Abstract

Background

Steatotic liver grafts are excluded for partial liver transplantation due to increased risk of primary non-function. Mechanisms underlying the failure of fatty partial liver grafts (FPG) remain unknown. This study investigated whether inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) plays a role in failure of FPG.

Methods

Fatty livers were induced by feeding rats a high-fat high-fructose (HFFr) diet for 2-weeks. Hepatic triglyceride was ~9-fold higher in rats fed the HFFr diet than those fed a low-fat low-fructose diet. Lean and fatty liver explants were reduced in size ex vivo to ~1/3, stored in the UW solution for 2 h, and implanted.

Results

Post-transplantational hepatic iNOS expression and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) formation (nitrite/nitrate levels and 3-nitrotyrosine adducts) increased more profoundly in FPG than in lean partial grafts (LPG). Serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and bilirubin were 2-and 5.5-fold higher after transplantation of FPG than LPG. 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine incorporation was 25% in LPG but only 5% in FPG, and graft weight increased by 64% in LPG while remaining unchanged in FPG. All rats that received FPG died, whereas all those receiving LPG survived. 1400W (5 μM), a specific iNOS inhibitor, largely blunted the production of RNS, prevented the elevation of ALT and bilirubin, restored liver regeneration and improved survival of FPG. Mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase-IV, ATP synthase-β and NADH dehydrogenase-3 decreased markedly in FPG, and these effects were blocked by 1400W.

Conclusion

Thus, hepatic steatosis causes failure of partial liver grafts, most likely by increasing RNS that leads to mitochondrial damage and dysfunction.

Keywords: fatty liver, iNOS, mitochondria, partial liver transplantation, 1400W

INTRODUCTION

To alleviate the severe shortage of donor livers, partial liver transplantation and use of marginal donor livers have increased in recent years (1-3). Survival and function of partial liver grafts after liver transplantation (LT) depend highly on the relative graft mass implanted. When a graft volume-to-standard liver volume ratio is less than 30-40%, so-called “small-for-size grafts,” survival decreases significantly (4,5). Graft quality also affects the outcome of transplantation. After liver resection and full-size LT, steatosis is associated with a higher mortality (6-10). Severe steatotic livers are rejected universally for transplantation. Donor livers with moderate steatosis are considered for transplantation only in the absence of other known risk factors (9). The risk of mild steatosis in transplantation is controversial (11,12). Due to the potential increased risks of graft failure due to small graft size and hepatic steatosis, fatty livers, which account for 26% to 50% of potential donor livers (13,14), are currently excluded for use in partial LT. However, a recent observation showed that adiponectin combined with FTY720, an anti-inflammatory drug, improved survival of small-for-size fatty liver grafts, suggesting that successful transplantation of FPG might be possible should appropriate precautionary treatment be given (15).

Understanding the mechanisms underlying the failure of FPG would help to develop effective therapy to improve the survival of FPG. Previous studies showed that reactive oxygen species (ROS) increase after transplantation of steatotic full-size liver grafts as well as small-for-size lean liver grafts (16,17). However, the effects of reactive nitrogen species (RNS) in LT remain controversial (18). RNS could cause cytotoxicity by inhibiting mitochondrial respiration, protein synthesis, gluconeogenesis, and the activity of a variety of important enzymes (19,20). By contrast, NO precursor administration decreases, whereas endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)-deficiency enhances graft injury after LT (18,21). Inhalation of NO during LT accelerates restoration of liver function following transplantation (22). Therefore, NO can be protective or injurious, depending on the context of the physiological or pathological process, the amount, timing and location of NO production. eNOS is usually cell protective by mediating vasodilatation, whereas iNOS frequently mediates cytotoxicity (19). Expression of iNOS is up-regulated after partial hepatectomy (23) and in steatotic rat livers after ischemia (24). However, the impact of iNOS in transplantation of FPG remains unknown. Accordingly, this study was designed to test the effects of N-(1-naphtyl)ethylendiamine dihydrochloride (1400W), a specific iNOS inhibitor, on mitochondrial function and graft injury after transplantation of FPG.

METHODS

Induction of Hepatic Steatosis

Male Lewis rats (100-125 g) were fed a high-fat high-fructose diet (HFFr diet; 50% of calories from corn oil, 30% from fructose and 20% from protein) or a low-fat low-fructose control diet (control diet; 12% calorie from corn oil, 68% from starch and 20% from protein) for 2 weeks. Rats accessed foods at libitum. In some rats, the food was weighted daily to assess food consumption. Daily energy intakes were not statistically different between the rats fed the HFFr diet and those fed the control diet.

Partial Liver Transplantation

Under ether anesthesia, the median lobe and the left lateral lobe were removed after ligation with 4-0 suture, and then the liver was explanted as described (17,25). This technique decreases liver mass by ~2/3. Venous cuffs prepared from 14-gauge intravenous catheters were placed over the subhepatic vena cava and the portal vein in vitro. Reduced-size liver explants were weighed and stored in UW solution at 0–1°C for 2 hours. In the treatment group, 1400W (Cayman Co., Ann Arbor, Michigan) was dissolved in the UW storage solution at a concentration of 5 μM.

