Abstract

Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a disorder of declining language that is a frequent presentation of neurodegenerative diseases such as frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Three variants of PPA are recognized: progressive nonfluent aphasia, semantic dementia, and logopenic progressive aphasia. In an era of etiology-specific treatments for neurodegenerative conditions, determining the histopathological basis of PPA is crucial. Clinicopathological correlations in PPA emphasize the contributory role of dementia with Pick bodies and other tauopathies, TDP-43 proteinopathies, and Alzheimer disease. These data suggest an association between a specific PPA variant and an underlying pathology, although many cases of PPA are associated with an unexpected pathology. Neuroimaging and biofluid biomarkers are now emerging as important adjuncts to clinical diagnosis. There is great hope that the addition of biomarker assessments to careful clinical examination will enable accurate diagnosis of the pathology associated with PPA during a patient’s life, and that such findings will serve as the basis for clinical trials in this spectrum of disease.

Introduction

Humans are highly dependent on language in day-to-day functioning. As a result, language disorders are associated with substantial disability. Aphasia is a central disorder of language comprehension and expression, and its diagnosis requires the exclusion of peripheral sensory and motor deficits that mimic aphasia. The term primary progressive aphasia (PPA) refers specifically to a disorder of deteriorating language, the demographic characteristics of which are summarized in Box 1.

Box 1. Demographic features of primary progressive aphasia.

No community-based estimates of the frequency of primary progressive aphasia (PPA) are available, but a rough estimate can be derived by considering that the etiology is often in the clinical spectrum related to frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). Estimates of the prevalence of FTLD are in the range of 2.7–15.0 per 100,000,113–115 whereas estimates of the annual incidence of FTLD are ≈2.2–3.5 per 100,000 person-years.116,117 Autopsy series from several institutions examining all syndromes associated with FTLD pathology report that ≈20–40% of FTLD cases have PPA.36,39,60–62,67,69,73 The average age of onset tends to be in the late 50s,118 although a wide range is reported, from patients in their 20s up to 82 year-old individuals. Survival is ≈7 years, although the prognosis is highly variable.61,119–123 There is no gender bias, and no environmental risk factors are known.124 Some factors, such as the presence of a learning disability125 or left cranial hypoplasia,126 may be early indicators of PPA, but these factors generally have not been replicated.

An early illustration of PPA was provided by Pick who, in 1892, described a woman with a social disorder involving disinhibition and poor insight.1 Her speech capacity gradually worsened and she became mute. The first report of isolated language decline came in 1893 when Serieux described a patient with worsening speech fluency without accompanying memory, social or visuospatial impairment.2

In the more modern literature, Mesulam reported several cases of slowly progressive aphasia.3 In 2001, Mesulam defined PPA as an aphasic impairment of language that must be the dominant deficit for the first 2 years after symptom onset.4 This language deficit must be insidiously progressive in nature without an identifiable cause, which rules out non-neurodegenerative etiologies such as stroke or malignancy. Minimal memory, visuospatial, executive or social difficulty should be observed during the first 2 years, thereby eliminating neurodegenerative conditions such as typical Alzheimer disease (AD).

The existing clinical criteria for the diagnosis of PPA and associated syndromes have limitations. For example, specific clinical features have received minimal validation in patients with known pathology. In addition, clinical criteria such as the 2 year rule are arbitrary, and no empirical evidence exists to support this particular duration of disease. The recognition of PPA is important for the development of more-appropriate criteria for its diagnosis.

This review focuses on the ascertainment of PPA and determination of its histopathological basis during life. First, the clinical characteristics of the three main PPA syndromes are described. Second, studies evaluating pathology in patients with PPA are reviewed. The identification of a specific PPA syndrome provides consider able information about its etiology, but many cases exist in which the clinical syndrome does not correspond to the expected pathology. Finally, biomarker studies that further define the histopathological basis of PPA are described. Neuroimaging and biofluid biomarkers will be valuable tools for establishing the pathological basis of PPA during life, particularly as a diagnosis made solely on clinical findings has a number of short-comings. As etiology-specific agents become available to treat PPA, identification of the histopathological abnormalities causing PPA in an individual patient becomes increasingly important. Clinical trials have already been designed for patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) syndromes such as PPA,5 but a necessary trial prerequisite—diagnostic accuracy—remains elusive.

Primary progressive aphasia syndromes

A 2010 consensus described recommendations (M. L. Gorno-Tempini et al., personal communication) for recognizing three common forms of PPA: progressive nonfluent aphasia (PNFA), semantic dementia, and logopenic progressive aphasia (LPA). The clinical characteristics of these syndromes are summarized in Box 2. The issue of which clinical features to include in the diagnostic guidelines remains controversial, and opinions differ about the relative importance of the various features. Some patients with PPA might not be easily classified as having one of these syndromes. The three main syndromes of PPA listed above and in Box 2 are, nevertheless, important to recognize because they anchor our current knowledge of the field. Moreover, the specific type of PPA can provide a valuable clue to the underlying pathology in a particular patient.

Box 2. Characteristics of primary progressive aphasia syndromes.

Progressive nonfluent aphasia

▪ Grammatical simplification and errors in language production

▪ Effortful, halting speech with speech sound errors

▪ Two or more of the following: impaired syntactic comprehension; spared content word comprehension; spared object knowledge

Semantic dementia

▪ Poor confrontation naming

▪ Impaired single word comprehension

▪ Three or more of the following: poor object and/or person knowledge; surface dyslexia: spared repetition; spared motor speech

Logopenic progressive aphasia

▪ Impaired single word retrieval

▪ Impaired repetition of phrases and sentences

▪ Three or more of the following: speech sound errors; spared motor speech; spared single word comprehension and object knowledge; absence of agrammatism

Progressive nonfluent aphasia

The hallmark of PNFA is effortful, nonfluent speech,6,7 the rate of which is less than one-third that of healthy adults.8 Some work attributes this essential feature of PNFA to agrammatism,8,9 and the syndrome is also associated with grammatical errors and omissions, as well as simplification of grammatical forms. Patients develop disordered prosody (the rhythm or melody of speech), as well as speech sound errors. Some of the speech sound errors are substitutions and mispronunciations related to a disorder of the phonological system, whereas others are motor-based speech planning errors that are termed apraxia of speech.8,10 In PNFA, effortful speech worsens gradually and patients typically become mute.

PNFA also involves limited comprehension of grammatically complex sentences.11,12 The central nature of aphasic deficits means that impairments in spoken grammatical comprehension and expression are also found in reading and writing. Problems with working memory and dual-tasking may develop over time.13 As in the patient described by Pick,1 a disorder of social functioning can also emerge, manifesting as limited initiation of behavior, apathy, and poor motivation.

Neurological examination in a patient with PNFA can reveal an extrapyramidal disorder involving unilateral myoclonus, dystonia, rigidity and limb apraxia, which might suggest a diagnosis of corticobasal syndrome. A disorder of gait and balance with limited vertical gaze and axial rigidity, as seen in progressive supranuclear palsy,10,14 may be present. PNFA can occur in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, together with bulbar and limb weakness, muscle wasting, and fasciculations.15,16

Semantic dementia

The major clinical features of semantic dementia include confrontation naming difficulty, impaired comprehension of single words, and degraded object knowledge.17–19 word finding is profoundly impaired,20 and speech might seem empty of content because of frequent use of words that have imprecise reference (for example, ‘these’ and ‘that’). Comprehension of language is markedly diminished in patients with semantic dementia because of the degradation of semantic representations.21 Indeed, the semantic impairment seems to be the crucial deficit in semantic dementia, since this interferes with word meaning, naming, and the recognition and use of objects. The precise basis for this deficit, however, is unclear. Some studies argue that impaired semantic memory is widespread and compromises all semantic concepts in patients with semantic dementia.22–24 However, others point out that visual object concepts are more impaired than abstract concepts,25–27 and number concepts are relatively preserved.28 Findings such as these are consistent with the claim that the semantic memory deficit is attributable to degraded representations of visual perceptual features that are crucial to object concepts. Semantic dementia frequently results in surface dyslexia, in which sight vocabulary words are pronounced as written (for example, ‘choir’ being pronounced ‘cho-eere’).19,29

Semantic dementia can be accompanied by a social disorder of which the patient has little insight,30,31 and which emerges as the disease progresses.32 Patients can become obsessive and have passionate changes in political or religious views that are antithetical to previous beliefs. Their personality is often described as cold and they have little empathy for others. Patients who become disinhibited as a result of the disorder will approach strangers on the street with offensive comments; others show hyperoral or hypersexual behavior.

