Abstract

The assay described here represents an improved yeast bioassay that provides a rapid yet sensitive screening method for EDCs with very little hands-on time and without the need for sample preparation. Traditional receptor-mediated reporter assays in yeast were performed twelve to twenty four hours after ligand addition, used colorimetric substrates, and, in many cases, required high, non-physiological concentrations of ligand. With the advent of new chemiluminescent substrates a ligand-induced signal can be detected within thirty minutes using high picomolar to low nanomolar concentrations of estrogen. As a result of the sensitivity (EC50 for estradiol is ~ 0.7 nM) and the very short assay time (2-4 hours) environmental water samples can typically be assayed directly without sterilization, extraction, and concentration. Thus, these assays represent rapid and sensitive approaches for determining the presence of contaminants in environmental samples. As proof of principle, we directly assayed wastewater influent and effluent taken from a wastewater treatment plant in the El Paso, TX area for the presence of estrogenic activity. The data obtained in the four-hour yeast bioassay directly correlated with GC-mass spectrometry analysis of these same water samples.

Keywords: effluent, environmental estrogens, estrogenic activity, wastewater, yeast bioassay, yeast estrogen screen

1. Introduction

Endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) which mimic the activity of estrogen within the human system are widely distributed within the environment and have gained notoriety due to association with certain cancers, reproductive disorders, developmental abnormalities, and other adverse physiological effects in both humans and wildlife (Miller et al., 2001; Routledge and Sumpter, 1996). Many nonsteroidal substances have the ability to bind to the human estrogen receptor α (ERα) and to mimic the natural estrogen 17β-estradiol, many of these being xenoestrogens that are thought to disrupt the normal endocrine function in humans and animals (De Boever et al., 2001). Compounds which demonstrate estrogenic activity are often detected in wastewater effluent (Layton et al., 2000). Furthermore, wastewater effluent has been shown to be a significant route for the release of estrogenic compounds into environmental waterways (Fernandez et al., 2007; Korner et al., 2001).

Several studies have been performed in the past decade that have utilized recombinant yeast strains capable of identifying compounds with the ability to interact with the human estrogen receptor, referred to as a recombinant yeast estrogen screen (rYES). This assay utilizes genetically modified strains of the yeast S. cerevisiae that harbor an estrogen receptor expression cassette along with a reporter construct (De Boever et al., 2001). The rYES was first described in detail by Routledge and Sumpter (1996) and has been employed in numerous subsequent studies for the assessment of estrogenic activity in a variety of sample types, including commercial chemical preparations as well as environmental samples, such as wastewater (Fernandez et al., 2007; Miller et al., 2001; Thorpe et al., 2006). The use of this yeast-based assay system proved to be convenient due to the rapid growth rate of S. cerevisiae, the ease of plasmid exchange, promoter availability, relative low assay cost, and the high conservation of regulatory mechanisms between mammalian and yeast cells in regards to this system. Yeast-based systems are highly sensitive, with relative low labor intensity and they allow for the screening of multiple samples in a short amount of time (Routledge and Sumpter, 1996).

The rYES assay was modified to overcome some of its less desirable qualities, including a 3-day completion time and possible interference of the chromogenic indicator substance used in the assay (chlorophenol red-β-D-galactopyranoside) and its product, both of which may possess estrogenic activity (De Boever et al., 2001). The subsequent modifications improved upon the original assay, but still resulted in time- and labor-intensive assay systems, some of which require 24-hour incubations (De Boever et al., 2001; Wagner and Oehlmann, 2009) or a 12-hour incubation involving measurements being taken every 60 minutes (Sanseverino et al., 2009).

There are additional yeast-based bioreporters in use which employ various reporter/detection methods, such as: an estrogen-inducible lux-based bioluminescent reporter assay using the S. cerevisiae BLYES estrogen sensitive strain, which produces estrogen-induced bioluminescence (Sanseverino et al., 2009; Sanseverino et al., 2005), green fluorescent protein (Beck et al., 2006), or the firefly luciferase bioreporter. The bioluminescent reporter assay described by Sanseverino et al. (2005) showed similar detection levels to the colorimetric-based lacZ assay systems based on certain estrogenic chemicals, but still requires a six hour incubation period to reach maximum bioluminescence, with measurements being taken every 60 minutes for 12 hours. The yeast based estrogen screen using green fluorescent protein (GFP) as described by Beck et al. (2005) demonstrates optimal fluorescence after an incubation time of 6 hours and involves a series of steps not included in rYES assay systems.

Some researchers opt to utilize mammalian cell-based reporter systems in order to screen for estrogenic activity. Mammalian GFP expression involving the use of stably transfected MCF-7 cells, which are derived from a human breast cancer line expressing the estrogen receptor (ER), does serve as a sensitive estrogen detection system (Miller et al., 2000). A significant draw-back to this and other mammalian cell-based reporter systems is the relatively high cost, long cell growth periods, and the need to sterilize or treat samples prior to applying them to the cells. When using the chemically activated luciferase gene expression (CALUX) human cell-derived reporter bioassay, one must pay particular attention to technique and equipment in order to avoid potential contamination and filtration and/or extraction of samples prior to treating the cells is necessary (van der Burg et al., 2008). In addition, it is not always clear that the observed effect/signal observed using the CALUX system is solely the result of ERα transactivation through estrogen receptor response elements. For example, MCF-7 human breast cancer cells carrying a stable ERα-responsive luciferase reporter construct not only express ERα but also ERβ, other steroid hormone receptors, and other transcription factors (e.g. redox/stress activated factors like AP1). Many of these factors could also be activated or blocked by a chemical when testing in a mammalian cell system. Thus, the yeast system is a “cleaner” system.

