Abstract

The voltage gated proton channel bears surprising resemblance to the voltage-sensing domain (S1–S4) of other voltage gated ion channels, but is a dimer with two conduction pathways. The proton channel seems designed for efficient proton extrusion from cells. In phagocytes, it facilitates the production of reactive oxygen species by NADPH oxidase.

In 1972, Hewlett-Packard introduced the HP-35, the first scientific pocket calculator, which cost $395 and used reverse Polish notation, which resembles the German language in putting the verb (or operator) at the end of the sentence. Democratic National Headquarters at the Watergate Hotel in Washington D.C. was burglarized. Ceylon was renamed Sri Lanka. Also in 1972, Woody Hastings and colleagues proposed the existence of voltage gated proton channels in the dinoflagellate Noctiluca miliaris (70). One decade later, Roger Thomas and Bob Meech assailed a single snail neuron with a bewildering array of up to a half-dozen electrodes (to measure and control voltage, to measure current, pHi, pHo, and to inject HCl) resulting in the first voltage-clamp report of proton channels (211). Subsequent work, most notably the seminal study by Byerly, Meech, and Moody (22), confirmed that proton channels were genuine ion channels like the better known K+, Na+, and Ca2+ channels (23). Lydia Henderson, Brian Chappell, and Owen Jones provided strong indirect evidence that proton channels play a crucial role in compensating the electrogenic activity of NADPH oxidase in human neutrophils (84–86), which remains today their most clearly established specialized function. Voltage-clamp studies in the early 1990’s confirmed the existence of proton channels in mammalian (43) and human cells (13, 60, 49). During the remainder of this fin de siècle era, fundamental properties of proton channels were determined and the number of cells and species known to express proton channels grew to dozens (47). The discovery that proton channel gating was dramatically altered and enhanced in phagocytes during NADPH oxidase activity (9) combined with the application of the perforated-patch approach to study both proton and electron currents (the consequence of electrogenic NADPH oxidase activity) in living, responsive human neutrophils (56) advanced the understanding of the intricate interrelationship between proton channels and NADPH oxidase in phagocytes, one focus of this review. Genes coding for proton channels were discovered in 2006, ushering in a new era of unprecedented activity that is only just underway.

Properties of Voltage Gated Proton Channels

Proton channel gene

After a decade of controversy and turmoil over the proposal that the gp91phox component of NADPH oxidase was a voltage gated proton channel (8; 31, 45, 56, 55, 61, 76, 82, 83, 88, 87, 125, 127, 128, 139, 149, 161, 170, 188), genes coding for proton channels were finally identified in 2006 in human (173), mouse, and Ciona intestinalis (184). More recently, proton channel (Hvcn1) knockout (KO) mice have been shown to lack detectable proton current in neutrophils (65, 135, 168, 174), B lymphocytes (25), monocytes, and alveolar epithelial cells (unpublished observations with I.S. Ramsey, V.V. Cherny, B. Musset, D. Morgan, and D.E. Clapham). The suggestion that gp91phox might be a second type of proton channel that is active only when NADPH oxidase is assembled and active (9) was finally ruled out conclusively by studies of KO mouse neutrophils in perforated-patch configuration, in which the existence of PMA-stimulated electron current directly demonstrated the presence of active NADPH oxidase complexes in the plasma membranes of cells that lacked detectable proton current (65, 135).

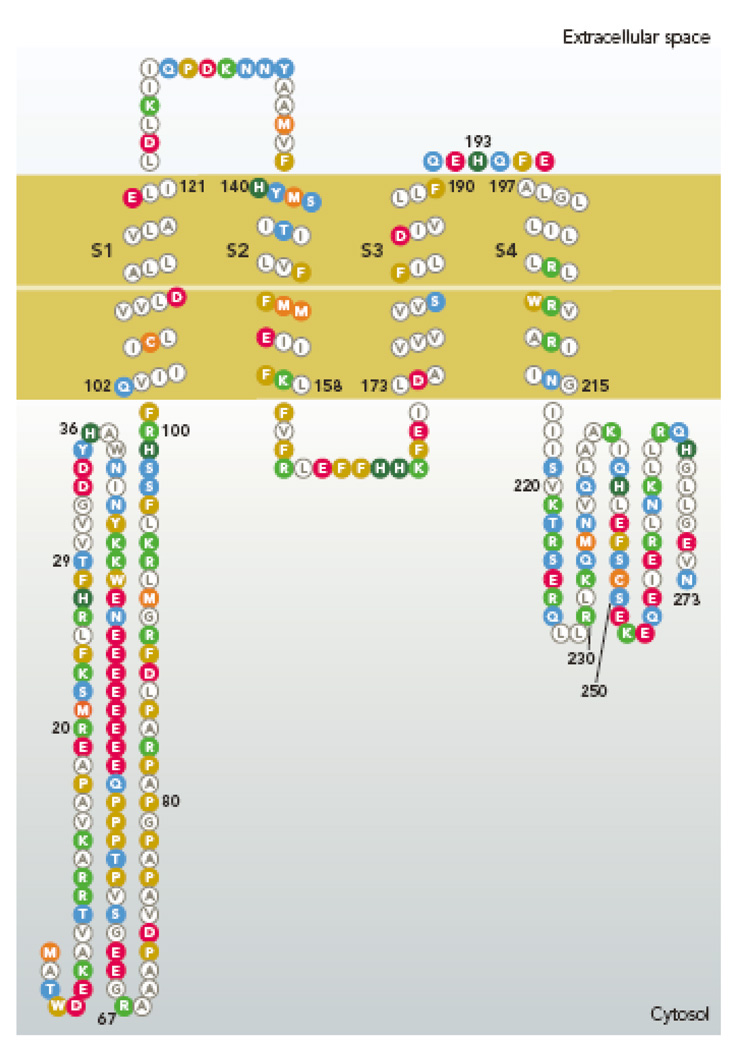

Thus far, only one proton channel gene has been identified in any species. The human Hvcn1 gene codes for 273 amino acids (Fig. 1), nominally a 32 kD protein. In Western blots of human B cell lines, the Hvcn1 gene product often appears as a doublet, which reflects the expression of both a full length and a shorter protein that results from a second initiation site downstream from the initial ATG (25; unpublished observations of M. Capasso and M.J.S. Dyer).

Figure 1.

Amino acid sequence of the human proton channel, HV1 (Hvcn1 gene product). The four membrane spanning regions resemble S1–S4 of K+ channels, including 3 of the 4 Arg residues in S4 that are thought to sense voltage (173). Membrane segments were determined by refined PHD prediction (179). [Image created with TOPO2 software from the Sequence Analysis & Consulting Service at UCSF, then redrawn.]

A naturally occurring missense mutation, M91T, has been identified that is estimated to occur in <1% of the human population (93). This mutation appears to shift the position of the proton conductance-voltage (gH-V) relationship positively, decreasing the likelihood of channel opening, and consequently reducing the H+ efflux elicited by high pHo in a heterologous expression system (93).

Molecular structure

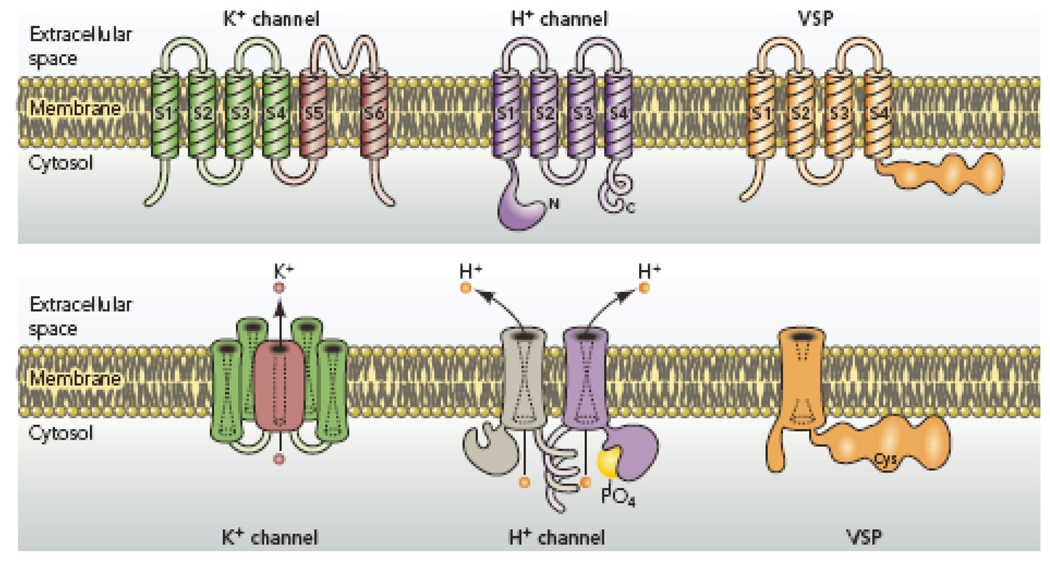

The proton channel gene products in human (178), mouse, and Ciona intestinalis (184) bear astonishing resemblance to the voltage-sensing domain of other voltage-gated ion channels (Fig. 2, top), even sharing 3 of the 4 Arg residues in the S4 domain thought to comprise the main voltage sensors in K+ channels (2, 193). It is nevertheless unclear whether these residues serve the same function of voltage sensing in the proton channel, because only one has been found to reduce voltage sensitivity upon mutation (173, 184). In addition, truncating the C terminus of the mouse channel, mVSOP, between the second and third Arg residues in S4 does not eliminate function (181).

Figure 2.

