Abstract

Certified nursing assistants (CNAs) are the principal bedside caregivers in nursing homes, yet little is known about their perceptions of the work environment. This population-based, cross-sectional study used a mailed questionnaire to a random sample of Iowa CNAs (N = 584), representing 166 nursing homes. Of the respondents, 88.5% (n = 517) were currently employed in long-term care settings; however, 11.5% (n = 67) indicated they had left their jobs. When CNA responses were compared with those of other occupational groups, general workers reported higher scores on involvement, coworker cohesion, work pressure, and supervisor support. Those who left their CNA jobs rated their work environment as characteristic of excessive managerial control and task orientation. Results of this study emphasize the importance of the relationship between CNAs and their supervisors, CNAs’ need for greater autonomy and innovation, and the need for the work environment to change dramatically in the area of human resource management.

Despite the evolving popularity of home-based and community-based services, nursing homes will always be needed. One of the greatest challenges facing the long-term care (LTC) industry is maintaining an adequate workforce (Fitzpatrick, 2002). Although many have written about the larger problem of a nursing shortage (Janiszewski Goodin, 2003; Rondeau & Wagar, 2006; Seago, Spetz, Chapman, & Dyer, 2006; Selvam, 2001), few have asked certified nursing assistants (CNAs) in LTC settings to evaluate their work environment. Because there is a critical shortfall of direct care workers in Iowa and many other states in which the aging population continues to increase (Fowler, 2003; Iowa Department of Public Health, 2005), we asked both currently employed CNAs and those who had quit their CNA jobs to rate their work environment. We then compared their responses with normative samples from other occupational groups.

BACKGROUND

The deficit in the LTC labor workforce is not a looming crisis nor will it self-correct. Indeed, the current shortfall will only be aggravated by the increased life expectancy of Americans (Guttman, 2000), the increased prevalence of dementia and other chronic illnesses (Ravaglia et al., 2007), and the high social costs of an underinsured public (Stuart et al., 2005). Annual turnover rates for CNAs vary widely, ranging from 32% to 179% (Castle & Lowe, 2005; Kash, Castle, Naufal, & Hawes, 2006), and compelling evidence suggests that turnover rates are negatively associated with a number of quality outcomes in LTC (Anderson, Issel, & McDaniel, 2003; Harrington, Swan, & Carrillo, 2007). Many nursing homes already face a shortage of personnel and have attempted to fill vacancies with immigrant workers (Priester & Reinardy, 2003; Reed & Andes, 2001).

The workforce problem is muddled by lack of a standardized formula to calculate nursing home staff turnover, failure of nursing home administrators to determine the actual cost of replacing a CNA employee, lack of federally mandated CNA staffing requirements on all three work shifts, and the poor reimbursement rate for Medicaid residents in LTC facilities (Johnson, 2005). In Iowa, this has led to the development of large nursing home conglomerates, an increase in the number of beds in urban settings, and an increased incidence of resident abuse investigations (Jogerst, Daly, Dawson, Peek-Asa, & Schmuch, 2006; Weech-Maldonado, Shea, & Mor, 2006).

Although job satisfaction (Liu, 2007; Moyle, Skinner, Rowe, & Gork, 2003; Rondeau & Wagar, 2006), workplace stress (Lapane & Hughes, 2007), and poor salaries (Moore, 1999) have been examined among CNAs, this study was conducted to explore how CNAs rated their work environment and to compare ratings between currently employed CNAs and those who had left their CNA jobs. CNA perceptions of the work environment are important so health care planners can improve retention of these essential direct care workers. The specific research questions addressed in this study were:

How do currently employed CNAs rate their work environment, and how do their ratings compare with those of other worker groups?

How do individuals who have left their CNA jobs rate their prior work environment, compared with those who continue to work in LTC?

LITERATURE REVIEW

Several studies have examined the CNA workforce in LTC in relation to staff burnout, the effects of work assignments, staffing patterns, job enrichment, and personal growth opportunities (Burgio, Fisher, Fairchild, Scilley, & Hardin, 2004; Harrington & Swan, 2003; Parsons, Simmons, Penn, & Furlough, 2003; Secrest, Iorio, & Martz, 2005), but few have focused on the actual perceptions of CNAs regarding their work environment. The role of perceptions of the work environment in CNA turnover is unknown because few nursing homes, including those in Iowa, conduct exit interviews with terminating CNAs. We found only one study in which exit interviews were used (Gaddy & Bechtel, 1995), and the findings were mixed; 39.6% of the employees leaving the facility stated positive personal relationships were a strength of the organization, and 24.3% resigned because of personal or staff conflicts.

The largest and most visible research initiative in the area of CNAs in LTC is the National Nursing Assistant Survey (NNAS), the first national probability sample survey of CNAs employed in nursing homes (Squillace, Remsburg, Bercovitz, Rosenoff, & Branden, 2007). For the 2004 NNAS, 1,500 nursing facilities were selected from a sampling frame of approximately 17,000 nursing homes in the United States. The sampling frame for the NNAS was drawn from two sources, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) and state licensing lists compiled by a private organization. The combined files were matched and unduplicated, resulting in a final sampling frame of 16,628 nursing homes. Although preliminary manuscripts will be forthcoming in the next few years, there is a strong indication from the 2,897 CNA participants that supervisor behavior is critically important in staff turnover. Specifically, CNAs expressed the opinion that their supervisors could improve on helping with direct care tasks when needed, taking a more active role in addressing CNA concerns, and being more supportive of a career development program.

