Abstract

The complete knockout of the acetylcholinesterase gene (AChE) in the mouse yielded a surprising phenotype that could not have been predicted from deletion of the cholinesterase genes in Drosophila, that of a living, but functionally compromised animal. The phenotype of this animal showed a sufficient compromise in motor function that precluded precise characterization of central and peripheral nervous functional deficits. Since AChE in mammals is encoded by a single gene with alternative splicing, additional understanding of gene expression might be garnered from selected deletions of the alternatively spliced exons. To this end, transgenic strains were generated that deleted exon 5, exon 6, and the combination of exons 5 and 6. Deletion of exon 6 reduces brain AChE by 93% and muscle AChE by 72%. Deletion of exon 5 eliminates AChE from red cells and the platelet surface. These strains, as well as knockout strains that selectively eliminate the AChE anchoring protein subunits PRiMA or ColQ (which bind to sequences specified by exon 6) enabled us to examine the role of the alternatively spliced exons responsible for the tissue disposition and function of the enzyme. In addition, a knockout mouse was made with a deletion in an upstream intron that had been identified in differentiating cultures of muscle cells to control AChE expression. We found that deletion of the intronic regulatory region in the mouse essentially eliminated AChE in muscle and surprisingly from the surface of platelets. The studies generated by these knockout mouse strains have yielded valuable insights into the function and localization of AChE in mammalian systems that can not be approached in cell culture or in vitro.

Keywords: acetylcholinesterase, knockout mouse, differentiation, alternative splicing

1. Introduction

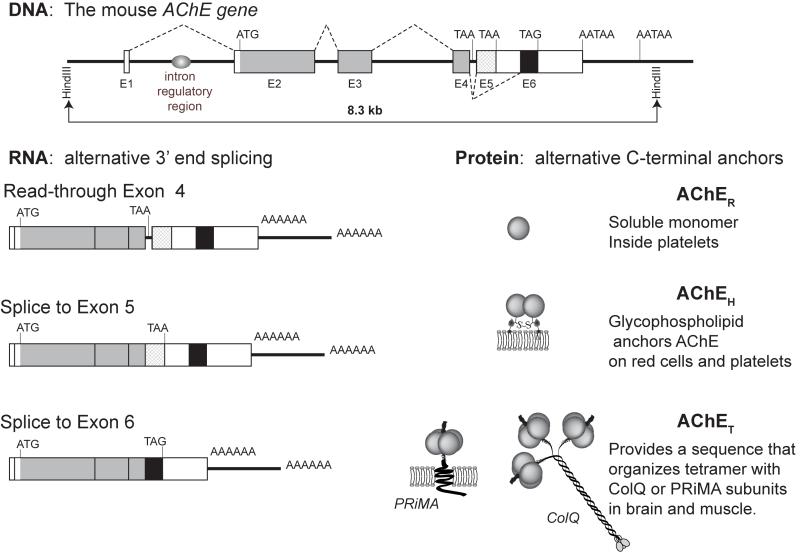

The mammalian AChE gene as it is expressed in muscle spans only 8.5kb of genomic sequence [1]. The splicing of exons 2-4 is invariant, and the translated amino acid sequence from these three exons forms the catalytic core of the enzyme. The catalytic activity of the enzyme is not affected by the sequences that are responsible for its anchoring to extracellular locations [2]. The alternatively spliced sequences (a retained intron or read through after exon 4, splices to exon 5 and exon 6) are regulated by tissue specific alternative splicing (Fig 1). Fig 1 also shows the AChE subunits PRiMA and ColQ which are responsible not only for the tissue specific distribution of AChE, but are also important in its regulation [3].

Fig.1.

