Abstract

Objective

Visfatin, a novel adipokine with metabolic and immunoregulatory properties, has been implicated in the regulation of fetal growth, as well as in preterm labor. A gap in knowledge is whether spontaneous labor at term is associated with changes in the maternal and fetal concentrations of visfatin. The aim of this study was to determine if the presence of labor at term is associated with alterations in maternal and neonatal plasma visfatin concentrations.

Study design

This cross-sectional study included 50 normal pregnant women at term and their appropriate-for-gestational age (AGA) neonates in the following groups: 1) 25 mother-neonate pairs delivered by elective cesarean section without spontaneous labor, and 2) 25 mother-neonate pairs who delivered vaginally following spontaneous labor. Maternal plasma and cord blood visfatin concentrations were determined by ELISA. Non-parametric statistics were used for analyses.

Results

1) The median visfatin concentration was higher in umbilical cord plasma of neonates born following a spontaneous labor at term than that of those who were born by an elective cesarean section (p=0.02); 2) in contrast, the median maternal plasma visfatin concentration did not differ significantly between patients with and without labor (p=0.44); and 3) there was a significant correlation between umbilical cord plasma concentration of visfatin and both maternal visfatin concentration (r= 0.54, p=0.005) and gestational age at delivery (r= 0.58; p=0.002) only in the absence of labor.

Conclusion

Term labor is associated with increased fetal, but not maternal, circulating visfatin concentrations. Previous reports indicate that preterm labor leading to preterm delivery is characterized by an increase in maternal plasma concentrations of visfatin. The observations reported herein support the view that there are fundamental differences in the endocrine and metabolic adaptations in normal labor at term and preterm labor.

Keywords: adipokine, cytokine, pregnancy, parturition, cord blood, neonate, energy demands, metabolism, BMI, overweight, obesity

Introduction

Parturition is a high energy-consuming process. This is evidenced by increased concentrations of circulating maternal glucose [30, 32, 86, 87, 104], free fatty acids [20, 104], ketone bodies [18], and lactic acid [44] during parturition. Moreover, there is a 3- to 4-fold increase in whole body glucose utilization during labor and delivery and the energy expenditure of the parturient women in the second stage of labor is 40% higher than that of patients in the first stage [6]. In addition, myometrial glycogen storage, which is significantly increased at term [69], is almost completely depleted during labor [40], further supporting the notion that parturition imposes an increase energy demand on the laboring woman. Similarly, a compelling body of evidence suggests that the energy requirements of the fetus also increase during labor and delivery. Indeed, parturition is associated with an increased fetal blood glucose [86, 87] and the concentrations of this nutrient is significantly higher in the umbilical vein than in umbilical arteries [36], suggesting enhanced fetal usage of this fuel during labor.

However, while the metabolic alterations that accompany labor and delivery are well established, the specific mechanism regulating this physiological response is not completely clear. The conventional view is that labor and delivery can be viewed as a moderate exercise [6, 30] and that similar, albeit not identical, mechanisms are governing the metabolic adaptation to parturition [6, 46, 93]. These mechanisms include non-insulin dependent glucose uptake, increased maternal circulating epinephrine and norepinephrine, enhanced hepatic gluconeogenesis and direct sympathetic nervous system stimulation [6, 46, 93].

It is now well-established that adipokines - hormones produced exclusively and/or abundantly by adipose tissue - play a major role in energy homeostasis during physiologic and pathologic conditions [28, 91], as well as during intense and/or acute physical activities [45, 85]. Adipokines, such as adiponectin [9, 58, 60, 62, 64, 75, 97], resistin [77] and visfatin [65] have been implicated in metabolic adaptations to normal gestation, as well as in complications of pregnancy such as preeclampsia [3, 12, 13, 22, 27, 29, 35, 67, 68, 72, 78, 84, 88, 95, 98, 102], SGA [39, 56, 103] preterm labor and others [38, 52-55, 57, 59, 61, 63, 64, 67, 76, 101].

Visfatin, a newly discovered 52 kDa adipokine, has been implicated in the regulation of glucose hemostasis [94] and it has been proposed that this hormone can play a role in fetal growth [7, 8, 25, 43, 47, 48, 51]. Recently, we have reported that preterm labor is associated with increased maternal circulating concentrations of visfatin [53]. However, it is unknown whether spontaneous labor at term is associated with changes in the maternal and fetal concentrations of visfatin. This study was conducted to address this question.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Population

A cross-sectional study was conducted by searching our clinical database and bank of biological samples and included 50 pregnant women and their neonates in the following groups: 1) 25 normal pregnant women at term in labor and their appropriate-for-gestational age (AGA) neonates; and 2) 25 normal pregnant women at term, who underwent elective cesarean delivery, and their AGA neonates.

Maternal plasma, umbilical cord blood and demographic and clinical data were retrieved from our bank of biological samples and clinical databases. Many of these samples were previously employed to study the biology of inflammation, hemostasis, angiogenesis regulation, adipokines and growth factor concentrations in normal pregnant women and those with pregnancy complications.

All participating women provided written informed consent prior to enrolment and the collection of blood samples. The collection and use of blood for research purposes was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of both the Sotero del Rio Hospital (Santiago, Chile) and the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD; Bethesda, Maryland, USA).

Definitions

The inclusion criteria for normal pregnancy were: 1) no medical, obstetrical or surgical complications; 2) intact membranes; 3) delivery of a term neonate (≥37 weeks) with a birth weight between the 10th and the 90th percentile [19]; and 4) a normal oral 75-g oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation based on the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria [2].

