Abstract

Calcium signals are involved in a large variety of physiological processes. Their

versatility relies on the diversity of spatio-temporal behaviors that the

calcium concentration can display. Calcium entry through inositol

1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP ) receptors (IP

) receptors (IP R's) is a key component that participates in both

local signals such as “puffs” and in global waves. IP

R's) is a key component that participates in both

local signals such as “puffs” and in global waves. IP R's are usually organized in clusters on the membrane

of the endoplasmic reticulum and their spatial distribution has important

effects on the resulting signal. Recent high resolution observations [1] of Ca

R's are usually organized in clusters on the membrane

of the endoplasmic reticulum and their spatial distribution has important

effects on the resulting signal. Recent high resolution observations [1] of Ca puffs offer a window to study intra-cluster organization. The

experiments give the distribution of the number of IP

puffs offer a window to study intra-cluster organization. The

experiments give the distribution of the number of IP R's that open during each puff without much

processing. Here we present a simple model with which we interpret the

experimental distribution in terms of two stochastic processes: IP

R's that open during each puff without much

processing. Here we present a simple model with which we interpret the

experimental distribution in terms of two stochastic processes: IP binding and unbinding and Ca

binding and unbinding and Ca -mediated inter-channel coupling. Depending on the parameters

of the system, the distribution may be dominated by one or the other process.

The transition between both extreme cases is similar to a percolation process.

We show how, from an analysis of the experimental distribution, information can

be obtained on the relative weight of the two processes. The largest distance

over which Ca

-mediated inter-channel coupling. Depending on the parameters

of the system, the distribution may be dominated by one or the other process.

The transition between both extreme cases is similar to a percolation process.

We show how, from an analysis of the experimental distribution, information can

be obtained on the relative weight of the two processes. The largest distance

over which Ca -mediated coupling acts and the density of IP

-mediated coupling acts and the density of IP -bound IP

-bound IP R's of the cluster can also be estimated. The approach

allows us to infer properties of the interactions among the channels of the

cluster from statistical information on their emergent collective behavior.

R's of the cluster can also be estimated. The approach

allows us to infer properties of the interactions among the channels of the

cluster from statistical information on their emergent collective behavior.

Introduction

The calcium (Ca ) ion is a universal second messenger that is involved in a large

number of physiological processes [2]. To this end, cells regulate cytosolic Ca

) ion is a universal second messenger that is involved in a large

number of physiological processes [2]. To this end, cells regulate cytosolic Ca concentration ([Ca

concentration ([Ca ]) very precisely. At basal conditions free cytosolic [Ca

]) very precisely. At basal conditions free cytosolic [Ca ] is very low (

] is very low ( ). [Ca

). [Ca ] is several orders of magnitude higher in the

extracellular medium and in internal reservoirs, such as the endoplasmic reticulum.

Different signals can induce the opening of specific Ca

] is several orders of magnitude higher in the

extracellular medium and in internal reservoirs, such as the endoplasmic reticulum.

Different signals can induce the opening of specific Ca channels located on the plasma membrane or on the membrane of the

internal reservoirs leading to local increments of the cytosolic [Ca

channels located on the plasma membrane or on the membrane of the

internal reservoirs leading to local increments of the cytosolic [Ca ] of various durations. This [Ca

] of various durations. This [Ca ] change evokes different end responses depending upon the

spatio-temporal distribution of [Ca

] change evokes different end responses depending upon the

spatio-temporal distribution of [Ca ]. Thus, it is of interest to measure the latter and how

different factors shape it.

]. Thus, it is of interest to measure the latter and how

different factors shape it.

One of the Ca channels involved in intracellular Ca

channels involved in intracellular Ca signals is the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP

signals is the inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP ) receptor (IP

) receptor (IP R) which is expressed in many cell types and is located at the

surface of intracellular membranes such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the

sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) and the nucleus. The IP

R) which is expressed in many cell types and is located at the

surface of intracellular membranes such as the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), the

sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) and the nucleus. The IP R is biphasically regulated by Ca

R is biphasically regulated by Ca , with a bell-shaped open probability as a function of [Ca

, with a bell-shaped open probability as a function of [Ca ]. Kinetic models of the IP

]. Kinetic models of the IP R take this dual effect into account by assuming that the receptor

has at least one activating and one inhibitory site such that Ca

R take this dual effect into account by assuming that the receptor

has at least one activating and one inhibitory site such that Ca binding to the first one induces channel opening (provided that IP

binding to the first one induces channel opening (provided that IP is also bound to the receptor) and Ca

is also bound to the receptor) and Ca binding to the second one induces channel closing [3]–[5]. Given that the affinity

for Ca

binding to the second one induces channel closing [3]–[5]. Given that the affinity

for Ca of the activating site is larger than that of the inhibitory site,

a local increase of cytosolic Ca

of the activating site is larger than that of the inhibitory site,

a local increase of cytosolic Ca in the vicinity of an IP

in the vicinity of an IP R with IP

R with IP bound induces channel opening first. This leads to a phenomenon

called Ca

bound induces channel opening first. This leads to a phenomenon

called Ca -induced Ca

-induced Ca -release (CICR) because the Ca

-release (CICR) because the Ca ions released by one channel can in turn trigger the opening of

other nearby channels with IP

ions released by one channel can in turn trigger the opening of

other nearby channels with IP bound. Ca

bound. Ca channels are not uniformly distributed in the cell. IP

channels are not uniformly distributed in the cell. IP R's, in particular, are usually organized in clusters on

the membrane of the ER that are separated by a few microns [6]. These clusters have been

estimated to be

R's, in particular, are usually organized in clusters on

the membrane of the ER that are separated by a few microns [6]. These clusters have been

estimated to be  in size in oocytes [7], [8]. The simulations of [7] showed that previous

observations could be reproduced assuming that between 25 and 35 IP

in size in oocytes [7], [8]. The simulations of [7] showed that previous

observations could be reproduced assuming that between 25 and 35 IP R's opened simultaneously during puffs. A similar estimate

was obtained in [8] using a mean-field model that assumed that all

channels opened and closed simultaneously. Simulations that include a stochastic

description of the individual channel openings and closings, however, show that at

most half of the channels with IP

R's opened simultaneously during puffs. A similar estimate

was obtained in [8] using a mean-field model that assumed that all

channels opened and closed simultaneously. Simulations that include a stochastic

description of the individual channel openings and closings, however, show that at

most half of the channels with IP bound are simultaneously open during a puff [8]. This implies that even

in clusters with 50 IP

bound are simultaneously open during a puff [8]. This implies that even

in clusters with 50 IP R's with IP

R's with IP bound, the maximum number of simultaneously open channels is

around 20. These results are consistent with observations of Ca

bound, the maximum number of simultaneously open channels is

around 20. These results are consistent with observations of Ca signals in the human neuroblastoma SY5Y cell line in which puffs

of up to 20 simultaneously open channels were observed [1]. Measurements performed

using patches of the outer nuclear envelope of the DT40 cell line give smaller

numbers of IP

signals in the human neuroblastoma SY5Y cell line in which puffs

of up to 20 simultaneously open channels were observed [1]. Measurements performed

using patches of the outer nuclear envelope of the DT40 cell line give smaller

numbers of IP R's in each patch [9]. The non-uniform

spatial organization of the IP

R's in each patch [9]. The non-uniform

spatial organization of the IP R's together with the channel coupling induced by CICR

gives rise to a large variety of intracellular Ca

R's together with the channel coupling induced by CICR

gives rise to a large variety of intracellular Ca signals that go from very localized ones to waves that propagate

throughout the cell [10].

signals that go from very localized ones to waves that propagate

throughout the cell [10].

