Abstract

This study examined the intergenerational transmission of implicit and explicit attitudes toward smoking, as well as the role of these attitudes in adolescents’ smoking initiation. There was evidence of intergenerational transmission of implicit attitudes. Mothers who had more positive implicit attitudes had children with more positive implicit attitudes. In turn, these positive implicit attitudes of adolescents predicted their smoking initiation 18-months later. Moreover, these effects were obtained above and beyond the effects of explicit attitudes. These findings provide the first evidence that the intergenerational transmission of implicit cognition may play a role in the intergenerational transmission of an addictive behavior.

Keywords: intergeneration transmission, implicit attitudes, explicit attitudes, smoking

The attitude construct has long been considered to be central in social psychology theory and research (Allport, 1954). The major reason for this importance is that attitudes reflect evaluative associations to objects and people and are generally useful in predicting approach-avoidance behaviors toward those objects and people. Despite some earlier questions about the ability of attitudes to predict behavior (Wicker, 1969), once certain conceptual and measurement issues were taken into account, attitudes have, in fact, proven to be useful predictors of behavior (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977; Fazio & Zanna, 1981; Kraus, 1995).

However, attitude measures have not been equally accurate or useful in predicting all types of behaviors. With regard to paper and pencil explicit measures of attitudes, these measures often fail to predict certain behaviors because of concerns with norms and social desirability, which influence self-reports (Crosby, Bromley, & Saxe, 1984; Crowne & Marlowe, 1960; Nosek, 2005). For this reason, in recent years, implicit measures of attitudes have been developed that are not as susceptible to social desirability concerns. These measures reflect more automatic evaluative associations that are not under conscious control and thus do not show distortions in a socially desirable direction. Thus, for example, far more racial or gender prejudice is revealed on implicit measures than on explicit measures (Dovidio et al., 1997; Greenwald & Banaji, 1995). For such controversial issues, these implicit measures have successfully predicted behavior better than have paper and pencil measures (Ashburn-Nardo, Knowles, & Monteith, 2003; Dovidio, Kawakami, & Gaertner, 2002; Fazio, Jackson, Dunton, & Williams, 1995; Fazio & Olson, 2003; Perdue & Gurtman, 1990; Towles-Schwen & Fazio, 2003, 2006).

For attitude objects or issues that are non-controversial and that do not involve issues of social desirability, explicit measures and implicit measures tend to correlate. However, for more socially controversial issues, these measures often diverge (Greenwald, Poehlman, Uhlmann, & Banaji, in press; Hofmann et al., 2005; Nosek, 2005). In addition to attitudinal measures of stereotyping and prejudice, this has also been true for measures of attitudes toward other counter-normative behaviors such as substance use. For example, Stacy (1997) found that implicit (but not explicit) measures of expectancies about marijuana predicted college students’ later marijuana use. However, Stacy did not find a discrepancy between implicit and explicit measures in predicting alcohol use, a far less stigmatized behavior and one that is less susceptible to concerns about social desirability. More recently, research by O’Connor, Fite, Nowlin, and Colder (2007) suggested that implicit cognitions serve as precursors to early stages of substance use. In addition, Thush and Wiers (2007) reported that implicit alcohol-related cognitions were important in predicting alcohol use and binge drinking.

Consistent with this work in other areas of substance use, research on cigarette smoking also finds a divergence between implicit and explicit measures. Swanson, Rudman, and Greenwald (2001; see also De Houwers, Custers, & De Clercq, 2006) reported a large discrepancy between the implicit and explicit attitudes of smokers, whereas vegetarians (a non-controversial and socially acceptable behavior) showed no such discrepancy between their implicit and explicit attitudes toward meat or vegetables. Sherman et al. (2003) also reported inconsistencies between the implicit and explicit attitudes of smokers toward smoking, especially when they had recently smoked.

With regard to the antecedents of smoking behavior, researchers have suggested that implicit attitudes, the automatic affective responses to smoking, play a very important role in the initiation and maintenance of smoking. Positive implicit attitudes toward smoking might make smoking initiation more likely and might render as unsuccessful consciously controlled attempts to quit smoking. In support of the idea that implicit attitudes are important for smoking behaviors, Waters et al. (2007) reported that implicit attitudes toward smoking are strongly associated with smoking motivation, craving, and dependence. Using a different assessment of implicit attitudes, Payne, McClernon, and Dobbins (2007) found that smokers who reported the strongest withdrawal symptoms and those who were most motivated to smoke showed the most positive implicit attitudinal responses toward smoking-related stimuli. If smoking cues take on automatic positive reward value for some smokers, this can help explain the maintenance of smoking as a habitual behavior. Mogg et al. (2003) demonstrated that the automatic attentional responses of smokers to smoking cues were related to craving and to the motivational valence of smoking stimuli. Similar findings about the important role of implicit attitudes for substance use have been reported for alcohol and drug use (O’Connor et al., 2007; Stacy, 1997; Stacy, Ames, Sussman, & Dent, 1996; Thush & Wiers, 2007). Importantly, these studies of alcohol and marijuana use have demonstrated the utility of implicit attitudes in predicting substance use behavior for adolescents.

Intergenerational Transmission of Attitudes

Given the historical utility of both implicit and explicit attitudes in predicting behavior, it is important to understand the origins and development of these attitudes. Currently, little is known about the early developmental origins of implicit attitudes. Recently, Rudman, Phelan, and Heppen (2007) reported that smokers’ implicit attitudes toward smoking were uniquely predicted by early smoking experience, whereas their explicit attitudes toward smoking were predicted by recent smoking experiences.

