Abstract

Although the WHO recommends the use of genotyping as a tool for epidemiological surveillance for mumps, limited data on mumps virus (MV) genotype circulation that may be used to trace the patterns of virus spread are available. We describe the first complete series of data from Spain. The small hydrophobic region was sequenced from 237 MV-positive samples from several regions of Spain collected between 1996 and 2007. Six different genotypes were identified: A, C, D (D1), G (G1, G2), H (H1, H2), and J. Genotype H1 was predominant during the epidemic that occurred from 1999 to 2003 but was replaced by genotype G1 as the dominant genotype in the epidemic that occurred from 2005 to 2007. The same genotype G1 strain caused concomitant outbreaks in different parts of the world (the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom). The remaining genotypes (genotypes A, C, D, and J) appeared in sporadic cases or small limited outbreaks. This pattern of circulation seems to reflect continuous viral circulation at the national level, despite the high rates of vaccine coverage.

Mumps is a highly transmissible but usually benign disease consisting of bilateral swelling of the salivary glands. In some instances, though, clinical complications can arise. Bilateral orchitis and clinical self-limited meningitis or more serious complications, such as encephalitis, deafness, male sexual sterility, and pancreatitis, may occur in rare cases (9).

Mumps virus (MV), a virus belonging to the genus Rubulavirus of the subfamily Paramyxovirinae, is considered monotypic regarding its antigenicity. Thus, mumps vaccination is part of the regular immunization schedule of many countries, usually along with the measles and rubella vaccination (i.e., the MMR vaccine) in a single formulation. However, in contrast to rubella and measles, secondary vaccine failure frequently allows MV circulation within highly immunized populations (1, 5, 8, 24, 36). The use of a poorly immunogenic genotype A strain called Rubini has been proposed as a cause of these major failures, although the occurrence of mumps in patients immunized with other vaccine strains has also been described (26).

Genetic variation in the small hydrophobic (SH) gene has led to the characterization of 12 genotypes, which are recognized by the WHO (13, 14, 23). Differential efficiency on cross neutralization among different genotypes has been suggested (20, 21), as have the differential capacities of certain strains to invade the neural system (25, 32). Finally, previous experience with the elimination programs for other preventable viral diseases, such as measles, rubella, and polio, suggest that genotyping would facilitate mumps surveillance (38), since the pattern of viral circulation can be traced. Consequently, molecular epidemiology studies have been performed around the world (2, 7, 10, 11, 12, 15, 17, 18, 23, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 41).

Mumps vaccination was introduced in the Spanish national vaccination repertoire in 1981 as part of the triple viral vaccine (the MMR vaccine). As a result, the number of mumps cases fell from 286,887 in 1984 to 1,527 in 2004. However, the general descendant trend was interrupted by some peaks: in 1989 (from 48,393 in 1987 to 83,527 in 1989), 1996 (from 7,002 in 1995 to 14,411 in 1996), 2000 (from 2,857 in 1998 to 9,391 in 2000), and 2007 (from 1,527 in 2004 to 10,219 in 2007). Surprisingly, these peaks occurred despite a national vaccine coverage rate of over 95% of the population by 1999. As has been previously reported (29, 30), the occurrence of vaccinated individuals with MV RNA present in their saliva and/or urine with viral IgG but not IgM in acute-phase serum was frequent, suggesting secondary vaccine failure. Although most secondary vaccine failures were associated with the use of at least one dose of the Rubini strain, cases of mumps in patients vaccinated with two doses of the Jerryl Lynn strain were also observed (29, 30).

In this report, we describe the MV genotypes circulating in Spain over the past 8 years. This represents the first series of data obtained for the national level. Interestingly, this series comprises three different epidemic peaks with two interepidemic periods with scarce viral circulation, allowing comparison of the pattern of genotype circulation under different epidemiological conditions.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Samples.

Two hundred thirty-seven samples positive for MV RNA by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) (see below) were included in the study and comprised the following three sets of samples. Set 1 consisted of 224 samples (202 saliva, 5 urine, 4 spinal fluid, and 13 oropharyngeal swab specimens in viral transport medium) that were received at the National Center for Microbiology (CNM) for the diagnosis of MV infection from 2000 to 2007 (Fig. 1). The majority of the samples collected between 2000 and 2003 originated from the autonomous community of Madrid (51 of 74 cases) in central Spain. After 2004, sampling was extended to other autonomous communities. Two aliquots of 100 μl each were made in the Sample Reception Unit upon arrival at CNM and were stored to −80°C until they were processed in the laboratory. Set 2 consisted of 10 virus isolates selected from a collection of 68 MV strains obtained at the Gran Canaria General Hospital Dr. Negrín, Gran Canaria Island (Canary Islands), Spain, from 1998 to 2000. These strains were obtained from the spinal fluid of patients with MV-associated meningitis. Set 3 consisted of 3 samples (2 spinal fluid samples and 1 serum sample) obtained from a retrospective panel (1988 to 1999) of 243 MV IgM-positive serum specimens and 21 spinal fluid specimens from patients with MV-associated meningitis. These specimens had been stored at −20°C for serological studies and had been thawed and frozen an unknown number of times.

