Abstract

In this paper we review the evidence for departure from linearity for malignant and non-malignant disease and in the light of this assess likely mechanisms, and in particular the potential role for non-targeted effects.

Excess cancer risks observed in the Japanese atomic bomb survivors and in many medically and occupationally exposed groups exposed at low or moderate doses are generally statistically compatible. For most cancer sites the dose–response in these groups is compatible with linearity over the range observed. The available data on biological mechanisms do not provide general support for the idea of a low dose threshold or hormesis. This large body of evidence does not suggest, indeed is not statistically compatible with, any very large threshold in dose for cancer, or with possible hormetic effects, and there is little evidence of the sorts of non-linearity in response implied by non-DNA-targeted effects.

There are also excess risks of various types of non-malignant disease in the Japanese atomic bomb survivors and in other groups. In particular, elevated risks of cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease and digestive disease are observed in the A-bomb data. In contrast with cancer, there is much less consistency in the patterns of risk between the various exposed groups; for example, radiation-associated respiratory and digestive diseases have not been seen in these other (non-A-bomb) groups. Cardiovascular risks have been seen in many exposed populations, particularly in medically exposed groups, but in contrast with cancer there is much less consistency in risk between studies: risks per unit dose in epidemiological studies vary over at least two orders of magnitude, possibly a result of confounding and effect modification by well known (but unobserved) risk factors. In the absence of a convincing mechanistic explanation of epidemiological evidence that is, at present, less than persuasive, a cause-and-effect interpretation of the reported statistical associations for cardiovascular disease is unreliable but cannot be excluded. Inflammatory processes are the most likely mechanism by which radiation could modify the atherosclerotic disease process. If there is to be modification by low doses of ionizing radiation of cardiovascular disease through this mechanism, a role for non-DNA-targeted effects cannot be excluded.

Keywords: Cancer, Cardiovascular disease, Dose, response, Non-DNA-targeted effects, Genomic instability, Bystander effect, Japanese atomic bomb survivors

1. Introduction

Deterministic and stochastic effects associated with high dose ionizing radiation (X-ray) exposure have been known for almost as long as ionizing radiation itself [1–3]. At lower doses radiation risks are primarily stochastic effects, in particular somatic effects (cancer) rather than the deterministic effects characteristic of higher dose exposure [4–6]. In contrast to deterministic effects, for stochastic effects scientific committees generally assume that at sufficiently low doses there is a positive linear component to the dose–response, i.e., that there is no threshold [4–6]; this does not preclude there being higher order (e.g., quadratic) powers of dose in the dose–response that may be of importance at higher doses. It is on this basis that models linear (or linear-quadratic) in dose are often used to extrapolate from the experience of the Japanese atomic bomb survivors (typically exposed at a high-dose rate to moderate doses (average 0.1 Sv)) to estimate risks from low doses and low-dose rates [4–6]. Most population based cancer risk estimates are based primarily on the Japanese atomic bomb survivor Life Span Study (LSS) cohort data [4–6]. However, evidence of excess risks comes from a large number of other studies also.

There is emerging evidence of excess risk of cardiovascular disease at low radiation doses in the Japanese atomic bomb survivor Life Span Study (LSS) cohort [7–9] and in a few other groups [10–15], although not in others [16]. Elevated risks of other non-malignant disease endpoints, in particular respiratory disease and digestive disease are observed in the A-bomb data [8], although there is little evidence for similar excess risk in other groups [17].

The classical radiobiology paradigm assumes that biological damage produced by ionizing radiation occurs when radiation interacts directly with DNA in the cell nucleus or indirectly through the action of free radicals [18]. However, there have been a number of reports of cells exposed experimentally to α-particle radiation in which more cells showed damage than were traversed by α particles (reviewed in [19,20]), i.e., a bystander effect. This is observed for a number of end points, including cell killing, micronucleus induction, and mutation induction [19,20]. The bystander effect implies that the dose–response after broad-beam irradiation could be highly concave at low doses because of saturation of the bystander effect at high doses, so that predictions of low-dose effects obtained by linear extrapolation from data for high-dose exposures would be substantial underestimates. Other so-called non-DNA-targeted effects, in particular transmissible genomic instability, adaptive response and low dose hypersensitivity also have the potential to dramatically alter the form of the dose–response. All of these have been documented in vivo and in vitro and extensively reviewed by UNSCEAR, ICRP and others [19–25].

Claims have been made for possible real (or at least “practical”) thresholds or “hormetic” (beneficial) effects of low doses of ionizing radiation [26], in part based on these non-targeted effects. As will be argued below (and elsewhere [27]), there is little epidemiological or biological evidence for these for cancer. The arguments are of three forms: (a) assessment of degree of curvature in the cancer dose–response within the Japanese atomic bomb survivors and other exposed groups (in particular departure from linear or linear-quadratic curvature), (b) consistency of risks between the Japanese and other moderate and low dose cohorts, and (c) assessment of other biological data on mechanisms. Given the highly nonlinear dose–response associated with non-DNA-targeted effects, this suggests that the role played by these effects for cancer may be modest.

For non-malignant disease the evidence is less clear-cut, and it is possible that low dose risk is zero or even negative [28]. What is known about the biology of cardiovascular disease suggests that radiation-induced inflammatory damage is a possible cause, indeed arguably the dominant one. For radiation to modify the cardiovascular disease process through this mechanism, as we argue below, a role for non-DNA-targeted effects cannot be excluded, although other mechanisms should also be considered.

Most of the information on radiation-induced risk comes from (a) the Japanese atomic bomb survivors, (b) medically exposed populations, (c) occupationally exposed groups and (d) environmentally exposed groups [6]. The limitations of these studies should be borne in mind. In particular there is potential in most studies for confounding or modification of dose–response by factors which may be correlated with radiation dose and which may affect disease risk, for example smoking, diet or socioeconomic status. In many large studies, in particular many of the occupational studies (e.g., [11,13–16]), information on such potential confounding factors is not given, although information on socioeconomic status (usually a crude industrial/non-industrial classification) is available [11,13–16]. In the higher dose radiotherapy studies, where doses received are very much higher than in the LSS, sometimes in the range at which cell-sterilisation occurs, excess cancer risks per unit dose tend to be less than in comparable subsets of the LSS [29,30]. However, as we show, cancer risks in moderate and low dose medically and occupationally exposed groups are generally consistent with those in the LSS. This is not generally the case for non-malignant disease. We examine these two broad classes of disease in turn.

2. Cancer

2.1. Evidence for departures from linear or linear-quadratic curvature in the cancer dose–response in moderate-dose exposed cohorts

