Abstract

Survey aims A questionnaire was sent to veterinarians in Australia to determine the approximate number of cats presenting for permethrin spot-on (PSO) intoxication over a 2-year period.

Findings Of the 269 questionnaires returned, 255 were eligible for analysis. A total of 207 respondents (81 %) reported cases of PSO intoxication in cats over the previous 2 years. In total, 750 individual cases were reported, with 166 deaths. While all deaths were generally attributable to intoxication, 39 cats were euthanased because owners were unable to pay the anticipated treatment costs. Brands of PSO implicated included Exelpet Flea (and Tick) Liquidator (Mars Australia) (146 respondents), Bayer Advantix (48), Purina Totalcare Flea Eliminator Line-On (19), Troy Ease-On (six) and Duogard Line-On (Virbac) (four); 67 respondents were not able to identify a specific product. Permethrin spot-on formulations were most commonly obtained from supermarkets (146 respondents), followed by pet stores (43), veterinary practices (16), and a range of other sources including produce stores and friends. The majority of intoxication cases reported involved PSOs labelled for use in dogs with specific label instructions such as ‘toxic to cats’. Owners applied these PSO products to their cats accidentally or intentionally. In some cases, exposure was through secondary contact, such as when a PSO product was applied to a dog with which a cat had direct or indirect contact.

Recommendations In the authors' view, because of the likelihood of inappropriate use and toxicity in the non-labelled species, over-the-counter products intended for use in either dogs or cats must have a high margin of safety in all species. Furthermore, PSOs should only be available at points of sale where veterinary advice can be provided and appropriate warnings given. As an interim measure, modified labelling with more explicit warnings may reduce morbidity and mortality.

Introduction

Pyrethrum insecticides were originally derived from extracts of Chrysanthemum flower heads. 1 Their chemical derivatives, known as synthetic pyrethroids (SPs), were developed to improve photostability and to extend the spectrum of pesticidal activity. 2 Synthetic pyrethroids can be combined with a synergist, such as piperonyl butoxide, to enhance insecticidal activity. 3 Both piperonyl butoxide and organophosphorus insecticides interfere with SP metabolism by inhibiting mixed function oxidase and esterase activity, respectively, thereby increasing toxicity to both target pests and mammalian hosts. 3

The most commonly used SP in companion animals is permethrin, a type 1 pyrethroid. Chemically, permethrin has two stereocentres and exists as four possible stereoisomers. Cis isomers are generally more toxic to target pests and mammalian hosts and are metabolised more slowly than trans enantiomers. Synthetic pyrethroids act on the nervous system. The primary mode of action is disruption of voltage-dependent sodium channel function, 3 resulting in depolarisation and repetitive firing of neurons in the central nervous system, especially in the spinal cord.2–4

While SPs are considered very safe in most mammals, the cat is extraordinarily susceptible, for reasons not fully understood. 3 It is believed, but unproven, that cats are more likely to develop toxicosis due to a deficiency in glucuronidyltransferase, which may delay metabolism of the agent.3,5

While synthetic pyrethroids are very safe in most mammals, the cat is extraordinarily susceptible … due in part to a deficiency of glucuronidyltransferase, which may delay metabolism of the agent.

Permethrin is the most commonly reported cause of intoxication in pet cats in both the UK and USA.6–10 Affected cats require hospitalisation and treatment ranging from days to weeks in duration. In a recent retrospective study, the average duration of treatment at the emergency clinic was 24–48 h, although 45% of cases required further treatment from their referring veterinarian for an additional period. 12 A UK study found that convulsions persisted on average for 40 h (range 2 h to 5 days), tremors persisted for 32 h (range 2h to 3 days) and overall recovery took 62 h (range 3 h to 7 days). 10

The highest dose not associated with intoxication of cats and the lowest non-lethal dose have not been documented. However, there is a report of a lethal dermal dose of 100 mg/kg in a cat, 4 suggesting that dog PSO products in Australia contain at least one (and up to eight) lethal dose(s) for a 4 kg cat. Diagnosis is based on exposure history5,6,13–15 and consistent clinical signs. 3

Data on the incidence of pyrethroid toxicity in Australian cats is limited. According to Woo and Lunn, 16 no cases of pyrethroid toxicity in cats were reported to regulatory authorities between January 1995 and May 2003. However, Linnett 17 described 22 cases reported to the Australian Pesticides and Veterinary Medicines Authority (APVMA) from 1995–2006. Dymond and Swift 12 presented a retrospective series of 20 cats treated at an emergency clinic from October 2004 to June 2005 following the application of PSOs labelled for use in dogs. This chronology suggests that PSO exposure may be emerging as an important cause of intoxication of cats in Australia.

A survey was conducted to better understand the extent and nature of PSO intoxication of cats and to develop recommendations to mitigate the likelihood of exposure.

How Does Toxicity Manifest?

Hallmarks of permethrin toxicity are muscle fasciculations and whole body tremors. 5 Tremors are typically coarse, and sometimes progress to generalised motor seizures, coma and death. 11 Other clinical signs include ataxia, ptyalism, mydriasis, hyperthermia, hyperaesthesia, vomiting and dyspnoea. 12

Materials and Methods

An ad hoc pilot survey of practitioners was conducted in September 2008 by two of the authors (AS and RM) at regional Australian Veterinary Association (AVA) meetings and by phone and e-mail to provide preliminary data to guide the framing of questions to be included in a subsequent questionnaire.

