Abstract

Hereditary myelopathies are a diverse group of disorders in which major aspects of the clinical syndrome involve spinal cord structures. Hereditary myelopathic syndromes can be recognized as four clinical paradigms: (1) spinocerebellar ataxia, (2) motor neuron disorder, (3) leukodystrophy, and (4) distal motor-sensory axonopathy. This review illustrates these hereditary myelopathy paradigms with clinical examples with an emphasis on clinical recognition and differential diagnosis.

INTRODUCTION AND SYNDROMIC CLASSIFICATION

Hereditary myelopathies are diverse inherited disorders in which major clinical and pathologic features involve spinal cord structures. In contrast to disorders such as inherited neuropathies, in which clinical and pathologic abnormalities are often limited to one region of the nervous system, neurologic involvement in nearly all hereditary myelopathies includes structures outside of the spinal cord. Most hereditary myelopathies conform to the following syndromes: spinocerebellar degeneration, motor neuron disorder, leukodystrophy, and distal axonopathy (Table 3-1).

TABLE 3-1.

Syndromic Classification of Hereditary Myelopathies

| Major Syndrome | Representative Examples | Diagnostic Testing |

|---|---|---|

| Spinocerebellar ataxias (SCA) (Paulson, 2007) | SCA 1 through 28 | Genetic testing for specific SCA gene mutation; neuroimaging to demonstrate cerebellar atrophy |

| Machado-Joseph disease (SCA3) | Genetic testing for specific SCA gene mutation; neuroimaging to demonstrate cerebellar atrophy | |

| Friedreich ataxia | FRDA gene analysis | |

| Familial vitamin E deficiency | Serum vitamin E | |

| Abetalipoproteinemia (Bassen-Kornzweig) | Lipoprotein electrophoresis | |

| Charlevoix-Saguenay (ARSACS) | ||

| Motor neuron disorders (Pasinelli and Brown, 2006) | Spinal muscular atrophy | Survival motor neuron gene analysis |

| Familial ALS | SOD1 gene analysis | |

| Primary lateral sclerosis (rarely familial) | ALSin gene analysis (for juvenile familial primary lateral sclerosis) | |

| Hereditary spastic paraplegia (HSP) | HSP gene analysis | |

| Spinobulbar muscular atrophy (Kennedy syndrome) | Androgen-receptor gene mutation (CAG repeats) | |

| Partial hexosaminidase deficiency | Leukocyte hexosaminidase assay | |

| Leukodystrophies (Lyon et al, 2006) | Subacute combined degeneration (rarely familial) | Serum B12 |

| Multiple sclerosis (occasionally familial) | MRI of brain and spinal cord; CSF analysis; clinical course | |

| Adrenoleukodystrophy, Adrenomyeloneuropathy (Moser et al, 2007) | Serum very long chain fatty acid analysis | |

| Krabbe disease | Leukocyte β-galactosidase assay | |

| Metachromatic leukodystrophy | Leukocyte arylsulfatase assay | |

| Pelizeaus-Merzbacher (Garbern et al, 2002) | Proteolipid protein gene analysis | |

| Cerebrotendinous xanthomatosis | Serum cholestanol | |

| CNS predominant, distal motor-sensory axonopathies (Fink, 2007a; Fink, 2007b) | Hereditary spastic paraplegia | HSP gene analysis |

| Other | Mitochondrial myelopathy (Scheper et al, 2007) | MRI spectroscopy (brain), muscle biopsy for ragged red fibers and histochemical evidence of oxidative phosphorylation deficit; mitochondrial gene analysis |

| Myelopathy related to Leber optic atrophy (Bruyn and Went, 1964) | ||

| Variant Alzheimer disease with spastic paraplegia due to presenilin 1 mutation | Presenilin 1 gene analysis | |

| Hyperzincemia | Serum zinc | |

| Neurofibromatosis type 2 | MRI scan | |

| Hereditary exostosis with spinal cord compression | CT and MRI scans | |

| Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia | MRI scan | |

| Von Hippel Lindau (vHL) (hereditary hemangiomata) | MRI scan and VHL gene analysis | |

| Tropical spastic paraplegia (due to human T-lymphotropic virus type 1 [HTLV-1] infection; may occur in familial clusters) | HTLV-1 antibody testing | |

| Arginase deficiency | Increased plasma arginine, reduced red blood cell arginase | |

| Biotinidase deficiency | Reduced serum biotinidase | |

| Syringomyelia (rarely familial) | MRI scan | |

| Sjögren-Larsson syndrome | Clinical features of congenital ichthyosis, mental deficiency, and spastic diplegia or tetraplegia (typically accompanied by additional features), and demonstrating enzyme (fatty aldehyde dehydrogenase) defect in cultured fibroblasts. |

Bruyn GW, Went LN. A sex-linked heredo-degenerative neurological disorder, associated with Leber′s optic atrophy. I. Clinical studies. J Neurol Sci 1964;54:59–80.

Fink JK. Hereditary spastic paraplegia. In: Rimoin D, Connor JM, Pyeritz RE, Korf BR, editors. Emery and Rimoin’s principles and practice of medical genetics. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone, 2007a:2771–2801.

Fink JK. The hereditary spastic paraplegias. In: Rosenberg RN, DiMauro S, Paulson HL, et al, editors. The molecular and genetic basis of neurologic and psychiatric disease. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2007b.

Garbern JY, Yool DA, Moore GJ, et al. Patients lacking the major CNS myelin protein, proteolipid protein 1, develop length-dependent axonal degeneration in the absence of demyelination and inflammation. Brain 2002;125(pt 3):551–561.

Lyon G, Fattal-Valevski A, Kolodny EH. Leukodystrophies: clinical and genetic aspects. Top Magn Reson Imaging 2006;17(4):219–242.

