Abstract

Purpose

Interleukin-7 has critical and non redundant roles in T-cell development, hematopoiesis and post developmental immune functions as a prototypic homeostatic cytokine. Based on a large body of pre-clinical evidence, it may have multiple therapeutic applications in immunodeficiency states, either physiologic (immuno-senescence), pathologic (HIV) or iatrogenic (post-chemotherapy and post-hematopoietic stem cell transplant) and may have roles in immune reconstitution or enhancement of immunotherapy. We report here on the toxicity and biological activity of recombinant human IL-7 (rhIL-7) in humans.

Design

Subjects with incurable malignancy received rhIL-7 subcutaneously every other day for two weeks, in a phase I, inter-patient dose escalation study (3, 10, 30 & 60 μg/Kg/dose). The objectives were safety and dose-limiting toxicity determination, identification of a range of biologically active doses and characterization of biological and, possibly, anti-tumor effects.

Results

Mild to moderate constitutional symptoms, reversible spleen and lymph node enlargement and marked increase in peripheral CD3+, CD4+, CD8+ lymphocytes were seen in a dose dependent and age independent manner in all subjects receiving 10 μg/Kg/dose or more, resulting in a rejuvenated circulating T cell profile, resembling that seen earlier in life. In some subjects, rhIL-7 induced in the bone marrow a marked, transient polyclonal proliferation of pre B cells showing a spectrum of maturation as well as an increase in circulating transitional B-cells.

Conclusion

This study demonstrates rhIL-7's potent biologic activity in humans, over a well tolerated dose range and allows further exploration of its possible therapeutic applications.

Keywords: immune reconstitution, immune enhancement, immunotherapy, vaccine, cancer vaccine

INTRODUCTION

Interleukin-7 (IL-7) has a wide range of biological activities including a critical role in T cell development, as well as roles in hematopoiesis and in post developmental immune functions (1-4). Unlike in the mouse, IL-7 is not required for human B cell development. IL-7 plays a critical and non-redundant role in maintaining peripheral T cell homeostasis and is considered a prototypic homeostatic cytokine. It is required to maintain naïve CD4+ and CD8+ cells in vivo (5-7) and IL-7 levels are inversely correlated to the T cell depletion status (7,8).

A multitude of murine and simian pre-clinical models have demonstrated IL-7's wide array of immune enhancing properties that may find clinical applications. RhIL-7 improves immune reconstitution in non human primate models. In SIV infected monkeys, it increases the number of circulating naïve and memory CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (9,10). IL-7 enhances immune reconstitution, improving CD4+ reconstitution following autologous CD34+ selected stem cell transplantation in monkeys (11) as well as in mice (12-18). It also enhances anti infectious cytotoxicity in several animal models following adoptive transfer of specific T cells (19) or bone marrow transplant (20).

IL-7 enhances anti-tumor immune responses in mice (13,21,22). It is critical in the proliferation and in vivo persistence of tumor specific T-cells (23) and enhances anti-tumor responses and survival (24). IL-7 administration post-transplant results both in improved T-cell recovery and in prolonged tumor free survival (12). Immune enhancement after severe immune depletion such as following stem cell transplantation may have clinical value since early lymphocyte reconstitution correlates with clinical outcome following autologous transplantation (25-28). Furthermore, standard or high-dose radio-chemotherapy often only induces temporary complete or partial disease responses but no cure, leaving candidates for novel immunotherapy strategies immunologically depleted which may hinder the effectiveness of such strategies.

RhIL-7's potential therapeutic uses are centered on its immuno-modulatory effects on T-cells and could include generating or optimizing T-cell responses to novel anti-tumor or anti-infectious immune interventions in a variety of clinical circumstances with severe immune depletion, be they physiologic (e.g. aging), pathologic (e.g. HIV) or iatrogenic (immune depleting therapies). We conducted a phase I study of the administration of rhIL-7 in order to determine, dose limiting toxicity (DLT), maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and a range of biologically active doses in humans.

METHODS

Eligibility

Adults diagnosed with incurable non-hematologic malignancy with a life expectancy greater than three months were eligible. A peripheral CD3+ cells count above 300 cells per mm3 was required. Also required were: normal left ventricular ejection fraction, DLCO / VA and FEV1 > 50%, AST and ALT less than three times the upper limit of normal, Absolute Neutrophil Count > 1000 / mm3, platelet count >100,000/mm3, PT/PTT within 1.5 times the upper limit of normal, creatinine clearance of > 60 ml/min and Karnofsky Performance Status > 70%. Exclusions were recent use or need for anticoagulation, systemic corticosteroids, cytotoxic or immuno-suppressive therapy; splenectomy, splenomegaly, prior solid organ or allogeneic stem cell transplantation; infections with HIV, hepatitis B or C; history of autoimmune disease, severe uncontrolled asthma. Toxicity was evaluated according to the NCI “Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events”. The study was approved by the NCI Institution Review Board and the Food & Drug Administration. Subjects signed written informed consent before enrollment.

Trial design

“CYT 99 007” (E. Coli recombinant human interleukin-7: rhIL-7; Cytheris, Inc., Rockville, MD) was given subcutaneously, every other day for 2 weeks in successive cohorts of 3-6 patients in a standard phase I design (dose levels: 3, 10, 30 and 60 μg / Kg per dose). All subjects except the first on study received the same product lot. The primary study objectives were safety, DLT and MTD determination. Secondary objectives included defining a range of biologically active doses, defining rhIL-7 pharmacokinetics and evaluating possible anti-tumor effects. Biologic activity was defined as 50% increase over baseline in number of peripheral blood (PB) CD3+ cells /mm3.

