Abstract

Purpose

The aim of this study was to investigate the expression of the PRL-3 in human invasive breast cancer and to evaluate its clinical and prognostic significance. Its potential role in the invasive-metastatic properties of invasive breast cancer was also investigated.

Methods

Protein expression of PRL-3 was evaluated by immunohistochemistry for a consecutive series of 82 invasive human breast cancer tissues and 63 matched lymph node metastases, including PRL-3 mRNA expression analyzed by reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in malignant, nonmalignant breast tissue samples and lymph node metastases. We investigated the correlation of PRL-3 with clinicopathologic features, Overall and recurrence-free survival distribution curves were assessed using the Kaplan–Meier test and log-rank statistics, followed by Cox proportional hazards regression model.

Results

We found that 70.7% patients expressed a high level of PRL-3 protein in their tumors, and its over expression was positive correlated with lymph node metastasis (LNM) (P = 0.011). Moreover, The PRL-3 mRNA expression was significantly higher in malignant compared to benign breast tissue, while increased expression of PRL-3 mRNA was significantly associated with LNM (P = 0.002). Univariate analysis showed that the positive expression of PRL-3 was a poor risk prognostic factor (OS, P = 0.045; RFS, P = 0.034). Multivariate analysis using the Cox regression model indicated that high PRL-3 expression was an independent unfavorable prognostic factor for RFS.

Conclusions

These results strongly suggest that PRL-3 expression can indicate the potential role of LNM to some extent. Increasing the risk of tumor metastasis (OR = 3.889). Our results also imply that PRL-3 might be a novel molecular marker for predicting relapse of invasive breast cancer.

Keywords: PRL-3, Breast cancer, Lymph node metastasis, Gene expression, Prognosis

Introduction

Breast cancer is the most frequent cancer in the world. Metastasis of breast cancer to the lymph nodes is often responsible for the high mortality rate (Chambers et al. 2002). Because the primary tumors can usually be resected by surgery. Involvement of regional lymph nodes is an important prognostic factor for breast carcinoma. The mechanisms involved in breast cancer metastasis are not fully clarified because it involves multiple steps and requires the accumulation of altered expression of many different genes. Although many molecular factors have been identified from some researches, much remains to be learned about the metastatic process to provide a new therapeutic target for these metastatic lesions. Thereby, it is necessary to identify the special gene in the field of invasion and metastasis of breast cancer.

Phosphatase of regenerating liver (PRL)-3 gene is known as a metastasis-associated phosphatase (Bardelli et al. 2003; Marx 2001; Saha et al. 2001; Zeng et al. 1998). It was also known as PTP4A3, belongs to a small class of tyrosine phosphatases, which codes a 22-kD low molecular weight tyrosine phosphatase with a C-terminal prenylation motif (Cates et al. 1996; Zeng et al. 2000). It was found to be associated with the early endosome and plasma membrane in its prenylated state, while nuclear localization of these enzymes may occur in the absence of prenylation (Zeng et al. 2000). PRL-3 has at least 75% amino-acid sequence similarity with PRL-1 and PRL-2, the other two members of the PRL family (Diamond et al. 1994; Zeng et al. 2000). Overexpression of PRL-3 has been identified in several human cancers including colorectal, gastric, ovarian cancer as compared with their normal tissues (Kato et al. 2004; Miskad et al. 2004; Peng et al. 2004; Polato et al. 2005), and there are several reports showing its importance in cancer cells invasion and migration (Matter et al. 2001; Qian et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2004; Zeng et al. 2003). Recently, more and more findings strongly suggest that an excess of PRL-3 expression may play a key role in the acquisition of metastatic potential of tumor cells (Li et al. 2007; Liu et al. 2008; Rouleau et al. 2006; Wang et al. 2007b, 2008), and in several studies, it has also been associated with poor prognosis. To date, there were only two studies that investigated the association of PRL-3 with breast cancer using immunohistochemical detection found positive or increased PRL-3 protein expression in a subset of tumors. In addition to, the relationship between the PRL-3 proteins and the breast cancer is still not well understood. Therefore, it is necessary to provide more documents to increase the dataset.

In the present study, we undertook to examine the significance of PRL-3 in a cohort of women with invasive breast cancer and the metastatic lymph nodes using immunohistochemical techniques. We also analyzed the expression of PRL-3 mRNA in some fresh specimens. The purpose of the present study was to gain further insight into the prognostic value of PRL-3 expression in invasive breast cancer. Furthermore, its possible impact on the LNM of human invasive breast cancer was also investigated.

Materials and methods

Patients and tumor samples

Paraffin-embedded surgical specimens of 82 invasive breast cancers and 63 cases of matched metastatic lymph nodes were obtained from the Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical College, from January 2001 to June 2002, were included in the study. Specimens were diagnosed histopathologically and staged according to the TNM-International Union against Cancer classification system. A total of 95 fresh specimens were put in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80°C after resected from the patient immediately. They consisted of 45 cases of breast cancer tissues, 15 cases of normal tissues, 20 cases of matched metastatic lymph nodes, 15 cases of adenoma tissues. We excluded patients with distant metastases at the time of the diagnosis, synchronous or metachronous bilateral breast cancer, malignancy other than breast cancer in history, and the patients who had received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy before surgery. Informed consent was obtained from all of the patients. Follow-up focused specifically on recurrence (local and distant), recurrence-free survival, overall survival, and cancer-related death. The data collected were entered prospectively into the registry database.