The literature identifies many issues related to why CNAs leave their positions. The most common are low wages, lack of benefits, frequently changing patient assignments, and the unexpected absence of a coworker (Grieshaber, Parker, & Deering, 1995; Moyle et al., 2003). Environmental interventions have been introduced for CNAs in an effort to improve their job satisfaction (Muntaner et al., 2006). There is some indication that quality management practices, such as receiving adequate training, fostering collaboration, and reducing documentation requirements that interfere with care, are factors in promoting employee retention and improving the psychological well-being of nursing home employees (Kash et al., 2006). Organizational-level factors such as seniority wage increases and reduced managerial pressure did not reduce work emotional strain among CNAs in the Muntaner et al. (2006) study.

Staff turnover in nursing homes is generally a significant issue, yet no consistent measures of staff turnover have been established. In a meta-analysis of published studies, Bostick, Rantz, Flesner, and Riggs (2006) found that CNA turnover rates ranged from 68.5% to 170.5%; in another study, the turnover rate was reported as high as 400% (Berg-Weger, Rauch, Rubio, & Tebb, 2003). Indeed, some nursing homes do not have sufficient nursing personnel on all three shifts, which could adversely affect CNAs’ ratings of their work environment.

The number of actively working CNAs in Iowa has steadily declined from 31,000 in 1999 to less than 29,000 in 2005 (Iowa Department of Public Health, 2005). This comes at a time when Iowa needs more LTC workers than ever, as 22% of the state’s total population is older than age 60 (National Clearinghouse on the Direct Care Work-force, 2004). Iowa is also one of the leading states in the proportion of people age 85 and older, and the numbers of those in this “old-old” cohort increased by 18% from 1990 to 2000 (U.S. Census Bureau, 2001). In Iowa, 6% of adults older than age 65 reside in nursing homes; this is higher than the national average of 3.6% (Jones, 2002).

METHOD

This population-based, cross-sectional study used a mailed questionnaire. The questionnaire was reviewed by undergraduate nursing students who worked as CNAs and by a panel of three doctorally prepared gerontological nurse researchers familiar with the LTC work environment. Both the length of the questionnaire and the wording of individual items were modified based on feedback from these two groups. The protocols for this study were approved by the University’s Institutional Review Board for Human Subjects.

Data Analysis

To answer the two research questions, descriptive statistics were used, including the mean, standard deviation (SD), frequencies, and percentages. Independent t tests were used to compare means, and Levine’s test for unequal variances was used where appropriate. Pearson’s chi squares were used for nominal data, and a Fisher’s exact test was used when cell size was n < 6.

Setting

CNAs were enrolled in a Direct Care Worker Registry (DCWR) maintained by the Department of Inspection and Appeals in the State of Iowa. Enrollment in the registry is a requirement for continued certification, and CNAs are required to register every 2 years and to be actively employed within a 6-month period to be eligible for recertification.

Sample

A random sample (N = 2,203) of CNAs was compiled; the only criteria used in the database query was employment in LTC at the last time point of registration with the DCWR. ZIP codes of this search were cautiously observed to ensure wide geographical representation across Iowa.

Completed questionnaires were received from 643 CNAs after a second mailing, representing a 29.2% response rate. We determined that of those 643 respondents, 9.2% (n = 59) did not work in LTC, and these cases were subsequently excluded from analysis. Of the remaining 584 respondents, 88.5% (n = 517) were currently employed in the nursing home industry, and 11.5% (n = 67) had recently quit their CNA jobs. Thus, study participation was from CNAs working in 166 of Iowa’s 245 nursing homes. The majority of respondents were women (97.1%), and the racial groups represented were Caucasian (88%), Native American (7.7%), African American (1%), and Other (3.3%).

Characteristics of Nonresponders

Because it is likely that those not employed as CNAs failed to respond to the questionnaire, we analyzed non-responders as well. For nonresponders, the mean number of years they had been working as CNAs was 13.9 (SD = 7.8). It is possible that a number of people who no longer worked as CNAs may have simply discarded the questionnaire, although the cover letter clearly stated we were interested in their participation. Facilities in which non-responders were employed were slightly larger than those of responders (mean = 111 beds, SD = 146). Mean CNA hours per resident day among nonresponders was similar to that of responders at 2.3 hours (SD = 0.5).

Instruments

The Work Environment Scale (WES) Form R is a 90-item questionnaire with three dimensions (Moos, 1994b). The WES measures workers’ perceptions of their current work environment in the areas of relationships (involvement, coworker cohesion, and supervisor support), personal growth (autonomy, task orientation, and work pressure), and systems maintenance (clarity, managerial control, innovation, and physical comfort). The conceptual and psychometric issues involved in construction of the WES have been described previously (Moos, 1994a), and the scale has been used in studies of nurses’ perceptions of their work environment (Avallone & Gibbon, 1998; Mc-Crae, Prior, Silverman, & Banerjee, 2007). Internal consistencies within the subscales range from 0.69 (coworker cohesion) to 0.84 (involvement).