FIG. 1.

Circulation of different mumps virus genotypes in Spain in relation to the clinical declaration of mumps to the mandatory information system. Both the sequences obtained in this study and the sequences published previously were included: 4 sequences from reference 23, 10 sequences from reference 18, 1 sequences from reference 4, and 8 sequences from reference 27.

Nucleic acid extraction.

Total nucleic acids were extracted from 100 μl of the original specimen with a Magna Pure LC total nucleic acid isolation kit in a Magna Pure LC automatic extractor (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany). Nucleic acids were resuspended in a final elution volume of 50 μl. Ten thousand molecules of synthetic RNA were included in the lysis solution as an internal control (6).

Amplification and sequencing methods.

Initial screening of sets 1 and 2 was performed by a previously described RT-PCR method, but we used a slight modification (22). The modification consisted of performance of the reverse transcription and the first amplification in a single step by means of the Access RT-PCR system kit (Promega Co., Madison, WI). Genotyping of the MV-positive samples was done by partial sequencing of the SH gene (23). Set 3 was studied directly by the genotyping RT-PCR described previously (23).

Sequence analysis.

Sequences were assigned to a given genotype by comparison with the sequences of reference strains (13). Subgrouping within genotypes H, G, and D was performed as described by Palacios et al. (23). The sequences were aligned by the use of Clustal X software and were analyzed by the MEGA (version 2.1) program. Phylogenetic trees were obtained by using the neighbor-joining and the Kimura two-parameter model of substitution with 1,000 bootstrap replications. Additional analysis by Bayesian inference with MrBayes (version 3.1) software improved the strength of the genotype assignation, when necessary (see below). When discrepancies with published data arose, the whole SH gene was sequenced to apply the reference criteria for genotype definition on the basis of simple homology (13).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

The GenBank accession numbers of the nucleotide sequences obtained in this study are found in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sequences described in this work

| Sequence name | GenBank accession no. | No. of sequencesa | Source location | Yr of recovery | Genotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2485NE | FJ919343 | 1 | Pontevedra | 2005 | G1 |

| 1501O | FJ919344 | 2 | Almería | 2005 | G1 |

| 2006O | FJ919345 | 2 | Logroño | 2006 | G1 |

| 804O | FJ919346 | 134 | Almería | 2005 | G1 |

| 1028O | FJ919347 | 2 | Almería | 2005 | G1 |

| 772O | FJ919348 | 1 | Cáceres | 2007 | G1 |

| 2393O | FJ919349 | 1 | Segovia | 2007 | G1 |

| 3736O | FJ919350 | 2 | Logroño | 2006 | G1 |

| 1459O | FJ919351 | 2 | Madrid | 2005 | G1 |

| 2384O | FJ919352 | 1 | Madrid | 2007 | G2 |

| 591O | FJ919353 | 13 | Madrid | 2005 | H2 |

| 1337O | FJ919354 | 1 | Madrid | 2005 | H2 |

| 2104O | FJ919355 | 31 | Madrid | 2000 | H1 |

| 8Canarias | FJ919356 | 1 | Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | 2000 | H1 |

| 1295O | FJ919357 | 1 | Palencia | 2002 | H1 |

| 10Canarias | FJ919358 | 1 | Las Palmas de Gran Canaria | 2000 | H1 |

| 556O | FJ919359 | 4 | Madrid | 2001 | H1 |

| 646O | FJ919360 | 1 | Madrid | 2001 | H1 |

| 1269O | FJ919361 | 10 | Madrid | 2000 | H1 |

| 857NE | FJ919362 | 2 | Ferrol | 1996 | H1 |

| 1290O | FJ919363 | 1 | Madrid | 2005 | H1 |

| 985O | FJ919364 | 8 | Almería | 2000 | D1 |

| 9820 | FJ919365 | 1 | Madrid | 2001 | D1 |

| 1818O | FJ919366 | 2 | Ceuta | 2007 | D1 |

| 1913O | FJ919367 | 2 | Ceuta | 2007 | D1 |

| 878O | FJ919368 | 3 | Murcia | 2006 | C |

| 1610NE | FJ919369 | 1 | Alicante | 1999 | C |

| 2780O | FJ919370 | 3 | Madrid | 2003 | J |

| 167O | FJ919371 | 2 | Madrid | 2001 | A |

The number of identical sequences represented by this accession number.

