Abstract

Objectives. We evaluated mammography rates for cognitively impaired women in the context of their life expectancies, given that guidelines do not recommend screening mammography in women with limited life expectancies because harms outweigh benefits.

Methods. We evaluated Medicare claims for women aged 70 years or older from the 2002 wave of the Health and Retirement Study to determine which women had screening mammography. We calculated population-based estimates of 2-year screening mammography prevalence and 4-year survival by cognitive status and age.

Results. Women with severe cognitive impairment had lower rates of mammography (18%) compared with women with normal cognition (45%). Nationally, an estimated 120 000 screening mammograms were performed among women with severe cognitive impairment despite this group's median survival of 3.3 years (95% confidence interval = 2.8, 3.7). Cognitively impaired women who had high net worth and were married had screening rates approaching 50%.

Conclusions. Although severe cognitive impairment is associated with lower screening mammography rates, certain subgroups with cognitive impairment are often screened despite lack of probable benefit. Given the limited life expectancy of women with severe cognitive impairment, guidelines should explicitly recommend against screening these women.

Screening mammography guidelines suggest that women with a life expectancy less than 4 to 5 years at the time of screening are unlikely to benefit from breast cancer screening and, thus, should not be screened.1–3 Although some cancer screening guidelines specify upper-age cutoffs for stopping screening as a surrogate for life expectancy (e.g., prostate-specific antigen screening guidelines suggest stopping at age 75 years),4 we do not know of any guidelines that specify the types of comorbidity that would preclude screening. This is despite the fact that certain comorbid conditions, such as dementia, are stronger predictors of life expectancy than age.5 Specifically, patients with dementia generally live less than 5 years6–12 and therefore are unlikely to benefit from screening mammography.

In addition, having dementia or severe cognitive impairment increases the likelihood that elderly women will experience harm from screening mammography (e.g., more psychological distress from false-positive results because of the inability to understand screening procedures, and more complications from the treatment of clinically insignificant disease).13,14 Moreover, screening mammography can distract care away from more pressing medical problems arising from either the cognitive impairment itself or from other comorbid conditions. However, it is unknown how often these women with severe cognitive impairment in the United States are undergoing screening mammography.

A few prior studies have examined screening mammography rates in women with cognitive impairment; however, they relied on self-report of screening mammography, which is likely to be inaccurate among women with cognitive impairment15–17 or older studies limited to a local geographic area.17,18 To our knowledge, there have not been any recent national studies that have used objective measures, such as Medicare claims, to document the actual mammography rates in older women with severe cognitive impairment. Such data are needed to determine current practice patterns and to identify whether cognitive status appropriately factors into screening mammography decisions.

Therefore, we conducted a study to document the actual rates of screening mammography in a US-representative sample of older women stratified according to their cognitive status. We used Medicare claims data linked to the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) to define rates of screening mammography (based on claims data) for women with differing levels of cognitive impairment. We also calculated survival according to level of cognitive impairment to validate that women with severe cognitive impairment defined by a standardized instrument have a median survival less than 5 years and are therefore unlikely to benefit from screening mammography.

METHODS

The HRS is a US-representative longitudinal study of health and wealth of noninstitutionalized adults aged 50 years and older with biennial data collection starting in 1992.19 The primary sample was obtained through a multistage, clustered area probability frame screening of household units. For about half of the respondents born before 1913, samples were additionally drawn from Medicare enrollment lists. Data were collected primarily through telephone interviews, and the overall response rate was 81%.20 We merged survey data from the HRS and claims data from the Center for Medicare Services to examine actual screening mammography rates of older women in the period 2 years prior to their 2002 HRS interview.