Comparison of architectural features of K+ channels, H+ channels, and voltage-sensing phosphatases (VSP). K+ channels are tetramers of subunits that each contain 6 membrane spanning regions, of which S1–S4 comprise the voltage sensing domain (VSD) and S5–S6 form the pore. The S5–S6 regions from each subunit together form a single central pore, which is surrounded by four VSDs. The voltage gated proton channel contains S1–S4 regions that are quite similar to the K+ channel VSD, but lacks the pore domain S5–S6 (173, 184). The proton channel is a dimer in which each monomer has its own conduction pathway (107, 116, 212). The main site of attachment is the C terminal coiled-coil domain (107, 116, 212). The N terminal intracellular region contains a phosphorylation site thought to convert the channel from “resting mode” to “enhanced gating mode” (56, 136, 152). The voltage sensing phosphatase shares similar S1–S4 regions with the others, but lacks conduction. Instead, it senses membrane potential and modulates phosphatase enzyme activity accordingly (147, 148).

The proton channel protein lacks the S5–S6 regions that form the pore of other channels. Evidently, a conduction pathway exists within the 273 amino acids that comprise S1–S4 in the human proton channel protein. This possibility seems entirely feasible, because the voltage sensing domains (VSD) of K+ channels can be converted into voltage-gated proton selective channels by single Arg-to-His mutations: R362H (203) or R371H (202, 204). All three classes of voltage sensing molecules in Fig. 2 appear to have several charged amino acid residues located in a narrow region within the membrane that has aqueous access on either end. The aqueous access regions serve to condense the membrane electrical field so that the charged resides can sense and respond to voltage without extensive physical translocation across the membrane (203). The aqueous access also provides a pathway for protons to cross most of the membrane; gating and selectivity may occur at the constriction, but neither function has been localized yet.

In 2008, three groups provided strong evidence that the proton channel exists as a dimer, with a conduction pathway in each monomer (107, 116, 212). It is not known whether the monomeric channels interact or gate independently, or what benefit might derive from this arrangement. Indirect evidence suggests a cooperative gating mechanism in which both monomers must undergo an opening transition before either can conduct (157).

Perfect Selectivity

A hallmark feature of voltage gated proton channels is their extreme selectivity. In fact, there is no evidence that any other ion can permeate; evidently, their selectivity is perfect. The reversal potential does not change (after correction for liquid junction potentials) on substitution of the predominant cation or anion with a wide range of ions. Observed deviations of the reversal potential from the Nernst potential for protons, EH, probably reflect imperfect control over pH. Even assuming they reflect permeation of other ions, the relative permeability calculated with the Goldman-Hodgkin-Katz equation (78, 89, 91) is still >106–108 greater for H+ than other cations (45). The identification of proton currents requires careful measurement of reversal potentials at different pH; other conductances may resemble proton currents, but are not. For example, many cells have Ca2+ activated Cl− currents that turn on slowly during depolarizing pulses (6, 81, 126).

The perfect selectivity of proton channels suggests that permeation may occur by a hydrogen bonded chain mechanism (HBC) including side chains of amino acids (50), as proposed originally by Nagle & Morowitz (159). Proton selectivity achieved by a titratable His residue in the permeation pathway was proposed for the M2 viral proton channel (144, 171, 189) and occurs for Arg→His mutants of the K+ channel VSD (202, 203). By comparison, protons permeate gramicidin channels by a Grotthuss-like mechanism, by hopping across a single file row of a dozen water molecules (118). Gramicidin channels have a higher conductance to H+ than to any other cation (normalized by permeant ion concentration), but they are not proton selective (90, 158). The high H+ conductance reflects the ability of protons to hop across the water wire without the necessity of water diffusing through the pore, in contrast to other cations that must wait in single file for the waters to permeate.

Proton conduction via water molecules that form a discontinuous water wire has been proposed to account for proton selectivity in some channels. Lear and colleagues (3, 115) observed proton selectivity of the synthetic channel (LSLLLSL)3 but nonselectivity of (LSSLLLSL)3 by virtue of the former being a tetramer too narrow to contain a continuous row of water molecules, and the latter being a water-filled pore. Similarly, some proposals regarding the high proton selectivity (permeability for H+ vs. other cations >1.5 × 106) of the M2 viral proton channel (37, 120, 122, 133, 143) include narrow constrictions that allow proton transfer between waters, but prevent free water flux (73, 183, 200, 205). Molecular dynamics calculations for constricted water wires in M2 (28) and in (LSLLLSL)3 (219) produced 6000-fold and 100-fold selectivity for H+ over other cations, thus falling short of reproducing the extreme selectivity reported experimentally. However, these models consider only the transmembrane domain and ignore entry and exit steps. Selectivity could be enhanced if protons preferentially approach the channel by rapid transfer in the plane of the membrane – the “antenna” effect” (1, 28, 79, 145).

It is at present unclear how selectivity is accomplished in the voltage gated proton channel. Two observations suggest that asparagine, Asn214, may play a role. Along with the three Arg residues in S4 of proton channels that align with the first three of four Arg in S4 of K+ channels, proton channels have a conserved Asn214 in the position of the fourth Arg. The point mutation N214R abolished proton current (212). By analogy with the movement of the four Arg in the K+ channel VSD during opening, Asn214 was predicted to move to the constriction of the proton channel during opening, providing a polar environment compatible with proton permeation (212). Supporting the plausibility of such a mechanism, a recent study of the water channel, aquaporin, showed that extreme proton selectivity could be achieved by the double mutation H180A/R195V in the putative selectivity filter region (220), which is distinct from the canonical NPA region in the center of the pore. The NPA (Asn-Pro-Ala) region selects against cation permeation (12), and was thought to exclude protons (20, 146, 207) because it coincides with the free energy barrier opposing proton permeation (26, 58, 92). However, even with NPA intact, the H180A/R195V mutant permits selective proton permeation, leading the authors to propose that at a constriction, Asn can act as a hydrogen bond donor compatible with H3O+ acting as an acceptor, while excluding other cations (220). The surprisingly high proton conductance through the NPA motif may reflect the unique advantage protons have over other cations, namely the capacity for charge delocalization (28). In light of the high proton selectivity of the H180A/R195V aquaporin mutant, which lacks any obvious titratable residues in the pathway, one might speculate that Asn214 may not only permit proton permeation, but act as the selectivity filter in the voltage gated proton channel. However, this attractive idea appears to be disproved by the persistence of proton selective permeation after C terminal truncation between the second and third Arg residues in S4 (181), ablating N214 altogether!

Permeation is Nontrivial

Permeation of protons through voltage gated proton channels almost certainly occurs by a Grotthuss-like mechanism of proton hopping, as opposed to hydrodynamic diffusion of hydronium ions, H3O+, or the flux of OH− in the opposite direction (45). The macroscopic, and more importantly, single-channel conductance increases with proton concentration on the side of the membrane from which current flows, but is unaffected by pH on the distal side of the membrane (34). The deuterium conductance is only about half that for protons (51), also strongly suggestive that H+ (not H3O+ or OH−) is the conducted species. In contrast, the deuterium isotope effect on proton conduction through gramicidin channels (4; 36) or on water permeation through aquaporin I channels (124) is not too different from corresponding values in bulk water. Finally, permeation has strong temperature dependence, with Q10 > 2 (23, 109) and as high as 5.1 in excised patches at <20°C, much higher than the Q10 for permeation of other ions through ordinary ion channels (52). By comparison, the temperature dependence of proton flux through water-filled gramicidin channels (4, 35) is closer to that for protons in bulk water. In summary, protons permeate the water-filled gramicidin channel with more facility than they traverse voltage gated proton channels.

Single channel proton currents are only a few femtoamperes even at low pH, just on the edge of being directly measurable under optimal conditions of low noise and tight seals in the TΩ range (34), which is critical for minimizing low frequency noise (117). However, proton channel gating introduces current fluctuations that can be used to determine the conductance. The unitary conductance is independent of pHo but decreases as pHi increases from 140 fS at pHi 5.5 to 38 fS at pHi 6.5 (34), and 15 fS extrapolated to physiological pHi 7.2 (at 21°C). Although this conductance is ~1000 times smaller than that of ordinary ion channels, the most probable explanation is that the permeant ion concentration is extremely low: cells contain >10−1 M K+ but <10−7 M H+, one million times lower. The largest recorded single channel current is that of protons through gramicidin, 350 pA (2 × 109 H+/s) at 5 M HCl (42), but if one extrapolates the unitary proton conductance of gramicidin to physiological pH, the result is actually smaller than for proton channels (45). Despite their miniscule unitary conductance, proton channels are expressed in most cells at sufficiently high levels that the macroscopic proton current is comparable to or larger than other currents, including K+ currents (23, 43, 60, 67, 138). Although this requires a proton channel density of up to 100–200 µm2 (45, 49), two orders of magnitude greater density has been observed for other membrane proteins (89).

Gating is regulated by voltage and pH

Proton currents look remarkably like delayed rectifier K+ currents, although their gating is generally slower. Both are activated by depolarization, activation becomes faster at more positive voltages, the currents turn on with a sigmoid time course whose sigmoidicity is increased by preceding hyperpolarization (the “Cole-Moore effect”) (41; 50), tail currents decay exponentially, with faster kinetics at more negative voltages. Effects of polyvalent cations and pH are qualitatively similar; extracellular metals and protons slow channel opening and shift the g–V relationship positively. However, proton channels distinguish themselves by the exquisite pH dependence of their gating. Increasing pHo or decreasing pHi shifts the gH-V relationship by 40 mV/unit pH toward more negative voltages (33; 51). This relationship can be expressed as:

| (eq. 1) |

where Vthreshold is the voltage at which proton current is first detectable, Vrev is the reversal potential, and Voffset is a constant. The slope factor, k, was 0.79 for a large series of native proton channels (meaning that Vthreshold changes somewhat less steeply than Vrev) and the offset was +23 mV (so that at symmetrical pH, Vthreshold is positive to Vrev). Eq. 1 holds over all physiological pH and appears to apply to all native proton currents (45). Thus, under physiological conditions, Vthreshold is positive to Vrev and the proton conductance activates only when outward proton flux will result. This elaborate regulation of gating seems designed to facilitate acid extrusion from cells.

