Abstract

Immunologically, “self” carbohydrates protect the HIV-1 surface glycoprotein, gp120, from antibody recognition. However, one broadly neutralizing antibody, 2G12, neutralizes primary viral isolates by direct recognition of Manα1→2Man motifs formed by the host-derived oligomannose glycans of the viral envelope. Immunogens, capable of eliciting antibodies of similar specificity to 2G12, are therefore candidates for HIV/AIDS vaccine development. In this context, it is known that the yeast mannan polysaccharides exhibit significant antigenic mimicry with the glycans of HIV-1. Here, we report that modulation of yeast polysaccharide biosynthesis directly controls the molecular specificity of cross-reactive antibodies to self oligomannose glycans. Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannans are typically terminated by α1→3-linked mannoses that cap a Manα1→2Man motif that otherwise closely resembles the part of the oligomannose epitope recognized by 2G12. Immunization with S. cerevisiae deficient for the α1→3 mannosyltransferase gene (ΔMnn1), but not with wild-type S. cerevisiae, reproducibly elicited antibodies to the self oligomannose glycans. Carbohydrate microarray analysis of ΔMnn1 immune sera revealed fine carbohydrate specificity to Manα1→2Man units, closely matching that of 2G12. These specificities were further corroborated by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay with chemically defined glycoforms of gp120. These antibodies exhibited remarkable similarity in the carbohydrate specificity to 2G12 and displayed statistically significant, albeit extremely weak, neutralization of HIV-1 compared to control immune sera. These data confirm the Manα1→2Man motif as the primary carbohydrate neutralization determinant of HIV-1 and show that the genetic modulation of microbial polysaccharides is a route towards immunogens capable of eliciting antibody responses to the glycans of HIV-1.

Keywords: 2G12, glycan array, GnT I-deficient HEK 293S, human immunodeficiency virus, kifunensine, oligomannose, vaccine, yeast

Introduction

Neutralizing antibodies are a dominant protective component of most, if not all, prophylactic vaccines. In the context of HIV-1, it has been established that naturally occurring, neutralizing antibodies exert a significant selection pressure on established infection (Frost et al. 2005) and that passive transfer of neutralizing antibodies provides sterilizing immunity to viral challenge in animal models of infection (Mascola et al. 2000; Hessell, Poignard, et al. 2009; Hessell, Rakasz, et al. 2009). However, neutralizing antibodies elicited during infection or by vaccination are generally directed to subtype-specific epitopes (Parren et al. 1997; Parren et al. 1999; Wei et al. 2003; Burton et al. 2005; Frost et al. 2005; Deeks et al. 2006). These narrowly neutralizing antibodies are unable to neutralize closely related escape variants and hence fail to contain infection. For the same reason, most antibodies generated by vaccination fail to provide protection against heterologous primary viral challenge (Pantophlet and Burton 2006). The antigenic diversity of HIV remains a fundamental barrier to the design of a prophylactic vaccine for HIV/AIDS.

In contrast to the subtype specificity of most neutralizing antibodies, a small group of broadly neutralizing antibodies (BNAbs) have been described that are each capable of neutralizing a wide range of circulating HIV isolates (Burton et al. 2005; Walker et al. 2009). The conserved elements defined by BNAbs are therefore under active evaluation as components of novel HIV immunogens, an epitope-based vaccine design process described as “reverse vaccinology” (Burton 2002; Burton et al. 2004). One such broadly neutralizing antibody is IgG 2G12, which recognizes a cluster of Manα1→2Manα1→2Man residues formed by the oligomannose glycans on the outer domain of the envelope glycoprotein, gp120 (Sanders et al. 2002; Scanlan et al. 2002; Calarese et al. 2003). In addition to this canonical motif, further modes of binding have been proposed (Sanders et al. 2002; Calarese et al. 2005) and have informed vaccine development (Dudkin et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2004).

Epitope-based vaccine design first requires the characterization of the antigenic structure of a broadly neutralizing epitope, then the synthesis/discovery of an immunogen that presents this epitope as part of a vaccine. Central to this concept of reverse vaccinology is the relationship between the epitope recognized by a broadly neutralizing antibody and that epitope’s ability to elicit similar antibodies. However, any such relationship (formally between “antigenicity” and “immunogenicity”) is unlikely to be simple, as the native antigen for a broadly neutralizing antibody is, almost by definition, unable to normally elicit such antibodies. This troubled relationship between broadly neutralizing antibodies and their epitopes may also be reflected in their unusual structures and/or modes of binding: If immunological solutions to these epitopes were routinely generated, the epitopes would be selected against during natural infection and would not be broadly conserved. In the case of 2G12, the F(ab′)2 has evolved to adopt a highly mutated, domain-exchanged configuration so as to engage its constrained carbohydrate epitope (Calarese et al. 2003).

Given the poor immunogenicity of the native carbohydrates of gp120, we have previously argued that the search for an immunogen capable of eliciting antibodies to the 2G12 epitope should include structures which also contain the Manα1→2Man motif but in a more immunogenic format (Scanlan, Offer, et al. 2007; Scanlan, Ritchie, et al. 2007). Support for this approach comes from the consideration of immune responses to self glycans generated in response to self-mimicking microbial carbohydrates (Willison 2005; Scanlan, Offer, et al. 2007; Scanlan, Ritchie, et al. 2007). In this context, we have reported that, in addition to its known epitope on gp120, 2G12 also binds selectively to yeast mannans which display extended arrays of the (Manα1→2Man)n motif, branching from a repeating Manα1→6Man backbone (Dunlop et al. 2008). Moreover, it has previously been reported that antibodies, generated to such yeast mannans, can cross react with the mannose residues found on the HIV-1 envelope in a serotype-dependent manner (Muller et al. 1991; Tomiyama et al. 1991). Together, these results provide some support for the existence of an overlap between the motif recognized by a broadly neutralizing antibody and that motif’s ability to reliably elicit specific antibodies to HIV carbohydrates. Further support for this strategy comes from the identification of self ligands capable of binding 2G12 which elicit Manα1→2Man-specific antibodies (Scanlan, Offer, et al. 2007; Scanlan, Ritchie, et al. 2007; Luallen et al. 2008). However, the molecular basis for this link between antigenicity and immunogenicity remains largely unexplored. In this study, we begin to determine the rules governing this relationship: We find that the antibodies elicited to yeast mannans display remarkable reproducibility and selectivity in their cross-reactivity to oligomannose glycans of gp120. The deletion of the Mnn1 gene, responsible for the variable and polydisperse Manα1→3Man “cap” found on the nonreducing termini of the Manα1→2Man branches of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mannan, focused the specificity of these antibodies towards Man8-9GlcNAc2 glycans (Supplementary Figure S1). Although the resultant serum closely mimicked 2G12 in its fine carbohydrate reactivity, the neutralization of primary HIV isolates was barely detectable above background and showed considerable inter-isolate variation. This molecular basis for this differential serum reactivity between Manα1→2Man and Manα1→3Man immune serum and between HIV isolates was confirmed by biosynthetic and enzymatic manipulation of gp120 N-linked glycosylation. We show that the identity of glycoforms present on gp120 has a dramatic impact on its antigenicity for yeast immune sera. The implications of our findings for HIV vaccine design are discussed.

Results and discussion

Carbohydrate microarray analysis of immune sera

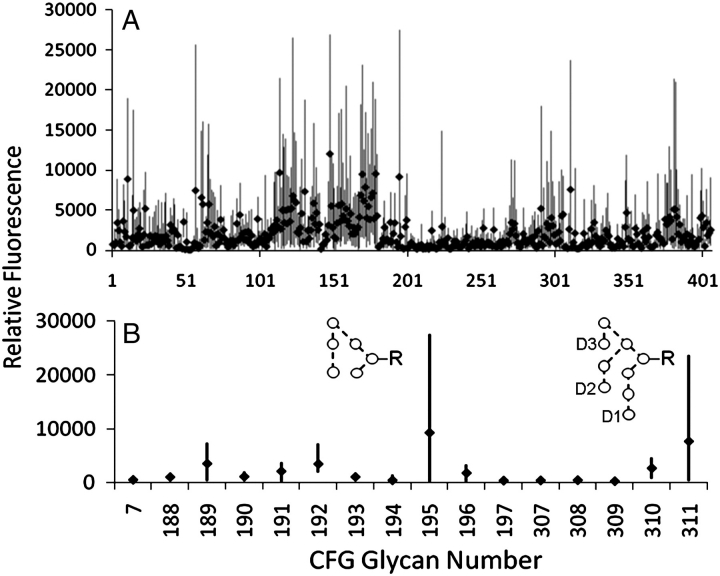

Groups of New Zealand white rabbits were immunized with whole-cell preparations of either wild-type S. cerevisiae (WT) or S. cerevisiae deficient in the α1→3 mannosyltransferase gene (ΔMnn1). Four animals for each group were given secondary immunizations with hypermannosylated gp120 (Kif-gp120BaL, as described in Materials and methods). We sought to characterize the binding of immune sera to carbohydrate antigens using the carbohydrate microarray of the Consortium of Functional Glycomics (CFG; http://www.functionalglycomics.org), which consists of 406 unique carbohydrate structures and conjugation densities. Before conducting our analysis, we first established the scale of the natural variation among pre-immune animals for the glycans present on the array (Figure 1A). Each individual serum revealed a wide range of carbohydrate reactivates, consistent with our previous studies of mammalian immune sera (Blixt et al. 2004). Moreover, our analysis revealed considerable variation in the reactivates between individuals. This has important implications for the use of glycan microarrays in the analysis of responses to carbohydrate-based immunogens and highlights the possibility of potentially misleading false positives which may have occurred independently of any immunization. We note that natural variation also extends towards the oligomannose glycans pertinent to HIV vaccine design (Figure 1B).