The yeast assay described here takes advantage of a commercially available chemiluminescent substrate for the detection of estrogen-induced β-galactosidase expression. Using this assay an estrogen-induced signal can be detected within 30 minutes and the total assay time from start to finish is no more than 4 hours. More importantly, due to the short assay time, wastewater samples can be assayed without the need for sample extraction, concentration and sterilization. This assay protocol represents a quicker and simpler alternative to the yeast-based assays currently in use.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Estrone (E1), 17β-estradiol (E2), 17α-ethynylestradiol (EE), Bisphenol A (BPA), and nonylphenol Technical Mixtures (NP) were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (MO, USA). Nonylphenol standard solution in methanol was supplied by AccuStandard (CT, USA). E2 (3,4 - 13C2), BPA (ring 13C12) and p-n-Nonylphenol (ring 13C6) internal standards were from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc (MA, USA). HPLC grade methanol, acetic acid anhydride and sodium carbonate were from VWR (USA). Stir bars (Twister®, 10mm×1 mm; coated with polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS) were purchased from Gerstel Inc. (MD, USA). Stock solutions of the individual EDC and a combined working solution for gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC/MS) were prepared in methanol. For yeast assays, all hormones and EDCs were prepared as 10 mM stock solutions in ethanol. All solutions were stored at −4 °C until used.

2.2. Sample collection

Twenty-four hour composite wastewater samples (influent and effluent) from five Wastewater Treatment Plants (WWTPs) in El Paso, TX, USA were collected in winter and summer 2009 and stored in amber glass bottles. Upon return to the laboratory, the samples were immediately filtered through Whatman GF-F glassfiber filters (pore size 0.7 μM) to minimize possible biological degradation. Chemically treated effluent samples were treated with lime, carbon dioxide (for pH adjustment), and chlorine during the wastewater treatment process before collection. Biologically treated effluent samples were chemically treated as described above and biologically filtered/biodegraded during the wastewater treatment process prior to sample collection. The biological filtration/biodegradation treatment process involves passing the wastewater through activated sludge.

2.3. Four-hour yeast bioassay

The four-hour yeast bioassay illustrated in Figure 1 is a modified version of a receptor-mediated β-galactosidase reporter assay that was previously described for use in the functional analysis of receptor regulatory proteins (Balsiger and Cox, 2009; Riggs et al., 2003). W303α (MATα leu2-112 ura3-1 trp1-1 his3-11,15 ade2-1 can1-100 GAL SUC2) with a deleted pleiotrophic drug resistance gene (PDR5) was the parental yeast strain for all assays described. The deletion of PDR5 in this strain was performed using methods previously described (Gueldener et al., 2002). The parent strain was co-transformed with a TRP1-marked constitutive human ERα expression plasmid (pG/ER) and a URA3-marked estrogen-inducible β-galactosidase reporter plasmid (pUCΔSS-ERE, both plasmids kindly provided by Didier Picard, University of Geneva) and maintained in synthetic complete media lacking uracil and tryptophan (SC-UW) to select for plasmid retention. For all assays described the yeast reporter strain was cultured overnight in synthetic complete media lacking uracil and tryptophan (SC-UW) at 30°C in a shaking water bath. The next morning the cells were diluted back to an optical density of 0.08 at 600 nm (O.D.600) and incubated in a shaking water bath at 30°C until the culture reached and O.D.600 of 0.1. If the waste water samples were measured directly (Figure 1, left side) the yeast culture in log phase growth was aliquoted into 14 ml snap-cap tubes at 1 ml per tube. The cells were then harvested by centrifugation at 2000 rpm for 2 min. and suspended in 1 ml of SC-UW prepared by mixing 750 μl of waste water with 250 μl of 4X concentrated SC-UW for each assay to be performed. The cultures were then incubated at 30°C with shaking for 2 hours. One hundred μl from each culture was then transferred to an opaque 96-well plate in preparation for the addition of substrate. It is important to note that, in this case, the wastewater sample was straight from the source and was not extracted, concentrated, or sterilized in any way unless otherwise stated. For all assays a 17β-estradiol standard curve was performed in parallel. Standards in this case were prepared by diluting 17β-estradiol into distilled, deionized water and treating it in the same manner as the waste water samples. In the event that extracted and/or concentrated samples were being assayed (Figure 1, right side) the growing culture was then aliquoted into an opaque 96-well plate at 100 ul per well. The concentrated samples or hormone standards in ethanol vehicle were then added directly to the wells and the plate was incubated at 30°C for 2 hours. The amount of ethanol added never exceeded 1% of the total culture volume. After the 2 hour incubation in the presence of hormone 100 μl of Tropix Gal-Screen in Buffer B (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) was added to each well and the plate was incubated for an additional 2 hours at room temperature. The hormone-induced chemiluminescent signal was then measured on a Luminoskan Ascent microplate luminometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., Waltham, MA).

Figure 1.

An illustration of the four-hour yeast bioassay protocol. A saturated overnight culture is diluted back to an O.D.600 of 0.08 and allowed to reach log phase growth before the addition of sample. Wastewater samples that typically have higher levels of contaminants can be assayed directly by mixing with concentrated yeast medium and placed on the cells for 2 hours prior to substrate addition (left panel). The samples can be extracted and concentrated as with traditional yeast assays when ligand levels are below values needed for direct detection. However, in this assay, the cells only need to be treated with concentrated sample for 2 hours prior to substrate addition and, thus, the concentrated samples can still be assayed in a 4-hour time frame (right panel).

