Abstract

Leukocyte extravasation is a prerequisite for host defense and autoimmunity alike. Detailed understanding of the tightly controlled and overlapping sequences of leukocyte extravasation might aid development of novel therapeutic strategies. Leukocyte extravasation is initiated by interaction of selectins with appropriate carbohydrate ligands. Lack of P-selectin expression leads to decreased contact hypersensitivity responses. Yet, it remains unclear if this is due to inhibition of leukocyte extravasation to the skin or due to interference with initial immune activation in lymph nodes. In line with previous data, we here report a decreased contact hypersensitivity response, induced by 2,4,-dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB), in P-selectin-deficient mice. Eliciting an immune reaction towards DNFB in wild-type mice, followed by adoptive transfer to P-selectin-deficient mice, had no impact on inflammatory response in recipients. This was significantly reduced in wild-type recipient mice adoptively transferred with DNFB immunity generated in P-selectin-deficient mice. To investigate if platelet or endothelial P-selectin was involved, mice solely lacking platelet P-selectin expression generated by bone marrow transplantation were used. Adoptive transfer of immunity from wild-type mice reconstituted with P-selectin-deficient bone marrow led to a decrease of inflammatory response. Comparing this decrease to the one observed using P-selectin-deficient mice, no differences were observed. Our observations indicate that platelet, not endothelial, P-selectin contributes to generation of immunity in DNFB-induced contact hypersensitivity.

Infiltration of leukocytes is a hallmark of inflammation. To reach the affected tissues, leukocytes must leave the bloodstream. This process of leukocyte extravasation requires several distinct steps, occurring in sequence. Leukocyte extravasation is initiated by short-lived interactions of adhesion molecules from the selectin family with appropriate carbohydrate scaffolds displayed by several glycoproteins, leading to tethering and rolling of leukocytes along the endothelial lining of the vasculature. Of the numerous adhesion molecules, endothelial P-selectin, along with E-selectin and vascular cell adhesion molecule (VCAM)-1, initiates and sustains rolling interactions of leukocytes in the skin microvasculature.

In addition to a direct interaction of leukocytes with the endothelium lining the vasculature, platelets are becoming more and more recognized to initiate leukocyte rolling in several organs, including peripheral lymph nodes,1 atherosclerotic lesions2 and skin.3 In detail, platelets may influence leukocyte rolling in numerous ways: First, formation of platelet-leukocyte aggregates in the bloodstream leads to activation of bound leukocytes,2 leading to an increased avidity of leukocyte integrins,4–6 which then may allow rolling interactions through binding of leukocyte VLA-4 to endothelial VCAM-1.7 Second, rolling of activated platelets along the vasculature2,3,8,9 allows a deposition of platelet-derived pro-inflammatory substances directly to the endothelial cells, which in turn activates endothelial cells, leading to an increased expression/secretion of adhesion molecules and cytokines.10–13 Third, formation of platelet-leukocyte aggregates increases leukocyte rolling in lymph nodes9 and the skin.3 In addition, this platelet-mediated leukocyte rolling has been shown to functionally relevant in lymph nodes, lung and the skin. Impaired extravasation of naïve T lymphocytes into the lymph nodes, and thus diminished generation of immunity, in L-selectin-deficient mice,14 can be restored by infusion of activated human platelets. Interestingly, infusion of activated platelets had no impact on generation of immunity in wild-type mice.15 Likewise, pulmonary leukocyte recruitment in platelet-depleted mice was abolished in a model of ovalbumin-induced asthma.16 Furthermore, in a model of chronically induced contact dermatitis, infusion of wild-type, but not P-selectin-deficient, platelets restored the inflammatory response in mice rendered thrombocytopenic.17

The latter observation is in line with previous findings, showing an impairment of cutaneous inflammation induced by application of haptens, such as oxazolone, in P-selectin-deficient mice.18 However, while the work by Tamagawa-Mineoka and colleagues17 has clearly shown a dependency of leukocyte extravasation on platelet P-selectin expression to the skin, the role of P-selectin in the generation of immunity toward cutaneous applied haptens remained to be elucidated. We therefore investigated the role of P-selectin in the generation of immunity in the model of 2,4,-dinitrofluorobenzene (DNFB)-induced cutaneous hypersensitivity.

