Abstract

While arteriosclerotic disease and hypertension, with or without diabetes, are the most common causes of stroke, viruses may also produce transient ischemic attacks and stroke. The three most-well studied viruses in this respect are varicella zoster virus (VZV), cytomegalovirus (CMV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), all of which are potentially treatable with antiviral agents. Productive VZV infection in cerebral arteries after reactivation (zoster) or primary infection (varicella) has been documented as a cause of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke, aneurysms with subarachnoid and intracerebral hemorrhage, arterial ectasia and as a co-factor in cerebral arterial dissection. CMV has been suggested to play a role in the pathogenesis of arteriosclerotic plaques in cerebral arteries. HIV patients have a small but definite increased incidence of stroke which may be due to either HIV infection or opportunistic VZV infection in these immunocompromised individuals. Importantly, many described cases of vasculopathy in HIV-infected patients were not studied for the presence of anti-VZV IgG antibody in CSF, a sensitive indicator of VZV vasculopathy. Unlike the well-documented role of VZV in vasculopathy, evidence for a causal link between HIV or CMV and stroke remains indirect and awaits further studies demonstrating productive HIV and CMV infection of cerebral arteries in stroke patients. Nonetheless, all three viruses have been implicated in stroke and should be considered in clinical diagnoses.

Keywords: Virus vasculopathy, VZV, HIV, CMV

VIRAL CAUSES OF STROKE

Stroke is a common cause of mortality and morbidity worldwide [1]. While established risk factors, such as hypertension, diabetes, obesity and hypercholesterolemia have been identified and are targets for stroke prevention, viral infections have also emerged as risk factors for stroke. Identification of viruses that directly cause stroke, as evidenced by direct invasion of cerebral arteries corresponding to areas of infarction, would provide therapeutic targets for stroke prevention. Varicella zoster virus (VZV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) have all been associated with stroke. However, VZV is the only virus that has been shown to directly invade cerebral arteries and produce vasculopathy [2]. Herein, we review evidence regarding the association of these three viruses with stroke.

VZV VASCULOPATHY

VZV (human herpesvirus 3) is a ubiquitous, exclusively human DNA virus. Primary infection occurs via respiratory aerosols or contact with vesicles from an infected individual and results in the characteristic disseminated rash of varicella (chickenpox). Subsequently, VZV becomes latent in ganglionic neurons in cranial nerve ganglia, dorsal root ganglia and autonomic ganglia along the entire neuraxis [3–8]. A decline in VZV specific cell-mediated immunity in elderly and immunocompromised individuals results in virus reactivation in one or more ganglia [9–12]. VZV reactivation most commonly manifests as herpes zoster (shingles), frequently complicated by postherpetic neuralgia. Less often, VZV reactivation leads to retinal necrosis [13], myelopathy [14] and vasculopathy [15] or even chronic radicular pain without rash, also known as zoster sine herpete [16,17].

The incidence and prevalence of stroke caused by VZV is unknown, although estimates in children reveal that varicella accounts for 7 to 31% of arterial ischemic stroke [18,19], with 1 in 15,000 cases of varicella associated with stroke [18]. In transient cerebral arteriopathy of childhood, stroke is preceded by varicella in 44% of cases [20]. In adults, VZV vasculopathy is more common in immunocompromised than in immunocompetent individuals. In immunocompromised adults, VZV infection of the central nervous system (CNS) was detected in 1.5 to 4.4% of autopsy cases [21–23]. In postmortem studies of HIV-infected individuals, VZV vasculopathy occurred more frequently late in the course of infection when there was significant CD4+ depletion [24,25].

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DIAGNOSIS

In adults, the typical clinical presentation of stroke caused by VZV is the occurrence of ophthalmic-distribution herpes zoster followed by acute contralateral hemiplegia weeks to months later [26] or, in children, varicella followed by acute hemiplegia. However, since VZV can affect both large and small arteries resulting in ischemic or hemorrhagic strokes, clinical presentations may vary and include headache, mental status changes, aphasia, ataxia, hemisensory loss, hemianopia and even monocular visual loss [27,28]. Many patients experience transient ischemic attacks with protracted neurological symptoms and signs. Importantly, 37% of VZV vasculopathy cases do not have the characteristic varicella or zoster rash [15]. Furthermore, if rash occurred months before the stroke, it may not regarded as related. Thus, it is imperative that the diagnosis of VZV vasculopathy be considered in all strokes of unclear etiology, particularly in HIV-positive and other immunocompromised patients.

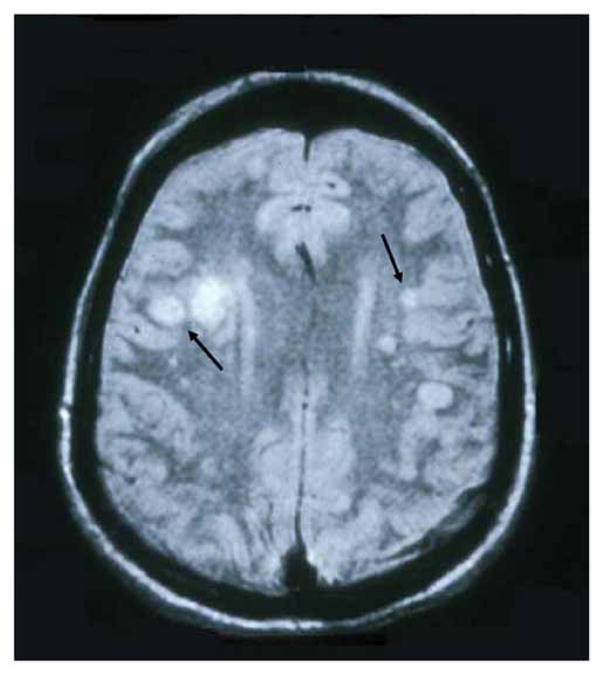

Brain imaging of patients with VZV vasculopathy reveals ischemic or hemorrhagic infarction in virtually all cases. An analysis of 30 cases of virologically confirmed VZV vasculopathy revealed changes in all but one subject who had only posterior ciliary artery involvement [15,29]. MRI typically shows superficial and deep-seated lesions, in both gray and white matter, and particularly at gray-white matter junctions (Fig. (1)), providing a clue to the cause of disease. Lesions may be bland or hemorrhagic and may enhance. While gray-white matter lesions are often seen in patients with other disorders such as metastatic carcinoma and embolic disease, VZV vasculopathy should be included in the differential diagnosis of patients with gray-white matter junction lesions.

