Abstract

It is estimated that, combined, 400,000 people are diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) or acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome annually in the United States, and both diseases are associated with an unacceptably high mortality rate. Although these disorders are distinct clinical entities, they share pathogenic mechanisms that may provide overlapping therapeutic targets. One example is fibroblast activation, which occurs concomitant with acute lung injury as well as in the progressive fibrosis of IPF. Both clinical entities are characterized by elevations of the profibrotic cytokine, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1. Protein degradation by the ubiquitin–proteasomal system modulates TGF-β1 expression and signaling. In this review, we highlight the effects of proteasomal inhibition in various animal models of tissue fibrosis and mechanisms by which it may regulate TGF-β1 expression and signaling. At present, there are no effective therapies for fibroproliferative acute respiratory distress syndrome or IPF, and proteasomal inhibition may provide a novel, attractive target in these devastating diseases.

Keywords: acute respiratory distress syndrome, transforming growth factor-β1, Smad, ubiquitination

Lung fibrosis is a feature of a number of diseases, including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF), autoimmune collagen vascular diseases, radiation, and the latter stages of acute lung injury (ALI)/acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) (1, 2). After acute or chronic lung injury, a number of adaptive systems are employed to repair/restore alveolar–capillary structure and function (3). The proliferation, differentiation, and migration of epithelial and endothelial cells may repair the injury without fibrosis. More severe injury or improper repair may result in dysregulated proliferation and activation of fibroblasts with increased expression of collagen and other matrix proteins (4). The resulting fibrosis impairs gas exchange, decreases compliance, and contributes to the development of pulmonary hypertension (5). Although ALI/ARDS and IPF are distinct clinical disorders, fibroblast activation and proliferation are important in the pathophysiology of both. It is estimated that 400,000 people are diagnosed with either IPF or ALI/ARDS annually in the United States, and both diseases are associated with high rates of mortality. Multiple therapies have been tested in each disease, including corticosteroids, myelosuppression, and cytokine antagonists, but no effective treatment is currently available.

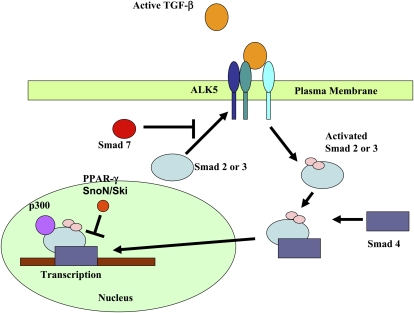

Fibroproliferation after lung injury and the progressive fibrosis that occurs with IPF are characterized by elevations of the profibrotic cytokine, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 (4). TGF-β1 is constitutively present in the lung interstitium in a latent form. Upon injury to the epithelium or endothelium, TGF-β1 is converted from a latent to an active form (6–10). Active TGF-β1 binds to one of a family of TGF-β1 receptors present on the cell surface, activating multiple downstream signaling cascades. Binding of TGF-β1 with the ALK5 receptor on the plasma membrane has been shown to be required for the development of fibrosis in multiple models (11). Activation of the ALK5 receptor induces the phosphorylation of Smad 2,3, sometime referred to as R-smad (12). R-smad recruitment and phosphorylation can be inhibited by the binding of Smad7 to the ALK5 receptor (13). Once phosphorylated, Smad2,3 forms a complex with other Smad proteins, such as smad4, which facilitates translocation to the nucleus (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1 binding of the activin receptor-like kinase (ALK5) receptor induces the phosphorylation of Smad2,3 (R-smads). Smad2,3 forms a complex with Smad4, which then translocates to the nucleus, where it interacts with transcriptional coactivators, such as p300, to regulate gene transcription. Repressors and corepressors, such as peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor (PPAR)-γ, cellular homolog of Sloan-Kettering virus (Ski), and Ski novel gene N (SnoN), are other proteins that regulate the system.

Once in the nucleus, binding of the Smad complex with DNA is regulated by coactivators such as p300 or repressors such as peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor (PPAR)-γ (14). Adding to the complexity are the interactions of corepressors, such as cellular homolog of Sloan-Kettering virus (Ski) and Ski novel gene N (SnoN), both of which can bind to Smad proteins to disrupt the active heteromeric Smad–p300 complex (15).

The consequences of Smad-mediated transcription are cell type specific. In resident lung fibroblasts or fibroblasts recruited from circulating fibrocytes, TGF-β1 stimulates their proliferation and transformation to myoyfibroblasts (16–18). Myofibroblasts are specialized fibroblasts important in tissue repair and fibrosis that express α-smooth muscle actin, secrete increased extracellular matrix and release fibrogenic cytokines (i.e., connective tissue–derived growth factor, platelet-derived growth factor, plasminogen activator inhibitor–1, and others) (16–18). In addition, stimulation of myofibroblasts with TGF-β1 causes them to release active TGF-β1, amplifying the fibrotic signal (18). Myofibroblasts have been reported in biopsy specimens from patients with ARDS and IPF. In epithelial cells, Smad signaling can induce apoptosis or a transition to a mesenchymal phenotype (“epithelial-mesenchymal transition,” or EMT) (3, 19). In rodent models of lung fibrosis, preventing the activation of TGF-β1, blocking the TGF-β1 receptor, inhibiting Smad activation in response to receptor binding, and inhibiting Smad-dependent gene transcription have all been shown to attenuate lung fibrosis in response to bleomycin (4). A similar requirement for TGF-β1 signaling has been observed in lung fibrosis that develops in response to ionizing radiation and asbestos (20). TGF-β1 signaling has also been shown to play a critical role in the fibrosis that develops in the liver, skin, gut, and kidney in response to different fibrogenic stimuli (21). Collectively, this has led investigators to hypothesize that the activation of TGF-β1 serves as a “fibrotic switch” that is turned on in response to injury and turned off after repair (21). Excessive pulmonary fibrosis might result from unregulated activation of TGF-β1 or from its failed down-regulation after alveolar repair.