Materials and Methods

Mice

P-Selectin-deficient (P-sel−/−) mice on a C57BL/6J background (homozygous for the Selptm1Bay mutation) and control wild-type C57BL/6J mice were obtained from Charles River Germany). L-Selectin-deficient mice on the C57BL/6J genetic background19 were kindly provided by Dr. R. Hynes (Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Center for Cancer Research and Department of Biology, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts). All mice were maintained on a 12-hour light–dark cycle at the animal facility of the J. W. Goethe University. Mice were fed acidified drinking water and standard chow ad libitum. All protocols were approved by the governmental administration (Darmstadt, Hessen).

Murine Bone-Marrow Transplantation Model

Bone marrow (BM) cells were obtained by flushing the femurs of donor P-selectin-deficient mice in C57BL/6J background (Charles River) as described previously.20 Recipient C57BL/6J mice received lethal irradiation doses at 4 to 6 weeks of age (2 × 500 cGy), and animals received i.v. injections containing 2 to 3 × 106 BM cells. BM cells from normal C57BL/6J mice were taken as controls. At 6 weeks post-transplantation, by which time the BM of recipient mice was reconstituted, adoptive transfer experiments were performed. The lack of P-selectin expression in recipients of P-selectin-deficient BM-recipient mice was confirmed by analyzing P-selectin expression on platelet activation.20

Adoptive Transfer of Immunity

Adoptive transfer experiments were performed according to published protocols21: Mice were sensitized by painting 75 μl of DNFB (Sigma) solution (0.5% in acetone/olive oil, 4/1) on the back of the mice on day 0. On day 5, spleens and regional lymph nodes were removed from DNFB-sensitized mice, and single cell suspensions were prepared by homogenizing lymph nodes and spleens from donor mice through a nylon mesh (70 mm, BD Biosciences). The cell number was adjusted to 2 × 108/ml, and 200 μl were injected i.v. into each recipient C57Bl/6 mouse, followed by immediate application of 20 μl DNFB at 0.3% to the right ear of the mice.

Analysis of Ear Swelling

CHS response was determined using a spring-loaded micrometer (Mitutoyo, Neuss, Germany) in a blinded fashion. Ear swelling responses of DNFB-challenged ears were compared with the response of the vehicle-treated ear in sensitized animals and were expressed as centimeters × 10−3 (mean ± SD).

Induction of Thrombocytopenia

In some experiments induction of thrombocytopenia was performed. For this purpose, mice were injected with either a mixture of monoclonal rat anti-mouse-CD42b (# R300, Emfret Analytics) or isotype control antibody (rat IgG) at a dose of 2.5 μg/g body weight 2 hours before painting with DNFB and 3 days thereafter. Platelet counts were monitored 2 hours after the initial antibody injection and immediately before performing the adoptive transfer.

H&E Histology Staining and Immunohistology

H&E staining was performed according to standard methods established in our laboratory.22 Severity of inflammation was scored semiquantitatively as previously described.23 The score ranges from one to four, corresponding to no, weak, moderate, or strong staining, respectively. Sections were also stained for infiltration by CD3, neutrophils, and monocytes/macrophages. Six μm thick cryostat sections were incubated with an antibody specific for either CD3 (polyclonal rabbit, DakoCytomation, Denmark), neutrophils (clone: 7/4, Serotec, Oxford, UK), monocytes/macrophages (clone: F4/80, Serotec), or isotype control (clone: LO-DNP-11, Serotec). Staining was visualized by addition of appropriate second step antibodies and Fast Red Substrate Kit (Dako). In analogy to the scoring system used for H&E-stained sections, staining was assigned a score ranging from 1 to 4, corresponding to no, weak, moderate, or strong staining, respectively. All sections were independently scored by two observes blinded for the coding of sections.

Qualitative and Quantitative Analysis of Infiltrating Cells24

Ears were longitudinally separated at the cartilage and incubated in RPMI supplemented with 0.05% DNase (Sigma) and Liberase (Roche) at 37°C for 90 minutes. Digestion was stopped by adding an equal amount of RPMI with 5% fetal calf serum at 4°C. Using appropriate inserts, single ear-specimen were grinded for 7 minutes using Medimachine (BD Biosciences). Thereafter cells were passed through a 70 μm nylon cell strainer (BD Biosciences), washed and analyzed.

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed as described elsewhere.25 For analysis of infiltrating cells following antibodies were used (BD Biosciences): fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-CD4 (clone GK1.5), FITC-CD8 (clone 53-6.7), NK cell-defining FITC-NK1.1 (clone PK136), and FITC-Gr-1 (clone RB6-8C5) recognizing granulocytes and monocytes. Appropriate isotype control antibodies with a corresponding conjugate were used as negative controls.

Statistics

All data are expressed as mean ± SD. Evaluation of statistical significance was performed as indicated in the text. A P value <0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Sigma Stat 3.5 (Systat Software) software was used for statistical calculations.

