Abstract

Cardiac SPECT is typically performed clinically with static imaging protocols and visually assessed for perfusion defects based upon the relative intensity of myocardial regions. Dynamic imaging, however, has the potential to provide quantitative measures of flow, possibly improving diagnosis. The objective of this study was to compare the information content of dynamic and static thallium SPECT imaging as measures of myocardial perfusion. Studies were performed in four canines, each with an occlusion placed on the left anterior descending coronary artery. Dynamic SPECT imaging was performed at rest and under adenosine stress, and subsets of the data were summed to provide corresponding static datasets for identical physiologic conditions. Microsphere-derived flow measurements were used as the gold standard. The dynamic data were fit to a two-compartment model to provide regional estimates of wash-in rate parameters. Occluded-to-normal ratios were also calculated for each canine study. The results show comparable correlations with microspheres for both wash-in and static scaled image intensities. The dynamic data provided higher defect contrasts, which were more accurate than the static occluded to normal ratios. Preliminary studies were also performed in two patients and the static and dynamic data compared. These results show that dynamic thallium imaging may provide improved diagnostic information compared to static imaging for myocardial perfusion SPECT studies.

Index Terms: Blood flow, dynamic imaging, single photon emission computed tomography, thallium

I. Introduction

Knowledge of regional cardiac perfusion is essential for the control and management of coronary artery disease. Positron emission tomography (PET) is arguably the best noninvasive modality to evaluate myocardial perfusion. However, PET suffers from poor availability and lack of reimbursement. Single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT), on the other hand, is widely available. Myocardial perfusion studies with SPECT are performed clinically on millions of patients each year.

A static imaging protocol is typically used in clinical cardiac SPECT perfusion studies. Many different SPECT tracers have been investigated for studying perfusion. 201Tl is a widely used tracer in clinical studies for evaluating myocardial perfusion as well as myocardial viability. Static 201Tl SPECT has been shown to correlate well with blood flow in dogs [1] and is a standard procedure for evaluating myocardial perfusion. The static 201Tl images, wherein a single three-dimensional image is obtained, are qualitative in nature but do not provide absolute quantification of myocardial blood flow. To obtain quantitative measures of myocardial blood flows, dynamic imaging has been shown to have promise [2]–[6].

There has been a significant amount of work investigating dynamic SPECT imaging using 99mTc-labeled teboroxime [3]–[6]. Teboroxime has very rapid kinetics, which necessitate very fast temporal sampling that is not feasible on most SPECT systems. Additionally, the underlying cellular mechanisms of teboroxime transport are not fully understood. In this paper, we investigate dynamic SPECT imaging with 201Tl. Thallium-201 is a potassium analog and works in conjunction with the Na-K ATPase pump. It undergoes high transcapillary extraction during the early uptake phase immediately following administration. Moreover, 201Tl has very slow washout kinetics, which suggests that slow dynamic acquisitions with a SPECT camera may be feasible. There is evidence that wash-in rate parameters estimated from dynamic thallium SPECT may provide accurate quantitative measures of myocardial blood flow [2]. The main objectives of this study were:

to acquire and process dynamic 201Tl SPECT images using analysis methods developed by our group [5];

to compare the dynamic SPECT canine studies using 201Tl with summed subsets of dynamic data and micro-sphere derived flows;

to perform preliminary studies in patients to assess the feasibility of dynamic 201Tl imaging in patients.

II. Methods

A. Canine Studies

Six studies were performed in four canines. Each dog was anesthetized and the chest was opened. A catheter for micro-sphere delivery was placed in the left atrial appendage. A snare was placed on the left anterior descending (LAD) coronary artery to give 100% occlusion of blood flow. In two dogs, both rest and adenosine stress protocols were used. Resting studies were done under normal physiological condition, whereas in stress studies a 6-min infusion of the vasodilator adenosine was used.