Smad-dependent pathways are required for the normal regulation of tissue regeneration, inflammation, and fibrosis (21, 22). As a result, strategies that completely inhibit Smad signaling have been associated with significant toxicity. To overcome these difficulties, investigators have focused on pathways that modulate the intensity of Smad signaling or act independent of the Smad pathway in mediating the full TGF-β1–mediated cellular response (23–25). For example, activation of the mitogen-activated protein kinase pathways, including p38 (23), extracellular signal–regulated protein kinase (25), or the c-Jun N-terminal kinase (26), is often required for effective TGF-β1 signaling (27). Imatinib (Gleevec) is an example of a small molecule designed to inhibit Smad-independent signaling by TGF-β1. Imatinib inhibits TGF-β1–induced activation of the tyrosine kinase, c-Abelson, which is required for extracellular matrix expression in fibroblasts. The administration of imatinib to mice was shown to prevent pulmonary fibrosis in the bleomycin model when the drug was administered before the instillation of bleomycin (28, 29), but had minimal effects when given after bleomycin (30). Similarly, PPAR-γ agonists, such as rosiglitazone, have shown efficacy in animal models of fibrosis (31, 32). Their effects against fibrosis are significantly attenuated if administered after bleomycin instillation (33). This may in part be due to the fact that PPAR-γ agonists accelerate degradation of PPAR-γ itself (34), limiting its modulatory effects on TGF-β1 transcription.

UBIQUITIN–PROTEASOME SYSTEM

Since its original description by Ciechanover and colleagues (35–38), the ubiquitin–proteasome system has emerged as a key pathway that defines cellular protein turnover and, consequently, the levels and activity of numerous intracellular proteins. Proteins are targeted for degradation by the covalent linkage of ubiquitin to a lysine residue in the target protein. Ubiquitin is a small, ubiquitously expressed protein that is highly conserved throughout evolution. In most cases, ubiquitin is linked to the substrate protein through an isopeptide bond between the ɛ-amino group of a lysine in the target protein and the COOH-terminal glycine of ubiquitin. Cycles of these reactions link additional ubiquitins to lysines within the previously added ubiquitin (36).

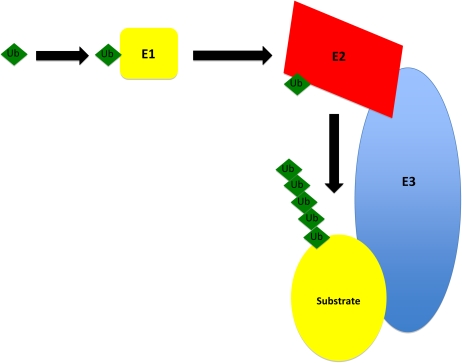

The conjugation of ubiquitin to protein substrates involves a series of hierarchically organized steps (Figure 2) (37). A single E1 ubiquitin–activating enzyme that is present in all mammalian cells catalyzes the formation of an E1 ubiquitin thioester adduct with the COOH-terminal glycine of ubiquitin in a reaction that requires ATP. The E1 enzyme transfers the ubiquitin to members of the E2 ubiquitin carrier protein family (also called ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes). For the majority of proteins, the transfer of ubiquitin from the E2 ligase to the protein targeted for degradation requires the participation of an E3 ubiquitin ligase. The E3 ligases are a large class of a structurally diverse family of proteins that may number in the hundreds in humans (36). They provide selectivity to the ubiquitin process by serving as docking proteins that bring the substrate protein and the E2 carrier protein with activated ubiquitin together. In some instances, accessory proteins also interact with E3 ubiquitin ligases to facilitate substrate recognition. Presently, E3 ubiquitin ligases are grouped into three major families based on structural similarities and the functional classes of substrates they recognize (36, 38).

Figure 2.

Conjugation of ubiquitin to the protein substrate. Ubiquitin (Ub) is activated by E1, an ATP-dependent activating enzyme. Ubiquitin is then transferred to E2, a conjugating enzyme, which further transfers activated ubiquitin to a unique ubiquitin ligase E3. Polyubiquitin is generated by the addition of multiple ubiquitin moieties.

THE 26S PROTEASOME AND INHIBITORS

The proteasome is located both in the cytoplasm and the nucleus (36). It has a barrel-like structure that is capped at each end by regulatory 19S proteins. The barrel moiety or core 20S particle has both scaffold-like and proteinase functions that are ATP dependent. The active-site threonine residues, the hydroxyl groups of which function as the catalytic nucleophils, have three distinct cleavage preferences that are termed chymotryptic, tryptic, and caspase-like. Inhibitors of the proteasome can bind to one or more of these sites to inhibit enzymatic function. The regulatory 19S complex at each end of the barrel functions to recognize, bind, and unwind proteins before degradation. The 20S core and the 19S regulatory units are collectively referred to as the 26S proteasome.

