Abstract

Bacteria produce different types of biofilms under distinct environmental conditions. Vibrio fischeri has the capacity to produce at least two distinct types of biofilms, one that relies on the symbiosis polysaccharide Syp and another that depends upon cellulose. A key regulator of biofilm formation in bacteria is the intracellular signaling molecule cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP). In this study, we focused on a predicted c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase encoded by the gene binA, located directly downstream of syp, a cluster of 18 genes critical for biofilm formation and the initiation of symbiotic colonization of the squid Euprymna scolopes. Disruption or deletion of binA increased biofilm formation in culture and led to increased binding of Congo red and calcofluor, which are indicators of cellulose production. Using random transposon mutagenesis, we determined that the phenotypes of the ΔbinA mutant strain could be disrupted by insertions in genes in the bacterial cellulose biosynthesis cluster (bcs), suggesting that cellulose production is negatively regulated by BinA. Replacement of critical amino acids within the conserved EAL residues of the EAL domain disrupted BinA activity, and deletion of binA increased c-di-GMP levels in the cell. Together, these data support the hypotheses that BinA functions as a phosphodiesterase and that c-di-GMP activates cellulose biosynthesis. Finally, overexpression of the syp regulator sypG induced binA expression. Thus, this work reveals a mechanism by which V. fischeri inhibits cellulose-dependent biofilm formation and suggests that the production of two different polysaccharides may be coordinated through the action of the cellulose inhibitor BinA.

Bacterial biofilms play important roles in the environment and in interactions with eukaryotic hosts (for reviews, see references 17 and 32). Exopolysaccharides are a major component of biofilms (23), and many bacteria, including Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli, and Salmonella spp., have the ability to produce multiple different exopolysaccharides (23). For some of these bacteria, it has been demonstrated that the different polysaccharides contribute to biofilm formation in different settings. For example, several strains of Salmonella require an exopolysaccharide called O-antigen capsule to form biofilms on human gallstones but not to form biofilms on glass or plastic (11). Conversely, the exopolysaccharides cellulose and colanic acid are required for optimal biofilm formation by Salmonella spp. on glass and plastic but are not required for biofilm formation on human gallstones (11, 35). For some bacteria, a particular exopolysaccharide promotes attachment to one surface but seems to interfere with attachment to other surfaces. One example of this is E. coli O157:H7, which requires the exopolysaccharides poly-β-1,6-N-acetylglucosamine (PGA), colanic acid, and cellulose for optimal binding to alfalfa sprouts and plastic (27). In contrast, these polysaccharides are not required for binding by E. coli O157:H7 cells to human intestinal epithelial (Caco-2) cells and binding was actually enhanced in cellulose and PGA mutants, suggesting that while these polysaccharides are important for attachment to sprouts and plastic, they interfere with attachment to Caco-2 cells (27).

The marine bacterium Vibrio fischeri is known to produce at least two different exopolysaccharides that play roles in biofilm formation, the symbiosis polysaccharide (Syp) and cellulose (12, 59, 60). The Syp polysaccharide is critical for the formation of a biofilm-like aggregate at the initiation of symbiosis with the Hawaiian bobtail squid Euprymna scolopes (59). The natural condition(s) under which V. fischeri cells use cellulose in biofilm formation is not yet known. However, in other bacteria, cellulose contributes to the ability to attach to a variety of surfaces, including plant roots, other plant cells, mammalian epithelial cells, glass, and plastic (27, 28, 31, 35, 37, 45).

Although V. fischeri biofilm formation appears to be important for interaction with its symbiotic host and is likely also to be important in the marine environment outside the host, wild-type V. fischeri cells do not produce substantial biofilms under a variety of standard laboratory conditions. V. fischeri's ability to form biofilms in culture, however, is greatly enhanced when the syp biosynthetic gene cluster (Fig. 1) is induced by overexpression of the response regulator SypG, the sensor kinase RscS, or the sensor kinase SypF (12, 59, 60).

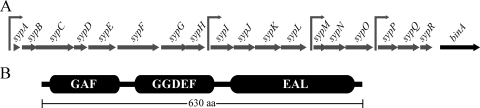

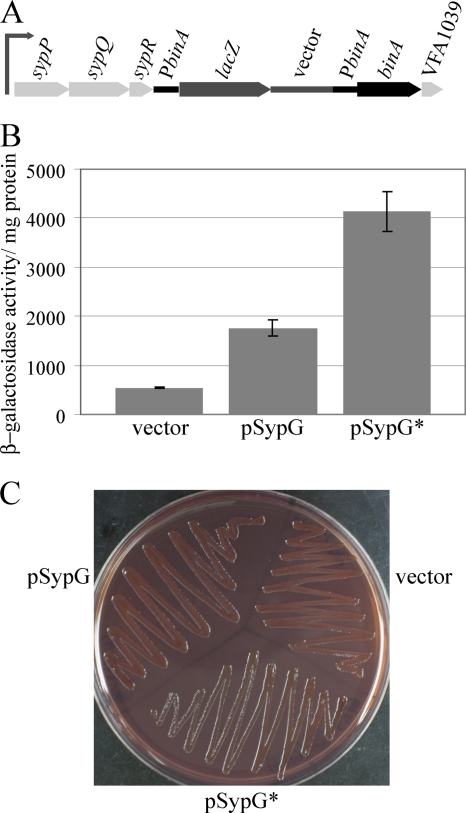

FIG. 1.

The binA gene and its predicted protein. (A) The binA gene (VFA1038) is located downstream from and oriented in the same direction as the syp gene locus. Individual genes are indicated by block arrows, and the four known or putative promoters within the syp locus are indicated by line arrows. (B) The BinA protein (630 amino acids [aa]) is predicted to have three domains, GAF (∼Q20 to L151), GGDEF (∼H205 to A338), and EAL (∼L374 to D611), as indicated. Only the EAL domain is well conserved.

In culture, V. fischeri also forms biofilms when cellulose production is induced. Cellulose contributes to the biofilms formed when either SypF or the putative response regulator VpsR is overexpressed (12). Additionally, overexpression of the diguanylate cyclase MifA induces biofilm formation and increases binding to two dyes that are cellulose indicators, Congo red and calcofluor (34, 37, 54).

The product of diguanylate cyclase activity, cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP), is an intracellular signaling molecule that plays an important role in regulating biofilm formation and motility (reviewed in references 10, 22, 38, 39, 48, and 56). C-di-GMP is produced from two GTP molecules by diguanylate cyclases with conserved GGDEF domains and is depleted by hydrolysis to linear pGpG by phosphodiesterases (PDEs) with EAL or HD-GYP domains. There is evidence of increased cellulose production in response to increased c-di-GMP levels in many bacteria (36, 41). In general, high levels of c-di-GMP enhance biofilm formation and low levels of c-di-GMP enhance motility (39).

Here we report that V. fischeri biofilm formation also increases in the absence of BinA, a GGDEF/EAL domain protein encoded by a gene that is adjacent to the syp cluster. We also report the discovery of genes involved in biofilm formation by binA mutants and the identification of amino acids that are critical to BinA activity. Finally, we suggest a mechanism by which the production of two different polysaccharides may be coordinated by BinA.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Media.

E. coli strains were grown in LB (13) or brain heart infusion broth (Difco, Detroit, MI). V. fischeri strains were grown in LBS (16, 46), SWT (60), or HMM (42) containing 0.3% Casamino Acids and 0.2% glucose (60). Congo red plates were made by the addition to LBS medium of 40 μg/ml Congo red and 15 μg/ml Coomassie blue before autoclaving. The following antibiotics were added to growth media where necessary, at the indicated final concentrations: chloramphenicol, 25 μg/ml in LB or 2.5 μg/ml in LBS; kanamycin, 50 μg/ml in LB or 100 μg/ml in LBS; tetracycline (Tc), 15 μg/ml in LB and either 5 μg/ml in LBS or 30 μg/ml in HMM; erythromycin, 150 μg/ml in brain heart infusion broth or 5 μg/ml in LBS; ampicillin, 100 μg/ml in LB. For solid media, agar was added to a final concentration of 1.5%. For motility experiments, TBS (1% tryptone, 342 mM NaCl, 0.225% agar) motility plates containing or lacking 35 mM MgSO4 were used (33).