The hierarchy of intracellular Ca signals that includes Ca

signals that includes Ca “blips” (Ca

“blips” (Ca release through a single IP

release through a single IP R), “puffs” (Ca

R), “puffs” (Ca release through several IP

release through several IP R's in a cluster) and waves that propagate globally across

cells by successive cycles of CICR has been observed using fluorescence microscopy

and Ca

R's in a cluster) and waves that propagate globally across

cells by successive cycles of CICR has been observed using fluorescence microscopy

and Ca sensitive dyes [10]–[13]. The

Xenopus laevis oocyte has been frequently used for this purpose

because of its relatively large size and because the only Ca

sensitive dyes [10]–[13]. The

Xenopus laevis oocyte has been frequently used for this purpose

because of its relatively large size and because the only Ca channels that are present on the surface of the ER are IP

channels that are present on the surface of the ER are IP R's. Fluorescent images of these signals obtained with

confocal microscopy do not resolve the inner-cluster structure. Therefore, different

modeling strategies have been presented in order to determine the properties of the

dynamics and spatial organization of IP

R's. Fluorescent images of these signals obtained with

confocal microscopy do not resolve the inner-cluster structure. Therefore, different

modeling strategies have been presented in order to determine the properties of the

dynamics and spatial organization of IP R's within clusters that are compatible with these

experimental observations [7], [8], [14], [15]. In

particular, in [8], [16] we made the very simple assumption that the

number of IP

R's within clusters that are compatible with these

experimental observations [7], [8], [14], [15]. In

particular, in [8], [16] we made the very simple assumption that the

number of IP R's that open during the first puff that occurs at a site

is given by the number of IP

R's that open during the first puff that occurs at a site

is given by the number of IP R's with IP

R's with IP bound. The underlying assumption was that the Ca

bound. The underlying assumption was that the Ca released by the first open channel would induce the opening of all

the other IP

released by the first open channel would induce the opening of all

the other IP R's of the cluster with IP

R's of the cluster with IP bound. Therefore, if all the clusters had approximately the same

number of IP

bound. Therefore, if all the clusters had approximately the same

number of IP R's and all IP

R's and all IP R's were equally sensitive to IP

R's were equally sensitive to IP , the distribution of the number of channels that opened during a

puff could be approximated by a binomial or Poisson distribution [8], provided

that the probability that the channels become open were the same immediately before

the occurrence of each puff. This last condition would not be satisfied in a

non-stationary situation, e.g. if the concentrations of the

agonists right before the release event differed significantly from puff to puff. It

would not hold, in particular, for data containing sequences of puffs that are

coupled through CICR or to puffs in which the inhibitory effect of the Ca

, the distribution of the number of channels that opened during a

puff could be approximated by a binomial or Poisson distribution [8], provided

that the probability that the channels become open were the same immediately before

the occurrence of each puff. This last condition would not be satisfied in a

non-stationary situation, e.g. if the concentrations of the

agonists right before the release event differed significantly from puff to puff. It

would not hold, in particular, for data containing sequences of puffs that are

coupled through CICR or to puffs in which the inhibitory effect of the Ca released in a previous event was noticeable, as described in [16]. In

oocytes, the latter is only relevant for very long records containing many puffs at

a site, which is usually not the case in most experiments. Calcium induced calcium

release is also affected by buffers that can trap Ca

released in a previous event was noticeable, as described in [16]. In

oocytes, the latter is only relevant for very long records containing many puffs at

a site, which is usually not the case in most experiments. Calcium induced calcium

release is also affected by buffers that can trap Ca ions as they diffuse. This not only reduces the [Ca

ions as they diffuse. This not only reduces the [Ca ] but also alters the rate of Ca

] but also alters the rate of Ca transport [17]. The distances that separate IP

transport [17]. The distances that separate IP R's within a cluster are very small (10–20nm)

[9].

Thus, only large concentrations of very fast buffers could affect Ca

R's within a cluster are very small (10–20nm)

[9].

Thus, only large concentrations of very fast buffers could affect Ca -mediated inter-channel coupling in cases with many active channels

[18],

[19].

The assumption that all the channels with IP

-mediated inter-channel coupling in cases with many active channels

[18],

[19].

The assumption that all the channels with IP bound participate of the first puff of their site is the simplest

way of approaching the complex problem of Ca

bound participate of the first puff of their site is the simplest

way of approaching the complex problem of Ca -mediated inter-channel communication. Yet, it is applicable as

long as the distance between IP

-mediated inter-channel communication. Yet, it is applicable as

long as the distance between IP -bound channels is not too large. In the present paper we drop this

assumption and analyze how Ca

-bound channels is not too large. In the present paper we drop this

assumption and analyze how Ca -mediated inter-channel coupling affects the distribution of puff

sizes. Our approach provides a simple tool to study some of the effects of buffers

on the intra-cluster dynamics.

-mediated inter-channel coupling affects the distribution of puff

sizes. Our approach provides a simple tool to study some of the effects of buffers

on the intra-cluster dynamics.

The quantal properties of Ca release during puffs have recently been revealed in [1] using

total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy in intact mammalian cells

of the human neuroblastoma SY5Y cell line. The proximity of IP

release during puffs have recently been revealed in [1] using

total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy in intact mammalian cells

of the human neuroblastoma SY5Y cell line. The proximity of IP R's to the plasma membrane in this cell type allowed the

use of TIRF microscopy in which fluorescence can be elicited in a very small

(attoliter) volume. This, together with the use of a fast CCD camera, permitted a

much better temporal resolution than the one achieved with confocal microscopy. In

this way, abrupt step-wise transitions between fluorescence levels were observed

during the falling phase of puffs. Furthermore, many puffs could be elicited at each

release site due to the use of a membrane-permeable form of IP

R's to the plasma membrane in this cell type allowed the

use of TIRF microscopy in which fluorescence can be elicited in a very small

(attoliter) volume. This, together with the use of a fast CCD camera, permitted a

much better temporal resolution than the one achieved with confocal microscopy. In

this way, abrupt step-wise transitions between fluorescence levels were observed

during the falling phase of puffs. Furthermore, many puffs could be elicited at each

release site due to the use of a membrane-permeable form of IP [20]. The

authors then inferred that the step-wise transitions between fluorescence levels

occurred in multiples of a basic unit that they identified with the amplitude

contribution of each channel at the site [1]. Using this relationship

they could readily obtain the distribution of the number of channels that open

during a puff. Given that there is a large variability among cluster sites, they

analyzed the subset of events that occur in clusters with a similar number of IP

[20]. The

authors then inferred that the step-wise transitions between fluorescence levels

occurred in multiples of a basic unit that they identified with the amplitude

contribution of each channel at the site [1]. Using this relationship

they could readily obtain the distribution of the number of channels that open

during a puff. Given that there is a large variability among cluster sites, they

analyzed the subset of events that occur in clusters with a similar number of IP R's. The authors did not find any sign of an inhibiting

effect of the Ca

R's. The authors did not find any sign of an inhibiting

effect of the Ca released in their records. In spite of that and even constraining

the data set as mentioned before, they found that a Poisson distribution failed to

reproduce the observed histogram of event sizes particularly in the region of small

events (i.e., puffs with very few open channels). They could

approximately describe the distribution with a model that assumes a weak

cooperativity among channels. Inter-channel cooperativity is mediated by the Ca

released in their records. In spite of that and even constraining

the data set as mentioned before, they found that a Poisson distribution failed to

reproduce the observed histogram of event sizes particularly in the region of small

events (i.e., puffs with very few open channels). They could

approximately describe the distribution with a model that assumes a weak

cooperativity among channels. Inter-channel cooperativity is mediated by the Ca released through an open IP

released through an open IP R that subsequently diffuses to a neighboring channel. Thus, the

distance between channels is a key factor that regulates the cooperativity strength

[21]. The approach of [1], however, does not take

space into account.