Fig. 1. MRI scan of a patient with VZV multifocal vasculopathy.

Proton-density brain MRI scan shows multiple areas of infarction in both hemispheres, particularly involving white matter. Arrows point to gray-white matter junction lesions. Reproduced from Gilden et al. [29] with permission from the Journal of NeuroVirology.

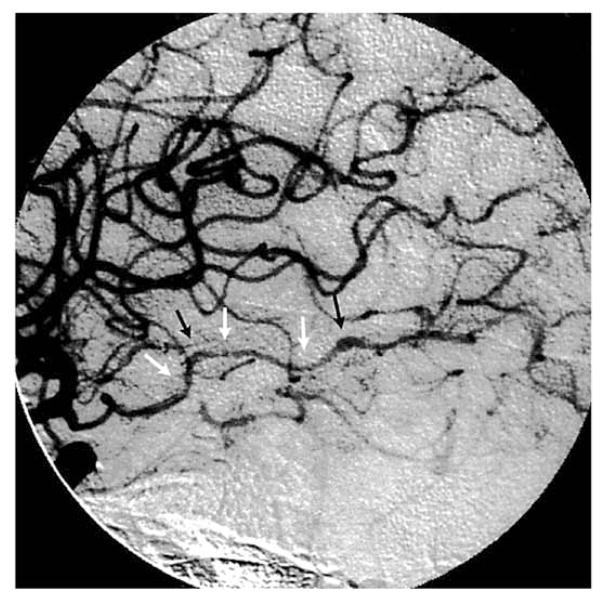

Typical angiographic changes include segmental constriction, often with poststenotic dilatation (Fig. (2)). In addition to arterial occlusion, aneurysm and hemorrhage can also develop. In the largest series (30 patients) reported to date with virologically verified VZV vasculopathy, 23 patients underwent vascular studies (conventional angiography or magnetic resonance angiography) and 16 (70%) of those showed vascular abnormalities [15]. Brain imaging and vascular studies revealed mixed large and small artery involvement in 15 (50%), pure small artery involvement in 11 (37%) and pure large artery disease in 4 (13%) patients. While the presence of stenosis or occlusion is helpful in diagnosing VZV vasculopathy, a negative angiogram does not exclude the diagnosis, most likely because disease in small arteries is not detected as readily as in large arteries. Overall, mixed large and small artery disease is seen more often than pure small artery disease, while pure large artery disease occurs least often.

Fig. 2. Cerebral angiogram from a patient with VZV vasculopathy.

Cerebral angiogram shows focal areas of stenosis (white arrows) and poststenotic dilatation (black arrows) involving the right posterior cerebral artery. Reproduced from Russman et al. [30] with permission from the American Medical Association.

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) abnormalities are common. A modest pleocytosis, usually less than 100 cells and predominantly mononuclear, is seen in about two-thirds of patients with VZV vasculopathy [15], and many patients also have red blood cells in their CSF. CSF protein is usually elevated, while glucose is normal. Oligoclonal bands are frequently present and have been shown to be VZV-specific IgG [31].

When a clinical diagnosis of VZV vasculopathy is suspected and supported by single or multiple characteristic lesions on MRI or CT, virological confirmation is required. The diagnostic value of detecting anti-VZV immunoglobulin (Ig) G antibody in CSF is greater than that of detecting VZV DNA [32]. In the largest series of virologically verified VZV vasculopathy from multiple institutions in the United States, Europe and Japan, 28 of 30 (93%) patients with VZV vasculopathy had anti-VZV IgG in the CSF compared to only 30% with VZV DNA in CSF [15]. Although a positive PCR for VZV DNA in CSF is helpful, a negative PCR does not exclude the diagnosis; only negative results in both VZV PCR and anti-VZV IgG antibody tests in CSF can reliably exclude the diagnosis of VZV vasculopathy.

Importantly, many of the same symptoms, signs, CSF, imaging and arteriographic abnormalities that occur in VZV vasculopathy are seen in primary angiitis of the nervous system and the granulomatous angiitides such as CNS sarcoidosis, neurosyphilis, and tuberculous and fungal infections of the nervous system. Thus, the workup of all patients with granulomatous or other CNS angiitides should include CSF analysis for both VZV DNA and anti-VZV IgG antibody.

Because VZV vasculopathy is caused by productive viral infection in arteries, all patients are typically treated with intravenous acyclovir based on Category 3 evidence (opinions of respected authorities based on clinical experience, descriptive studies or reports of expert committees). In the study of 30 patients [15], patients treated with acyclovir alone improved or stabilized, compared to 75% who improved or stabilized when treated with both acyclovir and steroids. Because patients received different treatment regimens at different institutions in an uncontrolled setting, the determination of optimal dose, duration of antiviral treatment and benefit of concurrent steroid therapy awaits prospective studies with larger case numbers.