The short span of the ACHE gene is shown contained within an 8.5kb Hind III restriction fragment of mouse genomic DNA [1]. Consistent to all forms of AChE is the invariant splicing of exons 2, 3 and 4 which produces the message which encodes the catalytic core of the enzyme. The AChE gene includes three alternative 3′ end splices for AChE mRNA. Reading through the 3′ end of exon 4 encodes mRNA for soluble AChE monomers. The splice to exon 5 produces mRNA that encodes glycophospholipid linked AChE that is found on the surface of red cells and platelets. The splice to exon 6 produces mRNA for the most commonly studied form of the enzyme which is found in brain and muscle. Multimers of tetramers of the AChE subunit translated from exon 6 spliced mRNA are tethered in place by ColQ and PRiMA subunits in brain and muscle.

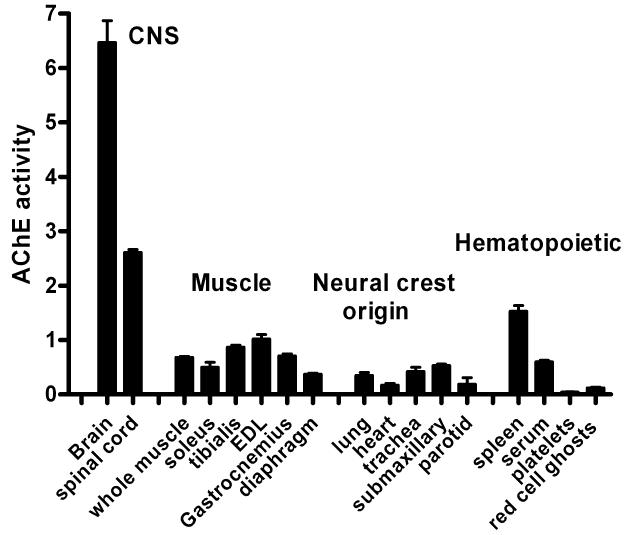

The enzyme, AChE, is widely distributed throughout the body; Figure 2 shows relative WT AChE activity in a number of organs in the mouse. The AChE species derived from the splice to exon 6 (AChET) is found at the highest relative concentrations in brain and other tissues of the central nervous system where the enzyme plays an important role in interneuronal synapses, and in muscle where AChET is concentrated at neuro-muscular synapses. Also of interest, because of its relative abundance, is the AChE that is found in the hematopoietic system, the alternative splice to exon 5 produces AChEH, the glycophospholipid anchored dimer that is found on the surface of platelets and red blood cells. Read-through into the intron after exon 4 translates to a soluble monomer, AChER, found in platelets [4], but seen in very minor abundance elsewhere. AChER has also been reported to be involved in the stress response [5]

Fig. 2.

AChE activity in tissues and blood of the WT mouse (mixed strain, WT littermates of knockout mice). Tissue AChE activity is reported as U AChE /g tissue. Serum is reported as U AChE/ml serum, platelets and red cell ghost values are reported as U AChE/ml blood.

Knockout of the complete acetylcholinesterase gene (AChE) in the mouse [6] produced a living, but compromised animal. The basis for this phenotype might have been rationalized as a selective increase in the other cholinesterase gene, butyrylcholinesterase (BChE), yet the findings of Lockridge and colleagues showed insignificant changes in BChE activity in the knock-out strain.[7]. As information accumulates from the total gene knockout mouse, it becomes evident that adaptation throughout development keeps the mouse alive [8, 9]. However, the total knockout mouse shows sufficient compromise in motor function reflected in tremors and difficulty in chewing and feeding, as well as metabolic alterations that are revealed by thermoregulation problems during postembryonic development [10] that a precise characterization of the phenotype in central and peripheral nervous function is precluded.

It was our hope that with the knockout of alternatively spliced exons, we could address the some of the issues of the compromised total knockout phenotype, while answering other questions about regulation and tissue distribution of AChE. With the deletion of exon 5: what would happen without the glycophospholipid anchor? Would alternative splicing cause the utilization of a different anchoring exon, or would the mouse be left with no hematopoietic AChE activity? With the deletion of exon 6 we would be compromising AChE activity in both brain and muscle. Although all of the alternative splice knockouts were able to produce AChER, could unanchored species compensate even partially for the precise synaptic localization that exon 6 affords?

