Abstract

This paper offers a stress theory based conceptual framework for understanding proactive options for care-getting for patients living with cancer that is also relevant to patients living with other chronic or life threatening illnesses. Barriers and facilitators to active efforts for obtaining responsive care from both informal and formal sources are discussed. This “Care-Getting” model explores benefits of proactive care-getting for diminishing physical discomfort/suffering, burden of illness and disability, and psychological distress. We highlight unique issues in care-getting that patients face at different stages of the life course. Implications of prior research related to the model for practice and intervention are discussed.

KEY TERMS: Care-getting, life course, cancer care, marshalling care, activated patient

In this paper, the special needs of patients as care recipients will be highlighted by focusing on challenges of patients facing serious chronic illness, as exemplified by cancer. Such illness-related challenges are normative for the very old, but also apply to all individuals who face life-threatening illness throughout the life course. The discussion considers proactive adaptations by patients, throughout the life course, who deal with life threatening illness such as cancer. Care-getting refers to active efforts by patients to obtain responsive care from both informal and formal sources. The former include family and friends, while the latter involve health care professionals. Care-getting is distinct from the commonly studied phenomenon of caregiving that describes provision of assistance, often provided by family members in the context of major illness situations. The timeliness of focusing on care-getting is underscored by the virtual absence of discourse on the challenges of care-getting among the chronically ill, despite extensive focus on issues of caregiving. Accordingly, successful care-getting may be viewed as a critical goal during a disabling illness (Wagner, Austin, Davis, Hindmarsh, Schaefer, & Bonomi, 2001). An understanding of the maintenance of good quality of life among chronically ill patients has been limited by the lack of systematic theoretical attention to care-getting throughout the life course. This paper synthesizes orientations from the fields of sociology, social work, nursing, and psychology to expand conceptual understanding of this critical area. We build on a stress theoretical framework (Pearlin, 1989) to help appreciate the unique challenges faced by chronically ill patients. Mastery of the adaptive tasks of care-getting involves marshalling informal and formal support, which allows for obtaining the best medical care and the maintenance of comfort, psychological well-being, and a sense of being cared for (Nolan & Mock, 2004).

Even though cancer is more treatable today than in the past and the number of survivors has grown, a cancer diagnosis is still one of the most feared introductions to the world of chronic and life threatening illness (Dolbeault, Szporn, & Holland, 1999; Harpham, 1995). Patients living with cancer face uncertain futures and suffer from symptoms due to their illness as well as the treatments that they must undergo (Ng, Alt, & Gore, 2007). Indeed, treatment for cancer may involve surgery, radiation, chemotherapy and other interventions, which carry both immediate and long-term side effects. Cancer patients may need varying levels of care during the active treatment and after-treatment phases of their illness.

Fatigue, pain, functional limitations, and emotional distress are common by-products of living with cancer (Hewitt, Greenfield, & Stovall, 2006). Given that cancer has been considered to be a highly stigmatized condition (Wolff, 2007), many cancer patients face challenges in care-getting. Many patients with cancer are reluctant to disclose the nature of their illness to friends, neighbors, and co-workers, who might otherwise be natural sources of instrumental and emotional support. In terms of challenges of formal care-getting, patients must interact with a variety of specialists during their cancer experience. It is not uncommon for patients to see surgeons, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists, in addition to follow-ups by their primary care physicians. Care-getting also poses unique challenges during the post-treatment (reentry) period, when uncertainty and ambiguity about availability of caregivers pose problems for patients (Richey & Brown, 2007).

Being diagnosed with cancer at different points during the life course presents patients with unique issues in their efforts to successfully and proactively marshal support (Kahana & Kahana, 2007a). Patients who show initiative and express assertiveness in communicating with caregivers and health care providers receive more responsive care that considers their values and preferences (Kahana & Kahana, 2007a). They may maintain control even in the face of illness, by having meaningful involvement in treatment decision making (O’Hair, Kreps, & Sparks, 2007). Our research focusing on elderly cancer patients indicated that proactivity as health care consumers is not widely practiced among the old-old (Kahana, et al., in press). Nevertheless, it is noteworthy that a large proportion of elderly patients endorse proactive health care consumerism in giving advice to other cancer patients.

Features of the family structure change for individuals as they move through the life course, thereby affecting availability of caregivers (Pearlin & Zarit, 1993). The age, relationship, and resources of the most likely caregivers also shape patients’ options for care-getting, as they aim to marshal informal support and responsive medical care at different stages during the life course. Focus on maintenance of the self during chronic illness underscores the abiding desire of human beings to maintain their long established identity, retain autonomy, and garner respect from their social environment, for their values, preferences, and cultural diversity (George, 1999). Throughout much of adult life and well into healthy old age, this identity can be autonomously maintained. Being diagnosed with a serious illness such as cancer poses a challenge to this self reliant, autonomous identity. This challenge and its successful resolution present a key adaptive task of proactive care-getting during the life course. The type of care that results in maintaining a sense of dignity while being cared for has been discussed in the work of Noddings (2003). Such care cannot be perfunctory or grudging, and must reflect regard for the views and interests of the person being cared for. Autonomy and agency may be exercised by patients by taking initiatives and expressing assertiveness in order to elicit optimal care (Kahana & Kahana, 2007a).

The proactive care-getting model proposed here describes how patients can play an active role in obtaining responsive and nurturing care in dealing with life threatening illness (Nolan & Mock, 2004). Our prior research has focused on adaptation to frailty among older adults, who are part of an ongoing longitudinal study (Kahana & Kahana, 2003a). While our discussion is informed by an in-depth understanding of care-getting in late life, we will address some of the unique issues that apply to patients at different points in the life course.

SPECIFYING THE CARE-GETTING MODEL

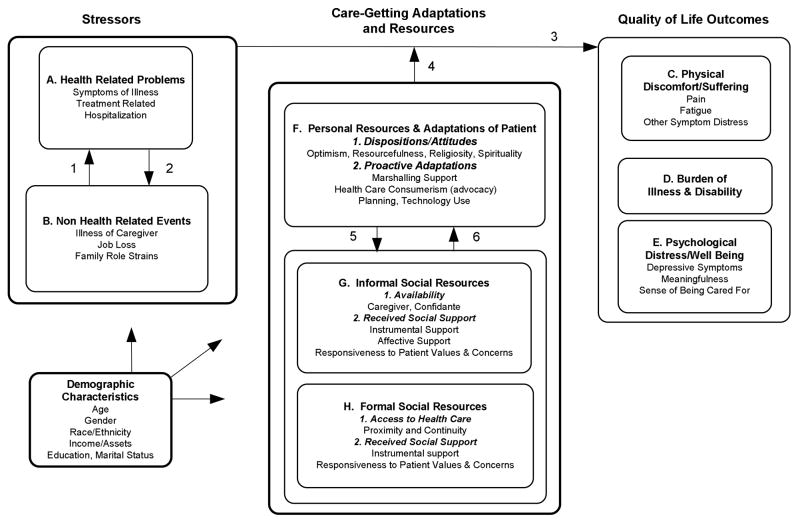

The proposed care-getting model for understanding the maintenance of a good quality of life in the face of chronic illness is anchored in our previously articulated proactivity based model of successful aging (Kahana & Kahana 1996; 2003a) (Figure 1). This stress theory based model emphasizes the normative nature of health related stressors and social losses. It is argued that individuals must adapt proactively to insure that they can maintain good quality of life, even as they face physical impairments due to chronic illness and encounter acute health events. The care-getting model presented here emphasizes the role of proactive initiatives for using informal and formal social resources to deal with adaptive tasks of chronic illness (Moos & Schaefer, 1986). Successful care-getting helps patients secure advocates who can represent their values and wishes, even when these patients cannot do so for themselves.

