Abstract

This secondary analysis used Goffman’s (1963) model of stigma to examine how social support and health status are related to HIV stigma, after controlling for specific socio-demographic factors, and how these relationships differed between men and women living with HIV. Baseline data from 183 subjects in a behavioral randomized clinical trial were analyzed using multi-group structural equation modeling. Women reported significantly higher levels of stigma than men after controlling for race, history of injecting drug use, and exposure category. HIV-related stigma was negatively predicted by social support regardless of gender. The theorized model explained a significant amount of the variance in stigma for men and women (24.4% and 44%, respectively) and may provide novel and individualized intervention points for health care providers to affect positive change on perceived stigma for the person living with HIV. The study offers insight into understanding the relationships among gender, health status, social support, and HIV-related stigma.

Keywords: HIV infection, gender differences, stigma

Stigma remains a salient issue for people living with HIV (PLWH) in the United States. Although there is now greater understanding about the disease and its transmission than in past decades, efforts to reduce stigma and its repercussions for PLWH have shown only moderate success. HIV related stigma is associated with negative self-perceptions (Frable, Wortman, & Joseph, 1997), lower rates of HIV-status disclosure (Clark, Lindner, Armistead, & Austin, 2003; Vanable, Carey, Blair, & Littlewood, 2006), decreased health care utilization (Reece, 2003), lower rates of HIV and STD testing and disclosure (Fortenberry et al., 2002; Vanable et al., 2006), lower quality of life (Holzemer et al., 2009), and lower medication adherence in men and women (Carr & Gramling, 2004; Vanable et al., 2006; Waite, Paasche-Orlow, Rintamaki, Davis, & Wolf, 2008). Stigma is also a public health issue. Because of the social nature of transmission, interventions targeted at alleviating stigma have been implemented to help to control the spread of HIV (Herek, Capitanio, & Widaman, 2002, 2003). Additionally, research has shown that without intervention, stigma levels in PLWH remain relatively constant over time (Clark et al., 2003). Due to the ramifications of stigma for PLWH, and for a society trying to control the spread of the disease, health care providers need to have effective interventions available to address stigma at the individual level.

Our study is a secondary analysis of data collected in a behavioral randomized clinical trial testing the efficacy of a nurse-led telephone intervention to increase medication adherence in PLWH. For this study, we (a) identified the significant constructs of Goffman’s (1963) stigma model and existing literature related to HIV-related stigma appropriate for model testing (as described below in the background and theoretical model section); (b) examined how physical health status and social support predict HIV-related stigma in PLWH using the theoretical model, after controlling for race, history of injecting drug use (IDU), and HIV-exposure category; and (c) examined the differences in the model between genders. This theorized framework may contribute to an increased understanding about HIV-related stigma and may serve as a guide for selecting tailored interventions targeted specifically at decreasing perceived HIV-related stigma for the individual living with this disease.

Background and the Theoretical Model

The concept of stigma as it relates to social identity was first introduced by Erving Goffman in 1963. In his highly influential book, Stigma: Notes on the Management of a Spoiled Identity, he defined stigma as “an attribute that is deeply discrediting” (Goffman, 1963, p. 3). He identified three different types of stigma: (a) abominations of the body; (b) blemishes of individual character; and (c) tribal stigma of race, nation, and religion; and recognized that the issue does not exist separate from the context in which it resides, immediately noting that the term requires a “language of relationships, not attributes” (Goffman, 1963, p. 3).

HIV remained shrouded in mystery for several years after its initial identification, contributing to the stigma of those who were infected and those whose lifestyles indicated they might be at risk for infection. Although there were no initial telltale physical markings of the disease, people in the later stages of infection were noted to be frail and gaunt, with severe facial and body wasting. Purplish-blue lesions caused by Kaposi’s sarcoma were also visibly present on people in this later stage. These more visible signs diminished the “concealability” of the disease and made it easier for others to single out those who were infected (Chin, 2000). Following Goffman’s (1963) theoretical logic, the social environment of the individual stigma, which is about relationships and not attributes, as well as personal health status, which may indirectly affect concealability, may have an impact on the perceived stigma of the individual. Therefore, these two variables are hypothesized as predictors of stigma in the proposed study.

The unique circumstances of disease transmission and of the populations in the United States most dramatically affected by HIV have created a layering of stigma, whereby multiple factors can, individually and in the aggregate, lead to stigma (Herek, 1999). In order to design effective interventions, it is first necessary to examine how these layered factors, including gender, differently affect the experience of stigmatization and which factors may predispose an individual to or protect an individual from the harmful effects of stigma. For example, male homosexuality and HIV have been inextricably linked throughout the course of the disease. Despite advances in education and prevention efforts, a great deal of confusion persists about disease transmission within the homosexual population. Herek, Widaman, and Capitanio (2005) found that approximately one third of male respondents and 45% of female respondents in a national telephone survey incorrectly believed that a man could contract HIV through unprotected sex with an uninfected male partner. These findings led the researchers to speculate that for many Americans, homosexual sex was directly equated to HIV transmission.