Questionnaire Distribution

A short questionnaire (Fig 1) was distributed with the September/October 2008 issue of the Control and Therapy Series of the Centre for Veterinary Education (CVE) of The University of Sydney. This publication was mailed to approximately 2000 veterinarians and veterinary practices throughout Australia, with particular focus on New South Wales (NSW) and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), where the majority of CVE members are located. Respondents had the option of photocopying and completing the survey and returning it by post or facsimile. Stamped, self-addressed envelopes were not provided. From September through November 2008 respondents could also visit the CVE website (www.cve.edu.au), download the form and e-mail it to one of the authors (RM). The survey was subsequently e-mailed to all veterinarians on the CVE's database, on two occasions, 2 weeks apart. The second e-mail specifically urged veterinarians who had not seen cases to complete the survey.

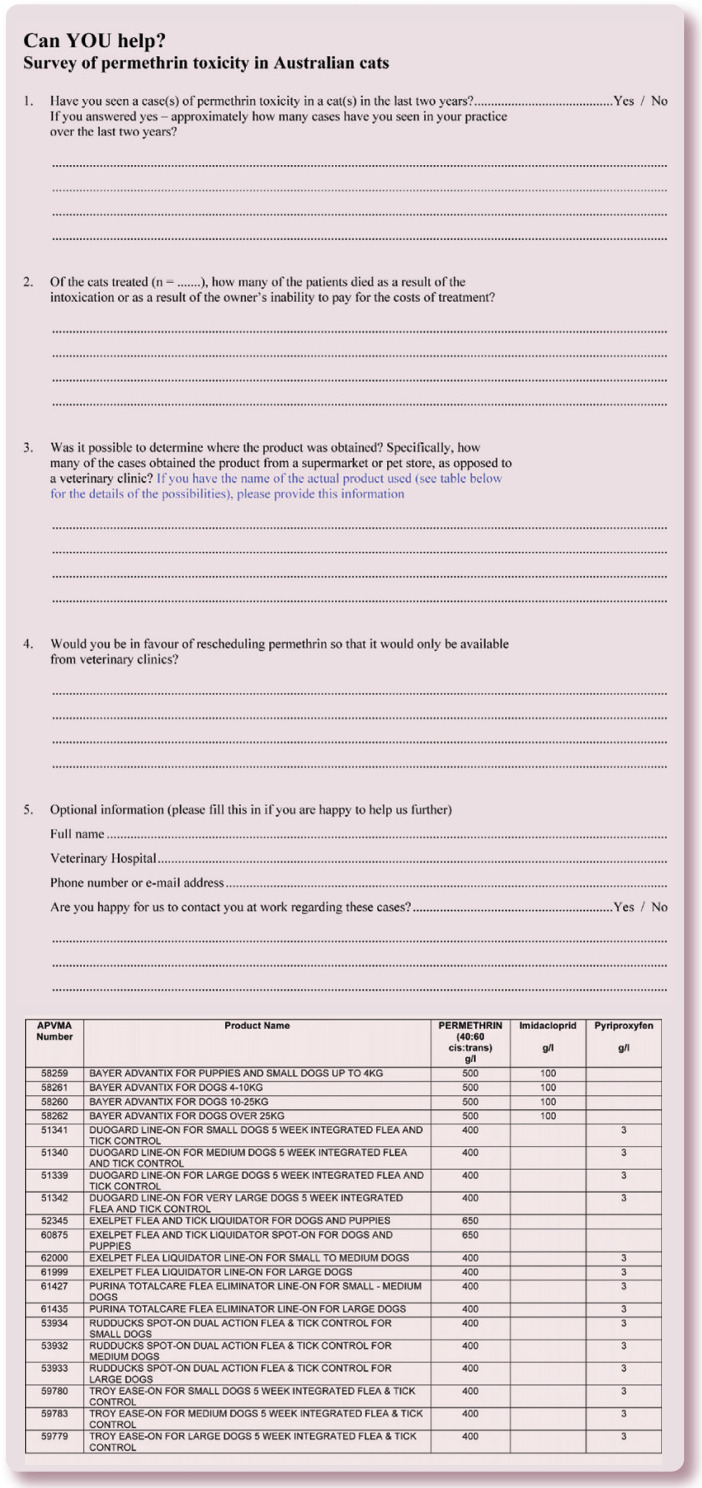

Fig 1.

Survey questionnaire (including list of approved PSO products available in Australia) distributed to veterinary practices via the Centre for Veterinary Education 's (CVE 's) Control and Therapy Series publication, and by repeated e-mails from the CVE and the Australian Small Animal Veterinary Association. The questionnaire was also available on the CVE 's website

Members of the AVA were informed of the survey via a link on the AVA website and a link in the AVA e-newsletter. In addition, members of the Australian Small Animal Veterinary Association (ASAVA) were e-mailed the survey. The Murdoch University Centre for Continuing Education in Western Australia e-mailed the survey to all its members, while several private referral centres e-mailed or faxed the survey to clinics for which they had relevant contact information. The great majority of veterinary practices across Australia were thus provided with the survey via one route or another.