Although it is overly simplistic to think that attitudes have only one source, an obvious important influence on attitude development for adolescents is the attitudes of their parents. Thus, there has been a good deal of research demonstrating the relations between parental attitudes and those of their children. These studies have generally found a strong relation between attitudes of parents and children. For example, O’Bryan, Fishbein, and Ritchey (2004) found that parents’ explicit prejudices and stereotypes were reflected in their adolescent children’s explicit prejudices, although mothers and fathers differentially influenced different domains of prejudice. Similarity between parents and their children have also been reported for aspects of self-concept, religious values, attitudes toward eating, and political orientation (Baker, Whisman, & Brownell, 2000; Pinquart & Silbereisen, 2004; Zentner & Renaud, 2007).

The mechanisms that underlie intergenerational transmission of attitudes can be quite varied. Social psychological processes such as social learning, modeling, conformity, etc. clearly play a role. In addition, attitude similarity across generations is very much related to liking and attachment (see Grusec, Goodnow, & Kuczynski, 2000 for a discussion of these mechanisms). Beyond these social environmental mechanisms, other researchers have demonstrated that attitudes have a heritable component. Genetic contributions have been reported for broad social attitudes such as altruism and aggression (Rushton et al., 1986), for job satisfaction (Arvey, Bouchard, Segal, & Abraham, 1989), for religious attitudes (Waller et al., 1990), for political attitudes (Martin et al., 1986), and, more relevant to the present paper, for attitudes toward alcohol (Perry, 1973). In a comprehensive study of attitudes, Tesser (1993) supported the idea that a wide range of attitudes have a heritable component. Based on implicit as well as explicit measures, he also reported that heritable attitudes were held especially strongly, were associated with fast response times, were very consequential in attraction, and were extremely difficult to change.

More recently, Olson, Vernon, Harris, and Jang (2001) examined the genetic basis of attitudes in a study of twins. Although nonshared environmental experiences accounted for most of the variance in attitudes, most of the attitude factors showed significant heritability. This was true for a wide variety of attitudes including reading preferences, immigration policies, and roller-coasters. Olson et al. (2001) suggested that mediators such as personality traits, physical features, and academic achievement were heritable and might account for the heritable components of attitudes. Thus, genetic factors might lead to different experiences, which then lead to different attitudes. In a study of adopted and nonadopted participants, Abrahamson, Baker, and Caspi (2002) reported a significant genetic component for political conservatism. Importantly for our purposes, their participants included young adolescents and their parents.

Although both social environmental and genetically influenced mechanisms are involved in the intergenerational transmission of attitudes, to our knowledge, research on intergenerational transmission of attitudes, with one exception, has been limited to attitudes based on explicit measures. Sinclair, Dunn, and Lowery (2005) measured parents’ explicit racial attitudes as well as their adolescents’ explicit and implicit racial attitudes. They found that both the explicit and implicit racial attitudes of the children were predicted from the explicit attitudes of their parents, although this effect was much stronger for children who were highly identified with their parents. However, because parents’ implicit attitudes were not measured, this study did not directly assess the intergenerational transmission of implicit attitudes. Thus, nothing is known about the extent to which attitudes, as measured implicitly, are intergenerationally transmitted. Such knowledge would be especially important for issues where explicit measures are suspect based on social desirability concerns. In this paper, we focus on one such issue, attitudes toward cigarette smoking.

What should we expect to observe about the intergenerational transmission of implicit and explicit attitudes toward smoking? On the one hand, parental explicit attitudes toward smoking will be readily observable by children, and thus perhaps such attitudes will show high intergenerational transmission. On the other hand, adolescence is a period of rebelliousness and independence-seeking and, in areas of problem behaviors, adolescents may adopt explicit attitudes toward smoking in opposition to those of their parents. Implicit attitudes, because they are not as readily observable, may show less intergenerational transmission than do explicit measure of attitudes. However, implicit attitudes are often communicated with or without awareness and in subtle ways (Dovidio et al., 1997; Fazio & Olson, 2003; Olson & Fazio, 1999). Thus, adolescents may be influenced by their parents’ implicit attitudes toward smoking without adopting the kinds of rebellious reactions that require conscious control. If so, then implicit attitudes will show substantial intergenerational transmission.

Of course, the transmission of smoking attitudes from parents to children is important only to the extent that these attitudes impact the children’s behavior. The current study examines the implications of the intergenerational transmission of smoking attitudes for prospectively predicting smoking onset among initial adolescent nonsmokers 18 months later. We model two correlated processes—the intergenerational transmission of attitudes toward smoking and the intergenerational transmission of smoking. Within this model, we test whether adolescents’ smoking onset is related to their own implicit and explicit attitudes as well as the implicit and explicit smoking attitudes of their parents. In addition, we examine the effects of parents’ attitudes and parents’ smoking both as direct influences on adolescent smoking onset and as mediated through the adolescents’ own smoking attitudes. We examine these processes separately for fathers and mothers as they influence their sons and daughters. We accomplished these goals using a web-based multi-generational study of cigarette smoking in which the attitudes of parents and their adolescent children toward smoking were assessed with both explicit measures and implicit measures. We also measured parents’ current smoking behavior as well as their adolescents’ smoking behavior. Although previous research has demonstrated that explicit and implicit attitudes predict adult smoking as well as adolescent substance use (O’Connor et al., 2007; Stacy & Wiers, in press; Thush & Wiers, 2007; Wiers, Gunning, & Sergeant, 1998; Wiers et al., 2006b), these studies have not examined intergenerational transmission of attitudes. Using cross-sectional data in a laboratory study, we found that mothers’ (but not adolescents’) implicit attitudes were correlated with adolescents’ lifetime smoking (Chassin et al., 2002). Thus, to our knowledge, this is the first study to empirically examine the intergenerational transmission of implicit attitudes toward smoking and its implications for the prospective prediction of adolescent smoking initiation.