Moser HW, Mahmood A, Raymond GV. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Nat Clin Pract Neurol 2007;3(3):140–151. Pasinelli P, Brown RH. Molecular biology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: insights from genetics. Nat Rev Neurosci 2006;7(9):710–723.

Paulson HL. Dominantly inherited ataxias: lessons learned from Machado-Joseph disease/spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Semin Neurol 2007;27(2):133–142.

Scheper GC, van der Klok T, van Andel RJ, et al. Mitochondrial aspartyl-tRNA synthetase deficiency causes leu-koencephalopathy with brain stem and spinal cord involvement and lactate elevation. Nat Genet 2007;39(4):534–539.

FOUR INHERITED MYELOPATHY SYNDROMES

Spinocerebellar Degeneration

Spinocerebellar degeneration (eg, Friedreich ataxia, Machado-Joseph disease [MJD] [spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 (SCA3)], Bassen-Kornzweig syndrome, and vitamin E deficiency [occasionally familial]) are recognized by a combination of progressive cerebellar ataxia, peripheral neuropathy and dorsal column impairment, and variable corticospinal tract involvement. Diagnostic recognition of these disorders is increased if one bears in mind that these elements may exist in variable proportions, that diagnostic elements may appear asynchronously as the disorder evolves, and that some of the diagnostic elements may be absent entirely (Case 3-1 and Case 3-2).

Case 3-1

A 24-year-old woman began to notice insidiously progressive difficulty with walking and balance beginning at approximately age 12. There was no previous illness and no family history of similar symptoms. Although able to walk and run, she noted that she had to concentrate on keeping her balance. Within the next 2 years she began noticing tingling sensation in both legs. Classmates began commenting that she walked as if she were drunk. Gait disturbance continued to worsen slowly. Her neurologic examination at age 24 revealed normal speech and normal cranial nerves with the exception of saccadic intrusions into smooth pursuit. Muscle bulk, tone, and strength were normal in the upper extremities. In the lower extremities, however, muscle tone was increased (particularly at the hamstrings and ankles and to a lesser extent at the quadriceps), and she had marked weakness of tibialis anterior, moderate weakness of iliopsoas, and mild weakness of hamstring muscles. There was profound impairment of distal vibratory sensation (she was able to perceive vibratory sensation applied to her shins but not to her toes) as well as moderately impaired distal proprioception. There was subjectively decreased pinprick sensation in the distal aspects of lower extremities. Deep tendon reflexes were 1 to 2+ at the biceps, triceps, and brachioradialis; 3+ at the knees; and absent at the ankles. Finger-nose testing was normal. Heel-to-shin testing was minimally abnormal. Plantar responses were extensor bilaterally. Nerve conduction studies and EMG were consistent with sensory-motor polyneuropathy. MRI scan of the brain was normal.

Neuro-localization

Neuro-localization indicated deficits referable to corticospinal tracts serving bilateral lower extremities (weakness, increased tone, extensor plantar responses); subtle midline cerebellar disturbance (saccadic intrusions into smooth pursuit and mild heel-to-shin abnormality); dorsal columns and/or dorsal roots (marked vibration and proprioception impairment, which were out of proportion to subtle diminution in pinprick perception); and peripheral nerve (absent ankle deep tendon reflexes and stocking distribution of subjectively decreased pinprick sensation).

Diagnosis

Friedreich ataxia. Friedreich ataxia (“frataxin,” FRDA) gene analysis indicated that the patient was a compound heterozygote, having one FRDA allele with an expanded repeat ([GAA]962) and the other FRDA allele with a missense mutation resulting in amino acid substitution (G130V).

Comment

Friedreich ataxia is the most common form of autosomal recessive SCA. Friedreich ataxia is often associated with hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (absent in the patient described above). The vast majority of patients with Friedreich ataxia are homozygous for expanded trinucleotide repeat in the frataxin gene, which encodes a mitochondrial protein. The patient described is not homozygous for this trinucleotide repeat. Rather she is a compound heterozygote, having an expanded GAA repeat on one frataxin allele and a point mutation on the other. Point mutations (instead of GAA expansion) are responsible for only 2% of patients with Friedreich ataxia.

Case 3-2

A 52-year-old man began having insidiously progressive gait disturbance at age 38. Over the next decade he developed progressive lower extremity weakness, spasticity, fasciculations, and increasing inversion of his feet. By age 50 his symptoms had extended to include hypophonia, dysarthria, and generalized bradykinesia. Neurologic examination at age 52 demonstrated masked facies, saccadic intrusions into smooth pursuit eye movements, and both generalized spasticity and diffuse fasciculations involving all extremities and the tongue, distal extremity atrophy, and lower extremity hyporeflexia. After age 55, the patient was unable to ambulate. Neurologic examination at age 57 showed hypophonia, spastic and hypokinetic dysarthria, lid retraction, saccadic intrusions into smooth pursuit eye movements, sustained end-gaze nystagmus, facial myokymia, and masked facies. There was moderate atrophy of distal upper and lower extremity muscles and diffuse fasciculations, moderate to marked weakness of intrinsic hand and proximal lower extremity muscles, and severe weakness of distal lower extremity muscles. Spasticity, which had been a prominent feature previously, was no longer present. There was a glove-and-stocking distribution of sensory loss to all modalities. Deep tendon reflexes were hypoactive in the upper extremities and absent in the lower extremities. Plantar responses were flexor on the right and extensor on the left. Finger-to-nose testing revealed marked bradykinesia but no dysmetria.