For implantation, the suprahepatic and subhepatic vena cava and portal vein of the recipient were clamped and the liver was removed (25). The donor explants were rinsed with 5 mL of lactated Ringer’s solution with or without 1400W (5 μM), and implanted as described (17,25). The hepatic artery and the bile duct were anastomosed with intraluminal splints. Blood vessels were clamped for 18 to 20 minutes during surgery, and implantation required less than 50 minutes in total. For sham operation, the abdominal wall was closed with running suture 50 min after opening of the abdomen without transplantation. Rats were observed for 7 days postoperatively for survival. All animals were given humane care in compliance with institutional guidelines using protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Measurement of Serum Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT), Total Bilirubin and Nitrite/Nitrate

Blood samples were collected at 24 and 48 h after implantation. Serum ALT and total bilirubin were determined by analytical kits from Pointe Scientific (Uncoln Park, MI) to evaluate liver injury and function. To assess NO production, serum nitrite and nitrate were determined using an analytic kit from Cayman Chem. (Ann Arbor, MI).

Histology

To assess hepatic steatosis, livers were harvested, frozen-sectioned and stained with Oil-Red-O staining after feeding rats with the control or the HFFr diet for 2 weeks and at 48 h after implantation. At 48 h after sham or implantation surgery, livers were harvested under nembutal anesthesia (50 mg/kg, i.p.), and slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H+E). Images were captured using a Universal Imaging Image-1/AT image acquisition and analysis system (West Chester, PA) with an Axioskop 50 microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY) and a 10x objective lens. Mitotic cells were counted in 10 randomly selected fields under the light microscope.

Immunohistochemistry

Our previous studies showed that after partial liver transplantation, 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU)-labeling started at ~18 h (26). BrdU-incorporation increased gradually in 24 h, and peaked at about 38 to 48 h. Therefore, we compared cell proliferation at 48 h after liver transplantation in this study. In order to detect cells synthesizing DNA, BrdU was injected (100 mg/kg i.p.) 1 h prior to liver harvesting. Immunohistochemistry of BrdU was performed as described elsewhere (25). BrdU-positive and negative cells were counted in 10 randomly selected fields under the light microscope using a 40x objective lens.

To detect 3-nitrotyrosine adducts (3-NT), a marker of peroxynitrite formation, rehydrated liver sections were heated in 10 mM citrate acid (pH 6) in microwave for antigen retrieval. Slides were then exposed to rabbit anti-nitrotyrosine polyclonal antibodies (Upstate Biotec.) at a concentration of 1:150 for 30 min at room temperature.

Hepatic Triglyceride Measurement

Liver tissue (200 mg) was homogenized in normal saline and extracted with 2:1 chloroform/methanol mixture. After centrifugation at 1700 rpm for 5 min, the chloroform phase was separated, dried in a speed vacuum centrifuge and re-suspended in 1 ml of chloroform. Two hundred μl of sample was dried again and the residual was dissolved in 200 μl of isopropanol with 1% Triton X-100. Triglyceride was measured using an analytical kit from Enzymatic Standbio (Boerne, TX).

Western Blotting

Immunoblotting of proteins was performed as described (27) with primary antibodies specific for iNOS (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA), eNOS (Santa Cruz Biotech, Santa Cruz, CA), ATP synthase-β (Abcam Inc. Cambridge, MA), cytochrome c oxidase-IV (COX IV) and NADH dehydrogenase-3 (ND3, Invitrogen Corp., Carlsbad, CA) at a concentration of 1:1000 and actin (ICN, Costa Mesa, CA) at a concentration of 1:3000 at 4°C overnight, respectively. Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies were applied, and detection was by chemiluminescence (Pierce Biotec., Rockford, IL).

Statistical Analysis

Groups were compared using Kaplan-Meier test or ANOVA plus a Student-Newman-Keuls posthoc test, as appropriate. Data shown are means ± S.E.M.. Differences were considered significant at p<0.05.

RESULTS

High-Fat High-Fructose Diet Causes Hepatic Steatosis

American diets are characterized of high-fat and high-fructose intake (28,29). Therefore, in this study, we investigated whether a HFFr diet causes hepatic steatosis. Fig 1 shows the Oil-Red-O-stained liver sections from rats fed either a control or a HFFr diet for 2 weeks (n = 4 per group). Livers from rats fed the control diet revealed sparse distribution of small red fat droplets within hepatocytes (Fig. 1A, upper left). By contrast, livers from rats fed the HFFr diet showed widespread deposition of red fat globules of different sizes in hepatocytes. Steatosis is moderate with fat droplets occurring in about 40-50% of hepatocytes and is mainly microvesicular mixed with scattered macrovesicular fat droplets (Fig. 1A upper right). Corresponding with these histopathologic features of steatosis, a 9-fold increase in hepatic triglycerides was detected in rats fed the HFFr diet compared to those fed the control diet (Fig 1B, n = 4 per group). These results show that the HFFr diet causes overt hepatic steatosis in as short as 2 weeks, thus providing a convenient non-alcoholic fatty liver model for use in these studies.

Fig. 1. High-Fat High-Fructose Diet Caused Hepatic Steatosis.

Rats were fed a low-fat low-fructose control diet (Control) or a high-fat high-fructose diet (HFFr) for 2 weeks. Livers were harvested for Oil-Red-O staining to detect fat droplets (A) just before transplantation (Before Tx; upper panels) or at 48 h after transplantation of FPG from HFFr-fed rats (After Tx; lower panels). Bar is 10 μm. Hepatic triglycerides just before liver transplantation were detected colorimetrically (B). **, p< 0.01 vs the control group.

