Abstract

Objective

This pilot study in parenteral nutrition (PN) dependent infants with short bowel syndrome (SBS) evaluated the impact of feeding route and intestinal permeability on bloodstream infection (BSI), small bowel bacterial overgrowth (SBBO) and systemic immune responses, and fecal calprotectin as a biomarker for SBBO.

Study design

10 infants (ages 4.2-15.4 months) with SBS due to necrotizing enterocolitis were evaluated. Nutritional assessment, breath hydrogen testing, intestinal permeability, fecal calprotectin, serum flagellin- and LPS- specific antibody titers, and proinflammatory cytokine concentrations (TNF-α, IL-1 β, IL-6, IL-8) were performed at baseline, 60 and 120 days. Healthy, age-matched controls (n=5) were recruited.

Results

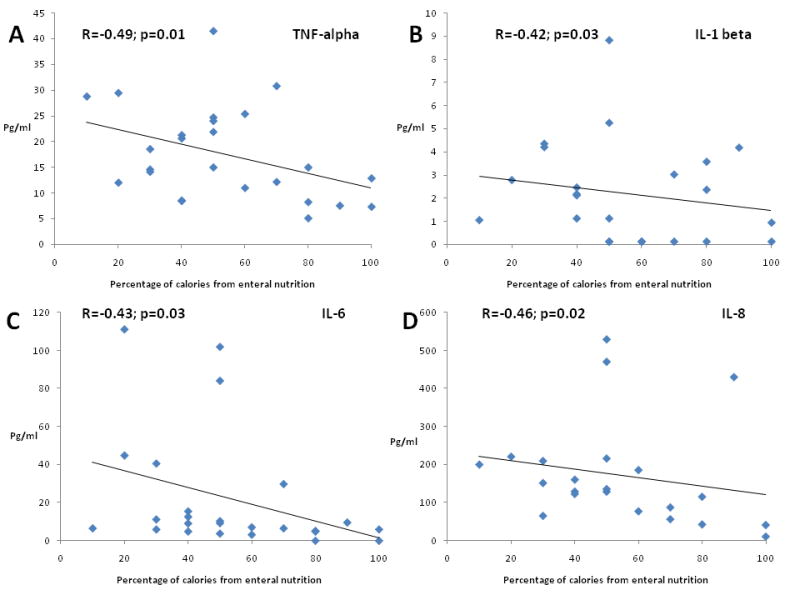

BSI incidence was high (80%) and SBBO was common (50%). SBBO increased the odds for BSI (> 7-fold; p=0.009). Calprotectin levels were higher in children with SBS and SBBO versus those without SBBO and healthy controls (p<0.05). Serum TNF-α, was elevated at baseline versus controls. Serum TNF-α, IL-1 β, IL-6 and IL-8 levels diminished with increased enteral nutrition. Anti-flagellin and anti-LPS IgG levels in children with SBSwere lower versus controls and rose over time.

Conclusion

In children with SBS, SBBO increases the risk for BSI and systemic proinflammatory response decreases with increasing enteral feeding and weaning PN.

Short bowel syndrome (SBS) is a rare but devastating clinical entity that is defined as a spectrum of diarrhea and malabsorption with associated complications (e.g. growth stunting, malnutrition) due to insufficient bowel length (1). In children, SBS is often the result of massive small bowel resection due to necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) or major congenital gastrointestinal malformations (e.g. gastroschisis, intestinal atresia) (2). Recurrent bloodstream infections (BSI) and small bowel bacterial overgrowth (SBBO) are believed to be common complications associated with pediatric SBS, though only limited data are available (2, 3). We recently reported that BSI and malnutrition were the most frequent indication for readmission of very low birth weight infants with SBS (2). Inpatient admissions account for majority of the cost of care in pediatric patients with SBS in the first year following diagnosis (4). Recurrent BSI and prolonged parenteral nutrition (PN) are identified as predictors of increased morbidity and mortality (5-6).

