This review provides a brief description of the development of oral fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy regimens and summarizes the results of clinical studies of tegafur plus uracil in breast cancer conducted in Japan, leading to the identification of patients most likely to benefit from treatment with this oral 5-fluorouracil.

Keywords: Breast neoplasm, Fluorouracil, Tegafur–Uracil, Drug, Chemotherapy, Adjuvant, Japan

Abstract

In Japan, the history of postoperative chemotherapy for breast cancer started with 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), launched in the 1980s. Currently, oral fluoropyrimidine–based regimens indicated for the treatment of breast cancer in Japan include tegafur plus uracil (UFT); tegafur, gimeracil, and oteracil (TS-1); doxifluridine; and capecitabine. In particular, UFT represents an important option for long-term treatment because of minimal adverse events and the potential for long-term maintenance of effective plasma concentrations of 5-FU to inhibit micrometastasis after surgery. Therefore, various clinical studies of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with UFT have been conducted in patients with completely resected tumors. Recent studies have shown that UFT prolongs survival after tumor resection in patients with gastric cancer, colorectal cancer, and lung cancer. In patients with breast cancer, large clinical trials of UFT-based postoperative chemotherapy conducted in Japan have shown that UFT is useful for the treatment of intermediate-risk patients with no lymph node metastasis. This paper reviews the results of clinical studies of UFT conducted in Japan to assess the therapeutic usefulness of this oral 5-FU. The types of patients most likely to benefit from UFT are discussed on the basis of currently available evidence and a global consensus of treatment recommendations. The optimal timing of endocrine therapy and strategies for postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with UFT in patients with breast cancer are also discussed.

Introduction

One global standard for the selection of postoperative therapy for breast cancer is derived from the risk category–based recommendations proposed by expert panels at the St. Gallen oncology consensus conferences [1]. Treatment guidelines issued and regularly updated by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network [2] and the American Society of Clinical Oncology [3] also play important roles in deciding on the best regimen for postoperative therapy.

Among chemotherapeutic agents, bolus injections of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) are included mainly in combination chemotherapy regimens, such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF) or fluorouracil, epirubicin, and cyclophosphamide (FEC). At present, the positioning of 5-FU varies considerably, even in Europe and North America.

In Japan, clinical studies of chemotherapeutic regimens including oral 5-FU derivatives date back many years, and as a consequence, unique regimens of postoperative chemotherapy have been developed in Japan. In particular, long-term, daily oral treatment with tegafur plus uracil (UFT) as postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy was recently shown to prolong survival in patients with gastric [4], colorectal [5], and lung [6] cancer. To assess the usefulness of postoperative chemotherapy with UFT in breast cancer, the Adjuvant Chemoendocrine Therapy for Breast Cancer (ACETBC) study, the first large clinical trial of its type to be conducted in Japan, was performed [7, 8]. In addition, large controlled clinical studies have been conducted to compare UFT with CMF [9–11]. This review provides a brief description of the development of oral fluoropyrimidine chemotherapy regimens and summarizes the results of clinical studies of UFT in breast cancer conducted in Japan, leading to the identification of patients most likely to benefit from treatment with this oral 5-FU.

Evolution of Oral Fluoropyrimidines for Breast Cancer Chemotherapy

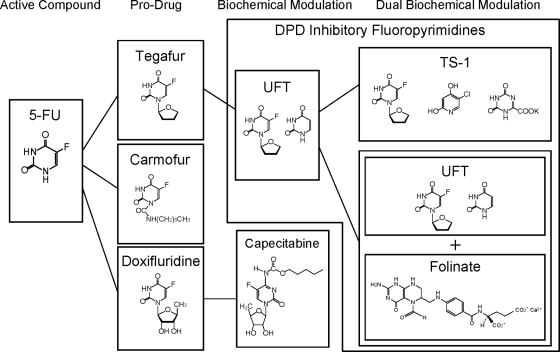

More than 50 years have elapsed since 5-FU was developed by Heidelberger et al. [12] in 1957, and during this time, 5-FU has been used as a standard therapy for solid tumors. 5-FU is an analog of uracil with antitumor activity that can be attributed to two main actions [13]. After entering cells, 5-FU is converted to 5-fluorodeoxyuridine monophosphate, which inhibits thymidylate synthase (TS), thus interfering with DNA synthesis, as well as to 5-fluorouridine triphosphate, which is incorporated into RNA, inhibiting normal RNA processing. An important limitation of 5-FU is its prompt degradation and inactivation by dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase (DPD) in vivo. To address this disadvantage and to enhance its effectiveness, better treatment regimens and 5-FU derivatives and modulators have been developed. The evolution of oral fluoropyrimidine derivatives for breast cancer is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Outline of the evolution of oral 5-fluorouracil–based treatments in Japan. Abbreviations: 5-FU, 5-fluorouracil; DPD, dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase; TS-1, tegafur, gimeracil, and oteracil; UFT, tegafur plus uracil.

One strategy to improve the efficacy of fluoropyrimidines is to concurrently administer agents that inhibit the DPD-dependent degradation of 5-FU such that blood levels of 5-FU are higher than the levels achieved by continuous i.v. administration of 5-FU. The fluoropyrimidines developed under this strategy include UFT and a combination of gimerasil, tegafur, and oteracil (TS-1), which are designated as DPD-inhibitory fluoropyrimidines. A second strategy is to selectively enhance the concentration of 5-FU in tumor tissues, by making use of thymidine phosphorylase (TP), which is expressed at high levels in tumor tissues. The fluoropyrimidines developed under this strategy include doxifluridine (5′-deoxy-5-fluorouridine [5′-DFUR]) and capecitabine.

