Abstract

The objective of this study was to examine associations between specific dimensions of the multidimensional cumulative risk index (CRI) and asthma morbidity in urban, school-aged children from African American, Latino and Non-Latino White backgrounds. An additional goal of the study was to identify the proportion of families that qualify for high-risk status on each dimension of the CRI by ethnic group. A total of 264 children with asthma, ages 7–15 (40% female; 76% ethnic minority) and their primary caregivers completed interview-based questionnaires assessing cultural, contextual, and asthma-specific risks that can impact asthma morbidity. Higher levels of asthma-related risks were associated with more functional morbidity for all groups of children, despite ethnic group background. Contextual and cultural risk dimensions contributed to more morbidity for African-American and Latino children. Analyses by Latino ethnic subgroup revealed that contextual and cultural risks are significantly related to more functional morbidity for Puerto Rican children compared to Dominican children. Findings suggest which type of risks may more meaningfully contribute to variations in asthma morbidity for children from specific ethnic groups. These results can inform culturally sensitive clinical interventions for urban children with asthma whose health outcomes lag far behind their non-Latino White counterparts.

Keywords: Pediatric asthma, Cumulative risks, Ethnic minority, Urban

Childhood asthma affects over 8 million children in the U.S. and is the most prevalent childhood chronic illness (Centers for Disease Control [CDC], 2005). Managing asthma effectively can be challenging for many children and families. For families who have children with more severe asthma (e.g., persistent levels), there is a need to use preventative and as needed medication consistently and accurately, to avoid or control irritants and allergens from the environment, and to monitor asthma symptoms in an accurate manner (National Institutes of Health [NIH], 2002). For children from urban environments, achieving effective asthma control may remain even more challenging, given the higher prevalence of environmental triggers they may encounter (Kattan et al., 1997). While much work has been devoted to examining broad factors that contribute to asthma health disparities, such as poverty and ethnic minority status (e.g., McDaniel, Paxson, & Waldfogel, 2006; Pearlman et al., 2006), more research is needed to identify experiences related to ethnic minority background and urban residence that may be associated with asthma morbidity. The purpose of this paper was to examine several risk processes related to culture, context, and asthma status that may be more salient for urban families who have a child with asthma and are from Latino (specifically, Puerto Rican and Dominican), African-American, and non-Latino White backgrounds. Associations between these risks and asthma morbidity for each ethnic group was analyzed.

Asthma Morbidity and Urban Children: Examining Factors Related to Ethnic Subgroup

Asthma morbidity is clearly over-represented in ethnic minority, urban children (CDC, 2005). Asthma is more prevalent in children from African American and Puerto Rican backgrounds compared to non-Latino White children, and these rates remain even when controlling for socioeconomic status (SES; CDC, 2005). For example, in 2006, lifetime prevalence rates were 30% higher in African American and 80% higher in Puerto Rican children than non-Latino Whites. Puerto Ricans have higher rates of asthma than any other Latino subgroup, in addition to higher rates than African Americans and Non-Latino Whites. These data speak to the importance of taking into account differences in disparity rates by ethnic subgroup, which could be masked when considering Latinos as a homogeneous group.

Pediatric asthma studies have focused on a number of explanations for these disparities. Research has examined factors along the individual level (e.g., adherence to daily medications; Rand, 2002; asthma severity; Wamboldt et al., 2002), the environmental level (irritants/allergens, Kattan et al., 2005; perceptions of community violence, Wright et al., 2004), the familial/cultural level (medication beliefs, Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2008; family asthma management, McQuaid, Walders, Kopel, Fritz, & Klinnert, 2005), and the health care system (insurance status, Crain, Kercsmar, Weiss, Mitchell, & Lynn, 1998; access to and quality of care, Ortega et al., 2002). Findings have shed light on potential contributions to variations in asthma morbidity outcomes. Further work is needed that considers different ethnic groups’ and subgroups’ experiences related to context, culture, and illness, that may increase the risk for asthma morbidity (Canino et al., 2006).

Consistent evidence has shown that low-income children are less likely to take their daily controller medications, and are more likely to utilize the ER for their asthma care than their higher-income counterparts (e.g., Rand et al., 2000; Warman, Silver, & Stein, 2001). Studies that do include ethnic minority children tend to conceptualize ethnic minority status, SES, or urban residence as risk factors contributing to morbidity without describing the characteristics related to these backgrounds that may be relevant to asthma management behaviors. It has been argued that conceptual models that consider multiple factors may better represent the reality of the lives of urban families. Understanding asthma morbidity within a socio-cultural context should continue to be a priority of research including urban children with asthma, as there may be factors beyond poverty that contribute to disparities in asthma outcomes among pediatric populations (Koinis Mitchell et al., 2007).

As demonstrated by our previous research, there are important contextual (e.g., neighborhood stress) and cultural (e.g., discrimination) experiences that may challenge asthma control (Koinis Mitchell et al., 2007). The current study includes results from secondary analyses that examine associations between processes that fall under specific dimensions of risk (asthma-specific, culture, and context) and asthma morbidity in a group of urban families from African American, Latino and non-Latino White backgrounds. These risk factors are included in a cumulative risk index (CRI), which captures the quantity and quality (i.e., severity) of risk factors that may be faced by urban families who have a child with asthma (see Koinis Mitchell et al., 2007). Our previous research has shown that higher levels of cumulative risks related to urban living and asthma status explained more of the variation in asthma morbidity indices than poverty or asthma severity alone (Koinis Mitchell et al., 2007).

