Abstract

Purpose

This study tested the effects of a theory-based middle-school HIV, STI, and pregnancy prevention program, It’s Your Game: Keep it Real (IYG), in delaying sexual behavior. We hypothesized that the IYG intervention would decrease the number of adolescents who initiated sexual activity by the 9th grade compared to those in the comparison schools.

Methods

The target population was English-speaking middle schoolers from a large urban predominantly African American and Hispanic school district in Southeast Texas. Ten middle schools were randomly assigned either to receive the intervention or to the comparison condition. Seventh-grade students were recruited and followed through 9th grade. The IYG intervention comprises 12 seventh-grade and 12 eighth-grade lessons that integrate group-based classroom activities with computer-based instruction and personal journaling. Ninth-grade follow-up surveys were completed by 907 students (92% of the defined cohort). The primary hypothesis tested was that the intervention would decrease the number of adolescents who initiated sexual activity by the 9th grade compared to those in the comparison schools.

Results

Almost one-third (29.9%, n=509) of those in the comparison condition initiated sex by 9th grade compared to almost one-quarter (23.4%, n=308) of those in the intervention condition. After adjusting for covariates, students in the comparison condition were 1.29 times more likely to initiate sex by the 9th grade than those in the intervention condition.

Conclusions

A theory-driven multi-component, curriculum-based intervention can delay sexual initiation up to 24 months; can have impact on specific types of sexual behavior such as initiation of oral and anal sex; and may be especially effective with females. Future research must explore the generalizabilty of these results.

INTRODUCTION

The US has made little progress in the last three decades in protecting its young people against teen pregnancies and HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) [1–3]. Youth are becoming sexually experienced early (10% of 6th graders, age 11) [4], and the proportion increases steadily through high school: more than two-thirds of high school seniors have had sex [5]. Moreover, almost 40% of US teens who are sexually active reported not using a condom during their last intercourse [5].

Evidence suggests that HIV is disproportionately concentrated among young people under the age of 25 and among African-American and Hispanic populations [1, 2, 6, 7], and yet primary prevention efforts still fall short of what is needed to curtail this epidemic. Programs have been developed for these populations. However, more impactful primary prevention programs targeting sexual behaviors at earlier ages are needed.

In Kirby’s recent review (2007) [8], only two curriculum-based sex education programs were found to have positive effects among middle-school students [9, 10], and no studies examined whether interventions had impact on the prevalence of oral or anal sex, particularly high-risk behaviors for STIs [11, 12]. The present study tested the effects of an HIV, STI, and pregnancy prevention program, It’s Your Game: Keep it Real (IYG), on sexual behavior among urban, low-income middle-school youth. The primary hypothesis tested was that the IYG intervention would decrease the number of adolescents who initiated sexual activity by the 9th grade relative to those in the comparison schools.

METHODS

Study Design

IYG was evaluated using a randomized controlled trial design conducted in ten Texas urban middle schools serving a low-income, urban population. The study was approved by the University of Texas institutional review board and the school district’s Office of Research and Accountability. The researchers and school district worked together to identify 13 representative middle schools in 7 feeder patterns, across the school district, that might participate. One was ineligible due to its small student population (<500); 12 were asked in Spring of 2004 to participate in the study; 2 declined to participate. The remaining 10 middle schools were randomly assigned to intervention or comparison using a multi-attribute randomization protocol, taking into account the size and racial/ethnic composition of the student body (African American and Hispanic) and the geographic location of the school [13]. All schools had a high percentage (>90%) of students who received free or reduced lunch, an indicator of low socio-economic status, which was therefore not considered as a separate factor in the randomization process. Intervention students received the IYG intervention, delivered in the 7th and 8th grades; comparison students received their regular health classes, which varied by school.