The mechanism by which ΔpH regulates the voltage dependence of gating is not known, but presumably involves one or more titratable groups that can sample pH on both sides of the membrane, perhaps with alternating access, reminiscent of a carrier. The main features of pH- and voltage-dependent gating can be explained by a model that postulates a modulatory site that is accessible to only one side of the membrane at a time, its accessibility switches by a conformational change that can occur only when the site is deprotonated, and protonation from the inside promotes opening while protonation from the outside stabilizes the closed state (33).

For reasons that remain mysterious, both human (HV1) and mouse (mVSOP) proton channel gene products in heterologous expression systems (COS-7 or HEK-293 cells) exhibit altered voltage dependence compared with native proton channels. Expressed proton channels obey the same 40 mV/unit pH rule summarized in Eq. 1, with similar k, but Voffset is roughly −10 mV, so the entire gH-V relationship is shifted by roughly −30 mV compared with native proton currents. Consequently, at symmetrical pH (pHo = pHi), inward currents can be detected negative to EH (155), something never reported in (resting) native proton channels.

Inhibition by Zn2+

The most potent inhibitor of proton current is Zn2+ (123, 211); numerous other polyvalent cations are also effective. No high affinity peptide inhibitors exist, although hanatoxin (from tarantula spider venom) at micromolar concentrations shifts the gH-V relationship positively (5). A number of weak bases produce vague inhibition in the direction expected if the neutral form of the drug enters the cell and increases pHi near the membrane (45, 50, 53, 130). Antibodies to the channel protein have been developed, but thus far none that binds to the channel and inhibits conduction has been reported. The effects of Zn2+ resemble the effects of divalent cations on other voltage-gated ion channels (74): activation slows and the g–V relationship shifts toward more positive voltages. The effects of Zn2+ are greatly attenuated at lower pHo, suggesting competition between H+ and Zn2+ for binding site(s) on the channel (30). The data were described by assuming a Zn2+ binding site comprising 2–3 titratable groups with pKa ~6.5, suggesting His residues. When the human proton channel gene was identified, Ramsey et al (173) found that there were two externally accessible His residues, His140 and His193 (Fig. 1), both of which contribute to inhibition by Zn2+. Recently, it was proposed that Zn2+ may bind simultaneously to one His in each monomer, rather than to both His in each monomer (157).

Physiological Modulation of Proton Channel Function: The Enhanced Gating Mode

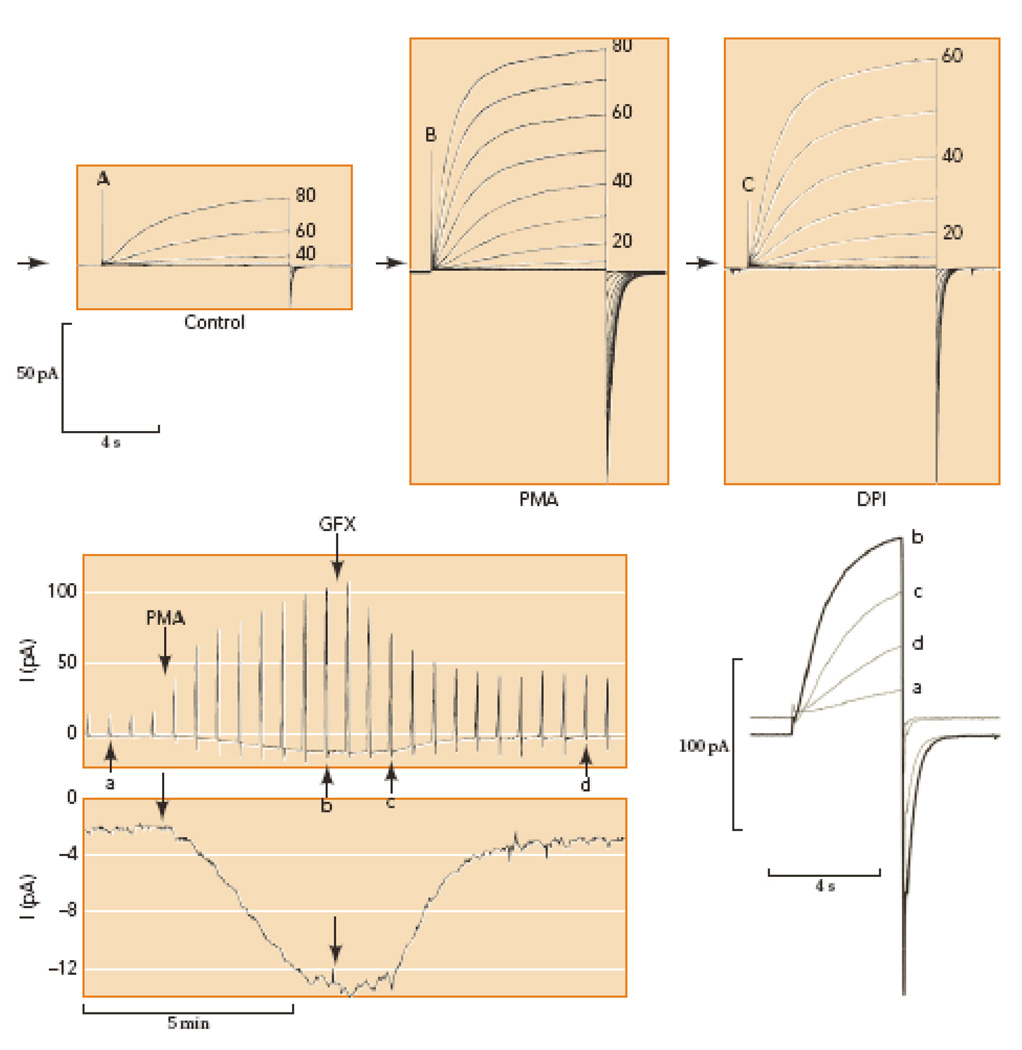

Proton channels are not sensitive to intracellular Ca2+ concentration (22, 53, 170, 186). In fact, very few agents affect proton currents studied in whole-cell configuration. However, in perforated-patch studies, a variety of stimuli produce a constellation of dramatic effects on proton channel gating, called the “enhanced gating mode.” Despite intriguing quantitative differences among cell types (154), the pattern is so stereotyped that it must reflect a common mechanism or pathway. Fig. 3A & 3B illustrate families of proton currents in a human eosinophil before and after stimulation by the phorbol ester PMA. The enhanced currents are larger, activate faster, deactivate more slowly, and the gH-V relationship is shifted negatively by 40 mV. This enhanced gating mode, first described in human eosinophils (9), occurs nearly identically in human neutrophils (56), monocytes (154), and PLB-985 cells (55), and in murine osteoclasts (141) and granulocytes (136). Enhanced gating with reduced features (a smaller shift of the gH-V relationship and little or no slowing of τtail) is seen in human basophils (156), neutrophils from human subjects with chronic granulomatous disease, and PLB-985 cells lacking gp91phox (55). Intriguingly then, a full response is seen in cells with robust NADPH oxidase activity, and a weaker response occurs in cells lacking this enzyme (154). Proton currents in some cells have little or no PMA response, including rat alveolar epithelial cells (56), and HEK-293 or COS-7 cells transfected with Hvcn1 (155).

Figure 3.

Conversion of proton channels in human eosinophils from resting mode (A) to enhanced gating mode (B) by PMA stimulation in perforated-patch configuration. Families of pulses were applied from a holding potential of −60 mV in 20-mV (A) or 10-mV steps (B–C) as indicated. Arrows indicate zero current; note the small inward electron current elicited by PMA (B). Inhibition of NADPH oxidase with diphenylene iodonium, DPI (C) eliminates the inward electron current, without immediate effect on the proton current. Lower panel shows the time course of the responses to PMA and GFX in a different eosinophil. Outward proton currents during pulses to +60 mV every 30 s are shown (above), with individual records identified by lower-case letters superimposed on the right at an expanded time scale. Net inward current at −60 mV at higher gain (below), reflects electron current through NADPH oxidase. PMA activates PKC and GFX inhibits PKC; thus, enhanced proton channel gating and NADPH oxidase are both regulated by phosphorylation. [Taken from 54 and 136, with permission.]

Strengthening the apparent connection between proton channels and NADPH oxidase, agonists that induce enhanced gating also activate NADPH oxidase. These include PMA, arachidonic acid, oleic acid, LTB4 (leukotriene B4), IL-5 (interleukin-5), and fMLF (a chemotactic peptide) (11, 32, 54–56, 136, 141). Some, but not all of the interactions between proton channels and NADPH oxidase (48; 154) may be explained by their common activation by phosphorylation. Fig. 3 (lower panel) illustrates the induction of enhanced proton channel gating after stimulation by the PKC activator, PMA, and the parallel activation of inward electron current that reflects the activity of NADPH oxidase. The PKC inhibitor GFX (GF109203X) reverses the effects on both molecules at least partially. Mutation of candidate phosphorylation sites in the intracellular N terminus of HV1 abolished PKC and GFX responses, suggesting that phosphorylation of the channel itself, and not an accessory molecule, produces enhanced gating (152).

Functions of Voltage Gated Proton Channels

Acid extrusion

In view of their exquisite regulation of gating by voltage and the pH gradient, ΔpH, the primary function of voltage gated proton channels has universally been considered to be acid extrusion. Intense metabolic activity produces intracellular acid, which promotes proton channel opening. Substantial evidence supports this function in a variety of cells. Recovery of pH by cells that are loaded with acid by HCl injection (211) or by the NH4+ prepulse approach (176) is slowed by inhibiting proton channels with Zn2+ in numerous cells (29, 59, 62, 110, 142, 150, 160, 164, 165, 194, 211). Depolarization by elevated [K+]o to activate proton channels produces rapid alkalinization of TsA201 cells transfected with the murine proton channel, but not in non-transfected cells (184). In cells that extrude metabolically-produced acid, proton channels may be activated by the lower pHi rather than by depolarization. This may be more evident in an alternative form of eq. 1:

| (eq. 2) |

in which, for alveolar epithelial cells, k = −40 mV and Voffset = 20 mV (33).

