Abstract

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) is an inhibitory receptor on T cells essential for maintaining T cell homeostasis and tolerance to self. Mice lacking CTLA-4 develop an early onset, fatal breakdown in T cell tolerance. Whether this autoimmune disease occurs because of the loss of CTLA-4 function in regulatory T cells, conventional T cells, or both is unclear. We show here that lack of CTLA-4 in regulatory T cells leads to aberrant activation and expansion of conventional T cells. However, CTLA-4 expression in conventional T cells prevents aberrantly activated T cells from infiltrating and fatally damaging nonlymphoid tissues. These results demonstrate that CTLA-4 has a dual function in maintaining T cell tolerance: CTLA-4 in regulatory T cells inhibits inappropriate naïve T cell activation and CTLA-4 in conventional T cells prevents the harmful accumulation of self-reactive pathogenic T cells in vital organs.

Keywords: migration, peripheral T cell tolerance, T regulatory cells

Cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) is an indispensable regulator of peripheral T cell tolerance. Ctla4−/− mice suffer from a severe, early-onset autoimmune disease mediated by CD4+ T cells that is lethal by 3–4 weeks of age (1 –3). In conventional T cells, CTLA-4 expression on the cell surface is induced after TCR signaling (4). In contrast, CTLA-4 is constitutively expressed on CD4+FOXP3+ regulatory T (Treg) cells (5), in part because FOXP3 directs CTLA-4 transcription (6). Because FOXP3+ Treg cells dominantly control T cell self-tolerance (7) and Foxp3−/− mice resemble Ctla4−/− mice in autoimmune disease progression (8), it has been speculated that the primary function of CTLA-4 is to affect Treg cell-mediated tolerance induction (5, 9). Consistent with this notion, we have shown that CTLA-4-expressing Treg cells are necessary and sufficient to control Ctla4−/− T cell activation in vivo (10). Further, Ctla4 deletion specifically in Treg cells by FOXP3-Cre precipitates autoimmunity akin to Ctla4−/− mice, although the life span of these mice is significantly extended compared to Ctla4−/− mice (11). These results suggest that in addition to a critical role for CTLA-4 in Treg cells, CTLA-4 may also function in conventional T cells to regulate autoimmunity.

CTLA-4 expression is induced in conventional T cells very rapidly after TCR engagement (12) with peak protein expression in fully activated and dividing T cells (4, 13, 14). We sought to determine if this conventional T cell intrinsic expression of CTLA-4 was consequential to the maintenance of peripheral T cell tolerance. We generated mice expressing functional CTLA-4 only in activated T cells and not in Treg cells using a Ctla4 transgene (Tg) whose expression is driven by the Il2 promoter in Ctla4−/− mice. As expected, CTLA-4-less Treg cells were unable to inhibit aberrant naive T cell activation. Critically, although activated T cell–restricted CTLA-4 expression could not prevent lymphoproliferation, it was sufficient to prevent activated T cell accumulation in nonlymphoid organs, thereby extending the life span of Ctla4−/− mice. These results reveal a function for CTLA-4 in conventional T cells to regulate the transit of aberrantly activated, pathogenic T cells, as well as in Treg cells to prevent self-reactive T cell activation and expansion.

Results

Massive T Cell Activation and Expansion in Mice Lacking CTLA-4 Expression in Treg Cells.