Participants

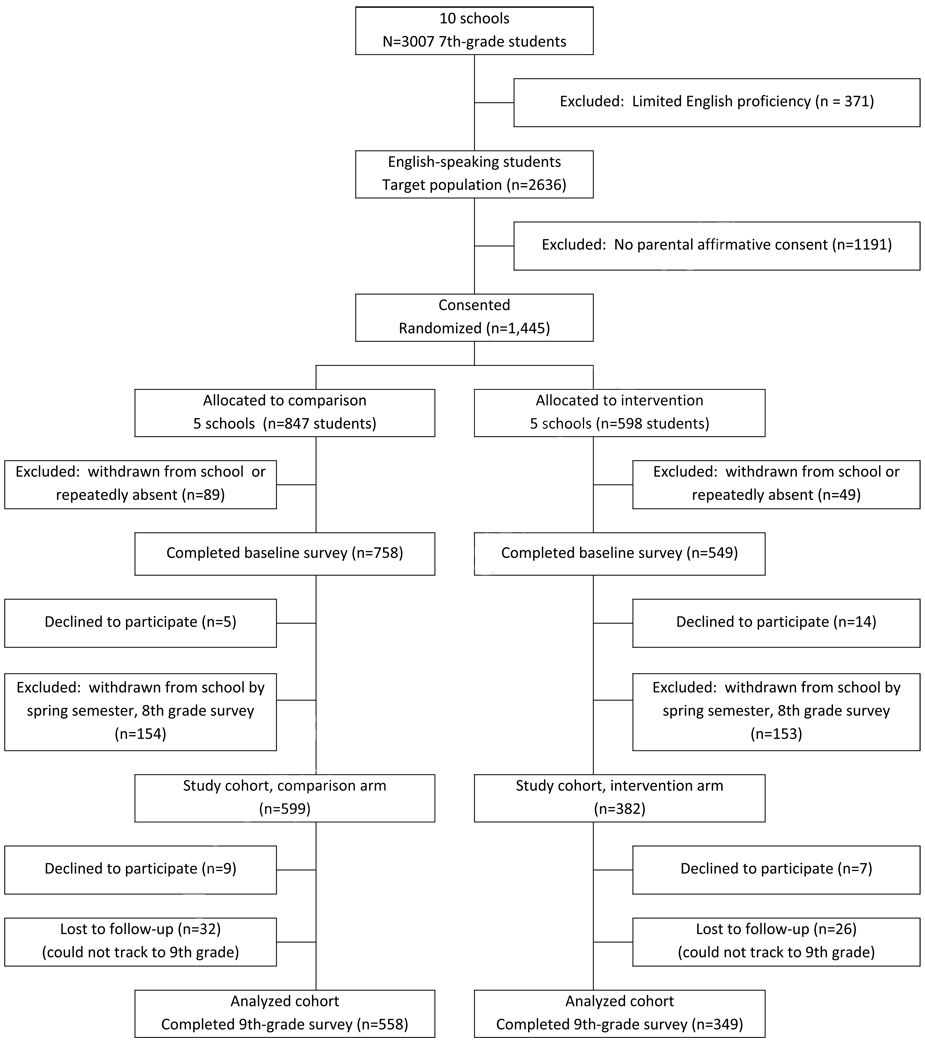

Students were offered a $5 incentive for returning the parental consent form; student assent was obtained at the time of the baseline survey. There was no significant difference in the consent rate between the intervention and comparison conditions (Figure 1). The sample size imbalance between the intervention and comparison conditions was not associated with recruitment or consent procedures; these were performed before randomization occurred.

Figure 1.

Flow of Study Participants

Of consented students, 90% completed the baseline survey in the fall of 2004, for which they received a $5 incentive. Seventh- and eighth-grade follow-up surveys were conducted in spring 2005 and 2006, respectively: students received a $10 incentive for participating in each. Seventh-grade surveys were completed by 1,193 students (91% of baseline, 83% of consented); eighth-grade surveys were completed by 981 students (75% of baseline, 68% of consented). This attrition reflects the high mobility and student withdrawal rates in the school district.

Because the intervention program was multiyear and school wide, the study cohort for follow-up was defined a priori as those students who had completed a baseline survey and who were still enrolled in their original, randomized school at the at the time of the 8th grade survey. Those in the study cohort (n=981) compared to those who left their assigned school after completing the baseline survey or declined to participate (n=326) were slightly more likely to be female (59% vs. 52%), to report making A’s and B’s (51% vs. 30%), to live with both biological parents (36% vs. 20%), and to have never had sex (90% vs. 80%) (data not shown). For the 9th-grade follow-up surveys, conducted during the 2006/2007 school year, students were tracked and located in over 50 different high schools (in several school districts).

Intervention

The IYG curriculum was developed using a systematic instructional design process, Intervention Mapping (IM) [14], to ground its content in social cognitive theory, social influence models, and the theory of triadic influence [15–17]. Extensive qualitative work and participatory methods with all stakeholders including a teen advisory board provided formative guidance in developing the curriculum and community support for the study.

IYG consists of twelve 7th-grade and twelve 8th-grade 45-minute lessons delivered by trained facilitators. The program integrates group-based classroom activities with personal journaling and individual activities delivered on laptop computers. A life skills decision-making paradigm (Select, Detect, Protect) teaches students to select personal limits regarding risk behaviors, to detect signs or situations that might challenge these limits, and to use refusal skills and other tactics to protect these limits. Specific topics covered in the 7th grade include characteristics of healthy friendships; setting personal limits and practicing refusal skills in a general context (e.g., regarding alcohol and drug use, skipping school, cheating); information about puberty, reproduction and STIs; and setting personal limits and practicing refusal skills related to sexual behavior. The 8th-grade curriculum reviews these topics and also covers: the characteristics of healthy dating relationships; the importance of HIV, STI, and pregnancy testing if a person is sexually active; and skills-training regarding condom and contraceptive use.

The curriculum also includes six parent-child homework activities at each grade level, designed to facilitate dialogue on such topics as friendship qualities, dating, and sexual behavior. The computer component includes a virtual world interface, educational activities (quizzes, animations, peer video, and fact sheets) that target determinants of sexual risk-taking and are tailored to gender and sexual experience, and “real world”-style teen serials with on-line student feedback that allows for real-time group discussion in the classroom. Journaling allows students to express their own opinions and feelings on sensitive topics in a confidential setting.

Data Collection

Survey data were collected using laptop computers via an audio-computer-assisted self-interview (ACASI) [18, 19]. Automatic skip patterns decreased student burden and exposure to sensitive questions. Student data collection was facilitated by trained data collectors who assured participants of their anonymity and of their ability to refuse to answer questions. Data collectors were unaware of study condition. Most data collection was performed in groups at schools except for the 9th-grade follow-up, when some data collection was done individually at other public locations (e.g., libraries).

Process Evaluation

We collected process data to monitor dose and fidelity of intervention implementation. Student attendance sheets and facilitator activity logs were used to assess exposure to both classroom and computer-based curricula. Two-thirds (66.19%, n=231) of students in the analysis cohort attended at least 20 of the 24 lessons from the combined 7th and 8th grade curricula (data not shown).

Primary Outcome Measure

The effect of the intervention on delayed sexual initiation at the 9th grade follow-up for those students who reported no lifetime sexual activity at baseline was assessed as the primary outcome. The primary hypothesis tested was that the intervention would decrease the number of adolescents who initiated sexual activity by the 9th grade relative to those in the comparison schools. Sexual activity was defined as participation in vaginal, oral, or anal sex. Sexual activity questions were defined in advance and were worded in a gender-neutral manner to illicit responses for same and opposite-sex partners.