Strains and strain construction.

The V. fischeri strains, plasmids, and primers utilized in this study are listed in Tables 1, 2, and 3, respectively. The parent V. fischeri strain used in this work was ES114, a strain isolated from E. scolopes (5). All derivatives were generated by conjugation. E. coli CC118 λpir (19) containing pEVS104 was used to carry out triparental matings as previously described (52). E. coli strains Tam1 (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA), GT115 (Invivogen, San Diego, CA), and Top10 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used for cloning and conjugations. Standard molecular biology techniques were used for all plasmid constructions. Restriction and modifying enzymes were purchased from New England Biolabs (Beverly, MA), Promega (Madison, WI), or Fermentas (Glen Burnie, MD). DNA oligonucleotides used for amplifying or modifying binA were obtained from MWG Biotech (High Point, NC). We constructed mutants by both vector integration (Campbell insertion mutagenesis [6]) and allelic replacement approaches as described previously (references 21 and 14, respectively). Mutants were verified by Southern analysis (14, 52). We complemented the binA mutant with binA located either in single copy in the chromosome at the Tn7 site or by multicopy expression from a low-copy-number plasmid. For the former complementation, we utilized a tetraparental mating approach with strains carrying pEVS104 and pUX-BF13 as described previously (14).

TABLE 1.

V. fischeri strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| ES114 | Wild type | 5 |

| KV1817 | binA::pESY10 (Cmr) | 60 |

| KV2614 | attTn7::PbinA-lacZ | This study |

| KV3818 | binA::pCMA8 (Ermr) | This study |

| KV4131 | ΔbinA | This study |

| KV4196 | ΔbinA attTn7::binA | This study |

| KV4197 | ΔbinA sypG::pAIA4 | This study |

| KV4203 | ΔbinA sypC::pBTG49 | This study |

| KV4205 | ΔbinA sypF::pCLD28 | This study |

| KV4206 | ΔbinA sypH::pESY38 | This study |

| KV4207 | ΔbinA sypJ::pTMO90 | This study |

| KV4209 | ΔbinA sypL::pTMB53 | This study |

| KV4211 | ΔbinA sypN::pTMB54 | This study |

| KV4212 | ΔbinA sypO::pTMB55 | This study |

| KV4213 | ΔbinA sypP::pCMA11 | This study |

| KV4601 | ΔbinA sypR::pTMB57 | This study |

| KV4607 | ΔbinA bcsA (VFA0884)::Tn5 (Ermr) | This study |

| KV4608 | ΔbinA bcsC (VFA0881)::Tn5 (Ermr) | This study |

| KV4611 | ΔbinA bcsZ (VFA0882)::Tn5 (Ermr) | This study |

| KV4612 | DUP [′sypR-binA′]::pEAH50 (binA+) (duplication of the sypR-binA intergenic region and insertion of lacZ) | This study |

TABLE 2.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmid | Characteristic(s) | Reference or source |

|---|---|---|

| pAIA4 | pEVS122 containing ∼500-bp sypG fragment | 21 |

| pBTG49 | pESY20 containing ∼400-bp sypC fragment | This study |

| pCLD28 | pESY20 containing ∼500-bp sypF fragment | This study |

| pCMA8 | pESY20 containing ∼300-bp binA fragment | This study |

| pCMA9 | pKV69 containing ∼1.8-kb binA sequences generated using PCR and primers 1038_SmaI_F and 1038_SmaI_R | This study |

| pCMA11 | pESY20 containing ∼400-bp sypP fragment | This study |

| pCMA13 | pJET1.2 containing ∼2-kb region downstream of binA generated by PCR with primers 1038_end_ApaIF and 1038_down_BamHIR | This study |

| pCMA14 | pJET1.2 containing ∼2-kb region upstream of binA generated by PCR with 1038_up_SpeIF and 1038_beg_ApaIR | This study |

| pCMA15 | pJET1.2 containing ∼2-kb sequences upstream and downstream of binA, generated from pCMA13 and pCMA14, for deletion of binA | This study |

| pCMA16 | pEVS79 containing ∼4-kb fragment from pCMA15 | This study |

| pCMA17 | pEVS107 containing ∼2-kb fragment of binA plus upstream regulatory sequences, generated using PCR and primers VFA1037RTF and 1038_ApaI_R, for inserting binA+ at the Tn7 site | This study |

| pCMA25 | pKV69 + binA (E402A mutation) | This study |

| pCMA27 | pKV69 + binA (L404A mutation) | This study |

| pEAH73 | pKV69 + sypG | 20 |

| pESY20 | Mobilizable suicide vector R6Kγ oriV, oriTRP4, Ermr | 34 |

| pESY38 | pESY20 containing ∼400-bp sypH fragment | This study |

| pEVS79 | High-copy-number plasmid, Cmr | 47 |

| pEVS104 | Conjugal helper plasmid (tra trb), Kanr | 47 |

| pEVS107 | Mini-Tn7, R6Kγ oriV, oriTRP4, Kanr | 29 |

| pEVS122 | R6Kγ oriV, oriTRP4, lacZα, Ermr | 15 |

| pEVS170 | Mini-Tn5 delivery plasmid, Ermr, Kanr | 26 |

| pJet1.2 | Apr Kanr cloning vector | Fermentas |

| pKV69 | Mobilizable low-copy-number vector, Tcr, Cmr | 52 |

| pKV276 | pKV69 + sypG-D53E | 20 |

| pUX-BF13 | Encodes Tn7 transposase (tnsABCDE), Apr | 3 |

| pMSM17 | pKV69 (ΔCmr) + wild-type binA (+3′ FLAG epitope sequences) | This study |

| pMSM18 | pKV69 (ΔCmr) + binA-AAL (+3′ FLAG epitope sequences) | This study |

| pMSM19 | pKV69 (ΔCmr) + binA-EAA (+3′ FLAG epitope sequences) | This study |

| pTMB53 | pEVS122 containing ∼400-bp sypL fragment | 60 |

| pTMB54 | pEVS122 containing ∼400-bp sypN fragment | 60 |

| pTMB55 | pEVS122 containing ∼400-bp sypO fragment | 60 |

| pTMB57 | pEVS122 containing ∼400-bp sypR fragment | 60 |

| pTMO90 | pEVS122 containing ∼400-bp sypJ fragment | This study |

TABLE 3.

Primers used in this study

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| 1038_end_ApaIF | GGGCCCGGTACCCCCTACTTTCACTT |

| 1038_down_BamHIR | GGATCCTCAGCGCATCAGTAATACAT |

| 1038_up_SpeIF | ACTAGTTACGCTGGTTTGCTTCTCGT |

| 1038_beg_ApaIR | GGGCCCTTCAGGAATGTCGATGGCAG |

| 1038_SmaI_F | CCCGGGAGAATAAACTGCTACTATCT |

| 1038_SmaI_R | CCCGGGTAATGATATTTTAGAGTGCC |

| 1038_ApaI_R | GGGCCCTAATGATATTTTAGAGTGCC |

| VFA1037RTF | CGTGAAATCCCTTATTTTAGTG |

| Phos_lacZ_up_rev | CCTGTGTGAAATTGTTATCCG |

| 1038AAL | AAATGGATTGGTTGTGCCGCGCTATTACGTTGG |

| 1038EAA | GGATTGGTTGTGAAGCGGCATTACGTTGGAATCACCC |

| binA-FLAG-NcoI-R | AAAAAACCATGGTTATTTATCATCATCATCTTTATAATCCACAAAGTGAAAGTAGGGGG |

To determine which genes contribute to biofilm formation by the ΔbinA mutant strain, we performed a random transposon (Tn) mutagenesis of the ΔbinA mutant strain using the mini-Tn5 delivery vector pEVS170 (26). To determine the locations of specific Tn insertions, the Tn and flanking DNA were cloned using the origin of replication within the Tn as follows. Chromosomal DNA was isolated and digested with HhaI, which cuts outside of the Tn. Following ligation, E. coli cells were transformed and plasmid-containing cells were selected with erythromycin. The Tn insertion site was then determined by sequencing from the Tn end into the flanking chromosomal DNA.