Immunohistochemistry

For immunohistochemical studies, 4 μm sections were cut from paraffin blocks form 82 cases of breast cancer tissues and 63 cases of matched metastatic lymph nodes. Slides were dried in an oven (55–60°C) before being deparaffinized in several changes of xylene and hydrated through a series of graded alcohols to water. For antigen retrieval, slides underwent microwave treatment in 1 mM EDTA (pH 8.0) for 20 min, followed by a 20-min cool-down under running water. After washing in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), the slides were exposure to 10% normal goat serum for 10 min to reduce non-specific binding, this was followed by an overnight incubation at 4°C in a humidified chamber with polyclonal rabbit anti-human PRL-3 antibody (1:300 dilution; Sigma, USA). The antigen–antibody reaction was visualized by Picture Plus Kit (Zymed, USA) and diaminobenzidine as the chromogen. Finally, hematoxylin was used as a counterstain. Negative controls were processed as above except for the primary antibodies were used. Sections of colon cancer known to express PRL-3 were used as positive control.

Evaluation of staining

For PRL-3 assessment, determination of the intensity of the immunohistochemical staining was performed according to Wang et al. (2006). The staining in the cytoplasm and the cytoplasmic membrane was evaluated. The score for PRL-3 staining was graded as follows: no staining or staining observed in <10% of tumor cells was given a score 0; not/barely perceptible staining detected in ≥10% of tumor cells was scored as 1+; a moderate or strong complete staining observed in ≥10% of tumor cells was scored as 2+ or 3+; respectively. A score of 0 and 1+ was considered negative, whereas 2+ and 3+ were considered positive. All slides were reviewed independently by two pathologists without previous clinical information. When the interpretation differed between the two observers, slides were revaluated for a final decision at a conference microscope.

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction analysis

Total RNA of fresh tissues was isolated by chloroform extraction using Trizol reagent according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Purified total RNA was subjected to formaldehyde gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry (A260 and A280 nm) to assess integrity and purity. Total RNA was reverse-transcribed with the Advantage™ reverse transcription (RT)-for-polymerase chain reaction (PCR) kit. Briefly, 2.5 μg of RNA was reverse-transcribed and amplified for 30 cycles (PRL-3) with an annealing temperature of 60°C. Primer sequences for PRL-3 was 5′-GGGACTTCTCAGGTCGTGTC-3′ (forward) and 5′-AGCCCCGTACTTCTTCAGGT-3′ (reverse). The house-keeping gene β-actin was used as an internal control. Polymerase chain reaction products were subjected to gel electrophoresis on 1.5% agarose gels under standard conditions. The agarose gel was scanned by a densitometer for quantification.

Statistical analysis

The relationships between the results of the immunohistochemical study and clinicopathological variables were tested by Pearson’s χ2 test. Student’s t test was performed to evaluate the possible differences of PRL-3 mRNA expression in different groups of patients. McNemar’s χ2 test and Mann–Whitney U test were used as appropriate. Recurrence free survival (RFS) and over survival (OS) curves were obtained using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared with the log-rank test. Cox regression proportional hazards models were used to estimate the impact of PRL-3 expression on RFS and OS in both univariate and multivariate analysis. All statistical tests were two sided and carried out with the SPSS 13.0 statistical software package. A P value less than 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

Patient characteristics

The median age at diagnosis for the 82 patients was 51.5 (range 32–70 years). 46.3% (n = 38) of the patients were younger than 50 years, and 76.8% (n = 63) of the patients had lymph node metastasis at the time of surgery (Table 1). Median follow-up time for the 82 subjects was 66 months (range 13–88 months). During this observation time, 28 patients developed recurrent disease, and 22 died from their cancer. Recurrences were confirmed by permanent pathologic diagnoses.

Table 1.

Expression of PRL-3 in 82 patients with invasive breast cancer and its correlation with clinicopathologic characteristics

| Variables | PRL-3 expression | Positive rate (%) | χ 2 | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | ||||

