Abstract

Purpose

Limited information exists about the occurrence and the impact of perineural invasion (PNI) in patients with cervical carcinoma (CX).

Methods

The original histologic slides from patients primarily treated by radical hysterectomy and systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy were re-examined regarding the occurrence of PNI. PNI was correlated to recurrence free (RFS) and overall survival (OS).

Results

35.1% of all patients (68/194) represented perineural invasion (=PNI). The 5-year-overall-survival-rate was significantly decreased in patients representing PNI, when they were compared with those without PNI (51.1% [95% CI 38.0–64.2] vs. 75.6% [95% CI 67.8–83.4]; p = 0.001). In a separate analysis the prognostic impact persisted in the node negative, but disappeared in the node-positive cases. In multivariate analysis, pelvic lymph node involvement and PNI were independent prognostic factors for overall survival.

Conclusions

Perineural invasion is seen in about one-third of patients with cervical carcinoma. Patients affected by PNI represented a decreased overall survival. Further studies are required to get a deeper insight into the clinical impact and the pathogenetic mechanisms of PNI in CX.

Keywords: Cervical carcinoma, Tumor spread, Perineural invasion, Perineural spread, Prognosis

Introduction

Key features of malignant tumor growth are to destroy the pre-existing extracellular matrix and the ability of the tumor cells to dissociate from the primary tumor. Blood vessel and lymphovascular invasion are well accepted parameters of local tumor spread. Another, but under-recognized route of tumor spread occurs in and along nerves (Liebig et al. 2009). Tumor spread along nerves has been defined as tumor cell growth in, around, and through the nerves (Batsakis 1985; Liebig et al. 2009) and named perineural invasion (PNI). PNI might be a cause for pelvic cancer pain. It has been reported that about 60% of patients with pelvic cancer have neuropathic pain (Rigor 2000). Initial symptoms might be subtle and may preceding the diagnosis, but PNI may cause complex lumbosacral plexopathies with a wide range of clinical symptoms in cervical cancer patients.

Although PNI is a relatively common feature in a variety of human malignancies, as in adenoid cystic and squamous cell sinunasal cancers, pancreatic and prostatic carcinomas with prognostic impact (Gil et al. 2009; Harnden et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2007; Sudo et al. 2008), little research attention has been paid to this parameter. In carcinoma of the cervix uteri (CX), the vast majority of studies dealing with prognostic factors do not cover PNI in their analyses (Morice et al. 1999; Pieterse et al. 2008; Sartori et al. 2007; Takeda et al. 2002; Trimbos et al. 2004). Furthermore, PNI is not recognized in recent reviews about morphologic prognosticators in CX (Singh and Arif 2004). Only few reports showed that PNI within the parametrial/pelvic tissue represents an adverse prognostic factor in primary or recurrent CX (Beitler et al. 1997; Memarzadeh et al. 2003). But, nerves occur not only in the parametrial/pelvic side wall tissue, but also in the cervical stroma (Bae et al. 2001; Tingåker et al. 2008) and are in that context involved in the contractility of the uterus and might also be a subject of invasion by carcinoma of the uterine cervix. The objective of this study was to estimate the frequency of PNI in squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix and the evaluation of its prognostic impact.

Materials and methods

Data from patients with CX, staged FIGO IB to IIB, were obtained from the files of our Wertheim-Archive (Horn and Bilek 2001). Patients who received neoadjuvant therapy, those with incomplete local tumor resection (R1-resection = microscopic tumor at the resection margins of the radical hysterectomy specimen or R2-resection = macroscopic tumor at the margins) and tumors of other histologic type such as squamous cell were excluded from the study. All women were treated with radical abdominal hysterectomy Piver type III (Piver et al. 1974) and radical pelvic lymphadenectomy, but without para-aortal lymph node resection. All patients with parametrial invasion and/or pelvic lymph node involvement received adjuvant combined radiation therapy without concurrent chemotherapy.

The pathological examination of the radical hysterectomy specimen was made in a standardized manner (Horn et al. 2007; Kurman and Amin 1999) as was for resected lymph nodes (Horn et al. 2005). All tumors were staged and classified according to WHO- and TNM-classification (Sobin and Wittekind 2002; Wells et al. 2003).

