Abstract

The Similarity Ensemble Approach (SEAa) relates proteins based on the set-wise chemical similarity among their ligands. It can be used to rapidly search large compound databases and to build cross-target similarity maps. The emerging maps relate targets in ways that reveal relationships one might not recognize based on sequence or structural similarities alone. SEA has previously revealed cross talk between drugs acting primarily on G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs). Here we used SEA to look for potential off-target inhibition of the enzyme protein farnesyltransferase (PFTase) by commercially available drugs. The inhibition of PFTase has profound consequences for oncogenesis, as well as a number of other diseases. In the present study, two commercial drugs, Loratadine and Miconazole, were identified as potential ligands for PFTase and subsequently confirmed as such experimentally. These results point towards the applicability of SEA for the prediction of not only GPCR-GPCR drug cross talk, but also GPCR-enzyme and enzyme-enzyme drug cross talk.

INTRODUCTION

Bringing a novel chemical entity to market cost 868 million USD in 20061, with most costs accumulating during clinical testing when drug candidates fail due to unforeseen pathway interactions. While these interactions are often harmful, causing adverse effects, they may also be beneficial, leading to useful properties. Accurate prediction of off-target drug activity prior to clinical testing may benefit patient safety and also lead to new therapeutic indications, as has been promoted by Wermuth, among others.2–5

The Similarity Ensemble Approach (SEA) uses chemical similarity among ligands organized by their targets to calculate similarities among those targets and to predict drug off-target activity.6–8 From the perspective of molecular pharmacology and bioinformatics, the approach is counter-intuitive, as it relies on ligand chemical information exclusively, using no target structure or sequence information whatsoever. Instead, SEA and related cheminformatics approaches9–15 return to an older, classical pharmacology view, where biological targets were characterized by the ligands that bind to them. To that older view, SEA adds modern methods for measuring chemical similarity for sets of ligands, and applies the BLAST16 sequence-similarity algorithms to control for the similarity among ligands and ligand sets that one would expect at random (an innovation of this method).7, 17 The technique has been used to discover several drugs activities as unanticipated targets. The opioid receptor antagonists methadone and loperamide were predicted and subsequently found to be ligands of the muscarinic and neurokinin NK2 receptors, respectively.7 More recently, the antihistamines dimetholazine and mebhydrolin base were predicted and found to have activities against α1 adrenergic, 5-HT1A and D4 receptors, and 5-HT5A, respectively; the anticholinergic diphemanil methylsulfate was predicted and found to have δ-opioid activity; the transport inhibitor fluoxetine was predicted and found to bind to the β1-adrenergic receptor; and the α1 blocker indoramin was predicted and found to have dopamine D4 activity, among others.6–8

Many of these predictions have been among drugs that bind aminergic G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs)6–8, and whereas there have been cases of predictions crossing receptor classification boundaries (e.g., ion channel blockers acting on GPCRs and transporters8), a criticism to which the approach may be liable is that it has been focused on targets for which polypharmacology is not without precedent. We thought it interesting to investigate whether off-target activity may be predicted for drugs that target enzymes, especially for those drugs predicted to be active against an enzyme that has little or no similarity to the canonical target for that drug. As a target enzyme we focused on protein farnesyltransferase (PFTase), using SEA to compare 746 commercial drugs against ligand sets built from the 1,640 known non-peptide PFTase ligands reported in ligand-receptor annotation databases (see Methods).

The post-translational attachment of lipid moieties to proteins is critical for membrane anchorage of signal transduction proteins.18 PFTase catalyzes the attachment of the C15 isoprenoid to a cysteine residue of proteins containing a C-terminal CAAX consensus sequence, where C is the cysteine to be prenylated, A is an aliphatic amino acid, and X is commonly Ser or Met.19 Upon attachment of the isoprene unit, an endoprotease cleaves off the –AAX residues. Using S-adenosylmethionine as a methyl-group donor, a methyltransferase then caps the –COOH of the prenylated protein. It is the increase in hydrophobicity, as well as the lack of charge at the C-terminus, that allows for membrane localization.20 Proteins that are farnesylated include the nuclear lamins and members of the Ras superfamily of small guanosine triphosphatases.20

The finding that mutant Ras proteins must be prenylated to exert their oncogenic effects21, 22 lead to the development of a number of inhibitors of protein prenylation, specifically through the inhibition of PFTase. Compounds were either rationally designed, based on peptide- or isoprenoid-substrate characteristics, or were discovered through screening of in-house chemical libraries. To date, five compounds have been brought to clinical trials as inhibitors of PFTase.23 Results of these trials have been modest at best, with very few compounds showing anti-tumor activity.23–25 Two drug candidates, Lonafarnib (Schearing-Plough) and Tipifarnib (Janssen Pharmaceutica) are the only compounds to make it to late-stage clinical trials26 and are currently being explored as single agents or adjunct therapies for breast cancer27 and leukemia.28, 29

While farnesyltransferase inhibitors (FTIs) have yet to live up to their promise as anti-cancer agents, they are showing applicability towards the treatment of other diseases. Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria syndrome results from a mutation in the LMNA gene, which causes an unusable form of the protein Lamin A. Because the precursor to Lamin A is farnesylated, it was proposed that FTIs may be capable of ameliorating the disease phenotypes in those suffering from progeria.30 Studies published in 2006 found that treatment of progeria mice with the FTI Lonafarnib could dramatically prevent the development of disease characteristics.31, 32 These results prompted the launch of a phase II clinical trial examining the use of Lonafarnib in progeria patients;33 the study is slated to end in October 2009. FTIs are also capable of blocking farnesylation in the protozoan parasites Trypanosoma cruzi, Trypanosoma brucei, and Plasmodium falciparum.34 The cessation of farnesylation in these parasites by inhibiting PFTase appears to be particularly toxic, indicating the potential of FTIs for the treatment of Chagas disease35 (caused by T. cruzi), African sleeping sickness36 (caused by T. brucei) and malaria37, 38 (caused by P. falciparum). The clinical relevance of FTIs towards a number of diseases necessitates the development of more potent and selective inhibitors. A starting point for identifying new PFTase inhibitors is exploring those drugs already in use for other diseases.