Lastly, with the deletion of a 250bp intronic region 5′ of exon 2 (Fig. 1) that eliminated a differentiation dependent increase in AChE activity from the transfected AChE gene in C2C12 myoblasts [11], we hoped to answer a number of questions. Would AChE activity be absent in muscle as predicted by the cultured cells? Would CNS and muscle AChE be affected equally? With the potential knowledge that exon 6 spliced AChE was affected, what would happen to the expression of exon 5 spliced AChE?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Knockout mice

Concepts used in the generation of the knock-out mice are described by Joyner (2000).

2.2 The knockout mice are full described in the following articles

Total AChE knockout mouse [6, 7], AChE del E5, del E6, del E5+6 [12], AChE intron regulatory region (AChE i1rr) [13], ColQ knockout [14], and PRiMA knockout [3].

2.3 Humane treatment of animals

Knock-out mice. All experiments were performed in accordance with the University of California at San Diego’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (National Institutes of Health assurance number A3033-1; United States Department of Agriculture Animal Research Facility registration number 93-R-0437).

2.4 Tissue AChE activity

Tissue activity is expressed as units of AChE activity per gram of tissue, where one Unit (U) is defined as one micromole acetylthiocholine hydrolyzed per min. AChE was extracted by powdering tissue in a mortar and pestle at liquid nitrogen temperatures and then homogenizing the powder, on ice, in 0.01 M NaPO4 buffer, pH 7.0, with 1.0 M NaCl, 0.01 M EGTA, and 0.5% Tween 20, supplemented with the same quintet of protease inhibitors used in the C2C12 assays described in [13]. Muscle and spinal cord were homogenized in 25 volumes of buffer and brain in 10 volumes. The supernatants of 12,000 x g 10 min centrifugations were assayed for activity as described above. Ethopropazine (10μM) was used to inhibit butyrylcholinesterase (BChE).

2.5 Red cell ghost AChE activity

Red cell ghosts were prepared essentially as in the study by Dodge et al. [15]. Blood drawn by cardiac puncture into sodium citrate was initially spun at 2400 x g for 5 min at 4°C. Washed red cell ghosts were then sonicated. Activity is reported as units of AChE per ml of blood drawn.

2.6 Platelet AChE activity

Platelets, virtually free of red and white cells, were collected from citrated blood on OptiPrep gradients (Axis-Shield,Oslo, Norway). Iodixanol-NaCl/HEPES gradients were prepared by dilution of the OptiPrep stock to a density of 1.063 g/ml. Blood was applied to the diluted gradient material and spun at 600 rpm for 15 min at 22°C with no brake. Platelet rich plasma (PRP) was collected and spun at 450 x g for 10 min to collect platelets. Platelets were washed, maintained, and assayed in modified HEPES/Tyrode’s buffer (10mM HEPES, 137mM NaCl, 2.8 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 12 mM NaHCO3, 0.4 mM Na2HPO4, 0.1% BSA, 5.5 mM glucose, pH 7.4) to minimize platelet activation and measure surface AChE only. Activities in this modified buffer were corrected for reduced catalytic efficiency.

2.7 Real-time reverse transcription-PCR

Tissues were disrupted with mortar and pestle and then homogenized by sonication. After digesting with Proteinase K, total cellular RNA was purified with an RNeasy Midi kit (Qiagen, Leusden, The Netherlands). DNase I turbo treatment (Ambion) was used to avoid genomic DNA contamination. RNA was reverse transcribed into single-stranded cDNA using the Superscript First-Strand System (Invitrogen). The resulting cDNA was subjected to real time reverse transcription (RT)-PCR using SYBR Green and amplified for 40 cycles with 15 s at 95°C and 60 s at 60°C in the ABI Prism 7700 Sequence Detector System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). After amplification, the sequence was confirmed by melting curve analysis. All assays were run in duplicate, and the mean was analyzed from three to six mice. The relative abundance of mRNAs was normalized to cyclophilin mRNA for each sample set. Differences between the wild-type and knock-out animal strains were calculated by the comparative Ct method [16]. The AChE (exon 2-exon 3) primer set used to amplify the AChE message is described in the supplemental material available in [13].

