Abstract

We present an infant girl with a de novo interstitial deletion of the chromosome 15q11-q14 region, larger than the typical deletion seen in Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS). She presented with features seen in PWS including hypotonia, a poor suck, feeding problems and mild micrognathia. She also presented with features not typically seen in PWS such as preauricular ear tags, a high arched palate, edematous feet, coarctation of the aorta, a PDA and a bicuspid aortic valve. G-banded chromosome analysis showed a large de novo deletion of the proximal long arm of chromosome 15 confirmed using FISH probes (D15511 and GABRB3). Methylation testing was abnormal and consistent with the diagnosis of PWS. Because of the large appearing deletion by karyotype analysis, an array comparative genomic hybridization (CGH) was performed. A 12.3 Mb deletion was found which involved the 15q11-q14 region containing approximately 60 protein coding genes. This rare deletion was approximately twice the size of the typical deletion seen in PWS and involved the proximal breakpoint BP1 and the distal breakpoint was located in the 15q14 band between previously recognized breakpoints BP5 and BP6. The deletion extended slightly distal to the AVEN gene including the neighboring CHRM5 gene. There is no evidence that the genes in the 15q14 band are imprinted; therefore, their potential contribution in this patient's expanded Prader-Willi syndrome phenotype must be a consequence of dosage sensitivity of the genes or due to altered expression of intact neighboring genes from a position effect.

Keywords: de novo interstitial 15q11-q14 deletion, expanded PWS phenotype, array CGH, genotype-phenotype correlations

Introduction

Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS; OMIM 17270) is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder occurring at a frequency of 1/10,000 – 1/20,000 births and is the leading genetic cause of marked obesity [Butler et al. 2006]. PWS and Angelman syndrome (AS), an entirely different clinical syndrome were the first examples in humans of genomic imprinting or the differential expression of genes depending on the parent of origin. About 99% of PWS and 80% of AS cases have deletions at a common region in chromosome bands, 15q11.2-q13, uniparental disomy of chromosome 15 or imprinting center defects affecting gene expression in this region. Either syndrome is due to genomic abnormalities in each class depending on the parent of origin. Both disorders are characterized by abnormal methylation of imprinted genes in the 15q11-q13 region [Bittel and Butler, 2005]. There are other rare chromosome 15 rearrangements and a few atypical deletions reported in these disorders [Cassidy and Driscoll, 2009].

Human chromosome 15 is one of the most polymorphic chromosomes often implicated in the formation of supernumerary bisatellited chromosomes, deletions, duplications and other rearrangements. Chromosome 15 contains segmental duplications and repeated transcribed DNA sequences (i.e., HERC2 genes) located at the proximal and distal ends of the 15q11-q13 region. The typical deletion of the 15q11-q13 region is the most common cause of PWS and AS presumably due to unequal crossing over in meiosis at repeated sequences located at the ends of the 15q11-q13 region. The typical deletions are of two classes (longer type I and shorter type II) and involve a distal breakpoint (BP3) at the end of the 15q11-q13 region at either of two proximally positioned breakpoints (BP1 or BP2) [see review, Bittel and Butler, 2005]. Using high resolution aCGH testing in a cohort of PWS subjects [Butler et al., 2008], BP1 spanned a region from 18.66 to 20.22 Mb, BP2 from 20.81 to 21.36 Mb and BP3 from 25.94 to 27.29 Mb. The type I deletion ranged in size from 5.72 to 8.15 Mb (mean 6.58) and the type II deletion from 4.77 to 6.44 Mb (mean 5.33). Other breakpoints in the proximal long arm region include BP4 (at about 28 Mb), BP5 (at about 30 Mb) and BP6 (at about 33 Mb), the most distal breakpoint recognized in the proximal 15q region [Pujana et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2004; Mignon-Ravis et al., 2007].