We generated the binA EAL domain mutations (resulting in codon changes E402A and L404A) using the Change-IT kit (USB, Cleveland, OH) with template pCMA9, which contains the wild-type binA gene, and phosphorylated primers Phos-lacZ-up-rev and either 1038AAL or 1038EAA, respectively. The binA gene was sequenced from the resulting clones, pCMA25 and pCMA27, to verify the presence of only the desired mutation. To verify the stability of the mutant proteins, we generated FLAG epitope derivatives. To do so, we used primers 1038_SmaI_F and binA-FLAG-NcoI-R in PCRs with pCMA9, -25, and -27 as templates, followed by cloning to obtain pMSM17, -18, and -19.

Crystal violet-based biofilm assays.

Crystal violet was used to assess biofilm formation as follows. Strains were grown statically in HMM (with Tc, as appropriate) at room temperature (22 to 23°C) overnight and then subcultured into 3 ml of fresh medium with a starting optical density (OD) of ∼0.1 and grown statically for 72 h (in the absence of added antibiotics) or 96 h (when antibiotics were present). Biofilms at the air-liquid interface were visualized by the slow addition of 1 ml of 1% crystal violet and incubation for 30 min, followed by rinsing with deionized water. We quantified staining by adding 2 ml 100% ethanol, vortexing with glass beads, and then measuring the OD at 600 nm. Alternatively, strains were grown with shaking at 28°C (both overnight and following subculturing) for 48 h and then crystal violet was added as described above.

Calcofluor staining.

To further assess cellulose production, calcofluor was used. Strains were grown as described above for the crystal violet staining of static cultures. A concentrated stock of calcofluor (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) was made as a 0.2% solution in 1 M Tris, pH 9.0, which was autoclaved to dissolve the reagent. Biofilms were visualized by the addition of 1 ml of 0.2% calcofluor and incubation for 30 min, followed by rinsing with deionized water and exposure to UV light.

Migration assays.

We monitored motility as described previously (33, 34). Briefly, we grew V. fischeri strains in TBS to an OD (600 nm) of ∼0.3 and then spotted 10-μl aliquots onto TBS or TBS-Mg2+ motility plates. We measured the diameter of the outer migrating band hourly over the course of 4 to 5 h of incubation at 28°C (55).

Quantification of c-di-GMP levels.

To measure intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations, V. fischeri strains were grown statically in HMM overnight at room temperature, subcultured (400 μl of overnight culture into 40 ml of HMM), and then grown statically at room temperature for 72 h. Each culture was mixed with 205 μl of cold 0.19% formamide and incubated on ice for 10 min. Samples were centrifuged at 6,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C. The pellets were resuspended in 300 μl of cold 80% acetonitrile-0.1% formic acid, vortexed for 30 s, and incubated on ice for 10 min. The samples were then centrifuged at top speed in a microcentrifuge, and the supernatants were removed and stored at −80°C until liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry was performed using a Waters Acquity Ultra Performance liquid chromatograph connected to a Quatro Premeir XE mass spectrometer (Micromass Technologies). A bridged ethyl hybrid C18 Ultra Performance liquid chromatography column (50 by 2.1 mm, 1.7 μm; Waters) was used for separation using solvents described previously (53). The amount of c-di-GMP in our samples was estimated using a standard curve generated from c-di-GMP standards with concentrations of 0.12 μM, 1.1 μM, and 3.3 μM. We then estimated the intracellular concentration of c-di-GMP using 3.93 × 10−16 liters as the volume of a single cell and the number of bacteria in each sample as determined by colony count from the original culture.

Western immunoblot analysis.

The expression of mutant BinA proteins was verified using FLAG epitope-tagged versions of the proteins produced in the ΔbinA mutant (KV4131) from plasmids pMSM17 (wild-type BinA), pMSM18 (BinA-AAL), and pMSM19 (BinA-EAA). Cells were grown with shaking in HMM containing Tc overnight. One-milliliter samples were pelleted, resuspended in loading buffer, and boiled, and a portion (15 μl) was loaded onto a 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoretic separation, proteins were transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride membrane and probed with anti-FLAG antibodies (Sigma). Bands were visualized with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody and ECL reagents.

β-Galactosidase assay.

To assay transcription of the binA gene, we grew V. fischeri with shaking in HMM-Tc at 28°C overnight and then subcultured it into fresh HMM-Tc. The cultures were then grown with shaking at 28°C for 24 h. Samples were then assayed for β-galactosidase activity (30). The amount of protein in the extract was determined using the Lowry assay (25), and the β-galactosidase activity per milligram of protein in the sample was calculated.

RESULTS

BinA is a putative c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase that inhibits biofilm formation.

Immediately adjacent to and downstream of the syp locus is a gene, VFA1038, that encodes a 630-amino-acid protein predicted to be involved in metabolism of the second messenger c-di-GMP (Fig. 1A). This putative protein contains both EAL and GGDEF domains (Fig. 1B), which are associated with c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase activity and diguanylate cyclase activity, respectively (reviewed in references 18 and 22). The EAL domain is highly conserved, with an EAL cd01948 E value of 4.00E-68. The GGDEF domain is much less conserved, with only 3 of 10 active-site residues conserved and a GGDEF cd01949 E value of 0.002. In addition, the I site, a sequence often located N terminal to the GGDEF motif that is involved in binding c-di-GMP (7, 8), was absent in VFA1038. Because the EAL domain is highly conserved and the GGDEF domain is poorly conserved, we hypothesized that the protein encoded by VFA1038 functions as a c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase.

Since VFA1038 is predicted to encode a protein involved in the metabolism of c-di-GMP, an important regulator of biofilm formation, and VFA1038 is adjacent to the syp cluster, a locus known to be involved in biofilm formation, we asked whether VFA1038 plays a role in biofilm formation by V. fischeri. We found that two different VFA1038 insertional mutants exhibited increased biofilm formation, as observed through an increase in crystal violet staining of the test tube surface following growth of the mutants in static minimal medium (data not shown). Due to these results and others described below, we propose to name this gene binA, for biofilm inhibition.

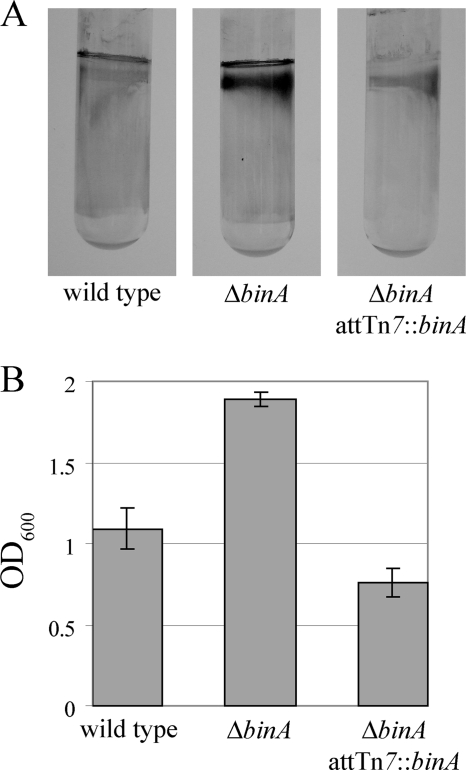

To confirm that disruption of binA was responsible for the increased biofilm formation, rather than a polar effect or a secondary mutation, we constructed an in-frame binA deletion (ΔbinA) mutant (KV4131). Like the insertional mutants, when grown statically, the ΔbinA mutant exhibited enhanced biofilm formation, relative to that of wild-type V. fischeri, as measured by the crystal violet assay (Fig. 2). Complementation of the ΔbinA mutant by the insertion of a single copy of binA at the Tn7 site (KV4196) in the chromosome (Fig. 2) restored biofilm formation to low, wild-type levels. These results confirmed that loss of binA is responsible for enhanced biofilm formation in the mutants and indicated that BinA is indeed an inhibitor of biofilm formation.