Women eligible for our study included the 4312 women who were aged 70 years or older at the 2002 wave of the HRS study. We excluded 939 women (22%) enrolled in Medicare managed care during the 2 years prior to their HRS interview because they lacked the opportunity to file Medicare claims. In addition, women had to be eligible for mammography screening. Therefore, we excluded 706 women because they had a history of breast cancer (n = 223; 5%) or a breast neoplasm (n = 483; 11%). The identification of a history of breast cancer or breast neoplasm was based on Medicare claims during 1998 or 1999, or if the women reported a history of breast cancer during their 2000 HRS interview. We also used claims data to exclude 287 women (6%) whose first mammogram during the study interval was performed for nonscreening purposes (e.g., bilateral or unilateral diagnostic mammogram or breast mass within 1 year prior to the index mammogram). Last, we excluded 249 women (6%) who were missing cognitive impairment information. This left a final screen-eligible cohort for analysis of 2131 women.

Primary Predictor

An overall cognitive score was calculated for each participant based on a 35-point cognitive instrument developed for HRS.21,22 The scale includes memory (20 points), calculation and attention (7 points), and orientation and naming questions (8 points). Memory was tested by asking the women to recall 10 nouns immediately and after a 5-minute delay, with 1 point per recalled word for a total of 20 points. Calculation and attention were assessed with the serial 7s test, in which participants start with 100 and consecutively subtract 7 five times, and by counting backward from 20 to 10 and 86 to 76. Orientation and naming included the following items: naming the month, day, year, day of the week; the object used to cut paper (scissors); the plant that lives in the desert (cactus); and the president and vice president of the United States. An overall score of 20 to 35 was considered normal cognitive function, 11 to 19 was defined as mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment, and a score of 10 or below was defined as severe cognitive impairment, based on prior work with this measure.23,24 In addition, 273 participants used a proxy informant to complete the HRS interview. For these participants, we defined severe cognitive impairment on the basis of the proxy's report that the respondent's memory or ability to make judgments and decisions was “fair or poor.” These definitions for severe cognitive impairment have been used to define dementia in prior studies that have used HRS data.25–27

Outcome Variables

Because self-report of mammography is unreliable in women with cognitive impairment, our primary outcome was receipt of screening mammography within the previous 2 years based on Medicare claims (Current Procedure Terminology28 code 76092; International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision [ICD-9]29 codes V76.11, V76.12; Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System30,31 codes G0202 G0203; or revenue center code32 403).33 To validate that our cognitive score identified women who had limited survival and would be unlikely to benefit from mammography, we calculated 4-year survival estimates and life expectancy estimates for age and cognitive status groups by using vital status information from the National Death Index.34

Covariates

We also assessed other factors known to influence the use of screening mammography, including demographic characteristics such as age, education, marital status, and total net worth. Total net worth was calculated as the sum of all assets and income, as this is a better indicator of socioeconomic status in the elderly compared with income alone. We categorized net worth into low (< $10 000), middle ($10 000–$100 000), and high (> $100 000) based on previous work.35 Race/ethnicity was assessed with standard questions derived from the US Census. We categorized individuals into the following 4 mutually exclusive groups: White (non-Hispanic White), African American (non-Hispanic African American), Hispanic (Latino), and persons of other race/ethnicity. Self-report of medical conditions included hypertension, diabetes, lung disease, psychiatric illness, arthritis, stroke, and heart disease.

We also assessed dependence in 6 instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) by calculating a summary score ranging from 0 to 6 points. One point each was given if a woman needed help from another person to perform the following: using a map, managing money, taking medications, grocery shopping, preparing hot meals, or using a telephone. Similarly, we assessed dependence in 5 basic activities of daily living (ADL) and calculated a summary score ranging from 0 to 5 points. One point each was given for needing help with the following: bathing, bed transfers, dressing, eating, or toileting.

Statistical Analysis

We summarized baseline characteristics for our cohort according to their cognitive status. We then calculated the rate of screening mammography according to cognitive status. We stratified the cohort on the basis of age, level of education, race/ethnicity, and net worth. To assess the effect of these covariates on the rates of screening mammography, we calculated logistic regression models with screening mammography as the outcome and cognitive status as the primary predictor. Adjustments to this logistic model were added, including demographics and comorbidity.