When the diagnosis of VZV vasculopathy is being considered, and the clinician is awaiting CSF studies that detect anti-VZV IgG antibody or VZV DNA in CSF to confirm the diagnosis, it is advisable to begin treatment immediately with intravenous acyclovir, 10–15 mg/kg three times daily for a minimum of 14 days. Since there is often an inflammatory response in infected cerebral arteries, we also give oral prednisone, 1 mg/kg daily for 5 days; no taper is needed. Importantly, we never treat patients with VZV vasculopathy with steroids for more than 1 week since long-term treatment can potentiate virus infection. Finally, we have encountered multiple patients with VZV vasculopathy who continue to have neurologic symptoms after intravenous acyclovir treatment. Most, but not all of these patients were HIV-positive or had AIDS; one patient was diabetic. In these situations, we have recommended oral valacyclovir, 1 gram three times daily for an additional 1 to 2 months, which resulted in clinical improvement.

PATHOGENESIS

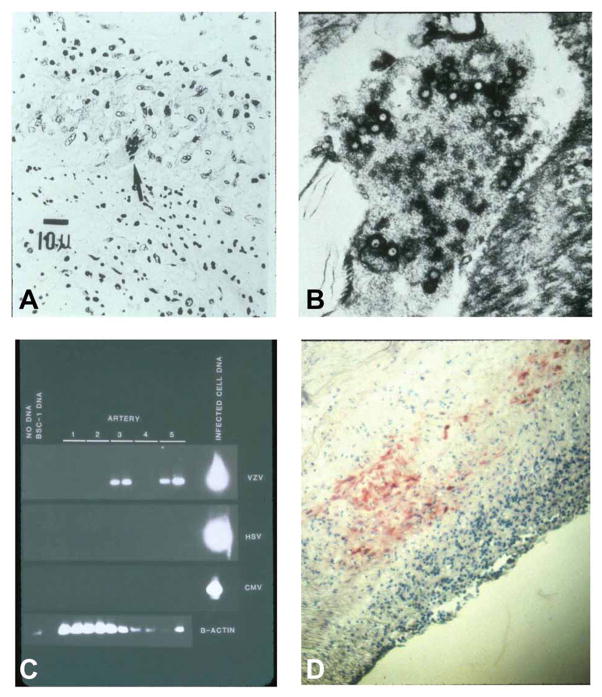

The mechanism by which VZV causes stroke is likely by direct infection of cerebral arteries, leading to thrombosis, necrosis, dissection and aneurysm. Studies in cats have identified afferent fibers from trigeminal and dorsal root ganglia to both intracranial and extracranial blood vessels, thus providing an anatomic pathway for transaxonal spread of virus [33–35]. Pathological and virological analyses of cerebral arteries of patients who died of VZV vasculopathy have revealed herpes virions [36,37], VZV antigen and VZV DNA [2,23,25,38–41] in the walls of cerebral arteries (Fig. (3)).

Fig. 3. Pathological and virological findings in the arteries of patients who died from VZV vasculopathy.

(A) A cerebral artery with multinucleated giant cells (arrow). (B) Multiple herpesvirions within a cerebral artery. (C) VZV DNA in the posterior cerebral artery (lane 3) and basilar artery (lane 5). (D) VZV antigen (red) in the media of a cerebral artery. Reproduced from Gilden et al. [42] with permission from the Lancet Neurology.

A potential cofactor that has emerged in VZV-associated ischemic stroke is the role of transient autoantibodies to phospholipids and coagulation proteins during or after varicella [43,44]. Both the presence of lupus anticoagulant and protein S deficiency were found in a child with disseminated intravascular coagulation during varicella [45]. Another report described a child with varicella who had protein S deficiency along with the presence of anti-protein S antibody and hypercoagulability, supporting a pathogenic role for antibody [46]. Recently, Massano et al. [47] described an adult with varicella who developed stroke and multiple peripheral thrombotic events associated with transient protein S deficiency and transient anticardiolipin and anti-beta 2 glycoprotein antibodies. The role of these autoantibodies in thrombus formation in cerebral arteries during VZV infection requires further study.

Overall, VZV vasculopathy usually manifests as ischemic stroke but can also produce aneurysm, subarachnoid and cerebral hemorrhage, arterial ectasia and carotid dissection. In such patients, the clinician should ask whether there is a history of recent zoster or varicella rash, and if so, should undertake virological analysis for VZV. Because not all patients with VZV vasculopathy have a history of zoster or varicella rash, the CSF of all patients with uni- or multifocal vasculopathy, as well as CNS angiitis of unknown etiology, should be studied for the presence of both VZV DNA and anti-VZV IgG antibody. Rapid and accurate diagnosis can lead to effective antiviral treatment of VZV vasculopathy.