| Age | |||||

| <50 years | 28 | 10 | 73.7 | 0.298 | 0.585 |

| ≥50 years | 30 | 14 | 68.2 | ||

| Tumor size | |||||

| <2 cm | 20 | 11 | 64.5 | 0.930 | 0.335 |

| ≥2 cm | 38 | 13 | 74.5 | ||

| Lymph node status | |||||

| + | 49 | 14 | 77.8 | 6.521 | 0.011 |

| − | 9 | 10 | 47.4 | ||

| Clinical stage | |||||

| I/II | 51 | 19 | 72.9 | 0.460 | 0.498 |

| III | 7 | 5 | 58.3 | ||

| ER status | |||||

| Positive | 41 | 14 | 74.5 | 1.174 | 0.279 |

| Negative | 17 | 10 | 63.0 | ||

| PR status | |||||

| Positive | 44 | 15 | 74.6 | 1.502 | 0.220 |

| Negative | 14 | 9 | 60.9 | ||

| Her-2 status | |||||

| Positive | 11 | 3 | 78.6 | 0.149 | 0.700 |

| Negative | 47 | 21 | 69.1 | ||

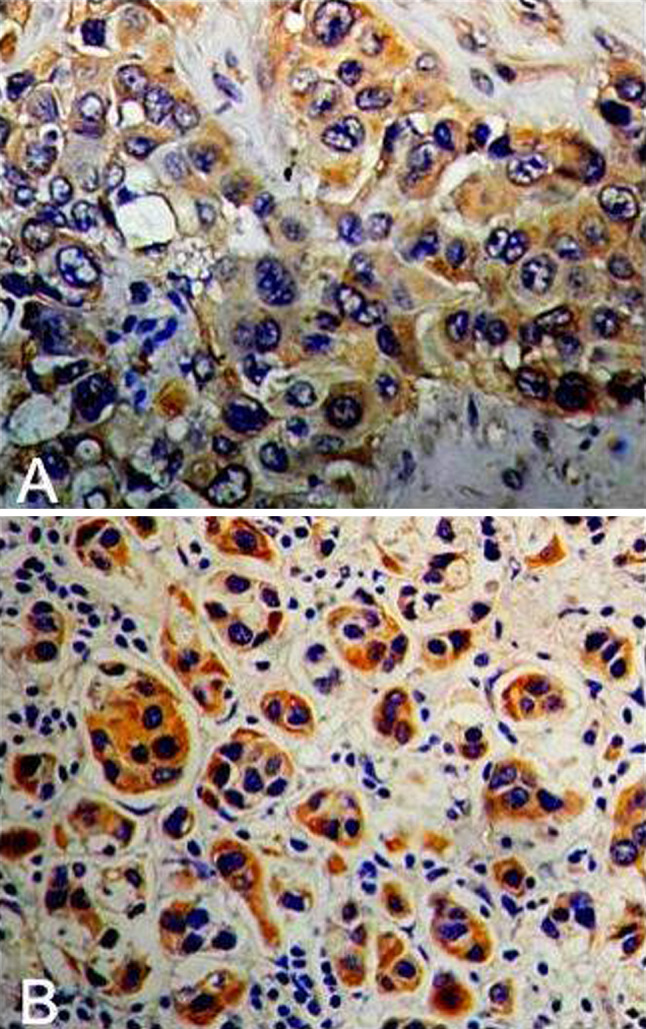

PRL-3 protein expression and its association with relevant clinicopathological parameters

Positive staining of PRL-3 proteins was seen in the cytoplasm of tumor cells (Fig. 1a, b). High PRL-3 expression was observed in 58 of 82 tumor samples (70.7%). The expression of PRL-3 was positive correlated with LNM. The expression of PRL-3 with LNM was 77.8% and it was 47.4% without LNM in breast cancer tissues (χ2 = 6.521, P = 0.011; OR = 3.889, 95% CI = 1.322–11.438). To determine more precisely the differences of PRL-3 protein expression in breast cancers, we compared the PRL-3 expression in 63 cases of primary breast cancers with that in their corresponding metastatic lymph nodes. The positive rate of metastatic lymph nodes was significantly higher than that of primary breast cancers, 60 of 63 (95.2%) lymph node metastases showed a positive staining for PRL-3, whereas only 49 of 63 (77.8%) of the corresponding primary tumors were PRL-3 positive. This difference was statistically significant (P = 0.003) (Table 2). The above data indicated that PRL-3 was associated with the metastasis of breast cancer to some extent. As showed in Table 1, there was no significant association between PRL-3 expression and age (P = 0.585), size of primary tumor (P = 0.335), clinical stage (P = 0.498), ER status (P = 0.279), PR status (P = 0.220) and Her-2 status (P = 0.700).

Fig. 1.

Expression of PRL-3 protein in (a) breast cancer tissues and (b) metastatic lymph nodes. The primary breast cancers and metastatic lymph nodes showed PRL-3-positive staining in the cancer cells (a, b). Original magnification is ×200

Table 2.

Expression of PRL-3 protein in 63 primary invasive breast cancers and their corresponding metastatic lymph nodes

| Primary breast cancer | Metastatic lymph nodes | Total | P value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive (n) | Negative (n) | |||