Secondary Outcome Measures

Sexual behaviors

Secondary outcome measures examined the impact of the intervention on 1) delayed initiation of specific types of sex (oral, vaginal, anal), 2) delayed sexual initiation by gender and racial/ethnicity, and 3) reduced risk behavior at the 9th-grade follow-up for those who reported being sexually active in the last three months. Additional endpoints were assessed for sexually active students All sexual behavior measures were adapted from existing surveys and extensively pilot tested among urban middle school populations [20–23].

Psychosocial measures

Psychosocial variables based on social cognitive theories were also assessed, using measures adapted from existing surveys and extensively pilot tested [9, 20, 21, 24, 25]. These variables measure the determinants that the intervention addressed and have been found in many studies to impact behavior change [6].

Analysis Approach

The analysis examined the impact of the intervention from baseline to 9th grade follow-up (approximately 24 months). Descriptive analyses were conducted on the analyzed cohort to test for differences between intervention (n=349) and comparison groups (n=558) at baseline using t-tests and chi-square tests looking for any differences in the outcome measures, both behavioral and psychosocial at baseline. The following demographic measures were also compared between the treatment conditions: gender, age, ethnicity, parental education, school grades, and language spoken at home. Differences were used as potential confounders in the initial phase of modeling. If a variable was both significantly related to the dependent variable using a more conservative significance level of p = 0.10, and differentially distributed between treatment conditions, it was retained in the final model. Because of the second criteria, relationship to the dependent variable, the set of covariates included in each model varied from outcome to outcome. This was done, rather than keeping all covariates in all models, in order to minimize data loss due to missingness in the demographic measures as well as to fit the most parsimonious model needed to correctly make a comparison between the two treatment conditions.

Subjects were only removed from an analysis when they had missing data on the variables included in that analysis; missing data were not imputed. Observations from students within the same school could not be assumed to be independent (ICC ranged from 0 to 0.03); therefore, multi-level models were used. Each model contained baseline measures of the dependent variable, where appropriate, as well as any other covariate judged to be a potential confounder. A dichotomous variable indicating treatment condition was entered into each model. The regression coefficient from this measure was then used to test for intervention effectiveness. The Wald statistic, ratio of the regression parameter to its standard error, was used to test for statistical significance. For all dichotomous outcomes, a multilevel regression model for binary outcomes with a log link function was used, resulting in a relative risk ratio as the effect size. For continuous outcomes, a linear multilevel model was used resulting in an estimate of the difference in the adjusted means as the effect size. All analyses were conducted using two-tailed tests, and no adjustments were made for multiple tests of significance. The primary and secondary hypotheses were stated a priori. Statistical significance was set at p≤0.05.

Three sample groups were used in the analysis. The psychosocial variables were analyzed on the entire analyzed cohort (n=907). Sexual initiation variables were analyzed only on those students who had not engaged in the behavior at the baseline measure. For sexual behavior measures other than the initiation measure, only students who reported sexual activity within the last three months were included in the analysis. Attrition analyses were conducted to determine differences in those retained for the analyzed cohort (n=907) and those who were not retained in the study cohort (n=74) and also if they were differential between intervention and control groups.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics for the Analyzed Cohort

Table 1 describes the demographic characteristics of the analyzed cohort at baseline. No significant differences by intervention and comparison conditions were observed at baseline for sexual behavior, while some differences in the distribution of age, ethnic status and in a few psychosocial variables were found.

Table 1.

Comparability of Intervention and Comparison Conditions among the Analyzed Cohort (n=907) at Baseline

| Comparison (n= 558) |

Intervention (n=349) |

Total (n=907) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic Characteristics | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Female | 326 | 58.4 | 210 | 60.2 | 536 | 59.1 |

| Race/Ethnicity * | ||||||

| African-American | 218 | 39.1 | 166 | 47.6 | 384 | 42.3 |

| Hispanic | 249 | 44.6 | 150 | 43.0 | 399 | 44.0 |

| Other | 91 | 16.3 | 33 | 9.5 | 124 | 13.7 |

| Age in years: Mean (SD) * | 13.0 (0.51) | 13.1 (0.57) | 13.0 (0.54) | |||

| Parents/Guardians in home | ||||||

| Living with 2 parents | 272 | 48.8 | 154 | 44.0 | 426 | 46.7 |

| Living with 1 parent | 186 | 33.3 | 128 | 36.7 | 314 | 34.6 |

| Living with someone other than parent | 90 | 16.1 | 52 | 14.9 | 142 | 15.7 |

| Self-Reported Grades in School | ||||||

| Mostly A’s and B’s | 299 | 53.7 | 164 | 47.1 | 463 | 51.2 |

| Mostly B’s and Cs’ | 225 | 40.4 | 159 | 45.7 | 384 | 42.4 |

| Mostly C’s & D’s/D’s & F’s | 33 | 5.9 | 25 | 7.2 | 58 | 6.4 |

| Maximum Parental/Guardian Education | ||||||

| Less than high school | 151 | 28.5 | 100 | 30.0 | 251 | 29.1 |

| High school | 116 | 21.9 | 88 | 26.4 | 204 | 23.6 |

| Some college | 90 | 17.0 | 59 | 17.7 | 149 | 17.3 |

| College graduate | 173 | 32.6 | 86 | 25.8 | 259 | 30.0 |

| Comparisona | Interventiona | Totala | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Psychosocial Measures (No. items; range of scores)[Cronbach’s α] | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) | Mean | (SD) |

| General Beliefs about Waiting to have Sex (4; 1–4)[0.78] | 3.14 | 0.68 | 3.06 | 0.65 | 3.11 | 0.67 |

| Beliefs about Abstinence until Marriage (3; l–4)[0.72] | 2.86 | 0.70 | 2.80 | 0.75 | 2.84 | 0.72 |

| Perceived Friends’ Beliefs about Waiting to have Sex (3;1–4)[0.75] * | 2.63 | 0.71 | 2.51 | 0.78 | 2.58 | 0.74 |