Zn2+ inhibits histamine-stimulated acid secretion by airway epithelial cells (69, 93, 188). Acid secretion in excised human sinonasal mucosa is inhibited 71% by Zn2+, implicating proton channels in this process (38). The Zn2+-sensitive fraction decreased to ~57% in chronic rhinosinusitis (38).

Specialized functions

Although acid extrusion is inevitable when proton channels are activated, other consequences of proton channel activity may be equally important in some situations. A contribution to cell volume regulation has been proposed in microglia (142) and chondrocytes (182). Facilitation of reactive oxygen species (ROS) production by DUOX1 in airways, analogous to that described below in phagocytes, has been suggested (68). Proton channels are highly expressed in human B lymphocytes (186) where they participate in B cell receptor mediated signaling cascades and antibody responses, most likely by enabling ROS production (18, 25). Possible facilitation of CO2 elimination by the lung has been hypothesized (44). A contribution to pH and membrane potential regulation in cardiac fibroblasts, especially during ischemia, has been proposed (64). Elimination of protons during action potentials has been suggested in snail neurons (130) and human skeletal muscle myotubes (13). Proton channel activity was demonstrated in localized pH microdomains in snail neurons during electrical activity (190).

Proton Channels Facilitate the Respiratory Burst in Phagocytes by Four Mechanisms

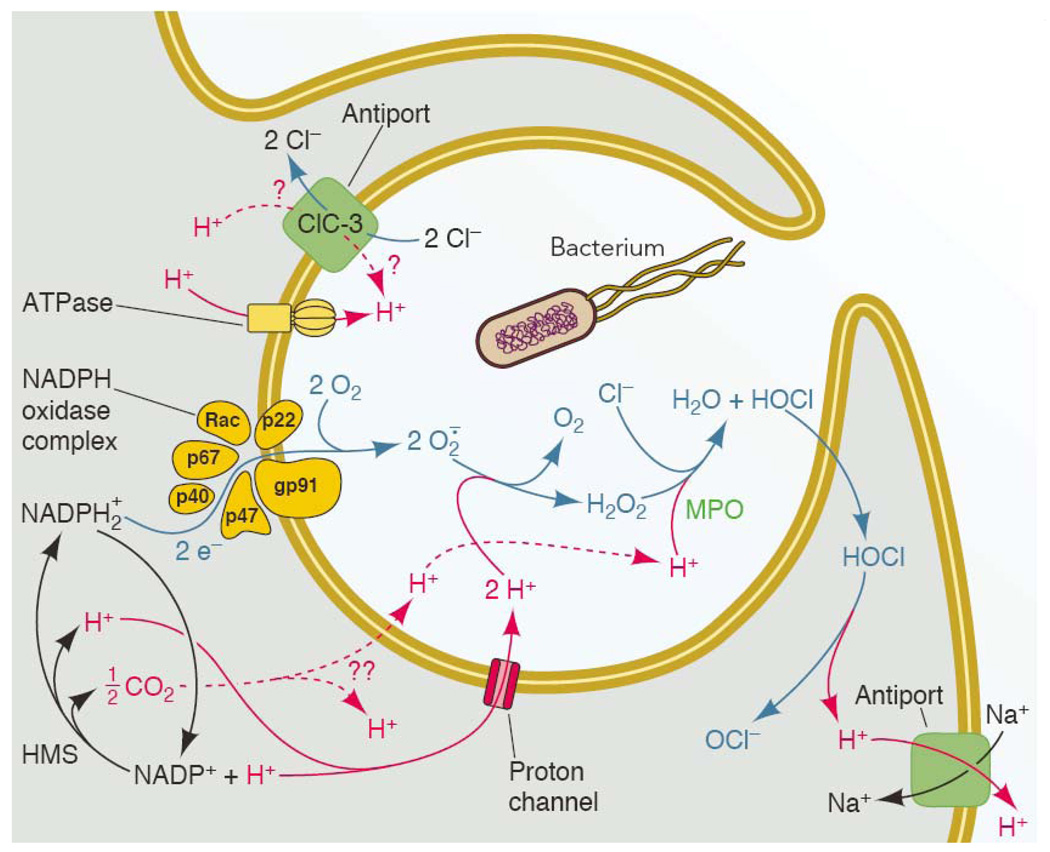

Charge compensation in phagocytes

The best established specialized function of proton channels is charge compensation in phagocytes (Fig. 4). Reactive oxygen species (ROS) produced by phagocytes contribute to microbial killing (7, 80, 99, 105, 106, 162, 177, 217). In other cells, ROS play a plethora of roles related to signaling, but may also contribute to chronic disease (114, 163). NADPH oxidase produces superoxide anion (O2.−), a precursor to numerous other ROS, and thus plays a central role in innate immunity. Of the several components that comprise the oxidase complex, gp91phox or Nox2 is the site of most of the action, containing an electron transport chain comprising NADPH in its binding site, FAD, and two heme groups that pass electrons sequentially to O2 at an external binding site where O2.− is produced. The enzyme is electrogenic, because the electrons extracted from cytoplasmic NADPH are translocated to extracellular or intraphagosomal O2 that is reduced to O2.− (84). In essence, the enzyme conducts electrical current in the form of electrons, just like a copper wire. Schrenzel et al (187) demonstrated electron current in eosinophils, directly confirming that NADPH oxidase is electrogenic.

Figure 4.

The main molecules and transporters thought to participate in charge compensation and pH regulation during the respiratory burst. A phagocyte is depicted engulfing a bacterium into a nascent phagosome, which will proceed to close and become intracellular. NADPH oxidase assembles preferentially in the phagosomal membrane in neutrophils (19, 167), and begins to function before the phagocytic cup has sealed (119). In eosinophils (111) macrophages (98), and neutrophils stimulated with soluble agonists (16), most NADPH oxidase assembles at the plasma membrane. Charge compensation is required wherever the enzyme is located. The entire system is driven by NADPH oxidase activity. Electrons from cytoplasmic NADPH are translocated across a redox chain to reduce O2 to superoxide anion, O2.−, inside the phagosome or extracellularly. The electrogenic activity can be measured directly as electron current (Fig. 3; 56, 187). For each electron removed from the cell, approximately one proton is left behind. Thus NADPH oxidase activity tends to depolarize the membrane, decrease pHi and increase pHo or pHphagosome. NADPH is regenerated continuously by the hexose monophosphate shunt (HMS) during the respiratory burst. Many of the transporters are functionally unidirectional. An exception is ClC-3 (Table 1), which is shown moving H+ into the phagosome and Cl− out, as is expected to occur at depolarized potentials that exist during the respiratory burst (113). In endosomes lacking Nox activity, ClC-3 is thought to operate in the reverse direction, removing H+ and injecting Cl− into the interior to compensate for electrogenic H+-ATPase activity (96). Although HOCl is membrane permeant (214), it reacts rapidly with cytoplasmic contents such as taurine (129) or glutathione (217); for present purposes, HOCl simply shuttles protons out of the phagosome (135). Note that the H+ in any compartment are equivalent; e.g., protons derived from HOCl dissociation are not preferentially removed by Na+/H+ antiport. [Expanded from ref. (151).]

The necessity for charge compensation can be appreciated by considering the magnitude of the task. The electron current is roughly −35 pA in human eosinophils at 37°C (138). Most NADPH oxidase assembles at the plasma membrane in eosinophils (111), whose job description may include killing helminthes and other parasites too large to engulf (178). The 35-pA electron current charges the 2.5 pF plasma membrane capacitance (187) at a rate of 14 Volts/s. In fact, it has been proposed to use NADPH oxidase to power biofuel cells in implantable devices (180). Without charge compensation, the membrane would depolarize to +200 mV in <20 ms, at which voltage NADPH oxidase ceases to function (57). This depolarization reflects efflux of ~4 × 106 electrons, which constitute just 0.01% of the ~4.6 × 1010 electrons extruded in a brief (5 min) respiratory burst stimulated by the chemotactic peptide fMetLeuPhe (221). Considering the extreme sensitivity of membrane potential to net charge separation, it is understandable that early studies generally concluded that depolarization preceded NADPH oxidase activity, and was, in fact, hypothesized to trigger the respiratory burst (24, 40, 100, 108, 192, 199, 216). The subsequent discovery that NADPH oxidase is electrogenic (84) made it clear that depolarization is a consequence of NADPH oxidase activity rather than its cause.

Protons are extruded from human neutrophils in 1:1 stoichiometry with O2 consumed during the respiratory burst (17, 75, 208, 213), indicating that proton efflux is responsible for the bulk of charge compensation (Fig. 4). Evidence that voltage gated proton channels mediate the bulk of the proton flux is extensive. Na+/H+ antiport is electroneutral (104, 196), and cannot compensate charge. Similarly, proton removal by CO2 diffusion is not electrogenic. Inhibiting the (electrogenic) H+-ATPase does not directly inhibit ROS production in neutrophils or macrophages (15, 59, 95, 206). Activation of NADPH oxidase produces a large depolarization, ~100 mV above the resting potential in human neutrophils (77, 94, 140, 172). The depolarization is exacerbated by Zn2+ (9, 10, 61, 84, 112, 172), indicating that a Zn2+-sensitive mechanism compensates charge.

