Abstract

Background

Adenoidectomy, surgical removal of the adenoids, is a common ENT operation worldwide in children with recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms. A systematic review on the effectiveness of adenoidectomy in this specific group has not previously been performed.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of adenoidectomy versus non‐surgical management in children with recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms.

Search methods

We searched the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group Trials Register; the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL); PubMed; EMBASE; CINAHL; Web of Science; BIOSIS Previews; Cambridge Scientific Abstracts; mRCT and additional sources for published and unpublished trials. The date of the most recent search was 30 March 2009.

Selection criteria

Randomised controlled trials comparing adenoidectomy, with or without tympanostomy tubes, versus non‐surgical management or tympanostomy tubes alone in children with recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms. The primary outcome studied was the number of episodes, days per episode and per year with nasal symptoms and the proportion of children with recurrent episodes of nasal symptoms. Secondary outcomes were mean number of episodes, mean number of days per episode and per year, and proportion of children with nasal obstruction alone.

Data collection and analysis

Two authors assessed trial quality and extracted data independently.

Main results

Only one study included children scheduled for adenoidectomy because of recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms or middle ear disease. In this study no beneficial effect of adenoidectomy was found. The numbers in this study were, however, small (n = 76) and the quality of the study was moderate. The outcome was improvement in episodes of common colds. The risk differences were non‐significant, being 2% (95% CI ‐18% to 22%) and ‐11% (95% CI ‐28% to 7%) after 12 and 24 months, respectively.

A second study included children with recurrent acute otitis media (n = 180). As otitis media is known to be associated with nasal symptoms, the number of days with rhinitis was studied as a secondary outcome measure. The risk difference was non‐significant, being ‐4 days (95% CI ‐13 to 7 days).

Authors' conclusions

Current evidence regarding the effect of adenoidectomy on recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms or nasal obstruction alone is sparse, inconclusive and has a significant risk of bias.

High quality trials assessing the effectiveness of adenoidectomy in children with recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms should be initiated.

Keywords: Adolescent; Child; Humans; Adenoidectomy; Chronic Disease; Nasal Obstruction; Nasal Obstruction/surgery; Otitis Media with Effusion; Otitis Media with Effusion/surgery; Otitis Media, Suppurative; Otitis Media, Suppurative/surgery; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic; Recurrence; Tympanic Membrane; Tympanic Membrane/surgery

Plain language summary

Adenoidectomy for recurrent of chronic nasal symptoms in children

Infections of the upper respiratory tract, presenting as recurrent nasal symptoms (nasal discharge with or without nasal obstruction) are very common in children. Removal of the adenoids (adenoidectomy) is a surgical procedure that is frequently performed in these children. It is thought that adenoidectomy prevents recurrence of nasal symptoms.

Our review, which includes two studies (256 children), shows that it is uncertain whether adenoidectomy is effective in children with recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms. Further high quality trials are needed.

Background

Incidence

Adenoidectomy is one of the most frequently performed surgical procedures in children in Western countries. Annual adenoidectomy rates, however, differ between countries, from 127/10,000 children per year in Belgium, 101/10,000 children per year in the Netherlands and 39/10,000 children per year in England to 24/10,000 and 17/10,000 children per year in the United States and Canada, respectively (Schilder 2004).

Adenoidectomy

Indications for adenoidectomy include recurrent or chronic nasal discharge, recurrent episodes of acute otitis media (AOM), persistent otitis media with effusion (OME) and symptoms of upper airway obstruction. In most cases children are operated on for a combination of nasal and middle ear symptoms. The operation involves removing the adenoids ‐ a nasopharyngeal reservoir of potential respiratory pathogens and a potential cause of obstruction of the nasal airway. As such, nasal breathing is thought to improve and recurrence of nasal discharge is thought to decrease.

Evidence for adenoidectomy

At present the effectiveness of adenoidectomy in children with recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms remains uncertain and practice is experience‐based rather than evidence‐based. Some surgeons prefer to perform adenoidectomy in these children, whereas others do not. In previous systematic reviews for The Cochrane Library the effectiveness of 1) grommets (ventilation tubes) for recurrent acute otitis media in children (McDonald 2008), 2) grommets (ventilation tubes) for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children (Lous 2005) and 3) tonsillectomy or adeno‐tonsillectomy versus non‐surgical treatment for chronic/recurrent acute tonsillitis (Burton 2009) have all been assessed. For adenoidectomy in children with nasal symptoms no such review is available. This study therefore provides a comprehensive systematic review and meta‐analysis of randomised controlled trials evaluating the effectiveness of adenoidectomy in children with recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms.

Objectives

To assess the effectiveness of adenoidectomy with or without tympanostomy tubes compared with non‐surgical management or tympanostomy tubes alone in children up to 18 years of age with recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

We considered all identified randomised controlled trials of adenoidectomy for recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms compared with non‐surgical treatment or tympanostomy tubes alone for inclusion in this review. We included trials in which the method of randomisation was not specified in detail, but we excluded quasi‐randomised trials (e.g. allocation by date of birth or record number).

Studies had to have a follow up of at least six months. Studies with a follow up of six to 12 months were reported separately from those with a follow up of 12 months or more.

Desirable time points of outcome assessment were six months, 12 months, 24 months and 36 months.

Types of participants

Children up to 18 years of age diagnosed with recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms.

Types of interventions

To evaluate the effects of adenoidectomy we compared the following interventions:

adenoidectomy (with or without myringotomy) versus non‐surgical treatment or myringotomy only;

adenoidectomy with unilateral tympanostomy tube versus unilateral tympanostomy tube only (in studies of this type the ear without the tympanostomy tube is evaluated to study the effect of adenoidectomy);

adenoidectomy with bilateral tympanostomy tubes versus bilateral tympanostomy tubes only.