Results

Decreased CHS Response in P-Selectin-Deficient Mice

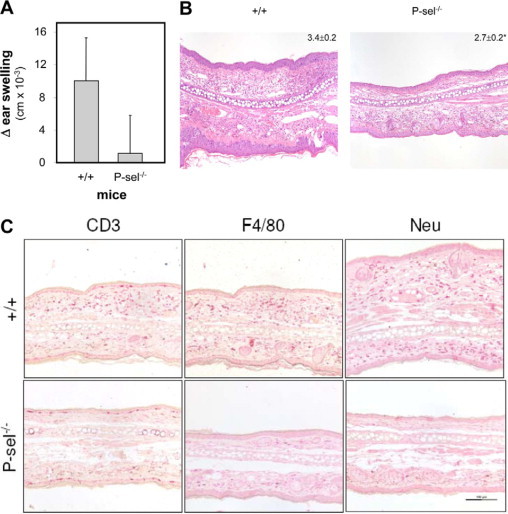

Wild-type and P-selectin-deficient mice were sensitized with DNFB. After challenge with DNFB, the inflammatory response was analyzed by measurement of ear swelling and leukocyte infiltration. Compared with wild-type mice, lack of P-selectin expression led to a significant reduction of both ear swelling and leukocyte infiltration: In wild-type mice, the average ear swelling response was 10.0 ± 5.4 cm × 10−3, compared with 1.1 ± 4.7 cm × 10−3 in P-selectin-deficient mice (Figure 1A). Based on a semiquantitative score,23 leukocyte infiltration was reduced from 3.4 ± 0.2 in wild-type mice to 2.7 ± 0.2 in P-selectin-deficient mice (Figure 1B). In line, infiltration with lymphocytes, neutrophils, and macrophages was reduced in mice lacking P-selectin expression (Figure 1C). These data confirmed and expanded previous findings observed in CHS models using other sensitizing agents.17,18

Figure 1.

P-selectin deficiency leads to a diminished inflammatory response in DNFB-induced contact hypersensitivity. A: Ear swelling evaluated 24 hours after challenge with DNFB of sensitized wild-type (+/+) or P-selectin-deficient mice (P-sel−/−). Data are from at least eight mice per group; P < 0.001, t-test. B: Representative H&E stained specimen from either wild-type or P-selectin-deficient mice 24 hours after challenge with DNFB. Numbers in the upper right indicate the severity of leukocyte infiltration of all mice investigated as determined by a semiquantitative score (ranging from 1: no infiltration to 4: servere infiltration 23). C: Furthermore, a decrease in lymphocyte, neutrophil, and macrophage expression was noted in mice lacking P-selectin expression. In detail, sections were stained with the markers indicated in the figures as outlined in the Materials and Methods section. Infiltration of respective leukocyte subsets was scored as detailed above. CD3 expression was significantly lower in P-selectin-deficient (1.8 ± 0.3) compared with wild-type mice (2.8 ± 0.3, P = 0.008). Likewise, a notable lower expression of neutrophils and macrophages was observed in mice lacking P-selectin expression (Neu: 2.6 ± 0.3 (wild-type)/2.1 ± 0.1 (P-sel−/−), P = 0.04; F4/80: 2.6 ± 0.4 (wild-type)/1.3 ± 0.1 (P-sel−/−); t-test, n = 3 mice per group).

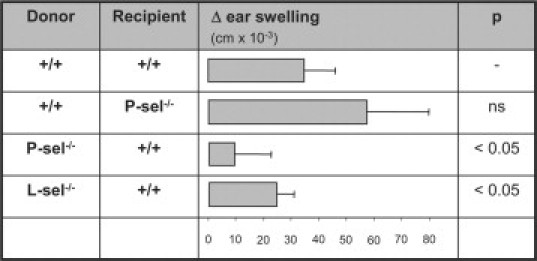

P-Selectin Contributes to Generation of Immunity, but Not to Elicitation of the CHS Response

