Abstract

Purpose:

Although elevated blood pressure (BP) predicts future cardiovascular events, recommended BP targets often is not reached in the general community. In a clinical real-life setting we evaluated BP impact and tolerability of the angiotensin-II receptor blocker telmisartan in patients with essential hypertension.

Patients and methods:

Patients in this observational study not at target BP started or switched to telmisartan monotherapy (40 or 80 mg) or a fixed-dose combination of telmisartan and hydrochlorothiazide (HCT) 80 mg/12.5 mg. Office and 24-hour ambulatory BP (AMBP) were measured before and after 8 weeks of treatment and physicians reported perceived drug efficacy and tolerability as “Very good”, “Good”, “Moderate” or “Bad”.

Results:

100 patients (34% female, 60 years, BMI 29.4 kg/m2, mean office BP 159/92 mmHg) of whom 38% were treatment naïve and 30%, 17%, 9% and 6% respectively were on 1, 2, 3 or 4 BP-lowering drugs, completed 8 weeks of treatment. The proportion of patients with office BP < 140/90 mmHg increased from 3% to 54% for systolic (P < 0.001), 38% to 75% for diastolic (P < 0.001), and 2% to 45% for systolic and diastolic BP (P < 0.001). A significant effect on BP levels was seen in patients being either treatment naïve or on 1 to 3 BP-lowering drugs at study entry, whereas no BP improvement occurred in those who switched from 4 drugs. Overall, mean 24-hour AMBP was reduced from 141/85 to 131/79 mmHg (P < 0.001). Drug efficacy and tolerability were perceived as “Very good” or “Good” by 44%/34% and 66%/27%, respectively. No drug discontinuations or serious adverse events were observed.

Conclusions:

In this observational study, telmisartan 40 to 80 mg, or the fixed-dose combination telmisartan 80 mg/HCT 12.5 mg, significantly increased the number of patients reaching target BP < 140/90 mmHg if treatment naïve or previously receiving 1 to 3 BP-lowering drugs. The BP reduction achieved was sustained for 24-hour and treatment tolerability was high.

Keywords: telmisartan, tolerability, efficacy, 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure, observational study

Background

Elevated blood pressure (BP) increases the risk for cardiovascular (CV) morbidity and mortality1–4 in a curvilinear relation, starting at 115/75 mmHg, irrespective of age and gender. The BP-related CV risk is accentuated in the presence of other CV risk factors or co-morbidities such as diabetes mellitus, obesity, metabolic syndrome and dyslipidemia.5

This is of concern as the prevalence of hypertension is high, eg, 28.4% in a survey among US residents from 2000,6 and on the rise; a significant 10% increase was seen in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) between 1988 and 2004.7 The cause for this development is multifactorial, eg, increasing prevalence of diabetes and obesity and increased life expectancy, which all are factors associated with increased cumulative lifetime risk for hypertension.5

Pharmacological BP-lowering contributes to CV disease prevention. Hence, several institutional bodies have issued BP treatment guidelines (eg, the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure [JNC-VII]),8 the American Heart Association9 and the European Societies of Hypertension and Cardiology.10 Most of these agree on a treatment goal of <140/90 mmHg in uncomplicated essential hypertension. However, despite such guidelines and the prevailing high number of anti-hypertensive agents,11 BP treatment goals are often not reached in hypertensive patients. It is believed that only approximately 25% to 40% of the treated subjects in the community are at target BP levels,12,13 which is in line with the NHANES examination 1999–2000 where only 31.0% of hypertensive patients were controlled to a BP of <140/90 mmHg.5 The cause for this may be both patient and physician related; eg, side effects or low efficacy of BP drugs, physicians resistance to supplement or dose escalate initiated treatment (as often ≥2 BP drugs are needed) and a low public awareness of CV benefits of BP control.3,14

