Abstract

Preinvasive bronchial lesions defined as dysplasia and carcinoma in situ (CIS) have been considered as precursors of squamous cell carcinoma of the lung. The risk and rate of progression of preinvasive lesions to invasive squamous cell carcinoma as well as the mechanism of progression or regression are incompletely understood. While the evidence for the multistage, stepwise progression model is weak with relatively few documented lesions that progress through various grades of dysplasia to CIS and then to invasive carcinoma, the concept of field carcinogenesis is strongly supported. The presence of high-grade dysplasia or CIS is a risk marker for lung cancer both in the central airways and peripheral lung. Genetic alterations such as loss of heterozygosity in chromosome 3p or chromosomal aneusomy as well as host factors such as the inflammatory load and levels of anti-inflammatory proteins in the lung influence the progression or regression of preinvasive lesions. CIS is different than severe dysplasia at the molecular level and has different clinical outcome. Molecular analysis of dysplastic lesions that progress to CIS or invasive cancer and rare lesions that progress rapidly from hyperplasia or metaplasia to CIS or invasive cancer will shed light on the key molecular determinants driving development to an invasive phenotype versus those associated with tobacco smoke damage.

Keywords: Preinvasive lesions, Natural history, Lung cancer

1 Introduction

Lung cancer is the most common cause of cancer deaths worldwide [1, 2]. Less than 16% of patients with lung cancer patients survive 5 years or more [2], owing to late diagnosis and a paucity of effective therapies. In contrast to the poor survival of patients with advanced disease, the survival of those with stage 0 (carcinoma in situ, CIS) or stage 1A disease (tumor ≤2 cm without metastatic spread) has excellent prognosis with 5-year survival >70% [3–5].

In contrast to the peripheral airways and lung parenchyma where the majority of adenocarcinomas arise, squamous cell carcinomas usually arise in the central airways (first five generations of bronchi). Changes in the bronchial epithelium in the central airways are readily accessible to bronchoscopic biopsy under local anesthesia and conscious sedation. The development of autofluorescence bronchoscopy that makes use of blue/violet light to induce tissue fluorescence provides a highly sensitive method to localize preinvasive lesions (moderate/severe dysplasia and carcinoma in situ) in the central airways for biopsy confirmation [6–8]. A better understanding of the make-up and natural history of preinvasive lesions will lead to identification of molecular targets and pathways for early detection and chemopreventive intervention [9]. It will also assist in clinical decision regarding management of these lesions. Development of centrally located squamous cell carcinoma and peripherally located adenocarcinoma proceeds through different pathways [10]. In this review, we will focus on preinvasive lesions in the squamous cell carcinoma development pathway because recent advances in bronchoscopic imaging methods make it possible to study these lesions in vivo [8, 11]. The recent information on the natural history of these lesions and the factors that predict progression of these lesions to invasive squamous cell carcinoma will be reviewed.

2 Squamous carcinogenesis

Squamous cell carcinoma is thought to develop through a stepwise process where the epithelium changes from normal to hyperplasia, metaplasia, mild, moderate, and severe dysplasia and then carcinoma in situ [12–15]. The recent histological classification by the World Health Organization includes squamous dysplasia and CIS as a main morphological form of preinvasive lung lesions [16]. In mild dysplasia, there is disarray in the lower third of the epithelium and mild cytological atypia. Mitoses are absent or rare. Moderate dysplasia is associated with disarray in the lower two thirds of epithelium and more significant cytological atypia. Mitotic figures are confined to the lower third. In severe dysplasia, the disarray extends into the upper third of the epithelium but does not reach the surface. Mitoses are confined to the lower two third. CIS is associated with extension of the disarray to the epithelial surface with malignant cytological features and mitotic figures present through the full thickness. Atypical or malignant cytological features are characterized by variations in nuclear size, shape, and staining properties such as hyperchromatism, multiplicity of nucleoli, irregularities of nuclear membrane, coarsening of chromatin distribution, and discordance of maturation between nucleus and cytoplasm (dyskaryosis). In a subset of squamous dysplasia, there is budding in the subepithelial tissues that result in papillary protrusions of the epithelium. This has been termed angiogenic squamous dysplasia [17].

There is considerable interobserver variation in the classification of preinvasive lesions [18, 19]. Comparing the histopathology grades scored by two experienced pulmonary pathologists with quantitative nuclear morphometry showed that although the objective nuclear morphometry index was significantly different between invasive carcinoma and CIS as well as between CIS and various grades of dysplasia by visual examination, there was no significant difference between moderate and mild dysplasia or between mild dysplasia and metaplasia [20]. The study illustrates the uncertainty in classification of the intermediate grades by visual examination even by highly experienced pulmonary pathologists. The same study also showed a better correlation between allelic losses in several chromosomal regions with nuclear morphometry than with histopathology [20]. The limitation of conventional histopathology classification in terms of predicting the malignancy potential of preinvasive lesions will be further discussed below.

The stepwise progression model of squamous cell carcinogenesis is based on several lines of evidence in animal models [21] and in humans [12–14, 21–26]. Serial sputum cytology examinations in uranium miners and in smokers showed that invasive lung cancer develops through a series of stages from mild, moderate, and severe atypia, carcinoma in situ, and then invasive cancer [22, 23]. However, sputum cells can come from different parts of the tracheobronchial tree. Progression of sputum atypia to cancer may reflect field cancerization rather than progression from the same lesion. The concept of stepwise progression of preinvasive lesions to invasive carcinoma was recently challenged [27].

