Abstract

Context: β-Cell secretory capacity, a measure of functional β-cell mass, is often impaired in islet transplant recipients, likely because of a low engrafted β-cell mass, although calcineurin inhibitor toxicity is often cited as the explanation.

Objective: We sought to determine whether use of the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus was associated with reduced β-cell secretory capacity or with increased β-cell secretory demand independent of engrafted islet mass.

Design and Participants: We compared metabolic measures in five intraportal islet recipients vs. 10 normal controls and in seven portally-drained pancreas-kidney and eight nondiabetic kidney recipients vs. nine kidney donor controls. All transplant groups received comparable exposure to tacrolimus, and each transplant group was matched for kidney function to its respective control group.

Intervention and Main Outcome Measures: All participants underwent glucose-potentiated arginine testing where acute insulin responses to arginine (5 g) were determined under fasting (AIRarg), 230 mg/dl (AIRpot), and 340 mg/dl (AIRmax) clamp conditions, and AIRmax gives the β-cell secretory capacity. Insulin sensitivity (M/I) and proinsulin secretory ratios (PISRs) were assessed to determine whether tacrolimus increased β-cell secretory demand.

Results: Insulin responses were significantly lower than normal in the islet group for AIRarg (P < 0.05), AIRpot (P < 0.01), and AIRmax (P < 0.01), whereas responses in the pancreas-kidney and kidney transplant groups were not different than in the kidney donor group. M/I and PISRs were not different in any of the transplant vs. control groups.

Conclusions: Impaired β-cell secretory capacity in islet transplantation is best explained by a low engrafted β-cell mass and not by a deleterious effect of tacrolimus.

Impaired β-cell secretory capacity in islet transplantation is best explained by a low engrafted β-cell mass and not by a deleterious effect of tacrolimus.

Islet transplantation is an emerging β-cell replacement approach for type 1 diabetes that can restore insulin secretion and consequently enable the attainment of near-normal glycemic control in the absence of severe hypoglycemic events. However, more than one donor pancreas is usually required to achieve independence from exogenous insulin, and the majority of recipients require some insulin therapy by the second year after transplant (1). Our group (2) and others (3) have shown that even insulin-independent islet recipients may have a β-cell secretory capacity of only approximately 25% of normal, indicating a markedly reduced insulin secretory reserve that helps to explain the eventual return to insulin therapy. β-Cell secretory capacity provides the best estimate of functional β-cell mass and is derived from glucose potentiation of insulin release in response to a non-glucose secretagogue such as arginine (4). Increasing evidence supports the potential for early loss of transplanted islets before engraftment due to nonspecific inflammatory and thrombotic mechanisms (5), consistent with the finding of a low functional β-cell mass during secretory capacity testing.

Although a low engrafted β-cell mass may explain the impaired β-cell secretory capacity that can follow islet transplantation, an alternative hypothesis posits that the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus that is part of the immunosuppression regimen adversely affects the β-cell secretory capacity. Both cyclosporine and tacrolimus inhibit calcineurin-dependent gene transcription that leads to dose-dependent reductions in insulin mRNA, cellular insulin content, and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion in β-cell lines and rodent islets (6). Clinically, high doses of calcineurin inhibitors can be directly toxic to human islets (7) and epidemiological studies have linked both cyclosporine and tacrolimus to the development of posttransplant diabetes (8); however, the relevance of these findings to the present use of lower doses of calcineurin inhibitors is uncertain (9). Previous human studies examining the effect of calcineurin inhibitors on β-cell secretory capacity have been limited by the use of control groups that did not account for either the hyperinsulinemia that results from systemic venous drainage of pancreaticoduodenal grafts (10,11,12) or the impaired kidney function in the transplant recipients that affects insulin clearance (10,11,12,13).

The present study was designed to determine whether the transplantation of a 100% β-cell mass would result in an impaired β-cell secretory capacity attributable to use of modern, lower dose, tacrolimus-based immunosuppression. To address this objective under as controlled conditions as possible, we studied whole pancreas recipients with portal venous drainage of their pancreaticoduodenal grafts that allows for physiological extraction of insulin by the liver and avoids confounding by the hyperinsulinemia found in recipients with systemic venous drainage (14). To control for any effect of pancreatic denervation on β-cell secretory capacity, we also studied a group of nondiabetic kidney transplant recipients whose native pancreases were exposed to the same tacrolimus-based immunosuppression. Finally, both the pancreas-kidney and nondiabetic kidney transplant groups were matched for kidney mass and function to a control group of healthy kidney donors that further eliminates confounding by altered renal insulin clearance (15).

Subjects and Methods

Subjects

This report includes intraportal islet transplant recipients (n = 5) who represent insulin-independent subjects that formed part of an earlier report that included C-peptide responses to the glucose-potentiated arginine test, compared with normal control subjects (n = 6) (2). The normal control group has been expanded (n = 10) in the present report, with subjects matched for sex, age, body mass index (BMI), and serum creatinine to the islet recipients. The pancreas-kidney transplant recipients (n = 7) were selected for having portal rather than the more common systemic venous drainage of their pancreaticoduodenal grafts, which maintains physiological hepatic insulin extraction as in islet recipients (16). The kidney transplant recipients (n = 8) were matched for sex, age, BMI, and serum creatinine to the pancreas-kidney recipients. None of the pancreas-kidney or kidney transplant recipients had experienced a known rejection episode. The kidney donor control subjects (n = 9) were matched for sex, age, BMI, and serum creatinine to the pancreas-kidney and kidney transplant recipients. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pennsylvania, and all subjects gave their written informed consent to participate.

All subjects were admitted to the University of Pennsylvania Clinical and Translational Research Center the afternoon before study and fasted overnight after 2000 h for 12 h before testing. By 0700 h, one catheter was placed in an antecubital vein for infusions, and one catheter was placed retrograde in a hand vein for blood sampling, with the hand placed in a thermoregulated box (∼50 C) to arterialize the venous blood.

