Abstract

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are small, usually cationic peptides, which permeabilize bacterial membranes. Understanding their mechanism of action might help design better antibiotics. Using an implicit membrane model, modified to include pores of different shapes, we show that four AMPs (alamethicin, melittin, a magainin analogue, MG-H2, and piscidin 1) bind more strongly to membrane pores, consistent with the idea that they stabilize them. The effective energy of alamethicin in cylindrical pores is similar to that in toroidal pores, whereas the effective energy of the other three peptides is lower in toroidal pores. Only alamethicin intercalates into the membrane core; MG-H2, melittin and piscidin are located exclusively at the hydrophobic/hydrophilic interface. In toroidal pores, the latter three peptides often bind at the edge of the pore, and are in an oblique orientation. The calculated binding energies of the peptides are correlated with their hemolytic activities. We hypothesize that one distinguishing feature of AMPs may be the fact that they are imperfectly amphipathic which allows them to bind more strongly to toroidal pores. An initial test on a melittin-based mutant seems to support this hypothesis.

Keywords: molecular dynamics simulations, antimicrobial peptides, toroidal pore, barrel-stave pore, implicit solvent

Introduction

Antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are found throughout the animal and plant kingdoms as components of the innate immune system [1–3]. They are usually small, cationic peptides that exhibit a broad spectrum of antimicrobial activity, acting against bacteria, fungi, HIV, and even cancer cells [1, 2, 4–8]. To take advantage of their promising therapeutic potential [9], it is crucial to understand the origin of their cell selectivity and their mechanism of action. In the prevailing view, the cell selectivity of AMPs is related to differences between prokaryotic and eukaryotic membranes; anionic membranes of bacteria are usually targeted by cationic peptides although other factors can also contribute to the selectivity [6, 10, 11].

AMPs are believed to bind to a membrane surface below a threshold peptide-to-lipid ratio; at higher ratios, they form pores, resulting in membrane depolarization and leakage of cell components and eventually cell death [12, 13], or induce membrane disintegration and/or micellization (the carpet mechanism) [14]. Two types of pores have been proposed: barrel-stave, i.e. cylindrical pores lined by peptides (as proposed for alamethicin) [15, 16], and toroidal pores lined by a mixture of peptides and lipid headgroups (proposed, for instance, for magainin 2, piscidin 1 and melittin) [17–21].

Computer simulations promise to be a useful tool in studying antimicrobial peptides since they can provide detailed information on the structure and dynamics of systems. Alamethicin, a 20-residue α-helical peptide characteristic for its high content of non-standard α-methylalanine (Aib) residues, has been intensively studied by MD simulations [22–29]. Several atomistic MD studies of melittin, a 26-residue α-helical peptide, have also been reported [30–32]. Of special interest are recently reported atomistic MD simulations of pore formation induced by magainin analogue MG-H2 [33] and melittin [34], as well as combined coarse-grained and atomistic simulations of pores produced by alamethicin [35]. These studies suggest that a picture of cylindrical and toroidal pores as highly ordered structures, which was proposed from experiments [15–17, 19–21, 36], might be inaccurate; pores observed in the simulations are fairly disordered, with peptides in tilted orientations, not perfectly perpendicular to the membrane surface. In the case of MG-H2 and melittin, only one or two peptides were found at the center of the pore and others were parallel to the membrane surface near the rim of the pore. In our companion atomistic MD study, we explored preferences of alamethicin and melittin for cylindrical and toroidal pores and showed that curved pores enhance interactions of melittin with lipids [37].

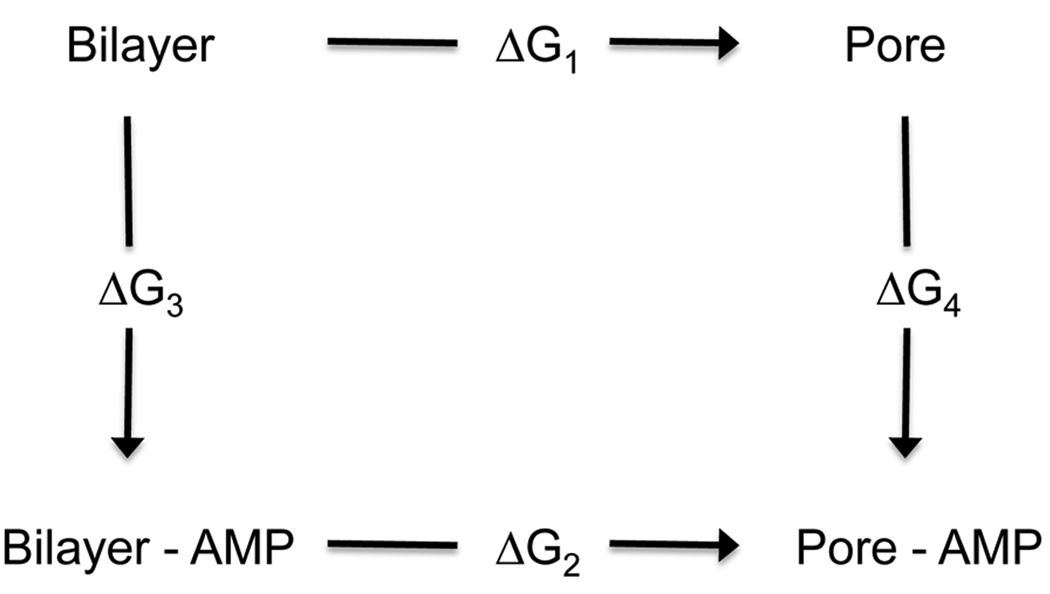

Despite the large volume of experimental work and the recent progress in computational studies, a clear conceptual framework for the mechanism of action of AMPs is lacking. One key element of most proposed mechanisms is the pore state, which could be either a stable/metastable state or a transient structure corresponding to a “transition state”. We reason that if AMPs stabilize the pore state, then they must bind more strongly to it than to the flat bilayer. This can be illustrated by the thermodynamic cycle of Figure 1. If AMPs facilitate the formation of pores (ΔG2 < ΔG1), then the binding of AMPs to pores must be more favorable than the binding to flat bilayers (ΔG4 < ΔG3). The difference ΔG4 − ΔG3, which is equal to ΔG2 − ΔG1, could be used as a well-defined measure of the extent to which an AMP stabilizes the pore state. If pore formation is key to antimicrobial activity, this difference should also be a measure of activity. The above is merely a thermodynamic analysis and does not imply a certain kinetic pathway. That is, it does not imply that the pore must first form spontaneously, followed by the binding of the peptides to it. Actually, this is highly unlikely, as spontaneous formation of pores should be very rare.

Figure 1.

Thermodynamic cycle for binding of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) to pores.

The stronger binding of peptides to pores could be due to packing reasons: lipid headgroups are less tightly packed in pores and could accommodate a peptide more easily. Alternatively, the peptide could be better solvated on a curved membrane surface. In this paper we test the latter hypothesis, by performing molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of alamethicin [38], melittin [39, 40], magainin analogue MG-H2 [41] and piscidin 1 [18] in implicit-solvent cylindrical or toroidal pores and calculating their binding energies on a flat membrane and in pores. Such investigations are difficult using atomistic MD simulations, especially when computation of free energies is required. We, thus, resort here to a modified version of the implicit membrane model IMM1 [42, 43], which provides rapid equilibration of systems and a facile calculation of effective energies, without the large noise coming from water and lipid molecules. Although some type of aggregation of AMPs seems to be a requirement for activity, in this work we study single peptides. Aggregation may be required simply because the amount of stabilization that one peptide provides is not sufficient. It is worth noting that recent atomistic MD simulations [33, 34] showed that only 1 or 2 peptides are usually inserted in the observed pores.