2.4. Stir bar sorptive extraction (SBSE) with in situ derivatization of estrogens from wastewater samples

Wastewater sample(s) was/were placed in a centrifuge tube with a surrogate standard and centrifuged for 10 minutes at 4100 rpm. Twenty milliliters of the water sample were transferred to a 20 mL screw cap vial and 200 mg of sodium carbonate as the pH adjustment agent (pH 11.5) as well as 200 μL of acetic acid anhydride were added as the derivatization reagent. A preconditioned Stir Bar (conditioned for 3 h at 300 °C in a flow of nitrogen) was placed in each vial and the samples were stirred at 1000 rpm for 4 hours. After the extraction, the Stir Bar was removed with forceps, rinsed with purified water and dried with lint-free tissue paper. The Stir Bar was thermally desorbed in a Thermal Desorption (TDU) system that allowed EDCs to be released from the Stir Bar and subsequently analyzed by a GC–MS system (Agilent, Inc.).

2.5. Instrumental analysis- TDU-GC-MS

The stir bars were thermally desorbed in a thermal desorption unit (TDU) (Gerstel, US) under splitless mode. The desorption process was programmed as follows: initial temperature at 40 °C with a ramp of 60 °C min−1 to 300 °C (held for 7 minutes). The transfer line temperature was set at 300 °C. The desorbed EDCs were then cryo-focused in a baffle liner in a cryo-injection system (CIS4) at −40 °C under liquid nitrogen prior to injection. The CIS 4 instrument was programmed as follows: initial temperature at −40 °C, ramp at 12 °C s−1 to 300 °C and hold for 10 minutes. The separations were performed on a Zebron ZB-5MS capillary column (0.25 mm× 30 m× 0.25 μm, Phenomenex, CA). The oven was programmed as follows: initial temperature set at 60 °C with 15 °C min−1 ramp to 300 °C and held for 5 minutes. The carrier gas used was ultra pure helium at a constant flow of 1.2 mL min−1. The mass spectrometer was operated in the selected-ion monitoring mode with electron-impact ionization (ionization voltage, 70 eV). Target compounds were measured based on the following quantification ions on selected ion monitoring mode: BPA (Bisphenol A): m/z = 213, 228; E1 (Estrone): m/z = 270; E2 (17β-estradiol): m/z = 272; EE (17α-ethynylestradiol): m/z = 213, 296; NP (Nonylphenol): m/z = 107, 135, 149; BPA 13C12 (Bisphenol, Ring 13C12): m/z = 225, 240; p-n-NP 13C6 (para-n-Nonylphenol, Ring 13C6): m/z = 113. Ten-point calibration curves were conducted ranging from 0.005 to 100 μg L−1. The linear response of the curves produced correlation coefficients (R2) higher than 0.99 for all EDCs.

2.6. Calculation of E2 equivalents (EEQ)

The total estrogenic activity of a wastewater sample was determined by the four-hour yeast bioassay. Based on the response, the activities of the unknown samples were interpolated from a dose-response curve of the standard compound E2 in mol L−1 and were converted into ng L−1 E2-equivalent (EEQ).

In addition, EEQ values could be determined by chemical analysis (expressed as EEQGC-MS). To calculate EEQGC-MS, the estradiol equivalency factor (EEF) for each EDC (i) based on its half maximal effective concentration (EC50) value obtained from the yeast assay data was calculated using the following equation:

| (1) |

Where, EEF (i) is the estradiol equivalency factor for EDC (i) (ng L−1), and EC50 (E2) is the half maximal effective concentration for E2 (mol L−1). EC50 (i) is the maximal effective concentration for EDC (i) (mol L−1), which represents the EC50 of the individual EDC, not the maximal effective concentration of E2.

Using EEF and the concentrations of each EDC obtained by the GC-MS analysis (ci), the EEQGC-MS for each wastewater sample was calculated using the following equation:

| (2) |

Where, EEQGC-MS is estradiol equivalents determined by GC-MS and C(i) is the concentration of EDC(i) determined by GC-MS. The sum of the calculated E2 equivalent values for the individual compounds represents the calculated overall estrogenicity (EEQGC-MS) of the sample.

The total estrogenic activity of a wastewater sample was determined by the four-hour yeast bioassay. A standard dose–response curve for 17β-estradiol (E2) was conducted based on the four-parameter logistic equation (GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows, GraphPad Software, San Diego California USA). Estradiol equivalents (EEQ, in mol L−1) of the water samples were calculated based on the following equation:

where Top and Bottom are the maximal and the basal response respectively, EC50 of the agonist is the concentration that provokes a response half way between the basal (Bottom) response and the maximal (Top) response, and y is the activity response of the sample. The software automatically generates these parameters, Bottom, Top, Hill Slope, and logEC50, upon creating the dose-response curve.

The EEQ obtained from the equation above has a unit in mol L−1. To be consistent with the value obtained by chemical analysis, the value was then converted into ng L−1 by multiplying the molecular mass (in ng mol−1) of the compound.