| Positive | 48 | 1 | 49 | |

| Negative | 12 | 2 | 14 | 0.003 |

| Total | 60 | 3 | 63 | |

* McNemar’s χ2 test

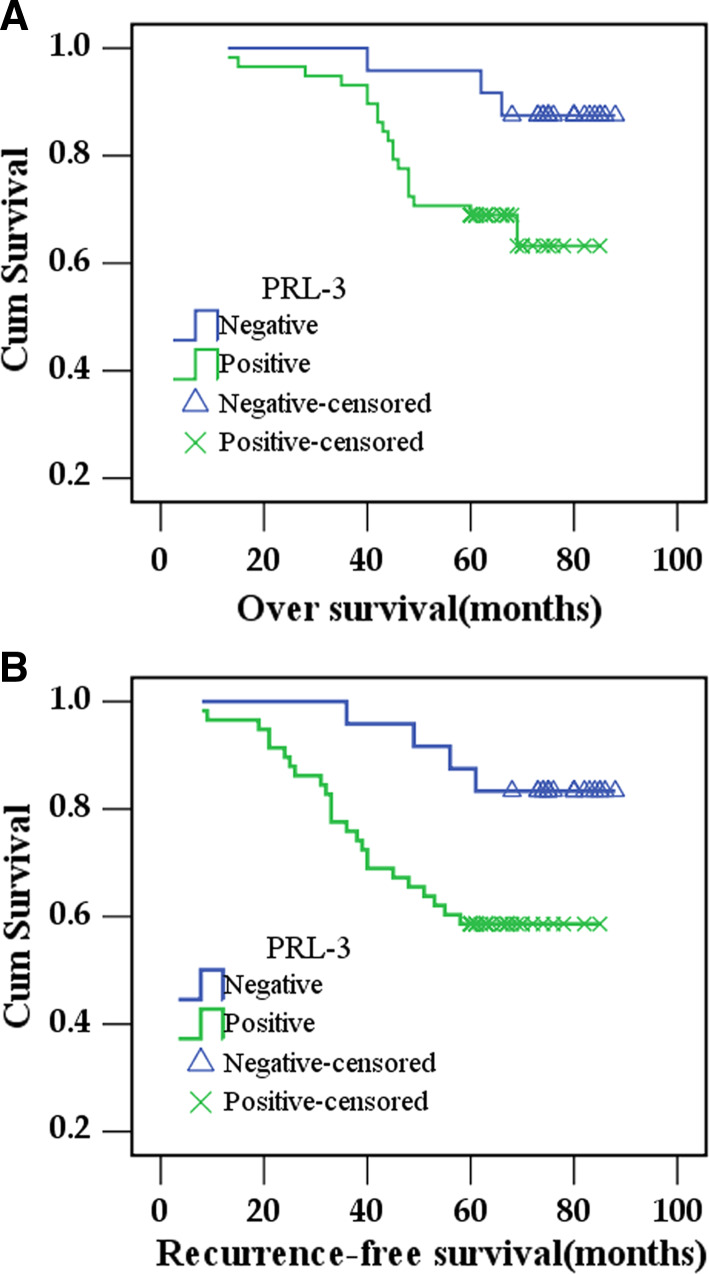

Prognostic significance of PRL-3 expression

Kaplan–Meier curves for survival are shown in Fig. 2. Patients with positive expression of PRL-3 showed a significantly shorter OS [70.3 ± 2.9 months (95% CI, 64.7–76) vs. 84 ± 2.3 months (95% CI, 79.5–88.5), respectively, log-rank test, P = 0.033; Fig. 2a] and RFS [63.9 ± 3.5 months (95% CI, 57.1–70.7) vs. 81.6 ± 3.0 months (95% CI, 76.0–87.6), respectively. log-rank test, P = 0.024, Fig. 2b] than patients with negative expression of PRL-3. In Cox regression for OS including patients’ age, clinical stage, tumor size, lymph node metastasis, hormonal status, Her-2 status, and PRL-3 expression. Univariate analyses identified clinical stage (P = 0.007), lymph node metastasis (P = 0.049), Her-2 status (P = 0.003), PRL-3 positive expression (P = 0.045) as predictors for poor outcome. Multivariate analyses of these variables indicated that only clinical stage (P = 0.007) and Her-2 status (P = 0.040) remained as independent prognostic factors (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates for OS time and RFS with respect to PRL-3 expression in breast cancer. a OS time stratified by PRL-3 expression, log-rank test, P = 0.033. b RFS time stratified by PRL-3 expression, log-rank test, P = 0.024

Table 3.

Prognostic factors in Cox Proportional Hazards Model

| Parameter | Univariate | Multivariate | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P | 95% CI | HR | P | 95% CI | HR | |

| Over survival | ||||||

| Tumor size | 0.119 | 0.815–5.995 | 2.211 | |||

| Clinical stage | 0.007* | 1.407–8.520 | 3.462 | 0.007* | 1.423–9.144 | 3.607 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.049* | 1.008–55.819 | 7.500 | 0.132 | 0.625–36.962 | 4.805 |

| ER status | 0.398 | 0.617–3.378 | 1.443 | |||

| Her-2 status | 0.003* | 1.561–8.943 | 3.737 | 0.040* | 1.044–6.331 | 2.571 |

| PRL-3 expression | 0.045* | 1.026–12.029 | 3.512 | 0.096 | 0.828–10.032 | 2.882 |

| Recurrence-free survival | ||||||

| Tumor size | 0.016* | 1.243–8.614 | 3.273 | 0.245 | 0.651–5.367 | 1.869 |

| Clinical stage | 0.033* | 1.078–6.010 | 2.546 | 0.028* | 1.118–7.252 | 2.848 |

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.024* | 1.348–73.121 | 9.929 | 0.148 | 0.579–37.284 | 4.647 |

| ER status | 0.144 | 0.827–3.698 | 1.749 | |||

| Her-2 status | 0.000* | 2.110–9.813 | 4.550 | 0.006* | 1.388–7.345 | 3.193 |

| PRL-3 expression | 0.034* | 1.093–9.107 | 3.155 | 0.040* | 1.055–9.349 | 3.140 |