Subjects underwent body CT scan at baseline, end of therapy (day 14) and day 28. Subjects with stable disease at day 28 were followed if possible until disease progression. Bone marrow (BM) aspirate and biopsy were performed at baseline and day 14.

Flow Cytometry

Peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) analysis

We analyzed fresh, EDTA anti-coagulated, PB at the specified time points as previously described (29).

Bone Marrow flow cytometry

BM aspirates were collected into sterile sodium heparin, pre-lysed with ammonium chloride and stained for 30 minutes at room temperature with antibodies directed against: CD13, CD33, and CD36 (Beckman-Coulter, Miami, FL); CD3, CD10, CD14, CD16, CD19, CD22, CD34, CD56, CD45 and CD71 (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA); CD64 (Caltag Laboratories, Burlingame, CA); CD20, Kappa, Lambda (Dako-Cytomation, Carpinteria, CA). Cells were fixed in 1.0% paraformaldehyde and stored at 4°C for up to 12 hours before acquisition. Four color cytometry was performed with a BD (Becton-Dickinson, San Jose, CA) FACSCalibur. Data were analyzed with CellQuest software (BD). Granulocytes, monocytes, mature lymphocytes, nucleated red blood cells and immature hematopoietic precursors were determined based upon levels of CD45 expression, side scatter and pattern of antigen expression.

Immunoglobulin gene rearrangement

DNA was extracted from Ficoll-Hypaque separated BMMC and PCR amplified for detection of immunoglobulin heavy chain gene rearrangements, using primers to framework region III and the joining region of the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene (FRIII-IGH PCR). Additional PCR was performed in duplicate, using consensus primers to framework region II and the immunoglobulin heavy chain joining region (FRII-IGH PCR) according to the method of Ramasamy (30).

Serum anti-IL-7 antibody determination

Antibody detection used a two-step Elisa and a bioassay for neutralization of IL-7 bioactivity, both developed for and used during rhIL-7 pre-clinical development by Cytheris. Pre-treatment and day 28 serum samples were assayed. Assays were repeated at day 35 and 42 if equivocal at day 28. Titer ≥ 1/200 was considered positive for the Elisa, but a neutralization bioassay was performed for any titer ≥ 1/100. A neutralizing antibody titer ≥ 1/400 at either day 28 or 42 was to be considered positive and a DLT.

Serum rhIL-7 level determination and pharmacokinetics

Serum IL-7 levels were determined serially for pharmacokinetics following the first and last doses. The Diaclone Research (Cell Systems) Sandwich IL-7 ELISA kit was used for validation and sample analysis. The two-site sandwich ELISA used anti-rhIL-7 monoclonal antibodies, one as coating antibody for capture, the other, biotinylated, for detection. The linear relationship between rhIL-7 concentrations and O.D extended up to 200 pg /ml; concentrations < 12.5 pg/ml were treated as zero for pharmacokinetic calculations (Kinetica Software, version 4.2) with the non compartmental extravascular model. The AUCs were computed using the Log Linear Method, trapezoidal when Cn > Cn-1. Half-lives were calculated between t = 2 hrs (Tmax) and T = 24 hrs.

Statistics

Using the data presented in table 2, differences between pre and post treatment values and the relative difference (post-pre)/pre were formed for the four markers of interest of mature B cells (CD19+/CD45bright, CD19+/CD10−) and immature B cells (CD19+/CD45dim, CD19+/CD10+). In the one case in which the value was noted to be <1.0, this was changed to be 0.5 for simplicity. It was determined that the association between either the absolute or relative difference was approximately equally well associated with the pre-treatment value; thus, for simplicity, the absolute difference was evaluated to determine if the change was equal to zero. A Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to determine if the change was equal to zero, after determining that the differences were not normally distributed. All p-values are two-sided and presented without formal adjustment for multiple comparisons.

Table 2. Summary of Bone Marrow Flow Cytometry Data. Lymphoid bone marrow expansion with rhIL-7 therapy.

Percentage of BMMC for the marker combinations: mature B cells: CD19+/CD45bright and CD19+/CD10−; immature B cells: CD19+/CD45dim and CD19+/CD10+. UPN: unique patient number. p value given (Wilcoxon signed rank test) on the absolute difference between “pre” and “post” values for each marker combination

| Mature B cells | Immature B cells | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UPN (age) |

CD19+/ CD45bright | CD19+/ CD10− | CD19+/ CD45dim | CD19+/ CD10+ | ||||

| Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | Pre | Post | |

| 01 (70) | 0.4 | 1 | 0.4 | 0 | 0.2 | 8 | 0.2 | 0 |

| 02 (48) | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0.4 | 10 | 1 | 11 |

| 03 (67) | 5 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 1 | <1 | 2 | 1 |