We then calculated 4-year survival in all screen-eligible respondents according to their cognitive status by using the method of Kaplan Meier. We also calculated survival for 5-year age and cognitive status groups. We calculated a Cox proportional hazard regression model of the survival estimates to estimate life expectancy for each of the age and cognitive status groups. For the severe cognitive impairment group, median life expectancy was reported from actual data, not from the model. We also determined screening mammography rates and mortality according to cognitive impairment and ADL dependence. For all analyses, we applied study weights to account for the complex study design and we used these weights to calculate population estimates of screening mammography use overall and in specific strata. We conducted all analyses with SAS version 9.1.3 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Characteristics of the 2131 women in our cohort are presented in Table 1. The median age was 77 years (interquartile range = 73–80 years). The majority of women were White and unmarried. Seventy-two percent of the sample had normal cognitive status, 29% had mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment, and 9% had severe cognitive impairment.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of US Women Aged 70 Years or Older, Health and Retirement Study, 2002

| Cognitive Statusa |

||||

| Characteristic | Normal Cognitive Status (n = 1167), % | Mild-to-Moderate Cognitive Impairment (n = 609), % | Severe Cognitive Impairment (n = 355), % | Total (N = 2131), % |

| Age, y | ||||

| 70–74 | 39 | 19 | 15 | 31 |

| 75–79 | 30 | 25 | 25 | 28 |

| 80–84 | 22 | 28 | 26 | 24 |

| ≥ 85 | 9 | 28 | 38 | 17 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 93 | 79 | 66 | 86 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 4 | 12 | 19 | 8 |

| Latino | 2 | 7 | 11 | 4 |

| Others | 1 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Education, > high school | 81 | 54 | 36 | 69 |

| Married | 38 | 25 | 24 | 33 |

| Total net worth, $ | ||||

| > 100 000 | 66 | 44 | 31 | 56 |

| 10 000–100 000 | 24 | 33 | 24 | 27 |

| < 10 000 | 10 | 24 | 45 | 17 |

| Comorbid illnesses | ||||

| High blood pressure | 61 | 61 | 63 | 61 |

| Diabetes | 14 | 19 | 20 | 16 |

| Lung disease | 9 | 8 | 8 | 9 |

| Any psychiatric illness | 12 | 15 | 28 | 15 |

| Arthritis | 72 | 71 | 72 | 72 |

| Stroke | 8 | 13 | 29 | 12 |

| Heart disease | 27 | 32 | 41 | 30 |

| IADL dependenceb | 21 | 39 | 79 | 32 |

| ADL dependencec | 4 | 11 | 51 | 11 |

Notes. ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = instrumental activities of daily living. Women with normal cognition were 62% of the total sample; women with mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment, 29%; women with severe cognitive impairment, 9%.

χ2 tests and t tests were used to compare the 3 cognitive status groups. All characteristics were different between women with normal cognitive status and those with cognitive impairment.

Needing help from another person to perform 1 or more of 6 IADL: using a map, managing money, taking medication, grocery shopping, preparing hot meals, and using the telephone.

Needing help from another person to perform 1 or more of 5 ADL: bathing or showering, getting in and out of bed, dressing, eating, and toileting.

Women with cognitive impairment were more likely to be older, non-White race/ethnicity (African American or Latino), had lower levels of formal education, and had lower net worth. Women with cognitive impairment also had higher levels of comorbid conditions (e.g., hypertension, any psychiatric illness, diabetes, stroke, and heart disease) and higher levels of functional impairment. For example, 51% of women with severe cognitive impairment were dependent in 1 or more ADL compared with 4% of women with normal cognitive status (P < .001).