FIG. 2.

Biofilm formation by the binA mutant. V. fischeri strains ES114 (wild type), KV4131 (ΔbinA), and KV4196 (ΔbinA/attTn7::binA+) were grown statically for 72 h in HMM at room temperature and then analyzed for biofilm formation by crystal violet staining (A). Crystal violet staining was subsequently quantified from a triplicate set of tubes (B). Error bars represent ±1 standard deviation.

The syp polysaccharide is not a major component of biofilms produced by the binA mutants.

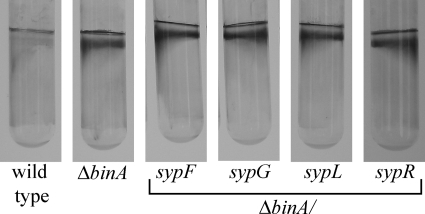

Because of the proximity of binA to the syp cluster, we hypothesized that biofilm formation by the binA mutants depends on the syp locus. To test this possibility, we constructed a series of double mutants and assayed static biofilm formation. The double mutants were obtained with the ΔbinA mutant strain by insertional mutagenesis of the sypC, sypF, sypG, sypH, sypJ, sypL, sypN, sypO, sypP, and sypR genes (Table 1). All of the double mutants produced biofilms that were indistinguishable from that of the ΔbinA mutant, as evaluated by crystal violet staining (Fig. 3 and data not shown). These data indicate that the syp polysaccharide is not a major part of the biofilm formed by the ΔbinA mutant. Thus, the activity of BinA must be directed at another target.

FIG. 3.

Biofilm formation by binA syp double mutants. Mutants defective for both binA and various syp genes (KV4205, KV4197, KV4209, and KV4601) were analyzed for biofilm formation using the crystal violet assay following 72 h of static growth in HMM at room temperature. The assay was performed multiple times in triplicate using the double mutants indicated in the text; shown are a representative data set.

Both Congo red and calcofluor binding are enhanced in binA mutants.

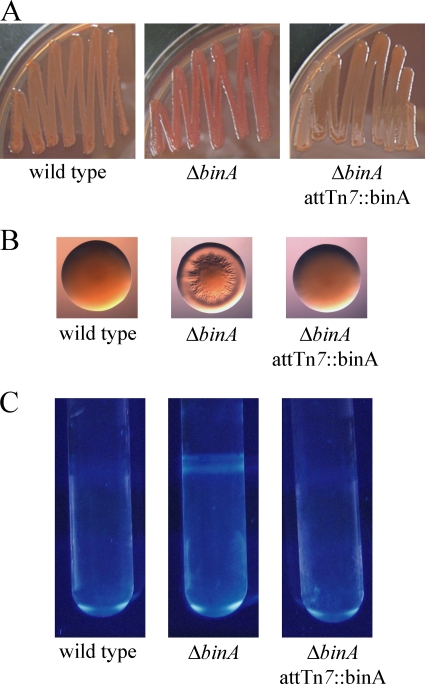

Because the activity of BinA in inhibiting biofilm formation was not directed at the syp locus, we sought to understand its role by using assays commonly found in the biofilm literature. In particular, increased biofilm formation is often associated with increased binding of the dyes Congo red and calcofluor. The binding of Congo red correlates, in many cases, with the production of cellulose and/or curli (e.g., see references 9 and 50). Calcofluor binds β-1,3 or β-1,4 linkages between d-glucopyranosyl units, such as those in cellulose (37, 54). When plated on Congo red plates, both insertion and deletion mutants of binA formed colonies that were darker red than those of wild-type V. fischeri (Fig. 4A and data not shown). In addition, the binA mutants formed wrinkled colonies, while those of the wild type were smooth (Fig. 4B and data not shown). Interestingly, this wrinkling phenotype did not occur when Congo red was absent from the base medium (LBS), indicating that Congo red actually stimulates wrinkled-colony formation by the binA mutant. Regardless of the cause, both the color and wrinkled-colony phenotypes were complemented by the addition of binA, either in single copy in the chromosome or on a plasmid (Fig. 4A and B and data not shown).

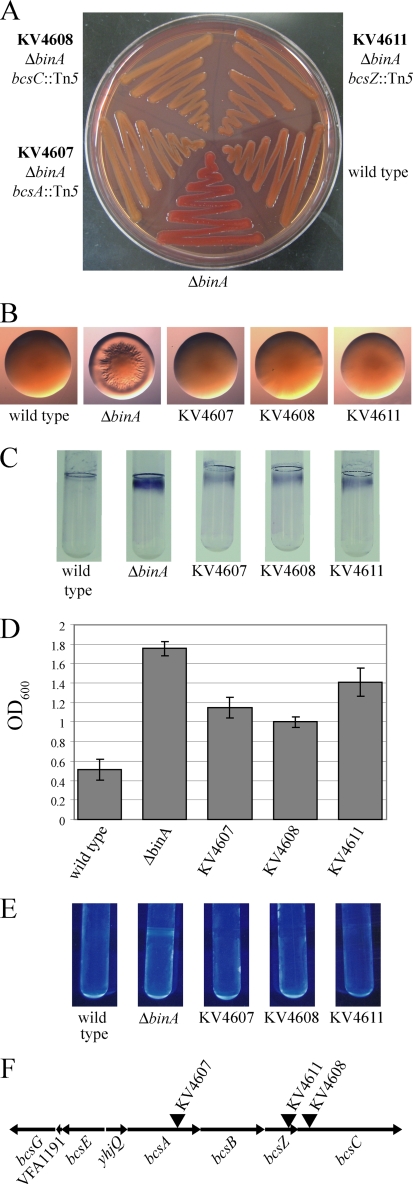

FIG. 4.

BinA inhibits Congo red binding, wrinkled-colony formation, and Calcofluor binding. Congo red binding (A) and colony morphology (B) were assessed after 48 h of growth at room temperature on Congo red plates. (C) Calcofluor staining was assayed after 72 h of static growth in HMM at room temperature. The strains are the same as those indicated in Fig. 2.

We also assayed calcofluor binding on plates and in liquid culture. With both approaches, the binA mutants exhibited increased calcofluor binding compared to wild-type V. fischeri (Fig. 4C and data not shown). The increased ability to bind calcofluor could be complemented by the introduction of a wild-type copy of binA (Fig. 4C). Together, these data indicate that BinA inhibits the production of a sugar with β-1,3 or β-1,4 d-glucose linkages, possibly cellulose.

Cellulose biosynthetic genes are required for biofilm formation by the ΔbinA mutant strains.

To identify the genes that contribute to biofilm formation by the binA mutants, we performed a random Tn mutagenesis of the ΔbinA mutant. Because the ΔbinA mutant produces colonies that are darker red than wild-type V. fischeri on Congo red plates (Fig. 4A), we screened for Tn mutants that had decreased colony color on Congo red plates. In a small screening of about 3,000 colonies, we identified eight mutants with either a white or a light red color (Fig. 5A and data not shown). Each of these colonies also failed to form wrinkled colonies (Fig. 5B and data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Role of the cellulose operon in biofilm formation. Congo red binding (A) and colony morphology (B) were assessed after 48 h of growth at room temperature on Congo red plates. Crystal violet staining was visualized (C) and quantified (D) after 72 h of static growth in HMM at room temperature. Error bars represent ±1 standard deviation from a triplicate set of tubes. (E) Calcofluor staining was assessed after 72 h of static growth in HMM at room temperature. (F) The bcs locus (VFA0887 to VFA0881) with the locations of the Tn insertions indicated by inverted triangles.