If charge compensation is necessary and is performed by proton channels, then inhibiting proton current should inhibit NADPH oxidase activity. Metals that inhibit proton current potently, including Zn2+, Cd2+, and La3+, inhibit NADPH oxidase activity in neutrophils, eosinophils, monocytes, PLB-985 cells, macrophages, and microglia, from humans, mice, dogs, rats, and pigs, measured by cytochrome c reduction (superoxide anion production), Amplex Red assays (H2O2 generation), or by O2 consumption (11, 14, 39, 57, 67, 85, 86, 101, 121, 153, 166, 172, 174, 198, 201, 210, 222). The effects of Zn2+ cannot be ascribed to direct effects on NADPH oxidase, because there is no inhibition of enzyme activity in a cell-free system (222) or when electron currents are recorded under voltage clamp (57, 187). In both of these experimental situations, there is no need to compensate charge: membranes are permeabilized in the former, and the voltage-clamp amplifier provides compensation in the latter. These data show not only that proton channel activity occurs during the respiratory burst, they indicate that proton flux performs a function that is necessary for efficient ROS production, presumably charge compensation.

The creation of Hvcn1-deficient (proton channel knockout, KO) mice has enabled non-pharmacological approaches to this question. In leukocytes from KO mice NADPH oxidase activity is reduced by up to 75% (25, 65, 168, 174). This result indicates that the effects of Zn2+ in previous studies were mainly attributable to effects of proton channels, rather than some other Zn2+-sensitive molecule. That some activity remains in KO cells demonstrates that proton channels are not indispensible, although they are clearly the mechanism preferred by phagocytes. This result is not surprising, because COSphox cells (COS-7 cells transfected stably with the main NADPH oxidase components) have no proton currents, but produce detectable levels of superoxide anion (139). The impaired NADPH oxidase activity in KO cells suggests that proton channels contribute significantly and that the function they perform cannot readily be assumed by another molecule.

Despite the extensive evidence that proton flux through voltage gated proton channels provides the bulk of charge compensation in neutrophils, other transporters might facilitate charge compensation in different cells. Also proposed to contribute to charge compensation in leukocytes are the ClC-3 Cl−/H+ antiporter (113, 134, 191), CLIC-1 Cl− channels (132), TRPV1 nonselective cation channels (185), SK2 and SK4 Ca2+-activated K+ channels (103), and Kv1.3 delayed rectifier K+ channels (72). SK channels appear to facilitate mitochondrial (NADPH oxidase independent) ROS production in granulocytes (66), illustrating that partial reduction of ROS production by an inhibitor does not always reflect reduction of NADPH oxidase activity.

The magnitude of the NADPH oxidase (Nox2) activity in phagocytes, hence the enormous need for charge compensation, strongly implicates protons as the main charge carrier (see below). The numerous other cells that use ROS for signaling generally produce orders of magnitude lower levels than phagocytes, often by other Nox or Duox isoforms. In most of these cells the mechanism of charge compensation is unknown, although ROS production by B lymphocytes is defective in Hvcn1 KO mice (25). In fact, there exists no direct demonstration that other Nox isoforms are electrogenic, although this seems exceedingly likely. Because the evidence supporting a role of proton channels in compensating for the electrogenic activity of NADPH oxidase in neutrophils is compelling (45, 61, 63), there is a tendency to assume a similar role for proton channels in other cells with Nox activity. That other conductances can compensate charge to some extent is clear from the studies of COSphox cells (139) and Hvcn1 knockout mice (25, 65, 168, 174) discussed above. Ultimately it will be necessary to determine how charge is compensated in each cell.

Phagocytes produce enormous quantities of O2.− and ~95% of charge compensation is via proton channels (151). The cumulative concentration of electron equivalents (i.e., negative charges) in the phagosome (counting each O2.− produced as one electron) during a respiratory burst lasting a few minutes is 4 M (175). Despite O2.− being produced in the phagosome at a rate of 5–10 mM/s (80), neither electrons nor their initial product, O2.−, accumulate in phagosomes. The O2.− rapidly dismutates into H2O2 (Fig. 4) either spontaneously or catalyzed by myeloperoxidase (MPO) acting as a dismutase (102, 218). In turn, H2O2 is converted by MPO into HOCl, the active ingredient in household bleach. Most of the efforts of NADPH oxidase result in extensive HOCl production: 1/3 to 2/3 of the O2 consumed is converted into HOCl (27, 71, 75, 97, 209, 215). HOCl is highly reactive (105) and can oxidize bacterial components as well as other phagosome contents or it can be converted into other ROS. The pKa of HOCl is 7.5 and the neutral undissociated acid form can permeate the phagosome membrane and enter the cytoplasm, effectively shuttling protons out of the phagosome (Fig. 4). MPO inhibitors attenuate the acidification that occurs after phagocytosis, indicating that HOCl diffusion from phagosome into cytoplasm constitutes a significant acid load (135).

The converse of charge compensation is control of the membrane potential by proton channels. If other conductances are minimized, the resting membrane potential approaches the Nernst potential for protons, EH; for example, when NADPH oxidase is active in human eosinophils (9) or when pH is changed in cardiac fibroblasts (64). Even in physiological solutions, the strong depolarization produced by NADPH oxidase activity in human neutrophils or eosinophils (10, 61, 77, 84, 94, 135, 172), combined with a dearth of other voltage gated ion channels (46, 67), results in the membrane potential depolarizing to a level at which proton and electron currents are balanced (61, 84, 151, 172).

Cytoplasmic pH regulation during the respiratory burst

Although pH regulation is equivalent to acid extrusion, discussed above, special circumstances apply in the context of the phagocyte respiratory burst. NADPH oxidase activity in the phagosome membrane tends to lower cytoplasmic pH, but increase phagosomal pH. Matching proton flux stoichiometrically with electron flux would prevent pH changes in either compartment. Maintaining pH is important because NADPH oxidase has strong pHi dependence, with an optimum at pHi 7.0–7.5 (137). In the presence of Zn2+, pHi in phagocytosing human neutrophils decreases rapidly: to 6.5 after 2 min and 6.0 after 10 min (135), at which pHi NADPH oxidase activity is reduced by 50% or 80% respectively (137). In Hvcn1 KO mouse phagocytes, pHi drops during phagocytosis to the same level seen in WT cells in the presence of Zn2+ (135). These results indicate that without H+ efflux through proton channels, pHi would drop to levels that would impair NADPH oxidase activity drastically. This raises a semantic question. Is the main role of proton channels during the respiratory burst charge compensation or pH regulation? This question cannot be answered unambiguously, because H+ efflux performs both functions simultaneously.

Substrates for ROS production: The problem of Cl−

Phagocytes compensate charge with protons partly to supply the phagosome with the protons required for stoichiometric combination with O2.− to produce H2O2 (Fig. 4). Another proton is consumed in the conversion of H2O2 to HOCl, which as discussed above, is the predominant product of the respiratory burst.

In addition to protons, a key substrate for production of HOCl is Cl−, which would initially be present in the phagosome at its concentration in extracellular fluid (~0.1 M), and has been measured to be 73 mM (169). The problem is that ~1 M of HOCl is produced in the phagosome. Some Cl− may be introduced when granules and vesicles fuse with the phagosomal membrane. However, when the phagosome membrane depolarizes, as will tend to occur when NADPH oxidase begins to work, this will drive ClC-3, a Cl−/H+ antiporter that is expressed primarily in secretory vesicles and phagosome membranes in neutrophils (134), to compensate charge in the direction shown in Fig. 4, namely introducing one H+ into the phagosome and removing 2 Cl− per cycle. The result will be rapid loss of Cl−, which will terminate MPO activity by loss of substrate. Although some Cl− is regenerated when target molecules are oxidized by HOCl, chlorinated targets would deplete Cl− (218). Furthermore, diffusion of HOCl from the phagosome (Fig. 4) also removes Cl−. Confounding the problem of supply of Cl−, a number of studies indicate a massive efflux of cytoplasmic Cl−, which in resting neutrophils is present at the unusually high concentration of 80 mM (197), into the extracellular medium (21, 131, 195). When extracellular Cl− is removed, the phagosomal Cl− concentration drops from 76 mM to 6 mM within 15 min (169), strongly suggesting that loss of Cl− from the cytoplasm would exacerbate the depletion of Cl− from the phagosome.

Preventing osmotically induced swelling of the phagosome

Because of the magnitude of the charge compensation problem in neutrophil phagosomes, the choice of ion to compensate charge is critical. For example, if charge were compensated by K+ flux into the phagosome, the resulting 4 M K+ would swell the phagosome to ~25 times its original volume, which does not occur (175). In contrast, when H+ compensates charge, the products are mostly membrane permeant (H2O, H2O2, and HOCl), consequently reducing their deleterious osmotic effects. When phagosomal Cl− is depleted, which likely occurs rapidly due to the confusticatingly positioned ClC-3, the multitalented MPO can act as an oxidoreductase (218):

or a catalase (218):

In both cases, O2.− and H+ eventually combine to form O2 and H2O, which are relatively inert both osmotically and physiologically. Depletion of Cl− from the phagosome by ClC-3 activity may serve to terminate the more toxic aspects of the respiratory burst, perhaps limiting the damage done to the neutrophil or to surrounding tissues.

Summary

The proton channel molecule shares many similarities with the VSD of other voltage-gated channels. Unlike most channels, the proton channel is a dimer with twin conduction pathways. Although steeply voltage dependent, the gating of proton channels depends strongly on the pH gradient, with the result that it almost invariably extrudes acid when it opens. Proton channels are uniquely suited to their job in phagocytes, where they optimize NADPH oxidase activity by simultaneously compensating charge, minimizing pH changes both in cytoplasm and phagosome, minimizing osmotic imbalance, and providing substrate protons for ROS production in the phagosome.

Table 1. Effects of Transporters on pHi and pHphagosome at Different Voltages.

