Abstract

Cannabinoid-receptor antagonists have shown some promise as treatments capable of reducing abuse and relapse to a number of abused drugs. In rodents, such effects have been observed with methamphetamine self-administration. However, the effects of cannabinoid receptor antagonists on methamphetamine self-administration and relapse have not been studied in primates. In the present study, rhesus monkeys were trained to respond on a three-component operant schedule. During the first 5-min component, fixed-ratio responses were reinforced by food, during the second 90- or 180-min component fixed-ratio responses were reinforced by i.v. methamphetamine. The third component was identical to the first. There was a 5-min timeout between each component. The effects of the cannabinoid receptor antagonists AM 251 and rimonabant were tested at various doses against self-administration of 3 μg/kg/injection methamphetamine, and 1 mg/kg AM 251 and 0.3 mg/kg rimonabant were tested against the methamphetamine dose-effect function. The 1 mg/kg dose of AM 251 was also tested for its ability to alter reinstatement of extinguished self-administration responding. The cannabinoid receptor antagonist AM 251 was found to reduce methamphetamine self-administration at doses that did not affect food-reinforced responding. The cannabinoid receptor antagonist rimonabant had similar, but less robust effects. AM 251 also prevented reinstatement of extinguished methamphetamine seeking that was induced by re-exposure to a combination of methamphetamine and methamphetamine-associated cues. These results indicate that cannabinoid receptor antagonists might have therapeutic effects for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence.

Index Words: Cannabinoid, receptor antagonist, methamphetamine, self-administration, reinstatement, rhesus monkey

1. Introduction

Recent evidence suggests that the endocannabinoid system of the brain is involved in both the maintenance of drug taking behavior and relapse to drug taking after a period of abstinence (Beardsley et al. 2009; Fattore et al., 2007; Le Foll and Goldberg, 2005). Accordingly, cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists have been proposed as potential medications for the treatment of drug abuse. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist/inverse agonist rimonabant has gone through clinical trials for the treatment of nicotine dependence, and preclinical evidence suggests that cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists may also have utility in treating opioid and alcohol abuse (Beardsley et al., 2009; Solinas et al., 2007).

Cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists also show promise as treatments for the abuse of the psychostimulant cocaine (Tanda, 2007). Pretreatment with cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists can attenuate both drug- and cue-induced reinstatement of cocaine self-administration in rats (De Vries et al., 2001; Xi et al., 2006). However, rimonabant does not appear to reduce ongoing cocaine self-administration in either rodents (De Vries et al., 2001; Filip et al., 2006; Lesscher et al., 2005) or monkeys (Tanda et al., 2000).

Although it has received less research attention, cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists have also been proposed as treatments for the abuse of another psychostimulant, methamphetamine. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor knockout mice are hyporesponsive to d-amphetamine on tests of locomotor activity, providing evidence for a role of CB1 receptors in amphetamine abuse (Tzavara et al. 2009). Madsen et al. (2006) reported that rimonabant reverses amphetamine-induced arousal (as measured by trained observers) in monkeys. Like with cocaine, rimonabant has been shown to attenuate both drug- and cue-induced reinstatement of methamphetamine self-administration in rats (Anggadiredja et al., 2004). However, Boctor et al. (2007) found that another cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist, AM 251, did not attenuate methamphetamine-induced reinstatement of extinguished methamphetamine self-administration in rats. In contrast with the findings (mentioned above) that rimonabant does not reduce ongoing cocaine self-administration, AM 251 has been found to reduce ongoing methamphetamine self-administration in rats (Vinklerová et al., 2002). These results suggest that cannabinoid receptor antagonists might affect cocaine and methamphetamine abuse in different ways, and there may also be differences between the effects of specific antagonists, such as rimonabant and AM 251.

While research with rodents supports the utility of cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists in the treatment of psychostimulant abuse, this conclusion is tempered somewhat by the fact that rodents and primates can differ in their response to cannabinoids. For example, while it has been shown that primates will self-administer cannabinoid CB1 receptor agonists (Justinova et al., 2003, 2005; Tanda et al., 2000), evidence of cannabinoid self-administration in rodents is less clear. In fact, most studies in rodents have failed to report reliable self-administration (cf. Solinas et al., 2007). Although cannabinoid receptor function in rats and monkeys shows many similarities (Meschler et al. 2001), Ong and Mackie (1999) found major differences between rats and monkeys in the distribution of brain cannabinoid receptors. For example, primates appear to have higher densities of cannabinoid receptors in the cerebral cortex, hippocampus and cerebellar cortex than do rats. These findings suggest that cannabinoid receptor agonists, and by extension cannabinoid receptor antagonists, may act differently in rodents and primates for procedures highly dependent on learning and memory.