Atypical deletions in Prader-Willi syndrome are rare and often involve translocations [see review, Butler and Thompson, 2000] with larger and/or smaller deletions than the typical deletion seen in 70% of PWS subjects. The causation of larger deletions which involve the more distal breakpoints, BP4, BP5 and the recently identified BP6, show low copy repeat (LCR) 15 duplicons [Pujana et al., 2002; Mignon-Ravix et al., 2007] which are known to facilitate recombination events in meiosis and promote rearrangements. Those subjects reported with a larger than expected typical 15q11-q13 deletion generally have unbalanced translocations involving other chromosomes and present with additional findings such as cardiac, renal and neurological abnormalities, palatal defects, speech disorders and ear tags. Pauli et al. in 1983 first described a boy with an expanded Prader-Willi syndrome phenotype due to an unbalanced translocation involving chromosomes 11 and 15 leading to a large 15q11-q15 deletion and a deletion of chromosome 11q25-qter. Hence, we present an infant female with several features not typically seen in PWS, but with a large rare de novo interstitial deletion from breakpoint BP1 and between reported breakpoints BP5 and BP6, approximately 12.3 Mb in size which is twice the size of the typical 15q11-q13 deletion seen in PWS.

Clinical Report

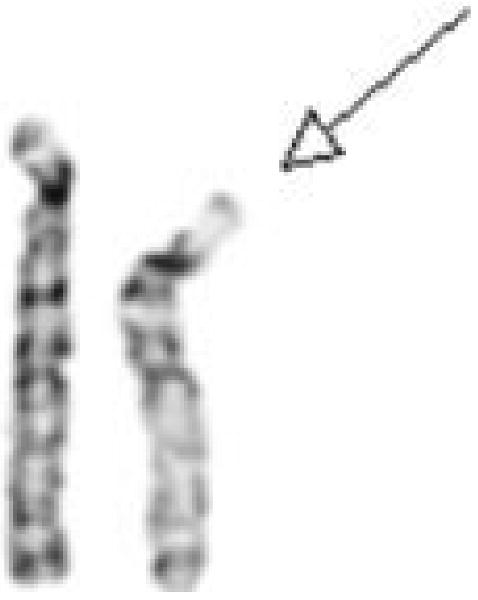

Our patient was born to a para 2, gravid 2, 24-year-old mother and a 30-year-old father. The mother had prenatal care and was on prenatal vitamins. The mother had hyperemesis causing her to lose at least 20 pounds at one point during the pregnancy. She denied alcohol use. The infant's estimated gestational age at birth was 37 weeks and was born by an induced vaginal delivery. Amniotic fluid was meconium stained. Apgar scores were 7, 8 and 8 at 1, 5, and 10 minutes, respectively. The infant required oral and gastric suctioning, oxygen and stimulation at delivery for cyanosis. The birthweight was 2.78 kg (10th centile), birth length was 50.5 cm (60th centile), and head circumference was 35 cm (50th centile). Along with hypotonia, a heart murmur was noted and no blood pressure readings could be obtained from the lower extremities. An echocardiogram demonstrated severe coarctation and a transverse arch with isthmal hypoplasia, bicuspid aortic valve, PDA with left-to-right shunt, PFO and a normal left ventricular outflow tract. She was noted to have right preauricular skin tags, a small involuting skin tag on her right cheek, a prominent nose with a depressed nasal bridge, high arched palate, mild micrognathia, long appearing hyperflexible fingers with convex nails, fifth finger clinodactyly, poorly-defined hand creases, dimples on elbows and hips indicating decreased fetal movement, decreased subcutaneous fat with generally loose skin except for the feet and toes which were edematous, generalized hypotonia and a poor suck. A three generation family history showed no history of birth defects, mental retardation or genetic diseases. Chromosome studies were obtained to rule out Turner syndrome; however, a de novo 15q11.2-q14 deletion was identified and confirmed using FISH probes (DI5S11 and GABRB3). The deletion was larger than the typical 15q11-q13 deletion seen in Prader-Willi or Angleman syndromes (see Fig 1). The two X chromosomes were normal.

Figure 1.

Partial G-banded karyotype showing the chromosome 15 pair (deleted chromosome 15 on the right).