CYTOMEGALOVIRUS (CMV) VASCULOPATHY

Human CMV typically becomes latent early in life in myeloid precursor cells after asymptomatic infection. CMV does not usually cause disease in immunocompetent individuals; however CMV infection in immunosuppressed organ transplant recipients and AIDS patients is a major cause for concern [48]. Since aggressive prophylaxis treatment of heart transplant recipients with ganciclovir and CMV hyperimmune globulin has decreased cardiac allograft vasculopathy, a major cause of transplant failure, CMV has been linked to vascular changes in solid organs after transplantation [49,50]; nevertheless, an association between CMV and vasculopathy in immunocompetent subjects remains unclear. CMV antigen was originally detected in 7 of 26 cell cultures derived from atherosclerotic plaques [51]. Subsequently, the titer of circulating antibody against CMV was found to be higher in subjects undergoing vascular surgery for atherosclerosis than in matched control subjects [52]. Those studies suggested an association between CMV and vascular disease, a hypothesis supported by the finding of CMV DNA in arterial walls within atherosclerotic plaques [53]. Primary tissue cultures containing vascular smooth muscle cells are permissive for CMV infection, during which significant amounts of pro-inflammatory adhesion molecules are synthesized [54,55]. Further, 5-lipoxygenase gene transcription is induced in vascular smooth muscle cells infected with CMV [56]; 5-lipoxgenase initiates synthesis of leukotrienes, which are mediators of cardiovascular disease, from arachidonic acid. Thus, CMV replication in arterial endothelial cells may induce an atherosclerotic environment, restricting blood flow and promoting ischemic stroke. However, correlation between artery wall thickening and CMV is not conclusive [57]. In addition, a prospective study involving >600 apparently healthy men found no correlation between anti-CMV IgG and an increased risk of atherosclerosis [58], and CMV does not induce neointimal hyperplasia [59]. In an organ culture model of CMV infection of human renal arteries, infectious virus was recoverable from supernatants up to 144 days post-infection; endothelial cells were the first to become infected, after which virus penetrated into the media [60]. Overall, circumstantial evidence suggests a mechanism by which abortive or active CMV replication in arterial cells may lead to stenosis, although continued studies are required to demonstrate a direct causal link between CMV arterial infection and stroke.

HIV VASCULOPATHY

HIV infection of humans worldwide has resulted in more deaths than any other infectious disease. Nevertheless, analysis of stroke in adult AIDS patients from the Edinburgh HIV Autopsy Cohort [61] revealed that infarcts in HIV-infected patients are rare in the absence of cerebral non-HIV infection, lymphoma or embolism; in fact, an HIV-associated vasculopathy was found in only 5.5% of all cases studied. Lesions in all cases were characterized by hyaline small-vessel thickening, perivascular space dilatation, and rarefaction with vessel wall mineralization; perivascular inflammatory cell infiltrates were seen in some cases. Later, the incidence of cerebrovascular events and stroke in HIV-infected patients ages 15 to 44 years was found to be 9 to 12% [62]. In another study, which included data from ultrasonography, brain CT, MRI, CSF and blood analysis from 1087 stroke subjects, 6% were found to be infected with HIV [63], compared to an earlier longitudinal neuroradiological study of 68 HIV-positive children that revealed an incidence of stroke at 1.3% per year [64]. Direct association of HIV with stroke was impossible because HIV was not detected in cerebral arteries. Since HIV infection is immunosuppressive, other opportunistic infections, such as VZV must be considered.

Among reports that attribute the sole cause of vasculopathy to HIV is a case study of a 5-year-old boy with AIDS who developed transient vasculopathy that resolved after therapy with only aspirin and HAART; the patient was PCR-negative for multiple viruses including VZV, although no studies were done to detect anti-VZV IgG in CSF [65]. Another case report [66] described a 33-year-old HIV-positive man with rapidly progressive vasculopathy and recurrent strokes, a very high HIV load, and normal CSF. The patient was studied for cryptococcal antigen, syphilis and toxoplasmosis, all of which were negative; after HAART therapy, the patient improved and the HIV load became low. There was no indication that any studies for VZV were performed in this patient. A third instance of successful treatment of HIV-associated vasculopathy with HAART was described in a 49-year-old man [67]. The CSF contained 18 cells, primarily mononuclear, and no testing for Myco-bacteria or fungal infection was found. Although PCR was negative for multiple viruses including VZV, no testing for anti-VZV antibody in CSF was performed. Overall, conclusions about the usefulness of HAART in treating cerebral vasculopathy in HIV-infected patients await additional studies, especially since HIV, unlike VZV, has not yet been shown to be directly involved in cerebral vessels.

An analysis of three HIV-infected patients who developed intracranial aneurysms did not identify an etiologic agent [68]. None of the patients was studied for VZV, which was unfortunate since numerous cases of VZV vasculopathy with aneurysm have been described in adults and children [reviewed in Gilden et al., ref. 42]. Nevertheless, direct involvement of HIV in aneurysm formation has been suggested by monoclonal anti-gp41 antibody staining in the aneurysmal arterial wall in a 6-year-old boy with AIDS [69]. A larger analysis of 67 HIV-infected patients with stroke revealed vasculopathy that was both extracranial or intracranial with and without fusiform aneurysmal dilatation, stenosis and variation in the caliber of vessels; again, none of the HIV-positive stroke group was studied for antibody to VZV [63].

The studies above raise the possibility that stroke in HIV patients may actually represent a VZV vasculopathy for which an adequate evaluation was not performed. For example, Tipping and colleagues [70] described a 27-year-old HIV-infected woman who presented with stroke and a CD4 count of 14 cells/μl and who demonstrated fusiform aneurysmal dilation of the left internal carotid artery and left middle cerebral artery upon imaging. Although VZV vasculopathy, even in the absence of VZV rash, was a likely strong possibility in light of her immunosuppressed state, cerebral artery pathology and the presence of a CSF pleocytosis, the patient’s CSF was not tested for VZV DNA or anti-VZV IgG antibody, nor were her affected cerebral arteries tested for VZV antigen staining [71]. At autopsy, HIV p24 antigen was not found in the affected cerebral arteries. In another example, Kossorotoff and colleagues [72] described a 32-year-old HIV-infected man who presented with stroke and multiple ectasias and focal stenoses of medium and small cerebral arteries with a CSF pleocytosis. His history was remarkable for recurrent herpes zoster. His CSF did not contain VZV DNA, but the more sensitive test to diagnose VZV vasculopathy, i.e., detection of anti-VZV IgG antibody in CSF [32,73], was not carried out. Thus, this too might well have been a VZV vasculopathy in an HIV patient. Overall, HIV patients with stroke should have their CSF tested for both VZV DNA and anti-VZV IgG antibody. If the cause of vasculopathy is still unknown at death, the cerebral arteries should be analyzed for the presence of both VZV DNA and VZV antigen.