In the present study, in a “real-world” setting of hypertensive patients in primary care not at target BP levels we wanted to evaluate BP responses (office- and 24-hour ambulatory-BP (AMBP) profiles), occurrence of side effects, and physician-perceived drug efficacy and tolerability of the oral angiotensin II receptor blocker, telmisartan (Micardis®; Boehringer Ingelheim Pharma, Germany). Telmisartan reduces BP by blocking vasoconstriction, sodium retention, and aldosterone and vasopressin production caused by angiotensin II.15

Methods

This was a prospective, nonrandomized, multicenter observational study (The Telmimore study [A clinical survey of the antihypertensive effects of telmisartan in patients with mild-to-moderate hypertension]) of patients recruited by 25 general practitioners (GPs) in the middle, western and south-eastern regions of Norway serving approximately 20000 to 25000 subjects. Patients with essential hypertension not at target BP, who were prescribed telmisartan by the physician on clinical indication, were eligible for inclusion. Informed written consent was obtained from all participants. The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and approved by the Regional Ethical Committee.

Patients were enrolled between June 2006 and June 2007, and remained under the care of the GPs for the duration of the study that was 8 weeks. At enrolment, a general clinical examination was performed and weight, height, data concerning past medical history (including coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and cerebrovascular disease), and current medication were recorded in a case report form (CRF). Office BP was measured on the non-dominant arm with a random zero mercury sphygmomanometer using appropriate cuff size in sitting position after 5 minutes of rest. A mean of two measurements was recorded. 24-hour AMBP measurements were performed, utilizing an oscillometric equipment, on the nondominant arm using appropriate cuff size (Welch Allyn AMBP 6100, Skaneateles Falls, NY, USA), starting between 10:00 am and 12:00 am. Reading intervals were 15 minutes from 07:00 am to 11:00 pm and 30 minutes from 11:00 pm to 07:00 am. 24-hour AMBP means were computed with weights according to the time interval between successive readings. Recordings with more than 80% of valid measurements and which had at least one reading per time-period during night-time and early morning hours were considered valid.16

At study entry, patients not at target BP either started (if treatment naïve), or were switched to (if already on BP-lowering drugs) treatment with telmisartan 40 mg, 80 mg, or a fixed-dose combination of telmisartan 80 mg/hydrochlorothiazide (HCT) 12.5 mg. The BP effect was evaluated after 8 weeks. At this final visit the same data as on study entry were recorded together with a questionnaire for the GPs to be filled in concerning perceived drug efficacy and tolerability. Answer options on the questionnaire were divided in “Very good”, “Good”, “Moderate”, “Bad” or “Not determined”. Possible adverse events during the study were detailed in the CRF.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS statistical software version 16.0 for Windows (SPSS Inc. Chicago, USA). Data on continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation unless otherwise stated. Analysis of continuous variables was performed by paired t-test or a bivariate correlation where appropriate. Categorical variables are presented as counts or proportions (%) and by statistical comparisons of these parameters the chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test were utilized. Sample size was determined based on estimated improvements in proportion of subjects at treatment goal from 30% to 45%. The null hypothesis was based on no difference in this proportion. A total number of 86 participants needed was estimated from a statistical power of 90% and an alpha error level of 5%. A two-sided P-value of < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

A total of 103 Caucasian patients was enrolled in the study. Three patients were lost to 8 weeks follow-up, thus 100 patients were eligible for statistical analyses. Of these, 38 patients (38%) were treatment naïve. Baseline characteristics of the study cohort are given in Table 1. The BP was high (mean systolic BP 159 ± 13 and mean diastolic BP 92 ± 10 mmHg) irrespective of medical treatment. Mean BMI was high, adjunctive treatment with statins was relatively low despite substantial co-morbidity, and few patients were on treatment with betablockers. Telmisartan monotherapy 40 to 80 mg (mean dosage 52 mg) was given to 49 patients (49%) and the fixed-dose telmisartan 80 mg/HCT 12.5 mg to 51 patients (51%).