Alamethicin is known to act via the barrel-stave [15, 16, 35] whereas melittin and MG-H2 act via the toroidal pore mechanism [17, 21, 33, 34, 36]. Although magainin 2 has been studied more extensively than MG-H2 [19, 20, 44], we have chosen the latter peptide for our study because of its higher affinity for zwitterionic membranes [41]. Pores produced by piscidin 1, a 22-residue α-helical peptide isolated from mast cells of fish [7], have not been characterized yet but, based on conductance experiments, it was proposed that piscidin 1 forms toroidal pores [18]. Here we show that the binding energies of the peptides can be used to discriminate their preferences for different pores. All four peptides are reported to be hemolytic, alamethicin being the least and melittin the most hemolytic [7, 41, 45]. Since the effective binding energies are calculated on zwitterionic membranes (similar to membranes of erythrocytes [46]), we relate them to the hemolytic activity of the peptides. Finally, we point out a possible connection between imperfectly amphipathic structures of AMPs and their mode of action.

Methods

IMM1-Torus

The effective energy of peptides on flat membranes is obtained using the implicit model IMM1 [42]. In IMM1 the effective energy of a protein in a lipid bilayer (WIMM1) is calculated as the sum of the intramolecular energy of the solute (E) [47] and the implicit solvation free energy (ΔGslv) accounting for interactions of each atom with water and with cyclohexane, which approximates the hydrophobic core of the membrane:

| (1) |

The implicit solvation energy has the form:

| (2) |

where is the solvation free energy of atom i, rij is the distance between atoms i and j, gi is the solvation free energy density of i, modeled as a Gaussian function of rij, Vj is the volume of atom j. The solvation energy of an isolated atom, , is obtained as a linear combination of values for water and for cyclohexane :

| (3) |

where z′=|z|/(T/2), T is the thickness of the membrane core, and f(z′) is the function that describes the transition from one phase to the other:

| (4) |

The steepness of the transition is determined by the exponent n.

To account for the strengthening of electrostatic interactions in the membrane, a distance dependent dielectric constant, ε, has been modified in IMM1 by introducing the function that depends on the position of the interacting atoms with respect to the membrane,fij:

| (5) |

and

| (6) |

where a is an adjustable parameter.

IMM1 has been extended to model membrane proteins with embedded cylindrical aqueous channels (IMM1-pore [43]). In this model, the function f(z′) has been replaced by the function F(z′,r′) that depends both on the position of atoms relative to the center of the membrane (z’) and relative to the center of the pore (r’):

| (7) |

with

| (8) |

where the radius of the pore, R, is constant. Thus, the solvation free energy of an isolated atom is now:

| (9) |

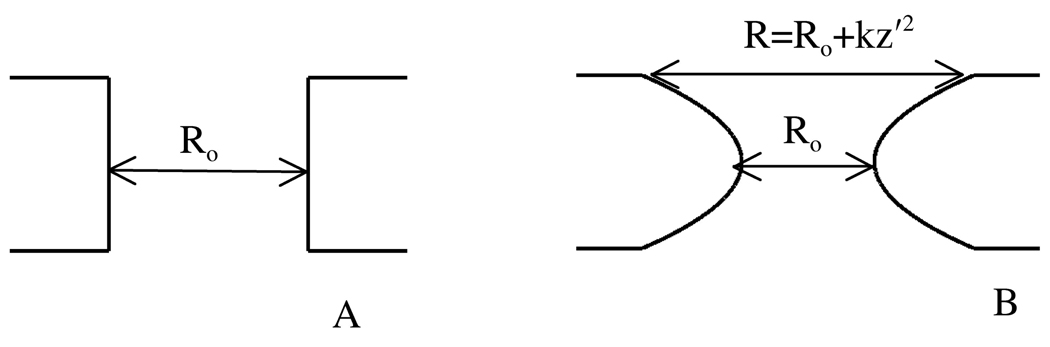

In this paper, we have made IMM1-pore applicable to different shapes of pores by allowing the radius of the pore to depend on the distance from the center of the membrane, along the membrane normal. We refer to this model as IMM1-torus. Although a circular pore would be the natural choice for a torus, a parabolic pore has a computationally cheaper mathematical form and allows greater flexibility in determining pore shape:

| (10) |

where Ro is the radius of the pore at the center of the membrane and k defines the curvature (i.e., the shape) of the pore (see Figure 2). For example, Ro=15Å and k=0 defines a cylindrical pore of radius R=15 Å whereas Ro= 15Å and k=20 defines a toroidal pore with the radius in the center of the pore of 15Å and the radius at the ends of the pore of 35Å (which would correspond to the geometry of pores produced by magainin [19, 48]). Clearly, very large values of k are unphysical.

Figure 2.

Geometry of a cylindrical (A) and a parabolic (B) pore. The solid lines represent the hydrophobic/hydrophilic interface.

IMM1-torus is applicable to zwitterionic membranes. Thus, there are no peptide-membrane electrostatic interactions, only intra-peptide ones.

Initial structures

The coordinates for alamethicin, melittin and piscidin 1 were obtained from the Protein Data Bank, entries 1AMT [38], 2MLT [39, 40], and 2JOS [18], respectively; an analogue of magainin 2, MG-H2 [41] was built as an ideal α-helix. The sequence of alamethicin is: Ace-Aib-Pro-Aib-Ala-Aib-Ala-Gln-Aib-Val-Aib-Gly-Leu-Aib-Pro-Val-Aib-Aib-Glu-Gln-Phl, where Ace is acetylated N-terminus, Aib is α-methylalanine and Phl is phenylalaninol; the sequence of melittin is: Gly-Ile-Gly-Ala-Val-Leu-Lys-Val-Leu-Thr-Thr-Gly-Leu-Pro-Ala-Leu-Ile-Ser-Trp-Ile-Lys-Arg-Lys-Arg-Gln-Gln; the sequence of MG-H2 is: Ile-Ile-Lys-Lys-Phe-Leu-His-Ser-Ile-Trp-Lys-Phe-Gly-Lys-Ala-Phe-Val-Gly-Glu-Ile-Met-Asn-Ile; the sequence of piscidin is: Phe-Phe-His-His-Ile-Phe-Arg-Gly-Ile-Val-His-Val-Gly-Lys-Thr-Ile-His-Arg-Leu-Val-Thr-Gly. All charged residues were in the standard ionization state corresponding to pH ~7.

Simulation setup

The membrane is taken to be parallel to the xy-plane, with its center located at z=0 Å and the hydrocarbon core 26 Å wide. The peptide was first aligned with the x-axis. Four simulations were run starting from four arbitrary orientations, obtained by rotating the peptide 90° around the x-axis. The peptide, in each of the four orientations, was then either placed on the membrane surface (its center of mass at z=13 Å) or was rotated 90° to assume the transmembrane orientation and placed on the pore surface (its center of mass at x=Ro Å, corresponding to the radius in the center of the pore). The energy of the peptide was minimized using the adopted basis Newton-Raphson algorithm for 300 steps. For simulations in pores, the miscellaneous mean field potential (MMFP) was used to constrain the center of mass of the peptide in the pore region (that is, to a cylinder of 10 Å radius, with the axis of the cylinder along the x-axis), which allowed us to calculate binding energies in the pores. MD simulations were run for 1-ns using the Verlet integrator with a time step of 2 fs, at room temperature, with all bonds involving hydrogen atoms fixed using SHAKE constraints. The energy was averaged over the last 500 ps of four trajectories, generated using four different seeds to initialize velocities, with the MMFP constraint energy removed. The average energy was compared with the energies of the structures obtained from the other three simulations; the optimal orientation relative to the membrane corresponded to that which yielded the lowest average energy. The binding energy, ΔΔW, is calculated as the difference between the effective energy of transfer of the peptide from solution to the pore (ΔWpore) and that from solution to the flat membrane (ΔWintf), where ΔW is the difference between the average effective energy of the peptide in the pore or on the membrane and the energy of the same conformation of the peptide transferred, along the z-axis, from the membrane to solvent. Although the peptides are unstructured in solvent, to minimize statistical error in the calculation of ΔΔW we assume that they are in the same conformation and thus consider the transition from “helix in water” to “helix on the membrane/in the pore”. Given that the calculated helical content of a monomer on the membrane and in the pore is similar (alamethicin: 73–75%, MG-H2: 76–79%, melittin: 73–79%, piscidin: 78–82%), the free energy of helix formation in solution cancels out in the calculated ΔΔW. Thus, ΔΔW is an estimate for the quantity ΔG4 − ΔG3 in the thermodynamic cycle of Figure 1.