Glucose-potentiated arginine test

After at least 20 min of acclimatization to the iv catheters, baseline blood samples were taken at 5 and 1 min before the injection of 5 g of 10% arginine over a 1-min period starting at t = 0. Additional blood samples were collected at t = 2, 3, 4, and 5 min after injection. Beginning at t = 10 min, a hyperglycemic clamp technique (17) using a variable rate infusion of 20% glucose was performed to achieve a plasma glucose concentration of approximately 230 mg/dl. Blood samples were taken every 5 min, centrifuged, and measured at bedside with a portable glucose analyzer (YSI 1500 Sidekick; Yellow Springs Instruments, Yellow Springs, OH) to adjust the infusion rate and achieve the desired plasma glucose concentration. After 45 min of the glucose infusion (at t = 55 min), a 5-g arginine pulse was injected again with identical blood sampling. Then, a 2-h period with no glucose infusion took place to allow glucose levels to return to baseline. At the end of the 2-h period, a hyperglycemic clamp was performed to achieve a plasma glucose concentration of approximately 340 mg/dl. After 45 min of the glucose infusion, a 5-g arginine pulse was injected again with identical blood sampling.

Biochemical analysis

All samples were collected on ice into tubes containing EDTA, trasylol, and leupeptin; centrifuged at 4 C; separated; and frozen at −80 C for subsequent analysis. Plasma glucose was measured in duplicate by the glucose oxidase method using an automated glucose analyzer (YSI 2300; Yellow Springs Instruments). Plasma immunoreactive insulin, C-peptide, proinsulin, and glucagon were measured in duplicate by double-antibody RIAs [Linco Research, St. Charles, MO (now Millipore, Billerica, MA)]. The insulin assay has a specificity of 100% for human insulin and does not cross-react with intact or des-31,32 human proinsulin (<0.2%). The proinsulin assay has a specificity of 100% for intact human proinsulin and 95% for des-31,32 human proinsulin, and it does not cross-react with human insulin (<0.1%).

Calculations and statistics

The acute insulin, C-peptide, proinsulin, and glucagon responses to arginine (AIRarg, ACRarg, APRarg, and AGRarg, respectively) were calculated as the mean of the 2-, 3-, 4-, and 5-min values minus the mean of the baseline values (17). Acute responses during the 230 mg/dl glucose clamp enable determination of glucose potentiation of arginine-induced insulin (AIRpot), C-peptide (ACRpot), and proinsulin (APRpot) release, and glucose inhibition of arginine-induced glucagon (AGRinh) release. Acute responses during the 340 mg/dl glucose clamp allow for determination of the maximum arginine-induced insulin (AIRmax), C-peptide (ACRmax), and proinsulin (APRmax) release, i.e. β-cell secretory capacity, and of the minimum arginine-induced glucagon (AGRmin) release (18).

Insulin sensitivity (M/I) was determined by dividing the mean glucose infusion rate required during the 230 mg/dl glucose clamp (M) by the mean prestimulus insulin level (I) between 40 and 45 min of the glucose infusion (19); the disposition index (DI) was then calculated as the product of AIRarg and M/I (19). The proinsulin-to-insulin (PI/I) ratio was calculated as the molar concentration of proinsulin divided by the molar concentration of insulin × 100. Estimation of the PI/I ratio within the secretory granules of the β-cell is most reliable after acute stimulation of secretion (20); therefore, we examined the proinsulin secretory ratio (PISR) in response to each injection of arginine from the respective acute PI/I responses to arginine (19).

All data are expressed as mean ± se. Comparison of results between the islet transplant recipients and normal control subjects was performed with unpaired Student’s t tests; comparison of results across the pancreas-kidney, kidney transplant, and kidney donor control groups was performed by one-way ANOVA, and when significant differences were found, comparisons between groups were performed with the least significant difference test using Statistica software (StatSoft, Inc., Tulsa, OK). Significance was considered at P < 0.05 (two-tailed).

Results

Subject characteristics

All five groups studied were of comparable gender distribution, age, and BMI (Table 1). The islet and pancreas-kidney transplant groups had experienced similarly long durations of type 1 diabetes before transplantation. The islet recipients had received 14,313 ± 2,237 islet equivalents per kilogram body weight via one or two intraportal infusions between 3 and 12 months before study. The pancreas recipients had received a pancreaticoduodenal graft with portal venous drainage between 3 and 48 months before study, six as a simultaneous pancreas-kidney transplant and one as a pancreas-after-kidney. The nondiabetic kidney recipients were transplanted between 6 and 60 months before study. Kidney function, as indicated by serum creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate (21), was the same in the islet transplant and normal groups, and in the pancreas-kidney, kidney transplant, and kidney donor groups. Overall, kidney function was approximately two thirds in the pancreas-kidney, kidney transplant, and kidney donor groups with only one functioning kidney, compared with the islet transplant and normal groups (P < 0.01 for all comparisons). Glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and fasting glucose were significantly higher in the islet transplant compared with the normal group (P < 0.01 for both) and were not different across the pancreas-kidney, kidney transplant, and kidney donor groups. Fasting insulin was not significantly elevated in any of the groups, although fasting C-peptide was higher in the pancreas-kidney and kidney transplant groups compared with the kidney donor group (P < 0.01 for both). The three transplant groups had comparable 12-h blood trough levels of tacrolimus, consistent with standard targets of 6–10 μg/liter. The levels of tacrolimus in the islet recipients were multiplied by a portal-to-systemic ratio of 1.54 to better approximate the exposure of the intrahepatic islets to tacrolimus (22), with the actual peripheral levels consistent with low-dose targets of 3–6 μg/liter. All five islet recipients also received rapamycin dosed to 24-h blood trough levels of 8–12 μg/liter. All seven pancreas-kidney recipients received prednisone 5 mg daily, and six received mycophenolate mofetil 500-1500 mg divided daily. Five of the kidney recipients received prednisone 5 mg daily, and all eight received mycophenolate mofetil 500-2000 mg divided daily.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the islet recipients and their normal control group, and the pancreas-kidney and kidney recipients and their kidney donor control group