Therefore, the purpose of the current study was to investigate the effects of pretreatments with the cannabinoid receptor antagonist/inverse agonists rimonabant and AM 251 in rhesus monkeys self-administering methamphetamine. Effects of pretreatments were studied on both ongoing methamphetamine self-administration and on drug-induced reinstatement of behavior following extinction.

2. Materials

2.1. Animals

The subjects were 12 adult rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta). All monkeys but one (C225) were male. Each monkey was fed twice daily and maintained on a diet of monkey biscuits (Monkey Diet 5038, LabDiet, Brentwood, MO) and a variety of fresh fruit/vegetables in addition to banana-flavored pellets delivered during operant sessions (see below). The amount of food provided each day (typically 12–20 biscuits, with 8 banana-flavored pellets substituting for one biscuit) was adjusted according to the animal’s size to maintain a normal body weight. Water was freely available at all times. The monkeys were housed in a humidity and temperature controlled room with a 12 hr light-dark cycle (lights on from 6 a.m. to 6 p.m., E.S.T.).

Monkeys were surgically implanted (under aseptic conditions) with Silicone rubber catheters (inside diameter 0.8 mm; outside diameter 2.4 mm). Catheters were implanted into a jugular or femoral vein and exited in the midscapular region. The intravenous (i.v.) catheter was protected by a tether system consisting of a custom-fitted nylon vest and stainless steel harness, connected to a flexible stainless steel cable and fluid swivel (Lomir Biomedical, Montreal, Canada). This flexible tether system permitted the monkeys to move freely. Catheter patency was periodically evaluated by i.v. administration of ketamine (5 mg/kg). The catheter was considered patent if ketamine produced a loss of muscle tone within 10 seconds after its administration. Monkeys were also anesthetized with ketamine (10 mg/kg, i.m.) every other week to allow for cage changes and physical examination by a veterinarian. On these days, experimental sessions were suspended. When a catheter failed during the experiment, the catheter was surgically removed, the monkey was allowed to recover for at least 2 weeks, and then surgery was performed to implant a catheter in another available vein.

Animal maintenance and research were conducted in accordance with the NIH Guidelines for Using Animals in Intramural Research. The facility was accredited by the AAALAC, and protocols were approved by the NIDA-IRP Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Monkeys received environmental enrichment and had visual, auditory and olfactory contact with other monkeys throughout the study.

2.2. Apparatus

Each monkey was housed individually in a well-ventilated stainless steel cage (81 × 75 × 86 cm, Britz-Heidbrink, Weatland, WY). The cages were arranged in a one-over-one configuration. The tether mounted to the fluid swivel in the center of the back panel 62 cm above the cage floor. An 18 cm shelf ran along the back wall, 25 cm off the floor. This shelf allowed the monkeys to sit off the floor of the cage. The home cages of all monkeys were modified to include an operant-training panel (38 × 37 cm) mounted in the upper left corner of the front wall. Two circular translucent response keys (4.5 cm, PPC-003, BRS/LVE Laurel, MD) were arranged 9.0 cm apart (center to center) in a horizontal row 55 cm from the cage floor. The left key was 15 cm from the left wall. Each key could be transilluminated by a red or green stimulus light. The operant panel also supported an externally-mounted pellet dispenser (Gerbrands, Model G5310 or BRS/LVE series PDC/PPD) that delivered 1 gm banana-flavored food pellets (F0022, Bioserv, Frenchtown, NJ) to a food receptacle mounted on the cage beneath the operant response panel. Two infusion pumps (Model 55-7766, Harvard Apparatus, South Natick, MA) were situated behind each cage for delivery of saline or drug solutions through the intravenous catheter. One pump operated continuously (except during drug self-administration components) to deliver saline at a rate of 0.03 ml/min to maintain catheter patency. A second pump delivered self-administered drug. Operation of the operant panels, pumps and data collection were accomplished with a PC-compatible computer. The experimental sessions were controlled by customized software written in MedState Notation (Med Associates, St. Albans, VT).