The WES score ranges from 0 to 9 for each subscale, with higher scores indicating greater weight that the respondent applies to his or her work setting. Studies using the WES have been reported in the psychology literature for more than 15 years, and normative samples of both general workers and health care workers exist (Vagg & Spielberger, 1998). Population-based normative scores from other worker groups also exist for the scale and were used for comparison with the results from our CNA sample.

The nursing home report card database published by the CMS as the “Nursing Home Compare” provided data on variables such as the number of beds, number of staff hours per resident day, and information about deficiencies and complaints for a facility receiving Medicare or Medicaid funding. The validity and reliability of these data are discussed elsewhere (Castle & Lowe, 2005; Wardell, 2003), but worth noting is the issue of overreporting of staff hours (Harrington, 2005). It is also probable that facilities with a high proportion of Medicare residents have better staffing ratios than those with more Medicaid residents because the reimbursement rate to nursing homes from Medicare is greater (Harrington & Swan, 2003).

RESULTS

Currently Employed CNAs

The mean age for currently employed CNAs was 51 (SD = 12.2 years); 41 (8.1%) CNAs reported having two or more employers in the past 12 months (Table 1). Responses to items related to socioeconomic stability were troubling. Specifically, many CNAs indicated they could not afford health insurance premiums (67.1%) and that their salary was too low (93.6%). For those currently employed CNAs, 21.7% indicated it was the only job they could obtain (Table 2). Among currently employed CNAs, 15.6% (n = 80) had to supplement their earnings with a non-CNA job.

TABLE 1.

Demographic and Household characteristics of respondents

| Variable | Quit Job as CNA (n = 67)

|

Current CNA (n = 517)

|

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | ||

| Current age (years) | 52.1 (14.1) | 51 (12.2) | ns |

| Age started working as CNA (years) | 29.2 (12.9) | 29 (11.7) | ns |

| Years of education | 12.5 (2.4) | 12.2 (1.5) | ns |

|

| |||

| n (%) | n (%) | p Value | |

|

| |||

| Two or more employed adults in household | 30 (44.8) | 315 (60.9) | <0.01 |

| Love(d) job as a CNA | 57 (85.1) | 487 (94.2) | <0.01 |

| Children younger than age 18 living in household | 19 (28.4) | 165 (31.9) | ns |

| Two or more employers in the past 12 months | 7 (10.5) | 41 (7.9) | <0.05 |

Note. CNA = certified nursing assistant; ns = not significant.

TABLE 2.

Perceptions of socioeconomic stability Among cNAs

| Perception | Quit Job as CNA (n = 67)

|

Current CNA (n = 517)

|

p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| I think the salary for CNAs is too low. | 58 (86.6) | 480 (92.8) | ns |

| My employer does/did not pay anything into a retirement account. | 23 (34.3) | 168 (32.5) | ns |

| I don’t want a retirement account right now. | 10 (14.9) | 105 (20.3) | ns |

| I cannot/could not afford health insurance premiums. | 42 (62.7) | 336 (64.9) | ns |

| I would take food stamps if I needed them. | 29 (43.3) | 270 (52.2) | ns |

| I had to take this job, it was the only one I could get. | 5 (7.5) | 112 (21.7) | <0.01 |

Note. CNA = certified nursing assistant; ns = not significant.

CNAs Who Quit Their Jobs

CNAs who had left their jobs (n = 67, 11.5%) had some unique characteristics as a group. These participants were more likely than those who were currently employed as CNAs to have had two or more employers in the 12 months prior to the survey (p < 0.05). When asked who had initiated termination, a minority (n = 9, 13.4%) of CNAs who had left their jobs indicated that their employer had initiated the job separation.

The CNAs used Likert scales (1 = the main reason for leaving to 5 = the least important reason for leaving) to describe why they had left their job. Among those who left their jobs voluntarily, the top three reasons were poor relationship with supervisor or coworkers (mean = 1.26, SD = 1.36), low salary (mean = 2.57, SD = 1.19), and family obligations (mean = 3.08, SD = 1.47). Other reasons for leaving included scheduling conflicts (mean = 3.11, SD = 1.37) and poor care provided to residents (mean = 4.08, SD = 1.41).

The general physical care provided to residents was a concern of CNAs who had left their jobs. One of their concerns was they “couldn’t find someone to help them when a resident fell” (19.4%, n = 13), but this response was not very different from that of currently employed CNAs (n = 70, 13.5%). CNAs who had quit their job reported that the nurses seldom helped (32.8%, n = 22), which was higher than that reported by the currently employed group (33.3%, n = 172). Among CNAs who had left their jobs, 31.3% (n = 21) indicated that their input was not used in planning patient care, whereas a higher percentage of currently employed CNAs (44.3%, n = 229) indicated the same thing.

Both facility characteristics and household composition were considered in describing the CNAs who reported they were not working in LTC. CNAs who had left their jobs tended to leave smaller facilities (mean = 66 skilled beds, SD = 35.7), compared with currently employed CNAs (mean = 87 skilled beds, SD = 98.2; p < 0.01). Those who had left their jobs were employed for a slightly shorter time period (mean = 14.3 years, SD = 8.5) than were currently employed CNAs (mean = 15.3 years, SD = 7.9).