| 04 (56) | 6.9 | 2 | 5.5 | 1 | 7 | 59 | 10 | 55 |

| 05 (71) | 3.5 | 27 | 2 | 1.9 | 11 | 23 | 12 | 47 |

| 06 (28) | 4.2 | 2 | 4.3 | 15 | 1.2 | 18 | 0.8 | 5 |

| 08 (20) | 26 | 35 | 17 | 6 | 17 | 51 | 22 | 80 |

| 09 (28) | 11 | 4 | 9.4 | 4 | 12 | 8 | 13 | 8 |

| 10 (48) | 7.3 | 23 | 6.6 | 4 | 6.5 | 21 | 7 | 39 |

| 11 (61) | 10 | 2 | 10 | 2 | 6 | 6 | 4 | 10 |

| 12 (62) | 10 | 0.8 | 7 | 1 | 2 | 7 | 2 | 6 |

| 13 (19) | 6.9 | 1.5 | 6.3 | 0.7 | 4.6 | 33 | 4.6 | 30 |

| 15 (43) | 14.8 | 1 | 10.7 | 1 | 19.2 | 80 | 11.9 | 80 |

| 16 (66) | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 11 | 3 | 9 |

| Mean | 8.07 | 7.59 | 6.30 | 3.19 | 6.51 | 23.96 | 6.68 | 27.21 |

| Median | 6.90 | 2.0 | 5.90 | 1.95 | 5.30 | 14.50 | 4.30 | 10.50 |

| Post-Pre | −0.48 | −3.11 | 17.46 | 20.54 | ||||

| p value | 0.38 | 0.024 | 0.0012 | 0.0029 | ||||

RESULTS

Twelve men, 4 women, age 19 to 71 years (median: 49), with incurable malignancies were treated. Table 1 summarizes subject characteristics, toxicity and immunogenicity data.

Table 1.

Summary of subject characteristics, toxicity and immunogenicity

| UPN | Cohort# / (μg/Kg/dose) |

Age | Diagnosis | Toxicity (possibly, probably or definitely related) Maximum toxicity grade & Type (grade) |

Anti-IL7 Antibody titer |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding | Neutralizing | |||||||

| 01 | 1 / (3) | 70 | Renal Cell Carcinoma* | 1 | IS (1); EO (1) | Pos | (1/1600) | 0 |

| 02 | 48 | Hemangiopericytoma | 2 | ALT (2) | Neg | (0) | na | |

| 03 | 67 | Melanoma | Neg | (0) | na | |||

| 04 | 2 / (10) | 56 | Melanoma | 2 | IS (2); CS (1) | Neg | (1/100) | 0 |

| 05 | 71 | Renal Cell Carcinoma | 2 | IS (2); CS (1); ALT (1) | Neg | (0) | na | |

| 06 | 28 | Carcinoma of unknown primary | 2 | IS (2); CS (2) | Neg | (0) | na | |

| 07 | 3 / (30) | 21 | Osteogenic Sarcoma** | 3 | AST, bili (3); CS (1) | na | na | |

| 08 | 20 | Rhabdomyosarcoma | 1 | IS (1); CS (1) | Pos | (1/400) | 0 | |

| 09 | 28 | Synovial Cell Sarcoma | 1 | IS (1); CS (1); SM (1) | Neg | (1/100) | 0 | |

| 10 | 48 | Duodenal Carcinoma | 2 | IS (2); CS (1) | Neg | (1/100) | 0 | |

| 11 | 61 | Colon carcinoma | Pos | (1/1200) | 0 | |||

| 12 | 62 | Melanoma | 2 | IS (2); CS, SOB (2); ALT, bili (1) | Pos | (1/400) | 0 | |

| 13 | 4 / (60) | 19 | Melanoma | 2 | IS (2); CS, bili (2); ALT, AP, Plt (1) | Pos | (1/1200) | 0 |

| 14 | 35 | Pheochromocytoma*** | 3 | Cardiac ++ (3); AST, ALT(1) | Neg | (1/100) | na | |

| 15 | 43 | Ovarian carcinoma | 3 | ALT(3); AST, IS(2); CS, AP (1) | Pos | (1/1200) | 0 | |

| 16 | 66 | Melanoma | 1 | IS, CS, bili (1) | Neg | (0) | na | |

Received initial lot of “CYT 99 007”

Received only 1 dose

Received only 3 doses

See text

ALT, AST: transaminases. AP: alkaline phosphatase. Bili: total bilirubin. CS: constitutional symptoms. EO: eosinophilia. IS: injection site; erythema, induration, pruritus. Plt: decreased platelets. SM: splenomegaly. SOB: shortness of breath

Toxicity

“CYT 99 007” was well tolerated. Following most injections, subjects receiving 10μg /Kg or more developed grade 1-2 constitutional symptoms, 6 to 8 hours following administration and mild local reactions with erythema, pruritus and induration. Two subjects did not complete therapy because of toxicity. One developed rapidly reversible grade 3 liver enzyme and bilirubin elevation following the first dose at the 30 μg/Kg and treatment was terminated. The other developed grade 3 chest pain, hypertension with mild Troponin elevation several hours after the 3rd dose of 60 μg/Kg; treatment was stopped and all abnormalities abated within 2 days (see discussion). Subsequently, no significant ECG changes were seen when systematically performed at 3 and 24 hours following every injection on all remaining subjects. No symptoms or signs of autoimmunity were seen.