R that subsequently diffuses to a neighboring channel. Thus, the

distance between channels is a key factor that regulates the cooperativity strength

[21]. The approach of [1], however, does not take

space into account.

In the present paper we introduce a simple model that takes into account both the

stochasticity due to IP binding and the distance-dependent Ca

binding and the distance-dependent Ca -mediated cooperativity. It can reproduce the event size

distribution reported in [1] for events involving any number of open channels.

The distribution obtained with our model approaches a binomial or Poisson

distribution as the cooperativity strength increases so that the opening of one IP

-mediated cooperativity. It can reproduce the event size

distribution reported in [1] for events involving any number of open channels.

The distribution obtained with our model approaches a binomial or Poisson

distribution as the cooperativity strength increases so that the opening of one IP R induces the opening of all other IP

R induces the opening of all other IP R's with IP

R's with IP bound. This transition from Ca

bound. This transition from Ca -dominated to IP

-dominated to IP -binding dominated stochasticity is similar to a percolation

transition. It also occurs if the number of IP

-binding dominated stochasticity is similar to a percolation

transition. It also occurs if the number of IP R's with IP

R's with IP bound increases. Therefore, the transition can be reflected on the

distribution of the number of IP

bound increases. Therefore, the transition can be reflected on the

distribution of the number of IP R's that open at a given release site.

R's that open at a given release site.

Percolation in connection with Ca signals has been invoked to explain the transition from abortive

to propagating waves in cells [22]–[24]. Our paper is the

first to identify two limiting regimes of the intra-cluster dynamics that underlies

puffs and to characterize the change between them as a percolation transition.

Furthermore, we show how information on the transition between both regimes (the IP

signals has been invoked to explain the transition from abortive

to propagating waves in cells [22]–[24]. Our paper is the

first to identify two limiting regimes of the intra-cluster dynamics that underlies

puffs and to characterize the change between them as a percolation transition.

Furthermore, we show how information on the transition between both regimes (the IP -binding and the Ca

-binding and the Ca dominated behaviors) can be extracted from the distribution of the

number of IP

dominated behaviors) can be extracted from the distribution of the

number of IP R's that open during a puff. Knowledge on this transition

can, in turn, yield information on the largest distance over which Ca

R's that open during a puff. Knowledge on this transition

can, in turn, yield information on the largest distance over which Ca -mediated cooperativity acts and on the mean density of IP

-mediated cooperativity acts and on the mean density of IP -bound IP

-bound IP R's of the clusters. In this way, we can estimate

biophysical parameters that affect the intra-cluster dynamics from statistical

information on the emergent collective behavior of the channels of the cluster.

R's of the clusters. In this way, we can estimate

biophysical parameters that affect the intra-cluster dynamics from statistical

information on the emergent collective behavior of the channels of the cluster.

The aim of the simple model that we introduce in this paper is to characterize the

basic mechanisms that shape the distribution of the number of channels that open

during puffs. In particular, we identify the competition between two stochastic

processes as the main determinant of the form of the distribution. Therefore, an

analysis of this form may give information on the relative weight of the two

competing processes. The model does not include a detailed description of the

dynamics that takes place during or between events. For some time most models of

intracellular Ca dynamics were deterministic (see e.g.

[25]).

The observation of local signals such as puffs led to the development of several

models that included a stochastic description of Ca

dynamics were deterministic (see e.g.

[25]).

The observation of local signals such as puffs led to the development of several

models that included a stochastic description of Ca release [14], [15], [26], [27] or of the spatial location of the IP

release [14], [15], [26], [27] or of the spatial location of the IP R's [28]. It is currently clear that stochastic effects

are not only relevant for local release events but are a fundamental aspect of the Ca

R's [28]. It is currently clear that stochastic effects

are not only relevant for local release events but are a fundamental aspect of the Ca dynamics for the full range of observed signals, including waves

[29]–[32]. More information on

stochastic models of Ca

dynamics for the full range of observed signals, including waves

[29]–[32]. More information on

stochastic models of Ca signals can be found in a recent focus issue on the subject [33].

Simulations of these stochastic dynamic models could be used to probe the main

findings of the present paper.

signals can be found in a recent focus issue on the subject [33].

Simulations of these stochastic dynamic models could be used to probe the main

findings of the present paper.

Results

The Model

We introduce here a simple model to describe the distribution of puff sizes that

occur at sites with similar numbers of IP R's. The model is simple in the sense that it does not

include a detailed description of the dynamics of the individual channel

openings and closings or of IP

R's. The model is simple in the sense that it does not

include a detailed description of the dynamics of the individual channel

openings and closings or of IP or Ca

or Ca binding and unbinding. However, it does include the

stochasticity associated to IP

binding and unbinding. However, it does include the

stochasticity associated to IP binding and channel coupling via CICR. Given the estimates of

[8], the model assumes that clusters occupy a fixed

size region (more specifically, a circle of radius,

binding and channel coupling via CICR. Given the estimates of

[8], the model assumes that clusters occupy a fixed

size region (more specifically, a circle of radius,  ) and that

) and that  IP

IP R's are randomly distributed over the cluster region

with uniform probability. Each IP

R's are randomly distributed over the cluster region

with uniform probability. Each IP R of the cluster has a probability

R of the cluster has a probability  of having IP

of having IP bound.

bound.  is the random variable that represents the number of available IP

is the random variable that represents the number of available IP R's (i.e., of IP

R's (i.e., of IP R's with IP

R's with IP bound) of the cluster before a puff starts. The distribution

of this variable is a binomial of parameters

bound) of the cluster before a puff starts. The distribution

of this variable is a binomial of parameters  and

and  , that can be approximated by a Poisson distribution of

parameter

, that can be approximated by a Poisson distribution of

parameter  for

for  large and

large and  small enough (for example, with

small enough (for example, with  and

and  the absolute difference between both cumulative distributions

is lower than

the absolute difference between both cumulative distributions

is lower than  for each

for each  ). The model considers that if an IP

). The model considers that if an IP R with IP

R with IP bound becomes open and Ca

bound becomes open and Ca starts to flow through its pore all other IP

starts to flow through its pore all other IP R's with IP

R's with IP bound that are within a distance,

bound that are within a distance,  , of the open IP

, of the open IP R will also become open. These newly opened IP

R will also become open. These newly opened IP R's in turn trigger the opening of new IP

R's in turn trigger the opening of new IP R's with IP

R's with IP bound that are within the distance,

bound that are within the distance,  , from an open one. This scheme triggers a cascade of openings

that stops when there are no more available IP

, from an open one. This scheme triggers a cascade of openings

that stops when there are no more available IP R's within the radius of influence