At approximately three months of age, she was relatively healthy but primarily on NG feeds (80 ml formula every 4 hours). She had her coarctation repaired successfully during the first week of age. She turned her head side to side and attempted to roll over. Hearing evaluation was normal. She attempted a weak cry. No breathing difficulties or apnea were noted and no history of seizures. Upon examination she was a hypotonic infant lying on her back with arms at 90 degree angles to her side. Her weight was 4.5 kg (10th centile); height was 60 cm (75th centile); head circumference was 39.9 cm (60th centile); inner canthal distance was 2.4 cm (80th centile); outer canthal distance was 6.0 cm (20th centile); right ear length was 4.7 cm (97th centile); right hand length was 6.7 cm (15th centile); and right foot length was 8.5 cm (<3rd centile). Her waist circumference was 32 cm and hip circumference was 36 cm. She had no organomegaly with normal bowel patterns and urination. She had bitemporal narrowing with light blond hair, mild micrognathia, almond-shaped eyes and a thin upper lip with down-turned corners of the mouth. No cleft palate or teeth were noted but she had a high-arched palate and sticky saliva. A right pre-auricular tag was noted but without torticollis or thyroid enlargement. The labia minora was hypoplastic. She had a small sacral dimple but no hemi-hypertrophy or scoliosis. Her muscle mass and strength and deep tendon reflexes were decreased. No café-au-lait spots or striae were present. A head MRI was normal as were electrolytes and thyroid function tests.

At six and one-half months, she weighed 6.55 kg (10th centile), height of 66.8 cm (60th centile), and head circumference was 42.3 cm (50th centile). She showed generalized hypotonia with floppiness and limited head control. She turned her head from side to side, but had head lag. She rolled over, but could not sit up. She fatigued easily, but was not cyanotic. Most feedings were by G-tube which was placed at 4 months of age. She had right occipital flattening thought to be positional and mild strabismus. Growth hormone therapy began at 6 months of age.

At approximately 16 months of age her G-tube was removed and by two years of age, her weight, height and head circumference were within normal range. However, she did not walk but could sit alone and made attempts to stand at this time. She did not talk but had normal vision and hearing studies. No scoliosis was noted, but joint hyperextensibility was present. Foot and hand lengths were small (at 3rd centile). She had no other health problems at this time unrelated to PWS (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Frontal views taken at 8 months, 14 months and 21 months of age showing typical facial features of Prader-Willi syndrome.

Methods and Results

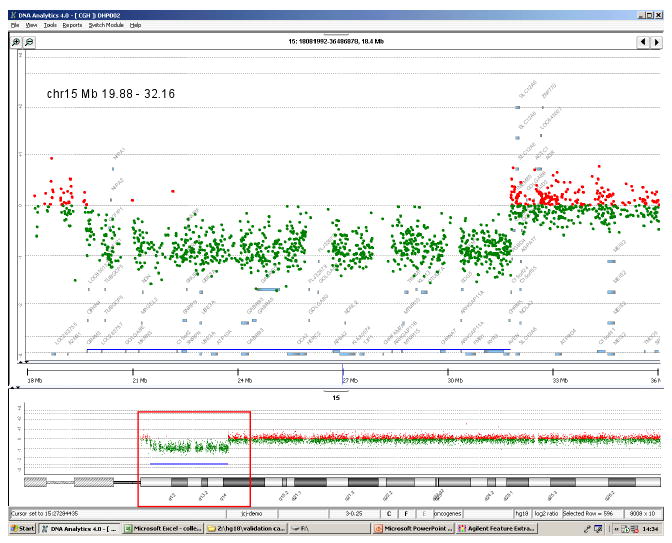

Because of the large appearing interstitial proximal 15q deletion observed in the G-banded karyotypes, an aCGH analysis was performed on genomic DNA extracted from peripheral blood and hybridized to the Agilent 244K whole genome microarrays with an average distance of 6.4 kb between probes (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA). Comparison genomic DNA was obtained commercially (Promega, Madison, WI) and matched for sex. The methods for genomic DNA preparation, labeling, hybridization and scanning can be found at http://www.home.agilent.com and as previously described [Butler et al., 2008]. The size of the deletion found was 12.3 Mb (19.88 to 32.16 Mb from the pterminus) and included approximately 60 protein coding genes and a cluster of snoRNAs genes from the 15q11.2-15q14 region (www.genome.ucsc.edu), nearly twice the size of the typical 15q11-q13 deletion seen in PWS (see Figure 3). The de novo deletion in our patient involved BP1 and the distal breakpoint was located in the 15q14 band between BP5 and BP6, two breakpoints predominantly involved in the development of pseudo-isodicentric (supernumerary) marker chromosome 15s and unbalanced translocations, respectively [Mignon-Ravix et al., 2007].