Logopenic progressive aphasia

LPA is characterized by profound difficulty in word finding.33 Repetition of phrases is markedly impaired, partly as a result of limited auditory–verbal short-term memory. As the condition of patients with LPA worsens, limited expression and difficulty in word comprehension can develop. These features are sometimes described as progressive mixed aphasia to reflect the presence of nonfluent speech production and impaired lexical comprehension.34,35 Forman and colleagues36 reported that patients with a clinical diagnosis of a PPA syndrome but who had pathological evidence of AD at autopsy had worse episodic memory than patients with FTLD spectrum pathology. Indeed, the clinical features of LPA are reminiscent of the language impairments frequently described in AD.37 Such features include naming difficulty and repetition deficits that can progress to impaired lexical comprehension and halting speech associated with impaired word finding.

Clinicopathological studies

As etiology-specific agents to treat neurodegenerative conditions become available, determining the cause of PPA during life will be essential to enable the identification of patients who will benefit from these interventions. A thorough neurological examination is useful in rendering a diagnosis, but several factors, such as the ongoing controversy surrounding essential clinical diagnostic features of PPA syndromes, limit the value of a clinical evaluation in determining the cause of PPA. Longitudinal studies of PPA might reveal informative extrapyramidal features consistent with forms of tauopathy such as corticobasal degeneration or progressive supranuclear palsy,14 motor features of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis that are associated with TDP-43 (TAR DNA-binding protein 43) proteinopathy,38 or episodic memory difficulties suggestive of AD.39 However, the emergence of these clinical features often occurs later in the course of the disease. Moreover, clinical observations can be less than definitive: corticobasal degeneration is difficult to diagnose,40,41 ascertaining impaired verbal memory is complicated in patients who have impaired language ability,42,43 and motor neuron disease might be subclinical.16,44 Caveats such as these have emphasized the need to validate observations that link clinical and pathological data.45–50 In summary, data are inconclusive regarding the claim that a specific clinical PPA syndrome reflects the histopathological basis of a progressive language disorder.

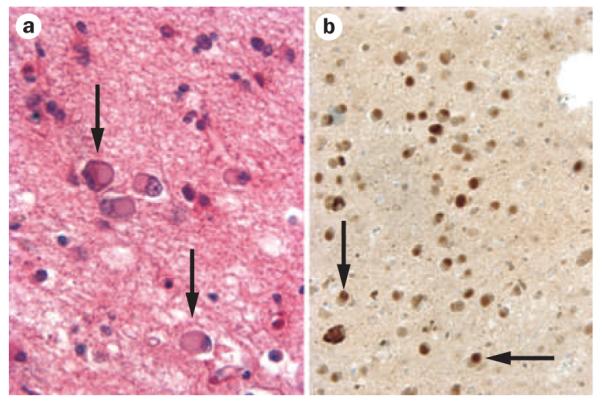

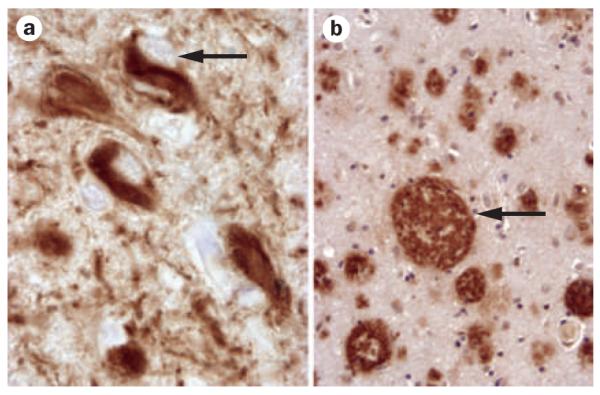

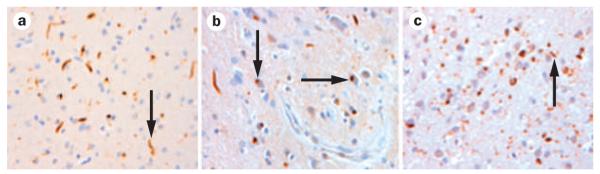

PPA is typically associated with one of three classes of pathology.36,51,52 In some cases, histopathological abnormalities are associated with tau-positive immunoreactivity (as in dementia with Pick bodies [Figure 1], progressive supranuclear palsy or corticobasal degeneration), whereas other patients with PPA have AD pathology (Figure 2). A third class of PPA patients have FTLD histopathology that is negative for tau immunoreactivity but positive for ubiquitin immunoreactivity (FTLD-U). In most of these latter cases, histopathological inclusions are composed of TDP-4353 (FTLD-TDP; Figure 3).54 Four types of TDP-43 pathology exist: dystrophic neurites (known as Sampathu type 1 or Mackenzie type 2 pathology; Figure 3a); dystrophic neurites and neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions (Sampathu type 2 or Mackenzie type 3 pathology; Figure 3b); dystrophic neurites, neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions and neuronal intranuclear inclusions (Sampathu type 3 or Mackenzie type 1 pathology; Figure 3c); and Sampathu type 4 (Mackenzie type 4) pathology, which is seen in patients with mutations of the valosin-containing protein gene.55,56 Rare tau-negative, TDP-43-negative ubiquitinated inclusions have ‘fused in sarcoma’ immunoreactivity known as FTLD-FUS,57 but descriptions of individuals with such inclusions have not included aphasia.58 In rare cases, dementia lacking distinctive histopathology or dementia with Lewy bodies can also cause PPA.

Figure 1.

Tau-positive pathology: dementia with Pick bodies. a | Hemotoxylin and eosin preparation of Pick bodies. b | Tau-immunoreactive Pick bodies. Pick bodies are indicated by arrows; ×200 magnification. Images courtesy of Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Figure 2.

Alzheimer disease pathology. a | Neurofibrillary tangle (arrow). b | Neuritic plaque (arrow). ×400 magnification. Images courtesy of Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Figure 3.

Frontotemporal lobar degeneration TAR DNA-binding protein 43 proteinopathy. a | Dystrophic neurites, indicated by arrow (Sampathu type 1, Mackenzie type 2 pathology). b | Dystrophic neurites and neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions. Arrows indicate cytoplasmic inclusions (Sampathu type 2, Mackenzie type 3 pathology). c | Dystrophic neurites, neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions and neuronal intranuclear inclusions. Arrow indicates intranuclear inclusion (Sampathu type 3, Mackenzie type 1 pathology). ×100 magnification. Images courtesy of Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Progressive nonfluent aphasia

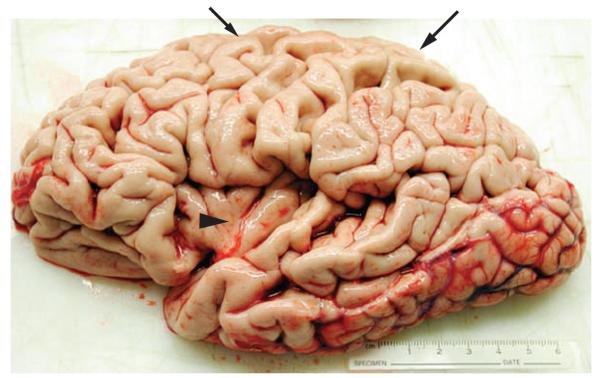

Some studies associate PNFA exclusively with tau-positive pathology (Figure 4). Josephs and colleagues, for example, related nonfluent PPA syndromes involving clinical features of PNFA or apraxia of speech to tau-positive pathology.10 Apraxia of speech was over whelmingly associated with progressive supranuclear palsy, whereas cases with PNFA had corticobasal degeneration. In another study, Yokota et al. reported that the clinical diagnosis of three cases of PNFA in their series was associated only with dementia with Pick bodies pathology.59

Figure 4.