DPD-Inhibitory Fluoropyrimidines

UFT

UFT is a combined preparation of uracil and tegafur. Tegafur was initially synthesized in 1967 as a prodrug of 5-FU and is converted in the liver to 5-FU by cytochrome P450 2A6. Oral regimens have been developed on the basis of these properties [14–16]; however, 5-FU derived from tegafur is promptly metabolized by DPD in the liver, similar to i.v. 5-FU. Thus, tegafur was combined with uracil to inhibit DPD and increase concentrations of 5-FU in vivo, thereby enhancing its antitumor activity. Increasing amounts of uracil are associated with higher toxicity as well as efficacy, and to maintain an optimal balance between efficacy and toxicity, tegafur and uracil were combined in a molar ratio of 1:4 in the preparation of UFT [17]. In addition to the cytocidal effects of 5-FU on residual cancer cells after surgery, UFT may also act through the antiangiogenic activity of the tegafur metabolites γ-hydroxybutyrate (GHB) and γ-butyrolactone (GBL) [18, 19].

TS-1

To achieve higher antitumor activity than UFT with lower toxicity, potent DPD inhibitors and drugs capable of reducing toxicity were investigated. Gimeracil is a DPD inhibitor with about 200-fold more potency than uracil. Oteracil is an agent that was shown to suppress the activation of 5-FU mainly in the gastrointestinal tract, thereby decreasing 5-FU–induced gastrointestinal toxicity. To achieve a balance between efficacy and toxicity, optimal combination ratios of tegafur with these two agents were studied, and this led to the development of TS-1, combining gimeracil, oteracil, and tegafur in a molar ratio of 1:0.4:1 [20].

TP-Dependent Fluoropyrimidines

5′-DFUR

5′-DFUR is a prodrug of 5-FU that was developed to enhance tumor selectivity [21]. This drug is converted into 5-FU by TP, an enzyme that is highly expressed in tumor tissue. Because 5-FU is produced in situ by TP in tumor tissue, 5′-DFUR is considered to have high tumor selectivity. However, TP is also expressed to some extent in normal tissue, for example, in the intestinal tract. Therefore, long-term/high-dose treatment with 5′-DFUR carries a high risk for intestinal toxicity and bone marrow suppression, both of which are dose-limiting factors.

Capecitabine

Capecitabine was developed as a prodrug to overcome the disadvantages of 5′-DFUR and has even higher tumor-selective activity based on the restriction of metabolizing enzymes to tumor tissue, and absence from the intestine or marrow [22]. In order to reduce the risk for bone marrow suppression, 5′-deoxy-5-fluorocytidine, a derivative that is converted into 5′-DFUR by cytidine deaminase, was synthesized. To inhibit intestinal toxicity, capecitabine, a derivative that is converted into 5′-DFUR by carboxyl esterase, was developed. Capecitabine is associated with hand–foot syndrome, a dose-limiting toxicity that rarely occurred with previously developed drugs. Symptomatic treatment for hand–foot syndrome is now being studied [23].

Evidence Supporting the Usefulness of Oral Fluoropyrimidine Derivatives as Postoperative Adjuvant Chemotherapy for Breast Cancer

Usefulness Compared with Surgery Alone

In Japan, the first clinical study of oral fluoropyrimidine derivatives in patients with breast cancer was conducted in 1982, when the ACETBC Study Group was formed. The ACETBC Study Group divided Japan into several areas and planned and conducted different clinical trials in each area. The Study Group also conducted a series of major trials, designated as the first to fourth studies [7, 8, 24, 25]. The results of a pooled analysis of clinical studies performed according to similar concepts were reported in addition to the results of individual clinical studies conducted in each area. These studies represent the largest clinical trials of oral anticancer agents in the world to date.

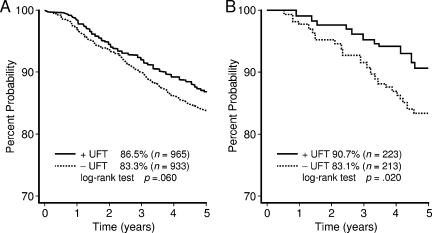

In the third ACETBC study, tegafur, which had been evaluated in previous studies, was switched to UFT, and patients were stratified according to estrogen receptor (ER) status (Fig. 2) [7]. While tamoxifen (TAM) plus UFT was compared with TAM alone in patients with ER+ breast cancer, UFT was compared with no chemotherapy in patients with ER− breast cancer. In 854 ER+ patients, mitomycin was additionally administered on the day of surgery. In total, 1,973 patients were enrolled and included in the analysis. Examination of the recurrence-free survival (RFS) rate revealed that the risk for recurrence was 21% lower in the UFT group. Thus, in ER+ breast cancer, 2 years of treatment with UFT plus TAM led to a 26% lower risk for recurrence than with TAM alone. Regarding the results of studies conducted in different areas of Japan, Ogita et al. [26] compared TAM alone with TAM plus UFT as postoperative chemotherapy in patients with ER+ stage II breast cancer. The disease-free survival (DFS) rate at 5 years was 83.1% in the TAM alone group and 90.7% in the TAM plus UFT group (p = .02). Additional treatment with UFT thus resulted in a significantly longer DFS interval. Sugimachi et al. [27] similarly showed that adding UFT to TAM was markedly effective in premenopausal women with ER+ breast cancer (p < .05). Toi et al. [28] examined the characteristics of tumors from patients who responded well to UFT, using surgical specimens obtained from patients enrolled in the third ACETBC study. They also studied the association between factors such as 5-FU–metabolizing enzymes and outcomes, using specimens obtained from 192 premenopausal women with node-positive breast cancer. Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER-2) and p53 were found to be clear prognostic indicators of response to TAM alone, whereas response to TAM plus UFT was not influenced by the expression status of HER-2 or TP. Among patients with tumors that expressed TS, outcomes were distinctly better in the TAM plus UFT group than in the TAM alone group.