Figure 3.

Array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) comparing our subject with the 15q11-q14 deletion to chromosomally normal DNA. Upper panel shows an expansion of the deleted region with the location of the breakpoints and the genes within the region.

Several functional candidate genes were found in the deleted region in our patient including APBA2 with a possible role in synaptic vesicle docking/fusion; TRPM1 coding for a calcium channel; KLF13 coding for a zinc finger transcription factor; CHRNA7 coding for a nicotinic acetylcholine receptor which mediates neuronal signal transmission and implicated in schizophrenia and epilepsy; ARHGAP11A coding for a rho GTPase activating protein involved in cytoskeleton and growth of neuronal protrusions; GREM1 coding for an antagonist of BMP signaling; SCG5 which regulates neuroendocrine secretion; RYR3 coding for a ryanodine receptor involved in spatial learning and adaptation of acquired memory in response to external stimuli; AVEN coding for an apoptosis inhibitor and the CHRM5 gene, an acetylcholine receptor, muscarinic 5 located at 32.1 to 32.5 Mb. Our patient's deletion was similar, but larger than the patient reported by Calounova et al. [2008] with a 9.5 Mb deletion which started at 1.3 Mb distal to BP2 within the C15ORF2 gene and ended within the AVEN gene in the proximal 15q14 band. Our patient's deletion began at BP1 and extended slightly more distal to the AVEN gene including the neighboring CHRM5 gene (www.genome.ucsc.edu). Expressive and receptive language impairment with a reading disorder has also been linked to the 15q14 region [Stein et al., 2006]. There is no evidence that these genes are imprinted; therefore, their potential contribution in our patient's expanded PWS phenotype must be a consequence of dosage sensitivity of the genes or altered expression of neighboring intact genes due to a position effect.

Discussion

Recently, a 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome was reported by Sharp et al. [2008] and characterized by developmental delay with mild/moderate learning disability, seizures and subtle facial dysmorphism. These individuals can have minor hand anomalies such as short fourth metacarpal or fifth finger clinodactyly. However, 7 of 9 reported subjects had seizures or an abnormal EEG. These seizures varied from absence to generalized tonic-clonic and myoclonic epilepsy. The deletion encompasses the CHRNA7 gene implicated in epilepsy. Because there is no striking facial gestalt and given the lack of distinctive features, this syndrome is unlikely to become a disorder which is easily recognized clinically. The estimated population incidence is 1 in 40,000 [Sharp et al., 2008].

There is a shared 1.5 Mb region among segmental duplications located at BP4 and BP5 that contain six known genes. Although they occur more rarely, the 15q13.3 microdeletions are larger and occur between BP3 and BP5. Therefore, this region of chromosome 15q contains a complex set of segmental duplications, termed duplication blocks. Breakpoints BP4 and BP5 are in inverted orientation in a proportion of individuals in the general population facilitating non-homologous recombination at meiosis and disruption of genes in this region [Nicholls and Knepper, 2001]. Larger deletions of proximal 15q have been described, but most are associated with translocations involving other chromosomes and genes [see review, Butler and Thompson, 2000; Mignon-Ravix et al., 2007; Erdogan et al., 2007; Brunetti-Pierri et al., 2008]. The phenotype of cases due to unbalanced translocations could be influenced both by genes from the partner chromosome and by the size of the missing proximal long arm of chromosome 15.