Brain of a patient who had progressive nonfluent aphasia associated with corticobasal degeneration. During life, this patient had hesitant, effortful speech with grammatical errors and some phonological errors, as well as impaired grammatical comprehension, consistent with progressive nonfluent aphasia. Inspection of this left hemisphere specimen at autopsy revealed considerable atrophy in inferior frontal and anterior superior temporal regions, as well as superior parietal and frontal cortices. Arrowhead indicates insula revealed by marked atrophy in inferior frontal and superior temporal portions of the left hemisphere. Large arrow indicates atrophy of the superior parietal lobule; small arrow indicates superior frontal atrophy. Histopathological examination revealed tau-positive ballooned cells and other histopathological features consistent with corticobasal degeneration. Image courtesy of Center for Neurodegenerative Disease Research, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA, USA.

Other researchers have reported variable pathology underlying PNFA. Hodges et al. found one case of dementia lacking distinctive histopathology,60 and Mesulam’s group reported FTLD-U pathology in one of six cases of PNFA.35 In 20 patients with nonfluent PPA, Kertesz and co-workers found AD pathology in nine cases and ‘motor neuron disease-type inclusions’ (presumably FTLD-U) in two cases.61 My group followed nine cases of PNFA longitudinally, and noted AD pathology in three cases.39 Among Knopman’s six nonfluent PPA cases, two had pathology consistent with FTLD-U and one had additional AD pathology.62 Another series that reported a wider range of pathologies from the same institution found dementia with Pick bodies, FTLD-U, progressive supranuclear palsy, and corticobasal degeneration pathology among patients with PNFA.63 The Cambridge, UK group catalogued a variety of pathologies among their 23 patients with nonfluent PPA, including AD in seven cases,64,65 dementia lacking distinctive histopathology in one case, and ‘motor neuron disease inclusion dementia’ (presumably FTLD-U) in four patients.66 Snowden et al. found FTLD-TDP pathology in eight of nine patients with PNFA.67 Two groups also reported PNFA cases with FTLD-TDP pathology.56,68 The TDP-43 variant with frequent dystrophic neurites and neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions seemed to be particularly prominent in PNFA.68 Kertesz et al.61 and the updated University of Pennsylvania series (summarized in Table 1) each found single cases of PNFA with the pathological features of dementia with Lewy bodies.

Table 1.

Representative survey of clinicopathological correlations in primary progressive aphasia

| Study | Number of eligible cases* |

PNFA (%)‡ |

Semantic dementia (%) |

LPA (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tau | FTLD-U§ | Other | Tau | FTLD-U§ | Other | Tau | FTLD-U§ | Other | ||

| Knopman et al. (2005)47 |

7 of 35‡ | 57.1 | 14.3 | AD and/or DLDH 14.3 |

0.0 | 14.3 | 0.0 | NS | NS | NS |

| Snowden et al. (2007)67 |

18 of 65 | 5.5 | 44.4 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 50.0 | 0.0 | NS | NS | NS |

| Kertesz et al. (2005)61 |

22 of 60 | 36.4 | 9.1 | AD 40.9 DLB 4.5 |

0.0 | 9.1 | 0.0 | NS | NS | NS |

| Mesulam et al. (2008)35 |

Nonfluent-only 17 of 23 |

29.4 | 5.9 | 0.0 | NS | NS | NS | 5.9 | 17.6 | AD 41.1 |

| Josephs et al. (2006)10 |

Nonfluent-only 17 of 17 |

58.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | NS | NS | NS | 11.8 | 29.4 | 0.0 |

| Knibb et al. (2006)66 |

38 of 38§ | 26.3 | 10.5 | AD 18.4 DLDH 2.6 Mixed 2.6 |

5.3 | 21.1 | AD 13.2 | NS | NS | NS |

| Grossman et al. (unpublished work) |

26 of 26 | 23.1 | 0.0 | AD 15.4 DLB 3.8 |

0 | 19.2 | AD 15.4 | 0.0 | 3.8 | AD 19.2 |

| Average (%)∥ | Total number = 145 |

30.3 | 11.0 | 17.2 | 1.4 | 17.2 | 6.2 | 2.1 | 6.2 | 8.3 |

Reported clinicopathological studies used entry criteria based on the clinical syndrome, noting the percentage of cases with a specific syndrome who had a particular pathology. Discrepancies across series may be seen for several different reasons, such as differences in clinical or pathological criteria across institutions; the varying time points at which patients were allocated to a clinical diagnostic category; or unavoidable case selection and referral biases. Such inconsistencies emphasize the importance of implementing consensus clinical and pathological diagnostic criteria across multiple collaborating centers.

Eligible cases include patients in a series with a primary diagnosis of a variant of PPA.

Includes nonfluent cases before the recognition of the LPA phenotype.

FTLD-U pathology before the discovery of TDP-43 and widespread use of TDP-43 in pathology studies in 2006.

Cases of FTLD-U and DLDH pathology before 2006 were grouped with cases of FTLD-TDP after 2006 to account for any potential differences in data collected before and after the identification of TDP-43. Nonfluent forms of PPA were classified as PNFA unless the investigators specifically classified the patients as LPA to account for difficulties associated with distinguishing LPA from PNFA before 2004. Abbreviations: AD, Alzheimer disease; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; DLDH, dementia lacking distinctive histopathology; FTLD-U, frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive pathology, LPA, logopenic progressive aphasia; NS, not sampled; PNFA, progressive nonfluent aphasia; PPA, primary progressive aphasia; TDP-43, TAR DNA-binding protein 43.

Semantic dementia

Several series have reported that semantic dementia is exclusively associated with FTLD-U and its variant FTLD-TDP. The single case with semantic dementia in the series reported by Knopman et al. had FTLD-U.62 Kertesz et al.’s longitudinal study identified two apparent cases of semantic dementia, both of whom had FTLD-U pathology.61 The longitudinal series reported by my group also found FTLD-U pathology in the single case of semantic dementia.39 Following up on a previous analysis,69 Snowden and co-workers found that that all nine patients with semantic dementia in their series had FTLD-TDP at autopsy.67 Unlike in PNFA, the form of TDP-43 pathology found in semantic dementia is characterized by dystrophic neurites, but rarely manifests as neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions, and has not, to date, been reported with neuronal intranuclear inclusions.56,68,70

Semantic dementia has not, however, been universally related to FTLD-U. The group in Cambridge, UK reported three patients with semantic dementia who had dementia with Pick bodies;60,71 other cases had AD pathology.64,66,71 The updated series from the University of Pennsylvania (Table 1) also found cases of semantic dementia with AD pathology.