| Islet recipients | Normal controls | Pancreas-kidney recipients | Kidney recipients | Kidney donor controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (M/F) | 3/2 | 5/5 | 3/4 | 4/4 | 4/5 |

| Age (yr) | 44 ± 4 | 40 ± 3 | 40 ± 2 | 45 ± 4 | 45 ± 4 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21 ± 1 | 24 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 | 23 ± 1 | 24 ± 1 |

| T1D duration (yr) | 34 ± 3 | 31 ± 2 | |||

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.9 ± 0.1 | 0.9 ± 0.0 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.1 | 1.3 ± 0.1 |

| eGFR (ml/min per 1.73 m2)a | 96 ± 14 | 91 ± 5 | 64 ± 4 | 61 ± 5 | 59 ± 4 |

| HbA1c (%) | 6.1 ± 0.2b | 5.3 ± 0.1 | 5.0 ± 0.2 | 5.2 ± 0.2 | 5.1 ± 0.1 |

| Fasting glucose (mg/dl) | 100 ± 6b | 80 ± 2 | 85 ± 3 | 82 ± 2 | 84 ± 1 |

| Fasting insulin (μU/ml) | 7.1 ± 0.9 | 5.5 ± 1.1 | 9.5 ± 1.0 | 7.6 ± 0.8 | 7.4 ± 0.6 |

| Fasting C-peptide (ng/ml) | 0.78 ± 0.18 | 1.12 ± 0.18 | 2.26 ± 0.22c | 2.31 ± 0.23c | 1.50 ± 0.09 |

| Tacrolimus (μg/liter)d | 5.9 ± 0.4 | 9.0 ± 0.8 | 6.7 ± 0.5 |

Data are presented as means ± se. T1D, Type 1 diabetes; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; M, male; F, female. To convert creatinine to μmol/liter, multiply by 88.40; to convert glucose to mmol/liter, multiply by 0.05551; to convert insulin to pmol/liter, multiply by 7.1750; and to convert C-peptide to nmol/liter, multiply by 0.3310.

Estimated by the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease equation (Ref. 21).

P < 0.01 vs. normal control group.

P < 0.01 vs. kidney donor control group.

Adjusted for a portal-to-systemic ratio of 1.54 in islet recipients (Ref. 22).