Figure 2.

Five-year DFS rates in the third ACETBC trial evaluating mitomycin and tamoxifen with or without UFT. (A): All eligible cases. (B): DFS curve in ER+ patients in the Hokkaido region of the third ACETBC study.

Abbreviations: ACETBC, Adjuvant Chemoendocrine Therapy for Breast Cancer; DFS, disease-free survival; ER, estrogen receptor; UFT, tegafur plus uracil.

Modified from Kasumi F, Yoshimoto M, Uchino J et al. Meta-analysis of five studies on tegafur plus uracil (UFT) as post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Oncology 2003;64:146–153, with permission of S. Karger AG, Basel; and from Ogita M, Uchino J, Asaishi K et al. Efficacy of UFT plus tamoxifen for estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer and tamoxifen plus UFT for estrogen-receptor-negative breast cancer: Adjuvant therapy after administration of mitomycin. Clin Drug Investig 2003;23:689–699, with permission.

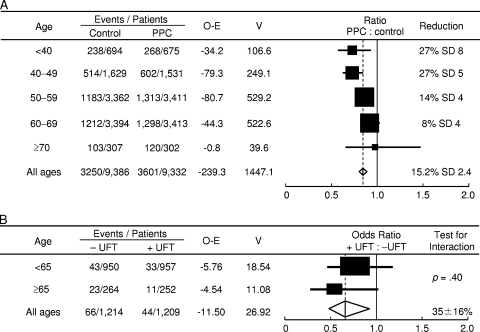

The fourth ACETBC study evaluated the usefulness of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with UFT in patients with node-negative breast cancer (Fig. 3) [8, 29]. Data were collected from 2,932 patients. The 5-year survival rate differed significantly between patients who received UFT and those who did not (95.9% versus 94.0%; p = .036). When patients were stratified according to ER status, the 5-year survival rate among patients with ER+ breast cancer was 93.5% with surgery alone, 96.0% with UFT alone, 96.9% with TAM alone, and 98.0% with TAM plus UFT. Among patients with ER− breast cancer, the 5-year survival rate was 93.2% with surgery alone, 95.8% with UFT alone, 93.9% with TAM alone, and 92.8% with TAM plus UFT. These results strongly suggested that adding UFT to TAM leads to longer survival in women with ER+ breast cancer. The studies described above provided evidence that adding UFT to TAM strongly enhances response, particularly in patients with ER+ tumors.

Figure 3.

Proportional risk reductions with adjuvant chemotherapy according to age at randomization. (A): Results of the EBCTCG analysis indicate that there was a significant trend toward a lower risk for mortality in older, compared with younger, women mainly treated with CMF-based polychemotherapy. (B): In contrast, data from the fourth ACETBC trial suggest that age at diagnosis does not significantly impact treatment benefit from UFT.

Abbreviations: ACETBC, Adjuvant Chemoendocrine Therapy for Breast Cancer; EBCTCG, Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group; O-E, observation-expectation; PPC, polychemotherapy; SD, standard deviation; UFT, tegafur plus uracil; V, variance.

Modified from Polychemotherapy for early breast cancer: An overview of the randomised trials. Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Lancet 1998;352:930–942, with permission; and from Noguchi S, Koyama H, Uchino J et al. Postoperative adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen, tegafur plus uracil, or both in women with node-negative breast cancer: A pooled analysis of six randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2172–2184, with permission.

The Doxifluridine Study Group evaluated the usefulness of postoperative 5′-DFUR treatment versus surgery alone in 1,217 patients with primary breast cancer [30]. Eight-year follow-up data showed that the RFS and overall survival (OS) rates did not differ significantly between the two groups.

Usefulness Compared with CMF

In Japan, clinical trials of CMF were started considerably later than in Europe and North America, and CMF was approved in 1996. Subsequently, CMF was given to control groups in clinical trials performed throughout Japan.

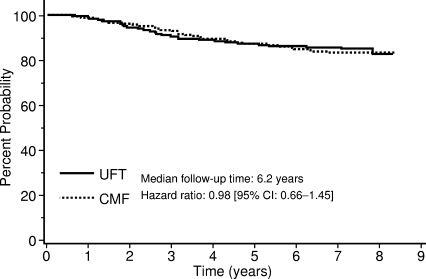

The National Surgical Adjuvant Study of Breast Cancer (N-SAS-BC) study 01 [11] was designed to verify that UFT is not inferior to CMF in intermediate-risk patients with node-negative breast cancer. Two years of treatment with UFT was compared with six cycles of classic CMF, with RFS as the endpoint. Patients whose tumors were positive for ER, progesterone receptor, or both, additionally received TAM (20 mg/day) for 5 years. In total, 733 patients were enrolled. The hazard ratio in the UFT group as compared with the CMF group was 0.98 (95% confidence interval, 0.66–1.45) (Fig. 4). Although UFT was not established as being noninferior to CMF, the RFS and OS curves of the groups overlapped during the study period, strongly suggesting that UFT and CMF are equally effective in these patients.