Another potential stigmatizing layer frequently associated with HIV is intravenous drug use (IDU). Estimates are that approximately 20% of the existing HIV cases in the United States are the result of IDU (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2002). In a qualitative study of injection drug-using women, Lally, Montstream-Quas, Tanaka, Tedeschi, and Morrow (2008) found IDU to be a barrier to HIV testing and treatment. Interestingly, another study found that among 147 young people aged 16–29 years living with HIV, IDU was associated with lower shame and perceived HIV-related stigma than the shame experienced with homosexual transmission; the authors speculated that the layering of issues may have resulted in lower concerns about disease-related stigma (Swendeman, Rotheram-Borus, Comulada, Weiss, & Ramos, 2006).

The incidence rates across racial and ethnic groups may offer some additional information about perceived stigma in PLWH. Of those individuals diagnosed with HIV or AIDS in 2007, 51% were Black, 30% White, and 18% Hispanic; fewer than 1% each were American Indian/Alaskan Native and Asian/Pacific Islander (CDC, 2009). Additionally, race has been shown to be significantly related to HIV-associated morbidity/mortality and initiation of treatment (Crystal, Sambamoorthi, Moynihan, & McSpiritt, 2001; McGinnis et al., 2003). Specifically, the proportion of PLWH surviving for more than 36 months after an AIDS diagnosis in 2002 was .89 for Asians, .84 for Hispanics/Latinos, .84 for Whites, and .73 for Black/African Americans (Crystal et al., 2001). According to the CDC (2009), survival rates in 2007 were greater for Asians, Whites, and Hispanic/Latinos than for Black/African Americans.

Finally, there remains the added dimension of gender and its relationship to HIV-related stigma. Women in the United States, especially women of color, are increasingly affected by the disease. Among adolescent and adult women, the proportion of AIDS cases more than tripled from 7% in 1985 to 26% in 2002 (CDC, 2006). The CDC estimated that at the end of 2007, 64.7% of the women living with HIV/AIDS were Black/African American, 15% were Latino, and 18.5% were White. In 2005 the rate of AIDS diagnoses for Black/American American women was 23 times the rate for White women and 4 times the rate for Hispanic/Latino women (CDC, 2009). Globally, women account for a full 50% of the 33 million PLWH (World Health Organization, 2007).

For women living with the disease, stigma plays a unique and disturbing role in their lives. A meta-synthesis of qualitative findings on stigma in this population by Sandelowski, Lambe, and Barroso (2004) showed that “stigma is virtually synonymous with the experience of HIV infection in women” (p. 124). This study revealed that women, by virtue of being women, had several unique issues that potentially resulted in real and perceived stigma, including the ability to bear children, sexuality, and presumed promiscuity, sex work, or drug use even though most had been infected while in a heterosexual and monogamous relationship. The authors also reported a layering effect of stigma for women who were using illegal drugs. In addition to the ramifications of stigma in general, one ethnographic study gave additional insight into how stigma impacts women: it increases reluctance to seek health care, creates barriers to medication adherence, and limits social interaction and social support (Carr & Gramling, 2004). Another study showed that as stigma increased in African American women with HIV, level of disclosure and psychological functioning decreased (both p < .01). Additionally, for individuals with high levels of disclosure, an increase in perceived stigma was associated with an increase in psychological distress (p < .01; Clark et al., 2003). These gender differences warrant an examination of how, if at all, men and women experience stigma differently, including the degree of perception of stigma and the different ways stigma is affected by other factors like health status and social support.

Higher incidence rates in particular populations may exacerbate existing health disparities. Parker and Aggleton (2003) argued that the existing inequalities of class, gender, race, and sexuality might, in fact, have fed stigma, and that stigma, in turn, strengthened those inequalities. Therefore, the theorized model includes race, history of IDU, and exposure category as covariates in order to investigate and control for the potential effect of these variables on social support, health status, and stigma.