The current study builds on our previous work (Koinis Mitchell et al., 2007) by delineating associations between specific dimensions of risks and asthma morbidity for families from different cultural backgrounds. Knowledge gained from these efforts can assist in structuring educational and psychosocial-based interventions for urban youth with asthma from specific cultural groups. For this study, families’ discrimination experiences and levels of acculturative stress were the cultural risk variables of focus. Perceived discrimination can interact with aspects of the environment, such as family and community poverty, to threaten optimal health-related behaviors for children (Szalacha et al., 2003). Further, a relation between acculturation and poor health care utilization in adults based on ethnic background has been shown (Solis, Marks, Garcia, & Shelton, 1990). Poverty and the level of neighborhood stresses were the sociocontextual risk variables of focus. Urban areas with high levels of poverty, urban stressors (e.g., high crime rates), and a high concentration of ethnic minority families have increased rates of child asthma hospitalization and mortality (Cabana et al., 2004). Triggers within the home (e.g., exposure to environmental tobacco smoke) and school environment were the asthma-related risk variables of focus. Relations between more trigger exposure, more hospitalizations, and asthma severity in urban children have been found (Nelson et al., 1997).

The goals of this paper were twofold. First, we sought to examine the proportion of families in our sample that qualified for high-risk status on each risk process included in the CRI by ethnic group (Latino: Puerto Rican and Dominican, African-American, and non-Latino White). We also investigated associations among each risk dimension of the CRI and asthma morbidity, specifically, the degree of functional impairment that asthma imposes on children’s daily functioning (Rosier et al., 1994). Based on previous research, we expected that higher levels of contextual and asthma-related risks would be associated with more functional morbidity for all ethnic groups, and that cultural risks would be associated with more morbidity for Latino and African American groups. At present, there is insufficient evidence to support how such cultural risks may be related to asthma morbidity in children from different Latino ethnic subgroups. For this study, children from Puerto Rican and Dominican backgrounds were the specific Latino ethnic subgroups included in our sample, as data suggest that asthma prevalence rates are highest among children from these backgrounds compared to children from other Latino subgroups (CDC, 2005).

Method

Participants

Two hundred and sixty-four children between the ages of seven and thirteen (mean age: 10.8), and their primary caregivers were interviewed for this study. Families were from African American (25%), Latino (24% Puerto Rican, 29% Dominican), and non-Latino White (24%) backgrounds. Child participants were 40% female and 60% male. Demographic characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of participants

| Variable | % of sample | Mean | SD | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child characteristics | ||||

| Child’s age | 10.8 years | 2.5 years | 7–17 years | |

| Child’s gender | ||||

| Female | 40% | |||

| Male | 60% | |||

| Primary caregiver’s characteristics | ||||

| Primary caregiver’s ethnicitya | 25% AA; 51% Latino (24% Puerto Rican; 29% Dominican); 24% Anglo | |||

| Spanish language preference | 11% of the sample elected to hear the questions in Spanish | |||

| Marital status | 45% Married; 9% Separated; 14% Divorced; 1% Widowed; 31% Never married | |||

| Number of years of education | 13.04 years | 2.8 | 5–17 years | |

| Occupational status of PCG | 55% Not employed; 45% Not employed | |||

| Family characteristics | ||||

| Family’s annual incomeb | $32,382 | $500–$100,000 | ||

| # of people living in home | 4.4 | 1.5 | 2–10 | |

Primary caregivers were asked an open-ended question regarding the ethnic group with which they primarily identified themselves

Family’s total annual income from all sources. The median income level for this sample was $22.500. Eight Anglo families’ annual income was greater than or equal to 100,000. Eighty-seven participants’ incomes fell at or below the poverty threshold (CDC, 2005)

Design and Procedures

Data for the Latino and Non-Latino White children were collected as part of a larger study assessing factors that contribute to asthma health disparities between children from Non-Latino White and Latino backgrounds. Data for the African-American group were collected and added to the sample to form this sub- study by the first author. Data collection for both studies occurred in parallel, and all participating families received the same measures (however, families from the parent study received a more comprehensive set of assessments). The current study’s sample consisted of the same families involved in a previously published study on urban families of children who have asthma (Koinis Mitchell et al., 2007). Eligibility criteria consisted of the following: (1) volunteering primary caregiver (PCG) was the child’s legal guardian; (2) child was between the ages of 7 and 15 years old; (3) child had been diagnosed with asthma by a physician and was currently obtaining asthma treatment; (4) child had lived in the same household as the PCG for a minimum of six months, (5) child and PCG live in an urban environment in Providence (verified by zip code); and (6) PCG’s self-identified ethnicity was either non-Latino White, African-American or Latino (Puerto Rican or Dominican, specifically).

Data collection occurred at the Childhood Asthma Research Program, Rhode Island Hospital. Children with asthma and their primary caregivers participated in interview-based assessments. Visits included assessments of severity, which will be described in further detail below, a multi-dimensional risk assessment comprised of questionnaire measures, and asthma-related morbidity. A range of severity levels was represented (NIH, 2002; mild intermittent 11%; mild persistent 26%; moderate persistent 33%; severe persistent 30%). These percentages were skewed more towards persistent levels, which typifies severity levels found in urban settings. There were no significant differences on levels of asthma severity by ethnic group.

Approval for this study was obtained from the hospital’s Institutional Review Board. All families were recruited from either hospital-based primary care clinics, two primary care clinics in the community, and community events that occurred within urban neighborhoods. There were no differences on study variables for families who were recruited by each method. A screening questionnaire including the above eligibility criteria was administered to all caregivers who expressed an interest in participating.