Figure 1.

Care-Getting Model for Cancer Patients Across the Life Course

The following section presents elements in the proposed model and their linkages (Figure 1). Path numbers indicate the direction of proposed causal linkages. First antecedent stressors are described, followed by quality of life outcomes. We then turn to moderators, which encompass care-getting adaptations and resources and receipt of patient responsive informal and formal care. Finally, we illustrate how demographic context, representing life chances and structural constraints, may impinge on elements of the care-getting model (Giele & Elder, 1998). We also briefly describe relevant findings provided by our empirical work.

Stressors

Stressors are depicted as the independent variables that threaten quality of life outcomes (Figure 1, Components A and B). Both health-related problems, such as hospitalizations and other negative life events, such as illness of a caregiver, are considered as they impact on the quality of the cancer patient’s life (Path 3).

A. Health-related problems

Health-related problems resulting from cancer and its treatment can disrupt functioning and result in difficult recuperation (Empana, Dargent-Molina, & Breart, 2004). Patients dealing with diverse cancers may experience a broad range of symptoms. Invasive cancer treatments ranging from surgery to chemotherapy and radiation can contribute to additional health-related problems. When hospitalization is required for symptoms or for treatment, the patient experiences additional environmental stressors that are likely to adversely impact quality of life (Path 3).

B. Non health-related events

Social losses are often associated with chronic illness such as cancer, where job loss or divorce might add to the patient’s sustained inability to function (Thornton & Perez, 2007). These losses can also adversely affect psychological well-being and quality of life (Path 3). Patients may also face additional stressors due to illness of caregivers such as a spouse, close family members, or friends (Krause, 2006).

Health related stressors and other critical life events may have reciprocal effects (Path 1). On the one hand, hospitalization or cancer treatments may precipitate job loss (Path 1). On the other hand, illness and unavailability of significant other caregivers could result in the need for hospitalization of the patient (Path 2).

Quality of Life Outcomes

Three categories of quality of life outcomes are particularly salient in relation to chronic illness such as cancer: physical discomfort/suffering, burden of illness and disability, and psychological distress/well-being (Figure 1, Quality of Life Components C, D, and E).

C. Physical Discomfort/Suffering

Physical discomfort, including pain, fatigue, and other indicators of symptom distress such as nausea, is a key component of suffering due to cancer and cancer treatments (Path 3) (Cohen, Musgrave, McQuire, Strumpf, Munsell Mendoza, et al., 2005). Limiting these symptoms gains particular salience for patients with advanced disease who may be nearing the end of life (Somogyi-Zalud, Zhong, Lynn, & Hamel, 2000).

D. Burden of Illness and Disability

As seriously ill patients develop functional limitations and disability, the experience of an altered self assumes major importance (Penrod & Martin, 2003). To the extent that patients believe that they are stigmatized for their illness and feel prevented from performing important social functions, they develop negative self evaluation and outcome expectations termed “burden of disability”.

E. Psychological Distress/Well-being

Physical symptoms and impairments reduce the psychological quality of life of chronically ill patients (Path 3) (Schieman & Turner, 1998). Depressive symptoms can result from exposure to chronic illness and critical life events (Path 3) (Koenig & Blazer, 1992). A seriously ill patient who regularly experiences pain may still maintain self-esteem and escape despair by finding meaning in life (Lynn, 2000). A sense of “being cared for” is proposed as a unique and salient dimension of psychological well-being relevant to successful care-getting among those suffering from life threatening illness (Watson, 2005).

Care-Getting Adaptations and Resources

Ameliorative resources (Figure 1, Components F, G, and H) play a moderating role in our care-getting model (Path 4). Personal resources of the patient (Component F) are reflected in psychological dispositions or attitudes and in proactive adaptations, which can help mobilize social resources (Path 5). Informal (Component G) and formal (Component H) social resources, such as access to family caregivers and to medical care, are also considered as moderators that can diminish the adverse effects of serious illness and critical life events on the individual’s quality of life (Antonucci, 1990). We also conceptualize social resources as potentially facilitating proactive adaptations (Path 6).

The “Care-getting Model” proposed here builds on our previously proposed Proactivity Model (Kahana & Kahana, 2003b) of Successful Aging. Proactive behaviors (e.g. helping others, planning, and marshalling support) that can position older adults for successful aging are also valuable for understanding maintenance of quality of life during serious illness. It is useful to focus on adaptations that best contribute to successful care-getting from both informal and formal providers of support throughout the life course.

Personal resources reflect dispositions and attitudes that contribute to proactive behavioral adaptations. Although dispositional characteristics have been shown to be enduring (Costa & McCrae, 1990; Carver & Scheier, 1989), there is growing evidence that the environmental context may influence dispositional characteristics. The positive psychology movement has offered a new theoretical framework wherein optimism may be learned (Seligman, 1991; Peterson, 2000). Indeed, recent approaches to health promotion and coping with illness have underscored the value of cultivating positive emotions such as optimism and spirituality in order to enhance health and well-being (Frederickson, 2000; Gilham & Reivich, 2004).

F. Personal Resources and Adaptations Promoting Care-Getting

1. Dispositions/Attitudes

Optimism

Research has shown that adaptation to stressors, including those due to illness, may vary based on whether an individual has an optimistic or pessimistic life orientation (Scheier & Carver, 1985). Optimism is typically viewed as a dispositional, trait-like characteristic and has been found in prior health research to diminish distress outcomes (Facione, 2002). Optimism can thus help ameliorate adverse stress effects (Path 4). Additionally, optimistic dispositions contribute to social competence, which is needed to help marshal care and support, and which can also elicit positive responses from caregivers (Path 5) (Krause, 2006).

Resourcefulness

This concept has been proposed by nurse researchers as a particularly useful dispositional characteristic for coping with health related stressors (Zausniewski, 1994). It is predicated on a belief in one’s ability to cope effectively with adversity. Resourcefulness can allow for positive reframing of stressful situations which, in turn, can result in stress inoculation during illness situations. Resourcefulness may play a useful role in care-getting and marshalling responsive care from both informal and formal providers of support (Path 5).

Religiosity

Religiosity and use of religious coping strategies are salient for coping with life threatening illnesses (Koenig, George, & Siegler, 1988). Intrinsic religiosity may be expressed through faith, prayer and finding meaning in religious values. Patients can draw on such religious values as they encounter illness (Moberg, 2001). Religious participation can also enhance availability of social supports based on caring interactions with church members (Krause, 2002).

Spirituality

Spirituality may be defined as having qualities of inner strength, peace, and harmony (Boswell, Kahana & Dilworth-Anderson, 2006). Respect for patients’ spiritual beliefs has been considered an important component of patient responsive care (Dane, 2004) that contributes to the maintenance of meaningfulness and personhood (Nolan & Crawford, 1997). Both religiosity and spirituality are expected to serve as buffers in the face of stressors of illness, and are proposed to reduce suffering, burden of disability, and psychological distress (Path 4).

