Abstract

Heat-stable nucleoid structuring protein (H-NS) is an abundant prokaryotic protein that plays important roles in organizing chromosomal DNA and gene silencing. Two controversial binding modes were identified. H-NS binding stimulating DNA bridging has become the accepted mechanism, whereas H-NS binding causing DNA stiffening has been largely ignored. Here, we report that both modes exist, and that changes in divalent cations drive a switch between them. The stiffening form is present under physiological conditions, and directly responds to pH and temperature in vitro. Our findings have broad implications and require a reinterpretation of the mechanism by which H-NS regulates genes.

Keywords: Heat-stable nucleoid structuring protein (H-NS), gene silencing, transcriptional regulation, pathogenicity islands, atomic force microscopy, magnetic tweezers

Heat-stable nucleoid structuring protein (H-NS) is present at 20,000 copies per cell, and preferentially binds to A-T-rich DNA (Grainger et al. 2006; Lucchini et al. 2006; Navarre et al. 2006). Some sequence-dependent high-affinity DNA sequences may serve as nucleation sites for H-NS binding to DNA (Rimsky et al. 2001; Bouffartigues et al. 2007). H-NS exists as a dimer and has the ability to self-associate (Bloch et al. 2003), forming higher-order oligomers (Smyth et al. 2000). The C-terminal domain binds DNA (residues 90–136), while the N terminus is involved in dimerization (residues 1–64). The two domains are connected via an unstructured linker comprised of residues 65–89 (Esposito et al. 2002). DNA binding by H-NS is sensitive to environmental factors such as temperature and pH (Atlung and Ingmer 1997; McLeod and Johnson 2001; Amit et al. 2003).

H-NS has two distinct biological functions. First, it plays a role in the compaction of the nucleoid (Spassky et al. 1984; Spurio et al. 1992; Stavans and Oppenheim 2006). Second, H-NS also serves an important function in gene silencing (for recent reviews, see Rimsky 2004; Dorman 2007; Navarre et al. 2007; Fang and Rimsky 2008). Recent studies have proposed a unique role of H-NS in keeping horizontally acquired genes in pathogens switched off until conditions are right for expression of virulence (Lucchini et al. 2006; Navarre et al. 2006, 2007). Thus, H-NS serves as an “immune sentinel,” preventing foreign genes from being deleterious to their host. Understanding the role of H-NS in silencing and the mechanisms that relieve silencing has been a major focus of recent studies, but the mechanisms have remained obscure (Heroven et al. 2004; Walthers et al. 2007; Perez et al. 2008).

A long-held view is that these dual roles of H-NS are a function of its structural and mechanical modifications to DNA upon binding. It was reported previously using atomic force microscopy (AFM) imaging and optical tweezers that H-NS binding led to formation of DNA bridges; i.e., two DNA segments were linked to each other in parallel (Dame et al. 2000, 2006). Hereafter, we refer to this binding as the “bridging mode.” A controversy resulted from an experiment using magnetic tweezers (MT) (Amit et al. 2003). In that experiment, the bridging mode of binding was not detected over a wide protein concentration range and forces. Instead, the DNA adopted a more extended and stiffer configuration upon H-NS binding compared with naked DNA substrates. Hereafter, we refer to this binding as the “stiffening mode.” Efforts to resolve the discrepancy were unsuccessful (for a detailed discussion, see the Supplemental Material; Amit et al. 2003, 2004; Dame and Wuite 2003). Subsequently, numerous studies of the bridging mode resulted in its becoming the accepted mechanism of H-NS binding to DNA, whereas the stiffening mode has been largely ignored. For example, recent discussions of H-NS gene regulation were based mostly on the bridging binding mode (Stoebel et al. 2008). In the present study, we resolve these discrepancies using MT and AFM imaging methods. We report that the switch between the two binding modes of H-NS can be mediated by switching the magnesium or calcium concentration, and that the stiffening and bridging binding modes can coexist under certain ionic conditions. Thus, our results clearly identify two distinct but switchable mechanisms of H-NS binding to DNA that have not been reported previously. Furthermore, our results demonstrate that H-NS can interconvert between these two binding modes without being released from the DNA. This raises several questions as to whether both binding modes are physiologically relevant, whether one mode is preferred, and whether the switching between the two modes is biologically significant.