2.7. Statistical analysis

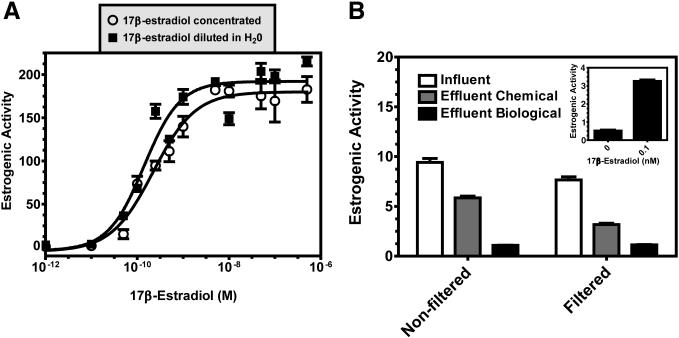

In all data graphs presented in Figures 2 and 3, the term estrogenic activity represents ERα-mediated transcription of the β-galactosidase reporter gene and the level of estrogenic activity is determined by the direct measure of β-galactosidase enzymatic activity. All data shown are representative of at least three independent experiments with all samples measured in triplicate within each experiment. Statistical significance in Figure 2B was calculated by two-way analysis of variance followed by a Bonferroni post-test. A p value < 0.05 was taken to represent a statistically significant difference.

Figure 2.

Four-hour yeast bioassay method comparisons. A) Representative 17β-estradiol dose-response curves in which the ligand solubilized in ethanol vehicle was added directly to the wells (open circles; Figure 1 right panel) or was diluted in water and treated the same as wastewater samples (closed squares, Figure 1 left panel) are shown. The resulting EC50 values averaged from 3 independent assays±standard deviation were 1.45 × 10−10 M±0.1 for concentrated ligand and 1.51 × 10−10 M±0.1 for ligand diluted in water. B) Water samples taken from the same wastewater treatment plant were either assayed directly without any preparation or assayed after filtration to remove particulates and filter sterilization through a 0.2 μm filter. Effluent “Chemical” represents samples that were chemically treated prior to sample collection. Effluent “Biological” represents samples that were both chemically treated and biologically filtered prior to sample collection (see Materials and Methods for a detailed description of these treatment processes). Each data point is an average of three replicates with error bars representing standard deviation. The data obtained from the filtered samples were significantly reduced as compared to the non-filtered samples with a p value < 0.001. The inset is a 17β-estradiol positive control shown at 0 and 0.1 nM.

Figure 3.

Dose-response curves for typical estrogenic wastewater contaminants using the four-hour yeast bioassay. Representative dose-response curves for the indicated ligands using the four-hour yeast bioassay are shown. The ligands used include 17β-estradiol (closed circle), 17α-ethynylestradiol (closed upside down triangle), estrone (closed upright triangle), nonylphenol (open square), and bisphenol A (open upside down triangle). All data points are averages of 3 independent replicates with error bars representing standard deviation.

3. Results

3.1. Yeast Bioassay

The sensitivity of the chemiluminescent β-galactosidase substrate has allowed for the steroid hormone receptor-mediated reporter assays to be conducted within a more physiological time frame compared to the alternative assays in use. Thus, the yeast-based steroid hormone receptor-mediated reporter assay using a chemiluminescent substrate has been used extensively for the analysis of receptor regulatory proteins (Balsiger and Cox, 2009; Cox et al., 2007; Riggs et al., 2007; Riggs et al., 2003). Given the utility of this assay in mechanistic studies we reasoned that a modified version of the assay would also benefit those interested in the screening of environmental samples. The relative simplicity of the modified receptor-mediated β-galactosidase reporter assay described herein is illustrated in Figure 1. Unlike the current yeast assay systems used to screen for estrogenic activity, which could take 12 to 36 hours, our modified assay takes only 4 hours to analyze samples with very little hands on time. Although the assay takes 4 hours to complete, the cells are grown in the presence of hormone or unknown sample for only 2 hours prior to cell lysis and substrate addition. The chemiluminescent signal peaks after 30 minutes and remains constant for approximately 2 hours after substrate addition (Riggs et al., 2003). Thus, we chose a 2 hour incubation time after substrate addition in order to ensure maximal chemiluminescent signal. The assay sensitivity is comparable to the mammalian CALUX assays in that an estrogenic signal can be detected to concentrations as low as 100-200 pM estradiol. Wastewater samples which contain high levels of estrogenic compounds can be directly measured without extraction or sterilization, which significantly reduces the time between sample collection and data acquisition. In this instance the wastewater sample is diluted at a ratio of 1:4 in 4X concentrated yeast medium and incubated for 2 hours at 30°C prior to transferring to a 96-well plate and adding substrate (Figure 1; left side). Samples containing estradiol equivalents below the lowest detectable limit can still be assayed in a 4-hour time period but will need extraction and concentration (Figure 1, right side).

In order to demonstrate that there is no difference in the outcome of the assay regardless of whether water samples are tested directly or concentrated before assaying we performed 17β-estradiol dose response curves in parallel using each of the assay protocols detailed in Figure 1. The EC50 of 17β-estradiol obtained by assaying concentrated 17β-estradiol in a 96-well plate (Figure 1, right side) was determined to be 1.45 × 10−10 M±0.1. The EC50 of 17β-estradiol assayed directly in water samples (17β-estradiol was diluted into distilled, deionized water and treated in the same manner as the wastewater samples; Figure 1, left side) was determined to be 1.51 × 10−10 M±0.1. The resulting dose-response curves of 17β-estradiol (concentrated vs. diluted in water) are shown in Figure 2A. The similar dose-response curves and EC50 values of the two control methods used to assess the estrogenic activity of 17β-estradiol demonstrate the relevance of the assay method in the evaluation of estrogenic compounds within wastewater samples without the need to concentrate samples prior to analysis.