Informed consent and child assent were obtained. All questionnaires were administered separately to each child and parent in interview format in the lab or the participants’ home. A release of information form that allowed a review of the medical record (which enabled us to obtain asthma severity level) was also administered. Families were paid for participation, and childcare and transportation to sessions were available to all participants. Interviews were offered in Spanish or English, depending on participants’ preference. All measures were translated from English to Spanish and then reviewed by a bilingual committee using a process to insure linguistic equivalency of measures in both languages (e.g., Canino & Bravo, 1994).

Measures

Table 2 presents the mean, standard deviation, range, and internal consistency for each measure.

Table 2.

Descriptive data for study variables

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Range in sample | Sample’s Cronbach’s alpha |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cumulative risk index: contextual dimension | |||

| Poverty (income to needs ratio) | .68 (4.1) | 0–1 | N/A |

| Neighborhood disadvantage | 8.0 (4.9) | 0–18 | .87 |

| Cultural dimension | |||

| Perceived discrimination | 33.8 (9.5) | 9–45 | .87 |

| Cultural stress | 12.9 (9.2) | 0–46 | .89 |

| Asthma specific | |||

| Asthma severity | 11% Mild intermittent; 26% Mild persistent; 33% Moderate persistent; 30% Severe persistent | ||

| ETS | N/A | 0–1 | N/A |

| Functional morbidity due to asthma | 1.7 (.84) | 0–3.80 | .72 |

Demographic Questionnaire

A demographic interview was administered to each parent to assess the following key sociodemographic variables: yearly income, number of family members in the home, primary caregiver’s employment status, marital status, education, and age, as well as the child’s age and gender. Primary caregiver’s report of ethnicity served as the index for the family.

Asthma Morbidity was assessed by parent report of functional limitation due to asthma. Parents completed the Asthma Functional Severity Scale (AFSS). This measure assessed the degree of functional impairment that asthma imposed on child’s daily functioning over the past four weeks and past year (Rosier et al., 1994). The scale includes four components of children’s asthma morbidity, including frequency of episodes, frequency of symptoms between episodes, intensity of impairment during an episode, and intensity of impairment during the intervals between episodes. The functional morbidity index score was computed by calculating the mean across all completed items for the past year. Higher scores indicated greater levels of impairment. This scale has been used to assess asthma morbidity in several studies including children with asthma (Koinis Mitchell et al., 2007; McQuaid et al., 2005).

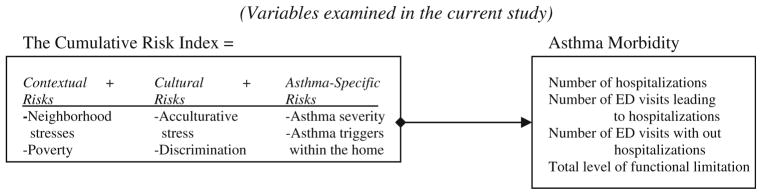

The Multi-Dimensional Cumulative Risk Index

Procedures employed in previous research (Barocas, Seifer, & Sameroff, 1985; Evans & English, 2002) were applied to the development of the Cumulative Risk Index and are described in the “Results” section (Fig. 1; Koinis Mitchell et al., 2007).

Fig. 1.

Multiple risk model of asthma morbidity in urban children

Contextual/Environmental Dimension

Poverty

Poverty was defined as living at or below the federally defined poverty line. In 2005, the federal poverty line for a family of 4 was $19,350. Using procedures by Duncan and Brooks-Gunn (1997) an income-to-needs ratio was developed, which is an annually adjusted, per capita index comparing household income to federal estimates of minimally required expenditures for food and shelter. Family income over the past year was calculated from caregiver report and included earnings of the mother, earnings of her resident husband or partner, and all other sources of household income, including public assistance. An income-to-needs ratio was computed by dividing the total yearly family income by the poverty threshold for that family size (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2005). Consistent with the U.S. government definition of poverty, a family was considered at or below the poverty line if the income-to-needs ratio was less than or equal to 1.0 during the year in which they took part in the study.

Neighborhood Disadvantage

Levels of neighborhood disadvantage associated with children’s neighborhood context were collected from the Neighborhood Unsafety Scale (Resnick et al., 1997), a seven-item measure of the parent’s perception of neighborhood disadvantage. Questions for this scale were modified from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health (Resnick et al., 1997). This scale has standardized Cronbach’s alphas of .76 for the English language interview and .71 for the Spanish language interview, and adequate psychometric data on this scale for use with urban, low-income children has been reported (Resnick et al., 1997). Representative questions include: “I feel safe being out alone in my neighborhood during the night” and “People often get mugged, robbed or attacked in my neighborhood”. Response categories for the 4- item Likert scale ranged from Not at all true (1) to Very true (4). Items were summed to form a total neighborhood disadvantage score with higher scores indicating more disadvantage. This scale has been used in previous studies including urban, low income children with asthma and adequate reliability has been reported (Koinis Mitchell et al., 2007).

Cultural Dimension

Perceived Discrimination

Experiences of perceived discrimination were collected through parent report of responses to nine items that assess daily experiences of discrimination that families have faced over the past year (Jackson & Williams, 1995). Response categories range from Almost Everyday (5) to Never (0). The minimum and maximum scores for the scale are 0 and 45, respectively. This measure has Cronbach’s alphas of .90 for the English language interview and .91 for the Spanish language interview and has been used consistently with different ethnic groups (e.g., African American and Latino families; Jackson & Williams, 1995). The measure was administered to the non-Latino White, African American, and Latino families. We administered this measure to the non-Latino White families to assess potential discriminatory experiences that all families face, regardless of ethnic group membership, in order to include these experiences as a potential risk factor in the CRI. Two representative scale items are: “You are treated with less courtesy than other people”, and “People act as if they think you are not smart.” This scale has been used in our previous research with low-income children who have asthma and demonstrated adequate psychometric properties (Canino et al., 2009).