At 48 h after liver transplantation, widespread red fat globules still existed in FPG regardless with or without 1400W-treatment (Fig. 1A. lower left and right; n = 4 per group). Therefore, 1400W did not affect steatosis after transplantation.

Upregulation of iNOS and Overproduction of RNS after Transplantation of FPG

To investigate if iNOS increases after transplantation of FPG, expression of iNOS was detected by Western blotting (Fig. 2A, n = 4 per group). iNOS is undetectable in livers from sham-operated rats and increased slightly after transplantation of LPG from rats fed the control diet (Fig. 2A). After transplantation of FPG, expression of iNOS increased markedly compared to sham-operated lean livers or transplanted LPG (Fig. 2A). By contrast, eNOS was expressed in livers of sham-operated rats at high levels (Fig. 2A, n = 4 per group). After partial liver transplantation, eNOS increased only slightly in both LPG and FPG. Increases of eNOS were in a similar extent in both LPG and FPG (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. Upregulation of iNOS and Increased RNS Production after Transplantation of FPG.

Livers were collected 48 h after sham-operation (Sham) or transplantation of lean or fatty partial liver grafts. A: inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) were detected by Western blotting. Serum nitrite and nitrate values at 24 and 48 h after surgery are shown in B. a, p< 0.05 vs sham-operation; b, p< 0.05 vs LPG, and c, p< 0.05 vs FPG. Hepatic 3-NT was detected immunohistochemically (C). Panels are: upper left, liver from sham-operated rats; upper right, LPG; lower left, FPG; lower right, FPG treated with 1400W. Bar is 50 μm.

Since iNOS increased substantially in FPG, we investigated whether RNS increased correspondingly. Basal levels of nitrite and nitrate were 6 μM in sham-operated rats which increased slightly after sham-operation (Fig. 2B, n = 4). Transplantation of LPG increased peak serum nitrite and nitrate to 65 μM (Fig. 2B, n = 4). By contrast, serum nitrite and nitrate increased to 113 μM after transplantation of FPG (Fig. 2B, n = 5), indicating higher NO production. Increases of nitrite and nitrate after transplantation of FPG were blunted by 1400W to a level similar to LPG (Fig. 2B, n = 4).

NO reacts with superoxide radicals forming peroxynitrite, a highly reactive RNS. 3-NT, an indicator of peroxynitrite production, was barely detectable in livers from sham-operated rats (Fig. 2C. upper left, n = 4). 3-NT increased in implanted LPG (Fig. 2C. upper right, n = 4). However, after transplantation of FPG, 3-NT increased to levels substantially higher than in LPG (Fig. 2C. lower left, n = 4). Formation of 3-NT in FPG was largely blocked by inhibition of iNOS activity with 1400W (Fig. 2C. lower right, n = 4). Together the data indicate that iNOS expression and RNS formation increased dramatically in FPG. Inhibition of iNOS activity prevents this excessive RNS formation.

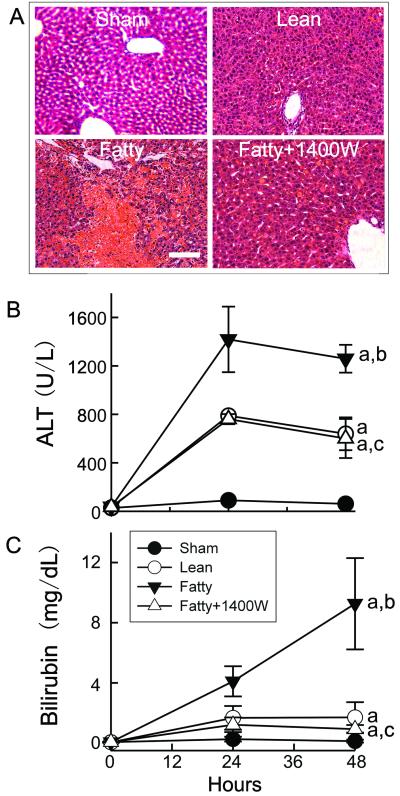

Inhibition of iNOS Attenuates Injury of FPG after Transplantation

No pathological changes were observed in lean livers after sham operation (Fig. 3A, upper left, n = 4). After transplantation of LPG, scattering necrosis and eosinophilic inclusions in hepatocytes were observed (Fig. 3A, upper right, n = 4). By contrast, in transplanted FPG, focal necrosis was overt, mainly in the periportal and midzonal regions of the liver lobules (Fig. 3A. lower left, n = 4). Inhibition of iNOS with 1400W decreased necrosis in FPG (Fig. 3A. lower right, n = 4).

Fig. 3. 1400W Prevented Injury and Improved Function of FPG.

Livers were collected 48 h after sham-operation (Sham) or transplantation of LPG and FPG. A shows the images of H+E stained liver slides. Panels are: upper left, liver from sham-operated rats; upper right, LPG; lower left, FPG; lower right, FPG pretreated with 1400W. Bar is 50 μm. Blood was collected at 24 h and 48 h after transplantation. ALT (B) and total bilirubin (C) in sera were measured. a, p< 0.05 vs sham-operation; b, p< 0.05 vs LPG, and c, p< 0.05 vs FPG.