Figure 4.

Relapse-free survival time for patients treated with UFT or CMF participating in the N-SAS-BC 01 trial.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CMF, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil; N-SAS-BC, National Surgical Adjuvant Study of Breast Cancer; UFT, tegafur plus uracil.

Modified from Watanabe T, Sano M, Takashima S et al. Oral uracil and tegafur compared with classic cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluorouracil as postoperative chemotherapy in patients with node-negative, high-risk breast cancer: National Surgical Adjuvant Study for Breast Cancer 01 Trial. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1368–1374, with permission.

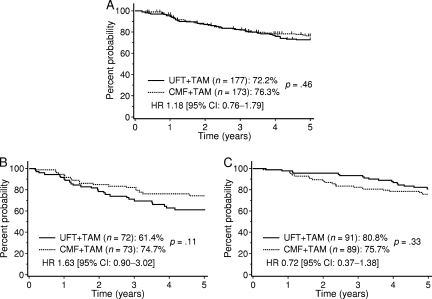

The Comparative Trial with UFT + TAM and CMF + TAM in Adjuvant Therapy for Breast Cancer [9, 10] was conducted during the same period as the N-SAS-BC 01 study to verify that UFT is noninferior to CMF in patients who had stage I to IIIa breast cancer with one to nine axillary node metastases. That study compared six cycles of CMF plus 2 years of TAM with UFT plus TAM for 2 years. Data from 377 enrolled patients were analyzed. RFS rates at 5 years were similar in the CMF group (76.3%) and the UFT group (72.3%). A subanalysis was performed according to hormone-receptor status (Fig. 5). In patients with ER+ breast cancer, the 5-year DFS rate was 75.7% in the CMF group and 80.8% in the UFT group, indicating that 2-year treatment with UFT plus TAM is superior to six cycles of CMF plus 2 years of TAM (hazard ratio, 0.72). In the study, there was a trend toward an interaction between the treatment response in each group and ER expression status (p = .07). When the response in the UFT group was stratified according to ER status, the 5-year DFS rate was 80.8% in ER+ patients and 61.4% in ER− patients, indicating that the efficacy of postoperative chemotherapy with UFT markedly differed depending on ER expression status (p = .002). Incidentally, Inaji et al. [31] conducted a clinical study comparing low-dose cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and 5-FU (CAF) with UFT plus TAM in patients with four or more lymph node metastases. The 5-year survival rate was higher in patients given UFT plus TAM (82.1% versus 66.2%; p = .04).

Figure 5.

Five-year relapse-free survival rate in patients taking part in the CUBC trial. (A): All eligible cases. (B): ER− cases. (C): ER+ cases.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; CMF, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil; CUBC, Comparative Trial with UFT + TAM and CMF + TAM in Adjuvant Therapy for Breast Cancer; ER, estrogen receptor; HR, hazard ratio; UFT, tegafur plus uracil.

Modified from Takatsuka Y, Park Y, Okamura K et al. Relationship between estrogen receptor (ER) status and efficacy of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with oral tegafur uracil (UFT) or CMF subset analysis from a randomized controlled trial (CUBC trial in Japan) [poster session at EBCC]. Eur J Cancer Suppl 2008;6:117–118.

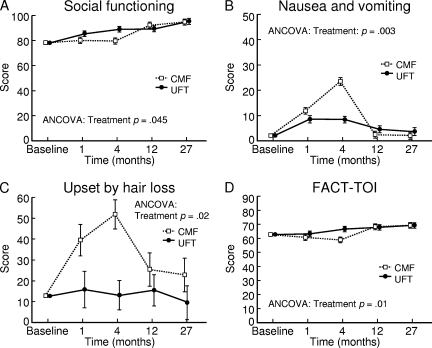

Oral 5-FU derivatives are known to have few adverse events, such as gastrointestinal symptoms, bone marrow suppression, and hair loss. Clinical trials have shown similar trends for UFT. In particular, the N-SAS-BC 01 study evaluated common adverse events and patient quality of life (QOL) using a number of different questionnaires: the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC) Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30, EORTC Breast Cancer–Specific QLQ-Breast 23, and Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Breast (Fig. 6). Analysis of the results of these questionnaires indicated that QOL was distinctly better in the UFT group for the first half year after starting treatment with CMF. After completing treatment with CMF, QOL improved slightly in the CMF group, but was similar to that in the UFT group, suggesting that QOL was well maintained during treatment with UFT.

Figure 6.

Impact of UFT or CMF on QOL in patients taking part in the N-SAS-BC 01 trial. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 Breast 23 scores for social functioning (A), nausea and vomiting (B), and upset by hair loss (C). In the graph for social functioning, a higher score indicates better QOL, whereas for nausea and vomiting and upset by hair loss, lower scores indicate better QOL. (D): FACT-TOI. A higher score indicates better QOL. Data are presented as mean ± standard error.

Abbreviations: ANCOVA, analysis of covariance; CMF, cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and 5-fluorouracil; FACT-TOI, Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy–Breast Total Outcome Index; N-SAS-BC, National Surgical Adjuvant Study of Breast Cancer; QOL, quality of life; UFT, tegafur plus uracil.

Modified from Watanabe T, Sano M, Takashima S et al. Oral uracil and tegafur compared with classic cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluorouracil as postoperative chemotherapy in patients with node-negative, high-risk breast cancer: National Surgical Adjuvant Study for Breast Cancer 01 Trial. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1368–1374, with permission.