2. Proactive Adaptations

Marshalling Support

Marshalling support refers to actions taken by patients to mobilize available social resources (Greene, Jackson, & Neighbors, 1993). Receipt of responsive care is viewed as a function of both social resources available to patients and their propensity to disclose problems and ask for help (Charmaz, 1991). Patients generally marshal support first from informal resources, such as family and friends. The patient’s life course stage is an important determinant of the types of helpers who may be available. Accordingly, children generally turn to parents, whereas adults rely on spouses or significant others, and the elderly often turn to their spouses and adult children for assistance (Pearlin, Pioli, & McLaughlin, 2001). When these efforts to marshal support from family members prove insufficient, patients may turn to health care providers and other formal sources of support (Cantor & Brennan, 2000).

Health Care Consumerism (Advocacy)

Patients may also seek to enhance the quality of their health care through advocacy (Rodwin, 1997). Taking an active role in treatment decision making is an important aspect of maintaining control and influencing medical care when dealing with cancer and other illnesses. The growing literature on health communication emphasizes both the need for information gathering by patients and assertive health communication with formal providers to ensure responsive care (O’Hair, Kreps, & Sparks, 2007). Patients with disabilities need to be particularly assertive and creative in eliciting patient-responsive care (Path 5) (Kahana & Kahana, 2001). Thus, patients in wheelchairs must show assertiveness to ensure that physicians address them rather than their caregivers. Similarly, both young and elderly patients can benefit by asking questions directly to physicians, rather than accepting information relayed via a caregiver.

Planning

Planning ahead is a valuable proactive adaptation, because anticipation of future needs may reduce later problems by taking action (Soerensen & Pinquart, 2000). In taking an active role in cancer treatments, familiarity with clinical trials and making plans for alternative treatments increases patient control and options. Plans formulated prior to getting sick (including obtaining disability and long term care insurance) can improve quality of life when serious illness strikes (Wagner, Austin, & Von Korff, 1996). Patients diagnosed with cancer who may be unable to work during treatment benefit from planning for reentry into the workforce (Frank, 1995). Recently, there has also been advocacy for earlier planning for end of life care (Lynn, 2000). Learning about the options in one’s environment can help patients familiarize themselves with available informal social resources and formal services that promote care-getting (Path 5).

Technology Use

Use of technology can provide important sources of empowerment for patients as they deal with health-related challenges (Sherrod, 2006). Adolescents and young adults are increasingly adept at using the Internet for obtaining health information and socio-emotional support (Zrebiec & Jacobson, 2001). Middle-aged individuals typically acquire computer skills in the workplace and can benefit from transferring these skills to coping with their illness. As new cohorts of older adults experience frailty and their mobility and life space diminish, electronic mail, cell phone use, and health-alert devices can play important roles in marshalling responsive care (Path 5) (Kahana & Kahana, 2007b).

G. Informal Social Resources

1. Availability

Extensiveness of the patient’s social network prior to the illness influences care-getting by creating access to informal support during illness episodes (Sarason & Sarason, 1985). Most patients prefer informal rather than formal sources of support, as they deal with illness adaptive tasks (Moos & Schaefer, 1986). Caregivers living in the same household or nearby are more ready to provide instrumental support (e.g. help with household tasks), but even distant caregivers can help meet patients’ needs (Krause, 2006). Having a confidante offers the opportunity to share concerns and solicit advice about health care issues. However, highly burdened caregivers may be less able to meet the needs of the patient (Wykle, 2005). When patients are hospitalized, having family members close by can be particularly important to enhance comfort and a sense of being cared for. Those without a social network face additional challenges in care-getting when facing a chronic illness alone (Hymovich & Hagopian, 1992).

It has long been recognized that social relationships within the informal network of the patient are affected by family dynamics. Accordingly, social interaction, particularly in the face of the crisis of illness, may become strained and characterized by conflict, particularly where a history of dysfunctional family relationships already exists (Kissane, Bloch, Burns, Patrick, Wallace, & McKenzie, 1994). In a study of women diagnosed with cancer, Bolger, Foster, Vinokur, and Ng (1996) noted that significant others who readily offered support in relation to patients’ physical needs were often withholding of affective support when faced with patients’ emotional distress. Thus, it is important to recognize that successful care-getting may be limited by family conflict and the ability of potential caregivers to assume supportive roles. Availability of caregiver’s support refers to both physical access and emotional availability.

2. Received Social Support

Care-getting is fundamentally linked to instrumental and affective support from family and friends. Such support can facilitate the maintenance of good quality of life, even in the face of critical events and chronic illnesses (Blanchard, Albrecht, & Ruckdeschel, 2000). When patients must deal with a new health diagnosis or treatment, the role of informal support gains importance. As hospitals increasingly discharge patients early, even when they require medical care at home, informal caregivers assume greater responsibilities. Different family members may provide alternative types of support at times of illness. For example, spouse caregivers are more likely to assist with personal tasks and report more hours of care over a longer period of time without reporting feeling burdened (Cantor & Brennan, 2000). Children and adolescents find natural caregivers in their parents. Patients who previously helped others are able to draw on willing caregivers from among friends and neighbors (Midlarsky & Kahana, 2007) (Path 5). Similarly, patients who are helpful to fellow patients in hospital settings are likely to benefit from reciprocal assistance.

Responsiveness to Patients’ Values and Concerns

An important dimension of informal social resources relates to the responsiveness of family and friends to the concerns of the patient. When patients have limited control and are unable to act on their own behalf, they have a strong need to have family members heed their wishes (Otis-Green & Rutland, 2004). Seriously ill patients need family members to be their voice and work toward obtaining medical and nursing care that is consistent with their values and preferences (Cassell, 2005).

H. Formal Social Resources

1. Access to Health Care

Physical proximity to health care providers and the availability of a regular provider facilitates access to health care. As cancer patients often undergo treatment resulting in functional limitations, their access to health care may be restricted by lack of mobility and transportation. Delayed access to outpatient care results in longer hospital stays and poorer health outcomes (Weissman, Stern, Fielding, & Epstein, 1991). During health crises, access also includes the willingness of health care providers to be contacted on short notice and respond to changing care needs of the cancer patients. Nursing professionals can play an important role in enhancing access to both care and information about self-care for cancer patients (Miaskowski, Dodd, West, Schumacher, Paul, Tripathy, et al., 2004).

2. Received Social Support

Informal and formal sources of care generally differ in the types of support provided. Formal health care providers supply mostly specialized instrumental support, while informal sources such as friends and family are more likely to provide emotional support. Nevertheless, during health crises, the caring and affirmation communicated by formal health care providers assumes increasing importance for the maintenance of good quality of life. Informal caregivers also play a continuing instrumental role in arranging and monitoring care. Effective partnerships between informal and formal caregiving systems result in synergies that benefit both caregivers and patients (Fortinsky, 1998).

