Abstract

Introduction

Chemotherapy is administered only to patients with advanced cancers, typically to modest avail. Hence, the search for innovative approaches to treat cancer is growing rapidly. One such approach involves targeting molecular pathways identified as encouraging tumor growth and maintenance, particularly the type 1 insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) and its receptor (IGF-1R) pathway that is important in conferring chemoresistance.

Materials and Methods

This study focuses on IGF-1R targeted therapy, which will enhance chemotherapy efficacy, through reviewing recent literature from PubMed and Medline databases.

Conclusion

This review examines data and strategies addressing an approach conquering chemoresistance through the combination of IGF-1R targeted therapy and chemotherapy in cancer patients, as well as the mechanisms by which IGF-1R acts as a target. This will impact on future research on treatment selection, thereby improving patient prognosis.

Keywords: IGF-1R targeted therapy, Chemotherapy, Chemoresistance, Combination cancer therapy

Introduction

The introduction of adjuvant therapy has seen vastly improved survival rates in both mesenchymal and epithelial cancers. Of particular interest is chemotherapy, often in combination with surgery, which generally eradicates any cells that are proliferating abnormally in the primary site or metastatic areas. Malignant cells within a tumor mass are distinctly heterogeneous in terms of genetic abnormalities. Consequently, some cells may be resistant to treatment, while others may acquire resistance to chemotherapy after initiation. The typical result is that these cells survive treatment and proliferate as a more aggressive tumor. Furthermore, there are limited chemotherapeutic options, particularly if treatment with doxorubicin and ifosfamide fail, for example, the response rate in sarcomas is 35% (Kasper et al. 2007; Von Mehren 2003; Clark et al. 2005). Treatment is further complicated by side effects such as myelosuppression, cardiotoxicity, neurotoxicity and nephrotoxicity. Hence, it can be said that a new approach is required for tackling these issues. The recent shift away from broad-spectrum chemotherapy to molecular targeted therapy has been seen in the treatment of all cancers, including breast, lung, prostate, pancreatic, bowel carcinomas and sarcomas (Hewish et al. 2009; Kasper et al. 2007).

Targeted therapy aimed at the growth-factor signaling pathways has recently become an area of interest for oncology. High specificity towards tumor cell signaling pathways means that targeted therapy is able to provide a broader therapeutic window with less toxicity to normal cells than traditional therapies (Arora and Scholar 2005; Yang and Crowe 2007). However, primary tumor insensitivity and acquired resistance to therapy must also be addressed (Bohula et al. 2003).

The IGF-1/IGF-1R pathway has shown to be a promising target for anti-cancer therapy, with data suggesting that the IGF-1R is an important factor for tumor progression and protection from apoptosis. Blockade of this receptor through specific drug mono-therapy has shown modest improvements, though not enough to out-weigh the benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy. The combination of chemotherapy and IGF-1R targeted therapy has proved effective in some forms of sarcoma, particularly Ewing’s sarcoma (Scotlandi 2006) as well as breast cancer (Gooch et al. 1999), and hepatocellular carcinoma (Lee et al. 2007). Further exploration of combination therapy should be undertaken to optimize its application and address chemoresistance (Huang et al. 2009; Lambert et al. 2008; Tanaka and Arii 2009). Furthermore, through understanding the mechanisms of action, further therapeutic targets may be discovered, as well as biomarkers to monitor treatment.

This review aims to explore the research conducted on (1) chemotherapy in the treatment of cancer, (2) IGF-1/IGF-1R signaling, (3) IGF-1R and chemoresistance, (4) IGF-1R targeted therapy, and (5) combination therapy using IGF-1R blocking approach with chemotherapy.

Current chemotherapy approach to cancer

Current treatment for cancer involves surgical excision of the tumor often combined with adjuvant therapy. This review focuses on chemotherapy, consequently radiotherapy will not be discussed. The use of chemotherapy has significantly improved local and metastatic control of cancer. As optimal resection with acceptable margins is often difficult to achieve in the pelvis, head, neck, base of skull and the axial skeleton, pre-operative and post-operative chemotherapy in combination with surgery offers the best prognosis for patients. Moreover, for inoperable metastatic cancer, palliative chemotherapy is currently the only option. However, prognosis remains poor for most forms of cancer, such as pancreatic cancer, or more progressive/metastatic cancers, as chemotherapy only provides for a narrow therapeutic window in chemoresistant tumors. The causes of chemoresistance will be discussed later.

Chemotherapy has become standard protocol for treating many cancers, particularly those that have metastasised. Numerous studies have demonstrated modest improvements when treated with doxorubicin and ifosfamide, however, these treatments are associated with substantial toxic effects, particularly for older patients with co-morbidities (Wunder et al. 2007). Moreover, toxicity increases substantially with increasing doses, while response rates improve only slightly. With current standards of treatment, the overall 5-year survival rate for all stages of sarcoma is 50–60% (Kasper et al. 2007), for stage IV breast cancer is 28% (Jemal et al. 2006), for lung cancer is 15%, and for hepatocellular carcinoma is 11% (Garcia et al. 2007).

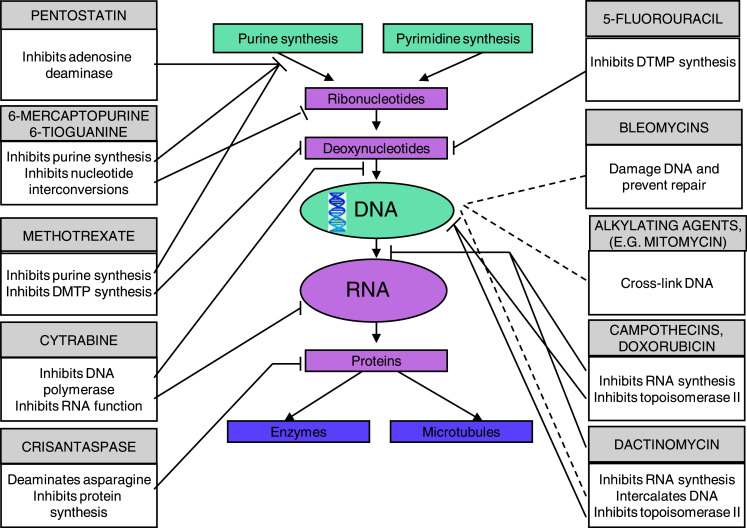

Chemotherapy drugs target tumor cells in different ways, however, the overall effect is cell-cycle arrest and/or induction of apoptosis/cytotoxicity. The mechanisms of action of some commonly prescribed chemotherapy drugs are represented diagrammatically (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mechanisms of action for chemotherapeutic drugs. Illustrates how each class of chemotherapeutic drugs interact with cell function. The lines indicate which section of the cell process each chemotherapeutic is having its effect

These drugs have proven somewhat effective, however, chemoresistance continues to decrease therapy efficacy, and increase the requirement for improved treatment. Resistance to cytotoxic drugs is said to be ‘primary’ if present when the drug is first administered, or ‘acquired’ if resistance develops during treatment.