Perineural involvement (PNI) was defined as the detection of malignant cells in the perineural space of nerves, regardless if the nerve itself was infiltrated by the tumor and regardless of the extension of the involvement of the perineural tissue (Batsakis 1985; Dunn et al. 2009; Liebig et al. 2009). The detection of PNI was termed as PNI 1 and cases without PNI as PNI 0. No anciliar techniques were used for identifying PNI and there was no recutting of the archival material. Any detectable perineural invasion was stated as PNI 1, regardless if one or multiple nerves were affected in the individual case.

Follow-up data were obtained from the clinical files. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for the use of the data. Additionally, the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB).

Survival data were analyzed using Kaplan–Meier-curves and log-rank-test. 5-year overall and recurrence-free survival rates with 95% confidence intervals (CI) are given. Categorical data were analyzed by χ 2 test. p values ≤0.05 were considered as statistically significant. To assess the independent impact of perineural involvement on overall survival a Cox regression model was fitted, using the software package SPSS for Windows®, release 15.5.1 (SPSS GmbH Munich, Germany).

Results

194 patients were enrolled in the study. Follow-up information was available for almost all patients (99%) and only two patients were lost during follow-up. The median follow-up time was 61.6 months [95% CI: 59.9–63.3 months].

About 35.1% (68/194) of all cases represented perineural invasion. Patient characteristics are given in Table 1 and PNI is illustrated in Fig. 1. There was a significant correlation between the frequency of PNI and post-operative tumor stage. PNI was seen in 10.9% of the tumors staged pT1b1, 32.1% in pT1b2, 38.9% in pT2a, and 53.6% in pT2b (p < 0.001). Patients with deep cervical stromal invasion (>66%) showed significantly more PNI as those with more superficial invasion (41 vs. 16.9%; p = 0.001). PNI was significantly more common in patients with pelvic lymph node involvement (48.9%) when they were compared with patients without lymph node metastases (23.6%; p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Median age | 44 years (range 23–80 years) |

|---|---|

| Stage distribution | |

| pT1b1 | 64 (33.0%) |

| pT1b2 | 28 (14.4%) |

| pT2a | 18 (9.3%) |

| pT2b | 84 (43.3%) |

| Pelvic lymph node involvement | |

| pN0 | 106 (54.6%) |

| pN1 | 88 (45.4%) |

| Perineural infiltration | |

| No | 126 (64.9%) |

| Yes | 68 (35.1%) |

| Recurrent disease | |

| No | 147 (76.6%) |

| Yes | 45 (23.2%) |

| Unknown | 2 (1.0%) |

Fig. 1.

Histologic pictures from perineural invasion (PNI) in squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix. a about 90% of the circumference of the nerve is infiltrated by the carcinoma (H&E staining, ×124), b entrapping of the nerve within the infiltrating carcinoma (H&E staining, ×124), c and d perineural infiltration of small clusters of the carcinoma (arrows, H&E staining ×214 and ×124)

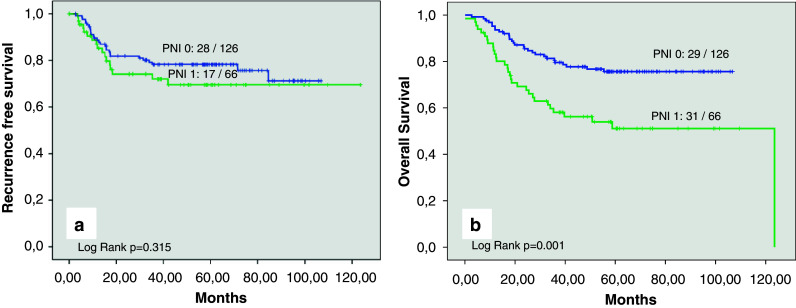

Patients with perineural invasion (PNI) represented reduced 5-year recurrence-free survival when they were compared with patients without perineural invasion (69.5% [95% CI: 57.2–81.8%] vs. 78.3% [95% CI: 70.9–85.7%]; Fig. 2a), but the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.3). The separate analysis of node-negative and node-positive cases represented also no statistical difference regarding recurrence free survival (data not given).