Results

The interface in Figure 2 corresponds to the hydrophobic/hydrophilic interface. In the case of a cylindrical pore, this is a hydrocarbon/water interface and in the case of a toroidal pore a hydrocarbon/lipid headgroup interface. To choose appropriate values for the Ro and k parameters, we surveyed the available experimental structural data for peptide-induced membrane pores.

Using neutron scattering, Huang and co-workers determined the effective inner (Rw) and outer (Rp) radii of pores produced by several AMPs. Rw is the radius of the water pore in the center of the membrane and is calculated from the contrast form factor Fϕ (qz=0, qr). Rp is the outside radius of the pore and is calculated from the contact distance between two pores. They obtained the values of Rw~9 Å and Rp~20 Å for alamethicin [16], Rw~15–25 Å and Rp~35–42 Å for magainin [19, 48], and Rw~22 Å and Rp~38 Å for melittin [21]. However, the inner radius of pores determined in leakage measurements was significantly smaller: ~10–15 Å for magainin and MG-H2 pores [20, 41], and 6.5–12 Å [36] or 12.5–15 Å [49] for melittin pores. Given the above experimental data, we chose the values of the radius at the center of a pore (Ro) of 15, 20 or 25 Å, and the values of the variable k in Eq. (10) of 0 (corresponding to a cylindrical pore), 10, 15 or 20. Thus, the inner radius of a “barrel stave” pore with the helices lining the inside of the pore is Rw = Ro − 11 Å (assuming that the diameter of a helix is 11 Å) and its outer radius is Rp = Ro; the inner radius of a toroidal pore lined with headgroups is Rw = Ro − 9 Å (assuming the thickness of the headgroup region is 9 Å) and the outer radius is Rp=Ro+k (at the membrane surface, z’=1).

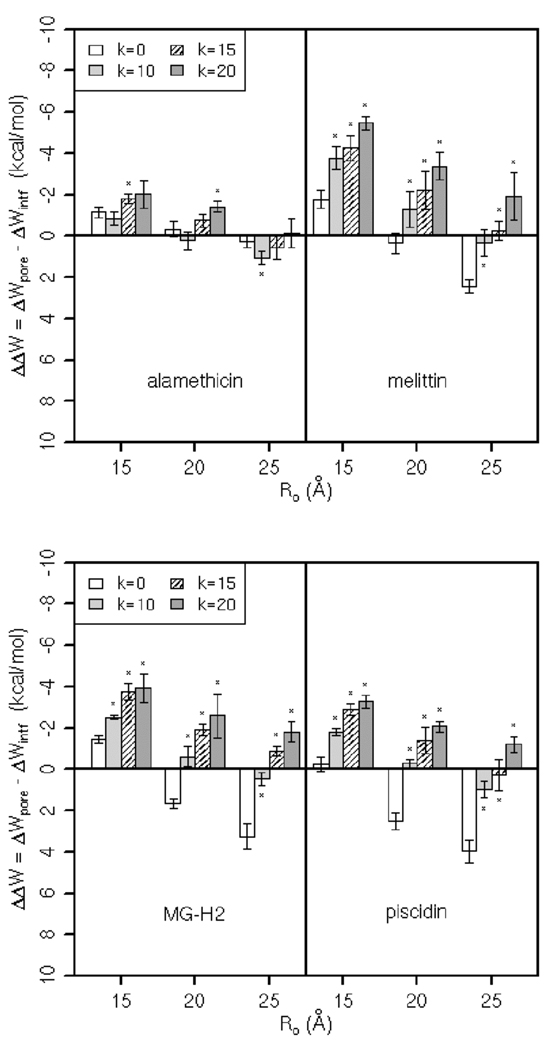

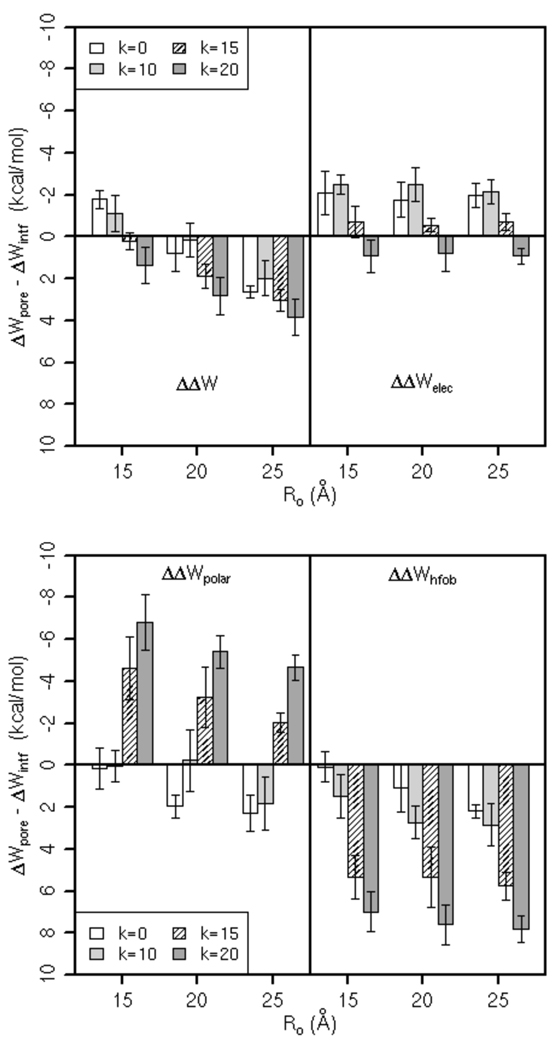

Figure 3 shows the binding energy of alamethicin, melittin, MG-H2, and piscidin 1 in pores, ΔWpore, relative to that on the flat membrane (ΔWintf), ΔΔW. For each peptide, there are three sets of ΔΔW calculated in pores of different radii (Ro is given on the x-axis) and shapes (the first bar in a set corresponds to a cylindrical pore; the other three bars correspond to toroidal pores of different curvature, as indicated in the legend). We used a two-tailed Student’s t-test to determine significant differences between ΔΔW in each toroidal pore and ΔΔW in the cylindrical pore of the same Ro; p value < 0.05 is indicated by asterisk in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

The relative binding energies of the peptides in the pores of radius Ro (Å) and the curvature determined by k (k=0 corresponds to a cylindrical pore). Error bars are the standard deviation. A two-tailed Student’s t-test was used to determine significant differences between ΔΔW in each toroidal pore and ΔΔW in the cylindrical pore of the same Ro; p value < 0.05 is denoted by asterisk.

In general, the peptides bind more strongly to pores of Ro=15 Å than to the larger pores. However, the affinity of the peptides for flat versus curved pores differs. Alamethicin seems to bind a bit stronger to toroidal pores of Ro=15, k=15 and of Ro=20, k=20 than to the cylindrical pore of the same radius, but the difference in ΔΔW is rather small. Hence, these data suggest that alamethicin does not show a clear preference for cylindrical versus toroidal pores. The relative binding energies of melittin, MG-H2 and piscidin are, however, more conclusive. As Figure 3 testifies, these peptides always bind more strongly to curved pores than to flat pores. This trend in binding affinities coincides with the prevailing view that alamethicin forms cylindrical pores [15, 16, 35] whereas melittin and MG-H2 (and magainin 2 as well) form toroidal forms [17, 19–21, 33, 36, 41]; based on conductance experiments, it was proposed that piscidin 1 also forms toroidal pores [18].