Fig. 1.

Natural variation in pre-immune reactivities to carbohydrate. Fluorescence intensities from the CFG glycan array are plotted from six pre-immune rabbits between the minimum and maximum signal for all glycans (A) and for oligomannose glycans (B). The average reactivity against each glycan is depicted by a black diamond. Symbols used for the structural formulae: ○, Man. The linkage position is shown by the angle of the lines linking the sugar residues (vertical line, 2-link; forward slash, 3-link; horizontal line, 4-link; back slash, 6-link). Anomericity is indicated by full lines for β-bonds and broken lines for α-bonds (Harvey et al. 2009). The nonreducing terminal D1, D2 and D3 mannoses are indicated in panel B. Unprocessed array data and structural descriptions of glycans corresponding to each CFG array number are available in Supplementary Information online.

Despite the wide heterogeneities in specificities between individual immune systems, the responses were nonetheless consistent in their general reactivity to blood group antigens, Lewis structures and, significantly, from the perspectives of this study, yeast glucan-like motifs and α-linked mannose conjugates; the complete set of array data is presented in Supplementary Information.

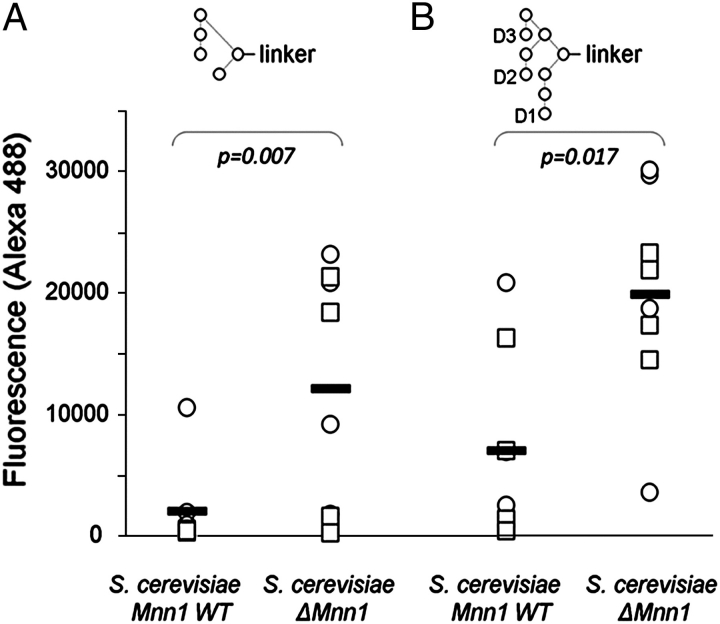

Our primary aim was to determine if there were significant differences in specificities which correlated with exposure to the particular immunogens used in this study. Although the Kif-gp120BaL boost did not alter the anticarbohydrate serum specificity, differential antibody responses were observed when the sera from animals immunized with the different yeast strains were compared. Analysis of the entire dataset of over 400 glycans revealed that the only significant (p < 0.05) difference between the WT and ΔMnn1 groups was in the serum binding to two Manα1→2Man terminating glycan probes (Figure 2). This sensitivity is exquisite: Whole cells present a wide range of possible antigens and inevitably elicit a stochastic, heterogeneous antibody response. Despite this immunological diversity and despite the antigenic space represented by the numerous and diverse glycan structures, the only difference to emerge between groups exactly recapitulated the genetic basis of the differential immunization. Specifically, Manα1→2Manα1→2Manα1→3[Manα1→2Manα1→6(Manα1→2Manα1→3)Manα1→6]Manα1→R (CFG glycan number 311) and Manα1→2Manα1→2Manα1→6(Manα1→3)Manα1→R (CFG glycan number 195) revealed elevated reactivity to ΔMnn1 immune sera over WT (Figure 2). The only shared motif between these two antigenic structures closely corresponds to the (Manα1→2Man)n epitope presented in the ΔMnn1 polysaccharide and to the Manα1→2Manα1→2Man motif recognized by 2G12. Indeed, the glycan 311 is chemically identical to the mannosyl moiety of “self” Man9GlcNAc2, abundant on the HIV envelope. Given the reactivity of ΔMnn1 sera to the structure 311, we next investigated the ability of this serum to neutralize HIV-gp120.

Fig. 2.

Comparative oligomannose glycoform specificities of rabbit sera following immunization with S. cerevisiae WT or ΔMnn1 determined by the CFG glycan array. Detection of serum reactivities to defined oligomannose glycans on glass slide format carbohydrate microarray, detected by fluorescent secondary antibody (anti-rabbit IgG, Alexa488). Sera from animals immunized with ΔMnn1 show significantly greater affinity for Manα1→2Manα1→2Manα1→6(Manα1→3)Manα1→R (CFG glycan number 195) and Manα1→2Manα1→2Manα1→3[Manα1→2Manα1→6(Manα1→2Manα1→3)Manα1→6] Manα1→R (CFG glycan number 311), shown in panels A and B, respectively. The nonreducing terminal D1, D2 and D3 mannoses are indicated in panel B.

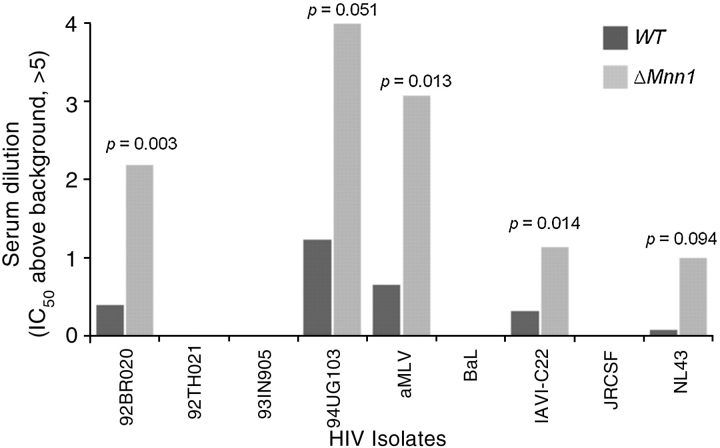

Neutralization assays

A panel of HIV-1s, including primary circulating isolates, was exposed to both sets of yeast immune sera (animals that had received the gp120 boost were excluded from this analysis). No potent neutralization was observed in either group (Figure 3). Nonetheless, there was a small but statistically significant elevation in apparent antiviral IC50 titer for the ΔMnn1 sera against three viral isolates (92BR020, IAVI C22, NL43). As the immunized animals had never been exposed to viral antigens, we hypothesized that this slight reactivity may be directed against the carbohydrates. Interestingly, a control virus used in the panel, murine leukemia virus (MLV), was also weakly neutralized by the ΔMnn1 sera compared to WT sera. Although antigenically unrelated to HIV-1, MLV does contain an envelope glycoprotein bearing oligomannose glycans (Geyer et al. 1990). These data indicate that viral isolates may differ in their susceptibility to anti-Manα1→2Man-specific antibodies present in the ΔMnn1 sera. Interestingly, this reactivity does not strongly correlate with 2G12 neutralization. For example, 94UG103 is 2G12-resistant yet is the most sensitive of the strains tested here to ΔMnn1 sera; in contrast, JRCSF is 2G12-sensitive but displays complete resistance to ΔMnn1 sera (Simek et al. 2009). Although the neutralization titers observed for the ΔMnn1 sera are far below anything that would constitute realistic protection against HIV-1, a molecular understanding of even this modest differential might guide vaccine design towards a more potent immunogen capable of eliciting higher titers against this carbohydrate target.