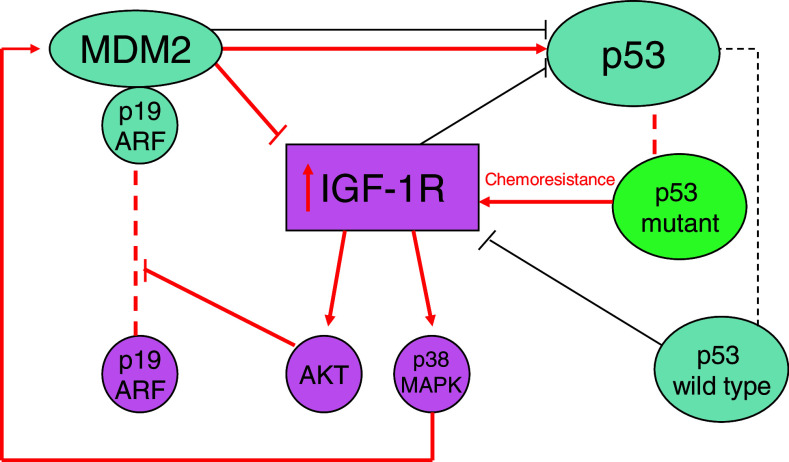

The apparent correlation between IGF-1R expression and cancer has led to the study of a variety of strategies to utilise this pathway in cancer therapy. Of particular interest is the role of the p53 gene in tumor growth and metastasis. More than 50% of human tumors carry a mutation of the p53 gene, which has given rise to research into anti-sense oligonucleotides. The wild-type p53 is capable of suppressing the IGF-1R promoter activity, as well as lowering the endogenous levels of IGF-1R mRNA (Werner and Le Roith 2000). Data suggests that up-regulation of IGF-1R due to loss of function of p53 may facilitate selection of a malignant population of cells. There exists a p53/IGF-1R/MDM2 axis, where changes leading to increased distribution of MDM2 to the cell nucleus to deactivate p53, may contribute to tumorigenesis through up-regulation of IGF-1R (Larrson et al. 2005) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

The interplay between p53, MDM2 and IGF-1R. MDM2 can decrease p53 synthesis, but also associate to it causing upregulation of p53. p19 ARF association to MDM2 prevents association to p53. The path taken when chemoresistant p53 mutant is present, is shown in thickened (red) arrows where IGF-1R is upregulated

Mechanisms of resistance, such as this, offer new problems to overcome, and should be addressed through novel approaches. In particular, the IGF system has been implicated in affecting the clinical course of malignancies, through promoting tumor progression and the acquisition of an aggressive phenotype. It also offers escape mechanisms that allow the tumor to evade conventional treatment (Samani et al. 2007). Studies propose that the IGF-1R may also play a role in protection of tumor cells from DNA-damaging agents such as chemotherapy, and ionizing radiation (Gil-Ad et al. 1999; Gooch et al. 1999; Jiang et al. 1999; Kuhn et al. 1999; Liu et al. 1998b; Peters et al. 1996). The benefits of IGF-1R blockade in combination with radiotherapy have been widely documented (Criswell et al. 2005), however, the focus of this review is the effect of blocking IGF-1R on chemotherapy.

IGF-1/IGF-1R signaling

Targeting the IGF/IGF-1R signaling pathway represents a potential strategy for the development of effective anti-cancer therapeutics. Importantly, the IGF system including ligands, receptors and binding proteins is present in almost all malignancies (Hartog et al. 2007). The IGF-1R is over-expressed in many tumors and mediates proliferation, motility and apoptosis protection (Sell et al. 1993). Indeed, forced over-expression of the IGF-1R increases the development of tumors in preclinical models (Carboni et al. 2005; Lopez and Hanahan 2002). Furthermore, inhibition of IGF-1R expression or function has shown a promising target for reducing tumor growth and metastasis (Macaulay 2004; Yakar et al. 2005).

Blockade of the IGF system signaling has the potential for many clinical uses, including increasing the proportion, extent and duration of clinical responses to cytotoxic therapies when used in combination. For example, in the treatment of breast cancer, patients with tumors expressing IGF-1R are much less likely to respond to neoadjuvant therapies, including hormonal therapies such as tamoxifen and herceptin, than non-IGF-1R expressing tumors (Harris et al. 2007). Therefore, pathological typing of cancer tissues prior to treatment could offer more effective treatment and thus, better prognosis.

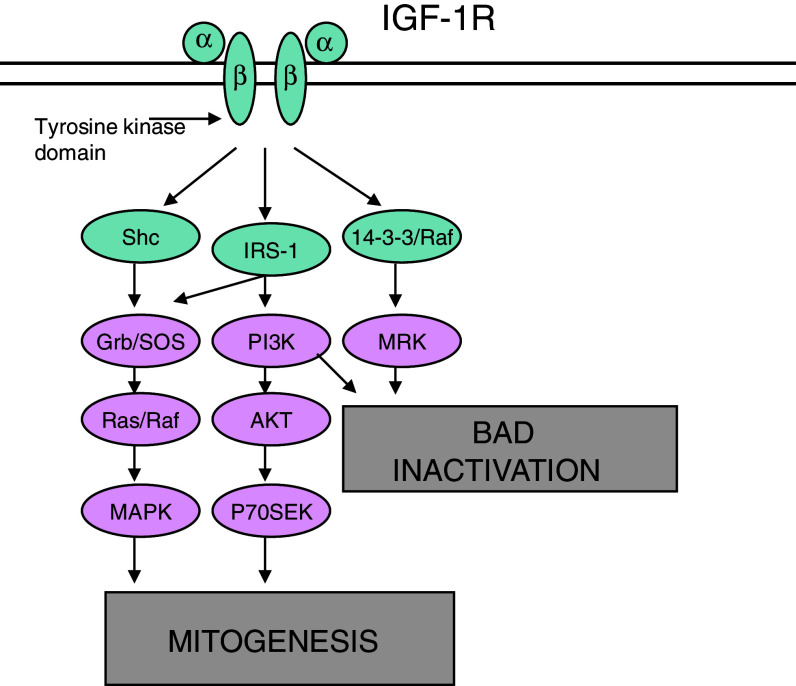

IGF-1 is secreted primarily by the liver and smooth muscle in response to stimulation by growth hormone. In the case of malignancy, tumor cells secrete a large amount of IGFs which can be measured in the circulation. IGF-1 activates the IGF-1R and is normally a self-regulated cycle in which IGF-2 and IGF binding proteins regulate IGF-1 secretion through negative feedback. The IGF-1R is a transmembrane tyrosine kinase, consisting of two extracellular α-subunits, and two intracellular β-subunits. The α-subunits bind ligands IGF-I and IGF-II, while the β-subunits transmit ligand-induced signals. Such ligands are produced by tumors in a paracrine and/or autocrine manner (Busund et al. 2004).