Fig. 2.

a Kaplan–Meier curve for recurrence-free survival in patients with perineural invasion (PNI 1) and those without perineural invasion (PNI 0). b Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival in patients with perineural invasion (PNI 1) and those without perineural invasion (PNI 0)

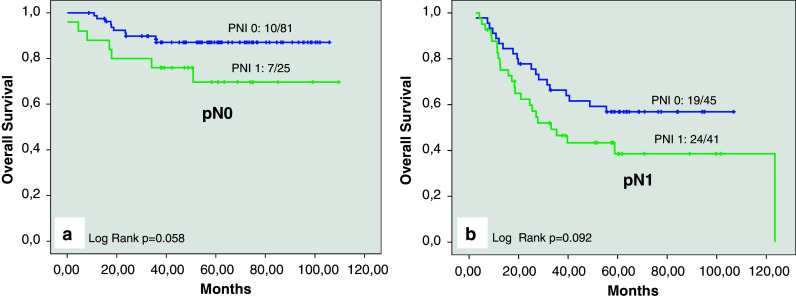

In contrast, the 5-year-overall-survival-rate was significantly decreased in patients with PNI (51.1% [95% CI: 38.0–64.2]) when they were compared with patients without PNI (75.6% [95% CI: 67.8–83.4]; p = 0.001; Fig. 2b). In a separate analysis of node-negative and node-positive cases, the presence of PNI was associated with reduced 5-year overall survival, but the statistical analysis failed to show a significant difference (Table 2; Fig. 3a).

Table 2.

Overall survival rate (OSR) for patients with squamous cell carcinoma of the uterine cervix with and without perineural invasion

| 5-year-OSR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| All cases | |||

| PNI 0 | 75.6% | [67.8–83.4%] | |

| PNI 1 | 51.1% | [38.0–64.2%] | p = 0.001 |

| Node negative cases (pN0) | |||

| PNI 0 | 87.1% | [79.7–94.5%] | |

| PNI 1 | 69.7% | [50.3–89.1%] | p = 0.058 |

| Node-positive cases (pN1) | |||

| PNI 0 | 56.6% | [42.4–71.6%] | |

| PNI 1 | 38.6% | [21.9–55.3%] | p = 0.092 |

Fig. 3.

a Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival for patients without pelvic lymph node involvement (pN0) with perineural invasion (PNI 1) and those without perineural invasion (PNI 0). b Kaplan–Meier curve for overall survival for patients with pelvic lymph node involvement (pN1) with perineural invasion (PNI 1) and those without perineural invasion (PNI 0)

Multivariate Cox regression analysis was performed to assess the independent prognostic impact of perineural invasion overall survival in comparison with established prognostic factors in CX. The analysis included tumor stage, status of pelvic lymph node involvement, tumor grade, peritumoral desmoplastic change, and PNI. Pelvic lymph node involvement and the occurrence of PNI represented as independent prognostic factors in that setting (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of prognostic factors regarding overall survival

| RR | 95% CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perineural invasion | |||

| No (PNI 0) | Reference | ||

| Yes (PNI 1) | 2.0 | 1.0–4.0 | 0.050 |

| Pelvic lymph node involvement | |||

| No (pN0) | Reference | ||

| Yes (pN1) | 2.2 | 1.1–4.3 | 0.026 |

| Tumor grade | |||

| G1 | Reference | ||

| G2 | 1.0 | 0.5–1.8 | 0.883 |

| G3 | 1.1 | 0.5–2.9 | 0.789 |

| Tumor stage | |||

| pT1b | Reference | ||

| pT2 | 1.7 | 0.8–3.6 | 0.148 |

| Peritumoral desmplastic change | |||

| None/moderate | Reference | ||

| Weak | 0.6 | 0.3–1.5 | 0.299 |

| Strong | 1.1 | 0.5–2.3 | 0.858 |

Discussion

Perineural invasion (PNI) is the process of invasion of nerves by a malignant tumor and is emerging as an important pathologic feature of several malignancies.

During the past years it has become evident that PNI is not an extension of lymphatic metastasis, because it was shown that lymphatic channels do not penetrate the inner parts of the nerve sheet (for review see Liebig et al. 2009). The reason why some carcinomas exhibit a predilection for PNI, whereas others do not, remains unknown in detail. Earlier theories have stressed the fact that tumor cells spreading along neural sheets are privileged to a low resistance plane, which serves as a conduit for their migration. But, recent evidence in prostate and pancreatic cancer suggests that several neurotrophins, produced by the tumor cells, promote the tumor cell invasion into nerve sheets and may be key mediators in the pathogenesis of PNI (Dalal and Djakiew 1997; Ketterer et al. 2003).