Screening Mammography Rates

Overall, 39% of elderly US women had a screening mammogram within 2 years prior to their HRS interview based on Medicare claims. The proportion of elderly women who had a recent screening mammogram decreased with worsening cognitive status: 45% for women with normal cognitive status, 33% for women with mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment, and 18% for women with severe cognitive impairment. This is similar to the decrease in screening rates that occurs with advancing age. For example, 46% of women aged 70 to 74 years were screened; this percentage fell to 20% for women aged 85 years and older. Extrapolating these data to the US population, we estimated that 120 553 (95% confidence interval [CI] = 73 455, 167 651) elderly US women with severe cognitive impairment received screening mammography in 2002. Among women aged 85 years and older in the United States, 245 664 are estimated to have received screening mammography in 2002 (95% CI = 172 027, 319 301).

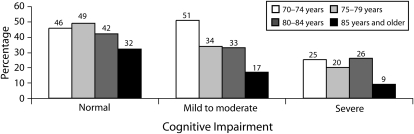

Older age was associated with lower rates of screening mammography, independent of cognitive status (Figure 1). For example, among women with normal cognitive status, 32% of women aged 85 years or older received screening compared with 46% of women aged 70 to 74 years who had normal cognitive status (for trend, P < .001). Similarly, among women with severe cognitive impairment, 9% of women aged 85 years or older received screening compared with 25% of women aged 70 to 74 years with severe impairment (for trend, P < .001).

FIGURE 1.

Screening mammography rates in older US women, by cognitive status and age: Health and Retirement Study, 2002.

Multivariate Analyses

In multivariate analyses, severe cognitive impairment remained 1 of the strongest predictors of not receiving a mammogram, after adjustment for all the variables in Table 1. Odds ratios (ORs) are presented in Table 2 and show that elderly women with severe cognitive impairment were 72% less likely to receive a screening mammogram compared with elderly women with normal cognitive status. Women with mild-to-moderate impairment were 40% less likely to receive a screening mammogram. These results were similar after adjustment. Similarly, advanced age (85 years or older) also decreased the likelihood of receiving a screening mammogram by approximately 70% compared with women aged 70 to 74 years. Comorbid conditions such as heart or lung disease or stroke were not associated with lower likelihood of screening after adjustment.

TABLE 2.

Rates of Screening Mammography, OR and AOR of Receiving a Screening Mammography Among US Women Aged 70 Years or Older, by Patient Characteristics: Health and Retirement Study, 2002

| Characteristic | No. | Screening Mammography Rate, % | ORa (95% CI) | AORb (95% CI) |

| Cognitive status | ||||

| Normal (Ref) | 1167 | 45 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Mild-to-moderate impairment | 609 | 33 | 0.60 (0.5, 0.8) | 0.82 (0.6, 1.1) |

| Severe impairment | 355 | 18 | 0.28 (0.2, 0.5) | 0.46 (0.3, 0.8) |

| Age, y | ||||

| 70–74 (Ref) | 629 | 46 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 75–79 | 512 | 43 | 0.89 (0.7, 1.1) | 0.95 (0.7, 1.2) |

| 80–84 | 490 | 38 | 0.70 (0.6, 0.9) | 0.82 (0.6, 1.0) |

| ≥ 85 | 500 | 20 | 0.30 (0.2, 0.4) | 0.42 (0.3, 0.6) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White (Ref) | 1721 | 41 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 257 | 30 | 0.6 (0.5, 0.9) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.3) |

| Latino | 117 | 23 | 0.4 (0.2, 0.8) | 0.7 (0.4, 1.2) |

| Education | ||||

| ≥ High school (Ref) | 1407 | 43 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| < High school | 724 | 30 | 0.6 (0.5, 0.8) | 0.9 (0.7, 1.1) |

| Net worth, $ | ||||

| > 100 000 (Ref) | 1117 | 46 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| 10 000–100 000 | 564 | 33 | 0.6 (0.5, 0.7) | 0.8 (0.6, 0.9) |

| < 10 000 | 450 | 24 | 0.4 (0.3, 0.5) | 0.7 (0.5, 0.9) |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 702 | 49 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| Not married | 1429 | 33 | 0.5 (0.4, 0.6) | 0.7 (0.5, 0.8) |