Table 1.

Baseline data for 100 hypertensive patients completing 8 weeks of treatment with telmisartan with or without HCT

| Total cohort | Treatment-naïve | 1 BP drug | 2 BP drugs | 3 BP drugs | 4 BP drugs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 100 | 38 | 30 | 17 | 9 | 6 |

| Age (years) | 60 ± 13 | 54 ± 12 | 63 ± 14 | 64 ± 12 | 65 ± 9 | 62 ± 6 |

| Gender (female/male) | 34/66 | 16/32 | 12/18 | 5/12 | 1/8 | 0/6 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 29.4 ± 4.7 | 30.4 ± 5.7 | 28.4 ± 3.9 | 28.0 ± 4.5 | 29.8 ± 2.7 | 30.7 ± 4.2 |

| Duration of hypertension | ||||||

| <1 year | 39 (39%) | 29 (76%) | 10 (33%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| 1–5 years | 24 (24%) | 6 (16%) | 12 (40%) | 5 (29%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (17%) |

| >5 years | 37 (37%) | 3 (8%) | 8 (27%) | 12 (71%) | 9 (100%) | 5 (83%) |

| Concomitant disease | ||||||

| Coronary heart disease | 11 (11%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (7%) | 3 (18%) | 4 (44%) | 2 (33%) |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 5 (5%) | 1 (4%) | 3 (10%) | 1 (6%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 5 (5%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (7%) | 2 (12%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (17%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 10 (10%) | 6 (16%) | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (33%) |

| COPD | 6 (6%) | 3 (8%) | 3 (10%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Dyslipidemiaa | 26 (26%) | 5 (13%) | 6 (20%) | 4 (24%) | 7 (78%) | 4 (67%) |

| Previous treatment and BP related parameters | ||||||

| Beta-blockers | 15 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 2 | 6 (35%) | 3 (33%) | 4 (67%) |

| Diuretics | 32 (32%) | 0 (0%) | 13 | 7 (41%) | 8 (89%) | 4 (67%) |

| ARB | 29 (29%) | 0 (0%) | 9 | 8 (48%) | 7 (78%) | 5 (83%) |

| ACE inhibitor | 8 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 2 | 4 (24%) | 2 (22%) | 0 (0%) |

| CCB | 18 (18%) | 0 (0%) | 3 | 4 (24%) | 6 (67%) | 5 (83%) |

| Other | 13 (13%) | 0 (0%) | 1 | 5 (29%) | 1 (11%) | 6 (100%) |

| Sys BP (mmHg) | 159 ± 13 | 160 ± 12 | 155 ± 13 | 163 ± 11 | 156 ± 11 | 162 ± 19 |

| Dia BP (mmHg) | 92 ± 10 | 97 ± 9 | 91 ± 9 | 86 ± 9 | 88 ± 11 | 90 ± 6 |

| HR (bpm) | 74 ± 10 | 76 ± 10 | 71 ± 12 | 70 ± 8 | 77 ± 9 | 79 ± 7 |

On statin therapy.

Notes: Data are given as mean ± SD (continuous variables) and as counts (n) or % (categorical variables).

Abbreviations: HCT, hydrochlorothiazide; BP, blood pressure; BMI, body mass index; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blocker; ACE, angiotensin converting enzyme; CCB, calcium channel blocker; sys, systolic; dia, diastolic; HR, heart rate; bpm, beats per minute.