RESULTS

Applying SEA to Protein Farnesyltransferase

To predict which compounds may have off-target activity against PFTase, we first asked what affinity affinity ranges are relevant. Many known inhibitors have 10–20 µM affinity for this enzyme. To be comprehensive, we considered three thresholds of FTI affinity, each at increasingly greater stringency. In the first instance, we considered all those 1,692 FTIs known to have 100 µM or better affinity, reasoning that this would allow for the greatest breadth of predictions. We then narrowed our focus to include only those 1,423 FTIs with 10 µM or better affinity, and finally excluded all but the 1,188 FTIs with affinity ≤ 1 µM. We considered each threshold independently, and later extracted each commercial drug’s best SEA match with the set of known PFTase ligands at any of the three thresholds. For example, Loratadine matched most strongly against the FTIs known to have ≤ 10 µM for their target, with a SEA expectation value (E-value) of 1.07×10−81 (Table 1). On the other hand, Ubenimex was most similar to the ≤ 100 µM FTIs, with an E-value of 1.53×10−16 for them (Table 1), compared to weaker E-values of 4.97×10−13 and 7.23×10−9 for its similarity against the ≤ 10 µM and ≤ 1 µM FTIs, respectively (Table 2). An E-value, much like a p-value, denotes the likelihood that a particular event. In this case, the E-value represents the degree of chemical similarity for a commercial drug against the set of ligands for protein farnesyltransferase as compared to the similarity that would have been found by random chance alone. When applied across all 746 commercial drugs, this analysis found 13 of them (comprising 1.9% of the total drugs screened) to have measurable similarity to at least one of the three FTI sets (Table 1).

Table 1.

Top SEA predictions of off-target PFTase binding for commercial drugs

| Drug | Best SEA E-value | Best FTI Match | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Loratadine | 1.07×10−81 | 10 µM |

| 2 | Rupatadine | 1.10×10−49 | 10 µM |

| 3 | Desloratadine | 1.22×10−30 | 10 µM |

| 4 | Ubenimex | 1.53×10−16 | 100 µM |

| 5 | Azatadine | 2 68×1 0−11 | 100 µM |

| 6 | Phenylalanine S | 1.70×10−4 | 100 µM |

| 7 | Miconazole | 2.00×10−4 | 100 µM |

| 8 | Diazepam70 | 5.52×10−4 | 1 µM |

| 9 | Temazepam70 | 1.21×10−3 | 1 µM |

| 10 | Thymopentin | 2.10×10−3 | 100 µM |

| 11 | Cortisone acetate63 | 6.57×10−3 | 100 µM |

| 12 | Prednisone63 | 3.81×10−2 | 100 µM |

Drugs in ![]() have PFTase activity already reported in the literature. Drugs in

have PFTase activity already reported in the literature. Drugs in ![]() were either peptides or unavailable.

were either peptides or unavailable.

Table 2.

SEA predictions for potential PFTase ligands at various thresholds of similarity to known ligands and their subsequent analysis as PFTase inhibitors.

| Drug | SEA similarity to FTIs, by affinity threshold 1 µM / 10 µM /100 µM |

Closest known ligand |

IC50 (µM) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |  |

7.87×10−53 1.07×l0−81 1.53×l0−81 |

|

13.3 ± 1.8 |

| 2 |  |

5.90×l0−41 1.10×10−49 8.15×l0−49 |

|

76 ± 18 |

| 3 |  |

3.45×l0−27 1.22×l0−30 1.83×l0−30 |

|

>100 |

| 4 |  |

7.23×l0−9 4.97×l0−13 1.53×l0−16 |

|

>200 |

| 5 |  |

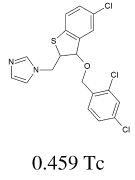

8.26×l0+2 2.86×l0−3 2.00×l0−4 |

|

18.9 ± 3.6 |

| 6 |  |

N/A |  |

23.3 ± 2.0 |

SEA E-values are shown denoting the statistical significance of each drug’s similarity to known FTIs. The more the E-value approaches zero, the more significant the similarity; the strongest prediction for each drug is in bold. Each drug was compared against three different sets of known FTIs. For instance, for the “1 µM FTIs” set, we only considered those FTIs known to have 1 µM affinity or greater for PFTase. For the “10 µM FTIs” set, we considered all FTIs known to have 10 µM or greater affinity for PFTase, etc. Where a drug’s PFTase predictions by SEA are very close (within approximately a single order of magnitude), both E-values are bolded.

Several of the predictions have relatively modest SEA values (Table 1). Formally, SEA E-values have the same meaning as the more familiar BLAST E-values, quantifying the expectation that an observed similarity would occur by chance. The underlying expectation of randomness is, of course, different for the mostly synthetic annotated ligands analyzed by SEA and naturally evolved sequences, and a pragmatic E-value cut-off for making a prediction is not yet clear. In earlier work we have often looked for E-values better (lower) than 10−10, but this is an arbitrary and conservative cutoff, and novel, potent off-target effects have been predicted based on SEA values as low as 10−4 for Vadilex’s activity against serotonin transporter and for activity of RO-25-6981 against the κ opiod receptor, 5×10−6 for dimethyltryptamine’s activity against the 5HT5A receptor, and 10−7 for Paroxetine’s activity against the β1 adrenergic receptor.8 Currently, the choice of E-value cutoff for testing predictions will vary depending on pragmatic considerations, including the intrepidness of the experimental team. In principle, and E-value below 1 is significant.