Content and Analysis

The questionnaire asked whether veterinarians had seen one or more cases of permethrin intoxication in cats in the last 2 years. If the reply was affirmative, respondents were asked to record the number of cases seen over that period. They were then asked to state how many of the cats died, either as a result of intoxication, or due to the owner 's inability to pay for treatment. Respondents were asked to state, if available, the name and source of the product, and where it was obtained from (supermarket, pet store, veterinary clinic, etc). A list of approved PSO products was included as part of the survey form to assist colleagues to provide precise information. Respondents were then asked if they were in favour of rescheduling permethrin products so that they would only be available from veterinary practices where suitable warnings concerning their use could be provided. Finally, they were asked to provide practice contact information and state whether they would be prepared to provide further information at a later date. In cases where data supplied was incomplete, the authors obtained more complete information by contacting the veterinarians individually, by e-mail, facsimile, post or phone.

Permethrin is the most commonly reported cause of intoxication in pet cats in both the UK and USA.

All replies up until 7 March 2009 were included. Information was entered into a spreadsheet (Excel; Microsoft Office 2007), which permitted descriptive and graphical treatment of the data. Additionally, comments made by respondents were recorded, as they often provided unprompted insights arising from the management of cases in general, emergency and specialist practice. In relation to the source of product and type of product implicated, data was considered for each respondent, rather than for each case, as it was not always possible to discern precise information about every individual case from some respondents' comments.

Using the postcode of each veterinary practice, the number of cases per postcode was mapped by joining the data with a polygon layer of Australian postcodes (Australian Bureau of Statistics 2006; www.abs.gov.au/ AUSSTATS) within a geographic information system (ArcMap 9.1. ESRI, Redlands CA). To look for potential associations between the occurrence of PSO intoxication and socioeconomic status, data was intersected with indices of relative socioeconomic advantage, economic resources, education and occupation.

Points of Sales Inspection

In addition to the survey, the authors inspected a convenience sample of local supermarkets and pet stores to gather information on the range of products available, how these products are presented for sale, and the type of information provided to purchasers by staff at pet stores and pet barns. A list of approved PSO products and label information was obtained from the database (PUBCRIS) of the APVMA (www.apvma.gov.au).

Results

Number of Survey Respondents as a Proportion of Practising Clinicians

According to a recent study, there were 7510 veterinarians working in Australia in 2006. 18 A total of 269 practitioners or practices responded to the survey. Fourteen responses did not meet the criteria for inclusion in the analysis: eight were from countries other than Australia, three did not provide contact details, data was inconsistent in one report, and two reports described pyrethroid intoxication of cats with non-PSO products (exposure of cat to treated environment in one report, and a permethrin spray and rinse concentrate for dogs and horses in the other). Forty-eight respondents reported that they did not encounter permethrin toxicity in cats over the study period. Thus, 207 reports of PSO intoxication of cats were assessable.

It was not possible to ascertain in most instances whether the response was from an individual or practice, although some larger practices (eg, RSPCA at Yagoona, Sydney) submitted multiple replies by different individuals. All duplicate responses were reconciled before analysis. The majority of responses were submitted via e-mail (n=169), although facsimile (n=77) and mail (n=23) were also used. Among the first half of the completed surveys there was a preponderance of respondents who had encountered cases. Surveys completed later included more practices that had not seen cases. Presumably practitioners were more motivated to respond when they had seen cases recently, although with repeated requests negative findings were submitted.

Quantitative Data from the Survey

A total of 750 cases of PSO intoxication in cats was reported, with 166 deaths, over the 2-year survey period (Table 1). Of the cats that died, 39 were euthanased because owners were not prepared to pay the estimated cost of treatment. Others were treated pro bono, or at a substantially reduced cost, due to the financial hardship of the owners and the willingness of clinicians to try to save the patient.

Table 1.

Summary of key descriptive statistics from the survey

| Number of responses or cases | |

|---|---|

| Survey respondents | 269 |

| Excluded responses* | 14 |

| Practitioners reporting no PSO toxicity | 48 |

| Practitioners reporting PSO toxicity | 207 |

| Cases of PSO toxicity reported | 750 |

| Deaths associated with PSO toxicity reported (cases) | 166 |

| Deaths due to euthanasia (cases) | 39 |

| Died before or despite intervention (cases) | 127 |

Incidents did not occur in Australia, permethrin toxicity not involved, or details unable to be verified. PSO = permethrin spot-on

Of the 255 eligible responses from Australia, 207 (81%) reported cases of intoxication. The remaining 48 (19%) had not seen PSO toxicity during the preceding 2 years. Several of the negative respondents commented that they had seen cases in the past, but not in the relevant time frame. The number of cases seen per respondent varied between one and 20, with larger numbers from referral centres, practices offering 24-h care and practices in less affluent regions. In at least 10 instances, multiple cases (two to six cats or kittens) were presented simultaneously when a single medium or large dog-sized ampoule was divided and the contents applied to multiple cats. Cases were encountered from all states and territories of Australia.

