Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis cytochrome P450 enzymes (P450, CYP) attract ongoing interest for their pharmacological development potential, as evidenced by the activity of antifungal azole drugs that inhibit sterol 14α-demethylase CYP51 in fungi, tightly bind M. tuberculosis CYP enzymes, and display inhibitory potential against latent and multi drug resistant forms of tuberculosis both in vitro and in tuberculosis-infected mice. Although “piggy-backing” onto existing antifungal drug development programs would have obvious practical and economic benefits, the substantial differences between fungal CYP51 and potential CYP targets in M. tuberculosis are driving direct screening efforts against CYP enzymes with the ultimate goal of developing potent CYP-specific inhibitors and/or molecular probes to address M. tuberculosis biology. The property of CYP enzymes to shift the ferric heme Fe Soret band in response to ligand binding provides the basis for an experimental platform for high throughput screening (HTS) of compound libraries to select chemotypes with high binding affinities to the target. Newly discovered compounds can be evaluated in in vitro assays or in vivo disease models for inhibitory/therapeutic effects. The best inhibitors in complex with the target protein can be further characterized by x-ray crystallography. In conjunction with knowledge about compound inhibition potential, detailed structural characterization of the protein-inhibitor binding mode can guide lead optimization strategies to assist drug design. This unit includes protocols for compound library screening, analysis of inhibitory potential of the screen hits, and co-crystallization of top hits with the target CYP. Support protocols are provided for expression and purification of soluble CYP enzymes.

Cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes are heme thiolate-containing proteins which play important roles in all kingdoms of life, from bacteria to mammals (Ortiz de Montellano, 2005). CYP enzymes are involved in lipid, vitamin and xenobiotic metabolism in eukaryotes, and in the degradation of hydrocarbons and biosynthesis of secondary metabolites in prokaryotes. They are validated drug targets in fungi. One well-established P450 drug target is sterol 14α-demethylase (CYP51), required for the biosynthesis of membrane sterols, including cholesterol in animals, ergosterol in fungi, and a variety of C-24-modified sterols in plant and protozoa (Aoyama, 2005). Twenty CYP enzymes have been identified in the 4.4 Mb genome of the pathogenic bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Cole et al., 1998). Accumulating evidence implicates their importance in virulence, host infection and pathogen viability (Chang et al., 2007; McLean et al., 2008; Recchi et al., 2003; Sassetti and Rubin, 2003). Although the exact biological functions of Mycobacterium CYP enzymes are still unknown, they attract ongoing interest for their pharmacological development potential, evidenced by the activity of antifungal azole drugs such as fluconazole, econazole and clotrimazole. These drugs inhibit sterol 14α-demethylase CYP51 in fungi (Sheehan et al., 1999), tightly bind M. tuberculosis CYP enzymes (McLean et al., 2002; Ouellet et al., 2008), and display inhibitory potential against latent and multi drug resistant forms of tuberculosis both in vitro and in tuberculosis-infected mice (Ahmad et al., 2005; Ahmad et al., 2006a; Ahmad et al., 2006b; Ahmad et al., 2006c; Banfi et al., 2006; Byrne et al., 2007).

Although “piggy-backing” onto existing antifungal drug development programs would have obvious practical and economic benefits (Nwaka and Hudson, 2006), the substantial differences between fungal CYP51 and other potential CYP targets in pathogenic organisms, including M. tuberculosis, impel direct screening efforts against CYP enzymes with the ultimate goal of developing potent CYP-specific inhibitors and molecular probes to aid in the elucidation of biological functions of these enzymes. Toward this goal, the property of CYP enzymes to shift the ferric heme Fe Soret band in response to ligand binding (Schenkman et al., 1967) provides the basis for an experimental platform for high throughput screening (HTS) of compound libraries to select chemotypes with high binding affinities to the target. Newly discovered compounds can be evaluated in the relevant in vitro assays or in vivo disease models for inhibitory/therapeutic effects. The best inhibitors in complex with the target protein can be further characterized by x-ray crystallography. This approach has been successfully applied to CYP51 of M. tuberculosis, resulting in identification of novel inhibitory scaffolds and molecular probes and shedding new light on the prospective metabolic role of bacterial CYP51 (Chen et al., 2009; Nasser Eddine et al., 2008; Podust et al., 2007).

Presented in this unit are four basic and two support protocols for compound library screening, analysis of inhibitory potential of the screen hits, and co-crystallization of top hits with the target CYP protein. The high throughput screening assay (Basic Protocol 1) conducted in a 384-well plate format is an indispensible method for selection of high affinity hits from libraries that may contain tens of thousands of compounds. In vitro inhibitory assays in broth culture (Basic Protocol 2) and mouse macrophage cells (Basic Protocol 3) provide tools to monitor treated M. tuberculosis cells in evaluating the inhibitory potential of screen hits. Finally, co-crystallization of the target with a screen hit, followed by determination of the x-ray structure (Basic Protocol 4), elucidate the binding mode of the inhibitor to provide feedback for lead optimization strategies. Two support protocols are provided for expression and purification of soluble bacterial CYP targets for co-crystallization experiments. Completion of this interdisciplinary project requires specific expertise and equipment. Accordingly, we find it efficient to conduct such work in collaboration with specialized laboratory units or facilities.

BASIC PROTOCOL 1

HIGH THROUGHPUT BINDING ASSAY

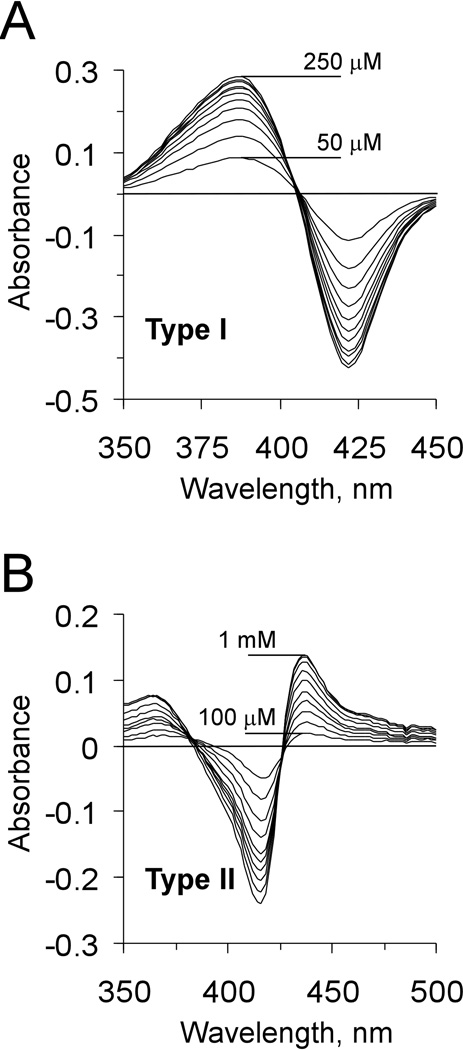

The HTS assay is based on the optical spectral properties of CYP enzymes to elicit both type I and type II binding spectra (Schenkman et al., 1967). Type I changes show a peak at ~390 nm and a trough at ~420 nm in the difference spectra (Figure 1A), indicating expulsion of the heme Fe axial water ligand from the Fe coordination sphere and the transition of the ferric heme Fe from the low-spin hexa-coordinated to the high-spin penta-coordinated state. Type II changes show a trough at ~416 nm and a peak at ~436 nm in the difference spectra (Figure 1B), indicating replacement of a water molecule, a weak axial ligand, with a stronger one, usually one having a nitrogen-containing aliphatic or aromatic group. The concentration dependence of the spectral changes allows the binding affinities of the ligand to be estimated.

Figure 1. Examples of the type I and type II difference spectra.

(A) Type I spectra resulted from the titration of CYP51 of M. tuberculosis with estriol (KD of 100 µM). (B) Type II spectra resulted from the titration with 4-phenylimidazole (KD of 1.3 mM) (Podust et al., 2007).

For library screening, test compounds, each at 10 mM stock concentration in DMSO, are solubilized in assay buffer in 384-well micro titer plates in columns 1 to 22; columns 23 and 24 are used for the reference compound and buffer alone. After the addition of the target protein to columns 1 to 23, changes in the visible region of the optical spectra, 350 through 450 nm, which occur in response to ligand binding, are monitored.