There is some indirect evidence that HIV might infect arteries. Premature coronary disease has been reported in HIV patients receiving protease inhibitors [74], leading to the notion that HIV disease might be atherogenic [74,75]. HIV infects specific cell types in humans such as helper T (CD4+) cells, macrophages and dendritic cells. Immunohistochemistry had detected HIV-infected dendritic cells (p24+) in atherosclerotic lesions in aortas of AIDS patients, and considerably more HIV-positive cells were found in the atherosclerotic lesions in the diseased aorta compared to the non-diseased aortic segments [76]. Furthermore, the CXCR3 chemokine receptor, which is important for HIV attachment, was also detected by immunofluorescence and immunohistochemistry in areas associated with atherosclerotic plaques in arterial endothelial and smooth muscle cells. CXCR3-positive astrocytes and cerebellar purkinje cells were also prominent in the CNS of HIV-positive patients [77]. To test the possibility that HIV infects smooth muscle cells which in turn could accelerate vascular disease, Eugenin et al. [78] used confocal fluorescence microscopy with antibodies specific for the HIV p24 protein and smooth muscle α-actin to analyze tissue sections from atherosclerotic plaques of HIV-positive humans; the p24 protein colocalized with smooth muscle α-actin in the smooth muscle layer of arteries with plaque, although non-atherosclerotic arteries of HIV patients, which should not contain p24, were not analyzed.

HIV sequences were detected by in situ hybridization in sections of the intima and media of the anterior descending artery from an individual with HIV-associated coronary arteritis who died of myocardial infarction [79]. Extensive vasculopathy has also been demonstrated in transgenic mice carrying replication-defective HIV provirus [80]. In those mice, affected areas were composed primarily of T cells and occasionally plasma cells, but HIV gene expression was limited in affected areas. Finally, HIV-infected macrophages in transgenic mice were shown to have impaired cholesterol efflux, a condition that is highly atherogenic [81]. Despite all the indirect evidence, an unequivocal association of HIV infection with stroke remains to be demonstrated.

SUMMARY

VZV, CMV and HIV have all been associated with stroke. Yet VZV is the only virus for which there is clear evidence of virus DNA and antigen in cerebral arteries corresponding to areas of ischemia or infarction. Antiviral therapy is indicated in VZV vasculopathy. While HIV and CMV have been found to infect smooth muscle cells in coronary or renal arteries, studies that demonstrate productive HIV or CMV infection of cerebral arteries in areas of ischemia/infarction are still lacking.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by Public Health Service grants AG006127 and AG0329958 from the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Maria Nagel is supported by Public Health Service grant NS007321 from the National Institutes of Health. The authors thank Marina Hoffman for editorial review and Cathy Allen for manuscript preparation.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CMV

