INTRODUCTION

The human immune system relies on a complex system of defense mechanisms to protect the body from infection.1 This system consists of such cells as macrophages, dendritic cells, and natural killer (NK) lymphocytes to identify pathogens.1

Under optimal circumstances, recognition of virulent pathogens prompts destruction of the pathogens by macrophages or NK cells or activation of a series of events to slow progression of infection. In addition, the adaptive immune system is activated.1 Adaptive immunity is based on the generation of antigen receptors on T-and B-lymphocytes.1 These lymphocytes express unique antigen receptors and have the ability to specifically identify diverse foreign antigens produced by the wide variety of pathogens. In addition, T-and B-lymphocytes have mechanisms to ensure nonreactivity to self antigens, and they contribute both specificity and immune memory to defend against pathogens.1 Though their exact cause is unknown, a number of diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), ankylosing spondylitis (AS), and psoriatic arthritis (PsA), are thought to occur when the immune system attacks normal, healthy tissues in the body, causing inflammation and, over time, damage.1

This Product Profiler reviews the evidence-based literature supporting the U.S. Food and Drug Administration-approved indications of SIMPONITM (golimumab) for the treatment of moderately to severely active RA, active AS, and active PsA.

DISEASE BACKGROUND

Rheumatoid Arthritis

RA is a chronic, multisystem disease characterized by persistent inflammatory synovitis that usually affects peripheral joints in symmetric distribution.1 Synovial inflammation damages cartilage and causes bone erosion, which can result in diminished joint integrity. RA is estimated to affect approximately 1.3 million adults in the United States.2 The prevalence of RA is approximately 2–3 times higher in women and increases with age,1–2 with 80% of all patients developing RA between the ages of 35 and 50.1

The etiology of RA is not clearly understood, although current research suggests that it may be a response to an infectious agent in a genetically susceptible host.1 Micro vascular injury and increased production of synovial lining cells are thought to be the earliest clinical changes that affect the rheumatoid synovitis, followed by perivascular infiltration of mononuclear cells, which are predominantly myeloid cells before the onset of clinical symptoms. Symptoms are accompanied by the presence of T cells, and the synovium swells and protrudes into the joint space as the disease progresses1 (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Hand Affected by Rheumatoid Arthritis

Copyright © Bart's Medical Library/Phototake Plus

Clinical manifestations of articular disease include pain in affected joints that may be greatest after periods of inactivity.1 Extra-articular manifestations, including rheumatoid nodules, eye disease, and cardiopulmonary disease may occur. Although RA is a chronic condition, some affected individuals may experience fluctuations in disease activity, including intervals of remission.1

RA is a cause of functional disability.3,4 A 12-year, longitudinal study of 1,274 patients with RA revealed significant declines in functional ability. Fifty percent of patients with RA had functional disability scores indicative of moderate, severe, and very severe loss of functional abilities in 2, 6, and 10 years, respectively.3

This disease also imposes a significant economic burden relative to other chronic conditions, such as osteoarthritis (OA) and hypertension (HTN). A cost-of-illness study estimated annual direct medical costs in 2000 at $9,300 for RA, compared with $5,700 for OA and $3,900 for HTN.5 In this study, indirect costs associated with RA increased 5-fold relative to costs incurred by patients with OA, HTN, or both conditions.5

Drug therapy options. The use of biologic diseasemodifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) has become more frequent in the treatment for RA, either as singleagent therapy or in combination with nonbiologic DMARDs.6 Multiple randomized, controlled trials have demonstrated that biologic tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) inhibitors are effective in patients with RA when used alone,7–9,19,37 in combination with methotrexate,10–17,31,33,37–39 or in combination with other DMARDs.18,32 The primary endpoint of interest in the majority of these trials has been a 20% improvement according to the American College of Rheumatology criteria (ACR20).8,11–13,17