2.3. General Procedure

Food and i.v. injections of methamphetamine were available during three alternating schedule components: an initial 5-min food component, a drug component (90 min, except for the 180-min component for monkey XDJ), and a second 5-min food component. Both food and i.v. injections were available under a fixed-ratio (FR 4–10) schedule of reinforcement. During the two food components, the response key was transilluminated red. During the drug component, the response key was transilluminated green. Which key (left or right) was illuminated and available for responding was counterbalanced across monkeys. Following the delivery of each food pellet or drug injection, there was a 10-sec timeout period, during which the stimulus light illuminating the response key was turned off and responding has no scheduled consequence. The food and drug components were separated by 5-min timeout periods, during which the response key was dark and responding had no scheduled consequences.

During training, the solution available for self-administration during the drug component was either 5 μg/kg/injection (monkeys C253, RQ5017, RQ4994, and C265) or 10 μg/kg/injection (monkeys C166, C265, RQ4339, RQ4988, CE5T, C254, SE045, and C225) methamphetamine. All self-administration injections were given in a volume of 0.5 ml and at a rate of 3.0 ml/min. Dose was adjusted by changing the concentration of the solution.

2.4. Effects of Pretreatments on Methamphetamine Self-Administration

Six monkeys (C166, C253, C254, RQ439, RQ4988, RQ5017) were maintained on methamphetamine self-administration throughout training. They were tested with various doses of AM 251, rimonabant and vehicle against a fixed self-administration dose of 3 μg/kg/injection of methamphetamine substituted for the training dose. Subsequently a fixed dose of AM 251 (1.0 mg/kg, i.v.), rimonabant (0.3 mg/kg, i.v.) or vehicle was tested against saline or various doses of methamphetamine substituted for the training methamphetamine dose on a single day. All dose testing was done in a random order within either test procedure. At least 2 days of baseline training separated each test condition. Vehicle or drug were administered i.v. 30 min prior to the session. Not all animals were tested under every condition.

2.5. Effects of AM 251 Pretreatment on Reinstatement of Methamphetamine Self-Administration

Six monkeys (C225, C254, CE5T, SE 045, RQ4994, XDJ) were tested on the reinstatement procedure. During extinction for four of these subjects (C225, C254, SE045, XDJ) saline was substituted for methamphetamine, but no other experimental conditions were changed (Extinction With Stimulus condition). Once response rates dropped to less than 20% of reinforced baseline for at least 5 days, animals were given vehicle or 1.0 mg/kg AM 251 i.v. 30 min prior to the session and then given saline or a priming injection of 0.1 mg/kg methamphetamine i.m. 15 min prior to the session. Saline continued to be available for self-administration during the drug component of the test session. On the days between test sessions, Extinction With Stimulus conditions were maintained until at least 2 days with less than 20% reinforced baseline responding occurred. Four test sessions were conducted in a random order for each subject.

Following all four tests, the animals were returned to the methamphetamine self-administration baseline for at least 2 weeks. For all six subjects saline was again substituted for methamphetamine, but the stimulus change that had been associated with the injection (turning off the key light) was not presented during extinction (Extinction Without Stimulus condition). Once response rates dropped to less than 20% of the reinforced baseline for at least 5 days, animals were given vehicle or 1.0 mg/kg AM 251 i.v. 30 min prior to the session and then given saline or a priming injection of 0.1 mg/kg methamphetamine i.m. 15 min prior to the session. Saline continued to be available for self-administration during the test session, and the stimulus change previously associated with the FR completion was again presented at the completion of each FR to test for cue-induced reinstatement. Following each test, saline continued to be available during self-administration sessions, but the stimulus change was not presented. At least 2 days of responding at less than 20% of the reinforced baseline was required before another test was conducted. Following all four tests, the animals were then returned to the methamphetamine self-administration baseline

2.6. Data Analysis

The principal dependent variables were the response rates during each of the food and drug components. The response rate during each component was calculated as the total responses during the component divided by the component time exclusive of timeouts. As responding during the second food component was affected by the amount of methamphetamine taken during the drug component, response rates in the second food component were not included in the analysis. Data were analyzed using the Proc Mixed (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) ANOVA procedure, which is capable of analyzing data sets for which some subjects were not tested under all conditions. Appropriate follow-up tests for individual effects were preformed using the Tukey-Kramer or Dunnett (for comparisons only to a control) tests. Separate analyses were performed for the results for food and methamphetamine. For the reinstatement studies, only the first 30 min of the drug component were used in the rate calculation. The results of the reinstatement tests were not normally distributed, but the distributions showed similar shapes across conditions; therefore, these results were analyzed using non-parametric procedures (Friedman test followed by paired comparisons using the Dunn procedure).