Material

HTS Assay Buffer (see recipe)

CYP of interest, 2 µM solution in the HTS Assay Buffer

384-well polypropylene deep-well plates for supply of protein solution (Corning, 3347)

384-well polystyrol plates for high throughput screening (Corning, 3702)

Reference compounds known to bind CYP of interest via type I and/or type II mechanism

Library compounds, 10 mM stock solutions in DMSO

384-well polypropylene plates for storage of library compounds in DMSO (Corning, 3657)

Aluminium foil with DMSO resistant cement for sealing compound plates (Corning, 6596)

Tween-20 (Sigma P9416)

Bovine Serum Albumin (ELISA grade, Sigma A7030)

Special equipment

16-channel dispenser automate (µFlo, BioTek)

Sciclone ALH-3000 pipetting robot equipped with 384-tip low volume head (CaliperLS)

Motorized 12-channel pipettes (Eppendorf AG)

Centrifuge (Eppendorf 5810R, rotor A-4-81)

Ultrasonic Waterbath (Transsonic 460, Elma)

384-well microtiterplate reader (SafireII, Tecan AG)

Plate preparation

Add 120 µl HTS Assay Buffer to each well of columns 1 to 22 of the deep-well polypropylene plate (Corning, 3347) using the automated dispenser. This amount should be sufficient to prepare five assay plates.

Using the pipetting robot, transfer 20 µl aliquots from the deep-well plate to the corresponding wells of the polystyrol assay plate (Corning, 3702).

- Add reference compounds, diluted in assay buffer to known IC-50 concentrations, to column 23 of the assay plate, and assay buffer alone to column 24 to serve as positive control and blank, respectively.The KD for reference compounds (and hence the amounts required for recording optimal absorption spectra) should be determined empirically by titration during assay development. Wells containing buffer only are essential for determining specific absorption spectra of CYP in absence of ligand and for background subtraction during the HTS Data Analysis step.

Add 0.4 µl of a library compound solubilized in DMSO to 10 mM

Seal the assay plate well using an aluminium plate cover.

Centrifuge plates at 1000 rpm for 1 minute at room temperature to remove air bubbles.

Sonicate plates for 5 min to allow suspensions of the most hydrophobic compounds to solubilize.

To analyze specific absorption spectra of compounds, read plates using a plate reader scanning from 350 to 450 nm with a step width of 10 nm (three reads per well).

Ligand binding scan

Add 20 µl of 2 µM CYP in HTS Assay Buffer in each well containing either test or reference compounds to a final protein concentration of 1 µM. Mix content of each well by three cycles of 10 µl aspiration and dispension.

Centrifuge plates and incubate for 10 min at room temperature.

Read plates using a plate reader scanning from 350 to 450 nm with a step width of 10 nm (three reads per well).

HTS data analysis

Export absorption scan data to an EXCEL spread sheet.

Subtract background spectra obtained for compound in the absence of protein, and protein in the absence of compound, from spectra recorded in presence of both protein and compound. Plot absorption values against wavelengths.

Superimpose curves obtained for reference compound with curves obtained for test compounds. Use characteristic absorption maxima and minima of reference spectra for automated spectra comparison and sorting spectra by peak heights in EXCEL. Identify novel ligands by curve similarity. If hit number exceeds 300, cluster structurally related hits and select representatives for further validation.

Hit validation

Validate identified hits with 10-fold increased input of CYP protein to achieve signal-to-noise ratio stronger than in the primary screen.

Dilute test compounds from 100 µM used in the primary screening to 10 µM. Dilute reference compounds to 10% of IC-50 value.

Select compounds which demonstrate absorption difference spectra comparable to the reference compounds taken at the lowest concentrations.

BASIC PROTOCOL 2

INHIBITION OF M.TUBERCULOSIS GROWTH IN LIQUID MEDIUM

Inhibition of M. tuberculosis growth in liquid medium can be monitored by the resazurin-based assay known as Alamar blue. The active blue component resazurin changes color to pink upon reduction to resorufin by enzymes in the electron transport system of living cells (O'Brien et al., 2000; Rasmussen, 1999). Inhibition of resazurin reduction indicates impairment of cellular metabolism. The assay is carried out using 96-well plates, allowing a large number of inhibitors to be tested in parallel by either objective (absorbance or fluorescence-based) or subjective (visual color reading) endpoint reading.

Material

Compounds of interest, 100 mM stock solutions in DMSO

Middlebrook 7H9 liquid medium with and without Tween-80 (see recipe)

96-well flat bottom plates, sterile (TC Microwell 96F from NUNC, 167008)

Hygromycin (Roche), 50 mg/ml

DMSO

Log phase culture of M.tuberculosis

Alamar Blue reagent (AbD Serotec, BUF012A)

20% Tween-80

0.22 µm pore membrane filter

Special equipment

Spectrometer

Incubator (37°C)

Microplate reader or digital camera

Dilution of test compounds

Dilute stock solution of test compounds to working concentrations ranging from 50 µM to 1 mM with sterile 7H9 medium devoid of Tween-80.

- Add 100 µl of each dilution, in triplicate, to wells in a sterile 96-well flat bottom plate.To minimize evaporation, add sterile deionized water to the wells around the perimeter.

For a positive control use hygromycin at a final concentration of 100 µg/ml. For a negative control use 7H9 medium alone.

Use dilutions of DMSO alone to address possible effects of solvent on Mycobacterium survival.

Treatment of M. tuberculosis with test compounds

Propagate M. tuberculosis in complete 7H9 medium to the optical density of 1.0 at 600 nm.

Make 1:25 dilution of this culture in 7H9 medium devoid of Tween-80

Add 100 µl of diluted culture to each well of the plate prepared in the previous recipe, “Dilution of test compounds” steps 2–4, to reach a final volume of 200 µl in each well.

Seal the plate with parafilm and incubate at 37°C for 96 h.

Alamar blue reaction

Prepare a 1:1 dilution of commercial 10× Alamar blue reagent in 20% Tween-80, dissolved in distilled deionized water.

Filter the solution by passing through a 0.22 µm pore membrane.

Add 50 µl of the freshly filtered solution to each well.

Seal the plate again with parafilm and incubate at 37°C for another 24 h.

Plate monitoring

Visually inspect wells for color change from blue to pink.

Read absorbance at 570 to 600 nm, or fluorescence with excitation at 563 nm and emission at 587 nm (Fai and Grant, 2009), with a microplate reader. Alternatively, record the result digitally with a camera.

BASIC PROTOCOL 3

INHIBITION OF M.TUBERCULOSIS GROWTH IN MACROPHAGE CELLS

In human disease, the initial stage of infection occurs when M. tuberculosis is inhaled and crosses the epithelial barriers of the alveoli to be taken up by host macrophages. Although macrophages are programmed to destroy invading pathogens, mycobacteria are able to circumvent microbicidal pathways and establish a safe haven inside macrophages, which thereby become the primary cells harboring and promoting the infection. A compound which could access and destroy bacteria residing in macrophages, or other cells, would have immense potential for future drug development. We have used a simplified in vitro macrophage infection model to test the activity of screen hits against phagocytosed mycobacteria.

Material

Tibia and femur bone marrow cells

Plastic Petri dishes (Sarstedt, # 821473), 92 mm in diameter

Bone marrow macrophage differentiation medium (500 ml)

Phosphate Buffer Saline (PBS)

96-well flat bottom plates, sterile (TC Microwell 96F from NUNC, 167008)

Macrophage infection medium (500 ml)

Log phase culture of M. tuberculosis

0.4 µm Needle

Compounds of interest, 100 mM stock solutions in DMSO

Isoniazid, 100 mM stock solution in H2O

Cell Lysis Buffer: 0.5% TritonX-100 in PBS

Dilution Buffer: 0.05% Tween-80 in PBS

Middlebrook 7H11 agar plates

Special equipment

Incubator, 37°C with 5% CO2

Spectrometer

Macrophage isolation and differentiation

Harvest bone marrow cells from tibia and femur of healthy 8–12 week old female C57/Bl6 mice as described in Basic Protocol 2 in Unit 14.1 of Current Protocols in Immunology.

Plate the cells at a density of 5×106 cells directly on the sterile plastic surface of Petri dishes, 92 mm in diameter, and incubate at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 3 days.

- Feed cells with 5 ml of differentiation medium and allow them to differentiate for 3 more days.In the presence of differentiation factors contained in the L929 cell component of the medium, monocytes adhere to the surface and differentiate into macrophages.

- Detach the cells by treatment with 5 ml of cold PBS buffer for 15 min. Count cells using a Neubauer counting chamber and plate at a density of 5×104 cells per well in a 96-well flat bottom plate. Add 100 µl of macrophage infection medium and incubate overnight at 37°C with 5% CO2.In the macrophage infection medium the primary cells do not multiply, hence the cell number remains the same throughout the experiment. Some cells do die during the course of infection but this number is very low.