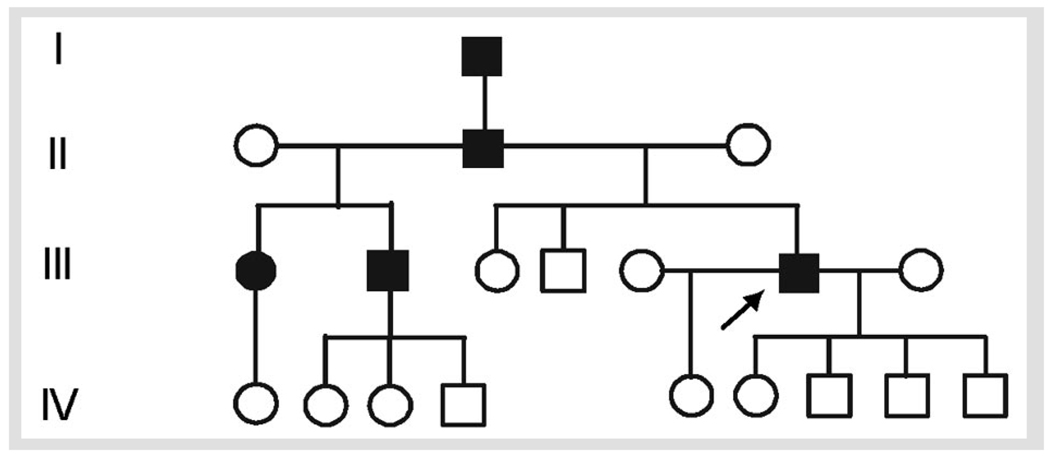

Family history (Figure 3-1) was significant for a similarly affected father, paternal half-brother, and paternal half-sister. EMG obtained at age 52 and repeated at age 53 revealed severe, progressive chronic sensorimotor neuropathy primarily of the axonal type. Fasciculations were diffuse in all regions (including paraspinal muscles). Sural nerve biopsy obtained at age 55 showed a moderate to severe axonal neuropathy.

Neuro-localization

At the onset of disease, deficits were localized primarily to corticospinal tracts serving bilateral lower extremities (causing spastic gait). As the disorder progressed, these deficits became associated with signs of extrapyramidal disturbance (generalized bradykinesia) and subsequently lower motor neuron abnormalities (generalized fasciculations and atrophy) and motor-sensory neuropathy. As peripheral neuropathy advanced, initially prominent spasticity resolved and hyperreflexia gave way to areflexia. Midline cerebellar abnormalities were limited to saccadic intrusions into smooth pursuit eye movements.

Diagnosis

MJD (SCA3). Genetic testing for MJD/SCA3 revealed one expanded allele (69 CAG repeats) and one normal allele (30 CAG repeats). CSF revealed increased protein (74 mg/dL) but was otherwise normal.

Comment

MJD/SCA3 is due to trinucleotide repeat (CAG) expansion that, like other polyglutamine expansions, is thought to be pathogenic through protein misfolding (Paulson, 2007). MJD/SCA3 phenotypes vary from spastic paraparesis (which dominated the first decade of this patient’s symptoms) to complex syndromes involving elements of cerebellar ataxia, extrapyramidal disturbance (eg, nigrostriatal pathway disturbance), and peripheral neuropathy. Symptoms often evolve as the disorder progresses and other neurologic regions become involved.

The frataxin trinucleotide repeat is GAA instead of the more common polyglutamine expansion (CAG) repeat responsible for Huntington chorea, MJD, and many other spinocerebellar degenerations. Furthermore, the frataxin GAA trinucleotide repeat occurs in an intron (frataxin intron 1) and does not alter the frataxin coding sequence. Nonetheless, this intronic mutation leads to reduced frataxin messenger RNA (possibly through locally increased DNA methylation leading to reduced transcription) (Greene et al, 2007), iron accumulation in mitochondria, and an apparent increased vulnerability to oxidative stress.

Motor Neuron Disorder

Motor neuron disorders involve degeneration of corticospinal tracts, anterior horn cells, or both. Cortical motor neurons may also be involved, although generally to a lesser extent. Syndrome diversity depends on the relative combination of upper and lower motor neuron involvement. In primary lateral sclerosis (PLS) for example, progressive spastic weakness, initially affecting the legs and later involving the arms, speech, and swallowing, reflects corticospinal and corticobulbar tract involvement, and to a lesser extent, loss of cortical motor neurons (Case 3-3). In PLS, there is either no evidence of lower motor neuron involvement or, at most, minimal evidence on EMG of chronic denervation late in the disease. At the other extreme, spinal muscular atrophy is characterized by muscular weakness and atrophy due to anterior horn cell degeneration with preservation of corticospinal tracts. Disorders collectively known as the amyotrophic lateral scleroses typically involve degeneration of both anterior horn cells and corticospinal tracts, and to a lesser degree, loss of cortical motor neurons.

Case 3-3

Two sisters were each products of uncomplicated full-term gestations, labors, and deliveries. Each attained early developmental milestones normally. Beginning in the second year of life, each child’s gait became progressively abnormal with scissoring and a tendency to drag her toes. Wheelchairs became necessary at ages 10 and 7, respectively. At approximately these ages, each patient began to experience insidiously progressive, upper extremity spasticity, weakness, and decreased dexterity along with dysarthria and dysphagia (which later required supplemental feedings via gastrostomy tubes). Intelligence was preserved, and they were able to attend school, manipulate controls on motorized wheelchairs, and type on communicative keyboards. Ultimately, however, upper extremity involvement prevented any functional use of the hands and arms.

Both sisters were examined annually for more than 10 years. Recent examination of the younger (age 20) and older (age 22) sister showed that they were alert, attentive, able to follow simple commands, but unable to speak. Each patient had weakness of facial muscles, limited tongue movements, brisk jaw jerk, and drooling. Slowing of downward saccadic eye movements was noted. They had marked spasticity of upper and lower extremities, generalized hyperreflexia, and extensor plantar responses. There was no muscle atrophy or fasciculation. Light touch, pinprick, and vibratory sensations were normal. MRI scans of the brain and spinal cord, EMG, and nerve conduction studies were normal.