Fig. 3.

Cross-clade neutralization screen of immune sera against HIV isolates. The ability of WT or ΔMnn1 sera to neutralize a panel of HIV-1 isolates was tested using a high-throughput neutralization assay. The serum dilution above background required for 50% neutralization is shown for WT or ΔMnn1 sera. Although most serum neutralizations fell below the threshold for detection, there was a weak, but significant, pattern of modest neutralization for those sera immunized with ΔMnn1 but not those with WT. aMLV, murine leukemia virus (the cutoff of IC50 detection in this assay is at a 5-fold serum dilution; axis adjusted to this threshold; see Supplementary Information for full neutralization data).

Construction of an HIV glycoform array

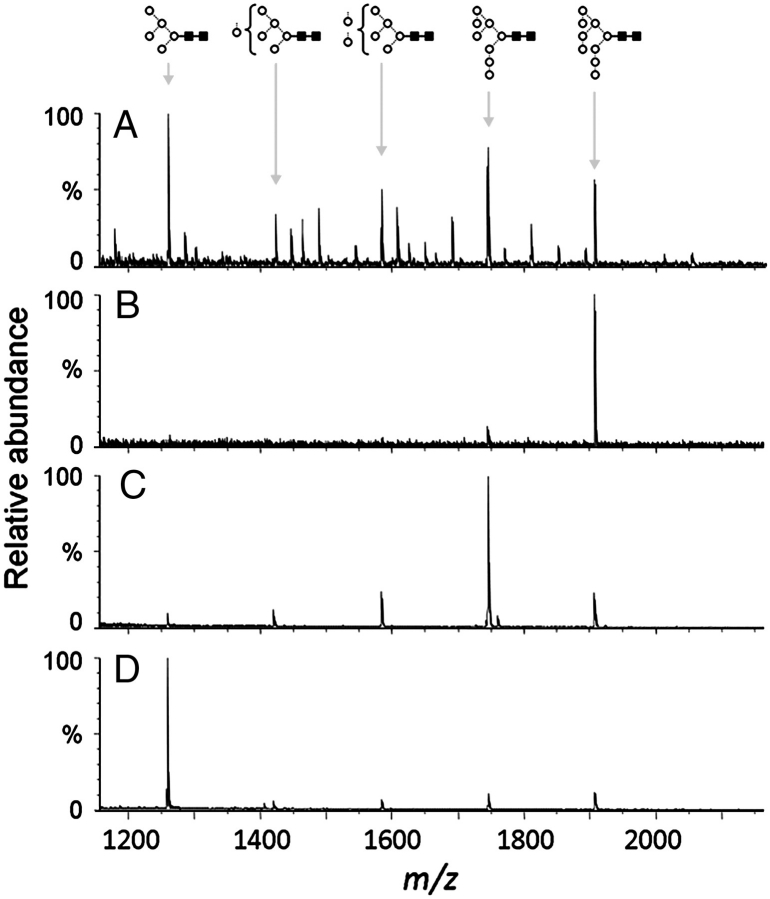

To validate our hypothesis that differential neutralization of isolates by ΔMnn1 sera was attributable to differences in viral carbohydrates, we constructed an HIV envelope glycoform array via the targeted manipulation of mammalian glycan biosynthesis. We chose as our starting point gp120BaL, which showed no sensitivity to ΔMnn1 sera in our neutralization assay and sought to manipulate its glycosylation to alter this sensitivity. We have previously shown that such inhibition of the biosynthesis of gp120 and other heavily glycosylated mammalian glycoproteins provides defined ligands for 2G12 (Scanlan, Offer, et al. 2007; Scanlan, Ritchie, et al. 2007). In that study, we used the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) α1→2 mannosidase I inhibitor, kifunensine, to trap gp120 glycans as Man9GlcNAc2. Subsequently, it has been shown that genetic manipulation of yeast glycan biosynthesis can generate similar glycoproteins with Man8GlcNAc2 glycans displaying 2G12 reactivity (Luallen et al. 2008). Here, we sought to extend our defined glycoform library to help delineate the specificity of immune sera. We characterized the glycoforms present on our glycoform array by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS) (Figure 4) and validated the isomeric assignments using negative ion fragmentation [tandem mass spectroscopy (MS/MS)] (Figure 5).

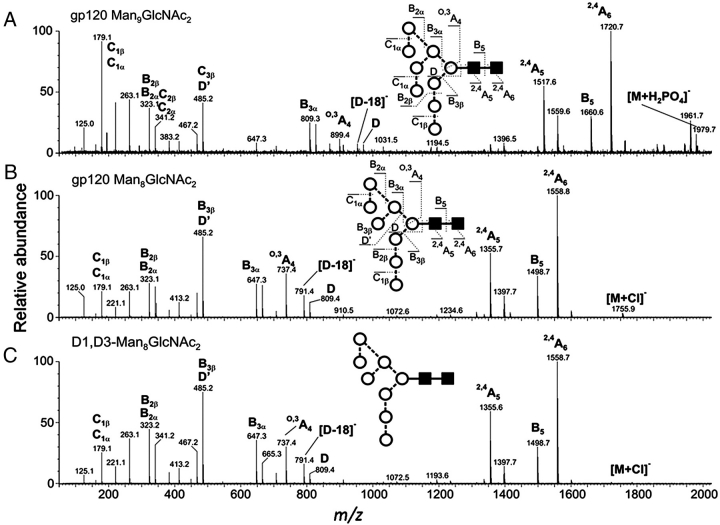

Fig. 4.

MALDI-MS analysis of gp120 glycoforms. (A) Spectra of released N-glycans from gp120 expressed in HEK 293T cells; a table of glycan masses is presented in Supplementary Information. (B) Spectra of released N-glycans from gp120 expressed in HEK 293T cells in the presence of kifunensine. (C) Spectra of released N-glycans from gp120 in HEK 293T cells in the presence of kifunensine and cleaved with ER α-mannosidase I. (D) Spectra of released N-glycans from gp120 expressed in GnT I-deficient HEK 293S cells. ○, Man; ▪, GlcNAc.

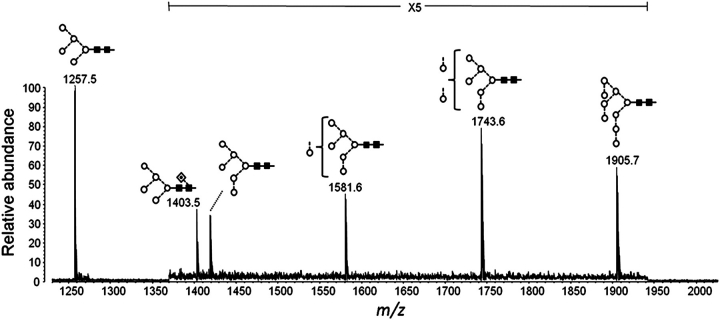

Fig. 5.

Negative ion MS/MS spectra. Fragmentation analysis of Man9GlcNAc2 from Kif-treated 293T cells (A) and the corresponding spectrum of Man8GlcNAc2 obtained by treatment with ER α1→2 mannosidase I (B). The negative ion ESI-MS/MS of a reference sample of D1,D3-Man8GlcNAc2 (C). Although the Man8GlcNAc2 spectra are of chloride adducts rather than the phosphate adduct shown for Man9GlcNAc2, the nature of the adduct does not affect the fragment ions because they are all formed by abstraction of a proton by the adduct in the first stage of the fragmentation. The nomenclature of both the glycan symbols and the fragmentation ions follows that previously described (Domon and Costello 1988; Harvey et al. 2009).

HIV gp120BaL was expressed in human embryonic kidney (HEK) 293T cells, and the N-linked glycans were characterized by MALDI-TOF-MS (Figure 4A). The spectrum of the released glycans revealed a pattern of complex glycosylation characteristic of the cell line (Bowden et al. 2008; Bowden et al. 2009; Crispin et al. 2009), dominated by galactosylated bi- and triantennary structures with variable core fucosylation (glycan masses are presented in Table S1, Supplementary Information). However, despite the expected differences between this profile and previously published analyses of gp120 glycans from Chinese hamster ovary cells (Zhu et al. 2000), the persistence of the oligomannose patch is evident. This highlights the fact that the biosynthesis of the mannose patch, and by extension the 2G12 epitope, is a protein-directed phenomenon, whereas the complex-type glycosylation is largely determined by cell type (Zhu et al. 2000; Scanlan et al. 2002; Cutalo et al. 2004; Scanlan, Offer, et al. 2007; Scanlan, Ritchie, et al. 2007).