(i.e., the distance

R's within the radius of influence

(i.e., the distance  ) of any open IP

) of any open IP R. This cascade determines the number,

R. This cascade determines the number,  , of channels that open during a puff. We call

, of channels that open during a puff. We call  the probability that there are

the probability that there are  available IP

available IP R's (with IP

R's (with IP bound) in a cluster and

bound) in a cluster and  the conditional probability that

the conditional probability that  channels open during an event given that there are

channels open during an event given that there are  with IP

with IP bound in the cluster. Given that we are interested in the

distribution of event sizes, we only consider the situations for which

bound in the cluster. Given that we are interested in the

distribution of event sizes, we only consider the situations for which  . Therefore, we renormalize the probabilities so that

. Therefore, we renormalize the probabilities so that  and

and  . In this way,

. In this way,  is a binomial or a Poisson distribution divided by one minus

the probability that there are not IP

is a binomial or a Poisson distribution divided by one minus

the probability that there are not IP R's with IP

R's with IP bound in the cluster. Using these renormalized versions of

bound in the cluster. Using these renormalized versions of  and

and  , the probability,

, the probability,  , of having a puff with

, of having a puff with  open channels is given by:

open channels is given by:

| (1) |

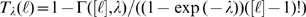

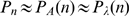

is approximated by a Poisson distribution of parameter

is approximated by a Poisson distribution of parameter  when

when  .

.  can be readily compared with distributions obtained from

experimental observations as the one displayed in Fig. 4D of [1].

can be readily compared with distributions obtained from

experimental observations as the one displayed in Fig. 4D of [1].

Factors That Shape the Distribution of Event Sizes

The two stochastic components of the model are evident in the expression of  .

.  reflects the stochasticity of IP

reflects the stochasticity of IP binding and

binding and  the one due to inter-channel coupling via CICR. The relative

weight of both factors on the resulting

the one due to inter-channel coupling via CICR. The relative

weight of both factors on the resulting  depends on the relationship between two typical lengthscales

of the problem: the radius of influence,

depends on the relationship between two typical lengthscales

of the problem: the radius of influence,  (the maximum distance between channels at which CICR still

works) and the mean distance between channels with IP

(the maximum distance between channels at which CICR still

works) and the mean distance between channels with IP bound,

bound,  , which is a random variable that can be computed in terms of

, which is a random variable that can be computed in terms of  and the number of IP

and the number of IP R's with IP

R's with IP bound,

bound,  , as:

, as:

| (2) |

can take values between

can take values between  and

and  . Closely related to

. Closely related to  is the density of available IP

is the density of available IP R's which is given by:

R's which is given by:

| (3) |

and

and  are related by:

are related by:  .

.

The relationship between  and

and  determines the relative weight of both stochastic components

on

determines the relative weight of both stochastic components

on  . In particular, if

. In particular, if  is very large, the opening of any channel of the cluster will

eventually lead to the opening of all other available channels. If such a

situation holds for most events, then

is very large, the opening of any channel of the cluster will

eventually lead to the opening of all other available channels. If such a

situation holds for most events, then  and

and  will mainly be determined by the stochastic component due to IP

will mainly be determined by the stochastic component due to IP binding, i.e.,

binding, i.e.,  . If, for most events,

. If, for most events,  is very small, then most of

is very small, then most of  will be concentrated near

will be concentrated near  , regardless of how many available IP

, regardless of how many available IP R's there are in each realization. We will refer to

both extreme behaviors as IP

R's there are in each realization. We will refer to

both extreme behaviors as IP or Ca

or Ca limited. Depending on the parameters of the model (

limited. Depending on the parameters of the model ( ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  ), one or the other situation is favored. However, in many

situations one or the other behavior is favored depending on the value of

), one or the other situation is favored. However, in many

situations one or the other behavior is favored depending on the value of  , i.e., on the realization. In those cases,

the dominant stochastic component of

, i.e., on the realization. In those cases,

the dominant stochastic component of  depends on the value of

depends on the value of  .

.

We first illustrate how the distribution,  , varies with the number of IP

, varies with the number of IP R's of the cluster,

R's of the cluster,  , while all other parameters are fixed. As

, while all other parameters are fixed. As  increases, the most likely values that

increases, the most likely values that  can take on also increase. This means that it is more probable

to have more available IP

can take on also increase. This means that it is more probable

to have more available IP R's at any given instance. On the other hand, since

the spatial dimensions of the cluster are unchanged (

R's at any given instance. On the other hand, since

the spatial dimensions of the cluster are unchanged ( is fixed) the mean distance between available IP

is fixed) the mean distance between available IP R's,

R's,  , is more likely to be smaller (see Eq. 2). Given that the

typical distance for CICR to occur,

, is more likely to be smaller (see Eq. 2). Given that the

typical distance for CICR to occur,  , is also fixed, it is more probable that

, is also fixed, it is more probable that  be larger. Therefore,

be larger. Therefore,  approaches

approaches  as

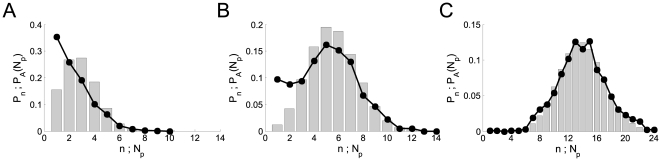

as  is increased. This is illustrated in Fig. 1 where we have plotted the

distributions

is increased. This is illustrated in Fig. 1 where we have plotted the

distributions  (solid circles) and

(solid circles) and  (bars) obtained with 1000 realizations of our model using

(bars) obtained with 1000 realizations of our model using  ,

,  ,

,  and three values of

and three values of  . In A,

. In A,  , the number of available channels is small for most

realizations (its mean value is

, the number of available channels is small for most

realizations (its mean value is  ) so that

) so that  is dominated by inter-channel Ca

is dominated by inter-channel Ca -coupling and concentrated around small values of

-coupling and concentrated around small values of  . In C,

. In C,  , the number of available channels is large for most

realizations (its mean value is

, the number of available channels is large for most

realizations (its mean value is  ) so that

) so that  is typically smaller than

is typically smaller than  (

( ). In this case,

). In this case,  is dominated by the IP

is dominated by the IP -binding stochasticity and almost indistinguishable from the

distribution of available channels,

-binding stochasticity and almost indistinguishable from the

distribution of available channels,  . The example of Fig. 1 B corresponds to a situation in between these two extreme

cases with

. The example of Fig. 1 B corresponds to a situation in between these two extreme

cases with  . We can observe how, as the number of available channels is

more likely to be larger,

. We can observe how, as the number of available channels is

more likely to be larger,  approaches

approaches  . We also observe that for

. We also observe that for  and

and  ,

,  and

and  differ mainly in the region of small values of

differ mainly in the region of small values of  . This occurs because it is difficult for one open channel to

induce the opening of another one if the mean inter-channel distance is large.

Thus, if

. This occurs because it is difficult for one open channel to

induce the opening of another one if the mean inter-channel distance is large.

Thus, if  is small it is very rare that all available channels become

open. In this way, the relative frequency of small events becomes larger than

the fraction of instances with a small number of available channels.

is small it is very rare that all available channels become

open. In this way, the relative frequency of small events becomes larger than

the fraction of instances with a small number of available channels.

Figure 1. Distribution of puff sizes: transition between Ca -dominated to IP

-dominated to IP -binding dominated stochasticity.

-binding dominated stochasticity.