The imaging was done on a three-head gamma camera (Marconi; PRISM 3000XP) equipped with fan beam collimators. Each dog was placed on the table in the right lateral decubitus position. First, transmission imaging was performed with a 99mTc line source. Dynamic SPECT imaging was then initiated, and a bolus injection of 3–4 mCi 201Tl was administered intravenously approximately 5–10 s after the start of imaging. For each study, 90 full sets of projection images (64 bins × 64 slices × 120 angles were obtained in two stages with a pixel size of 0.712 cm. The first stage consisted of 60 frames of 10 s each, and the second stage with 30 frames of 60 s each. There was a dead time of approximately 0.3 s between each time frame while the gantry motion was reversed. Radioactive microspheres (113Sn or 103Ru) were injected directly into the left atrium simultaneously with the 201Tl administration. An arterial reference sample was drawn from the femoral artery at the rate of 6.5 mL/min for 2 min, beginning just prior to the microsphere injection.

At the end of the study, the animal was sacrificed and the heart was excised. The heart was sectioned into six slices approximately 10 mm thick, and each slice was further divided into eight equal sectors. Each of the tissue samples was weighed and placed into a vial for well counting. These data were further processed to obtain myocardial blood flows for each region [6], and they were used as the gold standard for blood flows.

The imaging data were processed in two ways in order to evaluate and compare dynamic imaging with compartmental modeling to conventional static imaging. First, static images were obtained by summing up 20 min of the dynamic data beginning 10 min after injection. This summing scheme was chosen to provide static datasets representative of what would be obtained from conventional static 201Tl studies. Reconstruction was done using six iterations of the ordered subsets expectation maximization (OS-EM) [8] algorithm. Compensation for attenuation and depth-dependent detector response was also performed by modeling these effects in the projector and backprojector of the iterative algorithm. Following reconstruction, the static images were reoriented into short-axis slices (1.4 cm thick), and four symmetric regions of interest (ROIs) were drawn on each slice [9]. The microsphere data were registered visually to the short-axis slices from the static images.

The dynamic dataset was also reconstructed with OS-EM and compensated for attenuation and detector response similar to the static dataset. Time activity curves were obtained by gathering the ROI data for all time frames. The blood input function was estimated from the image data using an ROI drawn over the left ventricle blood pool. The time activity curves were fit to the two-compartment model shown in Fig. 1 using RFIT [10]. However, the fitting routine failed to converge for many of the regions, likely due to the very high levels of statistical noise in the earliest time frames. In order to reduce the noise in those time frames, we investigated different methods of summing the original time frames to produce dynamic datasets with slower temporal sampling. Computer simulations were performed in order to determine the effects that these different sampling schedules would have upon the bias in the kinetic rate parameter estimates. The results of these simulations are shown in Table I. Summing the original time frames to obtain the sampling schedule listed in the first row of Table I was found to enable RFIT to converge in all the cases. The simulations indicate that the bias introduced into the wash-in parameter estimates is negligible for this sampling schedule; hence this schedule was used to process all of the canine studies.

Fig. 1.

Two-compartment model used to represent the kinetics of 201Tl distribution in the myocardium.

TABLE I.

Results Of The Computer Simulations Showing The Bias In Kinetic Rate Parameter Estimates For Various Sampling Schedules

| Sampling schedule | % bias in k21 | % bias in k12 | % bias in fv |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 at 20sec + 10 at 30sec + 10 at 60sec + 10 at 120sec | +0.2 | −5 | +1 |

| 30 at 20sec + 10 at 60sec + 10 at 120sec | +6 | +2 | +1 |

| 6 at 20sec + 12 at 40sec + 10 at 60sec + 10 at 120sec | +16 | +11 | −11 |

The dynamic data with the revised sampling schedule were processed again, and the wash-in rate parameter (k21), obtained from the fitting routine, was used as a measure of blood flow. Since 201Tl has very slow washout kinetics, the washout rate parameter (k12) can be estimated accurately only if a long image acquisition duration is used [11]. Hence for the studies performed, k12 was not analyzed. Twenty regions were considered for each of the six studies. The data obtained from each canine study were pooled, and the wash-in parameters and the static intensities were compared to the gold-standard micro-sphere flows. A total of 120 data points were used to compare the static and dynamic data with the microsphere flows. Since the static intensities only provide relative flow information and are not quantitative, interstudy scaling needed to be applied before the data could be pooled. Thus, the static data were scaled such that the sum of the static 201Tl intensities for each study matched the sum of the microsphere flow values. The wash-in rate parameters were not scaled, as these data are inherently quantitative.