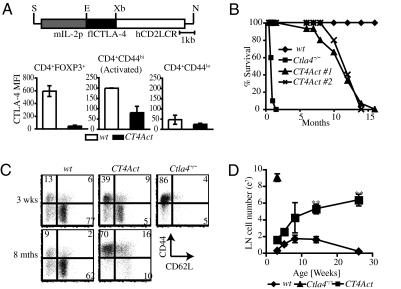

We generated transgenic (Tg) C57BL/6J mice (CT4Act) with activated T cell subset restricted expression of CTLA-4 by linking Ctla4 expression under the control of the Il2 promoter in Ctla4−/− mice (Fig. 1A Top) (15). To establish the kinetics of transgene expression in T cells, we crossed the CT4Act mice with 5C.C7TcrTgRag−/−Ctla4−/− mice to obtain a homogenous naïve T cell population. TgCT4Act mRNA was not expressed in ex vivo naïve CD4+ T cells but was rapidly up-regulated upon T cell activation (Fig. S1A). Similarly, intracellular (i.c.) TgCT4Act protein was detected in in vitro activated CD4+CD44hiCD69+ T cells at 24 h that diminished by 72 h postactivation (Fig. S1B). Further, TgCT4Act expression was functional, as cross-linking CTLA-4 on cell surface using anti-CTLA-4–coated Sepharose beads resulted in decreased activation (Fig. S1C) and cell division (Fig. S1D) of CT4Act CD4+T cells.

Fig. 1.

Massive T cell activation and expansion in mice lacking CTLA-4 expression in Treg cells (A Upper) Restriction enzyme map of Il2pCtla4Tg construct. Full length (fl) CTLA-4 cDNA was cloned 3′ of the mouse Il2 promoter and 5′ of the human CD2 locus-control region (LCR). Restriction endonuclease sites S: Sal1, E: EcoR1, Xb: Xba1, N: Not1. (Lower) Intracellular CTLA-4 expression in T cell subsets from 6- to 12-week-old WT and CT4Act mice was determined by flow cytometry. Data are the average of Mean Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) of CTLA-4 expression determined over at least five independent experiments with two to three mice in each group per experiment. For comparison, background CTLA-4 staining from Ctla4−/− CD4+T cells had MFI of 30. (B) WT (n = 10, ◆), Ctla4−/− (n = 10, ■ ) and two founder lines of CT4Act (n = 15, ▲, X) mice were observed for signs of disease and mortality over the indicated months. Results are represented as percent survival, which was calculated as 100× (number of surviving mice/total number of mice) at each time point. (C) Representative flow cytometric dot plot showing expression of activation markers CD44 and CD62L on CD4+FOXP3− T cells in peripheral LNs of WT and CT4Act mice at 3 weeks and 8 months of age and Ctla4−/− mice at 3 weeks of age. Data are representative of at least three independent experiments with two to three mice per group. (D) Total cellularity of inguinal, axillary and brachial LNs in WT (◆), Ctla4−/− (▲), and CT4Act (■) mice at different ages. Data are a mean of at least four mice per group at each time point. (** P ≤ 0.001)

The Il2 promoter is suppressed in Treg cells (16 –18) and they transcribe very little Il2 (19). The Tg promoter replicated this pattern and FOXP3+ Treg cells in CT4Act mice lacked i.c. and surface CTLA-4 expression (Fig. 1A Bottom, and Figs. S2A and S3A). As the Il2 promoter is operational when T cells are activated, CTLA-4 expression in CT4Act mice was predicted to be restricted to activated CD4+CD44hi T cells, and this was indeed the case (Fig. 1A Bottom, Fig S2 A and B). With this targeted expression of CTLA-4, CT4Act mice had a significantly extended life span, with approximately 50% of mice surviving till 10–12 months of age (Fig. 1B). This is in contrast to previous observations in BALB/c mice, in which a specific deletion of Ctla4 in FOXP3+ Treg cells resulted in death of mice by 7–10 weeks of age (11). However, similar to these mice, lack of CTLA-4 expression in Treg cells of CT4Act mice led to the increased activation and expansion of conventional CD4+ T cells, as reflected by an increased frequency of CD44hiCD62Lneg T cells (Fig. 1C) and increased cellularity of peripheral lymph nodes (Fig. 1D). As mice aged, numbers of CD8+T cells and B cell also increased although thymic subset cell distribution was normal (Table S1 and S2). These results suggested that CTLA-4 expression in Treg cells was primarily responsible in preventing aberrant naïve T cell activation, but additional functions of CTLA-4 in conventional T cells may moderate the pathogenicity of activated, self-reactive T cells.

Ctla4-Deficient FOXP3+Treg Cells Are Functionally Impaired in Vivo.