Expected effects of several membrane transporters or processes on pH in the cytoplasm (pHi) or phagosome (pHphagosome) of a neutrophil. Number of arrows reflects both rate and extent of effects. For example, ClC-3 and Na+/H+ antiport in the phagosome will cease as soon as phagosomal Cl− or Na+, respectively, is exhausted. ClC-3 is unique in that it is expected to change pH in opposite directions at different voltages.

| Hyperpolarized | Depolarized | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transporter | pHi | pHphagosome | pHi | pHphagosome |

| NADPH oxidase | ↓↓↓ | ↑↑↑ | ↓↓ | ↑↑ |

| Proton channel | - | - | ↑↑↑ | ↓↓↓ |

| H+-ATPase | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓↓ |

| Na+/H+ antiport | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ |

| ClC-3 | ↓ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓↓ |

| HOCl diffusion | ↓ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑ |

| CO2 | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ | ↓ |

Acknowledgements

I appreciate discussions with Fred S. Lamb, Ricardo Murphy, William M. Nauseef, Régis Pomès, Susan M.E. Smith, Greg A. Voth, and Christine Winterbourn and previews of unpublished data by Melania Capasso, Martin J.S. Dyer, Horst Fischer, and Nicolas Demaurex. This work was supported in part by NIH Heart Lung and Blood Institute grant HL-61437 and by the National Science Foundation.