* Statistically significant (Cox regression). HR hazard ratio; CI confidence interval

Multivariate analysis of recurrence

Cox regression proportional hazards models were used to estimate the impact of PRL-3 expression on RFS. Univariate analysis showed that the PRL-3 expression was associated with a poor RFS (P = 0.034), a finding further supported by multivariate analysis (P = 0.040). Multivariate Cox regression was performed for each prognostic factors to calculate hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals. The model was simplified in a stepwise fashion by removing variables that had a P value > 0.05. The only three variables that remained statistically significant as independent predictors of the recurrence in the multivariate analysis were PRL-3 expression, Her-2 status, Clinical stage. The hazard ratio (95% confidence intervals; P value) of the PRL-3 expression, Her-2 status, clinical stage were 3.140 (1.055–9.349; 0.040), 3.193 (1.388–7.345; 0.006), 2.848 (1.118–7.252; 0.028), respectively (Table 3).

PRL-3 mRNA expression in human breast cancer tissues

We first examined PRL-3 mRNA expression in all of the 45 cases of breast cancer tissues, 15 cases of normal tissues, 20 cases of matched metastatic lymph nodes and 15 cases of adenoma tissues by semiquantitative RT-PCR. Various levels of PRL-3 mRNA expression were shown in Figs. 3 and 4. After semiquantitative, statistical analysis showed that the level of PRL-3 mRNA expression significantly higher in malignant tissues compared with benign tissues or matched normal tissues. The PRL-3 mRNA expression level was increased in primary breast cancer specimens (0.741 ± 0.198) as compared with paired normal tissues (0.451 ± 0.166) or adenoma tissues (0.562 ± 0.157), P = 0.000 and 0.001, respectively. The PRL-3 mRNA level in metastatic lymph nodes was significantly higher compared with the corresponding primary tumor (0.961 ± 0.110 vs. 0.842 ± 0.191, P = 0.022) (Fig. 5). Furthermore, the level of PRL-3 mRNA expression was significantly higher in breast cancer with LNM (0.842 ± 0.191) than in breast cancer without LNM (0.661 ± 0.167). The difference was also significant (P = 0.002) (Table 4).

Fig. 3.

Expression of PRL-3 mRNA in different specimens. M marker, 1 breast cancer tissue, 2 metastatic lymph node, 3 normal breast tissues, 4 breast fibroadenoma. β1, β2, β3 and β4 are their corresponding β-actin

Fig. 4.

Boxplots comparing the relative expression of PRL-3 mRNA in different specimens. A breast cancer tissues, B normal breast tissues, C breast fibroadenoma, D metastatic lymph nodes

Fig. 5.

The difference of PRL-3 mRNA expression in different specimens. A breast cancer tissues and normal breast tissues, B breast cancer tissues and breast fibroadenoma, C breast cancer tissue with lymph node metastasis and without lymph node metastasis, D matched metastatic lymph nodes and the corresponding breast cancer tissue

Table 4.

Association between PRL-3 mRNA expression and clinicopathological variables in invasive breast cancer patients

| Variables | No. of cases | PRL-3mRNA (mean ± SD) | U value | P value* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| <50 | 22 | 0.750 ± 0.207 | 242.0 | 0.803 |

| ≥50 | 23 | 0.733 ± 0.194 | ||

| Tumor size (cm) | ||||

| <2 | 21 | 0.713 ± 0.190 | 214.0 | 0.387 |

| ≥2 | 24 | 0.766 ± 0.206 | ||

| Clinical stage | ||||

| I/II | 33 | 0.746 ± 0.205 | 192.0 | 0.878 |

| III | 12 | 0.729 ± 0.186 | ||

| Lymph node status | ||||

| Positive | 20 | 0.842 ± 0.191 | 117.0 | 0.002 |

| Negative | 25 | 0.661 ± 0.167 | ||

| ER | ||||

| Positive | 31 | 0.713 ± 0.210 | 153.0 | 0.117 |

| Negative | 14 | 0.804 ± 0.159 | ||

| PR | ||||

| Positive | 29 | 0.703 ± 0.196 | 159.0 | 0.083 |

| Negative | 16 | 0.810 ± 0.189 | ||

| Her-2 | ||||

| Positive | 9 | 0.825 ± 0.170 | 116.0 | 0.192 |

| Negative | 36 | 0.721 ± 0.202 | ||

* P value obtained from the Mann–Whitney U test

Relationship between PRL-3 protein expression and PRL-3 mRNA expression

Immunohistochemical analysis and RT-PCR were used to determine the expression levels of PRL-3 protein and PRL-3 mRNA in paraffin-embedded tissues and their corresponding fresh specimens from 45 patients, respectively. High PRL-3 protein expression was observed in 30 (66.7%) of 45 tumor samples, while, the frequency of high PRL-3 mRNA expression was observed in 32 (71.1%) of 45 cases of tumor samples. According to the results, a concordance rate of 91.1% was found between the expressions of PRL-3 protein and PRL-3 mRNA (kappa = 0. 793) (Table 5) .