Phenotypically, FOXP3+ Treg cells from CT4Act mice and Ctla4−/− mice were similar (Fig. S3B). There was also an increased frequency of CD4+FOXP3+ cells as early as 7 days after birth in CT4Act mice, a trend observed in Ctla4−/− mice (Fig. S3C), ruling out the possibility that reduced Treg cell numbers per se potentiated the T cell lymphoproliferation in CT4Act mice. To demonstrate that the aberrant naive T cell activation in CT4Act mice was caused by functionally impaired Treg cells, we investigated the extent to which Treg cells from CT4Act mice are defective in vivo and whether the lymphoproliferation in CT4Act mice can be prevented by WT Treg cells.

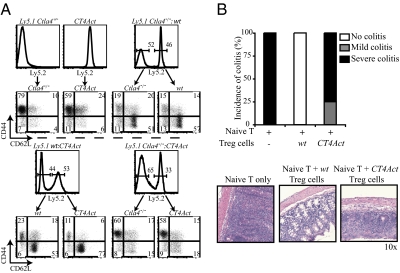

We have previously demonstrated that in mixed bone marrow (BM) chimeras containing WT and Ctla4−/− T cells, CTLA-4-sufficient WT Treg cells inhibit the activation of Ctla4−/− T cells (10). We used this in vivo assay of trans regulation of Ctla4−/− T cells to further test the functionality of CT4Act Treg cells. Rag1−/− hosts reconstituted with BM cells from Ctla4−/− or CT4Act mice alone are replete with activated CD44+CD62LnegCD4+ T cells (Fig. 2A Upper Left). In the presence of WT BM-derived T cells, Ctla4−/− and CT4Act T cells did not expand and remained mostly naïve (CD44loCD62Lhi) (Fig. 2A Upper Right and Lower Left). This result indicated that the aberrant T cell activation in CT4Act mice occurred because of defective Treg cells. Conversely, to test whether CTLA-4-less Treg cells from CT4Act mice could prevent aberrant activation of self-reactive T cells, CT4Act:Ctla4−/− mixed chimeras were analyzed. In contrast to WT Treg cells, CT4Act Treg cells failed to regulate the activation and expansion of Ctla4−/− CD4+ T cells, and the chimeras rapidly succumbed to a fatal lymphoproliferative disease (Fig. 2A Lower Right).

Fig. 2.

Ctla4-deficient FOXP3+Treg cells are functionally impaired in vivo (A) BMCs were generated in Rag1−/− mice by injecting T cell-depleted BM cells from either Ly5.1+ Ctla4−/− or CT4Act mice (Upper Left, negative controls), or coinjecting a mix of BM cells from WT and Ly5.1+ Ctla4−/− mice (Upper Right), Ly5.1 WT and CT4Act mice (Lower Left), and Ly5.1 Ctla4−/− and CT4Act mice (Lower Right). Six to eight weeks after reconstitution, before some BMCs became fatally sick, mice were euthanized and LN cells were stained with Ly5 congenic marker to determine contributions of each group to the peripheral lymphocyte compartment. Ly5.2+ and Ly5.2− CD4+ T cells were further analyzed for the expression of activation markers CD44 and CD62L. Data are representative of two independent experiments with three mice in each group. (B) CD4+CD25+ Treg cells from WT, and CT4Act mice were transferred with WT CD4+CD25neg T cells into Rag1−/− mice to test their ability to prevent colitis. (Upper) Colitis was scored as described in ref. 32. Data are representative of two independent experiments with four to five mice in each group. (Lower) Representative H&E stained sections of colons of Rag1−/− mice after transfer of T cells. Mice that received naïve WT T cells (Left) developed severe colitis, which was prevented by cotransfer of WT Treg cells (Middle). Mice constituted with naïve WT T cells and CT4Act Treg cells (Right) developed colitis, displaying substantial inflammatory infiltrates and significant epithelial hyperplasia with loss of goblet cells. However, the severity of colitis was milder as compared to mice receiving only naive WT T cells. (Original magnification, ×10.)

