Abstract

Objective

Anorectal malignant melanoma (AMM) is frequently subjected to misdiagnosis. Here the effect of misdiagnosis on the prognosis of AMM was investigated.

Methods

Between 1995 and 2007, 79 patients managed for AMM were reviewed; 46 (58.23%) of them had been misdiagnosed during the symptoms, while 33 (41.77%) cases had been diagnosed exactly not more than 1 week after the first visit. Diseases misdiagnosed were categorized as cancer, hemorrhoids, polyps and other diseases. Data were statistically analyzed by using the life tables and Kaplan–Meier curves. The software used was SPSS 16.0 for Windows.

Results

The 1-, 2-, 3- and 5-year survival rates of AMM patients were 58, 33, 24 and 16%, respectively, and the median survival time was 14.0 months; 1-, 2-, 3- and 5-year survival rates of the misdiagnosed patients were 61, 22, 22 and 11%, respectively, and the median survival time was 14.0 months; 1-, 2-, 3- and 5-year survival rates of the patients not misdiagnosed were 55, 44, 25 and 25%, respectively, and the median survival time was 12.0 months. Analyses based on Kaplan–Meier curves revealed no significant effect of misdiagnosis on the survival of AMM patients (P > 0.05). Nevertheless, the diseases misdiagnosed significantly affect the prognosis (P = 0.009); AMM misdiagnosed as hemorrhoids had a poor prognosis, with a 1-year survival rate of only 29% and the median survival of only 6.0 months.

Conclusions

The misdiagnosed patients had relatively poor prognosis, but the effect of misdiagnosis on the prognosis was not significant; however, misdiagnosis of AMM as hemorrhoids seriously affected the prognosis.

Keywords: Melanoma, Anal canal, Rectum, Survival, Misdiagnosis

Introduction

Anorectal malignant melanoma (AMM) is a very rare and highly malignant neoplasm. It accounts for 1% of all melanoma manifestations and approximately 0.5% of all colorectal and anal cancers (Ulmer et al. 2002; Roumen 1996). According to studies, AMM is a neuroectodermal neoplasm originating from the melanoblastic cells of the mucosal surface (Truzzi et al. 2008; Balthazar and Javors 1975). The traditional treatment for this rare AMM neoplasm tends to be radiotherapy-resistant and shows a poor response to chemotherapy (Stevens and McKay 2006; Yap and Neary 2004; Kim et al. 2004; Ballo et al. 2002). Until now, surgical management has been the main treatment, and there are basically two different surgical treatment strategies for AMM, namely, aggressive treatment with abdominoperineal resection (APR) and a sphincter-saving procedure with local excision (LE).

However, the disease is characterized by an early systemic spread and generally poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate estimated between 4.6 and 25% (Roumen 1996; Malik et al. 2002; Brady et al. 1995; Thibault et al. 1997; Konstadoulakis et al. 1995). One reason is that AMM usually presents as a polypoidal lesion projecting into the anorectal lumen and locates in the dentate line, which is always misdiagnosed as hemorrhoids and polyp (Heyn et al. 2007; Ceccopieri et al. 2000; Biyikoglu et al. 2007; Felz et al. 2001), thus making the treatment difficult. Since misdiagnosis often causes a delay of timely treatment, to elucidate the effect of misdiagnosis on AMM’s prognosis is important. However, research in this regard has not been reported as yet. Therefore, we do a retrospective study to identify the survival function of AMM and to investigate the effect of misdiagnosis on AMM’s prognosis.

Patients and methods

Between 1995 and 2007, 79 patients with AMM were diagnosed and treated at the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University and Sun Yat-Sen University Cancer Center. The records of all patients were retrospectively reviewed. There were 32 males and 47 females; their ages ranged from 29 to 80 years (54.39 ± 12.26 years), duration of symptoms ranged from 1 to 24 months (6.13 ± 6.42 months), maximal diameter of tumor ranged from 0.5 to 10 cm (3.82 ± 1.84 cm), and 76 cases of tumor were located within 6 cm of the anal rim. There were 72 (91.13%) cases of surgical treatment, and 7 (8.86%) cases of other treatments; 18 (25.0%) cases underwent local resection (LE), 49 (68.06%) cases underwent abdominoperineal resection (APR), and 5 (6.94%) cases underwent other procedures.

Forty-six (58.23%) of them had been misdiagnosed during symptoms, while 33 (41.77%) cases had been diagnosed exactly not more than 1 week after the first visit. Diseases misdiagnosed were categorized as cancer, hemorrhoids, polyps and other diseases (such as proctoptosis and moles); 23 of the 46 patients with AMM were misdiagnosed with cancer, 13 with hemorrhoids, 4 with rectal polyps and 6 with other diseases. Maximal diameter of tumor and distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis were compared.