3 Prevalence of squamous preinvasive bronchial lesions

The prevalence of preinvasive lesions has been studied in vivo using autofluorescence bronchoscopies in heavy smokers with and without lung cancer. In the largest study involving 511 volunteer smokers 40 to 74 years of age (mean age 56 years) who had smoked for at least 20 pack-years (number of packs of cigarettes smoked per day × number of years of smoking), the prevalence of mild, moderate, or severe dysplasia or CIS was 44%, 13%, 6%, and 1.6%, respectively [28, 29]. Similar results were found in autofluorescence bronchoscopy studies conducted around the same period of time in the 1990s [30, 31]. The significant findings in the volunteer smoker studies are (a) women had a lower prevalence of moderate/severe dysplasia and CIS (14% versus 31%) compared with men, (b) women had fewer of these high-grade preinvasive lesions, and (c) the prevalence of preinvasive lesions did not change substantially for more than 10 years after smoking cessation [28, 29]. The prevalence of preinvasive lesions appears to have decreased recently probably reflecting the worldwide trend of a change in the proportion of squamous cell carcinoma versus adenocarcinoma. Among 1,581 smokers with a similar demographics as our previous studies [28, 29], the prevalence of moderate or severe dysplasia or CIS has become 9%, 1.9%, and 0.8%, respectively, a decade later (Lam et al., unpublished data). Fewer high-grade preinvasive lesions were also observed in more recent multicenter autofluorescence bronchoscopy studies [32–34].

4 Longitudinal studies of preinvasive lesions

In an attempt to clarify the natural history of preinvasive lesions, longitudinal studies using serial autofluorescence bronchoscopy and biopsy were performed in patients with dysplasia or CIS [35–41].

With rare exceptions, these studies either had a small number of subjects (≤50) and/or a short duration (≤3 years) of follow-up [42]. A significant proportion of the subjects were patients with previous lung or head and neck cancer. Some of the studies combined severe dysplasia with CIS [43] making it difficult to determine the natural history of these lesions separately. The study by Satoh et al. illustrates the importance of long-term follow-up [44]. In a patient with mild dysplasia, the pathology of the follow-up biopsies fluctuates between squamous metaplasia to different grades of dysplasia before development of an invasive carcinoma 6 years later [44].

Overall, 59% of the lesions with severe dysplasia regressed spontaneously [27, 36–41, 45] while 41% persisted or progressed to CIS or invasive cancer. The progression rate of CIS to invasive cancer is difficult to evaluate as all except one center [43] treated patients with CIS at the time of diagnosis or when the lesion did not resolve within 3 months. Overall, only 13% of the CIS lesions regressed spontaneously without treatment while the majority (87%) progressed to invasive cancer, recurred despite endobronchial therapy, or persisted [27, 35–39]. Over 50% of patients with CIS were found to progress to invasive cancer within 30 months [35, 37, 46].

In a study where patients with severe dysplasia or CIS were not treated until development of invasive cancer, 16 patients had seven severe dysplasia and 29 CIS [43]. Among the 18 lesions with severe dysplasia/CIS that were evaluable without the influence of treatment to the lesion or to a synchronous lesion in the same area, five patients with six CIS progressed to invasive cancer within 15 months. Three of these five patients had progressive disease despite radical radiotherapy or photodynamic therapy [43]. Since the majority of CIS lesions do not resolve spontaneously and when these lesions were allowed to progress to invasive cancer, they can become incurable by local therapy, treatment is preferable instead of observation with repeated bronchoscopies and biopsies.

In contrast to CIS or severe dysplasia, with the exception of the study by Breuer et al. [27], the spontaneous regression rate is higher and the progression rate is lower for lesions with mild/moderate dysplasia. For example, in the study by George et al. [43], none of the lesions with mild or moderate dysplasia progressed to CIS or invasive cancer during the period of follow-up of 12 to 85 months (median 23 months). Hoshino et al. reported only one of the 88 (1.1%) lesions with mild or moderate dysplasia progressed to invasive carcinoma [40]. The study by Breuer et al. [27] found the rate of progression to CIS or invasive cancer from metaplasia to be 9% which is the same as the progression rate of mild/moderate dysplasia. Progression of metaplasia to CIS or invasive cancer occurred within 4 to 7 months in three of the four lesions studied [27]. Occasional progression of hyperplasia or metaplasia to CIS/invasive cancer within a relatively short time has also been reported by other investigators [37]. This led to the concept of a nonstepwise development of squamous cell carcinoma. Alternatively, the intermediate lesions are not always detectable by periodic bronchoscopy and biopsy because of their rapid progression. It should be noted that autofluorescence bronchoscopy devices used in many of the longitudinal studies to localize preinvasive lesions were optimized to detect lesions that are moderate dysplasia or worse [8]. Very few control biopsies were performed from areas with normal or slightly abnormal fluorescence. Lesions with abnormal fluorescence but a benign pathology have been shown to have more frequent DNA alterations compared to those with normal fluorescence [47]. The combined effect of identifying lesions with more genetic alterations and fewer biopsies probably led to an overestimation of the malignancy potential of areas of hyperplasia, metaplasia, or mild dysplasia.