3. Results

3.1 AChE gene expression: alternative exon deletions

Since AChE in mammals is encoded by a single gene with alternative splicing which results in tissue specific expression, additional understanding of gene expression might be garnered from selected deletions of the alternatively spliced exons, 5 and 6.

To this end, knockout strains were generated that deleted exon 5, exon 6, and the combination of exons 5 and 6 [12]. These three strains should enable us to examine the role of exon 5, exon 6 and exon 4 (retained intron) in the disposition and function of the enzyme. AChE expression in brain and muscle of the exon deleted null mice is shown in Table 1. The deletion of exon 5 affects the expression of AChE in brain or muscle somewhat, while the deletion of exon 6 reduces brain AChE by 97% and muscle AChE by 67%. The deletion of both exons in the AChE del E5+6 mouse confirms that the dominant AChE species in these tissues is derived from the splice to exon 6 as the reduction in AChE activity in both brain and muscle mirrors that of the AChE del E6 mouse.

Table 1.

AChE activity in whole brain devoid of spinal cord and in leg muscle. AChE activity in WT and exon deleted mice. AChE activity is reported as U/g tissue ± standard deviation for >3 animals

Since the splice from exon 4 to exon 5 produces the GPI anchored AChE found on platelets, it is not surprising that deletion of this exon produces mice with no AChE activity on the surface of either platelets or red blood cells (Table 2). The effects of the deletion of exon 6, however, are not quite so straight-forward. Surface AChE expression on platelets and red cells is reduced, but not to the same extent (60% reduction for red cells, but an 80% reduction on the surface of platelets, with a 2-fold increase in the levels of AChE found within the platelets). Such complexity arising from exon deletion certainly suggests that the exons themselves are a part of the paradigm which regulates AChE activity in divergent tissues.

Table 2.

AChE activity associated with hematopoietic cells in WT and AChE knockout mice. AChE activity is reported as U/ml blood ± standard deviation for >3 animals. WT AChE activities represent the average of values taken from WT littermates of the (−/−) mice

| Erythrocyte ghosts |

Platelet surface |

Platelet interior | Platelet poor plasma |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT* | 0.12 ± 0.05 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 0.05 ± 0.03 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

| Del E5 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 ± 0.002 | 0.03 ± 0.01 |

| Del E5+6 | 0 | 0 | 0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.09 ± 0.02 |

| Del E6* | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 0.10 ± 0.04 | 0.06 ± 0.02 |

| Intron 1-rr floxed* |

0.11 ± 0.04 | 0.04 ± 0.03 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.03 ± 0.004 |

| Intron 1-rr deleted* |

0.10 ± 0.03 | 0 | 0 | 0.01 ± 0.003 |

Data denoted by has been previously reported in [13].

3.2 AChE gene expression: muscle specific intron deletion

The knockout mouse strain with a 250 bp deletion in the intronic region upstream of exon 2 (AChE i1rr) was constructed in order to verify a series of experiments in C2C12 mouse muscle myoblasts that identified the 250bp region to be critical in AChE expression during early muscle differentiation The deleted region, which is well conserved in a number of species in the mammalian AChE gene, proved to contain several concise sequences required for AChE expression [12], but interestingly this region, while critical in muscle and platelets, plays no role in AChE expression in brain or red cells. Table 3 shows the influence of this intronic region in AChE gene expression on a number of tissues, while Table 2 shows the effect of the deletion in red cells and platelets.

Table 3.