Method

Participants

Participants were adolescents (10–18) and their parents who were participants in an 18 month longitudinal web-based study of families and smoking socialization. Families were recruited through adult participants in the Indiana University (IU) Smoking Survey, an ongoing cohort-sequential study of the natural history of cigarette smoking (see e.g., Chassin et al., 2000). The larger study has been ongoing since 1980, with yearly in school assessments in 1980–1983 of all consenting 6th – 12th graders in a Midwestern county school system (total N assessed at least once = 8,487), and with mail follow-ups in 1987, 1993, 1999, and 2005. In each case, 70% or more of the original sample were successfully retained. The sample is representative of its community, one that is predominantly white (96% non-Hispanic Caucasian) and well-educated (see, e.g., Chassin et al., 2000). For each follow-up, although biases have been small in magnitude(e.g., Rose et al., 1996), dropouts were more likely to be smokers and to have more positive attitudes and beliefs about smoking, as well as to have parents and friends who were more likely to smoke.

In 2005, IU Smoking Survey participants (ages 32–42) who had adolescent children (between ages 10–18) were recruited, with their children and their spouses/partners into an 18 month longitudinal web-based study and paid $25 for participation. For the current analyses, we selected all nonsmoking (at first measurement) adolescent children and their parents who had participated in the web-based multigenerational study, including the completion of an implicit measure of attitudes toward cigarette smoking (N=709). 83.8% of those adolescents were successfully retained at 18-month follow-up, when their smoking status was re-assessed. The mean age of these children was 13.4 and 50.7% were male. In the final models, there were 513 child-mother pairs and 427 child-father pairs.

Procedures

Data on parent smoking, adolescent smoking, and parent and adolescent explicit and implicit attitudes toward smoking were obtained from a web-based multigenerational study.

Measures

Parents’ and Adolescents’ Smoking

Parents and adolescents’ self-reported their smoking status as “Never smoked, not even a single puff,” “Smoked once or twice ‘just to try’ but not in the last month,” “Do not smoke, but in the past I was a regular smoker,” “Smoke regularly, but not more than once a month,” “Smoke regularly, but not more than once a week,” “Smoke regularly, but not more than once a day,” and “Smoke more than once a day.” Adolescents were selected to be initial never smokers, and their smoking status at 18-month follow-up was dichotomized as continued never smoking versus any increase in smoking (15% initiated some smoking by follow-up). Parental smoking was dichotomized as current smoking or not, based on their smoking in the past month (within the subsample of initial nonsmoking adolescents 12.7% of mothers and 14.3% of fathers were current smokers, and most of them smoked daily).1

Explicit Attitudes Toward Smoking

Parents and adolescents reported their global attitudes toward smoking using a semantic differential measure of smoking as “nice,” “pleasant,” and “fun” (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1970). A global explicit attitude score was computed by taking the mean of the three items. This measure has been used at each wave of the IU smoking survey and has successfully prospectively predicted smoking transitions (Chassin et al., 1984). Due to severe positive skewness, explicit attitude scores were log transformed for analysis. Higher values indicate more positive explicit attitudes.2

Implicit Attitudes Toward Smoking

Parents and adolescents completed an implicit measure of smoking attitudes using a version of the IAT (Implicit Association Test; Nosek, Greenwald, & Banaji, 2005, 2006). The specific implementation of the IAT was web-based, using Java applets administered within Project Implicit’s Virtual Laboratory software (see Nosek et al., 2005).

Stimuli and Materials

There were eight pictures that showed a scene related to smoking (three pictures of someone holding a burning cigarette, two pictures of a burning cigarette in an ashtray, one picture of someone lighting a cigarette, one picture of cigarettes on a table, and one picture of cigarettes and a lighter on a table) and eight pictures of geometric shapes (rectangle, parallelogram, triangle, pentagon, trapezoid, square, oval, and octagon). As positive and negative stimuli, we used eight adjectives with a positive meaning (wonderful, nice, friendly, pleasant, great, excellent, terrific, and fabulous) and eight adjectives with a negative meaning (stupid, rotten, awful, dreadful, ugly, disgusting, nasty, and horrible). All stimuli were presented in the center of a black screen. Words were presented in green letters. The words smoking, shape, good, and bad were used for labels. The smoking and shape labels were presented in white letters and the good and bad labels in green letters. Participants responded by pressing the letter e (left) or the letter i (right) on the keyboard.