Solid circles: distribution of puff sizes,  , obtained with our model for

, obtained with our model for  ,

,  ,

,  and three values of

and three values of  :

:  (A),

(A),  (B) and

(B) and  (C). Histograms (in grey): corresponding distributions

of available channels,

(C). Histograms (in grey): corresponding distributions

of available channels,  for the same parameter values. All distributions were

computed from 1000 realizations for each set of parameters.

for the same parameter values. All distributions were

computed from 1000 realizations for each set of parameters.

A transition from Ca -dominated to IP

-dominated to IP -binding dominated stochasticity also occurs as

-binding dominated stochasticity also occurs as  is increased, while all other parameters are fixed. In this

case,

is increased, while all other parameters are fixed. In this

case,  remains unchanged and so does the mean distance between

available IP

remains unchanged and so does the mean distance between

available IP R's,

R's,  . By changing

. By changing  it is possible to go from a situation in which

it is possible to go from a situation in which  is small for most events and

is small for most events and  is Ca

is Ca -limited to a situation in which

-limited to a situation in which  is large and

is large and  is IP

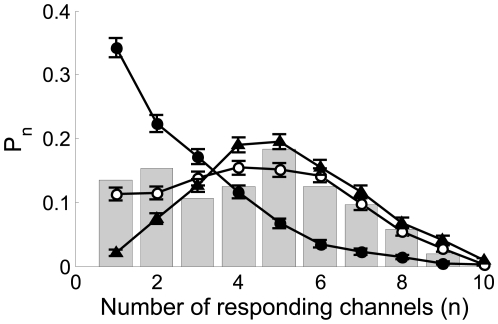

is IP -binding limited. This is illustrated in Fig. 2 where we have plotted the distribution

of event sizes that we obtain with our model for three different values of

-binding limited. This is illustrated in Fig. 2 where we have plotted the distribution

of event sizes that we obtain with our model for three different values of  . For

. For  , the distribution is Ca

, the distribution is Ca -coupling limited and is concentrated around

-coupling limited and is concentrated around  . As

. As  is increased, the relative frequency of events with small

is increased, the relative frequency of events with small  decreases. For

decreases. For  , the distribution is IP

, the distribution is IP -binding limited. In this example,

-binding limited. In this example,  is well approximated by a Poisson distribution of parameter

is well approximated by a Poisson distribution of parameter  (data not shown). The situation in between these extreme cases

corresponds to

(data not shown). The situation in between these extreme cases

corresponds to  and is able to reproduce reasonably well the experimental

distribution of Fig. 4D of

[1]

(superimposed with bars in Fig.

2).

and is able to reproduce reasonably well the experimental

distribution of Fig. 4D of

[1]

(superimposed with bars in Fig.

2).

Figure 2. Distribution of puff sizes: change of behavior with the radius of influence and comparison with observations.

We show the probabiliy,  , of having a puff with

, of having a puff with  open channels obtained with our model for

open channels obtained with our model for  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  (solid circles),

(solid circles),  (open circles) and

(open circles) and  (triangles). Each curve corresponds to 500

realizations of the model. We observe a transition from a Ca

(triangles). Each curve corresponds to 500

realizations of the model. We observe a transition from a Ca -dominated to a IP

-dominated to a IP -binding dominated stochasticity distribution as

-binding dominated stochasticity distribution as  increases. Superimposed with bars: experimental data

taken from Fig. 4D

of [1].

increases. Superimposed with bars: experimental data

taken from Fig. 4D

of [1].

In the Ca limited behavior the number of open channels,

limited behavior the number of open channels,  , is small for most events, regardless of the value of

, is small for most events, regardless of the value of  . This implies

. This implies  for almost all events. In the IP

for almost all events. In the IP -binding limited behavior all available IP

-binding limited behavior all available IP R's become open (

R's become open ( in most cases). Therefore, in order to analyze the transition

between the Ca

in most cases). Therefore, in order to analyze the transition

between the Ca -dominated to IP

-dominated to IP -binding dominated stochasticity, we study how often events

occur for which all available IP

-binding dominated stochasticity, we study how often events

occur for which all available IP R's become open. This happens trivially for events

with

R's become open. This happens trivially for events

with  . Here we are interested in situations with

. Here we are interested in situations with  . To this end, we compute numerically the probability that all

available IP

. To this end, we compute numerically the probability that all

available IP R's,

R's,  , become open,

, become open,  , which is a function of

, which is a function of  and of only one independent parameter, the dimensionless

radius of influence,

and of only one independent parameter, the dimensionless

radius of influence,  , (see Methods). We plot

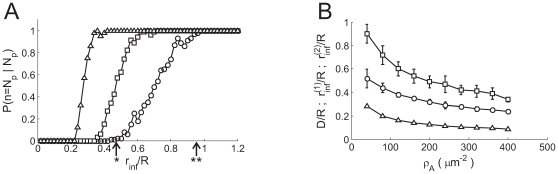

in Fig. 3 A

, (see Methods). We plot

in Fig. 3 A

as a function of

as a function of  , for

, for  (circles),

(circles),  (squares) and

(squares) and  (triangles). As expected,

(triangles). As expected,  is an increasing function of

is an increasing function of  for each value of

for each value of  . We also observe that

. We also observe that  is an increasing (sigmoidal-like) function of

is an increasing (sigmoidal-like) function of  that goes from 0 (i.e.

that goes from 0 (i.e.

in almost all cases, which corresponds to Ca

in almost all cases, which corresponds to Ca -dominated stochasticity) to 1 (i.e.

-dominated stochasticity) to 1 (i.e.

in almost all cases, which corresponds to IP

in almost all cases, which corresponds to IP -binding dominated stochasticity) and that such transition

occurs over a smaller interval of

-binding dominated stochasticity) and that such transition

occurs over a smaller interval of  values the larger

values the larger  is.

is.

Figure 3. Percolation transition: when all available channels open during a puff.

A: Probability that all available IP R's become open,

R's become open,  , as a function of the dimensionless radius of

influence,

, as a function of the dimensionless radius of

influence,  , for

, for  (circles),

(circles),  (squares) and

(squares) and  (triangles). B:

(triangles). B:  (circles),

(circles),  (squares) and

(squares) and  (triangles) as functions of

(triangles) as functions of  . The values of

. The values of  and

and  for the case with

for the case with  are indicated in A with one and two asterisks,

respectively.

are indicated in A with one and two asterisks,

respectively.

We can think of the Ca -limited and the IP

-limited and the IP -binding limited situations as two phases and the transition

between them as a phase transition in the limit of very large

-binding limited situations as two phases and the transition

between them as a phase transition in the limit of very large  . This percolation-like transition occurs at a well defined

value of

. This percolation-like transition occurs at a well defined

value of  in this limit. For finite values of

in this limit. For finite values of  we introduce two quantities,

we introduce two quantities,  and

and  , that determine the type of regime that we can expect (Ca

, that determine the type of regime that we can expect (Ca -limited if

-limited if  or IP

or IP -binding limited if

-binding limited if  ) for each value of

) for each value of  (see Methods). The arrows

in Fig. 3 A indicate the

values of

(see Methods). The arrows

in Fig. 3 A indicate the

values of  (*) and

(*) and  (**) for the

(**) for the  case. We show in Fig. 3 B plots of

case. We show in Fig. 3 B plots of  ,

,  and

and  as functions of

as functions of  (Eq. (3)). It is important to note that these curves are the

same, regardless of the specific parameter values of the model. We observe that

all of them are decreasing functions of

(Eq. (3)). It is important to note that these curves are the

same, regardless of the specific parameter values of the model. We observe that

all of them are decreasing functions of  or, equivalently, of

or, equivalently, of  .