5 British Columbia Lung Health Study

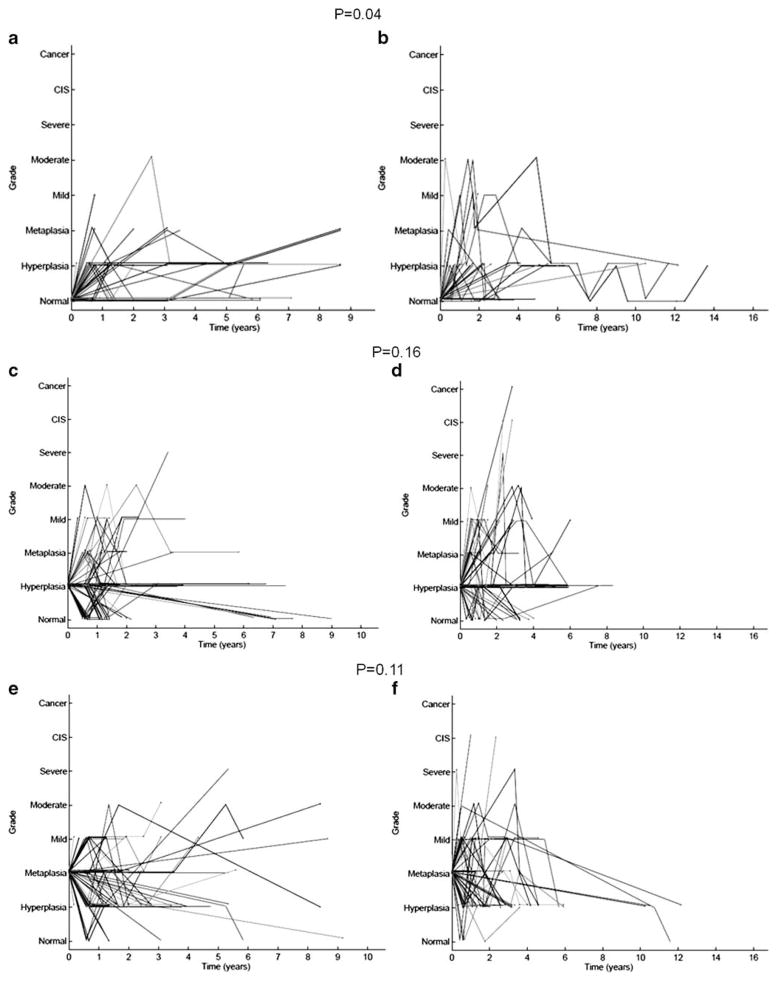

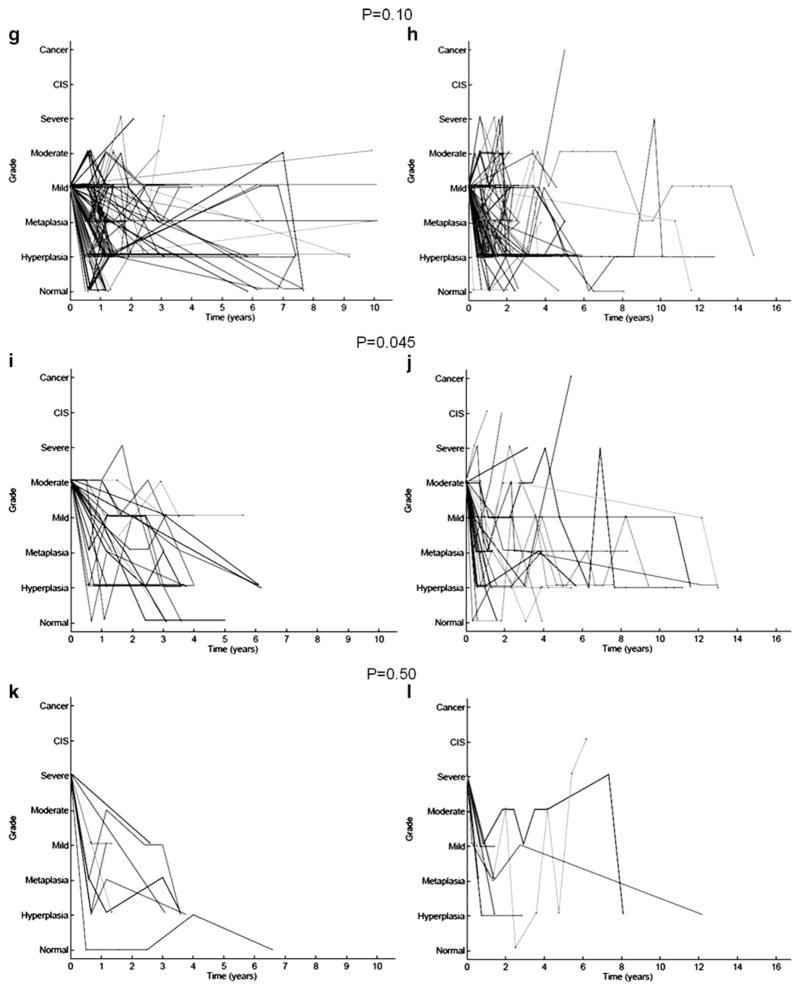

As part of several chemoprevention trials sponsored by National Cancer Institute, 2,154 heavy volunteer smokers above 45 years of age with ≥20 pack-years smoking history without previous cancer in the upper aerodigestive tract were screened by autofluorescence bronchoscopy prior to enrollment onto a chemoprevention trial [48–51]. Repeat bronchoscopy and biopsy of the same sites was performed in 3 to 6 months for those with severe or moderate dysplasia, respectively. Those with CIS were treated with electrocautery ablation or cryotherapy. Seven hundred fifty-four subjects had two or more bronchoscopies. All subjects were followed up in person or through the Cancer Registry. One hundred one subjects were found to have lung cancer after a mean follow-up of 9.2 years (range 1.7 to 20.9 years). A case-control study was performed by matching the cancer and noncancer subjects by age, gender, smoking history, and ethnicity (Table 1). The pattern of progression of various histopathology grades of the bronchial biopsies obtained in the first (baseline) bronchoscopy was compared between the two groups (Fig. 1). For biopsies that were normal, hyperplasia, metaplasia, mild dysplasia, or moderate dysplasia, progression was defined by a change in the pathology by two or more grades (e.g., mild dysplasia to at least severe dysplasia). For severe dysplasia, progression was defined as a change by one grade higher or more (e.g., severe dysplasia to CIS or invasive cancer). The progression rates are higher in the cancer group versus the cancer-free group (Fig. 1; Table 2). The difference reached statistical significance for lesions that were normal or moderate dysplasia at baseline (P=0.04 and 0.045, respectively; one-tailed Fisher exact test). Progression to CIS/invasive cancer in the same site where the initial biopsy showed severe dysplasia was 5.6% and 4.9% for moderate dysplasia. In contrast, the progression rate for metaplasia or mild dysplasia and normal or hyperplasia was 0.8% and 0.9%, respectively. As discussed above, the progression rates of lesions that were normal, hyperplasia, metaplasia, or mild dysplasia were probably falsely high as only one or two control biopsies were taken from areas with normal autofluorescence. Although some lesions appear to progress from hyperplasia/metaplasia to CIS/invasive cancer within 2 years in a fashion similar to that observed by Breuer et al. [27] which is much shorter than the traditional thinking of 10 to 20 years, the progression rate appears to correlate with the severity of the pathological grade in general.