2.7. Drugs

Methamphetamine HCl (Sigma Chemical, St. Louis, MO) for self-administration was dissolved in sterile saline in a stock concentration of 50 mg/ml. Solutions (in 500 or 1000 ml sterile saline bags) were prepared from this stock solution for each monkey based on the animal’s weight. Care was taken to maintain the sterility of the solution. Depending on overall intake, a solution bag could last 1 to 2 weeks. Doses are for the salt. AM 251 (1-(2,4-Dichlorophenyl)-5-(4-iodophenyl)-4-methyl-N-1-piperidinyl-1H-pyrazole-3-carboxamide, purity >99%, synthesized by KV) and rimonabant (Research Triangle, NIH) were dissolved in vehicle containing 1% ethanol and 1% Tween 80 and saline and refrigerated until just prior to use. Doses for both AM 251 and rimonabant are for the base.

3. Results

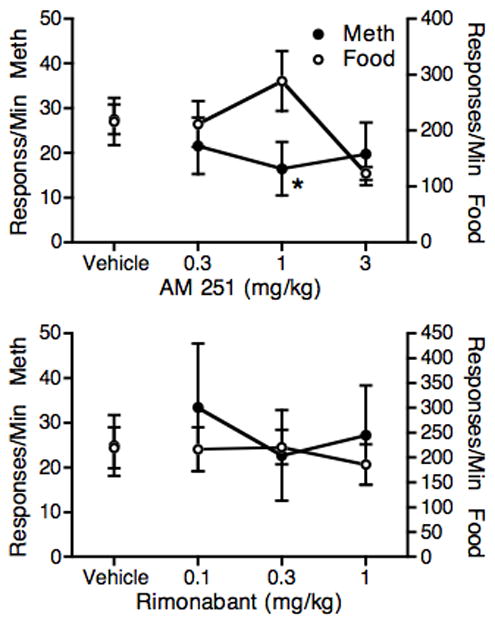

Figure 1 shows the effects of pretreatments with a range of doses of AM 251 and rimonabant. Effects are shown for response rates in the first food component and in the self-administration component where responding was reinforced by 3 μg/kg/injection of methamphetamine. The top panel shows the effects of AM 251. A slight decrease in methamphetamine self-administration was observed with all three doses of AM251, with the largest decrease occurring at 1 mg/kg. During the food component AM 251 slightly increased responding at 1 mg/kg and decreased responding at 3 mg/kg. The effect of AM 251 treatment on methamphetamine self-administration approached significance (F3,9 = 3.77, P < 0.053); planned comparisons to saline showed that only the effect of 1 mg/kg AM 251 was significant (p < 0.05, Dunnett test). For food responding in the first component, the treatment effect was significant (F2,8 = 4.30, P < 0.05); when compared to saline only the effect of 3 mg/kg AM 251 approached significance (P = 0.059, Dunnett). To compare the effects of food and methamphetamine, response rates were converted to percent of control values with the results of vehicle pretreatment as the control (data not shown). ANOVA showed a significant pre-treatment Dose X Reinforcer interaction (F2,6 = 8.39, P < 0.05). Planned comparisons between the reinforcers at each dose showed only the effects at 1 mg/kg approached significance (P = 0.059, Tukey).

Fig. 1.

Effects of AM 251 (top panel) and rimonabant (bottom panel) on self-administration of 3 μg/kg/injection methamphetamine (closed circles) and on FR responding for food (open circles). The 5-min food component was presented 30 min following drug treatment and the 90-min self-administration component was presented 40 min following drug treatment. Each point represents the mean of 4 monkeys. *P < 0.05 from saline control.

The bottom panel of Figure 1 shows the effects of rimonabant on monkeys responding for food and 3 μg/kg/injection methamphetamine. Rimonabant did not significantly affect response rates in either the drug or food components at the doses tested. A combined analysis of food and methamphetamine responding based on percent of control also showed no significant effects of the rimonabant.