| Perceived Friends’ Sexual Behavior (4;0–3)[0.77] | 1.27 | 0.70 | 1.29 | 0.74 | 1.28 | 0.72 |

| Self-Efficacy to Refuse Sex (7;l–4)[0.87] | 3.14 | 0.77 | 3.09 | 0.81 | 3.12 | 0.79 |

| Condom Knowledge (3;0–3)[0.51]b | 1.64 | 1.03 | 1.76 | 1.01 | 1.69 | 1.03 |

| Perceived Friends’ Beliefs about Condoms (3;1–4)[0.84] | 3.26 | 0.70 | 3.21 | 0.71 | 3.24 | 0.70 |

| Self-Efficacy to Use Condoms (5;1–3)[0.61] | 2.28 | 0.43 | 2.32 | 0.44 | 2.30 | 0.43 |

| Exposure to Risky Situations (7;0–3)[0.79] | 0.52 | 0.57 | 0.51 | 0.56 | 0.52 | 0.56 |

| STI Signs and Symptoms Knowledge (5; 0–l)[0.46]b | 0.60 | 0.22 | 0.62 | 0.23 | 0.61 | 0.22 |

| HIV/STI Knowledge (4; 0–1)[0.47]b | 0.55 | 0.29 | 0.57 | 0.31 | 0.56 | 0.30 |

| Reasons for Having Sex (8;0–8)[0.61]c | 1.15 | 1.54 | 1.21 | 1.56 | 1.17 | 1.54 |

| Reasons for Not Having Sex (9;0–9)[0.79] c * | 4.88 | 2.54 | 4.42 | 2.65 | 4.70 | 2.59 |

| Intention to Have Oral Sex in the Next Yr (1; 1 −5)[NA] * | 1.84 | 1.12 | 2.00 | 1.24 | 1.90 | 1.17 |

| Intention to Have Vaginal Sex in the Next Yr (1; 1 −5)[NA] | 1.82 | 1.20 | 1.87 | 1.21 | 1.84 | 1.20 |

| Intention to Remain Abstinent until End of High School (1: ,1–5)[NA] | 3.22 | 1.44 | 3.04 | 1.56 | 3.15 | 1.49 |

| Intention to Remain Abstinent until Marriage (1;1–5)[NA] | 2.90 | 1.43 | 2.91 | 1.49 | 2.91 | 1.45 |

| Comparison |

Intervention |

Total |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reported Sexual Behaviors | n | % | n | % | n | % |

| Ever had sex | 46 | 8.3 | 37 | 10.6 | 83 | 9.2 |

| Sex in past 3 mo. | 27 | 4.8 | 22 | 6.3 | 49 | 5.4 |

| Type of sex | ||||||

| Oral sexd | ||||||

| Ever had oral sex | 23 | 4.3 | 15 | 4.4 | 38 | 4.3 |

| Oral sex in past 3 mo. | 13 | 2.4 | 10 | 2.9 | 23 | 2.6 |

| Vaginal sexe | ||||||

| Ever had vaginal sex | 37 | 6.9 | 31 | 9.1 | 68 | 7.7 |

| Vaginal sex in past 3 mo. | 23 | 4.1 | 17 | 4.9 | 40 | 4.6 |

| Condom at last vaginal sex | 32 | 5.7 | 26 | 7.4 | 58 | 6.6 |

| Unprotected vaginal sex past 3 mo. | 9 | 1.6 | 4 | 1.1 | 13 | 1.5 |

| Unprotected vaginal sex with ≥1 partners past 3 mos. | 8 | 1.4 | 4 | 1.1 | 12 | 1.4 |

| Anal sexf | ||||||

| Ever had anal sex | 22 | 4.1 | 11 | 3.3 | 33 | 3.8 |

| Anal sex in past 3 mo. | 11 | 2.0 | 7 | 2.1 | 18 | 2.1 |

| Unprotected anal sex last 3 mos. | 5 | 0.9 | 3 | 0.9 | 8 | 0.9 |

p < 0.05

All psychosocial variables are coded as protective factors except for perceived friends’ sexual behavior, exposure to risky situations, reasons for having sex, oral intent, and vaginal intent.

Though these knowledge scales had low alphas, they were retained as scales, since items reflected salient points covered in the IYG curriculum.

Score reflects number of reasons chosen.

Oral sex was defined as “when someone puts his or her mouth on their partner's penis, vagina, or anus/butt or lets their partner put his or her mouth on their penis, vagina, or anus/butt.”

Vaginal sex was defined as “when a boy puts his penis inside a girl's vagina; some people call this ‘making love’ or ‘doing it.’”

Anal sex was defined as “when a boy puts his penis in his partner's anus or butt.”

Attrition

The analyzed cohort consists of those completing the 9th-grade follow-up survey (Figure 1). No differences were observed in baseline demographic or behavioral variables for participants retained in the trial versus those not retained except for age: those lost to follow-up were slightly older than those retained (mean age 13.2 vs. 13.0 years; data not shown). Further, we examined differences by intervention and comparison status for those not in the defined cohort (those who dropped out before the 8th grade survey), and found no differences in demographic variables or sexual behaviors except for lifetime vaginal sex: (21% comparison vs. 15% intervention; p=.04).

Attrition in the defined cohort was non-differential between the intervention and comparison condition (data not shown).

Effects of the HIV, STI, and Pregnancy Intervention

Almost 30% of those in the comparison condition initiated sex by 9th grade compared to 23% of those in the intervention condition: students in the comparison condition were 30% more likely to initiate sex the 9th grade than students in the intervention condition.

A greater percentage of students in the comparison condition initiated oral, vaginal, or anal sex by the 9th-grade follow-up compared to students in the intervention condition (Table 2). Even after adjusting for covariates, students in the comparison condition had a 1.76 times greater risk of initiating oral sex and a 2.67 times greater risk of initiating anal sex by 9th grade than those in the intervention condition.