We have previously reported that stable expression of gp120 in Chinese hamster ovary cells in the presence of kifunensine (an inhibitor of ER and Golgi apparatus type 1 α-mannosidases) yielded a glycoform with abundant Man9GlcNAc2 (Scanlan, Offer, et al. 2007; Scanlan, Ritchie, et al. 2007). MALDI-TOF-MS of glycans from gp120 transiently expressed in HEK 293T cells under similar conditions revealed an equivalent glycoform (Figure 4B). ESI-MS/MS of the peak at m/z 1979.7 (phosphate adduct, equivalent to the [M+Na]+ ion at m/z 1905.7 in the MALDI-TOF spectrum) confirmed this species as Man9GlcNAc2 (Figure 5A).

This defined gp120 glycoform was used as the starting material for the generation of a specific isomer (D1,D3-Man8GlcNAc2) of Man8GlcNAc2. We cloned and expressed human ER α1→2 mannosidase I which specifically hydrolyses the terminal mannose residue from the D2 arm of Man9GlcNAc2 to generate D1,D3-Man8GlcNAc2. Incubation of the purified ER α1→2 mannosidase I with Kif-gp120BaL yielded a glycoform dominated by a species with a mass corresponding to Man8GlcNAc2 (Figure 4C). ESI-MS/MS of the peak at m/z 1756 (chloride adduct, corresponding to the [M+Na]+ ion of Man8GlcNAc2 in the MALDI-TOF spectrum at m/z 1743) confirmed this species as the D1,D3-Man8GlcNAc2 isomer of Man8GlcNAc2 (Figure 5B and C). Spectral interpretation of the negative ion MS/MS spectrum was performed as previously described (Harvey 2005b; Harvey et al. 2008) and follows the nomenclature of Domon and Costello (1988). The chitobiose core region of both compounds is defined by the two cross-ring 2,4A6 and 2,4A5 and B5 glycosidic fragments. The ions towards the center of the spectrum define the composition of the 6-antenna; thus, the ion labeled D contains the branching mannose residue and the mannose residues of the 6-antenna, and the O,3A4 ion is a cross-ring fragment of the branching mannose containing the same antenna. The mannose residues at the nonreducing terminus give rise to the C1 fragment at m/z 179 and the B2 and C2 fragments at m/z 323 and 341, respectively. The D′ fragment contains the mannose residues of the 6-branch of the 6-antenna and appears at the same mass (m/z 485) in the spectra of both Man8GlcNAc2 and Man9GlcNAc2 showing that Man8GlcNAc2 has lost the mannose residue from the 3-branch of the 6-antenna.

Given the importance of Manα1→2Man residues in both 2G12 and ΔMnn1 serum reactivity to the CFG array, we expressed gp120 in a cell line expressing glycoproteins dominated by terminal Manα1→3Man and Manα1→6Man structures. By utilizing a HEK 293S cell line lacking GnT I activity (Reeves et al. 2002) to express gp120, complex glycan processing was trapped at the Man5GlcNAc2 biosynthetic intermediate (Figure 4D; GnT I-deficiency is also known as Lec1). An additional Man5GlcNAc2Fuc1 species is present as a result of a minor pathway that leads to the α1→6 fucosylation of the reducing terminal GlcNAc of Man5GlcNAc2 (Figure 4) (Crispin et al. 2006). Importantly, in addition to the Man5GlcNAc2-based glycans, we observed an oligomannose series corresponding to the mannose patch of normally glycosylated gp120. The maintenance of the mannose patch in the GnT I-deficient HEK 293S cells is consistent with the known biosynthetic pathway of N-linked glycans; Man5GlcNAc2 glycans are an obligate intermediate in the formation of complex- and hybrid-type glycans. The Man5GlcNAc2 glycans form 54% of the total glycan population, as assessed by the relative abundances of the five highest peaks on the MALDI-TOF-MS spectrum (Figure 6). The glycans that contribute to the Man5GlcNAc2 signal correspond to the complex, hybrid and Man5GlcNAc2 glycans of the gp120BaL spectra from HEK 293T cells, whereas the Man6-9GlcNAc2 peaks (46% relative abundance) correspond to the remaining sterically protected structures of the mannose patch. The gp120BaL expressed in the GnT I-deficient HEK 293S cell line binds to 2G12 with a broadly equivalent affinity to that expressed in the HEK 293T cells (data not shown).

Fig. 6.

Oligomannose structures of gp120 expressed in GnT I-deficient HEK 293S cells. MALDI-MS of N-linked glycans with the region of the spectra between m/z 1370 and 1945 displayed with a 5-fold magnification.

Reactivity of mannan immune sera to HIV-1 gp120

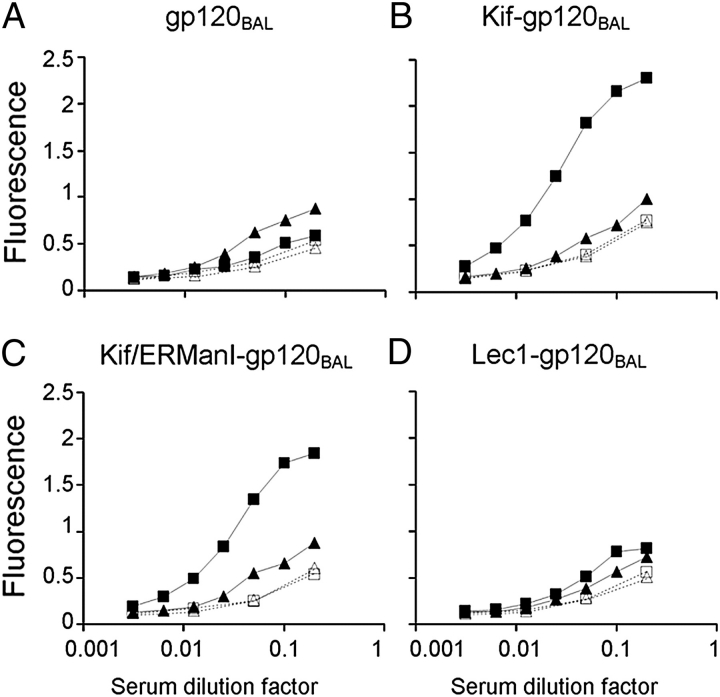

The binding of the immune sera from all animals to recombinant gp120BaL was determined by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (Figure 7). Sera from rabbits that had received gp120BaL boosts showed predictable reactivity against the cognate antigen (data not shown). However, animals vaccinated with either WT or ΔMnn1 showed no detectable serum titers against gp120BaL compared to pre-immune control sera (Figure 7A), consistent with the result from the neutralization study. However, this picture was dramatically altered when the Man9GlcNAc2 (Figure 7B) and Man8GlcNAc2 (Figure 7C) gp120BaL glycoforms were assessed. Both hypermannosylated glycoforms exhibited clear antigenicity for the ΔMnn1 but not for WT sera. This differential reactivity can be attributed to the nonreducing terminal Manα1→2Man residues as no binding was observed to gp120BaL expressed from the GnT I-deficient HEK 293S (Figure 7D), which displays predominantly Manα1→3Man and Manα1→6Man over Manα1→2Man terminating glycans (Figure 7D), again recapitulating the differential results yielded by glycan microarray analysis (Figure 2). We note that WT sera, which might be expected to have reactivity to these Manα1→3Man terminating structures, do not bind to gp120 expressed in GnT I-deficient HEK 293S cells. One possible explanation for this observation is that Manα1→3Man terminating glycan structures are somewhat abundant on the surface of self cells, for example on hybrid-type glycans, and therefore may be more tolerated than the rarer unprocessed Manα1→2Man terminating branches. We also note that the residual Manα1→2Man-containing oligomannose patch recognized by 2G12 is not productively recognized by ΔMnn1 serum in contrast to the oligomannose glycans presented by the pure Man9GlcNAc2 glycoform of gp120. This may suggest that not all antibodies generated to Man9GlcNAc2 recognize this glycan in the context of the dense oligomannose network presented on the outer domain of gp120.

Fig. 7.

Serum reactivity of animals immunized with ΔMnn1 (▪) and WT (▲) to the envelope glycoform array. ELISA plates were coated with equal amounts of glycoform-specific variants of gp120BaL expressed in: HEK 293T cells (A), HEK 293T cells grown in the presence of kifunensine (B), HEK 293T cells grown in the presence of kifunensine, with gp120 then cleaved with ER α-mannosidase I (C) or GnT I-deficient HEK 293S (Lec1) cells (D). Sera from WT and ΔMnn1 immunizations were assayed for binding in serial dilution. Corresponding serum pre-bleed reactivity is indicated for both ΔMnn1 (□) and WT (△). Each data point is the mean for n = 4 animals. Assay repeated three times.