Acculturative Stress

The Cultural Stress Scale was administered to African American and Hispanic participants to assess the level of stress that parents experience while acculturating to the United States (through migration experiences, language barriers, etc.) over the past year (Cervantes, Padilla, & Salgado de Snyder, 1990). This measure includes items that assess the extent to which families experience cultural stress, so it is also applicable to families who are from ethnic minority backgrounds but have not immigrated to the U.S. This instrument has been employed in studies with Mexican-American samples, and with island and mainland Puerto Ricans. It includes 26 items from the 73-item immigrant version of the Hispanic Stress Inventory, which were selected to evaluate different aspects of stress associated with acculturation: immigration stress, family/culture stress and occupational/economic stress using a Likert scale (Rarely or never (0), Sometimes (1), Often (2)). Scores can range from 0 to 52. Internal consistency was estimated separately for both the English and Spanish version of the scale; Cronbach’s alpha exceeded .78. for both versions (Canino et al., 2009; Cervantes et al., 1990).

Asthma-Specific Dimension

Children’s Asthma Severity

Asthma severity was classified according to national guidelines in place at the time the study was conducted. Specifically, standard criteria developed by NHLBI, such as parent report of asthma symptoms (over the past year) and children’s current medication regimen were collected to classify children’s asthma severity levels (NIH, 2002). Medication reports were cross-verified with the medical chart review. Based on the results of the chart review and parent’s self-report assessment, the asthma specialist quantified the child’s asthma severity as (1) mild intermittent, (2) mild persistent, (3) moderate persistent, or (4) severe persistent (NIH, 2002). For the non-Latino White and Latino families who participated in the larger study, the study clinicians also had access to children’s pulmonary function test results. Children with severe persistent asthma qualified for risk status on this variable.

Environmental Tobacco Smoke (ETS)

Parents were asked questions regarding the presence of environmental tobacco smoke in the home environment using questions from the Family Asthma Management System Scale (McQuaid et al., 2005) a semi-structured interview to assess families’ asthma knowledge and management practices. Households were considered to contain smokers if it was reported that either a parent, the child with asthma, any other household member, or any regular visitor used tobacco. Families qualified for risk status on this variable if they answer yes to any of the questions. Validity for the overall measure has been established (McQuaid et al., 2005).

Results

Data were complete on all asthma morbidity outcomes and potential risk factors included in the CRI. The means and standard deviations of the key predictor and outcome variables are presented in Table 2.

Relations Among Demographic Characteristics, Outcomes, Processes Qualifying as Risk Factors

Correlational analyses helped to determine significant associations among key demographic characteristics (e.g., child’s age, gender) and asthma morbidity in order to account for them in subsequent analyses. No significant associations emerged among demographic variables and morbidity. Several demographic characteristics were included as risk processes in the CRI and tested in later analyses (e.g., severity, poverty). We did not include ethnic group status or racial group membership as a demographic variable, as we analyzed whether the association between the CRI and morbidity differed by ethnic group and ethnic sub-group. Correlational analyses were then conducted between potential risk factors and asthma morbidity to determine whether each variable actually qualified as a risk factor by its association with asthma morbidity. As indicated in Table 3, each risk process was either significantly associated with morbidity, or showed a trend towards significance.

Table 3.

Correlations of potential risk processes and asthma morbidity outcomes

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Income-to-needs | – | .32** | .11 | .10 | .11 | .09 | .20** |

| 2. Neighborhood disadvantage | – | .31** | .20* | .10 | .10 | .30** | |

| 3. Perceived discrimination | – | .52** | .10 | .11 | .15t | ||

| 4. Cultural stress | – | .10 | .11 | .16t | |||

| 5. Asthma severity | – | .11 | .40** | ||||

| 6. ETS | – | .13t | |||||

| 7. Asthma functional limitation | – |

p ≤ .15

p < .05

p < .001

Construction and Analysis of the CRI

In order to address the hypotheses of this study, the development and total score derived from the Cumulative Risk Index was constructed.

When looking at whether a specific risk factor qualified as one for a given family, we employed statistical procedures used in previous studies to consider, for example, scores that fell in the top 25% of the sample as a “risk factor.” (see Koinis Mitchell et al., 2007). We provided each family with a dichotomous score of 0 or 1 on each risk factor. Families could qualify for 0–6 risks for each factor considered in CRI. For risk factors that were not continuous variables, such as poverty, families who are living at or below the poverty threshold were considered in the high-risk group and were assigned a score of 1. Then, a cumulative risk score was created to reflect the total number of high-risk groups of which any individual family was a member.

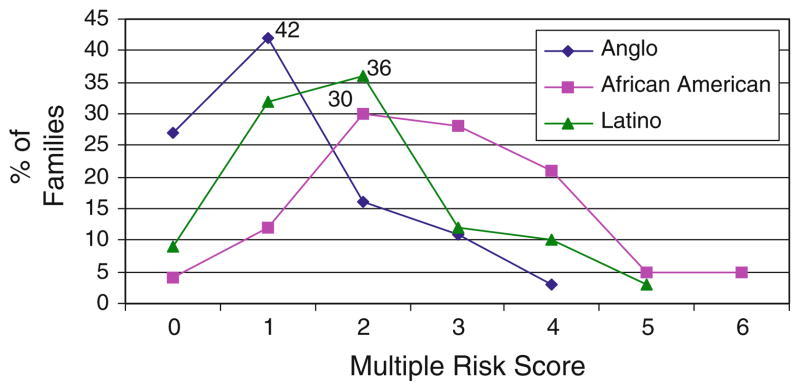

Percentage of Families Who Qualified for High-Risk Status on Number of Risks by Ethnic Group

We first wanted to examine the percentage of families who qualified for high-risk status on a specific number of risks included in the CRI. As depicted in Fig. 2, out of six risks on which families could qualify for high-risk status, non-Latino White families in this sample qualified for a range of 0–4 risks, and the highest percentage of families (42%) qualified for only one risk. African American families qualified for a range of 1–6 risks and the highest percentage of families (30%) appeared to qualify for a total of 2 risks (although 28% of families experienced 3 risks). Latino families qualified for a range of 0–5 risks and the highest percentage of families (36%) qualified for 2 risks. When analyzing these data by Latino ethnic subgroup, as illustrated in Fig. 3, the highest proportion of families from Puerto Rican backgrounds (47%) qualified for 2 risks, while the highest proportion of Dominican families (41%) qualified for 1 risk.