Tissue AChE activities in WT and AChEi1rr deleted mice. AChE activity is reported as U/g tissue ± SD for >3 animals. Mice selected for this study were littermates

| WT (+/+) | AChEi1rr (−/−) | % WT | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNS | |||

|

| |||

| brain* | 6.47 ± 1.38 | 5.50 ± 0.39 | 85 |

| spinal cord* | 2.61 ± 0.09 | 3.05 ± 0.18 | 117 |

|

| |||

| Muscle | |||

|

| |||

| Whole leg muscle* | 0.68 ± 0.07 | 0.01 ± 0.007 | 2 |

| soleus | 0.50 ± 0.22 | 0.02 ± 0.02 | 4 |

| tibialis | 0.87 ± 0.09 | 0.01 ± 0.01 | 1 |

| EDL | 1.02 ± 0.20 | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 3 |

| gastrocnemius | 0.65 ± 0.08 | 0.03 ± 0.02 | 4 |

| diaphragm | 0.37 ± 0.04 | 0 | 0 |

|

| |||

| Neural Crest Origin | |||

|

| |||

| lung | 0.32 ± 0.05 | 0.09 ± 0.02 | 28 |

| heart | 0.17 ± 0.03 | 0.06 ± 0.02 | 35 |

| trachea | 0.53 ± 0.13 | 0.13 ± 0.05 | 24 |

| submaxillary | 0.60 ± 0.16 | 0.52 ± 0.04 | 87 |

| parotid | 0.20 ± 0.05 | 0.12 ± 0.02 | 60 |

Data denoted by has been previously reported in [13].

3.3 Comparing AChE mRNA and activity in AChE del E6 and AChEi1rr knockout mice

Contributions of transcription/ RNA stability and translation/ protein processing and stability are discussed in [13]. In the AChE i1rr (−/−) mouse, there is little or no AChE mRNA in muscle (2% of WT) and consequently no AChE activity (<3% of WT), but both mRNA (88% of WT) and activity (125% of WT) are within the normal range in brain.

The deletion of exon 6 presents a much more complex picture, for deletion of this exon affects not only mRNA levels, with brain mRNA (25% of WT) being impacted more severely than that in muscle (80% of WT), but also provides evidence that AChE protein, without the ability to anchor properly in its synaptic space, is degraded (muscle, 33% of WT activity; brain, 3% of WT activity). The levels of AChE activity are reduced far more than the mRNA levels. The potential of transcriptional regulation by enhancer sequences in coding regions of the AChE gene is discussed in [17]

3.4 Knockout mice with deletions of AChE anchoring subunits, ColQ and PRiMA

In addition to the collection of AChE gene knockout mice, knockout strains of the two anchoring subunits, ColQ [14], and PRiMA [3] have also been established, and have provided a parallel avenue which allows detailed study of tissue specific regulation and localization of AChE in ways not possible with the exon specific knockout strains. Since both CNS and muscle AChE contain a common C-terminal sequence which contains the WAT (‘tryptophan amphiphilic tetramerization’) domain derived from the translation of exon 6, the differential distribution and regulation of these AChEs should be studied through their tissue specific anchoring subunits, PRiMA and ColQ [18].

As has been shown in brain [3], both the WAT domain of AChE provided by exon 6 as well as the presence of PRiMA are required for the high concentrations of AChE seen in the striatum. Regulation is seen at the level of protein trafficking and stabilization. Indeed in the PRiMA knockout, AChE is only 2% of WT at the protein level whereas there is no change at mRNA. This 2% of AChE is found in the endoplasmic reticulum because it is retained by the WAT domain looking for an absent binding partner. Deletion of the WAT domain allows the progression of AChE into the secretory pathway, however, the absence of interaction with PRiMA prevents AChE accumulation on the cell surface. The surprising consequence of this deletion is the absence of an obvious phenotype in the mouse despite the complete absence of AChE on the surface of the neuron [3].

Selective knockout of the ColQ gene enables one to eliminate all the collagen tailed forms and almost all synaptic or junctional AChE [14]. As previously suggested by treatment with collagenase however, AChE is still abundant in the muscle extract of the knockout animal. Consequently knockout of the ColQ gene allows the analysis of PRiMA anchored forms of the enzyme.