Follow-up was documented until April 2008. The life table was used to find out the survival function, and Kaplan–Meier analysis was performed between the misdiagnosed group and the diagnosed-in-time group; the categories of diseases misdiagnosed were also compared by using the log rank test of Kaplan–Meier. SPSS 16.0 for Windows software package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois) was used. Differences of P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Results

The maximal diameter of tumor in the misdiagnosed group was 4.06 (SEM = 1.88) cm as compared with 3.45 (SEM = 1.73) cm in the not-misdiagnosed group (P = 0.237); the distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis in the misdiagnosed group was 14 (30.43%) cases as compared with 8 (24.24%) cases in the not-misdiagnosed group (P = 0.545) (Table 1). It was a surprise that 6 of 13 (46.2%) patients misdiagnosed with hemorrhoids had distant metastasis, while 6 of 23 (26.1%) were in the cancer group, 1 of 4 was in the polyps group, and 1 of 6 was in the other diseases group. However, no significant difference was found in the maximal diameter of tumor and metastasis between the misdiagnosed diseases (Table 2).

Table 1.

Survival function, metastasis and tumor diameter of patients with AMM

| Survival rate | Metastasis | Tumor diameter (cm) (SEM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1-Year (%) | 2-Years (%) | 3-Years (%) | 5-Years (%) | |||

| Total | 58 | 33 | 24 | 16 | 22/79 (28%) | 3.82 (1.84) |

| Misdiagnosis | 61 | 22 | 22 | 11 | 14/46 (30%) | 4.06 (1.88) |

| No-misdiagnosis | 55 | 44 | 25 | 25 | 8/33 (24%) | 3.45 (1.73) |

No significance difference were found between misdiagnosis and no-misdiagnosis in survival function (P = 0.555), metastasis (P = 0.545) and maximal diameter of tumor (P = 0.237)

Table 2.

Effect of misdiagnosed diseases on the prognosis of AMM

| Misdiagnosed diseases | Metastasis | Tumor diameter (cm) (SEM) | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| P value | P value | P value | |

| Cancer versus hemorrhoids | 6/23 versus 6/13 | 4.36 (1.61) versus 4.26 (2.32) | 0.026 |

| 0.220 | 0.814 | ||

| Cancer versus polyps | 6/23 versus 1/4 | 4.36 (1.61) versus 3.28 (0.64) | 0.599 |

| 0.963 | 0.204 | ||

| Cancer versus others | 6/23 versus 1/6 | 4.36 (1.61) versus 2.88 (2.46) | 0.061 |

| 0.631 | 0.136 | ||

| Hemorrhoids versus polyps | 6/23 versus 6/13 | 4.26 (2.32) versus 3.28 (0.64) | 0.176 |

| 0.452 | 0.322 | ||

| Hemorrhoids versus others | 6/23 versus 6/13 | 4.36 (1.61) versus 2.88 (2.46) | 0.016 |

| 0.216 | 0.422 | ||

| Polyps versus others | 6/23 versus 6/13 | 3.28 (0.64) versus 2.88 (2.46) | 0.207 |