Cytomegalovirus

- CNS

Central nervous system

- CSF

Cerebrospinal fluid

- CT

Computerized tomography

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- Ig

Immunoglobulin

- MRI

Magnetic resonance imaging

- VZV

Varicella zoster virus

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

All authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Lloyd-Jones D, Adams R, Carnethon M, De Simone G, Ferguson TB, Flegal K, Ford E, Furie K, Go A, Greenlund K, Haase N, Hailpern S, Ho M, Howard V, Kissela B, Kittner S, Lackland D, Lisabeth L, Marelli A, McDermott M, Meigs J, Mozaffarian D, Nichol G, O’Donnell C, Roger V, Rosamond W, Sacco R, Sorlie P, Stafford R, Steinberger J, Thom T, Wasserthiel-Smoller S, Wong N, Wylie-Rosett J, Hong Y American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics – 2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119:480–486. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.191259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gilden DH, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Wellish M, Hedley-Whyte ET, Rentier B, Mahalingam R. Varicella zoster virus, a cause of waxing and waning vasculitis: The New England Journal of Medicine case 5-1995 revisited. Neurology. 1996;47:1441–1446. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.6.1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hyman RW, Ecker JR, Tenser RB. Varicellazoster virus RNA in human trigeminal ganglia. Lancet. 1983;2:814–816. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)90736-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilden DH, Vafai A, Shtram Y, Becker Y, Devlin M, Wellish M. Varicellazoster virus DNA in human sensory ganglia. Nature. 1983;306:478–480. doi: 10.1038/306478a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilden DH, Rozenman Y, Murray R, Devlin M, Vafai A. Detection of varicellazoster virus nucleic-acid in neurons of normal human thoracic ganglia. Ann Neurol. 1987;22:377–380. doi: 10.1002/ana.410220315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gilden DH, Gesser R, Smith J, Wellish M, LaGuardia JJ, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R. Presence of VZV and HSV-1 DNA in human nodose and celiac ganglia. Virus Genes. 2001;23:145–147. doi: 10.1023/a:1011883919058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mahalingam R, Wellish M, Wolf W, Dueland AN, Cohrs R, Vafai A, Gilden DH. Latent varicella zoster virus DNA in human trigeminal and thoracic ganglia. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:627–631. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199009063231002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaGuardia JJ, Cohrs RJ, Gilden DH. Prevalence of varicellazoster virus DNA in dissociated human trigeminal ganglion neurons and non-neuronal cells. J Virol. 1999;73:8571–8577. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8571-8577.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller AE. Selective decline in cellular immune-response to varicellazoster in the elderly. Neurology. 1980;30:582–587. doi: 10.1212/wnl.30.6.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Berger R, Florent G, Just M. Decrease of the lymphoproliferative response to varicellazoster virus-antigen in the aged. Infect Immun. 1981;32:24–27. doi: 10.1128/iai.32.1.24-27.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hayward AR, Herberger M. Lymphocyte-responses to varicella zoster virus in the eldery. J Clin Immunol. 1987;7:174–178. doi: 10.1007/BF00916011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hayward A, Levin M, Wolf W, Angelova G, Gilden D. Varicellazoster virus specific immunity after herpes zoster. J Infect Dis. 1991;163:873–875. doi: 10.1093/infdis/163.4.873. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Holland GN. The progressive outer retinal necrosis syndrome. Int Ophthalmol. 1994;18:163–165. doi: 10.1007/BF00915966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gilden DH, Beinlich BR, Rubinstien EM, Stommel E, Swenson R, Rubinstein D, Mahalingam R. Varicellazoster virus myelitis: an expanding spectrum. Neurology. 1994;44:1818–1823. doi: 10.1212/wnl.44.10.1818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nagel MA, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, Wellish MC, Forghani F, Schiller A, Safdieh JE, Kamenkovich E, Ostrow LW, Levy M, Greenberg B, Russman AN, Katzan I, Gardner CJ, Häusler M, Nau R, Saraya T, Wada H, Goto H, de Martino M, Ueno M, Brown WD, Terborg C, Gilden DH. The varicella zoster virus vasculopathies: clinical, CSF, imaging and virological features. Neurology. 2008;70:853–860. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000304747.38502.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gilden DH, Dueland AN, Cohrs R, Martin JR, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Mahalingam R. Preherpetic neuralgia. Neurology. 1991;41:1215–1218. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.8.1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gilden DH, Wright RR, Schneck SA, Gwaltney JM, Jr, Mahalingam R. Zoster sine herpete, a clinical variant. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:530–533. doi: 10.1002/ana.410350505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Askalan R, Laughlin S, Mayank S, Chan A, MacGregor D, Andrew M, Curtis R, Meaney B, deVeber G. Chickenpox and stroke in childhood: a study of frequency and causation. Stroke. 2001;32:1257–1262. doi: 10.1161/01.str.32.6.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Amlie-Lefond C, Bernard TJ, Sébire G, Friedman NR, Heyer GL, Lerner NB, DeVeber G, Fullerton HJ International Pediatric Stroke Study Group. Predictors of cerebral arteriopathy in children with arterial ischemic stroke: results of the International Pediatric Stroke Study. Circulation. 2009;119:1417–1423. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.806307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Braun KP, Bulder MM, Chabrier S, Kirkham FJ, Ulterwaal CS, Tardieu M, Sébire G. The course and outcome of unilateral intracranial arteriopathy in 79 children with ischaemic stroke. Brain. 2009;132:544–557. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petito CK, Cho ES, Lemann W, Navia BA, Price RW. Neuropathology of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS): an autopsy review. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1986;45:635–646. doi: 10.1097/00005072-198611000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray F, Mohr M, Rozenberg F, Bélec L, Lescs MC, Dournon E, Sinclair E, Scaravilli F. Varicellazoster virus encephalitis in acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: report of four cases. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 1992;18:502–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.1992.tb00817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gray F, Bélec L, Lescs MC, Chrétien F, Ciardi A, Hassine D, Flament-Saillour M, de Truchis P, Clair B, Scaravilli F. Varicellazoster virus infection of the central nervous system in the acquired immune deficiency syndrome. Brain. 1994;117:987–999. doi: 10.1093/brain/117.5.987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ryder JW, Croen K, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Ostrove JM, Straus SE, Cohn DL. Progressive encephalitis three months after resolution of cutaneous zoster in a patient with AIDS. Ann Neurol. 1986;19:182–188. doi: 10.1002/ana.410190212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Morgello S, Block GA, Price RW, Petito CK. Varicellazoster virus leukoencephalitis and cerebral vasculopathy. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 1988;112:173–177. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reshef E, Greenberg SB, Jankovic J. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus followed by contralateral hemiparesis: report of two cases adn review of literature. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1985;48:122–127. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.48.2.