Infection of macrophage cells with M. tuberculosis

Pellet cells from a log phase culture of M. tuberculosis in an eppendorf tube at 13000 rpm, 10 min, room temperature, and wash them twice in PBS buffer by re-suspension followed by pelleting.

Disperse the clumps of bacteria by passing the suspension 5–6 times through a 0.40 µm needle.

Quantify the number of bacteria by measuring absorbance at 580 nm. An OD of 0.1 ≈ 5×107 bacteria/ml.

- Dilute bacteria in macrophage infection medium and add 5 bacilli per macrophage cell to all wells in the 96-well plate. Incubate at 37°C for 4 h.Add bacilli on top of the macrophage cells, preferably in 50–100µl of medium, to ensure homogeneous infection. If a P3 safety level closed centrifuge is available, centrifuge the plates for 2 min at 700 rpm to ensure complete adherence of bacteria to the macrophage cells.

Rinse each well in the 96-well plate twice with PBS to remove non-phagocytosed M. tuberculosis bacilli.

- Dilute test compounds to working concentrations ranging from 0 to 100 µM with macrophage infection medium.It is important to limit DMSO concentration to 0.1%, the maximum cells can tolerate. Higher DMSO concentrations kill macrophage cells.

- Add 100–150 µl of freshly diluted test compounds in triplicate wells. As a positive control, use 50 µM isoniazid, and as a negative control use untreated infected cells. Seal the plate with parafilm and incubate at 37°C with 5% CO2.Observe wells periodically under the microscope for cell viability or detachment.

Assessment of colony forming units

Lyse macrophage cells with the Cell Lysis Buffer at days 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 after infection and plate serial dilutions in Dilution Buffer on 7H11 agar plates. Seal plates with parafilm and incubate at 37°C for 3 weeks.

Count distinct colonies on each plate. Plot the averaged data from triplicate plates against compound concentration.

BASIC PROTOCOL 4

CO-CRYSTALLIZATION OF CYP TARGET WITH SCREEN HITS

A great deal can be learned about target-inhibitor interactions through determination of the 3-D structure of a complex. This knowledge is beneficial for lead optimization to aid drug design. Basic Protocol 4 is not intended by any means to provide general instructions on crystal structure determination, but rather is limited to specific aspects of co-crystallization of bacterial CYP-inhibitor complexes. When a CYP of interest is expressed and purified (see Support Protocol 1), screening of crystallization conditions can be performed either manually on the laboratory bench using 24-well plates, or by using an automated nanoliter drop-setting robot operating 96-well plates. The latter is more productive, given that multiple screening hits may be tested, and that manual setup of 24-well plates is both time and material-consuming. A nanoliter drop-setting allows minimization of both consumption of protein and, more importantly, of test compounds, which are typically available in limited amounts.

Material

Purified CYP of interest, ~1 mM stock solution (see Support Protocol 1)

Compound of interest, 100 mM stock solutions in DMSO.

10 mM Tris HCl, pH 7.5

Crystallization screening kits in deep-well block format (Hampton Research): Crystal Screen (HR2-130), Index (HR2-134), PEG/Ion (HR2-139), and Grid Screen Salt (HR2-248)

96-well plates, non-sterile, no lid (compatible with the drop-setting robot)

Aluminium foil with DMSO resistant cement for re-sealing screen deep-well plates (Corning, 9596)

24-well VDX plates with sealant (Hampton Research, HR3-170)

Siliconized circle cover slides (Hampton Research, HR3-233)

Glycerol, 100%

Special equipment

Nanoliter drop setting robot Mosquito (TTP LabTech)

Temperature-controlled environment (20–25°C) for incubation of crystallization plates

Orbital Shaker

CryoTools (Hampton Research): long CryoTong, long CrystalWand, curved vial clamp, CrystalCap Holder (HR4-705), socket driver (HR4-706) for height adjustment, 1 L stainless steel dewar (HR4-699), CryoCane, tall 1 L dewar

Liquid nitrogen

CrystalCap Mounted CryoLoops of various sizes (Hampton Research)

Dry-shipper

Screening of crystallization conditions

- Mix protein from stock solution (see Support Protocol 1) with the inhibitor. Make final protein concentration 0.2 mM and use 1 to 2 molar excess of inhibitor over protein, depending on inhibitor solubility.To avoid direct contact between concentrated protein and organic solvent, mix first inhibitor with the required volume of 10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, and then add protein from the stock solution. Mix gently; do not vortex. Keep sample on ice. If inhibitor does not dissolve completely after protein is added, briefly spin sample down for a few seconds before screening.

- Screen protein-inhibitor solution against Crystal Screen, Index, PEG/Ion and Grid Screen Salt kits, available from Hampton Research in high throughput 96-deep-well format. In all, these kits contain 384 formulations, which typically will be sufficient to identify promising hits.Crystal Screen, Index and PEG/Ion screening kits are also available in traditional 10-ml format for manual screening. If an automated screening robot is to be used, make sure to receive proper training from an expert user or facility manager and follow the operation instructions. Use only consumables compatible with the instrument.

Transfer 100 µl aliquots from the deep-well screening kit to the corresponding wells of an appropriately labeled 96-well plate.

Transfer 2 µl aliquots of the protein-inhibitor solution into the 8 wells of the plastic sample holder, avoiding bubbles. This sample amount is sufficient to screen one 96-well plate, mixing 0.1 µl of sample with 0.1 µl of well solution.

Place the 96-well plate on the moving platform of the automated screening robot Mosquito between the sample plate and the adhesive cover positions.

If necessary, adjust the default settings in the hanging drop crystallization protocol. Begin the run.

Promptly remove plate from the platform and seal with the adhesive cover holding the drops.

- Incubate plates at 20–25°C in a temperature controlled environment. Visually monitor the drops for the next 2–3 days. Keep records for each screen using spreadsheets available on the Hampton Research web site.Protein concentration is approximately correct if ~ 50% of formulations in the screen form precipitate. After first screening, if too many or too few drops formed precipitate, adjust protein concentration by a factor of two. Then repeat screening.

Scaling up crystallization conditions

- Analyze positive screen hits. Expand each positive formulation in 24-well grids by varying concentrations of the formulation ingredients, exploring a wide range of pH using different buffers, and trying different varieties of components such as PEG, multivalent cations and salts. During optimization, crystallization conditions may diverge significantly from the original hit.It is impossible to predict which reagents will be needed for optimization of the crystallization conditions before you actually see the crystal. Fortunately, most reagents used in the screen kits are available from Hampton Research as stock solutions at concentrations optimal for mixing and shelf storage. Accordingly, if you choose to make stock solutions from scratch, use commercial concentrations as a guide.

Prepare the custom-designed formulations directly in the wells of a pre-greased 24-well plate combining concentrated stocks of reagents and adjusting the volume in each well to 1 ml with deionized water.

Fix the lid to the plate and attach the plate to the rotating platform of an orbital shaker. Mix solutions by rotating platform at 220 rpm for 15 min.

- Combine 2 µl of protein-inhibitor solution and 2 µl of well solution on a circular siliconized cover slide. Position the cover slide so that the drop hangs over the well solution, then seal it. It is possible to have multiple drops on a slide.With practice, 6–12 cover slides can be prepared simultaneously, then promptly sealed, one after the other. To dispense protein-inhibitor solution, use a motorized single channel 20 µl pipette in multiple dispensing mode.

Incubate plates in a 20–25°C temperature controlled environment, regularly recording observations for each crystallization tray.

Crystal harvesting, data collection and structure determination

Choose a crystallization drop with crystal(s) for harvest.

Prepare 100 µl of cryo-solution by combining 80 µl of solution from the chosen well with 20 µl of glycerol as a cryo-protectant. To obtain well solution, lift the cover slide gently, aspirate solution using a pipette, and promptly replace the slide.

Place a CrystalCap Holder inside a 1 L dewar filled with liquid nitrogen. Secure CrystalCap plastic vials in the holding platform and lower the platform using a socket driver for height adjustment until the vials are covered completely with liquid nitrogen.

Place an aluminium CryoCane into a tall 1L dewar filled with liquid nitrogen.

Using a large CryoLoop, test freeze the cryo-solution in the liquid nitrogen prior to mounting crystal(s). If the solution turns opaque, increase the concentration of glycerol until the solution remains glass-clear upon freezing.

Place 5–7 µl of the cryo-solution under the microscope on a siliconized cover slide.

Open the well containing the chosen crystal by lifting the cover slide. Flip the cover slide over and place it under the microscope next to the slide holding a drop of the cryo-solution.