Initial management of SBS typically is characterized by dependency on PN which is vital for patient survival. However, systemic inflammatory responses, intestinal villous atrophy and liver disease occur in infants and children who require prolonged PN administration (4-6). The presence of SBBO also is associated with villous atrophy and a mucosal inflammatory response, which may theoretically contribute to loss of intestinal epithelial barrier function (7, 8). Decreased gut barrier functions may potentially increase movement of luminal bacteria and their constituents [e.g. flagellin, lipopolysaccharide (LPS)] to underlying tissue and blood via transcellular or paracellular pathways (9). Animal models and limited human studies support the role of both SBBO and use of PN as inducers of systemic or local inflammation concomitant with gut barrier dysfunction (7, 9). Flagellin is a monomeric subunit of flagella found on motile bacteria (10). Previously our group reported the detection of flagellin in serum and increased serum anti-flagellin immunoglobulins in PN-dependent adults with SBS (11). Flagellin interacts with basolateral toll-like receptor-5 on gut epithelial cells leading to the secretion of cytokines and chemokines (12). Cytokines recruit polymorphonuclear neutrophils locally and induce mucosal inflammation (10, 12). Calprotectin, a product of neutrophil catabolism, is a biomarker of gut mucosal inflammation in inflammatory bowel disease (13-14).

This 4-month pilot study in infants with PN-dependent SBS following NEC was designed to serially evaluate: (1) the incidence of bloodstream infection (BSI) and SBBO; (2) the impact of route of feeding and intestinal permeability on BSI, SBBO and systemic immune responses (pro-inflammatory cytokine levels, presence of flagellin and flagellin-specific and LPS-specific immunoglobulin A and G (IgA and IgG) levels); and (3) the potential utility of fecal calprotectin as a biomarker for SBBO.

Methods

Children less than 2 years of age with history of SBS due to massive small bowel or colonic resection or both following the diagnosis of NEC were enrolled in this study. SBS was defined as dependence on PN for at least 3 months with bowel length (measured along the anti-mesenteric border from the ligament of Treitz) of less than 30% of estimated normal small bowel length for age (15, 16). Normal small bowel length for age was estimated using previously published data (16). The children with SBS were included if they met the following criteria: (1) receiving enteral feeds; and (2) intact stomach, duodenum and no active enterocutaneous fistulae. Children with SBS were excluded if they had: (1) use of antibiotics, probiotics or prebiotics (e.g. fructo-oligosaccharides) within 2 weeks of enrollment; and (2) history of liver or small bowel transplantation. A sample size of 10 patients was chosen to provide the pilot data rather than statistical power for hypothesis testing. A comparison group of 5 age-matched healthy children without any history of intestinal resection also were recruited.

The institutional review boards of Emory University School of Medicine and Children's Healthcare of Atlanta in Atlanta, GA approved this protocol. Children with SBS enrolled in this study had serial procedures performed during 3 visits to the Emory University Hospital, General Clinical Research Center (GCRC). Each visit was separated by 2 months (Baseline, week 8, and week 16). GCRC procedures were delayed by 2 weeks if the child had a positive BSI to allow for the child to complete antibiotic therapy.

After an overnight fast of at least 8 hours, each child was admitted to the GCRC for 36 hours. The child's weight and length was measured in duplicate using a standard pediatric scale and a horizontal stadiometer (length board) respectively. A trained bionutritionist interviewed the primary caregivers to obtain a 24-hour recall of all the enteral nutrition consumed by the child (17). Data were entered into Food Processor SQL© Nutrition Analysis Software (ESHA Research, Salem, OR) to calculate calories and protein intake. PN intake was assessed by reviewing the composition of PN orders and the volume of PN administered, and total (enteral and PN) calories/day and grams of protein/day were calculated. The percent of total energy and protein provided parenterally and enterally were also calculated. Peripheral blood was obtained for analysis of pro-inflammatory cytokines; interleukin (IL) -1 beta, IL-6, IL-8, tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α); serum was also obtained for the presence of flagellin, anti-flagellin and anti-lipopolysaccharide immunoglobulin G (IgG). Baseline breath hydrogen was collected followed by the administration of D-glucose solution (1g/kg) orally or through the child's enterostomy tube. Breath hydrogen samples were then collected 20, 40, 60 and 90 minutes after completion of D-glucose ingestion (18). Small bowel transit time was not estimated in the study subjects. A random stool sample was collected and stored at -80°C until analysis for fecal calprotectin.

At midnight, enteral feeds were held for an overnight fast of 8 hours. At 8 am of day 2, a lactulose/mannitol (L/M) permeability test was performed. A test solution containing lactulose (30 mg/mL; UDL Laboratories, Rockford, IL) and mannitol (20 mg/mL; American Regent Laboratories, Shirley, NY) was administered at a dose of 1 mL/kg body weight orally (or via an enterostomy tube) over 10 minutes (19). All urine was then collected for the subsequent 6 hours and drained into containers containing chlorhexidine gluconate as a bacteriostatic agent. The total urine volume was measured and aliquots frozen at −80°C.