| Comorbiditiesc | ||||

| Heart disease | 663 | 39 | 0.91 (0.7, 1.1) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) |

| Diabetes | 344 | 39 | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) | 1.1 (0.9, 1.4) |

| Stroke | 300 | 29 | 0.59 (0.43, 0.8) | 0.8 (0.6, 1.1) |

| Lung disease | 193 | 37 | 0.91 (0.62, 1.3) | 0.9 (0.6, 1.4) |

Notes. AOR = adjusted odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; OR = odds ratio.

Calculated as univariate logistic regression with each characteristic separately.

Calculated by using multivariate logistic regression simultaneously adjusting for all characteristics together as listed.

Reference categories for each comorbidity is persons without that comorbidity.

Sociodemographic characteristics, such as higher net worth and being married, were associated with higher rates of screening even after adjustment (Table 2). Although White women were twice as likely to receive a screening mammogram compared with either Black or Latino women (OR = 2.3; 95% CI = 1.3, 4.1), race was not an independent predictor of screening in multivariate analyses. Women who were married and women with high net worth ($100 000 or more) were at 50% to 60% increased odds of having a screening mammogram (OR = 1.6; 95% CI = 1.2, 2.0; and OR = 1.5; 95% CI = 1.2, 1.9, respectively) independent of other factors, including cognitive status. Therefore, certain subgroups of women with cognitive impairment (e.g., White women with more than $100 000 net worth who were married) had high screening mammography rates (47%). ADL dependence was also associated with lower screening mammography rate for each level of cognitive impairment. Specifically, women with severe cognitive impairment and ADL dependence are much less likely to be screened (only 5%; Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Screening Mammography Rate and 4-Year Mortality Rate Among US Women Aged 70 Years or Older, by Cognitive Status and Dependence in ADL: Health and Retirement Study, 2002

| Cognitive Status | Screening Mammography Rate, % | 4-Year Mortality Rate, % |

| Independent in ADL | ||

| Normal cognitive status | 45 | 12 |

| Mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment | 33 | 19 |

| Severe cognitive impairment | 26 | 28 |

| Dependent in ADL | ||

| Normal cognitive status | 35 | 38 |

| Mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment | 20 | 54 |

| Severe cognitive impairment | 5 | 66 |

Note. ADL = activities of daily living.

Four-Year Survival and Average Life Expectancy

Worsening cognitive impairment was significantly associated with worsening survival: 15% of women with normal cognitive status died during 4 years of follow up, as did 26% of women with mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment and 59% of women with severe cognitive impairment. Overall, women with severe cognitive impairment had shorter average survival and shorter life expectancies compared with women with mild-to-moderate cognitive impairment and normal cognitive status (log-rank test P < .001; Figure 2 and Appendix 1, available as a supplement to the online version of this article at http://www.ajph.org). The life expectancy for women with severe cognitive impairment was substantially less than the survival for women aged 85 years or older with normal cognition (6.7 years; 95% CI = 6.3, 7.1). ADL dependence was also associated with lower survival. Specifically, women with severe cognitive impairment and ADL dependence have a much higher 4-year mortality rate (66%; Table 3).

FIGURE 2.

Four-year survival estimates for US women aged 70 years and older, by cognitive status: Health and Retirement Study, 2002.

DISCUSSION

This is the first US population–based study to determine actual rates of screening mammography in older women across levels of cognitive impairment. We found that women with severe cognitive impairment had much lower screening mammography rates than women with normal cognition (18% versus 45%). However, there were several sociodemographic characteristics that increased screening rates independent of cognition, such as being married or having high net worth. This resulted in some subgroups of women with cognitive impairment having screening rates approaching 50%. This is despite the fact that women with severe cognitive impairment have a median survival of 3.3 years, which indicates that they are unlikely to benefit from screening mammography.