Non‐surgical management included watchful waiting and medical treatment including antibiotics (intermittent and long‐term), steroids, antihistamines and analgesics.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcome measure was the number of episodes, days per episode and per year with nasal symptoms, and the proportion of children with recurrent episodes of nasal symptoms. Nasal symptoms are defined as nasal discharge with or without obstruction as observed by the parents or physician.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes are as follows.

-

Nasal obstruction alone.

Number of episodes per year.

Number of days with symptoms per episode and per year.

Proportion of children with recurrent episodes.

'Recurrent' was defined as the patient having three or more episodes of nasal symptoms in a period of six months, or four or more episodes in a period of 12 months (Rosenfeld 2000).

Search methods for identification of studies

We conducted systematic searches for randomised controlled trials on the effectiveness of adenoidectomy in children up to 18 years of age with recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms and middle ear disease. After finalising the first draft of the review in which we combined recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms and middle ear disease, there was a general consensus that the review would benefit from being split into two separate reviews; one looking at the effects of adenoidectomy on nasal symptoms (this review) and the other at the effect of otitis media (van den Aardweg 2010). There were no language, publication year or publication status restrictions. We contacted original authors for clarification and further data if trial reports were unclear and arranged translations of papers where necessary. The date of the last search was 30 March 2009.

Electronic searches

We searched the following databases from their inception: the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group Trials Register; the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL, The Cochrane Library Issue 1, 2009); PubMed; EMBASE; CINAHL; LILACS; KoreaMed; IndMed; PakMediNet; CAB Abstracts; Web of Science; BIOSIS Previews; CNKI; mRCT (Current Controlled Trials); ClinicalTrials.gov; ICTRP (International Clinical Trials Registry Platform); ClinicalStudyResults.org and Google.

All other search strategies were modelled on the search strategy designed for CENTRAL. Where appropriate, we combined subject strategies with adaptations of the highly sensitive search strategy designed by The Cochrane Collaboration for identifying randomised controlled trials and controlled clinical trials (as described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.0.1, Box 6.4.b. (Handbook 2008)). Search strategies for major databases including CENTRAL are provided in Appendix 1.

Searching other resources

We checked the reference lists of identified publications for additional trials. We searched PubMed; TRIPdatabase; NHS Evidence ‐ ENT and Audiology; and Google to retrieve existing systematic reviews possibly relevant to this systematic review, in order to search their reference lists for additional trials. We scanned abstracts of conference proceedings via the Cochrane Ear, Nose and Throat Disorders Group Trials Register and CENTRAL.

Data collection and analysis

We conducted the review according to the recommendations of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.0.1 (Handbook 2008).

Selection of studies

Two review authors (MvdA, EH) scanned the abstracts to identify relevant randomised controlled trials. The same two authors obtained and reviewed the full texts of these articles. We assessed eligibility of the trials independently and resolved any differences in opinion by discussion between the two authors. Reasons for exclusion of potentially relevant studies are given in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors (MvdA, EH) also performed data extraction independently, followed by a consensus conference to resolve differences. We extracted the following data from each study: total number of children in each trial, description of participants (mean age, country of origin, inclusion and exclusion criteria, allergy status, adenoid size), follow‐up time in months, description of intervention and control therapy, number of patients per intervention group, primary and secondary outcomes, and the author’s conclusion.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two authors (MvdA, CB) assessed the quality of all included trials independently using the Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias ('Risk of bias' table, Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions, chapter 5 (Handbook 2008)). Six specific domains were addressed, i.e. sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding, incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting and ‘other biases’. By answering pre‐specified questions we reported the execution of the study and judged the risk of bias for each domain. The outcome for each domain was either 1) yes, a high risk, 2) no, a low risk or 3) an unknown or unclear risk of bias. We resolved disagreement by discussion (MvdA, CB, MR).

We planned to assess publication bias with a scatter plot (funnel plot) of the log rate ratios (x‐axis) versus precision defined as 1/standard error (y‐axis) (Handbook 2008).

Data synthesis

We planned to use RevMan version 5.0 (RevMan 2008) to carry out the meta‐analyses for comparable trials and outcomes.

For continuous outcomes (i.e. number of episodes, number of days per episode and number of days per year) we calculated standard mean differences (SMD) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI).

For dichotomous outcomes, we measured the estimates of effect as risk differences (RD) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals. Risk differences were calculated using: (proportion of children with outcome present in adenoidectomy group) ‐ (proportion of children with outcome present in control group).

If heterogeneity was low (I2 < 25%) we planned to calculate the summary weighted risk differences and 95% confidence intervals (random‐effects model) by the Mantel‐Haenszel method, which weighs studies by the number of events in the control group, using the Cochrane statistical package in RevMan (version 5.0).

Furthermore, we also planned to perform sensitivity analyses excluding the studies with the lowest methodological quality, according to the Cochrane Collaboration's risk of bias assessment, to establish whether this factor influences the final outcome. We also intended to perform subgroup analyses for age groups and adenoid size.

Ultimately it was not possible to either pool the data in a meta‐analysis nor to perform sensitivity and subgroup analysis. Data allowing, we hope to pool the data in a meta‐analysis and include sensitivity and subgroup analyses in future updates of this review.

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

Our search of CENTRAL, PubMed, EMBASE and other databases retrieved a total of 204 articles. We first sifted the articles by title/abstract and this left us 31 articles to read in full text. We excluded 28 publications from the review: 12 did not specifically include nasal symptoms as an outcome measure. A further 11 were duplicate or follow‐up reports of studies already excluded. One study by Sagnelli et al (Sagnelli 1990) could not be retrieved. Full details of the reasons for excluding studies can be found in the 'Characteristics of excluded studies' table.

No additional trials were identified by checking the bibliographies of the selected trials and reviews, nor by contacting the first or corresponding author of the eligible trials.

Two studies (n = 256 children) that looked at the effect of adenoidectomy on nasal symptoms were included in this review (Rynnel‐Dagöo 1978; Koivunen 2004).

Included studies

1) Adenoidectomy (with or without myringotomy) versus non‐surgical treatment or myringotomy only.