.  is a stochastic variable that changes from realization to

realization. Therefore, even for a given cluster (characterized by fixed values

of

is a stochastic variable that changes from realization to

realization. Therefore, even for a given cluster (characterized by fixed values

of  ,

,  and

and  )

)  and

and  may take on different values depending on the realization. In

this way, depending on

may take on different values depending on the realization. In

this way, depending on  and the values that

and the values that  may take on, a subset of the events that occur at a cluster

may be IP

may take on, a subset of the events that occur at a cluster

may be IP -binding limited (those for which

-binding limited (those for which  ) while others are not. An analogous situation may hold

regarding the Ca

) while others are not. An analogous situation may hold

regarding the Ca -limited behavior. Furthermore, for some clusters, the Ca

-limited behavior. Furthermore, for some clusters, the Ca -limited condition may hold for some events and the IP

-limited condition may hold for some events and the IP -binding limited for others. If the parameters

-binding limited for others. If the parameters  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  are such that most realizations satisfy

are such that most realizations satisfy  , then most events will be IP

, then most events will be IP -binding limited. This happens if

-binding limited. This happens if  or

or  are large enough, in which case the distribution of event

sizes,

are large enough, in which case the distribution of event

sizes,  , approaches the distribution of available channels,

, approaches the distribution of available channels,  .

.

Observing Percolation as a Function of Event Size

The results of Fig. 3 B imply

that there are clusters that can display different types of behaviors depending

on the event. For these clusters, we expect to find, in their distribution,  , a trace of the transition to the limiting behavior that they

can display. Here we are interested in the percolation transition,

i.e., the transition to the IP

, a trace of the transition to the limiting behavior that they

can display. Here we are interested in the percolation transition,

i.e., the transition to the IP -binding dominated stochasticity. As already discussed, the

larger

-binding dominated stochasticity. As already discussed, the

larger  the more likely it is that all IP

the more likely it is that all IP R's become open during the puff (see Fig. 3 A). Thus, the

transition to the IP

R's become open during the puff (see Fig. 3 A). Thus, the

transition to the IP -binding dominated stochasticity should occur as

-binding dominated stochasticity should occur as  and, consequently,

and, consequently,  become larger. To study this transition we consider a cluster

with fixed parameters

become larger. To study this transition we consider a cluster

with fixed parameters  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  (or

(or  in the Poisson limit) and define

in the Poisson limit) and define  as the minimum value of

as the minimum value of  such that

such that  . The definition of

. The definition of  is based on the conditional probability,

is based on the conditional probability,  , which is independent of

, which is independent of  . In cases with finite

. In cases with finite  ,

,  is meaningful provided that it be smaller than

is meaningful provided that it be smaller than  . Since

. Since  decreases with

decreases with  (see Fig. 3

B), taking into account the definitions of

(see Fig. 3

B), taking into account the definitions of  and of

and of  (see Methods) we conclude

that

(see Methods) we conclude

that  and

and  for all

for all  . Thus, we can approximate:

. Thus, we can approximate:

| (4) |

with less than 10% error. Inserting this approximation in Eq. (1) we obtain:

| (5) |

| (6) |

We then conclude that the  tail of

tail of  corresponds to IP

corresponds to IP -binding dominated events. Therefore, it should be possible to

approximate it by a (renormalized) binomial (provided that

-binding dominated events. Therefore, it should be possible to

approximate it by a (renormalized) binomial (provided that  ) or Poisson distribution in the region of large

) or Poisson distribution in the region of large  . The left border of this IP

. The left border of this IP dominated behavior,

dominated behavior,  , gives information on

, gives information on  , i.e. on the maximum distance for which

CICR-coupling can work effectively. Therefore, it should be possible to estimate

, i.e. on the maximum distance for which

CICR-coupling can work effectively. Therefore, it should be possible to estimate  by analyzing

by analyzing  , i.e., to infer a biophysical parameter that

characterizes the intra-cluster dynamics from statistical information on the

emergent collective behavior of the channels of the cluster.

, i.e., to infer a biophysical parameter that

characterizes the intra-cluster dynamics from statistical information on the

emergent collective behavior of the channels of the cluster.

Determining Intra-Cluster Properties from Observations of the Cluster as a Whole

We now discuss how we can estimate  from an experimental distribution of event sizes,

from an experimental distribution of event sizes,  . For the sake of simplicity, we assume that

. For the sake of simplicity, we assume that  can be approximated by a renormalized Poisson distribution,

can be approximated by a renormalized Poisson distribution,  , of unknown parameter

, of unknown parameter  . The goal of this section is to provide a way to estimate

. The goal of this section is to provide a way to estimate  and

and  , the value of

, the value of  at which

at which  and

and  depart from one another (see Eq. (6)). Once

depart from one another (see Eq. (6)). Once  is inferred, we estimate

is inferred, we estimate  as

as  using the function displayed in Fig. 3 B. To this end, we focus on the large

using the function displayed in Fig. 3 B. To this end, we focus on the large  tails of

tails of  and

and  by computing the complementary cumulative distribution functions:

by computing the complementary cumulative distribution functions:

| (7) |

| (8) |

for  . Given that

. Given that  is proportional to a Poisson distribution, there is an

analytic expression for

is proportional to a Poisson distribution, there is an

analytic expression for  . Namely,

. Namely,  , where

, where  is the incomplete

is the incomplete  function and

function and  is the integer part of

is the integer part of  . If the cluster is such that

. If the cluster is such that  exists so that

exists so that  is larger than

is larger than  for

for  and it is smaller otherwise, then, according to the

calculation of the previous section,

and it is smaller otherwise, then, according to the

calculation of the previous section,  for

for  . Therefore, the complementary cumulative distribution

functions of Eqs. (7)–(8) also satisfy

. Therefore, the complementary cumulative distribution

functions of Eqs. (7)–(8) also satisfy  for

for  .

.

We now describe how to estimate  and

and  . The aim is to obtain a (renormalized) Poisson distribution,

. The aim is to obtain a (renormalized) Poisson distribution,  that can approximate

that can approximate  in the large

in the large  region. If we find it, we assume that it is a good

approximation of the distribution of available channels,

region. If we find it, we assume that it is a good

approximation of the distribution of available channels,  . As illustrated in Fig. 1, the mean value,

. As illustrated in Fig. 1, the mean value,  that is obtained using the experimental distribution,

that is obtained using the experimental distribution,  , is smaller than the one that would be obtained if

, is smaller than the one that would be obtained if  was used instead. On the other hand, if

was used instead. On the other hand, if  is a good approximation of

is a good approximation of  in the large

in the large  region, then the mean value obtained with

region, then the mean value obtained with  should be smaller than the size of the largest observed event,

should be smaller than the size of the largest observed event,  . This implies that

. This implies that

| (9) |

if  can be approximated by a renormalized Poisson distribution of

parameter

can be approximated by a renormalized Poisson distribution of

parameter  . Therefore, we look for the best

. Therefore, we look for the best  within a finite set of renormalized Poisson distributions of

parameters

within a finite set of renormalized Poisson distributions of

parameters  satisfying (9). In order to estimate

satisfying (9). In order to estimate  from the observations the relevant quantity that we need to

obtain is

from the observations the relevant quantity that we need to

obtain is  , which is an integer. For this purpose, it is possible to use

a rather coarse grid of

, which is an integer. For this purpose, it is possible to use

a rather coarse grid of  values within the interval defined in (9). In particular, we

have mainly used integer values of

values within the interval defined in (9). In particular, we

have mainly used integer values of  obtaining good results. Once the values

obtaining good results. Once the values  are chosen, we compute the complementary cumulative

distribution functions,

are chosen, we compute the complementary cumulative

distribution functions,  given by (8) for each

given by (8) for each  and

and  . We then calculate the error of approximating

. We then calculate the error of approximating  by

by  over the interval

over the interval  as a function of

as a function of  :

:

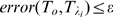

| (10) |

We set a threshold for the error,  , and choose

, and choose  for each

for each  as the smallest value of

as the smallest value of  for which

for which  . Finally, we choose the best

. Finally, we choose the best  as the one with the smallest

as the one with the smallest  .