All cases of intoxication of cats by PSOs involved the use of products labelled for use in dogs with specific label instructions not to use in cats. The exception was a cat rinsed in a product called Killyptus, which has a low permethrin concentration and no label warning against use in cats. As this product is not a PSO it was not included in the statistical analysis.

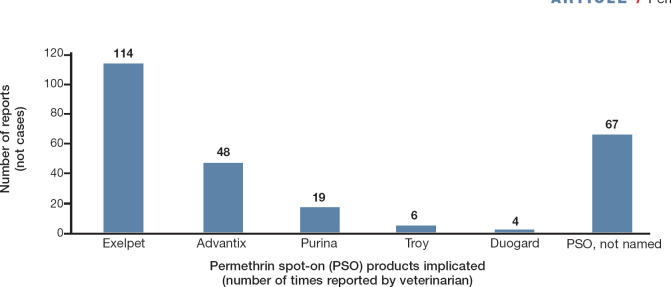

Among the 207 positive respondents, 114 (55%) identified Exelpet Flea (and Tick) Liquidator (Mars Australia), 48 (23%) Bayer Advantix, 19 (9%) Purina Totalcare Flea Eliminator Line-On, six (3%) Troy Ease-On, and four (2%) Duogard Line-On (Virbac) as causes of intoxication. A single case of intoxication after treatment with Permoxin (Dermcare) was reported, but not included in the analysis as it is not a PSO. Products implicated in toxicity could not be specifically identified by 67 (32%) respondents (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

PSO products implicated by respondents in feline cases of permethrin intoxication (see text for product names in full)

A total of 750 cases of permethrin spot-on intoxication in cats was reported, with 166 deaths, over the 2-year survey period.

In at least 10 instances, multiple cases (two to six cats or kittens) were presented simultaneously when a single medium or large dog-sized ampoule was divided and the contents applied to multiple cats.

The source of the PSO product was identified in 214 reported intoxication events from 181 respondents; supermarkets were implicated in 146 reports (68.2%), pet stores in 43 (20.1%) and veterinary practices in 16 (7.5%). Other sources, such as produce stores and friends, accounted for nine cases (4.2%) (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Sources of PSO products implicated by respondents

When asked about rescheduling permethrin products to restrict their sale to veterinarians alone (and thereby exclude supermarkets, pet stores and other outlets), 222 (87.1%) of 255 eligible respondents agreed that such products should be rescheduled, nine (3.5%) were undecided, nine (3.5%) did not respond and 15 (5.9%) disagreed.

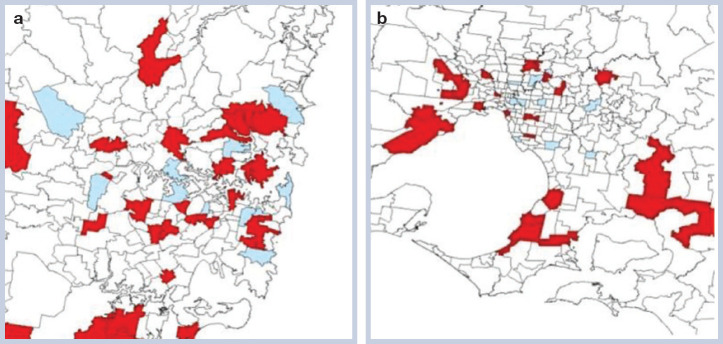

Of the 255 eligible responses from Australia, 237 (92.9%) were geographically coded using postcode information. Cases were reported from 199 postcodes. As expected, most postcodes from which cases were reported were located in NSW (103 cases; 40.4%), Victoria (56 cases; 22%) and Queensland (48 cases; 18.8%). Overall, recorded cases were not clustered (eg, see Fig 4a, the Sydney metropolitan area), although clustering was apparent within Victoria (Fig 4b, Melbourne metropolitan area; Moran 's autocorrelation statistic 0.13). Overall, mapping of recorded cases suggested that the distribution of PSO intoxication was not homogeneous. The number of regions from which veterinarians did not respond to the survey is emphasised by the amount of unshaded territory on the maps.

Fig 4.

Distribution of practices seeing permethrin intoxication cases in Sydney (a) and Melbourne (b) metropolitan areas. Blue signifies postcodes where practices had not seen cases, whereas red signifies postcodes where permethrin intoxication had been reported. Note the large number of unshaded regions for which no data was obtained because of the poor response rate to the survey

An association between indices of socioeconomic status and occurrence of PSO intoxication was investigated using Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance, with a parametric analysis of variance applied to ranks of socioeconomic status. For NSW, there was no difference between postcodes that did or did not report cases, by index of relative socioeconomic disadvantage (F=1.24, P=0.27), economic resources (F=2.06, P=0.15), education and occupation (F=1.30, P=0.26) or usual resident population (F=0.42, P=0.52). Looking just at the Sydney metropolitan area (postcodes <2200), there were similarly no significant associations (index of relative socioeconomic disadvantage F=1.15, P=0.29; economic resources F=1.67, P=0.20; education and occupation, F=0.35, P=0.56; usual resident population F <0.01, P=0.97). Correlations between the number of cases reported per postcode and postcode indices of socioeconomic status were also very poor (Spearman rank correlations 0.04, −0.01, 0.08 and −0.01, respectively) and non-significant (P >0.40). Overall for NSW, there were no significant differences in indices of socioeconomic status between postcodes reporting deaths (yes versus no), using the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance: index of relative socioeconomic disadvantage F=2.29, P=0.13; economic resources F=2.23, P=0.14; education and occupation F=1.28, P=0.26; usual resident population F=0.12, P=0.73).