Add 5 µl of well solution into the crystallization drop.

Pick up a crystal with an appropriately sized loop while separating it from precipitate debris. Dip it briefly into the drop of cryo-solution.

Transfer the loop quickly into the plastic vial containing liquid nitrogen and screw the vial closed with the CrystalCap.

- Transfer vials to the aluminium CryoCane in the dewar. When the CryoCane is filled, or when harvest is completed, it can be transferred to a dry-shipper for transportation to the data collection site.While harvesting crystals, it is important to notice if contact with cryo-solution compromises crystal integrity. If it does, modify cryo-solution by changing concentration or replacing cryo-protectant. Both glycerol and ethylene glycol are compatible with many formulations, including those containing high concentrations of salt, e.g., ammonium sulfate. With salt concentrations of 2.4 M or greater, cryo-protection may not be required. High molecular weight PEGs are not compatible with highly concentrated salts as they result in phase separation upon mixing. If success is still elusive, try a variety of oils available from Hampton Research. When using oils it is important to thoroughly remove the original liquid surrounding the crystal by gently dragging it through the oil drop.

Collect diffraction data on harvested crystals.

Use diffraction data for crystal structure determination, either by molecular replacement, if a search model with high sequence identity is available, or via obtaining experimental phases using heavy atom derivatives (see Support Protocol 2).

REAGENTS AND SOLUTIONS FOR BASIC PROTOCOLS

HTS Assay Buffer

50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 250 mM NaCl, 20% glycerol (v/v), 0.05% Tween-20 (v/v), 1 mM DTT

Middlebrook 7H9 Liquid Medium (complete)

| Water | 880 ml |

| Middlebrook 7H9 powder (from Difco) | 4.7 g |

| OADC (from BD Biosciences) | 100 ml |

| 20% Tween-80 | 2.5 ml |

Bone marrow macrophage differentiation medium

| Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium | 500 ml |

| L929 conditioned medium | 50 ml |

| Heat inactivated fetal calf serum | 50 ml |

| Heat inactivated Horse serum | 25 ml |

| 1 M Hepes pH ~7.0 | 5 ml |

| 100 mM Sodium Pyruvate | 5 ml |

| 200 mM L-glutamine | 5 ml |

Macrophage infection medium

| Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium | 500 ml |

| Heat inactivated fetal calf serum | 50 ml |

| Heat inactivated Horse serum | 25 ml |

| 1 M Hepes pH ~7.0 | 5 ml |

| 100 mM Sodium Pyruvate | 5 ml |

| 200 mM L-glutamine | 5 ml |

SUPPORT PROTOCOL 1

EXPRESSION AND PURIFICATION OF BACTERIAL CYP FOR SCREENING AND CRYSTALLIZATION

Although screening of the compound library can be performed using protein of virtually any degree of purity, for crystallization purity and conformational homogeneity of the protein sample are of paramount importance. Empirically we have developed basic expression and purification protocols, which, with small modifications, have worked well for a number of different microbial CYP crystals.

I. Bacterial CYP Expression

The expression protocol is based on the assumption that driving protein expression to the highest possible yield is not always beneficial for sample homogeneity. Boosting protein expression to the limit may result in a large fraction of misfolded protein which interferes with crystallization (Podust et al., 2004). Therefore, rich media, elevated temperatures, intensive aeration and high IPTG concentrations are to be avoided.

Materials

Expression vector encoding CYP of interest (see recipe)

HMS174(DE3) competent cells

Luria-Bertani (LB) medium

50% glycerol

5 M NaCl

0.5 M EDTA

1 M Tris-HCl, pH 7.5

2 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0

4 M imidazole

0.2 M phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) in ethanol

40–50 mg/ml antibiotics

1M thiamin

0.5 mM isopropyl β-D-thiogalactopyraniside (IPTG)

1 M δ-aminolevulinic acid

Expression medium (see recipe)

4000× Microelement Solution (see recipe)

Suspension Buffer (see recipe)

15-ml BD Tubes (BD Falcon™), sterile

50-ml BD Tubes (BD Falcon™), sterile

250-ml culture flask

2.8-L standard Fernbach flasks (do not use baffled flasks)

Centrifuge bottles, sterilized

Special equipment

Hot plate set at 42°C

Incubator containing a platform shaker

Ultra-centrifuge

Transformation

Transfer 0.5 µl of expression vector into 50 µl of HMS174(DE3) competent cells in a 1.5-ml eppendorf tube.

Incubate on ice for at least 20 min.

Heat shock by placing eppendorf tube in 42°C for 2 min.

Return tube onto ice for 2 min.

Transfer transformed cells into 2 ml of sterile LB media in a 15-ml sterile tube, using a sterile pipette.

Close the lid on the tube enough to keep it from coming off but leave it loose enough to allow for exchange of gases.

Incubate 15-ml tube culture on a platform shaker for 1 hour at 240 rpm, 37°C.

Centrifuge 15-ml tube culture for 5 min at 3000 rpm, 4°C.

Remove 1.8 ml of supernatant using a sterile pipette.

- Resuspend cell pellet carefully into the remaining 200 µl of supernatant with a sterile pipette.Steps 5–10 are not necessary if plasmid has ampicillin resistance only.

Overnight Culture

Combine 100 µl of antibiotic and either 50 µl or 200 µl of transformed cells (from Transformation step 4 or 10) with 100 ml of sterilized LB medium in a 250-ml culture flask.

Incubate the culture on a platform shaker overnight at 240 rpm, 37°C.

Expression Culture

- Combine 1 ml of thiamin, 1 ml of antibiotic, 250 µl of Microelement Solution and 10 ml of the overnight culture with 1 L of sterilized expression medium in a 2.8-L Fernbach flask.Expression medium is LB-based medium supplemented with phosphate buffer and glycerol. Phosphate buffer is critical for P450 expression. Glycerol is a precursor in heme biosynthesis and is optional.

Incubate the 1 L expression culture on a platform shaker for 4.5 hours at 240 rpm, 37°C.

Reduce the incubation temperature to 25°C and continue incubation on a platform shaker for 30 minutes at 240 rpm.

Induce expression with 0.5 ml of IPTG. Additionally add 1 ml of antibiotic stock solution and 1ml of δ-aminolevulinic acid.

Incubate on a platform shaker for 20 hours at 140–180 rpm, 25°C.

Harvest

Centrifuge expression cultures for 15 min at 5000 rpm, 4°C in centrifuge containers.

Discard supernatant and place centrifuge containers with cell pellets on ice.

Carefully resuspend cell pellets and combine together in 100 to 200 ml of Suspension buffer.

Transfer cells to a 250-ml plastic container and freeze at −80°C.

II. Bacterial CYP Purification

This three-step purification protocol is designed for purification of soluble CYP enzymes carrying a histidine tag on either the N-terminus or C-terminus from a 6 L of bacterial culture. The protocol is devoid of intermediate freezing, thawing and dialysis steps, and can be completed in 2–3 days. Detergents, reducing agents and phosphate buffers are to be avoided unless required for protein integrity. Once detergent has been in contact with the protein it is virtually impossible to completely remove. Phosphates tend to form salt crystals under many crystallization conditions and thus interfere with the visual inspection of the crystallization drops.

The three chromatographic steps employed in the following protocol are nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose, Ni-NTA, (QIAGEN), S-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) in a flow-through regime, and Q-Sepharose (Amersham Biosciences) for binding and elution in a salt gradient. All steps are carried out at 4°C. At all other times protein is kept on ice whenever possible. Note that as a single purification protocol cannot cover all conditions that may arise for different CYPs, empirical protocol modifications may be necessary for particular CYPs.

Materials

Ni-NTA column, 20 ml

S-Sepharose, 40 ml

Q-Sepharose, 40 ml

Crude protein extract stored in Suspension buffer at −80°C

250-ml metal sonicator cup

60-mL ultra-centrifuge tubes

Ni-NTA Equilibration buffer (see recipe)

Ni-NTA High-Salt Wash Buffer (see recipe)

Ni-NTA No-Salt Wash Buffer (see recipe)

Ni-NTA Elution Buffer (see recipe)

S-Sepharose/Q-Sepharose Equilibration Buffer (see recipe)

S-Sepharose/Q-Sepharose Wash Buffer (see recipe)

Q-Sepharose Elution Buffers (see recipe)

Special equipment

Sonicator

Electronic Balance

Ultra-Centrifuge

Gradient mixer

Magnetic stirrer

Magnetic Flea

Fraction collector

Pump

Centriprep YM-50 centrifugal filter device (Millipore)

Protein Preparation

Thaw the container with resuspended cells, which has been stored at −80°C.