In order to quantify defect contrasts, regions were drawn on the area fed by the occluded artery and a distant normal region. The size of these regions ranged between 3–9 cm3 for the occluded regions and 6–10 cm3 for the normal regions. The image data were then reprocessed using these regions, and occluded-to-normal (O/N) ratios were calculated for both the static data and for the wash-in rate parameter estimates. The corresponding occluded and normal regions of the microsphere data were used as the gold standard.

B. Patient Studies

Dynamic 201Tl SPECT studies were performed at stress in two patients. Projection data were acquired on a three-head camera equipped with parallel hole collimators (Marconi; IRIX). The patient was placed on the camera bed, and adenosine was infused at a rate of 0.14 mL/kg/min for 6 min. Approximately 3 mCi 201Tl was administered intravenously using a 30-s infusion. The projection images were acquired with 128 × 128 image matrices using 0.466-cm pixels, and 120 projection angles were acquired over 360° for each time frame. The data were obtained in two stages: the first stage with 60 frames of 11 s each and the second stage with 60 frames of 30 s each. The revised sampling schedule chosen for the patient studies was as follows: six frames of 22 s, six frames of 88 s, five frames of 120 s, and eight frames of 150 s each. This was different than the schedule used with canine studies, in part because 201Tl was infused over 30 s in patient studies.

The processing of the dynamic and static data was similar to that in the canine studies. However, in addition to attenuation and detector response compensation, effective source scatter estimation (ESSE) model-based scatter compensation was also performed [12], [13]. For each study, the effect of scatter compensation was evaluated by comparing the dynamic wash-in parameters obtained with and without scatter compensation. Four ROIs were drawn on each of eight 10-mm-thick short-axis slices of the static data set for analysis. As in the canine studies, scaling of the static data was performed when the data were pooled. Since no microsphere measurements were obtained, the static intensities for each study were scaled relative to the wash-in parameters in two ways. First, they were scaled such that for each study, the sum of the wash-in rate parameters was equal to the sum of the static data. In the second approach, scaling was done such that the maximum of the wash-in parameters in each study was equal to the maximum of the static 201Tl data for the respective study.

III. Results

A. Canine Studies

The summed short-axis image data for one of the canine studies with an occlusion is shown in Fig. 2. A perfusion defect can be seen in the more apical slices, which corresponds well with the area fed by the occluded artery. Example time activity curves for both the original and revised sampling schemes are shown in Fig. 3. Substantial noise can be seen in the curves, especially for the original sampling scheme with short time frames. Recall from the methods section that the fitting routine failed to converge in many cases, and that the sampling scheme was revised to overcome this problem (Table I). The revised sampling scheme was used for all further dynamic data analysis of the canine studies.

Fig. 2.

Summed short-axis slices for one of the canine studies. The perfusion defect can be seen in the anteroseptal wall of the more apical slices.

Fig. 3.

Time activity curves for a canine study (a) with original dynamic temporal schedule and (b) after summing frames (15 at 20 s + 10 at 30 s + 10 at 60 s + 10 at 120 s).

For each individual study, the correlation with microsphere data for the static and dynamic methods is listed in Table II. High correlations were observed between the static and dynamic wash-in data. The correlation plots for the pooled data for the static and dynamic case are shown in Fig. 4. The wash-ins were related to the microsphere flows by y = 0.65x + 0.16 (r = 0.73), while the scaled static data were related to the microsphere flows by y = 0.84x + 0.15 (r = 0.86)

TABLE II.