Responsiveness to Patient Values and Concerns

Patients with cancer often face treatment decisions that will have a long-term impact on their life by affecting fertility or resulting in altered body image (e.g. after mastectomy) (Charmaz, 1991). Sensitivity and responsiveness of health care providers to patient preferences and concerns are beneficial in these situations. It is noteworthy that patients during different life stages and with different illness trajectories differ in preferences for information and involvement in health care decision making (Leydon, Boulton, Moynihan, Jones, Mossman, & Boudioni, et al., 2000). Health care continuity and clinician familiarity with a patient enhances responsiveness to patient preferences. Similarly, proactive articulation of values and preferences by patients also enhances responsiveness of care (Kahana & Kahana, 2001). Care in the final stages of life focuses on understanding psychological needs and providing optimal comfort to the patient.

Demographic Characteristics

Demographic characteristics of patients, such as age, gender, race/ethnicity, income, education, and marital status, impact all model elements (Figure 1). Since discussion of such influences involves a vast literature, we are limited here to providing illustrative examples. Based on the growing recognition of health disparities due to race/ethnicity and income (Geiger, 2006), we focus on illustrating racial and socioeconomic differences in illness-related stress exposure, care-getting, and quality of life during illness. We expect that patients with more limited social resources will experience greater stress exposure and have more limited access to formal care. They may also be more limited in their help seeking behaviors.

Demographic characteristics associated with more limited resources (i.e., older age, female gender, minority race/ethnicity, less education, lower income, and divorced/widowed marital status) increase the likelihood of experiencing both chronic illness and critical life events (Link & Phelan, 1995). Lack of social resources limits patients’ options with regard to care-getting, particularly through reducing access to formal care. Studies have consistently found that lower socioeconomic status and minority status are related to reduced access to medical care (Kelley-Moore & Ferraro, 2004). A burgeoning literature on health care disparities reveals that members of racial minorities, including African-Americans and Hispanics, are diagnosed with cancer at later stages of their illness and often lack access to state of the art health care (Mor, Zinn, Angelelli, Teno, & Miller, 2004).

Availability of informal supports is influenced by demographic factors in complex ways. Members of minority groups have been shown to experience health disparities based on less access to high quality health care, but may have some advantage in obtaining informal care, as more limited social mobility of family members and stronger norms of obligation may result in family members being more available to offer care (Geiger, 2006).

Patients’ attitudes toward getting medical care are also influenced by race and socioeconomic status (SES). Individuals with lower SES and limited education tend to let the doctor decide on treatment options (Scott, Shiell, & King, 1996). Furthermore, members of racial and ethnic minorities are more likely to express preferences for life extending treatment (Leybas-Amedia, Nuno, & Garcia, 2005).

These illustrative examples provide a glimpse into the influence of sociodemographic resources on levels of stress exposure and access to care-related resources. We acknowledge the importance of both life chances and life choices (Elder & Conger, 2000) in our care-getting model. We note that equality in care-getting can be achieved only where all patients, regardless of race, class, or gender, can experience true caring in major illness situations.

CARE-GETTING THROUGH THE LIFE COURSE

The majority of research in the area of social networks and health has portrayed the relationship as static over the life course (Moren-Cross & Lin, 2006). However, the process of care-getting is dynamic, shaped by different adaptive tasks, family relationships, and illness trajectory across the lifespan, including childhood and adulthood (King & Elder, 1997; Moren-Cross & Lin, 2006). In the next portion of our paper we present a brief overview of issues shaping care-getting during different stages of the life course (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Life Course Specific Care-Getting Issues

| Challenges to Care-Getting | Childhood | Adolescence | Young Adulthood | Midlife | Old Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Personal barriers | Trust limited to parents as protectors | Embarrassed to disclose symptoms | Fearful of appearing weak and needy | Conflict between generativity needs and care-getting | Threatened by dependency when asking for help |

| Unskilled in articulating needs | Negotiation skills not fully developed | Help seeking threatens independence | Illness-related loss of self esteem limits help seeking | Unassertive in communicating needs | |

| 2. Social barriers | Wants to limit parental distress | Fears stigma from peers | Job/family responsibilities inhibit care-getting | Job/family responsibilities inhibit care-getting | Patient may also be a caregiver |

| 3. Barriers to getting medical care | Separation from parents during treatment | Only assent required for treatment | Lack of support from partner in dealing with health care system | Lack of support from family in dealing with health care system | Comorbidities interfere with getting responsive cancer care |

| Facilitators of Care-Getting | Skillful parental advocacy and support | Strong peer support | Emotional support from partner | Emotional support from family | Advocacy by family |

| Supportive school environment | e-literacy; self advocacy | e-literacy; self advocacy | e-literacy; self advocacy | Patient-physician-family partnership | |

| Issues of Access/Availability to Formal and Informal Care-Getting | Lack of direct communication with health care providers | Conflict with parents may inhibit medical care-getting | Availability of partner or close friends | Availability of family members friends/neighbors | Availability of spouse/adult child friends/neighbors |

| Older sibling availability | Peer “shield” availability | Parent/work role strain inhibits access | Parent/work role strain inhibits access | Access to physician | |

Childhood

Prior literature regarding children living with cancer has focused mainly on psychological distress of family members and parents providing care to children with cancer (Svavarsdottir, 2005). It is important to understand, however, that children can play a significant role in eliciting responsive care for themselves or someone else. At this stage in life, children’s ability to marshal support for themselves may be limited by absence of resources, and/or constrained by parental attitudes. Given that parents are usually the primary caregivers during this life stage, marshalling support for children with cancer is shaped by responses received from their parents. In a study to evaluate the caregiving demands placed on parents of children with cancer, Svavarsdottir (2005) found that the most difficult and time-consuming activity for parents was providing emotional support.

Recognizing parents’ emotional strain, children with cancer may be apprehensive to marshal additional needed support from their parents. Marshalling support from siblings can serve a useful role for children living with cancer (Kahana, Kahana, Johnson, Hammond, & Kercher, 1994). However, research has shown that the emotional toll on siblings of children with cancer is also taxing (Alderfer, Labay, & Kazak, 2003). Children with cancer must cope with isolation from normal school and social activities. Concern about physical changes distorting their body image has been found to be a prevalent issue among children with cancer (Kameny & Bearisond, 2002). Children’s ability to seek and receive reassurance in these realms is an important influence on their quality of life. One available option for children with cancer is the use of cancer support groups specifically geared for children. These support groups not only give needed emotional support to children suffering with cancer, but they also empower children with needed skills that can enable them to be better proactive care-getters (Wright & Frey, 2007).

Parents of children with cancer must frequently allow doctors and nurses to become the caregivers (Woodgate, 1999). The child’s ability to marshal support from strangers who serve as caregivers is limited, because the child may lack self-efficacy to be assertive in requesting needed care. In the case of a child with cancer, the parent-child communication dyad is typically transformed into a doctor/nurse-parent-child triad, which makes managing communication more difficult (Young, Dixon-Woods, Windridge, & Henry, 2003). Communication with children who are dealing with cancer is particularly important because it builds trust, and in turn that trust affords the child the comfort needed to be more assertive in care-getting. While adults have the ability to act as their own advocates, children in the hospital need an advocate for care-getting (Beuf, 1989). Children’s age and knowledge of their illness will influence their options for self advocacy and of marshalling support. Furthermore, children with cancer who actively seek and gather information can reduce some of their uncertainty (Husain & Moore, 2007). Such advocacy can help decrease children’s sense of isolation related to both school and family life (Wright & Frey, 2007).