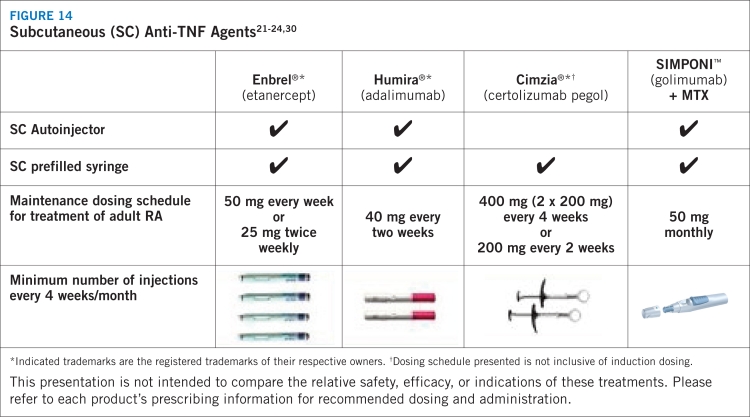

Clinical challenges related to rheumatologic disease management persist, however. Because the clinical presentation can vary, treatment must be tailored to the individual, taking into account such factors as the severity of arthritis and individual lifestyles.20 Moreover, current anti-TNF-α therapies differ in their affinity, stability, terminal half-life characteristics, route of administration, and frequency of dosing.21–24,30

Ankylosing Spondylitis

AS is an inflammatory disease with typical diagnosis occurring between ages 15 and 35.25 Current estimates suggest that 350,000 to 1 million Americans are affected by AS.25,26 The male-to-female prevalence is estimated to be up to 3 to 1.1 Current evidence suggests that genetic factors are the primary cause of susceptibility to AS.1 The pathogenesis of AS is not yet well understood, but it is considered to be an immune-mediated disease with a key role played by TNF-α.25

AS most frequently affects the axial skeleton, and initial symptoms include dull, insidious pain affecting the lower lumbar or gluteal areas as well as early morning stiffness in the lower back that can persist for several hours.1 AS also affects peripheral joints and extra-articular structures, with 25% to 35% of patients experiencing arthritis in the hips and shoulders and up to 30% affected by arthritis in other joints.1 Other symptoms include neck pain and stiffness.1

The clinical course of AS is variable with patients experiencing exacerbations of symptoms followed by periods of remission.1 Disease progression is characterized by formation of syndesmophytes; postural changes, including lumbar or thoracic curvature; buttock atrophy; a forward stoop of the neck; or flexion contractures at the hips.1

Psoriatic Arthritis

PsA is a chronic inflammatory arthritis that commonly affects individuals with plaque psoriasis, with prevalence estimated at about 11 percent in people with active psoriasis.1,27 PsA also is considered to be an immune-mediated inflammatory disease characterized by penetration of the PsA synovium with T cells, B cells, macrophages, and upregulation of leukocyte homing receptors.1 Some 60% to 70% of cases of PsA are preceded by development of psoriasis, with the onset of symptoms most frequently observed in individuals in their 30s and 40s.1 Patients report pain, stiffness, and swelling in and around the joints.28

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

RA is an inflammatory condition that involves infiltration of the synovium primarily by CD4+ T cells, monocytes, and macrophages to produce multiple cytokines, including IL-1, IL-6, and TNF-α.29 These are considered to be key cytokines that provoke the inflammatory responses observed in patients with RA.29 CD4+ T cells also prompt the production of B cells that are responsible for the production of immunoglobulins, including rheumatoid factor.29 TNF-α and IL-1 are stimulators of mesenchymal cells, which include synovial fibroblasts, osteoclasts, and chondrocytes. All of these contribute to the release of matrix metalloproteinases, which destroy tissue. IL-1 and TNF-α also inhibit the production of tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases by synovial fibroblasts.29 It has been suggested that the combined effects of these processes cause joint damage over time. TNF-α also is known to provoke development of osteoclasts, which are destructive to bone.29

TNF-α is produced by the combined efforts of immune cells, including monocytes, macrophages, and T cells. TNF-α is a leading contributor to inflammatory reactions because of its effects as an autocrine stimulator and paracrine inducer of other inflammatory cytokines, including IL-1, IL-6, IL-8, and granulocyte-monocyte colony-stimulating factor. TNF-α also provokes inflammatory reactions through promotion of fibroblasts that express adhesion molecules, which interact with ligands on the surface of leukocytes. These interactions increase the transport of leukocytes to sites of inflammation, such as joints in patients with RA.29

This description of the inflammatory process identifies key factors that contribute to the pathophysiology and progression of RA. In particular, TNF-α has been identified as an important target for pharmacologic therapy for RA.