Logopenic progressive aphasia

In a series reported in 2008, all five patients with PPA who had AD pathology had an LPA phenotype.72 Another series found cases of LPA to be associated with tau-positive inclusions, FTLD-U pathology, or AD.35 The updated University of Pennsylvania series found AD in addition to FTLD-TDP pathology in cases of LPA.39

Overview of clinicopathological associations

Table 1 summarizes the results of clinicopathological studies in 145 well-characterized cases with autopsy-confirmed pathological diagnoses from recent series conducted at seven different institutions. The data show preferential associations between a clinical PPA syndrome and a specific neuropathological finding for at least half the patients with PPA. In PNFA, over half the cases have tau-positive pathology, including dementia with Pick bodies, corticobasal degeneration and progressive supranuclear palsy. Over two-thirds of cases of semantic dementia have FTLD-U pathology that is likely to be related to TDP-43. LPA is associated with AD pathology in half of the reported cases. Careful clinical evaluations thus have an important role in the assessment of patients with PPA.

Although a particular pathology is associated with a specific PPA syndrome in many cases, frequent exceptions exist. The clinical diagnosis of a PPA syndrome thus does not reliably define the pathology present in an individual patient. For example, although PNFA is most often associated with tau-positive pathology, many patients with PNFA have FTLD-U pathology, presumably caused by TDP-43, and others have AD. Similar heterogeneity is observed in semantic dementia. Most patients with semantic dementia have FTLD-U pathology, often related to TDP-43, but several such patients have AD or tau-positive pathology. In addition, although LPA is often associated with AD, some LPA cases have FTLD-U pathology, and others are associated with a tau-positive pathology. Recognition of a specific PPA syndrome is important because each variant is associated with a specific histopathology, but predicting a specific pathological finding from a particular PPA syndrome in an individual patient remains problematic.

Biomarkers for primary progressive aphasia

In light of the somewhat inconsistent clinicopathological relationships in PPA, additional information is needed to help determine the pathology underlying the disorder. Four classes of biomarkers—quantitative neuropsychological biomarkers, imaging biomarkers, genetic bio markers and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarkers—have been validated in autopsy-confirmed cases and have the potential to contribute to the diagnostic accuracy of PPA.

Quantitative neuropsychological biomarkers

The capacity to determine the underlying pathology of a PPA syndrome may be blunted by bundling multiple attributes into a single syndrome. Indeed, clinical characteristics such as nonfluent speech and naming difficulty contribute to more than one PPA syndrome. Moreover, the value of this kind of feature to predict pathology is lessened when it is considered dichotomously (that is, present versus absent), as is the common practice in most clinical syndromes, rather than parametrically (that is, according to the degree of impairment).

Several studies have assessed language and cognition quantitatively in autopsy-proven PPA. An evaluation of nonfluent PPA revealed apraxia of speech in all patients with tauopathy but not in patients with FTLD-U pathology.10 Compared with patients with TDP-43 proteinopathy and patients with AD pathology, patients with tau-positive pathology, which is associated with PNFA, are significantly more impaired on executive measures involving visual constructions and reverse digit span.39,73 By contrast, patients with TDP-43 proteinopathy, which is associated with semantic dementia, have significantly greater impairments in confrontation naming and category naming fluency than patients with tauopathy or AD pathology.39,72,73 This double dissociation—worse executive functioning in patients with tauopathy but worse lexical retrieval in patients with TDP-43 proteinopathy—is maintained longitudinally, so the relative performance of a patient on these measures might be a useful diagnostic guide during the entire course of these conditions. Episodic memory is more impaired in PPA due to AD pathology than in PPA due to tau or FTLD spectrum pathology.36,74

Imaging biomarkers

Structural imaging such as MRI, as well as functional imaging with PET, have identified selective interruptions of the large-scale language network (Box 3) in the left hemisphere that are associated with particular PPA syndromes (Figure 5).

Box 3. The large-scale neural network that supports language.

Combinations of representational and processing nodes within a large-scale neural network in the left hemisphere collaborate to support crucial features of language.127,128 The words we hear are translated from auditory–sensory input into speech sounds in inferior parietal and superior temporal regions adjacent to the Sylvian fissure. Speech sounds are interpreted as word forms linked with a concept in posterior–lateral and anterior–inferior temporal areas. Inferior and lateral prefrontal regions interpret word order and assemble words into grammatical sentences. Language expression depends on similar semantic and grammatical processes, and selected word forms are formulated as speech sounds in the inferior and insular regions of the frontal lobe. Phenotypic distinctions in primary progressive aphasia depend on which portion of this large-scale language network is compromised.

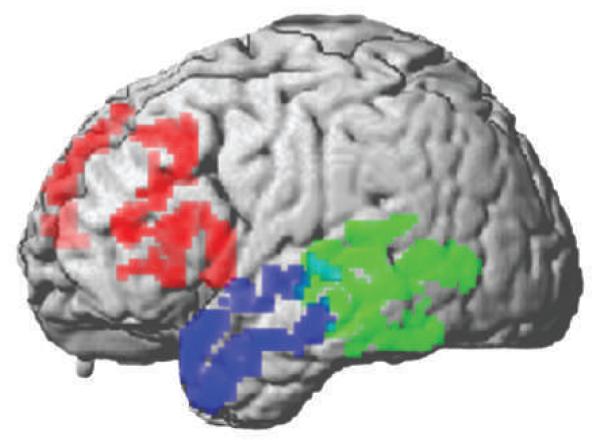

Figure 5.

Distribution of cortical atrophy in three primary progressive aphasia syndromes. This image is based on a quantitative cortical thickness analysis of high-resolution 3T MRI studies129 in patients with primary progressive aphasia. Statistically significant cortical thinning is observed in inferior, dorsolateral prefrontal and insular regions of the left frontal lobe in progressive nonfluent aphasia (red, n = 12 patients), in the left lateral temporal and inferior parietal regions in logopenic progressive aphasia (green, n = 9 patients), and in the left anterior temporal lobe in semantic dementia (blue, n = 11 patients) relative to age-matched healthy adults.

PNFA is associated with anterior peri-Sylvian atrophy involving inferior, opercular and insular portions of the left frontal lobe.11,33 Over time, atrophy in PNFA extends superiorly into dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, inferiorly into superior temporal cortex, medially into orbital and anterior cingulate regions, and posteriorly along the Sylvian fissure into the parietal lobe. Inferior frontal and superior temporal cortical thinning is seen in patients with PNFA who have autopsy-proven tau-positive disease.75 Reduced parietal cortex functioning is seen on PET scans or single-photon emission CT scans of patients who have PNFA and pathologically confirmed AD, but not in patients without AD pathology.76

Semantic dementia is associated with left anterior temporal atrophy affecting lateral and ventral surfaces as well as the anterior hippocampus and the amygdala.77 Rare studies involving longitudinal imaging show atrophy extending posteriorly and superiorly in the ipsilateral temporal lobe, and anterior temporal regions of the right hemisphere are frequently implicated.78 Prominent left anterior temporal thinning is seen in patients with semantic dementia who have FTLD-U pathology at autopsy.72,73,75

LPA is associated with posterior peri-Sylvian atrophy.33 Longitudinal observations suggest progressive disease extending into more-inferior regions of the temporal lobe, superior extension into the parietal lobe, and anterior extension along the Sylvian fissure into the frontal lobe. Studies evaluating patients with a form of PPA associated with AD pathology have shown temporal–parietal atrophy. One of these studies showed sparing of the hippocampus,72 whereas a second study found hippocampal atrophy.73