Discussion

With recent advances in pharmacotherapy, the initial treatment of breast cancer has shifted from primarily surgery to a multidisciplinary approach. In particular, postoperative chemotherapy has changed dramatically as a result of the numerous randomized controlled studies performed during the approximately 30 years since CMF was first shown to be therapeutically useful. Updated guidelines have been prepared on the basis of the large body of evidence generated by these studies to help clinicians make decisions regarding treatment.

The first study in Japan to prospectively assess the benefits of postoperative chemotherapy in breast cancer was a randomized controlled trial performed by the ACETBC Study Group [24]. That trial (the first ACETBC study) evaluated the potential benefits of adding TAM to tegafur in women with breast cancer. Subsequently, many randomized controlled studies comparing oral 5-FU derivatives with classic CMF therapy, which was approved in Japan in 1996, were planned and executed, leading to the introduction in Japan of regimens used as standard therapy in Europe and North America.

Anthracycline-based regimens are currently recommended for postoperative chemotherapy in women with breast cancer. In patients with node-positive disease, anthracycline-based regimens combined with taxanes, given either sequentially or concurrently, are recommended. The use of TAM or aromatase inhibitors (AIs) is recommended for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor–positive tumors, but the use of AIs is increasing.

If both chemotherapy and endocrine therapy are indicated for postoperative treatment, the optimal timing of such therapy, that is, whether treatment should be given sequentially or concomitantly, must be considered. An Intergroup 0100/Southwest Oncology Group 8814 trial [32], which was conducted to determine whether CAF in combination with TAM should be administered sequentially or concurrently, demonstrated the superiority of sequential treatment. On the basis of these results, sequential treatment with hormones after the completion of postoperative chemotherapy is currently considered therapeutically useful and is thus recommended. However, there is a conspicuous lack of evidence supporting the timing of chemotherapy with drugs other than anthracyclines, such as the subsequently launched taxanes and oral 5-FU derivatives, and the timing of treatment with AIs, currently the hormone therapy of choice for postmenopausal women.

Historically, there was a time when oral 5-FU derivatives and TAM were used concomitantly for no clear reason. However, such combined regimens are already used in clinical practice and have been reported to be therapeutically useful. Recently, experimental studies demonstrating the usefulness of 5-FU derivatives combined with TAM have been reported. In studies using a breast cancer cell line, Kubota et al. [33] showed that concurrent treatment with UFT and TAM is markedly effective because of a TAM-induced ER downregulation. UFT was thus shown to potentiate the hormone activity of TAM. Another study reported that a combination of 4-hydroxy-TAM and 5-FU has additive anticancer activity [34]. The mechanism of action of combined treatment is thought to involve the TAM-induced TS downregulation. This downregulation of TS activity is considered to enhance the antitumor activity of 5-FU. The activity of a combination of UFT and anastrozole has also been studied using cell lines after aromatase gene introduction. Combined treatment was confirmed to result in significantly greater tumor shrinkage than with either treatment alone. UFT has been shown to significantly improve outcomes over with surgery alone in clinical studies. Its effectiveness is estimated to be comparable with that of CMF. Moreover, the addition of UFT to TAM has been shown to further improve outcomes. Interestingly, the third ACETBC study reported that the degree of TS activity, considered a useful predictor of response to 5-FU, was related to the response to UFT plus TAM [28]. Namely, there was no difference in RFS between a TAM alone group and a TAM plus UFT group among patients whose tumors had low TS activity, whereas the RFS interval was longer in the TAM plus UFT group among patients whose tumors had high TS activity.

Early data were all obtained from studies in which UFT was combined with TAM. However, as mentioned above, AIs are increasingly being used as standard treatment in postmenopausal women with breast cancer. Endocrine therapy is indicated for the treatment of hormone receptor–positive breast cancer, which generally has low sensitivity to chemotherapy [35, 36]. Recently, AI-based endocrine therapy combined with chemotherapy was reported to be therapeutically useful. Experimental studies by Chen et al. [37] using aromatase-positive gynecological tumors assessed the effectiveness of a combination of paclitaxel and exemestane in vitro. The activity of paclitaxel was potentiated by concurrent treatment with exemestane. The mechanism of action was reported to independently involve ER-α, but to depend on the presence of androstenedione. Clinically, the results of phase II randomized controlled studies comparing letrozole monotherapy with a combination of letrozole and cyclophosphamide as preoperative treatment in women with ER+ breast cancer have been reported [38]. Combined therapy resulted in a higher response rate. The high antitumor effectiveness in that clinical trial was attributed to metronomic administration of cyclophosphamide (50 mg orally every day). Inhibition of angiogenesis by metronomic treatment with cyclophosphamide is considered one of the mechanisms of action [39]. Experimental studies have confirmed that UFT also similarly inhibits angiogenesis [18, 19]. In other words, GHB and GBL derived from tegafur are thought to inhibit angiogenesis. This effect may underlie the high antitumor activity of long-term metronomic treatment with UFT [40]. Therefore, long-term continued administration of UFT might continuously inhibit the development of feeding blood vessels to tumors, thereby suppressing postoperative metastasis.

Although concurrent therapy with UFT and AIs is not supported by firm evidence from clinical trials, concomitant treatment with these drugs has already been reported in clinical and experimental practice. In a survey designed primarily to confirm tolerance to 1 year of postoperative treatment with UFT, 273 patients concurrently received UFT and anastrozole among 1,995 patients in whom the safety of UFT could be assessed for 1 year between 2002 and 2005 [41]. In the same survey, 398 patients received UFT alone and 127 patients received UFT in combination with TAM. Safety analyses of these three groups of patients confirmed that combined treatment was adequately tolerated. As for treatment response, experimental studies have shown that a combination of UFT and anastrozole has higher antitumor activity than either drug alone (data not shown). Available evidence thus suggests that UFT in combination with either TAM or anastrozole is one option for the postoperative management of breast cancer.