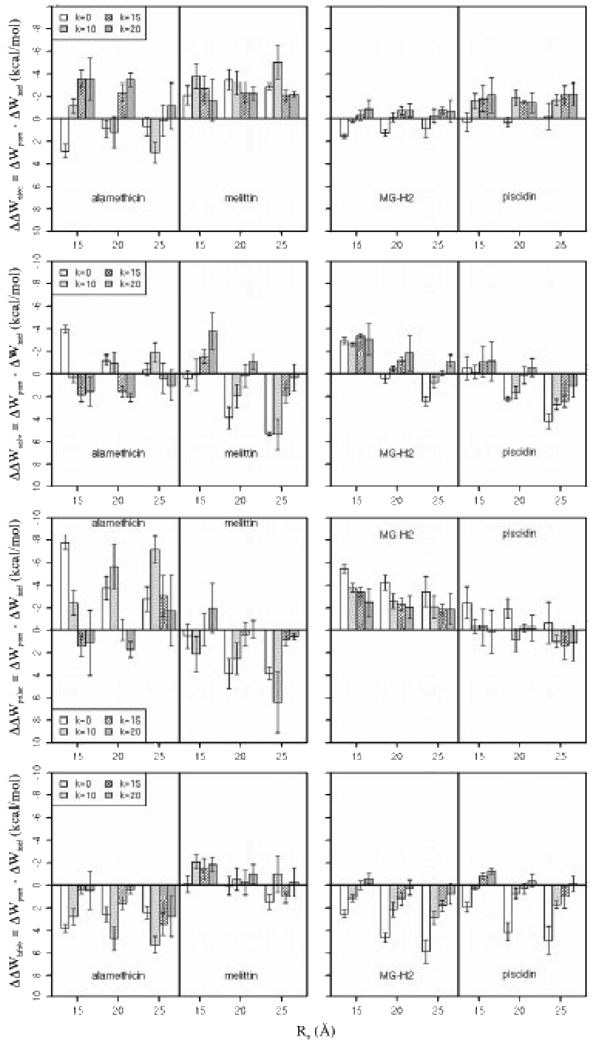

To gain more insight into why the binding affinities of the peptides depend on the pore shape, we decomposed ΔΔW into (intramolecular) electrostatic energy (ΔΔWelec) and solvation energy (ΔΔWsolv) contributions. In Figure 4, the two plots in the first row display contributions from the electrostatic energy to the relative binding energy of the peptides in different pores. With a few exceptions, the electrostatic energy of the peptides is comparable to or more favorable in pores than that on the flat membrane (without a pore). As can be seen in Figure 5, which shows the energy-minimized average structure of the peptides on the flat membrane and in the pores, helices are more inserted in the hydrocarbon core of pores than when adsorbed on the membrane, which gives rise to the strengthening of electrostatic interactions. The plots in the second row of Figure 4 show contributions to ΔΔW from the solvation energy. Alamethicin is better solvated in cylindrical than in curved pores (or on the flat membrane) but its electrostatic energy is more favorable in curved pores. On the other hand, melittin, MG-H2 and piscidin are better solvated in toroidal pores; the trend in electrostatic energy of MG-H2 and piscidin is similar, but it is not obvious in the case of melittin.

Figure 4.

Contributions from the electrostatic (ΔΔWelec) and solvation energy (ΔΔWsolv) to the relative binding energy of peptides in different pores, as well as contributions from polar (ΔΔWpolar) and aliphatic and aromatic groups (ΔΔWhfob) to ΔΔWsolv. Error bars are the standard deviation. The radius of the pores, Ro, is in Å. The curvature of the pores is determined by k; the smaller the k, the smaller the curvature; k=0 corresponds to a cylindrical pore.

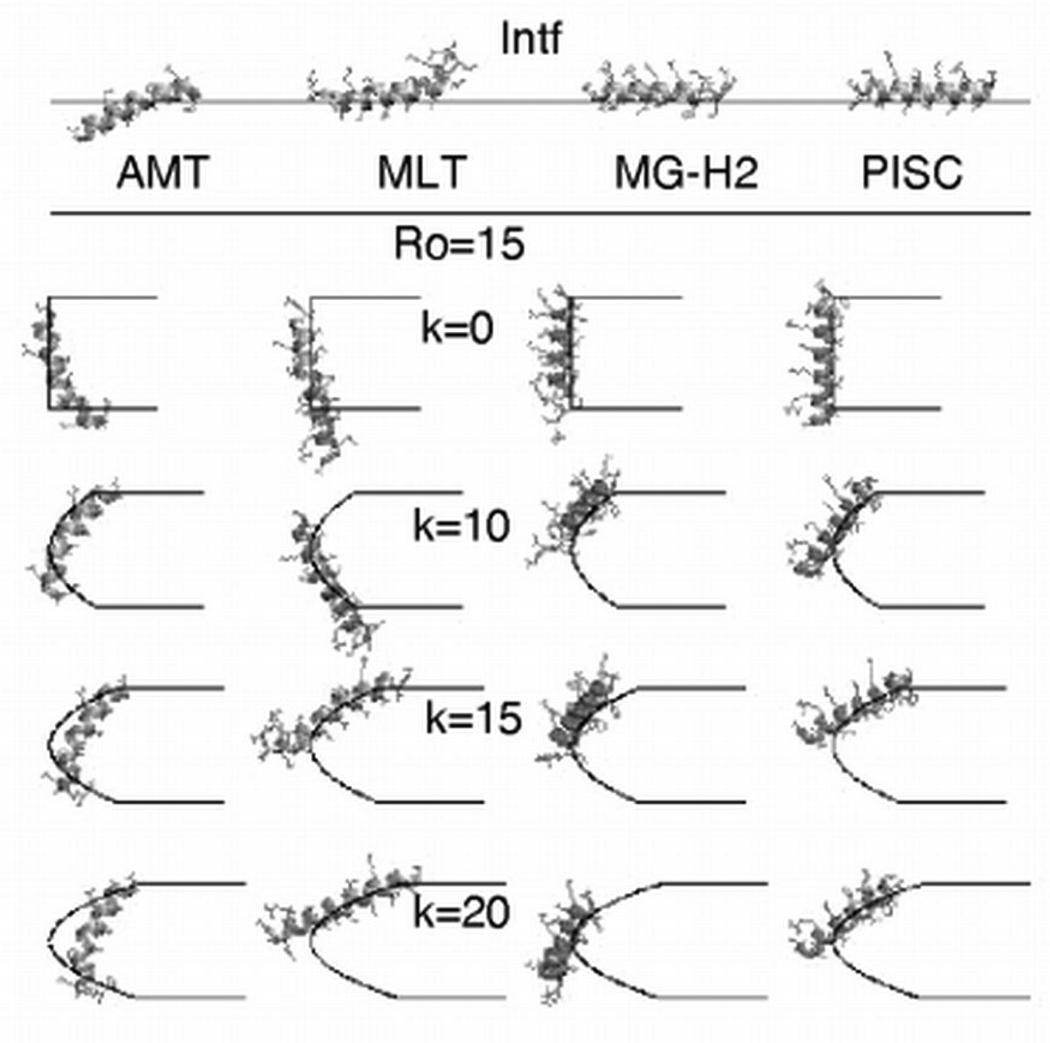

Figure 5.