Results and Discussion

Magnesium ion alters the mode of H-NS binding to DNA

We noticed that the reaction buffer used by Dame et al. (2000, 2006) contained 10 mM MgCl2, whereas the buffer used by Amit et al. (2003) did not contain divalent cations. We thus hypothesized that the discrepancy between the stiffening mode and bridging mode of H-NS binding to DNA might result from differences in buffer conditions. Our results supported this hypothesis (see below). Unless specifically mentioned, the experiments described in the subsequent paragraphs were performed at pH 7.4 and 24°C.

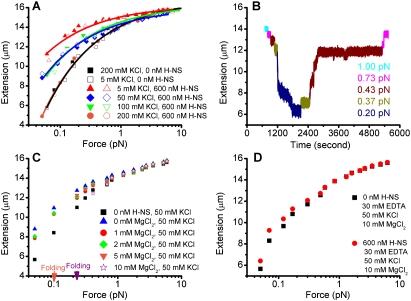

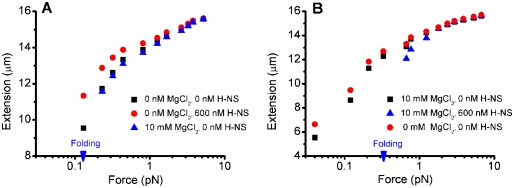

We first measured force extension curves (i.e., the end-to-end distance of the DNA as a function of force) in buffers similar to those used by Amit et al. (2003) at a fixed H-NS concentration of 600 nM. Under these conditions, we obtained similar results to those reported previously, as shown in Figure 1A. DNA stiffening, as evidenced by increased extension under the respective forces, was observed in 5, 50, and 100 mM KCl. Furthermore, the stiffening effect was stronger in lower KCl solutions (Fig.1A, see red triangles), and was negligible in 200 mM KCl buffer where the force extension curves were identical in the absence and presence of H-NS (Fig.1A, cf. black squares and orange circles). Last, no DNA folding (bridging) was apparent under forces ranging from 0.05 pN up to 20 pN under all conditions examined. The stiffening effects were observed in a wide range of H-NS concentrations (60 nM to 2.4 μM), and saturation was reached at ∼600 nM (Supplemental Fig. S1A). These measurements represented final equilibrium states (i.e., the extension of DNA did not change over time); thus, force extension curves were plotted.

Figure 1.

Magnesium-dependent binding modes of H-NS. (A) Force extension curve of DNA in the absence of magnesium. Two independent data sets are shown at each KCl concentration. The solid and open squares are the reference curves of DNA in buffers alone. The DNA becomes less stiff (less extended at the respective forces) as the KCl concentration increases. (B) Time course of DNA folding/unfolding in the presence of 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 600 nM H-NS. Folding occurred at 0.2 pN and unfolding occurred at 0.43 pN. Complete unfolding occurred at 0.73 pN. It is a representative example of five experiments that were performed, in which folding occurred under 0.2–0.3 pN of force and subsequent unfolding occurred under 0.4–1 pN. (C) Switching H-NS from stiffening to bridging mode by increasing the concentration of MgCl2. Apparent stiffening occurred at ≤5 mM MgCl2. Folding (bridging) occurred at ≥5 mM MgCl2. The orange arrow indicates folding at ∼0.1 pN in the presence of 5 mM MgCl2. This bridged DNA was then completely unfolded at a larger force of ∼7 pN, during which the MgCl2 concentration was increased to 10 mM. The force was then incrementally reduced in the 10 mM MgCl2 buffer (purple stars), and bridging occurred at a higher stretching force (>0.2 pN; purple arrow). Stiffening (>0.1 pN) and folding (≤0.1 pN) coexist at 5 mM MgCl2. The H-NS concentration was fixed at 600 nM. (D) Effect of magnesium chelation by EDTA. The resulting extension of DNA in the presence of H-NS (red solid circles) is longer than that in the absence of H-NS (black squares), indicating that the DNA becomes stiffer. No folding was observed in the force range applied.