References

- 1.Fauci AS, Braunwald E, Kasper DL, et al., editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 17th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:15–25. doi: 10.1002/art.23177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolfe F, Cathey MA. The assessment and prediction of functional disability in rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol. 1991;18:1298–1306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pincus T, Callahan LF. Reassessment of twelve traditional paradigms concerning the diagnosis, prevalence, morbidity, and mortality of rheumatoid arthritis. Scand J Rheumatol Suppl. 1989;79:67–95. doi: 10.3109/03009748909092614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Maetzel A, Li LC, Pencharz J, et al. The economic burden associated with osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and hypertension: a comparative study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63:395–401. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.006031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saag KG, Teng GG, Patkar NM, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2008 recommendations for the use of nonbiologic and biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:762–784. doi: 10.1002/art.23721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van de Putte LBA, Rau R, Breedveld FC, et al. Efficacy and safety of the fully human anti-tumour necrosis factor α monoclonal antibody adalimumab (D2E7) in DMARD refractory patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a 12 week, phase II study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62:1168–1177. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.009563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moreland LW, Schiff MH, Baumgartner SW, et al. Etanercept therapy in rheumatoid arthritis: A randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:478–486. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bathon JM, Martin RW, Fleischmann RM, et al. A comparison of etanercept and methotrexate in patient with early rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1586–1593. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klareskog L, van der Heijde D, et al. Therapeutic effect of the combination of etanercept and methotrexate compared with each treatment alone in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: double-blind randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;363:675–681. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15640-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weinblatt ME, Keystone EC, Furst DE, et al. Adalimumab, a fully human anti-tumor necrosis factor alpha monoclonal antibody, for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis in patients taking concomitant methotrexate: the ARMADA trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2003;48:35–45. doi: 10.1002/art.10697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Keystone EC, Kavanaugh AF, Sharp JT, et al. Radiographic, clinical, and functional outcomes of treatment with adalimumab (a human anti-tumor necrosis factor monoclonal antibody) in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis receiving concomitant methotrexate: a randomized, placebo-controlled, 52-week trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1400–1411. doi: 10.1002/art.20217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maini R, St Clair EW, Breedveld F, et al. Infliximab (chimeric anti-tumor necrosis alpha factor monoclonal antibody) versus placebo in rheumatoid arthritis patients receiving concomitant methotrexate: a randomized phase III trial. ATTRACT Study Group. Lancet. 1999;354:1932–1939. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)05246-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lipsky PE, van der Heijde DM, St Clair EW, et al. Infliximab and methotrexate in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Anti-Tumor Necrosis Factor Trial in Rheumatoid Arthritis with Concomitant Therapy Study Group. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1594–1602. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011303432202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maini RN, Breedveld FC, Kalden JR, et al. Sustained improvement over two years in physical function, structural damage, and signs and symptoms among patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab and methotrexate. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:1051–1065. doi: 10.1002/art.20159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.St Clair EW, van der Heijde DM, Smolen JS, et al. Combination of infliximab and methotrexate therapy for early rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3432–3443. doi: 10.1002/art.20568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weinblatt ME, Kremer JM, Bankhurst AD, et al. A trial of etanercept, a recombinant tumor necrosis factor receptor:Fc fusion protein, in patients with rheumatoid arthritis receiving methotrexate. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:253–259. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901283400401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Furst DE, Schiff MH, Fleischmann RM, et al. Adalimumab, a fully anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha monoclonal antibody, and concomitant standard antirheumatic therapy for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis: results of STAR (Safety Trial of Adalimumab in Rheumatoid Arthritis) J Rheumatol. 2003;30:2563–2571. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fleischmann R, Vencovsky J, van Vollenhoven RF, et al. Efficacy and safety of certolizumab monotherapy every 4 weeks in patients with rheumatoid arthritis failing previous disease-modifying antirheumatic therapy: the FAST4WARD study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:805–811. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.099291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arthritis Foundation. Rheumatoid arthritisAvailable at: «http://www.arthritis.org/http_id=31&df=treatments». Accessed July 24, 2009.