Procedure

The IAT is a dual categorization task. In our procedure, participants saw the four types of stimuli described above: pictures related to smoking, pictures of shapes, positive words, and negative words. There were five phases to each IAT during which the labels of the stimuli assigned to the left and right keys were continuously shown on the screen. The first phase was a practice phase consisting of 20 trials. During this phase, good and bad words were presented in random order. Participants were asked to match the words to the good or bad label by pressing the appropriate key (i.e., the letter i or e, counterbalanced). In the second phase, also consisting of 20 trials, the pictures of smoking scenes and shapes were presented in random order, and participants were asked to match the pictures to the smoking or shape label by pressing the appropriate key (i.e., the letter i or e, counterbalanced). The third phase consisted of two blocks, one of 20 trials and one of 40 trials, during which pictures and words were presented in random order, and participants pressed the appropriate key. The fourth and fifth phases were identical to the second and third, except that the response assignment for the smoking and shape pictures was reversed (e.g., the letter i instead of e), and there were 40 trials in the fourth phase as opposed to 20 in the second phase. As a result, for half of the participants, the third phase contained the SMOKING+GOOD task and the fifth phase contained the SMOKING+BAD task, whereas the reverse was true for the other half of the participants. On each trial, the stimulus was presented until the participant pressed the left or right key. If the response was correct, the next stimulus appeared. If the response was incorrect, a red X was presented on the screen until the participant corrected the response. The key phases for assessing implicit attitudes toward smoking were phases three and five. To the extent that latencies of response are faster during the phase when smoking-related pictures are paired with positive words than the phase when smoking-related pictures are paired with negative words, participants have positive attitudes toward smoking.

To create indicators for a latent variable representing implicit attitudes, we calculated four IAT D scores for each participant using the scoring algorithm proposed by Greenwald, Nosek, and Banaji (2003). The four IAT indicators were based on the difference between the means of each half of the trials from the two blocks that comprised the third and fifth phases. That is, the mean latency for trials 1–10 of phase 3 was compared with that of trials 1–10 of phase 5, and so on for sets of trials 11–20, 21–40, and 41–60. Because of the counterbalancing described above in which half of participants received the SMOKING+GOOD task first, and the other half received the SMOKING+BAD task first, we standardized the four IAT D scores within each condition

Analyses

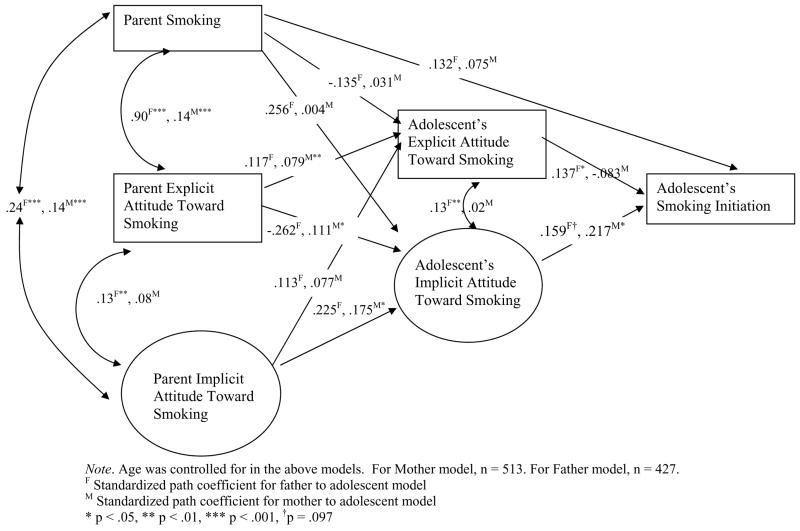

To examine the intergenerational transmission of implicit and explicit attitudes and the implications for adolescent smoking initiation, we modeled the parent’s implicit attitude, explicit attitude, and smoking behavior as correlated exogenous variables, with each predicting the adolescent’s implicit and explicit attitudes (modeled as correlated mediators) that, in turn, were tested as predictors of child smoking initiation as the dichotomous outcome variable (see Figure 1). Structural Equation Models were tested with Mplus 5 and were tested separately for mothers and fathers to allow for single parent families. Structural path invariance tests as well as measurement invariance tests for IAT scores were conducted across boys and girls using weighted least squares (WLS) parameter estimates with conventional standard errors and chi-square test statistics that use a full weight matrix. Final models were estimated by weighted least squares using a diagonal weight matrix with standard errors and mean- and variance-adjusted chi-square test statistics (WLSMV), which produce less biased results for categorical outcomes than full WLS (Flora & Curran, 2004; Muthen & Muthen, 2006). Despite the strength of WLSMV estimation in categorical outcome variable models, chi-square values in WLSMV estimation cannot be used to compare nested models (Muthen & Muthen, 2006). Thus, WLS was used in invariance tests. Missing data on endogenous variables were handled with full information maximum likelihood estimation (Graham et al., 1997), and missing data on exogenous variables were not included in analyses. Mediated effects were tested by computing 95% asymmetric confidence limits for indirect effects using PRODCLIN program (MacKinnon, Lockwood, & Williams, 2004). The adolescent’s age was treated as a covariate in all models. Modification indices indicated that child’s age was related to the smoking outcome (such that there was greater smoking onset for older children) and to explicit attitudes (such that older children held less negative explicit attitudes toward smoking), but that age was not related to implicit attitudes. Thus, we included age as an exogenous variable linked to both children’s explicit attitudes and smoking.

Figure 1.

Path model for adolescents’ smoking initiation as a function of parents’ attitudes and smoking

Results

Measurement invariance test

For both fathers’ and mothers’ models, measurement invariance (i.e., invariance of factor loadings and intercepts) in IAT scores was supported across boys and girls (model chi-square difference: 12.01 for the fathers’ model and 11.17 for the mothers’ model at df = 8) except the intercept of one of the four child IAT measures. In the structural path invariance tests, this intercept was allowed to vary across boys and girls.