The optimal orientation of alamethicin, melittin, MG-H2 and piscidin on the flat membrane (intf) and in the pores of Ro=15 Å. The energy-minimized average structure is calculated from a MD simulation between 0.5 ns and 1 ns. The hydrophilic/hydrophobic interface is denoted by lines; only one side of the pore is shown.

We further decomposed ΔΔWsolv into contributions from polar (ΔΔWpolar) and aliphatic and aromatic (ΔΔWhfob) groups, shown in the third and forth row in Figure 4, respectively. For alamethicin, when compared to the flat membrane, the presence of pores does not improve solvation of hydrophobic residues but improves solvation of polar residues. In pores, the trend in the solvation energy of polar residues depends on the pore shape and size; it is significantly more favorable in the cylindrical pore of Ro = 15 Å than in the toroidal pores of the same radius at the center of the pore, but it is erratic in larger pores. Hydrophobic residues of melittin are better solvated in pores than on the flat membrane, especially in toroidal pores of Ro = 15 Å; the solvation energy of polar residues, however, has the opposite trend. In the case of MG-H2, toroidal pores enhance solvation of hydrophobic groups; polar groups are better solvated in all pores, but there is a decreasing trend in curved pores. For piscidin 1, which has a large portion of aromatic residues (Phe and His), toroidal pores improve solvation of hydrophobic residues whereas the solvation of polar groups is somewhat better in cylindrical pores. Therefore, these data suggest that cylindrical pores enhance solvation of polar residues of alamethicin whereas toroidal pores improve solvation of hydrophobic groups of melittin, MG-H2 and piscidin.

Hemolytic activity

It is usually thought that selectivity of AMPs for prokaryotic over eukaryotic cells is due to electrostatic interactions between cationic peptides and anionic lipid headgroups and that their hemolytic activity is due to hydrophobic effects. For instance, in a study by Dathe et al. on cationic model peptides, enhanced peptide-lipid electrostatic interactions increased antibacterial activity of the peptides whereas reduced electrostatic interactions and enhanced hydrophobic peptide-membrane interactions increased hemolytic activity [50]. Since the outer leaflet of the human erythrocyte membrane consists of neutral lipids [46], we now attempt to correlate the effective binding energies of the peptides to neutral membranes to their hemolytic activity.

The calculated average binding energies of the peptides bound to the flat membrane in the interfacial orientation (ΔWintf), in the cylindrical pore of Ro = 15 Å (ΔWcyl) and in the toroidal pore of Ro = 15 Å and k = 20 (ΔWtorus) are given in Table 1. Here we show ΔW’s for the pore of Ro = 15 Å and k = 20 only because the peptides bind more strongly to this pore (see Figure 3); the same trends are, however, observed in the other pores (data not shown).

Table 1.

The average effective binding energies of the peptides in the interfacial orientation on the flat membrane (ΔWintf), in the cylindrical pore of Ro=15 Å (ΔWcyl) and in the toroidal pore of Ro=15 Å and k = 20 (ΔWtorus). All energies are in kcal/mol. Error bars are the standard deviation.

| peptide | ΔWintf | ΔWcyl | ΔWtorus | EC50 (µM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| alamethicin | −9.38 ± 0.30 (−27.48 ± 0.48, 18.10 ± 0.19)a |

−10.52 ± 0.14 (−23.68 ± 0.30, 13.16 ± 0.17) |

−11.40 ± 0.50 (−27.03 ± 1.34, 15.64 ± 0.93) |

30b |

| MG-H2 | 9.52 ± 0.15 (−20.44 ± 0.30, 10.93 ± 0.17) |

−10.96 ± 0.19 (−17.91 ± 0.35, 6.96 ± 0.22) |

−13.45 ± 0.73 (−21.02 ± 0.40, 7.57 ± 0.34) |

16c |

| piscidin 1 | −10.39 ± 0.11 (−19.55 ± 0.18, 9.15 ± 0.08) |

−10.65 ± 0.32 (−17.62 ± 0.28, 6.97 ± 0.49) |

−13.66 ± 0.35 (−20.81 ± 0.23, 7.15 ± 0.46) |

~12d |

| melittin | −12.90 ± 0.53 (−23.33 ± 0.71, 10.43 ± 0.22) |

−14.66 ± 0.24 (−23.48 ± 0.45, 8.83 ± 0.27) |

18.38 ± 0.57 (−25.20 ± 0.69, 6.82 ± 0.20) |

~1.7e |

In all three cases, alamethicin has the highest binding energy whereas the binding energy of melittin is the lowest; the binding energies of MG-H2 and piscidin 1 are in between. The same trend has been reported for their hemolytic activities, with alamethicin being the least hemolytic and melittin the most [7, 41, 45]. In Table 1, we have also included the contribution of solvation energy of aliphatic and aromatic groups to the total binding energy, and the sum of contributions from the electrostatic energy and solvation energy of polar groups. Obviously, the largest contribution to the total ΔW comes from the solvation of hydrophobic residues, which suggest that hemolytic activity is likely determined by hydrophobic interactions as well.