Neuro-localization

Deficits on examination were referable to corticospinal tracts serving all extremities; corticobulbar tracts serving the face, speech, and swallowing; and to a limited extent, supranuclear control of downward eye movements.

Diagnosis

Juvenile, familial PLS (also referred to as “infantile ascending spastic paraplegia”).

Comment

For most individuals, PLS occurs as an apparently sporadic, adult-onset disorder (Yang et al, 2001). Rarely, PLS begins in early childhood and occurs in families, where it appears to be an autosomal recessive disorder. Yang and colleagues (2001) identified mutations in the ALSin gene in subjects with autosomal recessive, juvenile PLS. Depending on the precise location of the ALSin gene mutation, subjects exhibit either a phenotype of pure upper motor neuron impairment (PLS phenotype) or also manifest lower motor neuron disturbance (consistent with juvenileonset, autosomal recessive ALS phenotype). Like the patients described above, the family described by Yang and colleagues (2001) also had supranuclear gaze disturbance.

The syndromic classification “motor neuron disorder” and the pathologic classification “distal axonopathy” overlap. The primary differences are the degree to which anterior horn cells are lost (eg, a major aspect of spinal muscular atrophy) and the degree of sensory (eg, dorsal column) involvement (a finding common in hereditary spastic paraplegia but absent in PLS and ALS).

Leukodystrophy

Leukodystrophies have variable presentations, including cognitive disturbance, signs of progressive corticospinal tract deficits (spasticity, slowness of movements, loss of dexterity, hyperreflexia, extensor plantar responses, Hoffman and Tromner signs). The complete constellation of insidiously progressive cognitive impairment, spasticity, optic neuropathy, and demyelinating peripheral neuropathy is very suggestive of leukodystrophy (Case 3-4). Often, however, all elements of this constellation may not be present. In particular, demyelinating peripheral neuropathy, which typically accompanies childhood-onset leukodystrophies (eg, Krabbe disease and metachromatic leukodystrophy) may be absent in the rare adolescent- and adult-onset forms of these disorders.

Case 3-4

A 35-year-old man, now severely disabled by progressive neurologic disease, was the product of full-term, uncomplicated labor, gestation, and delivery. Developmental milestones were normal, although he did not walk independently until 16 months of age. He excelled in academic and athletic activities throughout high school and college. A testicular mass noted at age 23 was diagnosed as malignant with spread to local lymph node and required orchiectomy and chemotherapy. He became seriously ill following chemotherapy and was discovered to have adrenal insufficiency (age 23), which required replacement therapy. At approximately this time he began noting numbness in his feet and ankles while playing tennis. These symptoms increased and within a year became associated with stumbling and tripping. At approximately age 24 he began to experience slowly progressive memory disturbance as well as behavioral symptoms that became increasingly severe, including extreme anxiety, depression, self-injurious behavior, and drug use. He also began experiencing both progressive hearing impairment (beginning at approximately age 29) and progressive visual impairment (progressive optic atrophy, first noted at age 30). Gait disturbance increased slowly, and he required a wheelchair by age 30. Intermittent generalized tonicclonic seizures began at age 33 and included an episode of status epilepticus. Neurologic examination at age 32 showed him to be alert, slightly disoriented, with normal speech, and able to follow two-step commands. He had short-term memory impairment, slightly decreased visual acuity, significantly impaired hearing, markedly increased muscle tone, and moderate to marked weakness in the lower extremities. Symmetric, generalized hyperreflexia was present. Sensation was impaired in the lower extremities, with decreased vibration perception below the knees. He was able to stand briefly. By age 35 he was aphonic and required jejunostomy feeding. Although awake, he was only minimally responsive to social interaction. He had generalized severe spasticity and very few and very slow spontaneous movements. There was no family history of similar disorder.

Neuro-localization

Neurologic deficits involved corticospinal tracts (symmetric, four-limb spastic weakness with hyperreflexia); peripheral nerve (reduced pinprick and vibratory sensation in the lower extremities); optic and acoustic nerves (optic neuropathy and deafness); and frontal lobes (dementia and behavioral disturbance).

Diagnosis

Adrenomyeloneuropathy (AMN) was diagnosed by elevated serum very long chain fatty acids.

Comment

This patient’s clinical course illustrates aspects common to many leukodystrophies: spasticity, peripheral neuropathy, optic atrophy, behavioral and cognitive disturbance, and late-onset seizures.

Childhood-onset adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) and adolescent- and adult-onset AMN are X-linked disorders in which ABCD1 gene mutation leads to impaired peroxisomal β-oxidation and accumulation of very long chain fatty acids systemically (Moser et al, 2007). ALD/AMN phenotypes include rapidly progressive childhood, adolescent, and adult cerebral forms; slowly progressive myelopathic forms (characterized by slowly progressive spastic paraparesis and peripheral neuropathy, often with complete sparing of the brain); and isolated adrenal insufficiency. The patient described above has confluent leukodystrophy in brain MRI and conforms to the adult-onset cerebral form of ALD/AMN.

Distal Axonopathy

Distal axonopathies involving the spinal cord may be entirely motor (eg, PLS) or involve both long motor (corticospinal) and sensory (dorsal column) fibers (eg, uncomplicated hereditary spastic paraplegia) (Case 3-5).

Case 3-5

A 34-year-old woman had infantile-onset, nonprogressive spastic gait, the appearance of which was consistent with spastic diplegic cerebral palsy. At age 26 she had a son who also had infantile-onset, nonprogressive spastic gait. They were diagnosed as having “familial cerebral palsy.” Each subject was the product of full-term, uncomplicated gestation, labor, and delivery. Examination revealed brisk lower limb tendon reflexes, clonus, waddling gait, normal bulbar and upper limb function, bowel and urinary control, and normal intelligence. Diagnostic evaluations, including CT scan of the brain and routine laboratory studies, were normal for both the mother and child.