RESULTS

Genotype assignation of sequences obtained from samples.

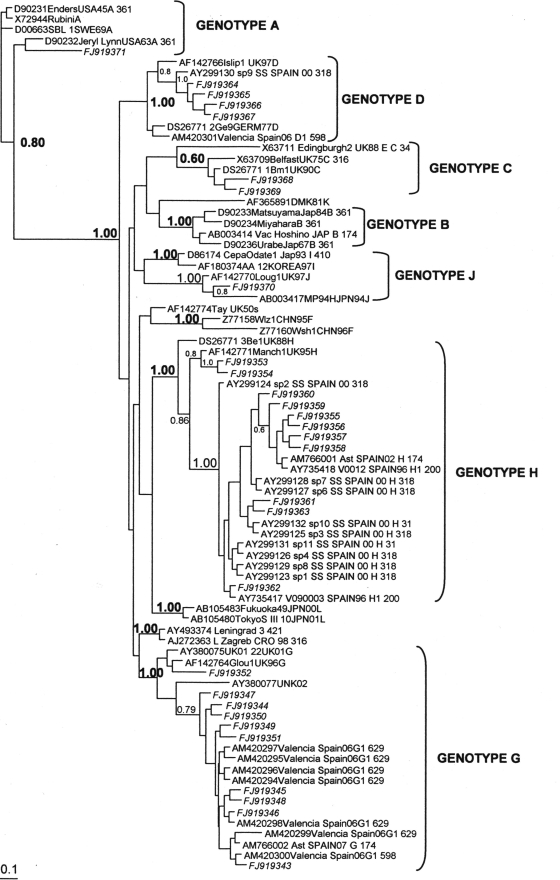

Six different MV genotypes (A, C, D, G, H, and J) were identified to have been circulating in Spain. Assignment to genotypes C, G, and H was based on low significant bootstrap values in the initial neighbor-joining phylogenetic analysis. Subsequent analysis by Bayesian inference clustered every sequence to a known genotype with significant bootstrapping values (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Phylogenetic relationships among mumps virus genotypes. The phylogenetic tree was obtained by Bayesian inference.

Of the 237 sequences obtained, 134 were identical sequences obtained from specimens collected between 2005 and 2007 (and represented in the tree as strain 804O05) and were classified as genotype G. These sequences were also identical to sequences obtained from mumps outbreaks in the United States and Canada in 2006 (37) and to the previously published sequence Ast/SP07. While the North American sequences had been characterized as genotype G, the sample collected in Asturias, Spain, in 2007 was proposed to be part of a new genotype whose reference strain would be strain UNK02-19 (4). To resolve this discrepancy, the entire SH gene (GenBank accession no. AM766002) was sequenced. Strain 804O05 was greater than 97.5% homologous with both genotype G reference strains but less than 92.7% homologous with the reference strains of the other genotypes as well as 92.4% homologous with strain UNK02-19. According to these data and following the criterion of the need for 95% homology in the whole SH gene (13, 38) to be able to assign a sequence to a preexisting genotype, both Ast/SP07 and our sequences of the same cluster belonged to genotype G.

Genotype circulation.

The different MV genotypes identified in this study are listed in Fig. 1. The results obtained before the year 1999 are based entirely on the results for 6 samples (0.024% of the 24,263 declared samples). A greater than 10-fold increase in the percentage of genotyped cases occurred during the epidemic between 1999 and 2004 (0.3%, 74/24,767 samples) due to enforced sampling in Madrid and the Canary Islands and even more in the last epidemic wave from 2005 to 2007, when most of the Spanish territory was covered, reaching 0.94% of mumps cases identified at the national level (181 of 19,237 cases; Fig. 1).