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hall S, Carlin L, Roach ES, McLean WT., Jr Herpes zoster and central retinal artery occlusion. Ann Neurol. 1983;13:217–218. doi: 10.1002/ana.410130226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilden DH, Lipton HL, Wolf JS, Akenbrandt W, Smith JE, Mahalingam R, Forghani B. Two patients with unusual forms of varicellazoster virus vasculopathy. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1500–1503. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gilden DH, Mahalingam R, Cohrs RJ, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Forghani B. The protean manifestations of varicellazoster virus vasculopathy. J Neurovirol. 2002;8:75–79. doi: 10.1080/13550280290167902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Russman AN, Lederman RJ, Calabrese LH, Embi PJ, Forghani B, Gilden DH. Multifocal varicellazoster virus vasculopathy without rash. Arch Neurol. 2003;60:1607–1609. doi: 10.1001/archneur.60.11.1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Burgoon MP, Hammack BN, Owens GP, Maybach AL, Eikelenboom MJ, Gilden DH. Oligoclonal immunoglobulins in cerebrospinal fluid during varicella zoster virus (VZV) vasculopathy are directed against VZV. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:459–563. doi: 10.1002/ana.10685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagel MA, Forghani B, Mahalingam R, Wellish MC, Cohrs RJ, Russman AN, Katzan I, Lin R, Gardner CJ, Gilden DH. The value of detecting anti-VZV antibody in CSF to diagnose VZV vasculopathy. Neurology. 2007;68:1069–1073. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000258549.13334.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mayberg M, Langer RS, Zervas NT, Moskowitz MA. Perivascular meningeal projections from cat trigeminal ganglia: possible pathway for vascular headaches in man. Science. 1981;213:228–230. doi: 10.1126/science.6166046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayberg MR, Zervas NT, Moskowitz MA. Trigeminal projections to supratentorial pial and dural blood vessels in cats demonstrated by horseradish peroxidase histochemistry. J Comp Neurol. 1984;223:46–56. doi: 10.1002/cne.902230105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Saito K, Moskowitz MA. Contributions from the upper cervical dorsal roots and trigeminal ganglia to the feline circle of Willis. Stroke. 1989;20:524–526. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.4.524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linnemann CC, Jr, Alvira MM. Pathogenesis of varicellazoster angiitis in the CNS. Arch Neurol. 1980;37:239–240. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1980.00500530077013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Doyle PW, Gibson G, Dolman CL. Herpes zoster ophthalmicus with contralateral hemiplegia: identification of cause. Ann Neurol. 1983;14:84–85. doi: 10.1002/ana.410140115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Eidelberg D, Sotrel A, Horoupian DS, Neumann PE, Pumarola-Sune T, Price RW. Thrombotic cerebral vasculopathy associated with herpes zoster. Ann Neurol. 1986;19:7–14. doi: 10.1002/ana.410190103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Amlie-Lefond C, Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Mahalingam R, Davis LE, Gilden DH. The vasculopathy of varicellazoster virus encephalitis. Ann Neurol. 1995;37:784–790. doi: 10.1002/ana.410370612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melanson M, Chalk C, Georgevich L, Fett K, Lapierre Y, Duong H, Richardson J, Marineau C, Rouleau GA. Varicellazoster virus DNA in CSF and arteries in delayed contralateral hemiplegia: evidence for viral invasion of cerebral arteries. Neurology. 1996;47:569–570. doi: 10.1212/wnl.47.2.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kleinschmidt-DeMasters BK, Mahalingam R, Shimek C, Marcoux HL, Wellish M, Tyler KL, Gilden DH. Profound cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis and Froin’s Syndrome secondary to widespread necrotizing vasculitis in an HIV-positive patient with varicella zoster virus encephalomyelitis. J Neurol Sci. 1998;159:213–218. doi: 10.1016/s0022-510x(98)00171-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gilden D, Cohrs RJ, Mahalingam R, Nagel MA. Varicella zoster virus vasculopathies: diverse clinical manifestations, laboratory features, pathogenesis, and treatment. Lancet Neurol. 2009;8:731–740. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(09)70134-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Manco-Johnson MJ, Nuss R, Key N, Moertel C, Jacobson L, Meech S, Weinberg A, Lefkowitz J. Lupus anticoagulant and protein S deficiency in children with postvaricella purpura fulminans or thrombosis. J Pediatr. 1996;128:319–323. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Josephson C, Nuss R, Jacobson L, Hacker MR, Murphy J, Weinberg A, Manco-Johnson MJ. The varicella-autoantibody syndrome. Pediatr Res. 2001;50:345–352. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200109000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kurugöl Z, Vardar F, Ozkinay F, Kavakli K, Cetinkaya B, Ozkinay C. Lupus anticoagulant and protein S deficiency in a child who developed disseminated intravascular coagulation in association with varicella. Turk J Pediatr. 2001;43:139–142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Regnault V, Boehlen F, Ozsahin H, Wahl D, de Grott PG, Lecompte T, de Moerloose P. Anti-protein S antibodies following a varicella infection: detection, characterization and influence on thrombin generation. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:1243–1249. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Massano J, Ferreira D, Toledo T, Mansilha A, Azevedo E, Carvalho M. Stroke and multiple peripheral thrombotic events in an adult with varicella. Eur J Neurol. 2008;15:e90–1. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2008.02267.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reeves M, Sinclair J. Aspects of human cytomegalovirus latency and reactivation. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2008;325:297–313. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-77349-8_17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Weill D. Role of cytomegalovirus in cardiac allograft vasculopathy. Transpl Infect Dis. 2001;2(Suppl 3):44–48. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3062.2001.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Potena L, Valantine HA. Cytomegalovirus-associated allograft rejection in heart transplant patients. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:425–31. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e328259c33b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Melnick JL, Petrie BL, Dreesman GR, Burek J, McCollum CH, DeBakey ME. Cytomegalovirus antigen within human arterial smooth muscle cells. Lancet. 1983;2:644–647. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(83)92529-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Adam E, Melnick JL, Probtsfield JL, Petrie BL, Burek J, Bailey KR, McCollum CH, DeBakey ME. High levels of cytomegalovirus antibody in patients requiring vascular surgery for atherosclerosis. Lancet. 1987;2:291–293. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)90888-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hendrix MG, Salimans MM, van Boven CP, Bruggeman CA. High prevalence of latently present cytomegalovirus in arterial walls of patients suffering from grade III atherosclerosis. Am J Pathol. 1990;136:23–28. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Burns LJ, Pooley JC, Walsh DJ, Vercellotti GM, Weber ML, Kovacs A. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression in endothelial cells is activated by cytomegalovirus immediate early proteins. Transplantation. 1999;67:137–144. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199901150-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dengler TJ, Raftery MJ, Werle M, Zimmermann R, Schonrich G. Cytomegalovirus infection of vascular cells induces expression of pro-inflammatory adhesion molecules by paracrine action of secreted interleukin-1beta. Transplantation. 