Although the classic description of proteasomes has placed them intracellularly in both the nucleus and cytoplasm, recent evidence points to its presence and possible activity in the extracellular space (39). Proteasome proteins were detected by mass spectrometry and Western blotting in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) of eight healthy subjects undergoing elective surgery. All three proteasome activities were identified, and BAL supernatant successfully cleaved albumin in an ATP- and ubiquitin-independent manner (40). In a subsequent study, BALF from patients with ARDS was found to have increased proteasomal proteins compared with BALF from control subjects, but proteasomal activity was significantly decreased compared with healthy control subjects. In addition, ARDS BALF inhibited proteasome activity when mixed with BAL from healthy patients, suggesting the presence of a soluble inhibitor (41).

The mechanism by which proteasomes end up in the extracellular space has not been studied, but has been speculated to represent cellular damage and necrosis. It is not clear whether extracellular proteasomes may be important for alveolar protein degradation after injury, and if this process can be regulated. There is a report of a potential immunomodulatory role for extracellular proteasomes in certain groups of patients (42).

There are several classes of proteasome inhibitors that can be distinguished by their pharmacophores (Table 1). The first class to be developed was the peptide aldehydes, of which MG-132 is best known. These compounds are cell permeable and useful for in vitro experiments, but their in vivo role is limited by their nonspecificity, as shown by their ability to inhibit both serine and cysteine proteases. Lactacystin is a naturally occurring compound produced by Streptomyces lactacystinaeus, and is a slowly reversible inhibitor of the proteasome. It has limited cell permeability that has precluded its in vivo use. A cell-permeable analog to lactacystin, termed PS-519, has been developed and showed efficacy in an animal model of acute stroke, but its clinical development is unknown (43).

TABLE 1.

EXAMPLES OF PROTEASOME INHIBITOR CLASSES

| Class | Compound | Activity |

|---|---|---|

| Peptide aldehydes | PSI, MG132 | Try, Chy |

| Boronic acid peptides | Bortezomib* | Chy |

| Lactacystin and derivatives | PS-519*, NPI-0052* | Try, Chy, Cas |

| Epoxyketones | Epoxomicin, carfilzomib* | Chy |

Definition of abbreviations: Cas = caspase; Chy = chymotrypsin; PSI = N-benzyloxy-carbonyl-Ile-Glu (O-t-Bu)-Ala-leucinal; Try = trypsin.

Tested in clinical trials.

Bortezomib is a modified dipeptidyl boronic acid that intercalates into an active site of the proteasome to specifically and reversibly inhibit the chymotrypsin-like activity of the 26S proteasome in mammalian cells (44, 45). It is the first proteasomal inhibitor approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of multiple myeloma and mantle cell lymphoma (45). Two new proteasome inhibitors, NPI-0052 and carfilzomib, have been developed, and studies are ongoing to evaluate their clinical characteristics and possible utility for cancer.

UBIQUITINATION/PROTEASOMES AND TGF-β1 SIGNALING

Protein degradation by the ubiquitin–proteasomal system modulates TGF-β1 signaling at multiple steps. The E3 ubiquitin ligases, Smad-ubiquitination–regulatory factor (Smurf)-1 and Smurf2, interact with R-smads to mediate their destruction. The RING finger E3 ligase, Arkadia, is activated upon binding to Smad7, and targets it and the transcriptional repressors, SnoN and cellular Ski (c-Ski), for degradation (46–48). Furthermore, it has been reported that PPAR-γ is degraded by the ubiquitin–proteasome system (34), although the E3 ligase responsible has not been identified. Thus, proteasomal inhibition could modulate TGF-β1 signaling at several potential targets, and potentially abrogate development of tissue fibrosis.

PROTEASOMAL INHIBITION AND FIBROSIS

In addition to its role in removing damaged proteins, the ubiquitin–proteasome system has been shown to play a critical role in the regulation of proteins that affect inflammatory processes, cell growth, and differentiation. Inhibiting the activity of the proteasome prevents substrate degradation, which leads to modulation of associated proteins that are involved in disease states. Inhibition of these “activated” proteins (e.g., transcription factors, such as NF-κB or hypoxia-inducible factors [HIFs]) can modulate molecular pathways, and the resulting phenotype in disease models. Below, we highlight the effect of proteasomal inhibition on tissue fibrosis and mechanisms by which it may regulate TGF-β1 signaling pathways.

One of the earliest reports on the activity of proteasomal inhibitors on fibrosis was in a rat model of unilateral ureteral obstruction (Table 2). Administration of the peptide aldehyde, N-benzyloxy-carbonyl-Ile-Glu (O-t-Bu)-Ala-leucinal (PSI), inhibited proteasome activity and attenuated the up-regulated gene expression of profibrotic proteins and the development of tubulointerstitial fibrosis, as assessed by histology (49). Another early report tested the efficacy of MG-132 in spontaneously hypertensive rats over a 12-week period. Rats given MG-132 daily showed a 38% attenuation in cardiac fibrosis, as assessed by histology (50). More recently, investigators examined the efficacy of proteasomal inhibition in liver steatosis/fibrosis (51, 52). Specifically, they found that lactcystin, a naturally occurring compound that acetylates the proteasome, prevented steatosis/fibrosis in a mouse–carbon tetrachloride model (51). Furthermore, in a mouse study of bile-duct ligation–induced cirrhosis, a single dose of bortezomib administered 3 days after bile duct ligation significantly attenuated α-smooth muscle actin and collagen expression, as well as severity of histologic fibrosis (52). Bortezomib was also tested in a murine model of thrombopoietin-induced myelofibrosis. After 4 weeks of treatment, bortezomib decreased TGF-β1 levels in marrow fluids and impaired development of marrow and spleen fibrosis. After 12 weeks of treatment, bortezomib also impaired osteosclerosis development and improved 1-year survival from 8 to 89% (53). A single study examined the effect of MG-132 and bortezomib in the mouse model of bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis (54). Daily administration of MG-132 or bortezomib, beginning 24 hours after bleomycin instillation, failed to show attenuation of histologic fibrosis, and twice weekly administration of high-dose bortezomib was associated with toxicity in the bleomycin-treated mice, but not in control mice.