Qualitative Information from Respondents' Comments

Respondents provided qualitative data on their perceived reasons for feline permethrin intoxication. Many respondents described broadly similar circumstances, with slight variations on the theme. These have been summarised (with some additional commentary) in Table 2; full descriptions are provided in the supplementary data accompanying this article.

Table 2.

Qualitative information on PSO intoxication gleaned from the respondents' comments

| Qualitative information on PSO intoxication gleaned from the respondents' comments |

|---|

| Owners did not always notice the warning symbol on the product label. This was particularly an issue for older owners (due to poor vision?) or where English was not the owner 's first language. Many owners reported that they were applying Frontline (which contains fipronil but not permethrin) irrespective of what product they were applying. Remarkably similar statements were reported in a study from the USA 6 |

| Many owners did not understand that ‘toxic to cats’ or ‘do not use on cats‘ means that cats may die as a result of applying the product |

| Some owners believed that the warning statement was spurious and present only to encourage them to buy feline preparations rather than less expensive canine preparations |

| Some owners used a single large canine applicator to treat many cats, or a dog and several cats; this resulted in multiple intoxications |

| Some owners were given incorrect advice at pet stores, supermarkets or produce stores that the products were safe for cats (despite labelling to the contrary) |

| Some retailers split packages and sold applicators as individual units, making the product available without the outer warning label. This practice is illegal, but appears to be widespread |

| Some owners took cat and dog preparations out of storage to use at the same time, but then used the incorrect applicator (ie, used the dog 's pipette on the cat) |

| Some owners were given products by friends. Because applicators had been removed from their packaging, the warning label was no longer evident |

| Some people used a reduced dose, having already treated their dog(s), believing that a small dose (eg, one drop) would be safe for the cat. One owner applied some to a cat because it was annoying him while he was treating his dog |

| Many owners did not appreciate that close contact with a dog or grooming device (brush, comb, ‘zoom groom’) may provide sufficient exposure to intoxicate a cat in the first 24 h after PSO application. One cat licked the product off its companion dog and became intoxicated. Several in another household were poisoned by being combed after the owner had first used the comb on the family 's dog |

| Many owners did not have the financial resources to pay for treatment of PSO toxicosis, resulting in euthanasia of cats that might otherwise have been saved. Some respondents from emergency centres developed low-cost protocols using decontamination (by washing), deep sedation/anaesthesia with combinations of intravenous phenobarbitone, pentobarbitone or methocarbamol, intermittent bolus fluid therapy and simple nursing, with good results. One such protocol involved a high dose (20 mg/kg) of intravenous phenobarbitone with occasional intravenous boluses of fluids and general nursing |

| Some veterinarians were concerned that products were or could be used maliciously on cats |

Inspection of Supermarkets and Pet Stores

Permethrin spot-on products were readily available from numerous outlets visited by the authors, and were repeatedly observed to be sold with no advice being provided about their potential toxicity to cats. Canine and feline flea products were displayed close together. Purchase of representative products and subsequent inspection revealed that external warning labels were present on all products (Fig 5); however, for many products warnings on the applicator pipettes were either absent or difficult to read, increasing the likelihood of inadvertent use on cats. Advantix had the most comprehensive labelling, including statements about secondary toxicity. No other products were labelled with prominent warnings concerning the danger of secondary intoxication through physical contact or mutual grooming with companion dogs that had been treated, or through common grooming aids. Such warnings were sometimes present on the back of the package in fine print, or in the package insert. Despite efforts by the manufacturer, Advantix was readily available in pet stores, but not in supermarkets.

Fig 5.

Packaging of the most popular PSO product available in Australia. (a) Note that the warning icon on the cardboard box is quite small (arrow). Critically, further warnings do not appear on either the foil packet (b) or the applicator pipette (c)

Supplementary Data

A table of specific comments (in respondents' own words) relating to permethrin intoxication of cats is included in the online version of this article at doi:10.1016/j.jfms.2009.12.002

Discussion

Over the past 20 years there have been many letters, case reports and small case series published in journals and magazines from individuals, veterinary emergency centres and poison information centres concerning the dangers of mistakenly using canine PSOs on cats.5–8,14,15,19–22 It is well accepted that the dog dose provided in applicator tubes or pipettes contains potentially lethal doses for cat(s) and that many deaths have occurred.6,23–25 However, the scale of the problem was unknown until the Environmental Protection Agency identified 158 deaths in the USA between 1998 and 2000, 16 Keck reviewed 500 cases with 42 deaths from January 2001 to September 2002 reported to pharmacovigilance centres in France, 26 and Sutton et al documented 286 cases from the UK. 10

The same situation appeared to exist in Australia. Presentations at the annual scientific meeting of the Australian College of Veterinary Scientists from 2005 onwards in the feline, small animal and critical care streams should have alerted the profession to the extent of this emerging problem. The paper by Linnett, 17 however, may have given a false impression about the safety of these products. Indeed, it was only after publication of a retrospective study by Dymond and Swift, 12 and a follow-up letter by Malik, 27 that attention focused on how and why permethrin intoxication had become more prevalent, with considerations such as the economic downturn and the greater cost of safer ‘premium’ flea and tick products. Informal discussions with manufacturers and retailers have suggested that the proportion of flea products sourced from supermarkets has increased substantially in recent years (R Malik, S Page, A Fawcett, unpublished observations).