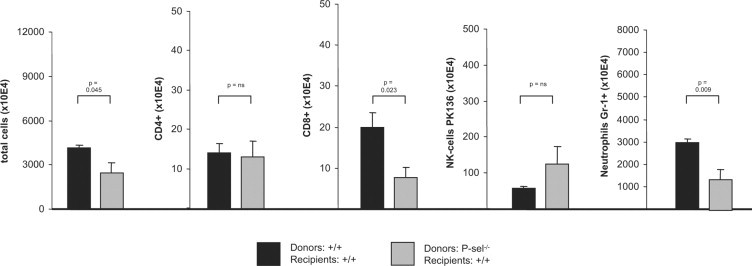

However, these data do not distinguish between (i) a possible role of P-selectin in the initial process of generation of antigen-specific immunity, (ii) extravasation to the skin during the effector-phase, or (iii) both phases. We therefore performed adoptive transfer experiments to further differentiate the contribution of P-selectin to cutaneous inflammation. Adoptive transfer of lymph node and spleen cells from DNFB-sensitized wild-type mice into P-selectin-deficient mice showed a (not statistically significant) trend toward an increased ear swelling response. In sharp contrast, adoptive transfer from P-selectin-deficient donor mice into wild-type recipients lead to decreased ear swelling, which can be likewise observed using L-selectin-deficient mice as donors (Figure 2). Detailed characterization of the leukocyte infiltrate in recipients of adoptive transfer experiments revealed a decreased extravasation of CD8+ lymphocytes and Gr-1+ neutrophils. Extravasation of CD4+ cells and NK-cells remained unaffected, with a statistically not significant trend toward higher NK-cells in mice adoptively transferred with cells form P-selectin-deficient mice (Figure 3). These data point toward a contribution of P-selectin in the generation of immunity in DNFB-induced contact hypersensitivity. The observed changes are not due to an altered subset distribution in the adoptively transferred cell population, as the distribution of CD3+, CD4+, CD8+ T cells, neutrophils an macrophages, was identical adoptively transferred cells from either wild-type or P-selectin-deficient mice (Table 1).

Figure 2.

P-selectin is required for generation of immunity, but is not involved in extravasation of leukocytes to the skin. Wild-type (+/+), L-selectin-deficient (L-sel−/−), and P-selectin-deficient (P-sel−/−) mice were sensitized with DNFB. Five days after DNFB-exposure, mice were sacrificed and lymphocytes were isolated from peripheral lymph nodes and spleens. Isolated cells were injected i.v. into recipient wild-type mice, which were subsequently exposed to DNFB on the right ear. Twenty-four hours later, ear swelling response and leukocyte infiltration was evaluated in recipient mice. Ear swelling response 24 hours after exposition to DNFB in recipient wild-type mice: As previously described, L-selectin significantly contributes to sensitization in the model of DNFB-induced cutaneous contact hypersensitivity, as L-selectin deficiency leads to reduced rolling interactions of lymphocytes with order I-III venules in lymph nodes. We here however provide evidence that P-selectin also is critically involved in generating immunity toward DNFB. By comparing the relative contribution of L- and P-selectin in this process, the contribution of P-selectin seems more detrimental (analysis of variance on ranks—multiple comparisons according to the Dunn‘s method).

Figure 3.

Reduced ear swelling response in wild-type mice after adoptive transfer of leukocytes from DNFB sensitized P-selectin-deficient mice. 24 hours after adoptive transfer and challenge with DNFB, ears were homogenized. From homogenates total cell number was counted, and subsets of infiltrating leukocytes were evaluated using flow cytometry. As indicated below, total cell number is reduced in the ears of mice, which received lymphocytes from P-selectin-deficient mice. This reduction in infiltration leukocytes is due to decreased numbers of CD8+ cells and neutrophils. Data shown is from three mice. Statistical evaluation was performed using the t-test.

Table 1.

Morphologic Characterization of Cells Used for Adoptive Transfer

| Wild-type mice |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LN |

Spleen |

LN |

Spleen |

|||||

| Solvent | DNFB | Solvent | DNFB | Solvent | DNFB | Solvent | DNFB | |

| CD3 | 52.0 ± 12.7 | 48.1 ± 6.7 | 14.6 ± 4.1 | 12.8 ± 1.6 | 51.4 ± 7.6 | 44.8 ± 4.5 | 11.8 ± 2.7 | 10.6 ± 1.0 |

| CD4 | 30.7 ± 5.9 | 28.2 ± 3.4 | 10.4 ± 4.0 | 8.3 ± 0.5 | 29.8 ± 1.3 | 28.0 ± 2.2 | 8.8 ± 2.1 | 6.6 ± 2.5 |

| CD8 | 30.8 ± 6.0 | 28.2 ± 3.4 | 9.1 ± 2.5 | 6.9 ± 0.3 | 28.7 ± 3.6 | 24.8 ± 3.6 | 6.1 ± 0.7 | 4.9 ± 1.8 |

| NK | 5.7 ± 2.1 | 2.3 ± 1.1 | 5.2 ± 1.0 | 2.7 ± 1.3 | 2.1 ± 1.0 | 1.8 ± 0.8 | 1.2 ± 1.3 | 1.3 ± 1.6 |

| Neu | 1.9 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 3.7 ± 1.9 | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 0.8 ± 0.2 | 3.7 ± 0.4 | 3.8 ± 0.8 |

| F4/80 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 3.0 ± 0.8 | 1.5 ± 0.5 | 3.7 ± 1.9 | 1.9 ± 0.9 | 1.6 ± 1.1 | 3.0 ± 0.7 | 2.8 ± 0.8 |