Given the short 2 hour time period in which cells are allowed to grow in the presence of the wastewater, we questioned whether filtration and/or sterilization of the wastewater were necessary. Both sterile filtered and non-filtered wastewater samples were analyzed for estrogenic activity using the four-hour yeast bioassay (Figure 2B). The samples included wastewater influent, chemically treated effluent, and both chemically treated and biologically filtered effluent and were taken from the same wastewater treatment plant. The samples designated as “non-filtered” were not prepared in any way before water samples were removed for the assay. The samples designated as “filtered” were filtered and sterilized through a 0.2 μm filter. Sterile filtration of the samples, regardless of sample type lowered the overall estrogenic activity. Samples that were assayed without filtration displayed a 38% decrease in estrogenic activity after chemical treatment whereas those samples that were filtered displayed a 59% decrease. It is clear that in addition to reducing the overall estrogenic activity that can be measured within the samples, filtration of the samples also alters the data trends, which is likely the result of estrogens associated with small particulates that were removed during filtration. Thus, filtration of the samples prior to the assay is not necessary and, if performed, will likely reduce the levels of estrogen detected. The data presented in Figure 2B also demonstrate that the four-hour yeast bioassay can be used to effectively monitor the quality of treatment methodologies in the removal of estrogens from wastewater.

Dose-response curves of typical estrogenic ligands using the modified four-hour receptor-mediated β-galactosidase reporter assay are shown in Figure 3. 17β-estradiol, 17α-ethynylestradiol, estrone, nonylphenol, and bisphenol A were all analyzed for estrogenic activity in the same manner as extracted/concentrated samples by adding directly to the wells before incubating at 30°C for 2 hours (Figure 1, right panel). The EC50 values of the ligands range from the most sensitive, 17β-estradiol, with an EC50 of 1.45 × 10−10 M to the least sensitive, bisphenol A, with an EC50 of 3.43 × 10−6 M (Table 1).

Table 1.

EC50 Values for Typical Estrogenic Wastewater Contaminants

| Compound | EC50 (M)a,b |

|---|---|

| β-estradiol | 1.45 × 10−10 ± 0.1 |

| 17α-Ethynylestradiol | 1.93 × 10−10 ± 0.0 |

| Estrone | 1.28 × 10−9 ± 0.1 |

| Nonylphenol | 2.48 × 10−8 ± 3.9 |

| Bisphenol A | 3.43 × 10−6 ± 0.8 |

EC50 values (average ± SD)

For all samples, n=3

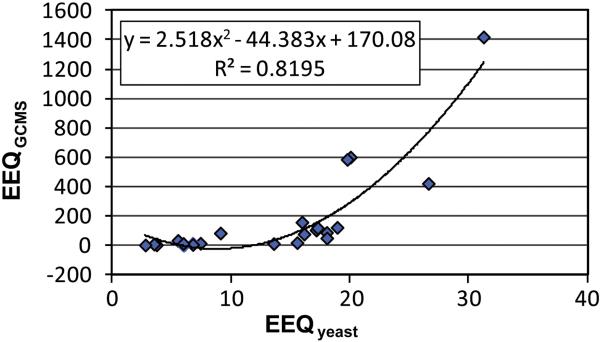

3.2. Comparison of the four-hour yeast bioassay and chemical analysis

For an exemplary comparison, the corresponding data for the samples taken in two plants in the winter of 2008 and the summer of 2009 are listed in Table 2. The measured estrogenicities by bioassay (EEQyeast) for the wastewater samples from different wastewater treatment plants (WWTPs) were compared with the results (EEQGC-MS) calculated by EEF and concentrations determined by chemical analysis of the same samples. The (EEQyeast) measured in the samples ranged from no activity (NA) to 28.4 ng L−1 while the calculated estrogenic activity (EEQGC-MS) ranged from 2.1 to 155.9 ng L-1. A 2nd order polynomial regression analysis using the measured and calculated EEQ values shows that there is a positive correlation between EEQyeast and EEQGC-MS (Figure 4). This implies that the higher the concentration of EDCs in the water, the higher the estrogenic activity reflected in the yeast assay. The authors observed that EEQGC-MS values were approximately 3 times greater than EEQyeast. A similar observation was reported in other studies (Beck et al., 2006; Nakada et al., 2004) in which chemical analysis predicted higher estrogenic activity than what was measured in the bioassay. Though the differences between measured and calculated EEQs could have various reasons, low EEQyeast values could suggest that potential interfering (antagonistic) compounds were present in the water samples (Salste et al., 2007). It should also be noted that the chemical analysis-derived EEQ were found lower than the bioassay derived EEQ in the same sample in some studies (Nelson et al., 2007). The mixed results once again showed that the environmental sample matrices are complicated. Chemical analysis is only focused on the determination of target substances in wastewater. The result is limited in providing a complete account of all EDCs existing in wastewater. The biological response of the yeast assay is complex and includes all estrogen-like compounds capable of binding to the receptor. This could lead to synergism, potentiation, and/or inhibition of the response, depending upon the quantities and combination of compounds present (Wozei and Hermanowicz, 2006). Despite the discrepancy, the estrogenic activities measured in wastewater influent samples were consistently higher than what were in the effluent. The results from this study demonstrate that this assay is a good sample screening tool for total estrogenic activity in wastewater samples.

Table 2.