We next investigated the binding of H-NS to DNA in buffers similar to those used by Dame et al. (2006) containing 50 mM KCl and 10 mM MgCl2. The H-NS concentration was again fixed at 600 nM. Interestingly, dramatic DNA folding occurred in this magnesium-containing buffer under small forces, but no folding occurred in the absence of MgCl2 (see Fig. 1A). Figure 1B shows the time course of DNA extension under different forces. We first decreased the force step by step. At each force, we recorded the DNA extension for ∼1 min. If there was an extension change, we then recorded for a longer time to obtain the folding or unfolding dynamics under the same force. No dramatic folding occurred at forces >0.2 pN. At ∼0.2 pN of force, the extension was substantially reduced, indicating that a large-scale folding occurred (Fig.1B, shown in dark blue). Unfolding occurred at 0.43 pN (Fig.1B, wine curve), and most of the folded DNA was unfolded. At a force of 0.73 pN, the DNA was completely unfolded (Fig.1C, note that the two purple curves before folding and after unfolding have the same extension). When these data were translated into a force extension curve (Supplemental Fig. S1B), the DNA extension curve overlapped that of naked DNA before folding at 0.2 pN, indicating that, prior to folding, DNA was similar in rigidity to naked DNA. In the force extension curve representation, the folding or unfolding was indicated by arrows at the respective forces, because the final equilibrium states after folding could not be defined. These observations were in agreement with the DNA bridging experiments as reported earlier (Dame et al. 2006). Folding was observed over the range of 60 nM to 2.4 μM concentrations of H-NS (Supplemental Fig. S1C for folding at 60 nM; Fig. 5B for 2.4 μM H-NS). At 10 mM MgCl2 and 600 nM H-NS, folding occurred at all concentrations of KCl investigated in our experiments: 5 mM (Supplemental Fig. S2A), 50 mM (Fig. 1B, purple data in C), and 150 mM (Supplemental Fig. S2B, weak folding only).

Figure 5.

Precoated DNA can still fold under bridging buffer conditions (pH 7.4, 10 mM MgCl2, 50 mM KCl). (A) At 600 nM H-NS, DNA was kept in an extended conformation under 2.6 pN for ∼1 h. When the force was subsequently decreased to ∼0.25 pN, folding occurred (in red). (B) A similar experiment as in A was performed at 2.4 μM H-NS. Again, folding occurred when the force decreased to ∼0.25 pN (in red). Compared with the folding observed in the presence of 600 nM H-NS, the folding speed in 2.4 μM H-NS was reduced by >30-fold.

Magnesium acts as a switch between stiffening and bridging

In the experiment shown in Figure 1, A and B, we demonstrated that H-NS binding to DNA led to stiffening in the absence of MgCl2 and bridging in the presence of 10 mM MgCl2. This indicated that magnesium could cause the switching from one binding mode to the other, which has not been observed previously. We therefore examined the switching between the two binding modes in detail by gradually changing the concentration of magnesium in buffers containing 50 mM KCl and 600 nM H-NS.

Figure 1C shows the force extension curves prepared by increasing the MgCl2 concentration from 0 to 10 mM using the same DNA during the scanning process. At each concentration, the force was scanned from larger forces to smaller forces. Our results indicated that, as the magnesium concentration increased, DNA rigidity decreased; i.e., the DNA was less extended at each respective force. At 5 mM MgCl2 (Fig.1C, orange triangles), folding occurred against ∼0.1 pN force (Fig.1C, orange arrow). This bridged DNA was then completely unfolded at a larger force of ∼7 pN, and the MgCl2 concentration was increased to 10 mM. The force was then gradually decreased in the 10 mM MgCl2 buffer (Fig.1C, purple stars), and dramatic bridging occurred at a larger stretching force (>0.2 pN) (Fig.1C, purple arrow). Thus, stiffening of DNA was observed at 0–5 mM MgCl2, whereas folding (bridging) was observed in 5–10 mM MgCl2. At 5 mM, both stiffening (force >0.1 pN) and bridging (force ≤0.1 pN) were observed. Addition of 30 mM EDTA in the presence of H-NS and 10 mM Tris (pH 7.4), 50 mM KCl, and 10 mM MgCl2, led to DNA stiffening, and the stiffened DNA could not be folded (Fig. 1D). This was presumably due to chelation of magnesium by EDTA and was consistent with our results that magnesium switched the H-NS-binding mode (Fig. 1A–C). Switching between stiffening and bridging was also observed at 5 mM and 150 mM KCl when the magnesium concentration was varied in the range between 0 mM and 10 mM (Supplemental Fig. S2A,B) at a fixed H-NS concentration of 600 nM. At 150 mM KCl, the folding at 10 mM MgCl2 was weak (Supplemental Fig. S2B). The folding capability can be enhanced at this KCl concentration by increasing the concentration of H-NS to 2.4 μM (Supplemental Fig. S2C). Similarly, CaCl2 could also promote the switch to the bridging binding mode (Supplemental Fig. S2D,E).