2000;69:1160–1168. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200003270-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qiu H, Straat K, Rahbar A, Wan M, Soderberg-Naucler C, Haeggstrom JZ. Human CMV infection induces 5-lipoxygenase expression and leukotriene B4 production in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Exp Med. 2008;205:19–24. doi: 10.1084/jem.20070201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Espinola-Klein C, Rupprecht HJ, Blankenberg S, Bickel C, Kopp H, Rippin G, Hafner G, Pfeifer U, Meyer J. Are morphological or functional changes in the carotid artery wall associated with Chlamydia pneumoniae, Helicobacter pylori, cytomegalovirus, or herpes simplex virus infection? Stroke. 2000;31:2127–2133. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.9.2127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Ridker PM, Hennekens CH, Stampfer MJ, Wang F. Prospective study of herpes simplex virus, cytomegalovirus, and the risk of future myocardial infarction and stroke. Circulation. 1998;98:2796–2799. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.25.2796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Voisard R, Krugers T, Reinhardt B, Vaida B, Baur R, Herter T, Luske A, Weckermann D, Weingartner K, Rossler W, Hombach V, Mertens T. HCMV-infection in a human arterial organ culture model: effects on cell proliferation and neointimal hyperplasia. BMC Microbiol. 2007;7:68. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-7-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reinhardt B, Vaida B, Voisard R, Keller L, Breul J, Metzger H, Herter T, Baur R, Lüske A, Mertens T. Human cytomegalovirus infection in human renal arteries in vitro. J Virol Methods. 2003;109:1–9. doi: 10.1016/s0166-0934(03)00035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Connor MD, Lammie GA, Bell JE, Warlow CP, Simmonds P, Brettle RD. Cerebral infarction in adult AIDS patients: observations from the Edinburgh HIV Autopsy Cohort. Stroke. 2000;31:2117–2126. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.9.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cole JW, Pinto AN, Hebel JR, Buchholz DW, Earley CJ, Johnson CJ, Macko RF, Price TR, Sloan MA, Stern BJ, Wityk RJ, Wozniak MA, Kittner SJ. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome and the risk of stroke. Stroke. 2004;35:51–56. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000105393.57853.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Tipping B, de Villiers L, Wainwright H, Candy S, Bryer A. Stroke in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2007;78:1320–1324. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2007.116103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Park YD, Belman AL, Kim TS, Kure K, Llena JF, Lantos G, Bernstein L, Dickson DW. Stroke in pediatric acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1990;28:303–311. doi: 10.1002/ana.410280302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Leeuwis JW, Wolfs TFW, Braun KPJ. A child with HIV-associated transient cerebral arteriopathy. AIDS. 2007;21:1383–1393. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e3281053a30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bhagavati S, Choi J. Rapidly progressive cerebrovascular stenosis and recurrent strokes followed by improvement in HIV vasculopathy. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2008;26:449–452. doi: 10.1159/000157632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cutfield NJ, Steele H, Wilhelm T, Weatherall MW. Successful treatment of HIV associated cerebral vasculopathy with HAART. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80:936–937. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2008.165852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Modi G, Ranchod K, Modi M, Mochan A. Human immunodeficiency virus associated intracranial aneurysms: report of three adult patients with an overview of the literature. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:44–46. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2006.108878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kure K, Park YD, Kim TS, Lyman WD, Lantos G, Lee S, Cho S, Belman AL, Weidenheim KM, Dickson DW. Immunohistochemical localization of an HIV epitope in cerebral aneurysmal arteriopathy in pediatric acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) Pediatr Pathol. 1989;9:655–667. doi: 10.3109/15513818909022373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tipping B, de Villiers L, Candy S, Wainwright H. Stroke caused by human immunodeficiency virus-associated intracranial large-vessel aneurismal vasculopathy. Arch Neurol. 2006;63:1640–1642. doi: 10.1001/archneur.63.11.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gilden DH, Nagel M. Stroke caused by human immunodeficiency virus-associated vasculopathy. Arch Neurol. 2007;64:763. doi: 10.1001/archneur.64.5.763-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kossorotoff M, Touze E, Godon-Hardy S, Serre I, Mateus C, Mas JL, Zuber M. Cerebral vasculopathy with aneurysm formation in HIV-infected young adults. Neurology. 2006;66:1121–1122. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000204188.85402.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gilden DH, Nagel MA. Cerebral vasculopathy with aneurysm formation in HIV-infected young adults. Neurology. 2006;67:2089. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000250629.85288.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Henry K, Melroe H, Huebsch J, Hermundson J, Levine C, Swensen L, Daley J. Severe premature coronary artery disease with protease inhibitors. Lancet. 1998;351:1328. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79053-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hsue PY, Giri K, Erickson S, MacGregor JS, Younes N, Shergill A, Waters DD. Clinical features of acute coronary syndromes in patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Circulation. 2004;109:316–319. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000114520.38748.AA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bobryshev YV. Identification of HIV-1 in the aortic wall of AIDS patients. Atherosclerosis. 2000;152:529–530. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Goldberg SH, van der MP, Hesselgesser J, Jaffer S, Kolson DL, Albright AV, Gonzalez-Scarano F, Lavi E. CXCR3 expression in human central nervous system diseases. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2001;27:127–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2990.2001.00312.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Eugenin EA, Morgello S, Klotman ME, Mosoian A, Lento PA, Berman JW, Schecter AD. Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infects human arterial smooth muscle cells in vivo and in vitro: implications for the pathogenesis of HIV-mediated vascular disease. Am J Pathol. 2008;172:1100–1111. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2008.070457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barbaro G, Barbarini G, Pellicelli AM. HIV-associated coronary arteritis in a patient with fatal myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1799–1800. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200106073442316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Tinkle BT, Ngo L, Luciw PA, Maciag T, Jay G. Human immunodeficiency virus-associated vasculopathy in transgenic mice. J Virol. 1997;71:4809–4814. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4809-4814.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Mujawar Z, Rose H, Morrow MP, Pushkarsky T, Dubrovsky L, Mukhamedova N, Fu Y, Dart A, Orenstein JM, Bobryshev YV, Bukrinsky M, Sviridov D. Human immunodeficiency virus impairs reverse cholesterol transport from macrophages. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e365. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]