Individual Correlations For The Canine Studies

| Canine study | Wash-ins vs. spheres | Static vs. spheres | Wash-ins vs. static |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (stress) | 0.75 | 0.79 | 0.92 |

| 2 (rest) | 0.70 | 0.54 | 0.89 |

| 3 (stress) | 0.68 | 0.77 | 0.92 |

| 4 (rest) | 0.61 | 0.68 | 0.86 |

| 5 (stress) | 0.65 | 0.75 | 0.87 |

| 6 (stress) | 0.64 | 0.79 | 0.95 |

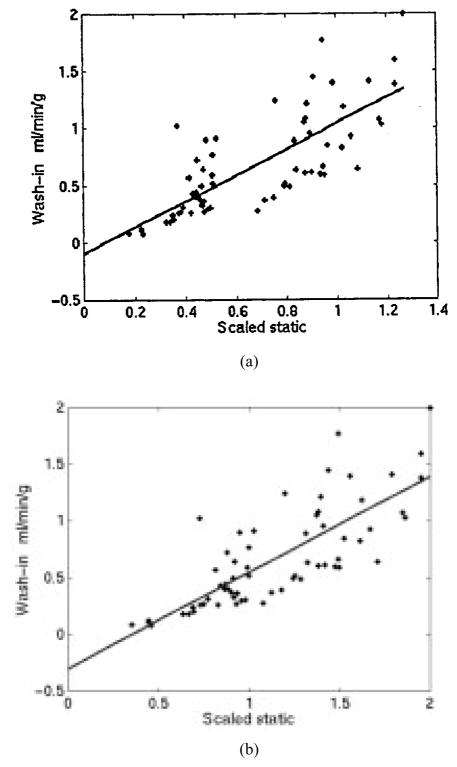

Fig. 4.

Scatter plots for the pooled canine data: (a) wash-in rate parameters versus microsphere-derived flow values and (b) scaled static data versus microsphere flows.

Polar plots for each canine study using the static data, wash-in parameters, and corresponding microsphere data are shown in Fig. 5, and the occluded-to-normal ratios for each study are listed in Table III. The wash-in data gave higher defect contrasts than did the static data, and the dynamic results matched the gold-standard microsphere contrasts more closely in five of the six studies. However, the wash-in rate parameters overestimated the size of the hypoperfused region in some studies (columns 2 and 5 in Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Polar plots for the six canine studies. First row shows the polar plots for the flow data using microspheres, second row shows the polar plots for the wash-in parameter data, and third row shows the polar plots for the static data. The first two columns are polar plots for rest studies, and the next four columns are those of stress studies. The studies from left to right are arranged as study 2, study 4, study 1, study 3, study 5, and study 6. The study numbers correspond to those mentioned in Tables II and III.

TABLE III.

Occluded-To-Normal Ratios For The Canine Studies

| Canine study | Spheres O/N | Wash-ins O/N | Static O/N |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 (stress) | 0.15 | 0.32 | 0.53 |

| 2 (rest) | 0.46 | 0.42 | 0.75 |

| 3 (stress) | 0.28 | 0.14 | 0.43 |

| 4 (rest) | 0.08 | 0.16 | 0.31 |

| 5 (stress) | 0.10 | 0.16 | 0.23 |

| 6 (stress) | 0.11 | 0.17 | 0.11 |

B. Patient Studies

Fig. 6 shows scatter plots of the wash-in versus the scaled summed static intensity data. The total number of regions in each study considered was 32. The wash-ins were related to the scaled static data by y = 1.13x − 0.09 (r = 0.77) when the summed data were scaled such that the sum of the static intensities equaled the sum of the wash-in parameters for each study, as in Fig. 6(a). The correlation fit was y = 0.84x − 0.29 (r = 0.78) when the static data were scaled such that the maximum value of the static data equaled the maximum value of the wash-in parameter for each study, as in Fig. 6(b). The correlation coefficients were comparable for both cases and were not overly sensitive to the scaling method used. A comparison of the static intensities with and without scatter compensation showed that scatter compensation changed the static intensity values by approximately 20% and wash-in parameters by approximately 10%. Although dynamic data are affected less by scatter, scatter correction is likely still required to obtain accurate quantitative measures for dynamic studies.