Graft injury was also assessed by the release of ALT into the blood (n = 4 per group). Serum ALT levels were 60-90 U/L in rats before and after sham operation (Fig. 3B). ALT increased to ~780 U/L at 24 h after transplantation of LPG and slightly decreased to 640 U/L at 48 h (Fig. 3B). Peak ALT increased further to ~1420 U/L after transplantation of FPG, indicating a more severe liver injury. Inhibition of iNOS by 1400W decreased peak ALT in rats received FPG to ~760 U/L, a level similar to that of the LPG group (Fig. 3B).

Total bilirubin was 0.12-0.25 mg/dL in rats before and after sham operation (n = 3). In rats received LPG, bilirubin increased to1.7 mg/dL at 24 h and maintained at the same level at 48 h after transplantation (Fig. 3C, n = 4). In rats that received FPG, however, bilirubin increased to 4 mg/dL at 24 h and 9.3 mg/dL at 48 h (n = 4). 1400W decreased peak bilirubin to 1.2 mg/dL in rats received FPG (Fig. 3C, n = 4). Thus, liver injury is more severe and graft function is poorer in FPG compared to LPG, and inhibition of iNOS attenuates injury and improves function of FPG.

Inhibition of iNOS Improves Regeneration of FPG after Transplantation

Liver regeneration, a process that is critical for graft survival after partial LT, was evaluated at 48 h after transplantation (Fig. 4, n = 4 per group). Synthesis of DNA in hepatocytes, an indicator of entry to the S-phase of the cell cycle, was assessed by BrdU incorporation. BrdU-positive cells were about 0.05% in sham-operated lean livers and increased to 25% in LPG (Fig. 4A, B and E). By contrast, BrdU labeling was only 5% in FPG (Fig. 4C and E), indicating suppression of cell proliferation. 1400W restored BrdU incorporation in FPG to ~32% (Fig. 4D and E). Mitotic index (MI), the number of hepatocytes undergoing mitosis, was 0.05% in sham-operated rats but increased to 5% in LPG (Fig. 4F). By contrast, MI was as low as 0.1% in FPG (Fig. 4F). 1400W increased MI in FPG to 7% (Fig. 4F). Graft weight increased by 64% in LPG after transplantation but only by 5% in FPG. 1400W treatment increased graft weight gain to 66% in FPG (Fig. 4G). Together, steatosis suppressed liver regeneration after partial LT and this effect was blocked by inhibition of iNOS activity.

Fig. 4. 1400W Improved Regeneration of FPG.

Livers were collected 48 h after sham-operation (Sham) or transplantation of LPG and FPG. 5-Bromo-2′-deoxyuridine (BrdU) incorporation was detected immunohistochemically (A to D). BrdU-positive and –negative cells (E) as well as mitotic and non-mitotic cells (F) were counted in 10 randomly selected fields in a blinded manner. Partial grafts were weighed before implantation and 48 h later to calculate graft weight increases (G). a, p< 0.05 vs sham-operation; b, p< 0.05 vs LPG, and c, p< 0.05 vs FPG.

Inhibition of iNOS Improved Survival of FPG after Transplantation

All rats survived after sham operation (data not shown) or transplantation of LPG (Fig. 5, n = 8). By contrast, survival decreased to 0% after transplantation of FPG (Fig. 5, n = 10). Death occurred in the first 4 days after LT. However, in rats received FPG treated with 1400W, survival reached 80% (Fig. 5, n = 10). These results indicate clearly that inhibition of iNOS effectively prevented failure of FPG after LT.

Fig. 5. 1400W Improved Survival of FPG.

Conditions were as in Fig. 1. Rats were observed 7 days for survival after sham operation or transplantation of LPG and FPG. Difference is statistically significant as assessed by the Kaplan-Meier test (p<0.05) between FPG with and without 1400W-treatment.

Decreases of Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation (OXPHOS) Proteins after Transplantation of FPG: Prevention by 1400W

Sufficient energy supply is crucial for graft survival, liver regeneration and recovery of graft function after LT. Accordingly, mitochondrial OXPHOS enzymes were detected to evaluate mitochondrial function after LT (n = 4 per group). COX-IV, a nuclear DNA (nDNA)-encoded OXPHOS enzyme, decreased by 60% in FPG 48 h after LT compared to sham-operated livers (Fig. 6A and B). ATP synthase-β (AS-β), another nDNA-encoded OXPHOS and a subunit of the Complex V of the respiratory chain, was not altered in LPG but decreased by 58% in FPG (Fig. 6A and C). ND3, a subunit of the Complex I which is encoded by mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), decreased 47% in FPG but not altered in LPG (Fig. 6A and D). Inhibition of iNOS by 1400W recovered COX IV, AS-β and ND3 to 94%, 104% and 87% of the basal levels, respectively, indicating that RNS produced by iNOS play an important role in decreases of OXPHOS enzymes in FPG.

Fig. 6. 1400W Prevented Decreases of Mitochondrial Oxidative Phosphorylation Proteins in FPG.