Benign inclusions in the perineural space simulating PNI and nodular peritumoral fibrosis as a mimicker of PNI must be considered in the differential diagnosis of PNI (Fellegara and Kuhn 2007; Hassanein et al. 2005). But, additional immunohistochemical staining, e.g., for p16 and S-100 protein, might help to overcome any difficulties in the majority of cases.

For some human malignancies, such as adenoid cystic and squamous cell sinunasal cancers, squamous cell carcinomas of the skin, pancreatic and prostatic carcinomas as well as bile duct carcinomas, PNI represents a poor prognosticator (Dunn et al. 2009; Gil et al. 2009; Harnden et al. 2007; Lee et al. 2007). Furthermore, PNI was used to define a new subclassification of bile-duct carcinomas (Yokoyama et al. 2008). But, the knowledge about the frequency and the impact in carcinoma of the cervix (CX) is limited (Beitler et al. 1997; Memarzadeh et al. 2003) and also large prognostic studies dealing with morphologic parameters do not recognize PNI at all (Morice et al. 1999; Pieterse et al. 2008; Sartori et al. 2007; Singh and Arif 2004; Takeda et al. 2002; Trimbos et al. 2004).

In the present study we evaluated a cohort of 194 surgically treated patients with CX and PNI occured in 35.1%. Patients with pelvic lymph node involvement showed a significant higher risk of PNI (p < 0.001). PNI was significantly correlated with increased tumor stage. Patients with histologic proven parametrial invasion (post-surgical stage pT2b) showed PNI in 53.6% (45/84) compared with those patients without parametrial involvement (20.9%; 23/110). Additionally, tumors with deep cervical stromal invasion, defined as infiltration ≥66%, represented significantly more PNI (41.0 vs. 16.9%; p < 0.001). So, as suggested in a previous study for CX with large tumor size for the detection of occult parametrial invasion (Horn et al. 2007), careful and sometimes extensive sampling is recommended for large and/or local advanced CX to establish PNI. Once the presence of PNI is established by microscopic evaluation of radical hysterectomy specimens, especially in stage IIB-disease, it is important to obtain clear margins. In the daily practice, we examine the parametrial resection margin by embedding this tissue in a separate paraffine block to establish the status of this resection margin (Morice et al. 1999).

The 5-year recurrence-free survival rate was reduced in patients representing PNI when compared with those without PNI (78.3 vs. 69.5%), but the difference was not statistically significant. The reasons for this are speculative at time. Perhaps it is caused by the limited number of cases available within our study.

In contrast to that findings, the 5-year overall survival rate was significantly decreased in patients with PNI, compared with those without PNI (51.1 vs. 75.6%; p = 0.001). In a separate analysis of node negative and node-positive cases, the prognostic impact of PNI on overall survival represented “borderline significance” and the difference in node-positive cases between those with and without PNI was not significant. But, in detailed interpretation of Table 2 and by careful reading of the Fig. 3a and b it can be obtained that there is a difference in the 5-year overall survival rate of about 18% in both groups. The missing statistical significance of these differences might be caused by the limited number of cases within the study.

In a multivariate Cox regression analysis, including post-surgical tumor stage, pelvic lymph node involvement, peritumoral desmoplastic change, and tumor grade, pelvic lymph node involvement and PNI represented as independent prognostic factor for overall survival.

Memarzadeh et al. (2003) evaluated the presence of PNI in the parametrial tissue within 93 surgically treated early stage CX. They observed parametrial PNI in 7.5%. Beside lymph node involvement, large tumor size, deep stromal invasion, and lymphovascular space involvement (LVSI), PNI was a predictor for recurrent disease and poor overall survival. In a subset analysis of patients with negative lymph nodes (n = 66), tumor size and PNI represented as indicators for poor outcome. In a retrospective analysis of 26 patients with recurrent CX who underwent total pelvic exenteration, the presence of either close margins, LVSI, PNI, or a combination of these factors adversely affected both disease-specific survival and local tumor control (Beitler et al. 1997). In a small study of 26 patients which is published as an abstract, including FIGO-stage I squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix, PNI was seen in eight patients (30.8%). In this study, patients affected by PNI represented a shorter overall survival than those without PNI (Ozan et al. 2004).