Genotype H1 was clearly dominant during the epidemic wave of 1999 to 2004. This genotype was also found in the few samples available from 1996 to 1998. The cocirculation of genotype D1 (9/43, 20.9%) together with the major genotype, genotype H1 (32/43, 74.4%), was regularly observed in Madrid during 2000 and 2001, as had been previously reported in San Sebastian (Basque Country; northern Spain) (18). However, genotype D1 was not found among the 10 strains identified from the Canary Islands. No associations between different epidemiological factors (age, gender, geographical area, vaccine status) and the presence of genotype H1 or D1 were found among the cases from Madrid (data not shown). The circulation of genotype H1 as the major genotype seemed to subside in 2004; coincidentally, the lowest number of cases in the series was recorded in that year (Fig. 1). Spanish strains clustered within the genotype H1 branch (Fig. 3) with other strains from Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and Argentina recovered in the same years, as well as with a group of sequences from Belarus (3). Genotype D1 strains were the most similar to those from an outbreak in Portugal in 1996 within a bigger genotype D1 group containing contemporary strains from other countries in Europe (Fig. 4). A single sequence of genotype C detected in 1999 was similar to the sequences of a group of strains circulating in Switzerland at that time (Fig. 5). Two cases with the same genotype A sequence were also detected in Madrid in January and February of 2001, together with genotypes H1 and D1. The comparison of this sequence with other genotype A sequences showed striking differences from the sequences of both vaccine and wild-type strains (Table 2). The positive controls used in the laboratory were also included to rule out laboratory contamination. According to these data, these two sequences seem to be those of new wild-type strains of genotype A. Both patients had received a single dose of vaccine 5 and 8 years before the mumps episode, respectively, and their vaccination records did not show that they had received further vaccinations. Further investigation is needed for the definitive classification of this strain, since the circulation of wild-type strains of genotype A has not been reported in recent years.

FIG. 3.

Phylogenetic relationships among genotype H strains. ▴, reference strains; •, strains detected during this study.

FIG. 4.

Phylogenetic relationships among genotype D strains. ▴, reference strains; •, strains detected during this study.

FIG. 5.

Phylogenetic relationships among genotype C strains. ▴, reference strains; •, strains detected during this study.

TABLE 2.

Nucleotides at various positions in the sequences of vaccine and wild-type genotype A strains compared to those in the genotype A strain described in this papera

| Strain | Sequence at the following position (start codon SH): |

No. of nucleotide differences | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11 | 18 | 40 | 42 | 45 | 47 | 57 | 60 | 69 | 84 | 86 | 88 | 93 | 96 | 99 | 100 | 105 | 109 | 114 | 117 | 118 | 132 | 135 | 136 | 141 | 143 | 156 | 159 | ||

| FJ919371 reference strain | T | C | T | G | A | T | T | A | T | C | C | C | T | C | A | C | G | G | T | G | T | T | G | C | T | T | C | T | |

| FJ919371 167O01 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 0 |

| FJ919371 342O01 | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | 0 |

| D90232Jeryl-LynnUSA63A.361 | . | T | . | . | . | C | . | . | . | T | T | T | C | T | . | . | T | . | . | . | . | C | . | . | C | . | T | . | 11 |

| X63707.Jeryl | . | T | . | . | . | C | . | . | . | T | T | T | C | T | . | . | T | . | . | . | . | C | . | . | C | . | T | . | 11 |

| AF345290_JERYL-LYNN_minor | . | T | . | . | . | C | . | . | . | T | T | T | C | T | . | . | T | . | . | . | C | C | . | A | C | . | T | . | 13 |

| U50283_4098_SWE_93_A_300 | A | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | T | T | T | C | T | . | . | . | . | . | A | . | C | . | . | C | G | T | . | 11 |

| D90231EndersUSA45A.361 | . | T | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | T | T | T | C | T | . | . | . | . | . | A | . | C | . | . | C | G | T | . | 11 |

| DQ268536_KM_CHN_438 | . | T | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | T | T | T | C | T | . | . | . | . | . | A | . | C | . | . | C | G | T | . | 11 |

| X72944Rubini | . | T | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | T | T | T | C | T | . | . | . | . | . | A | . | C | . | . | C | G | T | . | 11 |

| Control + Rubini laboratory control | . | T | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | T | T | T | C | T | . | . | . | . | . | A | . | C | . | . | C | G | T | . | 11 |

| X63705.ENDERS.UK.A.348 | . | T | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | T | T | T | C | T | . | . | . | . | . | A | . | C | . | . | C | G | T | . | 11 |

| X63704.SBL1.UK92.348 | A | T | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | T | T | T | C | T | . | . | . | . | . | A | . | C | . | . | C | G | T | . | 12 |

| M25421_SWED_88_310 | A | T | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | T | T | T | C | T | . | . | . | . | . | A | . | C | . | . | C | G | T | . | 12 |

| D00663SBL-1SWE69A | A | T | . | . | . | . | . | . | . | T | T | T | C | T | . | . | . | . | . | A | . | C | . | . | C | G | T | . | 12 |

| AF201473.Jeryl-ynn.USA.A.316 | . | T | G | . | . | . | . | C | C | T | T | T | . | T | . | T | . | . | G | A | . | C | . | . | C | . | T | . | 14 |