2) Adenoidectomy with unilateral tympanostomy tube versus unilateral tympanostomy tube only; non‐operated ear examined for comparison.

No studies found.

3) Adenoidectomy with bilateral tympanostomy tubes versus bilateral tympanostomy tubes only.

No studies found.

Adenoidectomy (with or without myringotomy) versus non‐surgical treatment or myringotomy only

Rynnel‐Dagöo 1978 reported on 105 children aged less than 12 years with recurrent serous and purulent otitis media, frequent upper airway infections and nasal obstruction. After randomisation 29 children were excluded for various reasons, i.e. 76 children remained for analysis; 37 in the adenoidectomy group and 39 in the control group. Outcomes were change (better, deteriorated or unchanged) in frequency of common colds, purulent or serous otitis media and nasal obstruction. The follow up was two years.

Koivunen 2004 reported on 180 children aged 10 months to two years with at least three episodes of acute otitis media during the previous six months, which is known to be associated with nasal symptoms. They were randomly allocated to 1) adenoidectomy (n = 60), 2) chemoprophylaxis (n = 60) or 3) placebo (n = 60). One of the secondary outcomes was days with rhinitis. The primary outcome was intervention failure in the first six months, which was defined as two or more episodes of acute otitis media in two months or at least three in six months, or middle ear effusion for at least two months. Other secondary outcomes were mean number of 1) episodes of acute otitis media, 2) visits to a doctor, 3) antibiotic prescriptions and 4) days with earache or fever. Follow up was two years.

In summary, both studies differed regarding inclusion criteria and the outcomes measured. Only one study (Rynnel‐Dagöo 1978) included children for whom the primary indication for adenoidectomy was nasal symptoms.

Risk of bias in included studies

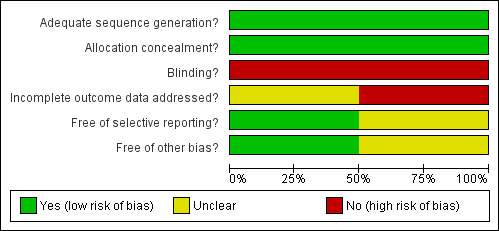

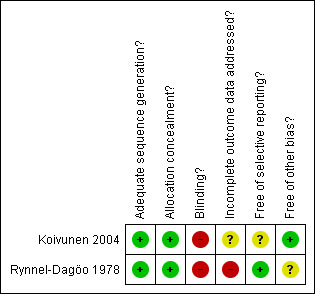

Figure 1 and Figure 2 show the results of the quality assessment according to the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias. Figure 1 shows the judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across included studies, whereas Figure 2 shows the judgements of both included studies separately.

1.

Methodological quality graph: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Methodological quality summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

Sequence generation and allocation concealment

Both studies had a low risk of bias for sequence generation and allocation concealment.

Blinding

Both studies had a high risk of bias for blinding.

Incomplete outcome data

One study had a high risk of bias for incomplete outcome data (Rynnel‐Dagöo 1978) and in the other study the risk of bias for this reason was unclear (Koivunen 2004).

Selective outcome reporting

The risk of selective outcome reporting was unclear in one study (Koivunen 2004) and low in the other study (Rynnel‐Dagöo 1978).

Other sources of bias

The risk of other sources of bias was unclear in one study (Rynnel‐Dagöo 1978) and low in the other study (Koivunen 2004).

Effects of interventions

Adenoidectomy (with or without myringotomy) versus non‐surgical treatment

Rynnel‐Dagöo 1978 found an overall improvement in the frequency of common colds and otitis media in both the adenoidectomy and control group, but no difference was found between intervention groups.

Improvement in episodes of common colds, defined as a reduction in number of more than two periods of snottiness, were found in 75% versus 73% after 12 months, and in 77% versus 88% after 24 months in the adenoidectomy and control group, respectively. The risk differences were non‐significant, being 2% (95% CI ‐18% to 22%) and ‐11% (95% CI ‐28% to 7%).

Improvement in frequency of nasal obstruction, meaning a change from frequent to infrequent (not quantified in absolute numbers), was found in 61% versus 41% after 12 months, and in 63% versus 55% after 24 months in the adenoidectomy and control group, respectively. The risk differences were non‐significant, being 20% (95% CI ‐2% to 43%) and 8% (95% CI ‐15% to 32%).

Koivunen 2004 showed that at six months the mean number of days with rhinitis in children who underwent adenoidectomy was 26 (SD 23) as compared to 23 (25) days in the control group. The difference was non‐significant, being ‐4 days (95% CI ‐13 to 7 days).

The trials were too heterogeneous to pool in a meta‐analysis.

Discussion

Summary of main results

Current evidence regarding the effect of adenoidectomy on recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms and nasal obstruction alone is sparse, inconclusive and has a significant risk of bias.

Potential biases in the review process

During the review process potential biases were identified both in the individual trials and in the review process itself.

Only Koivunen 2004 provided a power analysis and included adequate numbers. Rynnel‐Dagöo 1978 included relatively few patients, therefore the power of the study may have been too low, leading to either a type I or type II error.

Loss to follow up was significant in both studies (up to 28%). This can be associated with either good or poor outcome. In one trial children were excluded after randomisation, which may have led to residual confounding (Rynnel‐Dagöo 1978).

One study was analysed per protocol and no data were available to perform intention‐to‐treat analyses (Rynnel‐Dagöo 1978). Per protocol analyses in which children who change groups are excluded may underestimate the treatment effect. In surgical trials only children in the watchful waiting group with severe complaints can change treatment group, whereas children in the surgical group who may experience similarly severe complaints cannot change treatment group. Analysing children on the basis of time spent in a treatment arm may over or underestimate the treatment effect.

Information bias may be considerable since trials on adenoidectomy, like most surgical trials, cannot be performed in a true double‐blind fashion. Such bias will overestimate the effect of the intervention.

Generalisability of the trials can be questioned since only a very small proportion of children undergoing adenoidectomy were included in the trials.