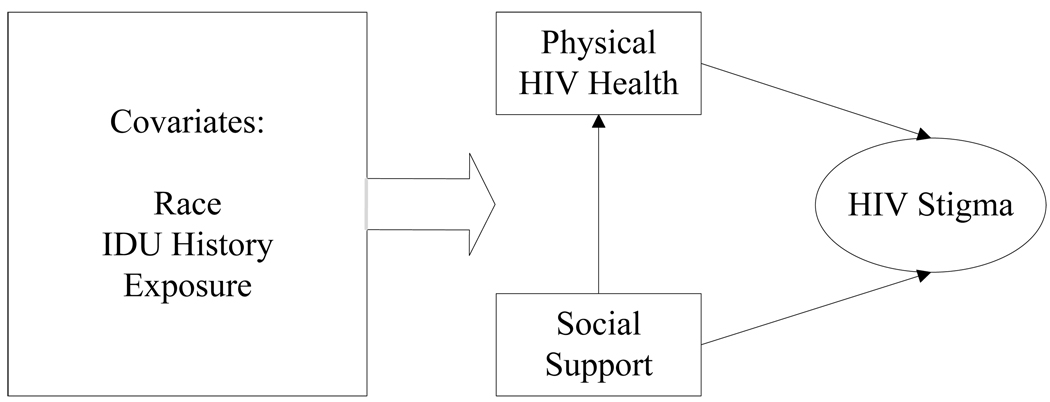

Stigma is a social construct, unique for each individual, highly variable across cultures, and dynamically changing throughout the illness trajectory (Taylor, 2001). The conceptual model for this study included salient demographic and personal characteristics (e.g. exposure category and history of IDU), and the constructs of perceived social support and perceived health status. Functional health status—defined by the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse (2004) as “a measure of an individual's ability to perform normal activities of life” (Outcomes section, para 3)—was once studied as a predictor of morbidity and mortality. Declines in functional health status may impact various areas, including physical mobility, role functioning, and activities of daily living. In our study, health status was conceptually measured as functional health status. Research has shown a relationship between health status, especially current symptoms, and stigma (Buseh, Kelber, Stevens, & Park, 2008; Galvan, Davis, Banks, & Bing, 2008). Perceived social support refers to the network of people and resources available to an individual. Specifically, social support refers to the system of family, friends, neighbors, and community members who are available to provide psychological, physical, and financial help (Cohen, Mermelstein, Kamarck, & Hoberman, 1985). This model allows for an examination of (a) the association between social support and physical health status with HIV/AIDS stigma, after controlling for specific socio-demographic factors, and (b) the differences in men and women living with HIV. The theorized model is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model.

Methods

Study Design

This study was a secondary analysis of selected baseline data from, a behavioral randomized clinical trial testing the efficacy of a nurse-delivered telephone intervention designed to promote and sustain antiretroviral medication adherence in PLWH (Adherence to Protease Inhibitors, R01 NR04749). In order to be eligible for the parent study, participants had to have been 18 years of age or older, able to speak and read English, free from HIV-related dementia as evidenced by assessment using an established HIV dementia instrument (Power, Selnes, Grim, & McArthur, 1995), on HIV medications, self-administering medication, and not living with a current participant in the study. Participants were recruited from western Pennsylvania and eastern Ohio. All participants provided informed consent prior to enrollment in the study. Approval for the study was obtained from an appropriate institutional review board.

Sample

Two hundred fifteen participants were originally included in the project. Of the original sample, 92.6% reported their race as either White or African American/Black; the remaining 17 participants fell into seven other race categories or were missing racial data. Because this analysis used race a covariate and an adequate number was needed for each group, those 17 subjects were excluded. This sample reflected the demographic composition in the urban area in which the study was conducted. Analysis of incomplete data from all of the variables specified in this research study (including covariates), using the generalized least squares (GLS) combined test of homogeneity of means and covariances, indicated that data were missing completely at random, χ2(198) = 176.412, p = .055, thereby allowing for deletion of those subjects with missing data (Kim & Bentler, 2002), omitting 15 (7.6%) of the participants and leaving an effective sample size of 183 with complete data for analysis. The sample of 183 subjects was 62.8% White and 37.2% was African American/Black. The sample was mostly male (64.5%), had a mean age of 40.68 years (SD = 7.8), and had an average of 13.17 years of education (SD = 2.6). Fifty-nine percent of the sample was unemployed or not working due to disability. The average CD4+ T cell count was 489.67 cells/mm3 (SD = 360.0) and ranged from 5 to 2,270 cells/mm3; 45.4% of the sample self-reported a detectable viral load.

Differences were detected between men and women on several variables. There were significantly more African American/Black women than men in the sample, χ2(1) = 7.997, p =.005. Men and women were significantly different in regard to two HIV exposure group categories: the gay/bisexual group had significantly more men, χ2(1) = 45.719, p < .001, while the IDU category had significantly more women, χ2(1) = 3.951, p =.047. Also, more men reported working full or part time, χ2(1) = 9.192, p = .041 and fewer men than women were currently married or living with a partner, χ2(1) = 6.711, p = .010. Women reported a significantly lower number of total years of education than men, F(1,181) = 9.977, p = 002. The groups did not differ in regard to age, race, CD4+ T cell count, detectable viral load, history of IDU, or other exposure (which included occupational, transfusion-related, combined or unknown exposure).

Procedure

The data used in this study were obtained during the baseline data collection session for all participants. At the first visit, subjects gave informed consent, were screened for inclusion, and then enrolled into the study. The subjects returned for baseline data collection 30 days later, at which time the instruments used in our study, as well as all other parent study measures were administered. Data were collected prior to randomization to study treatment groups in the parent study for HIV medication adherence.

Measures

Sociodemographics and HIV health history

Sociodemographic and HIV health history information were collected using the Center for Research in Chronic Disorder (CRCD) Sociodemographic Questionnaire, a self-report tool developed by investigators at the CRCD at the University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, and the Medical Record Review, a study-designed medical record abstraction tool that included questions about age, years of education completed, income level, health insurance, ethnicity, history of IDU, exposure group, and gender. Self-report of CD4+T cell count, viral load (dichotomized to detectable/undetectable), AIDS diagnosis (defined as CD4+ T cell count < 200 cells/mm3), and history of opportunistic infections were also collected. Self-report measurement has been shown to be a valid and reliable measure for CD4+ T cell count and for viral load when it is dichotomized between detectable and undetectable (Kalichman, Rompa, & Cage, 2000). For testing the model, exposure category was represented using three dummy coded variables: heterosexual, gay/bisexual, IDU, and other (i.e., combined, occupational, transfusion-related, or unknown exposure); heterosexual exposure was set as the reference group.