Physical Aspects of the Work Environment

In terms of general physical comfort and safety in the work environment, ratings were similar between the currently employed CNAs and those who had left their job. For example, no differences were found between the two groups related to missing meal breaks. Respondents were also asked about physical harm caused by residents, and again, no differences were found in the percentages of currently employed CNAs who reported being bitten (28%, n = 145), compared with the CNAs who had quit (26.9%, n = 18). However, there were more reports of sexual touching by residents during the past year among those currently employed (44.3%, n = 229,) than among those not employed (31.3%, n = 21; p < 0.05).

No statistically significant differences were found in the number of CNA hours per resident day in facilities where CNAs had left their jobs (mean = 2.2 hours, SD = 0.5) and those where CNAs remained employed (mean = 2.2, SD = 0.5). Nor were any differences found between the two groups regarding the number of RN or licensed practical nurse (LPN) hours per resident day. In terms of external inspections by state authorities, slightly higher numbers of facility minimal-harm citations were reported among the currently employed CNAs (mean = 13.1, SD = 10.5) than among the CNAs who had left their jobs (mean = 10.6, SD = 8.4; p = 0.05). The number of citations indicating actual harm to residents was not significantly different among the two groups.

Social Aspects of the Work Environment

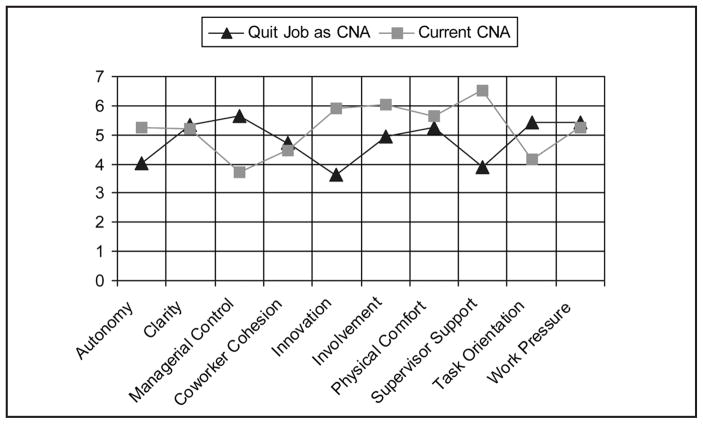

The mean scores for the WES subscales, stratified by employment status, are displayed in the Figure. Currently employed CNAs rated their work environment higher in the areas of autonomy, innovation, involvement, and supervisor support than did those who had left their jobs, although these differences were not statistically significant. Respondents who quit their CNA jobs rated their work environment as characteristic of excessive managerial control and task orientation. Surprisingly, several ratings were similar between the two groups, including ratings for clarity (of work assignment), coworker cohesion, physical comfort, and work pressure.

Figure.

Work environment subscale scores by employment status.

CNA = certified nursing assistant.

Comparisons with Other Worker Groups

Scores on the WES for currently employed CNAs were compared with other worker groups; the results are shown in Table 3. Health care workers, with the exception of one CNA sample from the United Kingdom (UK), were grouped into one category. Scores of general workers (both white collar and blue collar employees) were reported by Moos (1994a) and thus formed a normative or reference group. The CNAs in our sample who had quit their jobs were excluded from this analysis, as there was no comparative group of terminated employees in Moos’ datasets.

TABLE 3.

comparison of Work environment scalea Scores of currently employed cNAs with Normative samples

| Variable | Currently Employed CNAs in LTC in Iowa (n = 517)

|

Currently Employed CNAs in the United Kingdomb (N = 83)

|

Health Care Workersc (N = 4,876)

|

General Workersc (N = 3,267)

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Involvement | 5.3 (2.4) | 5.5 (2.3) | 5.4 (2.3) | 6.1 (2.1) |

| Coworker cohesion | 5.2 (1) | 3.6 (2.3) | 5.2 (2) | 6 (1.81) |

| Supervisor support | 3.7 (2) | 4 (2.3) | 4.8 (2.2) | 5.7 (2) |

| Autonomy | 4.5 (1.8) | 4.6 (1.8) | 5.2 (2) | 5.9 (1.8) |

| Task orientation | 5.9 (2.4) | 6.3 (1.8) | 5.7 (2) | 6.1 (1.9) |

| Work pressure | 6 (2.2) | 5.2 (2) | 5.7 (2.2) | 4.8 (2.1) |

| Clarity | 5.7 (2.3) | 4.6 (1.8) | 4.5 (2) | 5.5 (1.9) |

| Managerial control | 6.5 (1.9) | 6.3 (1.7) | 5.6 (1.9) | 4.8 (1.9) |

| Innovation | 4.1 (2.3) | 3.3 (2.3) | 3.9 (2.3) | 4.4 (2.3) |

| Physical comfort | 5.3 (2.4) | 4.5 (2.2) | 3.8 (2.1) | 4.9 (2.2) |

Note. CNA = certified nursing assistant; LTC = long-term care.

Higher scores on the Work Environment Scale indicate more of the attribute or workplace rating.

CNAs in Iowa rated their jobs higher in the areas of work pressure, managerial control, and physical comfort than did the other groups, but lower than did general workers on the subscales of involvement, coworker cohesion, and supervisor support. We found one other CNA study recently conducted in the UK that used the WES (McCrae et al., 2007) and added those outcomes to Table 3. The Iowa CNAs rated coworker cohesion, work pressure, clarity, managerial control, innovation, and physical comfort higher than did CNAs in the UK study.