Due to the lack of data on factors that may modify the effect of adenoidectomy, such as age, adenoid size or allergic rhinitis, it was not possible to perform subgroup analyses and identify children that may benefit more or less from the operation.

The authors of this review were not blinded to authorship and origin of the included studies, since they knew most of the literature before embarking on this review.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

Current evidence regarding the effectiveness of adenoidectomy for nasal symptoms is sparse, inconclusive and has a significant risk of bias. It therefore remains uncertain whether adenoidectomy has an effect on recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms and nasal obstruction alone.

Implications for research.

High quality trials assessing the effectiveness of adenoidectomy on recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms or nasal obstruction alone should be initiated. These trials should be sufficiently powered for analysis of potential effect modifiers, so that subgroups benefiting most from adenoidectomy can be identified. Further, a broader spectrum of outcomes should be included, such as quality of life and cost‐effectiveness.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 16 February 2010 | Amended | Declarations of interest updated. |

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the work of Mohammed Attrach in the early stages of the protocol.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategies for electronic databases

| CENTRAL | PubMed | EMBASE (Ovid) |

| #1 MeSH descriptor Adenoidectomy explode all trees #2 MeSH descriptor Adenoids explode all trees with qualifier: SU #3 adenoidectom* or adenotonsillectom* or adenotonsilectom* or adeno NEXT tonsillectomy* or adeno NEXT tonsilectom* #4 (#1 OR #2 OR #3) #5 MeSH descriptor Adenoids explode all trees #6 adenoid* or adenotonsil* #7 (#5 OR #6) #8 MeSH descriptor Surgical Procedures, Operative explode all trees #9 (surg*:ti or operat*:ti or excis*:ti or extract*:ti or remov*:ti or dissect*:ti or ablat*:ti or coblat*:ti or laser*:ti) #10 (#8 OR #9) #11 (#7 AND #10) #12 (#4 OR #11) #13 (nose OR nasal) NEAR (symptom* OR discharg* OR secret* OR obstruct*) #14 rhinorrhea OR rhinorrhoea #15 MeSH descriptor Nasal Obstruction explode all trees #16 airway* AND obstruct* #17 breath* AND impair* #18 MeSH descriptor Otitis Media explode all trees #19 middle NEXT ear NEXT (infect* OR inflam* OR disease*) #20 otitis OR aom OR ome #21 glue AND ear #22 (#13 OR #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21) #23 (#12 AND #22) | #1 "Adenoidectomy"[Mesh] #2 "Adenoids/surgery"[Mesh] #3 adenoidectom* [tiab] OR adenotonsillectom* [tiab] OR adenotonsilectom* [tiab] OR "adeno tonsillectomy" [tiab] OR "adeno tonsilectom" [tiab] #4 #1 OR #2 OR #3 #5 "Adenoids"/ [Mesh] #6 adenoid* [tiab] OR adenotonsil* [tiab] #7 #5 OR #6 #8 "Surgical Procedures, Operative"[Mesh] #9 "surgery"[Subheading] #10 surg* [tiab] OR operat* [tiab] OR excis* [tiab] OR extract* [tiab] OR remov* [tiab] OR dissect* [tiab] OR ablat* [tiab] OR coblat* [tiab] OR laser* [tiab] #11 #8 OR #9 OR #10 #12 #7 AND #11 #13 #4 OR #12 #14 (nose [tiab] OR nasal [tiab]) AND (symptom* [tiab] OR discharg* [tiab] OR secret* [tiab] OR obstruct* [tiab]) #15 rhinorrhea [tiab] OR rhinorrhoea [tiab] #16 "Nasal Obstruction"[Mesh] #17 airway* [tiab] AND obstruct* [tiab] #18 breath* [tiab] AND impair* [tiab] #19 "Otitis Media"[Mesh] #20 middle [tiab] AND ear [tiab] AND (infect* [tiab] OR inflam* [tiab] OR disease* [tiab]) #21 otitis [tiab] OR aom [tiab] OR ome [tiab] #22 glue [tiab] AND ear [tiab] #23 #14 OR #15 OR #16 OR #17 OR #18 OR #19 OR #20 OR #21 OR #22 #24 #13 AND #23 | 1 adenoidectomy/ 2 (adenoidectom* or adenotonsillectom* or adenotonsilectom* or "adeno tonsillectomy*" or "adeno tonsilectom*").tw. 3 1 or 2 4 *Adenoid/ 5 (adenoid* or adenotonsil*).ti. 6 4 or 5 7 (surg* or operat* or excis* or extract* or remov* or dissect* or ablat* or coblat* or laser*).ti. 8 exp *Surgery/ 9 8 or 7 10 6 and 9 11 3 or 10 12 nose obstruction/ or rhinorrhea/ 13 *airway obstruction/ or *upper respiratory tract obstruction/ 14 ((nose or nasal) and (symptom* or discharg* or obstruct* or secret*)).tw. 15 (rhinorrhea or rhinorrhoea).tw. 16 (airway* and obstruct*).tw. 17 (breath* and impair*).tw. 18 exp Middle Ear Disease/ 19 (middle and ear and (infect* or inflamm* or disease*)).tw. 20 (otitis or aom or raom or ome).tw. 21 (glue and ear).tw. 22 21 or 17 or 12 or 20 or 15 or 14 or 18 or 13 or 16 or 19 23 22 and 11 |