Stiffening results from cooperative H-NS polymerization along DNA

We observed DNA stiffening in KCl and MgCl2 buffers of <200 mM and 5 mM, respectively (Fig. 1). Yet the mechanism of DNA binding by H-NS that resulted in stiffening remained unclear. We considered the following two possibilities: (1) Random binding with high occupation number (i.e., the linear density of bound protein is large) could lead to stiffening if each binding event can locally stiffen the DNA backbone (Yan and Marko 2003), or (2) cooperative polymerization along the DNA leading to a more rigid H-NS/DNA cofilament. To investigate these possibilities, we performed AFM imaging of the DNA–H-NS complexes in the DNA-stiffening buffers employed previously.

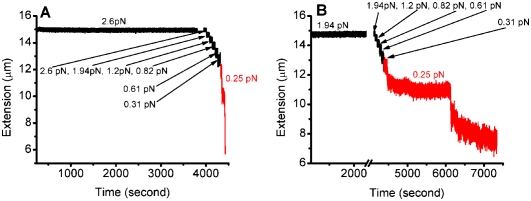

Figure 2, A–D, shows four representative AFM images of 0.14 nM DNA incubated with 600 nM H-NS for 40 min (Fig. 2A,B) and for 240 min (Fig. 2C,D) in 5 mM KCl and 0 mM MgCl2. Under these conditions, the ratio of H-NS monomer per base pair is 0.8. Figure 2, A and B, reveals that H-NS polymerized along the DNA and formed disconnected islands, suggesting that a nucleation event was required for the extension of the protein-coated regions. Figure 2, C and D, indicated that, at longer incubation times, the disconnected regions merged, leading to fully coated DNA. In Figure 2, C and D, completely uncoated DNA was also visible. This result was in complete agreement with a nucleation polymerization mode, where H-NS protein tended to condense at nucleation sites and polymerize on the same DNA. Thus, our results indicated that, under DNA-stiffening conditions, H-NS cooperatively polymerized along DNA. AFM imaging was also performed in buffers containing 50 mM KCl and 0 mM MgCl2 (Supplemental Fig. S3A,B), and 1 mM MgCl2 (Supplemental Fig. S3C,D). The majority of DNA was found in the extended form. The rigid islands were still seen, but with lower contrast than was observed in Figure 2, A–D. Taken together, these observations indicated that, as the KCl concentration increased, protein occupation on DNA decreased (see also Fig. 1A), and H-NS interaction with the mica surface was favored. Furthermore, it indicated an electrostatic nature of H-NS binding to DNA in the range of 0–1 mM MgCl2, where the DNA-stiffening mode of binding predominated.

Figure 2.

(A–D) AFM imaging of DNA–H-NS complexes under stiffening conditions. The buffer (pH 7.4) contained 10 mM Tris, 5 mM KCl, 0 mM MgCl2, and 600 nM H-NS. (A,B) Incubated for 40 min. (C,D) Incubated for 4 h. The brighter regions indicate the H-NS-bound regions, while the darker regions indicate the naked DNA backbone. (E–G) Imaging of DNA–H-NS complexes under bridging conditions. The buffer (pH 7.4) contained 10 mM Tris, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2, and 600 nM H-NS. Incubation time was fixed at 40 min. Large linear hairpin forms and circular forms were observed. (H) Two boundary conformations of the seeding loop: almost anti-parallel (left), and almost parallel (right).

During folding (bridging), large DNA hairpin structures form

It was therefore of interest to determine what contributed to the DNA folding observed in the buffers containing MgCl2. Images obtained in 50 mM KCl and 10 mM MgCl2 showed linear hairpins with end loops (Fig. 2E–G; see arrows). The linear hairpin structures clearly indicated the formation of large-scale DNA bridging, and the end loop likely resulted from the competition between the bridging energy and the bending energy of DNA. In addition to linear DNA hairpins, circular DNA conformations were also observed, even though linear DNA was used in the reaction. In some of the circular forms, “holes” were evident (e.g., see Fig. 2E), indicating that these circular forms were still bridged DNA molecules. Bridging can form two different structures, since the orientation at two remote DNA sites varies as they meet prior to bridging. If their orientations were anti-parallel (or nearly so), bridging favored the formation of hairpins (Fig. 2H, left). On the other hand, if they were parallel (or nearly so), bridging favored formation of the circular conformations (Fig. 2H, right). Similar hairpin structures were also observed in 5 mM MgCl2, but the imaging contrast was not as good (Supplemental Fig. S3E–H).