Fig. 2.

Percentage of families by ethnic group who qualified for high risk status on a specific number of risks

Fig. 3.

Percentage of families by ethnic group who qualified for high risk status on a specific number of risks

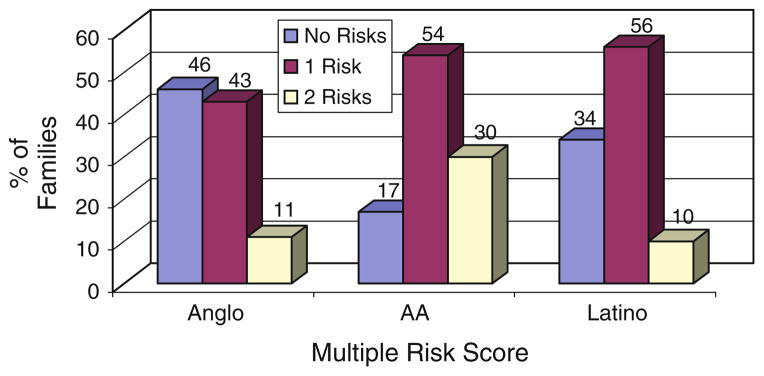

Percentage of Families Who Qualified for Risk Status for Each Dimension of the CRI by Ethnic Group

We also were interested in graphically displaying the proportion of families who qualified for risk status on each dimension of the CRI by ethnic group, which would allow us to examine more closely whether specific risk dimensions were particularly salient for certain groups of families. As indicated in Fig. 4, on the asthma risk dimension, which included families qualifying for moderate or severe levels of asthma severity and/or exposure to ETS, 46% of non-Latino White families qualified for no risks, while 43% qualified for one risk. Fifty-four percent of the African American sample qualified for one risk and 30% of the Latino sample qualified for two risks. Fifty-six percent of the Latino sample qualified for one risk and 34% experienced no risks.

Fig. 4.

Percentage of families by ethnic group who qualified for high risk status on the asthma-related risk dimension

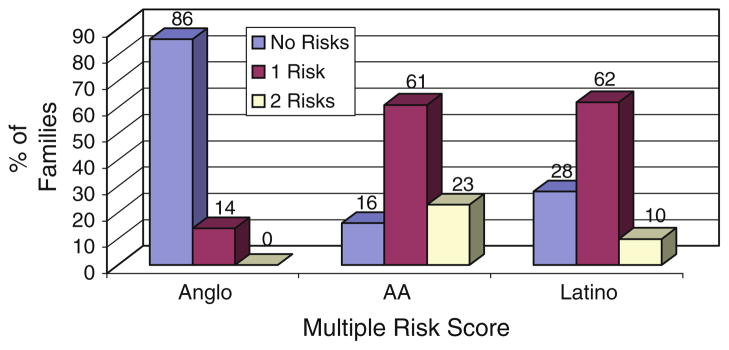

In terms of the contextual risk dimension (Fig. 5), which included poverty status and high levels of neighborhood stress, 63% of the non-Latino White sample qualified for no risks and 36% for one risk. Forty-one percent of the African American sample qualified for one risk and 51% qualified for no risks, and 61% of the Latino sample qualified for one risk, while 28% of the Latino families qualified for no risks. With regard to the cultural risk dimension (Fig. 6), which included perceptions of acculturative stress and discrimination, 63% of the non-Latino White sample did not qualify for high risk status on any risk factors, 92% of the African American sample either qualified for one or two risks, and 72% of the Latino sample either qualified for one or two risks.

Fig. 5.

Percentage of families by ethnic group who qualified for high risk status on the contextual dimension

Fig. 6.

Percentage of families by ethnic group who qualified for high risk status on the cultural dimension

Functional Morbidity and Poverty Scores: Differences by Ethnic Group?

We then were interested in examining whether the functional morbidity and poverty risk scores significantly differed by ethnic group. As illustrated in Table 4, African American children’s average morbidity score was significantly higher then the non-Latino White children’s score in our sample. Latino children’s asthma morbidity score did not differ significantly from the non-Latino White group, but when Latino ethnic subgroups’ scores were examined separately, Puerto Rican children scored significantly higher then the non-Latino White children in the sample. In terms of level of poverty, all ethnic minority groups’ poverty scores were significantly higher than the group of non-Latino White children of this sample. Although all families were recruited from an urban area, this is fairly representative of the SES makeup of the greater Providence area. Using the Bonferroni method to control for Type I error, the p-value of each comparison conducted above was corrected by dividing the p-level of .05 by the number of comparisons (e.g., 3), which yields a p-value of .02 (α = .05/3 = .02). Differences in the morbidity levels and poverty scores remained significant based on this criterion.

Table 4.