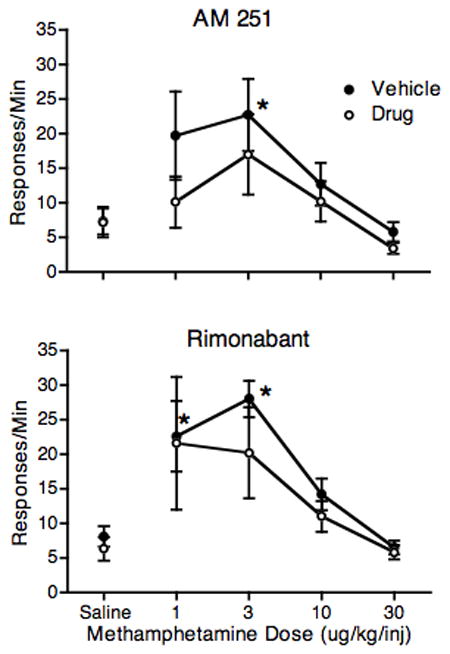

Results presented in Figure 1 showed that the 1.0 mg/kg AM 251 dose was the most likely dose to produce a specific effect on methamphetamine self-administration. Therefore 1.0 mg/kg AM 251 was used as a pretreatment for determination of the methamphetamine dose-effect function. The top panel of Figure 2 shows these results on responding during the methamphetamine self-administration component. When monkeys were pretreated with vehicle, a typical inverted U-shaped dose-effect function was observed, with peak responding occurring at 3 μg/kg/injection. When monkeys were pretreated with 1.0 mg/kg AM 251, the methamphetamine dose-effect function was shifted downward. ANOVA revealed a significant effect of methamphetamine Dose (F4,16 = 4.32, P < 0.05) and a significant effect of the AM 251 Pretreatment (F1,4 = 8.05, P < 0.5). The Dose X Pretreatment effect was not significant. In planned comparisons to the Vehicle-Saline control condition, responding for 3 μg/kg/injection methamphetamine differed significantly from control (P < 0.01, Dunnett Test) after vehicle treatment, but not after AM 251 treatment.

Fig. 2.

Effects of vehicle (closed circles) and drug (open circles) pretreatment on the methamphetamine self-administration dose-effect function. AM 251 was given at a dose of 1 mg/kg and rimonabant was given at a dose of 0.3 mg/kg. Both drugs were administered 40 min prior to the 90-min self-administration component. Each point represents the mean of 5 animals. *P < 0.05 from vehicle-saline control.

Since the results shown in Figure 1 did not point to an obvious treatment dose for rimonabant, a dose was chosen based on previous work in our laboratory in squirrel monkeys. Since a dose of 0.3 mg/kg rimonabant is sufficient to block THC self-administration (Justinova et al., 2008), the 0.3 mg/kg dose of rimonabant was chosen for study. While a significant effect of methamphetamine Dose (F4,16 > 6.9, P < 0.01) was observed, neither the effect of rimonabant Pretreatment nor the rimonabant Pretreatment X Dose interaction were significant. Planned comparisons to the Vehicle-Saline control group revealed that responding for both 1 and 3 μg/kg/injection of methamphetamine was significant (P < 0.05, Dunnett) after vehicle treatment, but not after rimonabant treatment.