De novo interstitial deletions are very rare that involve the Prader-Willi syndrome chromosome region and extend distally to include the 15q14 band [Galan et al., 1991; Autio et al., 1998; Calounova et al., 2008]. However, the phenotype of patients with the PWS deletion extending to the 15q14 or q15 involving unbalanced translocations [Pauli et al., 1983; Schwartz et al., 1985; Smith et al., 2000; Matsumura et al., 2003; Windpassinger et al., 2003; Varela et al., 2004; Schule et al., 2005; Mignon-Ravix et al, 2007] or those with the deletion distal to the PWS chromosome region which is intact [Herva and Vuorinen, 1980; Tonk et al., 1995; Erdogan et al., 2007; Brunetti-Pierri et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2008] have in common facial dysmorphism, cleft palate, heart, renal and pulmonary defects, edema, hypertonia, stiff joints, undescended testes, mental and motor retardation, speech disorder, deafness and/or ear tags. Comparing the phenotype of those individuals with the large 15q11-q14 interstitial deletion with those having the interstitial deletion located more distally and not involving the PWS region will be essential for genotype-phenotype studies. Therefore, our subject represents one of a very rare subset of patients showing the expanded PWS phenotype due to a large de novo interstitial deletion of the 15q11-q14 region including the Prader-Willi chromosome region and not having a chromosome 15 translocation. Our patient had the typical PWS findings (infantile hypotonia, a weak cry, narrow bifrontal diameter, mild micrognathia, thin upper lip, strabismus, blond hair, small hands and feet with long-appearing hyperflexible fingers and poorly defined hand creases, fifth finger clinodactyly, small labia minora, dimples on elbows and hips, and decreased subcutaneous fat), but in addition, had congenital heart disease, right preauricular skin tags, delayed speech with normal hearing, a small involuting skin tag on the right cheek, a high-arched palate and edematous feet. Our subject has the expanded PWS phenotype and non-typical PWS features that overlap with findings seen in individuals reported with the more distal 15q14 deletion. The authors encourage the reporting of additional subjects with the same or similar chromosome abnormality using aCGH testing to further establish and clarify this rare cytogenetic condition useful for genotype-phenotype correlations.

Acknowledgments

I thank Carla Meister for expert preparation of the manuscript. Partial funding support was provided from the NIH rare disease grant (1U54RR019478) and a grant from PWSA (USA).