The clinical impact of PNI is speculative at time. Abstracting the data from our study and the few ones reported in the literature, PNI might represent an additional poor prognostic factor in patients with surgically treated CX. In cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma the histologic diagnosis of PNI might be an indication for adjuvant therapy (Limawararut et al. 2007). Beitler et al. (1997), in their study of recurrent CX treated with exenteration procedure, suggested that radiation therapy might be beneficial to patients representing PNI.

One disadvantage of the present study might be that all patients were treated before the introduction of chemotherapy or chemoradiation in the treatment approaches of CX. Consecutively, also patients with preoperative FIGO stage IB2 and IIB were surgically treated within the study period who would nowadays be candidates for chemoradiation as primary treatment approach. Regardless of those limitations and the very few data of PNI in the literature, PNI represents an additional morphologic feature of local tumor spread of CX. So, clinicians should request the pathologists to test for the presence of perineural invasion in carcinoma of the uterine cervix, and this parameter should be mentioned in the final pathologic oncology report of surgically treated CX. Further studies are required to get a deeper insight into the clinical impact and the pathogenetic mechanisms of PNI in CX.

References

- Bae SE, Corcoran BM, Watson ED (2001) Immunohistochemical study of the distribution of adrenergic and peptidergic innervation in the equine uterus and the cervix. Reproduction 122:275–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Batsakis JG (1985) Nerves and neurotropic carcinomas. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol 94:426–427 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beitler JJ, Anderson PS, Wadler S, Runowicz CD, Hayes MK, Fields AL, Sood B, Goldberg GL (1997) Pelvic exenteration for cervix cancer: would additional intraoperative interstitial brachytherapy improve survival? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 38:143–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalal R, Djakiew D (1997) Molecular characterization of neurotrophin expression and the corresponding tropomyosin receptor kinases (trks) in epithelial and stromal cells of the human prostate. Mol Cell Endocrinol 134:15–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunn M, Morgan MB, Beer TW (2009) Perineural invasion: identification, significance, and a standardized definition. Dermatol Surg 35:214–221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fellegara G, Kuhn E (2007) Perineural and intraneural “invasion” in benign proliferative breast disease. Int J Surg Pathol 15:286–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gil Z, Carlson DL, Gupta A, Lee N, Hoppe B, Shah JP, Kraus DH (2009) Patterns and incidence of neural invasion in patients with cancers of the paranasal sinuses. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 135:173–179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harnden P, Shelley MD, Clements H, Coles B, Tyndale-Biscoe RS, Naylor B, Mason MD (2007) The prognostic significance of perineural invasion in prostatic cancer biopsies: a systematic review. Cancer 109:13–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassanein AM, Proper SA, Depcik-Smith ND, Flowers FP (2005) Peritumoral fibrosis in basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma mimicking perineural invasion: potential pitfall in Mohs micrographic surgery. Dermatol Surg 31:1101–1106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn LC, Bilek K (2001) Cancer register for cervix carcinoma—useful and necessary? Zentralbl Gynakol 123:311–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn LC, Einenkel J, Hockel M, Kolbl H, Kommoss F, Lax SF, Riethdorf L, Schnurch HG, Schmidt D (2005) Recommendations for the handling and oncologic pathology report of lymph node specimens submitted for evaluation of metastatic disease in gynecologic malignancies. Pathologe 26:266–272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn LC, Einenkel J, Hockel M, Kolbl H, Kommoss F, Lax SF, Reich O, Riethdorf L, Schmidt D (2007a) Pathoanatomical preparation and reporting for dysplasias and cancers of the cervix uteri: cervical biopsy, conization, radical hysterectomy and exenteration. Pathologe 28:249–260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horn LC, Fischer U, Raptis G, Bilek K, Hentschel B (2007b) Tumor size is of prognostic value in surgically treated FIGO stage II cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 107:310–315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketterer K, Rao S, Friess H, Weiss J, Büchler MW, Korc M (2003) Reverse transcription-PCR analysis of laser-captured cells points to potential paracrine and autocrine actions of neurotrophins in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res 9:5127–5136 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurman RJ, Amin MB (1999) Members of the Cancer Committee, College of American Pathologists. Protocol for the examination of specimens from patients with carcinomas of the cervix. A basis for checklists. Arch Pathol Lab Med 123:55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee IH, Roberts R, Shah RB, Wojno KJ, Wei JT, Sandler HM (2007) Perineural invasion is a marker for pathologically advanced disease in localized prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 68:1059–1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebig C, Ayala G, Wilks JA, Berger DH, Albo D (2009) Perineural invasion in cancer: a review of the literature. Cancer 115:3379–3391 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Limawararut V, Leibovitch I, Sullivan T, Selva D (2007) Periocular squamous cell carcinoma. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol 35:174–185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Memarzadeh S, Natarajan S, Dandade DP, Ostrzega N, Saber PA, Busuttil A, Lentz SE, Berek JS (2003) Lymphovascular and perineural invasion in the parametria: a prognostic factor for early-stage cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol 102:612–619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morice P, Castaigne D, Pautier P, Rey A, Haie-Meder C, Leblanc M, Duvillard P (1999) Interest of pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy in patients with stage IB and II cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 73:106–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ozan H, Bilgin T, Celik N, Erol O, Ediz B (2004) The importance of perineural invasion in cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 14:731 [Google Scholar]