Transfer contents to a 250-ml metal sonicator cup.

Place large sonicator tip into protein solution and sonicate 5× for 1 min at ~40% power, alternating with 1 minute of cooling on ice.

Transfer protein solution evenly to four 60-ml sterile centrifuge tubes. Balance tubes carefully using an electronic balance.

Centrifuge protein solution for 40 minutes at 35000 rpm, 4°C to remove cell debris.

Transfer supernatant to a 250-ml Erlenmeyer flask. This is to be loaded onto the Ni-NTA column.

Ni-NTA Purification

Load crude cell extract from Protein Preparation step 6 onto the Ni-NTA column pre-equilibrated with Ni-NTA Equilibration Buffer.

Allow 5 column volumes of Ni-NTA High-Salt Wash Buffer to flow through column followed by 5 column volumes of Ni-NTA No-Salt Wash Buffer.

Elute protein with 100 ml of Ni-NTA Elution Buffer into test tubes using a fraction collector. Combine red colored fractions and load them onto S-Sepharose.

Flow-through chromatography on S-Sepharose

- Pass the eluate from the Ni-NTA column through pre-equilibrated S-Sepharose and load flow-through fractions onto pre-equilibrated Q-Sepharose.Both columns can be connected tail-to-head until all the red color is washed out from S-Sepharose and accumulated on the top of the Q-Sepharose.

Allow enough S-Sepharose/Q-Sepharose Wash Buffer to travel through the S-Sepharose column so that the colored protein is removed from the column and connecting tubing is clear. Disconnect the columns.

Q-Sepharose Purification

- Allow 5 to 10 column volumes of S-Sepharose/Q-Sepharose Wash Buffer to flow through the Q-Sepharose column.Wash can be performed overnight.

- Elute protein using 10 column volumes of a 0 to 0.5 M NaCl gradient.Most CYPs bind Q-Sepharose at pH 7.5. However, there is an instance of Trypanosoma cruzi CYP51 which binds S-Sepharose instead (Chen et al., 2009).

- Analyze fractions containing CYP on the SDS-PAGE. Pool the most pure fractions together.Do not dialyze protein prior to concentrating. The salt concentration at which protein has been eluted from the ion-exchange column by definition compensates for the protein surface charges and allows for effortless concentration of sample up to >1 mM.

- Concentrate protein to ~1 mM using a Centriprep YM-50 centrifugal filter device.YM-50 cellulose membrane provides a high flow rate and allows the concentration of a 15 ml sample to 0.7 ml in just 20 min. Even though CYP molecular weight is often below nominal molecular weight limit (<50 kDa), to the best of our knowledge CYPs do not cross a YM-50 membrane.It is convenient to prepare the protein stock at higher concentration than required for crystallization setups. This expedient allows for dilution of test compound stocks with aqueous buffer prior to mixing with protein, as well as for dilution of impurities, including storage buffer ingredients, which may interfere with crystallization.

Measure protein concentration and aliquot concentrate into 50 µl aliquots. Set apart the amount of protein required for immediate screening of crystallization conditions and store the remainder at −80°C.

SUPPORT PROTOCOL 2

PREPARATION OF SELENOMETHIONINE PROTEIN DERIVATIVE

Multiwavelength Anomalous Dispersion (MAD) is the preferred method for phase determination in protein crystallography (Hendrickson et al., 1989). Substitution of methionine with selenomethionine is a general method for introducing anomalously scattering atoms into a cloned protein. The protocol for expression of CYP selenomethionine derivative in 5 L of bacterial culture is based on premixed reagents available from AthenaES (Baltimore, MD), which eliminates the tedious step of mixing together 19 amino acids when medium is prepared from scratch. The protocol exploits gradual adaptation of bacterial cells to the minimal medium and utilizes a non-auxotrophic E. coli strain to afford expression of CYP with selenium content sufficient for x-ray structure determination.

Additional materials

Athena Enzyme Systems™ SelenoMet™ Medium Base No 0501 (see recipe), 10× 1 L in 2.8-L standard Fernbach flasks

Athena Enzyme Systems™ SelenoMet™ Medium Base No 0501, 2 L

Athena Enzyme Systems™ SelenoMet™ Nutrient Mix No 0502 (see recipe)

Methionine, 10 mg/ml

Selenomethionine, 100 mg (Sigma-Aldrich, S3132)

Autoclaved water

250-ml culture flasks

Sterilized centrifuge containers

Day Culture

Transfer 10 ml of sterile LB medium into a sterile 50-ml tube.

Combine 10 µl of antibiotic and either 50 or 200 µl of transformed cells (see Support Protocol 1, Transformation steps 4 or 10) with the LB medium.

Close the lid on the tube enough to keep it from coming off, but leave it loose enough to allow for exchange of gases.

Incubate the 50-ml tube culture on a platform shaker for 8–10 hours at 240 rpm, 37°C.

Overnight Culture

Transfer 50 ml of SelenoMet™ Medium Base media into 5× 250-ml culture flasks.

To each 250-ml culture flask add 1 ml of the day culture, 50 µl of antibiotic, 200 µl of 10 mg/ml methionine and 2.5 ml of SelenoMet™ Nutrient mix.

- Incubate on a platform shaker overnight at 240 rpm, 37°C.In the morning, sample the overnight culture in each 250-ml culture flask to confirm OD590 of cells to be ≥ 2.0.

Transfer each 50 ml overnight culture into a sterile 50-ml tube.

Centrifuge 50-ml tubes for 7 min at 5000 rpm, 4°C.

Resuspend each cell pellet carefully using 2 ml of sterile SelenoMet™ Medium Base with a sterilized pipette.

Place resuspended cells on ice.

Expression Culture

Combine 1 ml of antibiotic, 50 ml SelenoMet™ Nutrient Mix, 4 ml of 10 mg/ml methionine, 250 µl Microelement Solution and one 50-ml tube of resuspended overnight culture cells with 1 L of sterilized SelenoMet™ Medium Base in the first set of five 2.8-L standard Fernbach flasks.

Incubate the expression cultures on a platform shaker until OD590 0.8–1.0 at 240 rpm, 37°C.

Centrifuge expression cultures for 7 min, at 5000 rpm, 4°C in 5 sterilized centrifuge containers.

Discard supernatant and place the 5 centrifuge containers with cell pellets on ice.

To remove excess of methionine, gently resuspend each pellet in 200 ml of ice-cold sterile SelenoMet™ Medium Base and spin down for 7 min at 5000 rpm, 4°C. Discard supernatant.

Transfer 50 ml of SelenoMet™ Medium Base from each of the remaining five flasks and gently resuspend each cell pellet.

Combine with the 950 ml SelenoMet™ Medium Base media in each of the remaining 5 flasks, 50 ml of SelenoMet™ Nutrient Mix, 250 µl Microelement Solution, 1 ml of antibiotic and the 50 ml of resuspended cells.

Incubate the expression cultures on a platform shaker for 1 h at 250 rpm, 37°C to minimize the amount of residual methionine.

-

Dissolve 100 mg of selenomethionine powder in 10 ml of room temperature autoclaved water.

The selenomethionine solution needs to be freshly prepared, so do not prepare too much in advance. Selenomethionine can be harmful if inhaled, swallowed or absorbed through the skin. Dissolve selenomethionine powder in a fumehood and wear gloves.

Induce expression in each flask with 0.5 ml of IPTG Additionally add 1 ml of 1 δ-aminolevulinic acid and 2 ml of 10 mg/ml selenomethionine.

-

Incubate the 5 1 L expression cultures on a platform shaker for 30 hours at 180 rpm, 25°C.

Incubation time may be dependent on the cell line used for expression.

Harvest

Centrifuge expression cultures for 15 min at 5000 rpm, 4°C in centrifuge containers.

Discard supernatant and place the centrifuge containers with cell pellets on ice.

Carefully resuspend cell pellets in an ice-cold Suspension Buffer supplemented with 1 mM DTT and combine together.

Transfer suspension to a 250-ml plastic container. Freeze and store at −80°C.

Purification

Purification is as described in Support Protocol 1 part II. Supplement all purification buffers with 1 mM DTT as selenomethionine is more susceptible to oxidation than methionine.

REAGENTS AND SOLUTIONS FOR SUPPORT PROTOCOLS

Expression vector

Expression vector (20–300 ng/µl) purified using Qiagen™ Plasmid Mini Kit according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer and stored at −20°C.