Effects on office BP

Telmisartan treatment for 8 weeks was associated with a statistically significant reduction in systolic and diastolic BP, both in treatment naïve patients (BP difference −24/−14 mmHg, P < 0.001 for both) and in patients on 1, 2, or 3 BP-lowering drugs at study entry (BP difference −7/−9 mmHg, [P < 0.001 for both], −26/−7 mmHg [P < 0.001 for both], and −10/−4 mmHg [P < 0.01 for systolic BP only] respectively) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Impact on office BP 8 weeks after initiating or switching to telmisartan with or without HCT (any regimen) according to baseline number of BP-lowering drugs

| Total cohort | Treatment-naïve | 1 BP drug | 2 BP drugs | 3 BP drugs | 4 BP drugs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 100 | 38 | 30 | 17 | 9 | 6 |

| Baseline sys BP (mmHg) | 159 ± 13 | 161 ± 13 | 155 ± 13 | 163 ± 11 | 156 ± 11 | 162 ± 19 |

| Study end sys BP (mmHg) | 139 ± 14 | 137 ± 15 | 138 ± 14 | 137 ± 11 | 146 ± 13 | 153 ± 11 |

| Δ sys BP (mmHg) | − 20 ± 16*** | − 24 ± 18*** | − 17 ± 16*** | − 26 ± 13*** | − 10 ± 9** | − 9 ± 12 |

| Baseline dia BP (mmHg) | 92 ± 10 | 97 ± 9 | 91 ± 9 | 86 ± 9 | 88 ± 11 | 90 ± 6 |

| Study end dia BP (mmHg) | 82 ± 9 | 83 ± 9 | 81 ± 7 | 79 ± 7 | 77 ± 9 | 91 ± 11 |

| Δ dia BP (mmHg) | −10 ± 10*** | − 14 ± 10*** | − 9 ± 10*** | −7 ± 7*** | − 4 ± 7 | 2 ± 4 |

| Baseline HR (bpm) | 74 ± 10 | 76 ± 10 | 71 ± 12 | 70 ± 8 | 77 ± 9 | 79 ± 7 |

| Study end HR (bpm) | 70 ± 12 | 71 ± 9 | 69 ± 11 | 70 ± 8 | 79 ± 10 | 63 ± 28 |

| Δ HR (bpm) | −3 ± 12** | − 5 ± 11** | − 2 ± 14 | 0 ± 10 | 2 ± 8 | − 16 ± 33 |

Notes: Data are given as mean ±SD.

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001.

Abbreviations: HCT, hydrochlorothiazide; sys, systolic; BP, blood pressure; dia, diastolic; Δ, delta (ie, BP change from baseline to study end); HR, heart rate; bpm, beats per minute.

The BP reduction (both systolic and diastolic) for the whole cohort tended to be more pronounced in patients given the fixed-dose telmisartan 80 mg/HCT 12.5 mg than in those receiving telmisartan monotherapy if previously treated with BP-lowering drugs (Table 3). No statistically significant difference in BP was seen in the six patients switching from a previous combination therapy of 4 BP-lowering drugs to a telmisartan based regimen (Table 3).

Table 3.

Effect of telmisartan therapy on office BP at 8 weeks according to baseline number of BP-lowering drugs

|

Telmisartan 40 mg |

Telmisartan 80 mg |

Telmisartan 80 mg/HCT 12.5 mg |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Δ sys BP (mmHg) | Δ dia BP (mmHg) | n | Δ sys BP (mmHg) | Δ dia BP (mmHg) | n | Δ sys BP (mmHg) | Δ dia BP (mmHg) | |

| Total cohort | 28 | −18 ± 17*** | − 9 ± 11*** | 21 | − 18 ± 20*** | −10 ± 11*** | 51 | − 22 ± 14*** | − 9 ± 10*** |

| Treatment-naïve | 19 | −18 ± 18*** | − 11 ± 10*** | 6 | − 28 ± 24* | − 19 ± 15* | 13 | − 30 ± 12*** | −15 ± 8*** |

| 1 BP drug | 5 | −14 ± 16 | − 5 ± 10 | 10 | − 9 ± 13 | − 7 ± 7* | 15 | − 23 ± 15*** | −13 ± 11*** |

| 2 BP drugs | 3 | −30 ± 9* | − 10 ± 13 | 4 | − 29 ± 23 | − 8 ± 6 | 10 | − 23 ± 10*** | − 7 ± 5** |

| 3 BP drugs | 1 | − 2 | 6 | 1 | − 10 | 1 | 7 | − 12 ± 10* | − 6 ± 6* |

| 4 BP drugs | 0 | N/A | N/A | 0 | N/A | N/A | 6 | − 9 ± 12 | 2 ± 9 |

Notes: Data are given as mean ±SD and as counts (n).