Structure and orientation of peptides in pores

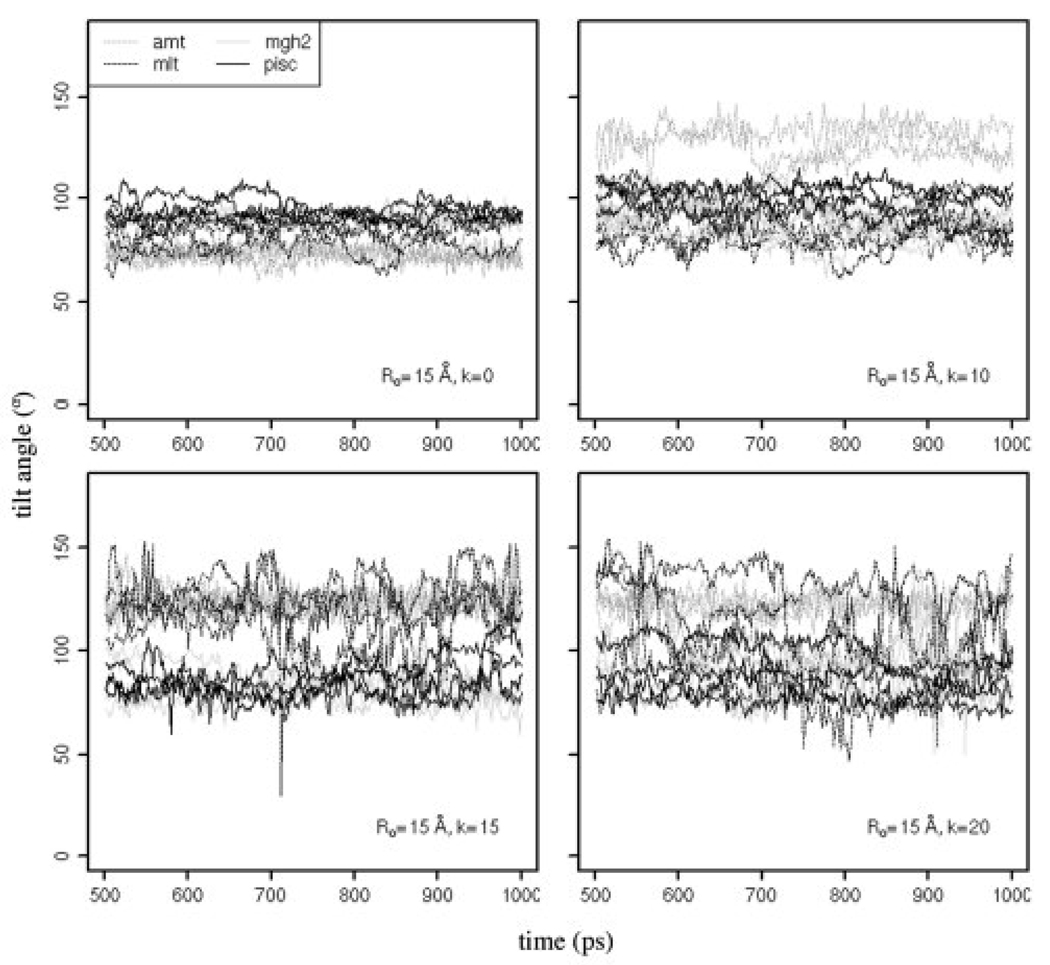

The energy-minimized average structure of the peptides on the flat membrane and in the pores, calculated from MD trajectories, is shown in Figure 5. During the MD simulations, the peptides retain their helical structure but change orientation with respect to the membrane from an initial perpendicular orientation to a tilted orientation. The tilt angle of the peptides in cylindrical and toroidal pores of Ro = 15 Å versus time is shown in Figure 6 (the tilt angle is calculated as the angle between the helix axis and the membrane surface). In cylindrical pores, the average tilt angle of alamethicin is ~75°; the other three peptides are almost perpendicular. In toroidal pores, the peptides are occasionally almost perpendicular to the membrane surface but tilted orientations are far more common.

Figure 6.

Tilt angle of alamethicin, melittin, MG-H2 and piscidin vs. time, in the selected pores. The four lines in the same color represent the tilt angle calculated from 4 MD trajectories generated using different seeds.

To understand better why the peptides tend to be oriented obliquely to the membrane surface, we performed MD simulations of melittin in cylindrical and toroidal pores in which we used MMFP to constrain the peptide to a transmembrane orientation (that is, we constrained the Cα atoms to a cylinder of 7 Å radius centered at (Ro, 0, 0), with the axis of the cylinder along the z-axis). The binding energy of the protein (ΔΔW) and its components (ΔΔWelec, ΔΔWpolar and ΔΔWhfob) are shown in Figure 7; ΔΔWsolv can be obtained as the sum of ΔΔWpolar and ΔΔWhfob. It seems that hydrophobic residues are better solvated in a tilted than in the perpendicular orientation (i.e., for melittin in the transmembrane orientation, ΔΔW is unfavorable, mostly because of the unfavorable solvation energy).

Figure 7.

The relative binding energies of melittin confined to the transmembrane orientation in the pores of radius Ro (Å) and the curvature determined by k (k=0 corresponds to a cylindrical pore). Error bars are the standard deviation.

In our simulations only alamethicin is observed to insert deeper in the membrane core. The other three peptides are located at the pore-water interface. This difference in location is probably related to differences in apolar faces of the helices (alamethicin has a broader apolar face than other three peptides) [41, 51, 52].

Discussion

In this work we used molecular dynamics simulations with implicit membrane to investigate binding preferences of antimicrobial peptides. A previously developed and tested implicit membrane model with a cylindrical pore (IMM1-pore [43]) has been modified to include implicit toroidal pores. From MD trajectories, we calculated the effective binding energies of alamethicin, melittin, MG-H2 and piscidin 1 when adsorbed on a flat membrane and when inserted in cylindrical and toroidal pores of different size and curvature. The key findings of the study are: (1) the binding energy of the peptides in pores is more favorable than that on the flat membrane, (2) alamethicin binds similarly to cylindrical and toroidal pores, (3) melittin, MG-H2 and piscidin 1 bind strongly to toroidal pores, and (4) the effective binding energies of the four peptides correlate with their hemolytic activity.

The calculated binding energies appear to correctly predict preferences of alamethicin for cylindrical pores [15, 16, 35] and of melittin, MG-H2 and piscidin 1 for toroidal pores [17, 18, 21, 33, 36, 41]. The results presented here also agree well with our recent atomistic MD simulations of alamethicin and melittin in cylindrical and toroidal pores [37]. In that study, we observed that, when inserted in a pre-formed toroidal pore, alamethicin tetramer remodeled the pore to a cylindrical one whereas melittin tetramer preserved the toroidal pore shape. We used the calculated interaction energy between the peptides and lipids to argue that, for melittin, they are stronger in toroidal than in cylindrical pores. Here, we show that melittin monomer is also better solvated in curved pores.

Orientation of peptides in pores

During the MD simulations, we observed that initial transmembrane orientation of the peptides changes to a variety of tilted orientations (as shown in Figure 5 and Figure 6). This observation contrasts sharply with a picture of antimicrobial pores derived from oriented circular dichroism (OCD), in which peptides are oriented perpendicular to the membrane surface [19–21]. However, tilted orientations of peptides in pores have been reported by other computational studies as well as some experimental ones. A MD simulation of a melittin pore reported a tilt angle of ~30°, with respect to the membrane normal [32]. More recent MD simulations of MG-H2 showed the formation of irregular toroidal pores with only one monomer located in the center of the membrane, with the average tilt angle of the peptides of 25° ± 20°, with respect to the membrane surface [33]. A similar pore has been produced by melittin in MD simulations, with the inserted peptides tilted 45° to 90° with respect to the membrane surface [34]. In coarse-grained MD simulations of alamethicin, a broad spectrum of orientations has been reported, ranging from ~20° to ~90° [35]. In our atomistic MD simulations of alamethicin and melittin monomers and oligomers in cylindrical and toroidal pores, we also observed a variety of tilted orientations [37]. An experimental study of the kinetics of dye release suggested that cecropin A forms pores in which monomers are not well organized and may be distributed both in a pore and on a membrane surface [53]. Matsuzaki and co-workers reported that magainin 2-PGLa heterodimers form toroidal pores in zwitterionic membranes; using Fourier transform infrared-polarized attenuated total reflection (FTIR-PATR) spectroscopy, they determined that the heterodimers are in oblique orientations relative to the membrane surface [54]. The disagreement between these studies and the OCD studies might be due to an assumption that only two orientations of the helix are possible (parallel and perpendicular), used in analyzing the OCD data.