.

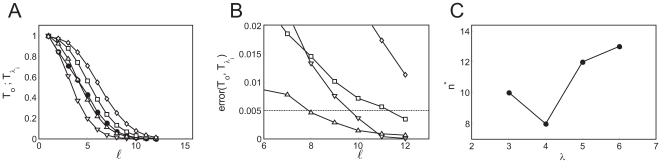

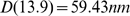

The procedure is illustrated in Fig.

4 where the “experimental” distribution comes

from a simulation of our model with  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  . In this case,

. In this case,  . We show in Fig.

4 A the complementary cumulative distribution functions and in Fig. 4 B the errors for the

values of

. We show in Fig.

4 A the complementary cumulative distribution functions and in Fig. 4 B the errors for the

values of  that we have considered:

that we have considered:  (inverted triangles),

(inverted triangles),  (triangles),

(triangles),  (squares) and

(squares) and  (rhombes). Larger values of

(rhombes). Larger values of  give very bad approximations and are not shown. We show in

Fig. 4 C the values,

give very bad approximations and are not shown. We show in

Fig. 4 C the values,  , obtained for each

, obtained for each  using the threshold,

using the threshold,  (shown with a horizontal line in Fig. 4 B). In this example, the best value is

(shown with a horizontal line in Fig. 4 B). In this example, the best value is  for which

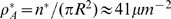

for which  . We estimate the density of IP

. We estimate the density of IP -bound IP

-bound IP R's at which the departure between the experimental

and the Poisson distribution occurs as

R's at which the departure between the experimental

and the Poisson distribution occurs as  , where we have used

, where we have used  . Using the

. Using the

relationship displayed in Fig. 3 B, we estimate

relationship displayed in Fig. 3 B, we estimate  from which we get

from which we get  . This provides an estimate of the radius of influence which

compares very well with the value that was used to generate the data,

. This provides an estimate of the radius of influence which

compares very well with the value that was used to generate the data,  . Using the same procedure, we analyzed the data presented in

Fig. 4D of [1] and

obtained

. Using the same procedure, we analyzed the data presented in

Fig. 4D of [1] and

obtained  assuming

assuming  .

.

Figure 4. Change of behavior with event size.

A:  for data obtained with our model using

for data obtained with our model using  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  (solid circles). Complementary cumulative Poisson

distributions,

(solid circles). Complementary cumulative Poisson

distributions,  , for

, for  (inverted triangles),

(inverted triangles),  (triangles),

(triangles),  (squares),

(squares),  (rhombes). B: Error of approximating

(rhombes). B: Error of approximating  by the various

by the various  for

for  (see text for definition) as a function of

(see text for definition) as a function of  . Symbols are the same as in A. From this figure we

choose

. Symbols are the same as in A. From this figure we

choose  as the one that provides the best fit to the tail of

as the one that provides the best fit to the tail of  . The error in the

. The error in the  case is larger than 0.02 in most cases and falls

outside the region displayed in the figure. C:

case is larger than 0.02 in most cases and falls

outside the region displayed in the figure. C:  for the four values of

for the four values of  that we tested. We see that

that we tested. We see that  .

.

Discussion

Intracellular Ca signals are built from localized release events in which Ca

signals are built from localized release events in which Ca enters the cytosol through one or several channels. Ca

enters the cytosol through one or several channels. Ca release from the endoplasmic reticulum through IP

release from the endoplasmic reticulum through IP R's is a key component of the Ca

R's is a key component of the Ca signaling toolkit in many cell types. IP

signaling toolkit in many cell types. IP R's are Ca

R's are Ca channels that need to bind IP

channels that need to bind IP and Ca

and Ca to become open and are usually organized in clusters on the

membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum. The intra-cluster organization and the

interactions of the channels within it affect the dynamics and extent of the

signals. Therefore, their study is a matter of active research.

to become open and are usually organized in clusters on the

membrane of the endoplasmic reticulum. The intra-cluster organization and the

interactions of the channels within it affect the dynamics and extent of the

signals. Therefore, their study is a matter of active research.

Recent experiments [1] that use super-resolution optical techniques are

providing detailed data on elementary IP R-mediated Ca

R-mediated Ca release events in mammalian cells. In the experiments, the number

of IP

release events in mammalian cells. In the experiments, the number

of IP R- Ca

R- Ca -channels that open during each event can be inferred from the

observed puff amplitudes without much processing. The observations of [1] showed

that the variability among clusters affected the shape of the event size

distribution,

-channels that open during each event can be inferred from the

observed puff amplitudes without much processing. The observations of [1] showed

that the variability among clusters affected the shape of the event size

distribution,  . In order to get rid of this variability, the distribution coming

from sites with similar properties was computed in [1]. The distribution,

. In order to get rid of this variability, the distribution coming

from sites with similar properties was computed in [1]. The distribution,  , obtained in this way was not Poisson, as we might have expected

if the number of channels that opened during each event was proportional to the

number of IP

, obtained in this way was not Poisson, as we might have expected

if the number of channels that opened during each event was proportional to the

number of IP R's with IP

R's with IP bound in the cluster [8]. The authors of [1] could

reproduce

bound in the cluster [8]. The authors of [1] could

reproduce  approximately (for events larger than a certain size) assuming a

weak cooperativity among channels. Namely, they assumed that the probability that a

channel became open scaled as some power of the number of open channels and obtained

that the exponent was 1/3 from a fit to the data. The rationale for the

cooperativity assumption relied on the fact that the IP

approximately (for events larger than a certain size) assuming a

weak cooperativity among channels. Namely, they assumed that the probability that a

channel became open scaled as some power of the number of open channels and obtained

that the exponent was 1/3 from a fit to the data. The rationale for the

cooperativity assumption relied on the fact that the IP R's of a cluster may be coupled via CICR induced by the Ca

R's of a cluster may be coupled via CICR induced by the Ca ions that travel from an open IP

ions that travel from an open IP R to a neighboring one. The model of [1], however, did not take

space into account and did not provide a mechanistic explanation for the obtained

scaling.

R to a neighboring one. The model of [1], however, did not take

space into account and did not provide a mechanistic explanation for the obtained

scaling.