During these visits at week 4 and 12, the child had nutritional evaluation and enteral nutrition optimization with a standardized clinical protocol utilizing stool output (stool in g/kg/d and number of stools/d) or ileostomy output (mL/kg/day) and measurement of stool reducing substances as an index of the severity of malabsorption. The degree of malabsorption was factored into the estimates of caloric needs as the weight and length velocity of the patient and not the absolute weight alone guided the calculations for the nutrition provided. Contraindications to increasing enteral nutrient infusion were paralytic or drug-induced ileus, grossly bloody stools or ostomy output and/or radiologic changes consistent with intestinal ischemia, stool output increasing by more than 50% in 24 hours, bilious and/or persistent vomiting (defined as > 3 episodes of emesis in 12 hours), clinical suspicion of obstruction or ileus and electrolyte instability. The goal was to maintain each child at a weight and length velocity along established percentiles for age.

The subject's medical chart was reviewed to document episodes of hospital admissions and BSI. BSI was identified when organisms were cultured from blood during febrile illness.

Five healthy age-matched children had blood drawn once for measurements of proinflammatory cytokines (IL -1 beta, IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α), circulating flagellin, anti-flagellin and anti-LPS IgG. Stool also was collected for measurement of calprotectin.

Analytic methods

Serum analysis for pro-inflammatory cytokines was performed in the GCRC laboratory using a multiplex system (Luminex Inc. Austin, Tx). Serum analysis for serum LPS was by limulus method and for serum flagellin, flagellin-specific, LPS-specific IgA and IgG by ELISA, as previously described (11, 12). Fecal calprotectin levels were measured by Genova Diagnostics (Asheville, NC) using a quantitative enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method (Calprest, Eurospital SpA, Trieste, Italy) (20).

Breath samples were analyzed within 3 hours of collection using a microlyzer (Model SC, QuinTron Instrument Co. Milwaukee, WI). SBBO was diagnosed based on an increased fasting breath hydrogen level ≥ 20 part per million (ppm) or increase from baseline of ≥ 10 ppm after the ingestion of glucose (18, 21). Urinary lactulose and mannitol concentrations was performed in the laboratory of one of the investigators (JBM) using a highly sensitive HPLC assay (22).

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 16; SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois). Student t-tests were used to compare flagellin- and LPS-specific immunoglobulin values in control serum samples compared with baseline, weeks 8 and 16 serum samples in SBS subjects. Association between SBBO and tolerance of enteral feeds (percentage of feeds enterally) were determined using point biserial correlation coefficients. Pearson correlation was used to determine the relationship between calprotectin levels and breath hydrogen, and cytokines and enteral calories tolerated. Calprotectin, serum flagellin, flagellin- and LPS-specific IgA and IgG levels were compared between patients with SBS and controls. Paired t-tests were used to compare calprotectin, serum flagellin, flagellin- and LPS-specific IgA and IgG levels from baseline to 8 weeks and baseline to 16 weeks within the SBS group. Logistic regression using the generalized estimating equation model was performed to assess the odds of BSI in children with and without SBBO. Statistical significance was based on a 5% significance level.

Results

The 10 children with SBS were 6 boys and 4 girls with a median chronologic age of 7.2 months (range 4.2 - 15.4 months). Patient characteristics are shown in Table I. All children had SBS as a result of surgical resection due to NEC and were dependent on PN at the time of enrollment. Residual small bowel length ranged from 25 - 60 cm, which represented approximately 20% of expected length of small bowel for age. At baseline, the median percentage of calories delivered by PN was 54% (range 20 to 80%), which decreased to median of 35% (range 0 to 60%) at the end of the study period. Of the 10 children with SBS enrolled in the study, 7 completed all of the procedures. Patient #1 was withdrawn from the study after the second visit to the GCRC because he was referred for small bowel transplant. Patient #4 died prior to the 3rd GCRC visit and patient #2 voluntarily withdrew from the study prior to the 3rd GCRC visit.

Table 1.