Southern analysis indicated that seven of the eight strains contained a clean single Tn insertion (data not shown). Among the seven strains with a single insertion, there were five different banding patterns, indicating five distinct Tn insertions (data not shown). We cloned and sequenced the Tn and flanking DNA from the five distinct insertion mutants. Each of the Tns in these strains had been inserted into the bacterial cellulose synthesis (bcs) locus (Fig. 5F and data not shown).

We chose to further characterize the bcsA, bcsZ, and bcsC mutants indicated in Fig. 5F by examining the ability of these mutants to form biofilms. Each of the ΔbinA bcs mutants exhibited reduced crystal violet staining compared to that of the ΔbinA mutant parent (Fig. 5C and D and data not shown); however, it was not reduced to the level of the wild type (Fig. 5C and D). These data suggested that BinA inhibits another component of biofilm formation in addition to cellulose or that some cellulose production was still possible in these double mutants. In support of the former hypothesis, disruption of the bcs operon eliminated all of the calcofluor staining observed with the binA mutant (Fig. 5E). Together, these data indicate that BinA is a negative regulator of cellulose production and that cellulose is a major contributor to biofilm formation by the ΔbinA mutant.

Overexpression of BinA enhances motility.

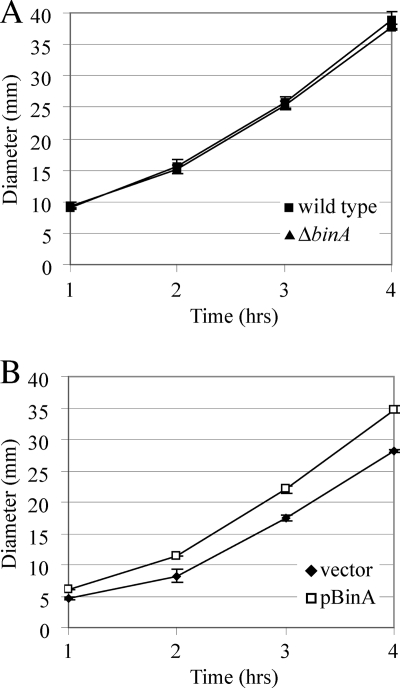

In general, c-di-GMP promotes biofilm formation and thus, loss of a c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase is often correlated with an increase in biofilm formation (18, 22, 39). Indeed, our data to date are consistent with the predicted role of BinA as a c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase. Alterations in c-di-GMP levels are also correlated with altered motility: increased c-di-GMP levels often correlate with decreased motility and decreased c-di-GMP levels with increased motility. Therefore, to determine if BinA plays a role in regulating motility in V. fischeri, we tested the ability of the binA deletion mutant (KV4131) to migrate on motility plates. Migration by the binA deletion mutant was indistinguishable from that of wild-type V. fischeri ES114 (Fig. 6A). That deletion of binA increases biofilm formation but has no effect on motility indicates some specificity in the role of BinA. However, when BinA was overexpressed from a multicopy plasmid, V. fischeri exhibited increased migration compared to V. fischeri with a vector control (Fig. 6B). Thus, based on other examples in the literature (22), we propose that overexpression of BinA likely extends its predicted phosphodiesterase activity beyond its natural role, decreasing c-di-GMP levels in such a way that motility is enhanced.

FIG. 6.

Motility of binA mutant and overexpression strains. The motility of V. fischeri strains was monitored by measuring the diameter of the outer chemotaxis ring formed in TBS-Mg2+ soft agar over time. (A) Motility of the ΔbinA mutant (KV4131) and its wild-type parent ES114. (B) Motility of wild-type strain ES114 carrying the control vector pKV69 or the binA overexpression plasmid pCMA9 (pBinA). Error bars represent ±1 standard deviation.

BinA activity depends on the EAL domain.

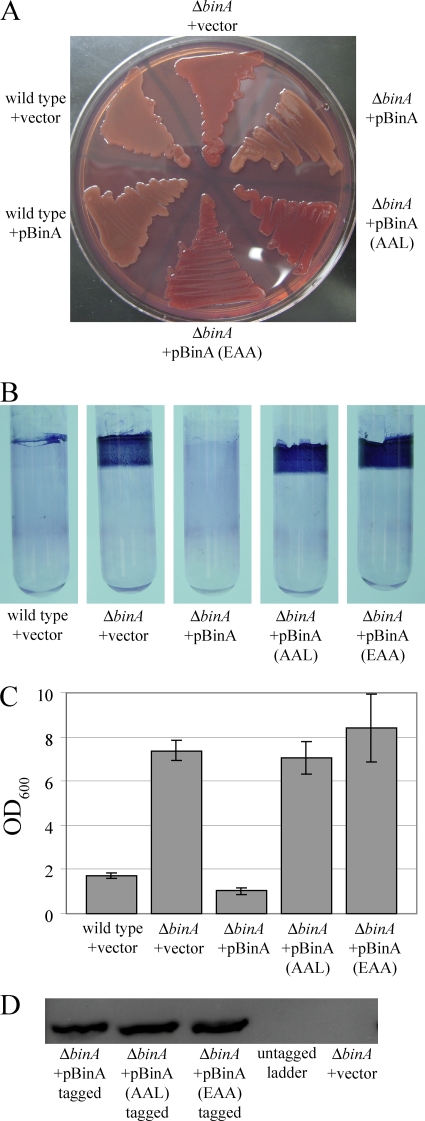

Thus, far, the data from bioinformatics, biofilm assays, and motility experiments are consistent with the hypothesis that BinA functions as a c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase. Typically, amino acid residues E and L of the EAL domain are required for c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase activity (4, 24, 49). Therefore, we asked if the activity of BinA indeed requires an intact EAL domain. To address this question, we constructed plasmids that overexpressed mutant alleles of binA. Specifically, we altered codons within the EAL domain to convert EAL to EAA (E402A) and AAL (L404A) to obtain BinA(EAA) and BinA(AAL), respectively.

To determine if these mutations altered BinA activity, we tested the ability of BinA(EAA) and BinA(AAL) to reduce Congo red binding by the ΔbinA mutant. Overproduction of wild-type BinA in the ΔbinA mutant reduced Congo red binding to levels similar to that of the wild-type control (Fig. 7A). In contrast, overproduction of BinA-EAA or BinA-AAL failed to reduce Congo red binding (Fig. 7A), suggesting that these proteins were inactive. We also assayed the activity of BinA(EAA) and BinA(AAL) during growth in culture. Specifically, we analyzed biofilms that formed during growth with shaking, as we found that these conditions resulted in impressive biofilm formation by the vector-containing ΔbinA mutant that was fully complemented by overexpression of wild-type BinA (Fig. 7B and C). Under these conditions, the activity of BinA(EAA) and BinA(AAL) was undetectable (Fig. 7B and C). Independent experiments using tagged versions of the three proteins demonstrated that under these shaking growth conditions, the proteins were stably produced (Fig. 7D). Thus, in both Congo red and crystal violet assays, activity of BinA depends on the EAL residues, providing evidence that BinA functions as a c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase.

FIG. 7.

Role of the EAL motif in BinA activity. The effect on BinA activity of mutating the EAL motif to AAL or EAA was monitored using Congo red binding (A) and crystal violet staining (B) of cultures grown in HMM-Tc under shaking conditions for 48 h at 28°C. Crystal violet staining was subsequently quantified from a triplicate set of tubes (C); error bars represent ±1 standard deviation. (D) Western immunoblot analysis of tagged versions of the BinA protein. BinA-expressing plasmids pMSM17, -18, and -19 were introduced into binA mutant KV4131. Whole-cell extracts were processed as described in Materials and Methods.