References

- 1.Ädelroth P, Brzezinski P. Surface-mediated proton-transfer reactions in membrane-bound proteins. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1655:102–115. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2003.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aggarwal SK, MacKinnon R. Contribution of the S4 segment to gating charge in the Shaker K+ channel. Neuron. 1996;16:1169–1177. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80143-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Åkerfeldt KS, Lear JD, Wasserman ZR, Chung LA, DeGrado WF. Synthetic peptides as models for ion channel proteins. Acc Chem Res. 1993;26:191–197. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akeson M, Deamer DW. Proton conductance by the gramicidin water wire: model for proton conductance in the F1F0 ATPases? Biophys J. 1991;60:101–109. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82034-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alabi ARA, Bahamonde MI, Jung HJ, Kim JI, Swartz KJ. Portability of paddle motif function and pharmacology in voltage sensors. Nature. 2007;450:370–375. doi: 10.1038/nature06266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arreola J, Melvin JE, Begenisich T. Inhibition of Ca2+-dependent Cl− channels from secretory epithelial cells by low internal pH. J Membr Biol. 1995;147:95–104. doi: 10.1007/BF00235400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babior BM, Kipnes RS, Curnutte JT. Biological defense mechanisms. The production by leukocytes of superoxide, a potential bactericidal agent. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:741–744. doi: 10.1172/JCI107236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bánfi B, Maturana A, Jaconi S, Arnaudeau S, Laforge T, Sinha B, Ligeti E, Demaurex N, Krause KH. A mammalian H+ channel generated through alternative splicing of the NADPH oxidase homolog NOH-1. Science. 2000;287:138–142. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5450.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bánfi B, Schrenzel J, Nüsse O, Lew DP, Ligeti E, Krause KH, Demaurex N. A novel H+ conductance in eosinophils: unique characteristics and absence in chronic granulomatous disease. J Exp Med. 1999;190:183–194. doi: 10.1084/jem.190.2.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bankers-Fulbright JL, Gleich GJ, Kephart GM, Kita H, O'Grady SM. Regulation of eosinophil membrane depolarization during NADPH oxidase activation. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:3221–3226. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bankers-Fulbright JL, Kita H, Gleich GJ, O'Grady SM. Regulation of human eosinophil NADPH oxidase activity: a central role for PKCδ. J Cell Physiol. 2001;189:306–315. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Beitz E, Wu B, Holm LM, Schultz JE, Zeuthen T. Point mutations in the aromatic/arginine region in aquaporin 1 allow passage of urea, glycerol, ammonia, and protons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:269–274. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507225103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bernheim L, Krause RM, Baroffio A, Hamann M, Kaelin A, Bader CR. A voltage-dependent proton current in cultured human skeletal muscle myotubes. J Physiol. 1993;470:313–333. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beswick PH, Brannen PC, Hurles SS. The effects of smoking and zinc on the oxidative reactions of human neutrophils. J Clin Lab Immunol. 1986;21:71–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bidani A, Heming TA. Effects of bafilomycin A1 on functional capabilities of LPS-activated alveolar macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 1995;57:275–281. doi: 10.1002/jlb.57.2.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Borregaard N, Heiple JM, Simons ER, Clark RA. Subcellular localization of the b-cytochrome component of the human neutrophil microbicidal oxidase: translocation during activation. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:52–61. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borregaard N, Schwartz JH, Tauber AI. Proton secretion by stimulated neutrophils: significance of hexose monophosphate shunt activity as source of electrons and protons for the respiratory burst. J Clin Invest. 1984;74:455–459. doi: 10.1172/JCI111442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Boyd RS, Jukes-Jones R, Walewska R, Brown D, Dyer MJS, Cain K. Protein profiling of plasma membranes defines aberrant signaling pathways in mantle cell lymphoma. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2009;8:1501–1515. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800515-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Briggs RT, Drath DB, Karnovsky ML, Karnovsky MJ. Localization of NADH oxidase on the surface of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes by a new cytochemical method. J Cell Biol. 1975;67:566–586. doi: 10.1083/jcb.67.3.566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Burykin A, Warshel A. What really prevents proton transport through aquaporin? Charge self-energy versus proton wire proposals. Biophys J. 2003;85:3696–3706. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74786-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Busetto S, Trevisan E, Decleva E, Dri P, Menegazzi R. Chloride movements in human neutrophils during phagocytosis: characterization and relationship to granule release. J Immunol. 2007;179:4110–4124. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Byerly L, Meech R, Moody W., Jr Rapidly activating hydrogen ion currents in perfused neurones of the snail, Lymnaea stagnalis. J Physiol. 1984;351:199–216. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Byerly L, Suen Y. Characterization of proton currents in neurones of the snail, Lymnaea stagnalis. J Physiol. 1989;413:75–89. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1989.sp017642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cameron AR, Nelson J, Forman HJ. Depolarization and increased conductance precede superoxide release by concanavalin A-stimulated rat alveolar macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:3726–3728. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.12.3726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Capasso M, Bhamrah MK, Henley T, Boyd RS, Langlais C, Cain K, Dinsdale D, Pulford K, Kan M, Musset B, Cherny VV, Morgan D, Gascoyne RD, Vigorito E, DeCoursey TE, MacLennan ICM, Dyer MJS. Control of B cell activation by the voltage-gated proton channel, HVCN1. Nature Immunol. 2010 Conditionally accepted. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chakrabarti N, Tajkhorshid E, Roux B, Pomès R. Molecular basis of proton blockage in aquaporins. Structure. 2004;12:65–74. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chapman ALP, Hampton MB, Senthilmohan R, Winterbourn CC, Kettle AJ. Chlorination of bacterial and neutrophil proteins during phagocytosis and killing of Staphylococcus aureus. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:9757–9762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M106134200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen H, Wu Y, Voth GA. Proton transport behavior through the influenza A M2 channel: insights from molecular simulation. Biophys J. 2007;93:3470–3479. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.105742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cheng YM, Kelly T, Church J. Potential contribution of a voltage-activated proton conductance to acid extrusion from rat hippocampal neurons. Neurosci. 2008;151:1084–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cherny VV, DeCoursey TE. pH-dependent inhibition of voltage-gated H+ currents in rat alveolar epithelial cells by Zn2+ and other divalent cations. J Gen Physiol. 1999;114:819–838. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.6.819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cherny VV, Henderson LM, DeCoursey TE. Proton and chloride currents in Chinese hamster ovary cells. Membr Cell Biol. 1997;11:337–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cherny VV, Henderson LM, Xu W, Thomas LL, DeCoursey TE. Activation of NADPH oxidase-related proton and electron currents in human eosinophils by arachidonic acid. J Physiol. 2001;535:783–794. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00783.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cherny VV, Markin VS, DeCoursey TE. The voltage-activated hydrogen ion conductance in rat alveolar epithelial cells is determined by the pH gradient. J Gen Physiol. 1995;105:861–896. doi: 10.1085/jgp.105.6.861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cherny VV, Murphy R, Sokolov V, Levis RA, DeCoursey TE. Properties of single voltage-gated proton channels in human eosinophils estimated by noise analysis and direct measurement. J Gen Physiol. 2003;121:615–628. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200308813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chernyshev A, Cukierman S. Thermodynamic view of activation energies of proton transfer in various gramicidin A channels. Biophys J. 2002;82:182–192. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75385-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chernyshev A, Pomès R, Cukierman S. Kinetic isotope effects of proton transfer in gramicidin channels in aqueous and methanol containing solutions. Biophys Chem. 2003;103:179–190. doi: 10.1016/s0301-4622(02)00255-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chizhmakov IV, Geraghty FM, Ogden DC, Hayhurst A, Antoniou M, Hay AJ. Selective proton permeability and pH regulation of the influenza virus M2 channel expressed in mouse erythroleukemia cells. J Physiol. 1996;494:329–336. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1996.sp021495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cho DY, Hajighasemi M, Hwang PH, Illek B, Fischer H. Proton secretion in freshly excised sinonasal mucosa from asthma and sinusitis patients. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2009;23:10–13. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2009.23.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chvapil M, Stankova L, Bernhard DS, Weldy PL, Carlson EC, Campbell JB. Effect of zinc on peritoneal macrophages in vitro. Infect Immun. 1977;16:367–373. doi: 10.1128/iai.16.1.367-373.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cohen HJ, Newburger PE, Chovaniec ME, Whitin JC, Simons ER. Opsonized zymosan-stimulated granulocytes-activation and activity of the superoxide-generating system and membrane potential changes. Blood. 1981;58:975–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cole KS, Moore JW. Potassium ion current in the squid giant axon: dynamic characteristic. Biophys J. 1960;1:1–14. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(60)86871-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cukierman S. Proton mobilities in water and in different stereoisomers of covalently linked gramicidin A channels. Biophys J. 2000;78:1825–1834. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76732-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.DeCoursey TE. Hydrogen ion currents in rat alveolar epithelial cells. Biophys J. 1991;60:1243–1253. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(91)82158-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.DeCoursey TE. Hypothesis: do voltage-gated H+ channels in alveolar epithelial cells contribute to CO2 elimination by the lung? Am J Physiol: Cell Physiol. 2000;278:C1–C10. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2000.278.1.C1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.DeCoursey TE. Voltage-gated proton channels and other proton transfer pathways. Physiol Rev. 2003;83:475–579. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00028.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.DeCoursey TE. Electrophysiology of the phagocyte respiratory burst. Focus on "Large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel activity is absent in human and mouse neutrophils and is not required for innate immunity.". Am J Physiol: Cell Physiol. 2007;293:C30–C32. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00093.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.DeCoursey TE. Voltage-gated proton channels. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2008;65:2554–2573. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8056-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeCoursey TE. Voltage-gated proton channels: What’s next? J Physiol. 2008;586:5305–5324. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.161703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DeCoursey TE, Cherny VV. Potential, pH, and arachidonate gate hydrogen ion currents in human neutrophils. Biophys J. 1993;65:1590–1598. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81198-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DeCoursey TE, Cherny VV. Voltage-activated hydrogen ion currents. J Membr Biol. 1994;141:203–223. doi: 10.1007/BF00235130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.DeCoursey TE, Cherny VV. Deuterium isotope effects on permeation and gating of proton channels in rat alveolar epithelium. J Gen Physiol. 1997;109:415–434. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.4.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.DeCoursey TE, Cherny VV. Temperature dependence of voltage-gated H+ currents in human neutrophils, rat alveolar epithelial cells, and mammalian phagocytes. J Gen Physiol. 1998;112:503–522. doi: 10.1085/jgp.112.4.503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DeCoursey TE, Cherny VV. Pharmacology of voltage-gated proton channels. Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13:2406–2420. doi: 10.2174/138161207781368675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.DeCoursey TE, Cherny VV, DeCoursey AG, Xu W, Thomas LL. Interactions between NADPH oxidase-related proton and electron currents in human eosinophils. J Physiol. 2001;535:767–781. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00767.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.DeCoursey TE, Cherny VV, Morgan D, Katz BZ, Dinauer MC. The gp91phox component of NADPH oxidase is not the voltage-gated proton channel in phagocytes, but it helps. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:36063–36066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100352200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.DeCoursey TE, Cherny VV, Zhou W, Thomas LL. Simultaneous activation of NADPH oxidase-related proton and electron currents in human neutrophils. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:6885–6889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100047297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.DeCoursey TE, Morgan D, Cherny VV. The voltage dependence of NADPH oxidase reveals why phagocytes need proton channels. Nature. 2003;422:531–534. doi: 10.1038/nature01523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.de Groot BL, Engel A, Grubmüller H. The structure of the aquaporin-1 water channel: a comparison between cryo-electron microscopy and X-ray crystallography. J Mol Biol. 2003;325:485–493. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01233-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Demaurex N, Downey GP, Waddell TK, Grinstein S. Intracellular pH regulation during spreading of human neutrophils. J Cell Biol. 1996;133:1391–1402. doi: 10.1083/jcb.133.6.1391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Demaurex N, Grinstein S, Jaconi M, Schlegel W, Lew DP, Krause KH. Proton currents in human granulocytes: regulation by membrane potential and intracellular pH. J Physiol. 1993;466:329–344. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Demaurex N, Petheõ GL. Electron and proton transport by NADPH oxidases. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:2315–2325. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2005.1769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Diarra A, Sheldon C, Brett CL, Baimbridge KG, Church J. Anoxia-evoked intracellular pH and Ca2+ concentration changes in cultured postnatal rat hippocampal neurons. Neuroscience. 1999;93:1003–1016. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00230-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Eder C, DeCoursey TE. Voltage-gated proton channels in microglia. Prog Neurobiol. 2001;64:277–305. doi: 10.1016/s0301-0082(00)00062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.El Chemaly A, Guinamard R, Demion M, Fares N, Jebara V, Faivre F, Bois P. A voltage-activated proton current in human cardiac fibroblasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:512–516. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.El Chemaly A, Okochi Y, Arnaudeau S, Okamura Y, Demaurex N. Ablation of the Hv1 proton channel blunts store-operated Ca2+ influx in neutrophils. Eur J Clin Invest. 2009;39:28–29. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fay AJ, Qian X, Jan YN, Jan LY. SK channels mediate NADPH oxidase-independent reactive oxygen species production and apoptosis in granulocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:17548–17553. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607914103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Femling JK, Cherny VV, Morgan D, Rada B, Davis AP, Czirják G, Enyedi P, England SK, Moreland JG, Ligeti E, Nauseef WM, DeCoursey TE. The antibacterial activity of human neutrophils and eosinophils requires proton channels but not BK channels. J Gen Physiol. 2006;127:659–672. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Fischer H. Airway surface liquid pH and innate defense by the NADPH oxidase. Ped Pulmonol suppl. 2007;30:175–177. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Fischer H, Widdicombe JH, Illek B. Acid secretion and proton conductance in human airway epithelium. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2002;282:736–743. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00369.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fogel M, Hastings JW. Bioluminescence: mechanism and mode of control of scintillon activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1972;69:690–693. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.3.690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Foote CS, Goyne TE, Lehrer RI. Assessment of chlorination by human neutrophils. Nature. 1983;301:715–716. doi: 10.1038/301715a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fordyce CB, Jagasia R, Zhu X, Schlichter LC. Microglia Kv1.3 channels contribute to their ability to kill neurons. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7139–7149. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1251-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Forrest LR, Kukol A, Arkin IT, Tieleman DP, Sansom MSP. Exploring models of the influenza A M2 channel: MD simulations in a phospholipid bilayer. Biophys J. 2000;78:55–69. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(00)76572-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Frankenhaeuser B, Hodgkin AL. The action of calcium on the electrical properties of squid axons. J Physiol. 1957;137:218–244. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1957.sp005808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Gabig TG, Lefker BA, Ossanna PJ, Weiss SJ. Proton stoichiometry associated with human neutrophil respiratory-burst reactions. J Biol Chem. 1984;259:13166–13171. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Gaggioli V, Schwarzer C, Fischer H. Expression of Nox1 in 3T3 cells increases cellular acid production but not proton conductance. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;459:189–196. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Geiszt M, Kapus A, Nemet K, Farkas L, Ligeti E. Regulation of capacitative Ca2+ influx in human neutrophil granulocytes. Alterations in chronic granulomatous disease. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:26471–26478. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.42.26471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Goldman DE. Potential, impedance, and rectification in membranes. J Gen Physiol. 1943;27:37–60. doi: 10.1085/jgp.27.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Gutman M, Nachliel E, Friedman R. The mechanism of proton transfer between adjacent sites on the molecular surface. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:931–941. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hampton MB, Kettle AJ, Winterbourn CC. Inside the neutrophil phagosome: oxidants, myeloperoxidase, and bacterial killing. Blood. 1998;92:3007–3017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hartzell HC, Yu K, Xiao Q, Chien LT, Qu Z. Anoctamin/TMEM16 family members are Ca2+-activated Cl− channels. J Physiol. 2009;587:2127–2139. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.163709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Henderson LM. Role of histidines identified by mutagenesis in the NADPH oxidase-associated H+ channel. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33216–33223. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.50.33216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Henderson LM, Banting G, Chappell JB. The arachidonate-activable, NADPH oxidase-associated H+ channel. Evidence that gp91-phox functions as an essential part of the channel. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:5909–5916. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Henderson LM, Chappell JB, Jones OTG. The superoxide-generating NADPH oxidase of human neutrophils is electrogenic and associated with an H+ channel. Biochem J. 1987;246:325–329. doi: 10.1042/bj2460325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Henderson LM, Chappell JB, Jones OTG. Internal pH changes associated with the activity of NADPH oxidase of human neutrophils: further evidence for the presence of an H+ conducting channel. Biochem J. 1988;251:563–567. doi: 10.1042/bj2510563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Henderson LM, Chappell JB, Jones OTG. Superoxide generation by the electrogenic NADPH oxidase of human neutrophils is limited by the movement of a compensating charge. Biochem J. 1988;255:285–290. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Henderson LM, Meech RW. Evidence that the product of the human X-linked CGD gene, gp91-phox, is a voltage-gated H+ pathway. J Gen Physiol. 1999;114:771–785. doi: 10.1085/jgp.114.6.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Henderson LM, Thomas S, Banting G, Chappell JB. The arachidonate-activatable, NADPH oxidase-associated H+ channel is contained within the multi-membrane-spanning N-terminal region of gp91-phox. Biochem J. 1997;325:701–705. doi: 10.1042/bj3250701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Hille B. Ion Channels of Excitable Membranes. 3rd ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc.; 2001. p. 814. [Google Scholar]