The identification of 750 cases of feline PSO intoxication over 2 years, with 166 deaths, significantly exceeds the number of cases reported to the APVMA, suggesting that this toxicity is significantly under-reported. Since 2000, the APVMA has received over 130 reports of PSO toxicity in cats (J Owusu, personal communication, December 2008), revealing an increase in the number of reported cases since the survey of Linnett. 17 Most veterinarians do not report pyrethroid intoxication in cats, either due to time constraints or because the use of the drug in question is ‘off label’ (ie, on the wrong species). The APVMA reporting system states that ‘an adverse experience is an unintended or unexpected effect of a product when used according to the label instructions'; but despite this, reports of off-label product use are assessed. Potential hurdles to better reporting are that veterinarians have experienced difficulty completing adverse drug reaction reports on the designated APVMA website, and that free reporting pads are no longer available.

We believe that the data from our survey has likely underestimated the number of cases by a substantial margin. First, some affected cats probably do not present to a veterinarian, either because they die before treatment is sought or because clinical signs resolve without therapy. Secondly, some veterinarians may not have received the survey or were too busy or insufficiently motivated to complete it. Less than 10% of registered Australian practitioners replied to this survey. Although double counting of cases seen by locums or incorrect case recollection may have affected the quality of some of our data, it is not likely that practitioners would easily forget cases.

Our data indicates that over-the-counter (OTC) sales of simple PSO products from supermarkets, and pet and produce stores account for most cases of intoxication in cats, although PSO products obtained from veterinary practices also accounted for a substantial number of cases. It is clear from the data that many members of the public cannot grasp the concept that a drug available OTC can be safe for use on dogs but lethal when applied to cats. Recent case series have emphasised that some owners do not follow label instructions to give spot-on formulations topically rather than orally. 28 The high incidence of toxicity suggests that current warnings do not spell out the potentially lethal consequences of non-compliance. Finally, there is insufficient warning that secondary intoxication to cats can result from exposure to dogs treated with permethrin, through contact, mutual grooming or via grooming aids.

Permethrin spot-on products cannot be expected to be used safely without expert consultation and advice. But even with the best of advice, these products still pose a substantial risk to feline patients because owners are human and thus prone to error. There is a substantial body of literature describing the ineffectiveness of warning labels.29–33 The latest generation of topical and systemic flea treatments (fipronil, imidacloprid, selamectin, moxidectin, lufenuron, nitenpyram) have very wide margins of safety in cats and dogs, and lend themselves to integration into a programme for flea control that addresses all stages of the flea life cycle. Our view, and that of 90% of survey respondents, is that PSO products should be scheduled as a ‘prescription animal remedy‘ (S4) and no longer be available OTC at non-veterinary outlets. Although it might be argued that we framed the question in a way that was leading, the resoundingly affirmative response suggests it truly represents the opinion of the majority of clinicians.

Over-the-counter sales of simple PSO products from supermarkets, and pet and produce stores account for most cases of intoxication in cats.

We believe that the data from our survey has likely underestimated the number of cases by a substantial margin.

A similar conclusion was reached by Delhaye 34 after assessing the (lack of) effect of label changes on PSO intoxication of cats in France. Similar experience in the USA 6 and UK 35 (including N Sutton, R Tiffin and C Bessant, personal communication, December 2008) suggests that changes in labelling and increased awareness of this problem are unlikely to reduce the incidence of intoxication. Despite changes to labelling in these countries, PSO intoxications continue. Indeed, the number of reported feline exposures to permethrin in the UK has increased with publicity and veterinary awareness, suggesting that cases were previously under-reported. 36 Fatalities were recorded more frequently post-publication, suggesting increased reporting of severe cases. 35

In situations where it is deemed that use of permethrin products in dogs is justified, for example in areas with a high prevalence of the paralysis tick Ixodes holocyclus, prominent and dramatic use of warning labels and/or posters (eg, Fig 6) at the point of sale may offer some protection against inadvertent exposure of cats sharing the environment with treated dogs. Additional and repeated verbal directions from suitably trained veterinary staff at the point of sale would further reinforce the impact and comprehension of such labelling.

Fig 6.

Labels using humour and dramatic emphasis to highlight the extreme risk of PSO products to cats may be utilised as an adjunct to written warnings when veterinarians dispense products containing permethrin to canine patients. These cartoons were created by the veterinarian and cartoonist Frank Gaschk (Grrinninbear Designs) and a number are available as free downloads from the resources section at www.cve.edu.au

A significant issue raised in our analysis is that there is an urgent need to quantify the incidence of poisoning and adverse reactions to drugs and food in companion animals in Australia so that regulators, manufacturers and distributors have more timely appreciation of poisonings resulting from OTC formulations, including anticoagulant rodenticides, snail bait, paracetamol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (label and offlabel use), ethylene glycol and other potential poisons. The fact that many of these products are used ‘off label‘ does not negate the value of data collection regarding intoxication. Another challenge is to work out means to monitor the response to risk-management measures — to determine how effective they have been, and to allow modifications to improve efficacy. Recent episodes of clinical intoxication with irradiated or contaminated pet food in Australia have further emphasised the need for a central reporting process.37–42

What Now?