| 0.747 | 0.764 |

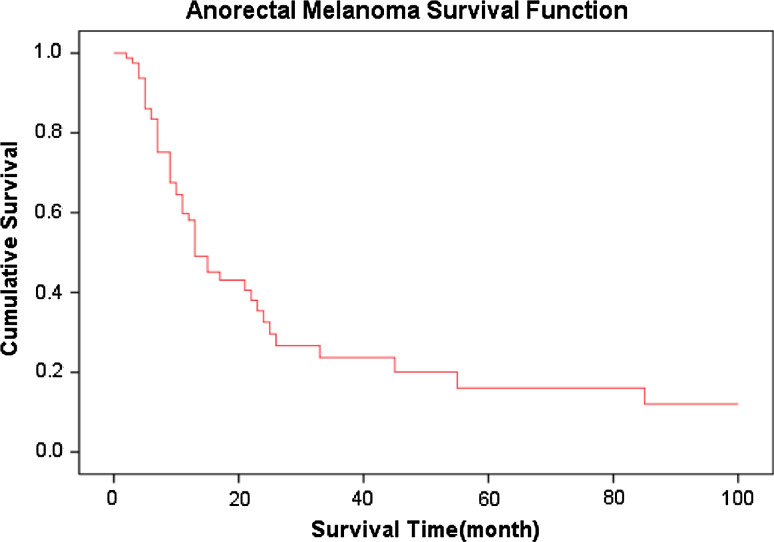

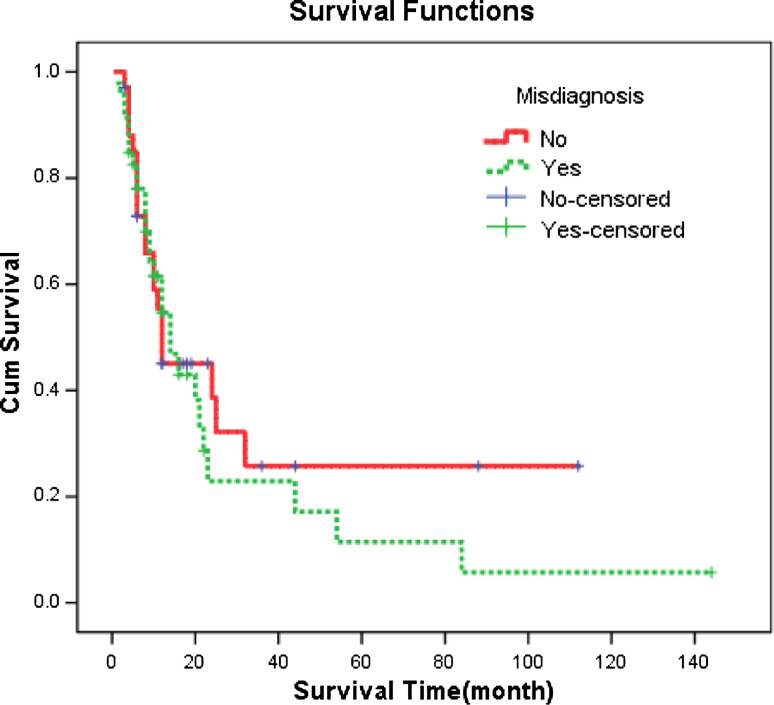

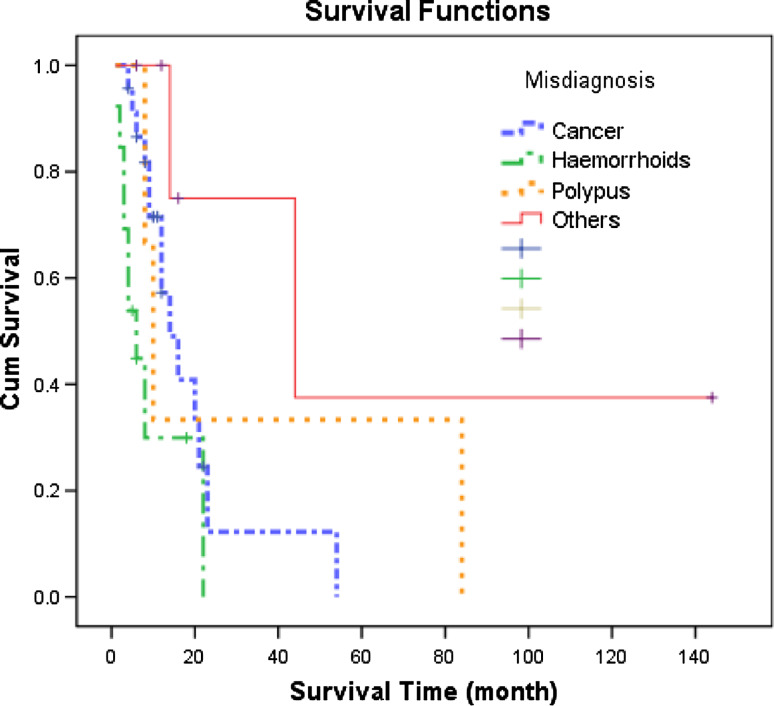

The follow-up was 2–144 months, and 1-, 2-, 3- and 5-year survival rates of AMM were 58, 33, 24 and 16%, respectively, and the median survival time was 14.0 months (Fig. 1). The 1-, 2-, 3- and 5-year survival rates of the misdiagnosed patients were 61, 22, 22 and 11%, respectively, and the median survival was 14.0 months. The 1-, 2-, 3- and 5-year survival rates of the patients not misdiagnosed were 55, 44, 25 and 25%, respectively, and the median survival was 12.0 months (Table 1). According to Kaplan–Meier survival analyses, P value was 0.555 as indicated by log rank testing weighed by time, showing no significant effect of misdiagnosis on the survival of AMM patients (Fig. 2). Nevertheless, analysis of the effect of the categories of diseases misdiagnosed on the prognosis revealed significant effect (P = 0.009). Specifically, the results suggested that misdiagnosis of AMM as hemorrhoids affected the prognosis significantly (Table 2) (Fig. 3); 8 of the 13 cases of AMM misdiagnosed as hemorrhoids died within 8 months, with a 1-year survival rate of only 29% and the median survival of only 6.0 months.