- 90.Hladky SB, Haydon DA. Ion transfer across lipid membranes in the presence of gramicidin A: I. studies of the unit conductance channel. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1972;274:294–312. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(72)90178-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Hodgkin AL, Katz B. The effects of sodium ions on the electrical activity of the giant axon of the squid. J Physiol. 1949;108:37–77. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1949.sp004310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Ilan B, Tajkhorshid E, Schulten K, Voth GA. The mechanism of proton exclusion in aquaporin channels. Proteins. 2004;55:223–228. doi: 10.1002/prot.20038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Illek B, Hajighasemi M, Iovannisci DM, Fischer H. Novel missense mutation in HVCN1 results in reduced proton channel function and proton secretion in airways. Ped Pulmonol. 2009 Suppl 32:234. [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jankowski A, Grinstein S. A noninvasive fluorometric procedure for measurement of membrane potential. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:26098–26104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.37.26098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jankowski A, Scott CC, Grinstein S. Determinants of the phagosomal pH in neutrophils. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:6059–6066. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110059200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jentsch TJ. Chloride and the endosomal-lysosomal pathway: emerging roles of CLC chloride transporters. J Physiol. 2007;578:633–640. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jiang Q, Griffin DA, Barofsky DF, Hurst JK. Intraphagosomal chlorination dynamics and yields determined using unique fluorescent bacterial mimics. Chem Res Toxicol. 1997;10:1080–1089. doi: 10.1021/tx9700984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Johansson A, Jesaitis AJ, Lundqvist H, Magnusson KE, Sjölin C, Karlsson A, Dahlgren C. Different subcellular localization of cytochrome b and the dormant NADPH-oxidase in neutrophils and macrophages: effect on the production of reactive oxygen species during phagocytosis. Cell Immunol. 1995;161:61–71. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1995.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Johnston RB, Jr, Keele BB, Jr, Misra HP, Lehmeyer JE, Webb LS, Baehner RL, Rajagopalan KV. The role of superoxide anion generation in phagocytic bactericidal activity. Studies with normal and chronic granulomatous disease leukocytes. J Clin Invest. 1975;55:1357–1372. doi: 10.1172/JCI108055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Jones GS, VanDyke K, Castranova V. Transmembrane potential changes associated with superoxide release from human granulocytes. J Cell Physiol. 1981;106:75–83. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041060109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kapus A, Szászi K, Ligeti E. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate activates an electrogenic H+-conducting pathway in the membrane of neutrophils. Biochem J. 1992;281:697–701. doi: 10.1042/bj2810697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Kettle AJ, Anderson RF, Hampton MB, Winterbourn CC. Reactions of superoxide with myeloperoxidase. Biochemistry. 2007;46:4888–4897. doi: 10.1021/bi602587k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Khanna R, Roy L, Zhu X, Schlichter LC. K+ channels and the microglial respiratory burst. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2001;280:C796–C806. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.2001.280.4.C796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kinsella JL, Aronson PS. Properties of the Na+-H+ exchanger in renal microvillus membrane vesicles. Am J Physiol. 1980;238:F461–F469. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1980.238.6.F461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Klebanoff SJ. Oxygen metabolites from phagocytes. In: Gallin JI, Snyderman R, editors. Inflammation: Basic Principles and Clinical Correlates. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 1999. pp. 721–768. [Google Scholar]

- 106.Klebanoff SJ. Myeloperoxidase: friend and foe. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;77:598–625. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1204697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Koch HP, Kurokawa T, Okochi Y, Sasaki M, Okamura Y, Larsson HP. Multimeric nature of voltage-gated proton channels. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:9111–9116. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801553105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Korchak HM, Weissmann G. Changes in membrane potential of human granulocytes antecede the metabolic responses to surface stimulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1978;75:3818–3822. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Kuno M, Ando H, Morihata H, Sakai H, Mori H, Sawada M, Oiki S. Temperature dependence of proton permeation through a voltage-gated proton channel. J Gen Physiol. 2009;134:191–205. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200910213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kuno M, Kawawaki J, Nakamura F. A highly temperature-sensitive proton conductance in mouse bone marrow-derived mast cells. J Gen Physiol. 1997;109:731–740. doi: 10.1085/jgp.109.6.731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Lacy P, Abdel Latif D, Steward M, Musat-Marcu S, Man SFP, Moqbel R. Divergence of mechanisms regulating respiratory burst in blood and sputum eosinophils and neutrophils from atopic subjects. J Immunol. 2003;170:2670–2679. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.5.2670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Laggner H, Phillipp K, Goldenberg H. Free zinc inhibits transport of vitamin C in differentiated HL-60 cells during respiratory burst. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:436–443. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Lamb FS, Moreland JG, Miller FJ., Jr Electrophysiology of reactive oxygen production in signaling endosomes. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2009;11:1335–1347. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Lambeth JD. Nox enzymes, ROS, and chronic disease: an example of antagonistic pleiotropy. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:332–347. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Lear JD, Wasserman ZR, DeGrado WF. Synthetic amphiphilic peptide models for protein ion channels. Science. 1988;240:1177–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.2453923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lee SY, Letts JA, MacKinnon R. Dimeric subunit stoichiometry of the human voltage-dependent proton channel Hv1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:7692–7695. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0803277105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Levis RA, Rae JL. The use of quartz patch pipettes for low noise single channel recording. Biophys J. 1993;65:1666–1677. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(93)81224-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Levitt DG, Elias SR, Hautman JM. Number of water molecules coupled to the transport of sodium, potassium and hydrogen ions via gramicidin, nonactin or valinomycin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1978;512:436–451. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(78)90266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Li XJ, Tian W, Stull ND, Grinstein S, Atkinson S, Dinauer MC. A fluorescently tagged C-terminal fragment of p47phox detects NADPH oxidase dynamics during phagocytosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2009;20:1520–1532. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-06-0620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Lin TI, Schroeder C. Definitive assignment of proton selectivity and attoampere unitary current to the M2 ion channel protein of influenza A virus. J Virol. 2001;75:3647–3656. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.8.3647-3656.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Lowenthal A, Levy R. Essential requirement of cytosolic phospholipase A2 for activation of the H+ channel in phagocyte-like cells. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:21603–21608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.31.21603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ma C, Polishchuk AL, Ohigashi Y, Stouffer AL, Schön A, Magavern E, Jing X, Lear JD, Freire E, Lamb RA, DeGrado WF, Pinto LH. Identification of the functional core of the influenza A virus A/M2 proton-selective ion channel. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:12283–12288. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905726106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mahaut-Smith M. The effect of zinc on calcium and hydrogen ion currents in intact snail neurones. J Exp Biol. 1989;145:455–464. doi: 10.1242/jeb.145.1.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Mamonov AB, Coalson RD, Zeidel ML, Mathai JC. Water and deuterium oxide permeability through aquaporin 1: MD predictions and experimental verification. J Gen Physiol. 2007;130:111–116. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200709810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Mankelow TJ, Hu XW, Adams K, Henderson LM. Investigation of the contribution of histidine 119 to the conduction of protons through human Nox2. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:4026–4033. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Marty A, Tan YP, Trautmann A. Three types of calcium-dependent channel in rat lacrimal glands. J Physiol. 1984;357:293–325. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1984.sp015501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Maturana A, Arnaudeau S, Ryser S, Bánfi B, Hossle JP, Schlegel W, Krause KH, Demaurex N. Heme histidine ligands within gp91phox modulate proton conduction by the phagocyte NADPH oxidase. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:30277–30284. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010438200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Maturana A, Krause KH, Demaurex N. NOX family NADPH oxidases: do they have built-in proton channels? J Gen Physiol. 2002;120:781–786. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20028713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.McKenna SM, Davies KJ. The inhibition of bacterial growth by hypochlorous acid. Possible role in the bactericidal activity of phagocytes. Biochem J. 1988;254:685–692. doi: 10.1042/bj2540685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Meech RW, Thomas RC. Voltage-dependent intracellular pH in Helix aspersa neurones. J Physiol. 1987;390:433–452. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1987.sp016710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Menegazzi R, Busetto S, Dri P, Cramer R, Patriarca P. Chloride ion efflux regulates adherence, spreading, and respiratory burst of neutrophils stimulated by tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF) on biologic surfaces. J Cell Biol. 1996;135:511–522. doi: 10.1083/jcb.135.2.511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Milton RH, Abeti R, Averaimo S, DeBiasi S, Vitellaro L, Jiang L, Curmi PM, Breit SN, Duchen MR, Mazzanti M. CLIC1 function is required for β-amyloid-induced generation of reactive oxygen species by microglia. J Neurosci. 2008;28:11488–11499. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2431-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Moffat JC, Vijayvergiya V, Gao PF, Cross TA, Woodbury DJ, Busath DD. Proton transport through influenza A virus M2 protein reconstituted in vesicles. Biophys J. 2008;94:434–445. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.109082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Moreland JG, Davis AP, Bailey G, Nauseef WM, Lamb FS. Anion channels, including ClC-3, are required for normal neutrophil oxidative function, phagocytosis, and transendothelial migration. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12277–12288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511030200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Morgan D, Capasso M, Musset B, Cherny VV, Ríos E, Dyer MJS, DeCoursey TE. Voltage-gated proton channels maintain pH in human neutrophils during phagocytosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:18022–18027. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0905565106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Morgan D, Cherny VV, Finnegan A, Bollinger J, Gelb MH, DeCoursey TE. Sustained activation of proton channels and NADPH oxidase in human eosinophils and murine granulocytes requires PKC but not cPLA2α activity. J Physiol. 2007;579:327–344. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.124248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Morgan D, Cherny VV, Murphy R, Katz BZ, DeCoursey TE. The pH dependence of NADPH oxidase in human eosinophils. J Physiol. 2005;569:419–431. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.094748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Morgan D, Cherny VV, Murphy R, Xu W, Thomas LL, DeCoursey TE. Temperature dependence of NADPH oxidase in human eosinophils. J Physiol. 2003;550:447–458. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2003.041525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Morgan D, Cherny VV, Price MO, Dinauer MC, DeCoursey TE. Absence of proton channels in COS-7 cells expressing functional NADPH oxidase components. J Gen Physiol. 2002;119:571–580. doi: 10.1085/jgp.20018544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Morgan D, Ríos E, DeCoursey TE. Dynamic measurement of the membrane potential of phagocytosing neutrophils by confocal microscopy and SEER (Shifted Excitation and Emission Ratioing) of di-8-ANEPPS. Biophys J. 2009;96:687a. [Google Scholar]