CTLA-4-less Treg cells were also unable to suppress aberrant activation of WT T cells. In a T cell transfer model of colitis, Treg cells from CT4Act mice could not prevent colitis initiated by coinjected WT naïve T cells. Although WT Treg cells were able to efficiently regulate the colitogenic T cells and this cohort of T cell transferred hosts remained healthy (Fig. 2B Upper), the mice receiving CT4Act Treg cells succumbed to a wasting disease, displaying massive lymphocyte infiltration and significant epithelial hyperplasia (Fig. 2B Lower). Together, these results demonstrate that Treg cells from CT4Act mice that lack CTLA-4 are functionally impaired and that the defects in Treg cells are responsible for the lymphoproliferation in CT4Act mice.

CTLA-4 Expression in Activated T Cells Restricts Tissue Infiltration and Pathology.

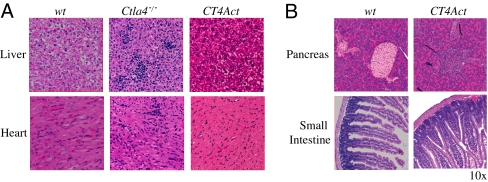

Despite the functionally impaired Treg cells and rampant T cell activation, CT4Act mice survived significantly longer compared to Ctla4−/− mice. To determine if activated, conventional T cell-intrinsic expression of CTLA-4 contributed to this survival benefit, we first determined why CT4Act mice are protected from early onset fatal autoimmunity. In contrast to Ctla4−/− mice, there was a striking absence of lymphocytic infiltration in nonlymphoid organs of CT4Act mice even at 6–8 months of age (Fig. 3A). As the mice aged, however, the small intestine and pancreas were not protected, and there was extensive mononuclear cell infiltration in both tissues. The pancreas of older CT4Act mice showed evidence of T cell infiltration of β-islet cells (Fig. 3B), although the mice were not hyperglycemic up to approximately 12 months of age. The small intestine, but not the colon, showed diffused hyperplasia, increased plasma B cell and necrotic cell numbers in the mucosal epithelia, but limited epithelial cell damage (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

CTLA-4 expression in activated T cells restricts tissue infiltration and pathology. Lymphocyte infiltration in WT (7 months old), Ctla4−/− (3-4 weeks old) and CT4Act (7 months old) mice was determined by histology. (A) Representative H&E stained sections of liver and heart showed extensive lymphocyte infiltration only in sick Ctla4−/− mice. (B) Pancreatic β-islets and small intestines were infiltrated with lymphocytes in 8-month-old CT4Act mice. At least two sections/mouse and multiple fields were analyzed. (Original magnification, ×10.)

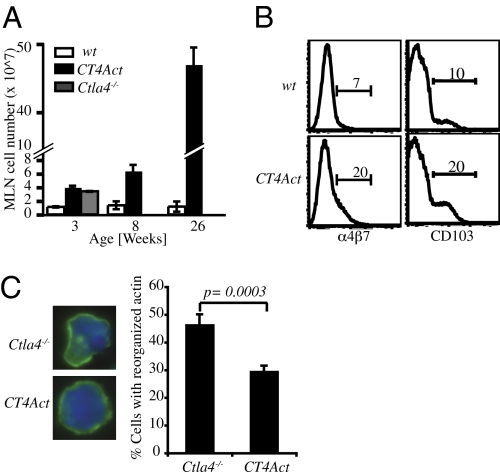

The restricted tissue pathology suggested that the lymph node (LN) and tissue homing characteristics of activated CT4Act CD4+T cells might be altered by CTLA-4 expression. Indeed, there was a disproportionate increase in the size of the mesenteric LNs (MLNs) of CT4Act mice compared to other peripheral LNs (Fig. 4A). Accompanying this was an increased frequency of CD4+CD44hi T cells expressing the gut and pancreas homing receptors, CD103 and α4β7 (Fig. 4B). In addition to the expression of specific tissue homing receptors, T cells also undergo actin cytoskeletal rearrangements during their movement from the blood circulation into tissues. Costimulatory signals from CD28 have been implicated in this process (20), and CTLA-4 itself has been suggested to regulate the motility of T cells (21). Because CTLA-4 can compete with CD28 for B7 ligands to inhibit CD28 signals, we investigated whether CTLA-4 expression in CT4Act T cells altered the actin morphology of these migratory T cells. The majority of activated Ctla4−/− CD4+ T cells had the distinct morphology of migrating T cells with polarized F-actin. In contrast, most of the activated CT4Act CD4+ T cells appeared not to have reorganized their actin cytoskeleton and resembled resting T cells in morphology (Fig. 4C ). These results suggest that one aspect of T cell activation that is regulated by CTLA-4 in a T cell-intrinsic manner is the modifications of aberrantly activated T cell trafficking into nonlymphoid organs.