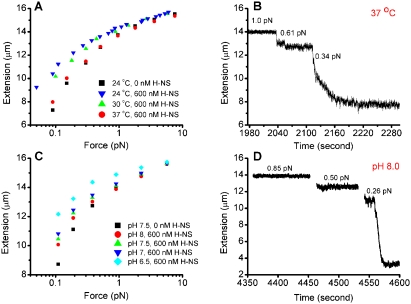

The stiffening binding mode is directly susceptible to environmental stimuli temperature and pH

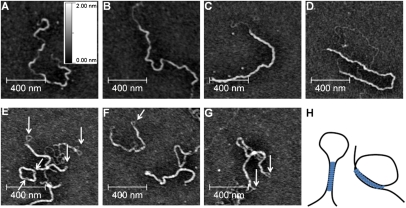

Temperature and pH are known modulators of H-NS activity (Atlung and Ingmer 1997; Williams and Rimsky 1997; Prosseda et al. 1998; McLeod and Johnson 2001). We therefore investigated how the two binding modes of H-NS responded to these stimuli. The stiffening binding mode of H-NS was exquisitely sensitive to changes in temperature ranging from 24°C to 37°C (Fig. 3A). Increasing the temperature decreased the stiffening effects to the point where, at 37°C, almost no stiffening was apparent. This observation was in agreement with earlier reports (Amit et al. 2003). In contrast, in the bridging binding mode, H-NS was insensitive to temperature changes. Large-scale bridging at ∼0.3 pN was still evident at 37°C (Fig. 3B). The stiffening binding mode was also sensitive to changes in pH (Fig. 3C). Increasing the pH from 6.5 to 8 decreased the stiffening effects. Again, the bridging mode was not susceptible to pH changes, since the DNA was still folded against ∼0.3 pN force during the entire pH range that we examined up to pH 8. The results obtained at pH 8 are shown in Figure 3D. These results were consistent with studies in Shigella and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli, where H-NS repressed virF expression at low temperature and low pH (Prosseda et al. 1998). Although the in vivo responses to temperature and pH may be more complex, our results highlight the importance of the stiffening mode of H-NS binding in the regulation of virulence gene expression.

Figure 3.

Susceptibility to temperature (A,B) and pH (C,D) under stiffening conditions (50 mM KCl and 0 mM MgCl2) and under bridging conditions (50 mM KCl and 10 mM MgCl2). (A) The stiffening effect decreases as the temperature increases. (B) The bridging mode was not affected by changing the temperature. At 37°C, folding still occurred at ∼0.3 pN. (C) Stiffening decreases with alkaline pH. (D) Bridging was unaffected by changing the pH in the same range; i.e., folding still occurred at ∼0.3 pN at pH 8.

H-NS can switch between stiffening and bridging modes while bound to DNA

It was of interest to determine whether H-NS must first dissociate from the DNA in order to switch between these two binding modes. For this experiment, we began with H-NS bound to DNA in the stiffening mode (600 nM H-NS, 5 mM KCl, 0 mM MgCl2). When we switched to the bridging buffer (50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2) in the absence of H-NS, we observed folding (Fig. 4A). We then performed the opposite experiment, starting with folded DNA in the bridging mode (600 nM H-NS, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2) and switching to a stiffening buffer (5 mM KCl, 0 mM MgCl2) in the absence of H-NS, and we observed stiffening (Fig. 4B). Thus, it is apparent that H-NS is capable of interconverting between the stiffening and bridging forms. H-NS remained bound during this process, because there was no additional H-NS present after the buffers were switched to promote the other mode of binding.

Figure 4.

H-NS interconverts between bridging and stiffening modes without being released from DNA. (A) Switching from stiffened DNA in 600 nM H-NS, 5 mM KCl, and 0 mM MgCl2 to bridging buffer in the absence of H-NS (0 mM H-NS, 50 mM KCl, 10 mM MgCl2) resulting in bridging. The blue arrow on the force axis indicates the force where the folding occurred. (B) Switching from bridged DNA in 600 nM H-NS, 50 mM KCl, and 10 mM MgCl2 to stiffening buffer in the absence of H-NS (0 mM H-NS, 5 mM KCl, 0 mM MgCl2) resulted in stiffening.