TABLE 2.

EFFICACY OF PROTEASOMAL INHIBITION IN ANIMAL MODELS OF FIBROSIS

| Organ (Ref. No.) | Agent | Assessment |

|---|---|---|

| Kidney (48) | PSI | Histology, protein expression |

| Cardiac (49) | MG-132 | Histology |

| Liver (50, 51) | Lactacystin, Bortezomib | Histology, protein expression |

| Bone marrow (52) | Bortezomib | Histology, TGF-β1 levels |

| Pulmonary (53) | Bortezomib | Histology, protein expression, TGF-β1 levels |

Definition of abbreviations: PSI = N-benzyloxy-carbonyl-Ile-Glu (O-t-Bu)-Ala-leucinal; TGF = transforming growth factor.

FIBROSIS PATHWAYS: PROTEASOME-REGULATED MECHANISMS

The mechanism(s) by which proteasomal inhibition might protect against injury/fibrosis are not known. Previous work suggests that proteasomal inhibition decreases expression of extracellular matrix proteins and metalloproteinases (50). Subsequently, it was shown that TGF-β1–induced collagen 1 and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 were inhibited by both bortezomib and MG-132 (55). Furthermore, proteasomal inhibition does not inhibit Smad phosphorylation (54) or nuclear translocation, suggesting that proteasomal inhibition manifests its effects in fibroblasts through a Smad-independent pathway. One hypothesis is raised by the observation that inhibiting the phosphorylation of c-Jun induced by proteasomal inhibition reversed its antifibrotic effects in dermal fibroblasts (55). Alternatively, multiple proteasomal inhibitors have been reported to increase the levels of PPAR-γ (34), which antagonizes TGF-β1 signaling in part by inhibiting the binding of R-smads with cognate binding sequences in TGF-β–responsive promoters (56).

In contrast to its effects on TGF-β1 signaling, other investigators have proposed that proteasomal inhibition might limit TGF-β1 expression (53). In the mouse thrombopoietin myelofibrosis model, both plasma and marrow TGF-β1 levels were increased compared with control mice. Treatment with bortezomib, however, reduced TGF-β1 expression in a dose-dependent fashion. The authors did not report the mechanism by which this occurred, but it is well established that TGF-β1 induces its own expression in an autocrine fashion (12).

Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) play a critical role in the development and maintenance of liver fibrosis, and serve as the primary cellular source of matrix components in chronic liver disease. Bortezomib and MG-132 were shown to induce apoptosis of these cells, potentially explaining the observed protection against liver fibrogenesis. Activated HSC survival was dependent upon the prosurvival gene, A1, an antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family member, as silencing RNA (siRNA) targeted knockdown of A1-induced HSC apoptosis (52).

The pathobiology of usual interstitial pneumonia, the pathologic finding in interstitial pulmonary fibrosis, includes accumulation of myofibroblasts in fibroblastic foci (57). Studies using lung tissue from patients with IPF have shown that, despite increased apoptosis in alveolar epithelial cells, fibroblasts/myofibroblasts may be resistant to apoptosis (58, 59). Similarly mesenchymal cells from patients with persistent ALI, which shares similar fibroproliferative features with IPF, have been found to have activation of survival signaling pathways and an antiapoptotic phenotype (60). These studies suggest that induction of fibroblast/myofibroblast apoptosis could provide an appealing target in IPF and ALI/ARDS, similar to proteasomal inhibition targeting HSCs in liver fibrosis.

Proteasomal inhibitors might also prevent the degradation of Smad repressors, thereby attenuating TGF-β1–mediated signaling. For example, the E3 ubiquitin ligase, Arkadia, targets Smad7, SnoN, and c-Ski for degradation. SnoN and Ski are also targeted by the E3 ubiquitin ligase, Smurf2. All three of these proteins are known to attenuate TGF-β1 signaling (46–48, 61). Inhibiting their degradation would be predicted to attenuate fibrogenesis (13, 61).

In the treatment of multiple myeloma, bortezomib is thought to act in part by inhibiting NF-κB activation (62). NF-κB consists of two subunits of 50 and 65 kD, and is maintained in cytoplasm, where it binds to an inhibitory protein, IκB. During NF-κB activation, the phosphorylated IκB is polyubiquitinated and subsequently degraded by the proteasome. Thus, proteasomal inhibition prevents IkB degradation and results in diminished NF-κB activation. It has been reported that NF-κB activation in monocytes can induce TGF-β1 production via IL-1 in an autocrine fashion (63). This would predict decreased TGF-β1 expression in the presence of proteasomal inhibition. Alternatively, NF-κB activation has also been reported to inhibit TGF-β1 signaling by the induction of Smad7 (64). It is unclear what role modulation of NF-κB activity plays in mediating the antifibrotic effects of proteasomal inhibition.

