Abstract

This Classic article is a translation by M.O. Heller, W.R. Taylor, N. Aslanidis, and Georg N. Duda of the original work by Julius Wolff, Zur Lehre von der Fracturenheilung (supplemental materials are available with the online version of CORR). An accompanying biographical sketch on Julius Wolff is available at DOI 10.1007/s11999-010-1258-z. A second Classic article is available at DOI 10.1007/s11999-010-1239-2. An accompanying Editorial is available at DOI 10.1007/s11999-010-1238-3. The Classic Article is ©1873 and is reprinted from Wolff J. Zur Lehre von der Fracturenheilung. Langenbeck’s Archives of Surgery. 1873;2.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s11999-010-1240-9) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

In the third volume of the second issue of this journal, Professor König in Rostock attempted to deliver proof that two of the observations supporting my line of argument concerning the new growth of trabeculae adapted to their tensile or compressive usage and the resorption of statically unnecessary trabeculae after fractures, have become “obsolete, for one of them at least does not speak in favor of my teachings, whereas the other apparently proves the opposite of that, which I had tried to prove.” Both of the observations mentioned relate to two specimens in the collection of the Rostock Surgical Hospital, which I, with the kind permission of Professor König, presented to the surgical section of the Rostock Natural Science Conference.

During the joyous festivities of the Rostock Convention, I had not been able to create drawings of the relevant specimens, or even to write down as much as a note concerning them. This is why, in my reference regarding those specimens, I avoided any attempt at describing them and merely said—as I could with certainty recall—that I have demonstrated the two points in Rostock as supporting my theory.

Based on my remark, Professor König has chosen to attach a photolithograph of one of those specimens to his work in the third volume of this issue. Supposedly “one glance will suffice to convince anybody impartial that the broken trabeculae of the upper and lower fraction of the bone have simply been glued together in the unchanged form they had before the fracture.” A glance at an image of both fragments, after having been set back into the original position before the fracture, should “not need any further comment and should make even the most avid supporters of the theory on new growth of tensile and compressive trabeculae admit that in this case there is no such new growth, but rather a bonding of the old broken trabeculae in a crude scar.”

What Professor König has described here could, in my opinion, appear correct at a first glance of the reproduced specimen. After careful consideration, however, it appears that further commentary on the specimen is required, and in attempting to deliver this commentary, I myself hope to convince even the most ardent opponents of my theory that, what Professor König has completely overlooked, is that even in the present case, in the upper fragment of the bone, a change of old tensile and compressive trabeculae into new ones, adapted to the changed statics, has taken place.

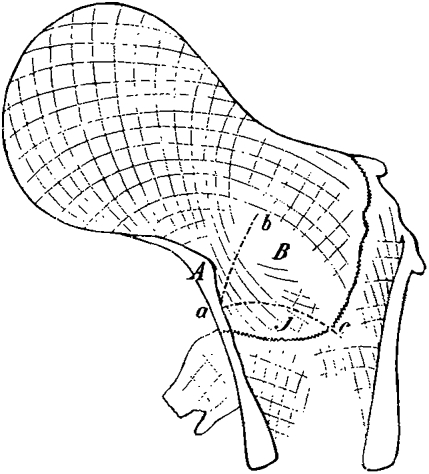

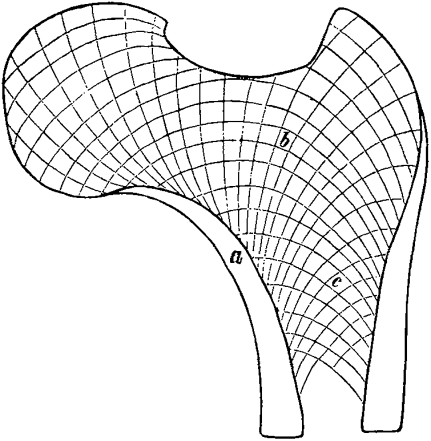

Figure 1 is a schematic reproduction of König’s photolithograph number e, drawn by me with the greatest care possible, which shows the fragments after having been reset into the position they had held before the fracture. In comparison, Fig. 2 shows a schematic reproduction of a normal femur specimen, the same one I had used several times in my work to illustrate normal conditions and is shown in volume 14 for the Archive for Clinical Surgery.