HIV-related stigma

Stigma, the dependent variable, was measured using the HIV-related Stigma Scale (Berger, Ferrans, & Lashley, 2001). This 40-item tool has 4 subscales: personalized stigma, disclosure concerns, negative self-image, and concern over public attitudes toward PLWH. Personalized stigma is the experience of actually being rejected or perceiving rejection based on HIV status. Disclosure concerns refer to whether or not individuals tell others about their diagnosis. Negative self-image is whether or not having HIV makes one feel badly about oneself such as shame or feeling “unclean.” Concern over public attitudes toward PLWH includes discrimination, employability, and the reactions of the public to PLWH. All items are answered using a 4-point Likert scale (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree). The 4 subscales were used individually as the observed variables to estimate the latent variable of HIV Stigma used in the model. The alphas validity coefficients for the sub-scales range from .90–.93 and for the total scale is .96 (Berger et al., 2001). In our study, the Cronbach’s α for the scale was .954 in the entire sample, .955 for women and .948 for men.

HIV physical health

Health status was measured using the Physical Component Score (PCS) of the Medical Outcomes Study HIV (MOS-HIV) Health Survey, a health status measure that has been used extensively with PLWH (Wu, Rubin, & Mathews, 1991). The MOS-HIV, distributed by the Medical Outcomes Trust, contains 35 items that cover 11 dimensions of health. The 10 dimensions were included in the PCS: physical functioning, mental health, health distress, quality of life, cognitive functioning, vitality, pain, role functioning, social functioning, and general health. The health transition dimension that compared current health to health 4 weeks ago was not included in this summary score. The PCS is scored using a method that transforms the scores to a standardized scale or T-score (M = 50, SD = 10). Mean PCS scores above or below 50 can be interpreted as having better or worse physical health-related quality of life than the HIV-infected patient sample from which the summary measures were developed; patients reporting worsening health status had significantly lower mean PCS scores than patients reporting stable or improving health status (Revicki, Sorensen, & Wu, 1998). In our study, the Cronbach’s α for the entire scale was .952 in the whole sample, .948 for women, and .950 for men.

Social support

Social support was measured using the total score of the Interpersonal Support Evaluation List (ISEL; Cohen et al., 1985). The ISEL was designed to assess the perceived availability of four separate functions of social support as well as providing an overall support measure. The ISEL has four 10-item subscales. The tangible subscale is intended to assess perceived availability of material aid; the appraisal subscale assesses the perceived availability of an individual to talk to about her/his problems; the self-esteem subscale assesses the perceived availability of a positive comparison when comparing self to others; and the belonging subscale assesses the perceived availability of people with whom one can do things. This 40-item tool focuses on available resources. Higher scores suggest higher social support. Cohen et al. (1985) reported alpha coefficients of .88–.90 for the entire scale. In our study, the Cronbach’s α for the total scale was .957 in the entire sample, .948 for women, and .961 for men.

Data Analysis

Bivariate analyses were conducted to examine the independent relationships between gender and selected socio-demographic factors and HIV-health history information. This same analysis was used to examine the relationships between stigma and the demographic and health history variables. Independent two sample t-tests were used for continuous variables, and χ2 tests of independence were used for categorical variables. Gender differences in HIV physical health status, social support, and HIV-related stigma were evaluated as mean differences using analysis of variance.

Multi-Group Structural Equation Models

A theoretical model, based on Goffman’s (1963) conceptualization of stigma and literature relevant to HIV-related stigma, was developed specifying the relationship between specific demographic variables, physical health status, social support, and stigma (see Figure 1). The specific socio-demographic variables, health status, and social support were each linked to stigma to statistically control for these relationships. Social support was also used to predict health status, while the socio-demographic variables each predicted health status and social support.

EQS (Version 6.1, Multivariate Software, Inc., Encino, CA) was used to test the goodness of fit of the hypothesized model. Structural equation modeling was estimated using maximum likelihood with robust adjustments. The model was then evaluated using fit indexes and Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square statistic with cut-off criteria as recommended by Hu and Bentler (1998, 1999). These criteria specify Comparative Fit Index (CFI) values ≥ .95, McDonald’s (MFI) ≥ .90 and root mean squared error of approximation (RMSEA) close to .06 as indicative of a good fitting model. Hu and Bentler (1998, 1999) recommended evaluation of models with a two-index strategy that included MFI for samples with fewer than 250 subjects. Using z-tests, as is standard in structural equation modeling, model parameters were considered to be statistically significant at significance level of 05.

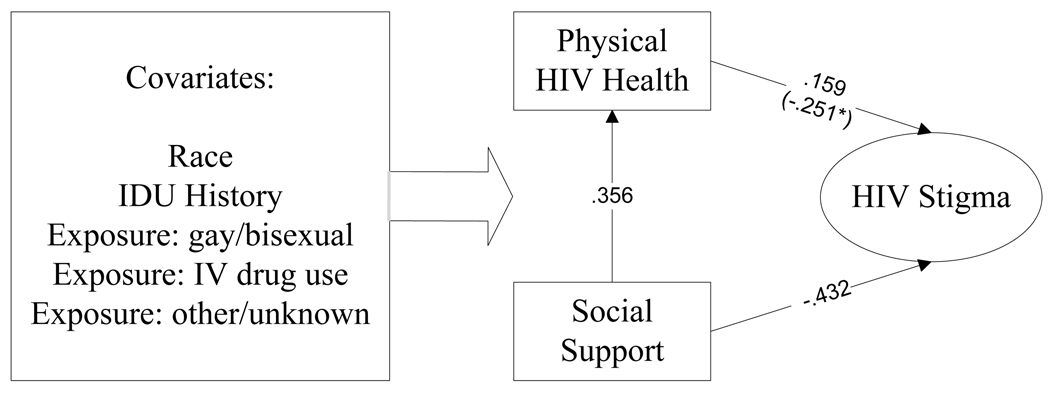

First, the theoretical model was tested with the entire sample and for each gender, separately, in order to identify the correct structural model to compare the two groups. The goodness of fit and model parameters were evaluated per the criteria specified above. For the covariates predicting health status and social support, only those parameters shown to be statistically significant for at least one of the two genders were included in the model. All covariates were free to correlate. The resulting modified model was then used to test the differences between men and women (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Unstandardized Multi-Group Structural Equation Modeling Path Analysis Results for Males and Females.