Table 1.

Case-control study of smokers who did or did not develop lung cancer

| No lung cancer | Lung cancer | |

|---|---|---|

| No. of subjects | 101 | 101 |

| Men/women | 59:42 | 59:42 |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 61±7 | 61±8 |

| Ethnicity White/Asian | 98:3 | 98:3 |

| Current/former smokers | 57:44 | 57:44 |

| Pack-years (mean ± SD) | 47±16 | 57±25 |

| Smoking duration (years; mean ± SD) | 41±9 | 40±8 |

| Years quit (former smokers; mean ± SD) | 11±7 | 10±7 |

| Duration of follow-up (years, mean ± SD) | 9.8±3.9 | 9.2±3.9 |

| No. of biopsies | 1,759 | 2,051 |

| Development of | ||

| Squamous cell carcinoma | 33 | |

| Adenocarcinoma | 42 | |

| Other cell types | 26 | |

Fig. 1.

Outcome of lesions that were normal, hyperplasia, metaplasia, mild dysplasia, moderate dysplasia, or severe dysplasia at baseline. Subjects free of lung cancer on follow-up for each histology grade are shown in a, c, e, g, i, and k, and those who developed CIS or invasive cancer in the same site or a distant site are shown in b, d, f, h, j, and l. The progression rates are higher in the cancer group and reach statistical significance for lesions that were normal or moderate dysplasia at baseline (P=0.04 and 0.045, respectively; 2 by 2 comparison, one-tailed Fisher exact test)

Table 2.

Progression rates according to histopathology grade

| Cancer group (%) | Noncancer group (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 22 | 4 | 0.04 |

| Hyperplasia | 18 | 10 | 0.16 |

| Metaplasia | 15 | 9 | 0.11 |

| Mild dysplasia | 6 | 2 | 0.10 |

| Moderate dysplasia | 24 | 4 | 0.045 |

| Severe dysplasia | 11 | 0 | 0.50 |

For biopsies that were normal, hyperplasia, metaplasia, mild dysplasia, or moderate dysplasia, progression was defined by a change in the pathology by two or more grades (e.g., mild dysplasia to at least severe dysplasia). For severe dysplasia, progression was defined as a change by one grade or more (e.g., severe dysplasia to CIS or invasive cancer)

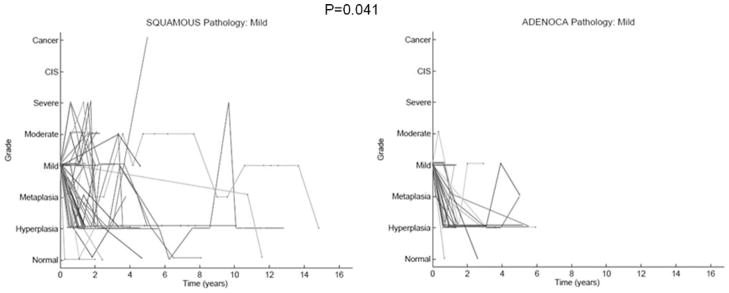

The second observation from the BC Lung Health Study is that a significantly higher progression rate occurred in those who developed squamous cell carcinoma compared with those who developed adenocarcinoma. An example of this is shown in Fig. 2. The progression rate of mild dysplasia was 30.9% for those who developed squamous cell carcinoma versus 3.3% in those who developed adenocarcinoma (P=0.041). The underlying mechanism has not been identified yet. The third important finding from this study is that there are more cancers developed from a separate site in the same individual than progression from the initially biopsied site. This is in agreement with previous studies [43, 45]. Thus, the presence of dysplasia/CIS is a risk marker for lung cancer developing elsewhere in the lung.

Fig. 2.

Outcome of lesions with mild dysplasia in subjects who developed squamous cell carcinoma versus those who developed adenocarcinoma. A significantly higher progression rate was observed in those who developed squamous cell carcinoma (P=0.041; P=0.002 for lesions that progressed to moderate dysplasia or worse)

Taken together, the results of this and other studies suggest that bronchial preinvasive lesions progress to invasive squamous carcinoma in a stepwise fashion although some lesions appear to progress rapidly from hyperplasia or metaplasia. The risk of progression to CIS or invasive cancer is higher for severe dysplasia than for metaplasia or mild dysplasia. The majority of CIS progresses to invasive carcinoma. High-grade dysplasia and CIS are markers of lung cancer development for the entire epithelium at risk. Close follow-up with autofluorescence bronchoscopy and radiological imaging should be considered in patients with these preinvasive lesions.