Structural path invariance test

As shown in Table 1, structural path invariance was supported across boys and girls for both the fathers’ and mothers’ models. Parent’s influence on child’s attitudes and smoking initiation was not different between boys and girls (chi-square difference: 11.4 for the fathers’ model and 6.26 for the mothers’ model at df = 7). Also, the influence of child’s explicit and implicit attitudes on smoking initiation was not different between boys and girls (chi-square difference: 1.03 for the fathers’ model and 1.61 for the mothers’ model at df = 2). All the nested models produced acceptable model fit indices with p > .05 for model chi-square values, comparative fit indices ranging from .93 to .95, and root mean square error of approximation ranging from .028 to .031.

Table 1.

Structural path invariance tests across boys and girls

| Model | χ2 | df | p | CFI | RMSEA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fathers model | |||||

| All the paths were freely estimated | 135.97 | 115 | 0.0885 | 0.94 | 0.029 |

| Paths from child attitudes to the outcome variable were constrained to be equal | 137.00 | 117 | 0.0998 | 0.94 | 0.028 |

| Paths from a father to a child were constrained to be equal | 147.37 | 122 | 0.0588 | 0.93 | 0.031 |

| All the paths were constrained to be equal | 150.12 | 126 | 0.0703 | 0.93 | 0.030 |

| Mothers model | |||||

| All the paths were freely estimated | 140.98 | 115 | 0.0503 | 0.95 | 0.030 |

| Paths from child attitudes to the outcome variable were constrained to be equal | 142.59 | 117 | 0.0540 | 0.95 | 0.029 |

| Paths from a mother to a child were constrained to be equal | 147.24 | 122 | 0.0596 | 0.95 | 0.028 |

| All the paths were constrained to be equal | 151.43 | 126 | 0.0610 | 0.95 | 0.028 |

Note. CFI = Comparative Fit Index, RMSEA = Root Mean Square Error of Approximation.

Path coefficients in the final model

Standardized path coefficients for the final fathers’ and mothers’ models are shown in Figure 1 (and unstandardized coefficients, with 95% confidence intervals are presented in Table 2). The mothers’ model showed significant intergenerational transmission of implicit and explicit attitudes. Mothers with more positive implicit attitudes had adolescents with more positive implicit attitudes, and mothers with more positive explicit attitudes had adolescents with more positive explicit attitudes. In addition, mothers’ explicit attitudes significantly influenced adolescents’ implicit attitudes, such that mothers with more positive explicit attitudes toward smoking had adolescents with more positive implicit attitudes. Moreover, adolescents’ implicit (but not explicit) attitudes prospectively predicted smoking initiation such that adolescents with more positive implicit attitudes were significantly more likely to initiate smoking 18-months later. There were significant indirect effects of mothers’ implicit attitudes on the adolescents’ smoking initiation through the adolescents’ implicit attitudes (95% asymmetric confidence interval: 0.006 to 0.177). Mothers with more positive implicit attitudes had children with more positive implicit attitudes and those children with more positive implicit attitudes were more likely to initiate smoking. The indirect effects of mothers’ explicit attitudes on adolescent smoking initiation through adolescents’ implicit attitudes was also significant. Specifically, the 95% asymmetric confidence interval was from 0.001 to 0.068. Mothers with more positive explicit attitudes had children with more positive implicit attitudes, and those children with more positive implicit attitudes were more likely to initiate smoking.

Table 2.

Non-Standardized coefficient estimates with confidence intervals

| Path | Mothers model | Fathers model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| From: | To: | Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval | Estimate | 95% Confidence Interval |

| Parent Implicit Attitude | Child Implicit Attitude | .126 | .015, .236 | .230 | −.172, .632 |

| Parent Explicit Attitude | .047 | .002, .092 | −.455 | −6.819, 5.909 | |

| Parent Smoking | .004 | −.140, .149 | .614 | −7.560, 8.787 | |

| Parent Implicit Attitude | Child Explicit Attitude | .134 | −.055, .323 | .033 | −.026, .093 |

| Parent Explicit Attitude | .081 | .029, .134 | .059 | −.818, .936 | |

| Parent Smoking | .093 | −.116, .302 | −.093 | −1.210, 1.023 | |

| Child Implicit Attitude | Child Smoking Initiation | .594 | .135, 1.053 | .346 | −.063, .755 |

| Child Explicit Attitude | −.093 | −.464, .278 | 1.034 | .216, 1.851 | |

| Parent Smoking | .252 | −.166, .670 | .690 | −2.454, 3.834 | |

For the fathers’ model, there was no significant intergenerational transmission of attitudes (either implicit or explicit) and no significant indirect effects.

Discussion

The goal of this study was to examine the intergenerational transmission of both explicit and implicit attitudes toward cigarette smoking and the role of these attitudes in adolescents’ smoking initiation (and the intergenerational transmission of smoking). To our knowledge, this is the first study to directly test the intergenerational transmission of implicit attitudes.

Perhaps not surprisingly, the correlation between implicit and explicit attitudes, although significant for fathers’ models, was modest (standardized path coefficients from .02 to .13, see Figure 1). Past research has shown that implicit and explicit attitudes are unlikely to be correlated for attitude issues and objects that are socially controversial like cigarette smoking where explicit attitudes are likely to be distorted by social desirability concerns (Greenwald et al., in press; Nosek, 2005). In addition, for such issues it is typically implicit measures that more successfully predict relevant behaviors (Dovidio et al., 1997; Fazio et al., 1995; Perdue & Gurtman, 1990).