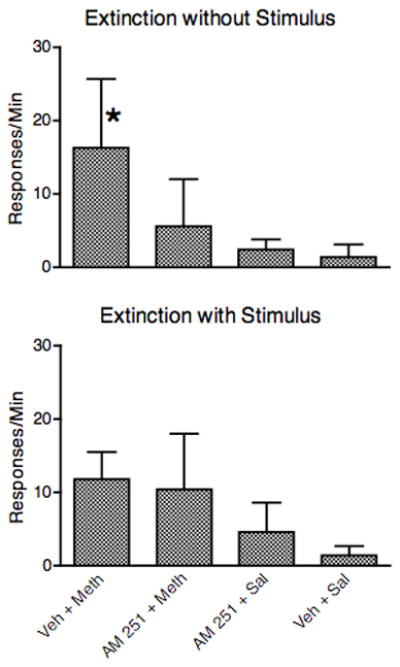

Since a significant pretreatment effect was only observed for AM 251 during testing on the methamphetamine self-administration baseline, only AM 251 was tested with the reinstatement procedure. Most monkeys rapidly decreased responding when switched to saline self-administration. The first test was performed 10.2 ± 2.3 days (mean ± s.e.m.) following the start of extinction in the Extinction Without Stimulus condition and 11.5 ± 2.3 days following the start of extinction in the Extinction With Stimulus condition. As shown in the top panel of Fig, 3, following extinction without the stimulus, a priming injection of methamphetamine led to increases in responding. AM 251 blocked this reinstatement of responding when given prior to the priming injection of methamphetamine (0.1 mg/k i.m.). A Friedman test on the data in the top panel of Fig, 3 revealed a significant effect of test condition (Friedman = 9.3, P < 0.05), and follow-up Dunn’s comparisons revealed that only the Veh + Meth test was different from the Veh + Sal test. Following extinction with the stimulus (data in the bottom panel of Fig. 3), although responding was increased somewhat when a priming injection of methamphetamine was given, this increase did not reach significance (Friedman = 6.9, P < 0.07); there was no indication that this priming effect of methamphetamine was reduced by AM 251.

Fig. 3.

Effects of 1 mg/kg AM 251 on reinstatement by 0.1 mg/kg methamphetamine of extinguished methamphetamine self-administration. In the top panel, extinction occurred in the absence of the stimulus associated with the self-administration injection (n = 6). In the bottom panel, extinction occurred while continuing to present the stimulus associated with the self-administration injection (n = 4). *P < 0.05 from the vehicle + saline condition.

4. Discussion

A number of investigators have suggested that cannabinoid receptor antagonists might be useful in the treatment of psychostimulant abuse. In particular, work with rodents has shown that pretreatment with cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists can block some of the behavioral effects of both cocaine and methamphetamine. In the current study, two cannabinoid receptor antagonists were tested in rhesus monkeys self-administering methamphetamine. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist AM 251, in particular, showed some utility in blocking the abuse-related behavioral effects of methamphetamine. AM 251 reduced methamphetamine self-administration at a dose that did not reduce food-reinforced behavior, and it shifted the methamphetamine dose-effect function downward. Further, AM 251 blocked the reinstatement of extinguished methamphetamine self-administration that occurred when a priming injection of methamphetamine was combined with the reintroduction of drug-related cues that were not present during extinction. These results suggest that AM 251 could be useful in the treatment of methamphetamine abuse.

There was also evidence that the cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant could be useful in treating methamphetamine abuse, although this evidence was less clear than with AM 251. During the determination of the methamphetamine dose-effect function, the two methamphetamine doses that maintained significantly more responding than saline did not do so when rimonabant was given as a pretreatment. However, as none of the vehicle versus rimonabant comparisons at any dose differed, these results are not as convincing as those of AM 251, where a significant main effect of pretreatment was observed. Nevertheless, these results do support the continued investigation of rimonabant as a potential treatment.

It is not clear why AM 251 and rimonabant should differ in their effects on methamphetamine self-administration. However, this finding is consistent with a recent study of cocaine self-administration. Xi et al. (2008) report that AM 251 attenuated cocaine self-administration maintained under a progressive ratio schedule, while rimonabant tested over a similar dose range did not. In addition, Xi et al. (2008) reported that AM 251 attenuated the effects of cocaine on brain-stimulation reward at doses that did not by themselves alter brain-stimulation reward. Rimonabant also attenuated the effects of cocaine in that study, but only at does that alone inhibited brain-stimulation reward, suggesting that rimonabant may have aversive properties. Xi et al. concluded that these differences were related to rimonabant not being as specific or potent for cannabinoid CB1 receptors as AM 251. Lan et al. (1999) reported that AM251 is twice as selective as rimonabant for cannabinoid CB1 compared to CB2 receptors and was also more potent at CB1 receptors (Ki of 7.49 vs 11.5 for rimonabant). Further, Pertwee (2005) reports that rimonabant has a number of effects in vitro that are independent of an action at cannabinoid CB1 receptors. Whether AM251 would have similar effects is not clear. Given the differences in potency, it is possible that a dose of rimonabant higher than the doses tested would have produced more AM251-like effects in the present study. However, at higher doses rimonabant can also produce non-specific side effects in vivo such as grooming, intense scratching, etc. (Beardsley et al., 2009). Similar effects are also seen with high doses of AM 251 (Tallett et al., 2007).