Adolescence

Chronic illness in general, and cancer in particular, holds special challenges for adolescents. Since adolescents often have a sense of invincibility, they might deny symptoms and may be embarrassed to seek treatment early (Albritton & Bleyer, 2003). There are unique challenges to the adolescent patient who is threatened with the loss of newly won independence and who is reluctant to return to a dependent role, with parents or caregivers in charge of decision making. Part of the care-getting challenge for the adolescent diagnosed with cancer involves renegotiation of family relationships with parents and siblings.

Care-getting challenges the social development of adolescents, who are eager for acceptance by their peers, and threatens their ability to blend into the peer culture (Abrams, Hazen, & Penson, 2006). However, peers can become significant sources of instrumental and social support for adolescents who are able to self-disclose challenges of their illness. In terms of marshalling formal support from health care providers, adolescents are eager to be involved in decision making, but often lack information about alternative options being considered (Albritton & Bleyer, 2003). Accordingly, effective proactivity as health care consumers is contingent on successful information gathering. The developmental challenges faced by adolescents to move toward greater independence from parents may serve as barriers to their ability to marshal needed instrumental, informational, and emotional support.

Adolescents also face unique challenges in care-getting from physicians, who are not required by law to obtain informed consent for treatment from patients under the age of eighteen. Current guidelines only require assent of adolescents in treatment (Lee, Havens, Sato, Hoffman, & Leuthner, 2006). Consequently, the ability of adolescents to obtain care that is responsive to their values and preferences may be compromised.

Studies have identified mothers as the individuals who are the major sources of social support for adolescent cancer patients. However, along with the closeness in the relationship, efforts in care-getting are often fraught with conflict, particularly in daughter-mother dyads (Marine & Miller, 1998). In addition, poor adaptation of parents, and their inability to cope with the illness of their adolescent child may serve as an important barrier to successful care-getting by these young cancer patients (Frank, Blount, & Brown, 1997).

Among peers, best friends have been cited as particularly valuable in care-getting efforts of adolescent cancer patients. They can serve as “peer shields,” protecting adolescents from social stigma, particularly during the reentry phase of their cancer experience, when they return to school and to their social functions (Larouche & Chin-Peuckert, 2006). With the expansion of online support groups, accessing peer-support groups can serve as a source of empowerment for young cancer patients. Alternatively, some adolescents may distance themselves from those peers with cancer.

Marshalling formal support proactively also involves taking initiative by the young patient in raising questions and concerns to a busy medical staff. Research indicates that nurses are often viewed by young patients as the most approachable health care providers (Ritchie, 2001).

Young Adulthood

Young adulthood is a period in life when important issues about personal and social identity are established within both professional and family roles. Establishment of intimate relationships with a partner represents another developmental task of young adulthood (Erikson, 1980; Levinson, 1978). Issues in marshalling support after cancer diagnosis might be particularly difficult at this stage, when the promise of a fulfilling life has just started to unfold. There has been little research dealing with young adult cancer patients in general, and specifically on care-getting, in this group. As young adults are adjusting to the transition from adolescence to adulthood and to independence, becoming a proactive care-getter is particularly salient, since many of the cancers that occur during young adulthood are curable and the survival rate among this group is higher than in other age groups, including adolescence (Gatta, 2003). Nevertheless, threats to self esteem pose challenges to care-getting, due to the “off time” nature of illness and accompanying sense of loss (Rolland, 1994).

Research on young adult women living with breast cancer indicates that this group encounters more physical and psychosocial distress than do older women confronting this disease (Kroenke, Rosner, Chen, Kawachi, Colditz, & Holmes, 2004). These adverse effects of cancer in young adulthood have been attributed to disruption in self image and sexuality. Disclosure of illness diagnosis necessary for marshalling informal support may also be difficult for young adults, who are likely to fear disruption of social relationships or inability to have children.

Young adults are among major users of the Internet for receiving social support online. The anonymity of online support groups allows for more comfort in discussing potentially embarrassing subjects and allows for marshalling support without revealing visible effects of treatment, such as hair loss due to chemotherapy (White & Dorman, 2001). Indeed, the term “e-patients” describes new cohorts of assertive patients who take an active role in care-getting from the formal health care system (O’Hair, Kreps & Sparks, 2007).

Midlife

Although the importance of adult life stages in the experience of cancer has been acknowledged in conceptual frameworks on cancer survivorship (Rowland, 1989), little research has focused on unique needs and perspectives of cancer patients in mid-life. Studies are largely based on age comparisons involving the young or the old, whereas middle-aged patients are often omitted from such studies (Rose, O’Toole, Dawson, Lawrence, Gurley, & Thomas, et al., 2004). Being afflicted with cancer in midlife represents a major disruption in social roles related to developmental tasks of midlife, generativity (Erickson, 1993), work and family (Charmaz, 1991), and reassessment of identity (Carr, 1997).

Research focusing on age differences in coping with chronic illness in general reveals that middle-aged individuals are more likely to engage in help-seeking coping strategies than are older adults (Felton & Revenson, 1987). Interpersonal rather than self-reliant approaches may be more acceptable to younger cohorts of middle aged patients in dealing with illness. The need for care-getting in midlife may also be viewed as being at odds with the self-image of middle-aged patients as contributing members of society. Thus, parents suffering from cancer must turn from nurturing their children to recognizing their own vulnerability and needing nurture.

Although being a recipient of care may be psychologically difficult to accept, cancer patients at midlife possess many resources that position them well for proactive care-getting. Since many adults in midlife are married, spouses represent available partners for decision making and can be readily involved in caregiving roles. Adults during midlife are at the peak of their income and careers, and have the educational background to play an assertive role with health care providers. This contrasts with the greater dependency of very young and very old patients. Research on age or cohort differences among cancer patients, regarding receiving emotional support from their physicians, suggests that middle-aged patients receive more emotional support from physicians than do their elderly counterparts (Rose, 1993).

Research on midlife and chronic illness, including cancer, has often focused on the gendered nature of the illness experience. Qualitative findings have pointed to women reporting great stress, based on expectations that midlife women should fulfill work and family obligations even while undergoing debilitating treatments. When such patients feel that they do not have a voice in marshalling responsive health care, they feel overwhelmed and alienated (Kralik, 2002).

Old Age

Older adults (age 65 or over) represent a large majority of all new cases of cancer (61%), having 11 times the risk for cancer compared to younger age groups (Feuerstein, 2007). Among unique challenges faced by older adults in obtaining responsive care, barriers in communication have been noted as playing a key role. Older adults often experience sensory losses (difficulties in hearing and vision) and cognitive losses that place them at a disadvantage in expressing assertiveness and initiative in marshalling support (Sparks, 2007). Additionally, social losses (by death or relocation of family and friends) reduce access to informal sources of support in later life (Kahana & Kahana, 2003a). Based on their socialization to respect medical authority, older cancer patients have also been found to express less initiative and assertiveness in their health care encounters with physicians (Kahana, et al., in press). Furthermore, based on the great value placed on self-reliance in the current generation of elders, help seeking in general may be less acceptable to this age group (Tanner, 2001). Even as we focus on disadvantages of late life in terms of access to caregivers and to the health care system, we must also note that the cancer experience appears to be less devastating to older adults than to younger patients. Older adults who are typically retired and have raised their families do not have the same degree of social role interruption, based on living with cancer, as do younger patients, who must deal with interruption of salient family and work related roles.