| Control + Jerryl-Lynn laboratory control | . | T | G | . | . | . | . | C | C | T | T | T | . | T | . | T | . | . | G | A | . | C | . | . | C | . | T | . | 14 |

| AY735440 ARGENTINA96 | . | T | G | . | . | . | . | C | C | T | T | T | . | T | . | T | . | . | G | A | . | C | . | . | C | . | T | . | 14 |

| AF338106_JERYL-YNN_major | . | T | G | . | . | . | . | C | C | T | T | T | . | T | . | T | . | . | G | A | . | C | . | . | C | . | T | . | 14 |

| AY735441 ARGENTINA95 | . | T | G | . | . | . | . | C | C | T | T | T | . | T | . | T | . | . | G | A | . | C | . | . | C | . | T | . | 14 |

| AY735439 ARGENTINA96 | . | T | G | . | . | . | . | C | C | T | T | T | . | T | . | T | . | . | G | A | . | C | . | . | C | . | T | . | 14 |

| KX63706_KILHAM_UK_A348 | . | T | . | A | G | . | C | . | . | T | T | T | C | T | C | T | . | A | . | A | . | C | . | . | C | . | T | . | 16 |

| AY735438_ARGENTINA94 | . | T | G | . | . | . | . | C | C | T | T | T | . | T | C | T | . | . | G | A | . | C | A | A | C | . | T | C | 18 |

The sequences of the positive controls (Jerryl-Lynn and Rubini) used in the laboratory are also included.

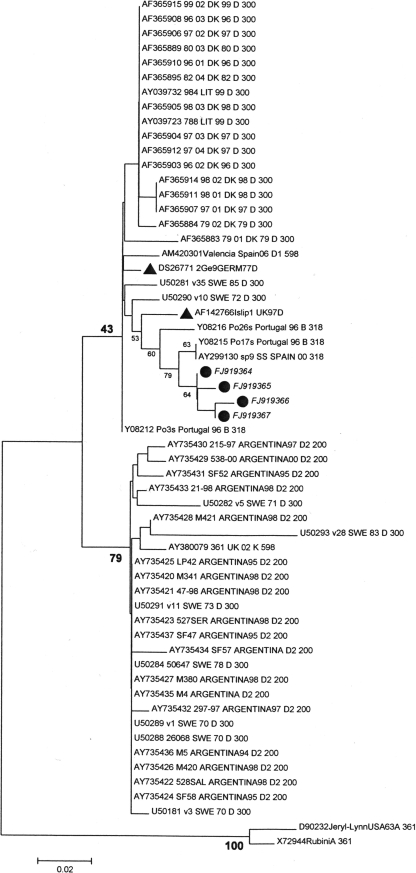

The number of notifications started to increase again in 2005 due to simultaneous outbreaks caused by genotype H2 strains in Segovia (Castilla-León, central Spain) and genotype G1 strains in Almería (Andalusia, southern Spain) from May to July, causing concomitant individual cases in Madrid together with others caused by genotype J (Fig. 1). These genotype H2 strains clustered with a group of sequences from Israel and Palestine collected in 2004 (Fig. 3). A single genotype G1 strain detected in an encephalitis patient from Pontevedra (Galicia, northwestern Spain) in October 2005 was the only available representative of that genotype from the hundreds of cases during that outbreak. In 2006, genotype G1 spread throughout the Spanish territory. At the time of this work's submission, genotype G1 was still the dominant circulating genotype, as demonstrated by reports from Asturias (4) and Valencia (27). Since 2006, only three cases of MV genotype C infections in Murcia (southeastern Spain), a single case of an MV genotype D1 infection in the North African city of Ceuta, Morocco, and an isolated case of a genotype G2 infection from Madrid have been detected. The dominant genotype G1 strain was very similar to those causing large outbreaks in the United States and Canada, as well as to a single strain from Croatia (28, 37) (Fig. 6).

FIG. 6.

Phylogenetic relationships among genotype G strains. ▴, reference strains; •, strains detected during this study.

DISCUSSION

Genotyping is a basic tool used for epidemiological surveillance of vaccine-preventable viral diseases. In order to provide these surveillance programs with universal tools enabling worldwide surveillance, the WHO has established standard genotype nomenclature, reference strains, and target genomic sequences for the viruses included in the triple viral MMR vaccine: measles virus (39), mumps virus (13, 38), and rubella virus (40). Data from as many countries as possible are required to understand the epidemiological significance of genotyping data. However, in the case of the mumps virus, the amount of available data is far from optimal. In this work, we contribute the first series of data covering a period of 10 years on the MV genotypes in general circulation in Spain.