Even though the implicit and explicit attitudes of our participants were relatively uncorrelated, both kinds of attitudes played a role in the prediction of the smoking attitudes of our adolescent participants. Most importantly, for mothers, their implicit attitudes predicted the implicit attitudes of their nonsmoking children, and these implicit attitudes of the children predicted their smoking initiation at an18 month follow-up. The paths from fathers’ implicit attitudes through the implicit attitudes of their children and on to the smoking initiation of their children showed the same pattern, but the results did not reach statistical significance. This is likely due to having fewer fathers in our sample and thus less statistical power, but we cannot definitively conclude that there is something different about the paths from fathers versus mothers to their children regarding smoking behavior.

Regarding the first pathway from mothers’ implicit attitudes to the implicit attitudes of their children, to our knowledge this is the first clear finding of intergenerational transmission of implicit attitudes. Although the transmission of explicit attitudes from parents to children has been well-documented (O’Bryan et al., 2004; Pinquart & Silbereisen, 2004), similar transmission of implicit attitudes has not previously been demonstrated. Sinclair et al. (2004) reported that parental explicit racial attitudes predicted both the implicit and explicit attitudes of their adolescent children, but they did not measure the implicit attitudes of the parents. As Olson and Fazio (1999; see also Dovidio et al. 1997; Towles-Schwen & Fazio, 2006) have suggested, implicit attitudes may be communicated by people in very subtle ways, and this sending and receiving of implicit attitudes may affect behavior in important ways. For example, Towles-Schwen and Fazio (2006) reported that the implicit attitudes of White college freshmen who were randomly paired with a Black roommate predicted the longevity of the roommate relationship. Towles-Schwen and Fazio suggest that the implicit attitudes of the White roommates were “leaked” to the Black roommate by means of nonverbal behaviors such as eye movement and body posture, and these attitudes determined the success or failure of the roommate match.

The second pathway, from the adolescents’ implicit attitudes toward smoking stimuli to their subsequent smoking initiation, is equally important. Previous research has reported that implicit attitudes toward smoking stimuli are associated with smoking motivation, craving, and dependence (Waters et al., 2007; Payne et al., 2007). The relation between implicit attitudes and other substance use has also been documented (O’Connor et al., 2007; Stacy, 1997; Stacy et al., 1996; Thush & Wiers, 2007). These studies did not employ the IAT as an implicit measure of attitudes. More importantly, the current study is the first to report a prospective link between implicit attitudes and smoking initiation at a later time. Also importantly, the links between mother’s and child’s IAT scores and between child’s IAT scores and subsequent smoking initiation was significant above and beyond the explicit attitudes and the smoking behavior of the parents.

There are other pathways in the model that also deserve comment. Mothers who had more positive explicit attitudes toward smoking had adolescents with both more positive explicit attitudes and more positive implicit attitudes toward smoking, but the explicit attitudes of the adolescents did not prospectively predict their smoking initiation. However, the indirect effect of mother’s explicit attitudes on adolescent’s smoking initiation through adolescent’s implicit attitudes was also significant. Thus, again it is the nonsmoking adolescents’ implicit attitudes toward smoking that best predicts whether or not they will become smokers. Despite the fact that parent smoking is generally a strong predictor of smoking by their adolescent children, within the current models, parent smoking did not have a direct effect on the smoking initiation of their children controlling for children’s attitudes.

Although the current study makes an important contribution by being the first to demonstrate the intergenerational transmission of implicit attitudes and their implications for smoking behavior, there are also limitations that must be acknowledged. First, the sample was largely non-Hispanic Caucasian, and different findings might be produced in more ethnically and racially diverse populations. Second, the adolescents were young and just beginning smoking initiation. Different findings might be produced at different ages and stages of smoking.

In sum, the current study is the first to demonstrate the intergenerational transmission of implicit attitudes and its implications for smoking onset and the intergenerational transmission of smoking. These findings suggest that family-based programs designed to prevent smoking initiation in children might do well to focus on changing parents’ and adolescents’ implicit attitudes. Methods for changing implicit attitudes have been proposed and tested and proven to be somewhat successful (Kawakami, Phills, Steele, & Dovidio, 2007; Monteith, Ashburn-Nardo, Voils, & Czopp, 2002; Wiers et al., 2006a; Wiers, De Jong, Havermans, & Jelicic, 2004). These methods involve establishing cues for the control of unwanted behavior, classical conditioning, evaluative conditioning, and practicing approach-avoidance behaviors that involve cognitive embodiment. Although some of these methods are difficult to implement, and it is not clear whether they have long-lasting effects, attitude change for implicit measures is clearly an important area for further study.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant DA13555 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

We also examined parental smoking as a trichotomous variable, separating ex-smokers from nonsmokers. However, ex-smokers and non-smokers did not significantly differ in their attitudes, whereas ex-smokers did significantly differ from current smokers. Accordingly, to simplify a complex model that had relatively small sample size, we treated parent smoking as a dichotomous variable.