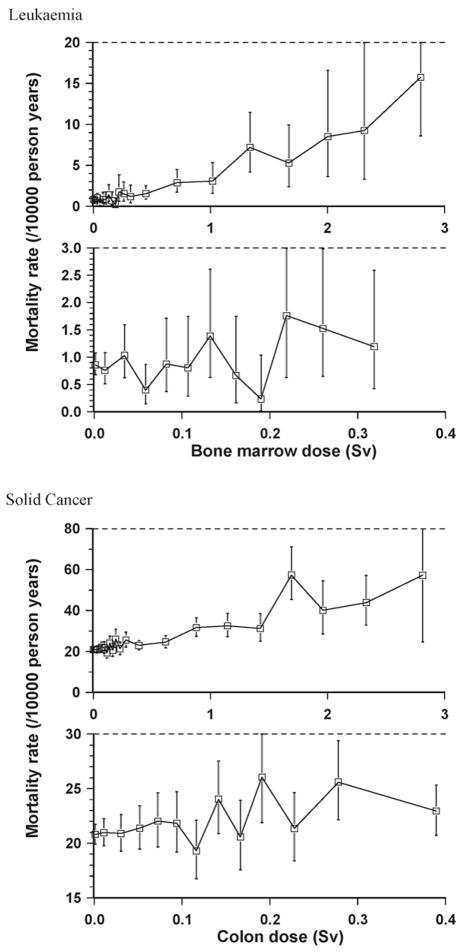

The dose–response for most cancer sites in the LSS and in other radiation-exposed cohorts is well described by a linear function of dose [6,31–35]. The major exceptional sites in this respect are leukaemia (see Fig. 1) and non-melanoma skin cancer in the LSS [31–33,35,36] and bone cancer in radium dial painters [37,38]. When all solid cancers are analysed together, there is no evidence of significant departure from a linear dose–response in the latest LSS cancer incidence data, although there are suggestions of modest upward curvature in the latest LSS mortality data [6,8,34,39] (see Fig. 1). The evidence for breast cancer, where there is reasonable power to study the risks at low doses, suggests that the data are most consistent with linearity [40]. It should be noted that as well as modifications in carcinogenic effectiveness (per unit dose) relating to the total dose delivered there are also possible variations in effectiveness as a result of dose fractionation (the process of splitting a given dose into a number of smaller doses suitably separated in time) and dose rate [18]. This is not surprising radiobiologically; by administering a given dose at progressively lower dose rates (i.e., giving the same total dose over longer periods of time), or by splitting it into many fractions, the biological system has time to repair the damage, so that the total damage induced will be less [18]. A role for inflammation in tumour promotion (if not initiation) has been demonstrated for a number of cancers [41]. The fact that induction of inflammation is radiation dose rate dependent [42] yields an alternative (non-targeted effect) mechanism that would also account for dose-rate effects for cancer. This plus the modest upward curvature exhibited in the solid cancer mortality dose–response overall [34] and for certain specific cancer sites [6,35,36], and the rather larger curvature in the leukaemia dose–response [34], as discussed above, provide some justification for using a dose and dose-rate effectiveness factor (DDREF) other than 1 when linear models are employed to extrapolate to low doses and low-dose rates. The DDREF is the factor by which one divides risks for high dose and high-dose rate exposure to obtain risks for low doses and low-dose rates. The International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) [5] recommended that a DDREF of 2 be used together with models linear in dose for all cancer sites, on the basis largely of the observations in various epidemiological datasets. The Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiation VII (BEIR VII) Committee [4] estimated what they termed an ‘LSS DDREF’ to be 1.5 (95% CI: 1.1, 2.3), on the basis of estimates of curvature from experimental animal data and from the latest LSS data on solid cancer incidence. The United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) [6] has reviewed the various values proposed for DDREF, as also the criteria used to determine the range of applicability in dose and dose rate, which suggested that a DDREF of no more than 3 be used in conjunction with linear models. For radon daughter exposure there is evidence that dose protraction results in reduction of lung cancer risk [43,44]. This may be due to saturation of initiation [45], but could also be explicable by the fact that in a multistage model when two non-adjacent stages are radiation affected then protraction of dose results in augmentation of effect, the augmentation resulting in a quadratic dose–response [46], although there is little evidence of this for this endpoint [43]. As with most data, evidence for departure from linearity in epidemiological data can be limited by lack of statistical power, and for rare cancer sites this is likely to be a particular problem. Heterogeneity within the population would result in overdispersion, and this too could limit the power to detect departures from linearity.

Fig. 1.

Dose–response (+95% CI) for leukaemia and solid cancer in the most current Japanese atomic bomb survivor mortality data (dataset analysed in Refs. [6,8,39]).

It has been customary to model the dose–response in fits to biological [18] and epidemiological data [6] by a linear-quadratic (upward curving) function of dose – and this form of dose–response is strongly indicated for leukaemia in various radiation-exposed groups [4,6,31–33,39]. Various other possible departures from a linear dose–response have been used; for example exponential cell-sterilisation adjustments to the linear-quadratic term in the dose–response have been employed in fits to biological [18] and higher dose epidemiological data [32,36,39,47–50].

Evidence for threshold effects has also been examined using the LSS data. Little and Muirhead [32,33,51] fitted linear-threshold and linear-quadratic-threshold models to the LSS incidence and mortality data (various solid cancer subtypes and leukaemia), adjusting also for measurement error. There was no evidence of threshold departures from linearity or linear-quadratic curvature in the solid cancer data by subtype or overall; when using a linear-quadratic model, for the mortality data the central estimate of threshold is <0 Sv (95% CI < 0, 0.15) and for incidence the central estimate of threshold is 0.07 Sv (95% CI < 0, 0.23) [51]. Pierce and Preston [52] also fitted linear-threshold models to the LSS solid cancer incidence data, with an extra 7 years of follow-up, to the end of 1994, and estimated the threshold as 0 Sv (95% CI < 0, 0.06); the somewhat tighter upper bound is perhaps because of the extra years of follow-up data and the use of a linear-threshold rather than a linear-quadratic-threshold model. Little and Muirhead [51] found evidence at borderline levels of statistical significance for departures from linear-quadratic curvature for leukaemia incidence, but not for mortality; when using a linear-quadratic model, for the mortality data the central estimate of threshold is 0.09 Sv (95% CI < 0, 0.29) (p = 0.16) and for incidence the central estimate of threshold is 0.11 Sv (95% CI 0.003, 0.27) (p = 0.04) [51]. As Little and Muirhead [33] document, the LSS leukaemia mortality and incidence data are fairly similar (most leukaemia cases were fatal in the 1950s and 1960s). Little and Muirhead [33,51] concluded that the most likely explanation of the difference in findings between the leukaemia incidence and mortality data is the finer disaggregation of dose groups in the publicly available version of the mortality data compared with the incidence data.

The ICRP has recently carefully reviewed the issue of possible thresholds and their effect on risk estimates [21] (but see also Ref. [53]). Their survey of the epidemiological data indicates that there are a number of groups exposed at low doses and dose rates that exhibit excess risk, compatible with extrapolations from risks observed at moderate to high doses and dose rates [21], and these are now discussed.

2.2. Direct evidence for risk in groups exposed to low and moderate doses and compatibility with risks in Japanese atomic bomb survivors

Direct epidemiological evidence exists of excess cancer risk in a number of groups exposed at low doses or low dose rates [6,21]. In particular, excess cancer risk is associated with radiation exposures of the order of a few tens of mGy from diagnostic X-ray exposure in the Oxford Survey of Childhood Cancers (OSCC) and in various other groups exposed in utero [54–56]. However, the interpretation of these in utero studies remains controversial [57,58], in particular because there is no specificity in risk—the risk for all childhood solid tumours is increased, at about 40%, by the same magnitude as that for childhood leukaemia, implying a possible bias. The ICRP [58] has carefully reviewed all these studies, in particular the OSCC, and has noted a number of methodological problems, in particular possible selection and recall biases that may operate; they noted that “although the arguments fall short of being definitive because of the combination of biological and statistical uncertainties involved, they raise a serious question of whether the great consistency in elevated [relative risks], including embryonal tumours and lymphomas, may be due to biases in the OSCC study rather than a causal association” [58]. Doll and Wakeford [59] and Wakeford and Little [60] also carefully reviewed the literature and concluded that most of the criticisms of these studies could be addressed; Doll and Wakeford [59] concluded that “there is strong evidence that low dose irradiation of the fetus in utero… causes an increased risk of cancer in childhood.”

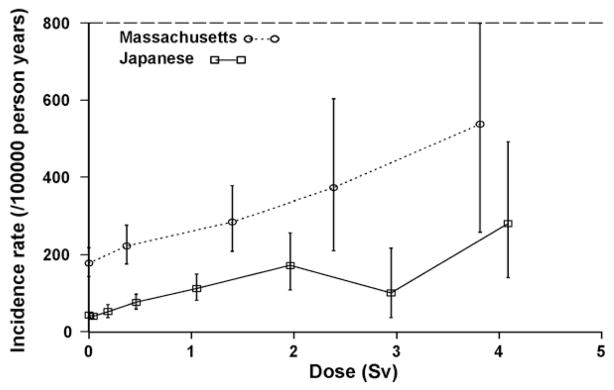

Increased breast cancer risk has been observed among young women exposed to moderately high cumulative doses (mean 0.8 Gy) from multiple thoracic fluoroscopic X-ray exposures, delivered in fractions that were, on average, of the order of 10 mGy [61–63]. A typical chest fluoroscopy given in the period 1930–1950 would last about 15 s and patients would receive 0.01–0.10 Gy [63]. These fluoroscopic exposures did not occur at low dose rates, although as the fluoroscopies would be given every 2 weeks for 3–5 years, the wide temporal separation of such fractionated low-dose exposure should, theoretically, result in a linear dose–response relationship directly applicable to the estimation of low-level effects [18,64]. Excess (absolute) breast cancer risks per unit dose in these groups are comparable to those in the LSS [40,63] (see Fig. 2). However, there is no comparable excess risk of lung cancer among fluoroscopy patients, even though lung doses were comparable to breast doses [65,66]. The difference between the breast and lung cancer findings among fluoroscopy patients suggests that there may be variation among cancer sites in terms of fractionation effects, but possible residual confounding effects of cigarette smoking cannot be ruled out nor can possible misdiagnosis of lung cancer as tuberculosis. Increased breast cancer risk has also been observed in a study of patients given multiple X-rays as part of the diagnosis of scoliosis [67].

Fig. 2.

Dose–response for breast cancer (+95% CI) in Massachusetts TB fluoroscopy vs. A-bomb (reproduced from Ref. [63]).

A pooled analysis of data from five studies of thyroid cancer following irradiation during childhood [68], including the Israeli tinea capitis patients, the youngest (age-at-exposure <15) atomic bomb survivors, two populations treated by X-ray for enlarged tonsils or lymphoid hyperplasia, and a population treated for supposedly enlarged thymus, obtained an overall excess relative risk (ERR) per Gy of 7.7 (95% CI 2.1, 28.7). The highest risk of thyroid cancer was observed among the Israeli tinea capitis patients, for whom the ERR per Gy was 32.5 (95% CI 14.0, 57.1), based on 44 cases among the exposed and 16 cases among the non-exposed, and this largely accounted for the significant inter-study heterogeneity that was observed. Although the doses to the thyroid gland in the Israeli tinea capitis study are low, averaging 90 mGy (range 40–500 mGy), they are very uncertain, and Ron et al. [68] point out that only minor dosimetric adjustment in this cohort is required to make the ERR compatible with the other four studies. No significant thyroid cancer excess was observed in a much smaller US group of patients given similar treatment (average thyroid dose 60 mGy) [69], but the difference in risk estimates between this study and the comparable Israeli study was not statistically significant [69]. Two Swedish studies of skin haemangioma patients with low dose and low-dose rate exposures from 226Ra obtained similar risk estimates to the pooled analysis of Ron et al. [68]: an ERR/Gy = 7.5 [95% CI 0.4, 18.1] based on an estimated mean thyroid dose of 120 mGy [70], and ERR/Gy = 4.9 (95% CI 1.3, 10.2) based on a mean dose of 260 mGy [71].