Localization

Neurologic deficits were referable to corticospinal tracts serving bilateral lower extremities.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of autosomal dominant, uncomplicated, earlyonset HSP was made on the basis of neurologic findings and family history, and confirmed by identification of SPG3A/atlastin gene mutation in both affected subjects (Rainier et al, 2006).

Comment

SPG3A/atlastin gene mutation is the most common cause of childhood-onset, autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia. As in this example, when HSP symptoms begin in infancy, they may not worsen significantly even over the course of several decades. With the exclusion of mistaken paternity (data not shown) (Rainier et al, 2006), the absence of this mutation in the proband′s parents indicates that the mutation arose de novo in the proband. This is an example of a subject with the syndrome of spastic diplegic cerebral palsy actually representing de novo mutation in a gene for autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia.

Distinguishing between leukodystrophies and axonopathies at the bedside is important to arrive at a differential diagnosis. Signs of corticospinal tract impairment (spastic weakness, hyperreflexia, extensor plantar responses, Hoffman and Tromner signs) are typical of both leukodystrophies and axonopathies. Clinical distinction of leukodystrophies from axonopathies is based on the presence of additional neurologic findings, particularly sensory disturbance. For example, patients with generalized leukodystrophies (those affecting myelin of both the central and peripheral nervous systems) classically (although not always) also have peripheral neuropathy, which may manifest as stocking distribution of hypesthesia, and, in the context of corticospinal tract deficits, a gradient of deep tendon reflexes, with grade 3+ patellar and 1+ ankle reflexes. On the other hand, sensory impairment in motor-sensory axonopathies (eg, hereditary spastic paraplegia) is limited typically to mild dorsal column impairment affecting longer fibers (fasciculus gracilis) predominantly and manifests as impaired vibration perception in the toes with preservation of other sensory modalities.

The hereditary spastic paraplegias (HSPs) are a group of more than 35 disorders in which the primary clinical feature is progressive lower extremity spastic weakness (Table 3-2) (Fink, 2007a; Fink, 2007b). This is often accompanied by subtle decrease in vibration perception in the toes. Generalizing from the limited postmortem material available, at least several genetic forms of HSP involve axon degeneration that is maximal in the distal aspects of the longest motor (corticospinal tracts) and sensory (fasciculus gracilis) fibers in the CNS. Degeneration is maximal at the ends of these fibers: corticospinal tract degeneration is maximal in the thoracic region, and fasciculus gracilis fiber degeneration is maximal in the cervicalmedullary region. In addition to degeneration of long axons in the CNS, axonal degeneration in peripheral motor and sensory fibers is recognized in an increasing number of types of HSP. Such “complicated” HSP syndromes include distal wasting in addition to spasticity, hyperreflexia, and upper motor neuron pattern of weakness. Distal motor-sensory axonopathy of the CNS (eg, uncomplicated HSP) can be considered analogous to Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2 disease, in which distal motor-sensory axonopathy is limited to the peripheral nervous system.

TABLE 3-2.

Summary of Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia

| ▶ | Genetics |

| More than 35 different genetic types: dominant, recessive, and X-linked forms. SPG4 HSP (due to spastin gene mutation) is the most common type of autosomal dominant HSP. SPG3A HSP (due to atlastin gene mutation) is the most common type of childhood-onset, autosomal dominant HSP. Genetic penetrance for autosomal dominant HSP is age-dependent and high (~85% for SPG4) but often incomplete. | |

| ▶ | Clinical Variability |

| Variability between and within different genetic types. Individuals with severe and mild forms may coexist in the same family. | |

| ▶ | “Uncomplicated” and “Complicated Hereditary Spastic Paraplegia” |

| “Uncomplicated HSP”: gait disturbance due to lower extremity spastic weakness; subtle vibration impairment in the toes; urinary urgency. “Complicated HSP”: symptoms and signs of uncomplicated HSP plus additional systemic or neurologic involvement (such as muscle wasting, peripheral neuropathy, cataracts, ataxia, mental retardation). | |

| Increasingly, additional neurologic involvement is shown for types of HSP long considered to be uncomplicated (eg, SPG3A and SPG4 due to atlastin and spastin gene mutation, respectively). These include lower motor neuron involvement in SPG3A (atlastin mutation) subjects, and cognitive disturbance and dementia in SPG4 (spastin mutation subjects). | |

| ▶ | Neuropathology |

| Axon degeneration maximally affecting the distal ends of the longest CNS motor (corticospinal tracts) and sensory (fasciculus gracilis) fibers. Complicated HSP types have additional, syndrome-specific neuropathology. | |

| ▶ | Molecular Basis |

| Several different molecular processes underlie various forms of HSP. These include disturbance in microtubule dynamics (eg, SPG4/spastin), axonal transport (eg, SPG10/KIF5A), mitochondria (eg, SPG7/paraplegin, SPG13/chaperonin 60, and SPG31/REEP1, which are mitochondrial proteins), corticospinal tract development (SPG1/L1CAM), and myelination (SPG2/proteolipid protein). | |

| ▶ | Treatment |

| Exercise, gait and balance training, spasticity-reducing medications (eg, oral or intrathecal baclofen), ankle-foot orthotic devices, medication to reduce urinary urgency (eg, oxybutynin). | |

| Exercise recommendations (to improve balance, strength, aerobic capacity, and endurance, and reduce spasticity) are based largely on anecdotal reports by subjects with HSP who have reported benefit. | |