The IGF-1R and the insulin receptor are highly homologous, especially in the tyrosine kinase domain (TKD), in which the share 84% of amino acid identities. Despite similarities, the receptors have vastly different functions. The insulin receptor plays a vital role in glucose homeostasis, while the IGF-1R is involved in regulation of cell proliferation, differentiation, protection from apoptosis and cell motility (Larrson et al. 2005). Studies have demonstrated some side-effects, the most widely debated being the occurrence of hyperglycemia. The mechanism of the hyperglycaemic effects of IGF-1R targeted monoclonal antibodies is unclear, but may be due to the neoglycogenic effects of human growth hormone, which are upregulated in IGF-1R inhibition (Tolcher et al. 2007). Moreover, hyperglycemia may result from inhibition of the hypoglycaemic effects of IGF-1. The majority of these hyperglycaemic events have been mild and reversible. In fact, data suggests that increased insulin secretion compensates for the insulin resistance and increased glucose production in most cases (Lacy et al. 2008; Weroha and Haluska 2008). Accordingly, severe hyperglycemia is rare, with the exception of cases involving chemotherapy requiring pre-treatment with steroids. In these cases, up to 20% of patients experienced hyperglycemia, possibly due to the fact that steroids are themselves strong hyperglycaemic agents (Karp et al. 2009). However, a recent study revealed that when CP-751,871 was combined with high doses of steroids in patients with multiple myeloma, severe hyperglycemia was not observed, possibly due to interference with the growth hormone—IGF-1 axis (Hochberg 2002).

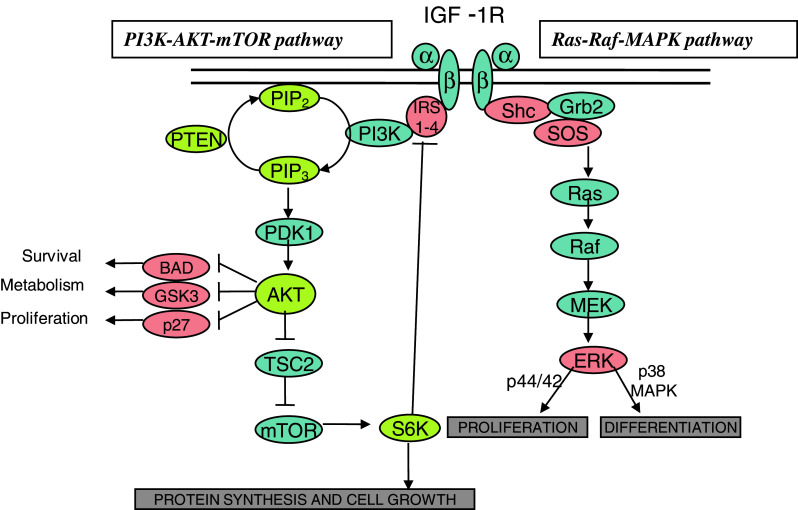

The interaction of ligand and receptor causes phosphorylation of the TKD, leading to phosphorylation of intracellular proteins—the Src-and collagen-homology (SHC) protein, and insulin receptor substrates 1–4 (IRS 1–4) (Vasilcanu et al. 2004). This activates the phosphatidyl inositol-3 kinase (PI3K), the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and the 14-3-3 pathways, all of which are important for mitogenesis, and deactivation of ‘BAD’. The PI3K and MAPK (activated by SHC), are major pathways contributing to tumorigenesis, maintenance of a phenotype, and protection from apoptosis (Xie et al. 1999; Girnita et al. 2004; Surmacz 2003).

In the PI3K pathway, binding of the p85 and p110 subunits of PI3K to IRS induces the conversion of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-biphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-biphosphate (PIP3), which activates phosphoinositide-dependent kinase-1 (PDK1). PDK1 phosphorylates the serine/threonine kinase AKT, resulting in its activation. AKT has many substrates that are inhibited or activated by its phosphorylation, such as glycogen synthase kinase-3 (GSK3), BAD, and p27. These substrates are involved in the diverse cellular functions of AKT, which include regulation of cell survival, proliferation and metabolism. Additionally, AKT activates the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) by releasing the inhibitory activity of tuberous sclerosis complex-2 (TSC2) through phosphorylation. Activated mTOR promotes protein synthesis and cell growth. Several mechanisms exist that inhibit PI3K signaling, including the phosphatase and tensin homologue (PTEN), which inhibits the formation of PIP3. Another mechanism includes the phosphorylation of serine residues on IRS-1 by S6K (Vasilcanu et al. 2004).

In the MAPK pathway, SHC, growth factor receptor-bound protein-2 (Grb2) and son of sevenless (SOS) cooperate to activate Ras. Activated Ras consequently activates the kinase activity of Raf. This protein phosphorylates the MAPK/ERK kinases (MEK1 and MEK2), which phosphorylates and activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase-1 and -2 (ERK1 and ERK2). ERK has numerous target proteins in both the cytosol and the nucleus, which regulate processes such as proliferation, survival, differentiation and migration (Figs. 3, 4).

Fig. 3.

Overview of major IGF-1R signaling pathways. Following ligand binding, the two major pathways are activated. The first is the Ras-Raf-MAPK pathway, which is involved in proliferation and differentiation of cells. The second is the PI3K-AKT-mTOR pathway, which is also involved in proliferation and cell growth, but also implicated in cell survival signals to inhibit anti-apoptotic proteins

Fig. 4.

IGF-1R pathways leading to development and maintenance of tumor cells. BAD deactivation induces anti-apoptotic protein expression, while the PI3K, MAPK and the 14-3-3 pathways all contribute to sustaining and repairing the cell through cell survival signals

Many studies have shown a correlation between IGF-1R expression and poor prognosis (Ericsson et al. 2002; Hakam et al. 1999; Turner et al. 1997), while other in vitro experiments have demonstrated that IGF-1R expression is implicated in the progression of many cancers (Djavan et al. 2001; Druckman and Rohr 2002; Giovannucci 2001; Korc 1998; Pollak 2000; Sachdev and Yee 2001; Scharf et al. 2001; Surmacz 2000). Apart from these, IGF-1R inhibition has been studied for its utility in addressing chemoresistance in many cancers, particularly sarcoma, breast, lung, melanoma and prostate (Burfeind et al. 1996; Chernicky et al. 2000; Lee et al. 1996; Liu et al. 1998a; Maloney et al. 2003; Resnicoff et al. 1994a, b).