Previous available data on local outbreaks in San Sebastian (18), Valencia (27), and Asturias (4) concur with our data. The dominance of a single genotype at the national level was associated with periods of reporting of high rates of mumps to the national surveillance system.

In this series, three epidemic waves of mumps cases were observed. Interestingly, dominant genotype replacement occurred after mumps reporting decreased to minimum levels. Genotype H1 was dominant between 1999 and 2003 but was successfully replaced by G1 after a “silent” period of 2 years with scarce mumps circulation. On the other hand, although data from 1996 to 1998 are limited, the genotype H1 strain was also detected during that period, suggesting that the end of an epidemic wave was not always followed by a genotype replacement. Although a temporal shift in MV genotype circulation was described previously (10, 11, 12, 16, 26, 33), we believe that this is the first report establishing a link between cyclic variations, genotype, and mumps prevalence.

The pattern observed during the epidemic waves (the circulation of a dominant genotype) seems to reflect continuous viral circulation, in accordance with the clinical data. Even though the rates of vaccine coverage were identically high for measles and mumps viruses, the measles virus showed a different pattern (e.g., a variety of genotypes associated with unrelated local outbreaks) (19). The latter pattern correlates with the interruption of measles virus circulation at the national level, as reflected by case reports (19). These results highlight the relatively low efficiency of the mumps vaccine in comparison with that of the measles vaccine. The use of the Rubini strain in Spain between 1993 and 1999 for mumps vaccination could be an important factor to explain this low efficiency.

Interestingly, genotype H2 strains were not able to establish circulation at the national level, even though they caused a local outbreak in Segovia that radiated cases to Madrid. However, genotype G1 succeeded in spreading shortly after that. The same G1 strain was also reported from many other parts of the world (28, 37), suggesting an enhanced ability to spread within vaccinated populations. Similarly, another genotype, genotype D1, was able to establish circulation concomitantly with the dominant genotype, genotype H1, during 2000 and 2001, as reported in Switzerland (35). The selective forces that led to the extinction of circulating genotypes and caused the further onset of particular strains are unknown. The differential ability of vaccine-induced antibodies to neutralize different MV genotypes suggested by some authors (21) might account for part of the explanation for these positive selection events; we believe that our data support this theory and that they thus warrant additional investigation. The different histories of genotype importation, the variations in vaccine coverage rates, and the use of different vaccine strains in each country draw a complex global picture that could be the cause of the different geographical patterns of mumps virus genotype circulation observed in the United Kingdom (12), Japan (31), and Switzerland (35).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Genomics Unit of the Instituto de Salud Carlos III for carrying out all the automatic sequencing. We also thank the technicians of the Viral Detection and Isolation Unit (Service of Diagnostic Microbiology) of the National Center of Microbiology for their assistance and especially Irene González for the nucleic acid extractions and Francisco Salvador for the preparation of the PCR master mixtures for diagnosis. We also thank the staff of the Sample Reception Unit of the National Center of Microbiology for their work on sample identification and preparation. We also thank Nazir Savji from the Center for Infection and Immunity for his help with editing the manuscript.