SBS patient demographic data

| Subject | GA (weeks) |

Chronological Age at enrollment (months) |

Corrected Age (months) |

Gender 1 | Race 2 | Residual small bowel length (cm) | Percentage of expected bowel length (%) |

Colon (%) |

Time since last bowel resection (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 30 | 15.4 | 12.9 | M | AA | 60 | 30 | 50 | 14 |

| 2 | 34 | 9.0 | 7.8 | M | AA | 60 | 25 | 50 | 8.5 |

| 3 | 32 | 4.2 | 2.2 | F | AA | 60 | 27 | 50 | 3 |

| 4 | 28 | 5.9 | 2.9 | F | W | 43 | 24 | 100 | 2 |

| 5 | 31 | 4.8 | 2.5 | M | AA | 25 | 12 | 100 | 3 |

| 6 | 29 | 6.4 | 3.5 | M | AA | 25 | 13 | 50 | 5 |

| 7 | 31 | 8.0 | 6.0 | M | W | 35 | 17 | 80 | 8 |

| 8 | 32 | 4.8 | 2.8 | F | AA | 45 | 20 | 100 | 4 |

| 9 | 31 | 8.7 | 6.5 | M | AA | 43 | 20 | 100 | 8 |

| 10 | 27 | 8.5 | 4.5 | F | AA | 36 | 21 | 50 | 8.3 |

| Median (range) | 32 (13) | 7.2 (11.2) | 4 (10.7) | 6M/4F | 8AA/2W | 43 (35) | 20 (18) | 65 (50) | 6 (12) |

M: Male, F: Female;

AA: African American, W: White

Incidence of SBBO

Bacterial overgrowth was diagnosed by hydrogen breath testing in 5 (50%) patients with SBS during one or more GCRC visits. SBBO in these infants was diagnosed at the baseline visit in 3 subjects (subjects 4, 5 and 7) and at study day 60 in 2 additional (subjects 1 and 10). Subject #4 had SBBO diagnosed at baseline and again on day 60. The diagnosis of SBBO was not related to bowel length or degree of enteral tolerance in these children; however, the colon was in continuity with the residual small bowel at the time of the diagnosis. Ileocecal valve was present in 2 of the 5 children with SBBO.

Incidence of BSI

There were a total of 20 BSIs documented in 80% (8/10) of infants with SBS during the 4 month study period. All of the subjects diagnosed with SBBO had 2 or more BSI during the study period. The odds of having a BSI documented in the 5 infants with SBS and SBBO were 7.07 times greater than infants with SBS without SBBO (p=0.009) as calculated by logistic regression. Gram-positive organisms were responsible for 9 (45%) of the BSI and Enterococcus fecalis was the etiology in 5 (25%). Klebsiella pneumoniae was the predominant Gram-negative pathogen identified (Table II). E. coli was identified among the mixed organisms cultured. There was no relationship identified between the timing of BSI and diagnosis of SBBO or with enteral feeding tolerance.

Table 2.

Microbes attributed to bloodstream infection (BSI) in children with short bowel syndrome (SBS)

| Organisms | Number of bloodstream infections N=20 (% of total BSI) |

Number of children (N=10) with bloodstream infections due to microorganism (% of children) |

|---|---|---|

| Gram-positive | ||

| Enterococcus faecalis | 5 (25%) | 4 (40%) |

| Coagulase-negative Staphylococci | 3 (15%) | 3 (30%) |

| Leuconostoc spp. | 1 (5%) | 1(10%) |

| Gram-negative | ||

| Klebsiella pneumoniae | 7 (35%) | 4 (40%) |

| *Mixed infections | 4 (20%) | 3 (30%) |

More than one organism isolated from single blood culture

Fecal calprotectin

Fecal calprotectin levels were significantly higher in the children with SBS (median 309 μg/g; range: 205-786 μg/g) compared with healthy age-matched controls (median 61 μg/g; range: 45-214 μg/g); (p=0.003). When further subdivided, children with SBS diagnosed with SBBO had higher fecal calprotectin levels (median 394 μg/g; range 144-786 μg/g) compared with children with SBS without SBBO (median 154 μg/g; range 20-461 μg/g) (p<0.05). There was no clinical evidence of mucosal inflammation (hematochezia, mucus) in the children with elevated fecal calprotectin levels. These levels did not have any significant correlations with the length of the remnant small intestines or quantity of enteral feeds. Fecal calprotectin levels in all of the subjects except for patient #1 (who was referred for liver and small bowel transplantation) decreased over time but the trend was not statistically significant.

Intestinal permeability

The L/M urinary excretion ratio was abnormally increased (>0.025) in all of the children with SBS in which the test was performed compared with previously determined normal ratios (23). There was no difference between the L/M ratio measured in children with SBS and SBBO (median 0.06; range 0.05-0.14) or without SBBO (median 0.06; range 0.03 – 0.29). There was no correlation between this index of intestinal permeability and the proportion of enteral feedings tolerated (R= - 0.47; p=0.8) or fecal calprotectin levels (R=0.24; p=0.4).