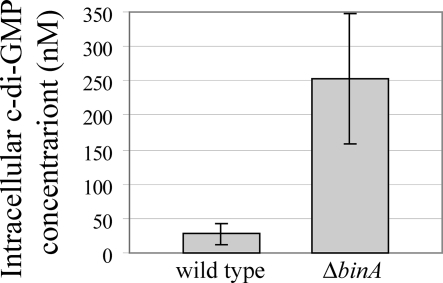

Loss of binA increases c-di-GMP levels.

Because together our data suggested that BinA is a c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase, we hypothesized that the levels of c-di-GMP would increase in a binA mutant. To test this hypothesis, we measured c-di-GMP concentrations in wild-type and ΔbinA mutant cells using high-pressure liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. We found the average c-di-GMP concentration to be significantly higher in ΔbinA mutant cells (approximately 253 nM) than in wild-type cells (approximately 27.4 nM) (Fig. 8). These data verify the assignment of BinA as a c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase.

FIG. 8.

Intracellular c-di-GMP concentrations. Each bar represents the average intracellular c-di-GMP concentration of three samples. The sample concentrations ranged from 0 nM to 53.4 nM for wild-type V. fischeri and from 86.7 nM to 413 nM for the ΔbinA mutant (KV4131). The error bars represent ±1 standard error of the mean.

Connection to the syp locus.

Given the location and orientation of the binA gene (Fig. 1A), we wondered whether expression of binA could be influenced by transcriptional activity at the nearby syp locus. In particular, overexpression of the response regulator SypG is known or predicted to induce transcription at four promoters (upstream of sypA, sypI, sypM, and sypP) (60). SypG is predicted to be a σ54-dependent activator, and these four syp promoters are known or predicted to be σ54 dependent (60) (Fig. 1A). In contrast, there are no predicted σ54 promoter sequences in the 220-bp intergenic region between sypR and binA. To test whether binA transcription is influenced by SypG overexpression, we first assayed the reporter activity of a strain with the sypR-binA intergenic region fused to lacZ at a site distal to the syp locus (the Tn7 site) and found no significant induction by SypG (data not shown). These data are consistent with the lack of predicted σ54-dependent promoter sequences in that region. Next, we assayed reporter activity from a strain that contained the reporter at the binA locus; this strain contains a wild-type copy of binA at its native position (Fig. 9A). We found that overexpression of sypG and the increased-activity allele sypG* induced binA expression three- and sevenfold, respectively (Fig. 9B). These data suggest that there may be some readthrough from transcription of the syp locus, presumably the sypPQR operon (Fig. 1A and 9A). In support of a possible functional connection, we found that overproduction of SypG* caused a decrease in cellulose biosynthesis, as measured by dye binding on Congo red plates, independent of syp function (assayed in a sypN mutant) (Fig. 9C). However, overproduction of SypG* also caused a visible decrease in Congo red binding in a binA sypN mutant (data not shown), indicating that SypG may also have a BinA-independent effect on cellulose biosynthesis. These experiments further suggest coordination between syp and cellulose but indicate that additional factors are involved.

FIG. 9.

Impact of the syp regulator SypG on binA expression and activity. (A) Diagram of the chromosomal region of the reporter strain KV4612, which contains pEAH50 inserted by homologous recombination with the sypR-binA intergenic region; this region is labeled PbinA for simplicity, although it is not known whether a promoter exists there. The 3′ end of sypR, the sypR-binA intergenic region, and the 5′ end of the binA gene are duplicated in the strain; one wild-type copy of binA is present. The drawing is not to scale. (B) β-Galactosidase activities of the binA mutant reporter strain KV4612 carrying the control plasmid pKV69 (vector), SypG overexpression plasmid pEAH73 (SypG), and SypG-D53E increased-activity allele plasmid pKV276 (SypG*). (C) Congo red binding by sypN mutant strain KV1838 carrying the indicated plasmids after 48 h of growth on a Congo red plate at room temperature.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated the function of the putative c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase BinA. One of the key roles for enzymes involved in c-di-GMP metabolism is to control biofilm formation. Indeed, we found that disruption of binA caused an increase in biofilm formation, as assayed by crystal violet staining. This increase in biofilm formation was due to increased cellulose production, as evident both from phenotypic assays of the binA mutant (Congo red and calcofluor assays) and from genetic studies in which disruption of the cellulose locus (bcs) restored wild-type phenotypes to the binA mutant. Thus, it appears that under standard laboratory conditions, V. fischeri turns off cellulose production using BinA.

Several lines of evidence support the assignment of BinA as a c-di-GMP phosphodiesterase. First, bioinformatics showed a strong conservation of the EAL domain, including key residues in the signature motif. Second, phosphodiesterase activity is often associated with decreased biofilm formation and increased motility, and this is true for BinA: disruption of binA increased biofilm formation, and its overexpression increased motility (Fig. 2 and 6). Third, replacement of critical amino acids within the EAL signature motif disrupted BinA function (Fig. 7). Fourth, our measurements using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry indicated that c-di-GMP concentrations are significantly higher in ΔbinA mutant cells than in wild-type cells (Fig. 8).

There is precedence for “dual-domain” proteins (containing both GGDEF and EAL domains) to exhibit only diguanylate cyclase or only phosphodiesterase activity; generally, the activity corresponds to the well-conserved domain. For example, the Pseudomonas aeruginosa GGDEF/EAL domain protein BifA functions as a phosphodiesterase (24). Since our data are consistent with BinA functioning as a phosphodiesterase and because the putative GGDEF domain of BinA is poorly conserved, containing only 3 of 10 key active-site residues, BinA may be a dual-domain protein with only phosphodiesterase activity. Furthermore, the I site was absent, suggesting that the GGDEF domain likely does not even function in c-di-GMP binding. There are also examples in which the GGDEF or EAL domain has evolved away from enzymatic activity yet retains a function. One pertinent example is E. coli YcgF, an EAL domain protein that lacks phosphodiesterase activity yet appears to participate in protein-protein interactions (51). In our experiments, we observed that the BinA(AAL) and BinA(EAA) proteins retained residual activity during static growth in culture, as assayed by crystal violet staining (data not shown). Thus, it is possible that a non-enzymatically active BinA protein participates in protein-protein interactions. The influences of the GGDEF domain and also the putative GAF domain, which in other bacteria is involved in sensing environmental signals (2), on the activity of the BinA protein remain to be determined.

V. fischeri encodes 48 proteins with GGDEF and/or EAL domains. Only three other such V. fischeri proteins have been characterized: VFA1012, a GGDEF and REC domain protein for which no phenotype has yet been uncovered (21), and the diguanylate cyclases MifA and MifB, which are involved in the control of motility in the absence of magnesium (34). Loss of binA did not impact motility, regardless of whether magnesium was present or not (Fig. 6A and data not shown). These data suggest some level of specificity to the role of BinA. Although, in general, the regulation of c-di-GMP levels and localization in bacteria is poorly understood, it seems clear that there can be localized effects, based on the actions of diguanylate cyclases, phosphodiesterases, and proteins that bind c-di-GMP. The diguanylate cyclase(s) that promotes cellulose production in V. fischeri is as yet unknown. However, the c-di-GMP binding protein is likely to be BcsA (Fig. 5F), by analogy with Gluconoacetobacter xylinus. It was in G. xylinus that c-di-GMP was initially uncovered and shown to be an allosteric effector of cellulose synthetic activity (40). BcsA is now known to contain a PilZ domain, one of several c-di-GMP binding domains (1, 44). V. fischeri has four genes predicted to encode PilZ domain proteins, bcsA, VF0527, VF0556, and VF1838 (1). Of these, disruption of only bcsA impacted biofilm formation by the binA mutant (Fig. 5 and data not shown). Because PilZ is not the only class of c-di-GMP binding proteins, it is possible that another, as yet unidentified, c-di-GMP binding protein could be impacted by BinA activity, such as a transcriptional regulator of bcs transcription.