Table 2.

Risk of the Comparison Condition for Initiating Sexual Behavior among Those Who Reported No Experience at 7th Grade Baseline but Reported Having Initiated at 9th Grade Follow-Up, in the Analyzed Cohort, by Gender and Race/Ethnicity

| Totala Responses n | Comparison % yes | Intervention % yes | ARR | (95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Initiated Sex | 817 of 823 | 29.9% (n=509) | 23.4% (n=308) | 1.29 * | (1.02, 1.64) | |

| Hispanicb | 381 | 27.8 | 17.4 | 1.64 * | (1.09, 2.47) | |

| African-Americanb | 324 | 33.7 | 30.6 | 1.07 | (0.78, 1.46) | |

| Males | 307 | 35.7 | 32.4 | 1.12 | (0.80, 1.56) | |

| Females | 510 | 26.1 | 18.5 | 1.42 * | (1.01, 2.01) | |

| Initiated Specific Types of Sex | ||||||

| Oral | 831 of 837 | 17.6% (n=512) | 10.0% (n=319) | 1.76 ** | (1.21, 2.56) | |

| Hispanicb | 375 | 17.0 | 10.0 | 1.71 | (0.97, 3.03) | |

| African-Americanb | 340 | 17.7 | 9.5 | 1.84 * | (1.04, 3.25) | |

| Males | 319 | 25.0 | 17.6 | 1.53 | (0.96, 2.44) | |

| Females | 512 | 12.8 | 5.5 | 2.14 * | (1.12, 4.09) | |

| Vaginal | 804 of 810 | 26.9% (n=499) | 22.3% (n=305) | 1.26 | (0.98, 1.61) | |

| Hispanicb | 379 | 24.1 | 14.8 | 1.67 * | (1.06, 2.62) | |

| African-Americanb | 319 | 32.8 | 30.1 | 1.09 | (0.78, 1.50) | |

| Males | 307 | 30.8 | 29.4 | 1.12 | (0.79, 1.60) | |

| Females | 497 | 24.3 | 18.4 | 1.36 | (0.95, 1.93 | |

| Anal | 835 of 842 | 9.9% (n=514) | 3.7% (n=321) | 2.67 ** | (1.45, 4.94) | |

| Hispanicb | 372 | 9.4 | 4.4 | 2.19 | (0.91, 5.26) | |

| African-Americanb | 345 | 11.9 | 3.3 | 3.12 * | (1.21, 8.06) | |

| Males | 322 | 16.3 | 7.5 | 2.31 * | (1.13, 4.72) | |

| Females | 513 | 5.8 | 1.5 | 3.90 * | (1.16, 13.13) | |

Note: All models adjusted for age, gender, and race/ethnicity

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

For initiated sex and the three specific types of sex (oral, vaginal, anal), Total Responses are the number of students answering the question at the 9th-grade follow-up of those who had reported no sexual experience (initiated sex) or no experience with that specific type of sex at baseline.

Due to small sample sizes, the racial/ethnic comparison did not include the “other” subgroup.

Over one-quarter of Hispanic students in the comparison condition initiated sex compared to 17.4% of Hispanic students in the intervention condition (Table 2). After adjusting for covariates, Hispanics students in the comparison condition were 64% more likely to initiate sex than Hispanics in the intervention condition. Among African American and male students, there were no statistical differences in initiation of sex between conditions. Among females, 26.1% of those in the comparison group initiated sex by the 9th grade compared to 18.5% of those in the intervention group. After adjusting for covariates, females allocated to the comparison condition had a 1.42 times greater risk of initiating sex by 9th grade than females in the intervention condition.

The prevalence of initiation of oral sex by 9th grade was significantly higher among students in the comparison condition who were African American or female than among those in the intervention condition. The subgroup analysis showed significant differences between intervention and comparison groups for initiation of vaginal sex only among Hispanics and for initiation of anal sex among African Americans, males, and females.

Students who reported being sexually active at the 9th-grade follow-up and who were in the comparison condition had a higher frequency of vaginal sex during the last 3 months relative to the intervention condition (Table 3). No intervention effects were observed for the number of times students had sex under the influence of alcohol, used condoms, or for number of partners.

Table 3.

Risk of the Comparison Condition for Engaging in the Behavior among Students Reporting Specific Sexual Behaviors in the Last 3 Months at 9th-Grade Follow-Upa

| nb | Comparison | Intervention | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oral sex in last three months | 85 | 58 | 27 |

| Vaginal sex in last three months | 166 | 103 | 63 |

| Anal sex in last three months | 37 | 30 | 7 |

| Vaginal, oral, or anal sex in last three months | 197 | 124 | 73 |

| nb | ARR | 95% CI | |

| Condom at last sex (for vaginal sex only) | 166 | 1.04 | (0.87,1.25) |

| Number of times having sex in the last 3 months: 2 or more versus 1 | |||

| Oral | 85 | 0.93 | (0.69, 1.28) |

| Vaginal | 165 | 1.30* | (1.02, 1.66) |

| Analc | 37 | 27.14 | (0.10, 7693) |

| Number of times having sex in the last 3 months with drug/alcohol: 1 or more versus 0 | |||

| Oral | 83 | 1.24 | (0.59, 2.60) |

| Vaginal | 164 | 0.69 | (0.35, 1.35) |

| Analc | 33 | 0.57 | (0.09, 3.77) |

| Number of times having sex in the last 3 months without a condom: 1 or more versus 0 | |||

| Vaginal | 166 | 0.92 | (0.71, 1.19) |

| Analc | 34 | 1.12 | (0.38, 3.35) |

| Number of lifetime partners: 2 or more versus 1 | |||

| Oral | 84 | 1.17 | (0.82, 1.68) |

| Vaginal | 160 | 1.05 | (0.89, 1.24) |

| Analc | 35 | 0.89 | (0.16, 4.81) |

| Number of partners in the last 3 months: 2 or more versus 1 | |||

| Vaginal | 158 | 1.31 | (0.83, 2.07) |

| Analc | 37 | Unable to estimate | |

| Number of partners in the last 3 months without a condom: 1 or more versus 0 | |||

| Vaginal | 165 | 0.86 | (0.63, 1.18) |

| Number of times having sex in the last 3 months without effective pregnancy preventiond | 162 | 0.83 | (0.51, 1.35) |