Functional morbidity and poverty scores by ethnic group

| Ethnic group | Functional morbidity

|

Level of poverty

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| X | SD | Range | t statistic | X | SD | Range | t statistic | |

| Anglo | 1.44 | (.75) | 0–3.3 | .65 | (.57) | .16–2.7 | ||

| African American | 2.22 | (.77) | 0–3.8 | ** | 2.35 | (4.26) | .22–14 | * |

| Latino | 1.65 | (.83) | 0–3.3 | 1.71 | (3.5) | .28–12 | * | |

| Puerto Rican | 1.79 | (.83) | 0–3.3 | * | 1.43 | (1.23) | .28–6.7 | * |

| Dominican | 1.51 | (.81) | 0–3.1 | 1.95 | (3.70) | .28–12 | * | |

p < .05

p < .001

Associations Between CRI Risk Dimensions and Morbidity by Ethnic Group

Regression analyses were then conducted to assess the association between each dimension of the CRI and morbidity by ethnic group. This analysis allowed us to determine the relative contribution of each dimension of risk (asthma-related, contextual, and cultural) on morbidity for specific groups of children. As indicated in Table 5, for the non-Latino White group, results suggest that the asthma-related risk dimension of the CRI seem to account for the most variation (17%) in functional limitation due to asthma. For the African American group, asthma-related, contextual, and cultural risks contributed significantly to morbidity, with contextual risks (10%) and cultural risks (12%) accounting for higher proportions of the variance in functional limitation. For the Latino group, both asthma (13%) and contextual risks (7%) accounted for significant portions of the variance, with the cultural risk dimension (8%) showing a trend towards significance in its association with morbidity. When we examine the regression models by Latino ethnic subgroup, for Puerto Rican children, each of the asthma (12%), contextual (8%), and cultural dimension of risks (7%) was significantly related to more morbidity, while only the asthma related risk dimension was associated with morbidity for Dominican children.

Table 5.

Associations between CRI dimensions and asthma functional limitation by ethnic group

| B | R2 | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anglo | |||

| Asthma risks | .41 | .17 | .04 |

| Context | .34 | .06 | .06 |

| Cultural | .40 | .01 | ns |

| African American | |||

| Asthma risks | .20 | .09 | .05 |

| Context | .29 | .10 | .03 |

| Cultural | .38 | .12 | .01 |

| Latino | |||

| Asthma risks | .50 | .13 | .001 |

| Context | .27 | .07 | .03 |

| Cultural | .25 | .08 | .07 |

| Puerto Rican | |||

| Asthma risks | .46 | .12 | .05 |

| Context | .27 | .08 | .05 |

| Cultural | .25 | .07 | .05 |

| Dominican | |||

| Asthma risks | .51 | .14 | .05 |

| Context | .19 | .04 | .12 |

| Cultural | .24 | .05 | .12 |

Discussion

Summary of Findings and Implications

Consistent with our hypotheses, results from this study showed that higher levels of asthma-related risks were associated with more functional morbidity for all groups of children, regardless of ethnic group background. As indicated in previous research, more severe levels of asthma (Wamboldt et al., 2002) and exposure to ETS (Kattan et al., 1997) have consistently been shown to increase the risk for asthma morbidity in children.

The contextual and cultural specific risks focused on in this study made more of a contribution to morbidity for African American and Latino children. Additional results from this research indicated that a higher proportion of the African American and Latino families, compared to the non-Latino White families of the sample, qualified for high-risk status on one or more risks from the Contextual and Cultural Risk dimensions of the CRI. Analyses by Latino ethnic subgroup revealed that the Puerto Rican children in our sample had higher functional limitation scores, and seemed to be affected by all three dimensions of risks included in the CRI, in comparison to the Dominican children of the sample, whose functional limitation scores were associated with the asthma-related risk dimension only. Further, African American and Latino families experienced higher levels of poverty and functional limitation due to asthma when compared to their non-Latino White counterparts. Despite these differences, there were no differences in level of severity by ethnic group. These findings suggest that processes related to poverty or cultural experiences may compromise asthma management for children.

When attempting to offer strategies to support asthma control, taking into consideration the nature and type of stresses families face is critical, as acculturation or discrimination experiences may challenge asthma management and treatment. For example, interventions that specifically address families’ context, such as their level of economic resources in relation to the number of family members residing in the home, and/or their neighborhood safety, may provide more information on why families find aspects of the asthma management process difficult (e.g., activity restriction may be more limited simply due to the fact that the family’s neighborhood may be unsafe). Further, beliefs about asthma medications and use of alternative approaches to asthma care (e.g., home remedies, Koinis-Mitchell et al., 2008), level of acculturation, migration experiences, and potential feelings of discrimination when navigating the health care system may be critical to consider for African American and Latino families (Institute of Medicine, 2002). Such experiences may be important to understand when discussing children’s medication adherence patterns, or why families may be missing their children’s asthma well-visit appointments.

Overall, findings suggest which type of risks may contribute to variations in asthma health outcomes for children from specific ethnic groups. All three groups appear to have been affected by contextual and asthma-related risks, although their relative contribution to asthma functional limitation seems to differ. Findings also suggest which type of risks may contribute more meaningfully to variations in asthma health outcomes for children from specific ethnic groups. It appears that cultural risk factors have an important bearing on asthma morbidity for Latino and African American children. Risk models that are multidimensional in nature may be more representative of the social realities of urban families’ lives. It is crucial that future work considers how cultural and contextual stresses, such as those examined in the CRI model, contribute to the experience of managing asthma in an urban environment.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