Fig. 1.

Cumulative survival curve of anorectal malignant melanoma

Fig. 2.

Cumulative survival curves reflecting the effect of misdiagnosis on anorectal malignant melanoma

Fig. 3.

Cumulative survival curves reflecting the effect of the categories of diseases misdiagnosed on anorectal malignant melanoma

Discussion

Primary malignant melanoma, accounting for 1–2% of all malignant tumors, may involve various sites of the body, but frequently occurs in the skin, followed by the eyes, anus and rectum (Hussein 2008). It is reported that AMM accounts for <1% of malignant melanomas and <4% of malignant anorectal tumors (Goldman et al. 1990). Malignant melanoma is derived from melanocytes by malignant change; there are great numbers of melanocytes in the annuliform area and mucous membranes of the anal canal; therefore, most malignant melanocytes originate from the anal canal, while some originate from the inferior end of the rectum and the rectosigmoid conjunction.

This retrospective study confirms the poor prognosis of AMM. The overall 1-, 2-, 3-, and 5-year survival rates for AMM are 58, 33, 24 and 16%, respectively, which are similar to Malik’s report (Malik et al. 2004), whose review of patient records over the past 20 years yielded 19 patients who underwent operations with a 5-year survival rate of about 21%, and better than some studies which reported 5-year survival rates for AMM <10% (Wanebo et al. 1981; Slingluff et al. 1990). However, it is much worse than most other cases of cancer survival, such as rectal cancer.

Initial symptoms of AMM frequently include hemafecia, asymptomatic local anorectal masses and changes in defecation habits. Therefore, AMM is prone to be misdiagnosed as hemorrhoids or anorectal cancer. The misdiagnosis rate of AMM was reported to be up to 80% (mainly as rectal or anal cancer) (Pessaux et al. 2004). After statistical analyses of 79 cases of AMM, we found misdiagnoses in 46 cases (23 as carcinoma), and one-half of the patients presenting with symptoms were misdiagnosed as having benign diseases. Since melanoma is highly malignant, it is extremely imperative to reduce the rate of misdiagnosis as well as the delay in timely treatment (Ceccopieri et al. 2000).

Despite the misdiagnosis-prone characteristic of AMM, a univariate analysis did not indicate significant effect of misdiagnosis on the prognosis of AMM, nevertheless, further analyses showed that the categories of diseases misdiagnosed affected the prognosis of AMM in this study. Diseases misdiagnosed were categorized as cancer, hemorrhoids, polyps and others. According to clinical experience, misdiagnosing AMM as cancer or polyps will not delay the clinical treatment of AMM. On the other hand, hemorrhoids are a common and frequent disease, the most common symptoms of which are hemafecia and anal masses, and therefore it is a common cause for misdiagnosis of AMM (Fine et al. 1999). Hemorrhoids do not necessarily require immediate surgical treatment and are prone to be neglected by both the patient and the surgeon. When considering that some of the patients with hemorrhoids chose Chinese medicine in this study, the delay in time would be longer. Therefore, AMM misdiagnosed as hemorrhoids will affect AMM’s prognosis, which suggests that hemorrhoids should be diagnosed with caution.

How does the delay of diagnosis affect the prognosis of AMM? The tumor development should have occurred. This study found the maximal diameter of tumor in the misdiagnosed group was longer than those in the not-misdiagnosed group (4.06 vs. 3.45 cm), and distant metastasis at the time of diagnosis in the misdiagnosed group was more than in the not-misdiagnosed group (30.43 vs. 24.24%), although no notable differences were found. The most number (6/13) of distant metastasis cases are shown when AMM misdiagnosed as hemorrhoids corresponds to the worse survival. However, no significant differences were found when compared to the hemorrhoids group with cancer, polyps and others’ groups in tumor diameter and metastasis (Table 2), the most important reason may be the few cases, therefore, multicenter surveys need to be investigated further.