Fig. 4.

Altered homing capabilities of CTLA-4 expressing activated T cells in CT4Act mice. (A) Total cellularity of MLNs at different ages in WT, Ctla4−/− and CT4Act mice. Data are a mean of at least four mice per group at each time point. (B) Expression of homing markers α4β7 and CD103 on CD4+CD44hi activated T cells from MLN of 2- to 3-month-old WT and CT4Act mice as determined by flow cytometry. Data are representative of three independent experiments with three to four mice in each group. (C Left) Representative F-actin localizations in CD4+ T cells from MLNs of Ctla4−/− and CT4Act mice analyzed by fluorescence microscopy. Green: F-actin staining using phalloidin-Alexa 488; Blue: nuclear staining using DAPI. (Right) Frequency of CD4+T cells with polarized F-actin. Data are generated from three independent experiments with a total of at least 400 cells analyzed for each genotype.

Discussion

CTLA-4 is expressed in both activated conventional T cells and Treg cells; however, the relative T cell subset-specific function of CTLA-4 in maintaining T cell tolerance is unclear. In this report, we describe a mouse model of activated T cell subset-restricted CTLA-4 expression and demonstrate that CTLA-4 mediates distinct functions in activated T cells and Treg cells to achieve T cell tolerance. Expression of an Il2-promoter regulated TgCtla4 in Ctla4−/− mice results in functional CTLA-4 expression in activated T cells but not in FOXP3+ Treg cells. CTLA-4-less Treg cells are functionally impaired in vivo and cannot prevent aberrant activation of T cells to self or environmental antigens, despite the fact that conventional T cells are capable of expressing CTLA-4 within hours of activation. Strikingly, activated lymphocytes in adult CT4Act mice that express CTLA-4 do not traffic to and/or accumulate in peripheral nonlymphoid organs. This lack of tissue infiltration is not due to some residual Treg cell function because extensive T cell infiltration into diverse tissues was evident in mixed chimeras composed of CT4Act: Ctla4−/− BM-derived cells.

It is important to emphasize, however, that this conclusion does not imply that CTLA-4-less Treg cells are completely nonfunctional. Treg cells from Ctla4−/− mice can suppress conventional T cell activation in vitro (22), and there are some indications, albeit not universal, that these cells can function to inhibit colitogenic T cells in a T cell transfer model (23) and that they can delay the early fatality associated with Foxp3 null mutation (24). Conversely, mice lacking FOXP3 do succumb to rapid, fatal lymphoproliferative disease despite the fact that activated T cells can express CTLA-4 (25), suggesting that the absence of CTLA-4 on Treg cells is not functionally equivalent to the loss of Treg cells. Given the notion that Treg cells may use multiple effector mechanisms (26), including IL-10 (27) and TGFβ (28), to regulate T cell tolerance, it is not unexpected that ablation of CTLA-4 in Treg cells do not make them inert. Hence, although both Foxp3−/− and Ctla4−/− mice die of an early lymphoproliferative disease, the causes are distinct; in the former it is the loss of FOXP3-dependent functions of Treg cells, whereas in the latter it is the combined effect of the loss of CTLA-4 in Treg cells and in activated T cells. In CT4Act mice, CTLA-4-less Treg cells may afford a moderation in immune activation that allows Treg cell-independent function of CTLA-4 to take effect in vivo. However, other compensatory mechanisms cannot prevent naïve T cell activation in the absence of CTLA-4 on Treg cells and cannot control the eventual tissue destruction by aberrantly activated T cells.