There are several limitations of this research that warrant consideration. As mentioned in our previous work, the CRI addressed only a limited number of risks in each dimension and a limited number of risk domains. Future research efforts should test other potential dimensions of risk factors with larger samples of ethnically diverse children, such as health care system variables that may affect morbidity (e.g., cultural competence of providers, access to routine medical care; Lieu et al., 2004; barriers to filling prescriptions for daily asthma medications; McQuaid et al., 2009). Additional cultural and contextual risks likely faced by ethnic minority and poor families should be considered (e.g., clashes of health beliefs between families and health care system). Analyses did not permit us to examine bi-directional associations between dimensions of risks and morbidity. Future work should include larger samples of urban children with asthma, in order to test pathways of influence between salient risks and morbidity for specific ethnic groups. As mentioned above, African American and Latino families faced higher levels of poverty than the non-Latino White families in our sample. Despite the fact that all families resided in urban settings, we did not exclude families from the study based on income level. We believe our recruitment techniques and eligibility criteria did permit us to include a representative sample of families from each ethnic background who resided in the Greater Providence, urban area. Further, we recognize that study clinicians had additional information (e.g., pulmonary function test results) for classifying the severity level of children from Latino and non-Latino White backgrounds. Although this assessment was not included in the sub-study with African American families, the same study clinicians determined severity through other similar assessments (e.g., medical chart review, self-report measurements). The asthma severity levels of children from the groups depicted by each method did not differ. Finally, our assessment of severity relied upon medication use and symptom frequency and was based on the 2002 NHLBI asthma guidelines that were available at the time this study was implemented. It should be noted that in 2007, new guidelines were generated and emphasized two primary differences to the previous classification; a consideration of control (the degree to which the manifestations of asthma are met by therapeutic intervention) and the distinction (within severity or control) between domains of current impairment and future risk. In addition, the category “mild intermittent” was also changed to “intermittent” in recognition of cases where exacerbations are few and far between, but are significant when they do occur.

As reported in our previous work (Koinis Mitchell et al., 2007), studies employing cumulative risk models with inner city children are useful in that they (1) account for the multiple underlying mechanisms that may assist in explaining the asthma health disparity and (2) identify processes that can guide the development of culturally-tailored asthma interventions for urban families from specific ethnic groups. As mentioned above, future work should analyze how the actual experience of specific risks for families, along with the number and type of risk, may complicate specific aspects of the asthma management process (e.g., medication adherence, trigger control, symptom monitoring). The experiences of such risks may be different for families, depending upon their cultural values, their threshold for tolerating risks, as well as individual, familial, and community resources available. Asthma interventions that are designed to be specific in nature based on the risks that families are more likely to face, may be more beneficial in supporting families’ needs and concerns regarding the asthma management process.

Acknowledgments

Funds for this study were provided by Grants # U01-Hl072438-01 (G. Fritz and G. Canino, P.I.s) and # F32 HL74570 (D. Koinis Mitchell, P.I.) from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute.

Contributor Information

Daphne Koinis-Mitchell, Email: Daphne_Koinis-Mitchell@Brown.edu, Child and Family Psychiatry, Bradley/Hasbro Research Center, Brown Medical School, 1 Hoppin Street, Coro West, 2nd Floor, Providence, RI 02903, USA.

Elizabeth L. McQuaid, Child and Family Psychiatry, Bradley/Hasbro Research Center, Brown Medical School, 1 Hoppin Street, Coro West, 2nd Floor, Providence, RI 02903, USA

Sheryl J. Kopel, Child and Family Psychiatry, Bradley/Hasbro Research Center, Brown Medical School, 1 Hoppin Street, Coro West, 2nd Floor, Providence, RI 02903, USA

Cynthia A. Esteban, Child and Family Psychiatry, Bradley/Hasbro Research Center, Brown Medical School, 1 Hoppin Street, Coro West, 2nd Floor, Providence, RI 02903, USA

Alexander N. Ortega, UCLA School of Public Health, Los Angeles, CA, USA

Ronald Seifer, Child and Family Psychiatry, Bradley/Hasbro Research Center, Brown Medical School, 1 Hoppin Street, Coro West, 2nd Floor, Providence, RI 02903, USA.

Cynthia Garcia-Coll, Child and Family Psychiatry, Bradley/Hasbro Research Center, Brown Medical School, 1 Hoppin Street, Coro West, 2nd Floor, Providence, RI 02903, USA.

Robert Klein, Child and Family Psychiatry, Bradley/Hasbro Research Center, Brown Medical School, 1 Hoppin Street, Coro West, 2nd Floor, Providence, RI 02903, USA.

Elizabeth Cespedes, Child and Family Psychiatry, Bradley/Hasbro Research Center, Brown Medical School, 1 Hoppin Street, Coro West, 2nd Floor, Providence, RI 02903, USA.

Glorisa Canino, University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras, Puerto Rico.

Gregory K. Fritz, Child and Family Psychiatry, Bradley/Hasbro Research Center, Brown Medical School, 1 Hoppin Street, Coro West, 2nd Floor, Providence, RI 02903, USA

References

- Barocas R, Seifer R, Sameroff AJ. Defining environmental risk: Multiple dimensions of pscyhological vulnerability. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1985;13:433–447. doi: 10.1007/BF00911218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cabana MD, Slish KK, Lewish TC, Brown RW, Nan B, Lin X, et al. Parental management of asthma triggers within a child’s environment. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2004;114:352–357. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.04.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Bravo M. The adaptation and testing of diagnostic and outcome measures for cross-cultural research. International Review of Psychiatry. 1994;6:281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, Koinis Mitchell D, Ortega A, McQuaid E, Fritz G, Alegria M. Asthma disparities in the prevalence, morbidity and treatment of Latino children. Social Science and Medicine. 2006;63:2926–2937. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canino G, McQuaid EL, Alvarez M, Colon A, Esteban C, Febo V, et al. Issues and methods in disparities research: The Rhode Island-Puerto Rico asthma center. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2009;44:899–908. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control. Asthma—United States, 2003. Centers for Disease Control; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cervantes RC, Padilla AM, Salgado de Snyder N. Reliability and validity of the Hispanic Stress Inventory. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 1990;12:76–82. [Google Scholar]