| ▶ | Prognosis |

| Infantile-onset HSP often shows little worsening for the first 2 decades. Childhood- and later-onset HSP typically worsen insidiously over years and decades. Assistive devices (including wheelchairs) may be needed. Uncomplicated HSP does not involve upper extremity, speech, bulbar, or respiratory muscles or shorten life expectancy. In view of the clinical variability noted above, a cautious “wait-and-see” prognosis is advised, rather than assuming that the disorder will be uniformly severe within a given family. | |

| ▶ | Diagnosis and Genetic Testing |

| Diagnostic criteria include signs and symptoms of HSP; exclusion of other disorders; family history is important but may be absent (eg, recessive HSP, new mutation, nonpaternity). Genetic testing of four genes for dominantly inherited HSP is available (through Athena Diagnostics Laboratory, Boston) that together can diagnose ~65% of dominantly inherited HSP. | |

| ▶ | Differential Diagnosis |

| Structural disorders affecting brain or spinal cord; spinal cord arteriovenous malformation; leukodystrophies (including vitamin B12, adrenomyeloneuropathy, Krabbe disease, metachromatic leukodystrophy, multiple sclerosis), dopa-responsive dystonia, ALS, primary lateral sclerosis, and human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1. |

HSP = hereditary spastic paraplegia

Modified with permission from Fink JK. The hereditary spastic paraplegias. In: Rosenberg, DiMauro S, Paulson HL, et al, editors. Molecular and genetic basis of neurologic and psychiatric disease. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott William & Wilkins, 2007. Copyright © 2007, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

It is not uncommon for HSP gene testing to reveal a mutation of unknown significance (Cases 3-6 and 3-7). This happens frequently because many HSP gene mutations are “private,” being uniquely present in the family in which they are discovered. This is particularly common for SPG4/ spastin mutations, which are the most common cause of dominantly inherited HSP.

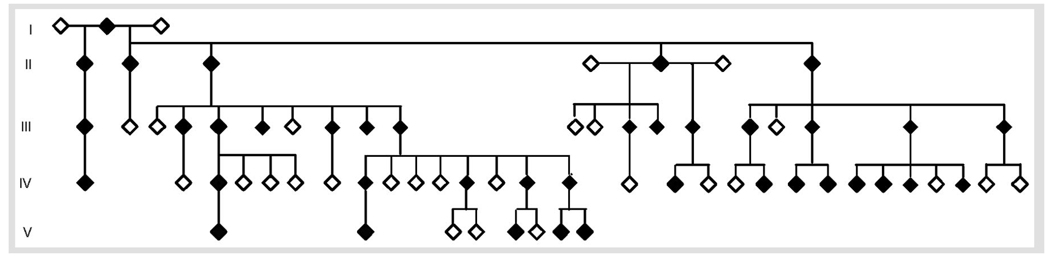

Case 3-6

A 25-year-old man has been followed because of a family history of gait disturbance. He was the product of uncomplicated gestation, labor, and delivery to nonconsanguineous parents. Family history (Figure 3-2) was consistent with transmission of a highly penetrant, autosomal dominant disorder characterized by insidiously progressive gait disturbance. When first examined at age 17, he was asymptomatic, and even though his gait was normal, he had mildly hyperactive lower extremity deep tendon reflexes. Beginning at age 20, he began to experience insidiously progressive gait disturbance. Reexamination at age 25 revealed marked gait abnormality with anteriorly shifted heel strike, difficulty lifting the legs, and circumduction; lower extremity spasticity, weakness, hyperreflexia, extensor plantar responses, and mild decrease in vibration perception in the toes.

Deficits on examination were referable to corticospinal tracts serving bilateral lower extremities and, to a lesser extent, dorsal column (fasciculus gracilis) fibers.

Diagnosis

Autosomal dominant HSP. Genetic analysis revealed mutation in the SPG6/NIPA1 gene (Rainier et al, 2003).

Comment

HSP gene testing is most useful to confirm a clinical diagnosis of HSP and should be interpreted in the context of clinical findings. When an HSP gene mutation is identified in a subject with typical features of HSP, this information can be used for predictive genetic counseling. Genetic testing is available clinically that can diagnose approximately 65% of dominantly inherited HSP and two forms of X-linked HSP (due to mutations in proteolipid protein and L1 cell adhesion molecule genes).

Case 3-7

A 35-year-old man was evaluated because of difficulty walking. He was the product of full-term uncomplicated gestation, labor, and delivery. Walking was slightly delayed (15 months) and associated with mild turning in of the right foot, for which he wore corrective leg braces at night. Despite a slightly awkward gait during childhood, he was active and played sports until age 14. At approximately that time he began to notice very slowly progressive gait disturbance. Examination at age 14 showed pes cavus with hammer toe deformity, lower extremity spastic weakness, lower extremity hyperreflexia, extensor plantar responses, and spastic gait. Nerve conduction testing and EMG were normal. Gait disturbance worsened slowly, necessitating a cane by age 34. His symptoms were confined to lower extremity spastic weakness and gait disturbance and occasional difficulty initiating urination. There was no involvement in the upper extremities and no reported sensory disturbance.