Table 5.

Relationship between PRL-3 protein expression and PRL-3 mRNA expression

| Immunohistochemistry | RT-PCR | Total | kappa value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| + | − | |||

| + | 29 | 1 | 30 | |

| − | 3 | 12 | 15 | 0.793 |

| Total | 32 | 13 | 45 | |

Discussion

PRL-3 is a newly identified protein tyrosine phosphatase associated with tumor metastasis. Enhanced expression of the PRL-3 promotes the acquisition of cellular properties that confer tumorigenic and metastatic abilities (Kozlov et al. 2004; Rouleau et al. 2006; Zeng et al. 2003). Upregulation of PRL-3 is associated with the progression and eventual metastasis of several types of human cancer (Li et al. 2007; Miskad et al. 2004, 2007; Saha et al. 2001). Indeed, PRL-3 shows promise as a biomarker and prognostic indicator in some malignant tumors (Li et al. 2005, 2006; Miskad et al. 2007; Wang et al. 2008). However, the substrates and molecular mechanisms of action of the PRL-3 have remained elusive. Recent findings indicate that PRL-3 may function in regulating cell adhesion structures to effect epithelial-mesenchymal transition (Wang et al. 2007a). The identification of PRL-3 substrates is a key to understand their roles in cancer progression and exploiting their potential as exciting new therapeutic targets for cancer treatment.

We assessed PRL-3 protein expression in 82 invasive breast cancer tissues by using immunohistochemistry. Positive expression of PRL-3 was found in 58 of 82 (70.7%) invasive breast cancer tissues. Radke et al. (2006) determined that high PRL-3 expression was occurred in 111 of 147 (75.5%) cases of invasive breast cancer. While Wang et al. (2006) reported that 34.8% of 382 operable primary breast cancers expressed a high level of PRL-3. The two studies all investigated that PRL-3 expression did not correlate with some important clinicopathological features such as hormone receptor status and lymph node involvement. However, in our study, the expression of PRL-3 was positive correlated with lymph node metastasis. The expression of PRL-3 with lymph node metastasis was 77.8% and it was 47.4% without lymph node metastasis in breast cancer tissues (χ2 = 6.521, P = 0.011; OR = 3.889, 95% CI = 1.322–11.438). The discrepancy may be due to regional differences, and the limited number of specimens analyzed, and the specificity of the antibody or the criteria for evaluation. Our immunohistochemical examination also revealed that high expression of PRL-3 was significantly more frequently detected in lymph node metastases, as compared to that in the matched primary breast cancer tissue (95.2 vs. 77.8%; P = 0.003), and this finding is consistent with Radke’s reports (91.7 vs. 66.7%; P = 0.033). The above evidences indicate that the abnormality of its expression may play a direct and indirect role in LNM of breast cancer.

PRL-3 mRNA expression previously has been analyzed in other carcinomas, in particular, in colorectal cancer (Bardelli et al. 2003; Saha et al. 2001). Radke et al. (2006) also found that PRL-3 mRNA expression was significantly higher in neoplastic compared with non-neoplastic breast cancer tissue specimens (mean 1.015 ± 0.156 vs. 0.898 ± 0.089, P = 0.010). In present study, our findings are consistent with the report. Not only that, PRL-3 mRNA is expressed in significantly higher frequency in human invasive breast cancer with lymph node metastasis than in those without lymph node metastasis (mean 0.842 ± 0.191 vs. 0.661 ± 0.167, P = 0.001). What’s more, the concordance rate of the expression between PRL-3 protein and PRL-3 mRNA was 91.1%. In a word, these results further confirm the potential role of PRL-3 in promoting lymph node metastasis of invasive breast cancer.

The formation of nodal and distant metastases following the development of neoplasia is a multistep process. It requires the neoplastic cell to detach itself from the primary lesion, migrate through the extracellular matrix, and invade the vascular or lymphatic system. Neoplastic cells may invade lymphatics directly or may initially invade the vascular system. Recently, many researches demonstrate that PRL-3 might play a causative role in tumor-related angiogenesis (Guo et al. 2004, 2006; Parker et al. 2004; Rouleau et al. 2006; Zhao et al. 2008). Therefore, while PRL-3 promotes the angiogenesis of breast cancer, it also enhances the infiltration and lymph node metastasis of the cancer cells. The possible mechanisms could be that the abundant blood vessels increase the opportunity for cancer cells to enter into blood circulation system as well as the concomitant lymphatic vessels. In a word, overexpression of PRL-3 might facilitate tumor cells to invade into lymphatics or vasculature, and therefore, being a prerequisite for development of local lymph node and distant metastases.