6 Genetic alterations in preinvasive bronchial lesions

Lung cancer development is characterized by sequential accumulation of epigenetic and genetic alterations in the bronchial epithelial cells [15]. In general, mutations follow a sequence, with allelic losses at chromosomes 3p (3p21, 3p14, 3p22–24, and 3p12), 9p21 (p16INK4a), and 8p21–23 occurring relatively early, losses and inactivation of the 13q14 (RB) and 17q13 (TP53) genes are intermediate, and losses at 5q are late events [10, 15, 52–54]. The losses at 3p are progressive, and advanced lesions and tumors often have lost most of the chromosomal arm or the entire arm, while early lesions have more focal lesions [54]. Abnormal gene methylation is also a frequent event in squamous carcinogenesis [55–57]. For example, there is an increasing frequency of methylation of p16INK4a during disease progression from hyperplasia (17%) to squamous metaplasia (24%) to CIS and invasive carcinoma (50–75%) [56].

These studies indicate that tobacco smoke exposure results in widespread changes in the bronchial tree. Because not all preinvasive lesions develop into invasive tumors, it is important to identify the molecular determinants driving to an invasive phenotype versus those associated with tobacco smoke damage.

In a recent study, 37 patients with 31 CIS and 23 lesions with severe dysplasia were followed up by repeated autofluorescence bronchoscopy and biopsy for up to 12 years [38, 39]. Loss of heterozygosity (LOH) of chromosome 3p was found to be significantly more frequent in CIS compared to severe dysplasia. All CIS lesions that progressed to invasive cancer and 91% of CIS lesions that were resistant to treatment had 3p LOH. In four of the 31 CIS lesions (13%) that regressed spontaneously, only 12% had 3p LOH [39]. In a study by Jonsson and coworkers using a four-color fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) probe set encompassing the chromosome 6 centromere, 5p15.2, 7p12 (EGFR), and 8q24 (v-myc), the proportion of subjects with chromosomal aneusomy was found to increase from moderate dysplasia (22.2%) to severe dysplasia (41.7%) and CIS lesions (75%)[58]. The odds of the presence of chromosomal aneusomy in preinvasive lesions were 4.5 times greater in those with invasive lung cancer in an adjacent site or at a distant site (different lobe). Using two additional FISH probes (TP63 and CEP3) in the same specimen set, the sensitivity and specificity of predicting lung cancer development were 82% and 58%, respectively, using four probes (TP63, CEP3, CEP6, MYC) [59]. Whether LOH or chromosomal aneusomy in preinvasive lesions predicts the subsequent development of invasive lung cancer will require a prospective longitudinal study. More specific markers are also needed to improve the accuracy.

The significance of preinvasive lesions in lung cancer development has also been characterized by immunohistochemistry. Aberrant expression of proteins playing key roles in cell cycle control, apoptosis, and DNA repair such as p53, Ki-67, cyclin D1, cyclin E, Bax, Bcl2, phosphor-Akt, p65/RELA, and cIAP-2 have been investigated. Overexpression of p53 (especially suprabasal staining), cyclin D1/cyclin E, and Ki-67 were detected by immunohistochemistry in bronchial dysplasia, increasing in frequency with their histology grade [60–63]. The acquisition of anti-apoptotic signals is critical for the survival of cancer cells. Bronchial epithelial protein levels of the phosphorylated (active) form of AKT kinase and the caspase inhibitor cIAP-2 were found to be increased in more advanced grades of bronchial IEN lesions than in normal bronchial epithelium [64]. Additionally, the percentage of biopsies with nuclear localization of p65/RELA in epithelial cells increases with advancing pathology grade, suggesting that NF-κB transcriptional activity is induced more frequently in advanced IEN lesions [64].

7 Factors which predict lung cancer development

Telomerase expression in nonmalignant epithelium in high-risk patients with treated lung cancer is associated with an increased subsequent development of second bronchial malignancies [65]. Recent data on longitudinal observation, reported by Hoshino et al., showed that high telomerase activity, increased Ki-67 labeling index, and p53 positivity in dysplasia tend to remain as dysplasia and might have the potential to progress to squamous cell carcinoma [40]. Host factors can also influence progression or regression of preinvasive lesions. High plasma levels of C-reactive protein predict progression of bronchial dysplasia [66]. Surfactant protein D, a large multimeric, calcium-dependent collagenous glycoprotein secreted by type II pneumocytes is an important regulator of innate immunity, inflammation, and oxidative stress. Decreased level of SPD in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid was found to correlate with progression of bronchial dysplasia [67]. Higher levels of another anti-inflammatory protein, CC10, secreted by bronchiolar Clara cells, were found to correlate with regression of bronchial dysplasia and improvement in sputum cytometry [68]. Thus, the inflammatory load in the local environment and anti-inflammatory proteins may determine progression or regression of preneoplastic lesions in addition to genetic and epigenetic alterations.

8 Conclusion

Among bronchial preinvasive lesions, CIS is a strong predictor of progression to invasive squamous cell carcinoma. CIS is different than severe dysplasia at the molecular level and has different clinical outcome. The spontaneous regression rate of dysplasia is significantly higher than CIS (>50% versus ~13%) even for high-grade dysplasia. The addition of nuclear morphometry or molecular analysis to histopathologic grading allows more accurate classification of preinvasive lesions and better identification of lesions that are biologically more aggressive. Host factors such as the inflammatory load and anti-inflammatory proteins can influence the progression or regression of preinvasive lesions. More specific biomarkers are needed to improve the accuracy of predicting which dysplastic lesion will progress to carcinoma. While the evidence for stepwise progression model is relatively weak, the concept of field carcinogenesis is strongly supported. The presence of high-grade dysplasia or CIS is a risk marker for lung cancer both in the central airways and the peripheral lung. Close follow-up with bronchoscopy and radiological imaging are indicated in patients with these lesions.