Fig. 1.

Schematic reproduction of König’s photolithography number e, Table V of this volume.

Fig. 2.

Schematic reproduction of a normal femur specimen.

While under normal conditions, the cortex is known to become more and more narrow towards the top until it completely disappears, it can be seen in our specimen on the medial or compressive side at point A in Fig. 1, where the wedged end of the cortex of the upper fragment sits on the lower fragment and where, under normal circumstances, the cortex should have already become extraordinarily narrow, it suddenly becomes thicker again. Starting from this thicker point, in region J of Fig. 1, fan-shaped trabeculae have developed at very acute angles that extend downwards and outwards, are somewhat concave on the side towards the greater trochanter, and fan out progressively the further down they reach.

It is now definitely possible to prove that these described trabeculae could not have been present before the fracture and that they must have developed slowly, after the bonding process of the fractured ends had already taken place through the inflammatory callus concurrently with the destruction of previously present trabeculae.

A comparison with Fig. 2 shows us that, before the bone had been broken in the region of point A in Fig. 1, two types of trabeculae must have been present, the orientation and curvature of which was definitely different from those just described, ie, tensile trabeculae, indicated by the dotted line ac, which rise up from a lower point on the lateral side, bend their convex curvature towards the top and end in a right angle close to A, and compressive trabeculae, indicated by the dotted line ab, which fan out at an acute angle from the region of point A and, while turning a slight concave curvature towards the lateral side of the bone, rise up to the neck and the femoral head.

In my work for the Archive for Clinic Surgery, I have repeatedly and in detail pointed out that in a healed fracture of the femoral neck with wedging of the compressed side of the upper fragment into the cancellous bone of the lower one, the findings, as shown in König’s specimen, are rather constant, ie, that in every case, out of the region referred to in König’s specimen as A, fan-shaped trabeculae grow downwards, replacing the now absent normal trabeculae. I would therefore be rather surprised if Professor König had not seen those trabeculae in his specimen and that he persistently claims that in the region of the fracture in his specimen “the old lines,” “the broken trabeculae in their original form” could be found everywhere.

I must also state that the gap B in the femoral neck closely above that part of the upper fragment that lies on the cortex of the lower fragment, which I had remarked upon as a constant occurrence in all those specimens that have healed in a similar fashion to the present one, can also be found again in König’s section, which has been cut out at a place rather close to the middle of the bone, which means that all those changes I had summed up under “calcaneus similarity” in my work, can be found again here. Had Professor König depicted a section cut out from even closer to the middle of the bone between the front and back surfaces of the femur, and which had had, apart from this constant gap, less adjoining random defects than the pictured one, then the characteristic gap B would have been even more obvious.

Regarding the second specimen from the collection of Professor König, I regret to have neither the actual specimen nor a picture of it in front of me now. Professor König says that he had not been able to judge it. It had been cut off so unfavorably that almost only the trochanter and the head were preserved, which means that the lower trabeculae were missing completely, and that “the specimen could be used for neither side as evidence”. I myself believe that regarding this specimen, if my memory does not deceive me, I demonstrated that it is in concordance with the diagnosis of my other specimens.

Having shown above that the upper fragment alone is enough to prove that the change in bone architecture is consistent with my law on fracture healing, it should only be logical that Professor König overlooked those things that to me seemed relevant for this demonstration in this specimen, and that it would be possible to find these things in a second analysis of the specimen.

So much for the justification of my casual reference to the mentioned specimens and for the defense against the accusation that I had not had the right to use these “unfavorable” specimens as evidence towards my theory. Apart from this, I must say that I can only be sincerely grateful if, as Professor König wished, the facts I have presented to support my theory will be verified and plenty of material be gathered for the same purpose and I express many thanks to Professor König for encouraging this.