Of the thirteen commercial drugs predicted to have off-target PFTase binding by SEA, eight already had literature precedent or were difficult to source (see Methods). We tested the remaining five by in vitro analysis, and advanced two to analysis in a mammalian cell line engineered for monitoring the prenylation of H-Ras.39

In vitro analysis of PFTase inhibition

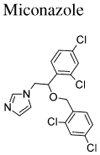

A continuous-fluorescence assay, based on the time-dependent increase in dansyl group fluorescence that occurs as the CAAX-peptide N-Dansyl-GCVLS is prenylated,40, 41 was employed to measure PFTase activity in the presence of the predicted inhibitors. This assay was used to calculate IC50 values; for confirmation, the extent of inhibition at the IC50 concentration was confirmed for each compound in a separate HPLC-based assay.42 The five commercial drugs tested comprised of three histamine H1 receptor antagonists (Loratadine, Desloratadine, and Rupatadine), an antineoplastic (Ubenimex), and an azole antifungal (Miconazole) (Table 1). In our enzymatic assay, two of the antihistamines and the azole antifungal were effective inhibitors of PFTase in the low-to-mid micromolar range (Table 2). For all but Ubenimex, the 100 µM and 10 µM FTI sets resulted in the strongest SEA predictions, with little difference in prediction strength between the two affinity classes (Table 2). This was consistent with their calculated PFTase IC50 values, which we found to be between 20–80 µM—with the exception of Desloratadine and Ubenimex, which did not inhibit PFTase up to 100 µM and 200 µM, respectively.

After conducting this work, we discovered that analogues of Loratadine have been investigated for PFTase inhibition via a high-throughput screening approach;43 Miconazole, to the best of our knowledge, is a novel PFTase inhibitor class. We thus asked whether other azole antifungals, not predicted by SEA but established members of that class, also had unreported activity with PFTase, controlling for the non-specific small-molecule aggregation in which some azoles are known to participate.44 To this end, we tested the non-aggregators Econazole, Fluconazole, and Ketoconazole, and the aggregator Clotrimazole in our continuous fluorescence assay.45 In accordance with previous work on preventing non-specific enzyme inhibition by small molecule aggregation45, Triton X-100 was included in all assay solutions to prevent aggregate formation. A non-azole, small molecule aggregator, Tetraiodophenolphthalein (TIPT), previously shown to non-specifically inhibit enzymes via this mechanism,44 was also tested for PFTase inhibition as an internal control. Only Econazole showed appreciable inhibition of PFTase with an IC50 value similar to that measured for Miconazole. The other azole antifungals, including the known aggregator Clotrimazole, showed little to no inhibition at concentrations as high as 100 µM. TPIT was not an inhibitor of PFTase, confirming that the assay conditions did not allow for in vitro small-molecule aggregation.

Analysis of Loratadine and Miconazole using a cell based in vitro assay

For a FTI to have clinical relevance, it must block the targets of protein farnesylation from functioning properly. A mammalian cell line engineered to express a chimera of the green fluorescent protein (GFP) and H-Ras46 was employed to assess the ability of Loratadine and Miconazole to block the membrane localization of Ras through inhibition of farnesylation. GFP-H-Ras that has been processed by PFTase and the subsequent enzymes in the protein prenylation pathway will be localized at the cell’s Golgi and plasma membrane. If prenylation has been inhibited, GFP-H-Ras will be present in the cellular cytosol.

Cells were treated for 24 h with varying concentrations of Loratadine and Miconazole in DMSO ranging from 1x to 5x the experimentally observed enzymatic IC50 value or DMSO vehicle alone. At 25 µM Loratadine (2.5x the IC50) appreciable inhibition of GFP-H-Ras processing was observed as evidenced by the diffuse cytosolic fluorescence not present when treated with DMSO alone (Figure 1). Localization of fluorescence at the Golgi and plasma membrane is also evident, meaning either total inhibition of the GFP-H-Ras was not achieved, or GFP-H-Ras synthesized and processed prior to treatment had not been degraded yet. Treating cells with higher concentrations of Loratadine was toxic and lead to death, while lower concentrations did not manifest observable inhibition of prenylation. Treatment of cells with Miconazole at concentrations at or above the IC50 value also lead to toxicity and cell death. Therefore, treating with 10 µM Miconazole (0.5x the IC50) for 48 h was tested. A number of cells died in this case and were subsequently washed from the plate during nuclear staining procedure (see Methods) but those cells remaining alive and still adhered to the plate had significant inhibition of GFP-H-Ras processing (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Intra-cellular inhibition of H-Ras processing by Loratadine (1). Scale bar represents 10 µm. GFP-H-Ras is shown in green. The cell nucleus is shown in blue. A: Cells grown in FBS supplemented DMEM containing 0.5% DMSO for 24 h. B: Cells grown in FBS supplemented DMEM containing 0.5% DMSO and 25 µM Loratadine for 24 h.

Figure 2.

Intra-cellular inhibition of H-Ras processing by Miconazole (5). Scale bar represents 10 µm. GFP-H-Ras is shown in green. The cell nucleus is shown in blue. A: Cells grown in FBS supplemented DMEM containing 0.5% DMSO for 48 h. B: Cells grown in FBS supplemented DMEM containing 0.5% DMSO and 10 µM Miconazole for 48 h.

DISCUSSION

Whereas the previous drug polypharmacology predicted by SEA focused on drugs that target aminergic GPCRs6–8 Loratadine and Miconazole were predicted to bind PFTase in violation of these traditional target-class boundaries. The antihistamine Loratadine represents one of the first uses of this approach to demonstrate that a commercial drug thought to be specific for a GPCR also binds an enzyme, while the activity of the anti-fungal P450 Miconazole represents the approach’s first enzyme-enzyme cross-talk prediction among commercial drugs. While the IC50 values obtained for these compounds against PFTase are modest at best, they do offer starting points for inhibitor design optimization.