THERAPEUTIC PROTEASOMAL INHIBITION

In a phase 3 trial comparing bortezomib with dexamethasone for the treatment of multiple myeloma, bortezomib was superior in time to disease progression, the primary endpoint (65). In the same study, there was a 44% incidence of serious adverse events (SAEs) (defined as an event that results in death, significant disability, or an important medical event) with bortezomib treatment, which was similar to a 43% incidence of SAEs with dexamethasone (Table 3) (65). The most common SAE that led to discontinuation of bortezomib was peripheral neuropathy (8%). The incidence of severe neutropenia with bortezomib was 12%, but bortezomib had to be stopped in less than 1% of patients due to severe neutropenia. No pulmonary toxicities were reported in these studies. The results of this trial led to the approval of bortezomib by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Bortezomib has also been approved for the treatment of mantle cell lymphoma.

TABLE 3.

ADVERSE EVENTS OF BORTEZOMIB*

| Event | Frequency (%) |

|---|---|

| Diarrhea | 57 |

| Nausea | 57 |

| Fatigue | 42 |

| Constipation | 42 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 36 |

| Vomiting | 35 |

| Pyrexia | 35 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 35 |

| Anemia | 26 |

| Headache | 26 |

| Anorexia | 26 |

| Cough | 21 |

| Paresthesia | 21 |

| Dyspnea | 20 |

| Neutropenia | 19 |

| Rash | 18 |

| Insomnia | 18 |

| Abdominal pain | 16 |

| Bone pain | 16 |

| Pain in limb | 15 |

| Muscle cramps | 12 |

Data used by permission from Reference 65.

There are no data on the use of bortezomib in human fibrosis. There are reports, however, on the efficacy of bortezomib in the treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease (66, 67). In animal models, inhibition of TGF-β1 signaling has been shown to decrease the severity of chronic graft-versus-host disease and the severity of bronchiolitis obliterans after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (24, 68).

Fibroproliferative ARDS and most fibrotic lung diseases, such as IPF, are associated with dismal outcome. Anti-inflammatory therapies, immunosuppressive cytokines, and anticytokines have been ineffective, and are often associated with significant side effects. There is accumulating evidence from in vitro and animal studies demonstrating the therapeutic potential of proteasomal inhibition for tissue fibrosis. Given the absence of proven effective therapies for pulmonary fibrosis, proteasomal inhibition may provide a novel and attractive target in this devastating process. Enthusiasm for this approach may be tempered by reports of patients who developed pulmonary toxicity after bortezomib administration (69) on a twice-weekly basis. Most of these patients were in Japan, and were administered bortezomib before it had received approval there. Implementation of therapeutic guidelines has led to a 10-fold reduction in incidence of pulmonary complications in two different studies (70), including a postmarketing surveillance cohort of 666 patients (71). Based in part on these latter studies, bortezomib was approved in Japan in 2006. Although there are sporadic case reports of bortezomib-induced pulmonary toxicity from elsewhere (72, 73), there are no reports suggesting the high rate of bortezomib-induced pulmonary toxicity seen in Japan, and pulmonary toxicity was not reported in the pivotal U.S. phase 2 study (74).

CONCLUSIONS

In this review, we highlight the effect of proteasomal inhibition on various animal models of tissue fibrosis, and mechanisms by which it may regulate TGF-β1 expression and signaling. There are no effective therapies for fibroproliferative ARDS or IPF, and proteasomal inhibition may provide a novel target in these devastating diseases.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant 5P01HL071643-05, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute/National Center for Research Resources grants 1K12RR017707-02 and M01 RR-00048, and by the American Lung Association, Northwestern Memorial Foundation.

Conflict of Interest Statement: C.H.W. has received funding from noncommercial entity, the National Institutes of Health ($10,001–$50,000). G.R.S.B. and G.M.M. do not have a financial relationship with a commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript. M.J. has received funding from noncommercial entity, the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation ($50,001–$100,000).