With new cohorts of older adults seeking to maintain self-efficacy in late life, elders’ options for playing an active role in care-getting may become more prevalent and may come to symbolize successful aging. Elderly persons of the future may develop skills in care-getting based on their midlife experiences as advocates in the course of caregiving to friends and family members (McDonald & Wykle, 2003). In this sense, caregiving and care-getting may be viewed as complementary concepts. In prior caregiving literature, the focus has often been placed on the designated caregiver, based on the diagnosed illness of a family member for whom they are responsible (Kahana & Young, 1990). Yet, in real life, both members of the elderly couple often require care, and caregiving or care-getting are a function of fluctuating health conditions of both partners. Essential elements of caring are located in the relationship between the one caring, and the one being cared for (Noddings, 2003).

CONCLUSION

The proposed model of proactive care-getting represents an innovative perspective by recognizing that frailty and the need for care-getting can coexist, while still retaining agency and initiative. Individuals with chronic and life threatening illness can still exert control over the care they get by proactively marshalling support (Kahana & Kahana, 2003b). Rather than focusing exclusively on caregiving, we believe that people can benefit from actively confronting care-getting issues, including advocacy, to insure that the quality of life is optimized during chronic illness experiences. Our model supports a paradigm shift toward patient empowerment, an area of sociological research that is relatively new and incomplete (Wagner, et al., 2001).

The Care-getting Model we propose allows researchers the opportunity for empirical exploration that can help support or falsify tenets of the theory. Patients with serious illnesses such as cancer may remain active participants in care-getting, or they may disengage and allow formal and informal social systems to define the unfolding of their journey, as they cope with their illness.

Because proactive care-getting has not been explicitly recognized to be a valued patient role, there has been little direct reference to interventions that can support or promote patients’ care-getting efforts. Nevertheless, important strides have been made, particularly in the cancer care community, to offer resources that can empower and facilitate care-getting by cancer patients. The American Cancer Society offers hotlines providing access to volunteer peer counselors 24 hours a day. Accordingly, access is offered to discuss concerns and adaptive tasks faced by cancer patients. Print, audio, and online resources to support groups, focused on specific concerns and/or specific age groups, are also available through numerous patient initiated or institutional sponsors. The “Cancer Survival Toolbox” is a particularly useful audio resource program containing 10 free compact discs addressing communication skills and access to resources for survivors of different ages dealing with diverse common cancers. It is available at cancersurvivortoolbox.org. Access to relevant resources is broadly disseminated through advertising via print and broadcast media by cancer survivor organizations, including The American Cancer Society, The Lance Armstrong Foundation, The National Cancer Institute, The National Coalition for Cancer Survivorship, The Association of Oncology Social Work, and The Oncology Nursing Society. Programs to empower health care consumers to communicate more assertively and to take more initiative as patients have been limited (Epstein & Street, 2007). Nevertheless, the success of training programs for enhancing health literacy and communication competence has been reported (Cegala, Post & McClure, 2002; Tran, Haidet, Street, O’Malley, Martin, & Ashton, 2004).

The proposed proactive care-getting model is aimed to generate research that is needed to support the development of future interventions. Such interventions can enhance the quality of life of those dealing with the stressors associated with chronic illness. Our conceptualization holds the potential for understanding aspects of planning, health care consumerism, and marshalling social support. This will enable patients and their families to be trained to engage in and to help promote patient responsive or patient centered care. This can lead to interventions that empower health care consumers to take initiative and to be assertive as they manage their health care. Patient-focused interventions that foster proactive care-getting can complement educational efforts aimed at sensitizing health care providers to the special needs of patients with serious chronic illnesses such as cancer. Our focus on diverse concerns of patients with chronic illnesses, including spirituality as a resource, and meaningfulness as an outcome, can lead to culturally sensitive and humanistic interventions in the future.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grant RO1=CA098966

References

- Abrams AN, Hazen EP, Penson RT. Psychosocial issues in adolescents with cancer. Cancer Treatment Reviews. 2006;33:622–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2006.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albritton K, Bleyer WA. The management of cancer in the older adolescent. European Journal of Cancer. 2003;39:2584–2599. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderfer MA, Labay LE, Kazak AE. Brief report: Does posttraumatic stress apply to siblings of childhood cancer survivors? Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2003;28(4):281–286. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antonucci TC. Social supports and social relationships. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. 2. Princeton, NJ: Van Nostrand Reinhold; 1990. pp. 94–128. [Google Scholar]

- Beuf AH, editor. Biting off the bracelet: A study of children in hospitals. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Blanchard CG, Albrecht TL, Ruckdeschel J. Patient-family communication with physicians. In: Baider L, Cooper CL, De-Nour AK, editors. Cancer and the family. 2. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2000. pp. 477–495. [Google Scholar]

- Bolger N, Foster M, Vinokur AD, Ng R. Close relationships and adjustment to a life crisis: The case of breast cancer. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1996;70(2):283–294. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.2.283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boswell G, Kahana E, Dilworth-Anderson P. Spirituality and healthy lifestyle behaviors: Stress counter-balancing effects in the health maintenance of older adults. Journal of Religion and Health 2006 [Google Scholar]

- Cantor MH, Brennan M. Social care of the elderly: The effects of ethnicity, class, and culture. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. The fulfillment of career dreams at midlife. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1997;38:331–344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, Scheier MF. Social intelligence and personality: Some unanswered questions and unresolved issues. Advances in Social Cognition. 1989;2:93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Cassell J. Life and death and intensive care. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cegala DJ, Post DM, McClure L. The effects of patient communication skills training on the discourse of older patients during a primary care interview. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2002;49(11):1505–1511. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4911244.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. Good days, bad days: The self in chronic illness and time. Rutgers, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MZ, Musgrave CF, McGuire DB, Strumpf NE, Munsell MF, Mendoza TR, et al. The cancer pain experience of Israeli adults 65 years and older: The influence of pain interference, symptom severity, and knowledge and attitudes on pain and pain control. Support Care Cancer. 2005;13:708–714. doi: 10.1007/s00520-005-0781-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. Personality: Another “hidden factor” is stress research. Psychological Inquiry. 1990;1(1):22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Dane B. Integrating spirituality and religion. In: Berzoff J, Silverman PR, editors. Living with dying: A handbook for end of life health care practitioners. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2004. pp. 424–438. [Google Scholar]

- Dolbeault S, Szporn A, Holland JC. Psycho-oncology: Where have we been? Where are we going? European Journal of Cancer. 1999;35(11):1554–1558. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(99)00190-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder GH, Conger R. Children of the land: Adversity and success in rural America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Empana JP, Dargent-Molina P, Breart G. Effect of hip fracture on mortality in elderly women: The EPIDOS prospective study. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2004;52:685–690. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52203.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein R, Street R. National Cancer Institute: NIH Publication No. 07-6226. Bethesda, MD: 2007. Patient-Centered communication in cancer care: Promoting healing and reducing suffering. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity and the life cycle. New York: Norton; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Childhood and society. New York: Norton; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Facione NC. Perceived risk of breast cancer: Influence of heuristic thinking. Cancer Practice. 2002;10(5):256–262. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-5394.2002.105005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felton BJ, Revenson T. Age differences in coping with chronic illness. Psychology and aging. 1987;2(2):164–170. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.2.2.164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feuerstein M. Handbook of cancer survivorship. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Fortinsky RH. Physician influence on caregivers of dementia patients. Washington, DC: AARP; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Frank A. The Wounded Storyteller. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Frank NC, Blount RL, Brown RT. Attributions, coping, and adjustment in children with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1997;22(4):563–576. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/22.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrickson BL. Cultivating positive emotions to optimize health and well-being. Prevention & Treatment. 2000;3 Retrieved from: http://journals.apa.org/prevention/volume3/toc-mar07-00.html.