During all reinstatement testing, a non-contingent injection of methamphetamine was given before an operant session where responses produced the cues that were present in training, but not the methamphetamine reinforcement. However, two different extinction procedures were used to decrease methamphetamine seeking prior to this testing When the responding produced the methamphetamine-associated cues during extinction, priming with injections of methamphetamine failed to produce a robust reinstatement effect. With this extinction procedure, not only is the response no longer reinforced with methamphetamine, but the cues are also not followed by methamphetamine and are thus subject to extinction of the stimulus-reinforcer association. The fact that this procedure did not lead to robust reinstatement indicates that cues played a major role in maintenance of methamphetamine self-administration under baseline conditions, and that experiencing the cues during extinction made them less effective when combined with methamphetamine priming during the reinstatement test (O’Brien et al., 1988). Most previous studies of reinstatement in primates (Khroyan et al., 2000; Justinova et al., 2008) and rodents (Anggadiredja et al. 2004; DeVries et al. 2001; Xi et al. 2006) have omitted the cues during extinction.

When responding did not produce the cues during extinction in the present study, significant reinstatement was induced by a combination of a priming injection of methamphetamine and the reintroduction of methamphetamine-associated cues. AM 251 successfully blocked this reinstatement, suggesting that cannabinoid receptor antagonists might be most effective against the conditioned effects of methamphetamine. This result is consistent with most previous results in rodents for psychostimulant-induced reinstatement (Anggadiredja et al. 2004; DeVries et al. 2001; Xi et al. 2006). In contrast, Boctor et al. (2007) failed to observe antagonism of methamphetamine-induced reinstatement by the cannabinoid antagonist AM251 in rats. In the Boctor et al. study, however, there were apparently no stimulus changes associated with the methamphetamine reinforcement during training. This suggests that the presentation of drug-associated cues in training is a critical factor in observing antagonism of reinstatement by cannabinoid receptor antagonists. While the presentation of cues in training may be critical, in the current study we did not specifically study cue-induced reinstatement independent of drug-induced reinstatement. Therefore these results cannot specifically address the ability of cannabinoid receptor antagonists to alter cue-induced reinstatement. Although it is widely accepted as the best-available animal model of relapse to drug use in humans, it should be noted that the utility of the reinstatement procedure has not been completely validated (Katz and Higgins, 2003). Nevertheless, the present results strongly support the testing of cannabinoid receptor antagonists as treatments for relapse,

In conclusion, in rhesus monkeys self-administering methamphetamine, the cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist AM 251 significantly shifted the methamphetamine dose-effect function and also blocked the reinstatement of self-administration in monkeys that had undergone extinction in the absence of the drug-paired stimulus. In contrast, the cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist rimonabant failed to significantly alter methamphetamine self-administration. Since AM 251 can reduce both methamphetamine self-administration and the reinstatement of methamphetamine self-administration in this animal model, AM 251 might be effective as a treatment for methamphetamine abuse in humans.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, NIDA.