Thus, selective knockout of the ColQ gene enables one to examine residual synaptic or junctional AChE where the collagen-linked form is normally heavily concentrated. Deletion of the PRiMA gene allows one to examine mice with synaptic ColQ expression retained and extrajunctional and perijunctional AChE deleted, and the deletion of exon 6 enables one to assess the C-terminal sequences to which both structural subunits attached. This complementary group of knockout animals thus allows the study of the structural and functional consequences of removal of junctional and extrajunctional AChE as well as permitting the analysis of the respective AChE levels.

4. Discussion

The alternatively spliced AChE gene exon knockouts (del E5, del E6. del E5+6), the intron 1 regulatory region knockout (AChEi1rr) and the total gene knockout AChE(−/−), along with the anchoring subunit knockouts of ColQ and PRiMA have provided information that allows precise localization of the multiple forms of AChE as well as information that enables us to understand some of the aspects of gene regulation as well as regulation through protein trafficking. Some mysteries have been revealed, others remain to be solved.

4.1 Exon specific deletions

The observable characteristics that define the phenotypes of the knockout animals (Table 4) showed that the deletion of exon 5 caused no directly visible changes. The exon 5 deleted mouse seems physically indistinguishable from its WT littermates. The fact that AChE expression is lower in both brain and muscle of the exon 5 knockout demands further investigation as the amount of glycophospholipid-linked AChEH thought to be expressed in these tissues is low [19]. The deletion of exon 6, however produced a mouse that was challenged on many levels. As would be expected with very low levels of AChE activity in brain and muscle, these knockout mice lived with constant tremors from birth, making it impossible to assess their capabilities with simple tests that required physical coordination. The mouse with exons 5 and 6 deleted reflects the phenotype of the more extreme exon 6 deletion, but in addition seems to be reproductively challenged. The exon 5+6 deleted mouse does tell us emphatically, however, that exon 5 is not able to replace exon 6 in the most critical tissues where AChE is expressed: AChE levels are nearly identical in the muscles of both the exon 6 and exons 5+6 knockout mouse, moreover the del E5+6 knockout mouse has more AChE in brain than does the exon 6 deleted knockout.

Table 4.

Observed phenotypes of knockout mice: body size, body tremors and ability to reproduce are shown

| Knockout | Body size |

Body tremors |

Can (−/−) reproduce? |

|---|---|---|---|

| AChE (−/−) | tiny | +++ | No |

| Del E5 | normal | None | As normal |

| Del E5+6 | Small | +++ | Very rarely |

| Del E6 | small | +++ | Near normal |

| Intron 1-rr del |

Near normal |

+++ | ~ 50% of matings are productive |

Study of hematopoietic AChE begins to reveal the complex regulation of the AChE gene. Why are exon 5 spliced AChE species reduced in the exon 6 deleted mouse? Exon 5 spliced mRNA contains exon 6 as untranslated 3′ noncoding sequence and must contain regulatory sequences for the expression of exon 5 spliced mRNA species on platelets and red cells. Moreover, why does the deletion of exon 6 produce a > 2 fold increase in the AChE activity inside platelets? In this case inhibitory regulatory elements are likely contained within the exon 6 sequences. Although regulatory elements seen in the 3′ untranslated region of AChE have been described in detail [20], the tissue specific nature of such regulation could only have been seen in the whole animal and emphasizes one of the most important features of these mouse studies: AChE regulation at all levels from transcription to translation comes from a complex set of interactions that change with development and tissue type.

4.2 Intron regulatory region deletion

The AChEi1rr mouse gives us information that could only come from the whole animal. Although the mouse muscle derived cell line, C2C12, showed that the 250bp intron 1 regulatory region regulated AChE expression during differentiation, it took the knock out mouse to present unequivocally that the regulatory or enhancer region in the first intron was functional in muscle and surprisingly in platelets, but was not functional in the interneuron synapses in brain and the spinal cord. The odd pairing of AChE regulatory patterns which is found in muscle and platelets, where AChE expression is completely ablated by deletion of a rather short region in the first intron, points to a regulatory region that controls expression in skeletal muscle, but in only a portion of the hematopoietic system. This region can surely be labeled an enhancesome, a grouping of multiple regulatory regions that are critical for AChE expression in muscle [13]. The classical pairing of binding sites for the transcription factors myocyte enhancer 2 (MEF2) and MyoD [21-23], along with a third region within the enhancesome [24], control AChE expression in muscle during development [13]. We have not yet identified the sequences within the enhancesome that are responsible for AChE expression on the platelet surface or ascertained whether they differ from those controlling muscle expression.