Glucose, insulin, and C-peptide

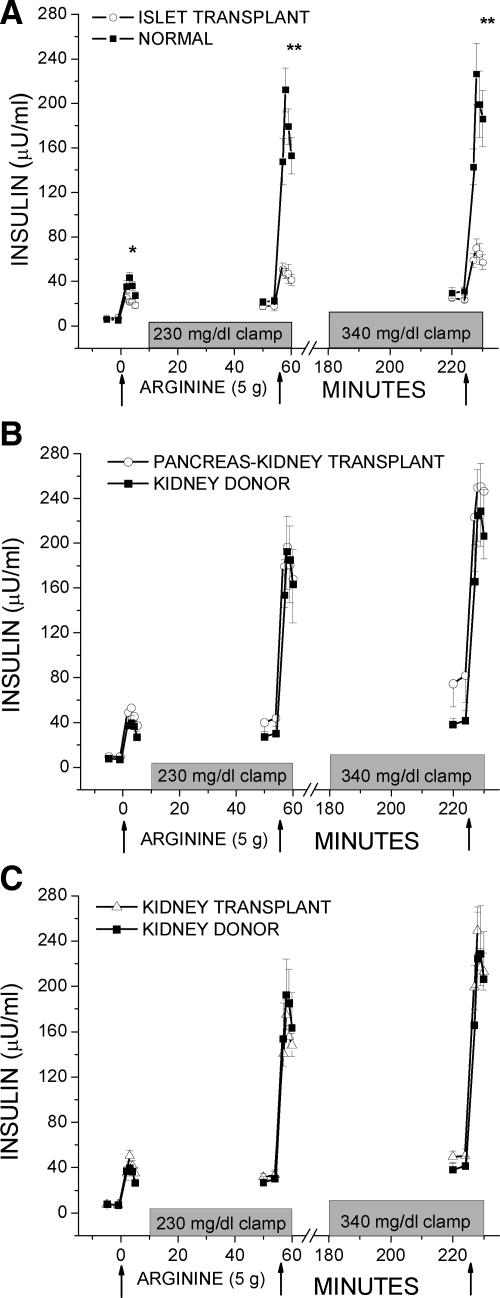

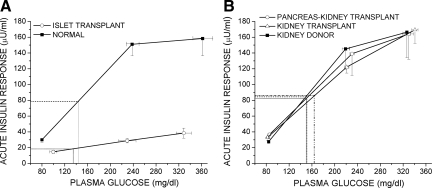

Fasting glucose levels given in Table 1 are the prestimulus glucose levels before the first injection of arginine. Overall, the prestimulus glucose during the approximately 230 mg/dl clamp was 228 ± 3 mg/dl and during the approximately 340 mg/dl clamp was 339 ± 6 mg/dl; neither was significantly different across groups. Figure 1A and Fig. 2A demonstrate the AIRs to the injection of arginine that were significantly lower in the islet vs. normal group for AIRarg (14.7 ± 2.1 vs. 30.0 ± 3.3 μU/ml; P < 0.05), AIRpot (28.7 ± 2.8 vs. 151 ± 15 μU/ml; P < 0.01), and AIRmax (38.4 ± 6.4 vs. 158 ± 22 μU/ml; P < 0.01). In contrast, Fig. 1, B and C, and Fig. 2B depict the AIRs in the pancreas-kidney and kidney transplant groups that were not different than responses in the kidney donor group for AIRarg [36.6 ± 5.5 vs. 33.0 ± 3.8 vs. 27.6 ± 2.4 μU/ml; not significant (NS)], AIRpot (139 ± 27 vs. 122 ± 8 vs. 145 ± 26 μU/ml; NS), and AIRmax (164 ± 32 vs. 169 ± 17 vs. 166 ± 32 μU/ml; NS). C-peptide responses were reduced similarly as the insulin responses in the islet recipients and have previously been reported (2). C-peptide responses were also similarly matched as the insulin responses across the pancreas-kidney, kidney transplant, and kidney donor groups for ACRarg (1.90 ± 0.35 vs. 2.10 ± 0.24 vs. 1.82 ± 0.17 ng/ml; NS), ACRpot (6.72 ± 0.97 vs. 6.50 ± 0.39 vs. 6.15 ± 0.61 ng/ml; NS), and ACRmax (7.04 ± 1.00 vs. 9.32 ± 1.68 vs. 6.09 ± 0.63; NS).

Figure 1.

Plasma insulin levels in response to bolus injections of arginine (arrows) administered under fasting, 230 mg/dl hyperglycemic clamp, and 340 mg/dl hyperglycemic clamp conditions. A, The AIRs to arginine were lower in the islet transplant compared with the normal control group. B and C, The AIRs to arginine were not different in either the pancreas-kidney or kidney transplant compared with the kidney donor control group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Figure 2.

AIRs to arginine as a function of the prestimulus plasma glucose concentration (18). The glucose-potentiation slope (GPS), calculated as the difference in the AIR at fasted and 230 mg/dl glucose levels divided by the difference in plasma glucose, is impaired in the islet vs. normal group (0.11 ± 0.01 vs. 0.76 ± 0.07; P < 0.0001; panel A), but not in the pancreas-kidney or kidney transplant vs. kidney donor group (0.71 ± 0.16 vs. 0.64 ± 0.04 vs. 0.90 ± 0.20; NS). β-Cell sensitivity to glucose is determined as the PG50, the plasma glucose level at which half-maximal insulin secretion was achieved, using the y-intercept (b) of the GPS to solve the equation AIRmax/2 = GPS × PG50 + b as represented by the dashed lines in panels A and B. Because the impairment of GPS in the islet group was proportional to the reduction in AIRmax, no difference existed in PG50 between the islet vs. normal groups (134 ± 21 vs. 143 ± 9 mg/dl; NS; panel A), nor did any differences exist in PG50 across the pancreas-kidney, kidney transplant, and kidney donor groups (148 ± 13 vs. 163 ± 10 vs. 148 ± 7 mg/dl; NS; panel B).

Insulin sensitivity

The glucose infusion rates (M), second phase insulin levels (I), and the resulting estimates of insulin sensitivity (M/I) from the 230 mg/dl clamp were not different in the islet vs. normal group or in the pancreas-kidney and kidney transplant vs. kidney donor group (Table 2). Thus, the disposition index (DI) relating insulin secretion and sensitivity was decreased only in the islet (P < 0.05) group with the impaired AIRarg.

Table 2.

Glucose infusion rate (M), second-phase insulin (I), and insulin sensitivity (M/I) measures from the approximately 230 mg/dl clamp, as well as the DI

| Islet recipients | Normal controls | Pancreas-kidney recipients | Kidney recipients | Kidney donor controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (mg/kg/min) | 7.0 ± 1.5 | 9.2 ± 0.5 | 9.7 ± 0.9 | 9.5 ± 0.7 | 8.3 ± 0.3 |

| I (μU/ml) | 18 ± 3 | 22 ± 3 | 42 ± 11 | 33 ± 4 | 29 ± 5 |

| M/I (mg/kg per min/μU/ml) | 0.41 ± 0.06 | 0.51 ± 0.08 | 0.31 ± 0.07 | 0.31 ± 0.03 | 0.41 ± 0.09 |

| DI (mg/kg/min)a | 6.2 ± 1.6b | 14.9 ± 2.8 | 9.5 ± 1.3 | 10.2 ± 1.4 | 10.2 ± 1.7 |

Proinsulin and proinsulin secretory ratios (PISRs)

Fasting proinsulin levels are given in Table 3, and were not different between the islet and normal group, but were higher in the pancreas-kidney, though not the kidney transplant, vs. the kidney donor group (P < 0.05). The APRs to the injection of arginine followed a similar pattern as the insulin responses, were significantly lower in the islet vs. normal group for APRarg (1.37 ± 1.09 vs. 2.89 ± 0.70 pmol/liter; P < 0.05), APRpot (2.22 ± 0.75 vs. 21.2 ± 3.3 pmol/liter; P < 0.01), and APRmax (2.62 ± 0.74 vs. 21.0 ± 3.2 pmol/liter; P < 0.01), and were comparable across the pancreas-kidney, kidney transplant and kidney donor groups for APRarg (2.88 ± 0.92 vs. 4.35 ± 0.74 vs. 3.28 ± 0.57 pmol/liter; NS), APRpot (19.0 ± 3.9 vs. 18.8 ± 3.0 vs. 23.5 ± 5.1 pmol/liter; NS), and APRmax (22.8 ± 6.0 vs. 21.0 ± 3.5 vs. 22.0 ± 4.9 pmol/liter; NS).

Table 3.