Single cell suspensions from peripheral lymph nodes (LN) and spleens were prepared from mice 5 days after painting with DNFB or solvent by gently passing through a nylon mesh. Cells were stained with fluorescently labeled antibodies binding to the respective leukocyte subsets, or appropriate isotype control antibodies. We observed no difference in the leukocyte distribution in peripheral lymph nodes and spleen of wild-type compared with P-selectin-deficient mice. Furthermore, induction of an immune response in either wild-type or P-selectin-deficient mice did not alter the subset distribution in the two compartments. Therefore, P-selectin deficiency does not alter the morphology of the lymphocyte subset distribution. Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation, and is based on three mice per group.

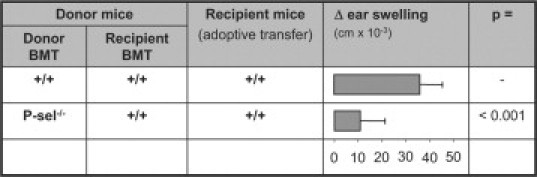

Platelet, Not Endothelial P-Selectin Expression Contributes to Generation of Immunity

As P-selectin is expressed on endothelial cells, as well as on (activated) platelets, we next thought to investigate the relative contribution of endothelial versus platelet P-selectin in this process. For this purpose, mice selectively deficient in platelet P-selectin expression were generated using bone marrow transplantation.20 Adoptively transferring immunity generated in wild-type mice transplanted with wild-type bone marrow into wild-type recipient mice resulted in a similar response in recipients compared with using non-bone marrow transplanted mice as donors (34.7 ± 11.7 cm × 10−3 [non-bone marrow transplanted] vs. 35.8 ± 9.6 cm × 10−3 [wild-type bone marrow transplanted], p = n.s., t-test). However, adoptive transfer of immunity from wild-type mice reconstituted with P-selectin-deficient bone marrow, led to a decrease of the inflammatory response in recipient mice (Figure 4). Comparing this decrease to the one observed using P-selectin-deficient mice, no difference can be observed (9.1 ± 13.4 cm × 10−3 from P-selectin-deficient donors, compared with 10.7 ± 10.4 cm × 10−3 from wild-type donor mice transplanted with P-selectin-deficient bone marrow). Taken together this indicates that platelet, not endothelial, P-selectin contributes to generation of immunity in DNFB-induced contact hypersensitivity.

Figure 4.

Primarily platelet, not endothelial, P-selectin is required to generate immunity. Using BMT mice as donors for adoptive transfer experiments into wild-type C57Bl/6 mice, ear swelling responses were evaluated. Lack of platelet P-selectin expression had a similar effect as mice fully deficient in P-selectin expression. Hence, platelet P-selectin expression seems more crucially involved in generating immunity than endothelial P-selectin. Data from at least six mice per group; statistical comparisons performed using t-test.

To further sustain the importance of platelets in the generation of immunity in this model, we induced a thrombocytopenia in donor mice for adoptive transfer experiments. Induction of thrombocytopenia in donor mice lead to a significant reduction of the ear swelling response in recipient mice (Table 2). Induction of thrombocytopenia reduced platelet counts over 20-fold within 2 hours to 10.0 ± 4.2/μl (determined on day 5).

Table 2.

Thrombocytopenia Hinders Generation of Immunity towards DNFB

| Treatment of donor mice | Δ ear swelling (cm × 10−3) in recipient mice |

|---|---|

| Isotype control antibody | 7.6 ± 1.2 |

| Anti-CD42 antibody | 1.5 ± 0.6 |

Induction of thrombocytopenia and adoptive transfer was performed as described in Materials and Methods. Adoptive transfer of lymphocytes from thrombocytopenic mice led to a significant decrease of ear swelling in recipient mice with normal platelet counts (P = 0.005, t-test, n = 4 mice/group).