Measured Estrogenicities by Bioassay Compared to Chemical Analysis

| Measured EEQyeast |

Calculated EEQGCMS |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Winter 2008 | EEQ | RSD | EEQ | RSD | |

| Plant A | Influent | 20.26 | 2.78 | 102.59 | 4.45 |

| Effluent | 6.75 | 6.30 | 2.14 | 6.66 | |

| Plant B | Influent | 22.09 | 3.45 | 120.73 | 6.77 |

| Effluent | NA | NA | 14.78 | 10.16 | |

| Summer 2009 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Plant A | Influent | 18.30 | 2.58 | 75.34 | 4.45 |

| Effluent | 7.40 | 0.99 | 1.36 | 0.16 | |

| Plant B | Influent | 18.11 | 3.99 | 155.96 | 10.62 |

| Effluent | 7.42 | 1.14 | 11.39 | 24.23 | |

Figure 4.

A correlation between EEQGCMS and EEQyeast. A second order polynomial regression analysis reveals a positive correlation between the estrogenic activity determined by direct biological measurement (EEQyeast) and by chemical analysis (EEQGCMS). EEQGCMS is the calculated overall estrogenicity based on the concentration of individual compounds detected and their relative potencies. EEQyeast, is the measured estrogenicity determined by the yeast bioassay.

4. Discussion

The Yeast Estrogen Screen (YES) (Routledge and Sumpter, 1996) is a widely utilized reporter assay for detecting estrogenic activity. This assay system has previously been used to detect estrogen receptor interactions in wastewater treatment systems (Layton et al., 2000) and has been successfully adapted to a wide range of applications (Sanseverino et al., 2009). It still remains a time-consuming assay process, however, involving incubation times ranging from 12 hours to 3 days (De Boever et al., 2001; Fox et al., 2008; Routledge and Sumpter, 1996; Sanseverino et al., 2009; Wagner and Oehlmann, 2009).

Our modifications of the recombinant yeast bioassay into a four-hour direct measure assay has allowed for the timely processing of environmental water/wastewater samples in a cost-effective manner. We have eliminated the need to extract, concentrate, or sterilize the samples, thereby reducing time and labor necessary for data acquisition. It is also important to emphasize that this assay system offers a significant improvement in overall assay time, even for samples which fall below the detectable limits, once they have been extracted and concentrated. A similar assay time has been achieved with a bioluminescent estrogen-responsive reporter for screening wastewater samples (Leskinenet al., 2005; Salste et al., 2007). In the studies conducted by Salste et al. (2007) the wastewater samples were concentrated by freeze drying. Although this assay could prove to be similarly useful to the assay reported here no information regarding the effect of freeze drying on the measured activity is reported. Depending upon the degree to which the samples are dried, problems with lipophilic compounds sticking to surfaces and not resolubilizing are possible. When compared to a typical CALUX assay system, our yeast bioassay is substantially quicker, with a turnaround time of 2-4 hours, rather than 2-4 days. The EC50 for 17β-estradiol in the ER-CALUX assay was previous determined to be 6 pM (Legler et al., 2002). Thus, the CALUX system does generally offer a more sensitive assay but it is also a more expensive system when compared to the yeast bioassay. Colorimetric assays may be slightly less expensive than our yeast bioassay, but it does require more time per sample and does not offer an increase in sensitivity. Taking cost, sample preparation time, assay time and sensitivity all into consideration, our yeast bioassay is an important and viable tool for the screening of environmental samples.

In addition, our bioassay can function as a screening tool to determine whether further chemical analysis is necessary. Based on the positive correlation between bioassay and chemical analysis of screened samples, it is possible to use our modified yeast assay system as the first line of screening to select the samples which would require additional chemical analysis. This would allow the conservation of resources by eliminating unnecessary chemical analysis of samples which lack initial estrogenic activity in the yeast bioassay.

The ligands which were evaluated using our modified yeast bioassay system are among those which typically produce estrogenic activity, including the four chemicals which have been identified as those principally responsible for estrogenic activity in certain wastewater effluents (β-estradiol, estrone, 17α-ethynylestradiol, and nonylphenol) (Thorpe et al., 2006). Nonylphenol makes its way into wastewater as a break-down product of soaps and detergents. Bisphenol A (BPA), another chemical evaluated using this bioassay, is an industrial chemical present throughout the environment which is used as a plasticizer and is a known EDC (Fernandez et al., 2007; Wagner and Oehlmann, 2009). This particular bioassay approach has been determined to be sensitive to known effluent-borne pollutants, which demonstrates both environmental relevance and applicability.

The EC50 results using our yeast bioassay are very similar to the results obtained from other YES assay systems, with the exception of nonylphenol (Folmar et al., 2002; Sanseverino et al., 2005). The EC50 of nonylphenol reported by Sanseverino et al (2005) was 1.7 × 10−5 M using the BLYES assay system, which is 103 less sensitive than the EC50 value we determined using our yeast bioassay (2.48 × 10−8 M). In addition, our bioassay system detection results are ten-fold higher than the BLYES assay system for E2, Estrone, and EE2. The method published by Sanseverino et al (2005) requires the drying of methanolic extracts in the wells prior to the addition of the yeast culture. A concern with this approach is the fact that steroidal ligands are lipophilic and tend to stick to the plastic surfaces of tubes and wells. In the absence of proper controls one cannot be certain that 100% of the bioactive compounds will solubilize upon addition of the yeast culture. Thus, it is possible that this difference in methodology could account for some differences in sensitivity to ligands.