Proinsulin and proinsulin secretory ratios (PISRs)

| Islet recipients | Normal controls | Pancreas-kidney recipients | Kidney recipients | Kidney donor controls | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting proinsulin (pmol/liter) | 9.8 ± 3.2 | 7.8 ± 1.1 | 9.9 ± 1.0a | 8.2 ± 1.7 | 5.0 ± 0.8 |

| Fasting proinsulin:insulin (%) | 18.0 ± 3.2 | 22.7 ± 3.0 | 14.0 ± 1.2 | 15.5 ± 2.6 | 9.5 ± 1.6 |

| PISR (%) | |||||

| Fasting | 1.4 ± 1.1 | 1.4 ± 0.2 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.4 | 1.7 ± 0.2 |

| 230 mg/dl | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.3 | 2.3 ± 0.3 |

| 340 mg/dl | 1.1 ± 0.4 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 2.0 ± 0.3 | 1.8 ± 0.3 | 1.9 ± 0.3 |

Data are presented as means ± se.

P < 0.05 vs. kidney donor control group.

Fasting PI/I ratios are also presented in Table 3 and were not different between the islet and normal groups, or across the pancreas-kidney, kidney transplant, and kidney donor groups. PISRs were similar in the islet transplant and normal groups and in the pancreas-kidney, kidney transplant and kidney donor groups under fasting, approximately 230 mg/dl, and approximately 340 mg/dl glucose conditions (Table 3).

Glucagon

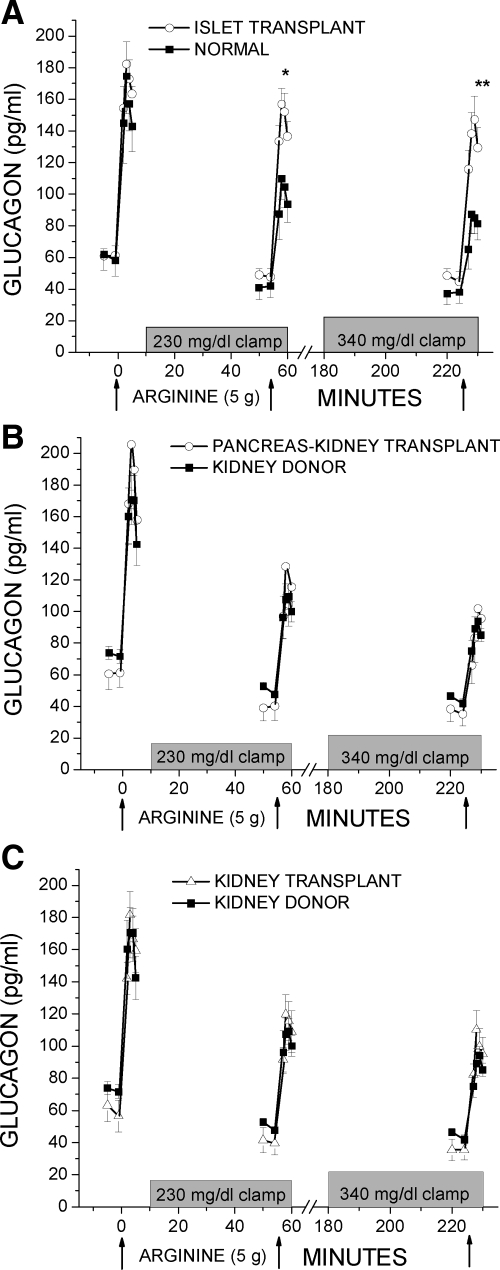

Fasting glucagon levels were similar between the islet and normal groups (61 ± 5 vs. 60 ± 10 pg/ml) and across the pancreas-kidney, kidney transplant, and kidney donor groups (61 ± 10 vs. 60 ± 10 vs. 73 ± 4 pg/ml). In Fig. 3A, the AGRarg was not different in the islet group vs. the normal group (107 ± 8 vs. 95 ± 12 pg/ml; NS), but was significantly greater in the islet vs. normal group under approximately 230 mg/dl (96 ± 11 vs. 58 ± 7 pg/ml; P < 0.05) and approximately 340 mg/dl (86 ± 12 vs. 42 ± 5 pg/ml; P < 0.01) clamp conditions. In contrast, Fig. 3, B and C, demonstrates AGRs in the pancreas-kidney and kidney transplant groups that were not different than in the kidney donor group for AGRarg (119 ± 18 vs. 103 ± 4 vs. 88 ± 12 pg/ml; NS); AGRinh (72 ± 8 vs. 68 ± 7 vs. 53 ± 9 pg/ml; NS), and AGRmin (50 ± 7 vs. 61 ± 7 vs. 42 ± 7 pg/ml; NS).

Figure 3.

Plasma glucagon levels in response to bolus injections of arginine (arrows) administered under fasting, 230 mg/dl hyperglycemic clamp, and 340 mg/dl hyperglycemic clamp conditions. A, The AGRs to arginine were greater in the islet transplant compared with the normal control group under hyperglycemic clamp conditions. B and C, The AGRs to arginine were not different in either the pancreas-kidney or kidney transplant compared with the kidney donor control group. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

Discussion

This study assessed β-cell secretory capacity in transplant recipients appropriately matched to their respective control groups for both portal insulin delivery and kidney mass and function, factors critical to the metabolism of insulin through hepatic extraction and renal clearance. The results indicate that although the β-cell secretory capacity is reduced in islet transplant recipients (2,3), it is normal in whole pancreas and nondiabetic kidney transplant recipients also receiving modern tacrolimus-based immunosuppression. Furthermore, none of the transplant groups exhibited insulin resistance or increased proinsulin secretion, which suggests that the immunosuppression regimen may not markedly increase demand on the β-cell to secrete insulin. Thus, the impaired β-cell secretory capacity in islet transplantation may not be attributable to a deleterious effect of tacrolimus and remains best explained by a low engrafted β-cell mass.