Reactivity of 2G12 and mannan immune sera to the neoglycolipid array

The results from the CFG glycan array, the neutralization assay and the viral envelope array indicate that Manα1→2Man structures are the key mediators of serum reactivity. While 2G12 is known to bind to this motif (Scanlan et al. 2002; Calarese et al. 2003), the specificity of the serum seems narrower than some alternative modes of binding postulated for 2G12 (Sanders et al. 2002; Calarese et al. 2005). In addition to the 3-branch of the trimannosyl core which supports the D1 motif, the 6-branch of the trimannosyl core has been proposed to provide either the D3 arm (Calarese et al. 2005) or hybrid-type glycans (Sanders et al. 2002) as alternative motifs for 2G12 binding. Immunogens based on both of these alternative non-D1 arm binding modes have been synthesized for evaluation as vaccine candidates (Dudkin et al. 2004; Lee et al. 2004). In light of the central role of the D1-motif highlighted by this study, we sought to reconcile these data using a neoglycolipid (NGL) array presenting a wide range of homogeneously presented oligomannose-type glycans. We also selected representative immune sera to determine whether the enhanced Manα1→2Man reactivity shown by the ΔMnn1 over WT serum paralleled that of the only confirmed neutralizing monoclonal antibody to HIV-1 carbohydrates, 2G12 (Figure 8).

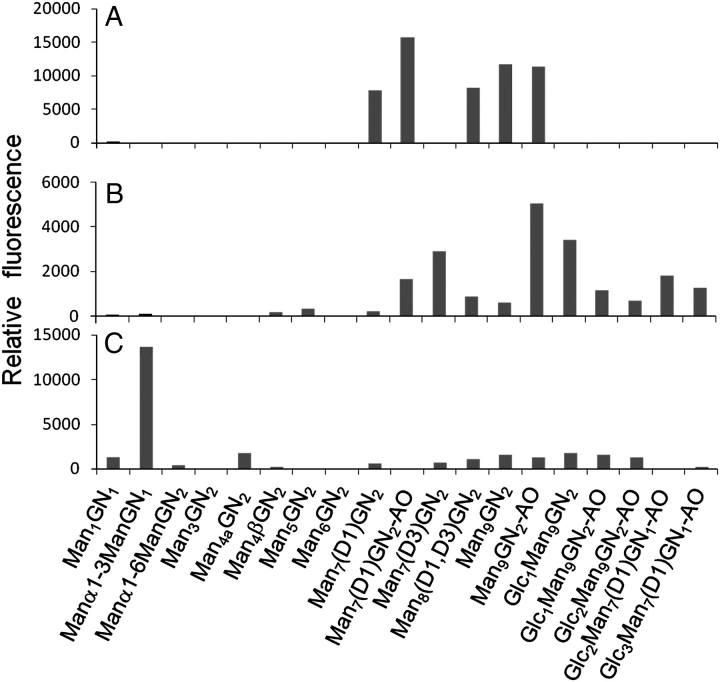

Fig. 8.

Binding to neoglycolipid array. Serum and 2G12 was probed against a neoglycolipid array. The reactivity of 2G12 to Manα1→2Man terminating glycans is evident (A) but only in those glycans with an exposed D1 arm (for example, Man9GlcNAc2 and Man7(D1)GlcNAc2 but not Glc1Man9GlcNAc2). The binding of a representative serum from each of the ΔMnn1 (B) and WT (C) groups is included for comparison and to validate the assay in comparison with serum analyzed on the CFG array. The marked reactivity of the WT but not ΔMnn1 to the Manα1→3Man terminating structure is consistent with the deletion of this motif in the ΔMnn1 immunogen. The overall pattern of relative reactivities of ΔMnn1 more closely resembles that of 2G12 than does WT serum. GlcNAc is abbreviated to GN and AO, aminoxy linker.

We have previously argued that 2G12 binds through the D1-arm of oligomannose-type glycans. This mode of binding was supported by the observation that 2G12 binding was inhibited by Aspergillus saitoi α1→2-mannosidase and by the observation that gp120 expressed in the presence of the α-glucosidase inhibitor N-butyldeoxynojirimycin, which induces the presence of glucosyl moieties capping the D1-arm of oligomannose glycans, blocks 2G12 binding but not the binding of the conformationally specific monoclonal antibody, b12 (Scanlan et al. 2002). Finally, the crystal structure of the 2G12Man9GlcNAc2 complex revealed that the protein–carbohydrate interface was dominated by the D1-arm (Calarese et al. 2003).

However, a subsequent crystal structure of 2G12 in complex with the D3,D2-terminating Man5 fragment, Man(D3)α1→2Manα1→6[Man(D2)α1→2Manα1→3]Man, revealed an alternative mode of recognition through the D3 arm (Calarese et al. 2005). However, while 2G12 binds to Man9GlcNAc2, D1-Man7GlcNAc2 and D1,D3-Man8GlcNAc2, on the neoglycolipid array (Figure 8A), no detectable binding was revealed for the related D3-terminating structure, Man(D3)α1→2Manα1→6[Manα1→3]Manα1→6[Manα1→2Manα1→3]Man1GlcNAc2 or for the glucosylated structures, Glc1Man9GlcNAc2 and Glc2Man9GlcNAc2. We sought to structurally rationalize these observations (Figure 9). Superimposition of the solution-state nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) structure of Man9GlcNAc2 (Woods et al. 1998) onto the branching reducing terminal mannose of the Man5 fragment, to generate the remaining saccharide residues, revealed extensive clashes with the protein surface of 2G12 (Figure 9A and B). Clashes are also observed when a Man9GlcNAc2 crystal structure (from the complex with 2G12) is similarly docked (not shown). This suggests that, while the isolated Man5 fragment can bind to 2G12, the D3-mode of binding may be less favorable when presented in the context of Man9GlcNAc2.

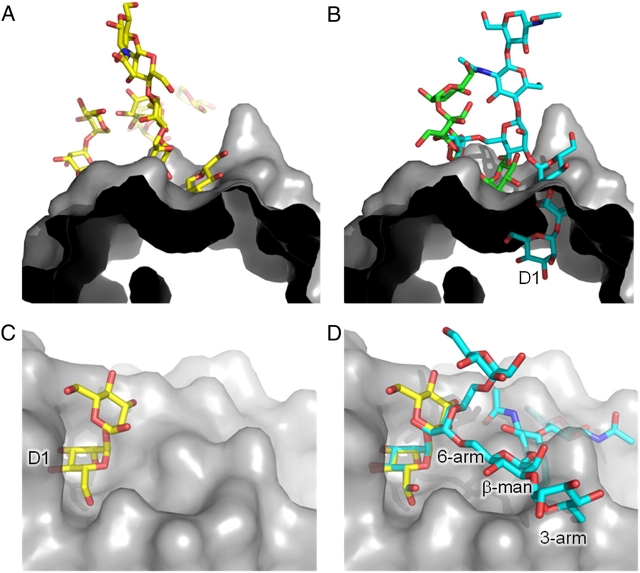

Fig. 9.

Molecular basis of 2G12-carbohydrate recognition. Glycans are represented in sticks and the protein surface in gray. (A) The crystal structure of 2G12 in complex with Man9GlcNAc2 (Calarese et al. 2003). (B) The crystal structure of 2G12 in complex with the D3-terminating glycan, Man(D3)α1→2Manα1→6[Manα1→2Manα1→3]Man (green) (Calarese et al. 2005) with the remaining saccharide residues generated by docking the solution-state NMR structure of Man9GlcNAc2 onto the reducing terminal mannose (cyan). (C) The crystal structure of 2G12 in complex with Manα1→2Man (yellow) (Calarese et al. 2003). (D) The Manα1→3Man terminal residue of a hybrid-type glycan (cyan) docked onto the crystal structure of 2G12 in complex with Manα1→2Man using the most abundant torsion angles (Petrescu et al. 1999; Wormald et al. 2002).

A further 2G12 recognition mode involving terminal mannose residues of hybrid-type glycans has also been proposed (Sanders et al. 2002). As hybrid-type glycans and the WT yeast used in the present immunization study both contain extensive terminal Manα1→3Man residues, we sought to determine if this was a plausible binding mode. No binding was detected to a range of hybrid-type glycans on the neoglycolipid array. Furthermore, modeling a hybrid-type glycan into the 2G12 binding pocket with the Manα1→3Man docked onto the nonreducing terminal of the high-resolution structure of the Manα1→3Man–2G12 complex with preferred torsion angles (Petrescu et al. 1999; Wormald et al. 2002) resulted in extensive clashes with the protein (Figure 9C and D).