Veterinarians can reduce the incidence of permethrin intoxication by collaborating with drug manufacturers, government authorities and distributors of PSOs. Our challenge is to assist regulators in risk communication and risk management.

As a result of this survey, the APVMA convened a meeting of all relevant stakeholders in December 2008, providing the manufacturers of PSO products and representatives of supermarket chains and pet stores with an opportunity to respond to issues associated with PSO intoxication of cats. As a result, Woolworths, the largest supermarket chain in Australia, has acted to separate dog and cat ‘spot-on’ flea products on its shelves. The aim is to reduce the possibility of consumers confusing dog and cat products. The AVA is coordinating a consumer research project to explore the most effective way to enhance the effectiveness of package warning labels and posters at point of sale, with the cost being met by PSO manufacturers. It is expected that recommendations on more effective labelling and communication of warnings will be made after analysis of data from focus groups and further marketing surveys, and that these recommendations will be adopted by the APVMA and manufacturers. The AVA has also taken a proactive role to alert practitioners and owners of the risk of toxicity to cats from permethrin-containing products by facilitating access of veterinarians to their local media, and by providing information packs to assist this through a media release. Risk mitigation activities will be monitored and it is hoped that the collaboration of the CVE, AVA, ASAVA, APVMA, manufacturers and distributors will continue, to ensure that risk management measures lead to reductions in unintended toxicity in cats.

Key Points

Permethrin is the most commonly used synthetic pyrethroid in companion animals.

The extraordinary susceptibility of cats to permethrin toxicosis is not well understood.

The present survey findings of 750 cases of feline permethrin spot-on (PSO) intoxication, with 166 deaths, over a 2-year period is likely to have underestimated the true number of cases by a substantial margin.

The survey data indicates that over-the-counter sales of simple PSO products from supermarkets, and pet and produce stores account for most cases of intoxication in cats.

The high incidence of toxicity suggests that current warnings do not spell out the potentially lethal consequences of non-compliance; and that there is insufficent warning about the risk of secondary intoxication of cats exposed to treated dogs.

It is the opinion of the authors and 90% of survey respondents that PSO products should no longer be available over the counter at non-veterinary outlets.

Ongoing collaboration between veterinary organisations and individual veterinarians and drug manufacturers, regulatory authorities and distributors is required to lead to reductions in unintended toxicity in cats.

Supplementary Data

A submission by one of the authors (SP) to the US Environmental Protection Agency Office of Pesticide Programs, detailing risk factors associated with PSO intoxication of cats, and actions to mitigate risk, is included in the online version of this article at doi:10.1016/j.jfms.2009.12.002

Acknowledgements

Richard Malik is supported by the Valentine Charlton Bequest of the Centre for Veterinary Education of The University of Sydney. At the CVE, Rhondda Hollis, Anna Jones and especially Lis Churchward were instrumental in the implementation of this survey. Anne Jackson (AVJ Editor) and Mark Lawrie (AVA President) were also very supportive of this initiative and helped distribute the survey through the ASAVA. The help and advice of John Owusu of the APVMA and Bob Rees from Bayer Australia is also gratefully appreciated. Rhian Cope proved to be an excellent sounding board for a range of toxicological issues.