P < 0.05,

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001.

Abbreviations: HCT, hydrochlorothiazide; Δ, delta; sys, systolic; dia, diastolic; BP, blood pressure; N/A, not applicable.

The proportion of patients at target BP levels of <140/90 mmHg increased from 2% at study entry to 45% after 8 weeks of telmisartan treatment, and did not differ between the three telmisartan regimens (40 mg: 46%, 80 mg: 43%, 80 mg/HCT 12.5 mg: 43%) (Table 4). The corresponding increase in the proportion reaching systolic BP target only was 3% to 54%, and diastolic BP target only 38% to 75% (P < 0.001 for all comparisons) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Percentages of patients within target office BP(<140/90 mmHg) at baseline and study end (after 8 weeks of telmisartan with or without HCT) according to BP therapy at study entry

| Total cohort | Treatment naïve | 1 BP drug | 2 BP drugs | 3 BP drugs | 4 BP drugs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 100 | 38 | 30 | 17 | 9 | 6 |

| Baseline sys BP < 140 mmHg | 3% | 0% | 7% | 0% | 0% | 17% |

| 8 weeks sys BP < 140 mmHg | 54%*** | 61%*** | 57%*** | 59%** | 33%§ | 0% |

| Baseline dia BP < 90 mmHg | 38% | 18% | 40% | 65% | 56% | 50% |

| 8 weeks dia BP < 90 mmHg | 75%*** | 76%*** | 80%** | 88% | 67% | 33% |

| Baseline sys/dia BP <140/90 mmHg | 2% | 0% | 3% | 0% | 0% | 17% |

| 8 weeks sys/dia BP <140/90 mmHg | 45%*** | 50%*** | 47%** | 53%*** | 33%§ | 0% |

P < 0.01,

P < 0.001;

P = 0.059.

Abbreviations: BP, blood pressure; HCT, hydrochlorothiazide.

Effects on 24-hour AMBP

In total, 75 patients (75%) agreed to have 24-hour AMBP measurements performed. The baseline characteristics of these did not differ significantly from those of the total cohort. Data were lacking for 5 patients at baseline and for 1 patient at follow-up. Thus, 24-hour AMBP recordings were available for statistical analyses in 69 patients.