- Gatta G. Cancer survival in European adolescents and young adults. European Journal of Cancer. 2003;39(18):2600–2610. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2003.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geiger HJ. Health disparities: What do we know? What do we need to know? What should we do? In: Schulz AJ, Mullings L, editors. Gender, race, class, & health: Intersectional approaches. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2006. pp. 261–288. [Google Scholar]

- George LK. Life-course perspectives on mental health. In: Aneshensel CS, Phelan JC, editors. Handbook of sociology of mental health. Dordrecht, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers; 1999. pp. 565–583. [Google Scholar]

- Giele JZ, Elder GH. Methods of life course research: Qualitative and quantitative approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Gillham J, Reivich K. Cultivating optimism in childhood and adolescence. Annals of the American Academy. 2004;591:146–163. [Google Scholar]

- Greene RL, Jackson JS, Neighbors HW. Mental health and help-seeking behavior. In: Jackson JS, Chatters LM, Taylor RJ, editors. Aging in black America. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1993. pp. 185–200. [Google Scholar]

- Harpham W. After cancer. New York, NY: Harper Collins; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Hewitt M, Greenfield S, Stovall E. From cancer patient to cancer survivor: Lost in transition. Washington, DC: National academies; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Husain M, Moore S. Communication and childhood cancer. In: O’Hair D, Kreps G, Sparks L, editors. The Handbook of communication and cancer care. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 2007. pp. 257–273. [Google Scholar]

- Hymovich DP, Hagopian GA. Chronic illness in children and adults: A psychosocial approach. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Kahana B. Conceptual and empirical advances in understanding aging well through proactive adaptation. In: Bengtson V, editor. Adulthood and aging: Research on continuities and discontinuities. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 1996. pp. 18–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Kahana B. On being a proactive health care consumer: Making an “unresponsive” system work for you. Research in Sociology of Health Care: Changing Consumers and Changing Technology in Health Care and Health Care Delivery. 2001;19:21–44. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Kahana B. Contextualizing successful aging: New directions in age-old search. In: Settersten R Jr, editor. Invitation to the life course: A new look at old age. Amityville, NY: Baywood; 2003a. pp. 225–255. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Kahana B. Patient proactivity enhancing doctor-patient-family communication in cancer prevention and care among the aged. Patient Education and Counseling. 2003b;50(1):67–73. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Kahana B. Health care partnership model of doctor-patient communication in cancer prevention and care among the aged. In: O’Hair D, Kreps G, Sparks L, editors. The handbook of communication and cancer care. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 2007a. pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Kahana B. Technology use, health information, and doctor-patient communication; Presented at the 9thWorld Congress of Semiotics; Helsinki/Imatra, Finland. Jun, 2007b. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Kahana B, Johnson R, Hammond R, Kercher . Developmental challenges and family caregiving: Bridging concepts and research. In: Kahana E, Biegel D, Wykle M, editors. Family caregiving across the lifespan. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 1994. pp. 3–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kahana E, Young R. Clarifying the caregiver paradigm: Challenges for the future. In: Biegel DE, Blum A, editors. Aging and caregiving: Theory, research and practice. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications; 1990. pp. 76–97. [Google Scholar]

- Kameny R, Bearisond D. Cancer narratives of adolescents and young adults: A quantitative and qualitative analysis. Children’s Health Care. 2002;31(2):143–173. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley-Moore J, Ferraro KF. The black/white disability gap: Persistent inequality in later life? Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2004;59B:34–43. doi: 10.1093/geronb/59.1.s34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King V, Elder G. The legacy of grandparenting: Childhood experiences with grandparents and current involvement with grandchildren. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1997;59:848–859. [Google Scholar]

- Kissane DW, Bloch S, Burns WI, Patrick JD, Wallace CS, McKenzie DP. Perceptions of family functioning and cancer. Psycho-Oncology. 1994;3:259–269. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, Blazer DG. Mood disorders and suicide. In: Birren JE, Sloane RB, Cohen GD, editors. Handbook of mental health and aging. 2. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, Inc; 1992. pp. 379–407. [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG, George LK, Siegler IC. The use of religion and other emotion-regulating coping strategies among older adults. The Gerontologist. 1988;28(3):303–10. doi: 10.1093/geront/28.3.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kralik D. The quest for ordinariness: Transition experience by midlife women living with chronic illness. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2002;39(2):146–154. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.02254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Church-based social support and health in old age: Exploring variations by race. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57:S332–S347. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.6.s332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Social relationships in late life. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. 6. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 181–200. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke C, Rosner B, Chen W, Kawachi I, Colditz G, Holmes M. Functional impact of breast cancer by age. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(10):1849–1856. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.04.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larouche SS, Chin-Peuckert L. Changes in body image experienced by adolescents with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 2006;23(4):200–209. doi: 10.1177/1043454206289756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee KJ, Havens PL, Sato TT, Hoffman GM, Leuthner SR. Assent for treatment: Clinician knowledge, attitudes, and practice. Pediatrics. 2006;18(2):723–730. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levinson DJ. The seasons of a man’s life. New York: Knopf; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Leybas-Amedia V, Nuno T, Garcia F. Effect of acculturation and income on Hispanic women’s health. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2005;16:128–141. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2005.0127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leydon G, Boulton M, Moynihan C, Jones A, Mossman J, Boudioni M, et al. Cancer patients’ information needs and information seeking behaviour: In depth interview study. British Medical Journal. 2000;320:909–913. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7239.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan J. Social conditions as fundamental causes of disease. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;35:80–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynn J. Finding the key to reform in end of life care. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2000;19(3):165–167. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(00)00114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marine S, Miller D. Social support, social conflict, and adjustment among adolescents with cancer. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 1998;23(2):121–130. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/23.2.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDonald PE, Wykle ML. Predictors of health-promoting behavior of African-American and white caregivers of impaired elders. Journal of National Black Nurses Association. 2003;14(1):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaskowski C, Dodd M, West C, Schumacher K, Paul SM, Tripathy D, et al. Randomized clinical trial of the effectiveness of self-care intervention to improve cancer pain management. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22:1713–1720. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midlarsky L, Kahana E. Life course perspectives on altruistic health and mental health. In: Post S, editor. Altruism and health: Perspectives from empirical research. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2007. pp. 81–103. [Google Scholar]

- Moberg DO. The reality and centrality of spirituality. In: Moberg DO, editor. Aging and spirituality. New York, NY: The Haworth Pastoral Press; 2001. pp. 3–20. [Google Scholar]

- Moos R, Schaefer J. Life transitions and crises: A conceptual overview. In: Moos RH, editor. Coping with life crisis: An integrated approach. New York, NY: Plenum Press; 1986. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]