Loratadine is a second-generation antihistamine that binds the H1 receptor—a cross-membrane target that shares no evolutionary history, functional role, or structural similarity with the enzyme PFTase. We found Loratadine to have an exceptionally strong E-value of 1.07×10−81 for PFTase ligands in the 10 µM − 100 µM range (Table 2), and SEA also predicted strong scores for two of its analogs, Rupatadine and Desloratadine (1.10×10−49 and 1.22×10−30, respectively, Table 2). These off-target predictions were confirmed for Loratadine and Rupatadine, at 13 µM and 76 µM IC50s, whereas Desloratadine, the primary metabolite of both Loratadine and Rupatadine, showed no appreciable inhibition up to 100 µM. For Loratadine, the ability to block the processing of H-Ras in vivo was also confirmed in our GFP-H-Ras chimera mammalian cell line. Loratadine has been reported to be active only at the histamine H1 receptor47, while Rupatadine is active at both the histamine H1 and platelet-activating factor receptors.48 Both, as well as Desloratadine, have shown good safety profiles over prolonged treatment.47, 49, 50 Antimuscarinic receptor activity, often associated with the earlier generation of H1 receptor antagonists, is not commonly observed with these drugs.51, 52

Whether or not the off-target inhibition of PFTase by Loratadine has any clinical relevance has yet to be determined. At therapeutic doses, the active metabolite of Loratadine (Desloratadine) reaches plasma concentrations of approximately 300 nM (based on information available in DRUGDEX®).53 In our study, Desloratadine was not an inhibitor of PFTase. While it appears that Loratadine will not have any clinical significance in terms of PFTase inhibition, synergistic effects with other drugs known to affect protein prenylation levels, such as the commonly prescribed statin drugs that inhibit HMG-CoA reductase54, 55 may reveal themselves. An extensive literature search revealed no evidence towards clinical off-label use of Loratadine for the indications related to PFTase. Recently, a high-throughput screening of commercial drugs for toxicity towards the parasite T. cruzi revealed Loratadine to have an IC50 value 23 µM.56 Inhibition of T. cruzi PFTase could be the cause of this observed toxicity and warrants further investigation. The presence of such off-target drug activity across GPCR and enzyme class boundaries even among well-studied commercial drugs suggests opportunities for both drug development and potential side-effect management. Whether or not the compounds developed as FTIs have any activity against the histamine H1 receptor have yet to be investigated or reported.

Miconazole and Econazole are topical imidazole antifungals that increase cell membrane permeability in fungi, resulting in leakage of cellular contents. Both of these anti-fungals inhibit 14-α demethylase, a cytochrome P-450 enzyme necessary to convert lanosterol to ergosterol, which is an essential component of cell membranes.53 Using SEA, we found that Miconazole had weak yet significant similarity to the set of 100 µM PFTase inhibitors, with an E-value of 2.00×10−4 (Table 1). Upon validating Miconazole’s 19 µM IC50 for PFTase, we also tested Econazole, which has a highly similar chemical structure, and found it to have an IC50 of 23 µM against this target (Table 2). Analyses of Miconazole’s ability to block prenylation in vivo revealed it to be toxic at concentrations high enough to result in observable inhibition. The inhibition of ergosterol biosynthesis contributes to Miconazole’s anti-fungal mechanism of action and also, it is thought, to Miconazole’s activity against the parasite T. cruzi.57 It is intriguing to consider that interactions with PFTase may complement the drugs’ anti-fungal and anti-parasitic activity. Nonetheless, the enzymes PFTase and 14-α demethylase share no evolutionary history or structural similarity, and this cross talk may suggest new directions for antifungal development.

There is no evidence in the literature pertaining towards the use of Miconazole for indications related to PFTase. Based on the information available in the DRUGDEX® system53, the peak concentration of Miconazole reached in the body upon subcutaneous delivery (the common dosage form) is approximately 25 nM. This is well below our experimental IC50 value suggesting that topical administration of Miconazole does not have any clinical significance in terms of PFTase inhibition. It is interesting to note that Miconazole has been tested by the NCI/NIH Developmental Therapeutics Program as an anti-cancer agent. According to the NCI/DTP Open Chemical Repository (NSC 170986), intra-peritoneal delivery of Miconazole was shown to promote survival in mouse models of leukemia and melanoma.58 While FTIs are not currently be explored in the treatment of melanoma, they are candidate leukemia chemotherapeutics.28, 29 Compounds developed as inhibitors of PFTase have not been reported to bind 14-α demethylase.

CONCLUSIONS

From a target-based perspective, the activities of Loratadine and Miconazole against PFTase are perplexing – neither the H1 histamine GPCR nor the fungal P450 have detectable sequence or structural similarity to protein farnesyltransferase. From an older, classical pharmacology perspective, the cross-reactivities are perhaps less surprising, as many drugs share common provenances as chemical series. What recent cheminformatics-based approaches5, 10–15 bring to this older view is a systematic analysis of all drug space – allowed by the creation of target-ligand annotation databases like WOMBAT59 and ChEMBL StARlite60 – and quantitative models that separate similarity expected at random from similarity that is quantifiably significant among ligand sets. A contribution of this work is to suggest that the similarities observed among targets, based on their ligands, may cross receptor-enzyme and enzyme-enzyme boundaries, and thus techniques that exploit a ligand-based view of pharmacology may have a wide application.60

EXPERIMENTAL

General materials and methods

All tested compounds were purchased from LKT Laboratories (St. Paul, MN) at > 98% purity as determined by HPLC. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. N-Dansyl-GCVLS was prepared as described in Gaon et. al.61 The PFTase utilized was obtained and purified as described in DeGraw et. al.62 Fluorescence measurements were made on a Beckman Coulter DTX 880 plate reader fitted with a 340 nm excitation filter and 535 nm emission filter. Hoescht nuclear dye was obtained from Invitrogen.

Sources of known protein farnesyltransferase ligands

We used several subsets of the known FTIs as our reference sets. To do so, we built the set of known ligands corresponding to each major drug target in the literature extracted from the World of Molecular BioAcTivity (WOMBAT) 2006.2 database, as in previous work.6 After removal of duplicates, molecules that we could not process, and ligands with affinities worse than 100 µM for their protein targets, this database comprised 169,046 molecules annotated into 1,469 target-function sets (e.g., the PFTase inhibitors and the PFTase binders of unknown function comprised two distinct sets). We then extracted the 1,723 molecules from this collection that were annotated as PFTase inhibitors (1,648 molecules) or PFTase binders (75 molecules), and filtered out all molecules containing two sequential peptide bonds along a standard peptide backbone, using a SMARTS filter in Scitegic PipelinePilot. We further subdivided these PFTase binders (collectively termed “FTIs” or “FTI sets” in main text) by their affinities for PFTase, into 100 µM, 10 µM, and 1 µM FTI sets, containing 1,692 molecules, 1,423 molecules, and 1,188 molecules, respectively. The remaining 1,467 target-function sets from WOMBAT were not considered in this analysis.