Prior studies have suggested that health status and comorbidity are not strong predictors of screening mammography use.5 For example, in a study of California women, screening mammography rates decreased with advancing age; however, within each age group, the percentage of women reporting screening did not significantly decrease with worsening health status. In contrast, our results suggest that severe cognitive impairment is associated with a substantial decrease in screening mammography rates, similar in magnitude to the reductions seen with very advanced age (85 years or older). One possible explanation is that physicians appropriately recognize that harms of screening likely outweigh the low potential benefit for women with cognitive impairment. Another possibility is that elderly women with severe cognitive impairment or their caregivers may be refusing screening mammography to avoid the potential harms and distraction from care.

Prior studies have suggested that screening mammography can cause harm in frail elderly women. For example, 1 study of elderly nursing home–eligible women found that 17% experienced harm from screening mammography, including false-positive results and identification and treatment of clinically insignificant cancer.13 Treatment of inconsequential disease may include the ill effects of surgery, radiation or chemotherapy and their side effects, or psychological harms related to the treatment. Last, time spent getting a screening mammogram and follow-up from the mammogram may distract from the care of a woman's most pressing medical problems arising from the cognitive impairment itself (e.g., management of depression and behavioral issues) or from her other medical comorbidities.

Although our results show lower screening rates in women with cognitive impairment, we identified several subgroups of elderly women with cognitive impairment who had substantial rates of screening mammography. For example, for certain subgroups of women with cognitive impairment—those who were married and had high net worth—screening rates approached 50%. The impact of net worth on screening rates has been shown previously.35 These high screening rates are seen despite the fact that women with severe cognitive impairment have a median survival of 3.3 years, which suggests that the harms of screening are likely to outweigh the benefits.13 In fact, all women with severe cognitive impairment who are aged older than 70 years have limited life expectancies. Therefore, although cognitive impairment is harder to identify than age, it provides important guidance to clinicians about which patients not to screen, particularly at younger-old ages (70–84 years) or for subgroups of women who are more likely to be screened.

To help clinicians with these decisions, guidelines should be more explicit about stopping screening in older women with severe cognitive impairment rather than basing the decision on age alone. Although our study did document lower screening mammography rates in women with severe cognitive impairment, one could argue that even these lower rates in women with severe cognitive impairment are too high. Ultimately, the decision to screen should be mutually decided by the patient, her family members, and her physician, in the context of an informed discussion.

A strength of our study over prior studies of screening mammography in women with cognitive impairment is that screening mammography rates were based on Medicare claims and did not rely on self-report. Our screening rates of 18% in women with severe cognitive impairment and 33% in women with mild-to-moderate impairment were substantially lower than previously reported mammography rates given by self-report.15,16 In a study by Legg et al.,16 44% of women with cognitive impairment reported having a mammogram compared with 55% in women without, and in another study by Ostbye et al.,15 self-reported screening ranged from 48% in women with cognitive impairment compared with 64% in women without cognitive impairment. Self-report is particularly unreliable in patients with cognitive impairment. A small proportion of the respondents were evaluated through a proxy informant. We incorporated the evaluation of cognition based on these proxy informants for respondents who cannot themselves answer. It is very important to include proxy informants in studies of the elderly, particularly when the respondents have some level of cognitive impairment, as use of proxy informants has been shown to decrease health-related nonresponse in surveys of frail older adults.36

Our study had some potential limitations. First, we used a 35-point screen of cognitive impairment that was developed for the HRS. This screening test is not commonly used by clinicians but has some overlap with commonly used instruments like the Mini-Mental State Exam. Second, our evaluation of cognitive impairment was not equivalent to a clinical diagnosis of dementia. However, it is likely that our definition of severe cognitive impairment has a good deal of overlap with dementia, as it has been used to screen for dementia in other studies27 and has evidence of construct validity.21,22 In addition, women in our study classified with severe cognitive impairment had a high degree of ADL impairment and had a life expectancy of 3.3 years, which makes them unlikely to benefit from mammography regardless of whether a formal clinical diagnosis of dementia was given.