Multi-group structural equation modeling (MSEM) was used to test for gender differences, whereby two structural equation models modified to include significant relationships, as shown in Figure 2, were estimated and evaluated simultaneously. Initially, all parameters for men and women were unconstrained or freely estimated (i.e., the parameters are allowed to be different between genders); this is the “baseline” model. Then, all factor loadings for the stigma factor were constrained to test for measurement invariance, in order to test whether or not stigma, as measured by the 4 subscales, was measuring the same factor or construct for both men and women. Next, structural paths including measurement were constrained, testing for measurement and structural invariances, which would indicate whether or not the model was the same for men and women. Subsequently, any significant constraints were freed (i.e., were allowed to be different for each gender based on LaGrange multiplier tests). The models with free parameters were compared against the baseline model by computing a chi-square difference test (Δχ2).

Results

Stigma and Mean Comparisons

Men and women did not have significantly different scores on the physical component scale or the social support total scale. However, there were significant differences between men and women on all of the subscales for the HIV stigma scale. Specifically, women had significantly higher scores than men for personalized stigma, F(1,181) = 15.686, p < .001, disclosure, F(1,181) = 12.136, p = .001, negative self-image, F(1,181) = 10.793, p = .001, and perceptions of public attitudes about people with HIV, F(1,181) = 25.460, p < .001.

Multi-group Structural Equation Model Analysis

When estimated with women only, the theorized model produced a very good fit, Satorra-Bentler χ2(28, N = 65) = 36.486, p = .131 CFI = .966, MFI = .937, RMSEA = .069. In women. physical health was significantly predicted by social support (B=.334, p = .003) and exposure gay/bisexual (B=.156, p < .001). In this analysis, Beta (B) represents the standardized coefficients. Social support was predicted significantly by race (B=.302, p = .010), suggesting that African Americans/Blacks had more social support. HIV-related stigma was significantly negatively predicted by physical health (B=−.252, p = .002) and social support (B=−.418, p < .001).The theorized model predicted 44.5% of the variance in HIV-related stigma for women. When estimated with men only, the model produced only an adequate fit, Satorra-Bentler χ2(28, N = 118) = 52.848, p = .003, CFI = .949, MFI = .900, RMSEA = .087. In men, physical health was significantly predicted by social support (B=.392, p < .001) and IDU history (B=.194, p = .036). Social support was predicted significantly by exposure to gay/bisexual (B=.231, p = .010). Stigma was significantly negatively predicted by social support (B=−.442, p < .001). The model did, however, predict 27.4% of the variance in HIV stigma for men.

Overall, the baseline model demonstrated a good fit for the entire sample, including men and women, SB χ2(56, N =183) = 89.761, p = .003, CFI = .955, MFI = .912, and RMSEA = .082. The baseline model demonstrated measurement invariance across genders, Δ χ2 (3) = 1.40, p = .707; however, there was a difference in the structural relationships between genders, indicating that one or more of the structural parameters were different between men and women. LaGrange Multiplier (LM) tests suggested that the removal of the following constraints would significantly improve the model: health-status-predicting stigma, LM χ2(1) = 8.625, p = .003; race predicting social support, LM χ2(1) = 3.902, p = .048; and IDU history predicting health status, LM χ2(1) = 5.070, p = .024. Table 1 provides the complete results of the multi-group testing. All other parameters demonstrated no statistical difference between men and women.

Table 1.

Comparison of Tested Models

| Model | SBχ2 | df | CFI | RMSEA | Δ χ2 | Δdf | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 89.761 | 56 | .955 | .082 | |||

| Measurement Invariant | 90.62 | 59 | .958 | .077 | 1.40 | 3 | .707 |

| Measurement & Structural Invariant | 116.18 | 66 | .933 | .092 | 25.24 | 10 | .005 |

| Final Model* | 97.42 | 63 | .954 | .078 | 8.01 | 7 | .332 |

Constraints released: health status predicting stigma; IDU history predicting physical health, race predicting social support

The final model also demonstrated a good fit between men and women, SBχ2 (63, N = 183) = 97.418, p = .004, CFI = .954, MFI = .910, and RMSEA = .078. In the final model there was a significantly more negative prediction of physical health by IDU history for females than males (B=.145 vs −.151, respectively). There was significantly more positive prediction of social support by race for females than males (B=.022 vs .315, respectively). There was significantly more negative prediction of stigma by social support for females than males (B=−.251 vs .159, respectively). In the final model, when controlling for the covariates, there was a significant positive prediction of physical health by social support and a significant negative prediction of stigma by social support for both men and women. Figure 2 illustrates the final model with unstandardized results. Table 2 provides standardized and unstandardized results for all of the parameters.