This is also consistent with the inability of the disaccharides Manα1→6Man and Manα1→3Man to inhibit 2G12–gp120 interactions (Calarese et al. 2003). We conclude that these alternative non-D1 recognition modes of 2G12 do not contribute significantly to the binding to gp120. The reactivity of ΔMnn1 serum also shows a preference for Manα1→2Man over Manα1→3Man and Manα1→6Man terminating glycans (Figures 2 and 7), a pattern which is echoed by analysis of sera on the NGL array which shows that WT, but not ΔMnn1 sera, reacts with Manα1→3Man (Figure 8B and C).

Consistent with the results from the CFG array and the HIV glycoform array, the ΔMnn1 serum binds to a very similar pattern of oligomannose structures on the CFG and NGL arrays as 2G12 (Figures 2 and 8). However, the sera appear to tolerate the presence of D1 glucosylation indicating perhaps a somewhat wider degree of monosaccharide or linkage specificity compared to 2G12. We have previously argued that 2G12 may in fact represent an antimicrobial response, which through domain-exchange acquired avidity to HIV-1 (Scanlan, Offer, et al. 2007; Scanlan, Ritchie, et al. 2007; Dunlop et al. 2008). The remarkable similarity in molecular specificities between yeast immune sera and 2G12 would be entirely consistent with such hypothesis. There is, regardless, a convergence, revealed by this study, in the antigenic specificity of the serum reactivity generated in this study and the carbohydrate selectivity of the broadly neutralizing antibody, 2G12. This confirms the principle that genetic modulation of microbial polysaccharides can yield immunogenic mimics capable of eliciting antibody responses to the self glycans of HIV-1.

Materials and methods

Protein expression and purification

The full-length soluble ectodomain of HIV-1 gp120BaL (corresponding to amino acid residues 1 to 507, numbering based on alignment with the HxB2 reference strain) and the C-terminal catalytic domain of human ER class I α1→2-mannosidase (corresponding to amino acid residues 237 to 699) were cloned and expressed as previously described (Aricescu et al. 2006). cDNA was cloned into the pHLsec vector encoding an in-frame C-terminal hexahistidine tag, and the target proteins were transiently expressed in HEK 293T (ATCC CRL-1573). The HEK 293T and GnT I-deficient HEK 293S (Reeves et al. 2002) cell lines were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin and 10% fetal bovine serum. Transient transfections were performed using a mixture of polyethylenimine and 2 mg DNA per liter cell culture. When used, the α-mannosidase inhibitor kifunensine (Cayman Europe, Estonia) was added at the stage of transfection at a concentration of 4 mg/mL (Chang et al. 2007). Culture supernatants were collected and replaced with new serum-free media 2 days post transfection, and the replacement media was collected an additional 3 days later. Protease inhibitor was added to the pooled supernatants. Following concentrated by ultrafiltration (Vivaspin 20, Sartorius), gp120 was initially isolated by immobilized metal affinity chromatography then further purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 Prep Grade column (GE Health Care) with a 150-mM NaCl, 10-mM Tris (pH 8.0) buffer. Typical gp120 yields per liter of cell culture were approximately 5 mg/mL from the HEK 293S and HEK 293T cells and approximately 6 mg/mL from HEK 293T with kifunensine. Yields for the ER α-mannosidase I per liter cell culture were typically 1–2 mg/mL.

Mass spectrometry of oligosaccharides

Glycans were released enzymatically following the method of Küster et al. (1997). Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE bands containing approximately 10 μg of target glycoproteins were excised, washed with 20 mM NaHCO3 pH 7.0 and dried in a vacuum centrifuge before rehydration with 30 μL of 30 mM NaHCO3 pH 7.0, containing 100 U/mL of protein N-glycanase F (PNGase F; Prozyme, San Leandro, CA, United States). After incubation for 12 h at 37°C, the enzymatically released N-linked glycans were eluted with water. Aqueous solutions of glycans were cleaned with a Nafion 117 membrane (Börnsen et al. 1995) prior to mass spectrometry.

Positive ion MALDI-TOF mass spectra were recorded with a Shimazu AXIMA TOF2 MALDI-TOF/TOF mass spectrometer fitted with delayed extraction and a nitrogen laser (337 nm). Samples were prepared by adding 0.5 μL of an aqueous solution of the glycans to the matrix solution (0.3 μL of a saturated solution of 2,5-dihydroxybenzoic acid in acetonitrile) on the stainless steel target plate and allowing it to dry at room temperature. The sample/matrix mixture was then recrystallized from ethanol. Further samples were examined after removal of sialic acids by heating at 80°C for 1 h with 1% acetic acid.

Electrospray mass spectrometry was performed with either a Waters quadrupole-time-of-flight (Q-Tof) Ultima Global instrument or a Q-Tof model 1 spectrometer (Waters MS Technologies, Manchester, United Kingdom) in negative ion mode. Samples in 1:1 (v:v) methanol:water were infused through Proxeon nanospray capillaries (Proxeon Biosystems, Odense, Denmark). The ion source conditions were as follows: temperature, 120°C; nitrogen flow, 50 L/h; infusion needle potential, 1.1 kV; cone voltage, 100 V; RF-1 voltage 150 V (Ultima Global instrument). Spectra (2-s scans) were acquired until a satisfactory signal:noise ratio had been obtained. For MS/MS data acquisition, the parent ion was selected at low resolution (about 5 m/z mass window) to allow transmission of isotope peaks and fragmented with argon at a pressure (recorded on the instrument’s pressure gauge) of 0.5 mBar. The voltage on the collision cell was adjusted with mass and charge to give an even distribution of fragment ions across the mass scale. Typical values were 80–120 V. Other voltages were as recommended by the manufacturer. Instrument control, data acquisition and processing were performed with MassLynx (Waters) software version 4.0 (Q-Tof 1) or 4.1 (Ultima Global). Analysis of fragmentation spectra was performed as previously described (Harvey 2005a, 2005b, 2005c, 2005d; Harvey et al. 2008).

Immunization

Wild-type (WT) S. cerevisiae (MATα, BY4742 strain) and an identical strain containing a homozygous deletion of the Mnn1 gene (ΔMnn1) were obtained from Open Biosystems. The strains were grown at 30°C in YPD medium (1% [w/v] yeast extract; 2% [w/v] bactopeptone; 2% [w/v] dextrose) with 120 µg/mL kanamycin and shaken at 170 rpm. Cultures were harvested after 26 h, pelleted and then resuspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) pH 7. Preparations of each strain were heat-killed (100°C for 1 h) then aliquoted and frozen at set doses of 108 cells per animal per inoculation.

A high-frequency vaccination protocol similar to that used by Ballou was performed (Ballou 1990). Sixteen rabbits (New Zealand White) were divided into four groups. Groups 1 and 2 received thrice weekly intravenous marginal ear vein injections of WT and ΔMnn1, respectively, for 9 weeks. Groups 3 and 4 followed an identical protocol for the first 4 weeks with Group 3 receiving WT and Group 4 receiving ΔMnn1. After 4 weeks, these animals were switched to a protocol of three successive boosts of 50 μg of Kif-gp120BaL at fortnightly intervals. The Kif-gp120BaL was administered intramuscularly by an injection to each quadriceps. Injections of Kif-gp120BaL were co-administered with a lecithin and acrylic polymer emulsion adjuvant, Adjuplex, that has been reported to increase vaccine-induced serum IgG antibody titers (Gupta et al. 1995). Neutralization assays were performed as previously described (Simek et al. 2009).

Carbohydrate microarray analysis

Serum was analyzed for carbohydrate reactivity using the glycan array developed by the Consortium for Functional Glycomics (http://www.functionalglycomics.org) following their standard protocol (Blixt et al. 2004; Astronomo et al. 2008). In addition, carbohydrate reactivities were also profiled using the Neoglycolipid Array (Imperial College, United Kingdom) (Palma et al. 2006).

ER α1→2 mannosidase I digestion of Kif-gp120BaL

Kif-gp120BaL (20 μg) was incubated with purified ER α1→2 mannosidase I (1 μg) in a reaction buffer consisting of 80 mM 1,4-piperazinediethanesulfonic acid, 1 μg/μL bovine serum albumin (BSA), 4 mM CaCl2 and 0.016% NaN3 (pH 6.5). Incubation volumes were typically 100–1000 μL, and the reactions were carried out at 20–25°C overnight. Following the digestion, the modified Kif-gp120BaL was purified by size exclusion chromatography using a Superdex 200 Prep Grade column (GE Health Care) with a 150 mM NaCl, 10 mM Tris (pH 8.0) buffer. The enzyme was removed using Amicon Micropure-EZ™ spin columns.