Discussion

We here demonstrate that platelet, but not endothelial, P-selectin expression contributes to the generation of immunity in a delayed type hypersensitivity reaction. In contrast, neither endothelial nor platelet P-selectin expression is required for the elicitation phase of a delayed type hypersensitivity response. These differences may be explained by the differential expression of adhesion molecules in lymph nodes compared with the skin. While in lymph nodes the P-selectin ligand peripheral lymph node adressin is expressed in abundance in class I-III levels26 it is only found in chronically inflamed skin.27 This may also explain why in thrombocytopenic mice infusion of activated platelets from wild-type, but not P-selectin-deficient mice restored the inflammatory response in mice chronically exposed to an immunogenic hapten.17

There are several mechanisms, which may explain the observed effect of platelet P-selectin on the generation of immunity: In principal, the observed effect might be due to impaired migration of antigen-presenting cells to the peripheral lymph nodes, failure to correctly present antigens to naive T lymphocytes, or defects in lymphocyte migration to peripheral lymph nodes. As platelets are exclusively present in the vasculature, the later hypothesis seems most likely. Platelet-facilitated lymphocyte extravasation might be due to one of the following effects, or a combination thereof: (i) by interaction with endothelial cells in the lymph nodes with subsequent deposition of platelet derived pro-inflammatory molecules28 as it has been described in carotid arteries of mice prone to atherosclerosis.2 (ii) by forming aggregates with leukocytes in vivo.29 Platelet-leukocyte aggregate formation has been shown to alter the adhesive capacity of leukocytes in a P-selectin dependent manner; eg, bound platelets increased expression, enhanced avidity of leukocyte adhesion molecules and increased the secretion of cytokines.4,5 (iii) Formation of platelet-leukocyte aggregates has been shown to mediate leukocyte-endothelial interaction in peripheral lymph nodes of mice.9 Platelet mediated leukocyte rolling is capable to reconstitute generation of immunity in L-selectin-deficient mice; while infusion of activated platelets into wild-type mice has no effect.15 To investigate, if P-selectin deficiency influences the subset distribution (CD3-, CD4-, and CD8-lymphocytes, NK cells, neutrophils, and macrophages) in the adoptively transferred cells, we characterized the leukocyte subset distribution in wild-type and P-selectin-deficient mice 5 days after painting with DNFB. Leukocyte subset distribution is similar in both stains of mice, and induction of an immune response toward DNFB did not lead to significant changes in subset distribution in either wild-type, or P-selectin-deficient mice (Table 2). This, however, does not rule out a contribution of platelet P-selectin might affect extravasation of a subset not identified by our morphological analysis. Hence, the actual molecular events by which platelet P-selectin contributes to the generation of immunity remain uncertain.

Despite these open issues, we believe that our findings have important clinical implications. As inhibition of P-selectin is a very promising therapeutic approach for modulation of inflammatory diseases and tumor metastasis,30 compounds with a (partial) P-selectin inhibitory activity have been developed. Three of these compounds, namely the pan-selectin antagonist Bimosiamose (TBC1269), several heparin preparations and recombinant PSGL-1-Ig-fusion protein either have been or are currently being evaluated in clinical trials.30 Few P-selectin antagonists have been evaluated in clinical trials in patients with inflammatory diseases. Among those, the pan- or selective E-selectin31 antagonist Bimosiamose (TBC-1269)32 attenuates late asthmatic reactions following allergen challenge in mild asthmatics.33 Another trial evaluated the effect of intralesional, subcutaneous bimosiamose injection over a treatment period of 14 days in patients with psoriasis (open-label, n = 5). Clinically, a weak, but statistically significant effect was observed.32 Use of P-selectin targeting strategies has to take into consideration that, besides to inhibition of leukocyte extravasation to the sites of inflammation, generation of immunity may be also impaired. This assumption is strengthened by the observation of an increased morbidity and mortality of P-selectin-deficient mice after i.p. inoculation with Streptococcus pneumoniae.34

In summary, platelet P-selectin's contribution to the generation of immunity may have two relevant clinical observations: (i) the immunosuppressive effects of P-selectin targeting strategies have to be taken into account. More specifically, anti-P-selectin therapies would be expected to be associated with an increased risk of infectious diseases. (ii) Therapeutics targeting P-selectin may also become a valuable approach in clinical settings, where generation of immunity may be detrimental; eg, in organ transplanted patients.

Footnotes

Supported by Patenschaftsmodell 2005 (clinic of the J.W. Goethe University to R.J.L. and H.H.R.), and the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (D.F.G. Lu877/3-1) to R.J.L. Additional grant support by the Excellence Cluster Inflammation at Interfaces (D.F.G. 306/1).