References

- 1.Martin C, Papazian L, Payan MJ, Saux P, Gouin F. Pulmonary fibrosis correlates with outcome in adult respiratory distress syndrome: a study in mechanically ventilated patients. Chest 1995;107:196–200. (see comments). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Daniels CE, Wilkes MC, Edens M, Kottom TJ, Murphy SJ, Limper AH, Leof EB. Imatinib mesylate inhibits the profibrogenic activity of TGF-beta and prevents bleomycin-mediated lung fibrosis. J Clin Invest 2004;114:1308–1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bonniaud P, Margetts PJ, Ask K, Flanders K, Gauldie J, Kolb M. TGF-beta and Smad3 signaling link inflammation to chronic fibrogenesis. J Immunol 2005;175:5390–5395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomashefski JF Jr. Pulmonary pathology of acute respiratory distress syndrome. Clin Chest Med 2000;21:435–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hardie WD, Glasser SW, Hagood JS. Emerging concepts in the pathogenesis of lung fibrosis. Am J Pathol 2009;175:3–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Budinger GR, Mutlu GM, Eisenbart J, Fuller AC, Bellmeyer AA, Baker CM, Wilson M, Ridge K, Barrett TA, Lee VY, et al. Proapoptotic Bid is required for pulmonary fibrosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:4604–4609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sheppard D. Transforming growth factor β: a central modulator of pulmonary and airway inflammation and fibrosis. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2006;3:413–417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Selman M, King TE, Pardo A. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: prevailing and evolving hypotheses about its pathogenesis and implications for therapy. Ann Intern Med 2001;134:136–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sato Y, Tsuboi R, Lyons R, Moses H, Rifkin DB. Characterization of the activation of latent TGF-beta by co-cultures of endothelial cells and pericytes or smooth muscle cells: a self-regulating system. J Cell Biol 1990;111:757–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barcellos-Hoff MH, Dix TA. Redox-mediated activation of latent transforming growth factor-beta 1. Mol Endocrinol 1996;10:1077–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Barcellos-Hoff MH, Derynck R, Tsang ML, Weatherbee JA. Transforming growth factor-beta activation in irradiated murine mammary gland. J Clin Invest 1994;93:892–899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Crawford SE, Stellmach V, Murphy-Ullrich JE, Ribeiro SM, Lawler J, Hynes RO, Boivin GP, Bouck N. Thrombospondin-1 is a major activator of TGF-beta1 in vivo. Cell 1998;93:1159–1170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Munger JS, Huang X, Kawakatsu H, Griffiths MJ, Dalton SL, Wu J, Pittet JF, Kaminski N, Garat C, Matthay MA, et al. The integrin alpha v beta 6 binds and activates latent TGF beta 1: a mechanism for regulating pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Cell 1999;96:319–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bonniaud P, Margetts PJ, Kolb M, Schroeder JA, Kapoun AM, Damm D, Murphy A, Chakravarty S, Dugar S, Higgins L, et al. Progressive transforming growth factor β1–induced lung fibrosis is blocked by an orally active ALK5 kinase inhibitor. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:889–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature 2003;425:577–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kavsak P, Rasmussen RK, Causing CG, Bonni S, Zhu H, Thomsen GH, Wrana JL. Smad7 binds to Smurf2 to form an E3 ubiquitin ligase that targets the TGF beta receptor for degradation. Mol Cell 2000;6:1365–1375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ghosh AK, Bhattacharyya S, Lakos G, Chen SJ, Mori Y, Varga J. Disruption of transforming growth factor beta signaling and profibrotic responses in normal skin fibroblasts by peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma. Arthritis Rheum 2004;50:1305–1318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deheuninck J, Luo K. Ski and SnoN, potent negative regulators of TGF-beta signaling. Cell Res 2009;19:47–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Varga J, Jimenez SA. Stimulation of normal human fibroblast collagen production and processing by transforming growth factor–beta. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1986;138:974–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang K, Rekhter MD, Gordon D, Phan SH. Myofibroblasts and their role in lung collagen gene expression during pulmonary fibrosis: a combined immunohistochemical and in situ hybridization study. Am J Pathol 1994;145:114–125. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scotton CJ, Chambers RC. Molecular targets in pulmonary fibrosis: the myofibroblast in focus. Chest 2007;132:1311–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kim KK, Kugler MC, Wolters PJ, Robillard L, Galvez MG, Brumwell AN, Sheppard D, Chapman HA. Alveolar epithelial cell mesenchymal transition develops in vivo during pulmonary fibrosis and is regulated by the extracellular matrix. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2006;103:13180–13185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Puthawala K, Hadjiangelis N, Jacoby SC, Bayongan E, Zhao Z, Yang Z, Devitt ML, Horan GS, Weinreb PH, Lukashev ME, et al. Inhibition of integrin αvβ6, an activator of latent transforming growth factor–β, prevents radiation-induced lung fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:82–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Schmierer B, Hill CS. TGFbeta-Smad signal transduction: molecular specificity and functional flexibility. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2007;8:970–982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kapoun AM, Gaspar NJ, Wang Y, Damm D, Liu YW, O'Young G, Quon D, Lam A, Munson K, Tran TT, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta receptor type 1 (TGFβRI) kinase activity but not p38 activation is required for TGFβRI-induced myofibroblast differentiation and profibrotic gene expression. Mol Pharmacol 2006;70:518–531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramirez AM, Shen Z, Ritzenthaler JD, Roman J. Myofibroblast transdifferentiation in obliterative bronchiolitis: TGF-beta signaling through Smad3-dependent and -independent pathways. Am J Transplant 2006;6:2080–2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu Y, Peng J, Feng D, Chu L, Li X, Jin Z, Lin Z, Zeng Q. Role of extracellular signal-regulated kinase, p38 kinase, and activator protein–1 in transforming growth factor–beta1–induced alpha smooth muscle actin expression in human fetal lung fibroblasts in vitro. Lung 2006;184:33–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith PC, Caceres M, Martinez J. Induction of the myofibroblastic phenotype in human gingival fibroblasts by transforming growth factor-beta1: role of Rhoa-rock and c-Jun N-terminal kinase signaling pathways. J Periodontal Res 2006;41:418–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hashimoto S, Gon Y, Takeshita I, Matsumoto K, Maruoka S, Horie T. Transforming growth factor–β1 induces phenotypic modulation of human lung fibroblasts to myofibroblast through a c-Jun–NH2-terminal kinase–dependent pathway. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:152–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Aono Y, Nishioka Y, Inayama M, Ugai M, Kishi J, Uehara H, Izumi K, Sone S. Imatinib as a novel antifibrotic agent in bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis in mice. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;171:1279–1285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vittal R, Zhang H, Han MK, Moore BB, Horowitz JC, Thannickal VJ. Effects of the protein kinase inhibitor, imatinib mesylate, on epithelial/mesenchymal phenotypes: implications for treatment of fibrotic diseases. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2007;321:35–44. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.Chen H, He YW, Liu WQ, Zhang JH. Rosiglitazone prevents murine hepatic fibrosis induced by Schistosoma japonicum. World J Gastroenterol 2008;14:2905–2911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burgess HA, Daugherty LE, Thatcher TH, Lakatos HF, Ray DM, Redonnet M, Phipps RP, Sime PJ. PPARgamma agonists inhibit TGF-beta induced pulmonary myofibroblast differentiation and collagen production: implications for therapy of lung fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2005;288:L1146–L1153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Milam JE, Keshamouni VG, Phan SH, Hu B, Gangireddy SR, Hogaboam CM, Standiford TJ, Thannickal VJ, Reddy RC. PPAR-gamma agonists inhibit profibrotic phenotypes in human lung fibroblasts and bleomycin-induced pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2008;294:L891–L901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hauser S, Adelmant G, Sarraf P, Wright HM, Mueller E, Spiegelman BM. Degradation of the peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma is linked to ligand-dependent activation. J Biol Chem 2000;275:18527–18533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ciehanover A, Hod Y, Hershko A. A heat-stable polypeptide component of an ATP-dependent proteolytic system from reticulocytes. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1978;81:1100–1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ciechanover A, Iwai K. The ubiquitin system: from basic mechanisms to the patient bed. IUBMB Life 2004;56:193–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Reinstein E, Ciechanover A. Narrative review: protein degradation and human diseases: the ubiquitin connection. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:676–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Glickman MH, Adir N. The proteasome and the delicate balance between destruction and rescue. PLoS Biol 2004;2:E13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sixt SU, Dahlmann B. Extracellular, circulating proteasomes and ubiquitin—incidence and relevance. Biochim Biophys Acta 2008;1782:817–823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sixt SU, Beiderlinden M, Jennissen HP, Peters J. Extracellular proteasome in the human alveolar space: a new housekeeping enzyme? Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2007;292:L1280–L1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sixt SU, Adamzik M, Spyrka D, Saul B, Hakenbeck J, Wohlschlaeger J, Costabel U, Kloss A, Giesebrecht J, Dahlmann B, et al. Alveolar extracellular 20S proteasome in patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:1098–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Egerer K, Kuckelkorn U, Rudolph PE, Ruckert JC, Dorner T, Burmester GR, Kloetzel PM, Feist E. Circulating proteasomes are markers of cell damage and immunologic activity in autoimmune diseases. J Rheumatol 2002;29:2045–2052. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elliott PJ, Zollner TM, Boehncke WH. Proteasome inhibition: a new anti-inflammatory strategy. J Mol Med 2003;81:235–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Borissenko L, Groll M. 20S proteasome and its inhibitors: crystallographic knowledge for drug development. Chem Rev 2007;107:687–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Groll M, Huber R, Moroder L. The persisting challenge of selective and specific proteasome inhibition. J Pept Sci 2009;15:58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Inoue Y, Imamura T. Regulation of TGF-beta family signaling by E3 ubiquitin ligases. Cancer Sci 2008;99:2107–2112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Levy L, Howell M, Das D, Harkin S, Episkopou V, Hill CS. Arkadia activates Smad3/Smad4-dependent transcription by triggering signal-induced SnoN degradation. Mol Cell Biol 2007;27:6068–6083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nagano Y, Mavrakis KJ, Lee KL, Fujii T, Koinuma D, Sase H, Yuki K, Isogaya K, Saitoh M, Imamura T, et al. Arkadia induces degradation of SnoN and c-Ski to enhance transforming growth factor-beta signaling. J Biol Chem 2007;282:20492–20501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tashiro K, Tamada S, Kuwabara N, Komiya T, Takekida K, Asai T, Iwao H, Sugimura K, Matsumura Y, Takaoka M, et al. Attenuation of renal fibrosis by proteasome inhibition in rat obstructive nephropathy: possible role of nuclear factor kappaB. Int J Mol Med 2003;12:587–592. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meiners S, Hocher B, Weller A, Laule M, Stangl V, Guenther C, Godes M, Mrozikiewicz A, Baumann G, Stangl K. Downregulation of matrix metalloproteinases and collagens and suppression of cardiac fibrosis by inhibition of the proteasome. Hypertension 2004;44:471–477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pan X, Hussain FN, Iqbal J, Feuerman MH, Hussain MM. Inhibiting proteasomal degradation of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein prevents CCL4-induced steatosis. J Biol Chem 2007;282:17078–17089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Anan A, Baskin-Bey ES, Bronk SF, Werneburg NW, Shah VH, Gores GJ. Proteasome inhibition induces hepatic stellate cell apoptosis. Hepatology 2006;43:335–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wagner-Ballon O, Pisani DF, Gastinne T, Tulliez M, Chaligne R, Lacout C, Aurade F, Villeval JL, Gonin P, Vainchenker W, et al. Proteasome inhibitor bortezomib impairs both myelofibrosis and osteosclerosis induced by high thrombopoietin levels in mice. Blood 2007;110:345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fineschi S, Bongiovanni M, Donati Y, Djaafar S, Naso F, Goffin L, Argiroffo CB, Pache JC, Dayer JM, Ferrari-Lacraz S, et al. In vivo investigations on anti-fibrotic potential of proteasome inhibition in lung and skin fibrosis. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2008;39:458–465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fineschi S, Reith W, Guerne PA, Dayer JM, Chizzolini C. Proteasome blockade exerts an antifibrotic activity by coordinately down-regulating type I collagen and tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase–1 and up-regulating metalloproteinase-1 production in human dermal fibroblasts. FASEB J 2006;20:562–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ghosh AK, Bhattacharyya S, Wei J, Kim S, Barak Y, Mori Y, Varga J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-{gamma} abrogates Smad-dependent collagen stimulation by targeting the p300 transcriptional coactivator. FASEB J 2009;23:2968–2977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Horowitz JC, Lee DY, Waghray M, Keshamouni VG, Thomas PE, Zhang H, Cui Z, Thannickal VJ. Activation of the pro-survival phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase/Akt pathway by transforming growth factor–beta1 in mesenchymal cells is mediated by p38 MAPK-dependent induction of an autocrine growth factor. J Biol Chem 2004;279:1359–1367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Horowitz JC, Cui Z, Moore TA, Meier TR, Reddy RC, Toews GB, Standiford TJ, Thannickal VJ. Constitutive activation of prosurvival signaling in alveolar mesenchymal cells isolated from patients with nonresolving acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 2006;290:L415–L425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lappi-Blanco E, Soini Y, Paakko P. Apoptotic activity is increased in the newly formed fibromyxoid connective tissue in bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia. Lung 1999;177:367–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tan R, He W, Lin X, Kiss LP, Liu Y. Smad ubiquitination regulatory factor–2 in the fibrotic kidney: regulation, target specificity, and functional implication. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2008;294:F1076–F1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ocio EM, Mateos MV, Maiso P, Pandiella A, San-Miguel JF. New drugs in multiple myeloma: mechanisms of action and phase I/II clinical findings. Lancet Oncol 2008;9:1157–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rameshwar P, Narayanan R, Qian J, Denny TN, Colon C, Gascon P. NF-kappa B as a central mediator in the induction of TGF-beta in monocytes from patients with idiopathic myelofibrosis: an inflammatory response beyond the realm of homeostasis. J Immunol 2000;165:2271–2277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bitzer M, von Gersdorff G, Liang D, Dominguez-Rosales A, Beg AA, Rojkind M, Bottinger EP. A mechanism of suppression of TGF-beta/Smad signaling by NF-kappa B/RelA. Genes Dev 2000;14:187–197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Richardson PG, Sonneveld P, Schuster MW, Irwin D, Stadtmauer EA, Facon T, Harousseau JL, Ben-Yehuda D, Lonial S, Goldschmidt H, et al. Bortezomib or high-dose dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med 2005;352:2487–2498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mateos-Mazon J, Perez-Simon JA, Lopez O, Hernandez E, Etxebarria J, San Miguel JF. Use of bortezomib in the management of chronic graft-versus-host disease among multiple myeloma patients relapsing after allogeneic transplantation. Haematologica 2007;92:1295–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.El-Cheikh J, Michallet M, Nagler A, de Lavallade H, Nicolini FE, Shimoni A, Faucher C, Sobh M, Revesz D, Hardan I, et al. High response rate and improved graft-versus-host disease following bortezomib as salvage therapy after reduced intensity conditioning allogeneic stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Haematologica 2008;93:455–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Banovic T, MacDonald KP, Morris ES, Rowe V, Kuns R, Don A, Kelly J, Ledbetter S, Clouston AD, Hill GR. TGF-beta in allogeneic stem cell transplantation: friend or foe? Blood 2005;106:2206–2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Miyakoshi S, Kami M, Yuji K, Matsumura T, Takatoku M, Sasaki M, Narimatsu H, Fujii T, Kawabata M, Taniguchi S, et al. Severe pulmonary complications in Japanese patients after bortezomib treatment for refractory multiple myeloma. Blood 2006;107:3492–3494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ogawa Y, Tobinai K, Ogura M, Ando K, Tsuchiya T, Kobayashi Y, Watanabe T, Maruyama D, Morishima Y, Kagami Y, et al. Phase I and II pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic study of the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib in Japanese patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma. Cancer Sci 2008;99:140–144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Narimatsu H, Hori A, Matsumura T, Kodama Y, Takita M, Kishi Y, Hamaki T, Yuji K, Tanaka Y, Komatsu T, et al. Cooperative relationship between pharmaceutical companies, academia, and media explains sharp decrease in frequency of pulmonary complications after bortezomib in Japan. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:5820–5823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Ohri A, Arena FP. Severe pulmonary complications in African American patient after bortezomib therapy. Am J Ther 2006;13:553–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Boyer JE, Batra RB, Ascensao JL, Schechter GP. Severe pulmonary complication after bortezomib treatment for multiple myeloma. Blood 2006;108:1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Richardson PG, Barlogie B, Berenson J, Singhal S, Jagannath S, Irwin D, Rajkumar SV, Srkalovic G, Alsina M, Alexanian R, et al. A phase 2 study of bortezomib in relapsed, refractory myeloma. N Engl J Med 2003;348:2609–2617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]