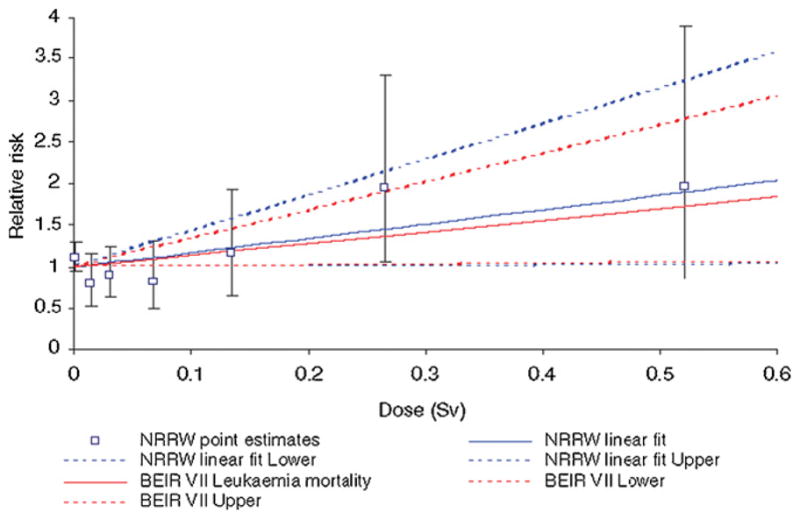

There are a number of studies of occupationally exposed persons, who generally receive low doses and low dose rates of ionizing radiation [14,72]. In all these worker studies it is important to recognise that individual doses have been accumulated in daily increments over a protracted period of many years. For example, in the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC) 15-country study [72] average cumulative doses were 19.4 mSv, and less than 5% of workers received cumulative doses exceeding 100 mSv. Risks in these studies are generally consistent with those seen in the LSS. In particular, Muirhead et al. [14] estimate that the leukaemia mortality ERR coefficient in the UK nuclear workers is 1.712 Sv−1 (90% CI 0.06, 4.29) (see Fig. 3), which is comparable with that estimated from the linear part of the leukaemia dose–response in a comparable (age-at-exposure- and follow-up-matched) part of the LSS, namely 1.4 Sv−1 (90% CI 0.1, 3.4). For mortality from all malignant neoplasms excluding leukaemia the ERR coefficient is 0.275 Sv−1(90% CI 0.02, 0.56), which is again comparable with that estimated from a linear model fitted to (age-at-exposure- and follow-up-matched) data for this endpoint in the LSS, 0.26 Sv−1(90% CI 0.15, 0.41). The IARC 15-country study [72] risk for leukaemia, an ERR of 1.93 Sv−1 (95% CI < 0, 8.47), was similar to that in an age-matched subset of the LSS, the linear coefficient (in fits of a linear-quadratic model) being 1.54 Sv−1 (95% CI −1.14, 5.33), although for solid cancers there are (statistically non-significant) indications of higher relative risks than in the LSS: an ERR of 0.97 Sv−1 (95% CI 0.14, 1.97) compared with 0.32 Sv−1 (95% CI 0.01, 0.50) in an age-matched subset of the LSS. The ratio of lung cancer risk coefficients in the LSS and the Colorado Plateau uranium miners is very close to the value suggested by the latest ICRP [73] model of lung dosimetry [44]. Precise estimation of cancer risks after low doses of radiation exposure requires very large studies with long-term follow-up [74]. As pointed out by Little et al. [27], absence of significantly elevated risks observed in some occupational studies therefore should not be taken as evidence of lack of risk. In particular, this shows that use of a “practical” threshold, as proposed by some [26], may not be wise: just because one cannot detect a risk does not mean that it is not there.

Fig. 3.

Leukaemia (+90% CI) in National Registry for Radiation Workers vs. linear part of linear-quadratic model fitted to Japanese atomic bomb survivor mortality data by BEIR VII [4] (reproduced from Ref. [14]).

Of relevance to these epidemiological studies is the study of stable chromosome exchanges in the peripheral blood lymphocytes of populations with protracted exposures. Chromosome changes play a major role in carcinogenesis and there is increasing evidence that the presence of increased frequencies of chromosome aberrations in peripheral blood lymphocytes in healthy individuals could be a surrogate for the specific changes associated with carcinogenesis and therefore indicative of risk [75–77]. Tawn et al. [78] have demonstrated a linear dose–response for chromosome translocations in workers exposed occupationally to low linear energy transfer (LET) radiation. The linear coefficient that Tawn et al. obtain, in the range 0.77 (±0.22) − 1.11 (±0.190) × 10−2 translocations Sv, is slightly lower than but not statistically inconsistent with the linear coefficient obtained in fits of a linear-quadratic model to stable chromosome aberration data in the Nagasaki survivors excluding factory workers, 2.122 (±1.203) × 10−2 translocations Sv−1, and which is also consistent with that in the Hiroshima survivors [79]. For low doses of radiation the production of a chromosome exchange generally occurs within a few hours of the initial lesions and the International Atomic Energy Agency [80] considers that when inter-fraction intervals of more than 6 h occur the exposures can be considered as isolated events with the induced aberration yields being additive. The occupational doses received by the workers in the Sellafield study were accumulated in small daily increments of <0.4 mSv. Whilst the effect of any one daily increment is too small to measure, their cumulative effect conforms to expectations based on the linear component of dose–response curves derived from in vitro experiments using acute exposures. Thus linearity must extend below 1 mSv, at least for the induction of chromosome aberrations and there is no evidence to support suggestions of novel mechanisms operating at these very low doses. Studies of US radiologic technologists with cumulative discrete exposures to low doses of diagnostic X-rays have produced similar findings [81].

2.3. Mechanisms for induction of cancer at low dose, and likely role for non-DNA-targeted effects

2.3.1. Canonical (DNA-targeted) mechanisms

For the class of deterministic effects defined by the ICRP [5], it is assumed that there is a threshold dose, below which there is no effect, and the response (probability of effect) smoothly increases above that point. Biologically it is much more likely that there is a threshold for deterministic effects than for stochastic effects; deterministic effects ensue when a sufficiently large number of cells are damaged within a certain critical time period that the body cannot replace them [82]. As outlined by Harris [83] (but see also Ref. [18]), there is compelling biological data to suggest that cancer arises from a failure of cell differentiation, and that it is largely unicellular in origin. Canonically, cancer is thought to result from mutagenic damage to a single cell, specifically to its nuclear DNA, which in principle could be caused by a single radiation track [18], although there is evidence, both in vitro and in vivo, that other targets within the cell may also be involved, i.e., non-DNA-targeted effects [19,20,25], as is discussed in more detail below. A low-LET dose of 1 mGy corresponds to about one electron track hitting a cell nucleus [18,84]. As Brenner et al. [85] point out this means that at low doses (10 mGy or less over a year) it is unlikely that temporally and spatially separate electron tracks could cooperatively produce DNA damage. Brenner et al. [85] surmise from this that in this low dose region DNA damage at a cellular level would be proportional to dose. However, non-DNA-targeted effects would somewhat alter these calculations, by increasing the effective target size.

It has been known for some time that the efficiency of cellular repair processes varies with dose and dose rate [18,84], and this may be the reason for the curvature in cancer dose–response and dose rate effects observed in epidemiological and animal data. DNA double strand breakage is thought to be the most critical lesion induced by radiation [18], although as above, there is evidence of other targets within the cell [19,20,25]. Repair of double strand breaks (DSBs) relies on a number of pathways, even the most accurate of which, homologous recombination, is prone to errors [84]; other repair pathways, e.g., non-homologous end joining, single-strand annealing, are intrinsically much more error prone [21,84]. The variation in efficacy of repair that undoubtedly occurs will affect the magnitude of unrepaired and misrepaired damage and, whereas unrepaired damage is likely to result in cell death, misrepaired damage will invariably result in mutation.