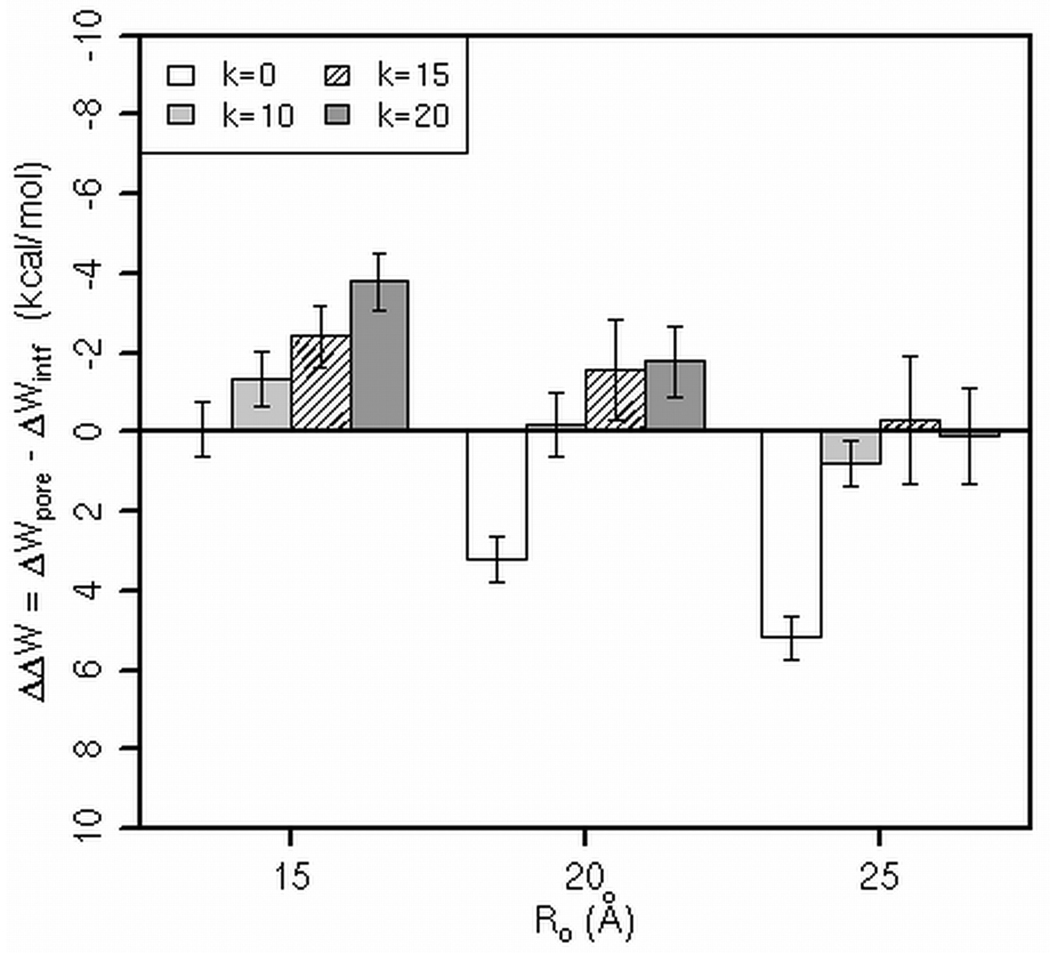

Imperfect amphipathicity

What distinguishes AMPs from other cationic peptides that lack antimicrobial activity is an important, open question. For example, Sengupta et al. [34] found that KALP peptides, despite their high charge density, did not make pores in their simulation studies. We noticed that a common feature of the four peptides studied here is their imperfectly amphipathic structure. The α-helical wheels reveal that melittin, MG-H2 and piscidin 1 have a few polar (or even charged) residues in the nonpolar face and vice versa [41, 51, 52]. These polar residues may interfere with insertion of hydrophobic residues into flat membranes, but less so in toroidal pores. As a first test of this hypothesis, we designed a melittin-based perfectly amphipathic helix (A4S, V8T, G12A, P14Y, A15S, K23A, R24A) and calculated that its relative binding energies in the pores are significantly reduced compared to ΔΔW of melittin in the same pore (see Figure 8). These results suggest that imperfect amphipathicity may play a role in antimicrobial activity and can serve as basis for design of novel antimicrobial peptides. Clearly, many more tests are needed to validate this hypothesis, especially in anionic membranes that better resemble bacterial membranes. We would expect this effect to be stronger in anionic membranes because, in addition to the solvation effects, there would be favorable interactions of the cationic residues on the hydrophobic side of the peptides with the anionic charge of the membrane.

Figure 8.

The relative binding energy of a perfectly amphipathic melittin-based mutant in the pores of radius Ro (Å) and the curvature determined by k (k=0 corresponds to a cylindrical pore). Error bars are the standard deviation.

IMM1-torus is a fast method that can easily provide energetics of biological systems. However, it cannot capture all details of complex membrane systems. For instance, IMM1-torus does not account for membrane deformations and lipid repacking (which, in principle, might be included using elasticity theory [55, 56] or mean field theory [57]) and it does not allow the shape of pore to change. Therefore, it cannot be used to study events that lead toward pore formation (such as, membrane thinning, expansion of the lipid headgroups and bending of the bilayer) or pore formation per se. However, it can provide information on how well the peptide is solvated on a membrane or in a static pore. When interpreting the calculated effective energy, one should keep in mind that it includes the intramolecular energy of peptides and the solvation free energy only; it does not include the translational, rotational and conformational entropies and thus differs from the free energy. The results presented here need to be confirmed with atomistic MD simulations (some of which are reported in our companion paper [37] and some are in progress) and experiment.

Acknowledgment

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation (MCB-0615552) and the NIH (SC1GM087190). Infrastructure support was provided in part by RCMI grant RR03060 from NIH.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Maja Mihajlovic, Email: maja@sci.ccny.cuny.edu, Department of Chemistry, The City College of New York, 160 Convent Ave, New York, NY 10031, Phone: (212) 650-8364, Fax: (212) 650-6107.

Themis Lazaridis, Email: tlazaridis@ccny.cuny.edu, Department of Chemistry, The City College of New York, 160 Convent Ave, New York, NY 10031, Phone: (212) 650-8364, Fax: (212) 650-6107.