Folmar et al (2002) used a YES assay system to evaluate nonylphenol, which resulted in an EC50 value of 2.9 × 10−4 M, 104 less sensitive than our assay results. The parental yeast strain used in our assay has the PDR5 “drug pump” gene deleted from the W303α genetic background. PDR5, or pleiotropic drug resistance gene 5, is an ATP-binding cassette multidrug transporter in yeast that is able to lead to resistance to a variety of cytotoxic compounds which are not structurally similar (Egner et al., 1995). Pdr5 has been shown to reduce the intracellular concentration of estradiol and other steroid substrates, possibly by facilitating the efflux of such substrates across the plasma membrane (Mahé et al., 1996). By using a yeast strain without this multidrug transporter gene, we are attempting to avoid the possible transport of estrogen-like ligands from the yeast cells. Ligand retention within the yeast cells allows for a more sensitive assay, and can possibly explain the increased sensitivity of our assay concerning NP when compared to other published data. Nonylphenol ethoxylate is a known substrate for the multiple drug resistance 1 protein (Mdr1p) in mammalian cells (Charuk et al., 1998), and, although it has not been shown, it is plausible that Pdr5 in yeast can recognize and transport nonylphenol.

It is possible to apply this same yeast bioassay protocol to a variety of receptor-ligand systems in order to further examine water/wastewater for various toxins. This assay system is currently being applied to other receptors, such as the androgen, glucocorticoid, and aryl hydrocarbon receptors in our lab. These assays are all detecting within the nanomolar range for the ligands tested. We are currently working towards increasing the sensitivity of these additional receptor assays as well as their potential environmental applicability through the use of receptor mutants that respond more robustly to ligand. In addition, we are assessing the effect of various receptor-associated cochaperone proteins for the ability to increase assay sensitivity. It is our intention to develop a variety of sensitive, cost-effective, and relatively quick assays which can be applied within the realm of environmental science. One example of possible environmental relevance is the case of intersex black basses from U.S. rivers, where chemical contaminants were found in river systems which had multiple species of intersex fishes. We believe that our assay could serve as a tool to be used to identify possible estrogenic activity directly from suspect water samples such as these, thereby enhancing the information gleaned from the study in regards to the potential effects of EDCs on wildlife (Hinck et al., 2009).

5. Conclusion

The development of a four-hour direct-measure yeast bioassay capable of being applied to environmental water/wastewater screening in an accurate, timely, sensitive, and cost-effective manner is beneficial to the environmental health field and to those whose careers and/or interests compel them to study within this field. Our assay has a variety of applications with the potential for the employment of several receptors which can serve as excellent screening tools. The modifications we made to the yeast bioassay have allowed for the user to more efficiently process samples directly without the need to extract, concentrate, or sterilize the samples, thereby reducing time and labor necessary for essential data acquisition. We must also emphasize that this assay system offers a significant improvement in overall assay time even for samples which must be extracted and concentrated prior to performing the bioassay. This assay protocol represents a quicker and simpler alternative to the yeast-based assays currently in use. Given the short assay time the development of a field-based assay protocol may be possible in the future.

Acknowledgements

M.B.C. is supported in part by Grant Number 5G12RR008124 (to the Border Biomedical Research Center/University of Texas at El Paso) from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR/NIH). Support by NIH SCORE Program at UTEP (Project Number 2S06GM008012-38) is acknowledged. We thank the Biomolecule Analysis Core Facility (NIH/NCRR Grant Number 5G12RR008124) for the use of the instruments. The authors are grateful to Chuck Miller for providing reagents and comments on the manuscript. The authors would like to thank Didier Picard for generously providing plasmids.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Declaration: The authors declare that there are no competing interests, commercial or otherwise, associated with this manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Balsiger HA, Cox MB. Yeast-based reporter assays for the functional characterization of cochaperone interactions with steroid hormone receptors. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;505:141–56. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60327-575-0_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck I-C, Bruhn R, Gandrass J. Analysis of estrogenic activity in coastal surface waters of the Baltic Sea using the yeast estrogen screen. Chemosphere. 2005a;63:1870–78. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck V, Pfitscher A, Jungbauer A. GFP-reporter for a high throughput assay to monitor estrogenic compounds. J Biochem Biophys Methods. 2006;64:19–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jbbm.2005.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charuk MH, Grey AA, Reithmeier RA. Identification of the synthetic surfactant nonylphenol ethoxylate: a P-glycoprotein substrate in human urine. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:F1127–39. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1998.274.6.F1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox MB, Riggs DL, Hessling M, Schumacher F, Buchner J, Smith DF. FK506-binding protein phosphorylation: a potential mechanism for regulating steroid hormone receptor activity. Mol Endocrinol. 2007;21:2956–67. doi: 10.1210/me.2006-0547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Boever P, Demare W, Vanderperren E, Cooreman K, Bossier P, Verstraete W. Optimization of a yeast estrogen screen and its applicability to study the release of estrogenic isoflavones from a soygerm powder. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:691–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egner R, Mahe Y, Pandjaitan R, Kuchler K. Endocytosis and vacuolar degradation of the plasma membrane-localized Pdr5 ATP-binding cassette multidrug transporter in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1995;15:5879–87. doi: 10.1128/mcb.15.11.5879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez MP, Campbell PM, Ikonomou MG, Devlin RH. Assessment of environmental estrogens and the intersex/sex reversal capacity for chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha) in primary and final municipal wastewater effluents. Environ Int. 2007;33:391–6. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2006.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folmar LC, Hemmer MJ, Denslow ND, Kroll K, Chen J, Cheek A, et al. A comparison of the estrogenic potencies of estradiol, ethynylestradiol, diethylstilbestrol, nonylphenol and methoxychlor in vivo and in vitro. Aquat Toxicol. 2002;60:1–2. doi: 10.1016/s0166-445x(01)00276-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox JE, Burow ME, McLachlan JA, Miller CA., 3rd Detecting ligands and dissecting nuclear receptor-signaling pathways using recombinant strains of the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Nat Protoc. 2008;3:637–45. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gueldener U, Heinisch J, Koehler GJ, Voss D, Hegemann JH. A second set of loxP marker cassettes for Cre-mediated multiple gene knockouts in budding yeast. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:e23. doi: 10.1093/nar/30.6.e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinck JE, Blazer VS, Schmitt CJ, Papoulias DM, Tillitt DE. Widespread occurrence of intersex in black basses (Micropterus spp.) from U.S. rivers, 1995-2004. Aquat Toxicol. 2009;95:60–70. doi: 10.1016/j.aquatox.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korner W, Spengler P, Bolz U, Schuller W, Hanf V, Metzger JW. Substances with estrogenic activity in effluents of sewage treatment plants in southwestern Germany. 2. Biological analysis. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2001;20:2142–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Layton AC, Gregory BW, Seward JR, Schultz TW, Sayler GS. Mineralization of Steroidal Hormones by Biosolids in Wastewater Treatment Systems in Tennessee U.S.A. Environ Sci Technol. 2000;34:3925–31. [Google Scholar]