2.3.2. Non-DNA-targeted mechanisms

Low dose hypersensitivity has been shown to occur for cell killing, in vivo and in vitro [22,23] with suggestions that this is the result of a failure to activate repair processes, and will very likely effectively remove any potentially genetically altered cells. However, chromosome rearrangements and gene mutations, both of which arise as a result of misrepair, have been shown to be inducible in vitro at doses of the order of 0.01 Gy with a linear no-threshold dose–response relationship [84] and, as discussed above, chromosome translocations have been reported in blood lymphocytes from occupationally exposed workers. Adaptive response has been documented in vivo and in vitro and has been thoroughly reviewed by ICRP and the UNSCEAR [21,24,25], who observed that generally, the protective effect of the conditioning dose appears to last only for a few hours and the ability to induce an adaptive response differs between individuals, with some failing to respond at all [21,24,25]. Also, generally the excess risk after the challenge dose is reduced by the previous adapting dose, but is still generally increased [21,24,25], so that this mechanism would not account for possible threshold or hormetic effect at low doses. Observations of responses in neighbouring cells which have not been directly hit have been taken to imply that at low doses these adverse effects would occur at very much greater rates than implied by linear extrapolation [86]. On the other hand, it has been suggested that such bystander effects could be part of a sensitive response system and thus be protective [87]. Bystander effects have been observed largely in vitro [19,20,25], although one recent study provides evidence for bystander induction of cancer in a Ptch1+/− mouse model of brain cancer [88] after very high dose (3, 8.3 Gy) partial-body radiation exposure. The relevance of this work to low-dose risk in humans is unclear, but suggests, as with some others [19,20,25], that bystander effects can act to increase rather than decrease risk. There is little evidence of a bystander effect in epidemiological studies of cancer, a view supported by studies of lung cancer following exposure to the alpha-emitting radionuclide radon and its decay products [89]. The dose–response shows no substantial departure from linearity over a wide dose range from underground miners to homes, and suggests at most a factor of 2–3 augmentation of low dose lung cancer risk compared with that resulting from high dose extrapolation [89] (see Fig. 4). Although there appears to be substantial evidence of radiation inducing persistent genomic instability in haemopoietic cells in vitro and some limited support for the effect to be transmissible in vivo, to date there has been little evidence produced to indicate in vivo induction and transmission [20]. Suggestions that radiation-induced genomic instability has played a role in the induction of leukaemia in the Japanese atomic bomb survivors [90,91] have been criticised following reanalysis of the data [92,93]. Follow-up studies of chromosome aberration frequencies in individuals with known exposures to radiation do not show evidence of a continuing expression of genomic instability [94–98].

Fig. 4.

Lung cancer (+95% CI) in various residential radon studies, and extrapolations from underground miner data (reproduced from Ref. [89]).

3. Non-malignant disease

It has been known for a long time that after high-dose radiotherapy damage to the heart and coronary arteries can occur [10,28,99], and the mechanisms for this are relatively well understood, arising as a response to cell killing and tissue damage [28,99]. There is emerging evidence of excess risk of circulatory disease at low radiation doses in the Japanese atomic bomb survivor Life Span Study (LSS) cohort [7–9]. There are also excess risks of various other types of non-malignant disease in the Japanese atomic bomb survivors, in particular respiratory disease and digestive disease [8]. Indeed, as shown in Table 1, risks are elevated to much the same degree, even when they are not statistically significant, for a number of other non-malignant disease endpoints, suggestive of bias.

Table 1.

Non-cancer mortality excess relative risk per Sv in LSS (taken from Ref. [8]).

| Endpoint | ERR/Sv (90% CI) |

|---|---|

| Heart disease | 0.17 (0.08, 0.26) |

| Stroke | 0.12 (0.02, 0.22) |

| Respiratory disease | 0.18 (0.06, 0.32) |

| Pneumonia | 0.16 (0.00, 0.32) |

| Digestive disease | 0.15 (0.00, 0.32) |

| Cirrhosis | 0.19 (−0.05, 0.50) |

| Infectious disease | −0.02 (<−0.20, 0.25) |

| Tuberculosis | −0.01 (<−0.20, 0.40) |

| Other diseases | 0.08 (−0.04, 0.23) |

| Urinary diseases | 0.25 (−0.01, 0.60) |

| All non-cancer | 0.14 (0.08, 0.20) |

In contrast to cancer, the shape of the dose–response for non-malignant disease endpoints is much less well defined [8,100]. For example, if a power of dose model is fitted, the best estimate of the power of dose for heart disease is 1.12 (95% CI 0.17, 3.34), while for stroke the best estimate is 1.54 (95% CI 0.02, >10.00) [100].

In general risks of non-cancer diseases other than circulatory disease are not observed in groups other than the LSS [17], and for that reason we concentrate on circulatory disease from now on, and in particular on what is observed at low and moderate doses (<5 Gy).

3.1. Comparison of circulatory disease risks in LSS with other moderate and low dose studies

Various recent papers systematically reviewed the epidemiological evidence for associations between low and moderate doses (<5 Gy) of ionizing radiation exposure and late occurring cardiovascular disease [28,101]. Risks per unit dose in epidemiological studies varied over at least two orders of magnitude, possibly a result of confounding factors (of which there are at least eight major independent ones: male sex, family history of heart disease, cigarette smoking, diabetes, high blood pressure, obesity, increased total and low density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and decreased high density lipoprotein cholesterol plasma levels [28]). These papers also reviewed possible biological mechanisms for such low dose effects and indicated that the most likely causative effect of radiation is damage to endothelial cells and subsequent induction of an inflammatory response, although it seems unlikely, assuming canonical DNA-damage mechanisms, that this would extend to low dose and low-dose rate exposure [28,101]. However, a role for somatic mutation has been proposed [102–104] that would indicate a stochastic effect. In the absence of a convincing mechanistic explanation of epidemiological evidence that is, at present, less than persuasive, the authors concluded that a cause-and-effect interpretation of the reported statistical associations could not be reliably inferred, although neither could it be reliably excluded [28,101].

In comparison of the lower dose studies considered by Little et al. [28,101] a distinction should be made between the acute doses received from radiotherapy and the atomic bombs and the chronic small incremental doses received occupationally. As summarised elsewhere [28,99] it is well recognised that the effect at high acute doses is likely to be deterministic and due to a response to cell killing and tissue damage. Therefore studies of radiotherapy patients, even at doses down to 0.5 Gy, and that are reviewed elsewhere [99], will not address the issue of mechanisms of any potential effect of small incremental doses, since even at 0.5 Gy there will be quite a lot of cell killing. Low dose chronic exposure will not have the same effect. Even if the same total number of cells are killed, the time span over which this occurs is typically tens of years and their loss is unlikely to be detrimental and will probably be accommodated within the normal patterns of cell turnover and renewal.

Various meta-analysis of the available low dose data have recently been published [28,101,105]. Little et al. [101] summarised aggregate ERR for various groups of studies, summarised in Table 2. The results of Table 2 suggest that the aggregate estimate of ERR from all low dose studies is 0.08 Sv−1 (95% CI 0.05, 0.11). There is significant heterogeneity (p < 0.001) in risk between studies, among all groups considered in Table 2. Further analysis in which each study is removed in turn, reported in Table 3, does not substantially alter the aggregate risk estimate, which increased to at most 0.11 Sv−1 (95% CI 0.07, 0.14) (after exclusion of the Japanese atomic bomb survivors [8,9]), although removing the Mayak worker study [15] results in a substantial decrease in the best estimate of ERR, to 0.04 Sv−1 (95% CI 0.01, 0.07), although this remains statistically significant. The analysis of Table 4 suggests that the risk of radiation-induced heart disease is much lower, 0.07 Sv−1 (95% CI 0.04, 0.11), than that for stroke, 0.27 Sv−1 (95% CI 0.20, 0.34). The morbidity risk of circulatory disease appears to be somewhat higher, 0.10 Sv−1 (0.07, 0.13) than that for mortality, 0.03 Sv−1 (−0.02, 0.08). However, even within these endpoints there is still statistically significant heterogeneity (p < 0.001). One possible source of heterogeneity is interaction with other risk factors, which are generally not controlled for—the only studies which incorporate such adjustment (for smoking and drinking) are the Japanese atomic bomb survivor morbidity study [9] and the Mayak worker study [15]. [Note added in proof: the latest analysis of the Japanese atomic bomb survivor mortality data also incorporates adjustment for smoking, alcohol intake, education, occupation, obesity and diabetes, adjustment for which makes little difference to (the highly statistically significant excess) circulatory disease risks [151].] Therefore, the aggregate low dose epidemiological data are supportive of a positive trend of cardiovascular disease with dose, although this is a fragile finding.

Table 2.

Aggregate excess relative risks (per Sv) of circulatory disease in published low dose (<5 Sv) epidemiological datasets with estimated average radiation dose to the heart and for which quantitative risk assessment is possible (using as endpoint mortality from circulatory disease unless otherwise indicated) (reproduced from Ref. [101]).

| Description | Studies included | ERR Sv−1 (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| All occupational and environmental studies including McGeoghegan et al. [13] but excluding Muirhead et al. [14] | Talbott et al. [147] a, Ivanov et al. [12], Kreuzer et al. [148], Vrijheid et al. [16], McGeoghegan et al. [13] b, Azizova and Muirhead [15] c | 0.19 (0.14, 0.24)## |

| All occupational and environmental studies excluding McGeoghegan et al. [13] but including Muirhead et al. [14] | Talbott et al. [147] a, Ivanov et al. [12], Kreuzer et al. [148], Vrijheid et al. [16], Azizova and Muirhead [15] c, Muirhead et al. [14] | 0.19 (0.14, 0.23)## |

| Atomic bomb survivor and medical irradiation studies | Darby et al. [149] d, Davis et al. [65], Preston et al. [8] e, Yamada et al. [9] f, Carr et al. [150] g | 0.03 (0.00, 0.07)# |

| All studies including McGeoghegan et al. [13] but excluding Muirhead et al. [14] | Darby et al. [149] d, Davis et al. [65], Preston et al. [8] e, Talbott et al. [147] a, Yamada et al. [9] f, Carr et al. [150] g, Ivanov et al. [12], Kreuzer et al. [148], Vrijheid et al. [16], McGeoghegan et al. [13] b, Azizova and Muirhead [15] c | 0.08 (0.06, 0.11)## |

| All studies excluding McGeoghegan et al. [13] but including Muirhead et al. [14] | Darby et al. [149] d, Davis et al. [65], Preston et al. [8] e, Talbott et al. [147] a, Yamada et al. [9] f, Carr et al. [150] g, Ivanov et al. [12], Kreuzer et al. [148], Vrijheid et al. [16], Azizova and Muirhead [15] c, Muirhead et al. [14] | 0.08 (0.05, 0.11)## |

Analysis based on heart disease (males and females separately).