Livers were harvested 48 h after transplantation. Representative images of cytochrome c oxidase IV (COX IV), ATP synthase-β (AS-β), and NADH dehydrogenase-3 (ND3) detected by immunoblotting are shown in A and quantification of images by densitometry is shown in B, C and D. a, p<0.05 vs sham; b, p<0.05 vs LPG and c, p<0.05 vs FPG.

DISCUSSION

Non-Alcoholic Hepatic Steatosis Increases Liver Injury and Suppresses Regeneration after Partial LT

Living donor and split LT has developed rapidly in recent years due to the severe shortage of donor organs (1-3). Currently only grafts with “perfect” quality are used for partial LT with reasonable confidence of immediate function following implantation (30). Fatty liver is the most common hepatic disorder in humans. Hepatic steatosis was found in 26% to 50% of potential liver donors (13,14). Since steatosis increases liver failure after LT and liver resection (6-9), severe steatotic grafts are not accepted for use in LT although a recent study suggested that due to the urgent need of liver grafts, severely steatotic grafts should no longer be discarded (31). Donor livers with moderate steatosis would be considered for LT only in the absence of any other known risk factors (9). The risk of mild steatosis in transplantation is controversial in that some studies show that mild steatosis does not affect the clinical outcome of full-size LT while others show that even mild steatosis is associated with graft dysfunction (11,12,32). Because the fear that partial liver grafting and hepatic steatosis would additively or synergistically increase the risk of graft failure, it was proposed that livers with more than 10% steatosis should be excluded as donors in living donor LT (13). Since liver steatosis is highly associated with obesity, potential donors with high body mass index (BMI) are usually not evaluated for living liver donation (33). Animal studies on transplantation of FPG are rare. Some studies showed that fatty livers induced by high-fat diet decreased survival after partial LT (34,35). Therefore, fatty liver not only limits the usable donor pool for full-size LT but also for partial LT. It is clear, therefore, that we urgently need to understand how steatosis increases failure of partial liver grafts so that strategies can be developed to increase the use of fatty grafts for partial LT.

In this study we induced non-alcoholic hepatic steatosis by feeding a HFFr diet. Many etiologies cause hepatic steatosis, including alcohol consumption, obesity, diabetes mellitus, metabolic disorders, malnutrition or over-nutrition, drugs, and viral hepatitis (36). Westernized diets are well known to contain high fat contents. In recent years, fructose intake increased rapidly due to the use of high fructose corn syrup as a sweetener in a variety of food products (28,29). Individual consumption of fructose increased 125-fold between 1970 and 1997 (28,29). Fructose is a readily absorbed and metabolized, highly energetic and lipogenic nutrient (28,29). Although addition of fructose to diets or high fat diets alone are known to cause fatty liver; it usually takes a relatively long time (4 to 8 weeks) of treatment (34,35,37,38). In this study, we found that a diet containing both high fat and high fructose causes overt hepatic steatosis in rats within only 2 weeks (Fig. 1). A mixed micro- and macrovesicular steatosis developed in ~50% of hepatocytes. Thus, high fructose and high fat intake synergistically stimulate hepatic steatosis, providing a convenient and clinically relevant model for study of fatty LT.

Using this model, we compared the outcome of transplantation of lean and steatotic partial liver grafts. Our previous study showed that lean half-size liver grafts are viable whereas survival of lean quarter-size grafts cold-stored for 6 h decreased substantially (17). In this study we compared the outcome of lean and fatty liver grafts of one-third size with a shorter cold storage time (2 h). Under these conditions, liver injury occurred after transplantation of LPG (Fig. 3) but these grafts were able to regenerate (Fig. 4) and survive (Fig. 5). By contrast, liver injury was more severe, regeneration was largely suppressed, and survival decreased markedly in FPG compared to LPG (Figs. 3 - 5). These results show clearly that non-alcoholic hepatic steatosis compromises the outcome of partial LT.

Overproduction of RNS Plays an Essential Role in Failure of FPG

The mechanism by which steatosis increases failure of partial liver grafts remains unclear. Here we investigated whether overproduction of RNS plays a role. Effects of NO production on liver injury in hepatic ischemia/reperfusion (IR) and LT have been controversial (18,39). Although iNOS is required for liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy in mice (40), excessive NO causes DNA damage, leading to accumulation of p53 and p21Cip1 and cell cycle arrest (41). At appropriate concentrations, NO protects against IR injury and improves graft survival after LT. For example, NO precursor and inhalation of NO during surgery decreases graft injury after LT (18,22). Liver injury is more severe in eNOS-deficient mice after full-size LT (21), suggesting that NO production by eNOS is protective in full-size LT. However, many studies have shown that eNOS is cell protective whereas iNOS mediates cytotoxicity (19). Inhibition of iNOS decreased hepatic IR injury (18,39,42). Expression of iNOS is up-regulated after partial hepatectomy (23) and in steatotic livers exposed to normothermic ischemia (24). These phenomenons suggest that coexistence of steatosis and partial LT could synergistically up-regulate iNOS. Indeed, in this study iNOS increased overtly in FPG after transplantation which was associated with dramatic increases of RNS production (Fig. 2). Mechanisms leading to higher expression of iNOS in FPG remain unclear. iNOS can be upregulated by TNFα and ROS (43). It is well known that TNFα and ROS production increase in fatty livers and obesity (44-46). Our previous study also showed that TNFα and ROS production increases substantially in small-for-size liver grafts after partial liver transplantation (17). It is possible that steatosis and partial liver transplantation additively or synergistically increase TNFα and ROS formation thus stimulating iNOS expression. Importantly, 1400W, a specific iNOS inhibitor that decreases activity of iNOS, largely blocked RNS production in FPG (Fig. 2), and inhibition of iNOS attenuated injury, improved regeneration and increased survival of FPG (Figs. 3 - 5). These data show clearly that overproduction of RNS by iNOS plays an important role in failure of FPG.