Spontaneous labor was defined as the presence of regular uterine contractions associated with cervical change, occurring at a frequency of at least two every 10 minutes. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated according to the formula: weight (kg)/height (m2). Normal weight women were defined as those with a BMI of 18.5-24.9 kg/m2 according to the definition of the World Health Organization (WHO)[1].

Sample collection and Human Visfatin C-terminal immunoassay

Maternal blood samples were collected after the diagnosis of labor or before the onset of cesarean delivery. Umbilical cord blood was obtained from the umbilical vein at the time of delivery. Blood was centrifuged at 1300 g for 10 minutes at 4°C. The plasma obtained was stored at -80°C until analysis. Concentrations of visfatin in maternal and fetal plasma were determined using specific and sensitive enzyme immunoassays (Phoenix Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Belmont, CA, USA). An initial assay validation was performed in our laboratory prior to the conduction of this study and the detailed description of the assay has been previously published [53, 63, 65, 66]. The calculated inter- and intra-assay coefficients of variation for visfatin C-terminal immunoassays in our laboratory were 5.3% and 2.4%, respectively. The sensitivity was calculated to be 0.04 ng/ml.

Statistical analysis

Normality of the data was tested using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests. Since maternal plasma and umbilical cord blood visfatin concentrations were not normally distributed, Mann-Whitney U tests were used for comparisons of continuous variables between the different groups and Wilcoxon signed-rank test for comparison of visfatin concentrations between mother-neonate pairs. Comparison of proportions was performed by Fisher’s exact test. Spearman rank correlation was utilized to assess correlations between umbilical cord blood visfatin concentrations and birthweight, gestational age at delivery, maternal plasma visfatin concentration, as well as maternal BMI. A p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analysis was performed with SPSS, version 14 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the study groups are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in the demographic and clinical characteristics between the two groups.

Table 1.

Clinical and demographic characteristics of the study population.

| Not in Labor (n=25) |

Spontaneous Labor (n=25) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age (years) | 32 (27 – 35) | 26 (23 – 32) | 0.06 |

| Parity | 1 (0 – 2) | 1 (0 – 1) | 0.8 |

| Pre-gestational BMI (kg/m2) | 24.5 (22.7 – 27.0) | 23.2 (22.3 – 26.0) | 0.3 |

| Overweight/Obese | 11 (44) | 8 (32) | 0.3 |

| Smoking | 1 (4) | 1 (4) | 0.5 |

| GA at delivery (weeks) | 39.0 (38.1 – 40.5) | 39.4 (38.7 – 40.1) | 0.6 |

| Birth weight (grams) | 3560 (3165 – 3685) | 3360 (3255 – 3490) | 0.6 |

| Female neonate | 11 (44) | 16 (64) | 0.1 |

Values expressed as median (interquartile range) of number (%)

GA – Gestational Age; BMI – Body Mass Index

Umbilical cord blood visfatin concentrations in labor vs. no labor

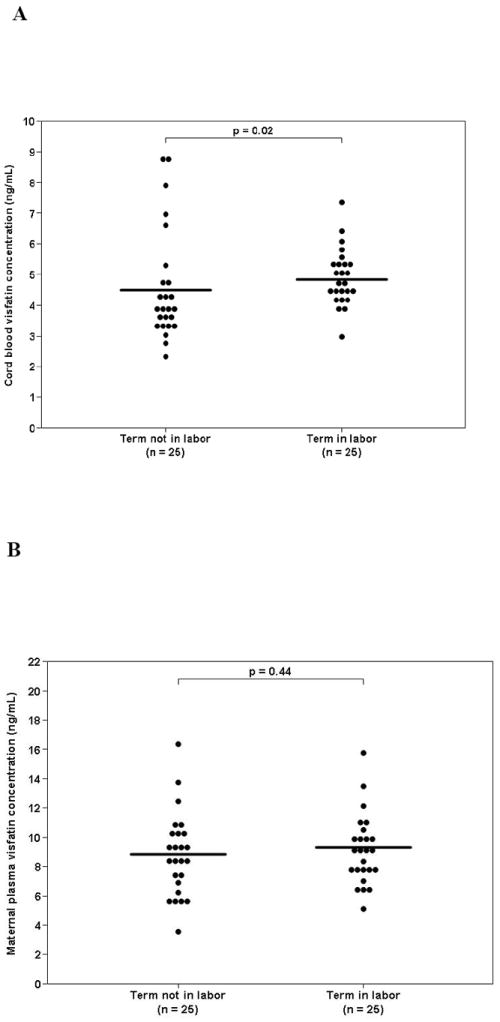

The median visfatin concentration was higher in umbilical cord plasma of neonates born following a spontaneous labor at term than in those who were born by an elective cesarean delivery (4.8 ng/ml, interquartile range [IQR] 4.2-5.3 vs. 3.8 ng/ml, IQR: 3.3-4.7; p=0.02, Figure 1A).

Figure 1. Comparison between visfatin circulating concentrations in the presence and absence of labor in cord blood (A) and maternal plasma (B).

The median visfatin concentration was higher in umbilical cord plasma of neonates born following spontaneous labor at term than in those who were born by an elective cesarean delivery (4.8 ng/ml, interquartile range [IQR] 4.2-5.3 vs. 3.8 ng/ml, IQR: 3.3-4.7; p=0.02). In contrast, the median visfatin concentration in maternal plasma was not significant different between patient with spontaneous labor at term and those who underwent an elective cesarean delivery (8.5 ng/ml, IQR: 6.4-10.3 vs. 9.1 ng/ml, IQR: 7.6-10.0; p=0.44, Figure 1B).