However, I still must explain the two following points for the discussion of the general applicability of the laws I found regarding the definitive healing of fractures:

First, Professor König has also had doubts about “the absolute power of proof of my specifically described and photographed fracture”. He does not deem it impossible that the fracture on the lateral side had taken place in a region 1.5 cm lower than I had assumed. In that case the direct shift from lateral or tensile trabeculae from the lower to the upper fragment, which can so beautifully be seen in my photograph, and to which I attached so much importance, would be one I had assumed falsely, for in that case the lower parts of the tensile trabeculae, just like the upper parts, would have belonged to the upper fragment from the beginning. Regarding the extraordinary sharpness of the photograph, which in this respect is much more powerful than a photolithography, it is completely incomprehensible to me how such doubt could even exist. I believe that the photograph clearly shows the broken ends of the upper and lower lateral cortex exactly in the position, according to my explanation, where the fracture had taken place. Meanwhile, further discussion of the clarity of my photograph cannot lead to a solution at this point. At the upcoming surgical convention, which will take place here, Professor König will hopefully have a chance to see the photographed specimen as well as the whole actual bone from which it has been taken, and to realize, as I can predict already, that a mistake regarding the place of fracture is impossible.

Secondly and finally, I shall have to clarify the following: König’s pictures show that in his specimen the tensile trabeculae rising from the lateral side of the lower fragment and those rising from the lateral side of the upper fragment do not correspond with each other as is evidently the case in the specimen that has been photographed by me in the Archive for Clinical Surgery and in several other specimens that I myself have described and, as I seem to recall when writing my paper in the previous summer without having mentioned this specifically, that this was also the case in the Rostock specimen.

The question arises whether this fact about the latter specimen should contradict my law of healing. If - as Professor König seems to think not impossible - nature is able to make use of two different paths of healing, one with the restitution of new trabeculae adapted to their usage, as is the case in my photographed specimen and in the many respective observations at the same time relating to ankyloses and to rickets by Martini, Köster and myself, and the other by simple or, as in König’s specimen, at least partially by simple bonding of the old trabeculae.

The answer to this, I believe, is easily explained within my earlier detailed work regarding this topic. There can obviously be only one way for nature to heal bone fractures definitively, ie, with a reconstruction of the bone’s function, by means of recreating statically useful bone trabeculae, adapted to the more or less changed static environment. As has been proven, without statically useful trabeculae, not even the healthy bone could carry out its function, and much less the broken, inflamed bone, that has been out of use for a long time and has been disfigured by adhering callus masses. A simple recreation of the bone’s continuity by gluing of the fracture through the callus is therefore, as I have shown before, not a restoration of the limb’s function and thus not real healing.

Therefore it is obvious, that even without proof of restored functionality, König’s specimen could still not prove anything against my law of healing, even if, as Professor König had incorrectly assumed, there had actually been no new growth of trabeculae adapted to their usage, but merely a bonding of unchanged broken ones.

Professor König does not, however, have any information on the degree of functionality of the bones he depicted. He merely informs us that the specimen originates from an old woman, who had gone on to live for “several years” after the fracture, but fails to deliver the important answer to the question, which alone would have given the specimen an important place in the discussion of the present issue: whether the old woman had been able to walk in the final years of her life.

It is my opinion that König’s specimen should be judged in the following way: the conditions of restitution, as described by my healing law, were in this case, due to the woman’s age, the extraordinarily deep wedging, and the highly changed position of the fragments relative to one other, almost to an acute angle, extremely unfavorable. In spite of this, nature was able not to avoid a pseudarthrosis, and rather to create a callus and to secure fusing of the fragments with each other by creating the “calcaneus similarity” in the upper fragment, without which the callus alone would have not provided any support. To the same extent, however, to which the bone partially lacked adaptation of bone architecture that I have proven to be necessary, the actual healing must have been incomplete, and the function of the limb insufficient.

Berlin, 15th March 1873

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Footnotes

Translated by M.O. Heller, PhD, W.R. Taylor, PhD, N. Aslanidis, and Georg N. Duda, PhD.

Georg N. Duda (✉) Charite, Forschungs Labor der Unfallchirurgie, Augustenburger Platz 1, 13353 Berlin, Germany e-mail: georg.duda@charite.de

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.