IGF-1R and chemoresistance

The IGF-1R system plays a role in chemoresistance in three major ways. Firstly, activated IGF-1R enhances tumor growth and inhibits apoptosis. Expression of IGF-1R has been correlated with malignant potential, as the IGF system has been shown to have mitogenic and anti-apoptotic effects on malignant cells lines. Secondly, the IGF pathway has been shown to decrease chemosensitivity, possibly through the use of survival signals or DNA repair, where downstream signals created by activated IGF-1R block chemotherapeutic agents from their target. Finally, IGF1/IGF-1R signaling promotes cell cycle progression from G1 to S phase. The major downstream signaling pathways implicated are (1) PI3K-Akt and (2) Ras-Raf-MAPK (Figs. 3, 4).

There are many mechanisms of action that must be explored to understand the role of IGF-1R in chemoresistance. These are summarized below.

DNA repair

DNA repair pathways provide another possible target for IGF-1 therapy, as downregulation of these pathways will increase chemosensitivity of cells, thereby improving efficacy of chemotherapy. All of these downstream signaling pathways provide possible targets for improving treatment, and should be explored for their utility in both mesenchymal and epithelial cancer.

A recent study looking at the interaction between a p38 kinase-dependent mechanism and Ku-DNA binding found that activated IGF-1R protects tumor cells from breakdown (Fig. 3). The repair of double stranded breaks is a vital survival mechanism for tumor cells, which is regulated by the Ku70 and Ku86 (Featherstone and Jackson 1999). It was found that IGF-1R signaling via p38 kinase, but not through PI3K, resulted in down regulation of Ku86 levels in response to treatment. Furthermore, activation of IGF-1R resulted in cytoplasmic IGF-1R/p38 complex formation (Cosaceanu et al. 2007).

Salisbury and Macaulay (2003) used genetic silencing in the IGF system in human melanoma cell lines. The aim was to silence the downstream signaling pathway Atm, which is responsible for initiation of cell cycle checkpoints as well as DNA repair pathways (Salisbury and Macaulay 2003).

Another example of IGF-1R downstream signaling pathways inhibiting tumor growth has been shown in preclinical prostate cancer studies. Chemosensitisation was attributed to attenuation of IGF signaling via AKT, ERKS and p38, clearly indicating that IGF-1R targeted therapy provides increased chemosensitivity in prostate cancer (Rochester et al. 2005).

Cell cycle progression

Reports suggest that IGF1/IGF-1R signaling promotes cell cycle progression from G1 to S phase (Scotlandi et al. 2005). Our unpublished data shows that G1 arrest in human osteosarcoma cell lines, 143B and U2OS can be induced by using IGF-1R inhibitor AG1024, supporting the theory that IGF-1R plays an important role in cell cycle progression.

Survival signals

Anti-apoptotic effects through phosphorylation and deactivation of BAD have been observed as a result of activation of the AKT pathway. A recent study found that phosphorylated IRS-1 can activate the p85 regulatory subunit of PI3K, leading to activation of several downstream substrates, such as p70 S6 kinase and AKT. AKT phosphorylation enhances mTOR activation and triggers anti-apoptotic effects. IRS-1 has also been implicated in other signaling systems, and may therefore be involved in crosstalk between different systems. In parallel to PI3K driven signaling, mobilization of Grb2/SOS by phosphorylated IRS-1 or Shc leads to recruitment of Ras and activation of the Raf-1/MEK/ERK pathway, which has downstream effects resulting in cellular proliferation (Samani et al. 2007).

Another study documented the effects of membrane surface ligands that can exert their effects at the cell membrane surface to prevent receptor activation, as well as interfering with the function of second messengers such as Ras/PI3K/mTOR pathway (Zaidi et al. 2009). This research is useful for understanding the survival signals implemented by IGF-1R and may help to overcome chemoresistance.

Multi-drug resistant gene

The multi-drug resistant (MDR) gene, which encodes for the production of P-glycoprotein, has been thoroughly investigated in terms of its role in chemoresistance. The protein, encoded by this gene, is an ATP-dependent drug efflux pump for molecules, and has broad substrate specificity. It causes decreased drug accumulation in resistant cells, which often leads to MDR. In gastric carcinoma, it was found that over-expression of IGF-1R was correlated with poor prognosis, as was over-expression of MDR-associated protein-1 (MRP-1). Furthermore, over-expression of IGF-1R was positively correlated with MRP-1 over-expression. Despite chemotherapy, all 102 patients with co-expression of IGR-1R/MRP-1 had poor prognosis (Ge et al. 2009). This suggests a correlation between IGF-1R and MRP-1, which should be further examined for its utility in predicting the effect of chemotherapy and patient prognosis.

The use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) on MDR cells was also suggested to be quite effective. Cells with high levels of P-glycoprotein accumulated and retained high levels of doxorubicin in the presence of ibuprofen, curcumin and NS-389, conferring enhanced cytotoxicity and apoptosis (Angelini et al. 2008). This study could prove very useful, as the side effects of NSAIDS are almost negligible, and combination with chemotherapy could decrease the required dose of cytotoxics in MDR cells.

Other pathway interactions

A recent review described the role of the IGF-1R pathway in mediating resistance to cytotoxic chemotherapy, radiotherapy, as well as other targeted therapies such as tamoxifen and trastuzumab. It concludes that combination therapy with IGF-1R targeted therapy may overcome these particular types of resistance and improve patient prognosis (Casa et al. 2008).

The IGF system may alter the efficacy of chemotherapy, such as is the case with hepatocellular carcinoma cells. It was found that IGF-1 up-regulates the expression of glutathione transferase, thus reducing the redox-cycling potential of doxorubicin (Lee et al. 2007). Interestingly, a recent study found that high IGF-1R expression was correlated with reduced long-term local control due to tumor disease chemoresistance in patients who initially responded well to chemotherapy. This indicates a form of acquired resistance that is linked to high IGF-1R expression (Lloret et al. 2007).

Riedemann et al. (2007) hypothesized that signaling via IGF-1R confers resistance to the epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors in breast cancer, suggesting that EGFR could compensate for IGF-1R blockade. The results showed that although IGF-1R knockdown increased phosphorylation of EGFR downstream signaling, it was not enough to prevent chemotherapeutically induced apoptosis, suggesting that IGF-1R downstream signaling is a promising target (Riedemann et al. 2007).

Any or all of these pathways may hold the key for overcoming chemoresistance in human cancer. The rapid increase of data supporting the combination of IGF targeted therapy and chemotherapy, as well as increasing clinical trials, confirms that this is an optimistic potential area for oncology, that may help to tackle increasing chemoresistance.

IGF-1R targeted therapy

‘Targeted therapy’ is defined as therapy that specifically targets key molecules of tumor cells and/or associated cells with minimal effects to normal tissue. The definition of ‘targeted therapy’ also requires the use of a measurable ‘target’. Currently, the main targets are proteins involved in tumorigenesis, metastasis and cancer progression (Yang and Crowe 2007). IGF-1R inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies are two forms of IGF-1R targeted therapy, both of which have shown promising results.