Maternal plasma visfatin concentrations in labor vs. no labor

The median visfatin concentration in maternal plasma did not differ significantly between patients with spontaneous labor at term and that of those who underwent an elective cesarean delivery (8.5 ng/ml, IQR: 6.4-10.3 vs. 9.1 ng/ml, IQR: 7.6-10.0; p=0.44, Figure 1B).

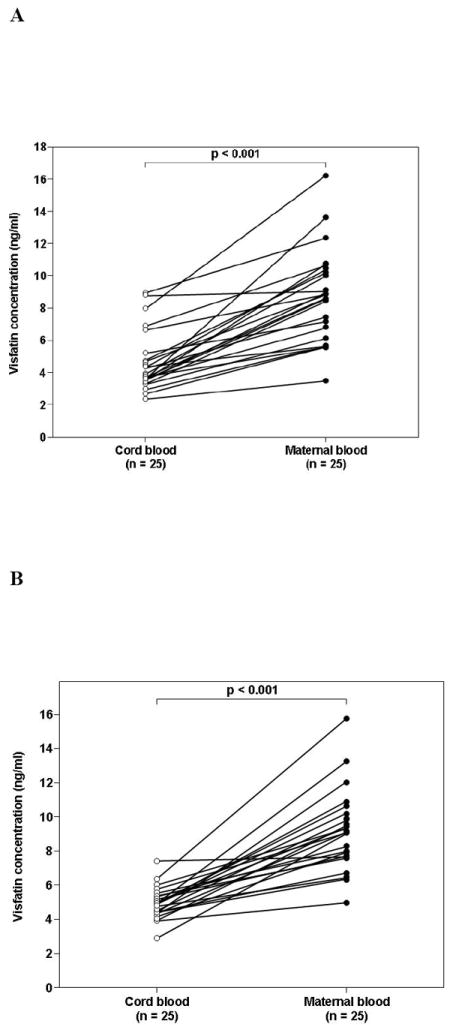

Comparison between maternal plasma and umbilical cord blood visfatin concentrations

The median maternal plasma visfatin concentration was significantly higher than that of umbilical cord blood regardless of the presence (p<0.001, Figure 2A) or absence (p<0.001, Figure 2B) of spontaneous labor.

Figure 2. Comparison between umbilical cord blood and maternal plasma visfatin concentrations in the absence (A) and presence of labor (B).

The median maternal plasma visfatin concentration was higher than in the umbilical blood regardless of the presence or absence of spontaneous labor (p<0.001 for both comparisons).

Maternal-neonatal difference in plasma visfatin (defined as maternal plasma visfatin concentration - umbilical cord blood visfatin concentration) was comparable between mother-neonate pairs in labor and those not in labor (4.4 ng/ml, IQR: 2.4-5.8 vs. 3.8 ng/ml, IQR: 2.6-5.4; p=0.8). In a pooled analysis (including neonates born following spontaneous labor and by cesarean section), there was no significant difference in the median umbilical blood visfatin concentration between males and females (4.4 ng/ml, IQR: 3.5-4.9 vs. 4.4 ng/ml, IQR: 3.9-5.3; p=0.8).

There was a significant correlation between umbilical cord blood concentrations of visfatin and maternal visfatin concentration (r= 0.54, p=0.005), as well as gestational age at delivery (r=0.58; p=0.002) only in the absence of labor. There was no significant correlation between umbilical cord plasma visfatin concentration and birthweight.

Discussion

Principal findings of the study

1) The median visfatin concentration was higher in umbilical cord plasma of neonates born following spontaneous labor at term than in those who were born by an elective cesarean delivery; 2) in contrast, the median maternal plasma visfatin concentration did not differ significantly between patients with and without labor; and 3) there was a significant correlation between umbilical plasma visfatin concentration and both maternal visfatin concentration and gestational age at delivery only in the absence of labor.

The physiological role of visfatin

Visfatin was originally identified as a growth factor for early B cell and thus was termed Pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor (PBEF) [92]. Subsequently, this protein was identified as a 52 kDa adipokine that is preferentially produced by visceral fat depot [94] and the name “visfatin” was coined. The expression of visfatin/ PBEF is not limited to adipose tissue; indeed, its expression has been determined in placenta, fetal membranes [33, 34, 49, 73, 74, 79-82], myometrium,[15] bone marrow, liver, muscle [92], heart, lung, kidney [92], macrophages [14], and neutrophils [26, 92].

Visfatin has been implicated in the regulation of glucose homeostasis, as well as in inflammatory response[94, 100]. Several lines of evidence support the role of this adipokine in metabolic regulation: 1) adipocytes secrete visfatin in response to treatment with glucose [21]; 2) visfatin deficient mice have an impaired glucose tolerance [89]; and 3) a visfatin promoter polymorphism is associated with susceptibility to type-2 diabetes mellitus [106]. The evidence supporting a role for visfatin as an immunomodulator includes the following findings: 1) visfatin synergizes with interleukin (IL)-7 and stem cell factors to promote the growth of B cell precursors; 2) treatment of human monocytes with visfatin results in an increased secretion of IL-6, TNF-α and IL-1β in a dose dependent manner [71]; and 3) chronic inflammatory disorders such as inflammatory bowel disease [71] and rheumatoid arthritis [83] are associated with a higher circulating visfatin concentration than normal subjects.