References

- 1.Ray DE. Pesticides derived from plants and other organisms. In: Hayes WJ, Laws ER, eds. Handbook of pesticide toxicology, classes of pesticides. Vol 2. San Diego: Academic Press, 1991: 585–636. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bates N. Pyrethrins and pyrethroids. In: Campbell A, Chapman M, eds. Handbook of poisoning in dogs and cats. London: Blackwell Science, 2000: 42–5. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anadón A, Martínez-Larrañaga MR, Martínez MA. Use and abuse of pyrethrins and synthetic pyrethroids in veterinary medicine. Vet J 2009; 182: 7–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hansen SR. Pyrethrins and pyrethroids. In: Peterson ME, Talcott PA, eds. Small animal toxicology. 2nd edn. St Louis: Elsevier Saunders, 2006: 1002–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whittem T. Pyrethrin and pyrethroid insecticide intoxication in cats. Compend Contin Educ Pract Vet 1995; 17: 489–92. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meyer EK. Toxicosis in cats erroneously treated with 45% to 65% permethrin products. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1999; 215: 198–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Richardson JA. Permethrin spot-on toxicosis in cats. J Vet Emerg Crit Care 2000; 10: 103–6. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Volmer P. Pyrethrins and pyrethroids. In: Plumlee KH, ed. Clinical veterinary toxicology. Missouri: Mosby, 2004: 188–192. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merola V, Dunayer E. The 10 most common toxicoses in cats. Vet Med 2006; 101: 339–42. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sutton NM, Bates N, Campbell A. Clinical effects and outcome of feline permethrin spot-on poisonings reported to the Veterinary Poisons Information Service (VPIS) London. J Feline Med Surg 2007; 9: 335–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Platt SR, Olby NJ. Neurological emergencies. In: Platt SR, Olby NJ, eds. BSAVA manual of canine and feline neurology. 3rd edn. Gloucester: British Small Animal Veterinary Association, 2004: 333–35. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dymond NL, Swift IM. Permethrin toxicity in cats: A retrospective survey of 20 cases. Aust Vet J 2008; 86: 219–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Valentine WM. Pyrethrins and pyrethroid insecticides. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 1990; 20: 375–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Volmer PA, Khan SA, Knight MW, Hansen SR. Warning against use of some permethrin products in cats. J Am Vet Med Assoc 1998; 213: 800–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volmer PA, Khan SA, Knight MW, Hansen SR. Permethrin spot-on products can be toxic in cats. Vet Med 1998; 93: 1039. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Woo A, Lunn P. Permethrin toxicity in cats. Aust Vet Pract 2004; 23: 148–151. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Linnett P-J. Permethrin toxicosis in cats. Aust Vet J 2008; 86: 32–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heath TJ. Number, distribution and concentration of Australian veterinarians in 2006, compared with 1981, 1991 and 2001. Aust Vet J 2008; 86: 283–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gray A. Permethrin toxicity in cats. Vet Rec 2000; 147: 556. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martin A, Campbell A. Permethrin toxicity in cats. Vet Rec 2000; 147: 639. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gleadhill A. Permethrin toxicity in cats. Vet Rec 2004; 155: 648. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boag A. Permethrin flea treatments: Often not spot-on for felines. Vet Times 2007; 37: 10. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Plumb DC. Veterinary drug handbook. 6th edn. Ames, Iowa: Blackwell Publishing, 2008: 1009–10, 1012–13. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Curti R, Kupper J, Kupferschmidt H, Naegeli H. [A retrospective study of animal poisoning reports to the Swiss Toxicological Information Centre (1997–2006)]. Schweiz Arch Tierheilkd 2009; 151: 265–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tjalve H. Adverse reactions to veterinary medicinal products: An overview based on the Swedish experience. J Vet Pharmacol Ther 2009; 32: 41–4.19161454 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keck G. Effets indésirables des spécialités antiparasitaires externes à base de perméthrine utilisées en lQ spot-on rQ chez les carnivores domestiques. Rapport d'expertise de pharmacovigilance relatif à l'avis CNPV − 01 du 18/03/2003. ANMV, AFSSA. Fougères, Commission Nationale de Pharmacovigilance Vétérinaire, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Malik R. Permethrin intoxication. Aust Vet J 2008; 86: 373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.See AM, McGill SE, Raisis AL, Swindells KL. Toxicity in three dogs from accidental oral administration of a topical endectocide containing moxidectin and imidacloprid. Aust Vet J 2009; 87: 334–37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gorn GJ, Lavack AM, Pollack CR, Weinberg CB. An experiment in designing effective warning labels. Health Mark Q 1996; 14: 43–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Edworthy J, Hellier E, Morley N, Grey C, Aldrich K, Lee A. Linguistic and location effects in compliance with pesticide warning labels for amateur and professional users. Hum Factors 2004; 46: 11–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hancock HE, Rogers WA, Schroeder D, Fisk AD. Safety symbol comprehension: Effects of symbol type, familiarity, and age. Hum Factors 2004; 46: 183–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hancock HE, Fisk AD, Rogers WA. Comprehending product warning information: Age-related effects and the roles of memory, inferencing, and knowledge. Hum Factors 2005; 47: 219–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wolf MS, Davis TC, Shrank W, et al. To err is human: Patient misinterpretations of prescription drug label instructions. Patient Educ Couns 2007; 67: 293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Delhaye D. Effets indésirables et intoxications dus à l'utilisation de médicaments à base de perméthrine chez le chat. Etude épidémiologique. Thesis, Docteur Vétérinaire, École Nationale Vétérinaire de Lyon, Lyon, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sutton NM, Campbell A. The effect of publicity on the frequency of feline permethrin exposures reported to the Veterinary Poisons Information Service, London. Clin Toxicol 2008; 46: 385. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bessant C. How poison centres can help in animal welfare campaigns. Clin Toxicol 2008; 46: 358. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Seavers A, Baker G. Suspected new cases of acute renal failure with glucosuria-Fanconi like syndrome in dogs in NSW fed imported chicken treats from China. Control & Therapy 2008; 252: 33. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fawcett A. Cat illness, death associated with pet food. The Veterinarian December 2008; 1, 30. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fawcett A. Vets urged to report cases involving toxic treats. The Veterinarian December 2008; 6, 7. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fawcett A. Toxicity scare prompts pet food withdrawal. The Veterinarian January 2009; 1, 5. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fawcett A. Dog treat withdrawn. Veterinarian February 2009; 7. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Child G, Foster DJ, Fougere BJ, Milan JM, Rozmanec M. Ataxia and paralysis in cats in Australia associated with exposure to an imported gamma-irradiated commercial dry pet food. Aust Vet J 2009; 87: 349–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]