The extended survival of CT4Act mice is in contrast to that of conditional Ctla4-deficient mice (Foxp3Cre:Ctla4fx/fx) in the BALB/c background, which lack CTLA-4 expression in Treg cells (11). These mice succumb to a delayed fatal lymphoproliferative disease and die by 7–10 weeks of age. Critically, the disease course in CT4Act mice is not simply a delay in pathogenesis or in moderations of the pace and magnitude of aberrant T cell activation because even in CT4Act mice suffering from fulminant enteritis and extreme lymphoproliferation, most nonlymphoid tissues are spared from T cell infiltration. This difference in phenotype, in part, may be attributed to the difference in genetic backgrounds and as yet undefined differences in functional properties of Treg cells during their early development in CT4act versus Foxp3Cre:Ctla4fx/fx mice.

The mechanism by which CTLA-4 expression on aberrantly activated T cells can regulate their potential destructive actions remains speculative. It has been shown previously that expression of a CTLA-4Tg lacking the cytoplasmic signaling domain of the protein in Ctla4−/− mice results in aberrant T cell activation and lymphoproliferation in the absence of tissue infiltration (29). Given that one major function of CTLA-4 in conventional T cells is to inhibit CD28 signals (30), which has been shown in several situations to regulate homing of T cells (31), a straightforward interpretation is that CTLA-4 can compete with CD28 for B7 ligand binding on antigen presenting cells, and that this mode of inhibition does not require biochemical signaling initiated from the CTLA-4 cytoplasmic region. We propose that this CTLA-4-cytoplamic tail-independent inhibition of CD28 signaling contributes to the lack of tissue infiltration in CT4Act mice.

Collectively, we demonstrate a dual function of CTLA-4 in regulating T cell tolerance. CTLA-4 is absolutely required on Treg cells to regulate the aberrant activation of conventional naïve T cells to self or environmental antigens in the periphery in trans irrespective of whether or not conventional T cells can express CTLA-4. In addition, in cis, CTLA-4 expression in aberrantly activated T cells can modulate rampant autoimmune tissue destruction and alter the disease course.

Materials and Methods

Mice.

The IL-2P/GFP/CD2 transgene construct was a kind gift from Casey Weaver (University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL) (15). After EcoR1 and Xba1 digestion, the 1.4-kb full-length CTLA-4 cDNA construct from SKCwt5/10 was inserted in place of GFP in BOB1cwt10 plasmid containing IL-2 transgene. The 9.6 kB IL-2P/CTLA4/CD2 transgene was isolated from pIL-2P(hs65TGFP)-hC2 following Not1 and Sal1 digestion and injected by UMass Transgenic Facility, Worcester, MA, to generate transgenic mice. Transgene-positive founders were identified by PCR analysis. Four different founder lines were established, of which two were chosen for crossing with Ctla4+/− mice to generate CT4Act mice. Some mice were also crossed to 5C.C7TCRTgCtla4−/−Rag−/− mice to generate 5C.C7TCRTg+ CT4ActRag−/− mice. All mice used in these experiments were housed in a specific pathogen-free rodent barrier facility. All experiments were approved by the University of Massachusetts Medical School Institutional Care and Use Committee.

Antibodies, Flow Cytometry, and Cell Sorting.

Fluorescently labeled Abs specific to CD4, CD8α, CD44, CD62L, CD69, CTLA-4, CD103, α4β7, and Ly5.2 were purchased from BD Pharmingen and Abs specific to FOXP3, CD25, CD5, GITR, and CCR7 were purchased from eBiosciences. Intranuclear FOXP3 and intracellular CTLA-4 stainings were performed according to the manufacturers’ protocol (eBiosciences and BD Pharmingen, respectively). All data were acquired on the LSRII (BD), and analyzed using FlowJo software (Treestar).

Peripheral T cell subsets including CD4+CD25− conventional T cells and CD4+CD25+ Treg cells were sorted to greater than 95% purity using MoFlo (Cytomation) cell sorter. CD4+T cells were enriched from mesenteric lymph nodes using CD8 and B220 MACS (Miltenyi Biotec) beads according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Colitis.