Precoated DNA molecules can associate under bridging conditions

It was reported previously that precoated DNA molecules could not associate to form bridges (Dame et al. 2006). Our experiments are in disagreement with this result. For example, we showed that H-NS is capable of interconverting between the stiffening and bridging forms without dissociating from DNA (Fig. 4). In another example, at 600 nM and 2.4 μM H-NS in bridging buffer, DNA that was maintained in an extended conformation by force for >1 h could still be folded when the force was decreased (Fig. 5A). One possible explanation for this discrepancy was the slower rate of folding at higher concentrations of H-NS employed: Most of our experiments were conducted with 600 nM H-NS rather than 2 μM H-NS (Dame et al. 2006). As shown in Figure 5B, in 2.4 μM H-NS, the DNA still folded when the force was decreased to ∼0.25 pN, but with a dramatically reduced folding speed compared with the folding speed in 600 nM H-NS (Fig. 5A). In comparison with the folding observed in the presence of 600 nM H-NS, the folding speed at 2.4 μM was reduced by >30-fold. Although their experimental time scale is not known, this likely explains why the authors of the previous study did not observe bridging with precoated DNA (Dame et al. 2006).

Mechanisms of H-NS-mediated DNA stiffening and DNA folding

We showed the existence of both the stiffening and the bridging binding modes of H-NS and the switch between them by adjusting the concentrations of magnesium and calcium. The binding mode of H-NS was not a result of increasing DNA occupancy, since our data show that changes in the concentrations of H-NS and KCl over large ranges did not change the binding modes (Fig. 1A; Supplemental Figs. S1A, S2A–E; see also the discussion in Amit et al. 2004). In other words, binding mode switching requires a change in concentration of magnesium or calcium. In both binding modes, H-NS cooperatively binds to DNA. In the stiffening mode, binding is a nucleated linear polymerization process starting from a few nucleation sites that are likely sequence-dependent. In the bridging mode, binding is also a nucleation process, where the nucleation sites are the DNA loops formed by thermal fluctuations that obviously lack sequence selectivity. The specific mechanism by which magnesium and calcium ions alter H-NS-binding properties is currently unknown, but is under investigation in our laboratory.

The stiffening binding mode is highly likely a physiologically relevant form

Most importantly, our results strongly suggest that the previously ignored stiffening binding mode is physiologically relevant. The physiological concentration of free magnesium is ∼1 mM (Martin-Orozco et al. 2006) and calcium is ∼100–300 nM (Dominguez 2004). Our results show that, under these conditions, H-NS is bound to DNA in the stiffening/polymerization mode (Fig. 1; Supplemental Figs. S1A, S2A–D). In addition to divalent ions such as magnesium and calcium, multivalent polyamines are also present. For example, in E. coli, the concentration of spermidine is in the range of 1–3 mM (Shah and Swiatlo 2008). In the presence of 1 mM spermidine in stiffening buffer (50 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, 300 nM CaCl2), H-NS binds to DNA in the stiffening mode (Supplemental Fig. S4). Of course, the actual in vivo conditions are much more complex than our in vitro buffer conditions. Taken together, our results indicate the stiffening binding mode of H-NS is highly likely a physiologically relevant form.

A role for the stiffening mode of H-NS binding in gene silencing

As mentioned above, H-NS plays two roles in vivo. A potential role for the bridging mode of H-NS binding might be to compact the nucleoid. Of course, this binding mode may play a role in gene regulation under certain conditions. An interesting question remains: What role does the previously ignored stiffening binding mode play in vivo? As shown in Figure 2, A–D, in the stiffening binding mode, the decoration of DNA by H-NS initiates at discrete sites at early times. It was reported that, at some promoters, a “nucleation site” initiates binding (Williams and Rimsky 1997). At low MgCl2 concentrations, polymerization of H-NS may initiate from these nucleation sites, and the H-NS coating region may extend to cover a larger distance, including promoter regions. Therefore, one obvious possibility is that H-NS coats DNA in the stiffening mode of binding, making promoter regions less accessible to RNA polymerase, leading to gene silencing. The importance of the stiffening mode in gene silencing is further supported by its direct susceptibility to temperature and pH (Fig. 3A–C), since these stimuli are known modulators of H-NS activity (Atlung and Ingmer 1997; Williams and Rimsky 1997; Prosseda et al. 1998; McLeod and Johnson 2001). In addition to these environmental factors, numerous regulators are involved in derepressing the genes silenced by H-NS (Stoebel et al. 2008). Therefore, relief of silencing is likely a function of the binding mode and the respective antagonizing proteins. Hence, investigation of competition of transcription factors with H-NS for binding to DNA under various ionic conditions will be worthwhile. A logical candidate for such studies is SsrB, a protein that combines the roles of H-NS antagonist and transcriptional activator in regulating expression of diverse genes located on Salmonella pathogenicity island-2 (Walthers et al. 2007), which is currently under investigation in our laboratories.