Biologic activity

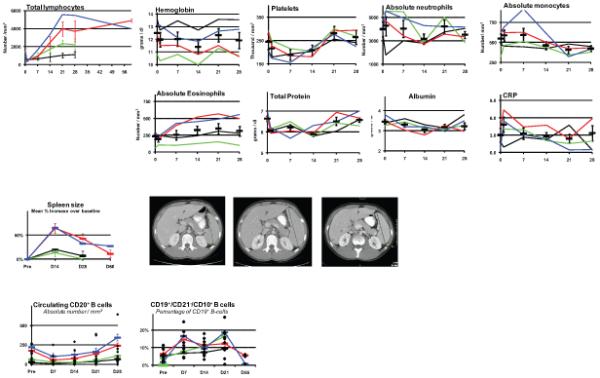

Starting at10 μg/Kg/dose, all subjects showed evidence of biologic activity (a trend toward activity was seen at 3 μg/Kg/dose). A 50-60% drop in absolute lymphocyte counts (ALC) following the first dose was seen in all subjects on day 1, as in most preclinical models. All patients showed a dose-dependent marked increase in ALC which persisted for several weeks after treatment (Fig 1a). Although several hematological parameters, serum albumin, total protein and C-Reactive Protein showed mild fluctuations during the study, none except for ALC appeared clinically significant; transient platelet decrease during treatment; monocyte decrease after treatment and eosinophils peaking on day 21, all (except the C-Reactive Protein values) remaining within the normal institutional range. Lymphoid organ enlargement (spleen and lymph nodes, but not thymus) was seen in a dose dependent manner on CT scan, maximum on day 14, returning to baseline over several weeks (Fig 1b).

Figure 1. Clinical parameter kinetics with rhIL-7 therapy.

Cohorts: 1, black; 2, green: 3, red: 4, blue

a)Top left: ALC cohort mean ± SEM. Others: mean + SEM for all subjects.

b) Left: mean spleen size; spleen on CT: baseline, day 14, 2 months.

c) Left: mean absolute numbers mature B cells; right: immature B cells, mean percentage of CD19+ population.

T cell populations

For all T cell populations, the absolute cell numbers peaked on day 21 and remained elevated for weeks while lymphopenia following treatment was never observed. In most subjects, CD3+ αβ and γδ T cells increased equally and the increase was similar in CD4+ and CD8+ cells as well as CD3+ (but not CD3−) CD16+ or CD56+ cells. An in-depth analysis of T cell subset kinetics and their consequences on the circulating T cell make up and T cell repertoire diversity following rhIL-7 therapy has been reported (29) and is summarized in the discussion. Briefly, up to 60% of circulating CD3+ cells were in cycle (Ki67+) on day 7 of treatment. In spite of treatment continuation, the fraction of circulating cells in cycle had decreased by the end of treatment and returned to baseline one week after the end of treatment. Both IL-7Rα surface expression and mRNA were decreased during the treatment and returned to baseline after the end of treatment. Interestingly, the subject who received only the first 3 doses of rhIL-7 demonstrated the same cell cycling and IL-7Rα down-regulation patterns (29) at day 7 and had a day 28 increase in ALC similar to that of the other subjects, suggesting that maximum therapeutic effects may be reached early, possibly because of IL-7Rα down-regulation (see discussion).

IL-2Rα (CD25) surface expression was studied in a selected group of patients receiving the higher doses of rhIL-7. There was evidence of increased CD25 surface expression in the CD4+ non Tregs and CD8+ T cells populations. The mean percent increase over baseline of CD25 + cells were 55% (95% CI: 40, 70) at Day 7 and 57% (95% CI: 45, 69) at day 14 for CD4+ cells and 74% (95% CI: 63, 85) at Day 7 and 85% (95% CI: 72, 98) at day 14 for CD8+ cells with return to baseline at day 21.

Circulating B cells

Mature B cells (CD20+) consistently showed a modest and not demonstrably dose-dependent decrease in absolute number during therapy and returned to baseline by day 28 (Fig 1c). Several subjects showed a mild expansion of circulating CD19+ / CD10+ B cells, [immature / transitional B-cell (31,32)], peaking on day 21 (Fig 1c) with no correlation between cell number and subjects age or magnitude of their BM pre B cell proliferation (see below). There was no increase in circulating activated germinal center B cells (CD19+/CD27+/CD10+).