References

- 1.von Andrian UH, Mempel TR. Homing and cellular traffic in lymph nodes. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:867–878. doi: 10.1038/nri1222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huo Y, Schober A, Forlow SB, Smith DF, Hyman MC, Jung S, Littman DR, Weber C, Ley K. Circulating activated platelets exacerbate atherosclerosis in mice deficient in apolipoprotein E. Nat Med. 2003;9:61–67. doi: 10.1038/nm810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ludwig RJ, Schultz JE, Boehncke WH, Podda M, Tandi C, Krombach F, Baatz H, Kaufmann R, von Andrian UH, Zollner TM. Activated, but not resting platelets increase leukocyte rolling in murine skin utilizing a distinct set of adhesion molecules. J Invest Dermatol. 2004;122:830–836. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2004.22318.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weyrich AS, McIntyre TM, McEver RP, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA. Monocyte tethering by P-selectin regulates monocyte chemotactic protein- 1 and tumor necrosis factor-alpha secretion. Signal integration and NF- kappa B translocation. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:2297–2303. doi: 10.1172/JCI117921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weyrich AS, Elstad MR, McEver RP, McIntyre TM, Moore KL, Morrissey JH, Prescott SM, Zimmerman GA. Activated platelets signal chemokine synthesis by human monocytes. J Clin Invest. 1996;97:1525–1534. doi: 10.1172/JCI118575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hidari KI, Weyrich AS, Zimmerman GA, McEver RP. Engagement of P-selectin glycoprotein ligand-1 enhances tyrosine phosphorylation and activates mitogen-activated protein kinases in human neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28750–28756. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elices MJ, Osborn L, Takada Y, Crouse C, Luhowskyj S, Hemler ME, Lobb RR. VCAM-1 on activated endothelium interacts with the leukocyte integrin VLA-4 at a site distinct from the VLA-4/fibronectin binding site. Cell. 1990;60:577–584. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90661-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frenette PS, Denis CV, Weiss L, Jurk K, Subbarao S, Kehrel B, Hartwig JH, Vestweber D, Wagner DD. P-Selectin glycoprotein Ligand-1 (PSGL-1) is expressed on platelets and can mediate platelet-endothelial interactions in vivo. J Exp Med. 2000;191:1413–1422. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.8.1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diacovo TG, Puri KD, Warnock RA, Springer TA, von Andrian UH. Platelet mediated lymphocyte delivery to high endothelial venules. Science. 1996;273:252–273. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5272.252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.von Hundelshausen P, Weber KS, Huo Y, Proudfoot AE, Nelson PJ, Ley K, Weber C. RANTES deposition by platelets triggers monocyte arrest on inflamed and atherosclerotic endothelium. Circulation. 2001;103:1772–1777. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.13.1772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hawrylowicz CM, Howells GL, Feldmann M. Platelet-derived interleukin-1 induces human endothelial adhesion molecule expression and cytokine production. J Exp Med. 1991;174:785–790. doi: 10.1084/jem.174.4.785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplanski G, Porat R, Aiura K, Erban JK, Gelfand JA, Dinarello CA. Activated platelets induce endothelial secretion of interleukin-8 in vitro via an interleukin-1-mediated event. Blood. 1993;81:2492–2495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henn V, Slupsky JR, Gräfe M, Anagnostopoulos I, Förster R, Müller-Berghaus G, Kroczek RA. CD40 ligand on activated platelets triggers an inflammatory reaction of endothelial cells. Nature. 1998;391:591–594. doi: 10.1038/35393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Catalina MD, Carroll MC, Arizpe H, Takashima A, Estess P, Siegelman MH. The route of antigen entry determines the requirement for L-selectin during immune responses. J Exp Med. 1996;184:2341–2351. doi: 10.1084/jem.184.6.2341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diacovo TG, Catalina MD, Siegelman MH, von Andrian UH. Circulating activated platelets reconstitute lymphocyte homing and immunity in L-selectin deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1998;187:197–204. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.2.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pitchford SC, Momi S, Giannini S, Casali L, Spina D, Page CP, Gresele P. Platelet P-selectin is required for pulmonary eosinophil and lymphocyte recruitment in a murine model of allergic inflammation. Blood. 2004;105:2074–2081. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-06-2282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tamagawa-Mineoka R, Katoh N, Ueda E, Takenaka H, Kita M, Kishimoto S. The role of platelets in leukocyte recruitment in chronic contact hypersensitivity induced by repeated elicitation. Am J Pathol. 2007;170:2019–2029. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.060881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Subramaniam M, Saffaripour S, Watson SR, Mayadas TN, Hynes RO, Wagner DD. Reduced recruitment of inflammatory cells in a contact hypersensitivity response in P-selectin-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 1995;181:2277–2282. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.6.2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Borsig L, Wong R, Hynes RO, Varki NM, Varki A. Synergistic effects of L- and P-selectin in facilitating tumor metastasis can involve non-mucin ligands and implicate leukocytes as enhancers of metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:2193–2198. doi: 10.1073/pnas.261704098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ludwig RJ, Boehme B, Podda M, Henschler R, Jager E, Tandi C, Boehncke WH, Zollner TM, Kaufmann R, Gille J. Endothelial P-selectin as a target of heparin action in experimental melanoma lung metastasis. Cancer Res. 2004;64:2743–2750. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schwarz A, Beissert S, Grosse-Heitmeyer K, Gunzer M, Bluestone JA, Grabbe S, Schwarz T. Evidence for functional relevance of CTLA-4 in ultraviolet-radiation-induced tolerance. J Immunol. 2000;165:1824–1831. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.4.1824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludwig RJ, Werner RJ, Winker W, Boehncke WH, Wolter M, Kaufmann R. Chronic venous insufficiency—a potential trigger for localized scleroderma. JEADV. 2006;20:96–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2005.01359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ludwig RJ, Zollner TM, Santoso S, Hardt K, Gille J, Baatz H, Johann PS, Pfeffer J, Radeke HH, Schön MP, Kaufmann R, Boehncke WH, Podda M. Junctional adhesion molecules (JAM)-B and -C contribute to leukocyte extravasation to the skin and mediate cutaneous inflammation. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:969–976. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woelbing F, Kostka SL, Moelle K, Belkaid Y, Sunderkoetter C, Verbeek S, Waisman A, Nigg AP, Knop J, Udey MC, von Stebut E. Uptake of Leishmania major by dendritic cells is mediated by Fcgamma receptors and facilitates acquisition of protective immunity. J Exp Med. 2006;203:177–188. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubant SA, Ludwig RJ, Diehl S, Hardt K, Kaufmann R, Pfeilschifter JM, Boehncke WH. Dimethylfumarate reduces leukocyte rolling in vivo through modulation of adhesion molecule expression. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:326–331. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.von Andrian UH. Intravital microscopy of the peripheral lymph node microcirculation in mice. Microcirculation. 1996;3:287–300. doi: 10.3109/10739689609148303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arvilommi AM, Salmi M, Kalimo K, Jalkanen S. Lymphocyte binding to vascular endothelium in inflamed skin revisited: a central role for vascular adhesion protein-1 (VAP-1) Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:825–833. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gear AR, Camerini D. Platelet chemokines and chemokine receptors: linking hemostasis, inflammation, and host defense. Microcirculation. 2003;10:335–350. doi: 10.1038/sj.mn.7800198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Freedman JE, Loscalzo J. Platelet-monocyte aggregates: bridging thrombosis and inflammation. Circulation. 2002;105:2130–2132. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000017140.26466.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ludwig RJ, Schon MP, Boehncke WH. P-selectin: a common therapeutic target for cardiovascular disorders, inflammation and tumour metastasis. Expert Opin Ther Targets. 2007;11:1103–1117. doi: 10.1517/14728222.11.8.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hicks AE, Abbitt KB, Dodd P, Ridger VC, Hellewell PG, Norman KE. The anti inflammatory effects of a selectin ligand mimetic. TBC-1269, are not a result of competitive inhibition of leukocyte rolling in vivo. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:59–66. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1103573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Friedrich M, Bock D, Philipp S, Ludwig N, Sabat R, Wolk K, Schroeter-Maas S, Aydt E, Kang S, Dam TN, Zahlten R, Sterry W, Wolff G. Pan-selectin antagonism improves psoriasis manifestation in mice and man. Arch Dermatol Res. 2006;297:345–351. doi: 10.1007/s00403-005-0626-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Beeh KM, Beier J, Meyer M, Buhl R, Zahlten R, Wolff G. Bimosiamose, an inhaled small-molecule pan-selectin antagonist, attenuates late asthmatic reactions following allergen challenge in mild asthmatics: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical cross-over-trial. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2006;19(4):233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2005.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munoz FM, Hawkins EP, Bullard DC, Beaudet AL, Kaplan SL. Host defense against systemic infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae is impaired in E-. P-, and E-/Pselectin-deficient mice. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:2099–2106. doi: 10.1172/JCI119744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]