Overproduction of RNS Causes Mitochondrial Damage in FPG

Mitochondrial function is essential for survival of liver grafts after LT (25,47). ATP production decreased substantially in small-for-size liver grafts (26) and in fatty livers before and after IR (32,48). Thus, FPG faces multiple challenges after LT: extra energy is needed to support liver regeneration whereas more severe injury and poorer mitochondrial function may occur. The roles of RNS in mitochondrial function are also controversial. NOS inhibitors prevent the MPT onset in astrocytes caused by IR (49), whereas NO donors protect hepatocytes and cardiac myocytes from onset of the MPT (50,51) and cardiac myocyte-specific expression of iNOS protects against IR-induced MPT onset (52).

In susceptible cells, RNS could cause cytotoxicity by direct interaction with mitochondrial targets. For example, RNS inhibits cytochrome c oxidase and mitochondrial respiration (19,20). Sepsis induces mitochondrial production of RNS and compromises mitochondrial function in wild-type but not in iNOS knockout mice (53,54). Long-term feeding of a high fat diet induces iNOS, suppresses mitochondrial respiration and decreases mitochondrial membrane potential in the liver (55). In diabetic rats, increased iNOS expression leads to peroxynitrite-dependent protein nitration and liver mitochondrial damage (56). Increased expression of iNOS by pro-inflammatory cytokines or adenoviral delivery of iNOS gene causes mitochondrial damage and cell death (57). In this study, we showed that both nDNA-encoded and mtDNA-encoded mitochondrial OXPHOS proteins decreased substantially in FPG, indicating mitochondrial damage and dysfunction (Fig. 6). Inhibition of iNOS largely blocks RNS formation and the decrease of mitochondrial OXPHOS proteins, which was associated with attenuation of liver injury and improvement of liver regeneration. These data suggest that excessive production of RNS in FPG damages mitochondrial OXPHOS proteins and/or inhibits mitochondrial biogenesis. Mitochondrial damage and dysfunction are responsible for, at least in part, the failure of FPG.

In summary, this study shows that hepatic steatosis and partial LT synergistically increases RNS production, which leads to mitochondrial damage and graft failure. Inhibition of iNOS effectively prevents excessive RNS production, decreases injury and enhances the regeneration of FPG. Therefore, iNOS inhibitors could be a promising therapy to improve the outcome of transplantation of FPG thus enlarging the usable donor pool.

ABBREVIATIONS

- ALT

alanine aminotransferase

- AS-β

ATP synthase-β

- ATP

adenosine 5′-triphosphate

- BrdU

5-bromo-2′-deoxyuridine

- CsA

cyclosporin A

- COX-IV

cytochrome c oxidase-IV

- CypD

cyclophilin D

- eNOS

endothelial nitric oxide synthase

- FPG

fatty partial grafts

- HFFr

high-fat high-fructose

- hpf

high power field

- iNOS

inducible nitric oxide synthase

- IR

ischemia/reperfusion

- LPG

lean partial grafts

- LT

liver transplantation

- MPT

mitochondria permeability transition

- ND3

NADH dehydrogenase-3

- NO

nitric oxide

- 3-NT

3-nitrotyrosine adducts

- OXPHOS

oxidative phosphorylatory proteins

- PCNA

proliferating cell nuclear antigen

- RNS

reactive nitrogen species

- UW solution

University of Wisconsin cold storage solution

- 1400W

N-(1-naphtyl)ethylendiamine dihydrochloride

Footnotes

SQH and HR participated in the performance of the research; ZZ participated in the research design; ZZ, GLW and SQH participated in the writing of the paper.