Explicit attitudes could not be modeled as a latent variable without worsening model fit and causing model convergence problems because there were so few 5-point indicators (3 items) and these were highly positively skewed.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Abrahamson AC, Baker LA, Caspi A. Rebellious teens? Genetic and environmental influences on the social attitudes of adolescents. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:1392–1408. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.6.1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. The predictions of behavior from attitudinal and normative variables. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1970;6:466–487. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen I, Fishbein M. Attitude-behavior relations: A theoretical analysis and review of empirical research. Psychological Bulletin. 1977;84:888–918. [Google Scholar]

- Allport GW. The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley; 1954. [Google Scholar]

- Arvey RD, Bouchard TJ, Segal NL, Abraham LM. Job satisfaction: Environmental and genetic components. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1989;74:187–192. [Google Scholar]

- Ashburn-Nardo L, Knowles ML, Monteith MJ. Black Americans’ implicit racial associations and their implications for intergroup judgments. Social Cognition. 2003;21:61–87. [Google Scholar]

- Baker C, Whisman M, Brownell K. Studying intergenerational transmission of eating attitudes and behaviors: Methodological and conceptual questions. Health Psychology. 2000;19:376–381. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.19.4.376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, Corty E, Olshavsky R. Predicting the onset of cigarette smoking in adolescents: A longitudinal study. Journal of Applied Social Psychology. 1984;14:224–243. [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, Pitts S. The natural history of cigarette smoking from adolescence to adulthood in a midwestern community sample: Multiple trajectories and their psychosocial correlates. Health Psychology. 2000;19:223–231. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ, Rose J, Prost J. Parental smoking cessation and adolescent smoking. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2002;27:485–496. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/27.6.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby F, Bromley S, Saxe L. Recent unobtrusive studies of Black and White discrimination and prejudice: A literature review. Psychological Bulletin. 1980;87:546–563. [Google Scholar]

- Crowne DP, Marlowe D. A new scale of social desirability independent of psychopathology. Journal of Consulting Psychology. 1960;24:349–354. doi: 10.1037/h0047358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Houwer J, Custers R, DeClercq A. Do smokers have a negative implicit attitude toward smoking? Cognition and Emotion. 2006;20:1274–1284. [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Kawakami K, Gaertner SL. Implicit and explicit prejudice and interracial interactions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;82:62–68. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovidio JF, Kawakami K, Johnson C, Johnson B, Howard A. On the nature of prejudice: Automatic and controlled processes. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1997;33:510–540. [Google Scholar]

- Fazio R, Jackson J, Dunton B, Williams C. Variability in automatic activation as an unobtrusive measure of racial attitudes: A bona fide pipeline? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:1013–1027. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.6.1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio RH, Olson MA. Implicit measures in social cognition research: Their meaning and use. Annual Review of Psychology. 2003;54:297–327. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazio RH, Zanna MP. Direct experience and attitude-behavior consistency. In: Berkowitz L, editor. Advances in experimental social psychology. Vol. 14. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1981. pp. 161–202. [Google Scholar]

- Flora DB, Curran PJ. An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychological Methods. 2004;9:466–491. doi: 10.1037/1082-989X.9.4.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham JW, Hofer SM, Donaldson SW, MacKinnon DP, Schafer JL. Analysis with missing data in prevention research. In: Bryant KJ, Windle M, West SG, editors. The science of prevention: Methodological advances from alcohol and substance use research. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 1997. pp. 325–366. [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Banaji MR. Implicit social cognition: Attitudes, self-esteem, and stereotypes. Psychological Review. 1995;102:4–27. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.102.1.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JLK. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: The implicit association test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1464–1480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.6.1464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Nosek BA, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: An improved scoring algorithm. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2003;85:197–216. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.85.2.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenwald AG, Poehlman TA, Uhlmann EL, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: III. Meta-analysis of predictive validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0015575. (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grusec JE, Goodnow JJ, Kuczynski L. New directions in analyses of parenting contributions to children’s acquisition of values. Child Development. 2000;71:205–211. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann W, Gawronski B, Gschwendner T, Le H, Schmitt M. A meta-analysis on the correlation between the Implicit Association Test and explicit self-report measures. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:1369–1385. doi: 10.1177/0146167205275613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawakami K, Phills CE, Steele JR, Dovidio JF. (Close) distance makes the heart grow fonder: Improving implicit racial attitudes and interracial interactions through approach behaviors. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:957–971. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraus SJ. Attitudes and the prediction of behavior: A meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 1995;21:58–75. [Google Scholar]

- MacKinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J. Confidence limits for the indirect effect: Distribution of the product resampling methods. Multivariate Behavioral Research. 2004;39:99–128. doi: 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin NG, Eaves LJ, Heath AR, Jardine R, Feingold LM, Eysenck HJ. Transmission of social attitudes. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science. 1986;83:4364–4368. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.12.4364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogg K, Bradley B, Field M, De Houwer J. Eye movements to smoking-related pictures in smokers: Relationship between attentional biases and explicit and explicit measures of stimulus valence. Addiction. 2003;98:825–836. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00392.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monteith MJ, Ashburn-Nardo L, Voils CI, Czopp AM. Putting the brakes on prejudice: On the development and operation of cues for control. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83:1029–1050. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.5.1029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthen LK, Muthen BO. Mplus user’s guide. Los Angeles: Author; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Nosek BA. Moderators of the relationship between implicit and explicit evaluation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 2005;134:565–584. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.134.4.565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nosek BA, Greenwald AG, Banaji MR. The Implicit Association Test at age 7: A methodological and conceptual review. In: Bargh JA, editor. Social Psychology and the Unconscious: The Automaticity of Higher Mental Processes. New York: Psychology Press; 2006. pp. 265–292. [Google Scholar]