DISCUSSION

The analysis reported in this article adds to what is known about the loss of LTC workers from the workforce in that we surveyed not only CNAs who intended to leave but also those who had actually left their jobs. In addition, a unique aspect of this work is the use of a standardized instrument that measured perceptions of the work environment that could be readily compared with other worker groups, including those outside health care settings. Job satisfaction instruments tend to be overused in studies of staff turnover (Caudill & Patrick, 1991; Grieshaber et al., 1995; Liu, 2007). This approach of workers’ rating the work environment is more accurate than simply measuring satisfaction.

Work Environment Ratings

The results emphasize the importance of the relationship between CNAs and RNs. RNs rate the WES subscales of coworker cohesion, supervisor support, autonomy, and innovation more positively than do CNAs, after controlling for kind of setting (McCrae et al., 2007). The McCrae research team noted that RNs consistently rated their work environment more positively than did CNAs, especially on the subscale of innovation.

CNAs in this Iowa sample perceived constraints in their work environment related to initiating interventions, as demonstrated by their lower ratings of autonomy and innovation. We believe this struggle for autonomy is frustrating for them; this was reflected in the WES subscale scores and the notion that CNAs are more compelled to use the tried-and-tested care strategies they were taught in their basic nursing assistant course and not act on their intuition and creativity in solving patient care problems.

General workers reported higher WES scores on the subscales of involvement, coworker cohesion, work pressure, and supervisor support than did participants in our study. Possible explanations for this are that the CNA work-force is gender skewed and that CNA work is a human-oriented service geared toward care of frail older adults and not toward manufacturing or production-type jobs.

In terms of international comparisons, McCrae et al.’s (2007) study (N = 83) analyzed responses on the WES from CNAs in the UK. In that study, CNAs were employed by hospitals and community centers for elder mental health services, rather than in nursing homes, but there are notable similarities between the two groups, as exemplified by the autonomy subscale scores. However, the UK CNAs indicated lower scores for both work pressure (mean = 5.2, SD = 2) and coworker cohesion (mean = 3.6, SD = 2.3) than did the Iowa CNAs. The lower work pressure finding among UK CNAs is likely due to the community-based care provided by UK CNAs, as opposed to institution-based care, with more physical care requirements, provided by Iowa CNAs.

CNAs Who Quit Their Jobs

Most CNAs indicated they had initiated their termination (86.6%, n = 58); only 9 (13.4%) indicated their employer had terminated their employment. Specifically, those who had left their jobs reported decreased ratings on the autonomy subscale, suggesting they may have perceived excessive supervision. It is possible that some of the individuals who quit had exhibited performance problems prior to their termination, but we do not have data to confirm this. More research describing the loss of direct care workers, specifically related to CNA job termination and employee discipline, is needed.

Perhaps the most remarkable finding from this study was that 85.1% of those who had quit their jobs had “loved” working as a CNA. Thus, it is difficult to understand why these individuals left their positions. Participants who left their CNA jobs rated problems with supervisors and coworkers as more important than a need for higher pay, although salaries remain an important issue in the LTC industry. This study was limited by not describing why CNAs actually quit their jobs, so we recommend that targeted exit interviews be conducted by human resource personnel in facilities with high staff turnover to more precisely determine reasons for leaving.

State-wide datasets have been used to explore attitudes among CNAs who quit their jobs in the nursing home industry. For example, in Louisiana (N = 550), 60% of CNA respondents indicated they were satisfied with their jobs, 10% were not satisfied but had no intention of quitting, and 30% planned to quit (Parsons et al., 2003). The researchers found that relationships with coworkers and coworker support were related to job satisfaction but not to staff turnover. The researchers also found the two factors that most influenced CNAs’ decision to leave their employment were personal opportunities and failure of management to keep employees informed (Parsons et al., 2003). Data from our study of Iowa CNAs verifies this perception of management problems in the work environment, as those who quit their CNA job differed markedly from employed CNAs on the WES subscales of managerial control and supervisor support.

There have been several attempts to alter the nursing home environment, including the Eden Alternative® (Coleman et al., 2002) and an “institutional” implementation of the Green House® model (Kane, Lum, Cutler, Degenholtz, & Yu, 2007), but these have greater influence on the quality of life of LTC residents than on the work environment of CNAs. However, one nursing home work environment change was recently modified in a study of empowering CNA work teams through role clarification, management structure (e.g., holding meetings to discuss problems), and targeted training exercises that focus on CNA responsibility for care (Yeatts & Cready, 2007). The Yeatts and Cready quasi-experimental design did result in improved delivery of procedural treatments, better coordination in implementing activity regimens, and better cooperation between CNAs and nurses in CNA-empowered facilities, compared with non-intervention facilities. The investigators are currently conducting follow-up work to determine whether the CNA-empowered work teams reduce CNA turnover.

Historically, CNA turnover has been associated with poor supervisory and management practices, poor salaries, and poor resident outcomes (Anderson et al., 2003; Kash et al., 2006; Pennington, Scott, & Magilvy, 2003; Rondeau & Wagar, 2006). The Better Jobs Better Care Coalition (BJBC), funded by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Atlantic Philanthropies, surveyed CNAs and nursing home administrators in Iowa and revealed a context for the findings reported in this article (BJBC, 2004). For example, the Iowa BJBC study found that less than half of the administrators indicated they were given an orientation to their specific duties on their current job. CNAs were significantly more likely than both administrators and supervisors to indicate the importance of letting them know when they do “a good job.” The survey also found that 25% of Iowa’s CNAs have no health insurance coverage from any source, including government programs (BJBC, 2004).