Supported, in part, by Grants DK70844, DK037034 and C06 RR015455 from the National Institute of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hashimoto K, Miller C. The use of marginal grafts in liver transplantation. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2008;15:92–101. doi: 10.1007/s00534-007-1300-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Renz JF, Emond JC, Yersiz H, Ascher NL, Busuttil RW. Split-liver transplantation in the United States: outcomes of a national survey. Ann Surg. 2004;239:172–181. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000109150.89438.bd. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Strong RW. Living-donor liver transplantation: an overview. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Surg. 2006;13:370–377. doi: 10.1007/s00534-005-1076-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sugawara Y, Makuuchi M, Takayama T, et al. Small-for-size grafts in living-related liver transplantation. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:510–513. doi: 10.1016/s1072-7515(01)00800-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kiuchi T, Kasahara M, Uryuhara K, et al. Impact of graft size mismatching on graft prognosis in liver transplantation from living donors. Transplantation. 1999;67:321–327. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199901270-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Behrns KE, Tsiotos GG, DeSouza NF, Krishna MK, Ludwig J, Nagorney DM. Hepatic steatosis as a potential risk factor for major hepatic resection. J Gastrointest Surg. 1998;2:292–298. doi: 10.1016/s1091-255x(98)80025-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mittler J, Pascher A, Neuhaus P, Pratschke J. The utility of extended criteria donor organs in severely ill liver transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2008;86:895–896. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e318186ad7a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nocito A, El-Badry AM, Clavien PA. When is steatosis too much for transplantation? J Hepatol. 2006;45:494–499. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urena MA, Moreno GE, Romero CJ, Ruiz-Delgado FC, Moreno SC. An approach to the rational use of steatotic donor livers in liver transplantation. Hepatogastroenterology. 1999;46:1164–1173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sun Z, Klein AS, Radaeva S, et al. In vitro interleukin-6 treatment prevents mortality associated with fatty liver transplants in rats. Gastroenterology. 2003;125:125–215. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(03)00696-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marsman WA, Wiesner RH, Rodrigues L, et al. Use of fatty donor liver is associated with diminished early patient and graft survival. Transplantation. 1997;62:1246–1251. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199611150-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strasberg SM, Howard TK, Molmenti EP, Hertl M. Selecting the donor liver: Risk factors for poor function after orthotopic liver transplantation. Hepatology. 1994;20:829–838. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840200410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rinella ME, Alonso E, Rao S, et al. Body mass index as a predictor of hepatic steatosis in living liver donors. Liver Transpl. 2001;7:409–414. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.23787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Urena MA Garcia, Ruiz-Delgado F Colina, Moreno GE, et al. Hepatic steatosis in liver transplant donors: common feature of donor population? World J Surg. 1998;22:837–844. doi: 10.1007/s002689900479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Man K, Zhao Y, Xu A, et al. Fat-derived hormone adiponectin combined with FTY720 significantly improves small-for-size fatty liver graft survival. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:467–476. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2005.01201.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong Z, Connor HD, Froh M, et al. Polyphenols from Camellia sinenesis prevent primary graft failure after transplantation of ethanol-induced fatty livers from rats. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;36:1248–1258. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhong Z, Connor HD, Froh M, et al. Free radical-dependent dysfunction of small-for-size rat liver grafts: prevention by plant polyphenols. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:652–664. doi: 10.1016/j.gastro.2005.05.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shah V, Kamath PS. Nitric oxide in liver transplantation: pathobiology and clinical implications. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:1–11. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.36244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Anggard E. Nitric oxide: mediator, murderer, and medicine. Lancet. 1994;343:1199–1206. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92405-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen T, Zamora R, Zuckerbraun B, Billiar TR. Role of nitric oxide in liver injury. Curr Mol Med. 2003;3:519–526. doi: 10.2174/1566524033479582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theruvath TP, Zhong Z, Currin RT, Ramshesh VK, Lemasters JJ. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase protects transplanted mouse livers against storage/reperfusion injury: Role of vasodilatory and innate immunity pathways. Transplant Proc. 2006;38:3351–3357. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2006.10.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lang JD, Jr., Teng X, Chumley P, et al. Inhaled NO accelerates restoration of liver function in adults following orthotopic liver transplantation. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:2583–2591. doi: 10.1172/JCI31892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Carnovale CE, Scapini C, Alvarez ML, Favre C, Monti J, Carrillo MC. Nitric oxide release and enhancement of lipid peroxidation in regenerating rat liver. J Hepatol. 2000;32:798–804. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80249-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Koeppel TA, Mihaljevic N, Kraenzlin B, et al. Enhanced iNOS gene expression in the steatotic rat liver after normothermic ischemia. Eur Surg Res. 2007;39:303–311. doi: 10.1159/000104401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhong Z, Theruvath TP, Currin RT, Waldmeier PC, Lemasters JJ. NIM811, a Mitochondrial Permeability Transition Inhibitor, Prevents Mitochondrial Depolarization in Small-for-Size Rat Liver Grafts. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:1103–1111. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.01770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhong Z, Schwabe RF, Kai Y, et al. Liver regeneration is suppressed in small-for-size liver grafts after transplantation: involvement of JNK, cyclin D1 and defective energy supply. Transplantation. 2006;82:241–250. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000228867.98158.d2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rehman H, Connor HD, Ramshesh VK, et al. Ischemic preconditioning prevents free radical production and mitochondrial depolarization in small-for-size rat liver grafts. Transplantation. 2008;85:1322–1331. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31816de302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bray GA, Nielsen SJ, Popkin BM. Consumption of high-fructose corn syrup in beverages may play a role in the epidemic of obesity. Am J Clin Nutr. 2004;79:537–543. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/79.4.537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Basciano H, Federico L, Adeli K. Fructose, insulin resistance, and metabolic dyslipidemia. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2005;2:5. doi: 10.1186/1743-7075-2-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rela M, Vougas V, Muiesan P, et al. Split liver transplantation: King’s College Hospital experience. Ann Surg. 1998;227:282–288. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199802000-00019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McCormack L, Petrowsky H, Jochum W, Furrer K, Clavien PA. Hepatic steatosis is a risk factor for postoperative complications after major hepatectomy: a matched case-control study. Ann Surg. 2007;245:923–930. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000251747.80025.b7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Selzner M, Clavien PA. Fatty liver in liver transplantation and surgery. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:105–113. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Trotter JF. Thin chance for fat people (to become living donors) Liver Transpl. 2001;7:415–417. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2001.24933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ye S, Han B, Dong J. Reduced-size orthotopic liver transplantation with different grade steatotic grafts in rats. Chin Med J (Engl ) 2003;116:1141–1145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morioka D, Kubota T, Sekido H, et al. Prostaglandin E1 improved the function of transplanted fatty liver in a rat reduced-size-liver transplantation model under conditions of permissible cold preservation. Liver Transpl. 2003;9:79–86. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2003.36845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Teli MR, James OF, Burt AD, Bennett MK, Day CP. The natural history of nonalcoholic fatty liver: a follow-up study. Hepatology. 1995;22:1714–1719. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ackerman Z, Oron-Herman M, Grozovski M, et al. Fructose-induced fatty liver disease: hepatic effects of blood pressure and plasma triglyceride reduction. Hypertension. 2005;45:1012–1018. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000164570.20420.67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Koteish A, Diehl AM. Animal models of steatosis. Semin Liver Dis. 2001;21:89–104. doi: 10.1055/s-2001-12932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Urakami H, Abe Y, Grisham MB. Role of reactive metabolites of oxygen and nitrogen in partial liver transplantation: lessons learned from reduced-size liver ischaemia and reperfusion injury. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol. 2007;34:912–919. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2007.04640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rai RM, Lee FY, Rosen A, et al. Impaired liver regeneration in inducible nitric oxide synthasedeficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:13829–13834. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.23.13829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chao JI, Kuo PC. Role of p53 and p38 MAP kinase in nitric oxide-induced G2/M arrest and apoptosis in the human lung carcinoma cells. Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:645. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Isobe M, Katsuramaki T, Hirata K, Kimura H, Nagayama M, Matsuno T. Beneficial effects of inducible nitric oxide synthase inhibitor on reperfusion injury in the pig liver. Transplantation. 1999;68:803–813. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199909270-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kleinert H, Boissel J-P, Schwarz PM, Forstermann U. Regulation of the expression of nitric oxide synthase isoforms. In: Ignarro LJ, editor. Nitric Oxide, Biology and Pathobiology. Academic Press; San Diego: 2000. pp. 105–128. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Diehl AM. Tumor necrosis factor and its potential role in insulin resistance and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2004;8:619–638. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2004.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zhong Z, Connor H, Stachlewitz RF, et al. Role of free radicals in primary non-function of marginal fatty grafts from rats treated acutely with ethanol. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52:912–919. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.5.912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Byrne CD, Olufadi R, Bruce KD, Cagampang FR, Ahmed MH. Metabolic disturbances in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease. Clin Sci. 2009;116:539–564. doi: 10.1042/CS20080253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Theruvath TP, Zhong Z, Pediaditakis P, et al. Minocycline and N-methyl-4-isoleucine cyclosporin (NIM811) mitigate storage/reperfusion injury after rat liver transplantation through suppression of the mitochondrial permeability transition. Hepatology. 2008;47:236–246. doi: 10.1002/hep.21912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Selzner N, Selzner M, Jochum W, mann-Vesti B, Graf R, Clavien PA. Mouse livers with macrosteatosis are more susceptible to normothermic ischemic injury than those with microsteatosis. J Hepatol. 2006;44:694–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2005.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reichert SA, Kim-Han JS, Dugan LL. The mitochondrial permeability transition pore and nitric oxide synthase mediate early mitochondrial depolarization in astrocytes during oxygen-glucose deprivation. J Neurosci. 2001;21:6608–6616. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-17-06608.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kim JS, Ohshima S, Pediaditakis P, Lemasters JJ. Nitric oxide protects hepatocytes against mitochondrial permeability transition-induced reperfusion injury. Hepatology. 2004 doi: 10.1002/hep.20197. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dedkova EN, Blatter LA. Characteristics and function of cardiac mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase. J Physiol. 2008 doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.165423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.West MB, Rokosh G, Obal D, et al. Cardiac myocyte-specific expression of inducible nitric oxide synthase protects against ischemia/reperfusion injury by preventing mitochondrial permeability transition. Circulation. 2008;118:1970–1978. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.791533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Escames G, Lopez LC, Tapias V, et al. Melatonin counteracts inducible mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction in skeletal muscle of septic mice. J Pineal Res. 2006;40:71–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-079X.2005.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lopez LC, Escames G, Tapias V, Utrilla P, Leon J, cuna-Castroviejo D. Identification of an inducible nitric oxide synthase in diaphragm mitochondria from septic mice: its relation with mitochondrial dysfunction and prevention by melatonin. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2006;38:267–278. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mantena SK, Vaughn DP, Andringa KK, et al. High fat diet induces dysregulation of hepatic oxygen gradients and mitochondrial function in vivo. Biochem J. 2009;417:183–193. doi: 10.1042/BJ20080868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ren XY, Li YN, Qi JS, Niu T. Peroxynitrite-induced protein nitration contributes to liver mitochondrial damage in diabetic rats. J Diabetes Complications. 2008;22:357–364. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Holohan C, Szegezdi E, Ritter T, O’Brien T, Samali A. Cytokine-induced beta-cell apoptosis is NO-dependent, mitochondria-mediated and inhibited by BCL-XL. J Cell Mol Med. 2008;12:591–606. doi: 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2007.00191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]