9 Key unanswered questions

The key molecular determinants driving development of preinvasive bronchial lesions to an invasive phenotype versus those associated with tobacco smoke damage have yet to be defined. Molecular analysis of rare lesions that progress rapidly from hyperplasia or metaplasia to CIS or invasive cancer as well as dysplasias that progress to CIS or invasive cancer will shed light on this very important issue.

Contributor Information

Taichiro Ishizumi, Email: tishizumi@hotmail.co.jp, Department of Thoracic Surgery, Tokyo Medical University, Tokyo, Japan.

Annette McWilliams, Email: amcwilli@bccancer.bc.ca, Department of Integrative Oncology, British Columbia Cancer Agency, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Calum MacAulay, Email: cmacaula@bccrc.ca, Department of Integrative Oncology, British Columbia Cancer Agency, Vancouver, BC, Canada.

Adi Gazdar, Email: adi.gazdar@utshouthwestern.edu, Hamon Center for Therapeutic Oncology & Department of Pathology, UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, TX, USA.

Stephen Lam, Email: slam@bccancer.bc.ca, Department of Integrative Oncology, British Columbia Cancer Agency, Vancouver, BC, Canada. Department of Integrative Oncology, British Columbia Cancer Research Center, 675 West 10 Avenue, Vancouver, BC V5Z 1L3, Canada.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P. Global cancer statistics, 2002. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2005;55:74–108. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.2.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2009;59:225–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nakamura H, Kawasaki N, Hagiwara M, Ogata A, Saito M, Konaka C, et al. Early hilar lung cancer—risk for multiple lung cancers and clinical outcome. Lung Cancer. 2001;33:51–57. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(00)00241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kennedy TC, McWilliams A, Edell E, Sutedja T, Downie G, Yung R, et al. Bronchial intraepithelial neoplasia/early central airways lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (2nd edition) Chest. 2007;132:221S–233S. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rami-Porta R, Ball D, Crowley J, Girous DJ, Jett J, Travis WD, et al. The IASLC lung cancer staging project: Proposals for the revision of the T descriptors in the forthcoming (seventh) edition of the TNM classification of lung cancer. J Thorac Oncol. 2007;2:593–602. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31807a2f81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lam S, MacAulay C, Hung J, LeRiche J, Profio AE, Palcic B. Detection of dysplasia and carcinoma in situ with a lung imaging fluorescence endoscope device. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1993;105:1035–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee P, van den Berg R, Lam S, et al. Color fluorescence ratio for detection of bronchial dysplasia and carcinoma in situ. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15(14):4700–4705. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lam S. Detection of preneoplastic lesions. In: Roth JA, Cox JD, Hong WK, editors. Lung cancer. 3. Malden: Blackwell Science; 2008. pp. 99–110. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kelloff GJ, Lippman SM, Dannenberg A, Sigman CC, Pearce HL, Reid BJ, et al. Progress in chemo-prevention drug development: the promise of molecular biomarkers for prevention of intraepithelial neoplasia and cancer—a plan to move forward. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12(12):3661–3697. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wistuba II, Gazdar AF. Lung cancer preneoplasia. Annu Rev Pathol Mech Dis. 2006;1:331–348. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam S, Standish B, Baldwin C, McWilliams A, leRiche J, Gazdar A, et al. In vivo optical coherence tomography imaging of preinvasive bronchial lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:2006–2011. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saccomanno G. Carcinoma in-situ of the lung: Its development, detection, and treatment. Semin Respir Med. 1982;4(2):156–160. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Auerbach O, Stout AP, Hammond EC, Garfinkel L. Changes in bronchial epithelium in relation to cigarette smoking and in relation to lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 1961;265:253–267. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196108102650601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Auerbach O, Saccomanno G, Kuschner M, Brown RD, Garfinkel L. Histologic findings in the tracheobronchial tree of uranium miners and non-miners with lung cancer. Cancer. 1978;42:483–489. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197808)42:2<483::aid-cncr2820420216>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hirsch FR, Franklin WA, Gazdar AF, Bunn PA., Jr Early detection of lung cancer: Clinical perspectives of recent advances in biology and radiology. Clin Cancer Res. 2001;7:5–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, Harris CC. Pathology and genetics: tumors of the lung, pleura, thymus and heart. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. Lyon: IARC; 2004. pp. 9–124. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keith R, Miller Y, Gemmill R, Drabkin H, Dempsey E, Kennedy T, et al. Angiogenic squamous dysplasia in bronchi of individuals at high risk for lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1616–1625. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Venmans BJ, van der Linden HC, Elbers HR, van Boxem TJ, Smit EF, Postmus PE, et al. Observer variability in histologic reporting of bronchial biopsy specimens. J Bronchol. 2000;7:210–214. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nicholson AG, Perry LJ, Cury OM, Jackson P, McCormick CM, Corrin B, et al. Reproducibility of the WHO/IASLC grading system for pre-invasive squamous lesions of the bronchus: a study of inter-observer and intra-observer variation. Histopathology. 2001;38:202–208. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.2001.01078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guillaud M, leRiche J, Daw C, Korbelik J, Coldman A, Wistuba II, et al. Nuclear morphometry as a biomarker for bronchial intraepithelial neoplasia: Correlation with genetic damage and cancer development. Cytometry Part A. 2005;63A(1):34–40. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nasiell M, Auer G, Kato H. Cytological studies in man and animals on the development of bronchogenic carcinoma. In: McDowell EM, editor. Lung carcinomas. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1987. pp. 207–242. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saccomanno G, Archer VE, Auerbach O, Saunders RP, Brennan LM. Development of carcinoma of the lung as reflected in exfoliated cells. Cancer. 