The 2007 St. Gallen Consensus Report recommended the use of endocrine therapy regardless of risk in patients with HER-2−, hormone receptor–positive breast cancer [42]. The report also recommended that patients at intermediate risk should receive endocrine monotherapy or sequentially receive chemotherapy followed by endocrine therapy. Given the balance between treatment effectiveness and QOL, this is the most difficult category of patients. Important questions include: What types of patients should also receive chemotherapy and what is the best strategy to improve treatment efficacy? To address these points, Berry et al. [43] analyzed data from the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB)-8541, CALGB-9344, and CALGB-9741 studies, in which survival benefit in patients with node-positive breast cancer was evaluated according to ER status. The DFS interval was clearly longer with high-dose regimens, additional treatment with paclitaxel, and high dose density in patients with ER− breast cancer. In contrast, in patients with ER+ breast cancer, the effectiveness of such treatment was about one third to one half of that in patients with ER− breast cancer. In Japan, the Japan Breast Cancer Research Group 01 study assessed the effectiveness of preoperative chemotherapy with FEC followed by docetaxel according to ER and HER-2 status [44]. Although the rate of pathological complete response to preoperative chemotherapy was 67% in patients with ER−HER-2+ tumors, it was only 13% in those with ER+HER-2− tumors. Recently, many studies have thus shown that hormone receptor–positive, HER-2− breast cancer has a low sensitivity to chemotherapy, regardless of whether it is given preoperatively or postoperatively [45].

In patients at intermediate risk, sensitivity to chemotherapy is thus low, particularly for hormone receptor–positive, HER-2− tumors. Moreover, there are no clear-cut indices for clinically deciding whether endocrine therapy should be given alone or combined with chemotherapy. It is thus often difficult to decide which treatment is indicated in individual patients. For example, a patient may be upgraded from low risk to intermediate risk because of a change in only one of the factors defining intermediate risk; the resulting additional postoperative chemotherapy may be intensive and will almost invariably cause transient hair loss and various other adverse events, which may be severe, resulting in markedly comprised patient QOL. Another reason for difficulty in treatment selection is that intensive i.v. chemotherapy may be unsuitable for some patients, such as those who are elderly or have comorbidities. If regimens that are effective and better tolerated than conventionally used i.v. chemotherapy were available, such treatment might be suitable for these patients. Oral 5-FU derivatives are powerful drugs that can solve these problems. UFT in combination with TAM or anastrozole is considered one treatment option.

Similar to UFT, 5′-DFUR was evaluated as postoperative chemotherapy primarily in Japan, but was not shown to be therapeutically useful, as compared with surgery alone. The CALGB-49907 study [46] in elderly patients compared capecitabine with CMF or doxorubicin plus cyclophosphamide. That study also failed to show that capecitabine was therapeutically useful. However, the study did demonstrate an interaction between hormone-receptor status and treatment response, suggesting that the response to oral 5-FU derivatives is somehow related to hormone-receptor status. The failure to demonstrate the usefulness of these drugs for the postoperative treatment of breast cancer can be attributed to several reasons, including the short treatment period (generally 2 years in clinical studies of UFT) and the timing of hormone therapy (concurrent treatment with TAM in all clinical studies of UFT). Furthermore, because capecitabine and 5′-DFUR are activated by thymidylate phosphorylase in tumors, these drugs may not have been adequately effective in a postoperative environment associated with micrometastases and virtually no tumor.

As stated above, it is extremely important to select treatments that respect patients' desires. Postoperative chemotherapy should therefore not only be chosen on the basis of hormone-receptor and HER-2 status, but should also include an assessment of various other factors, such as age and comorbidities. At present, large international clinical studies are in progress with the ultimate goal of individualizing therapy. Such studies are assessing the value of prognostic tools such as oncotype DX® in the Trial Assigning Individualized Options for Treatment (TAILORx) and MammaPrint® in the Microarray in Node-Negative and 1 to 3 Positive Lymph Node Disease May Avoid Chemotherapy (MINDACT) trial. Unique clinical trials in Japan include the N-SAS-BC 06 study (New Primary Endocrine Therapy Origination Study, NEOS), which is now evaluating the add-on effect of chemotherapy on outcomes in patients who have stable disease or a better response to preoperative hormone therapy. The results of these clinical trials are expected to lead to better delineation of patients most likely to benefit from intensive chemotherapy and those who are unlikely to benefit, among patients in the controversial category of intermediate risk. Clinical trials of drugs targeting new molecules are also currently in progress and will hopefully lead to the development of new prognostic biomarkers of treatment response or outcomes.

In conclusion, UFT has been suggested to be therapeutically useful in combination with TAM or AIs. The use of these drugs in selected patients most likely to benefit from treatment is expected to result in high therapeutic effectiveness, without comprising patients' QOL. UFT combined with TAM or AIs is thus considered an important treatment option permitting optimal therapy in individual patients.

Acknowledgments

English language assistance was provided by Wolters Kluwer Pharma Solutions on behalf of Taiho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd.

Author Contributions

Manuscript writing: Takahiro Nakayama

Final approval of manuscript: Takahiro Nakayama, Shinzaburo Noguchi

Roderick McNab, Ph.D., University of Aberdeen, U.K. provided English language assistance, provided by Wolters Kluwer Pharma Solutions.