Fig. 6.

Scatter plots of the wash-in parameters versus scaled static for the pooled patient data. In (a), the static data were scaled so that the sum of the wash-in parameters for each study equaled the sum of the static intensities. In (b), the static data were scaled such that the maximum of the wash-in parameter for each study was equal to the maximum of the static data for that study.

IV. Discussion

The dynamic and the static summed thallium data both have been compared with respect to the microsphere data as the gold standard. The slope of less than one in the case of the wash-in versus spheres may be due to several causes. One is the fact that 201Tl uptake is from the plasma and not the whole blood. However, the method considered here assumes input from the whole blood. This results in overestimation of the volume from which the tracer is being extracted. Hence, the wash-in parameters that reflect the fraction of tracer extracted from a given volume of blood are underestimated. The effect of compensating for other degrading factors such as partial volume effects, hematocrit, and extraction fraction discussed in [1] were not considered here. Corrections for these factors may help provide absolute quantitative measures of myocardial blood flow.

It was necessary to perform interstudy scaling in order to pool the static data sets. However, such scaling has a tendency to produce high correlations because the scaling itself introduces some degree of correlation in the data. The uptake of 201Tl may differ between studies, and better ways to scale the data have yet to be developed.

Our results showed that dynamic imaging provided more accurate contrast between occluded and normal regions than did static imaging. This may be in part because the static data were more sensitive to scatter effects than were the dynamic data (see the patient studies results). Since perfusion studies aim at differentiating between normal and hypoperfused myocardium, it is important to get accurate contrast between the ischemic and normal regions. However, dynamic data overestimated the extent of ischemic regions in some cases.

Static cardiac SPECT studies depict regional tracer uptake. The analysis is typically based upon subjective image interpretation. This approach often provides good information for patient management in case of coronary artery disease. The dynamic approach used here may help in obtaining an objective analysis, which may translate into more accurate diagnosis. This method might be especially useful in cases where patients are suffering from three-vessel disease, whereby there is an overall global reduction of myocardial perfusion.

Static cardiac SPECT imaging protocols are less complicated, and the total processing time required is less than that required by dynamic cardiac SPECT imaging with 201Tl. Our studies required a total imaging time of about 40 min for dynamic imaging protocols. During static imaging, however, the initial 15 min are skipped to allow the clearance of the tracer from the blood pool, and imaging is performed for the next 20 min. Due to the relatively long imaging time for dynamic cardiac SPECT imaging, some artifacts might occur due to patient motion. However, studies would be required to optimize the total imaging time required for dynamic cardiac perfusion SPECT with 201Tl.

The biodistribution and long half-life of 201Tl limits the allowable dose to 3–4 mCi in humans. This is a major drawback for dynamic SPECT studies because it results in low counts and high noise, which in turn can cause the fitting routine to fail to converge. To circumvent this problem, longer sampling intervals may be used. The temporal sampling protocol obtained by summing dynamic data from the scanner to fewer frames gave reasonable fits to the two-compartment model. However, more studies are needed to investigate the optimal sampling protocol for different thallium infusions and the clinical potential of dynamic 201Tl cardiac SPECT.

V. Conclusion

Dynamic 201Tl SPECT imaging provides myocardial blood flow information that is comparable in many ways to static 201Tl SPECT. With the application of appropriate corrections, dynamic 201Tl SPECT can likely provide absolute quantitative flow information. Dynamic 201Tl imaging also has the advantage of providing defect contrast that matches more closely to the gold standard microsphere flows than does static thallium but may sometimes overestimate the size of ischemic regions.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank S. McJames for assistance in obtaining the canine data and H. Elsamaloty, MD, for assistance in obtaining the patient data.

This work was supported by NIH under Grant R01 HL50663.