1974;33:256–270. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(197401)33:1<256::aid-cncr2820330139>3.0.co;2-g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frost JK, Ball WC, Jr, Levin ML, Tockman MS, Erozan YS, Gupta PK, et al. Sputum cytopathology: Use and potential in monitoring the workplace environment by screening for biological effects of exposure. J Occup Med. 1986;28:692–703. doi: 10.1097/00043764-198608000-00031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Risse EKJ, Vooijs GP, van’t Hof MA. Diagnostic significance of “severe dysplasia” in sputum cytology. Acta Cytologica. 1988;32:629–634. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nasiell M. Metaplasia and atypical metaplasia in the bronchial epithelium: A histopathologic and cytopathologic study. Acta Cytologica. 1966;10:421–427. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Band PR, Feldstein M, Saccomanno G. Reversibility of bronchial marked atypia. Implication for chemoprevention. Cancer Detection and Prevention. 1986;9:157–160. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Breuer RH, Pasic A, Smit EF, van Vliet E, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Risse EJ, et al. The natural course of preneoplastic lesions in bronchial epithelium. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:537–543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lam S, LeRiche JC, Zheng Y, Coldman A, MacAulay C, Hawk E, et al. Sex-related differences in bronchial epithelial changes associated with tobacco smoking. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999;91(8):691–696. doi: 10.1093/jnci/91.8.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lam S, MacAulay C, leRiche J, Palcic B. Detection and localization of early lung cancer by fluorescence bronchoscopy. Cancer. 2000;89(11 Suppl):2468–2473. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20001201)89:11+<2468::aid-cncr25>3.3.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lam S, Kennedy T, Unger M, Miller YE, Gelmont D, Rusch V, et al. Localization of bronchial intraepithelial neoplastic lesions by fluorescence bronchoscopy. Chest. 1998;113(3):696–702. doi: 10.1378/chest.113.3.696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirsch FR, Prindiville SA, Miller YE, Franklin WA, Dempsey EC, Murphy JR, et al. Fluorescence versus white-light bronchoscopy for detection of preneoplastic lesions: A randomized study. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93(18):1385–1391. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.18.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Edell E, Lam S, Pass H, Miller YE, Sutedja T, Kennedy T, et al. Detection and localization of intraepithelial neoplasia and invasive carcinoma using fluorescence-reflectance bronchoscopy: An international, multi-center clinical trial. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4(1):49–54. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181914506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Häussinger K, Becker H, Stanzel F, Kreuzer A, Schmidt B, Strausz J, et al. Autofluorescence bronchoscopy with white light bronchoscopy compared with white light bronchoscopy alone for the detection of precancerous lesions: A European randomized controlled multicentre trial. Thorax. 2005;60(6):496–503. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.041475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ernst A, Simoff P, Mathur P, Yung R, Beamis J. D-Light autofluorescence in the detection of premalignant airway changes; a multicenter trial. J Bronchol. 2005;12:133–138. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Venmans B, van Boxem A, Smit E, Postmus P, Sutedja T. Outcome of bronchial carcinoma in-situ. Chest. 2000;117:1572–1576. doi: 10.1378/chest.117.6.1572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moro-Sibilot D, Fievet F, Jeanmart M, Lantuejoul S, Arbib F, Laverribre MH, et al. Clinical prognostic indicators of high-grade pre-invasive bronchial lesions. Eur Respirology Journal. 2004;24:24–29. doi: 10.1183/09031936.04.00065303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bota S, Auliac JB, Paris C, Metayer J, Sesboue R, Nouvet G, et al. Follow-up of bronchial precancerous lesions and carcinoma in situ using fluorescence endoscopy. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2001;164(9):1688–1693. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.9.2012147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salaun M, Sesboue R, Moreno-Swire S, Metayer J, Bota S, Bourguignon J, et al. Molecular predictive factors for progression of high-grade preinvasive bronchial lesions. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2008;177:880–886. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200704-598OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Salaun M, Bota S, Thiberville L. Long-term follow-up of severe dysplasia and carcinoma in-situ of the bronchus. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:1187–1188. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181b28f44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hoshino H, Shibuya K, Chiyo M, Iyoda A, Yoshida S, Sekine Y, et al. Biological features of bronchial squamous dysplasia followed up by autofluorescence bronchoscopy. Lung Cancer. 2004;46:187–196. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pasic A, van Vliet E, Breur RH, Risse EJ, Snijders PJ, Postmus PE, et al. Smoking behavior does not influence the natural course of pre-invasive lesions in bronchial mucosa. Lung Cancer. 2004;45:153–154. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Banerjee AK. Preinvasive lesions of the bronchus. J Thorac Oncol. 2009;4:545–551. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e31819667bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.George P, Banerjee A, Read C, O’Sullivan C, Falzon M, Pezzella F, et al. Surveillance for the detection of early lung cancer in patients with bronchial dysplasia. Thorax. 2007;62:43–50. doi: 10.1136/thx.2005.052191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Satoh Y, Ishikawa y, Nakagawa K, Hirano T, Tsuchiya E. A follow-up study of progression from dysplasia to squamous cell carcinoma with immunohistochemical examination of p53 protein overexpression in the bronchi of ex-chromate workers. British Journal of Cancer. 1997;75:678–683. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1997.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jeanmart M, Lantuejoul S, Fievet F, Moro D, Sturm N, Brambilla C, et al. Value of immunohistochemical markers in preinvasive bronchial lesions in risk assessment of lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:2195–2203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thieberville L, Payne P, Metayer J, Vielkinds J, LeRiche J, Palcic B, et al. Molecular follow-up of a pre-invasive bronchial lesion treated by a 13-cis-retinoic acid. Human Pathology. 