Glycoform array analysis

Serum ELISA experiments were performed with half area microtiter plate wells (Costar type 3690, Corning) coated overnight at 4°C with 1 μg/mL glycoform-defined gp120BaL. Plates were subsequently blocked with 3% (w/v) BSA for 1 h. Serum was diluted during the blocking step using low-protein-binding 96-well Sero-Wel plates (Bibby Sterilin). After each incubation, the plates were washed five times with PBS. Binding was detected using alkaline-phosphatase conjugated secondary antibodies (1 μg/mL in PBS, with 1% BSA) from Pierce (Rockford, IL, United States).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data for this article is available online at http://glycob.oxfordjournals.org/.

Funding

This work was supported by grants from UK Research Councils’ Basic Technology initiative ‘Glycoarrays’ (GR/S79268), UK Engineering and Physical Research Councils Translational Grant EP/G037604/1, the NCI Alliance of Glycobiologists for Detection of Cancer and Cancer Risk (U01 CA128416). A.S.P. is a fellow of the Fundação para a Ciência e Tecnologia, Portugal (SFRH/BPD/26515/2006).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI) and the Oxford Glycobiology Endowment. We would like to acknowledge an equipment grant from IAVI to purchase the Shimazu AXIMA TOF2 MALDI-TOF/TOF and the Wellcome Trust and the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council for equipment grants to purchase the Q-TOF mass spectrometers. DCD was supported by a Wellcome Trust studentship.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

Abbreviations

BNAbs, broadly neutralizing antibodies; BSA, bovine serum albumin; CFG, Consortium of Functional Glycomics; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunoabsorbant assay; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ESI, electrospray ionization; HEK, human embryonic kidney; MALDI-TOF-MS, matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry; MLV, murine leukemia virus; MS/MS, tandem mass spectroscopy; NGL, neoglycolipid; NMR, nuclear magnetic resonance; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; Q-Tof, quadrupole-time-of-flight.

References

- Aricescu AR, Lu W, Jones EY. A time- and cost-efficient system for high-level protein production in mammalian cells. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2006;62:1243–1250. doi: 10.1107/S0907444906029799. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Astronomo RD, Lee HK, Scanlan CN, Pantophlet R, Huang CY, Wilson IA, Blixt O, Dwek RA, Wong CH, Burton DR. A glycoconjugate antigen based on the recognition motif of a broadly neutralizing human immunodeficiency virus antibody, 2G12, is immunogenic but elicits antibodies unable to bind to the self glycans of gp120. J Virol. 2008;82:6359–6368. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00293-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballou CE. Isolation, characterization, and properties of Saccharomyces cerevisiae mnn mutants with nonconditional protein glycosylation defects. Methods Enzymol. 1990;185:440–470. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)85038-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blixt O, Head S, Mondala T, Scanlan C, Huflejt ME, Alvarez R, Bryan MC, Fazio F, Calarese D, Stevens J, Razi N, Stevens DJ, Skehel JJ, van Die I, Burton DR, Wilson IA, Cummings R, Bovin N, Wong CH, Paulson JC. Printed covalent glycan array for ligand profiling of diverse glycan binding proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:17033–17038. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407902101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Börnsen KO, Mohr MD, Widmer HM. Ion exchange and purification of carbohydrates on a Nafion(r) membrane as a new sample pretreatment for matrix- assisted laser desorption-ionization mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 1995;9:1031–1034. [Google Scholar]

- Bowden TA, Crispin M, Graham SC, Harvey DJ, Grimes JM, Jones EY, Stuart DI. Unusual molecular architecture of the machupo virus attachment glycoprotein. J Virol. 2009;83:8259–8265. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00761-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden TA, Crispin M, Harvey DJ, Aricescu AR, Grimes JM, Jones EY, Stuart DI. Crystal structure and carbohydrate analysis of Nipah virus attachment glycoprotein: A template for antiviral and vaccine design. J Virol. 2008;82:11628–11636. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01344-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton DR. Antibodies, viruses and vaccines. Nat Rev Immunol. 2002;2:706–713. doi: 10.1038/nri891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton DR, Desrosiers RC, Doms RW, Koff WC, Kwong PD, Moore JP, Nabel GJ, Sodroski J, Wilson IA, Wyatt RT. HIV vaccine design and the neutralizing antibody problem. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:233–236. doi: 10.1038/ni0304-233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton DR, Stanfield RL, Wilson IA. Antibody vs. HIV in a clash of evolutionary titans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:14943–14948. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505126102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calarese DA, Lee HK, Huang CY, Best MD, Astronomo RD, Stanfield RL, Katinger H, Burton DR, Wong CH, Wilson IA. Dissection of the carbohydrate specificity of the broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 antibody 2G12. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:13372–13377. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0505763102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calarese DA, Scanlan CN, Zwick MB, Deechongkit S, Mimura Y, Kunert R, Zhu P, Wormald MR, Stanfield RL, Roux KH, Kelly JW, Rudd PM, Dwek RA, Katinger H, Burton DR, Wilson IA. Antibody domain exchange is an immunological solution to carbohydrate cluster recognition. Science. 2003;300:2065–2071. doi: 10.1126/science.1083182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang VT, Crispin M, Aricescu AR, Harvey DJ, Nettleship JE, Fennelly JA, Yu C, Boles KS, Evans EJ, Stuart DI, Dwek RA, Jones EY, Owens RJ, Davis SJ. Glycoprotein structural genomics: Solving the glycosylation problem. Structure. 2007;15:267–273. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispin M, Chang VT, Harvey DJ, Dwek RA, Evans EJ, Stuart DI, Jones EY, Lord JM, Spooner RA, Davis SJ. A human embryonic kidney 293T cell line mutated at the Golgi α-mannosidase II locus. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21684–21695. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.006254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crispin M, Harvey DJ, Chang VT, Yu C, Aricescu AR, Jones EY, Davis SJ, Dwek RA, Rudd PM. Inhibition of hybrid- and complex-type glycosylation reveals the presence of the GlcNAc transferase I-independent fucosylation pathway. Glycobiology. 2006;16:748–756. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwj119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutalo JM, Deterding LJ, Tomer KB. Characterization of glycopeptides from HIV-I(SF2) gp120 by liquid chromatography mass spectrometry. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2004;15:1545–1555. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeks SG, Schweighardt B, Wrin T, Galovich J, Hoh R, Sinclair E, Hunt P, McCune JM, Martin JN, Petropoulos CJ, Hecht FM. Neutralizing antibody responses against autologous and heterologous viruses in acute versus chronic human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection: Evidence for a constraint on the ability of HIV to completely evade neutralizing antibody responses. J Virol. 2006;80:6155–6164. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00093-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domon B, Costello CE. A systematic nomenclature for carbohydrate fragmentations in FAB-MS/MS spectra of glycoconjugates. Glycoconjugate J. 1988;5:397–409. [Google Scholar]