Third, there is possibly a limitation in our time of origin for the life expectancy and survival calculations. These were taken from the HRS 2002 interview date, not at the date of mammography screening. Thus, for all groups, the life expectancy at the date of mammography could be an average of 1 year longer than those reported. A conservative interpretation would suggest that women who are aged 70 to 74 years with severe cognitive impairment may have a life expectancy bordering 5 years that might allow some potential to benefit from mammography, but this would have to be weighed against the increased potential harms. Last, consistent with other claims-based studies, we could not assess screening mammography use among women who were enrolled in a Medicare health maintenance organization.37

In summary, this population-based study of older US women suggests that women with severe cognitive impairment have much lower screening mammography rates than women with normal cognition, and this is appropriate because of their very limited life expectancy. Guidelines could help clinicians and patients with the often complex decisions about when to stop screening by explicitly stating which comorbidities make it likely that screening will cause net harm. Because of the limited life expectancies of persons with severe cognitive impairment and the known harms of screening this population, clinical guidelines should recommend against screening mammography in women with severe cognitive impairment so that time spent in the clinical encounter can be better spent on preventive services that are more likely to improve their quality of life and their ability to stay in their homes.

Acknowledgments

K. M. Mehta is currently supported by a Research Career Scientist Award from the National Institute on Aging (NIA-K-01AG025444-01A1). She is currently an affiliate of the Center for Aging in Diverse Communities at University of California, San Francisco, a part of the P30 AG 15272 350 Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research Program (NIA, National Institute of Nursing Research, and the National Center for Minority Health and Health Disparities). L. C. Walter was supported by a Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review grant (IIR 04-427) and is a Robert Wood Johnson Physician Faculty Scholar. The Health and Retirement Study is sponsored by the NIA (grant NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan.

We wish to thank Priya Kamat and Michele Casadei for their help in acquiring the Medicare data.

Note. The funding organizations and sponsors had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the article.

Human Participant Protection

The University of California, San Francisco, and San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center institutional review board approved the study.

References

- 1.American Geriatrics Society Ethics Committee Health screening decisions for older adults: AGS position paper. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(2):270–271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smith RA, Saslow D, Sawyer KA, et al. American Cancer Society guidelines for breast cancer screening: update 2003. CA Cancer J Clin. 2003;53(3):141–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Humphrey LL, Helfand M, Chan BK, Woolf SH. Breast cancer screening: a summary of the evidence for the US Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(5 pt 1):347–360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.US Preventive Services Task Force Screening for prostate cancer: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2008;149(3):185–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Walter LC, Lindquist K, Covinsky KE. Relationship between health status and use of screening mammography and Papanicolaou smears among women older than 70 years of age. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(9):681–688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Larson EB, Shadlen MF, Wang L, et al. Survival after initial diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(7):501–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walsh JS, Welch HG, Larson EB. Survival of outpatients with Alzheimer-type dementia. Ann Intern Med. 1990;113(6):429–434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beard CM, Kokmen E, O'Brien PC, Kurland LT. Are patients with Alzheimer's disease surviving longer in recent years? Neurology. 1994;44(10):1869–1871 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Molsa PK, Marttila RJ, Rinne UK. Long-term survival and predictors of mortality in Alzheimer's disease and multi-infarct dementia. Acta Neurol Scand. 1995;91(3):159–164 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heyman A, Peterson B, Fillenbaum G, Pieper C. The consortium to establish a registry for Alzheimer's disease (CERAD). Part XIV: demographic and clinical predictors of survival in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1996;46(3):656–660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brookmeyer R, Corrada MM, Curriero FC, Kawas C. Survival following a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2002;59(11):1764–1767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Waring SC, Doody RS, Pavlik VN, Massman PJ, Chan W. Survival among patients with dementia from a large multi-ethnic population. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2005;19(4):178–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walter LC, Eng C, Covinsky KE. Screening mammography for frail older women: what are the burdens? J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(11):779–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raik BL, Miller FG, Fins JJ. Screening and cognitive impairment: ethics of forgoing mammography in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(3):440–444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ostbye T, Greenberg GN, Taylor DH, Jr, Lee AM. Screening mammography and Pap tests among older American women 1996–2000: results from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS) and Asset and Health Dynamics Among the Oldest Old (AHEAD). Ann Fam Med. 2003;1(4):209–217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Legg JS, Clement DG, White KR. Are women with self-reported cognitive limitations at risk for underutilization of mammography? J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2004;15(4):688–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heflin MT, Oddone EZ, Pieper CF, Burchett BM, Cohen HJ. The effect of comorbid illness on receipt of cancer screening by older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(10):1651–1658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ives DG, Lave JR, Traven ND, Schulz R, Kuller LH. Mammography and pap smear use by older rural women. Public Health Rep. 1996;111(3):244–250 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Heeringa S, Connor J. Technical Description of the Health and Retirement Study Sample Design. Documentation Report. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 1995 [Google Scholar]