As all know, a substantial number of breast cancer patients eventually die from relapse or metastasis. Therefore, searching for new prognostic indicators that are able to sort out those patients at high risk of relapse is extremely important. PRL-3 has been the focus of much interest as a possible prognostic marker in a wide range of carcinomas (Kato et al. 2004; Li et al. 2007; Miskad et al. 2007; Peng et al. 2004). In this study, patients with PRL-3 negative tumors had substantially longer OS and RFS than did patients with PRL-3 positive tumors. But, multivariate analysis showed that positive PRL-3 expression was not an independent marker for OS in the entire population after adjusting for other prognostic factors. However, multivariate analysis also revealed PRL-3 positive expression as independent prognostic factor for RFS. Thus, our results indicate that PRL-3 is expected to be a promising biomarker for predicting invasive breast cancer patients who were at an increased risk of recurrence. In conclusion, PRL-3 as a potential molecular target for the treatment of breast cancer that may decrease recurrent risk and improve prognosis.

In addition to its role in predicting metastasis and recurrence of human invasive breast cancer, PRL-3 has a potential value of being a candidate for metastasis tailored therapies. However, the process of metastasis is highly complex. It is the result of the accumulation of gene mutations and expression change in different places and times, rather than the alteration of a single gene. Although some potential mechanisms of PRL-3 in promoting tumor cells migration and invasion have been reported by several studies (Basak et al. 2008; Fiordalisi et al. 2006; Peng et al. 2006). Further experiments will be required to clarify the exact molecular mechanism through which PRL-3 influences cancer metastasis.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Xiu-Ling Wu (Department of Pathology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical College, Wenzhou) for his valuable input, and Ms. Li Wan for her technical assistance.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no one has conflicts of interests with the study presented.