Bone Marrow

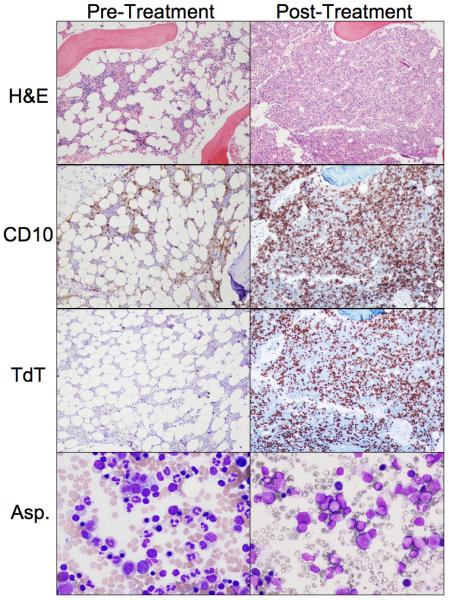

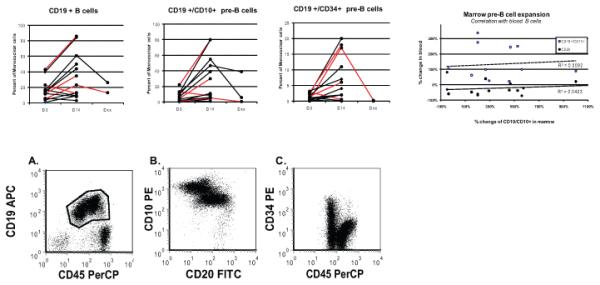

All subjects underwent BM aspiration and biopsy evaluation before and at the end of therapy, by detailed analysis of H&E, immunostains and flow cytometry. Although 17 different markers or marker combinations spanning the spectrum of bone marrow lineages and of differentiation stages were analyzed by flow cytometry, most showed variations between the pretreatment and post treatment samples that remained within the normally occurring wide normal range. In general, rhIL-7 treatment resulted, by day 14, in an increased cellularity, usually within normal limits. There were no significant abnormalities in morphology or abundance of the myeloid, erythroid or megakaryocytic lineages. The proportion of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells remained largely unchanged and most subjects showed a statistically significant increase in CD19+/CD10+ and /or CD19+/CD45dim early pre B cells (Table 2). In 6 subjects, however, the CD10 and Tdt abnormalities on biopsy immunostains would have triggered further flow cytometry investigation in other clinical settings (Fig 2) and, in these cases, post treatment early pre B cells represented 30 to 86% of all BMMC by flow cytometry, showing no commensurate increase in mature B cells (Table 2) and no correlation with treatment dose or subjects' age (Fig 3a). As shown in Figure 3b, the CD19+ B cells immunostaining in the flow cytometry analysis was consistent with ongoing maturation: increasing levels of CD45 and CD19 expression (polygonal gate in panel A); in gated CD19+ B cell: increasing CD20 with decreasing CD10 expression (panel B) and increasing CD45 with decreasing CD34 expression (panel C). PCR studies of both BM and PBMC for immunoglobulin gene rearrangement failed to reveal any clonal population (data not shown). Follow up BM or PB studies performed several weeks after the end of treatment in subjects with the highest pre-B cell increases, consistently showed either declining or resolved pre-B cell marrow proliferation by flow cytometry, confirmed to have remained polyclonal by PCR.

Figure 2.

H&E, immunostaining (CD10, Tdt) (200X) and giemsa stain (400X), pre and post rhIL-7 therapy, in subject with marked marrow expansion (UPN08)

Figure 3. Bone Marrow B cell.

a) CD19+ cells and subsets: % total BMMC. (subjects < 30 years in red). Dxx; 4-10 weeks; correlation between BM CD19+/CD10+ pre-B cells and PB increases in: CD20+ (●); CD19+/D10+ (○).

b) Flow cytometry scatterplots of marrow early B cell precursors in subject with marked expansion (UPN08) illustrating progressive maturation Panel A. Bone marrow cells- ungated data, x-axis CD45 PerCP, y-axis CD19 APC, CD19 positive B cells (in polygonal analysis gate) have increasing levels of CD45 and CD19 expression consistent with ongoing maturation. Panel B. CD19 positive B cells (gate-polygonal gate in A), x-axis CD20 FITC, y-axis CD10 PE, CD19 positive B cells have increasing levels of CD20 expression and decreasing levels of CD10 expression consistent with ongoing maturation. Panel C. CD19 positive B cells (gate-polygonal gate in A), x-axis CD45 PerCP, y-axis CD34 PE, CD19 positive B cells have increasing levels of CD45 expression and decreasing levels of CD34 expression consistent with ongoing maturation.

Immunogenicity

Sera were tested for anti-IL-7 antibodies on day 28 and, if required, day 42 (Table 1). The only subject treated with the first lot of rhIL-7 (01) developed a 1/1600 antibody titer. Excluding this subject who received a different formulation, 5 of the 14 subjects evaluable for immunogenicity developed anti-IL-7 antibodies. None of the 5 receiving 3 or 10 μg/Kg and 5 of 9 receiving 30 or 60 μg/Kg developed antibodies on day 28, suggesting a dose response. No subject developed anti-IL-7 neutralizing antibodies. None of the subjects with longer follow up developed late lymphopenia.

Anti-tumor activity

Although the study was not designed to evaluate anti-tumor activity, disease follow up was carried out as feasible. Subject 02 with CNS hemangiopericytoma and abdominal metastases (no CNS disease at entry on study) had a substantial improvement of abdominal pain and a 20% reduction in mass size at 3 months. The abdominal disease remained stable at the time of a CNS recurrence, 9 months following rhIL-7 therapy. All other patients had progressive disease by day 42.

Pharmacokinetics

Pharmacokinetics studies (performed after the first and the last rhIL-7 doses) are provided in Table 3. The rhIL-7 half life ranged from 6.5 to 9.8 hours. While the Cmax increased from the 10 to 30μg/kg dose, the day 1 total AUC increased throughout the dose range and clearance decreased while apparent half life increased with the dose. High affinity clearance mechanisms, mediated by IL-7R, probably explain a better clearance at low dose. The consistently higher clearance and lower AUC at day 14 compared to day 1 at a given dose probably reflect the larger lymphoid mass at day 14. RhIL-7 pharmacodynamics seem to correlate better with AUC and half life than with Cmax, consistent with the characteristic pharmacodynamic / pharmacokinetic profile of growth factors and cytokines: prolonged AUCs and half lives tend to improve efficacy by sustaining blood levels above activity threshold over a prolong period while peak concentrations well above activity threshold (high Cmax) contribute less to the biologic effects.

Table 3. rhIL-7 pharmacokinetics.