First, 5 × 105 CD4+CD25− naïve T cells from WT mice were transferred to lymphocyte-deficient (Rag1−/−) mice to induce colitis. To test the function of Treg cells in preventing colitis, 2 × 105 CD4+CD25+ Treg cells from WT, Ctla4−/− and CT4Act mice were coinjected. Mice were weighed weekly and examined for signs of colitis and wasting. Mice were killed and colons removed at 4–5 weeks after T cell reconstitution for histological examination. Colitis was scored as described in ref. 32.

Mixed Bone Marrow Chimeras (BMC).

Mixed BMCs were set up as described in (10). Briefly, BM was flushed from the femurs and tibias of donor mice and depleted of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells using magnetic Dynal beads; 4 × 106 BM cells were injected into lightly irradiated (300 rads) Rag1−/− mice via the tail vein. Mice were bled periodically to determine reconstitution of the peripheral T cell pool. Mice were killed and analyzed at greater than 12 weeks posttransfer.

Histological Examination.

Organs were removed and fixed in 10% formalin. Four microns paraffin embedded sections were cut and stained with H&E. At least four sections and multiple fields were analyzed.

Actin Staining.

CD4+ T cells were enriched from MLNs of 3- to 4-week-old Ctla4−/− and 10- to 12-week-old CT4Act mice by depleting CD8+ T cells and B cells using MACS beads. Both the Ctla4−/− and CT4Act populations contained more than 85% CD44hiCD62Llo activated T cells; 2 × 106 CD4+ T cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and permeabilized in 0.15% saponin. Cells were stained for actin with phalloidin-488 (5 units, Invitrogen) followed by DAPI staining of nuclei. Images were captured using a Nikon Eclipse E 600 microscope with a Hamamatsu Orca-ER cooled charge-coupled device camera (Hamamatsu Photonics) and IPlab Spectrum software (Scanalytics). At least 15 fields were photographed and no less than 100 cells per sample were analyzed for each experiment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Barbara Banner for her assistance in histology, the University of Massachusetts Medical School Flow Cytometry Core Facility staff for cell sorting, Dr. Casey Weaver for the IL-2 promoter construct, Samriddha Ray and Dr. Dan McCollum for assistance with microscopy, Dr. Leslie Berg for discussion and critical reading of the manuscript, Drs. Mark Bix and Eric Huseby for helpful comments on the manuscript, and members of the Kang Laboratory for discussions. Core resources supported by Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center Grant DK32520 were used. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AI054670 and AI59880 (to J.K.).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0910341107/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Waterhouse P, et al. Lymphoproliferative disorders with early lethality in mice deficient in CTLA-4. Science. 1995;270:985–988. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5238.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tivol EA, et al. Loss of CTLA-4 leads to massive lymphoproliferation and fatal multiorgan tissue destruction, revealing a critical negative regulatory role of CTLA-4. Immunity. 1995;3:541–547. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90125-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chambers CA, Sullivan TJ, Allison JP. Lymphoproliferation in CTLA-4-deficient mice is mediated by costimulation-dependent activation of CD4+ T cells. Immunity. 1997;7:885–895. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80406-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Perkins D, et al. Regulation of CTLA-4 expression during T cell activation. J Immunol. 1996;156:4154–4159. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Takahashi T, et al. Immunologic self-tolerance maintained by CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory T cells constitutively expressing cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4. J Exp Med. 2000;192:303–310. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Y, et al. FOXP3 controls regulatory T cell function through cooperation with NFAT. Cell. 2006;126:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.05.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fontenot JD, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. Foxp3 programs the development and function of CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:330–336. doi: 10.1038/ni904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brunkow ME, et al. Disruption of a new forkhead/winged-helix protein, scurfin, results in the fatal lymphoproliferative disorder of the scurfy mouse. Nat Genet. 2001;27:68–73. doi: 10.1038/83784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Read S, Malmström V, Powrie F. Cytotoxic T lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 plays an essential role in the function of CD25(+)CD4(+) regulatory cells that control intestinal inflammation. J Exp Med. 2000;192:295–302. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.2.