PFTase ligands used in the WOMBAT training sets included few marketed drugs. One exception, cortisone acetate, has an IC50 of 14 µM for PFTase.63 Secondly, the amino-bisphosphonates ibandronic acid, pamidronic acid, risedronic acid, and alendronic acid were included in the 1 µM PFTase ligand set due to their annotations in WOMBAT, although subsequent investigation revealed that direct binding of these bisphosphonates to PFTase has not been demonstrated, to our knowledge. The remaining marketed drugs shown in Table 1 were not included in the training sets, as they were not reported as PFTase ligands in WOMBAT.

Choice of ligand set thresholds

While we included a PFTase ligand set at 100 µM for completeness and to increase the chance of finding novel PFTase ligands, we note that SEA predictions for ligand sets at 10 µM compared to those at 100 µM did not substantially differ. Ubenimex was the only exception (Table 2), and in this case, the SEA prediction yielded no detectable binding at < 100 µM. Ligand set thresholds of 1 µM and 10 µM may be sufficient for future analysis directed at PFTase.

Collection of commercial drugs

We extracted all molecules annotated as marketed drugs in the WOMBAT 2006.2 database, and processed them as above (excepting peptide and 100 µM affinity filtering). This yielded 746 commercial drugs, each of which we screened individually against the FTI sets using SEA.

Similarity measures

We used 1024-bit folded Scitegic ECFP_4 topological fingerprints as previously described.6 Although we later also tested 2048-bit Daylight6, 7 fingerprints, these resulted in a narrower and weaker subset of the PFTase predictions found via ECFP_4, and are not reported here. As before, we used the Tanimoto coefficient to calculate pair-wise similarity between fingerprints.6, 7

Similarity Ensemble Approach (SEA)

SEA is based on the premise that chemically similar molecules will bind similar targets64, 65 and thus have similar biological profiles66. A raw score is calculated for ligand set similarity by summing the Tanimoto similarities67–69 between all ligand sets of interest. This score in itself is not an accurate assessment of similarity because it is dependent on the number of ligands in each set and it does not take into account random similarities. Set-size dependence is corrected for by SEA using a statistically determined threshold. Pairs of molecules that score below it are discarded and do not contribute to the overall set similarity. The raw score gets converted to a z-score, free of set-size-bias, using the mean and standard deviation of raw scores modeled from sets of random molecules. The final similarity score is expressed as an expectation value (E-value) based on the probability of observing a given z-score using random data. Small E-values reflect relationships between ligand-sets that are stronger than would be expected by random chance alone. SEA effectively links ligand sets and their corresponding protein targets together in minimal spanning trees, resulting in biological related proteins being clustered together.

Predictions of off-target PFTase binding using SEA

We ran SEA as previously described.7 The query collection consisted of the 746 commercial drugs, each drug as its own “set” of one molecule. The reference collection comprised the three overlapping sets of PFTase ligands (“FTIs”), binned into each set at (a) 1 µM, (b) 10 µM, or (c) 100 µM affinity thresholds. A FTI set with a weaker affinity threshold, such as 100 µM, comprised an all-inclusive superset of those sets at stronger affinity threshold (both the 1 µM and 10 µM sets, in this example). After each drug was compared independently against each of the three FTI sets by SEA, their E-values were compared (e.g., see Table 2), and all commercial drugs with measurable best-match E-values across sets were reported (Table 1).

Choice of drugs for testing

We excluded Diazepam and Temazepam because diazepam’s weak PFTase activity is already reported70, and the steroids because Cortisone’s and Prednisone’s PFTase activities are likewise known.63 We chose not to persue Azatadine, due to sourcing issues and did not test Thymopentin or Phenylalanine-S because they are peptides. We excluded both the known peptide FTIs and the predicted peptide drugs because SEA’s statistical models were built using small-molecule drug chemical similarity descriptors. As peptides contain oft-repeated chemical patterns in their backbones—and thus strong opportunities for uninformative similarity—they may have the potential to skew small-molecule similarity models if included. We nonetheless tested one peptide prediction, Ubenimex, because it appeared highly similar to a known FTI.

PFTase in vitro assay

The continuous fluorescence assay developed by Pompliano and coworkers41 was adapted to a 96-well plate format. Assay solutions in individual wells contained 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgCl2, 10 µM ZnCl2, 5.0 mM DTT, 0.02% (w/v) n-octylglucopyranoside, 2.0 µM N-Dansyl-GCVLS, FPP (10 µM), and inhibitor at varying concentrations (from 0 to 200 µM). All inhibitors were dissolved in DMSO due to limited solubility. For analysis of the H1 receptor agonists, a total of 5% (v/v) DMSO was in each sample. For analysis of the azole antifungals, a total of 20% (v/v) DMSO was in each sample as well as 0.04% (v/v) Triton X-100 to prevent aggregate formation. Each sample was analyzed in triplicate. PFTase was prepared by diluting purified enzyme with buffer (52mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 5.8 mM DTT, 12 mM MgCl2, 12 µM ZnCl2) containing 1 mg/mL bovine serum albumin. Samples were equilibrated at 30°C and the reaction was initiated by the addition of dilute PFTase. Fluorescence intensity was monitored via a time-based scan for 60 min or longer depending on when fluorescence enhancement ceased. The enzymatic rate of each reaction was determined by converting the rate of increase in fluorescence intensity units (FIU/s) to µM/s with eq 1,

| (1) |

where vi is the enzymatic rate in µM/s. R is the measured rate in FIU/s and P is the concentration of N-Dansyl-GCVLS used in the assay. FMAX is the fluorescence intensity of the fully prenylated peptide.