| CINAHL (EBSCO) | Web of Science | BIOSIS Previews/CAB Abstracts (Ovid) |

| S1 (MH "Adenoidectomy") S2 (MH "Adenoids/SU") S3 adenoidectom* or adenotonsillectom* or adenotonsilectom* or "adeno tonsillectomy*" or "adeno tonsilectom*" S4 (MM "Adenoids") S5 TI adenoid* or adenotonsil* S6 TI surg* or operat* or excis* or extract* or remov* or dissect* or ablat* or coblat* or laser* S7 (MH "Surgery, Operative") S8 S6 or S7 S9 S4 or S5 S10 S8 and S9 S11 S1 or S2 or S3 or S10 | #1 TS=(adenoidectom* or adenotonsillectom* or adenotonsilectom* or "adeno tonsillectomy*" or "adeno tonsilectom*") #2 TI=(adenoid* or adenotonsil*) #3 TI=(surg* or operat* or excis* or extract* or remov* or dissect* or ablat* or coblat* or laser*) #4 #2 AND #3 #5 #1 OR #4 #6 TS=((nose or nasal) and (symptom* or discharg* or obstruct* or secret*)) #7 TS=(rhinorrhea or rhinorrhoea) #8 TS=(airway* and obstruct*) #9 TS=(breath* and impair*) #10 TS=(middle and ear and (infect* or inflamm* or disease*)) #11 TS=(otitis or aom or raom or ome) #12 TS=(glue and ear) #13 #6 OR #7 OR #8 OR #9 OR #10 OR #11 OR #12 #14 #5 AND #13 | 1 (adenoidectom* or adenotonsillectom* or adenotonsilectom* or "adeno tonsillectomy*" or "adeno tonsilectom*").tw. 2 (adenoid* or adenotonsil*).ti. 3 (surg* or operat* or excis* or extract* or remov* or dissect* or ablat* or coblat* or laser*).ti. 4 ((nose or nasal) and (symptom* or discharg* or obstruct* or secret*)).tw. 5 (rhinorrhea or rhinorrhoea).tw. 6 (airway* and obstruct*).tw. 7 (breath* and impair*).tw. 8 (middle and ear and (infect* or inflamm* or disease*)).tw. 9 (otitis or aom or raom or ome).tw. 10 (glue and ear).tw. 11 3 and 2 12 11 or 1 13 8 or 6 or 4 or 7 or 10 or 9 or 5 14 13 and 12 |

Appendix 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria of studies included in this review

| Author | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Koivunen 2004 | Three or more episodes of acute otitis media in the last 6 months | Previously performed adenoidectomy or tympanostomy tubes, cranial anomalies, documented immunological disorders and ongoing antimicrobial chemoprophylaxis |

| Rynnel‐Dagöo 1978 | Recurrent serous/purulent otitis media, frequent upper airway infections and nasal obstruction | Cases of severe nasal obstruction, previous operation performed, refused operation by parents, cases of recurring adenoids, diabetes or administrative mishaps |

Characteristics of studies

Characteristics of included studies [ordered by study ID]

Koivunen 2004.

| Methods | RCT | |

| Participants | 180 children aged 10 months to 2 years with recurrent acute otitis media | |

| Interventions | Adenoidectomy (n = 60), chemoprophylaxis (n = 60), placebo (n = 60) | |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome measured at 12 and 24 months:

Secondary outcomes measured until intervention failure, drop‐out, or 6 months of follow up, whichever came first:

|

|

| Notes | Duration of an episode is not described Follow up 24 months; 34 children (28%) were lost to follow up in the non‐adenoidectomy groups and 2 children (3%) were lost to follow up in the adenoidectomy group after 24 months follow up At the beginning of the study 12 children in the adenoidectomy group concurrently received tympanostomy tubes. During follow up 23 children (13%) (6 adenoidectomy, 6 chemoprophylaxis, 11 placebo) received tympanostomy tubes because of persistent middle ear fluid. Intention‐to‐treat method was used for analysis No complications in the adenoidectomy procedures were reported by the surgeons |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Quote: “We randomly assigned children to receive..(...) We performed block randomisation with a block size of six using numbered containers so that allocation was concealed from the investigator.” |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Quote: “We performed block randomisation with a block size of six using numbered containers so that allocation was concealed from the investigator.” |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Quote: "The sulfafurazole and placebo suspensions were given in a double blind fashion.” Comment: blinding for adenoidectomy versus placebo was not possible. Outcome measures are subjective. |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | Unclear risk | Quote: “Children in the sulfafurazole and placebo groups discontinued intervention and received anther prophylaxis more often than children in the adenoidectomy group (fig.1).” Comment: 1 child was lost to follow up in the adenoidectomy group, whereas 15 and 14 children were lost to follow up in the sulfafurazole and placebo group respectively. However, intention‐to‐treat analysis with all 180 randomised children was performed. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Unclear risk | Comment: all outcome measures are presented. The primary outcome in Table 2 and the secondary outcome measures in Table 3. |

| Free of other bias? | Low risk | Quote 1: “However, as the children in the placebo group and sulfafurazole groups discontinued the allocated intervention more often than the children in the adenoidectomy group (...), and as these children may have had more severe otitis media, this could have caused some bias by weakening the true effect of adenoidectomy.” Quote 2: “There are two other important sources of bias that may have diminished the true effect of the treatments: firstly, the use of symptom diaries to collect the outcome, and, secondly, the possibility of misdiagnoses". Comment: 12 children in the adenoidectomy group also received tympanostomy tubes |

Rynnel‐Dagöo 1978.

| Methods | Prospective controlled study | |

| Participants | 105 children aged less than 12 years with recurrent acute otitis media/otitis media with effusion, frequent upper respiratory airway infections and nasal obstruction | |

| Interventions | Adenoidectomy (n = 37), control group (n = 39) | |

| Outcomes | Measured at 12 and 24 months:

|

|

| Notes | 11% of the children were lost to follow up (8% in the adenoidectomy group and 13% in the control group) after 24 months follow up 35% of the children in the adenoidectomy group and 56% of the children in the control group had insertion of tympanostomy tubes. When those children still had tubes at the end of the trial they were excluded from analysis (8% in the adenoidectomy group and 3% in the control group) No intention‐to‐treat‐method was used for analysis No complications were reported by surgeons |

|

| Risk of bias | ||

| Bias | Authors' judgement | Support for judgement |

| Adequate sequence generation? | Low risk | Quote: “All children (...) received a number between 0‐105 randomly acquired by casting of lots. Children with even numbers came to belong to the adenoidectomy group and those with odd numbers to the control group.” |