There are several possible explanations for why a deleterious effect of tacrolimus on β-cell secretory capacity was not seen in the transplant groups studied here. First, in vitro effects seen in β-cell lines and rodent islets, and even in vivo effects seen in rodents, may not translate to similar effects in vivo in humans. Importantly, human islets are less susceptible to toxic agents than rodent islets (23). Moreover, an earlier in vivo study failed to find a detrimental effect of cyclosporine on iv glucose tolerance or insulin secretion in human subjects (24), but the negative findings were dismissed because testing of β-cell secretory capacity was not performed (10). Our results support these earlier in vivo findings in humans by demonstrating no effect of the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus on β-cell secretory capacity.

Second, the β-cell toxic effect of calcineurin inhibitors is clearly dose-dependent (8), and increasing experience with immunosuppression regimens has resulted in the use of lower doses of tacrolimus (9), such as reported here, than when this agent was first introduced (25). Historically, 12-h trough levels of tacrolimus were set at 12–20 μg/liter and, not uncommonly, would result in levels above 35 μg/liter associated with reversible hyperglycemia and biopsy evidence of β-cell cytoplasmic vacuolization (7). In contrast, a recent randomized trial in kidney transplantation reported a similarly low incidence of posttransplant diabetes in both calcineurin inhibitor and calcineurin inhibitor-free arms (26). Although the present use of lower doses of tacrolimus may not be toxic to β-cells residing in a pancreas, it remains possible that even low-level calcineurin inhibitor exposure could adversely affect isolated islets transplanted outside the milieu of an intact pancreas.

Another objective of this study was to determine whether present tacrolimus-based immunosuppression is associated with increased β-cell demand for insulin secretion. We did not find a significant reduction in insulin sensitivity (M/I) in any of the transplant groups, although mean M/I values were lower in all transplant groups relative to their respective control groups, and so it is possible that an effect might have been apparent if we employed a more conventional method to assess insulin sensitivity such as the euglycemic clamp. That we may have missed a small effect of the immunosuppression regimen on insulin sensitivity is also suggested by the higher fasting C-peptide concentrations in the pancreas-kidney and kidney transplant groups, although fasting insulin was not different. Nevertheless, studies using the euglycemic clamp in nondiabetic kidney transplant recipients have demonstrated that patients receiving no more than physiological doses of glucocorticoid (≤5 mg prednisone) together with calcineurin inhibitors have normal insulin sensitivity (12,27), results that are consistent with our findings.

This study was not designed to assess for any possible effect of rapamycin on insulin secretion or sensitivity because rapamycin was used only in the small cohort of islet, and not pancreas-kidney or kidney, recipients. Supratherapeutic doses of rapamycin impair insulin secretion from human islets in vitro (28), whereas therapeutic levels of rapamycin improve β-cell insulin content and insulin secretion in human islets in vitro and in minipigs in vivo (29). Also, rapamycin impairs tissue sensitivity to insulin in the rat (30) but has been shown to increase insulin-mediated glucose disposal in humans (31). Most importantly, clinical studies of rapamycin and tacrolimus combination therapy without glucocorticoids in non-islet transplant populations have reported an extremely low incidence of posttransplant diabetes (32,33), supporting the likely low risk of these agents disturbing glucose homeostasis when dosed appropriately in humans.

Excessive secretion of proinsulin relative to insulin, resulting in an elevated molar ratio of PI/I, can accompany increased β-cell demand with recruitment of immature secretory granules containing an abundance of incompletely processed proinsulin. Curiously, fasting proinsulin levels were greater in the pancreas-kidney than control group, a previously reported finding (34) that might be explained by denervation of the pancreaticoduodenal graft. More important in this study, neither fasting PI/I ratios nor PISRs in response to arginine were increased in any of the transplant groups, indicating appropriate processing and release of proinsulin. Although the decreased β-cell secretory capacity in the islet recipients might be expected to result in inappropriate proinsulin secretion (35), these subjects may have been protected by the absence of hyperglycemia (36) as evidenced by their fasting glucose and HbA1c levels. This agrees with data reported by McDonald et al. (37) where basal PI/I ratios were not increased in normoglycemic islet recipients. Thus, a reduced β-cell secretory capacity alone may not be sufficient for secreting incompletely processed proinsulin but may require the addition of chronic hyperglycemia.

Lastly, the islet group exhibited impaired glucose inhibition of arginine-induced glucagon secretion. The observed increase in glucagon release during hyperglycemia could have originated from the transplanted islets, the native pancreas, or both. Recipients of systemically drained pancreas grafts have also demonstrated impaired regulation of arginine-induced glucagon secretion (11), an effect likely attributable to absent first-pass hepatic extraction of glucagon originating from the graft. Here, the portally drained pancreas recipients demonstrated normal glucose inhibition of arginine-induced glucagon release, evidencing appropriate graft α-cell secretion and native α-cell regulation by the transplanted pancreas.

In conclusion, these data support that our previous finding of impaired β-cell secretory capacity in islet transplant recipients is best explained by a low engrafted β-cell mass, and not by a deleterious effect of the calcineurin inhibitor tacrolimus, because β-cell secretory capacity was normal in pancreas-kidney and kidney transplant recipients receiving comparable doses of tacrolimus. Additionally, insulin sensitivity and proinsulin secretion were not different in the transplant groups compared with controls, providing further evidence against a markedly deleterious effect of low doses of tacrolimus on β-cell secretory demand in vivo in humans. Recent clinical trials in pancreas and kidney transplantation of steroid and calcineurin inhibitor-free regimens have experienced an increased incidence of acute rejection (38,39,40), suggesting for now that in the absence of steroids, calcineurin inhibitors may be an indispensable part of the immunosuppression regimen. Thus, the implication of the present study is that β-cell toxicity may not be an appropriate justification for the use of calcineurin inhibitor-free immunosuppression, particularly in the context of islet transplantation where treatment of acute rejection is not yet feasible.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to the nursing staff of the Penn Clinical and Translational Research Center for their subject care and technical assistance, to Dr. Heather Collins of the Penn Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center for performance of the RIAs, and to Huong-Lan Nguyen for laboratory assistance.