While investigating the role of the cellulose locus, we found that mutations in bcs did not completely disrupt biofilm formation, as monitored by crystal violet staining (Fig. 5C). These data suggested that BinA negatively controls an additional biofilm component. One possibility could be expression of pili, which are a component of biofilm formation in many bacteria. V. fischeri encodes upwards of 10 pilus loci (43). However, our preliminary transmission electron microscopy experiments failed to uncover any evidence that pili were upregulated in the binA mutant (unpublished data). V. fischeri also has additional loci potentially involved in polysaccharide biosynthesis. One of these is a locus with some similarity to the Vibrio polysaccharide (vps-II) locus of V. cholerae (57, 58). Disruption of two genes within the vps-II-like locus of V. fischeri did not noticeably alter crystal violet staining of the binA mutant (unpublished data). However, it is likely that the construction of a triple mutant (binA bcs vps-II) would be necessary to eliminate a possible role for vps-II in the residual biofilm formation of the double mutant. It is worth noting here that in the course of experiments designed to understand the residual biofilm formation of this strain, we observed some influence of antibiotic addition on our biofilm phenotypes. Specifically, we found that Tc-based selection for the vector control in the binA bcsA double mutant eliminated the residual biofilm observed in static cultures (data not shown). In contrast, Tc-based selection for the vector control in the ΔbinA mutant promoted the dramatic biofilm formation observed following growth of the culture with shaking (Fig. 7B); in the absence of Tc, the parent ΔbinA mutant strain failed to form biofilms under the same conditions (unpublished data). Although these observations do not change any of our conclusions, they suggest a response to antibiotic treatment that needs to be characterized and point to the need for appropriate comparison sets.

We initiated our studies of binA because of the location and orientation of this gene with respect to the syp locus (Fig. 1A), hypothesizing that BinA would be involved in the control of Syp polysaccharide biosynthesis. Although this was not the case, other connections remained possible. Indeed, we found that the syp regulator and putative σ54-dependent activator SypG could induce binA transcription. The induction likely occurred via readthrough from the adjacent sypP promoter (Fig. 1A and 9A), because the binA promoter region does not contain a putative σ54-dependent promoter, and the binA promoter region fused to the lacZ reporter located at a site distal to the binA gene was not activated by SypG overexpression. These data suggest that syp cluster activation could indirectly increase the level of BinA protein, thus turning down cellulose production. Thus, potentially BinA coordinates an increase in syp polysaccharide production with a decrease in cellulose production. The timing and pattern of syp expression during colonization have not yet been determined. However, it is known that syp is required for symbiosis and at least one of the syp genes is required for the formation of a biofilm-like aggregate at the initiation of symbiosis (59, 60), suggesting that syp might be induced early in colonization. Further tests of this model will depend upon determining the conditions under which the two loci are naturally expressed, but BinA could potentially play a role in the transition from a cellulose-containing biofilm, possibly important in the marine environment, to a Syp-containing biofilm at the initiation of symbiosis. Disruption of the binA gene does not interfere with symbiosis (60); thus, either cellulose does not interfere with the function of the Syp polysaccharide or BinA is a redundant cellulose regulator under those environmental conditions.

In summary, in this work we have uncovered a mechanism by which V. fischeri prevents biofilm formation. This control mechanism is significant because it suggests that under certain environmental conditions it is disadvantageous to produce cellulose. It will be of interest to determine when cellulose production is induced and becomes important. Because of the medical importance of biofilm formation—and the accumulating evidence that environmental biofilms can provide a reservoir for infectious organisms—understanding how different organisms modulate different types of biofilms is key for the effective design of new antimicrobial treatments.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Chris Waters for his assistance with high-pressure liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry experiments designed to measure c-di-GMP levels in V. fischeri, Michael Misale for construction of tagged BinA mutants and Western blot analysis, and Satoshi Shibata for his assistance with electron microscopy. We also thank past and present members of the Wolfe and Visick labs for their input and critical reading of the manuscript and past and present members of the Visick lab for plasmid constructions.