Various histopathological abnormalities can potentially accumulate in the anatomical regions implicated in PPA. PET metabolic imaging with Pittsburgh compound B (PIB) can establish the specific cause of some PPA syndromes, as this compound tags amyloid-β (Aβ), a peptide that accumulates in AD but not in tauopathies or TDP-43 proteinopathies.79 One report found that PIB uptake was lower in eight of 12 patients clinically diagnosed as having FTLD than it was in patients with AD.80 A 2008 study of PPA reported PIB uptake in all four patients with LPA who were evaluated.81 The signal was strongest in a left temporal–parietal distribution, consistent with the anatomical distribution of pathology in LPA caused by AD. By comparison, left frontal uptake was seen in only one of six patients with PNFA in that study, and left temporal uptake was seen in one of five patients with semantic dementia, suggesting that AD pathology is less common in PNFA and semantic dementia than in LPA. Considerable caution should be exercised when interpreting these data, because limited autopsy confirmation of PIB imaging results in PPA is available. Moreover, a substantial number of older adults have an amyloid burden at autopsy that is consistent with AD, even though they are cognitively intact. In addition, quantitative analyses of the anatomical locus of the histopathological burden in patients with PPA who have AD pathology do not always correspond to the expected an atomical distribution of the PPA syndrome.35,36,82

Several studies have attempted to improve the diagnosis of PPA through multimodal imaging. In one report, regression analyses combined structural MRI scans with language measures to identify the pathological basis of PNFA and LPA.83 In patients with AD pathology, visual confrontation naming was significantly impaired, whereas letter-guided category naming fluency was most impaired in patients with FTLD spectrum pathology. Temporal–parietal atrophy was seen in AD regardless of the clinical syndrome. Patients who had PNFA due to FTLD pathology had inferior and dorsolateral frontal atrophy, whereas patients who had LPA due to FTLD had posterior peri-Sylvian atrophy. A receiver operating characteristic curve analysis combined distinguishing neuropsychological and imaging features to yield 90% diagnostic accuracy. Additional research on biomarkers is needed to help specify the causes of these PPA syndromes during life.

Genetic biomarkers

DNA can provide important diagnostic information in PPA through the identification of inherited mutations in chromosomes coding for proteins implicated in the pathogenesis of this condition. Autosomal dominant familial disorders are frequent in FTLD, and up to 45% of cases have a strongly positive family history.84,85 Mutation of the progranulin gene (PGRN) on chromosome 17 is reliably associated with FTLD-TDP pathology. Studies of families with PPA have identified inherited abnormalities that are associated with this condition. For example, one study found that affected members of two families with a PGRN mutation had PNFA combined with a behavioral disorder.86 A second report described two families in which most affected individuals had PNFA associated with a PGRN mutation.87 Despite these findings, the presence of a PGRN mutation does not necessarily lead to the presence of PPA.88 PPA is quite uncommon at presentation in patients with a PGRN mutation, although a language disorder eventually emerges in many individuals carrying this mutation.89 Moreover, the clinical symptoms of an FTLD syndrome can vary greatly even in members of a family with the same PGRN mutation.90,91

Some patients with a familial FTLD syndrome have a mutation of the tau-encoding MAPT (microtubule-associated protein tau) gene, which is also located on chromosome 17. The phenotype associated with a specific MAPT mutation is highly variable.92 A comparison of phenotypes across mutations showed that a notable reduction in speech ability occurred more commonly in patients with a PGRN mutation than in those with an MAPT mutation.93 About one-third of patients with a PGRN mutation exhibited aphasic features characteristic of a PPA variant, typically PNFA; patients with an MAPT mutation more commonly showed characteristics of semantic dementia, although never without a preceding social disorder. Other less commonly mutated genes in FTLD include VCP (which encodes valosin-containing protein) on chromosome 9, CHMP2B (which encodes a component of the endosomal sorting complex required for transport III complex) on chromosome 3, and TARDP (TAR DNA-binding protein) on chromosome 1, but familial PPA has not been reported to result from mutations in any of these genes. An increased incidence of methionine–valine heterozygosity at codon 129 of the prion protein gene PrP is, however, strongly associated with PPA.94

Biomarkers linked with genetic factors might also have a role in defining the pathological basis of PPA. One study found an association between the H1 haplotype of MAPT and the sporadic form of PPA.95 Another potential biomarker for PPA is apolipoprotein E ε4 (APOE ε4). As this biomarker is associated with AD pathology, the frequency of the APOE ε4 allele might potentially allow differentiation between PPA caused by AD pathology and that caused by FTLD spectrum pathology. However, the frequency of the APOE ε4 allele does not seem to be elevated in PPA associated with FTLD spectrum pathology or PPA associated with AD.35,96

Additional potential biomarkers can be found in the plasma. For example, the percentages of patients with FTLD or AD who have detectable levels of TDP-43 in their plasma (46% and 22%, respectively) correspond to the percentages of patients in these groups with TDP-43 detected in their brains.97 Affected and clinically unaffected individuals with a PGRN mutation have significantly lower plasma progranulin levels than do noncarrier relatives.98–100 Although biomarkers hold immense promise for distinguishing between TDP-43 protein pathology and tau-positive pathology, these markers need to be validated with autopsy studies and studied in patients with a PPA syndrome. Other genetic biomarkers should become available in the future.

Cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers

CSF provides a further source of potential biomarkers for PPA. CSF, which bathes the brain, contains proteins such as tau and Aβ, and may reflect the underlying pathology of PPA more directly than plasma. Many studies have shown that AD is associated with elevated CSF levels of total tau and of tau phosphorylated at its 181 phosphorylation site, together with reduced levels of the Aβ1–42 peptide. A comparative study found that a different pattern exists in FTLD; ≈20% of patients clinically diagnosed as having FTLD had significantly reduced CSF tau levels relative to controls, but this finding was not seen in patients with AD, and the ratio of tau to Aβ1–42 was another useful way to distinguish FTLD from AD.101 This finding is controversial, however, as elevated CSF tau levels have been observed in patients clinically diagnosed as having FTLD,102–104 and other studies have not found that the ratio of tau to Aβ1–42 can distinguish between FTLD and AD.105 Nevertheless, in patients with known pathology, the ratio of CSF tau to Aβ1–42 has been found to be significantly lower in patients with FTLD than in those with AD. A receiver operating characteristic curve analysis found that a cut-off tau:Aβ1–42 ratio of 1.06 had excellent sensitivity and specificity for distinguishing FTLD from AD.106 Tau-positive disease could not be dissociated from TDP-43 proteinopathies in patients with FTLD on the basis of tau and Aβ1–42 levels. Specific forms of tau in the CSF could be useful for the diagnosis of tauopathies in patients clinically diagnosed as having progressive supranuclear palsy or corticobasal degeneration,107,108 but these data must be interpreted cautiously because of the poor reliability of the clinical diagnosis of these conditions.

CSF levels of TDP-43 have been assayed in patients with a clinical diagnosis of FTLD or amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. In one study, CSF levels of TDP-43 were significantly higher in patients with FTLD or amyotrophic lateral sclero sis than in controls, although values overlapped considerably in cases and controls.109 Another study reported significantly elevated CSF levels of TDP-43 in 6 of 30 patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis,110 and individuals with PGRN mutations have been found to have reduced CSF levels of progranulin.100 Novel potential biomarkers, such as cystatin C, transthyretin, neurosecretory protein VGF, and chromogranin B, have also been identified in the CSF of patients with FTLD.111,112 Promising preliminary findings such as these emphasize the need for additional work to optimize the identification of patients with PPA who have tau or TDP-43 pathology.

Conclusions

This Review highlights the value of a multimodal approach to defining pathology in PPA. The clinical identification of a specific PPA syndrome provides important preliminary information about the likely cause of PPA, and biomarkers can provide useful additional information. Neuroimaging studies can define the neuroanatomical basis of a PPA syndrome, and PET metabolic imaging with PIB can be used to identify AD presenting as a variant of PPA. A CSF analyte profile also can help to define the histopathological cause of PPA. Combinations of these biomarkers can supplement clinical diagnosis and help identify the pathological basis of PPa during life. The discovery of a genetic mutation consistent with tauopathy or TDP-43 proteinopathy can provide definitive information about the etiology of PPA. In the future, novel biomarkers will, hopefully, enable the pathological basis of sporadic PPA to be determined with considerable specificity during a patient’s life, which will open the way for etiology-specific treatments.