Expression Media

| Bacto™ tyrptone | 10 g |

| Bacto™ yeast extract | 5 g |

| 50% glycerol | 8 ml |

| 20× K-PO4 Solution (see recipe) | 50 ml |

Dissolve in 1 L of distilled water. Autoclave for 30 minutes. Store at room temperature.

20× K-PO4 Solution

| KH2PO4 | 46.2 g |

| K2HPO4 | 250.8 g |

Dissolve in 1 L of distilled water. The pH should be approximately 7.5. Filter solution through 0.4 micron filter and store at 4°C.

Microelement Solution

| FeCl3·6H2O | 2.7 g |

| ZnCl2·4H2O | 0.2 g |

| CoCl2·6H2O | 0.2 g |

| Na2MoO4·2H2O | 0.2 g |

| CaCl2·2H2O | 0.1 g |

| CuSO4·5H2O | 0.186 g |

| H3BO3 | 0.05 g |

Add 90 ml of distilled water and concentrated HCl until salts dissolve. Store indefinitely at room temperature.

Suspension Buffer

50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 1 mM EDTA, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.5 mM PMSF

| 50 mg/ml lysozyme | 200 µl |

| 2 M Tris, pH 8.0 | 5.0 ml |

| 0.5 M EDTA | 0.4 ml |

| 5 M NaCl | 4.0 ml |

| 0.2 M PMSF | 0.5 ml |

Make to 200 ml with distilled water. Prepare within 30 minutes of use and store on ice.

Ni-NTA Equilibration Buffer

50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 10% glycerol

| 1M Tris, pH 7.5 | 10 ml |

| 50% glycerol | 40 ml |

Make to 200 ml with distilled water.

Ni-NTA High-Salt Wash Buffer

50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 10% glycerol, 0.5 M NaCl, 0.5 mM PMSF

| 1 M Tris, pH 7.5 | 10 ml |

| 50% glycerol | 40 ml |

| 5 M NaCl | 20 ml |

| 0.2 M PMSF | 0.5 ml |

Make to 200 ml with distilled water. Prepare within 30 minutes of use.

Ni-NTA No-Salt Wash Buffer

20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 10% glycerol, 1 mM imidazole, 0.5 mM PMSF

| 1 M Tris, pH 7.5 | 4 ml |

| 50% glycerol | 40 ml |

| 4 M imidazole | 50 µl |

| 0.2 M PMSF | 0.5 ml |

Make to 200 ml with distilled water. Prepare within 30 minutes of use.

Ni-NTA Elution Buffer

20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 10% glycerol, 50 mM imidazole

| 1 M Tris, pH 7.5 | 2 ml |

| 50% glycerol | 20 ml |

| 4 M imidazole | 1.25 ml |

Make to 100 ml with distilled water.

S-Sepharose /Q-Sepharose Equilibration Buffer

20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 10% glycerol

| 1 M Tris, pH 7.5 | 8 ml |

| 50% glycerol | 80 ml |

Make to 400 ml with distilled water.

S-Sepharose/Q-Sepharose Wash Buffer

20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 0.5 mM EDTA

| 1 M Tris, pH 7.5 | 10 ml |

| 0.5 M EDTA | 0.5 ml |

Make to 500 ml with distilled water.

Q-Sepharose Elution Buffers

20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 0.5 mM EDTA, gradient of NaCl from 0 to 0.5 M

| 0 M | 0.5 M | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 M Tris, pH 7.5 | 5 ml | 5 ml |

| 0.5 M EDTA | 250 µl | 250 µl |

| 5 M NaCl | --- | 25 ml |

Make each solution to 250 ml with distilled water.

Athena Enzyme Systems™ SelenoMet™ Medium Base No 0501

| SelenoMet™ Medium Base | 21.6 g |

Dissolve in 1 L of distilled water. Autoclave for 30 minutes. Store at room temperature.

Athena Enzyme Systems™ SelenoMet™ Nutrient Mix No 0502

| SelenoMet™ Nutrient Mix | 5.1 g |

Dissolve in 50 ml of autoclaved distilled water. Do not autoclave or filter. Store at room temperature in sterile containers.

COMMENTARY

Background Information

HTS assay

The HTS assay is based on the optical spectral properties of CYP enzymes to elicit both type I and type II binding spectra (Schenkman et al., 1967). Type I changes (Figure 1A) indicate expulsion of the heme Fe axial water ligand from the Fe coordination sphere and the transition of the ferric heme Fe from the low-spin hexa-coordinated to the high-spin penta-coordinated state. Type II changes (Figure 1B) indicate replacement of a weak axial ligand, the water molecule, with one possessing a nitrogen-containing aliphatic or aromatic group. Type I binding is a prerequisite of the CYP catalytic activity, as the transition of the ferric heme Fe from the low-spin to the high-spin state precedes the transfer of the first electron derived from its redox partner. The vacant sixth coordination site of the ferrous heme Fe then readily binds molecular oxygen, followed by delivery of a second electron. Further protonation events result in dehydration of the iron-oxo species and formation of the ferryl-oxo compound I intermediate, an ultimate oxidant of substrate molecules.

Three major advantages of the assay are its simplicity, applicability to poorly characterized enzymes and universality, as it can be easily adapted for the analysis of any CYP which can be obtained in a soluble form. Two main drawbacks of the assay are the inherent low sensitivity of UV-vis absorption spectroscopy requiring the relatively high protein concentration (~1 µM) for screening, and the potential interference with the optical properties of test compounds. The commercially available CYP HTS assay (P450-Glo™) marketed by Promega (Cali et al., 2006), which is based on the enzymatic conversion of luminogenic substrates, offers the advantages of higher sensitivity and decreased interference with the optical properties of compounds. The presently available kit is configured for six unique probe substrates and its usage is limited to human liver CYP enzymes, accounting for most CYP-dependent drug metabolism. In contrast to human liver CYP proteins, microbial CYPs in most instances are barely well enough characterized to either design suitable luminogenic substrates or to pair them with efficient redox partner(s) to support the catalytic reaction. Given the large number of CYP open reading frames discovered in microbial genomes, including those of pathogenic microbes, development of individual enzyme-specific catalysis-based assays for most CYP targets seems not to be feasible at present.

Inhibition of M. tuberculosis growth in liquid medium

Microbial growth/inhibition can be measured in a number of ways, including plate counts (viable counts), direct microscopic counts, dry weight, turbidity measurement, absorbance and bioluminescence. In the Alamar blue assay, microbial inhibition is measured as a change in absorbance or fluorescence, resulting from reduction of its active blue component resazurin to pink resorufin, and then to colorless hydroresorufin, by the living cell (O'Brien et al., 2000; Rasmussen, 1999). The ease of the assay makes it an ideal choice for a quick, qualitative analysis of the inhibitory activity of compounds against M. tuberculosis, a slow growing organism (Yajko et al., 1995). This method is both more convenient and sensitive than conventional optical density measurements since it allows immediate distinction of live versus dead bacteria by visual color inspection. Minor differences in inhibitory activities, which are difficult to visualize, can be monitored by absorbance, 510 through 600 nm, or by fluorescence measurements taken at the excitation and emission wavelengths of 563 nm and 587 nm, respectively (Fai and Grant, 2009). Resazurin is very stable, non-toxic to both cells and users, water-soluble, does not precipitate upon reduction, and is easy to handle and dispose of.

Inhibition of M. tuberculosis growth in the macrophage cells

M. tuberculosis is an obligate intracellular pathogen that successfully evades microbicidal processes in lung macrophages and replicates in these cells to establish a persistent infection in humans (Saunders and Britton, 2007). Mouse is the most studied animal model of mycobacterial infections, providing valuable information on cellular and immune response to M. tuberculosis (Orme, 2003). Mouse macrophages are routinely used as infection models to evaluate the activity of compounds against intracellular mycobacteria. Primary bone-marrow derived macrophages respond to M. tuberculosis in a manner very similar to that of lung macrophages. The ease of obtaining bone-derived macrophages in large numbers makes them well suited for in vitro infection studies. Resting macrophages provide the ideal environment for mycobacteria in which to grow and replicate. Once phagocytosed, mycobacteria subvert the normal phago-lysosome fusion with the help of an array of molecules, both of bacterial and host origin (Pieters, 2008), and induce the release of immune modulatory cytokines (Flynn, 2004). Thus, infected macrophages provide a more sophisticated in vitro infection model, in which inhibitory compounds are modulated by cell membrane permeability and the complex cellular machineries invoked by the pathogen.