- Mor V, Zinn J, Angelelli J, Teno J, Miller S. Driven to tiers: Socioeconomic and racial disparities in the quality of nursing home care. The Milbank Quarterly. 2004;82:227–256. doi: 10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moren-Cross J, Lin N. Social networks and health. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. 6. San Diego, CA: Elsevier; 2006. pp. 111–126. [Google Scholar]

- Ng AV, Alt CA, Gore EM. Fatigue. In: Feuerstein M, editor. Handbook of cancer survivorship. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2007. pp. 133–150. [Google Scholar]

- Noddings N. Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral education. 2. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Nolan MT, Mock V. A conceptual framework for end of life care: A reconsideration of factors influencing the integrity of the human person. Journal of Professional Nursing: Official Journal of the American Association of Colleges of Nursing. 2004;20(6):S351–S360. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolan P, Crawford P. Towards a rhetoric of spirituality in mental health care. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 1997;26:289–294. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1997.1997026289.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hair D, Kreps G, Sparks L. Conceptualizing cancer care and communication. In: O’Hair D, Kreps G, Sparks L, editors. The Handbook of communication and cancer care. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 2007. pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Otis-Green S, Rutland CB. Marginalization at the end of life. In: Berzoff J, Silverman PR, editors. Living with dying: A handbook for end of life health care practitioners. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2004. pp. 462–481. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L. The sociological study of stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1989;30:241–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L, Pioli M, McLaughlin A. Caregiving by adult children: Involvement, role disruption, and health. In: Binstock RH, George LK, editors. Handbook of aging and the social sciences. 5. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2001. pp. 238–253. [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L, Zarit S. Research into informal caregiving: Current perspectives and future directions. In: Zarit SH, Pearlin LI, Schaie KW, editors. Caregiving systems: Informal and formal helpers. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum; 1993. pp. 155–167. [Google Scholar]

- Penrod J, Martin P. Health expectancy, risk factors, and physical functioning. In: Poon LW, Gueldner SH, Sprouse BM, editors. Successful aging and adaptation with chronic diseases. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2003. pp. 104–115. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson C. The future of optimism. American Psychologist. 2000;55(1):44–55. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richey J, Brown J. Cancer, communication, and the social construction of self: Modeling the construction of self in survivorship. In: O’Hair D, Kreps G, Sparks L, editors. The handbook of communication and cancer care. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 2007. pp. 145–164. [Google Scholar]

- Ritchie MA. Sources of emotional support for adolescents with cancer. Association of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology Nurses. 2001;18(3):105–110. doi: 10.1177/104345420101800303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodwin MA. The neglected remedy: Strengthening consumer voice in managed care. The American Prospect. 1997;34(9–10):45–50. [Google Scholar]

- Rolland JS. Families, illness, and disability: An integrative treatment model. New York: Basic Books; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rose J. Interactions between patients and providers: An exploratory study of age differences in emotional support. Journal of Psychosocial Oncology. 1993;11(2):43–67. [Google Scholar]

- Rose JH, O’Toole EE, Dawson NV, Lawrence R, Gurley D, Thomas C, et al. Perspectives, preferences, care practices, and outcomes among older and middle-aged patients with late-stage cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2004;22(24):4907–4917. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.06.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowland JH. Developmental stage and adaptation: Adult model. In: Holland JC, Rowland JH, editors. Handbook of psycho-oncology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 1989. pp. 25–43. [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Sarason BR. Social support: Theory, research, and applications. Boston, MA: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Scheier M, Carver C. Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies. Health Psychology. 1985;4:219–247. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.4.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S, Turner HA. Age, disability, and the sense of mastery. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1998;39(3):169–186. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott A, Schiell A, King M. Is general practitioner decision making associated with patient socio-economic status? Social Science & Medicine. 1996;42(1):35–46. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(95)00063-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seligman MEP. Learned optimism. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Sherrod RA. Nursing research: Improving interest and understanding for the Net Generation. Nurse Educator. 2006;31(2):49–52. doi: 10.1097/00006223-200603000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soerensen S, Pinquart M. Vulnerability and access to resources as predictors of preparation for future care needs in the elderly. Journal of Aging and Health. 2000;12(3):275–300. [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi-Zalud E, Zhong Z, Lynn J, Hamel MB. Elderly persons’ last six months of life: Findings from the hospitalized elderly longitudinal project. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2000;48(5):131–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03122.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparks L. Cancer care and the aging patient: Complexities of age-related communication barriers. In: O’Hair D, Kreps GL, Sparks L, editors. The handbook of communication and cancer care. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 2007. pp. 227–244. [Google Scholar]

- Svavarsdottir EK. Caring for a child with cancer: A longitudinal perspective. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2005;50(2):153–161. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2005.03374.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner D. Sustaining the self in later life: Implications for community-based services. Ageing and Society. 2001;21(3):255–278. [Google Scholar]

- Tran A, Haidet P, Street R, O’Malley K, Martin F, Ashton C. Empowering communication: A community-based intervention for patients. Patient Education & Counseling. 2004;52:113–121. doi: 10.1016/s0738-3991(03)00002-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornton AA, Perez MA. Interpersonal relationships. In: Feuerstein M, editor. Handbook of cancer survivorship. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2007. pp. 191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EH, Austin BT, Davis C, Hindmarsh M, Schaefer J, Bonomi A. Improving chronic illness care: Translating evidence into action. Health Affairs. 2001;20(6):64–78. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner EH, Austin BT, Von Korff M. Organizing care for patients with chronic illness. The Milbank Quarterly. 1996;74(4):511–544. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson J. Caring science as sacred science. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis Company; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman JS, Stern R, Fielding SL, Epstein AM. Delayed access to health care: Risk factors, reasons, and consequences. Annals of Internal Medicine. 1991;114(4):325–331. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-114-4-325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White M, Dorman S. Receiving social support online: implications for health education. Health Education Research. 2001;16(6):693–707. doi: 10.1093/her/16.6.693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolff S. The burden of cancer survivorship: A pandemic of treatment success. In: Feuerstein M, editor. Handbook of cancer survivorship. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2007. pp. 7–18. [Google Scholar]

- Woodgate R. Social support in children with cancer: A review of the literature. Journal of Pediatric Oncology Nursing. 1999;16(4):201–213. doi: 10.1177/104345429901600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright K, Frey L. Communication and support groups for people living with cancer. In: O’Hair D, Kreps G, Sparks L, editors. The handbook of communication and cancer care. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton Press; 2007. pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar]

- Wykle ML. Health and productivity-Challenging the mystique of longevity. In: Wykle ML, Morris DL, Whitehouse PJ, editors. Successful aging through the lifespan: Intergenerational issues in health. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Young B, Dixon-Woods M, Windridge K, Henry D. Managing communication with young people who have a potentially life threatening chronic illness: Qualitative study of patients and parents. British Medical Journal. 2003;326(8):326–305. doi: 10.1136/bmj.326.7384.305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zausniewski JA. Health-seeking resources and adaptive functioning in depressed and nondepressed adults. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing. 1994;8:159–168. doi: 10.1016/0883-9417(94)90049-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zrebiec JF, Jacobson AM. What attracts patients with diabetes to an internet support group? A 21-month longitudinal website study. Diabetic Medicine. 2001;18(2):154–158. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-5491.2001.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]