1997;28:108–110. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(97)90289-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Helfritzsch H, Junker K, Bartel M, Scheele J. Differentiation of positive autofluorescence bronchoscopy findings by comparative genomic hybridization. Oncol Rep. 2002;9(4):697–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lam S, MacAulay C, leRiche JC, Dyachkova Y, Coldman A, Guillaud M, et al. A randomized phase IIb trial of anethole dithiolethione in smokers with bronchial dysplasia. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(13):1001–1009. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.13.1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lam S, Xu XC, Parker-Klein H, LeRiche JC, MacAulay C, Guillaud M, et al. Surrogate endpoint biomarker analysis in a retinol chemoprevention trial in current and former smokers with bronchial dysplasia. Int J Oncol. 2003;23:1607–1613. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lam S, leRiche JC, McWilliams A, MacAulay C, Dyachkova Y, Szabo E, et al. A randomized phase IIb trial of pulmicort turbuhaler (budesonide) in persons with dysplasia of the bronchial epithelium. Clinical Cancer Research. 2004;10:6502–6511. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-0686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lam S, McWilliams A, Leriche J, MacAulay C, Wattenburg L, Szabo E. A phase I study of myo-inositol for lung cancer chemoprevention. Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention. 2006;15(8):1526–1531. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-06-0128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wistuba II, Lam S, Behrens C, Virmani AK, Fong KM, LeRiche J, et al. Molecular damage in the bronchial epithelium of current and former smokers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1366–1373. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.18.1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wistuba II, Behrens C, Milchgrub S, Bryant D, Hung J, Minna JD, et al. Sequential molecular abnormalities are involved in the multistage development of squamous cell lung carcinoma. Oncogene. 1999;18:643–650. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wistuba II, Behrens C, Virmani Ak, Mele G, Milchgrub S, Girard L, et al. High resolution chromosome 3p allelotyping of human lung cancer and preneoplastic/preinvasive bronchial epithelium reveals multiple, discontinuous sites of 3p allele loss and three regions of frequent breakpoints. Cancer Research. 2000;60:1949–1960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Belinsky SA, Palmisano WA, Gilliland FD, Crooks LA, Divine KK, Winters SA, et al. Aberrant promoter methylation in bronchial epithelium and sputum from current and former smokers. Cancer Research. 2002;62:2370–2377. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lamy A, Sesboue R, Bourguignon J, Dautreaux B, Metayer J, Frebourg T, et al. Aberrant methylation of the CDKN2a/p16INK4a gene promoter region in preinvasive bronchial lesions: A prospective study in high-risk patients without invasive cancer. International Journal of Cancer. 2002;100:189–193. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zöchbauer-Müller S, Lam S, Toyooka S, et al. Aberrant methylation of multiple genes in the upper aerodigestive tract epithelium of heavy smokers. International Journal of Cancer. 2003;107:612–616. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jonsson S, Varella-Garcia M, Miller Y, Wolf HJ, Byers T, Braudrick S, et al. Chromosomal aneusomy in bronchial high grade lesions is associated with invasive lung cancer. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2008;177:342–347. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200708-1142OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Massion P, Zou Y, Uner H, Kiatsimkul P, Wolf HJ, Baron AE, et al. Recurrent genomic gains in preinvasive lesions as a biomarker of risk for lung cancer. PLoS ONE. 2009;4(6):e5611. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Breuer R, Snijders P, Sutedja T, vd Linden H, Risse E, Meijer C, et al. Suprabasal p53 immunostaining in premalignant endobronchial lesions in combination with histology is associated with bronchial cancer. Lung Cancer. 2003;40:165–172. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Brambilla E, Gazzeri S, Lantuejoul S, Coll JL, Moro D, Negoescu A, et al. p53 mutant immunophenotype and deregulation of p53 transcription pathway (Bcl2, Bax, and Waf1) in precursor bronchial lesions of lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 1998;4:1609–1618. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brambilla E, Gazzeri S, Moro D, Lantuejoul S, Veyrene S, Brambilla C. Alterations of RB pathway (RB-p16INKA4-cyclin D1) in pre-invasive bronchial lesions. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:243–250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lee JJ, Liu D, Lee JS, Kurie JM, Khuri FR, Ibarguen H, et al. Long-term impact of smoking on lung epithelial proliferation in current and former smokers. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2001;93:1081–1088. doi: 10.1093/jnci/93.14.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tichelaar JW, Zhang Y, leRiche JC, Biddinger PW, Lam S, Anderson MW. Increased staining for phosphor-Akt, p65/RELA and cIAP-2 in pre-neoplastic human bronchial biopsies. BMC Cancer. 2005;5:155. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-5-155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Miyazu Y, Miyazawa T, Hiyama K, Kurimoto N, Iwamoto Y, Matsuura H, et al. Telomerase expression in noncancerous bronchial epithelia is a possible marker of early development of lung cancer. Cancer Research. 2005;65:9623–9627. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-0976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sin DD, Man SF, McWilliams A, Lam S. Progression of airway dysplasia and C-reactive protein in smokers at high risk of lung cancer. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 2006;173:535–539. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200508-1305OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sin D, Man S, McWilliams A, Lam S. Surfactant protein D and bronchial dysplasia in smokers at high risk of lung cancer. Chest. 2008;134(3):582–588. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chen J, Lam S, Pilon A, McWilliams A, Macaulay C, Szabo E. Higher levels of the anti-inflammatory protein CC10 are associated with improvement in bronchial dysplasia and sputum cytometric assessment in individuals at high risk for lung cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14(5):1590–1597. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]