This work was supported by NIH R01 grant GM59690 to K.L.V.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 January 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amikam, D., and M. Y. Galperin. 2006. PilZ domain is part of the bacterial c-di-GMP binding protein. Bioinformatics 22:3-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aravind, L., and C. P. Ponting. 1997. The GAF domain: an evolutionary link between diverse phototransducing proteins. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22:458-459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bao, Y., D. P. Lies, H. Fu, and G. P. Roberts. 1991. An improved Tn7-based system for the single-copy insertion of cloned genes into chromosomes of Gram-negative bacteria. Gene 109:167-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bobrov, A. G., O. Kirillina, and R. D. Perry. 2005. The phosphodiesterase activity of the HmsP EAL domain is required for negative regulation of biofilm formation in Yersinia pestis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 247:123-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boettcher, K. J., and E. G. Ruby. 1990. Depressed light emission by symbiotic Vibrio fischeri of the sepiolid squid Euprymna scolopes. J. Bacteriol. 172:3701-3706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Campbell, A. 1962. Episomes. Adv. Genet. 11:101-145. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan, C., R. Paul, D. Samoray, N. C. Amiot, B. Giese, U. Jenal, and T. Schirmer. 2004. Structural basis of activity and allosteric control of diguanylate cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101:17084-17089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christen, B., M. Christen, R. Paul, F. Schmid, M. Folcher, P. Jenoe, M. Meuwly, and U. Jenal. 2006. Allosteric control of cyclic di-GMP signaling. J. Biol. Chem. 281:32015-32024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Collinson, S. K., P. C. Doig, J. L. Doran, S. Clouthier, T. J. Trust, and W. W. Kay. 1993. Thin, aggregative fimbriae mediate binding of Salmonella enteritidis to fibronectin. J. Bacteriol. 175:12-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cotter, P. A., and S. Stibitz. 2007. c-di-GMP-mediated regulation of virulence and biofilm formation. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10:17-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crawford, R. W., D. L. Gibson, W. W. Kay, and J. S. Gunn. 2008. Identification of a bile-induced exopolysaccharide required for Salmonella biofilm formation on gallstone surfaces. Infect. Immun. 76:5341-5349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Darnell, C. L., E. A. Hussa, and K. L. Visick. 2008. The putative hybrid sensor kinase SypF coordinates biofilm formation in Vibrio fischeri by acting upstream of two response regulators, SypG and VpsR. J. Bacteriol. 190:4941-4950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis, R. W., D. Botstein, and J. R. Roth. 1980. Advanced bacterial genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 14.DeLoney, C. R., T. M. Bartley, and K. L. Visick. 2002. Role for phosphoglucomutase in Vibrio fischeri-Euprymna scolopes symbiosis. J. Bacteriol. 184:5121-5129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunn, A. K., M. O. Martin, and E. Stabb. 2005. Characterization of pES213, a small mobilizable plasmid from Vibrio fischeri. Plasmid 54:114-134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Graf, J., P. V. Dunlap, and E. G. Ruby. 1994. Effect of transposon-induced motility mutations on colonization of the host light organ by Vibrio fischeri. J. Bacteriol. 176:6986-6991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hall-Stoodley, L., and P. Stoodley. 2009. Evolving concepts in biofilm infections. Cell. Microbiol. 11:1034-1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hengge, R. 2009. Principles of c-di-GMP signalling in bacteria. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 7:263-273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrero, M., V. de Lorenzo, and K. N. Timmis. 1990. Transposon vectors containing non-antibiotic resistance selection markers for cloning and stable chromosomal insertion of foreign genes in gram-negative bacteria. J. Bacteriol. 172:6557-6567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hussa, E. A., C. L. Darnell, and K. L. Visick. 2008. RscS functions upstream of SypG to control the syp locus and biofilm formation in Vibrio fischeri. J. Bacteriol. 190:4576-4583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hussa, E. A., T. M. O'Shea, C. L. Darnell, E. G. Ruby, and K. L. Visick. 2007. Two-component response regulators of Vibrio fischeri: identification, mutagenesis and characterization. J. Bacteriol. 189:5825-5838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenal, U., and J. Malone. 2006. Mechanisms of cyclic-di-GMP signaling in bacteria. Annu. Rev. Genet. 40:385-407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Karatan, E., and P. Watnick. 2009. Signals, regulatory networks, and materials that build and break bacterial biofilms. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 73:310-347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuchma, S. L., K. M. Brothers, J. H. Merritt, N. T. Liberati, F. M. Ausubel, and G. A. O'Toole. 2007. BifA, a cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterase, inversely regulates biofilm formation and swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol. 189:8165-8178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowry, O. H., N. J. Rosebrough, A. L. Farr, and R. J. Randall. 1951. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 193:265-275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lyell, N. L., A. K. Dunn, J. L. Bose, S. L. Vescovi, and E. V. Stabb. 2008. Effective mutagenesis of Vibrio fischeri using hyperactive mini-Tn5 derivatives. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:7059-7063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Matthysse, A. G., R. Deora, M. Mishra, and A. G. Torres. 2008. Polysaccharides cellulose, poly-β-1,6-N-acetyl-d-glucosamine, and colanic acid are required for optimal binding of Escherichia coli O157:H7 strains to alfalfa sprouts and K-12 strains to plastic but not for binding to epithelial cells. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74:2384-2390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthysse, A. G., and S. McMahan. 1998. Root colonization by Agrobacterium tumefaciens is reduced in cel, attB, attD, and attR mutants. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2341-2345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McCann, J., E. V. Stabb, D. S. Millikan, and E. G. Ruby. 2003. Population dynamics of Vibrio fischeri during infection of Euprymna scolopes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 69:5928-5934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller, J. H. 1972. Experiments in molecular genetics. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 31.Monteiro, C., I. Saxena, X. Wang, A. Kader, W. Bokranz, R. Simm, D. Nobles, M. Chromek, A. Brauner, R. M. Brown, Jr., and U. Römling. 2009. Characterization of cellulose production in Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 and its biological consequences. Environ. Microbiol. 11:1105-1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moons, P., C. W. Michiels, and A. Aertsen. 2009. Bacterial interactions in biofilms. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 35:157-168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.O'Shea, T. M., C. R. DeLoney-Marino, S. Shibata, S.-I. Aizawa, A. J. Wolfe, and K. L. Visick. 2005. Magnesium promotes flagellation of Vibrio fischeri. J. Bacteriol. 187:2058-2065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.O'Shea, T. M., A. H. Klein, K. Geszvain, A. J. Wolfe, and K. L. Visick. 2006. Diguanylate cyclases control magnesium-dependent motility of Vibrio fischeri. J. Bacteriol. 188:8196-8205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Prouty, A. M., and J. S. Gunn. 2003. Comparative analysis of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium biofilm formation on gallstones and on glass. Infect. Immun. 71:7154-7158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Römling, U. 2005. Characterization of the rdar morphotype, a multicellular behaviour in Enterobacteriaceae. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62:1234-1246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Römling, U. 2002. Molecular biology of cellulose production in bacteria. Res. Microbiol. 153:205-212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Römling, U., and D. Amikam. 2006. Cyclic di-GMP as a second messenger. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9:218-228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Römling, U., M. Gomelsky, and M. Y. Galperin. 2005. C-di-GMP: the dawning of a novel bacterial signaling system. Mol. Microbiol. 57:629-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ross, P., Y. Aloni, H. Weinhouse, D. Michaeli, P. Ohana, R. Mayer, and M. Benziman. 1986. Control of cellulose synthesis in A. xylinum. A unique guanyl oligonucleotide is the immediate activator of cellulose synthase. Carbohydr. Res. 149:101-117. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ross, P., H. Weinhouse, Y. Aloni, D. Michaeli, P. Weinberger-Ohana, R. Mayer, S. Braun, E. de Vroom, G. A. van der Marel, J. H. van Boom, and M. Benziman. 1987. Regulation of cellulose synthesis in Acetobacter xylinum by cyclic diguanylic acid. Nature 325:279-281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruby, E. G., and K. H. Nealson. 1977. Pyruvate production and excretion by the luminous marine bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 34:164-169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ruby, E. G., M. Urbanowski, J. Campbell, A. Dunn, M. Faini, R. Gunsalus, P. Lostroh, C. Lupp, J. McCann, D. Millikan, A. Schaefer, E. Stabb, A. Stevens, K. Visick, C. Whistler, and E. P. Greenberg. 2005. Complete genome sequence of Vibrio fischeri: a symbiotic bacterium with pathogenic congeners. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 102:3004-3009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ryjenkov, D. A., R. Simm, U. Römling, and M. Gomelsky. 2006. The PilZ domain is a receptor for the second messenger c-di-GMP. The PilZ domain protein YcgR controls motility in enterobacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 281:30310-30314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smit, G., S. Swart, B. J. Lugtenberg, and J. W. Kijne. 1992. Molecular mechanisms of attachment of Rhizobium bacteria to plant roots. Mol. Microbiol. 6:2897-2903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stabb, E. V., K. A. Reich, and E. G. Ruby. 2001. Vibrio fischeri genes hvnA and hvnB encode secreted NAD+-glycohydrolases. J. Bacteriol. 183:309-317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Stabb, E. V., and E. G. Ruby. 2002. RP4-based plasmids for conjugation between Escherichia coli and members of the Vibrionaceae. Methods Enzymol. 358:413-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tamayo, R., J. T. Pratt, and A. Camilli. 2007. Roles of cyclic diguanylate in the regulation of bacterial pathogenesis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61:131-148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tamayo, R., A. D. Tischler, and A. Camilli. 2005. The EAL domain protein VieA is a cyclic diguanylate phosphodiesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 280:33324-33330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Teather, R. M., and P. J. Wood. 1982. Use of Congo red-polysaccharide interactions in enumeration and characterization of cellulolytic bacteria from the bovine rumen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 43:777-780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tschowri, N., S. Busse, and R. Hengge. 2009. The BLUF-EAL protein YcgF acts as a direct anti-repressor in a blue-light response of Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 23:522-534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Visick, K. L., and L. M. Skoufos. 2001. Two-component sensor required for normal symbiotic colonization of Euprymna scolopes by Vibrio fischeri. J. Bacteriol. 183:835-842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Waters, C. M., W. Lu, J. D. Rabinowitz, and B. L. Bassler. 2008. Quorum sensing controls biofilm formation in Vibrio cholerae through modulation of cyclic di-GMP levels and repression of vpsT. J. Bacteriol. 190:2527-2536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weiner, R., E. Seagren, C. Arnosti, and E. Quintero. 1999. Bacterial survival in biofilms: probes for exopolysaccharide and its hydrolysis, and measurements of intra- and interphase mass fluxes. Methods Enzymol. 310:403-426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wolfe, A. J., and H. C. Berg. 1989. Migration of bacteria in semisolid agar. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 86:6973-6977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wolfe, A. J., and K. L. Visick. 2008. Get the message out: cyclic-di-GMP regulates multiple levels of flagellum-based motility. J. Bacteriol. 190:463-475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yildiz, F. H., and G. K. Schoolnik. 1999. Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor: identification of a gene cluster required for the rugose colony type, exopolysaccharide production, chlorine resistance, and biofilm formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96:4028-4033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yildiz, F. H., and K. L. Visick. 2009. Vibrio biofilms: so much the same yet so different. Trends Microbiol. 17:109-118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yip, E. S., K. Geszvain, C. R. DeLoney-Marino, and K. L. Visick. 2006. The symbiosis regulator RscS controls the syp gene locus, biofilm formation and symbiotic aggregation by Vibrio fischeri. Mol. Microbiol. 62:1586-1600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yip, E. S., B. T. Grublesky, E. A. Hussa, and K. L. Visick. 2005. A novel, conserved cluster of genes promotes symbiotic colonization and σ54-dependent biofilm formation by Vibrio fischeri. Mol. Microbiol. 57:1485-1498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]