Table 2.

Standardized and Unstandardized Structural Coefficients for the Final Model by Gender

| Men | Women | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameter | Standardized | Unstandardized | Standardized | Unstandardized |

| Race-Stigma | −.054 | −.061 | .029 | .034 |

| IDU History-Stigma | .046 | .052 | −.122 | −.144 |

| Gay/Bisexual-Stigma | −.029 | −.033 | .112 | .132 |

| IDU Exposure Group- Stigma |

.196 | .222 | −.074 | −.087 |

| Other Exposure Group- Stigma |

.056 | .063 | −.020 | −.024 |

| IDU History-Health Status | .145 | .147 | −.151 | −.148 |

| Gay/Bisexual-Health Status | −.016 | −016 | −.016 | −.016 |

| Race-Social Support | .022 | .022 | .315 | .308* |

| Social Support-Health Status | .356 | .357* | .356 | .357* |

| Health Status-Stigma | .159 | .178* | −.251 | −.302* |

| Social Support-Stigma | −.432 | −.485* | −.432 | −.521* |

Note. IDU – injection drug user

for unstandardized coefficients denotes significant at p < .05

Discussion

This exploration of Goffman’s (1963) theoretical model offers insight into understanding the relationship between gender, health status, social support, and HIV-related stigma, as the modified model predicts 44% of the variance in HIV stigma for women and 27.4% of the variance for men. Additionally, the model may offer a new perspective about the theoretical assumptions about race, homosexuality, and drug use in perceived stigma for PLWH, especially for those individuals who are actively engaged in care, as individually these factors were not predictors of HIV stigma in this population.

Not surprisingly and as suggested by existing literature, the data from this sample demonstrate a link for both genders between social support and stigma, whereby social support negatively predicts stigma for men and women (Dowshen, Binns, & Garofalo, 2009; Galvan et al., 2008; Smith, Rossetto, & Peterson, 2008). These results indicate that women may experience stigma at a level significantly higher than men, even with comparable levels of social support and health status. For women, health status needs to be considered as a possible predictor of stigma. This study supports previous work highlighting the unique needs of women living with HIV, specifically those related to stigma (Carr & Gramling, 2004; Sandelowski et al., 2004; Wingood et al., 2007).

Examining stigma in HIV differs significantly from examining stigma related to other infectious diseases in history for a number of reasons. First and foremost, the circumstances are in real time and the world is dealing with the epidemic on a daily basis. Secondly, stigma is a recognized and organized area of study and data are routinely collected on stigma and its effects on health outcomes. One might even argue that the development of HIV-related stigma is a well-documented and often-referred-to evolution. Third, in response to research and public outcry, programs exist and are being put in place every day to address stigma and its effect on the individual, the family, and the community. In the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care Core Curriculum for HIV/AIDS Nursing the heading “social isolation and stigma” has more than 35 notations, and offers interventions addressing such issues as shame, identity, and avoidance (Kirton, 2003). Despite this, and the relatively rapid accumulation of knowledge about the disease, its progression, and its transmission, PLWH report feeling stigmatized, rejected, and isolated because of their HIV status. For example, a study released in 2002 on HIV and stigma reported that 1 in 5 Americans were afraid of someone with HIV (Herek et al., 2002). This finding begs the question: What are the specific circumstances that have allowed for the realization and maintenance of such a significant degree of disease-related stigma?

The lack of significant prediction of stigma by race, history of IDU, or exposure category individually is also an important consideration for researchers and clinicians, as these are traditionally considered to be stigmatizing issues and are an important component of Goffman’s (1963) original model. The results from this study suggest that health care providers may have an opportunity to intervene on stigma, and that social environment and health status may have more of an effect on perceived stigma for the individual than addiction or non-modifiable socio-demographic factors.

Limitations

The most notable limitation in this study is the self-selected sample, and, therefore, the limited ability to generalize these results to the greater population. All of the participants were taking antiretroviral medications, and were, therefore, under the care of a health care provider. Additionally, this sample came from a longitudinal study on medication adherence, denoting another level of engagement in care and self-management. Obviously such a population could differ significantly from a group of individuals who were less engaged in care and less willing to participate in studies. Additionally, the study was a secondary data analysis, and the primary research questions were not specifically related to stigma. Finally, the study did not include several important variables that might influence disease-related stigma, specifically age, income, length of time since original diagnosis, and marital status. The study warrants replication with another sample, ideally accessing a population more reticent to participate in research and, potentially, less engaged in care. Despite these limitations, the study results do offer insight into potential areas for interventions to address stigma.

Further study in this area needs to include continued research into how the experience of HIV stigma differs between genders. Our results indicated that these relationships warrant further investigation to identify potential intervention points, and that researchers may need to look at different explanatory mechanisms for men and women. It is also important to note that the final model tested in this study was modified from the one originally hypothesized, and that, therefore, there must be additional confirmatory work with the model. It may also be important to consider how stigma is experienced differently based on ethnic or racial background, as there is some evidence to suggest that the experience may vary, due to either cultural or measurement issues (Rao, Pryor, Gaddist, & Mayer, 2008).