Materials and methods

Overexpression and purification of H-NS

The pBAD plasmid was used to express H-NS with a 6X-His tag at the C terminus. More detailed information is provided in the Supplemental Material.

AFM imaging

Linearized PhiX174 DNA (5386 base pairs) was deposited on a glutaraldehyde-coated mica surface in AFM imaging experiments. More detailed information is provided in the Supplemental Material.

MT measurements

Single DNA molecules were stretched by a transverse MT in the focal plane (Yan et al. 2004). λ-DNA molecules (48.5 kb) were end-labeled using biotin- and digoxygenin-labeled oligonucleotides, as described in Smith et al. (1992). An image of the setup and more details are included in the Supplemental Material (Supplemental Fig. S5).

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Mike Maguire (Case Western Reserve University), Dr. Ferric Fang (University of Washington), and Dr. Sankar Adhya (NIH) for stimulating discussions. We thank Dr. Jay Mellies (Reed College, Portland, OR) for the kind gift of pBAD-hns, Dr. Michael P. Sheetz (Columbia University and National University of Singapore), and Dr. Ganesh Anand (National University of Singapore) for helpful discussions, and Yuen Peng (Mechanobiology RCE, National University of Singapore) for protein purification. This work was supported by grants GM-058746 from the National Institutes of Health, MCB-0613014 from the National Science Foundation, and 1I01BX000372 from the Veterans Administration (to L.J.K.); and R144000192112 and R144000251112 from the Ministry of Education of Singapore (to J.Y.). We are grateful for initial support from the Mechanobiology Program at the National University of Singapore (now RCE in Mechanobiology). Y.L. and H.C. performed the experiments and Y.L., H.C., and J.Y. analyzed the data. L.J.K. and J.Y. conceived the experiments and wrote the paper.

Footnotes

Article is online at http://www.genesdev.org/cgi/doi/10.1101/gad.1883510.

Supplemental material is available at http://www.genesdev.org.