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Friedline RH, et al. CD4+ regulatory T cells require CTLA-4 for the maintenance of systemic tolerance. J Exp Med. 2009;206:421–434. doi: 10.1084/jem.20081811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wing K, et al. CTLA-4 control over Foxp3+ regulatory T cell function. Science. 2008;322:271–275. doi: 10.1126/science.1160062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunner MC, et al. CTLA-4-Mediated inhibition of early events of T cell proliferation. J Immunol. 1999;162:5813–5820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lindsten T, et al. Characterization of CTLA-4 structure and expression on human T cells. J Immunol. 1993;151:3489–3499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inobe M, Schwartz RH. CTLA-4 engagement acts as a brake on CD4+ T cell proliferation and cytokine production but is not required for tuning T cell reactivity in adaptive tolerance. J Immunol. 2004;173:7239–7248. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.12.7239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saparov A, et al. Interleukin-2 expression by a subpopulation of primary T cells is linked to enhanced memory/effector function. Immunity. 1999;11:271–280. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1142–1151. doi: 10.1038/ni1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burchill MA, Yang J, Vogtenhuber C, Blazar BR, Farrar MA. IL-2 receptor beta-dependent STAT5 activation is required for the development of Foxp3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:280–290. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.1.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Setoguchi R, Hori S, Takahashi T, Sakaguchi S. Homeostatic maintenance of natural Foxp3(+) CD25(+) CD4(+) regulatory T cells by interleukin (IL)-2 and induction of autoimmune disease by IL-2 neutralization. J Exp Med. 2005;201:723–735. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Su L, et al. Murine CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells fail to undergo chromatin remodeling across the proximal promoter region of the IL-2 gene. J Immunol. 2004;173:4994–5001. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.8.4994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salazar-Fontana LI, Barr V, Samelson LE, Bierer BE. CD28 engagement promotes actin polymerization through the activation of the small Rho GTPase Cdc42 in human T cells. J Immunol. 2003;171:2225–2232. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider H, et al. Reversal of the TCR stop signal by CTLA-4. Science. 2006;313:1972–1975. doi: 10.1126/science.1131078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tang Q, et al. Distinct roles of CTLA-4 and TGF-beta in CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cell function. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34:2996–3005. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Read S, et al. Blockade of CTLA-4 on CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells abrogates their function in vivo. J Immunol. 2006;177:4376–4383. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.7.4376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chikuma S, Bluestone JA. Expression of CTLA-4 and FOXP3 in cis protects from lethal lymphoproliferative disease. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:1285–1289. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kim JM, Rasmussen JP, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cells prevent catastrophic autoimmunity throughout the lifespan of mice. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:191–197. doi: 10.1038/ni1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tang Q, Bluestone JA. The Foxp3+ regulatory T cell: a jack of all trades, master of regulation. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:239–244. doi: 10.1038/ni1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubtsov YP, et al. Regulatory T cell-derived interleukin-10 limits inflammation at environmental interfaces. Immunity. 2008;28:546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakamura K, Kitani A, Strober W. Cell contact-dependent immunosuppression by CD4(+)CD25(+) regulatory T cells is mediated by cell surface-bound transforming growth factor beta. J Exp Med. 2001;194:629–644. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.5.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masteller EL, Chuang E, Mullen AC, Reiner SL, Thompson CB. Structural analysis of CTLA-4 function in vivo. J Immunol. 2000;164:5319–5327. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.164.10.5319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Teft WA, Kirchhof MG, Madrenas J. A molecular perspective of CTLA-4 function. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:65–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marelli-Berg FM, Okkenhaug K, Mirenda V. A two-signal model for T cell trafficking. Trends Immunol. 2007;28:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2007.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Asseman C, Read S, Powrie F. Colitogenic Th1 cells are present in the antigen-experienced T cell pool in normal mice: Control by CD4+ regulatory T cells and IL-10. J Immunol. 2003;171:971–978. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.