References

- 1.Goldhirsch A, Wood WC, Gelber RD, et al. Progress and promise: Highlights of the international expert consensus on the primary therapy of early breast cancer 2007. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1133–1144. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Breast Cancer. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology [Online practice guidelines], 2008. [accessed May 7, 2009]. Available at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/breast.pdf.

- 3.American Society of Clinical Oncology. Clincal Practice Guidelines. [accessed May 7, 2009]. Available at http://www.asco.org/ASCOv2/Practice+%26+Guidelines/Guidelines/Clinical+Practice+Guidelines/Breast+Cancer.

- 4.Nakajima T, Kinoshita T, Nashimoto A, et al. Randomized controlled trial of adjuvant uracil-tegafur versus surgery alone for serosa-negative, locally advanced gastric cancer. Br J Surg. 2007;94:1468–1476. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akasu T, Moriya Y, Ohashi Y, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with uracil-tegafur for pathological stage III rectal cancer after mesorectal excision with selective lateral pelvic lymphadenectomy: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2006;36:237–244. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyl014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kato H, Ichinose Y, Ohta M, et al. A randomized trial of adjuvant chemotherapy with uracil-tegafur for adenocarcinoma of the lung. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1713–1721. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasumi F, Yoshimoto M, Uchino J, et al. Meta-analysis of five studies on tegafur plus uracil (UFT) as post-operative adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. Oncology. 2003;64:146–153. doi: 10.1159/000067763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noguchi S, Koyama H, Uchino J, et al. Postoperative adjuvant therapy with tamoxifen, tegafur plus uracil, or both in women with node-negative breast cancer: A pooled analysis of six randomized controlled trials. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2172–2184. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.02.158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takatsuka Y, Park Y, Okamura K, et al. Relationship between estrogen receptor (ER) status and efficacy of postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy with oral tegafur uracil (UFT) or CMF subset analysis from a randomized controlled trial (CUBC trial in Japan) [abstract 235] Eur J Cancer Suppl. 2008;6:117–118. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park Y, Okamura K, Mitsuyama S, et al. Uracil tegafur and tamoxifen vs cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluorouracil, and tamoxifen in post operative adjuvant therapy for stage I, II, or IIIA lymph node-positive breast cancer: A comparative study. Br J Cancer. 2009;101:598–604. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watanabe T, Sano M, Takashima S, et al. Oral uracil and tegafur compared with classic cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, fluorouracil as postoperative chemotherapy in patients with node-negative, high-risk breast cancer: National Surgical Adjuvant Study for Breast Cancer 01 Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1368–1374. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.3939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Heidelberger C, Chaudhuri NK, Danneberg P, et al. Fluorinated pyrimidines, a new class of tumour-inhibitory compounds. Nature. 1957;179:663–666. doi: 10.1038/179663a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chaudhuri NK, Montag BJ, Heidelberger C. Studies on fluorinated pyrimidines. III. The metabolism of 5-fluorouracil-2-C14 and 5-fluoroorotic-2-C14 acid in vivo. Cancer Res. 1958;18:318–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Giller SA, Zhuk RA, Lidak M. [Analogs of pyrimidine nucleosides. I. N1-(alpha-furanidyl) derivatives of natural pyrimidine bases and their antimetabolites] Dokl Akad Nauk SSSR. 1967;176:332–335. In Russian. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ikeda K, Yoshisue K, Matsushima E, et al. Bioactivation of tegafur to 5-fluorouracil is catalyzed by cytochrome P-450 2A6 in human liver microsomes in vitro. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:4409–4415. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Toide H, Akiyoshi H, Minato Y, et al. Comparative studies on the metabolism of 2-(tetrahydrofuryl)-5-fluorouracil and 5-fluorouracil. Gann. 1977;68:553–560. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fujii S, Kitano S, Ikenaka K, et al. Effect of coadministration of uracil or cytosine on the anti-tumor activity of clinical doses of 1-(2-tetrahydrofuryl)-5-fluorouracil and level of 5-fluorouracil in rodents. Gann. 1979;70:209–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Basaki Y, Chikahisa L, Aoyagi K, et al. γ-Hydroxybutyric acid and 5-fluorouracil, metabolites of UFT, inhibit the angiogenesis induced by vascular endothelial growth factor. Angiogenesis. 2001;4:163–173. doi: 10.1023/a:1014059528046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yonekura K, Basaki Y, Chikahisa L, et al. UFT and its metabolites inhibit the angiogenesis induced by murine renal cell carcinoma, as determined by a dorsal air sac assay in mice. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:2185–2191. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shirasaka T, Shimamato Y, Ohshimo H, et al. Development of a novel form of an oral 5-fluorouracil derivative (S-1) directed to the potentiation of the tumor selective cytotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil by two biochemical modulators. Anticancer Drugs. 1996;7:548–557. doi: 10.1097/00001813-199607000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ishitsuka H, Miwa M, Takemoto K, et al. Role of uridine phosphorylase for antitumor activity of 5′-deoxy-5-fluorouridine. Gann. 1980;71:112–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miwa M, Ura M, Nishida M, et al. Design of a novel oral fluoropyrimidine carbamate, capecitabine, which generates 5-fluorouracil selectively in tumours by enzymes concentrated in human liver and cancer tissue. Eur J Cancer. 1998;34:1274–1281. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(98)00058-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S, Lee S, Chun Y, et al. Pyridoxine is not effective for the prevention of hand foot syndrome (HFS) associated with capecitabine therapy: Results of a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled study [abstract 9007] Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2007;25:494S. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.29.1807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abe O. The role of chemoendocrine agents in postoperative adjuvant therapy for breast cancer: Meta-analysis of the first collaborative studies of postoperative adjuvant chemoendocrine therapy for breast cancer (ACETBC) Breast Cancer. 