References

- Ballo MT, Gershenwald JE, Zagars GK, Lee JE, Mansfield PF, Strom EA, Bedikian AY, Kim KB, Papadopoulos NE, Prieto VG, Ross MI (2002) Sphincter-sparing local excision and adjuvant radiation for anal–rectal melanoma. J Clin Oncol 20(23):4555–4558. doi:10.1200/JCO.2002.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balthazar EJ, Javors B (1975) The radiology corner. Anorectal melanoma. Am J Gastroenterol 63(1):79–83 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biyikoglu I, Ozturk ZA, Koklu S, Babali A, Akay H, Filik L, Basat O, Ozer H, Ozer E (2007) Primary anorectal malignant melanoma: two case reports and review of the literature. Clin Colorectal Cancer 6(7):532–535. doi:10.3816/CCC.2007.n.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady MS, Kavolius JP, Quan SH (1995) Anorectal melanoma. A 64-year experience at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center. Dis Colon Rectum 38(2):146–151. doi:10.1007/BF02052442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceccopieri B, Marcomin AR, Vitagliano F, Fragapane P (2000) Primary anorectal malignant melanoma: report of two cases. Tumori 86(4):356–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felz MW, Winburn GB, Kallab AM, Lee JR (2001) Anal melanoma: an aggressive malignancy masquerading as hemorrhoids. South Med J 94(9):880–885 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fine KD, Nelson AC, Ellington RT, Mossburg A (1999) Comparison of the color of fecal blood with the anatomical location of gastrointestinal bleeding lesions: potential misdiagnosis using only flexible sigmoidoscopy for bright red blood per rectum. Am J Gastroenterol 94(11):3202–3210. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01519.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldman S, Glimelius B, Pahlman L (1990) Anorectal malignant melanoma in Sweden. Report of 49 patients. Dis Colon Rectum 33(10):874–877. doi:10.1007/BF02051925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyn J, Placzek M, Ozimek A, Baumgaertner AK, Siebeck M, Volkenandt M (2007) Malignant melanoma of the anal region. Clin Exp Dermatol 32(5):603–607. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02353.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussein MR (2008) Extracutaneous malignant melanomas. Cancer Invest 26(5):516–534. doi:10.1080/07357900701781762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KB, Sanguino AM, Hodges C, Papadopoulos NE, Eton O, Camacho LH, Broemeling LD, Johnson MM, Ballo MT, Ross MI, Gershenwald JE, Lee JE, Mansfield PF, Prieto VG, Bedikian AY (2004) Biochemotherapy in patients with metastatic anorectal mucosal melanoma. Cancer 100(7):1478–1483. doi:10.1002/cncr.20113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konstadoulakis MM, Ricaniadis N, Walsh D, Karakousis CP (1995) Malignant melanoma of the anorectal region. J Surg Oncol 58(2):118–120. doi:10.1002/jso.2930580209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik A, Hull TL, Milsom J (2002) Long-term survivor of anorectal melanoma: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 45(10):1412–1415. doi:10.1007/s10350-004-6435-2 discussion 1415-1417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malik A, Hull TL, Floruta C (2004) What is the best surgical treatment for anorectal melanoma? Int J Colorectal Dis 19(2):121–123. doi:10.1007/s00384-003-0526-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pessaux P, Pocard M, Elias D, Duvillard P, Avril MF, Zimmerman P, Lasser P (2004) Surgical management of primary anorectal melanoma. Br J Surg 91(9):1183–1187. doi:10.1002/bjs.4592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roumen RM (1996) Anorectal melanoma in The Netherlands: a report of 63 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol 22(6):598–601. doi:10.1016/S0748-7983(96)92346-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slingluff CL Jr, Vollmer RT, Seigler HF (1990) Anorectal melanoma: clinical characteristics and results of surgical management in twenty-four patients. Surgery 107(1):1–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens G, McKay MJ (2006) Dispelling the myths surrounding radiotherapy for treatment of cutaneous melanoma. Lancet Oncol 7(7):575–583. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(06)70758-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thibault C, Sagar P, Nivatvongs S, Ilstrup DM, Wolff BG (1997) Anorectal melanoma—an incurable disease? Dis Colon Rectum 40(6):661–668. doi:10.1007/BF02140894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truzzi F, Marconi A, Lotti R, Dallaglio K, French LE, Hempstead BL, Pincelli C (2008) Neurotrophins and their receptors stimulate melanoma cell proliferation and migration. J Invest Dermatol 128(8):2031–2040. doi:10.1038/jid.2008.21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulmer A, Metzger S, Fierlbeck G (2002) Successful palliation of stenosing anorectal melanoma by intratumoral injections with natural interferon-beta. Melanoma Res 12(4):395–398. doi:10.1097/00008390-200208000-00013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wanebo HJ, Woodruff JM, Farr GH, Quan SH (1981) Anorectal melanoma. Cancer 47(7):1891–1900. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19810401)47:7%3c1891:AID-CNCR2820470730%3e3.0.CO;2-K [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap LB, Neary P (2004) A comparison of wide local excision with abdominoperineal resection in anorectal melanoma. Melanoma Res 14(2):147–150. doi:10.1097/00008390-200404000-00012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]