Co-crystallization of CYP target with screen hits

The pharmacological development potential of M. tuberculosis CYPs drives further exploration of their active site topologies using synthetic organic molecules in high throughput screening. Chemical scaffolds identified via screening may serve as leads for the development of potent inhibitors and/or molecular probes to address M. tuberculosis biology (Chen et al., 2009; Nasser Eddine et al., 2008; Podust et al., 2007). In conjunction with knowledge about compound inhibition potential, detailed structural characterization of the protein-inhibitor binding mode, revealed by x-ray crystallography, can guide lead optimization strategies to assist drug design.

Critical Parameters and Troubleshooting

HTS assay

There are several critical parameters for the screening of large libraries using UV-vis spectroscopic assays. First, when optimizing assay conditions for reference compound(s), determine the input of the target protein empirically by minimizing both protein concentration and reaction volume. Protein to be used must be fresh, so prepare only what is needed for the immediate task. Another critical parameter is the absorption characteristics of each individual compound, which must be determined by scanning the assay plates twice, before and after the addition of the target protein.

To optimize the assay conditions, the stability of protein and reference compound solution should be tested hourly at room temperature for up to 8 hours. The optimal incubation time can be determined by monitoring binding kinetics during the first hour.

Inhibition of M. tuberculosis growth in liquid medium

To ensure the success of the experiment, the mycobacterial culture should be in log phase growth. Reproducibility of the assay is affected by compound solubility. The assay is less reproducible for poorly soluble inhibitors. Fluorescence analysis, which is more sensitive, may improve reproducibility, as lower compound concentrations could be used to asses an inhibitory effect.

Inhibition of M. tuberculosis growth in the macrophage cells

Macrophage extraction and differentiation should be performed under absolutely sterile conditions, with minimum perturbation of cells to obtain a healthy and homogeneous population of macrophages. These precautions ensure the high efficiency of infection crucial for the success of the experiment.

Co-crystallization of CYP target with screen hits

Protein purity and conformational homogeneity are of paramount importance for crystallization. It is always beneficial to begin crystallization experiments with the best sample available. However, it would be a mistake to indefinitely postpone crystallization trials because of impurities present in the protein preparation, because electrophoretic purity is not the only factor dominating crystallization. No less important are conformational homogeneity and catalytic integrity of the sample. In the absence of a defined functional assay, the hallmark 450 nm peak in the difference absorption spectra, resulting from the Fe reduction with sodium dithionite in the presence of carbon monoxide, is taken as a measure of CYP functional integrity. Development of the P420 instead of the P450 form in most cases, with a few reported exceptions (Dunford et al., 2007; Ogura et al., 2004), is indicative of irreversible inactivation of the enzyme. Although integrity of the P450 form does not guarantee success of crystallization, to the best our knowledge, no P420 form has ever been crystallized. However, before making a final decision on sample quality, make sure that the CO-binding assay has been performed in a buffered solution at neutral pH and that the sodium dithionite has not been hydrolyzed.

The investigator may be misled by the apparent electrophoretic purity of protein eluted from the Ni-NTA column into omitting next two purification steps. No matter how pure the protein may look on the gel after Ni-NTA chromatography, the subsequent protocol steps will dramatically improve sample crystallization quality, eliminate impurities and, most important, increase the P450/P420 ratio. Therefore, to save time and avoid temptation, skip the SDS-PADE analysis after the Ni-NTA chromatography step and combine fractions based on the intensity of the red color.

If the CYP target has been previously successfully crystallized, the chance of obtaining co-crystals, at least with some screen hits, is fairly high. Individual screening and optimization of crystallization conditions is recommended for each target-inhibitor complex, as crystallization conditions for different complexes of the same protein can be quite divergent (Sherman et al., 2006). Once crystals are ready for data collection, expertise in protein crystallography is required for further progress. The quality of the diffraction data is of paramount importance for success of structure determination, whether by an experienced investigator or a novice (Holton, 2009).

Anticipated Results

HTS assay

It is to be expected that screening a library which may contain tens of thousands of compounds will yield a handful of high affinity ligands. The majority of binding hits fall either in the type I or type II category, indicating the binding mode. Although type II hits seem to be more abundant and on average of higher binding affinity, type I hits may provide valuable information on substrate specificity and the biological function of CYP enzymes.

Inhibition of M. tuberculosis growth in liquid medium

The inhibitory potential of multiple screen hits will be estimated in a 5-day procedure to single out the most potent compounds for further studies.

Inhibition of M. tuberculosis growth in the macrophage cells

Inhibition of M. tuberculosis growth in macrophage cells is a more sophisticated infection model to examine inhibitory potential of the compounds in vitro. In this model, the inhibitory effect of a compound depends not only on its binding affinity to the target, but also on its ability to cross the cell membrane, and on interactions with complex cellular processes which may eventually result in cytotoxicity. Activity displayed by the compound in the macrophage assay could be significantly different from to that in the Alamar blue assay, providing additional information on the compound’s bioavailability and toxicity.

Co-crystallization of CYP target with screen hits

It is likely that during the screening experiments crystallization conditions will be identified that need to be further optimized to obtain diffraction quality crystals of the target-inhibitor complex. Once diffraction data are collected from the co-crystal, the crystal structure of the complex can be readily determined by molecular replacement if coordinates of the protein of interest (or a related protein with ≥50% sequence identity) are available. If no a priori phase information is available, MAD data using crystals of the selenomethionine protein derivative may solve the phase problem for de novo structure determination. The ultimate result will be a set of atomic coordinates for the CYP-inhibitor complex deposited in the Protein Data Bank (PDB).

Time Consideration

HTS assay

Primary screening of 113 micro titer plates in a 384-well format (up to 40,000 compounds) takes about 5 days to complete, if one plate reader is used. It takes less than one minute to prepare one plate when using a pipetting robot to aliquot the test compounds. The two readings, in the presence and absence of target protein, which are required to account for the optical properties of the test compounds, are the major time constraint, as each scan takes approximately 10 minutes. Thus, it is beneficial to use two plate readers in parallel, which allows for complete primary screening in up to three days.

Analysis of screening data takes about two weeks using standard software, e.g., EXCEL, and visually inspecting absorption spectra. Specialized software for hit clustering by structural similarity, structure activity relations, or automated data documentation and analysis can further reduce analysis time to one week.

Validation of the primary hits for concentration dependence when binding to the CYP target requires an additional 5 days, including the optimization of the assay conditions for reference compounds.

If enzymatic or other functional assay(s) for the CYP of interest are available, test the screen hits for interference with the target function. The time will vary depending on the assay.

Inhibition of M. tuberculosis growth in liquid medium

The assay takes 5 days to complete once the log phase culture of M. tuberculosis is available.

Inhibition of M. tuberculosis growth in the macrophage cells

Differentiation of the macrophage cell takes 7 days. Performing the experiment takes 5 days. For colony analysis, it takes 21 days for mycobacterial colonies to grow on agar plates. Thus the whole experiment takes 5 weeks to complete.

Co-crystallization of CYP target with screen hits

Expression of native protein and the selenomethionine derivative takes 2 and 3 days, respectively. Protein purification protocol takes up to 3 days, including protein concentrating, which may allow enough time at the end of the third day for screening crystallization conditions using the fresh preparation.

Screening of crystallization conditions using the automated drop setting robot takes a few hours. Due to the small drop size, equilibrium between the drop and the well solution is established promptly and most of the crystals which can be formed will be formed within a few hours to 3 days. Nevertheless, incubate plates for up to a few months as some crystals may appear later.

Scaling and optimization of crystallization conditions is performed manually and requires direct involvement by the investigator both to formulate conditions and set up crystallization trays. With some practice, up to 10 trays can be set up in 1 day. Due to the larger volumes, equilibration in 24-well plates occurs more slowly and it may take days, or even weeks, for crystals to appear. However, during that time, visual inspection of crystallization drops is quickly accomplished, allowing for further optimization decisions.

As soon as satisfactory crystals are grown, allow 2–3 hs for crystal harvest and freezing. It may take some time to identify the best cryo-solution and to master the skills of manipulating small objects under the microscope and use cryo-tools in liquid nitrogen. All safety rules relevant to the work involving liquid nitrogen must be observed.

If diffraction data is to be collected at a synchrotron, data collection time normally should be arranged in advance, with all required formalities fulfilled before time is granted and scheduled. Synchrotron data collection per se takes from 10 minutes to a few hours, depending on the beam intensity, crystal parameters and data type. Collection of MAD data takes longer, as data at different wavelengths have to be collected. Knowledge in protein crystallography is required to collect a good quality data set. Time for determination of the crystal structure can vary widely, from a few days to never, depending strongly on data quality, method used and expertise of the investigator.