Retirement and Health Insurance Costs

Another finding is that Iowa’s CNA workforce is aging and that approximately one third of the nursing home employers were not paying into a retirement account. We also found that more than 65% of the respondents could not afford the payroll deductions for health insurance premiums. Low-income working women have historically struggled with childrearing and family costs (Bernheimer, Weisner, & Lowe, 2003; Froehlich, 2005); it seems likely that these workers will continue in the workforce, as they may not have any retirement savings (Lee, Teng, Lim, & Gallo, 2005; Ross, Bernheim, Bradley, Teng, & Gallo, 2007).

In our opinion, these data point to a direct care worker crisis for the nursing home industry in Iowa and a shortage of younger workers. A perpetuating poverty may continue in this workforce—CNAs continuing to work into older age because they cannot afford to retire. To improve CNA salaries and increase staffing levels, the average Medicare and Medicaid reimbursement rates to nursing homes would need to be substantially increased (Harrington et al., 2007), which will not be an easy task. Policy makers will need to grapple with how much they are willing to spend on LTC to create a stable direct care workforce.

IMPLICATIONS

The need for changes in human resource management in the nursing home industry is clear. The low ratings for the WES subscale of autonomy point to limited opportunities for advancement in the CNA work environment. Regardless of how many years of experience a CNA has, they are always accountable to the licensed personnel on duty or to the Director of Nursing in the facility. Much more attention needs to be given to how CNAs are promoted and how their experience is recognized. This lockstep career advancement for CNAs is particularly troubling when one considers the longevity of many of the respondents in their work role. In general, the Iowa CNA respondents were older, experienced in their work, and unlikely to change employers, as only 11.5% had recently quit their jobs.

Comparison of the Iowa CNA data with general worker groups suggests nursing home administrators may need to use better human resource management skills, perhaps even applying concepts from industrial engineering to the LTC environment. For example, industry workers can advance to the role of frontline supervisor or progress toward less burdensome production tasks when they have achieved seniority and gained experience.

Nursing staff participation in decision making, work roles, patterns of information sharing, and the work environment/organizational climate are all factors in retaining CNAs in the LTC workforce. There is a definite need for better integration of clinical supervision and management practices into the daily operations of nursing homes and more progressive human resource practices (Dellefield, in press). Human resource practices in nursing homes need to evolve so CNAs experience respectful and supportive supervisors, receive acknowledgement from supervisors for a job well done, and have ample training opportunities to improve their skills (Karsh, Booske, & Sainfort, 2005). This is a vulnerable worker group in which socioeconomic stability is needed. More research should be conducted to develop an infrastructure in which adequate wages and benefits, as well as advancement opportunities, for CNAs are incorporated into the organizational climate (Fowler, 2003; Painter & Kennedy, 2000; Secrest et al., 2005).

Although Iowa has an older workforce in general, the mean age of our CNA respondents is alarming. Many will continue to work into their 60s, and few can afford to contribute to a retirement account. One third of the respondents in our sample indicated their employers did not contribute to retirement savings, yet only 20% indicated they did not want this included in their benefits package. In addition, two thirds of the CNAs in this sample were unable to afford health insurance premiums.

Approximately 20% of the currently employed CNAs in our sample reported this was the only position they could find; among those who left their CNA job, only 8% indicated this. It is possible that those leaving the CNA workforce had more employment opportunities, as our data suggest these individuals had fewer children younger than age 18 and only one employed adult in their households.

LIMITATIONS

The normative samples of the WES were dated and without sociodemographic information. Therefore, other worker group comparisons with the Iowa CNAs may not be valid. In addition, the Iowa CNA sample was predominately Caucasian and women, limiting the generalizability of these results to other, more diverse CNAs. Those with poor writing skills or inability to speak English may have been underrepresented. It is highly likely that there was a response bias to the question about the reason for termination, as only a few individuals reported being fired by their employers. The non-significant finding of CNA hours per resident day and WES scores may be due to overreporting of direct care workers by facility staff to CMS officials. In general, resident acuity may have affected respondents’ ratings on the WES, and this variable was not measured in our study.

FUTURE RESEARCH

From a methodological standpoint, CNAs leaving the nursing home workforce are a difficult group to track and study, but future research would contribute significantly to the workforce database if CNAs who left their jobs voluntarily are differentiated from those who were dismissed by their employers. Indeed, data obtained from targeted interviews would enhance understanding of the factors that contribute to the frequent departure of CNAs from nursing home employment and inform the quantitative data presented in this article. More work is also needed to explore factors contributing to voluntary and mandated CNA departure from the workplace and to identify variables that precipitate attrition so strategic interventions directed toward improved preparation of CNAs for the workplace can be developed and tested.