References

- 1.Hancock REW. Cationic peptides: effectors in innate immunity and novel antimicrobials. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2001;1:156–164. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(01)00092-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown KL, Hancock REW. Cationic host defense (antimicrobial) peptides. Curr. Opin. Immunol. 2006;18:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brogden K. Antimicrobial peptides: Pore formers or metabolic inhibitors in bacteria? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2005;3:238–250. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Papo N, Shai Y. Host defense peptides as new weapons in cancer treatment. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2005;62:784–790. doi: 10.1007/s00018-005-4560-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bechinger B. Structure and function of membrane-lytic peptides. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2004;23:271–292. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Matsuzaki K. Control of cell selectivity of antimicrobial peptides. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1788:1687–1692. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Silphaduang U, Noga EJ. Peptide antibiotics in mast cells of fish. Nature. 2001;414:268–269. doi: 10.1038/35104690. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cole AM. Antimicrobial peptide microbicides targeting HIV. Protein Pept. Lett. 2005;12:41–47. doi: 10.2174/0929866053406101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bradshow JP. Cationic antimicrobial peptides. Issues for potential clinical use. Biodrugs. 2003;17:233–240. doi: 10.2165/00063030-200317040-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsuzaki K, Sugishita K, Fujii N, Miyajima K. Molecular basis for membrane selectivity of an antimicrobial peptide, magainin 2. Biochemistry. 1995;34:3423–3429. doi: 10.1021/bi00010a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Matsuzaki K. Why and how are peptide-lipid interactions utilized for self-defense? Magainins and tachyplesins as archetypes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1999;1462:1–10. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(99)00197-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Huang HW. Action of antimicrobial peptides: Two-state model. Biochemistry. 2000;39:8347–8352. doi: 10.1021/bi000946l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Huang HW. Molecular mechanism of antimicrobial peptides: The origin of cooperativity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2006;1758:1292–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oren Z, Shai Y. Mode of action of linear amphipathic alpha-helical antimicrobial peptides. Biopoly. 1998;47:451–463. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0282(1998)47:6<451::AID-BIP4>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.He K, Ludtke SJ, Huang HW. Antimicrobial peptide pores in membranes detected by neutron in-plane scattering. Biochemistry. 1995;34:15614–15618. doi: 10.1021/bi00048a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.He K, Ludtke SJ, Worcester DL, Huang HW. Neutron scattering in the plane of membranes: Structure of alamethicin pores. Biophys. J. 1996;70:2659–2666. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(96)79835-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Allende D, Simon SA, McIntosh TJ. Melittin-induced bilayer leakage depends on lipid material properties: Evidence for toroidal pores. Biophys. J. 2005;88:1828–1837. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.049817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campagna S, Saint N, Molle G, Aumelas A. Structure and mechanism of action of the antimicrobial peptide piscidin. Biochemistry. 2007;46:1771–1778. doi: 10.1021/bi0620297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ludtke SJ, He K, Heller WT, Harroun TA, Yang L, Huang HW. Membrane pores induced by magainin. Biochemistry. 1996;35:13723–13728. doi: 10.1021/bi9620621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matsuzaki K, Murase O, Fujii N, Miyajima K. An antimicrobial peptide, magainin 2, induced rapid flip-flop of phospholipids coupled with pore formation and peptide translocation. Biochemistry. 1996;35:11361–11368. doi: 10.1021/bi960016v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang L, Harroun TA, Weiss TM, Ding L, Huang HW. Barrel-stave model or toroidal model? A case study on melittin pores. Biophys. J. 2001;81:1475–1485. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)75802-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Breed J, Biggin PC, Kerr ID, Smart OS, Sansom MSP. Alamethicin channel - modelling via restrained molecular dynamics simulations. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1997;1325:235–249. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(96)00262-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Breed J, Kerr ID, Molle G, Duclohier H, Sansom MSP. Ion channel stability and hydrogen bonding. Molecular modelling of channels formed by synthetic alamethicin analogues. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1997;1330:103–109. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(97)00163-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dittmer J, Thøgersen L, Underhaug J, Bertelsen K, Vosegaard T, Pedersen JM, Schiøtt B, Tajkhorshid E, Skrydstrup T, Nielsen NC. Incorporation of antimicrobial peptides into membranes: A combined liquid-state NMR and molecular dynamics study of alamethicin in DMPC/DHPC bicelles. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:6928–6937. doi: 10.1021/jp811494p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sansom MSP, Kerr ID, Mellor IR. Ion channels formed by amphipathic helical peptides. A molecular modelling study. Eur. Biophys. J. 1991;20:229–240. doi: 10.1007/BF00183460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tieleman DP, Berendsen HJC, Sansom MSP. An alamethicin channel in a lipid bilayer: Molecular dynamics simulations. Biophys. J. 1999;76:1757–1769. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(99)77337-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tieleman DP, Berendsen HJC, Sansom MSP. Voltage-dependent insertion of alamethicin at phospholipid/water and octane/water interfaces. Biophys. J. 2001;80:331–346. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(01)76018-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tieleman DP, Hess B, Sansom MSP. Analysis and evaluation of channel models: Simultions of alamethicin. Biophys. J. 2002;83:2393–2407. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3495(02)75253-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mottamal M, Lazaridis T. Voltage-dependent energetics of alamethicin monomers in the membrane. Biophys. Chem. 2006;122:50–57. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bachar M, Becker OM. Melittin at a membrane/water interface: Effects on water orientation and water penetration. J. Chem. Phys. 1999;111:8672–8685. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bernèche S, Nina M, Roux B. Molecular dynamics simulations of melittin in dimyristoylphosphatidylcholine bilayer membrane. Biophys. J. 1998;75:1603–1618. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77604-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lin J-H, Baumgaertner A. Stability of a melittin pore in a lipid bilayer: A molecular dynamics study. Biophys. J. 2000;78:1714–1724. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76723-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Leontiadou H, Mark AE, Marrink SJ. Antimicrobial peptides in action. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:12156–12161. doi: 10.1021/ja062927q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sengupta D, Leontiadou H, Mark AE, Marrink SJ. Toroidal pores formed by antimicrobial peptides show significant disorder. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2008;1778:2308–2317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thøgersen L, Schiøtt B, Vosegaard T, Nielsen NC, Tajkhorshid E. Peptide aggregation and pore formation in a lipid bilayer: A combined coarse-grained and all atom molecular dynamics study. Biophys. J. 2008;95:4337–4347. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.108.133330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Matsuzaki K, Yoneyama S, Miyajima K. Pore formation and translocation of melittin. Biochemistry. 1997;73:831–838. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78115-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mihajlovic M, Lazaridis T. Antimicrobial peptides in toroidal and cylindrical pores. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.04.004. submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fox RO, Jr, Richards FM. A voltage-gated ion channel model inferred from the crystal structure of alamethicin at 1.5-Å resolution. Nature. 1982;300:325–330. doi: 10.1038/300325a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terwilliger TC, Eisenberg D. The structure of melittin. I. Structure determination and partial refinement. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:6010–6015. doi: 10.2210/pdb1mlt/pdb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Terwilliger TC, Eisenberg D. The structure of melittin. II. Interpretation of the structure. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:6016–6022. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tachi T, Epand RF, Epand RM, Matsuzaki K. Position-dependent hydrophobicity of the antimicrobial magainin peptide affects the mode of peptide-lipid interactions and selective toxicity. Biochemistry. 2002;41:10723–10731. doi: 10.1021/bi0256983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lazaridis T. Effective energy function for proteins in lipid membranes. Proteins. 2003;52:176–192. doi: 10.1002/prot.10410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lazaridis T. Structural determinants of transmembrane beta-barrels. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 2005;1:716–722. doi: 10.1021/ct050055x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yang L, Weiss TM, Lehrer RI, Huang HW. Crystallization of antimicrobial pores in membranes: magainin and protegrin. Biophys. J. 2000;79:2002–2009. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76448-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Dathe M, Kaduk C, Tachikawa E, Melzig MF, Wenschuh H, Bienert M. Proline at position 14 of alamethicin is essential for hemolytic activity, catecholamine secretion from chromaffin cells and enhanced metabolic activity in endothelial cells. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1998;1370:175–183. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(97)00260-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Verkleij AJ, Zwaal RFA, Roelofsen B, Comfurius P, Kastelijn D, van Deenen LLM. The asymmetric distribution of phospholipids in the human red cell membrane. A combined study using phospholipases and freeze-etch electron microscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1973;323:178–193. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(73)90143-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Neria E, Fischer S, Karplus M. Simulation of activation free energies in molecular systems. J. Chem. Phys. 1996;105:1902–1921. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yang L, Weiss TM, Harroun TA, Heller WT, Huang HW. Supramolecular structures of peptide assemblies in membranes by neutron off-plane scattering: Method of analysis. Biophys. J. 1999;77:2648–2656. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)77099-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ladokhin AS, Selsted ME, White SH. Sizing membrane pores in lipid vesicles by leakage of co-encapsulated markers: pore formation by melittin. Biophys. J. 1997;72:1762–1766. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(97)78822-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dathe M, Schümann M, Wieprecht T, Winkler A, Beyermann M, Krause E, Matsuzaki K, Murase O, Bienert M. Peptide helicity and membrane surface charge modulate the balance of electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions with lipid bilayers and biological membranes. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12612–12622. doi: 10.1021/bi960835f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bechinger B. Structure and functions of channel-forming peptides: magainins cecropins, melittin and alamethicin. J. Membrane Biol. 1997;156:197–211. doi: 10.1007/s002329900201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lee S-A, Kim YK, Lim SS, Zhu WL, Ko H, Shin SY, Hahm K-S, Kim Y. Solution structure and cell selectivity of piscidin 1 and its analogues. Biochemistry. 2007;46:3653–3663. doi: 10.1021/bi062233u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gregory SM, Cavenaugh A, Journigan V, Pokorny A, Almeida PFF. A quantitative model for the all-or-none permeabilization of phospholipid vesicles by the antimicrobial peptide cecropin A. Biophys. J. 2008;94:1667–1680. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.118760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nishida M, Imura Y, Yamamoto M, Kobayashi S, Yano Y, Matsuzaki K. Interaction of a magainin-PGLa hybrid peptide with membranes: Insight into the mechanism of synergism. Biochemistry. 2007;46:14284–14290. doi: 10.1021/bi701850m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Huang HW. Elasticity of lipid bilayer interacting with amphiphilic helical peptides. J. Phys. II France. 1995;5:1427–1431. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang HW, Chen F-Y, Lee M-T. Molecular mechanism of peptide-induced pores in membranes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2004;92:198304. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.92.198304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fosnaric M, Kralj-Iglic V, Bohinc K, Iglic A, May S. Stabilization of pores in lipid bilayers by anisotropic inclusions. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2003;107:12519–12526. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kuhn-Nentwig L, Müller J, Schaller J, Walz A, Dathe M, Nentwig W. Cupiennin 1, a new family of highly basic antimicrobial peptides in the venom of the spider Cupiennius salei (Ctenidae) J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:11208–11216. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111099200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]