeyer JA. Design and energetic characterization of a liquid-propellant-powered actuator for self-powered robots. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics. 2003 Jun;vol. 8(no. 2):254–262. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shields BL, Fite KB, Goldfarb M. Design, control, and energetic characterization of a solenoid-injected monopropellant-powered actuator. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatronics. 2006 Aug;vol. 11(no. 4):477–487. [Google Scholar]

- 31.In search of the perfect battery. Economist. 2008;vol. 386(no. 8570):22–24. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sup F, Varol HA, Mitchell J, Withrow T, Goldfarb M. Design and control of an active electrical knee and ankle prosthesis. Proc. IEEE/RAS-EMBS Int. Conf. Biomed. Robot. Biomechatron. 2008:523–528. doi: 10.1109/BIOROB.2008.4762811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Clauser CE, McConville JT, Young JM. Weight, volume and center of mass of segments of the human body. Dayton, OH: Wright Patterson Airforce Base; 1969. Rep. AMRL-TR-69–70. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Varol HA, Sup F, Goldfarb M. Real-time gait mode intent recognition of a powered knee and ankle prosthesis for standing and walking. Proc. IEEE/RAS-EMBS Int. Conf. Biomed. Robot. Biomechatron. 2008:66–72. doi: 10.1109/BIOROB.2008.4762860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Blumentritt S, Scherer H, Wellershaus U, Michael J. Design principles, biomechanical data and clinical experience with a polycentric knee offering controlled stance phase knee flexion: A preliminary report. J. Prosthet. Orthot. 1997;vol. 9(no. 1):18–24. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Traballesi M, Porcacchia P, Averna T, Brunelli S. Energy cost of walking measurements in subjects with lower limb amputations: A comparison study between floor and treadmill test. Gait Posture. 2008 Jan;vol. 27(no. 1):70–75. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.