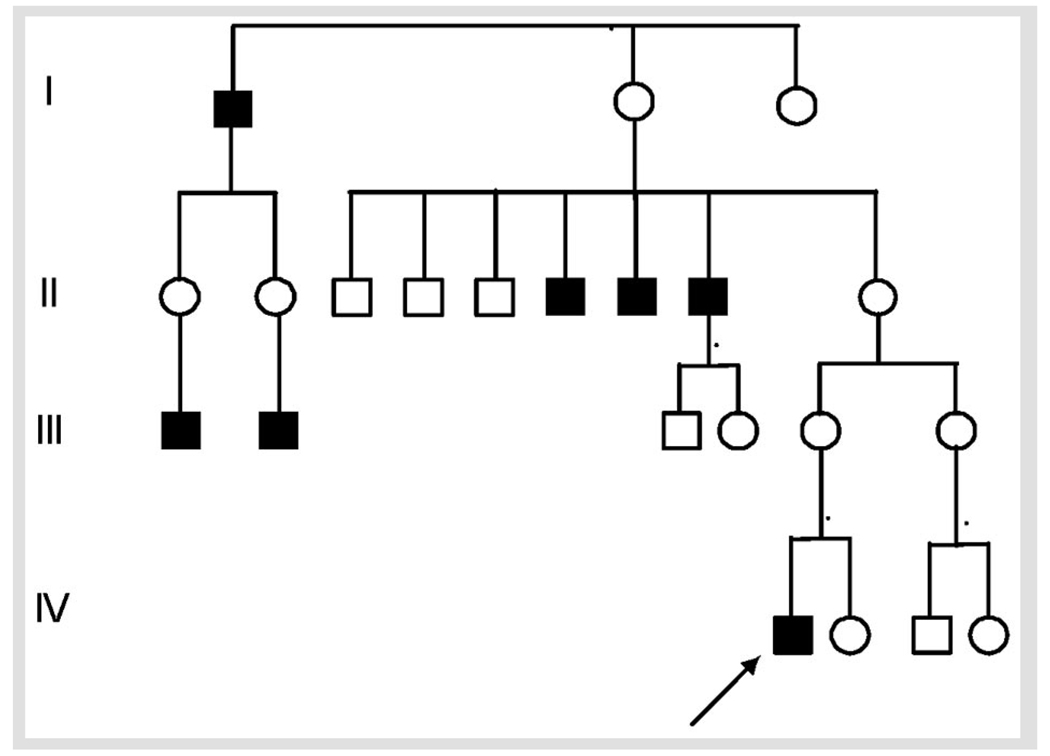

Family history was significant for five similarly affected male relatives (Figure 3-3): three brothers of the patient’s maternal grandmother and two sons of unaffected sisters of the patient’s maternal grandmother.

Deficits on examination are referable to corticospinal tracts serving bilateral lower extremities.

Diagnosis

X-linked hereditary spastic paraplegia due to mutation in the proteolipid protein gene (SPG2 mutation T673C).

Comment

Proteolipid protein (PLP) is an intrinsic myelin protein involved in myelin compaction. PLP gene mutations cause both X-linked dysmyelinating disorder Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease and X-linked HSP (SPG2 HSP). Some mouse models of PLP missense mutation exhibit progressive axonal degeneration rather than dysmyelination (Garbern et al, 2002). This illustrates the important concept that axonal degeneration may arise not only because of primary abnormalities within axons, but also as the consequence of primary glial abnormality (oligodendroglia in this case). It is also noteworthy that the particular mutation identified in this subject (PLP T673C) has also been reported in subjects with the severe, early-onset leukodystrophy phenotype. The presumed genetic modifying factors that influence marked phenotype variability that may be associated with PLP gene mutations have not been identified.

CONCLUSION

The clinical and genetic diversity of hereditary myelopathies limits useful generalizations. Nonetheless, it is notable that in the patients described above (with MJD/SCA3, X-linked HSP due to SPG1/PLP mutation, dominantly inherited HSP due to SPG3A/atlastin and SPG6/NIPA1, AMN, Fried-reich ataxia, and juvenile PLS), spastic gait disturbance was an early and prominent symptom. (It was the first symptom in each patient except the subject with AMN, for whom lower extremity paresthesiae preceded gait disturbance.) Identifying associated features (eg, subtle dorsal column signs in HSP, marked dorsal column impairment in Friedreich ataxia, peripheral neuropathy in AMN) is essential to clinical recognition of these disorders.

KEY POINTS

Hereditary myelopathic syndromes can be recognized as four clinical paradigms: (1) spinocerebellar ataxia, (2) motor neuron disorder, (3) leukodystrophy, and (4) dista motor-sensory axonopathy.

Neurologic involvement in nearly all hereditary myelopathies includes structures outside of the spinal cord.

Spinocerebellar degenerations (eg, Friedreich ataxia, Machado-Joseph disease [spinocerebellar ataxia type 3], Bassen-Kornzweig syndrome, and vitamin E deficiency [occasionally familial]) are recognized by a combination of progressive cerebellar ataxia, peripheral neuropathy and dorsal column impairment, and variable corticospinal tract involvement.

The vast majority of patients with Friedreich ataxia are homozygous for expanded trinucleotide repeat in the frataxin gene, which encodes a mitochondria protein.

Machado-Joseph disease/spinocerebellar ataxia type 3 is due to trinucleotide repeat (CAG) expansion that, like other polyglutamine expansions, is thought to be pathogenic through protein misfolding.

In primary lateral sclerosis, there is either no evidence of lower motor neuron involvement or at most, minimal evidence on EMG of chronic denervation late in the disease. At the other extreme, spinal muscular atrophy is characterized by muscular weakness and atrophy due to anterior horn cell degeneration with preservation of corticospinal tracts.

Childhood-onset adrenoleuko-dystrophy (ALD) and adolescent-and adult-onset adrenomyelo-neuropathy (AMN) are X-inked disorders in which ABCD1 gene mutation leads to impaired peroxisomal β-oxidation and accumulation of very long chain fatty acids systemically.

ALD/AMN phenotypes nclude rapidly progressive childhood, adolescent, and adult cerebra forms; slowly progressive myelopathic forms (characterized by slowly progressive spastic paraparesis and peripheral neuropathy, often with complete sparing of the brain); and solated adrenal insufficiency.

Demyelinating periphera neuropathy, which typically accompanies childhood-onset leukodystrophies (eg, Krabbe disease and metachromatic leukodystrophy) may be absent in the rare, adolescent-and adult-onset forms of these disorders.