In this paper we have presented a simple model that includes a description of the

intra-cluster spatial organization with which we can reproduce the observed

distribution over all event sizes. In the model the distribution,  , is the result of the competition of two stochastic processes: IP

, is the result of the competition of two stochastic processes: IP binding and distance-dependent CICR. The model assumes a

stationarity condition, namely, that the agonists concentration at the release site

is the same immediately before the occurrence of each puff. This condition holds as

long as puffs are independent of one another. This is consistent with the

observations reported in [1] where cluster coupling was prevented using the

slow Ca

binding and distance-dependent CICR. The model assumes a

stationarity condition, namely, that the agonists concentration at the release site

is the same immediately before the occurrence of each puff. This condition holds as

long as puffs are independent of one another. This is consistent with the

observations reported in [1] where cluster coupling was prevented using the

slow Ca buffer EGTA and where IP

buffer EGTA and where IP R- Ca

R- Ca -inhibition does not play a significant role. In any case, our

model is adequate to describe the distribution of first event sizes that occur at

each cluster before Ca

-inhibition does not play a significant role. In any case, our

model is adequate to describe the distribution of first event sizes that occur at

each cluster before Ca can exert any inhibiting effect.

can exert any inhibiting effect.

There are two limiting cases in which one of the two stochastic processes considered

in the model is the main determinant of the distribution shape. If the mean distance

between IP R's with IP

R's with IP bound in the cluster is much smaller than the typical distance of

inter-channel coupling due to CICR for most events, the distribution is IP

bound in the cluster is much smaller than the typical distance of

inter-channel coupling due to CICR for most events, the distribution is IP -binding limited and it can be approximated by a binomial or

Poisson distribution. In the opposite case, CICR dominates and the distribution is

peaked around

-binding limited and it can be approximated by a binomial or

Poisson distribution. In the opposite case, CICR dominates and the distribution is

peaked around  . The Ca

. The Ca -limited and the IP

-limited and the IP -binding limited situations can be thought of as two phases and the

transition between them as a percolation-like transition in the limit in which the

number of IP

-binding limited situations can be thought of as two phases and the

transition between them as a percolation-like transition in the limit in which the

number of IP R's with IP

R's with IP bound,

bound,  , is very large. This interpretation of the factors that shape the

observed distribution can be tested with simulations of some of the stochastic

models of intracellular Ca

, is very large. This interpretation of the factors that shape the

observed distribution can be tested with simulations of some of the stochastic

models of intracellular Ca signals reported in the literature (see e.g.

[33] and

references therein). They can also be tested experimentally. One possibility is to

change the most likely values of

signals reported in the literature (see e.g.

[33] and

references therein). They can also be tested experimentally. One possibility is to

change the most likely values of  by changing the amount of IP

by changing the amount of IP that is photo-released in the cell. An alternative option is to

analyze

that is photo-released in the cell. An alternative option is to

analyze  for events coming from clusters that give rise, on average, to

larger events. According to the model, the distribution should approach a binomial

or Poisson distribution as the mean value of

for events coming from clusters that give rise, on average, to

larger events. According to the model, the distribution should approach a binomial

or Poisson distribution as the mean value of  becomes larger while other parameters remain the same. Another way

to affect the balance between both stochastic components is to disrupt Ca

becomes larger while other parameters remain the same. Another way

to affect the balance between both stochastic components is to disrupt Ca -mediated inter-channel coupling by means of a fast buffer such as

BAPTA.

-mediated inter-channel coupling by means of a fast buffer such as

BAPTA.

Given that  is a stochastic variable that varies from event to event, the

transition between the Ca

is a stochastic variable that varies from event to event, the

transition between the Ca -dominated and IP

-dominated and IP -binding dominated stochasticity described by the model may be

reflected in the way that

-binding dominated stochasticity described by the model may be

reflected in the way that  depends on the event size,

depends on the event size,  . In fact, we have used this property to show how a fingerprint of

this transition may be encountered in

. In fact, we have used this property to show how a fingerprint of

this transition may be encountered in  and how information on the inter-channel coupling distance may be

extracted from it. This means that a parameter that characterizes the communication

between pairs of channels can be estimated from statistical information on the

emergent collective behavior of the channels of the cluster. This information could

be used to analyze the effect of buffers on the intra-cluster dynamics, a matter

that is of active current research [19], [34]. Our model provides a simple tool with which this

effect can be analyzed in experiments.

and how information on the inter-channel coupling distance may be

extracted from it. This means that a parameter that characterizes the communication

between pairs of channels can be estimated from statistical information on the

emergent collective behavior of the channels of the cluster. This information could

be used to analyze the effect of buffers on the intra-cluster dynamics, a matter

that is of active current research [19], [34]. Our model provides a simple tool with which this

effect can be analyzed in experiments.

Methods

Each term of the sum that defines Eq. (1) is the product of two functions. We have an

analytic expression for one of them,  , but not for

, but not for  . Thus, we compute

. Thus, we compute  numerically performing realizations of the model with fixed values

of

numerically performing realizations of the model with fixed values

of  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  . The location of the channels within the cluster and which of them

have IP

. The location of the channels within the cluster and which of them

have IP bound vary among realizations and are chosen randomly (see Results). We only keep realizations with

bound vary among realizations and are chosen randomly (see Results). We only keep realizations with  . Once we have the spatial distribution of available IP

. Once we have the spatial distribution of available IP R's, we start each event by picking at random one of the IP

R's, we start each event by picking at random one of the IP R's with IP

R's with IP bound and assume it is open. If

bound and assume it is open. If  , we assume it gives rise to an event with

, we assume it gives rise to an event with  . By changing the values of

. By changing the values of  ,

,  ,

,  and

and  we analyze how

we analyze how  varies with them. In this way we can determine the values of the

parameters that best reproduce the experimental observations.

varies with them. In this way we can determine the values of the

parameters that best reproduce the experimental observations.  could be measured in units of the cluster spatial extent,

could be measured in units of the cluster spatial extent,  , in which case we would get rid of one parameter of the problem,

, in which case we would get rid of one parameter of the problem,  . We keep it to make a connection with the experimental data.

However, it is important to note that the number of independent parameters of the

model is 3, for finite

. We keep it to make a connection with the experimental data.

However, it is important to note that the number of independent parameters of the

model is 3, for finite  and 2 in the limit in which

and 2 in the limit in which  can be approximated by a Poisson distribution.

can be approximated by a Poisson distribution.

For each value,  , of available IP

, of available IP R's, we estimate the fraction of events such that the

R's, we estimate the fraction of events such that the  IP

IP R's become open. This fraction is one for

R's become open. This fraction is one for  . For

. For  , we compute the probability that all available IP

, we compute the probability that all available IP R's become open,

R's become open,  , numerically, performing 500 stochastic realizations of our model

for each of which we fix the value of

, numerically, performing 500 stochastic realizations of our model

for each of which we fix the value of  a priori. Namely, we fix at the beginning the values of

a priori. Namely, we fix at the beginning the values of  ,

,  and

and  and then pick

and then pick  locations at random over the circle where we assume there are

available IP

locations at random over the circle where we assume there are

available IP R's. From there on, the model goes on as before,

generating the cascade of openings that determines

R's. From there on, the model goes on as before,

generating the cascade of openings that determines  . The distribution of events with

. The distribution of events with  open channels for each value of

open channels for each value of  gives

gives  . This function of

. This function of  depends on only one independent parameter,

depends on only one independent parameter,  . As expected, it is an increasing function of

. As expected, it is an increasing function of  (see Fig. 3

A).

(see Fig. 3

A).

We define two quantities,  and

and  , which are values of

, which are values of  for which

for which  is either close to 1 or to 0, respectively. We compute them as

follows. We first calculate a lower bound for

is either close to 1 or to 0, respectively. We compute them as

follows. We first calculate a lower bound for  as the minimum value of