This study has been partially supported by project MPY1190/02 of the research program of the Carlos III Health Institute.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 27 January 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Afzal, M. A., J. Buchanan, J. A. Dias, M. Cordeiro, M. L. Bentley, C. A. Shorrock, and P. D. Minor. 1997. RT-PCR based diagnosis and molecular characterisation of mumps viruses derived from clinical specimens collected during the 1996 mumps outbreak in Portugal. J. Med. Virol. 52:349-353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atrasheuskaya, A. V., M. V. Kulak, S. Rubin, and G. M. Ignatyev. 2007. Mumps vaccine failure investigation in Novosibirsk, Russia, 2002-2004. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 13:670-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Atrasheuskaya, A. V., E. M. Blatun, M. V. Kulak, A. Atrasheuskaya, I. A. Karpov, S. Rubin, and G. M. Ignatyev. 2007. Investigation of mumps vaccine failures in Minsk, Belarus, 2001-2003. Vaccine 25:4651-4658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boga, J. A., M. de Oña, A. Fernández-Verdugo, D. González, A. Morilla, M. Arias, L. Barreiro, F. Hidalgo, and S. Melón. 2008. Molecular identification of two genotypes of mumps virus causing two regional outbreaks in Asturias, Spain. J. Clin. Virol. 42:425-428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Briss, P. A., L. J. Fehrs, R. A. Parker, P. F. Wright, E. C. Sannella, R. H. Hutcheson, and W. Schaffner. 1994. Sustained transmission of mumps in a highly vaccinated population: assessment of primary vaccine failure and waning vaccine-induced immunity. J. Infect. Dis. 169:77-82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Echevarría, J. E., A. Avellón, J. Juste, M. Vera, and C. Ibáñez. 2001. Screening of active lyssavirus infection in wild bat populations by viral RNA on oropharyngeal swabs. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39:3678-3683. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heider, A., G. Ignatyev, E. Gerike, and E. Schreier. 1997. Genotypic characterization of mumps virus isolated in Russia (Siberia). Res. Virol. 148:433-435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hersh, B. S., P. E. M. Fine, W. K. Kent, S. L. Cochi, L. H. Khan, E. R. Zell, et al. 1991. Mumps outbreak in a highly vaccinated population. J. Pediatr. 119:187-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hviid, A., S. Rubin, and K. Mühlemann. 2008. Mumps. Lancet 371:932-944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Inou, Y., T. Nakayama, N. Yoshida, H. Uejima, K. Yuri, M. Kamada, T. Kumagai, H. Sakiyama, A. Miyata, H. Ochiai, T. Ihara, T. Okafuji, T. Okafuji, T. Nagai, E. Suzuki, K. Shimomura, Y. Ito, and C. Miyazaki. 2004. Molecular epidemiology of mumps virus in Japan and proposal of two new genotypes. J. Med. Virol. 73:97-104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jin, L., S. Beard, and D. W. Brown. 1999. Genetic heterogeneity of mumps virus in the United Kingdom: identification of two new genotypes. J. Infect. Dis. 180:829-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jin, L., D. W. Brown, P. A. Litton, and J. M. White. 2004. Genetic diversity of mumps virus in oral fluid specimens: application to mumps epidemiological study. J. Infect. Dis. 189:1001-1008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jin, L., B. Rima, D. Brown, C. Orvell, T. Tecle, M. Afzal, K. Uchida, T. Nakayama, J. W. Song, C. Kang, P. A. Rota, W. Xu, and D. Featherstone. 2005. Proposal for genetic characterisation of wild-type mumps strains: preliminary standardisation of the nomenclature. Arch. Virol. 150:1903-1909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansson, B., T. Tecle, and C. Örvell. 2002. Proposed criteria for classification of new genotypes of mumps virus. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 34:355-357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim, S. H., K. J. Song, Y. K. Shin, J. H. Kim, S. M. Choi, K. S. Park, L. J. Baek, Y. J. Lee, and J. W. Song. 2000. Phylogenetic analysis of the small hydrophobic (SH) gene of mumps virus in Korea: identification of a new genotype. Microbiol. Immunol. 44:173-177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee, J. Y., Y. Y. Kim, G. C. Shin, B. K. Na, J. S. Lee, H. D. Lee, J. H. Kim, W. J. Kim, J. Kim, C. Kang, and H. W. Cho. 2003. Molecular characterization of two genotypes of mumps virus circulated in Korea during 1998-2001. Virus Res. 97:111-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee, J. Y., B. K. Na, J. H. Kim, J. S. Lee, J. W. Park, G. C. Shin, H. W. Cho, H. D. Lee, U. Y. Gou, B. K. Yang, J. Kim, C. Kang, and W. J. Kim. 2004. Regional outbreak of mumps due to genotype H in Korea in 1999. J. Med. Virol. 73:85-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Montes, M., G. Cilla, J. Artieda, D. Vicente, and M. Basterretxea. 2002. Mumps outbreak in vaccinated children in Gipuzkoa (Basque Country), Spain. Epidemiol. Infect. 129:551-556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mosquera, M., F. de Ory, J. E. Echevarría, and the Network of Laboratories in the Spanish National Measles Elimination Plan. 2005. Measles virus genotype circulation in Spain after implementation of the National Measles Elimination Plan 2001-2003. J. Med. Virol. 75:137-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nojd, J., T. Tecle, A. Samuelsson, and C. Orvell. 2001. Mumps virus neutralizing antibodies do not protect against reinfection with a heterologous mumps virus genotype. Vaccine 19:1727-1731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Orvell, C., T. Tecle, B. Johansson, H. Saito, and A. Samuelson. 