4.3 ColQ and PRiMA knockout mice

This constellation of knockout strains yielded several more global observations, some of which depend on more detailed phenotyping conducted by various groups in France [3]. In the neuromuscular junction virtually all the AChE expressed in synapses comes from secretion by the muscle as a complex of AChE/ColQ, and not from axoplasmic flow down the nerve to the nerve ending [14]. Surprisingly the overall phenotype of the ColQ knockout appears more severe than that of the AChE 1irr knockout in which AChE is absent [13, 14] suggesting a possible supporting a role for butyrylcholinesterase which is also anchored by ColQ at the NMJ [25]. Conversely, the marked reduction and redistribution of AChE in the brain of the PRiMA knockout produces little change in gross phenotype where knockouts appear indistinguishable from WT mice.

Conclusions

The selective knock-out studies have taken us a long way to understanding expression in the intact animal, but given that a single gene subserves cholinergic neurotransmission the entire CNS and the autonomic and somatic motor (voluntary muscle) system, more remains to be uncovered related to control of expression in regional areas of the nervous system.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by USPHS grants R37GM 18360 and P42ES10337 to PT and by Inserm, Association Francaise contre les Myopathies (AFM) and Agence Nationale de la Recherche (ANR Maladies Rares) to E.K.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- [1].Li Y, Camp S, Rachinsky TL, Getman D, Taylor P. Gene structure of mammalian acetylcholinesterase. Alternative exons dictate tissue-specific expression. J Biol Chem. 1991;266(34):23083–23090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Taylor P, Radic Z. The cholinesterases: from genes to proteins. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1994;34:281–320. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.34.040194.001433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Dobbertin A, Hrabovska A, Dembele K, Camp S, Taylor P, Krejci E, Bernard V. Targeting of acetylcholinesterase in neurons in vivo: a dual processing function for the proline-rich membrane anchor subunit and the attachment domain on the catalytic subunit. J Neurosci. 2009;29(14):4519–4530. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3863-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Chuang HY, Mahammad SF, Mason RG. Acetylcholinesterase, choline acetyltransferase, and the postulated acetylcholine receptor of canine platelets. Biochem Pharmacol. 1976;25(17):1971–1977. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(76)90052-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Deutsch VR, Pick M, Perry C, Grisaru D, Hemo Y, Golan-Hadari D, Grant A, Eldor A, Soreq H. The stress-associated acetylcholinesterase variant AChE-R is expressed in human CD34(+) hematopoietic progenitors and its C-terminal peptide ARP promotes their proliferation. Exp Hematol. 2002;30(10):1153–1161. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(02)00900-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Xie W, Wilder PJ, Stribley J, Chatonnet A, Rizzino A, Taylor P, Hinrichs SH, Lockridge O. Knockout of one acetylcholinesterase allele in the mouse. Chem Biol Interact. 1999;119-120:289–299. doi: 10.1016/s0009-2797(99)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Li B, Stribley JA, Ticu A, Xie W, Schopfer LM, Hammond P, Brimijoin S, Hinrichs SH, Lockridge O. Abundant tissue butyrylcholinesterase and its possible function in the acetylcholinesterase knockout mouse. J Neurochem. 2000;75(3):1320–1331. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.751320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Chatonnet F, Boudinot E, Chatonnet A, Taysse L, Daulon S, Champagnat J, Foutz AS. Respiratory survival mechanisms in acetylcholinesterase knockout mouse. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;18(6):1419–1427. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02867.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Adler M, Manley HA, Purcell AL, Deshpande SS, Hamilton TA, Kan RK, Oyler G, Lockridge O, Duysen EG, Sheridan RE. Reduced acetylcholine receptor density, morphological remodeling, and butyrylcholinesterase activity can sustain muscle function in acetylcholinesterase knockout mice. Muscle Nerve. 2004;30(3):317–327. doi: 10.1002/mus.20099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Sun M, Lee CJ, Shin HS. Reduced nicotinic receptor function in sympathetic ganglia is responsible for the hypothermia in the acetylcholinesterase knockout mouse. J Physiol. 