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

All models adjusted for age, gender, ethnicity, and baseline score

Sample sizes vary due to missing data

Analyses had little precision and power due to small sample sizes

Effective pregnancy prevention was defined for the student in the survey by listing effective pregnancy prevention methods.

At the time of the 8th-grade post-intervention survey, students in the intervention condition had more positive beliefs about abstinence until marriage, perceived their friends as having more positive beliefs about waiting to have sex, had greater confidence in refusing sex and using condoms, had greater knowledge about HIV and STI signs and symptoms and about using condoms to prevent them, reported being exposed to fewer risky situations, and cited more reasons for not having sex, relative to students in the comparison condition (Table 4). They also reported fewer intentions to have oral sex in the next year and greater intentions to remain abstinent through high school when compared to the comparison condition. Some intervention effects on psychosocial variables were sustained through 9th grade.

Table 4.

IYG Psychosocial Outcomes, 8th and 9th Grade, among the Analyzed Cohort (n=907)a

| Total Sample | 8th Grade |

9th Grade |

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Difference in Adjusted Mean |

Intervention |

Comparison |

Difference in Adjusted Mean |

Intervention |

Comparison |

|||||||

| Outcomec | nb | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | nb | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| General beliefs about waiting to have sex | 869 | 0.01 | 2.86 | 0.57 | 2.89 | 0.66 | 874 | 2.81 | 0.59 | 2.82 | 0.62 | |

| Beliefs about abstinence until marriage | 862 | 0.17 ** | 2.78 | 0.70 | 2.63 | 0.74 | 864 | 0.12 ** | 2.75 | 0.69 | 2.65 | 0.73 |

| Perceived friends’ beliefs about waiting to have sex | 875 | 0.17 ** | 2.47 | 0.71 | 2.35 | 0.69 | 873 | 0.06 | 2.32 | 0.71 | 2.29 | 0.65 |

| Perceived friends’ sexual behavior | 830 | −0.05 | 1.58 | 0.71 | 1.62 | 0.70 | 832 | −0.09 * | 1.77 | 0.74 | 1.83 | 0.69 |

| Self-efficacy to refuse sex | 853 | 0.11 * | 3.07 | 0.85 | 2.97 | 0.86 | 856 | 0.08 | 3.07 | 0.87 | 3.01 | 0.83 |

| Condom knowledge | 896 | 0.53 ** | 2.58 | 0.71 | 2.04 | 1.01 | 893 | 0.16 ** | 2.41 | 0.79 | 2.25 | 0.95 |

| Perceived friends’ beliefs about condoms | 861 | 0.06 | 3.36 | 0.68 | 3.30 | 0.67 | 869 | 0.12 ** | 3.32 | 0.64 | 3.21 | 0.68 |

| Self-efficacy to use condoms | 827 | 0.12 ** | 2.51 | 0.39 | 2.37 | 0.44 | 833 | 0.02 | 2.46 | 0.44 | 2.41 | 0.44 |

| Exposure to risky situations | 862 | −0.10 * | 0.75 | 0.65 | 0.82 | 0.69 | 868 | −0.12 * | 0.86 | 0.86 | 0.96 | 0.91 |

| STI signs/sx knowledge | 870 | 0.10 ** | 0.83 | 0.24 | 0.78 | 0.26 | 869 | 0.05 ** | 0.82 | 0.18 | 0.76 | 0.20 |

| HIV/STI knowledge | 888 | 0.17 ** | 0.82 | 0.21 | 0.65 | 0.29 | 894 | 0.10 ** | 0.80 | 0.24 | 0.70 | 0.29 |

| Reasons to have sex | 839 | 0.08 | 1.62 | 1.78 | 1.48 | 1.49 | 844 | 0.05 | 1.50 | 1.52 | 1.44 | 1.47 |

| Reasons not to have sex | 892 | 0.71 ** | 4.87 | 2.45 | 4.29 | 2.49 | 890 | 0.17 | 4.32 | 2.38 | 4.25 | 2.43 |

| Intention: oral in next year | 883 | −0.24 ** | 1.97 | 1.26 | 2.14 | 1.24 | 881 | −0.12 | 2.10 | 1.27 | 2.15 | 1.26 |

| Intention: vaginal in next year | 877 | −0.06 | 2.26 | 1.32 | 2.31 | 1.30 | 876 | −0.03 | 2.51 | 1.38 | 2.54 | 1.37 |

| Intention: abstinent thru high school | 875 | 0.31 ** | 3.16 | 1.44 | 2.89 | 1.41 | 876 | 0.03 | 2.85 | 1.37 | 2.85 | 1.40 |

| Intention: abstinent until marriage | 877 | 0.16 | 2.67 | 1.40 | 2.48 | 1.33 | 873 | 0.11 | 2.54 | 1.31 | 2.41 | 1.30 |

p<0.05

p<0.01

All models adjusted for age, gender, race/ethnicity and baseline score

Sample sizes vary due missing data.

All psychosocial variables are coded as protective factors except for perceived friends’ sexual behavior, exposure to risky situations, reasons for having sex, oral intent, and vaginal intent.