| Allocation concealment? | Low risk | Quote: “All children (...) received a number between 0‐105 randomly acquired by casting of lots. Children with even numbers came to belong to the adenoidectomy group and those with odd numbers to the control group.” |

| Blinding? All outcomes | High risk | Quote: “(...) we were naturally aware of whether the children belonged to the A‐ or C‐group.” |

| Incomplete outcome data addressed? All outcomes | High risk | Quote: “Twenty‐nine children were omitted for reasons shown in Table 1, leaving 76 children to participate in the investigation.” Comment: these children were excluded after randomisation. The most common reasons were severe nasal obstruction and administrative mishaps. It is unclear whether the 29 omitted children were otherwise clinically similar to the 76 children included in the study. |

| Free of selective reporting? | Low risk | Comment: all outcomes are reported on (nasopharyngeal flora, improvement, unchanged or deterioration in episodes of common colds, purulent otitis media, serous otitis media, and nasal obstruction) |

| Free of other bias? | Unclear risk | Quote 1: “(...) data concerning frequency of illnesses were obtained retrospectively by interviews with the parents.” |

Characteristics of excluded studies [ordered by study ID]

| Study | Reason for exclusion |

|---|---|

| Black 1986 | Same study as Black 1990; first 100 children were analysed No additional data were published |

| Black 1990 | Did not specifically include nasal symptoms as an inclusion criteria or outcome measure |

| Bulman 1984 | Allocation: not concealed Participants: selection of patients not restricted by clear boundaries; not all had bilateral OME and bilateral similar deafness. Preoperative middle ear effusion only measured for 6 weeks. Outcome measures: ‘Adenoidectomy only’ versus ‘Control’ are the only two groups that can be compared; 15 versus 14 patients were allocated to those groups. Overall, results of the different intervention groups are impossible to differentiate. |

| Casselbrant 2009 | Did not specifically include nasal symptoms as an inclusion criteria or outcome measure |

| Dempster 1993 | Did not specifically include nasal symptoms as an inclusion criteria or outcome measure |

| Fiellau‐Nikolajsen 1980 | Did not specifically include nasal symptoms as an inclusion criteria or outcome measure |

| Fiellau‐Nikolajsen 1982 | Same study as Fiellau‐Nikolajsen 1980 |

| Gates 1987 | Did not specifically include nasal symptoms as an inclusion criteria or outcome measure |

| Gates 1988 | Same study as Gates 1987 |

| Gates 1989 | Same study as Gates 1987. Outcome measures: results are specified on adenoid size (in our study this is not an outcome). |

| Hammarén‐Malmi 2005 | Did not specifically include nasal symptoms as an inclusion criteria or outcome measure |

| Marshak 1980 | Allocation: non‐randomised controlled study |

| Mattila 2003 | Did not specifically include nasal symptoms as an inclusion criteria or outcome measure |

| Maw 1983 | Same study as Maw 1986 |

| Maw 1985a | Same study as Maw 1986 |

| Maw 1985b | Same study as Maw 1986 |

| Maw 1986 | Did not specifically include nasal symptoms as an inclusion criteria or outcome measure |

| Maw 1987 | Same study as Maw 1986 |

| Maw 1988 | Same study as Maw 1986 |

| Maw 1993 | This study was excluded because data from the adenoidectomy group could not be analysed separately from those undergoing adenotonsillectomy. The authors combined the adenoidectomy group and the adenotonsillectomy group because in the study 'Maw 1986' adenotonsillectomy appeared to have no additional benefit compared to adenoidectomy alone. |

| Maw 1994a | Same study as Maw 1993, long‐term effect |

| Maw 1994b | Same study as Maw 1986 |

| Nguyen 2004 | Did not specifically include nasal symptoms as an inclusion criteria or outcome measure |

| Paradise 1990 | Did not specifically include nasal symptoms as an inclusion criteria or outcome measure |

| Paradise 1999 | Did not specifically include nasal symptoms as an inclusion criteria or outcome measure |

| Roydhouse 1980 | Did not specifically include nasal symptoms as an inclusion criteria or outcome measure |

| Widemar 1982 | Allocation: randomisation process (used date of birth to randomise) Same study as Widemar 1985. The first year follow up of 44 children is presented. |

| Widemar 1985 | Allocation: randomisation process (used date of birth to randomise) Participants: only data from 59 children were used for analysis because 19 children were excluded after randomisation Intervention: a total of 13 and 22 tympanostomy tubes were inserted in groups A and C, respectively. They excluded the children that still had unilateral or bilateral tubes at the time of comparison. |

Characteristics of ongoing studies [ordered by study ID]

A Schilder, Netherlands.

| Trial name or title | NOA: Netherlands Adenoidectomy Study |

| Methods | RCT, follow up of 2 years |

| Participants | 111 children aged 1 to 6 years selected for adenoidectomy with or without myringotomy because of recurrent or chronic upper respiratory tract infections (common colds, rhinosinusitis) |

| Interventions | 1) Adenoidectomy with or without myringotomy within 6 weeks 2) Watchful waiting strategy |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome measure: ‐ Recurrent upper respiratory tract infections with or without fever (38 °C or higher) Secondary outcome measures: ‐ Acute otitis media and otitis media with effusion episodes ‐ Exhaled nitric oxide ‐ Nasopharyngeal flora ‐ Health related quality of life ‐ Cost‐effectiveness |

| Starting date | 1 April 2007 |

| Contact information | A. Schilder, Department of Otorhinolaryngology & Julius Center for Health Sciences and Primary Care, University Medical Center Utrecht, Utrecht, Netherlands |

| Notes | — |

Differences between protocol and review

This review is based on the protocol 'Adenoidectomy for recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms and middle ear disease in children up to 18 years of age' (van den Aardweg 2009). After finalising the first draft of the review in which we combined recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms and middle ear disease, there was a general consensus that the review would benefit from being split into two separate reviews; one looking at the effects of adenoidectomy on nasal symptoms (this review) and the other at the effect on otitis media (van den Aardweg 2010).