Finally, this study allowed researchers to control for the effects of socio-demographic covariates, but there needs to be more research into the layering effect of the covariates: for example, how women of color who also have a history of drug use perceive the stigma in their lives. This may require some re-conceptualization of stigma and the way stigma manifests and operates within particular populations (Mahajan et al., 2008). Researchers have suggested a unique methodology for quantifying the phenomenon of layering that has potential usefulness in such an investigation (Reidpath & Chan, 2005).

Conclusion

HIV stigma still exists and its deleterious effects are seen in the long-term management of the disease, but researchers and clinicians may be able to play a more important role in reducing the perceived stigma than previously recognized. Such work would require continued study of the personal experience of HIV stigma for PLWH and the design of interventions that recognize and incorporate factors related to stigma and acknowledge the differences in perceived stigma between men and women.

Acknowledgments

The authors appreciate the contributions of the staff of the Managing Medications Project at the University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, as well as the editorial assistance of Dr. Denise Charron-Prochownik. The authors also wish to thank the study volunteers for their participation.

This study was funded by National Institute for Nursing Research (NINR) of the National Institute of Health (R01 NR04749 and 2R01 NR04749). The author(s) report(s) no real or perceived vested interests that relate to this article (including relationships with pharmaceutical companies, biomedical device manufacturers, grantors, or other entities whose products or services are related to topics covered in this manuscript) that could be construed as a conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Alison M. Colbert, Duquesne University School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, PA.

Kevin H. Kim, University of Pittsburgh School of Education, Pittsburgh, PA.

Susan M. Sereika, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, PA.

Judith A. Erlen, University of Pittsburgh School of Nursing, Pittsburgh, PA.

References

- Berger BE, Ferrans CE, Lashley FR. Measuring stigma in people with HIV: Psychometric assessment of the HIV stigma scale. Research in Nursing and Health. 2001;24(6):518–529. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. doi: 10.1002/nur.10011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buseh AG, Kelber ST, Stevens PE, Park CG. Relationship of symptoms, perceived health, and stigma with quality of life among urban HIV-infected African American men. Public Health Nursing. 2008;25(5):409–419. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.2008.00725.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr RL, Gramling LF. Stigma: A health barrier for women with HIV/AIDS. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2004;15(5):30–39. doi: 10.1177/1055329003261981. doi:10.1177/1055329003261981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance report. 2002;14 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2002report/pdf/2002SurveillanceReport.pdf.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. A glance at the HIV epidemic. Rockville, MD: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV/AIDS surveillance report 2007. 2009;19 Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/surveillance/resources/reports/2007report/pdf/2007SurveillanceReport.pdf.

- Chin J, editor. Control of communicable diseases manual. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Clark HJ, Lindner G, Armistead L, Austin BJ. Stigma, disclosure, and psychological functioning among HIV-infected and non-infected African-American women. Women & Health. 2003;38(4):57–71. doi: 10.1300/j013v38n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen S, Mermelstein R, Kamarck T, Hoberman H. Measuring the functional components of social support. In: Sarason IG, Sarason BR, editors. Social support: Theory, research and application. The Hague, Holland: Martinus Nijhoff; 1985. pp. 73–94. [Google Scholar]

- Crystal S, Sambamoorthi U, Moynihan PJ, McSpiritt E. Initiation and continuation of newer antiretroviral treatments among Medicaid recipients with AIDS. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2001;16(12):850–859. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2001.01025.x. Retrieved from http://www.springerlink.com/content/226322j52711361j/fulltext.pdf?page=1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowshen N, Binns HJ, Garofalo R. Experiences of HIV-related stigma among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2009;23(5):371–376. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0256. doi:10.1089/apc.2008.0256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fortenberry JD, McFarlane M, Bleakley A, Bull S, Fishbein M, Grimley D, Stoner BP. Relationships of stigma and shame to gonorrhea and HIV screening. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(3):378–381. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.378. Retrieved from http://www.ajph.org/cgi/reprint/92/3/378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frable DE, Wortman C, Joseph J. Predicting self-esteem, well-being, and distress in a cohort of gay men: The importance of cultural stigma, personal visibility, community networks, and positive identity. Journal of Personality. 1997;65(3):599–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00328.x. doi: 0.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan FH, Davis EM, Banks D, Bing EG. HIV stigma and social support among African Americans. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2008;22(5):423–436. doi: 10.1089/apc.2007.0169. doi:10.1089/apc.2007.0169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of a spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM. AIDS and stigma. American Behavioral Scientist. 1999;42(7):1102–1112. [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Capitanio JP, Widaman KF. HIV-related stigma and knowledge in the united states: Prevalence and trends, 1991–1999. American Journal of Public Health. 2002;92(3):371–377. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.3.371. Retrieved from http://www.ajph.org/cgi/reprint/92/3/371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Capitanio JP, Widaman KF. Stigma, social risk, and health policy: Public attitudes toward HIV surveillance policies and the social construction of illness. Health Psychology. 2003;22(5):533–540. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.22.5.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herek GM, Widaman KF, Capitanio JP. When sex equals AIDS: Symbolic stigma and heterosexual adults' inaccurate beliefs and sexual transmission of AIDS. Social Problems. 2005;52(1):15–37. doi: 0.1525/sp.2005.52.1.15. [Google Scholar]