Upper panel: mean serum concentrations for cohorts Lower panel: Pharmacokinetics parameters (mean values for a cohort). Results are shown after the first dose (d1) and after the last dose (d14) for each cohort.

| Dose | 10μg/Kg | 30μg/Kg | 60μg/Kg | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rhIL-7 serum levels (pg/ml) | ||||||

| Time (hrs) | d 1 | d 14 | d1 | d 14 | d 1 | d 14 |

| 0 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 0 |

| .5 | 51 | 35 | 506 | 372 | 534 | 929 |

| 1 | 93 | 48 | 837 | 399 | 908 | 1019 |

| 1.5 | 121 | 57 | 1335 | 616 | 1279 | 1324 |

| 2 | 148 | 66 | 1895 | 688 | 1246 | 1354 |

| 2.5 | 147 | 69 | 1766 | 426 | 1223 | 1344 |

| 4 | 354 | 83 | 1531 | 717 | 1176 | 1211 |

| 8 | 120 | 53 | 917 | 459 | 821 | 177 |

| 12 | 87 | 58 | 936 | 438 | 832 | 161 |

| 24 | 28 | 6 | 296 | 122 | 478 | 139 |

| Pharmacokinetics parameters | ||||||

|

Mean total daily dose (μg) |

686 | 686 | 2322 | 2322 | 4763 | 5280 |

| Cmax (pg/ml) | 354 | 83 | 1895 | 717 | 1846 | 1697 |

| Tmax (h) | 4.0 | 4.0 | 2.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.0 |

|

AUC total (pg/ml*min) |

168357 | 69697 | 1416470 | 591776 | 1812870 | 1483180 |

| t ½ (h) | 8.54 | 9.80 | 9.03 | 6.46 | 8.92 | 7.23 |

|

Clearance (ml/min) |

4077 | 9847 | 1639 | 3890 | 2627 | 3560 |

DISCUSSION

We present here clinical findings of a phase I study of rhIL-7, defining a toxicity profile and a range of biologically active doses. Enrollment was limited to individuals with a stable CD3+ peripheral count >300 cells/mm3. Studies in other populations (HIV, allogeneic transplant recipients) are under way. Although the first dose level was designed as a No Effect Dose based on non-human primate studies (9), early signs of biological activity were apparent at this dose, suggesting a 10-30 fold greater sensitivity in humans.

RhIL-7 was well tolerated with no MTD being reached in the treated subjects. The observation of only mild adverse reactions along with the biological activity in the tested dose range suggests a safe therapeutic window. One subject had liver DLT, concomitant with the onset of a catheter infection. The cardiac DLT occurred in the subject with pheochromocytoma, with typical symptoms for this disease (causing the DLT) occurring concurrently with the expected constitutional symptoms. These two potentially rhIL-7 related toxicities will require further scrutiny in subsequent trials. At the two highest doses, spleen and lymph node enlargements were noticeable but not clinically worrisome although caution during the period of rapid spleen enlargement remains warranted. RhIL-7 immunogenicity was not limiting and no neutralizing antibodies or lymphopenia developed. A glycosylated rhIL-7 is presently under clinical development which may prove less immunogenic and allow the evaluation of repeated courses of treatment. There was no suggestion of the development of autoimmunity.

In a limited number of subjects, there was a marked, self-limited expansion of polyclonal bone marrow pre-B cells (hematogones), consistent with in vitro observations that human pro-B cells display a functional IL-7R and expand following IL-7 exposure but subsequently die without reaching mature B cell stage (33-35). Several subjects showed a mild expansion of circulating CD19+ / CD10+ transitional B cells, a population found in HIV patients to correlate with serum IL-7 levels (31). There was no obvious correlation between BM and PB expansions of immature B cells and the number of circulating mature B cells was largely unaffected by rhIL-7 treatment. IL-7 effects on B cell development and physiology accumulated in the murine system is mostly irrelevant to humans and the knowledge that rhIL-7 may induce a self-limited, but often marked, polyclonal pre-B cell expansion in humans is valuable safety information for the future rhIL-7 clinical trials.

RhIL-7 induced a dose dependent, but age independent, increase in circulating CD3+ (both αβ and γδ) lymphocytes, CD3+ (but not CD3−) CD16+ or CD56+ cells and CD3+/CD4− /CD8− T cells (29). This net increase in circulating lymphocytes was most likely due to proliferation / expansion taking place in the PB and / or lymphoid organs with varying contribution by alteration in cell trafficking. The massive increase in the number of cycling circulating lymphocytes is unlikely due solely to trafficking out of lymphoid organs considering the concomitant spleen and lymph nodes enlargement as well as the continuing increase in circulating lymphocyte numbers after therapy. Other evidence supported T cell expansion as resulting from a combination of increased cell cycling and decreased apoptosis (29). The sharp decrease in cell cycling while pharmacologic serum IL-7 levels were sustained during the second week of treatment suggests that down-regulation of IL-7Rα plays a role in the self limited effects of rIL-7, a consideration for the design of future trials.

Detailed studies of T cell subsets, reported elsewhere (29), showed that rhIL-7 preferentially expanded the CD4 + naïve and central memory T-cells as well as CD8+ naïve T cells resulting in a statistically significant broadening of T cell repertoire diversity in both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. Therefore, within 3 weeks of treatment initiation, rhIL-7 resulted in a marked expansion of T cells which remained functional (with conserved or increased in vitro responsiveness to anti-CD3 stimulation) and which exhibited a rejuvenated profile resembling that seen early in life (29). Additionally, CD4+/FoxP3+ regulatory T cells showed markedly less proliferation, consistent with their low IL-7R α-chain expression (36,37), expanded less than other CD4+ T cells resulting in a decreased proportion of circulating regulatory T cells (29,38).