SUMMARY

Iowa’s nursing home workforce is primarily composed of older, working women. Although most started working in their 20s, few can afford health insurance or retirement benefits now that they are older. They rate the nursing home work environment differently than do other occupational groups. In general, these CNAs reported excessive managerial control and increased task orientation. We also compared those who had left their CNA job with those who stayed in the workforce. Results of this study emphasize the importance of the relationship between CNAs and RNs, the need for more innovation and less managerial control, and the need for the CNA work environment to change in a manner more consistent with other workers’ ratings of their work environment.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the John A. Hartford Foundation, with additional support from the Gerontological Nursing Interventions Research Center NIH #P30 NR03979 [Principal Investigator: Toni Tripp-Reimer, The University of Iowa College of Nursing] and the Hartford Center for Geriatric Nursing Excellence, The John A. Hartford Foundation [Principal Investigator: Kathleen Buckwalter, The University of Iowa College of Nursing]. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Nursing Research.

Contributor Information

Dr. Kennith Culp, Adult and Gerontological Area of Study.

Dr. Sandra Ramey, Adult and Gerontological Area of Study.

Ms Susan Karlman, The University of Iowa College of Nursing, Iowa City, Iowa.

References

- Anderson RA, Issel LM, McDaniel RR., Jr Nursing homes as complex adaptive systems: Relationship between management practice and resident outcomes. Nursing Research. 2003;52:12–21. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200301000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avallone I, Gibbon B. Nurses’ perceptions of their work environment in a nursing development unit. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1998;27:1193–1201. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00653.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg-Weger M, Rauch SM, Rubio DM, Tebb SS. Assessing the health of adult daughter former caregivers for elders with Alzheimer’s disease. American Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias. 2003;18:231–239. doi: 10.1177/153331750301800402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernheimer LP, Weisner TS, Lowe ED. Impacts of children with troubles on working poor families: Mixed-method and experimental evidence. Mental Retardation. 2003;41:403–419. doi: 10.1352/0047-6765(2003)41<403:IOCWTO>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Better Jobs Better Care Coalition. Unpublished manuscript. 2004. Iowa Better Jobs Better Care summary of key research findings. Iowa Caregivers Association. [Google Scholar]

- Bostick JE, Rantz MJ, Flesner MK, Riggs CJ. Systematic review of studies of staffing and quality in nursing homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2006;7:366–376. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2006.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgio LD, Fisher SE, Fairchild JK, Scilley K, Hardin JM. Quality of care in the nursing home: Effects of staff assignment and work shift. The Gerontologist. 2004;44:368–377. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.3.368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castle NG, Lowe TJ. Report cards and nursing homes. The Gerontologist. 2005;45:48–67. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.1.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caudill ME, Patrick M. Turnover among nursing assistants: Why they leave and why they stay. Journal of Long Term Care Administration. 1991;19(4):29–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman MT, Looney S, O’Brien J, Ziegler C, Pastorino CA, Turner C. The Eden Alternative: Findings after 1 year of implementation. Journals of Gerontology Series A, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 2002;57:M422–M427. doi: 10.1093/gerona/57.7.m422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellefield ME. Best practices in nursing homes: Clinical supervision, management, and human resource practices. Research in Gerontological Nursing. doi: 10.3928/19404921-20080701-06. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick PG. Turnover of certified nursing assistants: A major problem for long-term care facilities. Hospital Topics. 2002;80(2):21–25. doi: 10.1080/00185860209597991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowler V. Health care assistants: Developing their role to include nursing tasks. Nursing Times. 2003;99(36):34–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Froehlich J. Steps toward dismantling poverty for working, poor women. Work. 2005;24:401–408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaddy T, Bechtel GA. Nonlicensed employee turnover in a long-term care facility. Health Care Supervisor. 1995;13(4):54–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grieshaber LD, Parker P, Deering J. Job satisfaction of nursing assistants in long-term care. Health Care Supervisor. 1995;13(4):18–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman C. Older Americans 2000. New data system that tracks health and well-being finds successes and disparities. Geriatrics. 2000;55(10):63–66. 69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington C. Quality of care in nursing home organizations: Establishing a health services research agenda. Nursing Outlook. 2005;53:300–304. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington C, Swan JH. Nursing home staffing, turnover, and case mix. Medical Care Research and Review. 2003;60:366–392. doi: 10.1177/1077558703254692. discussion 393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrington C, Swan JH, Carrillo H. Nurse staffing levels and Medicaid reimbursement rates in nursing facilities. Health Services Research. 2007;42(3 Part 1):1105–1129. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00641.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iowa Department of Public Health. Unpublished manuscript. 2005. A report prioritizing a potential shortage of licensed health care professionals in Iowa. [Google Scholar]