Systemic proinflammatory cytokines

Children with SBS demonstrated significantly higher serum concentrations of TNF-α at baseline (median 21.21 pg/ml; range 9.2-41.5 pg/ml) compared with healthy children (median 7 pg/ml; range 5.03-9.06 pg/ml), (p=0.02). TNF-α levels subsequently decreased over time. Serum concentrations of IL-1 β, IL-6 and IL-8 in children with SBS were elevated compared with healthy children but trend was not statistically significant. Serum IL-1 β and IL-6 concentrations decreased from baseline levels in children with SBS over time and were significantly lower at week 16 compared with baseline values (Table III; available at www.jpeds.com). There was a significant inverse relationship between serum concentrations of TNF-α, IL-1 β, IL-6 and IL-8 and the percent of total calories being consumed enterally at the time of blood sampling (Figure). Cytokine levels had a significant linear relationship with the PN components (glucose and intralipids), (data not shown); thus, children with SBS able to tolerate higher amounts of enteral nutrition (and therefore requiring less PN) exhibited lower serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines. There was no association between cytokine levels and residual bowel length or fecal calprotectin.

Table 3.

Proinflammatory cytokine levels (Pg/mL) in children with SBS and age-matched controls1

| TNF alpha | IL-1 beta | IL-6 | IL-8 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy children | 5 ± 1* | 2 ± 1 | 3 ± 1 | 13 ± 11 | |

| SBS children | Baseline | 29 ± 8 | 16 ± 10 | 76 ± 37 | 391 ± 100 |

| Week 8 | 14 ± 2* | 1 ± 1* | 11 ± 4 | 132 ± 22 | |

| Week 162 | 17 ± 3* | 1 ± 1* | 7 ± 2* | 219 ± 86 |

p<0.05 vs. baseline values for children with SBS

Data presented as Mean ± SEM

n=7

Figure.

Association and lines of best fit between serum proinflammatory cytokines. A, TNF alpha; B, IL-1 beta; C, IL-6; and D, IL-8] and percentage of enteral calories.

Antibody response in pediatric SBS

Flagellin or LPS was not detected in the blood of any of the children during the study period. Serum anti-flagellin IgG levels at baseline in the children with SBS were significantly lower than in healthy children. However, these values significantly increased over time in children with SBS (Table IV). There was a significant positive relationship between serum anti-flagellin IgG levels and the percent of total calories consumed (R= 0.58; p=0.003) and with total enteral calorie intake (R=0.69; p<0.001). Serum levels of anti-flagellin IgA were similar in healthy children compared with children with SBS (Table IV). Although there was a trend of increase in anti-flagellin IgA levels from baseline to week 8 and week 16, this was not statistically significant (Table IV). Anti-LPS IgG levels were significantly lower in children with SBS compared with the levels in healthy children (Table IV). These did not change with time and were similar with baseline values at weeks 8 and 16. Anti-LPS Ig A levels did not change over time and were similar in the healthy children and those with SBS.

Table 4.

Flagellin and LPS –specific immunoglobulins (OD) levels (in children with SBS and age -matched controls1)

| Flagellin specific IgG | Flagellin specific IgA | Anti LPS IgG | Anti LPS IgA | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Healthy Children | 0.35 * (0.15 - 0.43) |

0.07 (0.05 - 0.21) |

0.30 * (0.26 - 0.64) |

0.30 (0.02 - 1.41) |

|

| Children with SBS | Baseline | 0.09 (0.01 - 0.66) |

0.06 (0.01 - 0.88) |

0.11 (0.05 - 0.30) |

0.07 (0.02 - 0.61) |

| Week 8 | 0.36* (0.01 - 0.87) |

0.29 (0.01 - 1.1) |

0.08 (0.03 – 0.19) |

0.12 (0.01 - 0.92) |

|

| Week 16 2 | 0.33* (0.02 - 0.81) |

0.27 (0.06 - 1.90) |

0.07 (0.03 – 0.26) |

0.24 (0.01 -52) |

p<0.05 vs. baseline values for children with SBS

Data presented as Median (Min-Max)

n=7

Discussion

The management of children with SBS is complex and expensive (4). Duration of PN and recurrent BSI are among the predictors of survival and overall outcomes previously identified (4, 6, 24). Limited data in children with SBS suggest a high risk for developing SBBO (7, 25). Our study provides novel information regarding an apparent increased risk for BSI in children with SBS and SBBO and the relationship between the route of nutrition and serum proinflammatory cytokine levels.