- 21.Thousand Oaks, Calif.: Immunex Corp.; Enbrel (etanercept) [prescribing information] [Google Scholar]

- 22.North Chicago, Ill.: Abbott Laboratories; Humira (adalimumab) [prescribing information] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Malvern, Pa.: Centocor, Inc.; Remicade (infliximab) [prescribing information] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Smyrna, Ga.: UCB Pharma; Cimzia (certolizumab pegol) [prescribing information] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Davis JC., Jr Understanding the role of tumor necrosis factor inhibition in ankylosing spondylitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2005;34:668–677. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2004.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newman PA, Bruckel JC. Spondylitis association of America: the member-directed, nonprofit health organization addressing the needs of ankylosing spondylitis patients. Rheum Dis Clin North Am. 2003;29:561–574. doi: 10.1016/s0889-857x(03)00046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gelfand JM, Gladman DD, Mease PJ, et al. Epidemiology of psoriatic arthritis in the population of the United States. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;53:573–577. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.03.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.National Psoriasis Foundation Psoriatic arthritisAvailable at: «http://www.psoriasis.org/about/psa». Accessed July 24, 2009.

- 29.Choy EHS, Panayi GS. Cytokine pathways and joint inflammation in rheumatoid arthritis. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:907–916. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200103223441207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

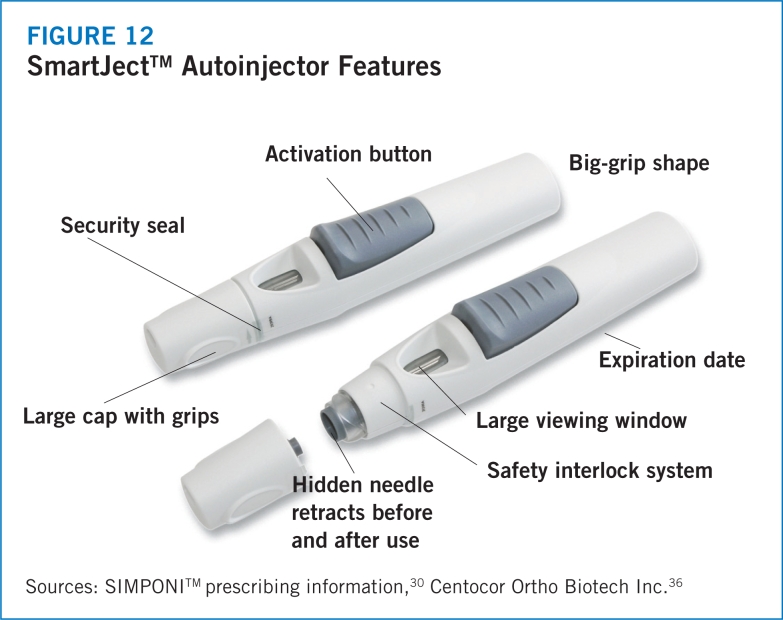

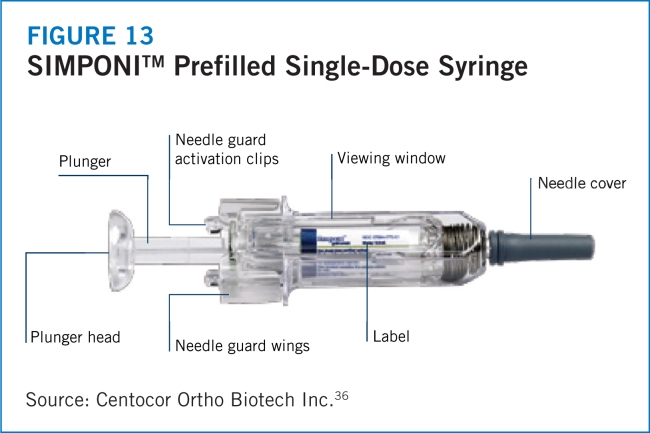

- 30.Malvern, Pa.: Centocor Ortho Biotech Inc.; SIMPONITM (golimumab) [prescribing information] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keystone EC, Genovese MC, Klareskog L, et al. Golimumab, a human antibody to tumour necrosis factor α given by monthly subcutaneous injections, in active rheumatoid arthritis despite methotrexate: The GO-FORWARD study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:789–796. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.099010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smolen JS, Kay J, Doyle MK, et al. Golimumab in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis after treatment with tumour necrosis factor α inhibitors (GO-AFTER study): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase III trial. Lancet. 2009;374:210–221. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60506-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Emery P, Fleischmann RM, Moreland LW, et al. Golimumab, a human anti-tumor necrosis factor α monoclonal antibody, injected subcutaneously every four weeks in methotrexatenaïve patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:2272–2283. doi: 10.1002/art.24638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kavanaugh A, McInnes I, Mease P, et al. Golimumab, a new human tumor necrosis factor antibody, administered every four weeks as a subcutaneous injection in psoriatic arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2009;60:976–986. doi: 10.1002/art.24403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