Further, some minor changes from the protocol have been carried out in this review. Quasi‐randomised trials are explicitly excluded because they have an increased risk of selection bias. The diagnosis of the participating children is more clearly described, i.e. "diagnosed with recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms or nasal obstruction alone" has been added to "children up to 18 years of age". Both the comparisons and the definition of non‐surgical management in the 'Types of interventions' section have been defined more clearly. Finally, next to the number of episodes with nasal discharge, we also added the number of days with symptoms per episode and per year with nasal discharge, and the proportion of children with recurrent episodes of nasal symptoms as a primary outcome.

Contributions of authors

Maaike van den Aardweg was lead author, selected eligible studies, assessed trial quality, performed data extraction, analysed and interpreted the data, drafted and revised the review and approved the final content.

Anne Schilder initiated the review, revised the review and approved the final content.

Ellen Herkert selected eligible studies, performed data extraction, analysed and interpreted the data, drafted the review and approved the final content.

Chantal Boonacker assessed trial quality, analysed the data, revised the review and approved the final content.

Maroeska Rovers initiated the review, analysed and interpreted the data, revised the review and approved the final content.

Sources of support

Internal sources

Department of Otorhinolaryngology, University Medical Center Utrecht, Netherlands.

Julius Center for Health Services and Primary Health Care, University Medical Center, Netherlands.

External sources

ZonMw (Netherlands Organisation for Health Research and Development), Netherlands.

Declarations of interest

At the time of publication Chantal Boonacker and Maaike van den Aardweg were involved in a Nederlands Onderzoek Adenotomie (NOA) trial entitled 'A RCT on the effectiveness of adenoidectomy in children with recurrent or chronic upper respiratory tract infections' (see 'Characteristics of ongoing studies').

Maroeska Rovers and Anne Schilder have participated in workshops and educational activities on otitis media for GlaxoSmithKline.

Edited (no change to conclusions)

References

References to studies included in this review

Koivunen 2004 {published data only}

- Koivunen P, Uhari M, Luotonen J, Kristo A, Raski R, Pokka T, et al. Adenoidectomy versus chemoprophylaxis and placebo for recurrent acute otitis media in children aged under 2 years: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2004;328(7438):487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rynnel‐Dagöo 1978 {published data only}

- Rynnel‐Dagöö B, Ahlbom A, Schiratzki H. Effects of adenoidectomy: a controlled two‐year follow‐up. Annals of Otology, Rhinology and Laryngology 1978;87(2 Part 1):272‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to studies excluded from this review

Black 1986 {published data only}

- Black N, Crowther J, Freeland A. The effectiveness of adenoidectomy in the treatment of glue ear: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Otolaryngology and Allied Sciences 1986;11(3):149‐55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Black 1990 {published data only}

- Black NA, Sanderson CF, Freeland AP, Vessey MP. A randomised controlled trial of surgery for glue ear. BMJ 1990;300(6739):1551‐6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bulman 1984 {published data only}

- Bulman CH, Brook SJ, Berry MG. A prospective randomized trial of adenoidectomy vs grommet insertion in the treatment of glue ear. Clinical Otolaryngology and Allied Sciences 1984;9(2):67‐75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Casselbrant 2009 {published data only}

- Casselbrant ML, Mandel EM, Rockette HE, Kurs‐Lasky M, Fall PA, Bluestone CD. Adenoidectomy for otitis media with effusion in 2‐3‐year‐old children. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 2009; Vol. Oct 09 [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Dempster 1993 {published data only}

- Dempster JH, Browning GG, Gatehouse SG. A randomized study of the surgical management of children with persistent otitis media with effusion associated with a hearing impairment. Journal of Laryngology and Otology 1993;107(4):284‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fiellau‐Nikolajsen 1980 {published data only}

- Fiellau‐Nikolajsen M, Falbe‐Hansen J, Knudstrup P. Adenoidectomy for middle ear disorders: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Otolaryngology and Allied Sciences 1980;5(5):323‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Fiellau‐Nikolajsen 1982 {published data only}

- Fiellau‐Nikolajsen M, Hojslet PE, Felding JU. Adenoidectomy for Eustachian tube dysfunction: long‐term results from a randomized controlled trial. Acta Oto‐Laryngologica. Supplement 1982;386:129‐31. [Google Scholar]

Gates 1987 {published data only}

- Gates GA, Avery CA, Prihoda TJ, Cooper JC. Effectiveness of adenoidectomy and tympanostomy tubes in the treatment of chronic otitis media with effusion. New England Journal of Medicine 1987;317(23):1444‐51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gates 1988 {published data only}

- Gates GA, Avery CA, Prihoda TJ. Effect of adenoidectomy upon children with chronic otitis media with effusion. Laryngoscope 1988;98(1):58‐63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gates 1989 {published data only}

- Gates GA, Avery CA, Cooper JC Jr, Prihoda TJ. Chronic secretory otitis media: effects of surgical management. Acta Oto‐Laryngologica. Supplement 1989;138:2‐32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Hammarén‐Malmi 2005 {published data only}

- Hammarén‐Malmi S, Saxen H, Tarkkanen J, Mattila PS. Adenoidectomy does not significantly reduce the incidence of otitis media in conjunction with the insertion of tympanostomy tubes in children who are younger than 4 years: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 2005;116(1):185‐9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Marshak 1980 {published data only}

- Marshak G, Neriah ZB. Adenoidectomy versus tympanostomy in chronic secretory otitis media. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. Supplement 1980;89(3 Part 2):316‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mattila 2003 {published data only}

- Mattila PS, Joki‐Erkkila VP, Kilpi T, Jokinen J, Herva E, Puhakka H. Prevention of otitis media by adenoidectomy in children younger than 2 years. Archives of Otolaryngology ‐ Head and Neck Surgery 2003;129(2):163‐8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maw 1983 {published data only}