- Pieterse QD, Kenter GG, Eilers PH, Trimbos JB (2008) An individual prediction of the future (disease-free) survival of patients with a history of early-stage cervical cancer, multistate model. Int J Gynecol Cancer 18:432–438 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piver MS, Rutledge F, Smith JP (1974) Five classes of extended hysterectomy for women with cervical cancer. Obstet Gynecol 44:265–272 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rigor BM Sr (2000) Pelvic cancer pain. J Surg Oncol 75:280–300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sartori E, Tisi G, Chiudinelli F, La Face B, Franzini R, Pecorelli S (2007) Early stage cervical cancer: adjuvant treatment in negative lymph node cases. Gynecol Oncol 107:170–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh N, Arif S (2004) Histopathologic parameters of prognosis in cervical cancer—a review. Int J Gynecol Cancer 14:741–775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobin LH, Wittekind C (2002) TNM-classification of malignant tumors, 6th edn. Wiley-Liss, London [Google Scholar]

- Sudo T, Murakami Y, Uemura K, Hayashidani Y, Hashimoto Y, Ohge H, Shimamoto F, Sueda T (2008) Prognostic impact of perineural invasion following pancreatoduodenectomy with lymphadenectomy for ampullary carcinoma. Dig Dis Sci 53:2281–2286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda N, Sakuragi N, Takeda M, Okamoto K, Kuwabara M, Negishi H, Oikawa M, Yamamoto R, Yamada H, Fujimoto S (2002) Multivariate analysis of histopathologic prognostic factors for invasive cervical cancer treated with radical hysterectomy and systematic retroperitoneal lymphadenectomy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 81:1144–1151 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tingåker BK, Ekman-Ordeberg G, Facer P, Irestedt L, Anand P (2008) Influence of pregnancy and labor on the occurrence of nerve fibers expressing the capsaicin receptor TRPV1 in human corpus and cervix uteri. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 12:6–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trimbos JB, Lambeek AF, Peters AA, Wolterbeek R, Gaarenstroom KN, Fleuren GJ, Kenter GG (2004) Prognostic difference of surgical treatment of exophytic versus barrel-shaped bulky cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 95:77–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wells M, Östör AG, Crum CP, Franceschi S, Tommasino M, Nesland JM, Goodman AK, Sankaranayanan R, Hanselaar AG, Albores-Saavedra J (2003) Epithelial tumors of the uterine cervix. In: Tavassoli FA, Devilee P (eds) Pathology and genetics of tumours of the breast and female genital organs. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. IARC Press, Lyon, pp 259–279

- Yokoyama Y, Nishio H, Ebata T, Abe T, Igami T, Oda K, Nimura Y, Nagino M (2008) New classification of cystic duct carcinoma. World J Surg 32:621–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]