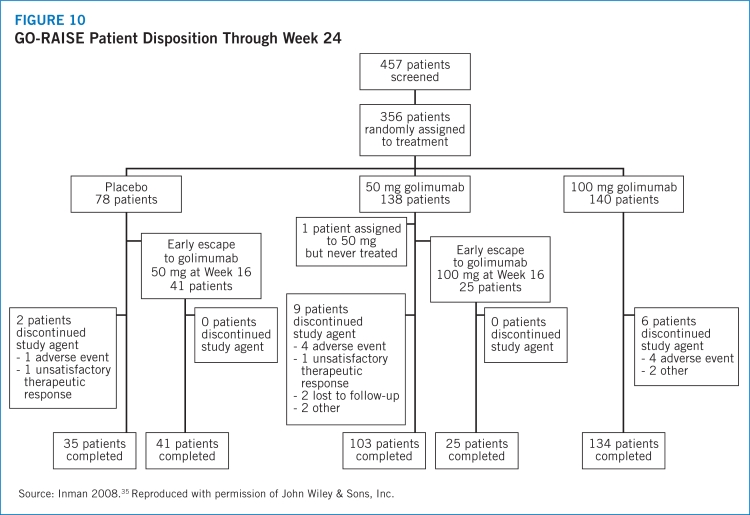

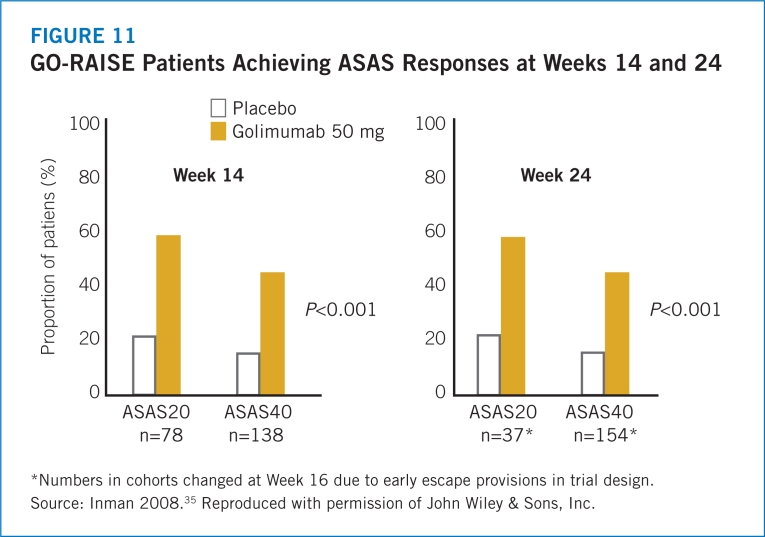

- 35.Inman RD, Davis JC, van der Heijde D, et al. Efficacy and safety of golimumab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3402–3412. doi: 10.1002/art.23969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Data on file. Centocor Ortho Biotech Inc.

- 37.Keystone E, Heijde D, Mason D, Jr, et al. Certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate is significantly more effective than placebo plus methotrexate in active rheumatoid arthritis: findings of a fifty-two-week, phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3319–3329. doi: 10.1002/art.23964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smolen J, Landewé RB, Mease P, et al. Efficacy and safety of certolizumab pegol plus methotrexate in active rheumatoid arthritis: the RAPID 2 study. A randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2009;68:797–804. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.101659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Breedveld FC, Weisman MH, Kavanaugh AF, et al. The PREMIER study: A multicenter, randomized, double-blind clinical trial of combination therapy with adalimumab plus methotrexate versus methotrexate alone or adalimumab alone in patients with early, aggressive rheumatoid arthritis who had not had previous methotrexate treatment. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:26–37. doi: 10.1002/art.21519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]