Although our data are preliminary, the logistic regression model indicates that the odds for developing BSI in our infants with SBS and SBBO was 7 times higher than in those without SBBO, as diagnosed by the breath hydrogen test. The breath hydrogen test, which measures bacterial fermentation products of D-glucose, is relatively sensitive and has been used in children to assess bacterial overgrowth and carbohydrate malabsorption (24, 26). The choice of D-glucose rather than lactulose in children with SBS reduces the false-positive rate, because, glucose is rapidly absorbed by the small intestines (27). Thus in the absence of obtaining jejunal cultures, D-glucose breath hydrogen test is an appropriate diagnostic alternative.

Stool calprotectin has been shown to predict mucosal inflammation in children with chronic and acute gastrointestinal disorders (13, 14). Calprotectin levels were elevated in the stool of infants with SBS diagnosed with SBBO compared with both those without SBBO and healthy controls. The difference in the level of fecal calprotectin between SBBO and non-SBBO afflicted infants with SBS suggests its potential utility for use as a biomarker for SBBO in these children with SBS and supports the diagnosis of SBBO in these children. Although mucosal biopsies were not obtained as part of this protocol, we hypothesize that the increased stool calprotectin level in children with SBBO is due to mucosal inflammation.

Despite being life saving in this population, PN use in SBS is associated with a high rate of BSI as observed in this study (5). The source of the Gram-positive organisms is likely colonization of the indwelling central venous access line. Additionally, the isolation of Gram-negative pathogens including Kl. pneumoniae and E. coli from blood cultures suggests translocation of gut flora as the etiology of BSI. All of the children with SBS studied had abnormally increased intestinal permeability as measured by L/M ratio. This has been hypothesized to result from mucosal atrophy due to the relative lack of enteral feeding and the influence of local or systemic bacterial products such as LPS (23, 28). However, in this study, L/M ratio was not shown to have any association with the proportion of enteral feeding, length of bowel or serum levels of proinflammatory cytokines. Animal models of SBS clearly demonstrate gut barrier dysfunction manifested by bacterial translocation (29). A single pediatric SBS study showed that BSI was correlated temporally with abnormal gut permeability to carbohydrate markers (30). This finding could not be corroborated by our data. Circulating flagellin or LPS in the serum was not detected at the specified study time points. However these products were not measured nor were permeability studies performed concomitantly with obtaining positive blood cultures. Future studies should assess permeability at the time of a positive BSI. It would also be relevant to evaluate the impact of the primary disease (i.e. NEC, atresia, volvulus etc) on intestinal permeability.

We have previously detected intermittent flagellin and LPS and increased specific immunoglobulins to these bacterial mediators in the serum of adults with SBS (11). In contrast, these were not detected in our study subjects, possibly due to the short period of observation and the likely transient nature of presence of these products in the bloodstream. Levels of anti-LPS IgG and flagellin specific IgG antibodies were low in children with SBS compared with the levels in healthy children. These values for flagellin specific IgG and IgA (but not anti-LPS antibodies) increased over time. Enteral nutrition tolerance also was positively associated with the increase in flagellin specific IgG over time. This suggests a pattern of anti-flagellin antibody production that is initially impaired but improves with age and possibly improved intake of enteral nutrition. Massive bowel resection as in these children would be expected to decrease the mass of gut-associated lymphoid tissue (GALT) and may be a factor contributing to the dampened adaptive immune response to bacterial antigens that we observed. Low serum levels of flagellin antibodies also could be due to intestinal protein losses secondary to the massive intestinal resection. However the stools of the children with SBS were not assessed for protein loss nor were their total serum IgG levels measured. In animal models, enteral nutrition (as opposed to PN) enhances gut mucosa-mediated immunity and may be one explanation for the upregulated anti-flagellin antibody titers observed.