Cell based analysis of H-Ras processing

MDCK cells engineered to over-express a GFP-H-Ras chimera were used to visualize Ras processing in vivo. For all experiments, 2.6 × 104 cells/cm2 were seeded in culture dishes. The cells were grown in DMEM media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum at 37°C with 5.0% CO2 and grown to approximately 50% confluency (generally 24 h). The cells were then washed twice with serum-free DMEM and fresh serum-free DMEM was added. The desired inhibitor (Loratadine or Miconazole) in DMSO was added at varying concentrations (1 µM to 200 µM drug, 0.5 % to 1.0 % (v/v) DMSO) and incubated for 24 h at 37°C and 5.0% CO2. Hoechst 34580 nuclear stain was added to a final concentration of 1 µg/mL during the final 20 min of incubation. The cells were then washed twice with PBS and placed back in DMEM. Imaging was performed on an Olympus FluoView 1000 confocal microscope with a 60X objective. The Hoechst 34580 nuclear stain was imaged with 405 nm excitation and 461 nm emission. The GFP-H-Ras chimera was imaged with 488 nm excitation and 519 nm emission.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work is supported by the National Institutes of Health Grants GM58442 (M.D.D.) and GM71896 (B.K.S), a National Institutes of Health Training Grant T32-GM000347 (A.JD.) and a National Science Foundation fellowship (M.J.K.). We thank Sunset Molecular Discovery LLC for the use of WOMBAT. We thank Nicholette Zeliadt and Professor Elizabeth Wattenberg (University of Minnesota) for providing the MDCK cells, space to perform cell cultures, and technical assistance. The MDCK cells were a generous gift from Professor Mark Philips, New York University School of Medicine.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: SEA, Similarity Ensemble Approach; GPCRs, G-protein coupled receptors; PFTase, protein farnesyltransferase; FTIs, farnesyltransferase inhibitors; TPIT, tetraiodophenolphthalein; GFP, green fluorescent protein; WOMBAT, World of Molecular BioAcTivity.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams CP, Brantner VV. Estimating the cost of new drug development: is it really 802 million dollars? Health Aff. (Millwood) 2006;25:420–428. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.25.2.420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hopkins AL. Network pharmacology: the next paradigm in drug discovery. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:682–690. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oprea TI, Tropsha A, Faulon JL, Rintoul MD. Systems chemical biology. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2007;3:447–450. doi: 10.1038/nchembio0807-447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Scheiber J, Jenkins JL. Chemogenomic analysis of safety profiling data. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009;575:207–223. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-274-2_9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wermuth CG. Selective optimization of side activities: the SOSA approach. Drug Discov. Today. 2006;11:160–164. doi: 10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03686-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hert J, Keiser MJ, Irwin JJ, Oprea TI, Shoichet BK. Quantifying the relationships among drug classes. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2008;48:755–765. doi: 10.1021/ci8000259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keiser MJ, Roth BL, Armbruster BN, Ernsberger P, Irwin JJ, Shoichet BK. Relating protein pharmacology by ligand chemistry. Nat. Biotechnol. 2007;25:197–206. doi: 10.1038/nbt1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keiser MJ, Vincent S, Irwin JJ, Laggner C, Abbas AI, Hufeisen SJ, Jensen NH, Kuijer MB, Matos RC, Tran TB, Whaley R, Glennon RA, Hert J, Thomas KLH, Edwards DD, Shoichet BK, Roth BL. Predicting new molecular targets for known drugs. Nature. 2009 doi: 10.1038/nature08506. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bajorath J. Computational analysis of ligand relationships within target families. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2008;12:352–358. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2008.01.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campillos M, Kuhn M, Gavin AC, Jensen LJ, Bork P. Drug target identification using side-effect similarity. Science. 2008;321:263–266. doi: 10.1126/science.1158140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lounkine E, Stumpfe D, Bajorath J. Molecular Formal Concept Analysis for compound selectivity profiling in biologically annotated databases. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2009;49:1359–1368. doi: 10.1021/ci900095v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Muchmore SW, Debe DA, Metz JT, Brown SP, Martin YC, Hajduk PJ. Application of belief theory to similarity data fusion for use in analog searching and lead hopping. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2008;48:941–948. doi: 10.1021/ci7004498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Scheiber J, Jenkins JL, Sukuru SC, Bender A, Mikhailov D, Milik M, Azzaoui K, Whitebread S, Hamon J, Urban L, Glick M, Davies JW. Mapping adverse drug reactions in chemical space. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:3103–3107. doi: 10.1021/jm801546k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vieth M, Erickson J, Wang J, Webster Y, Mader M, Higgs R, Watson I. Kinase inhibitor data modeling and de novo inhibitor design with fragment approaches. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:6456–6666. doi: 10.1021/jm901147e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Young DW, Bender A, Hoyt J, McWhinnie E, Chirn GW, Tao CY, Tallarico JA, Labow M, Jenkins JL, Mitchison TJ, Feng Y. Integrating high-content screening and ligand-target prediction to identify mechanism of action. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2008;4:59–68. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2007.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Keiser MJ, Hert J. Off-target networks derived from ligand set similarity. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009;575:195–205. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-274-2_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walsh CT, Garneau-Tsodikova S, Gatto GJ., Jr Protein posttranslational modifications: The chemistry of proteome diversifications. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:7342–7372. doi: 10.1002/anie.200501023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reid TS, Terry KL, Casey PJ, Beese LS. Crystallographic Analysis of CaaX Prenyltransferases Complexed with Substrates Defines Rules of Protein Substrate Selectivity. J. Mol. Biol. 2004;343:417–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2004.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang FL, Casey PJ. Protein prenylation: molecular mechanisms and functional consequences. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1996;65:241–269. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.65.070196.001325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lowy DR, Willumsen BM. Function and regulation of ras. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1993;62:851–891. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.62.070193.004223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kato K, Cox AD, Hisaka MM, Graham SM, Buss JE, Der CJ. Isoprenoid addition to Ras protein is the critical modification for its membrane association and transforming activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1992;89:6403–6407. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.14.6403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bell IM. Inhibitors of Farnesyltransferase: A Rational Approach to Cancer Chemotherapy? J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:1869–1878. doi: 10.1021/jm0305467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhu K, Hamilton AD, Sebti SM. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors as anticancer agents: current status. Curr. Opin. Investig. Drugs. 2003;4:1428–1435. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brunner TB, Hahn SM, Gupta AK, Muschel RJ, McKenna WG, Bernhard EJ. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors: an overview of the results of preclinical and clinical investigations. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5656–5668. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doll RJ, Kirschmeier P, Bishop WR. Farnesyltransferase inhibitors as anticancer agents: critical crossroads. Curr. Opin. Drug. Discov. Devel. 2004;7:478–486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sparano JA, Moulder S, Kazi A, Coppola D, Negassa A, Vahdat L, Li T, Pellegrino C, Fineberg S, Munster P, Malafa M, Lee D, Hoschander S, Hopkins U, Hershman D, Wright JJ, Kleer C, Merajver S, Sebti SM. Phase II trial of tipifarnib plus neoadjuvant doxorubicin-cyclophosphamide in patients with clinical stage IIB-IIIC breast cancer. Clin. Cancer. Res. 2009;15:2942–2948. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karp JE, Flatten K, Feldman EJ, Greer JM, Loegering DA, Ricklis RM, Morris LE, Ritchie E, Smith BD, Ironside V, Talbott T, Roboz G, Le SB, Meng XW, Schneider PA, Dai NT, Adjei AA, Gore SD, Levis MJ, Wright JJ, Garrett-Mayer E, Kaufmann SH. Active oral regimen for elderly adults with newly diagnosed acute myelogenous leukemia: a preclinical and phase 1 trial of the farnesyltransferase inhibitor tipifarnib (R115777, Zarnestra) combined with etoposide. Blood. 2009;113:4841–4852. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-08-172726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feldman AL, Law M, Remstein ED, Macon WR, Erickson LA, Grogg KL, Kurtin PJ, Dogan A. Recurrent translocations involving the IRF4 oncogene locus in peripheral T-cell lymphomas. Leukemia. 2009;23:574–580. doi: 10.1038/leu.2008.320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Meta M, Yang SH, Bergo MO, Fong LG, Young SG. Protein farnesyltransferase inhibitors and progeria. Trends. Mol. Med. 2006;12:480–487. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2006.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang SH, Meta M, Qiao X, Frost D, Bauch J, Coffinier C, Majumdar S, Bergo MO, Young SG, Fong LG. A farnesyltransferase inhibitor improves disease phenotypes in mice with a Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome mutation. J. Clin. Invest. 2006;116:2115–2121. doi: 10.1172/JCI28968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Fong LG, Frost D, Meta M, Qiao X, Yang SH, Coffinier C, Young SG. A protein farnesyltransferase inhibitor ameliorates disease in a mouse model of progeria. Science. 2006;311:1621–1623. doi: 10.1126/science.1124875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gordon LB, Harling-Berg CJ, Rothman FG. Highlights of the 2007 Progeria Research Foundation scientific workshop: progress in translational science. J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 2008;63:777–787. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.8.777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eastman RT, Buckner FS, Yokoyama K, Gelb MH, Van Voorhis WC. Thematic review series: lipid posttranslational modifications. Fighting parasitic disease by blocking protein farnesylation. J. Lipid. Res. 2006;47:233–240. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R500016-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kraus JM, Verlinde CL, Karimi M, Lepesheva GI, Gelb MH, Buckner FS. Rational modification of a candidate cancer drug for use against Chagas disease. J. Med. Chem. 2009;52:1639–1647. doi: 10.1021/jm801313t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohkanda J, Buckner FS, Lockman JW, Yokoyama K, Carrico D, Eastman R, de Luca-Fradley K, Davies W, Croft SL, Van Voorhis WC, Gelb MH, Sebti SM, Hamilton AD. Design and synthesis of peptidomimetic protein farnesyltransferase inhibitors as anti-Trypanosoma brucei agents. J. Med. Chem. 2004;47:432–445. doi: 10.1021/jm030236o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Carrico D, Ohkanda J, Kendrick H, Yokoyama K, Blaskovich MA, Bucher CJ, Buckner FS, Van Voorhis WC, Chakrabarti D, Croft SL, Gelb MH, Sebti SM, Hamilton AD. In vitro and in vivo antimalarial activity of peptidomimetic protein farnesyltransferase inhibitors with improved membrane permeability. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2004;12:6517–6526. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ohkanda J, Lockman JW, Yokoyama K, Gelb MH, Croft SL, Kendrick H, Harrell MI, Feagin JE, Blaskovich MA, Sebti SM, Hamilton AD. Peptidomimetic inhibitors of protein farnesyltransferase show potent antimalarial activity. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2001;11:761–764. doi: 10.1016/s0960-894x(01)00055-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Keller PJ, Fiordalisi JJ, Berzat AC, Cox AD. Visual monitoring of post-translational lipid modifications using EGFP-GTPase probes in live cells. Methods. 2005;37:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.05.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cassidy PB, Dolence JM, Poulter CD. Continuous fluorescence assay for protein prenyltransferases. Methods Enzymol. 1995;250:30–43. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)50060-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pompliano DL, Gomez RP, Anthony NJ. Intramolecular fluorescence enhancement: a continuous assay of Ras farnesyl:protein transferase. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:7945–7946. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wollack JSJ, Petzold C, Mougous J, Distefano MD. A Minimalist Substrate for Enzymatic Peptide and Protein Conjugation. ChemBiochem. 2009 doi: 10.1002/cbic.200900566. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Njoroge FG, Doll RJ, Vibulbhan B, Alvarez CS, Bishop WR, Petrin J, Kirschmeier P, Carruthers NI, Wong JK, Albanese MM, Piwinski JJ, Catino J, Girijavallabhan V, Ganguly AK. Discovery of novel nonpeptide tricyclic inhibitors of Ras farnesyl protein transferase. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 1997;5:101–113. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(96)00206-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coan KE, Shoichet BK. Stoichiometry and physical chemistry of promiscuous aggregate-based inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:9606–9612. doi: 10.1021/ja802977h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Feng BY, Simeonov A, Jadhav A, Babaoglu K, Inglese J, Shoichet BK, Austin CP. A high-throughput screen for aggregation-based inhibition in a large compound library. J. Med. Chem. 2007;50:2385–2390. doi: 10.1021/jm061317y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Choy E, Chiu VK, Silletti J, Feoktistov M, Morimoto T, Michaelson D, Ivanov IE, Philips MR. Endomembrane trafficking of ras: the CAAX motif targets proteins to the ER and Golgi. Cell. 1999;98:69–80. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80607-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Morgan MM, Khan DA, Nathan RA. Treatment for allergic rhinitis and chronic idiopathic urticaria: focus on oral antihistamines. Ann. Pharmacother. 2005;39:2056–2064. doi: 10.1345/aph.1E638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Picado C. Rupatadine: pharmacological profile and its use in the treatment of allergic disorders. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2006;7:1989–2001. doi: 10.1517/14656566.7.14.1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bachert C. A review of the efficacy of desloratadine, fexofenadine, and levocetirizine in the treatment of nasal congestion in patients with allergic rhinitis. Clin. Ther. 2009;31:921–944. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2009.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mullol J, Bousquet J, Bachert C, Canonica WG, Gimenez-Arnau A, Kowalski ML, Marti-Guadano E, Maurer M, Picado C, Scadding G, Van Cauwenberge P. Rupatadine in allergic rhinitis and chronic urticaria. Allergy. 2008;63:5–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2008.01640.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Liu H, Farley JM. Effects of first and second generation antihistamines on muscarinic induced mucus gland cell ion transport. BMC Pharmacol. 2005;5:8. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-5-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Howell G, 3rd, West L, Jenkins C, Lineberry B, Yokum D, Rockhold R. In vivo antimuscarinic actions of the third generation antihistaminergic agent, desloratadine. BMC Pharmacol. 2005;5:13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2210-5-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.DRUGDEX MICROMEDEX. Greenwood Village, Colorado: Thomson Reuters; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ogunwobi OO, Beales IL. Statins inhibit proliferation and induce apoptosis in Barrett's esophageal adenocarcinoma cells. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2008;103:825–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Farwell WR, Scranton RE, Lawler EV, Lew RA, Brophy MT, Fiore LD, Gaziano JM. The association between statins and cancer incidence in a veterans population. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100(2):134–139. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Engel JC. unpublished. 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Docampo R, Moreno SNJ, Turrens JF, Katzin AM, Gonzalez-Cappa SM, Stoppani AOM. Biochemical and ultrastructural alterations produced by miconazole and econazole in Trypanosoma cruzi. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 1981;3:169–180. doi: 10.1016/0166-6851(81)90047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.National Cancer Institute. The NCI/DTP Open Chemical Repository. 2009 http://dtp.cancer.gov. NSC agent numbers 170986 and 169434.