1994;1:1–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02967368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoshida M, Abe O, Uchino J, et al. Meta-analysis of the second collaborative study of adjuvant chemoendocrine therapy for breast cancer (ACETBC) in patients with stage II, estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer. Breast Cancer. 1997;4:93–101. doi: 10.1007/BF02967062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ogita M, Uchino J, Asaishi K, et al. Efficacy of UFT plus tamoxifen for estrogen-receptor-positive breast cancer and tamoxifen plus UFT for estrogen-receptor-negative breast cancer: Adjuvant therapy after administration of mitomycin. Clin Drug Investig. 2003;23:689–699. doi: 10.2165/00044011-200323110-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sugimachi K, Maehara Y, Akazawa K, et al. Postoperative chemo-endocrine treatment with mitomycin C, tamoxifen, and UFT is effective for patients with premenopausal estrogen receptor-positive stage II breast cancer. Nishinihon Cooperative Study Group of Adjuvant Therapy for Breast Cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 1999;56:113–124. doi: 10.1023/a:1006221425652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Toi M, Ikeda T, Akiyama F, et al. Predictive implications of nucleoside metabolizing enzymes in premenopausal women with node-positive primary breast cancer who were randomly assigned to receive tamoxifen alone or tamoxifen plus tegafur-uracil as adjuvant therapy. Int J Oncol. 2007;31:899–906. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Early Breast Cancer Trialists' Collaborative Group. Polychemotherapy for early breast cancer: An overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 1998;352:930–942. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tominaga T, Toi M, Abe O, et al. The effect of adjuvant 5′-deoxy-5-fluorouridine in early stage breast cancer patients: Results from a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Int J Oncol. 2002;20:517–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Inaji H, Sakai K, Oka T, et al. [A randomized controlled study comparing uracil-tegafur (UFT)+tamoxifen (UFT+TAM therapy) with cyclophosphamide+adriamycin+5-fluorouracil (CAF therapy) for women with stage I, II, or IIIa breast cancer with four or more involved nodes in the adjuvant setting] Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2006;33:1423–1429. In Japanese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Albain KS, Barlow WE, Ravdin PM, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy and timing of tamoxifen in postmenopausal patients with endocrine responsive, node positive breast cancer: A phase 3, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2009;374:2055–2063. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61523-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kubota T, Josui K, Ishibiki K, et al. [Experimental combined chemo- and endocrine therapy with UFT and tamoxifen in human breast carcinoma xenografts serially transplanted into nude mice] Nippon Gan Chiryo Gakkai Shi. 1990;25:2767–2773. In Japanese. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kurebayashi J, Nukatsuka M, Nagase H, et al. Additive antitumor effect of concurrent treatment of 4-hydroxy tamoxifen with 5-fluorouracil but not with doxorubicin in estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer cells. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;59:515–525. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Conforti R, Boulet T, Tomasic G, et al. Breast cancer molecular subclassification and estrogen receptor expression to predict efficacy of adjuvant anthracyclines-based chemotherapy: A biomarker study from two randomized trials. Ann Oncol. 2007;18:1477–1483. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdm209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rouzier R, Pusztai L, Delaloge S, et al. Nomograms to predict pathologic complete response and metastasis-free survival after preoperative chemotherapy for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8331–8339. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.01.2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen D, Hackl W, Ortmann O, et al. Effects of a combination of exemestane and paclitaxel on human tumor cells in vitro. Anticancer Drugs. 2004;15:55–61. doi: 10.1097/00001813-200401000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bottini A, Generali D, Brizzi MP, et al. Randomized phase II trial of letrozole and letrozole plus low-dose metronomic oral cyclophosphamide as primary systemic treatment in elderly breast cancer patients. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3623–3628. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.5773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bertolini F, Paul S, Mancuso P, et al. Maximum tolerable dose and low-dose metronomic chemotherapy have opposite effects on the mobilization and viability of circulating endothelial progenitor cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:4342–4346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Uchida J, Okabe H, Nakano K, et al. Contrasting effects of extended low dose versus standard dose shorter course UFT chemotherapy on microscopic versus macroscopic established tumors: Implications for optimal postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy. Oncol Rep. 2007;18:313–319. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tetsuya T, Shinzaburo N. Safety and compliance with UFT (tegafur and uracil) alone and in combination with hormone therapy in patients with breast cancer [in Japanese] Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 2009;36:1465–1474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Harbeck N, Jakesz R. St Gallen 2007: Breast cancer treatment consensus report. Breast Care. 2007;2:130–134. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berry DA, Cirrincione C, Henderson IC, et al. Estrogen-receptor status and outcomes of modern chemotherapy for patients with node-positive breast cancer. JAMA. 2006;295:1658–1667. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.14.1658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toi M, Nakamura S, Kuroi K, et al. Phase II study of preoperative sequential FEC and docetaxel predicts of pathological response and disease free survival. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008;110:531–539. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9744-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hayes DF, Thor AD, Dressler LG, et al. HER2 and response to paclitaxel in node-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1496–1506. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Muss H, Berry D, Cirrincione C, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy in older women with early stage breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2055–2065. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]