This study serially evaluates pro-inflammatory cytokines levels in infants and children after the diagnosis of SBS in relation to enteral feeding over time. The blood cytokine levels exhibited by our patients with post-NEC and SBS, most of whom had one or more BSI during the study is related to decreased enteral nutrition, prolonged PN and SBBO. We observed an inverse relationship between percentage of calories tolerated enterally and the levels of all of the proinflammatory cytokines measured (TNF- α, IL-1β, IL-6 and IL-8). Although the cause and effect relationship of this observation is unclear, it is possible that a relative lack of enteral nutrition and/or provision of PN contribute to the proinflammatory responses observed. This data supports the impact of PN on cytokine levels but does not allow for the identification of any one component (glucose, protein or lipid) as having the greatest impact on serum proinflammatory cytokines. The fall in cytokine levels are hypothesized to be due to the decrease in PN and increase in enteral nutrition. Clinical management did not change significantly in the children after enrollment in the study.

We conclude that children with SBS have a high incidence of BSI and increased blood TNF- α compared with healthy controls. Subjects with SBBO are at higher risk for BSI and have higher levels of fecal calprotectin. Enteral nutrition is inversely associated with levels of blood proinflammatory cytokines and positively associated with anti-flagellin IgG. The primary therapeutic goal for children with SBS and intestinal insufficiency is to eliminate PN and transition to full enteral feeding while achieving adequate anthropometric growth and cognitive development. In light of the clinical importance of SBS, the high healthcare-related costs, and ineffectiveness of current therapy, an increased understanding of the effects of enteral feeding on inflammation and gut mucosa immune responses in this syndrome are urgently needed.

Acknowledgments

We are indebted to Ms. Charletta Thomas (Research coordinator, Emory University), Mr. Dexter Thompson (Laboratory research specialist, Emory University), nursing colleagues, and the infants and their parents for their participation in various aspects of the study. We are also grateful to Dr. Andi L. Shane, Assistant Professor of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases, Emory University School of Medicine, for her thorough review of this manuscript.

Supported in part by National Institutes of Health grants K12 RR017643 and KL2 RR025009 (to CRC), R01 DK55850 and K24 RR023356 (to TRZ), UL1 RR025008 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award program and M01 RR0039 from the General Clinical Research Center program, National Center for Research Resources. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