- Legler J, Dennekamp M, Vethaak AD, Brouwer A, Koeman JH, Van der Burg B, et al. Detection of estrogenic activity in sediment-associated compounds using in vitro reporter gene assays. Sci Total Environ. 2002;293:69–83. doi: 10.1016/s0048-9697(01)01146-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leskinen P, Michelini E, Picard D, Karp M, Virta M. Bioluminescent yeast assays for detecting estrogenic and androgenic activity in different matrices. Chemosphere. 2005;61:259–66. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2005.01.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahé Y, Lemoine Y, Kuchler K. The ATP binding cassette transporters Pdr5 and Snq2 of Saccharomyces cerevisiae can mediate transport of steroids in vivo. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:25167–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.41.25167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller D, Wheals BB, Beresford N, Sumpter JP. Estrogenic activity of phenolic additives determined by an in vitro yeast bioassay. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:133–8. doi: 10.1289/ehp.109-1240632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller S, Kennedy D, Thomson J, Han F, Smith R, Ing N, et al. A Rapid and Sensitive Reporter Gene that Uses Green Fluorescent Protein Expression to Detect Chemicals with Estrogenic Activity. Toxicol Sci. 2000;55:69–77. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/55.1.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakada N, Nyunoya H, Nakamura M, Hara A, Iguchi T, Takada H. Identification of estrogenic compounds in wastewater effluent. Environ Toxicol Chem. 2004;23:2807–15. doi: 10.1897/03-699.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson J, Bishay F, van Roodselaar A, Ikonomou M, Law FC. The use of in vitro bioassays to quantify endocrine disrupting chemicals in municipal wastewater treatment plant effluents. Sci Total Environ. 2007;374:80–90. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2006.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs DL, Cox MB, Tardif HL, Hessling M, Buchner J, Smith DF. Noncatalytic role of the FKBP52 peptidyl-prolyl isomerase domain in the regulation of steroid hormone signaling. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:8658–69. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00985-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs DL, Roberts PJ, Chirillo SC, Cheung-Flynn J, Prapapanich V, Ratajczak T, et al. The Hsp90-binding peptidylprolyl isomerase FKBP52 potentiates glucocorticoid signaling in vivo. EMBO J. 2003;22:1158–67. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routledge EJ, Sumpter JP. Estrogenic Activity of Surfactants and Some of Their Degradation Products Assessed Using a Recombinant Yeast Screen. Environ Toxicol Chem. 1996;15:241–48. [Google Scholar]

- Salste L, Leskinen P, Virta M, Kronberg L. Determination of estrogens and estrogenic activity in wastewater effluent by chemical analysis and the bioluminescent yeast assay. Sci Total Environ. 2007;378:343–351. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2007.02.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanseverino J, Eldridge ML, Layton AC, Easter JP, Yarbrough J, Schultz TW, et al. Screening of potentially hormonally active chemicals using bioluminescent yeast bioreporters. Toxicol Sci. 2009;107:122–34. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfn229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanseverino J, Gupta RK, Layton AC, Patterson SS, Ripp SA, Saidak L, et al. Use of Saccharomyces cerevisiae BLYES Expressing Bacterial Bioluminescence for Rapid, Sensitive Detection of Estrogenic Compounds. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:4455–60. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.8.4455-4460.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe KL, Gross-Sorokin M, Johnson I, Brighty G, Tyler CR. An assessment of the model of concentration addition for predicting the estrogenic activity of chemical mixtures in wastewater treatment works effluents. Environ Health Perspect. 2006;114:90–7. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Burg B, Sonneveld E, Puijker LM, Man H-Y, Heringa MB, van der Linden SC, et al. Detection of Multiple Hormonal Activities in Wastewater Effluents and Surface Water, Using a Panel of Steroid Receptor CALUX Bioassays. Environ Sci Technol. 2008;42:5814–20. doi: 10.1021/es702897y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner M, Oehlmann J. Endocrine disruptors in bottled mineral water: total estrogenic burden and migration from plastic bottles. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 2009;16:278–86. doi: 10.1007/s11356-009-0107-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wozei E, Hermanowicz SW. Developing a yeast-based assay protocol to monitor total oestrogenic activity induced by 17 beta -oestradiol in activated sludge supernatants from batch experiments. Water S A. 2006;32:345–54. [Google Scholar]