2002. Antigenic relationships between six genotypes of the small hydrophobic protein gene of mumps virus. J. Gen. Virol. 83:2489-2496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Palacios, G., C. Rodriguez, D. Cisterna, M. C. Freire, and J. Cello. 2000. Nested PCR for rapid detection of mumps virus in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with neurological diseases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38:274-278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Palacios, G., O. Jabado, D. Cisterna, F. de Ory, N. Renwick, J. E. Echevarria, A. Castellanos, M. Mosquera, M. C. Freire, R. H. Campos, and W. I. Lipkin. 2005. Molecular identification of mumps virus genotypes from clinical samples: standardized method of analysis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 43:1869-1878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pons, C., T. Pelayo, I. Pachón, A. Galmes, L. Gonzalez, G. Sánchez, and F. Martinez. 2000. Two outbreaks of mumps in children vaccinated with the Rubini strain in Spain indicate low vaccine efficacy. Euro Surveill. 5:80-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rafiefard, F., B. Johansson, T. Tecle, and C. Örvell. 2005. Characterization of mumps virus strains with varying neurovirulence. Scand. J. Infect. Dis. 37:330-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richard, J. L., M. Zwahlen, M. Feuz, and M. C. Matter. 2003. Comparison of the effectiveness of two mumps vaccines during an outbreak in Switzerland in 1999 and 2000: a case-cohort study. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 18:569-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Roig, F. J., M. A. Bracho, R. Caebó, E. Giner, F. González, S. Guiral, C. Monedero, and A. Salazar. 2006. Brote epidémico por virus de la parotiditis genotipo G1. Bol. Epidemiol. Sem. 14:25-36. http://www.isciii.es/htdocs/centros/epidemiologia/boletin_semanal/bes0606.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Santak, M., T. Kosutic-Gulija, G. Tesovic, S. Ljubin-Sternak, I. Gjenero-Margan, L. Betica-Radic, and D. Forcic. 2006. Mumps virus strains isolated in Croatia in 1998 and 2005: genotyping and putative antigenic relatedness to vaccine strains. J. Med. Virol. 78:638-643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sanz, J. C., M. Mosquera, J. E. Echevarría, M. Fernández, N. Herranz, G. Palacios, and F. de Ory. 2006. Sensitivity and specificity of immunoglobulin G titer for diagnostics of mumps virus in infected patients depending on vaccination status. APMIS 114:788-794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sanz-Moreno, J. C., A. Limia-Sánchez, L. García-Comas, M. M. Mosquera-Gutiérrez, J. E. Echevarría-Mayo, A. Castellanos-Nadal, and F. de Ory-Manchón. 2005. Detection of secondary mumps vaccine failure by means of avidity testing for specific immunoglobulin G. Vaccine 23:4921-4925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takahashi, M., T. Nakayama, Y. Kashiwagi, T. Takami, S. Sonoda, T. Yamanaka, H. Ochiai, T. Ihara, and T. Tajima. 2000. Single genotype of measles virus is dominant whereas several genotypes of mumps virus are co-circulating. J. Med. Virol. 62:278-285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tecle, T., B. Johansson, A. Jejcic, M. Forsgren, and C. Örvell. 1998. Characterization of three co-circulating genotypes of the small hydrophobic protein gene of mumps virus. J. Gen. Virol. 79:2929-2937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tecle, T., B. Bottiger, C. Orvell, and B. Johansson. 2001. Characterization of two decades of temporal co-circulation of four mumps virus genotypes in Denmark: identification of a new genotype. J. Gen. Virol. 82:2675-2680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uchida, K., M. Shinohara, S. Shimada, Y. Segawa, and Y. Hoshino. 2001. Characterization of mumps virus isolated in Saitama Prefecture, Japan, by sequence analysis of the SH gene. Microbiol. Immunol. 45:851-855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Utz, S., J. L. Richard, S. Capaul, H. C. Matter, M. G. Hrisoho, and K. Muhlemann. 2004. Phylogenetic analysis of clinical mumps virus isolates from vaccinated and non-vaccinated patients with mumps during an outbreak, Switzerland 1998-2000. J. Med. Virol. 73:91-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vandermeulen, C., M. Roelants, M. Vermoere, K. Roseeuw, P. Goubau, and K. Hoppenbrouwers. 2004. Outbreak of mumps in a vaccinated child population: a question of vaccine failure? Vaccine 22:2713-2716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Watson-Creed, G., A. Saunders, J. Scott, L. Lowe, J. Pettipas, and T. Hattchete. 2006. Two successive outbreaks of mumps in Nova Scotia among vaccinated adolescents and young adults. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 175:484-488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.WHO. 2005. Global status of mumps immunization and surveillance. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 48:418-424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.WHO. 2005. New genotype of measles virus and update on global distribution of measles genotypes. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 80:347-351. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.WHO. 2007. Update of standard nomenclature for wild type rubella viruses, 2007. Wkly. Epidemiol. Rec. 82:216-222. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu, L., Z. Bai, Y. Li, B. K. Rima, and M. A. Afzal. 1998. Wild type mumps viruses circulating in China establish a new genotype. Vaccine 16:281-285. (Erratum, 16:759.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]