Abbreviations

- PRL-3

Phosphatase of regenerating liver-3

- RT-PCR

Reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction

- LNM

Lymph node metastasis

- OR

Odds ratio

- OS

Overall survival

- RFS

Recurrence free survival

References

- Bardelli A, Saha S, Sager JA, Romans KE, Xin B, Markowitz SD, Lengauer C, Velculescu VE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B (2003) PRL-3 expression in metastatic cancers. Clin Cancer Res 9:5607–5615 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basak S, Jacobs SB, Krieg AJ, Pathak N, Zeng Q, Kaldis P, Giaccia AJ, Attardi LD (2008) The metastasis-associated gene Prl-3 is a p53 target involved in cell-cycle regulation. Mol Cell 30:303–314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cates CA, Michael RL, Stayrook KR, Harvey KA, Burke YD, Randall SK, Crowell PL, Crowell DN (1996) Prenylation of oncogenic human PTP(CAAX) protein tyrosine phosphatases. Cancer Lett 110:49–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers AF, Groom AC, MacDonald IC (2002) Dissemination and growth of cancer cells in metastatic sites. Nat Rev Cancer 2:563–572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond RH, Cressman DE, Laz TM, Abrams CS, Taub R (1994) PRL-1, a unique nuclear protein tyrosine phosphatase, affects cell growth. Mol Cell Biol 14:3752–3762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiordalisi JJ, Keller PJ, Cox AD (2006) PRL tyrosine phosphatases regulate rho family GTPases to promote invasion and motility. Cancer Res 66:3153–3161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo K, Li J, Tang JP, Koh V, Gan BQ, Zeng Q (2004) Catalytic domain of PRL-3 plays an essential role in tumor metastasis: formation of PRL-3 tumors inside the blood vessels. Cancer Biol Ther 3:945–951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo K, Li J, Wang H, Osato M, Tang JP, Quah SY, Gan BQ, Zeng Q (2006) PRL-3 initiates tumor angiogenesis by recruiting endothelial cells in vitro and in vivo. Cancer Res 66:9625–9635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kato H, Semba S, Miskad UA, Seo Y, Kasuga M, Yokozaki H (2004) High expression of PRL-3 promotes cancer cell motility and liver metastasis in human colorectal cancer: a predictive molecular marker of metachronous liver and lung metastases. Clin Cancer Res 10:7318–7328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov G, Cheng J, Ziomek E, Banville D, Gehring K, Ekiel I (2004) Structural insights into molecular function of the metastasis-associated phosphatase PRL-3. J Biol Chem 279:11882–11889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Guo K, Koh VW, Tang JP, Gan BQ, Shi H, Li HX, Zeng Q (2005) Generation of PRL-3- and PRL-1-specific monoclonal antibodies as potential diagnostic markers for cancer metastases. Clin Cancer Res 11:2195–2204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Zhan W, Wang Z, Zhu B, He Y, Peng J, Cai S, Ma J (2006) Inhibition of PRL-3 gene expression in gastric cancer cell line SGC7901 via microRNA suppressed reduces peritoneal metastasis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 348:229–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li ZR, Wang Z, Zhu BH, He YL, Peng JS, Cai SR, Ma JP, Zhan WH (2007) Association of tyrosine PRL-3 phosphatase protein expression with peritoneal metastasis of gastric carcinoma and prognosis. Surg Today 37:646–651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu YQ, Li HX, Lou X, Lei JY (2008) Expression of phosphatase of regenerating liver 1 and 3 mRNA in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Arch Pathol Lab Med 132:1307–1312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marx J (2001) Cancer research. New insights into metastasis. Science 294:281–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matter WF, Estridge T, Zhang C, Belagaje R, Stancato L, Dixon J, Johnson B, Bloem L, Pickard T, Donaghue M et al (2001) Role of PRL-3, a human muscle-specific tyrosine phosphatase, in angiotensin-II signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 283:1061–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskad UA, Semba S, Kato H, Yokozaki H (2004) Expression of PRL-3 phosphatase in human gastric carcinomas: close correlation with invasion and metastasis. Pathobiology 71:176–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miskad UA, Semba S, Kato H, Matsukawa Y, Kodama Y, Mizuuchi E, Maeda N, Yanagihara K, Yokozaki H (2007) High PRL-3 expression in human gastric cancer is a marker of metastasis and grades of malignancies: an in situ hybridization study. Virchows Arch 450:303–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker BS, Argani P, Cook BP, Liangfeng H, Chartrand SD, Zhang M, Saha S, Bardelli A, Jiang Y, St Martin TB et al (2004) Alterations in vascular gene expression in invasive breast carcinoma. Cancer Res 64:7857–7866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L, Ning J, Meng L, Shou C (2004) The association of the expression level of protein tyrosine phosphatase PRL-3 protein with liver metastasis and prognosis of patients with colorectal cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 130:521–526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng L, Jin G, Wang L, Guo J, Meng L, Shou C (2006) Identification of integrin alpha1 as an interacting protein of protein tyrosine phosphatase PRL-3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 342:179–183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polato F, Codegoni A, Fruscio R, Perego P, Mangioni C, Saha S, Bardelli A, Broggini M (2005) PRL-3 phosphatase is implicated in ovarian cancer growth. Clin Cancer Res 11:6835–6839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian F, Li YP, Sheng X, Zhang ZC, Song R, Dong W, Cao SX, Hua ZC, Xu Q (2007) PRL-3 siRNA inhibits the metastasis of B16-BL6 mouse melanoma cells in vitro and in vivo. Mol Med 13:151–159 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radke I, Gotte M, Kersting C, Mattsson B, Kiesel L, Wulfing P (2006) Expression and prognostic impact of the protein tyrosine phosphatases PRL-1, PRL-2, and PRL-3 in breast cancer. Br J Cancer 95:347–354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rouleau C, Roy A, St Martin T, Dufault MR, Boutin P, Liu D, Zhang M, Puorro-Radzwill K, Rulli L, Reczek D et al (2006) Protein tyrosine phosphatase PRL-3 in malignant cells and endothelial cells: expression and function. Mol Cancer Ther 5:219–229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Bardelli A, Buckhaults P, Velculescu VE, Rago C, St Croix B, Romans KE, Choti MA, Lengauer C, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B (2001) A phosphatase associated with metastasis of colorectal cancer. Science 294:1343–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Peng L, Dong B, Kong L, Meng L, Yan L, Xie Y, Shou C (2006) Overexpression of phosphatase of regenerating liver-3 in breast cancer: association with a poor clinical outcome. Ann Oncol 17:1517–1522 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Quah SY, Dong JM, Manser E, Tang JP, Zeng Q (2007a) PRL-3 down-regulates PTEN expression and signals through PI3K to promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Cancer Res 67:2922–2926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Li ZF, He J, Li YL, Zhu GB, Zhang LH, Li YL (2007b) Expression of the human phosphatases of regenerating liver (PRLs) in colonic adenocarcinoma and its correlation with lymph node metastasis. Int J Colorectal Dis 22:1179–1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, He YL, Cai SR, Zhan WH, Li ZR, Zhu BH, Chen CQ, Ma JP, Chen ZX, Li W, Zhang LJ (2008) Expression and prognostic impact of PRL-3 in lymph node metastasis of gastric cancer: its molecular mechanism was investigated using artificial microRNA interference. Int J Cancer 123:1439–1447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X, Zeng H, Zhang X, Zhao Y, Sha H, Ge X, Zhang M, Gao X, Xu Q (2004) Phosphatase of regenerating liver-3 promotes motility and metastasis of mouse melanoma cells. Am J Pathol 164:2039–2054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q, Hong W, Tan YH (1998) Mouse PRL-2 and PRL-3, two potentially prenylated protein tyrosine phosphatases homologous to PRL-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 244:421–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q, Si X, Horstmann H, Xu Y, Hong W, Pallen CJ (2000) Prenylation-dependent association of protein-tyrosine phosphatases PRL-1, -2, and -3 with the plasma membrane and the early endosome. J Biol Chem 275:21444–21452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng Q, Dong JM, Guo K, Li J, Tan HX, Koh V, Pallen CJ, Manser E, Hong W (2003) PRL-3 and PRL-1 promote cell migration, invasion, and metastasis. Cancer Res 63:2716–2722 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao WB, Li Y, Liu X, Zhang LY, Wang X (2008) Evaluation of PRL-3 expression, and its correlation with angiogenesis and invasion in hepatocellular carcinoma. Int J Mol Med 22:187–192 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]