- Nosek BA, Greenwald AG, Banaji MR. Understanding and using the Implicit Association Test: II. Method variables and construct validity. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:166–180. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Bryan M, Fishbein H, Ritchey P. Intergenerational transmission of prejudice, sex-role stereotyping, and intolerance. Adolescence. 2004;39:407–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor RM, Fite PJ, Nowlin PR, Colder CR. Children’s beliefs about substance use: An examination of age differences in implicit and explicit cognitive precursors of substance use initiation. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2007;21:525–533. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.21.4.525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson JM, Vernon P, Harris J, Jang K. The heritability of attitudes: A study of twins. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;80:845–860. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson MA, Fazio RH. Nonverbal leakage of automatically activated racial attitudes. Paper presented at the meeting of the Midwestern Psychological Association; Chicago, Illinois. 1999. May, [Google Scholar]

- Payne BK, McClernan FJ, Dobbins I. Automatic affective responses to smoking cues. Experimental and Clinical Psychopharmacology. 2007;15:400–409. doi: 10.1037/1064-1297.15.4.400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdue C, Gurtman M. Evidence for the automaticity of ageism. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 1990;28:199–216. [Google Scholar]

- Perry A. The effect of heredity on attitudes toward alcohol, cigarettes, and coffee. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1973;58:275–277. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Silbereisen R. Transmission of values from adolescents to their parents: The role of value content and authoritative parenting. Adolescence. 2004;39:83–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose JS, Chassin L, Presson CC, Sherman SJ. Demographic factors in adult smoking status: Mediating and moderating influences. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10:28–37. [Google Scholar]

- Rudman LA, Phelan JE, Heppen JB. Developmental sources of implicit attitudes. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2007;33:1700–1713. doi: 10.1177/0146167207307487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rushton JP, Fulker DW, Neale MC, Nias DKB, Eysenck JJ. Altruism and aggression: The heritability of individual differences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1986;50:1192–1198. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.50.6.1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman SJ, Rose JS, Koch K, Presson CC, Chassin L. Implicit and explicit attitudes toward cigarette smoking: The effects of context and motivation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2003;22:13–39. [Google Scholar]

- Sinclair S, Dunn E, Lowery B. The relationship between parental racial attitudes and children’s implicit prejudice. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2004;41:283–289. [Google Scholar]

- Stacy AW. Memory activation and expectancy as prospective predictors of alcohol and marijuana use. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1997;106:61–73. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.106.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stacy AW, Ames SL, Sussman S, Dent CW. Implicit cognition in adolescent drug use. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 1996;10:190–203. [Google Scholar]

- Stacy AW, Wiers RW. An implicit cognition, associative memory framework for addiction. In: Munafo MR, Albero IP, editors. Cognition and addiction. NY: Oxford University Press; in press. [Google Scholar]

- Swanson LE, Rudman LA, Greenwald AG. Using the Implicit Association Test to investigate attitude-behaviour consistency for stigmatised behaviour. Cognition & Emotion. 2001;15:207–230. [Google Scholar]

- Tesser A. The importance of heritability in psychological research: The case of attitudes. Psychological Review. 1993;100:129–142. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.100.1.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thush C, Wiers RW. Explicit and implicit alcohol-related cognitions and the prediction of future drinking in adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2007;32:1367–1383. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towles-Schwen T, Fazio RH. Choosing social situations: The relation between automatically-activated racial attitudes and anticipated comfort interacting with African Americans. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2003;29:170–182. doi: 10.1177/0146167202239042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Towles-Schwen T, Fazio RH. Automatically activated racial attitudes as predictors of the success of interracial roommate relationships. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2006;42:698–705. [Google Scholar]

- Waller NG, Kojetin BA, Bouchard TJ, Jr, Lykken DT, Tellegen A. Genetic and environmental influences on religious interests, attitudes and values: A study of twins reared apart and together. Psychological Science. 1990;1:138–142. [Google Scholar]

- Waters A, Carter B, Robinson J, Wetter D, Lam C, Cinciripini P. Implicit attitudes to smoking are associated with craving and dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2007;91:178–186. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicker AW. Attitudes versus actions: The relationship of verbal and overt behavioral responses to attitude objects. Journal of Social Issues. 1969;25:41–78. [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Cox WM, Field M, Fadardi JS, Palfai TP, Schoenmakers T, Stacy AW. The search for new ways to change implicit alcohol-related cognitions in heavy drinkers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2006a;30:320–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2006.00037.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, De Jong PJ, Havermans R, Jelicic M. How to change implicit drug-related cognitions in prevention: a transdisciplinary integration of findings from experimental psychopathology, social cognition, memory and learning psychology. Substance Use and Misuse. 2004;39:1625–1684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Gunning WB, Sergeant JA. Do young children of alcoholics hold more positive or negative alcohol-related expectancies than controls? Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 1998;22:1855–1863. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiers RW, Houben K, Smulders FTY, Conrod PJ, Jones BT. To drink or not to drink: The role of automatic and controlled processes in the etiology of alcohol-related problems. In: Wiers RW, Stacy AW, editors. Handbook of implicit cognition and addiction. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006b. pp. 339–361. [Google Scholar]

- Zentner M, Renaud O. Origins of adolescents’ ideal self: An intergenerational perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:557–574. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.3.557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]