References

- Autio SH, Pihko H, Tengstrom C. Clinical features in a de novo interstitial deletion 15q13 to q15. Clin Genet. 1988;34:293–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1988.tb02881.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bittel DC, Butler MG. Prader-Willi syndrome: clinical genetics, cytogenetics and molecular biology. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2005;7:1–20. doi: 10.1017/S1462399405009531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunetti-Pierri N, Sahoo T, Frioux S, Chinault C, Zascavage R, Cheung SW, Peters S, Shinawi M. 15q13q14 deletions: phenotypic characterization and molecular delineation by comparative genomic hybridization. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:1933–1941. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MG, Fischer W, Kibiryeva N, Bittel DC. Array comparative genomic hybridization (aCGH) analysis in Prader-Willi syndrome. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146:854–860. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler MG, Lee PKD, Whitman BY. Management of Prader-Willi Syndrome. 3rd. New York, NY: Springer; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Butler MG, Thompson T. Prader-Willi syndrome: Clinical and genetic findings. Endocrinology. 2000;10:35–65. doi: 10.1097/00019616-200010041-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calounova G, Hedvicakova P, Silhanova E, Kreckova G, Sediacek Z. Molecular and clinical characterization of two patients with Prader-Willi syndrome and atypical deletions of proximal chromosome 15q. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A:1955–1962. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassidy SB, Driscoll DJ. Prader-Willi syndrome. Eur J Hum Genet. 2009;17:3–13. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2008.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CP, Lin SP, Tsai FJ, Chern SR, Lee CC, Wang W. A 5.6-Mb deletion in 15q14 in a boy with speech and language disorder, cleft palate, epilepsy, a ventricular septal defect, mental retardation and developmental delay. Eur J Med Genet. 2008;51:368–372. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erdogan F, Ullmann R, Chen W, Schubert M, Adolph S, Hultschig C, Kalscheuer V, Ropers HH, Spaich C, Tzschach A. Characterization of a 5.3 Mb deletion in 15q14 by comparative genomic hybridization using a whole genome tiling path BAC array in a girl with heart defect, cleft palate, and developmental delay. Am J Med Genet A. 2007;143:172–178. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galan F, Aguilar MS, Gonzalez J, Clement F, Sanchez R, Tapia M, Moya M. Interstitial 15q deletion without a classic Prader-Willi phenotype. Am J Med Genet. 1991;38:532–534. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320380406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herva R, Vuorinen O. Congenital heart disease with del(15q) mosaicism. Clin Genet. 1980;17:26–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1980.tb00108.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mignon-Ravix C, Depetris D, Luciani JJ, Cuoco C, Krajewska-Walasek M, Missirian C, Collignon P, Delobel B, Croquette MF, Moncla A, Kroisel PM, Mattei MG. Recurrent rearrangements in the proximal 15q11-q14 region: a new breakpoint cluster specific to unbalanced translocations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2007;15:432–440. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5201775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumura M, Kubota T, Hidaka E, Wakui K, Kadowaki S, Ueta I, Shimizu T, Ueno I, Yamauchi K, Herzing LB, Nurmi EL, Sutcliffe JS, Fukushima Y, Katsuyama T. ‘Severe’ Prader-Willi syndrome with a large deletion of chromosome 15 due to an unbalanced t (15,22)(q14;q11.2) translocation. Clin Genet. 2003;63:79–81. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2003.630114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholls RD, Knepper JL. Genome organization, function, and imprinting in Prader-Willi and Angelman syndromes. Annu Rev Genomics Hum Genet. 2001;2:153–175. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.2.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pauli RM, Meisner LF, Szmanda RJ. Expanded Prader-Willi syndrome in a boy with an unusual 15q chromosome deletion. Am J Dis Child. 1983;137:1087–1089. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1983.02140370047015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujana MA, Nadal M, Guitart M, Armengol L, Gratacos M, Estivill X. Human chromosome 15q11-q14 regions of rearrangements contain clusters of LCR15 duplicons. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10:26–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz S, Max SR, Panny SR, Cohen MM. Deletions of proximal 15q and non-classical Prader-Willi syndrome phenotypes. Am J Med genet. 1985;20:255–263. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320200208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp AJ, Mefford HC, Li K, Baker C, Skinner C, Stevenson RE, Schroer RJ, Novara F, De Gregori M, Ciccone R, Broomer A, Casuga I, Wang Y, Xiao C, Barbacioru C, Gimelli G, Bernardina BD, Torniero C, Giorda R, Regan R, Murday V, Mansour S, Fichera M, Castiglia L, Failla P, Ventura M, Jiang Z, Cooper GM, Knight SJ, Romano C, Zuffardi O, Chen C, Schwartz CE, Eichler EE. A recurrent 15q13.3 microdeletion syndrome associated with mental retardation and seizures. Nat Genet. 2008;40:322–328. doi: 10.1038/ng.93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schule B, Oviedo A, Johnston K, Pai S, Francke U. Inactivating mutations in ESCO2 cause SC phocomelia and Roberts syndrome: no phenotype-genotype correlation. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:1117–1128. doi: 10.1086/498695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Jauch A, St Heaps L, Robson L, Kearney B. Unbalanced translocation t(15;22) in “severe” Prader-Willi syndrome. Ann Genet. 2000;43:125–130. doi: 10.1016/s0003-3995(00)01017-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein CM, Millard C, Kluge A, Miscimarra LE, Cartier KC, Freebairn LA, Hansen AJ, Shriberg LD, Taylor HG, Lewis BA, Iyengear SK. Speech sound disorder influenced by a locus in 15q14 region. Behav Genet. 2006;36:858–868. doi: 10.1007/s10519-006-9090-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonk V, Wyandt HE, Osella P, Skare J, Wu BL, Haddad B, Milunsky A. Cytogenetic and molecular cytogenetic studies of a case of interstitial deletion of proximal 15q. Clin Genet. 1995;48:151–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.1995.tb04076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varela MC, Lopes GM, Koiffmann CP. Prader-Willi syndrome with an unusually large 15q deletion due to an unbalanced translocation t(4;15) Ann Genet. 2004;47:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.anngen.2004.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang NJ, Liu D, Parokonny AS, Schanen NC. High-resolution molecular characterization of 15q11-q13 rearrangements by array comparative genomic hybridization (array CGH) with detection of gene dosage. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;75:267–281. doi: 10.1086/422854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Windpassinger C, Petek E, Waganer K, Langmann A, Buiting K, Kroisel PM. Molecular characterization of a unique de novo 15q deletion associated with Prader-Willi syndrome and central visual impairment. Clin Genet. 2003;63:297–302. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-0004.2003.00059.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]