2007;578(Pt 3):751–764. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.120147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Camp S, Taylor P. Intronic Elements Appear Essential for the Differentiation-Specific Expression of Acetylcholinesterase in C2C12 Myotubes. In: Doctor BP, Taylor P, Quinn DM, Rotundo RL, Gentry MK, editors. Structure and Function of Cholinesterases and Related Proteins. Plenum Press; New Youk: 1998. pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- [12].Camp S, Zhang L, Marquez M, de la Torre B, Long JM, Bucht G, Taylor P. Acetylcholinesterase (AChE) gene modification in transgenic animals: functional consequences of selected exon and regulatory region deletion. Chem Biol Interact. 2005;157-158:79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2005.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Camp S, De Jaco A, Zhang L, Marquez M, De la Torre B, Taylor P. Acetylcholinesterase expression in muscle is specifically controlled by a promoter-selective enhancesome in the first intron. J Neurosci. 2008;28(10):2459–2470. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4600-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Feng G, Krejci E, Molgo J, Cunningham JM, Massoulie J, Sanes JR. Genetic analysis of collagen Q: roles in acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase assembly and in synaptic structure and function. J Cell Biol. 1999;144(6):1349–1360. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.6.1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Dodge JT, Mitchell C, Hanahan DJ. The preparation and chemical characteristics of hemoglobin-free ghosts of human erythrocytes. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1963;100:119–130. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(63)90042-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Weill CO, Vorlova S, Berna N, Ayon A, Massoulie J. Transcriptional regulation of gene expression by the coding sequence: An attempt to enhance expression of human AChE. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2002;80(5):490–497. doi: 10.1002/bit.10392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Massoulie J, Bon S. The C-terminal T peptide of cholinesterases: structure, interactions, and influence on protein folding and secretion. J Mol Neurosci. 2006;30(1-2):233–236. doi: 10.1385/JMN:30:1:233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Cabezas-Herrera J, Moral-Naranjo MT, Campoy FJ, Vidal CJ. G4 forms of acetylcholinesterase and butyrylcholinesterase in normal and dystrophic mouse muscle differ in their interaction with Ricinus communis agglutinin. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1225(3):283–288. doi: 10.1016/0925-4439(94)90008-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Guerra M, Dobbertin A, Legay C. Identification of cis-acting elements involved in acetylcholinesterase RNA alternative splicing. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2008;38(1):1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Black BL, Molkentin JD, Olson EN. Multiple roles for the MyoD basic region in transmission of transcriptional activation signals and interaction with MEF2. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18(1):69–77. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Molkentin JD, Black BL, Martin JF, Olson EN. Cooperative activation of muscle gene expression by MEF2 and myogenic bHLH proteins. Cell. 1995;83(7):1125–1136. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90139-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Klamut HJ, Bosnoyan-Collins LO, Worton RG, Ray PN. A muscle-specific enhancer within intron 1 of the human dystrophin gene is functionally dependent on single MEF-1/E box and MEF-2/AT-rich sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25(8):1618–1625. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.8.1618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].L’Honore A, Rana V, Arsic N, Franckhauser C, Lamb NJ, Fernandez A. Identification of a new hybrid serum response factor and myocyte enhancer factor 2-binding element in MyoD enhancer required for MyoD expression during myogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(6):1992–2001. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Girard E, Bernard V, Minic J, Chatonnet A, Krejci E, Molgo J. Butyrylcholinesterase and the control of synaptic responses in acetylcholinesterase knockout mice. Life Sci. 2007;80(24-25):2380–2385. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]