- 20.The Health and Retirement Study Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; Available at: http://hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/sampleresponse.pdf. Accessed April 1, 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ofstedal MB, McAuley GF, Herzog AR. Documentation of Cognitive Functioning Measures in the Health and Retirement Study. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, University of Michigan; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Herzog AR, Rodgers WL. Cognitive performance measures in survey research on older adults. In: Schwarz N, Park DC, Knauper B, Sudman S, eds. Cognition, Aging and Self-Reports. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mehta KM, Yaffe K, Covinsky KE. Cognitive impairment, depressive symptoms, and functional decline in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(6):1045–1050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mehta KM, Yaffe K, Langa KM, Sands L, Whooley MA, Covinsky KE. Additive effects of cognitive function and depressive symptoms on mortality in elderly community-living adults. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(5):M461–M467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Langa KM, Chernew ME, Kabeto MU, et al. National estimates of the quantity and cost of informal caregiving for the elderly with dementia. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(11):770–778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Langa KM, Larson EB, Karlawish JH, et al. Trends in the prevalence and mortality of cognitive impairment in the United States: is there evidence of a compression of cognitive morbidity? Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4(2):134–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Langa KM, Plassman BL, Wallace RB, et al. The Aging, Demographics, and Memory Study: study design and methods. Neuroepidemiology. 2005;25(4):181–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Current Procedural Terminology: CPT 2002. 4th ed Chicago, IL: American Medical Association; 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 29.International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1980 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Health Care Financing Administration HCFA common procedure coding system (HCPCS): national level II Medicare codes. Los Angeles, CA: Practice Management Information Corporation; 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alpha-numeric HCPCS [Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Web site] Available at: http://www.cms.hhs.gov/HCPCSReleaseCodeSets/ANHCPCS/list.asp#TopOfPage. Accessed December 17, 2009.

- 32.HCFA Data Dictionary: Revenue Center Codes. Baltimore, MD: Health Care Financing Administration; 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Randolph WM, Mahnken JD, Goodwin JS, Freeman JL. Using Medicare data to estimate prevalence of breast cancer screening in older women: comparison of different methods to identify screening mammograms. Health Serv Res. 2002;37(6):1643–1657 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.National Death Index [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site] Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ndi.htm. Accessed December 17, 2009.

- 35.Williams BA, Lindquist K, Sudore RL, Covinsky KE, Walter LC. Screening mammography in older women. Effect of wealth and prognosis. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(5):514–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Corder LS, Woodbury MA, Manton KG. Proxy response patterns among the aged: effects on estimates of health status and medical care utilization from the 1982–1984 long-term care surveys. J Clin Epidemiol. 1996;49(2):173–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Robinson K. Trends in Health Status and Health Care Among Older Women. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2007. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/agingtrends/07olderwomen.pdf. Accessed December 16, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]