IGF-1R targeted therapies have been extensively explored, as they are highly effective with acceptable side effects. Due to the similar structure of the IGF-1R and insulin receptor, there have been fears that anti-IGF-1R treatment might be diabetogenic. Recent clinical trials summarised in Table 1, report both hypo- and hyperglycaemic side-effects due to treatment. However, these were mild side-effects, which are manageable, and are far outweighed by the benefits of treatment. There were concerns about safety of IGF-1R targeted therapy, as IGF-1R expression is also found in normal tissue throughout the body, meaning that blockade of IGF-1R may interfere with some important physiological functions of normal cells (Niedernhofer et al. 2006). Therefore, the use of highly selective IGF-1R targeted therapy is required.

Table 1.

IGF-1R targeted therapy clinical trials

| Agent | Phase | Tumor cell type | Response | Adverse effects | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP-751871 | Fully human, monoclonal antibody, Pfizer | ||||

| I | Multiple myeloma | 47 patients treated with CP monotherapy, and 27 treated in combination with dexamethosone. 28 of the monotherapy cohort attained stable disease (SD). 9/27 combination cohort saw an effect | Diarrhea, rash, nausea, hyperglycemia (2.1%), increased aspartate aminotransferase (AST), anemia, thrombocytopenia | Lacy et al. (2006), (2008) | |

| I | Solid tumors/adrenocortical carcinoma, sarcoma expansion cohorts |

24 patients treated. At maximal dose, 7 of 12 attained SD. In Sarcoma cohort, 1 in 22 had partial response, and 6 in 22 had SD |

DVT, hyperuricemia, nausea, hyperglycemia, anorexia, fatigues, elevated gamma glutamyltransferase (GGT) and AST | Haluska et al. (20072007) | |

| + Paclitaxel (P)/carboplatin ± CP (I) (PC vs. PCI) | Ib/II | Non-small lung cancer (NSLCA) | 97 patients treated with all three drugs (PCI) and 53 patients treated with cytotoxics only (PC). Response rates 54 and 41%, respectively | Hyperglycemia (15/5%), neutropenia (18/12%), thrombocytopenia (6/1%), neuropathy (5/1%), anorexia, fatigue | Karp et al. (20072007) |

| AMG-479 | Fully human, monoclonal antibody (IgG1), Amgen | ||||

| I | Solid tumors, Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 33 patients treated—1 complete response (Ewing’s sarcoma), 1 partial response, 1 minor response (both neuroendocrine), 5 attained SD, and 1 mixed response (breast) | Hyperglycemia, thrombocytopenia (9/3%), arthralgia (3%/−), diarrhea (3%/−), autoantibody production, transaminitis (2%/−) | Tolcher et al. (2007); Sarantopoulos et al. (20082008) | |

| + Gemcitabine (G) or panitumumab (P) | Ib | Solid tumors | 18 patients treated **(10—P, 8—G). 1 partial response in P cohort (Colon), and 9/18 attained SD (5 in P arm, 4 in G arm) | + P: hyperglycemia (10%), rash (20%), hypomagnesaemia (30%), anemia, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, diarrhea, fatigue, dizziness and thrombocytopenia. +G: neutropenia (50%), fatigue, vomiting, thrombocytopenia, anemia, nausea, rash, hypomagnesaemia | Sarantopoulos et al. (2008) |

| IMC-A12 | Fully human, monoclonal antibody (IgG1), ImClone | ||||

| I | Solid tumor | 15 patients treated. 4 of 11 attained SD, 2 attained SD >9 months, and 1 had >25% reduction in PSA | Hyperglycemia, pruritis, rash, infusion reaction, psoriasis, anemia and discolored feces | Higano et al. (2007) | |

| MK-0646 | Humanised monoclonal antibody, Merck | ||||

| I | Solid tumors, multiple myeloma, breast |

Q2w: 36 patients treated every 2 weeks. 5 patients with SD >4 months, 2 patients >1 year. Qw: 53 patients treated weekly showed a decrease in IGF-1R expression and signaling (e.g. AKT). 3 showed metabolic responses, 1 mixed response (Ewing’s) and 3 patients attained SD >3 months |

Q2w: Thrombocytopenia, GI bleeding, pneumonitis, transaminitis, abdominal pain, weight loss, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, fatigue, constipation. Qw: Tumor pain, hyperglycemia, chills, nausea, pyrexia, infusion reaction |

Atzori et al. (2008); Hidalgo et al. (20082008) | |

| R1507 | Fully human, monoclonal antibody (IgG1), Roche | ||||

| I | Solid tumors—adult, children | 26 patients treated, 11 attained SD >15 weeks | Adults: infection, fatigue, rash, fever, back pain, abdominal paint, arthralgia, diarrhea, fever | Rodon et al. (20072007) | |

| AVE-1642 | Humanised monoclonal antibody, Sanofi-Aventis | ||||

| + Docetaxel | I | Solid tumors | 14 patients with solid tumors—1 reduction in skin nodules (breast), and 4 attained SD at cycle 4 | Hyperglycemia, hypersensitivity reactions, pruritis, parasthesia**, anemia | Tolcher et al. (20082008) |

| INSM-18 (NDGA) | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor of IGF-1R, HER2/neu, Insmed | ||||

| I | Prostate cancer | 15 patients treated, 1 had >50% reduction in PSA, and 1 had reduction in PSA doubling time | Transaminitis | Harzstark et al. (20072007) | |

Antibodies are highly selective inhibitors of the IGF-1R, by inducing rapid internalization and down-regulation of the receptor. Conversely, small molecule tyrosine kinase inhibitors display a lack of selectivity due to binding with a well-conserved site. To overcome this, many inhibitors in development are dual inhibitors, which generally do not lead to internalization and down-regulation. Anti-IGF-1R therapy also offers the advantage of being able to control the duration of drug exposure, in contrast to long-lasting antibodies (Traxler 2003).

The development of highly specific anti-IGF-1R therapy has overcome most fears regarding its use. Anti-IGF-1R therapy has the potential to lower dose ranges of cytotoxic chemotherapy, thus minimizing adverse side-effects. Furthermore, combination therapy could allow much more effective treatment, with far fewer side-effects than current chemotherapy alone.

Combination therapy using anti-IGF-1R approach with chemotherapy

Since the IGF system plays an important role in chemoresistance, blockade of this system will result in enhancement of chemosensitivity/chemotherapy or achieving the same cancer inhibition effect with reduced dose of chemotherapeutic drugs. In vitro studies support that combination therapy can provide more promising results than single use of chemotherapy or IGF-1R targeted therapy. For example, Scotlandi et al. (2005) used a particular kinase inhibitor of IGF-1R known as NVP-AEW541 in combination with vinicristine, actinomycin D, doxorubicin, cisplatin and ifosfamide. The three most frequent tumors in children and adolescents (Ewing’s sarcoma, osteosarcoma and rhabdomyosarcoma) were tested. NVP-AEW541 induced a G1 cell-cycle block in all cells tested, however, apoptosis was only seen in cells that showed a high sensitivity. This study showed that combination of NVP-AEW541 and vinicristine synergistically inhibited Ewing’s sarcoma in rodent models, and produced positive interactions when combined with ifosfamide and actinomycin D in all other cell lines. Combination therapy with doxorubicin and cisplatin, however, yielded only subadditive effects in the tested cell lines (Scotlandi et al. 2005).