DISCUSSION

This study is the first trial, to our knowledge, demonstrating that a middle school-based HIV-, STI-, and pregnancy-prevention intervention can delay overall sexual behavior when defined as oral, vaginal, and anal sex and can impact specific sexual behaviors such as oral and anal sex. Subgroup analysis revealed differential effects by gender and race/ethnicity. In particular, the intervention delayed overall sexual behavior as well as oral and anal sex among females. IYG also had sustained positive effects on such psychosocial variables as more positive beliefs about abstinence and being involved in fewer risky situations.

Students who were sexually active at baseline (9%), in the Fall of 7th grade, represent particularly high-risk populations with respect to health outcomes [26] and may need more intensive interventions. An intervention effect on the frequency of vaginal sex and anal sex during the prior three months was observed in this study, despite reduced analytic power to detect impact in specific types of sexual behavior among those sexually active. Only one other middle-school curriculum-based study published to date has reported significant reductions in frequency of sexual activity [9].

Exposure to oral and anal sex appears to be increasing among teens and young adults [27]; however, no middle-school-age programs to our knowledge have directly addressed or evaluated anal and oral sex outcomes. Research suggests that adolescents perceive oral sex as having fewer health consequences than vaginal sex [28–31], and results from the entire baseline sample indicate that as many as 7.9% of 7th graders report lifetime oral sex and 6.9% report lifetime anal sex [32], an extremely high-risk behavior for HIV transmission [11, 12]. It is unknown, however, if these results can be generalized to other populations, as few studies have measured anal and oral sex among middle-school populations.

An important finding was the magnitude of the behavioral impact of It’s Your Game when compared to similar programs. For example, students in the comparison group were 29% greater risk of initiating sex by the 9th grade than those who were not be exposed to IYG. Furthermore, the program significantly reduced (by 23%) the number of students having vaginal sex two or more times in the past three months. This These results compares to other effective programs published to date that tend to lower the prevalence of adolescents in engaging such risk behaviors by about a third [8].

National data emphasize the need to implement intervention programs as early as possible: 11% of 6th graders, 15% of 7th graders, 18% of 8th graders, and 33% of 9th graders have reported lifetime sexual activity [4, 5]. This rapid acquisition of sexual behavior is cause for concern and clearly demonstrates that early comprehensive sex education such as IYG is imperative. However, in the US, most students are not receiving comprehensive sex education or are receiving it too late [33].

The efficacy of IYG may be partly attributable to the innovative multi-modal application of computer-based gaming technology, interactive computer-based activities, and small group classroom interaction that does not currently exist in middle-school HIV/STI- and pregnancy-prevention curricula [34]. Its capability to provide interactive and individual tailored experiences that are also confidential is particularly salient when considering the sensitive nature of these topics.

Methodological strengths of the study include a well-conducted randomized controlled trial design, the ACASI interview for greater self-report validity, and our high level of retention among students in our defined cohort, and use of previously established measures [9, 20–25] . Moreover, no other intervention trial has assessed the impact of the intervention of specific types of sexual behaviors. Most studies examine the impact on sexual intercourse which may be interpreted in many ways by the respondent.

This study has some limitations: self-reported outcome measures; unknown generalizabilty to other populations; a small sample of sexually active youth in 7th grade, leaving little statistical power among these youth; a higher proportion of female participants; and the study participation rate, although similar to many school-based studies [9, 35]. School-based studies such as this one may not be able to reach extremely high-risk youth who are highly mobile or who drop out early. Studies should be conducted to examine how to track and intervene on such populations.

Another potential limitation was the attrition and our inability to conduct an intention to treat analysis of those who were lost to follow-up. A decision was made a-priori to define the study cohort as those students who were enrolled in the 8th grade at the completion of the spring semester because of the lack of resources to follow the entire cohort enrolled at baseline and also to ensure that those enrolled in comparison and intervention conditions were followed in the same manner.

While costly, a much larger sample is needed to evaluate results among sexually active middle-school youth and to conduct subgroup analysis among ethnic and gender groups. It is important to understand the reason that our program and other programs have differential impacts for ethnic and gender groups because of disparities in risk; however few studies have enough power to examine subgroup differences. Further, the program included multiple components that were tested together; the efficacy of the individual components is therefore unknown. Future studies should test the efficacy of the intervention among different populations and should test the efficacy of the computer intervention alone.

Conclusion

The It’s Your Game curriculum was effective among low-income, urban, African-American and Hispanic middle school students. This provides evidence that school-based sexual health interventions can be implemented early and can delay initiation of sexual activity. This has important implications for implementing policy and for dissemination of evidence-based interventions.

Acknowledgements

All authors contributed to the concept and design of the study and the process of drafting and revising the manuscript. No authors have any potential conflicts of interest. This study was funded by the National Institutes of Mental Health (R01 MH66640-01). These findings have been presented at the Centers for Disease Control National Prevention Research Center 2008 Annual Conference. We would like to thank Belinda Flores, MPH for her editorial assistance with this manuscript.

Source of Support: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Mental Health (R01 MH66640-01). The National Institutes of Mental Health had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Reference List

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS Surveillance Report 2007. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009;Vol. 19

- 2.National Office of AIDS Policy. [Accessed May 1, 2008];Youth and HIV/AIDS 2000: A new American agenda. [Online]. Available at: < http://www.thebody.com/content/art36.html>.

- 3.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ, et al. Births: Preliminary data for 2007. [Accessed March 21, 2009];National Vital Statistics Report. 57(12) [Online]. Available at: < http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr57/nvsr57_12.pdf>. [PubMed]

- 4.Shanklin SL, Brener N, McManus T, Kinchen S, Kann L. [Accessed March 21, 2009];Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2005 Middle School Youth Risk Behavior Survey. 2007 Available at: < http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/middleschool2005/pdf/YRBS_MS_05_fullreport.pdf>.