- 59.Olah M, Rad R, Ostopovici L, Bora A, Hadaruga N, Hadaruga D, Moldovan R, Fulias A, Mracec M, Oprea TI. WOMBAT and WOMBAT-PK: Bioactivity Databases for Lead and Drug Discovery. In: Schreiber SL, Wess TKG, editors. Chemical Biology: From Small Molecules to Systems Biology and Drug Design. Wiley-VCH; 2007. pp. 760–786. [Google Scholar]

- 60.EMBL-EBI. ChEMBL StARlite. 2009 http://www.ebi.ac.uk/chembl/

- 61.Gaon I, Turek TC, Weller VA, Edelstein RL, Singh SK, Distefano MD. Photoactive Analogs of Farnesyl Pyrophosphate Containing Benzoylbenzoate Esters: Synthesis and Application to Photoaffinity Labeling of Yeast Protein Farnesyltransferase. J. Org. Chem. 1996;61:7738–7745. doi: 10.1021/jo9602736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.DeGraw AJ, Hast MA, Xu J, Mullen D, Beese LS, Barany G, Distefano MD. Caged protein prenyltransferase substrates: tools for understanding protein prenylation. Chem. Biol. Drug. Des. 2008;72:171–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2008.00698.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lingham RB, Silverman KC, Jayasuriya H, Kim BM, Amo SE, Wilson FR, Rew DJ, Schaber MD, Bergstrom JD, Koblan KS, Graham SL, Kohl NE, Gibbs JB, Singh SB. Clavaric acid and steroidal analogues as Ras- and FPP-directed inhibitors of human farnesyl-protein transferase. J. Med. Chem. 1998;41:4492–4501. doi: 10.1021/jm980356+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Frye SV. Structure-activity relationship homology (SARAH); a conceptual framework for drug discovery in the genomic era. Chem. Biol. 1999;6:R3–R7. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)80013-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Jacoby E, Schuffenhauer A, Floersheim P. Chemogenomics knowledge-based strategies in drug discovery. Drug News Perspect. 2003;16:93–102. doi: 10.1358/dnp.2003.16.2.829326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Maggiora GM, Johnson MA. Introduction to similarity in chemistry. Concepts Appl. Mol. Sim. 1990:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Karlin S, Altschul SF. Methods for assessing the statistical significance of molecular sequence features by using general scoring schemes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1990;87:2264–2268. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pearson WR. Empirical statistical estimates for sequence similarity searches. J. Mol. Biol. 1998;276:71–84. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1997.1525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Roskoski R, Jr, Ritchie PA. Time-dependent inhibition of protein farnesyltransferase by a benzodiazepine peptide mimetic. Biochemistry. 2001;40:9329–9335. doi: 10.1021/bi010290b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]