Many unpublished in vitro studies insist that this approach, combining IGF-1R targeted therapy and chemotherapy, is an effective treatment, since many clinical trials using this approach are authorised and ongoing. For example, a phase 1b trial (Hoffmann-La Roche, NCT00811993) is currently being conducted to evaluate the safety of combining IGF-1R-antagonist R1507 with many different chemotherapeutics, including gemcitabine, in highly malignant tumors. Another clinical phase I/II trial is being conducted to test the effects of gemitabine with or without the monoclonal antibody erlotinib in patients with inoperable metastatic pancreatic cancer (Southwest Oncology Group and National Cancer Institute, NCT00617708). Another example is a randomised phase III study investigating the IGF-1R monoclonal antibody CP-751871 in combination with docetaxel for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (Pfizer, NCT00596830). Numerous clinical studies (phase I–III) are being planned or are ongoing to test the hypothesis that IGF-1R inhibition will enhance the activity of cytotoxic chemotherapeutics in all types of cancer. Some completed phase I trials are listed in Table 1.

This area of oncology continues to grow, as new information comes to light, and it is important that research persists for improved treatment of current and future patients. With chemoresistance increasing, and limited chemotherapeutic options available, novel approaches such as targeted therapy, may be the best hope for oncologists to tackle the increasing problem of cancer. The IGF system has long been implicated in chemoresistance and tumor protection, and thus, offers an attractive potential target, particularly in combination with surgery, chemotherapeutics and other adjuvant therapies.

Conclusion

The current treatment protocol for many cancers is insufficient, due to patient response rates and side-effects of treatment. There are very few options for patients who do not respond well to the limited first-line chemotherapy drugs available (e.g. ifosfamide and doxorubicin). Meanwhile, acceptable margins of resection are often difficult to achieve. Targeted therapies directed against cancer specific molecules and signaling pathways have been developed to achieve tumor selectivity, and hence, limit non-specific toxicities. The IGF-1 pathway has the potential to control tumor activity, and overcome chemoresistance. IGF-1R inhibition as mono-therapy has proven effective in select groups of patients of many cancers, such as breast cancer, sarcoma, prostate cancer, lung cancer and hepatocellular carcinoma. Although IGF-1R targeted therapy has the potential to stifle tumor growth, chemotherapy will still be required for many patients with metastatic and advanced disease. Furthermore, IGF-1R targeted therapy has the potential to improve chemosensitivity by overcoming chemoresistance. There is strong evidence to suggest that the combination of chemotherapy and IGF-1R targeted therapy has the potential to dramatically improve management and prognosis of cancer patients. The downstream signaling pathways of the IGF-1R, including the Ras-Raf-MAPK and PI3K-AKT pathway also show potential in the treatment of cancer, as these could provide even more specific targets for treatment. Further investigation of IGF-1R targeted therapy, including its downstream signals, in combination with chemotherapeutics is warranted in all cancers.

Conflict of interest statement

I confirm that all authors do not have any conflict of interest.

References

- Angelini A, Iezzi M, Di Febbo C, Di Ilio C, Cuccurullo F, Porreca E (2008) Reversal of P-glycoprotein-mediated multidrug resistance in human sarcoma MES-SA/Dx-5 cells by nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Oncol Rep 20:731–735 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora A, Scholar EM (2005) Role of tyrosine kinase inhibitors in cancer therapy. J Pharmacol Exp Therapeutics 315:971–979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atzori F, Tabernero J, Cervantes A, Botero M, Hsu K, Brown H et al (2008) A phase I, pharmacokinetic (PK) and pharmacodynamic (PD) study of weekly (qW) MK-0646, an insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor (IGF1R) monoclonal antibody (MAb) in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumors. ASCO Meet Abstr 26:3519 [Google Scholar]

- Bohula EA, Playford MP, Macaulay VM (2003) Targeting the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor as anti-cancer treatment. Anticancer Drugs 14:669–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burfeind P, Chernicky C, Rininsland F, Ilan J, Ilan J (1996) Antisense RNA to the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor suppresses tumor growth and prevents invasion by rat prostate cancer cells in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:7263–7268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busund L, Ow K, Russell P, Crowe PJ, Yang J (2004) Expression of insulin-like growth factor mitogenic signals in adult soft-tissue sarcomas: significant correlation with malignant potential. Virchows Arch 444:142–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carboni JM, Lee AV, Hadsell DL, Rowley BR, Lee FY, Bol DK et al (2005) Tumor development by transgenic expression of a constitutively active insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. Cancer Res 65:3781–3787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casa AJ, Dearth RK, Litzenburger BC, Lee AV, Cui X (2008) The type I insulin-like growth factor receptor pathway: a key player in cancer therapeutic resistance. Front Biosci 13:3273–3287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chernicky C, Yi L, Tan H, Gan S, Ilan J (2000) Treatment of human breast cancer cells with antisense RNA to the type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor inhibits cell growth, suppresses tumorigenesis, alters the metastatic potential, and prolongs survival in vivo. Cancer Gene Ther 7:385–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark MA, Fisher C, Judson IM, Thomas JM (2005) Soft-tissue sarcomas in adults. N Engl J Med 353:701–711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosaceanu D, Budiu RA, Carapancea M, Castro J, Lewensohn R, Dricu A (2007) Ionising radiation activates IGF-1R triggering a cytoprotective signaling by interfering with Ku-DNA binding and by modulating Ku86 expression via a p38 kinase-dependent mechanism. Oncogene 26:2423–2434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Criswell T, Beman M, Araki S, Leskov K, Cataldo E, Mayo LD et al (2005) Delayed activation of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptro/Src/MAPL/Egr-1 signaling regulates clusterin expression, a pro-survival factor. J Biol Chem 280:14212–14221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djavan B, Waldert M, Seitz C, Marberger M (2001) Insulin-like growth factors and prostate cancer. World J Urol 19:225–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druckman R, Rohr U (2002) IGF-1 in gynaecology and obstetrics. Maturitas 41:S65–S83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ericsson C, Girnita L, Seregard S, Bartolazzi A, Jager M, Larsson O (2002) Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor in uveal melanoma: a predictor for metastatic disease and a potential therapeutic target. Invest Opthalmol Vis Sci 43:1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Featherstone C, Jackson SP (1999) Ku, a DNA repair protein with multiple cellular functions? Mutat Res 434:3–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia M, Jemal A, Ward EM, Center MM, Hao Y, Siegel RL et al (2007) American Cancer Society, Atlanta, GA