Maternal visfatin in normal gestation and in complications of pregnancy

Adipokines have been implicated in the regulation of metabolic adaptations to gestation, as well as in complications of pregnancy [38, 53-56, 58-64, 67, 75-77, 97]. Normal pregnancy is associated with alterations in maternal circulating visfatin concentrations [24, 31, 50, 65, 70, 99]. In addition, gestational diabetes mellitus [5, 11, 37, 42, 66], preeclampsia [4, 17, 24, 107], large–for-gestational-age neonate [66], fetal growth restriction [16, 47] and preterm labor [53] were linked to changes in circulating maternal visfatin concentrations when compared to normal pregnant women. Consistent with these findings, patients with intra-amniotic infection/inflammation have a higher amniotic fluid concentration of visfatin than those without intra-amniotic infection/inflammation [63].

Umbilical cord visfatin in normal gestation and its association with maternal concentrations of this adipokine

Umbilical cord blood visfatin concentrations have been reported in only a few studies [25, 43, 47, 48]. The results reported herein are in agreement with those of Malamitsi-Puchner et al.[47, 48] who found positive correlation between maternal and fetal visfatin concentrations, as well as those of Ibánez et al.[25] who found no gender disparity in umbilical cord visfatin concentrations. Our findings are also in agreement with López-Bermejo et al.[43] who reported lack of association between umbilical cord blood visfatin concentrations and indices of neonatal size.

The present study indicates that the median maternal visfatin concentration is higher than that determined in the umbilical cord blood regardless of the presence of labor. This finding is in contrast to the reports by Malamitsi-Puchner et al.[47, 48] in which comparable concentrations in the maternal and fetal circulation were detected. Differences in study design can account for the apparent inconsistencies among the studies. Specifically, the ethnic origin, maternal age, and birthweight varied among the studies. We recognize that the cross-sectional nature of our study precludes comment on causality in the association between maternal and fetal circulating visfatin concentration. Nevertheless, several explanations can account for the higher maternal visfatin concentration. As this adipokine is produced by adipose tissue, the mother’s high total fat mass can produce more visfatin. An additional explanation can be differential secretion of placental visfatin between maternal and fetal circulation. Visfatin is expressed in a considerable amount in term human placenta [31, 70]. It is possible that this adipokine is released preferentially into the maternal systemic circulation. Such pattern has been demonstrated for other adipokines produced by the placenta such as leptin [23].

Spontaneous labor at term, in contrast to preterm labor, is not associated with alterations in maternal circulating visfatin

The findings reported herein demonstrate, for the first time, that labor is not associated with significant alterations in maternal visfatin concentrations. Recently, we reported that preterm labor with intra-amniotic infection/inflammation leading to preterm delivery is associated with a higher median maternal plasma concentration of visfatin than normal pregnancy [53]. A possible explanation for this difference is that the metabolic and hormonal changes that characterize spontaneous term labor are different from those of preterm labor. In addition, we have likened increased circulating maternal visfatin concentrations to an inflammatory process in addition to metabolic response. The basis for this hypothesis is that among patients with preterm labor, those with intra-amniotic infection/inflammation had the highest circulating maternal visfatin concentrations [53]. Infection and inflammation are more prevalent as a cause for preterm than term parturition [90, 96]. Thus, the disparity in maternal visfatin concentration between term and preterm labor may reflect etiological differences between these two conditions.

The presence of spontaneous labor at term is associated with high umbilical cord blood visfatin concentrations

The median umbilical cord blood visfatin concentration was higher in neonates born following spontaneous labor than that of those who were delivered by cesarean section in the absence of labor. This is a novel finding and several explanations can be offered: labor imposes metabolic challenge not only on the parturient woman, but also on the fetus. Glucose, the most important fuel for the fetus [10, 93], is subject to dynamic metabolic change during the course of labor. Indeed, parturition is associated with an increased fetal blood glucose [86, 87]. Moreover, umbilical vein concentrations of glucose are lower [36] and those of lactate are higher [93] than in the umbilical artery, suggesting enhanced fetal consumption of glucose during labor. Of note, umbilical cord blood concentrations of glucose, insulin and cortisol are higher in neonates born after spontaneous labor than in neonates born by cesarean delivery in the absence of labor [41], further supporting the notion that labor is an energy consuming state for the fetus.

Visfatin has been implicated in the regulation of glucose homeostasis. Specifically, it has been proposed that visfatin can induce the uptake of glucose into cells [70] and that it can exert other insulinomimetic properties [21, 105]. Furthermore, Haider et al.[21] have demonstrated in a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study, that circulating visfatin concentrations are increased by hyperglycemia in humans. Thus, it is tempting to postulate that the increase in circulating umbilical cord blood visfatin is part of the metabolic adaptations of the fetus during labor aimed to meet the increased demands for glucose.

In conclusion, alterations in circulating maternal visfatin concentrations, previously reported in patients with preterm labor, were not observed in term parturient women thus highlighting the fundamental differences between these two conditions. In contrast, labor is associated with high umbilical cord blood visfatin concentrations suggesting that visfatin may play a role in fetal metabolic adaptations to the increased energy demand associated with labor.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Intramural Research Program of the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, NIH, DHHS.