Analysis including underlying and contributory causes of death.

Analysis based on ischaemic heart disease and cerobrovascular disease morbidity, using external gamma dose.

Analysis based on stroke and other circulatory disease (separately).

Analysis based on heart disease and stroke (separately).

Analysis based on morbidity from hypertension, hypertensive heart disease, ischaemic heart disease and stroke (separately).

Analysis based on coronary heart disease and other heart disease, excluding highest dose group (3.1–7.6 Gy) (separately).

p-value for heterogeneity p < 0.01.

p-value for heterogeneity p < 0.00000001.

Table 3.

Sensitivity of combined circulatory disease risk estimates to study exclusion (excess relative risk (ERR)/Sv +95% CI) (all assuming as baseline inclusion of Muirhead et al. [14] and exclusion of McGeoghegan et al. [13] (as per bottom row of Table 2 and contribution to heterogeneity χ2 statistic (+degrees of freedom (df)) (reproduced from Ref. [101]).

| Studies excluded | ERR/Sv (95% CI) | χ2 statistic (df) |

|---|---|---|

| A-bomb [8,9] | 0.11 (0.07, 0.14)## | 8.64 (6) |

| US pepticulcer [150] | 0.08 (0.06, 0.11)## | 2.14 (2) |

| UK ankylosing spondylitis [149] | 0.09 (0.06, 0.11)## | 5.99 (2) |

| Massachusetts TB [65] | 0.10 (0.07, 0.13)## | 15.82 (1) |

| IARC 15 country workers [16] | 0.08 (0.05, 0.11)## | 0.00 (1) |

| UK 3rd NRRW analysis [14] | 0.08 (0.05, 0.11)## | 1.32 (1) |

| German uranium miners [148] | 0.08 (0.06, 0.11)## | 4.67 (1) |

| Chernobyl recovery workers [12] | 0.08 (0.05, 0.11)## | 0.84 (1) |

| Mayak workers [15] | 0.04 (0.01, 0.07)# | 53.73 (2) |

| Three Mile Island [147] | 0.08 (0.05, 0.11)## | 11.62 (2) |

| None (All studies) | 0.08 (0.05, 0.11)## | 104.76 (18) |

p-value for heterogeneity p < 0.001.

p-value for heterogeneity p < 0.00000001.

Table 4.

Aggregate excess relative risks (per Sv) of circulatory disease by endpoint (reproduced from Ref. [101]).

| Endpoint | Studies included | ERR Sv−1 (95% CI) | Heterogeneity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Heart | Darby et al. [149] a, Preston et al. [8] b, Talbott et al. [147] b, Yamada et al. [9] c, Carr et al. [150] d, Ivanov et al. [12] e, Kreuzer et al. [148] b, Vrijheid et al. [16] a, Azizova and Muirhead [15] f | 0.07 (0.04, 0.11) | p = 0.00085 |

| Stroke | Darby et al. [149] g, Preston et al. [8] g, Yamada et al. [9] h, Ivanov et al. [12] h, Kreuzer et al. [148] g, Vrijheid et al. [16] g, Azizova and Muirhead [15] h, Muirhead et al. [14] g | 0.27 (0.20, 0.34) | p = 0.00004 |

| Morbidity | Yamada et al. [9] c,h,i, Ivanov et al. [12] j, Azizova and Muirhead [15] f,h | 0.10 (0.07, 0.13) | p < 10−10 |

| Mortality | Darby et al. [149] a,g, Davis et al. [65] k, Preston et al. [8] b,g, Talbott et al. [147] b, Carr et al. [150] d, Kreuzer et al. [148] k, Vrijheid et al. [16] k, Muirhead et al. [14] k | 0.03 (−0.02, 0.08) | p = 0.00003 |

| Total | Darby et al. [149] a,g, Davis et al. [65] k, Preston et al. [8] b,g, Talbott et al. [147] b, Yamada et al. [9] c,h,i, Carr et al. [150] d, Ivanov et al. [12] j, Kreuzer et al. [148] k, Vrijheid et al. [16] k, Azizova and Muirhead [15] f,h, Muirhead et al. [14] k | 0.08 (0.05, 0.11) | p < 10−13 |

Analysis based on all circulatory disease mortality apart from stroke.

Analysis based on all heart disease mortality.

Analysis based on morbidity from hypertensive heart disease, ischaemic heart disease.

Analysis based on coronary heart disease and other heart disease mortality, excluding highest dose group (3.1–7.6 Gy).

Analysis based on mortality from hypertension, ischaemic heart disease and other heart disease.

Analysis based on morbidity from ischaemic heart disease.

Analysis based on stroke mortality.

Analysis based on stroke morbidity.

Analysis based on hypertension morbidity.

Analysis based on all circulatory disease morbidity.

Analysis based on all circulatory disease mortality.

One complication in comparison of studies is the variable, but generally quite lengthy latency of circulatory disease. If it really were the case that there was a latency of 20 or more years, then at least part of the dose that would be accrued in occupational studies (which frequently use latencies of 10 years (e.g., as in Refs. [14,16])) would be wasted, implying that risk estimates for these studies would be biased downwards. Another complication is the choice of risk transfer model. Implicitly the assumption being made in use of the excess relative risk model in Tables 2–4 is that excess relative risk (per Sv) is invariant between populations. This might well not be the case, although the data are as yet insufficient to decide whether relative or absolute risk, or some hybrid mixture is best. The Japanese population has generally much lower rates of cardiovascular disease than most European populations [106], presumably a result of various exogenous factor such as diet, so that transfers from the Japanese atomic bomb survivor population to a western population are likely to be particularly sensitive to choice of model.

3.2. Mechanisms of induction of circulatory disease at low dose and role for non-DNA-targeted effects

Inflammation is believed to participate in virtually all stages of atherosclerotic disease including its inception. Epidemiological evidence for the role of inflammation in causing cardiovascular disease has come from findings that elevated levels of systemic inflammation, reflected in the increased levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokine interleukin 6 (IL-6), C-reactive protein (CRP), and a variety of cell adhesion molecules such as intercellular cell adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1), vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 (VCAM-1) and endothelial leukocyte adhesion molecule 1 (ELAM-1; E-selectin), are associated with elevated risk of cardiovascular disease in a number of prospectively examined cohorts [107–111]. Whilst the inflammatory process is recognised as an integral part of the atherosclerotic process [112] it does not explain the observation that the proliferation of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMC) during atherosclerotic plaque development is monoclonal [113,114]. Support for the hypothesis of a monoclonal origin for atherosclerosis and hence an affinity with cancer development comes from studies showing changes in expression of proto-oncogenes and tumour suppressor genes, increases in frequencies of chromosome aberrations and other markers of DNA damage in atherosclerotic lesions [115]. In addition, DNA damage, mitochondrial mutations and chromosome aberrations have been observed at increased frequencies in patients with cardiac disease, indicating a general increase in somatic mutation [102–104,116,117]. However, chronic inflammation is often associated with increased formation of reactive oxygen species [118] and it has recently been suggested that it is these, rather than the direct action of exogenous agents, that may contribute to DNA damage in atherosclerosis [116].

Clonality suggests that plaque VSMCs must have undergone multiple rounds of division, and telomere loss studies argue that this is between 7 and 13 cumulative population doublings [119]. These observations raised the possibility that spontaneous plaques (or at least their fibrous caps) arise from a subset of VSMCs that have a proliferative/survival advantage over the rest of the medial cells. This could either be a dominant transforming mutation in a single cell akin to tumorigenesis, or a more subtle mutation that alters a signalling pathway for cell division/growth arrest. Indeed, McCaffrey et al. found mutations in a microsatellite sequence in the Type II TGF-β1 receptor in plaque-derived cells, leading to a premature truncation that would cause loss of normal growth inhibition by TGF-β1 [120]. Although such mutations could indicate a mechanism by which irradiation-induced cell transformation might promote atherosclerosis, other studies have not supported these findings, particularly in regard to TGF-β1 microsatellite instability [121,122]. Furthermore, clonality itself is not synonymous with transformation of a single cell, and subsequent studies have shown that large patches in the normal vessel media are monoclonal [114,123]. Thus, clonality is more likely to be explained by the presence of developmental clones in the normal vessel wall, rather than a mutation. Finally, in contrast to tumours, plaque VSMCs shows poor proliferation, enhanced apoptosis, and early senescence [114,124]. These features would not confer a proliferative or survival advantage to plaque VSMCs. Furthermore, plaque VSMC proliferation is now seen to be beneficial in atherosclerosis [125], so that the pathological consequences of a mutation promoting VSMC proliferation are unclear.