- Janiszewski Goodin H. The nursing shortage in the United States of America: An integrative review of the literature. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2003;43:335–343. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02722_1.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jogerst GJ, Daly JM, Dawson JD, Peek-Asa C, Schmuch G. Iowa nursing home characteristics associated with reported abuse. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2006;7:203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2005.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson P. Issue Brief. Health Policy Tracking Service; 2005. Dec 31, Medicaid: Benefits and services—2005. End of Year Issue Brief; pp. 1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones A. The National Nursing Home Survey: 1999 summary. Vital Health Statistics Series. 2002;13(152):1–116. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane RA, Lum TY, Cutler LJ, Degenholtz HB, Yu TC. Resident outcomes in small-house nursing homes: A longitudinal evaluation of the initial green house program. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2007;55:832–839. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01169.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karsh B, Booske BC, Sainfort F. Job and organizational determinants of nursing home employee commitment, job satisfaction and intent to turnover. Ergonomics. 2005;48:1260–1281. doi: 10.1080/00140130500197195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kash BA, Castle NG, Naufal GS, Hawes C. Effect of staff turnover on staffing: A closer look at registered nurses, licensed vocational nurses, and certified nursing assistants. The Gerontologist. 2006;46:609–619. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.5.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lapane KL, Hughes CM. Considering the employee point of view: Perceptions of job satisfaction and stress among nursing staff in nursing homes. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2007;8:8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2006.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YG, Teng HM, Lim SH, Gallo WT. Older workers: Who are the working poor in the U.S.? Hallym International Journal of Aging. 2005;7(2):95–113. doi: 10.2190/1276-6122-80w6-7r47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu LF. Job satisfaction of certified nursing assistants and its influence on the general satisfaction of nursing home residents: An exploratory study in southern Taiwan. Geriatric Nursing. 2007;28:54–62. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2006.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae N, Prior S, Silverman M, Banerjee S. Workplace satisfaction in a mental health service for older adults: An analysis of the effects of setting and professional status. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 2007;21:17–24. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore JD., Jr Nurse union gains in Calif. CNA uses favorable market conditions to win pay increases, organize new units. Modern Healthcare. 1999;29(37):33, 36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH. The social climate scales: A user’s guide. 2. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1994a. [Google Scholar]

- Moos RH. Work environment scale manual. 3. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologists Press; 1994b. [Google Scholar]

- Moyle W, Skinner J, Rowe G, Gork C. Views of job satisfaction and dissatisfaction in Australian long-term care. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2003;12:168–176. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00732.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntaner C, Van Dussen DJ, Li Y, Zimmerman S, Chung H, Benach J. Work organization, economic inequality, and depression among nursing assistants: A multilevel modeling approach. Psychological Reports. 2006;98:585–601. doi: 10.2466/pr0.98.2.585-601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Clearinghouse on the Direct Care Workforce. State activities: Iowa. 2004 Retrieved February 27, 2008, from http://www.directcareclearinghouse.org/s_state_det.jsp?action=view&res_id=15.

- Painter W, Kennedy B. The evolving role of certified nursing assistants in long-term care facilities. Part three. Director. 2000;8:56–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons SK, Simmons WP, Penn K, Furlough M. Determinants of satisfaction and turnover among nursing assistants. The results of a statewide survey. Journal of Gerontological Nursing. 2003;29(3):51–58. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20030301-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pennington K, Scott J, Magilvy K. The role of certified nursing assistants in nursing homes. Journal of Nursing Administration. 2003;33:578–584. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200311000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Priester R, Reinardy JR. Recruiting immigrants for long-term care nursing positions. Journal of Aging & Social Policy. 2003;15(4):1–19. doi: 10.1300/J031v15n04_01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravaglia G, Forti P, Maioli F, Montesi F, Rietti E, Pisacane N, et al. Risk factors for dementia: Data from the Conselice study of brain aging. Archives of Gerontology and Geriatrics. 2007;44(Suppl 1):311–320. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2007.01.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed SC, Andes S. Supply and segregation of nursing home beds in Chicago communities. Ethnicity & Health. 2001;6:35–40. doi: 10.1080/13557850124941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rondeau KV, Wagar TH. Nurse and resident satisfaction in Magnet long-term care organizations: Do high involvement approaches matter? Journal of Nursing Management. 2006;14:244–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2934.2006.00594.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross JS, Bernheim SM, Bradley EH, Teng HM, Gallo WT. Use of preventive care by the working poor in the United States. Preventive Medicine. 2007;44:254–259. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2006.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seago JA, Spetz J, Chapman S, Dyer W. Can the use of LPNs alleviate the nursing shortage? Yes, the authors say, but the issues—involving recruitment, education, and scope of practice—are complex. American Journal of Nursing. 2006;106(7):40–49. doi: 10.1097/00000446-200607000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Secrest J, Iorio DH, Martz W. The meaning of work for nursing assistants who stay in long-term care. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2005;14(8B):90–97. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2005.01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selvam A. The state of the health care workforce. Hospitals and Health Networks. 2001;75(8):41, 43–46, 48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Squillace MR, Remsburg RE, Bercovitz A, Rosenoff E, Branden L. An introduction to the National Nursing Assistant Survey. Vital Health Statistics Series. 2007;1(44):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuart B, Gruber-Baldini AL, Fahlman C, Quinn CC, Burton L, Zuckerman IH, et al. Medicare cost differences between nursing home patients admitted with and without dementia. The Gerontologist. 2005;45:505–515. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.4.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. States and Puerto Rico ranked by population 85 years and over: 1990 and 2000. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Commerce, Economics and Statistics Administration; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Vagg PR, Spielberger CD. Occupational stress: Measuring job pressure and organizational support in the workplace. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology. 1998;34:294–305. doi: 10.1037//1076-8998.3.4.294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardell RC. When OASIS becomes our report card. Home Healthcare Nurse. 2003;21:415. doi: 10.1097/00004045-200306000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weech-Maldonado R, Shea D, Mor V. The relationship between quality of care and costs in nursing homes. American Journal of Medical Quality. 2006;21:40–48. doi: 10.1177/1062860605280643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeatts DE, Cready CM. Consequences of empowered CNA teams in nursing home settings: A longitudinal assessment. The Gerontologist. 2007;47:323–339. doi: 10.1093/geront/47.3.323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]