- Ge J, Chen Z, Wu S, Chen J, Li X, Li J et al (2009) Expression levels of insulin-like growth factor-1 and multidrug resistance-associated protein-1 indicate poor prognosis in patients with gastric cancer. Digestion 80:148–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil-Ad I, Shtaif B, Luria D, Karp L, Fridman Y, Weizman A (1999) Insulin like growth factor 1 (IGF-1R) antagonises apoptosis induced by serum deficiency and doxorubicin in neuronal cell culture. Growth Horm IGF Res 9:458–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giovannucci E (2001) Insulin, insulin-like growth factors and colon cancer: a review of the evidence. J Nutr 131:3109S–3120S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Girnita L, Girnita A, Prete F, Bartolazzi A, Larrson O, Axelson M (2004) Cyclolignans as inhibitors of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor and malignant cell growth. Cancer Res 64:236–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gooch JL, Van Den Berg CL, Yee D (1999) Insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) rescues breast cancer cells from chemotherapy-induced cell death—proliferative and anti-apoptotic effects. Breast Cancer Res Treat 56:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakam A, Yeatman T, Lu L, Mora L, Marcet G, Nicosia S et al (1999) Expression of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor in human colorectal cancer. Hum Pathol 30:1128–1133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haluska P, Shaw H, Batzel GN, Molife LR, Adjei AA, Yap TA et al (2007) Phase I dose escalation study of the anti-IGF-1R monoclonal antibody CP-751,871 in patients with refractory solid tumors. ASCO Meet Abstr 25:3586 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LN, You F, Schnitt SJ, Witkiewicz A, Lu X, Sgroi D et al (2007) Predictors of resistance to preoperative trastuzumab and vinorelbine for HER2-positive early breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13:1198–1207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartog H, Wesseling J, Boezen HM, van der Graaf WT (2007) The insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor in cancer: old focus, new future. Eur J Cancer 43:1895–1904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harzstark AL, Ryan C, Diamond M, Jones J, Zavodovskaya M, Maddux B et al (2007) A phase I trial of nordihydroguareacetic acid (NDGA) in patients with non-metastatic prostate cancer and rising PSA. J Clin Oncol 25:15500 [Google Scholar]

- Hewish M, Chau I, Cunningham D (2009) Insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor targeted therapeutics: novel compounds and novel treatment strategies for cancer medicine. Recent Pat Anticancer Drug Discov 4:54–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hidalgo M, Tirado Gomez M, Lewis N, Vuky JL, Taylor G, Hayburn JL et al (2008) A phase I study of MK-0646, a humanized monoclonal antibody against the insulin-like growth factor receptor type 1 (IGF1R) in advanced solid tumor patients in a q2 wk schedule. ASCO Meet Abstr 26:3520 [Google Scholar]

- Higano CS, Yu EY, Whiting SH, Gordon MS, LoRusso P, Fox F et al (2007) A phase I, first in man study of weekly IMC-A12, a fully human insulin like growth factor-I receptor IgG1 monoclonal antibody, in patients with advanced solid tumors. ASCO Meet Abstr 25:3505 [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg Z (2002) Mechanisms of steroid impairment of growth. Horm Res 58:33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang F, Greer A, Hurlburt W, Han X, Hafezi R, Wittenberg GM et al (2009) The mechanisms of differential sensitivity to an insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor inhibitor (BMS-536924) and rationale for combining with EGFR/HER2 inhibitors. Cancer Res 69:161–170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Smigal C et al (2006) Cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 56:106–130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang Y, Rom WN, Yie TA, Chi CX, Tchou-Wong KM (1999) Induction of tumor suppression and glandular differentiation of A549 lung carcinoma cells by dominant-negative IGF-1 receptor. Oncogene 18:6071–6077 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karp DD, Paz-Ares LG, Blakely LJ, Kreisman H, Eisenberg PD, Cohen RB et al (2007) Efficacy of the anti-insulin like growth factor I receptor (IGF-IR) antibody CP-751871 in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin as first-line treatment for advanced non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). ASCO Meet Abstr 25:7506 [Google Scholar]

- Karp DD, Paz-Ares LG, Novello S, Haluska P, Garland L, Cardenal F et al (2009) Phase II study of the efficacy of the anti-insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor antibody CP-751, 871 in combination with paclitaxel and carboplatin in previously untreated, locally advanced, or metastatic non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol 27:2516–2522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper B, Gil T, D’Hondt V, Gebhart M, Awada A (2007) Novel treatment strategies for soft tissue sarcoma. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 62:9–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korc M (1998) Role of growth factors in pancreatic cancer. Surg Oncol Clin N Am 7:25–41 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn C, Hurwitz SA, Kumar MG, Cotton J, Spandau DF (1999) Activation of the insulin like growth factor-1 receptor promotes the survival o human keratinocytes following ultraviolet B irradiation. Int J Cancer 80:431–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacy M, Alsina M, Melvin CL, Roberts L, Yin D, Petersen A et al (2006) Phase 1 first-in-human dose escalation study of cp-751,871, a specific monoclonal antibody against the insulin like growth factor 1 receptor. J Clin Oncol 24:7609 [Google Scholar]