Reference List

- 1.World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. Vol. 916. backcover; 2003. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases; pp. i–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prevention of diabetes mellitus. Report of a WHO Study Group. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1994;844:1–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acromite M, Ziotopoulou M, Orlova C, Mantzoros C. Increased leptin levels in preeclampsia: associations with BMI, estrogen and SHBG levels. Hormones (Athens) 2004;3:46–52. doi: 10.14310/horm.2002.11111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adali E, Yildizhan R, Kolusari A, Kurdoglu M, Bugdayci G, Sahin HG, et al. Increased visfatin and leptin in pregnancies complicated by pre-eclampsia. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009:1–7. doi: 10.1080/14767050902994622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Akturk M, Altinova AE, Mert I, Buyukkagnici U, Sargin A, Arslan M, et al. Visfatin concentration is decreased in women with gestational diabetes mellitus in the third trimester. J Endocrinol Invest. 2008;31:610–613. doi: 10.1007/BF03345611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Banerjee B, Khew KS, Saha N, Ratnam SS. Energy cost and blood sugar level during different stages of labour and duration of labour in Asiatic women. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1971;78:927–929. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1971.tb00206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briana DD, Boutsikou M, Gourgiotis D, Kontara L, Baka S, Iacovidou N, et al. Role of visfatin, insulin-like growth factor-I and insulin in fetal growth. J Perinat Med. 2007;35:326–329. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2007.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briana DD, Malamitsi-Puchner A. Intrauterine growth restriction and adult disease: the role of adipocytokines. Eur J Endocrinol. 2009;160:337–347. doi: 10.1530/EJE-08-0621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Catalano PM, Hoegh M, Minium J, Huston-Presley L, Bernard S, Kalhan S, et al. Adiponectin in human pregnancy: implications for regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1677–1685. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0264-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cetin I, Alvino G, Radaelli T, Pardi G. Fetal nutrition: a review. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 2005;94:7–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2005.tb02147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chan TF, Chen YL, Lee CH, Chou FH, Wu LC, Jong SB, et al. Decreased plasma visfatin concentrations in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2006;13:364–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2006.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chappell LC, Seed PT, Briley A, Kelly FJ, Hunt BJ, Charnock-Jones DS, et al. A longitudinal study of biochemical variables in women at risk of preeclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:127–136. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cortelazzi D, Corbetta S, Ronzoni S, Pelle F, Marconi A, Cozzi V, et al. Maternal and foetal resistin and adiponectin concentrations in normal and complicated pregnancies. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66:447–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02761.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dahl TB, Yndestad A, Skjelland M, Oie E, Dahl A, Michelsen A, et al. Increased expression of visfatin in macrophages of human unstable carotid and coronary atherosclerosis: possible role in inflammation and plaque destabilization. Circulation. 2007;115:972–980. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.665893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Esplin MS, Fausett MB, Peltier MR, Hamblin S, Silver RM, Branch DW, et al. The use of cDNA microarray to identify differentially expressed labor-associated genes within the human myometrium during labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:404–413. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fasshauer M, Bluher M, Stumvoll M, Tonessen P, Faber R, Stepan H. Differential regulation of visfatin and adiponectin in pregnancies with normal and abnormal placental function. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2007;66:434–439. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.02751.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fasshauer M, Waldeyer T, Seeger J, Schrey S, Ebert T, Kratzsch J, et al. Serum levels of the adipokine visfatin are increased in pre-eclampsia. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;69:69–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03147.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Felig P, Lynch V. Starvation in human pregnancy: hypoglycemia, hypoinsulinemia, and hyperketonemia. Science. 1970;170:990–992. doi: 10.1126/science.170.3961.990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gonzalez RP, Gomez RM, Castro RS, Nien JK, Merino PO, Etchegaray AB, et al. A national birth weight distribution curve according to gestational age in Chile from 1993 to 2000. Rev Med Chil. 2004;132:1155–1165. doi: 10.4067/s0034-98872004001000001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gurson CT, Etili L, Soyak S. Relation between endogenous lipoprotein lipase activity, free fatty acids, and glucose in plasma of women in labour and of their newborns. Arch Dis Child. 1968;43:679–683. doi: 10.1136/adc.43.232.679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haider DG, Schaller G, Kapiotis S, Maier C, Luger A, Wolzt M. The release of the adipocytokine visfatin is regulated by glucose and insulin. Diabetologia. 2006;49:1909–1914. doi: 10.1007/s00125-006-0303-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haugen F, Ranheim T, Harsem NK, Lips E, Staff AC, Drevon CA. Increased plasma levels of adipokines in preeclampsia: relationship to placenta and adipose tissue gene expression. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2006;290:E326–E333. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00020.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hauguel-De MS, Lepercq J, Catalano P. The known and unknown of leptin in pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1537–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.06.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hu W, Wang Z, Wang H, Huang H, Dong M. Serum visfatin levels in late pregnancy and preeclampsia. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2008;87:413–418. doi: 10.1080/00016340801976012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ibanez L, Sebastiani G, Lopez-Bermejo A, Diaz M, Gomez-Roig MD, de ZF. Gender specificity of body adiposity and circulating adiponectin, visfatin, insulin, and insulin growth factor-I at term birth: relation to prenatal growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2008;93:2774–2778. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-0526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jia SH, Li Y, Parodo J, Kapus A, Fan L, Rotstein OD, et al. Pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor inhibits neutrophil apoptosis in experimental inflammation and clinical sepsis. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:1318–1327. doi: 10.1172/JCI19930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kafulafula GE, Moodley J, Ojwang PJ, Kagoro H. Leptin and pre-eclampsia in black African parturients. BJOG. 2002;109:1256–1261. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2002.02043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kahn SE, Hull RL, Utzschneider KM. Mechanisms linking obesity to insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Nature. 2006;444:840–846. doi: 10.1038/nature05482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kajantie E, Kaaja R, Ylikorkala O, Andersson S, Laivuori H. Adiponectin concentrations in maternal serum: elevated in preeclampsia but unrelated to insulin sensitivity. J Soc Gynecol Investig. 2005;12:433–439. doi: 10.1016/j.jsgi.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kashyap ML, Sivasamboo R, Sothy SP, Cheah JS, Gartside PS. Carbohydrate and lipid metabolism during human labor: free fatty acids, glucose, insulin, and lactic acid metabolism during normal and oxytocin-induced labor for postmaturity. Metabolism. 1976;25:865–875. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(76)90119-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Katwa LC, Seidel ER. Visfatin in pregnancy: proposed mechanism of peptide delivery. Amino Acids. 2008;37:555–558. doi: 10.1007/s00726-008-0194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Katz M, Kroll D, Shapiro Y, Cristal N, Meizner I. Energy expenditure in normal labor. Isr J Med Sci. 1990;26:254–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kendal-Wright CE. Stretching, mechanotransduction, and proinflammatory cytokines in the fetal membranes. Reprod Sci. 2007;14:35–41. doi: 10.1177/1933719107310763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kendal-Wright CE, Hubbard D, Bryant-Greenwood GD. Chronic stretching of amniotic epithelial cells increases pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor (PBEF/visfatin) expression and protects them from apoptosis. Placenta. 2008;29:255–265. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2007.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kocyigit Y, Atamer Y, Atamer A, Tuzcu A, Akkus Z. Changes in serum levels of leptin, cytokines and lipoprotein in pre-eclamptic and normotensive pregnant women. Gynecol Endocrinol. 2004;19:267–273. doi: 10.1080/09513590400018108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Konig S, Vest M, Stahl M. Interrelation of maternal and foetal glucose and free fatty acids. The role of insulin and glucagon. Eur J Pediatr. 1978;128:187–195. doi: 10.1007/BF00444304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krzyzanowska K, Krugluger W, Mittermayer F, Rahman R, Haider D, Shnawa N, et al. Increased visfatin concentrations in women with gestational diabetes mellitus. Clin Sci (Lond) 2006;110:605–609. doi: 10.1042/CS20050363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kusanovic JP, Romero R, Mazaki-Tovi S, Chaiworapongsa T, Mittal P, Gotsch F, et al. Resistin in amniotic fluid and its association with intra-amniotic infection and inflammation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:902–916. doi: 10.1080/14767050802320357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kyriakakou M, Malamitsi-Puchner A, Militsi H, Boutsikou T, Margeli A, Hassiakos D, et al. Leptin and adiponectin concentrations in intrauterine growth restricted and appropriate for gestational age fetuses, neonates, and their mothers. Eur J Endocrinol. 2008;158:343–348. doi: 10.1530/EJE-07-0692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Laudanski T. Energy metabolism of the myometrium in pregnancy and labor. Zentralbl Gynakol. 1985;107:568–573. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lauterbach R, Szafran H, Szafran Z. Blood glucose concentration and the levels of cortisol, growth hormone and insulin in women at labour and their healthy neonates born by vaginal delivery and cesarean section. Endokrynol Pol. 1988;39:169–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lewandowski KC, Stojanovic N, Press M, Tuck SM, Szosland K, Bienkiewicz M, et al. Elevated serum levels of visfatin in gestational diabetes: a comparative study across various degrees of glucose tolerance. Diabetologia. 2007;50:1033–1037. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lopez-Bermejo A, de ZF, az-Silva M, Vicente MP, Valls C, Ibanez L. Cord serum visfatin at term birth: maternal smoking unmasks the relation to foetal growth. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008;68:77–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2007.03002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Low JA, Pancham SR, Worthington D, Boston RW. Acid-base, lactate, and pyruvate characteristics of the normal obstetric patient and fetus during the intrapartum period. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1974;120:862–867. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(74)90331-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lyngso D, Simonsen L, Bulow J. Interleukin-6 production in human subcutaneous abdominal adipose tissue: the effect of exercise. J Physiol. 2002;543:373–378. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.019380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Maheux PC, Bonin B, Dizazo A, Guimond P, Monier D, Bourque J, et al. Glucose homeostasis during spontaneous labor in normal human pregnancy. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996;81:209–215. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.1.8550753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Malamitsi-Puchner A, Briana DD, Boutsikou M, Kouskouni E, Hassiakos D, Gourgiotis D. Perinatal circulating visfatin levels in intrauterine growth restriction. Pediatrics. 2007;119:e1314–e1318. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-2589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Malamitsi-Puchner A, Briana DD, Gourgiotis D, Boutsikou M, Baka S, Hassiakos D. Blood visfatin concentrations in normal full-term pregnancies. Acta Paediatr. 2007;96:526–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Marvin KW, Keelan JA, Eykholt RL, Sato TA, Mitchell MD. Use of cDNA arrays to generate differential expression profiles for inflammatory genes in human gestational membranes delivered at term and preterm. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8:399–408. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.4.399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mastorakos G, Valsamakis G, Papatheodorou DC, Barlas I, Margeli A, Boutsiadis A, et al. The role of adipocytokines in insulin resistance in normal pregnancy: visfatin concentrations in early pregnancy predict insulin sensitivity. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1477–1483. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.084731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Kim SK, Vaisbuch E, Kusanovi JP, Erez O, et al. Could alterations in maternal plasma visfatin concentration participate in the phenotype definition of preeclampsia and SGA? The Journal of Maternal-Fetal and Neonatal Medicine. 2009 doi: 10.3109/14767050903301017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Vaisbuch E, Chaiworapongsa T, Erez O, Mittal P, et al. Low circulating maternal adiponectin in patients with pyelonephritis: adiponectin at the crossroads of pregnancy and infection. Journal Of Perinatal Medicine. 2009 doi: 10.1515/JPM.2009.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Vaisbuch E, Erez O, Chaiwaropongsa T, Mittal P, et al. Maternal Plasma Visfatin in Preterm Labor. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:693–704. doi: 10.1080/14767050902994788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Vaisbuch E, Erez O, Mittal P, Chaiwaropongsa T, et al. Dysregulation of maternal serum adiponectin in preterm labor. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009;22:887–904. doi: 10.1080/14767050902994655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Vaisbuch E, Erez O, Mittal P, Chaiwaropongsa T, et al. Maternal Serum Adiponectin Multimers in Gestational Diabetes. Journal Of Perinatal Medicine. 2009 doi: 10.1515/JPM.2009.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Vaisbuch E, Erez O, Mittal P, Chaiwaropongsa T, et al. Maternal Serum Adiponectin Multimers in Patients with a Small-For-Gestational-Age Newborn. Journal Of Perinatal Medicine. 2009 doi: 10.1515/JPM.2009.128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Vaisbuch E, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Mittal P, et al. Adiponectin in amniotic fluid in normal pregnancy, spontaneous labor at term, and preterm labor: A novel association with subclinical intrauterine infection/inflammation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009 doi: 10.1080/14767050903026481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mazaki-Tovi S, Kanety H, Pariente C, Hemi R, Efraty Y, Schiff E, et al. Determining the source of fetal adiponectin. J Reprod Med. 2007;52:774–778. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Mazaki-Tovi S, Kanety H, Pariente C, Hemi R, Schiff E, Sivan E. Cord blood adiponectin in large-for-gestational age newborns. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:1238–1242. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mazaki-Tovi S, Kanety H, Pariente C, Hemi R, Wiser A, Schiff E, et al. Maternal serum adiponectin levels during human pregnancy. J Perinatol. 2007;27:77–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.jp.7211639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mazaki-Tovi S, Kanety H, Pariente C, Hemi R, Yinon Y, Wiser A, et al. Adiponectin and leptin concentrations in dichorionic twins with discordant and concordant growth. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94:892–898. doi: 10.1210/jc.2008-2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mazaki-Tovi S, Kanety H, Sivan E. Adiponectin and human pregnancy. Curr Diab Rep. 2005;5:278–281. doi: 10.1007/s11892-005-0023-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Gotsch F, Mittal P, et al. Visfatin/Pre-B cell colony-enhancing factor in amniotic fluid in normal pregnancy, spontaneous labor at term, preterm labor and prelabor rupture of membranes: an association with subclinical intrauterine infection in preterm parturition. J Perinat Med. 2008;36:485–496. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2008.084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Vaisbuch E, Gotsch F, et al. Adiponectin multimers in maternal plasma. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2008;21:796–815. doi: 10.1080/14767050802266881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Vaisbuch E, Erez O, Than NG, et al. Maternal visfatin concentration in normal pregnancy. J Perinat Med. 2009;37:206–217. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2009.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Vaisbuch E, Erez O, Than NG, et al. Visfatin in human pregnancy: maternal gestational diabetes vis-a-vis neonatal birthweight. J Perinat Med. 2009;37:218–231. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2009.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Vaisbuch E, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Gotsch F, et al. Maternal serum adiponectin multimers in preeclampsia. J Perinat Med. 2009;37:349–363. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2009.085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.McCarthy JF, Misra DN, Roberts JM. Maternal plasma leptin is increased in preeclampsia and positively correlates with fetal cord concentration. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:731–736. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70280-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Milwidsky A, Gutman A. Glycogen metabolism of normal human myometrium and leiomyoma--possible hormonal control. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 1983;15:147–152. doi: 10.1159/000299405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Morgan SA, Bringolf JB, Seidel ER. Visfatin expression is elevated in normal human pregnancy. Peptides. 2008;29:1382–1389. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2008.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Moschen AR, Kaser A, Enrich B, Mosheimer B, Theurl M, Niederegger H, et al. Visfatin, an adipocytokine with proinflammatory and immunomodulating properties. J Immunol. 2007;178:1748–1758. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Naruse K, Yamasaki M, Umekage H, Sado T, Sakamoto Y, Morikawa H. Peripheral blood concentrations of adiponectin, an adipocyte-specific plasma protein, in normal pregnancy and preeclampsia. J Reprod Immunol. 2005;65:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.jri.2004.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Nemeth E, Millar LK, Bryant-Greenwood G. Fetal membrane distention: II. Differentially expressed genes regulated by acute distention in vitro. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:60–67. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70491-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nemeth E, Tashima LS, Yu Z, Bryant-Greenwood GD. Fetal membrane distention: I. Differentially expressed genes regulated by acute distention in amniotic epithelial (WISH) cells. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:50–59. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(00)70490-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Nien JK, Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Erez O, Kusanovic JP, Gotsch F, et al. Plasma adiponectin concentrations in non-pregnant, normal and overweight pregnant women. J Perinat Med. 2007;35:522–531. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2007.123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Nien JK, Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Erez O, Kusanovic JP, Gotsch F, et al. Adiponectin in severe preeclampsia. J Perinat Med. 2007;35:503–512. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2007.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nien JK, Mazaki-Tovi S, Romero R, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Gotsch F, et al. Resistin: a hormone which induces insulin resistance is increased in normal pregnancy. J Perinat Med. 2007;35:513–521. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2007.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.nim-Nyame N, Sooranna SR, Steer PJ, Johnson MR. Longitudinal analysis of maternal plasma leptin concentrations during normal pregnancy and pre-eclampsia. Hum Reprod. 2000;15:2033–2036. doi: 10.1093/humrep/15.9.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ognjanovic S, Bao S, Yamamoto SY, Garibay-Tupas J, Samal B, Bryant-Greenwood GD. Genomic organization of the gene coding for human pre-B-cell colony enhancing factor and expression in human fetal membranes. J Mol Endocrinol. 2001;26:107–117. doi: 10.1677/jme.0.0260107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Ognjanovic S, Bryant-Greenwood GD. Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor, a novel cytokine of human fetal membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;187:1051–1058. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.126295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ognjanovic S, Ku TL, Bryant-Greenwood GD. Pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor is a secreted cytokine-like protein from the human amniotic epithelium. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:273–282. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ognjanovic S, Tashima LS, Bryant-Greenwood GD. The effects of pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor on the human fetal membranes by microarray analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:1187–1195. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00591-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Otero M, Lago R, Gomez R, Lago F, Dieguez C, Gomez-Reino JJ, et al. Changes in plasma levels of fat-derived hormones adiponectin, leptin, resistin and visfatin in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2006;65:1198–1201. doi: 10.1136/ard.2005.046540. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ouyang Y, Chen H, Chen H. Reduced plasma adiponectin and elevated leptin in pre-eclampsia. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2007;98:110–114. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Pasman WJ, Westerterp-Plantenga MS, Saris WH. The effect of exercise training on leptin levels in obese males. Am J Physiol. 1998;274:E280–E286. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1998.274.2.E280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Paterson P, Phillips L, Wood C. Relationship between maternal and fetal blood glucose during labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1967;98:938–945. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(67)90080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Raivio KO, Teramo K. Blood glucose of the human fetus prior to and during labor. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1968;57:512–516. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1968.tb06971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ramsay JE, Jamieson N, Greer IA, Sattar N. Paradoxical elevation in adiponectin concentrations in women with preeclampsia. Hypertension. 2003;42:891–894. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000095981.92542.F6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Revollo JR, Korner A, Mills KF, Satoh A, Wang T, Garten A, et al. Nampt/PBEF/Visfatin regulates insulin secretion in beta cells as a systemic NAD biosynthetic enzyme. Cell Metab. 2007;6:363–375. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Romero R, Espinoza J, Kusanovic JP, Gotsch F, Hassan S, Erez O, et al. The preterm parturition syndrome. BJOG. 2006;113(Suppl 3):17–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Rosen ED, Spiegelman BM. Adipocytes as regulators of energy balance and glucose homeostasis. Nature. 2006;444:847–853. doi: 10.1038/nature05483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Samal B, Sun Y, Stearns G, Xie C, Suggs S, McNiece I. Cloning and characterization of the cDNA encoding a novel human pre-B-cell colony-enhancing factor. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:1431–1437. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.2.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Scheepers HC, de Jong PA, Essed GG, Kanhai HH. Fetal and maternal energy metabolism during labor in relation to the available caloric substrate. J Perinat Med. 2001;29:457–464. doi: 10.1515/JPM.2001.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sethi JK, Vidal-Puig A. Visfatin: the missing link between intra-abdominal obesity and diabetes? Trends Mol Med. 2005;11:344–347. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sharma A, Satyam A, Sharma JB. Leptin, IL-10 and inflammatory markers (TNF-alpha, IL-6 and IL-8) in pre-eclamptic, normotensive pregnant and healthy non-pregnant women. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2007;58:21–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00486.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Shim SS, Romero R, Hong JS, Park CW, Jun JK, Kim BI, et al. Clinical significance of intra-amniotic inflammation in patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:1339–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sivan E, Mazaki-Tovi S, Pariente C, Efraty Y, Schiff E, Hemi R, et al. Adiponectin in human cord blood: relation to fetal birth weight and gender. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:5656–5660. doi: 10.1210/jc.2003-031174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Suwaki N, Masuyama H, Nakatsukasa H, Masumoto A, Sumida Y, Takamoto N, et al. Hypoadiponectinemia and circulating angiogenic factors in overweight patients complicated with pre-eclampsia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1687–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Szamatowicz J, Kuzmicki M, Telejko B, Zonenberg A, Nikolajuk A, Kretowski A, et al. Serum visfatin concentration is elevated in pregnant women irrespectively of the presence of gestational diabetes. Ginekol Pol. 2009;80:14–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Tilg H, Moschen AR. Adipocytokines: mediators linking adipose tissue, inflammation and immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2006;6:772–783. doi: 10.1038/nri1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Vaisbuch E, Mazaki-Tovi S, Kusanovic JP, Erez O, Than GN, Kim SK, et al. Retinol Binding Protein 4: An Adipokine Associated with Intra-amniotic Infection / Inflammation. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2009 doi: 10.3109/14767050902994739. 19900011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Vaisbuch E, Romero R, Mazaki-Tovi S, Erez O, Kim SK, Chaiworapongsa T, et al. Retinol binding protein 4 - a novel association with early-onset preeclampsia. J Perinat Med. 2009 doi: 10.1515/JPM.2009.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Verhaeghe J, van Bree R, van Herch E. Maternal body size and birth weight: can insulin or adipokines do better? Metabolism. 2006;55:339–344. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2005.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Whaley WH, Zuspan FP, Nelson GH, Ahlquist RP. Alterations of plasma free fatty acids and glucose during labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1967;97:875–880. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(67)90510-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Xie H, Tang SY, Luo XH, Huang J, Cui RR, Yuan LQ, et al. Insulin-like effects of visfatin on human osteoblasts. Calcif Tissue Int. 2007;80:201–210. doi: 10.1007/s00223-006-0155-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Zhang YY, Gottardo L, Thompson R, Powers C, Nolan D, Duffy J, et al. A visfatin promoter polymorphism is associated with low-grade inflammation and type 2 diabetes. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14:2119–2126. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Zulfikaroglu E, Isman F, Payasli A, Kilic S, Kucur M, Danisman N. Plasma visfatin levels in preeclamptic and normal pregnancies. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s00404-009-1192-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]