- Holzemer WL, Human S, Arudo J, Rosa ME, Hamilton MJ, Corless I, Maryland M. Exploring HIV stigma and quality of life for persons living with HIV infection. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2009;20(3):161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2009.02.002. doi:10.1016/j.jana.2009.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Fit indices in covariance structure modeling: Sensitivity to underparametereized model misspecification. Psychological Methods. 1998;3(4):424–453. [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling. 1999;6(1):1–55. [Google Scholar]

- Kalichman SC, Rompa D, Cage M. Reliability and validity of self-reported CD4 lymphocyte count and viral load test results in people living with HIV/AIDS. International Journal of STD and AIDS. 2000;11(9):579–585. doi: 10.1258/0956462001916551. doi:10.1258/0956462001916551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KH, Bentler PM. Tests of homogeneity of means and covariance matrices for multivariate incomplete data. Psychometrika. 2002;67(4):609–624. doi:10.1007/BF02295134. [Google Scholar]

- Kirton C. ANAC’s core curriculum for HIV/AIDS nursing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lally MA, Montstream-Quas SA, Tanaka S, Tedeschi SK, Morrow KM. A qualitative study among injection drug using women in Rhode Island: Attitudes toward testing, treatment, and vaccination for hepatitis and HIV. AIDS Patient Care & STDs. 2008;22(1):53–64. doi: 10.1089/apc.2006.0206. doi:10.1089/apc.2006.0206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan AP, Sayles JN, Patel VA, Remien RH, Sawires SR, Ortiz DJ, Coates TJ. Stigma in the HIV/AIDS epidemic: A review of the literature and recommendations for the way forward. AIDS. 2008;22 Suppl 2:S67–S79. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327438.13291.62. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000327438.13291.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinnis KA, Fine MJ, Sharma RK, Skanderson M, Wagner JH, Rodriguez-Barradas MC, Justice AC. Understanding racial disparities in HIV using data from the veterans aging cohort 3-site study and VA administrative data. American Journal of Public Health. 2003;93(10):1728–1733. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.10.1728. Retrieved from http://www.ajph.org/cgi/reprint/93/10/1728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Quality Measures Clearinghouse. Glossary. 2004 doi: 10.1080/15360280802537332. Retrieved from http://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov/resources/glossary.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Parker R, Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: A conceptual framework and implications for action. Social Science & Medicine. 2003;57:13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power C, Selnes O, Grim JA, McArthur J. HIV dementia scale: A rapid screening tool. Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes. 1995;8(3):273–278. doi: 10.1097/00042560-199503010-00008. Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/jaids/Abstract/1995/03010/HIV_Dementia_Scale__A_Rapid_Screening_Test.8.aspx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D, Pryor JB, Gaddist BW, Mayer R. Stigma, secrecy, and discrimination: Ethnic/racial differences in the concerns of people living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS & Behavior. 2008;12(2):265–271. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9268-x. doi:10.1007/s10461-007-9268-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reece M. HIV-related mental health care: Factors influencing dropout among low-income, HIV-positive individuals. AIDS Care. 2003;15(5):707–716. doi: 10.1080/09540120310001595195. doi:10.1080/09540120310001595195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidpath DD, Chan KY. A method for the quantitative analysis of the layering of HIV-related stigma. AIDS Care. 2005;17(4):425–432. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331319769. doi: 10.1080/09540120412331319769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revicki D, Sorensen S, Wu AW. Reliability and validity of physical and mental health summary scores from the medical outcomes study HIV health survey. Medical Care. 1998;36:126–137. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199802000-00003. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/pss/3767176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandelowski M, Lambe C, Barroso J. Stigma in HIV-positive women. Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 2004;36(2):122–128. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04024.x. doi:10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R, Rossetto K, Peterson BL. A meta-analysis of disclosure of one's HIV-positive status, stigma and social support. AIDS Care. 2008;20(10):1266–1275. doi: 10.1080/09540120801926977. doi:10.1080/09540120801926977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swendeman D, Rotheram-Borus MJ, Comulada S, Weiss R, Ramos ME. Predictors of HIV-related stigma among young people living with HIV. Health Psychology. 2006;25(4):501–509. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.25.4.501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor B. HIV, stigma and health: Integration of theoretical concepts and the lived experiences of individuals. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2001;35(5):792–798. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01912.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vanable PA, Carey MP, Blair DC, Littlewood RA. Impact of HIV-related stigma on health behaviors and psychological adjustment among HIV-positive men and women. AIDS and Behavior. 2006;10(5):473. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9099-1. doi:10.1007/s10461-006-9099-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite KR, Paasche-Orlow M, Rintamaki LS, Davis TC, Wolf MS. Literacy, social stigma, and HIV medication adherence. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2008;23(9):1367–1372. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0662-5. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0662-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingood GM, Diclemente RJ, Mikhail I, McCree DH, Davies SL, Hardin JW, Saag M. HIV discrimination and the health of women living with HIV. Women & Health. 2007;46(2–3):99–112. doi: 10.1300/J013v46n02_07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. UNAIDS/WHO AIDS epidemic update: December 2007. 2007 Retrieved from http://data.unaids.org/pub/EPISlides/2007/2007_epiupdate_en.pdf.

- Wu AW, Rubin H, Mathews WC. A health status questionnaire using 30-items from the medical outcomes study: Preliminary in persons with early HIV infection. Medical Care. 1991;29:786–798. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199108000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]