- Lacy MQ, Alsina M, Fonseca R, Paccagnella ML, Melvin CL, Yin D et al (2008) Phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the anti-insulin like growth factor type 1 Receptor monoclonal antibody CP-751, 871 in patients with multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 26:3196–3203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert LA, Qiao N, Hunt KK, Lambert DH, Mills GB, Meijer L et al (2008) Autophagy: a novel mechanism of synergistic cytotoxicity between doxorubicin and roscovitine in a sarcoma model. Cancer Res 68:7966–7974 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larrson O, Girnita A, Girnita L (2005) Role of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor signaling in cancer. Br J Cancer 92:2097–2101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C, Wu S, Gabrilovich D, Chen H, Nadaf-Rahrov S, Ciernik I et al (1996) Antitumor effects of an adenovirus expressing antisense insulin-like growth factor I receptor on human lung cancer cell lines. Cancer Res 56:3038–3041 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Han CY, Yang JW, Smith C, Kim SK, Lee EY et al (2007) Induction of glutathione transferase in insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor—overexpressed hepatoma cells. Mol Pharmacol 72:1082–1093 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Turbyville T, Fritz A, Whitesell L (1998a) Inhibition of insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor expression in neuroblastoma cells induces the regression of established tumors in mice. Cancer Res 58:5432–5438 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Lehar S, Corvi C, Payne G, O’Connor R (1998b) Expression of the insulin like growth factor 1 receptor C terminus as a myristylated protein leads to induction of apoptosis in tumor cells. Cancer Res 58:570–576 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloret M, Lara PC, Bordon E, Pinar B, Rev A, Falcon O et al (2007) IGF-1R expression in localised cervical carcinoma patients treated by radiochemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol 106:8–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez T, Hanahan D (2002) Elevated levels of IGF-1 receptor convey invasive and metastatic capability in a mouse model of pancreatic islet tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell 1:339–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay VM (2004) The IGF receptor as anticancer treatment target. Novartis Found Symp 262:235–243 (discussion 243–246) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney E, McLaughlin J, Dagdigian N, Garrett L, Connors K, Zhou XH et al (2003) An anti-insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor antibody that is a potent inhibitor of cancer cell proliferation. Cancer Res 63:5073–5083 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niedernhofer LJ, Garinis GA, Raams A, Lalai AS, Robinson AR, Appeldoorn E et al (2006) A new progeroid syndrome reveals that genotoxic stress suppresses the somatotroph axis. Nature 444:1038–1043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters JM, Tsark EC, Wiley LM (1996) Radiosensitive target in the mouse embryo chimera assay: implications that the target involves autocrine growth factor function. Radiat Res 175:722–729 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pollak M (2000) Insulin-like growth factor physiology and cancer risk. Eur J Cancer 36:1224–1228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicoff M, Coppola D, Sell C, Rubin R, Ferrone S, Baserga R (1994a) Growth inhibition of human melanoma cells in nude mice by antisense strategies to type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Cancer Res 54:4848–4850 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnicoff M, Sell C, Rubini M, Coppola D, Ambrose D, Baserga R et al (1994b) Rat glioblastoma cells expressing an antisense RNA to the insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1R) receptor are nontumorigenic and induce regression of wild-type tumors. Cancer Res 54:2218–2222 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedemann J, Sohail M, Macaulay VM, Riedemann J, Sohail M, Macaulay VM (2007) Dual silencing of the EGF and type 1 IGF receptors suggests dominance of IGF signaling in human breast cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 355:700–706 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rochester MA, Riedemann J, Hellawell GO, Brewster SF, Macaulay VM, Rochester MA et al (2005) Silencing of the IGF1R gene enhances sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents in both PTEN wild-type and mutant human prostate cancer. Cancer Gene Ther 12:90–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodon J, Patnaik A, Stein M, Tolcher A, Ng C, Dias C (2007) A phase I study of q3W R1507, a human monoclonal antibody IGF-1R antagonist in patients with advanced cancer. ASCO Meet Abstr 25:3590 [Google Scholar]

- Sachdev D, Yee D (2001) The IGF system and breast cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer 8:197–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salisbury AJ, Macaulay VM (2003) Development of molecular agents for IGF receptor targeting. Horm Metab Res 35:843–849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samani A, Yakar S, LeRoith D, Brodt P (2007) The role of the IGF system in cancer growth and metastasis: overview and recent insights. Endocr Rev 28:20–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarantopoulos J, Mita AC, Mulay M, Romero O, Lu J, Capilla F et al (2008) A phase IB study of AMG 479, a type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor (IGF1R) antibody, in combination with panitumumab (P) or gemcitabine (G). ASCO Meet Abstr 26:3583 [Google Scholar]

- Scharf J, Dombrowski F, Ramadori G (2001) The IGF axis and hepatocarcinogenesis. J Clin Pathol 54:138–144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotlandi K (2006) Targeted therapies in Ewing’s sarcoma. Adv Exp Med Biol 587:13–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scotlandi K, Manara MC, Nicoletti G, Lollini PL, Lukas S, Benini S et al (2005) Antitumor activity of the insulin-like growth factor-I receptor kinase inhibitor NVP-AEW541 in musculoskeletal tumors. Cancer Res 65:3868–3876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sell C, Rubini M, Rubin R, Liu JP, Efstratiadis A, Baserga R (1993) Simian virus 40 large tumor antigen is unable to transform mouse embryonic fibroblasts lacking type 1 insulin-like growth factor receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 90:11217–11221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmacz E (2000) Function of the IGF-1 Receptor in breast cancer. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 5:95–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surmacz E (2003) Growth factor receptors as therapeutic targets: strategies to inhibit the insulin-like growth factor 1 receptor. Oncogene 22:6589–6597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka S, Arii S (2009) Molecularly targeted therapy for hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Sci 100:1–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tolcher AW, Rothenberg ML, Rodon J, Delbeke D, Patnaik A, Nguyen L et al (2007) A phase I pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of AMG 479, a fully human monoclonal antibody against insulin-like growth factor type 1 receptor (IGF-1R), in advanced solid tumors. ASCO Meet Abstr 25:3002 [Google Scholar]

- Tolcher AW, Patnaik A, Till E, Takimoto CH, Papadopoulos KP, Massard C et al (2008) A phase I study of AVE1642, a humanized monoclonal antibody IGF-1R (insulin like growth factor1 receptor) antagonist, in patients (pts) with advanced solid tumor. ASCO Meet Abstr 26:3582 [Google Scholar]

- Traxler P (2003) Tyrosine kinases as targets in cancer therapy—successes and failures. Oncol Res 7:215–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner B, Haffty B, Narayanan L, Yuan J, Havre P, Gumbs A et al (1997) Insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor overexpression mediates cellular radioresistance and local breast cancer recurrence after lumpectomy and radiation. Cancer Res 57:3079–3083 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasilcanu D, Girnita A, Girnita L, Vasilcanu R, Axelson M, Larsson O (2004) The cyclolignan PPP induces activation loop-specific inhibition of tyrosine phosphorylation of the insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor. Link to the phosphatidyl inositol-3 kinase/Akt apoptotic pathway. Oncogene 23:7854–7862 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Mehren M (2003) New therapeutic strategies for soft tissue sarcomas. Curr Opin Oncol 4:441–451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner H, Le Roith D (2000) New concepts in regulation and function of the insulin-like growth factors: implications for understanding normal growth and neoplasia. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93:8318–8323 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weroha SJ, Haluska P (2008) IGF-1 receptor inhibitors in clinical trials—early lessons. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 13:471–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wunder J, Nielsen T, Maki R, O’Sullivan B, Alman B (2007) Opportunities for improving the therapeutic ratio for patients with sarcoma. Lancet Oncol 8:513–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y, Skytting B, Nilsson G, Brodin B, Larsson O (1999) Expression of insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor in synovial sarcoma: association with an aggressive phenotype. Cancer Res 59:3588–3591 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yakar S, LeRoith D, Brodt P (2005) The role of the growth hormone/insulin-like growth factor axis in tumor growth and progression: lessons from animal models. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 16:407–420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang JL, Crowe PJ (2007) Targeted therapies in adult soft tissue sarcomas. J Surg Oncol 95:183–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaidi SH, Huddart RA, Harrington KJ (2009) Novel targeted radiosensitisers in cancer treatment. Curr Drug Discov Technol 6:103–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]