- Maw AR. Chronic otitis media with effusion (glue ear) and adenotonsillectomy: prospective randomised controlled study. British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Ed) 1983;287(6405):1586‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maw 1985a {published data only}

- Maw AR. The long term effect of adenoidectomy on established otitis media with effusion in children. Auris Nasus Larynx 1985;12(Suppl 1):S234‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maw 1985b {published data only}

- Maw AR. Factors affecting adenoidectomy for otitis media with effusion (glue ear). Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 1985;78(12):1014‐8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maw 1986 {published data only}

- Maw AR, Herod F. Otoscopic, impedance, and audiometric findings in glue ear treated by adenoidectomy and tonsillectomy. A prospective randomised study. Lancet 1986;1(8495):1399‐402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maw 1987 {published data only}

- Maw AR. The effectiveness of adenoidectomy in the treatment of glue ear: a randomized controlled trial. Clinical Otolaryngology and Allied Sciences 1987;12(2):155‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maw 1988 {published data only}

- Maw AR, Parker A. Surgery of the tonsils and adenoids in relation to secretory otitis media in children. Acta Oto‐Laryngologica. Supplement 1988;454:202‐7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maw 1993 {published data only}

- Maw AR, Bawden R. Spontaneous resolution of severe chronic glue ear in children and the effect of adenoidectomy, tonsillectomy, and insertion of ventilation tubes (grommets). BMJ 1993;306(6880):756‐60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maw 1994a {published data only}

- Maw AR, Bawden R. The long term outcome of secretory otitis media in children and the effects of surgical treatment: a ten year study. Acta Oto‐Rhino‐Laryngologica Belgica 1994;48(4):317‐24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Maw 1994b {published data only}

- Maw AR, Bawden R. Does adenoidectomy have an adjuvant effect on ventilation tube insertion and thus reduce the need for re‐treatment?. Clinical Otolaryngology and Allied Sciences 1994;19(4):340‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nguyen 2004 {published data only}

- Nguyen LH, Manoukian JJ, Yoskovitch A, Al Sebeih KH. Adenoidectomy: selection criteria for surgical cases of otitis media. Laryngoscope 2004;114(5):863‐6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Paradise 1990 {published data only}

- Paradise JL, Bluestone CD, Rogers KD, Taylor FH, Colborn DK, Bachman RZ, et al. Efficacy of adenoidectomy for recurrent otitis media in children previously treated with tympanostomy‐tube placement. Results of parallel randomized and nonrandomized trials. JAMA 1990;263(15):2066‐73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Paradise 1999 {published data only}

- Paradise JL, Bluestone CD, Colborn DK, Bernard BS, Smith CG, Rockette HE, et al. Adenoidectomy and adenotonsillectomy for recurrent acute otitis media: parallel randomized clinical trials in children not previously treated with tympanostomy tubes. JAMA 1999;282(10):945‐53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Roydhouse 1980 {published data only}

- Roydhouse N. Adenoidectomy for otitis media with mucoid effusion. Annals of Otology, Rhinology, and Laryngology. Supplement 1980;89(3 Part 2):312‐5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Widemar 1982 {published data only}

- Widemar L, Rynnel‐Dagöö B, Schiratzki H, Svensson C. The effect of adenoidectomy on secretory otitis media. Acta Oto‐Laryngologica. Supplement 1982;386:132‐3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Widemar 1985 {published data only}

- Widemar L, Svensson C, Rynnel‐Dagöö B, Schiratzki H. The effect of adenoidectomy on secretory otitis media: a 2‐year controlled prospective study. Clinical Otolaryngology and Allied Sciences 1985;10(6):345‐50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References to ongoing studies

A Schilder, Netherlands {published data only}

- NOA: Netherlands Adenoidectomy Study. Ongoing study 1 April 2007.

Additional references

Burton 2009

- Burton MJ, Glasziou PP. Tonsillectomy or adeno‐tonsillectomy versus non‐surgical treatment for chronic/recurrent acute tonsillitis. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 1. [Art. No.: CD001802. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001802.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Handbook 2008

- Higgins JPT, Green S, editors. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions 5.0.0 [updated February 2008]. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008. Available from www.cochrane‐handbook.org.

Lous 2005

- Lous J, Burton MJ, Felding JU, Ovesen T, Rovers MM, Williamson I. Grommets (ventilation tubes) for hearing loss associated with otitis media with effusion in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005, Issue 1. [Art. No.: CD001801. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD001801.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

McDonald 2008

- McDonald S, Langton Hewer CD, Nunez DA. Grommets (ventilation tubes) for recurrent acute otitis media in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2008, Issue 4. [Art. No.: CD004741. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD004741.pub2] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

RevMan 2008 [Computer program]

- The Nordic Cochrane Centre. The Cochrane Collaboration. Review Manager (RevMan). Version 5.0. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre. The Cochrane Collaboration, 2008.

Rosenfeld 2000

- Rosenfeld RM, Bluestone CD. Chapter 18: Pathogenesis of otitis media. Evidence‐based otitis media. 2nd Edition. Hamilton: BC Decker, 2000:292. [Google Scholar]

Sagnelli 1990

- Sagnelli M, Marzullo C, Pollastrini L, Marullo MN. Secretory otitis media: current aspects and therapeutic role of adenoidectomy. Medicina‐Firenze 1990;10(1):16‐22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Schilder 2004

- Schilder AGM, Lok W, Rovers MM. International perspectives on management of acute otitis media: a qualitative review. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 2004;68(1):29‐36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

van den Aardweg 2009

- Aardweg MTA, Schilder AGM, Herkert E, Boonacker CWB, Rovers M. Adenoidectomy for recurrent or chronic nasal symptoms and middle ear disease in children up to 18 years of age. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009, Issue 2. [Art. No.: CD007810. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007810] [Google Scholar]

van den Aardweg 2010

- Aardweg MTA, Schilder AGM, Herkert E, Boonacker CWB, Rovers MM. Adenoidectomy for otitis media in children. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 1. [Art. No.: CD007810. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD007810] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]