References

- Amit R, Oppenheim AB, Stavans J. Increased bending rigidity of single DNA molecules by H-NS, a temperature and osmolarity sensor. Biophys J. 2003;84:2467–2473. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)75051-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amit R, Oppenheim AB, Stavans J. Single molecule elasticity measurements: A biophysical approach to bacterial nucleoid organization. Biophys J. 2004;87:1392–1393. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.039503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlung T, Ingmer H. H-NS: A modulator of environmentally regulated gene expression. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:7–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3151679.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloch V, Yang YS, Margeat E, Chavanieu A, Auge MT, Robert B, Arold S, Rimsky S, Kochoyan M. The H-NS dimerization domain defines a new fold contributing to DNA recognition. Nat Struct Biol. 2003;10:212–218. doi: 10.1038/nsb904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouffartigues E, Buckle M, Badaut C, Travers A, Rimsky S. H-NS cooperative binding to high-affinity sites in a regulatory element results in transcriptional silencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2007;14:441–448. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dame RT, Wuite GJ. On the role of H-NS in the organization of bacterial chromatin: From bulk to single molecules and back. Biophys J. 2003;85:4146–4148. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)74826-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dame RT, Wyman C, Goosen N. H-NS mediated compaction of DNA visualised by atomic force microscopy. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28:3504–3510. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.18.3504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dame RT, Noom MC, Wuite GJ. Bacterial chromatin organization by H-NS protein unravelled using dual DNA manipulation. Nature. 2006;444:387–390. doi: 10.1038/nature05283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez DC. Calcium signalling in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 2004;54:291–297. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04276.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorman CJ. H-NS, the genome sentinel. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2007;5:157–161. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito D, Petrovic A, Harris R, Ono S, Eccleston JF, Mbabaali A, Haq I, Higgins CF, Hinton JC, Driscoll PC, et al. H-NS oligomerization domain structure reveals the mechanism for high order self-association of the intact protein. J Mol Biol. 2002;324:841–850. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)01141-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fang FC, Rimsky S. New insights into transcriptional regulation by H-NS. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2008.02.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grainger DC, Hurd D, Goldberg MD, Busby SJ. Association of nucleoid proteins with coding and non-coding segments of the Escherichia coli genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:4642–4652. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heroven AK, Nagel G, Tran HJ, Parr S, Dersch P. RovA is autoregulated and antagonizes H-NS-mediated silencing of invasin and rovA expression in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis. Mol Microbiol. 2004;53:871–888. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2004.04162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lucchini S, Rowley G, Goldberg MD, Hurd D, Harrison M, Hinton JCD. H-NS mediates the silencing of laterally acquired genes in bacteria. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e81. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin-Orozco N, Touret N, Zaharik ML, Park E, Kopelman R, Miller S, Finlay BB, Gros P, Grinstein S. Visualization of vacuolar acidification-induced transcription of genes of pathogens inside macrophages. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:498–510. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-12-1096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLeod SM, Johnson RC. Control of transcription by nucleoid proteins. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2001;4:152–159. doi: 10.1016/s1369-5274(00)00181-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarre WW, Porwollik S, Wang Y, McClelland M, Rosen H, Libby SJ, Fang FC. Selective silencing of foreign DNA with low GC content by the H-NS protein in Salmonella. Science. 2006;313:236–238. doi: 10.1126/science.1128794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarre WW, McClelland M, Libby SJ, Fang FC. Silencing of xenogeneic DNA by H-NS-facilitation of lateral gene transfer in bacteria by a defense system that recognizes foreign DNA. Genes & Dev. 2007;21:1456–1471. doi: 10.1101/gad.1543107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez JC, Latifi T, Groisman EA. Overcoming H-NS-mediated transcriptional silencing of horizontally acquired genes by the PhoP and SlyA proteins in Salmonella enterica. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:10773–10783. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709843200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prosseda G, Fradiani PA, Di Lorenzo M, Falconi M, Micheli G, Casalino M, Nicoletti M, Colonna B. A role for H-NS in the regulation of the virF gene of Shigella and enteroinvasive Escherichia coli. Res Microbiol. 1998;149:15–25. doi: 10.1016/s0923-2508(97)83619-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimsky S. Structure of the histone-like protein H-NS and its role in regulation and genome superstructure. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2004;7:109–114. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2004.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rimsky S, Zuber F, Buckle M, Buc H. A molecular mechanism for the repression of transcription by the H-NS protein. Mol Microbiol. 2001;42:1311–1323. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah P, Swiatlo E. A multifaceted role for polyamines in bacterial pathogens. Mol Microbiol. 2008;68:4–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06126.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SB, Finzi L, Bustamante C. Direct mechanical measurements of the elasticity of single DNA molecules by using magnetic beads. Science. 1992;258:1122–1126. doi: 10.1126/science.1439819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smyth CP, Lundback T, Renzoni D, Siligardi G, Beavil R, Layton M, Sidebotham JM, Hinton JC, Driscoll PC, Higgins CF, et al. Oligomerization of the chromatin-structuring protein H-NS. Mol Microbiol. 2000;36:962–972. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01917.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spassky A, Rimsky S, Garreau H, Buc H. H1a, an E. coli DNA-binding protein which accumulates in stationary phase, strongly compacts DNA in vitro. Nucleic Acids Res. 1984;12:5321–5340. doi: 10.1093/nar/12.13.5321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spurio R, Durrenberger M, Falconi M, Lateana A, Pon CL, Gualerzi CO. Lethal overproduction of the Escherichia-Coli nucleoid protein H-NS—Ultramicroscopic and molecular antopsy. Mol Gen Genet. 1992;231:201–211. doi: 10.1007/BF00279792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stavans J, Oppenheim A. DNA–protein interactions and bacterial chromosome architecture. Phys Biol. 2006;3:R1–R10. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/3/4/R01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoebel DM, Free A, Dorman CJ. Anti-silencing: Overcoming H-NS-mediated repression of transcription in Gram-negative enteric bacteria. Microbiology. 2008;154:2533–2545. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2008/020693-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walthers D, Carroll RK, Navarre WW, Libby SJ, Fang FC, Kenney LJ. The response regulator SsrB activates expression of diverse Salmonella pathogenicity island 2 promoters and counters silencing by the nucleoid-associated protein H-NS. Mol Microbiol. 2007;65:477–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RM, Rimsky S. Molecular aspects of the E. coli nucleoid protein, H-NS: A central controller of gene regulatory networks. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;156:175–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1997.tb12724.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Marko JF. Effects of DNA-distorting proteins on DNA elastic response. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2003;68:011905. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.68.011905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan J, Skoko D, Marko JF. Near-field-magnetic-tweezer manipulation of single DNA molecules. Phys Rev E Stat Nonlin Soft Matter Phys. 2004;70:011905. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.70.011905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]