Acknowledgements

We thank Potter Wickware, Petrea Kells, and Hugues Ouellet for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH RO1 grant GM078553 (L.M.P.), the X-Mtb consortium (www.xmtb.org) Bundesministerium fuer Bildung und Forschung/Projekttraeger Juelich (BMBF/PTJ) grants BIO/0312992A (J.P.K.) and 0312992C (to TW).

Literature cited

- Ahmad Z, Sharma S, Khuller GK. In vitro and ex vivo antimycobacterial potential of azole drugs against Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2005;251:19–22. doi: 10.1016/j.femsle.2005.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad Z, Sharma S, Khuller GK. Azole antifungals as novel chemotherapeutic agents against murine tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2006a;261:181–186. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad Z, Sharma S, Khuller GK. The potential of azole antifungals against latent/persistent tuberculosis. FEMS Microbiology Letters. 2006b;258:200–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00224.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmad Z, Sharma S, Khuller GK, Singh P, Faujdar J, Katoch VM. Antimycobacterial activity of econazole against multidrug-resistant strains of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents. 2006c;28:543–544. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2006.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aoyama Y. Recent progress in the CYP51 research focusing on its unique evolutionary and functional characteristics as a diversozyme P450. Front. Biosci. 2005;10:1546–1557. doi: 10.2741/1639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banfi E, Scialino G, Zampieri D, Mamolo MG, Vio L, Ferrone M, Fermeglia M, Paneni MS, Pricl S. Antifungal and antimycobacterial activity of new imidazole and triazole derivatives. A combined experimental and computational approach. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2006;58:76–84. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkl182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrne ST, Denkin SM, Gu P, Nuermberger E, Zhang Y. Activity of ketoconazole against Mycobacterium tuberculosis in vitro and in the mouse model. J. Med. Microbiol. 2007;56:1047–1051. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.47058-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cali JJ, Ma D, Sobol M, Simpson DJ, Frackman S, Good TD, Daily WJ, Liu D. Luminogenic cytochrome P450 assays. Expert. Opin. Drug. Metab. Toxicol. 2006;2:629–645. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2.4.629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JC, Harik NS, Liao RP, Sherman DR. Identification of Mycobacterial genes that alter growth and pathology in macrophages and in mice. J. Infect. Dis. 2007;196:788–795. doi: 10.1086/520089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C-K, Doyle PS, Yermalitskaya LV, Mackey ZB, Ang KKH, McKerrow JH, Podust LM. Trypanosoma cruzi CYP51 inhibitor derived from a Mycobacterium tuberculosis screen hit. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2009;3:e372. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ST, Brosch R, Parkhill J, Garnier T, Churcher C, Harris D, Gordon SV, Eiglmeier K, Gas S, Barry CE, 3rd, Tekaia F, Badcock K, Basham D, Brown D, Chillingworth T, Connor R, Davies R, Devlin K, Feltwell T, Gentles S, Hamlin N, Holroyd S, Hornsby T, Jagels K, Krogh A, McLean J, Moule S, Murphy L, Oliver K, Osborne J, Quail MA, Rajandream MA, Rogers J, Rutter S, Seeger K, Skelton J, Squares R, Squares S, Sulston JE, Taylor K, Whitehead S, Barrell BG. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature. 1998;393:537–544. doi: 10.1038/31159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunford AJ, McLean KJ, Sabri M, Seward HE, Heyes DJ, Scrutton NS, Munro AW. Rapid P450 heme iron reduction by laser photoexcitation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis CYP121 and CYP51B1. Analysis of CO complexation reactions and reversibility of the P450/P420 equilibrium. J. Biol. Chem. 2007;282:24816–24824. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702958200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fai PB, Grant A. A rapid resazurin bioassay for assessing the toxicity of fungicides. Chemosphere. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2008.11.078. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn JL. Immunology of tuberculosis and implications in vaccine development. Tuberculosis. 2004;84:93–101. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2003.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendrickson WA, Horton JR, Murthy HM, Pahler A, Smith JL. Multiwavelength anomalous diffraction as a direct phasing vehicle in macromolecular crystallography. Basic Life Sci. 1989;51:317–324. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-8041-2_28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holton JM. A beginner's guide to radiation damage. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 2009;16 doi: 10.1107/S0909049509004361. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean KJ, Carroll P, Lewis DG, Dunford AJ, Seward HE, Neeli R, Cheesman MR, Marsollier L, Douglas P, Smith WE, Rosenkrands I, Cole ST, Leys D, Parish T, Munro AW. Characterization of active site structure in CYP121: A cytochrome P450 essential for viability of Mycobacterium tuberculosis H37Rv. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:33406–33416. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802115200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLean KJ, Cheesman MR, Rivers SL, Richmond A, Leys D, Chapman SK, Reid GA, Price NC, Kelly SM, Clarkson J, Smith WE, Munro AW. Expression, purification and spectroscopic characterization of the cytochrome P450 CYP121 from Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2002;91:527–541. doi: 10.1016/s0162-0134(02)00479-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nasser Eddine A, von Kries JP, Podust MV, Warrier T, Kaufmann SH, Podust LM. X-ray structure of 4,4'-dihydroxybenzophenone mimicking sterol substrate in the active site of sterol 14alpha-demethylase (CYP51) J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:15152–15159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M801145200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nwaka S, Hudson A. Innovative lead discovery strategies for tropical diseases. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2006;5:941–955. doi: 10.1038/nrd2144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Brien J, Wilson I, Orton T, Pognan F. Investigation of the Alamar Blue (resazurin) fluorescent dye for the assessment of mammalian cell cytotoxicity. Eur. J. Biochem. 2000;267:5421–5426. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2000.01606.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogura H, Nishida CR, Hoch UR, Perera R, Dawson JH, Ortiz de Montellano PR. EpoK, a cytochrome P450 involved in biosynthesis of the anticancer agents epothilones A and B. Substrate-mediated rescue of a P450 enzyme. Biochemistry. 2004;43:14712–14721. doi: 10.1021/bi048980d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orme IM. The mouse as a useful model of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis. 2003;83:112–115. doi: 10.1016/s1472-9792(02)00069-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz de Montellano PR. Cytochrome P450: Structure, Mechanism, and Biochemistry. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ouellet H, Podust LM, de Montellano PR. Mycobacterium tuberculosis CYP130: crystal structure, biophysical characterization, and interactions with antifungal azole drugs. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:5069–5080. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708734200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pieters J. Mycobacterium tuberculosis and the macrophage: maintaining a balance. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;3:399–407. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podust LM, von Kries JP, Nasser Eddine A, Kim Y, Yermalitskaya LV, Kuehne R, Ouellet H, Warrier T, Altekoster M, Lee J-S, Rademann J, Oschkinat H, Kaufmann SHE, Waterman MR. Small molecule scaffolds for CYP51 inhibitors identified by high-throughput screening and defined by x-ray crystallography. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2007;51:3915–3923. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00311-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Podust LM, Yermalitskaya LV, Lepesheva GI, Podust VN, Dalmasso EA, Waterman MR. Estriol bound and ligand-free structures of sterol 14α-demethylase. Structure. 2004;12:1937–1945. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen ES. Use of fluorescent redox indicators to evaluate cell prolifiration and viability. In Vitr. Mol. Toxicol. 1999;12:47–58. [Google Scholar]

- Recchi C, Sclavi B, Rauzier J, Gicquel B, Reyrat JM. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv1395 is a class III transcriptional regulator of the AraC family involved in cytochrome P450 regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:33763–33773. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305963200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sassetti CM, Rubin EJ. Genetic requirements for mycobacterial survival during infection. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A. 2003;100:12989–12994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2134250100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders BM, Britton WJ. Life and death in the granuloma: immunopathology of tuberculosis. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2007;85:103–111. doi: 10.1038/sj.icb.7100027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenkman JB, Remmer H, Estabrook RW. Spectral studies of drug interaction with hepatic microsomal cytochrome. Mol. Pharmacol. 1967;3:113–123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DJ, Hitchcoch CA, Sibley CM. Current and emerging azole antifungal agents. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 1999;12:40–79. doi: 10.1128/cmr.12.1.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherman DH, Li S, Yermalitskaya LV, Kim Y, Smith JA, Waterman MR, Podust LM. The structural basis for substrate anchoring, active site selectivity, and product formation by P450 PikC from Streptomyces venezuelae. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:26289–26297. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M605478200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yajko DM, Madej JJ, Lancaster MV, Sanders CA, Cawthon VL, Gee B, Babst A, Hadley WK. Colorimetric method for determining MICs of antimicrobial agents for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1995;33:2324–2327. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.9.2324-2327.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]