Key points.

▪ Primary progressive aphasia (PPA) is a major clinical presentation of frontotemporal lobar degeneration, a frequent neurodegenerative condition presenting in the presenium

▪ PPA has several distinct presentations, including progressive nonfluent aphasia, semantic dementia, and logopenic progressive aphasia

▪ Autopsy studies show that these syndromes are associated preferentially with a particular underlying pathology, but are not diagnostic of these pathologies

▪ Advances in imaging and biofluid biomarkers in the coming years should facilitate the diagnosis of specific pathology in patients with PPA

Acknowledgments

The author’s work is supported in part by the NIH (AG17586, AG15116, NS44266 and NS53488). The author would also like to express his appreciation to John Q. Trojanowski and William T. Hu for their thoughtful comments on an early version of this paper, and to the patients with primary progressive aphasia and their families who contribute enthusiastically to our work.

Désirée Lie, University of California, Orange, CA, is the author of and is solely responsible for the content of the learning objectives, questions and answers of the MedscapeCME-accredited continuing medical education activity associated with this article.

Footnotes

Competing interests The author declares associations with the following companies: Allon Therapeutics, Pfizer. See the article online for full details of the relationships. The Journal Editor H. Wood and the CME questions author D. Lie declare no competing interests.

Review criteria MEDLINE and PubMed databases were searched using the terms “primary progressive aphasia”, “progressive non-fluent aphasia”, “semantic dementia”, “frontotemporal dementia”, “frontotemporal degeneration” and “frontotemporal lobar degeneration”, alone and in combination with “pathology”, “tau”, “tauopathy”, “TDP-43”, “TDP-43 proteinopathy” and “Alzheimer’s disease”. Full-text papers published in English were included and the bibliographies of identified papers were also used to identify additional papers on the topic of this Review.