A variety of in vitro studies suggest that high doses (>1 Gy) up-regulate adhesion of leukocytes to the vascular endothelium via up-regulation of adhesion molecules such as ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and the E-selectins [126–132]. In contrast, doses in the range 0.1–1.0 Gy are associated with reduced expression in vitro of adhesion molecules such as E-selectin [133,134], although some pro-inflammatory cytokines, e.g., TGF-β and IL-6, are up-regulated [134]. One mechanism influencing the response to radiation at different doses may be the nitric oxide (NO) pathway in stimulated macrophages, since NO is known to play a central role in inflammation. When macrophages were stimulated with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and interferon-gamma (INF-γ), NO production was suppressed at X-ray doses up to 1.25 Gy, but returned to normal and increased at higher doses [135]. Generally, experimental in vivo studies confirm that acute doses of around 2 Gy and above are associated with increased expression of a variety of cell adhesion molecules in endothelial tissue [99,136]. As observed in vitro, acute doses in the range 0.1–1 Gy can result in a down-regulation in vivo of the adhesion of leukocytes to EC and thus have an anti-inflammatory effect [137]. Hildebrandt et al. [135] extended their in vitro work by examining radiation effects on the NO pathway in vivo using the murine (BALB/C) chronic granulomatous air pouch system and were able to confirm that low dose irradiation modulates the production of NO.

Elevated levels of the pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-6, CRP, TNF-α and INF-γ, but also increased levels of the (generally) anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10, have been observed in the Japanese atomic bomb survivors [138,139]. There was also dose-related elevation in erythrocyte sedimentation rate and in levels of IgG, IgA and total immunoglobulins in this cohort, all markers of systemic inflammation [139]. Given the possible role of infections in cardiovascular disease [140,141], it is of interest that certain T cell and B cell population numbers are known to vary with radiation dose among the Japanese atomic bomb survivors [142]. The atomic bomb survivors also demonstrate dose-dependent decreases in levels of CD4+ helper T cells [138]; decreased levels of helper T cells have also been found in blood samples from Japanese atomic bomb survivors with myocardial infarction [143].

The up-regulation of a range of cell-adhesion molecules and the observation of cytokine markers of the inflammatory response in the atomic bomb survivors reflect the action of acute radiation doses generally of >0.5 Gy. The presence of such markers may be indicative of radiation-induced killing of EC. However, it is not clear what responses would be induced by lower doses and lower dose rates. When considering the role of the inflammatory response in the aetiology of radiation-induced cardiovascular disease it is, therefore, also necessary to distinguish between acute and chronic exposures. Occupational doses will be received in daily increments of, in the most part, less than 0.5 mSv. Thus the killing of one or a few cells in a system which is continually undergoing regeneration is unlikely to be significant and may well not induce the types of response discussed above, although in more isolated cell populations (e.g., some in the arterial wall) this may not apply. Of relevance here is a study of workers employed at the Sellafield nuclear facility which examined a group with cumulative exposures >0.2 Sv (mean 0.33 Sv) and an otherwise similar group with exposure <0.028 Sv (mean 0.014 Sv) and found no differences in levels of CD4+, CD8+ and CD3+/HLA-DR+ cells or in the CD4+:CD8+ ratio, indicating that such fractionated exposures were not affecting these markers of immune response [144].

As discussed above, while not absolutely ruled out, somatic mutational mechanisms are unlikely to play a role in the aetiology of cardiovascular disease. Whether or not inflammation plays a role in the radiation induction of atherosclerosis, it is likely to be a major co-contributor to the development of atherosclerotic lesions [145]. If inflammation is arguably the most likely cause of radiation-induced atherosclerotic disease, the major question is how low doses and low-dose rates of radiation, in particular a single electron track, can initiate an inflammatory cascade. At sub mGy doses of low-LET radiation cells that are hit by electron tracks will be spatially and temporally isolated—for example a 0.1 mGy dose will only result in one cell in 10 being hit [18]. Without non-DNA-targeted effects to in some way enlarge the effective target size, that such an event could initiate an ongoing inflammatory reaction is improbable. As such, if radiation can modify (whether positively or negatively) the atherosclerotic disease process, it is possible that non-DNA-targeted effects are implicated, although other mechanisms should also be considered. A recently developed mathematical model of the cardiovascular system proposed a novel mechanism based on radiation-induced monocyte killing in the intima and resultant increase in monocyte chemo-attractant protein 1 (MCP-1) that binds to them [146]. As well as predicting radiation risks consistent with what is seen in nuclear workers, the changes in MCP-1 with dietary cholesterol predicted by the model are also consistent with experimental and epidemiologic data [146]. This novel biological mechanism has yet to be experimentally tested, and further research is needed.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful for the detailed comments of the two referees. This work was funded partially by the European Commission under contract FP6-036465 (NOTE). The Mayak worker analysis by Drs Azizova and Muirhead was conducted with support from the European Commission’s Euratom Nuclear Fission and Radiation Protection Programme as part of the SOUL project; more details of this analysis can be found in separate papers by the study investigators.

Footnotes

Paper presented as an invited lecture at the NOTE “Conceptualisation of New Paradigm workshop”, Galway, Ireland, 13–14 September 2008.

Conflicts of interest

None.

References

- 1.Stevens LG. Injurious effects on the skin. Br Med J. 1896;1:998. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilchrist TC. A case of dermatitis due to the X-rays. Bull Johns Hopkins Hosp. 1897;8(71):17–22. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frieben A. Demonstration eines Cancroids des rechten Handrückens, das sich nach langdauernder Einwirkung von Röntgenstrahlen bei einem 33 jährigen Mann entwickelt hatte. Fortschr Röntgenstr. 1902;6:106. [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. National Academy of Sciences. Health Risks from Exposure to Low Levels of Ionizing Radiation. BEIR VII Phase 2. The National Academies Press; Washington, DC: 2006. National Research Council Committee to assess health risks from exposure to low levels of ionizing radiation. [Google Scholar]

- 5.International Commission on Radiological Protection, ICRP Publication 103 ICRP Publication 103. Annals ICRP. 2–4. Vol. 37. Pergamon; Oxford: 2007. The 2007 recommendations of the International Commission on Radiological Protection; pp. 1–332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation, UNSCEAR 2006 Report. Annex A. Epidemiological studies of radiation and cancer. United Nations; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong FL, Yamada M, Sasaki H, Kodama K, Akiba S, Shimaoka K, Hosoda Y. Noncancer disease incidence in the atomic bomb survivors: 1958–1986. Radiat Res. 1993;135:418–430. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Preston DL, Shimizu Y, Pierce DA, Suyama A, Mabuchi K. Studies of mortality of atomic bomb survivors. Report 13: solid cancer and noncancer disease mortality: 1950–1997. Radiat Res. 2003;160:381–407. doi: 10.1667/rr3049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamada M, Wong FL, Fujiwara S, Akahoshi M, Suzuki G. Noncancer disease incidence in atomic bomb survivors, 1958–1998. Radiat Res. 2004;161:622–632. doi: 10.1667/rr3183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McGale P, Darby SC. Low doses of ionizing radiation and circulatory diseases: a systematic review of the published epidemiological evidence. Radiat Res. 2005;163:247–257. 711. doi: 10.1667/rr3314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Howe GR, Zablotska LB, Fix JJ, Egel J, Buchanan J. Analysis of the mortality experience amongst U.S. nuclear power industry workers after chronic low-dose exposure to ionizing radiation. Radiat Res. 2004;162:517–526. doi: 10.1667/rr3258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ivanov VK, Maksioutov MA, Chekin SY, Petrov AV, Biryukov AP, Kruglova ZG, Matyash VA, Tsyb AF, Manton KG, Kravchenko JS. The risk of radiation-induced cerebrovascular disease in Chernobyl emergency workers. Health Phys. 2006;90:199–207. doi: 10.1097/01.HP.0000175835.31663.ea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGeoghegan D, Binks K, Gillies M, Jones S, Whaley S. The non-cancer mortality experience of male workers at British Nuclear Fuels plc, 1946–2005. Int J Epidemiol. 2008;37:506–518. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Muirhead CR, O’Hagan JA, Haylock RGE, Phillipson MA, Willcock T, Berridge GLC, Zhang W. Mortality and cancer incidence following occupational radiation exposure: third analysis of the National Registry for Radiation Workers. Br J Cancer. 2009;100:206–212. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Azizova TV, Muirhead CR. Epidemiological evidence for circulatory diseases—occupational exposure. Proceedings of the EU Scientific Seminar “Emerging evidence for radiation induced circulatory diseases”; Luxembourg. 25 November 2008; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vrijheid M, Cardis E, Ashmore P, Auvinen A, Bae J-M, Engels H, Gilbert E, Gulis G, Habib RR, Howe G, Kurtinaitis J, Malker H, Muirhead CR, Richardson DB, Rodriguez-Artalejo F, Rogel A, Schubauer-Berrigan M, Tardy M, Telle-Lamberton M, Usel M, Veress K. Mortality from diseases other than cancer following low doses of ionizing radiation: results from the 15-Country Study of nuclear industry workers. Int J Epidemiol. 2007;36:1126–1135. doi: 10.1093/ije/dym138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) UNSCEAR 2006 Report Annex B. Epidemiological evaluation of cardiovascular disease and other non-cancer diseases following radiation exposure. United Nations; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 18.United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR), Sources and effects of ionizing radiation. UNSCEAR 1993 Report to the General Assembly, with scientific annexes. United Nations; New York: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Morgan WF. Non-targeted and delayed effects of exposure to ionizing radiation. I. Radiation-induced genomic instability and bystander effects in vitro. Radiat Res. 2003;159:567–580. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2003)159[0567:nadeoe]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morgan WF. Non-targeted and delayed effects of exposure to ionizing radiation. II. Radiation-induced genomic instability and bystander effects in vivo, clastogenic factors and transgenerational effects. Radiat Res. 2003;159:581–596. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2003)159[0581:nadeoe]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Annals ICRP. 4. Vol. 35. Pergamon; Oxford: 2006. International Commission on Radiological Protection, Low-dose extrapolation of radiation related cancer risk; pp. 1–141. ICRP Publication 99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Joiner MC, Marples B, Lambin P, Short SC, Turesson I. Low-dose hypersensitivity: current status and possible mechanisms. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2001;49:379–389. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(00)01471-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Joiner MC, Johns H. Renal damage in the mouse: the response to very small doses per fraction. Radiat Res. 1988;114:385–398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) UNSCEAR 1994 Report to the General Assembly with Scientific Annexes. United Nations; New York: 1994. Sources and Effects of Ionizing Radiation. [Google Scholar]