In summary, rhIL-7 is well tolerated in humans, has significant biologic activity over dose range indicating a potential safe therapeutic window. It induces an age independent marked expansion of the T cell mass resulting in a rejuvenated T cell profile with an increased T cell repertoire diversity and a decreased proportion of regulatory T cells. This study paves the way for the systematic investigation of specific clinical applications for enhancement of immune responses or immune reconstitution in a multitude of clinical circumstances of immune depletion, be they iatrogenic (chemotherapy / radiation / transplantation), pathologic (HIV) or physiologic (immuno-senescence), and may be considered to optimize strategies of passive or active immunotherapy.

STATEMENT OF TRANSLATIONAL RELEVANCE.

IL-7 has critical and non redundant roles in T-cell development, hematopoiesis and post developmental immune functions. Based on a large body of pre-clinical evidence, it is a prototypic homeostatic cytokine that may have multiple therapeutic applications in a wide array of immunodeficiency states, either physiologic (i.e. immuno-senescence), pathologic (e.g. HIV) or iatrogenic (e.g. post-chemotherapy and post-hematopoietic stem cell transplant) and, in particular, may have roles in immune reconstitution or enhancement of immunotherapy in multimodality cancer therapy strategies.

Indeed, IL-7 has been ranked #5 on NCI's list of “Top 20 Agents with High Potential for Use in Treating Cancer” at the July,12 2007 NCI Immunotherapy Agent Workshopa.

This paper demonstrates that rhIL-7 has potent biological activity over a dose range that is well tolerated in humans, and therefore will allow further exploration of its possible therapeutic applications.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research and was made possible through a formal collaboration (Cooperative Research And Development Agreement “CRADA” # 01649) between the National Cancer Institute and Cytheris Inc, Rockville, MD, the IND holder and manufacturer of rhIL-7, currently developing recombinant human IL-7 for therapeutic use. As per the CRADA between NCI and Cytheris Inc., the NCI investigators designed and conducted all the research experiments and analyses presented in the manuscript independently from Cytheris Inc.

The authors would like to thank the subjects who enrolled on this investigational trial and provided consent for research studies and the clinical staff of the NIH Clinical Center and of the Experimental Transplantation & Immunology Branch for their excellent care of these subjects.

This work was performed at the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of health, Department of Health and Human Services in collaboration with Cytheris Inc. (Rockville, MD) under a Cooperative Research and Development Agreement (CRADA # 01649)