References

- 1.Pick A. On the relationship between senile cerebral atrophy and aphasia [German] Prager Medicinische Wochenschrift. 1892;17:165–167. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serieux P. On a case of pure verbal deafness [French] Revue Medicale. 1893;13:733–750. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mesulam MM. Slowly progressive aphasia without generalized dementia. Ann. Neurol. 1982;11:592–598. doi: 10.1002/ana.410110607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mesulam MM. Primary progressive aphasia. Ann. Neurol. 2001;49:425–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Knopman DS, et al. Development of methodology for conducting clinical trials in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Brain. 2008;131:2957–2968. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grossman M, et al. Progressive non-fluent aphasia: Language, cognitive and PET measures contrasted with probable Alzheimer’s disease. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 1996;8:135–154. doi: 10.1162/jocn.1996.8.2.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snowden JS, Neary D, Mann DM. Fronto-temporal Lobar Degeneration: Fronto-temporal Dementia, Progressive Aphasia, Semantic Dementia. Churchill Livingstone; New York: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ash S, et al. Non-fluent speech in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J. Neurolinguistics. 2009;22:370–383. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2008.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gunawardena D, et al. Why are progressive non-fluent aphasics non-fluent? Neurology. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 10.Josephs KA, et al. Clinicopathological and imaging correlates of progressive aphasia and apraxia of speech. Brain. 2006;129:1385–1398. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Peelle JE, et al. Sentence comprehension and voxel-based morphometry in progressive nonfluent aphasia, semantic dementia, and nonaphasic frontotemporal dementia. J. Neurolinguistics. 2008;21:418–432. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2008.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mesulam M, et al. Quantitative template for subtyping primary progressive aphasia. Arch. Neurol. 2009;66:1545–1551. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Libon DJ, et al. Neuropsychological decline in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: A longitudinal analysis. Neuropsychology. 2009;23:337–346. doi: 10.1037/a0014995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Murray R, et al. Cognitive and motor assessment in autopsy-proven corticobasal degeneration. Neurology. 2007;68:1274–1283. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259519.78480.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heidler-Gary J, Hillis AE. Distinctions between the dementia in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis with frontotemporal dementia and the dementia of Alzheimer’s disease. Amyotroph. Lateral Scler. 2007;8:276–282. doi: 10.1080/17482960701381911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lomen-Hoerth C, Anderson T, Miller B. The overlap of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2002;59:1077–1079. doi: 10.1212/wnl.59.7.1077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hodges JR, Patterson K, Oxbury S, Funnell E. Semantic dementia: progressive fluent aphasia with temporal lobe atrophy. Brain. 1992;115:1783–1806. doi: 10.1093/brain/115.6.1783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snowden JS, Goulding PJ, Neary D. Semantic dementia: a form of circumscribed cerebral atrophy. Behav. Neurol. 1989;2:167–182. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hodges JR, Patterson K. Semantic dementia: a unique clinicopathological syndrome. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:1004–1014. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70266-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grossman M, et al. What’s in a name: voxel-based morphometric analyses of MRI and naming difficulty in Alzheimer’s disease, frontotemporal dementia, and corticobasal degeneration. Brain. 2004;127:628–649. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patterson K, Nestor PJ, Rogers TT. Where do you know what you know? The representation of semantic knowledge in the human brain. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:976–987. doi: 10.1038/nrn2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bozeat S, Lambon Ralph MA, Patterson K, Garrard P, Hodges JR. Non-verbal semantic impairment in semantic dementia. Neuropsychologia. 2000;38:1207–1215. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(00)00034-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bozeat S, Lambon Ralph MA, Patterson K, Hodges JR. When objects lose their meaning: what happens to their use? Cogn. Affect. Behav. Neurosci. 2002;2:236–251. doi: 10.3758/cabn.2.3.236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lambon Ralph MA, Graham KS, Patterson K, Hodges JR. Is a picture worth a thousand words? Evidence from concept definitions by patients with semantic dementia. Brain Lang. 1999;70:309–335. doi: 10.1006/brln.1999.2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yi HA, Moore P, Grossman M. Reversal of the concreteness effect for verbs in semantic dementia. Neuropsychology. 2007;21:9–19. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.21.1.9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bonner MF, et al. Reversal of the concreteness effect in semantic dementia. Cogn. Neuropsychol. doi: 10.1080/02643290903512305. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Warrington EK. The selective impairment of semantic memory. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 1975;27:635–657. doi: 10.1080/14640747508400525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halpern C, et al. Dissociation of numbers and objects in corticobasal degeneration and semantic dementia. Neurology. 2004;62:1163–1169. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000118209.95423.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patterson K, Hodges JR. Deterioration of word meaning: implications for reading. Neuropsychologia. 1992;30:1025–1040. doi: 10.1016/0028-3932(92)90096-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Snowden JS, et al. Distinct behavioural profiles in frontotemporal dementia and semantic dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2001;70:323–332. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.70.3.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu W, et al. Behavioral disorders in the frontal and temporal variants of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2004;62:742–748. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000113729.77161.c9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Czarnecki K, et al. Very early semantic dementia with progressive temporal lobe atrophy: an 8-year longitudinal study. Arch. Neurol. 2008;65:1659–1663. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2008.507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gorno-Tempini M, et al. Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann. Neurol. 2004;55:335–346. doi: 10.1002/ana.10825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Grossman M, Ash S. Primary progressive aphasia: a review. Neurocase. 2004;10:3–18. doi: 10.1080/13554790490960440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mesulam M, et al. Alzheimer and frontotemporal pathology in subsets of primary progressive aphasia. Ann. Neurol. 2008;63:709–719. doi: 10.1002/ana.21388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Forman MS, et al. Frontotemporal dementia: clinicopathological correlations. Ann. Neurol. 2006;59:952–962. doi: 10.1002/ana.20873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grossman M, Mega M, Cummings JL, Joynt RJ, Griggs RC. In: Clinical Neurology. Baker AB, Joynt RJ, editors. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; Philadelphia: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hu WT, et al. Survival profiles of patients with frontotemporal dementia and motor neuron disease. Arch. Neurol. 2009;66:1359–1364. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2009.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Grossman M, et al. Longitudinal decline in autopsy-defined frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2008;70:2036–2045. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000303816.25065.bc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Boeve BF, et al. Pathologic heterogeneity in clinically diagnosed corticobasal degeneration. Neurology. 1999;53:795–800. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.4.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Litvan I, et al. Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of corticobasal degeneration: a clinicopathologic study. Neurology. 1997;48:119–125. doi: 10.1212/wnl.48.1.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nestor PJ, Fryer TD, Hodges JR. Declarative memory impairments in Alzheimer’s disease and semantic dementia. Neuroimage. 2006;30:1010–1020. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Libon DJ, et al. Patterns of neuropsychological impairment in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2007;68:369–375. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252820.81313.9b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Josephs KA, et al. Clinically undetected motor neuron disease in pathologically proven frontotemporal lobar degeneration with motor neuron disease. Arch. Neurol. 2006;63:506–512. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.4.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rossor MN, Revesz T, Lantos PL, Warrington EK. Semantic dementia with ubiquitin-positive tau-negative inclusion bodies. Brain. 2000;123:267–276. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.2.267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turner RS, Kenyon LC, Trojanowski JQ, Gonatas N, Grossman M. Clinical, neuroimaging, and pathologic features of progressive nonfluent aphasia. Ann. Neurol. 1996;39:166–173. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lieberman AP, et al. Cognitive, neuroimaging, and pathologic studies in a patient with Pick’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 1998;43:259–264. doi: 10.1002/ana.410430218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kertesz A, Hudson L, Mackenzie IR, Munoz DG. The pathology and nosology of primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 1994;44:2065–2072. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.11.2065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ikeda K, et al. Corticobasal degeneration with primary progressive aphasia and accentuated cortical lesion in superior temporal gyrus: case report and review. Acta Neuropathol. 1996;92:534–539. doi: 10.1007/s004010050558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lippa CF, Cohen R, Smith TW, Drachman DA. Primary progressive aphasia with focal neuronal achromasia. Neurology. 1991;41:882–886. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.6.882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mann DM, South PW, Snowden JS, Neary D. Dementia of frontal lobe type: neuropathology and immunohistochemistry. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1993;56:605–614. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.56.6.605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lipton AM, White CL, Bigio EH. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration with motor neuron disease-type inclusions predominates in 76 cases of frontotemporal degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2004;108:379–385. doi: 10.1007/s00401-004-0900-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Neumann M, et al. Ubiquinated TDP-43 in frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Science. 2006;314:130–133. doi: 10.1126/science.1134108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mackenzie I, et al. Nomenclature for neuropathologic subtypes of frontotemporal lobar degeneration: consensus recommendations. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:15–18. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0460-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sampathu DM, et al. Pathological heterogeneity of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions delineated by ubiquitin immunohistochemistry and novel monoclonal antibodies. Am. J. Pathol. 2006;169:1343–1352. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.060438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mackenzie IR, et al. Heterogeneity of ubiquitin pathology in frontotemporal lobar degeneration: classification and relation to clinical phenotype. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112:539–549. doi: 10.1007/s00401-006-0138-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Neumann M, et al. A new subtype of frontotemporal lobar degeneration with FUS pathology. Brain. 2009;132:2922–2931. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mackenzie IR, Foti D, Woulfe J, Hurwitz TA. Atypical frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive, TDP-43-negative neuronal inclusions. Brain. 2008;131:1282–1293. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yokota O, et al. Clinicopathological characterization of Pick’s disease versus frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin/TDP-43-positive inclusions. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:429–444. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0493-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hodges JR, et al. Clinicopathological correlates in frontotemporal dementia. Ann. Neurol. 2004;56:399–406. doi: 10.1002/ana.20203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kertesz A, McMonagle P, Blair M, Davidson W, Munoz DG. The evolution and pathology of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2005;128:1996–2005. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Knopman DS, et al. Antemortem diagnosis of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Ann. Neurol. 2005;57:480–488. doi: 10.1002/ana.20425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Josephs KA, et al. Clinicopathologic analysis of frontotemporal and corticobasal degenerations and PSP. Neurology. 2006;66:41–48. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000191307.69661.c3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Alladi S, et al. Focal cortical presentations of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2007;130:2636–2645. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Galton CJ, Patterson K, Xuereb J, Hodges JR. Atypical and typical presentations of Alzheimer’s disease: a clinical, neuropsychological, neuroimaging, and pathological study of 13 cases. Brain. 2000;123:484–498. doi: 10.1093/brain/123.3.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Knibb JA, Xuereb JH, Patterson K, Hodges JR. Clinical and pathological characterization of progressive aphasia. Ann. Neurol. 2006;59:156–165. doi: 10.1002/ana.20700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Snowden J, Neary D, Mann D. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: clinical and pathological relationships. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:31–38. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0236-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Josephs KA, Stroh A, Dugger B, Dickson DW. Evaluation of subcortical pathology and clinical correlations in FTLD-U subtypes. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;118:349–358. doi: 10.1007/s00401-009-0547-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Shi J, et al. Histopathological changes underlying frontotemporal lobar degeneration with clinicopathological correlation. Acta Neuropathol. 2005;110:501–512. doi: 10.1007/s00401-005-1079-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Grossman M, et al. TDP-43 pathologic lesions and clinical phenotype in frontotemporal lobar degeneration with ubiquitin-positive inclusions. Arch. Neurol. 2007;64:1449–1454. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.10.1449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Davies RR, et al. The pathological basis of semantic dementia. Brain. 2005;128:1984–1995. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Josephs KA, et al. Progressive aphasia secondary to Alzheimer disease vs FTLD pathology. Neurology. 2008;70:25–34. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000287073.12737.35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Grossman M, et al. Distinct antemortem profiles in patients with pathologically defined frontotemporal dementia. Arch. Neurol. 2007;64:1601–1609. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.11.1601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rascovsky K, et al. Cognitive profiles differ in autopsy-confirmed frontotemporal dementia and AD. Neurology. 2002;58:1801–1808. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.12.1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rohrer JD, et al. Patterns of cortical thinning in the language variants of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2009;72:1562–1569. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181a4124e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nestor PJ, et al. Nuclear imaging can predict pathologic diagnosis in progressive nonfluent aphasia. Neurology. 2007;68:238–239. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000251309.54320.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Mummery CJ, et al. A voxel-based morphometry study of semantic dementia: relationship between temporal lobe atrophy and semantic memory. Ann. Neurol. 2000;47:36–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Avants B, Anderson C, Grossman M, Gee JC. Spatiotemporal normalization for longitudinal analysis of gray matter atrophy in frontotemporal dementia. Med. Image Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv. Int. Conf. Med. Image. Comput. Comput. Assist. Interv. 2007;10:303–310. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75759-7_37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Klunk WE, et al. Imaging brain amyloid in Alzheimer’s disease with Pittsburgh Compound-B. Ann. Neurol. 2004;55:306–319. doi: 10.1002/ana.20009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rabinovici GD, et al. 11C-PIB PET imaging in Alzheimer disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2007;68:1205–1212. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000259035.98480.ed. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Rabinovici GD, et al. Abeta amyloid and glucose metabolism in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann. Neurol. 2008;64:388–401. doi: 10.1002/ana.21451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Munoz D, Woulfe J, Kertesz A. Argyrophilic thorny astrocyte clusters in association with Alzheimer’s disease pathology in possible primary progressive aphasia. Acta Neuropathol. 2007;114:347–357. doi: 10.1007/s00401-007-0266-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hu WT, et al. Multi-modal biomarker for Alzheimer’s disease in non-fluent primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. (in press) [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chow TW, Miller BL, Hayashi VN, Geschwind DH. Inheritance of frontotemporal dementia. Arch. Neurol. 1999;56:817–822. doi: 10.1001/archneur.56.7.817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Seelaar H, et al. Distinct genetic forms of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2008;71:1220–1226. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000319702.37497.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Snowden JS, et al. Progranulin gene mutations associated with frontotemporal dementia and progressive non-fluent aphasia. Brain. 2006;129:3091–3102. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Mesulam M, et al. Progranulin mutations in primary progressive aphasia: The PPA1 and PPA3 families. Arch. Neurol. 2007;64:43–47. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Beck J, et al. A distinct clinical, neuropsychological and radiological phenotype is associated with progranulin gene mutations in a large UK series. Brain. 2008;131:706–720. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Rademakers R, et al. Phenotypic variability associated with progranulin haploinsufficiency in patients with the common 1477C→T (Arg493X) mutation: an international initiative. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6:857–868. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(07)70221-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Le Ber I, et al. Phenotype variability in progranulin mutation carriers: a clinical, neuropsychological, imaging and genetic study. Brain. 2008;131:732–746. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Leverenz JB, et al. A novel progranulin mutation associated with variable clinical presentation and tau, TDP43 and alpha-synuclein pathology. Brain. 2007;130:1360–1374. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bird TD, et al. A clinical pathological comparison of three families with frontotemporal dementia and identical mutations in the tau gene (P301L) Brain. 1999;122:741–756. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.4.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Pickering-Brown SM, et al. Frequency and clinical characteristics of progranulin mutation carriers in the Manchester frontotemporal lobar degeneration cohort: comparison with patients with MAPT and no known mutations. Brain. 2008;131:721–731. doi: 10.1093/brain/awm331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Li X, et al. Prion protein codon 129 genotype prevalence is altered in primary progressive aphasia. Ann. Neurol. 2005;58:858–864. doi: 10.1002/ana.20646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sobrido MJ, et al. Possible association of the tau H1/H1 genotype with primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 2003;60:862–864. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000049473.36612.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mesulam MM, Johnson N, Grujic Z, Weintraub S. Apolipoprotein E genotypes in primary progressive aphasia. Neurology. 1997;49:51–55. doi: 10.1212/wnl.49.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Foulds P, et al. TDP-43 protein in plasma may index TDP-43 brain pathology in Alzheimer’s disease and frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;116:141–146. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0389-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Sleegers K, et al. Serum biomarker for progranulin-associated frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Ann. Neurol. 2009;65:603–609. doi: 10.1002/ana.21621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Finch N, et al. Plasma progranulin levels predict progranulin mutation status in frontotemporal dementia patients and asymptomatic family members. Brain. 2009;132:583–591. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Ghidoni R, Benussi L, Glionna M, Franzoni M, Binetti G. Low plasma progranulin levels predict progranulin mutations in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2008;71:1235–1239. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000325058.10218.fc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Grossman M, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid profile distinguishes frontotemporal dementia from Alzheimer’s disease. Ann. Neurol. 2005;57:721–729. doi: 10.1002/ana.20477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Arai H, et al. Cerebrospinal fluid tau levels in neurodegenerative diseases with distinct tau-related pathology. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997;236:262–264. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.6908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Green AJ, Harvey RJ, Thompson EJ, Rossor MN. Increased tau in the cerebrospinal fluid of patients with frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Neurosci. Lett. 1999;259:133–135. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(98)00904-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Riemenschneider M, et al. Tau and Aβ42 protein in CSF of patients with frontotemporal degeneration. Neurology. 2002;58:1622–1628. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.11.1622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Pijnenburg YA, et al. CSF tau and Aβ42 are not useful in the diagnosis of frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neurology. 2004;62:1649. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000123014.03499.a7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Bian H, et al. CSF biomarkers in frontotemporal lobar degeneration with known pathology. Neurology. 2008;70:1827–1835. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000311445.21321.fc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Borroni B, et al. Tau forms in CSF as a reliable biomarker for progressive supranuclear palsy. Neurology. 2008;71:1796–1803. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000335941.68602.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Urakami K, et al. Diagnostic significance of tau protein in cerebrospinal fluid from patients with corticobasal degeneration or progressive supranuclear palsy. J. Neurol. Sci. 2001;183:95–98. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(00)00480-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Steinacker P, et al. TDP-43 in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with frontotemporal lobar degeneration and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Arch. Neurol. 2008;65:1481–1487. doi: 10.1001/archneur.65.11.1481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Kasai T, et al. Increased TDP-43 protein in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2009;117:55–62. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0456-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Ruetschi U, et al. Identification of CSF biomarkers for frontotemporal dementia using SELDI-TOF. Exp. Neurol. 2005;196:273–281. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Simonsen AH, et al. A novel panel of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for the differential diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease versus normal aging and frontotemporal dementia. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2007;24:434–440. doi: 10.1159/000110576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Ratnavalli E, Brayne C, Dawson K, Hodges JR. The prevalence of frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2002;58:1615–1621. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.11.1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Harvey RJ, Skelton-Robinson M, Rossor MN. The prevalence and causes of dementia in people under the age of 65 years. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2003;74:1206–1209. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.9.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Ikejima C, et al. Prevalence and causes of early-onset dementia in Japan: A population-based study. Stroke. 2009;40:2709–2714. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.108.542308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Knopman DS, Petersen RC, Edland SD, Cha RH, Rocca WA. The incidence of frontotemporal lobar degeneration in Rochester, Minnesota, 1990 through 1994. Neurology. 2004;62:506–508. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000106827.39764.7e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Mercy L, Hodges JR, Dawson K, Barker RA, Brayne C. Incidence of early-onset dementias in Cambridgeshire, United Kingdom. Neurology. 2008;71:1496–1499. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000334277.16896.fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Johnson JK, et al. Frontotemporal lobar degeneration: demographic characteristics of 353 patients. Arch. Neurol. 2005;62:925–930. doi: 10.1001/archneur.62.6.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Roberson ED, et al. Frontotemporal dementia progresses to death faster than Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;65:719–725. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000173837.82820.9f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Rascovsky K, et al. Rate of progression differs in frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2005;65:397–403. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000171343.43314.6e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Hodges JR, Davies R, Xuereb J, Kril J, Halliday G. Survival in frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2003;61:349–354. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000078928.20107.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Josephs KA, et al. Survival in two variants of tau-negative frontotemporal lobar degeneration: FTLD-U vs FTLD-MND. Neurology. 2005;65:645–647. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000173178.67986.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Xie SX, et al. Factors associated with survival probability in autopsy-proven frontotemporal lobar degeneration. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2008;79:126–129. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.110288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Rosso SM, et al. Medical and environmental risk factors for sporadic frontotemporal dementia: a retrospective case–control study. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2003;74:1574–1576. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.74.11.1574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Rogalski E, Johnson N, Weintraub S, Mesulam M. Increased frequency of learning disability in patients With primary progressive aphasia and their first-degree relatives. Arch. Neurol. 2008;65:244–248. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2007.34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Alberca R, Montes E, Russell E, Gil-Néciga E, Mesulam M. Left hemicranial hypoplasia in 2 patients with primary progressive aphasia. Arch. Neurol. 2004;61:265–268. doi: 10.1001/archneur.61.2.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Hickok G, Poeppel D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2007;8:393–402. doi: 10.1038/nrn2113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Indefrey P, Levelt WJ. The spatial and temporal signatures of word production components. Cognition. 2004;92:101–144. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2002.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Das SR, Avants B, Grossman M, Gee JC. Registration-based cortical thickness measurement. Neuroimage. 2009;45:867–879. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]