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance: United States, 2007. [Accessed March 21, 2009];MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Surveillance Summaries. 2008 57:SS-4. Available: < http://www.cdc.gov/HealthyYouth/yrbs/pdf/yrbss07_mmwr.pdf>. [PubMed]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. [Accessed March 21, 2009];HIV/AIDS Surveillance in Adolescents and Young Adults (through 2006): Slide 1: Proportion of HIV/AIDS cases and population among adolescents 13–19 years of age, by race/ethnicity diagnosed in 2006--33 states. [Online]. Available at: < http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/slides/adolescents/slides/Adolescents.pdf>.

- 7.AVERT. [Accessed July 17, 2008];HIV and AIDS in America. [Online]. Available at: < http://www.avert.org/america.htm>.

- 8.Kirby D. Emerging answers 2007: Research findings on programs to reduce teen pregnancy and sexually transmitted diseases. Washington, D.C.: National Campaign to Prevent Teen and Unplanned Pregnancy; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coyle KK, Kirby DB, Main BV, et al. Draw the Line/Respect the Line: A randomized trial of a middle school intervention to reduce sexual risk behaviors. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:843–851. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jemmott JB, III, Jemmott LS, Fong GT. Abstinence and safer sex HIV risk-reduction interventions for African-American adolescents. JAMA. 1998;279:1529–1536. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.19.1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halperin DT. Heterosexual anal intercourse: prevalence, cultural factors, and HIV infection and other health risks, Part I. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 1999;13:717–730. doi: 10.1089/apc.1999.13.717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hawkins DA. Oral sex and HIV transmission. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:307–308. doi: 10.1136/sti.77.5.307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Graham JW, Flay BR, Anderson Johnson C, et al. Group Comparability: A Multiattribute Utility Measurement Approach to the Use of Random Assignment with Small Numbers of Aggregated Units. Eval Rev. 1984;8:247–260. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bartholomew LK, Parcel GS, Kok G, et al. Planning Health Promotion Programs: An Intervention Mapping Approach. 2nd ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bandura A. Social Foundations of Thought and Action: A Social Cognitive Theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McGuire W. Social psychology. In: Dodwell PC, editor. New Horizons in Psychology. Middlesex, England: Penguin Books; 1972. pp. 219–242. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Flay BR, Petratis J. The theory of triadic influence: A new theory of health behavior with implications for preventive interventions. Greenwich, Conn: JAI Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Turner CF, Ku L, Rogers SM, et al. Adolescent sexual behavior, drug use, and violence: Increased reporting with computer survey technology. Science. 1998;280:867–873. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5365.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rew L, Horner SD, Riesch L, et al. Computer-assisted survey interviewing of school-age children. ANS Adv Nurs Sci. 2004;27:129–137. doi: 10.1097/00012272-200404000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coyle K, Basen-Engquist K, Kirby D, et al. Safer choices: Reducing teen pregnancy, HIV, and STDs. Public Health Rep. 2001;116:82–93. doi: 10.1093/phr/116.S1.82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Basen-Engquist K, Coyle KK, Parcel GS, et al. Schoolwide effects of a multicomponent HIV, STD, and pregnancy prevention program for high school students. Health Educ Behav. 2001;28:166–185. doi: 10.1177/109019810102800204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ball J, Pelton J, Forehand R, et al. Methodological overview of the Parents Matter! program. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2004;13:21–34. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miller KS, Clark LF, Wendell DA, et al. Adolescent heterosexual experience: A new typology. J Adolesc Health. 1997;20:179–186. doi: 10.1016/S1054-139X(96)00182-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Basen-Engquist K, Masse LC, Coyle K, et al. Validity of scales measuring the psychosocial determinants of HIV/STD-related risk behavior in adolescents. Health Educ Res. 1999;14:25–38. doi: 10.1093/her/14.1.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Borawski EA, Trapl ES, Lovegreen LD, et al. Effectiveness of abstinence-until-marriage sex education among middle school adolescents. Am J Health Behav. 2005;29:423–434. doi: 10.5555/ajhb.2005.29.5.423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Albert B, Brown S, Flanigan CM, editors. 14 and Younger: The Sexual Behavior of Young Adolescents. Washington, DC: The National Campaign to Prevent Teen Pregnancy; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lindberg LD, Jones R, Santelli JS. Non-coital sexual activities among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2008 doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2007.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boekeloo BO, Howard DE. Oral sexual experience among young adolescents receiving general health examinations. Am J Health Behav. 2002;26:306–314. doi: 10.5993/ajhb.26.4.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Prinstein MJ, Meade CS, Cohen GL. Adolescent oral sex, peer popularity, and perceptions of best friends' sexual behavior. J Pediatr Psychol. 2003;28:243–249. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsg012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Brady SS, Halpern-Felsher BL. Adolescents' reported consequences of having oral sex versus vaginal sex. Pediatrics. 2007;119:229–236. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cornell JL, Halpern-Felsher BL. Adolescents tell us why teens have oral sex. J Adolesc Health. 2006;38:299–301. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2005.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Markham CM, Fleschler PM, Addy RC, et al. Patterns of vaginal, oral, and anal sexual intercourse in an urban seventh-grade population. J Sch Health. 2009;79:193–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.2008.00389.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Abma JC, Martinez GM, Mosher WD, et al. Teenagers in the United States: Sexual activity, contraceptive use, and childbearing. Vital Health Stat. 2002;23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shegog R, Markham C, Peskin M, et al. "It's your game": an innovative multimedia virtual world to prevent HIV/STI and pregnancy in middle school youth. Medinfo. 2007;12:983–987. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Halpern-Felsher BL, Cornell JL, Kropp RY, et al. Oral versus vaginal sex among adolescents: Perceptions, attitudes, and behavior. Pediatrics. 2005;115:845–851. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]