Footnotes

This work was supported by the Juvenile Diabetes Research Foundation and by Public Health Services Research Grants P30-DK-19525 (Penn Diabetes Endocrinology Research Center Pilot Award to M.R.R.), UL1-RR-024134 (Penn Clinical and Translational Research Center), and U42-RR-016600 (to A.N.) from the National Institutes of Health.

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online January 22, 2010

Abbreviations: ACR, Acute C-peptide response; AGR, acute glucagon response; AIR, acute insulin response; APR, acute proinsulin response; arg, arginine; BMI, body mass index; DI, disposition index; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; M/I, mean glucose infusion rate/mean prestimulus insulin level; NS, not significant; PI/I, proinsulin-to-insulin (ratio); PISR, proinsulin secretory ratio.

References

- Shapiro AM, Ricordi C, Hering BJ, Auchincloss H, Lindblad R, Robertson RP, Secchi A, Brendel MD, Berney T, Brennan DC, Cagliero E, Alejandro R, Ryan EA, DiMercurio B, Morel P, Polonsky KS, Reems JA, Bretzel RG, Bertuzzi F, Froud T, Kandaswamy R, Sutherland DE, Eisenbarth G, Segal M, Preiksaitis J, Korbutt GS, Barton FB, Viviano L, Seyfert-Margolis V, Bluestone J, Lakey JR 2006 International trial of the Edmonton protocol for islet transplantation. N Engl J Med 355:1318–1330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickels MR, Schutta MH, Markmann JF, Barker CF, Naji A, Teff KL 2005 β-Cell function following human islet transplantation for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes 54:100–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keymeulen B, Gillard P, Mathieu C, Movahedi B, Maleux G, Delvaux G, Ysebaert D, Roep B, Vandemeulebroucke E, Marichal M, In 't Veld P, Bogdani M, Hendrieckx C, Gorus F, Ling Z, van Rood J, Pipeleers D 2006 Correlation between β cell mass and glycemic control in type 1 diabetic recipients of islet cell graft. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 103:17444–17449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahn SE, Carr DB, Faulenbach MV, Utzschneider KM 2008 An examination of β-cell function measures and their potential use for estimating β-cell mass. Diabetes Obes Metab 10 (Suppl 4):63–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson O, Eich T, Sundin A, Tibell A, Tufveson G, Andersson H, Felldin M, Foss A, Kyllönen L, Langstrom B, Nilsson B, Korsgren O, Lundgren T 2009 Positron emission tomography in clinical islet transplantation. Am J Transplant 9:2816–2824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paty BW, Harmon JS, Marsh CL, Robertson RP 2002 Inhibitory effects of immunosuppressive drugs on insulin secretion from HIT-T15 cells and Wistar rat islets. Transplantation 73:353–357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drachenberg CB, Klassen DK, Weir MR, Wiland A, Fink JC, Bartlett ST, Cangro CB, Blahut S, Papadimitriou JC 1999 Islet cell damage associated with tacrolimus and cyclosporine: morphological features in pancreas allograft biopsies and clinical correlation. Transplantation 68:396–402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montori VM, Basu A, Erwin PJ, Velosa JA, Gabriel SE, Kudva YC 2002 Posttransplantation diabetes. Diabetes Care 25:583–592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekberg H, Tedesco-Silva H, Demirbas A, Vítko S, Nashan B, Gürkan A, Margreiter R, Hugo C, Grinyó JM, Frei U, Vanrenterghem Y, Daloze P, Halloran PF 2007 Reduced exposure to calcineurin inhibitors in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 357:2562–2575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teuscher AU, Seaquist ER, Robertson RP 1994 Diminished insulin secretory reserve in diabetic pancreas transplant and nondiabetic kidney transplant recipients. Diabetes 43:593–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christiansen E, Tibell A, Vølund A, Rasmussen K, Groth CG, Holst JJ, Pedersen O, Christensen NJ, Madsbad S 1996 Pancreatic endocrine function in recipients of segmental and whole pancreas transplantation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 81:3972–3979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillard P, Vandemeulebroucke E, Keymeulen B, Pirenne J, Maes B, De Pauw P, Vanrenterghem Y, Pipeleers D, Mathieu C 2009 Functional β-cell mass and insulin sensitivity is decreased in insulin-independent pancreas-kidney recipients. Transplantation 87:402–407 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez LA, Lehmann R, Luzi L, Battezzati A, Angelico MC, Ricordi C, Tzakis A, Alejandro R 1999 The effects of maintenance doses of FK506 versus cyclosporin A on glucose and lipid metabolism after orthotopic liver transplantation. Transplantation 68:1532–1541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diem P, Abid M, Redmon JB, Sutherland DE, Robertson RP 1990 Systemic venous drainage of pancreas allografts as independent cause of hyperinsulinemia in type 1 diabetic recipients. Diabetes 39:534–540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubenstein AH, Mako ME, Horwitz DL 1975 Insulin and kidney. Nephron 15:306–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier JJ, Hong-McAtee I, Galasso R, Veldhuis JD, Moran A, Hering BJ, Butler PC 2006 Intrahepatic transplanted islets in humans secrete insulin in a coordinate pulsatile manner directly into the liver. Diabetes 55:2324–2332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward WK, Halter JB, Beard JC, Porte Jr D 1984 Adaptation of B and A cell function during prolonged glucose infusion in human subjects. Am J Physiol 246:E405–E411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaquist ER, Robertson RP 1992 Effects of hemipancreatectomy on pancreatic α and β cell function in healthy human donors. J Clin Invest 89:1761–1766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guldstrand M, AhrénB, Adamson U 2003 Improved β-cell function after standardized weight reduction in severely obese subjects. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 284:E557–E565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horwitz DL, Starr JI, Mako ME, Blackard WG, Rubenstein AH 1975 Proinsulin, insulin, and C-peptide concentrations in human portal and peripheral blood. J Clin Invest 55:1278–1283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D 1999 A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Ann Intern Med 130:461–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai NM, Goss JA, Deng S, Wolf BA, Markmann E, Palanjian M, Shock AP, Feliciano S, Brunicardi FC, Barker CF, Naji A, Markmann JF 2003 Elevated portal vein drug levels of sirolimus and tacrolimus in islet transplant recipients: local immunosuppression or islet toxicity? Transplantation 76:1623–1625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eizirik DL, Pipeleers DG, Ling Z, Welsh N, Hellerström C, Andersson A 1994 Major species differences between humans and rodents in the susceptibility to pancreatic β-cell injury. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:9253–9256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson RP, Franklin G, Nelson L 1989 Intravenous glucose tolerance and pancreatic islet β-cell function in patients with multiple sclerosis during 2-yr treatment with cyclosporine. Diabetes 38:58–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pirsch JD, Miller J, Deierhoi MH, Vincenti F, Filo RS 1997 A comparison of tacrolimus (FK506) and cyclosporine for immunosuppression after cadaveric renal transplantation. Transplantation 63:977–983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vincenti F, Larsen C, Durrbach A, Wekerle T, Nashan B, Blancho G, Lang P, Grinyo J, Halloran PF, Solez K, Hagerty D, Levy E, Zhou W, Natarajan K, Charpentier B 2005 Costimulation blockade with belatacept in renal transplantation. N Engl J Med 353:770–781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midtvedt K, Hjelmesaeth J, Hartmann A, Lund K, Paulsen D, Egeland T, Jenssen T 2004 Insulin resistance after renal transplantation: the effect of steroid dose reduction and withdrawal. J Am Soc Nephrol 15:3233–3239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui H, Khoury N, Zhao X, Balkir L, D'Amico E, Bullotta A, Nguyen ED, Gambotto A, Perfetti R 2005 Adenovirus-mediated XIAP gene transfer reverses the negative effects of immunosuppressive drugs on insulin secretion and cell viability of isolated human islets. Diabetes 54:424–433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcelli-Tourvieille S, Hubert T, Moerman E, Gmyr V, Kerr-Conte J, Nunes B, Dherbomez M, Vandewalle B, Pattou F, Vantyghem MC 2007 In vivo and in vitro effect of sirolimus on insulin secretion. Transplantation 83:532–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Talavera JC, Garcia-Ocaña A, Sipula I, Takane KK, Cozar-Castellano I, Stewart AF 2004 Hepatocyte growth factor gene therapy for pancreatic islets in diabetes: reducing the minimal islet transplant mass required in a glucocorticoid-free rat model of allogeneic portal vein islet transplantation. Endocrinology 145:467–474 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krebs M, Brunmair B, Brehm A, Artwohl M, Szendroedi J, Nowotny P, Roth E, Fürnsinn C, Promintzer M, Anderwald C, Bischof M, Roden M 2007 The mammalian target of rapamycin pathway regulates nutrient-sensitive glucose uptake in man. Diabetes 56:1600–1607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAlister VC, Gao Z, Peltekian K, Domingues J, Mahalati K, MacDonald AS 2000 Sirolimus-tacrolimus combination immunosuppression. Lancet 355:376–377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kandaswamy R, Melancon JK, Dunn T, Tan M, Casingal V, Humar A, Payne WD, Gruessner RW, Dunn DL, Najarian JS, Sutherland DE, Gillingham KJ, Matas AJ 2005 A prospective randomized trial of steroid-free maintenance regimens in kidney transplant recipients. An interim analysis. Am J Transplant 5:1529–1536 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bak MI, Grochowiecki T, Gałazka Z, Nazarewski S, Jakimowicz T, Pietrasik K, Wojtaszek M, Durlik M, Karnafel W, Szmidt J 2006 Proinsulinemia in simultaneous pancreas and kidney transplant recipients. Transplant Proc 38:280–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaquist ER, Kahn SE, Clark PM, Hales CN, Porte Jr D, Robertson RP 1996 Hyperproinsulinemia is associated with increased β cell demand after hemipancreatectomy in humans. J Clin Invest 97:455–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hostens K, Ling Z, Van Schravendijk C, Pipeleers D 1999 Prolonged exposure of human β-cells to high glucose increases their release of proinsulin during acute stimulation with glucose or arginine. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 84:1386–1390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald CG, Ryan EA, Paty BW, Senior PA, Marshall SM, Lakey JR, Shapiro AM 2004 Cross-sectional and prospective association between proinsulin secretion and graft function after clinical islet transplantation. Transplantation 78:934–937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruessner RW, Kandaswamy R, Humar A, Gruessner AC, Sutherland DE 2005 Calcineurin inhibitor- and steroid-free immunosuppression in pancreas-kidney and solitary pancreas transplantation. Transplantation 79:1184–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barth RN, Janus CA, Lillesand CA, Radke NA, Pirsch JD, Becker BN, Fernandez LA, Chin L, Becker YT, Odorico JS, D'Alessandro AM, Sollinger HW, Knechtle SJ 2006 Outcomes at 3 years of a prospective pilot study of Campath-1H and sirolimus immunosuppression for renal transplantation. Transpl Int 19:885–892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelens MA, Christiaans MH, van Heurn EL, van den Berg-Loonen EP, Peutz-Kootstra CJ, van Hooff JP 2006 High rejection rate during calcineurin inhibitor-free and early steroid withdrawal immunosuppression in renal transplantation. Transplantation 82:1221–1223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]