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest statement

Three co-authors (JE, RB and MM) had financial interest in Cytheris capital: MM is the founder and CEO and JE and RB were employees of Cytheris. All other co-authors have explicitly denied any conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Komschlies KL, Grzegorzewski KJ, Wiltrout RH. Diverse immunological and hematological effects of interleukin 7: implications for clinical application. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;58:623–633. doi: 10.1002/jlb.58.6.623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hofmeister R, Khaled AR, Benbernou N, et al. Interleukin-7: physiological roles and mechanisms of action. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 1999;10:41–60. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(98)00025-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Appasamy PM. Biological and clinical implications of interleukin-7 and lymphopoiesis. Cytokines Cell Mol Ther. 1999;5:25–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fry TJ, Mackall CL. Interleukin-7: from bench to clinic. Blood. 2002;99:3892–3904. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.11.3892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schluns KS, Kieper WC, Jameson SC, Lefrancois L. Interleukin-7 mediates the homeostasis of naive and memory CD8 T cells in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:426–432. doi: 10.1038/80868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fry TJ, Connick E, Falloon J, et al. A potential role for interleukin-7 in T-cell homeostasis. Blood. 2001;97:2983–2990. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.10.2983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Napolitano LA, Grant RM, Deeks SG, et al. Increased production of IL-7 accompanies HIV-1-mediated T-cell depletion: implications for T-cell homeostasis. Nat Med. 2001;7:73–79. doi: 10.1038/83381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bolotin E, Annett G, Parkman R, Weinberg K. Serum levels of IL-7 in bone marrow transplant recipients: relationship to clinical characteristics and lymphocyte count. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1999;23:783–788. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1701655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fry TJ, Moniuszko M, Creekmore S, et al. IL-7 therapy dramatically alters peripheral T-cell homeostasis in normal and SIV-infected nonhuman primates. Blood. 2003;101:2294–2299. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-07-2297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beq S, Nugeyre MT, Ho Tsong FR, et al. IL-7 induces immunological improvement in SIV-infected rhesus macaques under antiviral therapy. J Immunol. 2006;176:914–922. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.2.914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Storek J, Gillespy T, III, Lu H, et al. Interleukin-7 improves CD4 T-cell reconstitution after autologous CD34 cell transplantation in monkeys. Blood. 2003;101:4209–4218. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Talmadge JE, Jackson JD, Kelsey L, et al. T-cell reconstitution by molecular, phenotypic, and functional analysis in the thymus, bone marrow, spleen, and blood following split-dose polychemotherapy and therapeutic activity for metastatic breast cancer in mice. J Immunother. 1993;14:258–268. doi: 10.1097/00002371-199311000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Komschlies KL, Gregorio TA, Gruys ME, et al. Administration of recombinant human IL-7 to mice alters the composition of B-lineage cells and T cell subsets, enhances T cell function, and induces regression of established metastases. J Immunol. 1994;152:5776–5784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bolotin E, Smogorzewska M, Smith S, Widmer M, Weinberg K. Enhancement of thymopoiesis after bone marrow transplant by in vivo interleukin-7. Blood. 1996;88:1887–1894. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mackall CL, Fry TJ, Bare C, et al. IL-7 increases both thymic-dependent and thymic-independent T-cell regeneration after bone marrow transplantation. Blood. 2001;97:1491–1497. doi: 10.1182/blood.v97.5.1491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alpdogan O, Schmaltz C, Muriglan SJ, et al. Administration of interleukin-7 after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation improves immune reconstitution without aggravating graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2001;98:2256–2265. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.7.2256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Broers AE, Posthumus-van Sluijs SJ, Spits H, et al. Interleukin-7 improves T-cell recovery after experimental T-cell-depleted bone marrow transplantation in T-cell-deficient mice by strong expansion of recent thymic emigrants. Blood. 2003;102:1534–1540. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-11-3349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alpdogan O, Muriglan SJ, Eng JM, et al. IL-7 enhances peripheral T cell reconstitution after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1095–1107. doi: 10.1172/JCI17865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wiryana P, Bui T, Faltynek CR, Ho RJ. Augmentation of cell-mediated immunotherapy against herpes simplex virus by interleukins: comparison of in vivo effects of IL-2 and IL-7 on adoptively transferred T cells. Vaccine. 1997;15:561–563. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(96)00212-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdul-Hai A, Ben Yehuda A, Weiss L, et al. Interleukin-7-enhanced cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity after viral infection in marrow transplanted mice. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 1997;19:539–543. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1700706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Komschlies KL, Back TT, Gregorio TA, et al. Effects of rhIL-7 on leukocyte subsets in mice: implications for antitumor activity. Immunol Ser. 1994;61:95–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy WJ, Longo DL. The potential role of NK cells in the separation of graft-versus-tumor effects from graft-versus-host disease after allogeneic bone marrow transplantation. Immunol Rev. 1997;157:167–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065x.1997.tb00981.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang LX, Li R, Yang G, et al. Interleukin-7-dependent expansion and persistence of melanoma-specific T cells in lymphodepleted mice lead to tumor regression and editing. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10569–10577. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li B, Vanroey MJ, Jooss K. Recombinant IL-7 enhances the potency of GM-CSF-secreting tumor cell immunotherapy. Clin Immunol. 2007;123:155–165. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Porrata LF, Gertz MA, Inwards DJ, et al. Early lymphocyte recovery predicts superior survival after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation in multiple myeloma or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood. 2001;98:579–585. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.3.579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Porrata LF, Litzow MR, Tefferi A, et al. Early lymphocyte recovery is a predictive factor for prolonged survival after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for acute myelogenous leukemia. Leukemia. 2002;16:1311–1318. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2402503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Porrata LF, Inwards DJ, Micallef IN, et al. Early lymphocyte recovery post-autologous haematopoietic stem cell transplantation is associated with better survival in Hodgkin's disease. Br. J Haematol. 2002;117:629–633. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2002.03478.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Porrata LF, Ingle JN, Litzow MR, Geyer S, Markovic SN. Prolonged survival associated with early lymphocyte recovery after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for patients with metastatic breast cancer. Bone Marrow Transplantation. 2001;28:865–871. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sportes C, Hakim FT, Memon SA, et al. Administration of rhIL-7 in humans increases in vivo TCR repertoire diversity by preferential expansion of naive T cell subsets. J Exp Med. 2008;205:1701–1714. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ramasamy I, Brisco M, Morley A. Improved PCR method for detecting monoclonal immunoglobulin heavy chain rearrangement in B cell neoplasms. J Clin Pathol. 1992;45:770–775. doi: 10.1136/jcp.45.9.770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Malaspina A, Moir S, Ho J, et al. Appearance of immature/transitional B cells in HIV-infected individuals with advanced disease: Correlation with increased IL-7. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:2262–2267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511094103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sims GP, Ettinger R, Shirota Y, et al. Identification and characterization of circulating human transitional B cells. Blood. 2005;105:4390–4398. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-11-4284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dittel BN, LeBien TW. The growth response to IL-7 during normal human B cell ontogeny is restricted to B-lineage cells expressing CD34. J Immunol. 1995;154:58–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.LeBien TW. Fates of human B-cell precursors. Blood. 2000;96:9–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Johnson SE, Shah N, Panoskaltsis-Mortari A, LeBien TW. Murine and human IL-7 activate STAT5 and induce proliferation of normal human pro-B cells. J Immunol. 2005;175:7325–7331. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.11.7325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Liu W, Putnam AL, Xu-Yu Z, et al. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1701–1711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seddiki N, Santner-Nanan B, Martinson J, et al. Expression of interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-7 receptors discriminates between human regulatory and activated T cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1693–1700. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosenberg SA, Sportes C, Ahmadzadeh M, et al. IL-7 administration to humans leads to expansion of CD8+ and CD4+ cells but a relative decrease of CD4+ T-regulatory cells. J Immunother. 2006;29:313–319. doi: 10.1097/01.cji.0000210386.55951.c2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]