Footnotes

Publisher Item Identifier S 0018-9499(01)05100-0.

Contributor Information

Harshali S. Khare, Email: khare@eng.utah.edu, Department of Bioengineering, University of Utah, UT 84112 USA.

Edward V. R. DiBella, Email: ed@doug.med.utah.edu, Department of Radiology, University of Utah, UT 84112 USA.

Dan J. Kadrmas, Email: kadrmas@doug.med.utah.edu, Department of Radiology, University of Utah, UT 84112 USA.

Paul E. Christian, Email: paul@doug.med.utah.edu, Department of Radiology, University of Utah, UT 84112 USA

Grant T. Gullberg, Email: grant@doug.med.utah.edu, Department of Radiology, University of Utah, UT 84112 USA.

References

- 1.Meleca MJ, McGoron AJ, Gerson MC, Millard RW, Gabel M, Biniakiewicz D, Roszell NJ, Walsh RA. Flow versus uptake comparisons of thallium-201 with technetium-99m perfusion tracers in a canine model of myocardial ischemia. J Nucl Med. 1997:1847–1856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Iida H, Eberl S. Quantitative assessment of regional myocardial blood flow with thallium-201 and SPECT. J Nucl Card. 1998;5:313–331. doi: 10.1016/s1071-3581(98)90133-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gullberg GT, Huesman RH, Ross SG, DiBella EVR, Zeng GL, Reutter BW, Christian PE, Foresti SA. Nuclear Cardiology. 2. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; Dynamic cardiac single-photon emission computed tomography; pp. 137–187. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith AM, Gullberg GT, Christian PE, Datz FL. Kinetic modeling of teboroxime using dynamic SPECT imaging of a canine model. J Nucl Med. 1994;35:484–495. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiBella EVR, Ross SG, Kadrmas DJ, Khare HS, Christian PE, McJames S, Gullberg GT. Compartmental modeling of tech-netium-99m-labeled teboroxime with dynamic SPECT: comparison to static Tl-201 in a canine model. Inves Rad. 2001;36(3):178–185. doi: 10.1097/00004424-200103000-00007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kadrmas DJ, DiBella EVR, Khare HS, Christian PE, Gullberg GT. Static versus dynamic teboroxime myocardial perfusion SPECT in canines. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 1999;46(3):1112–1117. doi: 10.1109/23.856556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heymann MA, Payne BD, Hoffman JIE, Rudolph AM. Blood flow measurements with radionuclide-labeled particles. Prog Cardiovasc Dis. 1977;20:55–79. doi: 10.1016/s0033-0620(77)80005-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hudson HM, Larkin RS. Accelerated image reconstruction using ordered subsets of projection data. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 1994;13(4):601–609. doi: 10.1109/42.363108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DiBella EVR, Gullberg GT, Barclay AB, Eisner RL. Automated region selection for analysis of dynamic cardiac SPECT data. IEEE Trans Nucl Sci. 1997;44:1355–1361. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huesman RH, Knittel BL, Mazoyer BM, Coxon PG, Salmeron EM, Klien GL, Reutter BW, Budinger TF. Notes on RFIT: A Program for Fitting Compartment Models to Regions of Interest Dynamic Emission Tomography Data. Berkeley, CA: Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lau CH, Eberl S, Feng D, Iida H, Lun PK, Siu WC, Tamura Y, Bautovich GJ, Ono Y. Optimized acquisition time and image sampling for dynamic SPECT of Tl-201. IEEE Trans Med Imag. 1998;17(3):334–343. doi: 10.1109/42.712123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frey EC, Tsui BMW. A new method for modeling spatially variant object dependent scatter response function in SPECT. in IEEE Nucl Sci Symp Conf Rec. 1996;2:1082–1086. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kadrmas DJ, Frey EC, Karimi SS, Tsui BMW. Fast implementations of iterative reconstruction based scatter compensation in fully 3D SPECT image reconstruction. Phys Med Biol. 1998;43(4):857–873. doi: 10.1088/0031-9155/43/4/014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]