- BSI

Bloodstream infection

- GCRC

General Clinical Research Center

- Ig

Immunoglobulin

- IL

Interleukin

- LPS

Lipopolysaccharide

- NEC

Necrotizing enterocolitis

- PN

Parenteral nutrition

- SBS

Short bowel syndrome

- SBBO

Small bowel bacterial overgrowth

- TNF-α

Tumor necrosis factor-α

- L/M

Lactulose:mannitol

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schwartz MZ, Maeda K. Short bowel syndrome in infants and children. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1985;32:1265–1279. doi: 10.1016/s0031-3955(16)34904-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cole CR, Hansen NI, Higgins RD, Ziegler TR, Stoll BJ, for the Eunice Kennedy Shriver Neonatal Research Network Very low birth weight preterm infants with surgical short bowel syndrome: Incidence, morbidity and mortality, and growth outcomes at 18 to 22 months. Pediatrics. 2008;122:e573–582. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Beau P, Barrioz T, Ingrand P. Total parenteral nutrition-related cholestatic hepatopathy, is it an infectious disease? Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1994;18:63–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spencer AU, Kovacevich D, McKinney-Barnett M, Hair D, Canham J, Maksym C, et al. Pediatric short-bowel syndrome: the cost of comprehensive care. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;88:1552–1559. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Terra RM, Plopper C, Waitzberg DL, Cukier C, Santoro S, Martins JR, et al. Remaining small bowel length: association with catheter sepsis in patients receiving home total parenteral nutrition: evidence of bacterial translocation. World J Surg. 2000;24:1537–1541. doi: 10.1007/s002680010274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sondheimer JM, Asturias E, Cadnapaphornchai M. Infection and cholestasis in neonates with intestinal resection and long-term parenteral nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1998;27:131–137. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199808000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaufman SS, Loseke CA, Lupo JV, Young RJ, Murray ND, Pinch LW, et al. Influence of bacterial overgrowth and intestinal inflammation on duration of parenteral nutrition in children with short bowel syndrome. J Pediatr. 1997;131:356–361. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(97)80058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shimizu K, Ogura H, Goto M, Asahara T, Nomoto K, Morotomi M, et al. Altered gut flora and environment in patients with severe SIRS. J Trauma. 2006;60:126–133. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000197374.99755.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ziegler TR, Evans ME, Fernandez-Estivariz C, Jones DP. Trophic and cytoprotective nutrition for intestinal adaptation, mucosal repair, and barrier function. Annu Rev Nutr. 2003;23:229–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.23.011702.073036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gewirtz AT. Flag in the crossroads: flagellin modulates innate and adaptive immunity. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006;22:8–12. doi: 10.1097/01.mog.0000194791.59337.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ziegler TR, Luo M, Estivariz CF, Moore DA, III, Sitaraman SV, Hao L, et al. Detectable serum flagellin and lipopolysaccharide and upregulated anti-flagellin and lipopolysaccharide immunoglobulins in human short bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2008;294:R402–410. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00650.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gewirtz AT, Navas TA, Lyons S, Godowski PJ, Madara JL. Cutting edge: bacterial flagellin activates basolaterally expressed TLR5 to induce epithelial proinflammatory gene expression. J Immunol. 2001;167:1882–1885. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.1882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunn SK, Bisset WM, Main MJ, Gray ES, Olson S, Golden BE. Fecal calprotectin: validation as a noninvasive measure of bowel inflammation in childhood inflammatory bowel disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;33:14–22. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200107000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fagerberg UL, Loof L, Myrdal U, Hansson LO, Finkel Y. Colorectal inflammation is well predicted by fecal calprotectin in children with gastrointestinal symptoms. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2005;40:450–455. doi: 10.1097/01.mpg.0000154657.08994.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diamond IR, de Silva N, Pencharz PB, Kim JH, Wales PW. Neonatal short bowel syndrome outcomes after the establishment of the first Canadian multidisciplinary intestinal rehabilitation program: preliminary experience. Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 2007;42:806–811. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Touloukian RJ, Smith GJ. Normal intestinal length in preterm infants. J Pediatr Surg. 1983;18:720–723. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3468(83)80011-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gibson RS. Principles of nutritional assessment. 2nd. New York: Oxford University Press; 2005. Measuring food consumption of individuals; pp. 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- 18.de Boissieu D, Chaussain M, Badoual J, Raymond J, Dupont C. Small-bowel bacterial overgrowth in children with chronic diarrhea, abdominal pain, or both. J Pediatr. 1996;128:203–207. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(96)70390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sigalet DL, Martin G, Meddings J, Hartman B, Holst JJ. GLP-2 levels in infants with intestinal dysfunction. Pediatr Res. 2004;56:371–376. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000134250.80492.EC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ton H, Brandsnes, Dale S, Holtlund J, Skuibina E, Schjonsby H, et al. Improved assay for fecal calprotectin. Clin Chim Acta. 2000;292:41–54. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(99)00206-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perman JA, Modler S, Barr RG, Rosenthal P. Fasting breath hydrogen concentration: normal values and clinical applications. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:1358–1363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sigalet DL, Martin GR, Meddings JB. 3-0 methylglucose uptake as a marker of nutrient absorption and bowel length in pediatric patients. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2004;28:158–162. doi: 10.1177/0148607104028003158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marsilio R, D'Antiga L, Zancan L, Dussini N, Zacchello F. Simultaneous HPLC determination with light-scattering detection of lactulose and mannitol in studies of intestinal permeability in pediatrics. Clinical Chemistry. 1998;44:1685–1691. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cole CR, Ziegler TR. Small bowel bacterial overgrowth: a negative factor in gut adaptation in pediatric SBS. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2007;9:456–462. doi: 10.1007/s11894-007-0059-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vanderhoof JA. New and emerging therapies for short bowel syndrome in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2004;39 3:S769–771. doi: 10.1097/00005176-200406003-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cole CR, Rising R, Lifshitz F. Consequences of incomplete carbohydrate absorption from fruit juice consumption in infants. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:1098–1102. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.10.1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Corazza GR, Menozzi MG, Strocchi A, Rasciti L, Vaira D, Lecchini R, et al. The diagnosis of small bowel bacterial overgrowth. Reliability of jejunal culture and inadequacy of breath hydrogen testing. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:302–309. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90818-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Dwyer ST, Michie HM, Ziegler TR, Revhaug A, Smith RJ, Wilmore DW. A single dose of endotoxin alters intestinal permeability in healthy humans. Archives of Surgery. 1988;123:1459–1464. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1988.01400360029003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian J, Hao L, Chandra P, Jones DP, Williams IR, Gewirtz AT, Ziegler TR. Dietary glutamine and oral antibiotics each improve indices of gut barrier function in rat short bowel syndrome. American Journal of Physiology. 2009;296:G348–355. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90233.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.D'Antiga L, Dhawan A, Davenport M, Mieli-Vergani G, Bjarnason I. Intestinal absorption and permeability in paediatric short-bowel syndrome: a pilot study. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1999;29:588–593. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199911000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]