- Dudkin VY, Orlova M, Geng X, Mandal M, Olson WC, Danishefsky SJ. Toward fully synthetic carbohydrate-based HIV antigen design: On the critical role of bivalency. J Am Chem Soc. 2004;126:9560–9562. doi: 10.1021/ja047720g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop DC, Ulrich A, Appelmelk BJ, Burton DR, Dwek RA, Zitzmann N, Scanlan CN. Antigenic mimicry of the HIV envelope by AIDS-associated pathogens. AIDS. 2008;22:2214–2217. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e328314b5df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost SD, Wrin T, Smith DM, Kosakovsky Pond SL, Liu Y, Paxinos E, Chappey C, Galovich J, Beauchaine J, Petropoulos CJ, Little SJ, Richman DD. Neutralizing antibody responses drive the evolution of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope during recent HIV infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18514–18519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0504658102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geyer H, Kempf R, Schott HH, Geyer R. Glycosylation of the envelope glycoprotein from a polytropic murine retrovirus in two different host cells. Eur J Biochem. 1990;193:855–862. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1990.tb19409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RK, Rost BE, Relyveld E, Siber GR. Adjuvant properties of aluminum and calcium compounds. Pharm Biotechnol. 1995;6:229–248. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-1823-5_8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey DJ. Fragmentation of negative ions from carbohydrates: Part 1. Use of nitrate and other anionic adducts for the production of negative ion electrospray spectra from N-linked carbohydrates. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005a;16:622–630. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey DJ. Fragmentation of negative ions from carbohydrates: Part 2. Fragmentation of high-mannose N-linked glycans. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005b;16:631–646. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey DJ. Fragmentation of negative ions from carbohydrates: Part 3. Fragmentation of hybrid and complex N-linked glycans. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2005c;16:647–659. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey DJ. Structural determination of N-linked glycans by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization and electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Proteomics. 2005d;5:1774–1786. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200401248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey DJ, Merry AH, Royle L, Campbell MP, Dwek RA, Rudd PM. Proposal for a standard system for drawing structural diagrams of N- and O-linked carbohydrates and related compounds. Proteomics. 2009;9:3796–3801. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200900096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey DJ, Royle L, Radcliffe CM, Rudd PM, Dwek RA. Structural and quantitative analysis of N-linked glycans by matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization and negative ion nanospray mass spectrometry. Anal Biochem. 2008;376:44–60. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2008.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessell AJ, Poignard P, Hunter M, Hangartner L, Tehrani DM, Bleeker WK, Parren PW, Marx PA, Burton DR. Effective, low-titer antibody protection against low-dose repeated mucosal SHIV challenge in macaques. Nat Med. 2009;15:951–954. doi: 10.1038/nm.1974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hessell AJ, Rakasz EG, Poignard P, Hangartner L, Landucci G, Forthal DN, Koff WC, Watkins DI, Burton DR. Broadly neutralizing human anti-HIV antibody 2G12 is effective in protection against mucosal SHIV challenge even at low serum neutralizing titers. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000433. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Küster B, Wheeler SF, Hunter AP, Dwek RA, Harvey DJ. Sequencing of N-linked oligosaccharides directly from protein gels: In-gel deglycosylation followed by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization mass spectrometry and normal-phase high-performance liquid chromatography. Anal Biochem. 1997;250:82–101. doi: 10.1006/abio.1997.2199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HK, Scanlan CN, Huang CY, Chang AY, Calarese DA, Dwek RA, Rudd PM, Burton DR, Wilson IA, Wong CH. Reactivity-based one-pot synthesis of oligomannoses: Defining antigens recognized by 2G12, a broadly neutralizing anti-HIV-1 antibody. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2004;43:1000–1003. doi: 10.1002/anie.200353105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luallen RJ, Lin J, Fu H, Cai KK, Agrawal C, Mboudjeka I, Lee FH, Montefiori D, Smith DF, Doms RW, Geng Y. An engineered Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain binds the broadly neutralizing human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2G12 and elicits mannose-specific gp120-binding antibodies. J Virol. 2008;82:6447–6457. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00412-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mascola JR, Stiegler G, VanCott TC, Katinger H, Carpenter CB, Hanson CE, Beary H, Hayes D, Frankel SS, Birx DL, Lewis MG. Protection of macaques against vaginal transmission of a pathogenic HIV-1/SIV chimeric virus by passive infusion of neutralizing antibodies. Nat Med. 2000;6:207–210. doi: 10.1038/72318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muller WE, Bachmann M, Weiler BE, Schroder HC, Uhlenbruck G, Shinoda T, Shimizu H, Ushijima H. Antibodies against defined carbohydrate structures of Candida albicans protect H9 cells against infection with human immunodeficiency virus-1 in vitro. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1991;4:694–703. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palma AS, Feizi T, Zhang Y, Stoll MS, Lawson AM, Diaz-Rodríguez E, Campanero-Rhodes AS, Costa J, Brown GD, Chai W. Ligands for the beta-glucan receptor, Dectin-1, assigned using ‘designer' microarrays of oligosaccharide probes (neoglycolipids) generated from glucan polysaccharides. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5771–5779. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511461200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantophlet R, Burton DR. GP120: Target for neutralizing HIV-1 antibodies. Annu Rev Immunol. 2006;24:739–769. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.24.021605.090557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parren PW, Gauduin MC, Koup RA, Poignard P, Fisicaro P, Burton DR, Sattentau QJ. Relevance of the antibody response against human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope to vaccine design. Immunol Lett. 1997;57:105–112. doi: 10.1016/s0165-2478(97)00043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parren PW, Moore J, Burton DR, Sattentau QJ. The neutralizing antibody response to HIV-1: Viral evasion and escape from humoral immunity. Aids. 1999;13 Suppl A:S137–162. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrescu AJ, Petrescu SM, Dwek RA, Wormald MR. A statistical analysis of N- and O-glycan linkage conformations from crystallographic data. Glycobiology. 1999;9:343–352. doi: 10.1093/glycob/9.4.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reeves PJ, Callewaert N, Contreras R, Khorana HG. Structure and function in rhodopsin: High-level expression of rhodopsin with restricted and homogeneous N-glycosylation by a tetracycline-inducible N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase I-negative HEK293S stable mammalian cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13419–13424. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212519299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanders RW, Venturi M, Schiffner L, Kalyanaraman R, Katinger H, Lloyd KO, Kwong PD, Moore JP. The mannose-dependent epitope for neutralizing antibody 2G12 on human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein gp120. J Virol. 2002;76:7293–7305. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.14.7293-7305.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan CN, Offer J, Zitzmann N, Dwek RA. Exploiting the defensive sugars of HIV-1 for drug and vaccine design. Nature. 2007;446:1038–1045. doi: 10.1038/nature05818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan CN, Pantophlet R, Wormald MR, Ollmann Saphire E, Stanfield R, Wilson IA, Katinger H, Dwek RA, Rudd PM, Burton DR. The broadly neutralizing anti-human immunodeficiency virus type 1 antibody 2G12 recognizes a cluster of α1→2mannose residues on the outer face of gp120. J Virol. 2002;76:7306–7321. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.14.7306-7321.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scanlan CN, Ritchie GE, Baruah K, Crispin M, Harvey DJ, Singer BB, Lucka L, Wormald MR, Wentworth P, Jr, Zitzmann N, Rudd PM, Burton DR, Dwek RA. Inhibition of mammalian glycan biosynthesis produces non-self antigens for a broadly neutralising, HIV-1 specific antibody. J Mol Biol. 2007;372:16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simek MD, Rida W, Priddy FH, Pung P, Carrow E, Laufer DS, Lehrman JK, Boaz M, Tarragona-Fiol T, Miiro G, Birungi J, Pozniak A, McPhee DA, Manigart O, Karita E, Inwoley A, Jaoko W, Dehovitz J, Bekker LG, Pitisuttithum P, Paris R, Walker LM, Poignard P, Wrin T, Fast PE, Burton DR, Koff WC. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 elite neutralizers: Individuals with broad and potent neutralizing activity identified by using a high- throughput neutralization assay together with an analytical selection algorithm. J Virol. 2009;83:7337–7348. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00110-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomiyama T, Lake D, Masuho Y, Hersh EM. Recognition of human immunodeficiency virus glycoproteins by natural anti-carbohydrate antibodies in human serum. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1991;177:279–285. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(91)91979-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker LM, Phogat SK, Chan-Hui PY, Wagner D, Phung P, Goss JL, Wrin T, Simek MD, Fling S, Mitcham JL, Lehrman JK, Priddy FH, Olsen OA, Frey SM, Hammond PW, Miiro G, Serwanga J, Pozniak A, McPhee D, Manigart O, Mwananyanda L, Karita E, Inwoley A, Jaoko W, Dehovitz J, Bekker LG, Pitisuttithum P, Paris R, Allen S, Kaminsky S, Zamb T, Moyle M, Koff WC, Poignard P, Burton DR. Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies from an African donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine target. Science. 2009;326:285–289. doi: 10.1126/science.1178746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X, Decker JM, Wang S, Hui H, Kappes JC, Wu X, Salazar-Gonzalez JF, Salazar MG, Kilby JM, Saag MS, Komarova NL, Nowak MA, Hahn BH, Kwong PD, Shaw GM. Antibody neutralization and escape by HIV-1. Nature. 2003;422:307–312. doi: 10.1038/nature01470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willison HJ. The immunobiology of Guillain-Barre syndromes. J Peripher Nerv Syst. 2005;10:94–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1085-9489.2005.0010202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods RJ, Pathiaseril A, Wormald MR, Edge CJ, Dwek RA. The high degree of internal flexibility observed for an oligomannose oligosaccharide does not alter the overall topology of the molecule. Eur J Biochem. 1998;258:372–386. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2580372.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wormald MR, Petrescu AJ, Pao YL, Glithero A, Elliott T, Dwek RA. Conformational studies of oligosaccharides and glycopeptides: Complementarity of NMR, X-ray crystallography, and molecular modelling. Chem Rev. 2002;102:371–386. doi: 10.1021/cr990368i. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X, Borchers C, Bienstock RJ, Tomer KB. Mass spectrometric characterization of the glycosylation pattern of HIV-gp120 expressed in CHO cells. Biochemistry. 2000;39:11194–11204. doi: 10.1021/bi000432m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]