SPG3A/ atlastin gene mutation is the most common cause of childhood-onset, autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia.

Clinical distinction of leukodystrophies from axonopathies is based on the presence of additional neurologic findings, particularly sensory disturbance. Patients with generalized leukodystrophies classically (although not always) also have demyelinating peripheral neuropathy.

Sensory impairment in motor-sensory axonopathies (eg, hereditary spastic paraplegia) is limited typically to mild dorsal column impairment affecting longer fibers (fasciculus gracilis) predominantly, and manifest as impaired vibration perception in the toes with preservation of other sensory modalities.

Distal motor-sensory axonopathy of the CNS (eg, uncomplicated hereditary spastic paraplegia) can be considered analogous to Charcot-Marie-Tooth type 2 disease, in which distal motor-sensory axonopathy is limited to the peripheral nervous system.

Clinically available genetic testing can diagnose approximately 65% of dominantly inherited hereditary spastic paraplegia and two forms of X-linked hereditary spastic paraplegia (due to mutations in proteolipid protein and L1 cell adhesion molecule genes).

SPG4/spastin mutations are the most common cause of dominantly inherited hereditary spastic paraplegia.

Proteolipid protein gene mutations cause both the X-linked dysmyelinating disorder Pelizaeus-Merzbacher disease, and X-linked hereditary spastic paraplegia (SPG2 HSP).

FIGURE 3-1.

Machado-Joseph disease (spinocerebellar ataxia type 3).

FIGURE 3-2.

Autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia due to NIPA1 gene mutation.

Reprinted with permission from Rainier S, Chai JH, Tokarz D, et al. NIPA1 gene mutations cause autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia (SPG6). Am J Hum Genet 2003;73(4):967–971. Copyright © 2003, Elsevier.

FIGURE 3-3.

X-linked spastic paraplegia due to PLP gene mutation.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Additional Contributions: The patient in Case 3-1 was evaluated with James Burke, MD, and Talia Siman-Tov, MD, Department of Neurology, University of Michigan; the patient in Case 3-2 was evaluated and synopsis prepared with Simon Fishman, MD, Alexandria, VA. Genetic analysis of the patient in Case 3-7 was performed by Grace M. Hobson, PhD, Molecular Diagnostics Laboratory, AI duPont Hospital for Children, DE; genetic analysis of the patients in Case 3-5 and Case 3-6 was performed by Shirley Rainier, PhD, Department of Neurology, University of Michigan.

I am grateful for the assistance of patients and their families without whom this work would not be possible. This research is supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (R01NS053917), the Department of Veterans Affairs (Merit Review Awards), and the Spastic Paraplegia Foundation.

Footnotes

Relationship Disclosure: Dr Fink has received personal compensation from Athena Diagnostics, Inc. Dr Fink has received royalty payments for atlastin and NIPA1 patents.

Unlabeled Use of Products/Investigational Use Disclosure: Dr Fink has nothing to disclose.

REFERENCES

- Bruyn GW, Went LN. A sex-linked heredo-degenerative neurological disorder, associated with Leber’s optic atrophy.I. Clinical studies. J Neurol Sci. 1964;54:59–80. doi: 10.1016/0022-510x(64)90054-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fink JK. Hereditary spastic paraplegia. In: Rimoin D, Connor JM, Pyeritz RE, Korf BR, editors. Emery and Rimoin’s principles and practice of medical genetics. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Churchill Livingstone; 2007a. pp. 2771–2801. [Google Scholar]

- Fink JK. The hereditary spastic paraplegias. In: Rosenberg RN, DiMauro S, Paulson HL, et al., editors. The molecular and genetic basis of neurologic and psychiatric disease. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007b. [Google Scholar]

- Garbern JY, Yool DA, Moore GJ, et al. Patients lacking the major CNS myelin protein, proteolipid protein 1, develop length-dependent axonal degeneration in the absence of demyelination and inflammation. Brain. 2002;125(pt 3):551–561. doi: 10.1093/brain/awf043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene E, Mahishi L, Entezam A, et al. Repeat-induced epigenetic changes in intron 1 of the frataxin gene and its consequences in Friedreich ataxia. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35(10):3383–3390. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkm271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon G, Fattal-Valevski A, Kolodny EH. Leukodystrophies: clinical and genetic aspects. Top Magn Reson Imaging. 2006;17(4):219–242. doi: 10.1097/RMR.0b013e31804c99d4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moser HW, Mahmood A, Raymond GV. X-linked adrenoleukodystrophy. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007;3(3):140–151. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasinelli P, Brown RH. Molecular biology of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: insights from genetics. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(9):710–723. doi: 10.1038/nrn1971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulson HL. Dominantly inherited ataxias: lessons learned from Machado-Joseph disease/ spinocerebellar ataxia type 3. Semin Neurol. 2007;27(2):133–142. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-971172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainier S, Chai JH, Tokarz D, et al. NIPA1 gene mutations cause autosomal dominant hereditary spastic paraplegia (SPG6) Am J Hum Genet. 2003;73(4):967–971. doi: 10.1086/378817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainier S, Sher C, Reish O, et al. De novo occurrence of novel SPG3A/atlastin mutation presenting as cerebral palsy. Arch Neurol. 2006;63(3):445–447. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheper GC, van der Klok T, van Andel RJ, et al. Mitochondrial aspartyl-tRNA synthetase deficiency causes leukoencephalopathy with brain stem and spinal cord involvement and lactate elevation. Nat Genet. 2007;39(4):534–539. doi: 10.1038/ng2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Hentati A, Deng HX, et al. The gene encoding alsin, a protein with three guanine-nucleotide exchange factor domains, is mutated in a form of recessive amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Genet. 2001;29(2):160–165. doi: 10.1038/ng1001-160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]