- Crain EF, Kercsmar C, Weiss KB, Mitchell H, Lynn H. Reported difficulties in access to quality care for children with asthma in the inner city. Archives of Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine. 1998;151:333–339. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.4.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan GJ, Brooks-Gunn J. Consequences of growing up poor. New York: Russel Sage Publications; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Evans R, English K. The environment of poverty: Multiple stressor exposure, psychophysiological stress, and socioemotional adjustment. Child Development. 2002;73:1238–1248. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Institute of Medicine. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson J, Williams D. Detroit Area Study, 1995: Social influence on health: Stress, racism, and health protective resources. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Kattan M, Mitchell H, Eggleston P, Gergen P, Crain E, Redline S, et al. Characteristics of inner-city children with asthma: The National Cooperative Inner-City Asthma Study. Pediatric Pulmonology. 1997;24:253–262. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-0496(199710)24:4<253::aid-ppul4>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kattan M, Stearns SC, Crain EF, Stout JW, Gergen PJ, Evans R, III, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a home-based environmental intervention for inner-city children with asthma. Journal of Clinical Immunology. 2005;116:1058–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.07.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koinis Mitchell D, McQuaid E, Seifer R, Kopel S, Esteban C, Canino G, et al. Multiple urban and asthma-related risks and their association with asthma morbidity in children. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2007;32:582–595. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsl050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koinis-Mitchell D, McQuaid EL, Friedman D, Colon A, Soto J, Rivera DV, et al. Latino caregivers’ beliefs about asthma: Causes, symptoms, and practices. Journal of Asthma. 2008;45:205–210. doi: 10.1080/02770900801890422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieu TA, Finkelstein JA, Lozano P, Capra AM, Chi FW, Jensvold N, et al. Cultural competence policies and other predictors of asthma care quality for Medicaid-insured children. Pediatrics. 2004;114:102–110. doi: 10.1542/peds.114.1.e102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel M, Paxson C, Waldfogel J. Racial disparities in childhood asthma in the United States: Evidence from the National Health Interview Survey, 1997 to 2003. Pediatrics. 2006;117:e868–e877. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid EL, Vasquez J, Glorisa C, Fritz GK, Ortega AN, Colon A, et al. Beliefs and barriers to medication use in parents of Latino children with asthma. Pediatric Pulmonology. 2009;44:892–898. doi: 10.1002/ppul.21074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McQuaid E, Walders N, Kopel S, Fritz G, Klinnert M. Pediatric asthma management in the family context: The Family Asthma Management System Scale. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30:492–502. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health. Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma-update on selected topics 2002 (No. DHHS Publication No. (NIH) 02-3659) Bethesda, MD: National Institutes of Health; 2002. National asthma education and prevention program, expert panel, report. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson DA, Johnson CC, Divine GW, Strauchman C, Joseph CL, Ownby DR. Ethnic differences in the prevalence of asthma in middle class children. Annals of Allergy and Asthma Immunology. 1997;78:21–26. doi: 10.1016/S1081-1206(10)63365-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega A, Gergen P, Paltiel A, Bauchner H, Belanger K, Leaderer B. Impact of site care, race, and Hispanic ethnicity on medication use for childhood asthma. Pediatrics. 2002;109:E1. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlman DN, Zierler S, Meersman S, Kim HK, Viner-Brown SI, Caron C. Race disparities in childhood asthma: Does where you live matter? Journal of the National Medical Association. 2006;98:239–247. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand CS. Adherence to asthma therapy in the preschool child. Allergy. 2002;57:48–57. doi: 10.1034/j.1398-9995.57.s74.7.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rand CS, Butz AM, Kolodner K, Huss K, Eggleston P, Malveaux F. Emergency department visits by urban African American children with asthma. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 2000;105:83–90. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(00)90182-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resnick M, Bearman P, Blum R, Bauman K, Harris K, Jones J, et al. Protecting adolescents from harm. Findings in the National Longitudinal Study on Adolescent Health. Journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;278:823–832. doi: 10.1001/jama.278.10.823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosier MJ, Bishop J, Nolan T, Robertson CF, Carlin JB, Phelan PD. Measurement of functional severity of asthma in children. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 1994;149:1434–1441. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.6.8004295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Solis JM, Marks G, Garcia M, Shelton D. Acculturation, access to care, and use of preventive services by Hispanics: Findings from HHANES, 1982–84. American Journal of Public Health. 1990;80:11–19. doi: 10.2105/ajph.80.suppl.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szalacha LA, Erkut S, Garcia Coll C, Alarcon O, Fields JP, Ceder I. Discrimination and Puerto Rican children’s and adolescents’ mental health. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2003;9:141. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.9.2.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. The 2005 HHS poverty guidelines. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wamboldt FS, Ho J, Milgrom H, Wamboldt MZ, Sanders B, Szefler SJ, et al. Prevalence and correlates of household exposures to tobacco smoker and pets in children with asthma. Journal of Pediatrics. 2002;141:109–115. doi: 10.1067/mpd.2002.125490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warman KL, Silver EJ, Stein RE. Asthma symptoms, morbidity, and anti-inflammatory use in inner-city children. Pediatrics. 2001;108:277–282. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright RJ, Mitchell H, Visness CM, Cohen S, Stout J, Evans R, et al. Community violence and asthma morbidity: The inner-city asthma study. American Journal of Public Health. 2004;94:625–632. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.4.625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]