- 25.United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) UNSCEAR 2006 Report Annex C. Non-targeted and Delayed Effects of Exposure to Ionizing Radiation. United Nations; New York: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tubiana M, Kaminski J, Yang C, Feinendegen L. The linear no-threshold relationship is inconsistent with radiation biologic and experimental data (editorial) Radiology. 2009;251:13–22. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2511080671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Little MP, Wakeford R, Tawn EJ, Bouffler SD, Berrington de Gonzalez A. Risks associated with low doses and low dose-rates of ionizing radiation: why linearity may be (almost) the best we can do (editorial) Radiology. 2009;251:6–12. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2511081686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Little MP, Tawn EJ, Tzoulaki I, Wakeford R, Hildebrandt G, Paris F, Tapio S, Elliott P. A systematic review of epidemiological associations between low and moderate doses of ionizing radiation and late cardiovascular effects, and their possible mechanisms. Radiat Res. 2008;169:99–109. doi: 10.1667/RR1070.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Little MP. Comparison of the risks of cancer incidence and mortality following radiation therapy for benign and malignant disease with the cancer risks observed in the Japanese A-bomb survivors. Int J Radiat Biol. 2001;77:431–464. 745–760. doi: 10.1080/09553000010022634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Little MP. Cancer after exposure to radiation in the course of treatment for benign and malignant disease. Lancet Oncol. 2001;2:212–220. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(00)00291-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pierce DA, Vaeth M. The shape of the cancer mortality dose–response curve for the A-bomb survivors. Radiat Res. 1991;126:36–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Little MP, Muirhead CR. Evidence for curvilinearity in the cancer incidence dose–response in the Japanese atomic bomb survivors. Int J Radiat Biol. 1996;70:83–94. doi: 10.1080/095530096145364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Little MP, Muirhead CR. Curvature in the cancer mortality dose–response in Japanese atomic bomb survivors: absence of evidence of threshold. Int J Radiat Biol. 1998;74:471–480. doi: 10.1080/095530098141348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Preston DL, Pierce DA, Shimizu Y, Cullings HM, Fujita S, Funamoto S, Kodama K. Effect of recent changes in atomic bomb survivor dosimetry on cancer mortality risk estimates. Radiat Res. 2004;162:377–389. doi: 10.1667/rr3232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Preston DL, Ron E, Tokuoka S, Funamoto S, Nishi N, Soda M, Mabuchi K, Kodama K. Solid cancer incidence in atomic bomb survivors: 1958–1998. Radiat Res. 2007;168:1–64. doi: 10.1667/RR0763.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Little MP, Charles MW. The risk of non-melanoma skin cancer incidence in the Japanese atomic bomb survivors. Int J Radiat Biol. 1997;71:589–602. doi: 10.1080/095530097143923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rowland RE, Stehney AF, Lucas HF., Jr Dose–response relationships for female radium dial workers. Radiat Res. 1978;76:368–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thomas RG. The US radium luminisers: a case for a policy of ‘below regulatory concern’. J Radiol Prot. 1994;14:141–153. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Little MP, Hoel DG, Molitor J, Boice JD, Jr, Wakeford R, Muirhead CR. New models for evaluation of radiation-induced lifetime cancer risk and its uncertainty employed in the UNSCEAR 2006 report. Radiat Res. 2008;169:660–676. doi: 10.1667/RR1091.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Preston DL, Mattsson A, Holmberg E, Shore R, Hildreth NG, Boice JD., Jr Radiation effects on breast cancer risk: a pooled analysis of eight cohorts. Radiat Res. 2002;158:220–235. 158, 666. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2002)158[0220:reobcr]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature. 2002;420:860–867. doi: 10.1038/nature01322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mollà M, Panés J, Casadevall M, Salas A, Conill C, Biete A, Anderson DC, Granger DN, Piqué JM. Influence of dose-rate on inflammatory damage and adhesion molecule expression after abdominal radiation in the rat. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;45:1011–1018. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(99)00286-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.U.S. National Academy of Sciences, National Research Council, Committee on Health Risks of Exposure to Radon (BEIR VI) Health Effects of Exposure to Radon. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Little MP. Comparisons of lung tumour mortality risk in the Japanese A-bomb survivors and in the Colorado Plateau uranium miners: support for the ICRP lung model. Int J Radiat Biol. 2002;78:145–163. doi: 10.1080/09553000110095714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brenner DJ, Hall EJ. The inverse dose-rate effect for oncogenic transformation by neutrons and charged particles: a plausible interpretation consistent with published data. Int J Radiat Biol. 1990;58:745–758. doi: 10.1080/09553009014552131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Little MP, Hawkins MM, Charles MW, Hildreth NG. Fitting the Armitage-Doll model to radiation-exposed cohorts and implications for population cancer risks. Radiat Res. 1992;132:207–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boice JD, Jr, Blettner M, Kleinerman RA, Stovall M, Moloney WC, Engholm G, Austin DF, Bosch A, Cookfair DL, Krementz ET, et al. Radiation dose and leukemia risk in patients treated for cancer of the cervix. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1987;79:1295–1311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thomas DC, Blettner M, Day NE. Use of external rates in nested case-control studies with application to the International Radiation Study of Cervical Cancer patients. Biometrics. 1992;48:781–794. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weiss HA, Darby SC, Fearn T, Doll R. Leukemia mortality after X-ray treatment for ankylosing spondylitis. Radiat Res. 1995;142:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Little MP, Weiss HA, Boice JD, Jr, Darby SC, Day NE, Muirhead CR. Risks of leukemia in Japanese atomic bomb survivors, in women treated for cervical cancer, and in patients treated for ankylosing spondylitis. Radiat Res. 1999;152:280–292. 153, 243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Little MP, Muirhead CR. Absence of evidence for threshold departures from linear-quadratic curvature in the Japanese A-bomb cancer incidence and mortality data. Int J Low Radiat. 2004;1:242–255. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pierce DA, Preston DL. Radiation-related cancer risks at low doses among atomic bomb survivors. Radiat Res. 2000;154:178–186. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2000)154[0178:rrcral]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Land CE. Uncertainty, low-dose extrapolation and the threshold hypothesis. J Radiol Prot. 2002;22:A129–135. doi: 10.1088/0952-4746/22/3a/323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stewart AM, Webb KW, Hewitt D. A survey of childhood malignancies. Br Med J. 1958;1:1495–1508. doi: 10.1136/bmj.1.5086.1495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Monson RR, MacMahon B. Prenatal X-ray exposure and cancer in children. In: Boice JD Jr, Fraumeni JF Jr, editors. Radiation Carcinogenesis: Epidemiology and Biological Significance. Raven Press; New York: 1984. pp. 97–105. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Harvey EB, Boice JD, Jr, Honeyman M, Flannery JT. Prenatal X-ray exposure and childhood cancer in twins. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:541–545. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198502283120903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Boice JD, Jr, Miller RW. Childhood and adult cancer after intrauterine exposure to ionizing radiation. Teratology. 1999;59:227–233. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9926(199904)59:4<227::AID-TERA7>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) Annals ICRP. 1–2. Vol. 33. Pergamon; Oxford: 2003. Biological effects after prenatal irradiation (embryo and fetus) pp. 1–206. ICRP Publication 90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Doll R, Wakeford R. Risk of childhood cancer from fetal irradiation. Br J Radiol. 1997;70:130–139. doi: 10.1259/bjr.70.830.9135438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wakeford R, Little MP. Risk coefficients for childhood cancer after intrauterine irradiation: a review. Int J Radiat Biol. 2003;79:293–309. doi: 10.1080/0955300031000114729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Boice JD, Jr, Preston D, Davis FG, Monson RR. Frequent chest X-ray fluoroscopy and breast cancer incidence among tuberculosis patients in Massachusetts. Radiat Res. 1991;125:214–222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Howe GR, McLaughlin J. Breast cancer mortality between 1950 and 1987 after exposure to fractionated moderate-dose-rate ionizing radiation in the Canadian fluoroscopy cohort study and a comparison with breast cancer mortality in the atomic bomb survivors study. Radiat Res. 1996;145:694–707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Little MP, Boice JD., Jr Comparison of breast cancer incidence in the Massachusetts tuberculosis fluoroscopy cohort and in the Japanese atomic bomb survivors. Radiat Res. 1999;151:218–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements. NCRP Report No 64. NCRP; Bethesda, MD: 1980. Influence of dose and its distribution in time on dose–response relationships for low-LET radiations. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Davis FG, Boice JD, Jr, Hrubec Z, Monson RR. Cancer mortality in a radiation-exposed cohort of Massachusetts tuberculosis patients. Cancer Res. 1989;49:6130–6136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Howe GR. Lung cancer mortality between 1950 and 1987 after exposure to fractionated moderate-dose-rate ionizing radiation in the Canadian fluoroscopy cohort study and a comparison with lung cancer mortality in the atomic bomb survivors study. Radiat Res. 1995;142:295–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ronckers CM, Doody MM, Lonstein JE, Stovall M, Land CE. Multiple diagnostic X-rays for spine deformities and risk of breast cancer. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prevent. 2008;17:605–613. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-2628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ron E, Lubin JH, Shore RE, Mabuchi K, Modan B, Pottern LM, Schneider AB, Tucker MA, Boice JD., Jr Thyroid cancer after exposure to external radiation: a pooled analysis of seven studies. Radiat Res. 1995;141:259–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shore RE, Moseson M, Harley N, Pasternack BS. Tumors and other diseases following childhood X-ray treatment for ringworm of the scalp (tinea capitis) Health Phys. 2003;85:404–408. doi: 10.1097/00004032-200310000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lindberg S, Karlsson P, Arvidsson B, Holmberg E, Lundberg LM, Wallgren A. Cancer incidence after radiotherapy for skin haemangioma during infancy. Acta Oncol. 1995;34:735–740. doi: 10.3109/02841869509127180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lundell M, Hakulinen T, Holm L-E. Thyroid cancer after radiotherapy for skin hemangioma in infancy. Radiat Res. 1994;140:334–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Cardis E, Vrijheid M, Blettner M, Gilbert E, Hakama M, Hill C, Howe G, Kaldor J, et al. Risk of cancer after low doses of ionising radiation: retrospective cohort study in 15 countries. Br Med J. 2005;331:77–80. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38499.599861.E0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP) Annals ICRP. 1–3. Vol. 24. Pergamon; Oxford: 1994. Human respiratory tract model for radiological protection. A report of a Task Group of the International Commission on Radiological Protection; pp. 1–482. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Land CE. Estimating cancer risks from low doses of ionizing radiation. Science. 1980;209:1197–1203. doi: 10.1126/science.7403879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bonassi S, Ugolini D, Kirsch-Volders M, Stromberg U, Vermeulen R, Tucker JD. Human population studies with cytogenetic biomarkers: review of the literature and future prospectives. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2005;45:258–270. doi: 10.1002/em.20115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Norppa H, Bonassi S, Hansteen IL, Hagmar L, Stromberg U, Rossner P, Boffetta P, Lindholm C, Gundy S, Lazutka J, Cebulska-Wasilewska A, Fabianova E, Sram RJ, Knudsen LE, Barale R, Fucic A. Chromosomal aberrations and SCEs as biomarkers of cancer risk. Mutat Res. 2006;600:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.mrfmmm.2006.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Boffetta P, van der Hel O, Norppa H, Fabianova E, Fucic A, Gundy S, Lazutka J, Cebulska-Wasilewska A, Puskailerova D, Znaor A, Kelecsenyi Z, Kurtinaitis J, Rachtan J, Forni A, Vermeulen R, Bonassi S. Chromosomal aberrations and cancer risk: results of a cohort study from Central Europe. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:36–43. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwj367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tawn EJ, Whitehouse CA, Tarone RE. FISH chromosome aberration analysis on retired radiation workers from the Sellafield nuclear facility. Radiat Res. 2004;162:249–256. doi: 10.1667/rr3214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sasaki MS, Nomura T, Ejima Y, Utsumi H, Endo S, Saito I, Itoh T, Hoshi M. Experimental derivation of relative biological effectiveness of A-bomb neutrons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and implications for risk assessment. Radiat Res. 2008;170:101–117. doi: 10.1667/RR1249.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.IAEA. A Manual, IAEA Technical Report Series No. 405. International Atomic Energy Agency; Vienna: 2001. Cytogenetic Analysis for Radiation Dose Assessment. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bhatti P, Doody MM, Preston DL, Kampa D, Ron E, Weinstock RW, Simon S, Edwards AA, Sigurdson AJ. Increased frequency of chromosome translocations associated with diagnostic X-ray examinations. Radiat Res. 2008;170:149–155. doi: 10.1667/RR1422.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Edwards AA, Lloyd DC. Risks from ionising radiation: deterministic effects. J Radiol Prot. 1998;18:175–183. doi: 10.1088/0952-4746/18/3/004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Harris H. A long view of fashions in cancer research. Bioessays. 2005;27:833–838. doi: 10.1002/bies.20263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.National Council on Radiation Protection and Measurements. NCRP Report No. 136. NCRP; Bethesda, MD: 2001. Evaluation of the linear-nonthreshold dose–response model for ionizing radiation. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Brenner DJ, Doll R, Goodhead DT, Hall EJ, Land CE, Little JB, Lubin JH, Preston DL, Preston RJ, Puskin JS, Ron E, Sachs RK, Samet JM, Setlow RB, Zaider M. Cancer risks attributable to low doses of ionizing radiation: assessing what we really know. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:13761–13766. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2235592100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brenner DJ, Little JB, Sachs RK. The bystander effect in radiation oncogenesis. II. A quantitative model. Radiat Res. 2001;155:402–408. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)155[0402:tbeiro]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mothersill C, Smith RW, Agnihotri N, Seymour CB. Characterisation of a radiation-induced stress response communicated in vivo between zebrafish. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:3382–3387. doi: 10.1021/es062978n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Mancuso M, Pasquali E, Leonardi S, Tanori M, Rebessi S, Di Majo V, Pazzaglia S, Toni M-P, Pimpinella M, Covelli V, Saran A. Oncogenic bystander radiation effects in Patched heterozygous mouse cerebellum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:12445–12450. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804186105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Little MP, Wakeford R. The bystander effect in C3H 10T1/2 cells and radon-induced lung cancer. Radiat Res. 2001;156:695–699. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)156[0695:tbeicc]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nakanishi M, Tanaka K, Shintani T, Takahashi T, Kamada N. Chromosomal instability in acute myelocytic leukemia and myelodysplastic syndrome patients among atomic bomb survivors. J Radiat Res. 1999;40:159–167. doi: 10.1269/jrr.40.159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Nakanishi M, Tanaka K, Takahashi T, Kyo T, Dohy H, Fujiwara M, Kamada N. Microsatellite instability in acute myelocytic leukaemia developed from A-bomb survivors. Int J Radiat Biol. 2001;77:687–694. doi: 10.1080/095530000110047537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Little MP. Comments on the paper: microsatellite instability in acute myelocytic leukaemia developed from A-bomb survivors (letter to the editor) Int J Radiat Biol. 2002;78:441–443. doi: 10.1080/09553000110097956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cox R, Edwards AA. Comments on the paper: microsatellite instability in acute myelocytic leukaemia developed from A-bomb survivors–and related cytogenetic data (letter to the editor) Int J Radiat Biol. 2002;78:443–445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Littlefield LG, Travis LB, Sayer AM, Voelz GL, Jensen RH, Boice JD., Jr Cumulative genetic damage in hematopoietic stem cells in a patient with a 40-year exposure to alpha particles emitted by thorium dioxide. Radiat Res. 1997;148:135–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Salomaa S, Holmberg K, Lindholm C, Mustonen R, Tekkel M, Veidebaum T, Lambert B. Chromosomal instability in in vivo radiation exposed subjects. Int J Radiat Biol. 1998;74:771–779. doi: 10.1080/095530098141050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Tawn EJ, Whitehouse CA, Martin FA. Sequential chromosome aberration analysis following radiotherapy—no evidence for enhanced genomic instability. Mutat Res. 2000;465:45–51. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5718(99)00210-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Whitehouse CA, Tawn EJ. No evidence for chromosomal instability in radiation workers with in vivo exposure to plutonium. Radiat Res. 2001;156:467–475. doi: 10.1667/0033-7587(2001)156[0467:nefcii]2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]