References

- Anggadiredja K, Nakamichi M, Hiranita T, Tanaka H, Shoyama Y, Watanabe S, Yamamoto T. Endocannabinoid system modulates relapse to methamphetamine seeking: possible mediation by the arachidonic acid cascade. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1470–1478. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beardsley PM, Thomas BF, McMahon LR. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists as potential pharmacotherapies for drug abuse disorders. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2009;21:134–142. doi: 10.1080/09540260902782786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boctor SY, Martinez JL, Jr, Koek W, France CP. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 does not modify methamphetamine reinstatement of responding. Eur J Pharmacol. 2007;571:39–43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries TJ, Schoffelmeer AN. Cannabinoid CB1 receptors control conditioned drug seeking. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2005;26:420–426. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vries TJ, Shaham Y, Homberg JR, Crombag HS, Schuurman K, Dieben J, Vanderschuren LJ, Schoffelmeer AN. A cannabinoid mechanism in relapse to cocaine seeking. Nat Med. 2001;7:1151–1154. doi: 10.1038/nm1001-1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattore L, Fadda P, Fratta W. Endocannabinoid regulation of relapse mechanisms. Pharmacol Res. 2007;56:418–427. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filip M, Gołda A, Zaniewska M, McCreary AC, Nowak E, Kolasiewicz W, Przegaliński E. Involvement of cannabinoid CB1 receptors in drug addiction: effects of rimonabant on behavioral responses induced by cocaine. Pharmacol Rep. 2006;58:806–819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justinova Z, Munzar P, Panlilio L, Yasar S, Redhi GH, Tanda G, Goldberg SR. Blockade of THC-seeking behavior and relapse in monkeys by the cannabinoid CB(1)-receptor antagonist rimonabant. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:2870–2877. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justinova Z, Solinas M, Tanda G, Redhi G, Goldberg S. The endogenous cannabinoid anandamide and its synthetic analog R(+)-methanandamide are intravenously self-administered by squirrel monkeys. J Neurosci. 2005;25:5645–5650. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0951-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Justinova Z, Tanda G, Redhi G, Goldberg S. Self-administration of delta9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) by drug naive squirrel monkeys. Psychopharmacology. 2003;169:135–140. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1484-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz JL, Higgins ST. The validity of the reinstatement model of craving and relapse to drug use. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168:21–30. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1441-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khroyan TV, Barrett-Larimore RL, Rowlett JK, Spealman RD. Dopamine D1- and D2-like receptor mechanisms in relapse to cocaine-seeking behavior: effects of selective antagonists and agonists. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2000;294:680–687. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lan R, Liu Q, Fan P, Lin S, Fernando SR, McCallion D, Pertwee R, Makriyannis A. Structure-activity relationships of pyrazole derivatives as cannabinoid receptor antagonists. J Med Chem. 1999;42:769–776. doi: 10.1021/jm980363y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Foll B, Goldberg S. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists as promising new medications for drug dependence. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2005;312:875–883. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.077974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesscher HM, Hoogveld E, Burbach JP, van Ree JM, Gerrits MA. Endogenous cannabinoids are not involved in cocaine reinforcement and development of cocaine-induced behavioural sensitization. Eur Neuropsychopharmacology. 2005;15:31–37. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2004.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen MV, Peacock L, Werge T, Andersen MB. Effects of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor agonist CP55,940 and antagonist SR141716A on d-amphetamine-induced behaviours in Cebus monkeys. J Psychopharmacology. 2006;20:622–628. doi: 10.1177/0269881106063816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meschler JP, Howlett AC. Signal transduction interactions between CB1 cannabinoid and dopamine receptors in the rat and monkey striatum. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:918–926. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00012-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien CP, Childress AR, Arndt IO, McLellan AT, Woody GE, Maany I. Pharmacological and behavioral treatments of cocaine dependence: controlled studies. J Clin Psychia. 1988;49(Suppl):17–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ong WY, Mackie K. A light and electron microscopic study of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor in primate brain. Neuroscience. 1999;92:1177–1191. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00025-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pertwee RG. Inverse agonism and neutral antagonism at cannabinoid CB1 receptors. Life Sci. 2005;76:1307–1324. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2004.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solinas M, Yasar S, Goldberg S. Endocannabinoid system involvement in brain reward processes related to drug abuse. Pharmacol Res. 2007;56:393–405. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tallett AJ, Blundell JE, Rodgers JR. Acute anorectic response to cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist/inverse agonist AM251 in rats: indirect behavioural mediation. Behav Pharmacol. 2007;18:591–600. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e3282eff0a9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G. Modulation of the endocannabinoid system: therapeutic potential against cocaine dependence. Pharmacol Res. 2007;56:406–417. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.09.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanda G, Munzar P, Goldberg SR. Self-administration behavior is maintained by the psychoactive ingredient of marijuana in squirrel monkeys. Nat Neurosci. 2000;3:1073–1074. doi: 10.1038/80577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tzavara ET, Degroot A, Wade MR, Davis RJ, Nomikos GG. CB1 receptor knockout mice are hyporesponsive to the behavior-stimulating actions of d-amphetamine: role of mGlu5 receptors. Eur Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;19:196–204. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vinklerová J, Nováková J, Sulcová A. Inhibition of methamphetamine self-administration in rats by cannabinoid receptor antagonist AM 251. J Psychopharmacology. 2002;16:139–143. doi: 10.1177/026988110201600204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z, Gilbert J, Peng XQ, Pak A, Li X, Gardner E. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 inhibits cocaine-primed relapse in rats: role of glutamate in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurosci. 2006;26:8531–8536. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0726-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z, Spiller K, Pak A, Gilbert J, Dillon C, Li X, Peng XQ, Gardner E. Cannabinoid CB1 receptor antagonists attenuate cocaine’s rewarding effects: experiments with self-administration and brain-stimulation reward in rats. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:1735–1745. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]