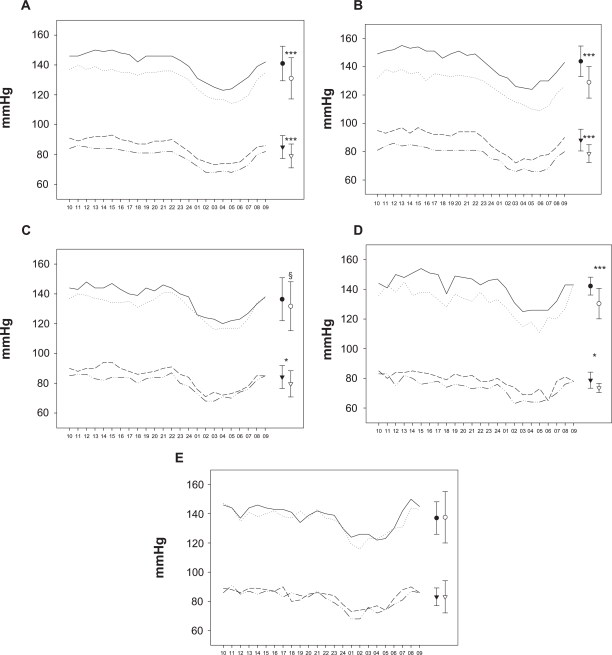

Telmisartan treatment for 8 weeks was associated with a statistically significant reduction in mean 24-hour AMBP in the whole study cohort (mean systolic/diastolic BP baseline: 141/85 mmHg; at 8 weeks: 131/79 mmHg, P < 0.001 for both, Figure 1a). Furthermore, in treatment naïve patients (Figure 1b), as well as in those on 2 BP-lowering drugs at study entry (Figure 1d), a significant reduction for both 24-hour mean systolic and diastolic BP was observed, whereas in patients switching from 1 study drug to telmisartan a significant reduction was seen only for the mean 24-hour diastolic BP (Figure 1c), with a trend for systolic BP reduction (P = 0.085). There was a positive correlation between 8-week changes in systolic office and mean 24-hour AMBP (r = 0.54, P < 0.001, n = 69). No impact was seen on mean 24-hour heart rate (baseline 73.6 ± 12.2 vs 74.1 ± 12.1 at 8 weeks).

Figure 1.

24-hour ambulatory BP incl. mean ± SD at baseline and study end in A) total cohort (n = 69); and according to number of BP-lowering drugs at baseline: B) none (n= 31), C) 1 (n = 17), D) 2 (n = 9) and E) 3 or 4 (n = 12) drugs.

Notes: — Baseline hourly sys BP, ... 8-weeks hourly sys BP, --- Baseline hourly dia BP, -..- 8-weeks hourly dia BP, • Baseline 24-hour sys BP, ○ 8-weeks 24-hour sys BP, ▾ Baseline 24-hour dia BP, ▿ 8-weeks 24-hour dia BP, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, §P = 0.085.

Abbreviations: sys, systolic; BP, blood pressure; dia, diastolic.

Tolerability and safety

Telmisartan was classified as being efficacious and well tolerated by most GPs (“Very good”: 44% and 66%, and “Good”: 34% and 27%, respectively) (Table 5). Serious adverse events did not occur and no patients discontinued the treatment. Adverse events occurred in 9 cases: bronchitis, enteritis, arthralgia, rhinitis, mouth dryness, hypotension, lethargy, pollakissuria, and tiredness, of which the latter 5 were assumed by the GPs as potentially being drug related.

Table 5.

Eight-week incidence of adverse events and prescribing physician’s subjective evaluation of efficacy and tolerability according to telmisartan treatment regimen

| Total cohort | 40 mg telmisartan | 80 mg telmisartan | 80 mg telmisartan/2.5 mg HCT | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 100 | 28 | 21 | 51 |

| Adverse events | ||||

| Serious AE | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Minor AE | 9 (9%) | 7 (25%) | 0 (0%) | 2 (4%) |

| Treatment efficacy as judged by the prescribing physician | ||||

| Very good | 44 (44%) | 11 (39%) | 9 (43%) | 24 (47%) |

| Good | 34 (34%) | 12 (43%) | 8 (38%) | 14 (27%) |

| Moderate | 13 (13%) | 1 (3%) | 3 (14%) | 9 (18%) |

| Bad | 5 (5%) | 1 (3%) | 1 (5%) | 3 (6%) |

| Not determined | 4 (4%) | 3 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) |

| Treatment tolerability as judged by the prescribing physician | ||||

| Very good | 66 (66%) | 18 (64%) | 13 (62%) | 35 (69%) |

| Good | 27 (27%) | 5 (18%) | 8 (38%) | 14 (27%) |

| Moderate | 4 (4%) | 3 (8%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) |

| Bad | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Not determined | 3 (3%) | 2 (7%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (2%) |

Abbreviations: AE, adverse events; HCT, hydrochlorthiazid.

Discussion

Starting telmisartan (either monotherapy in a dosage of 40 to 80 mg, or a fixed-dose of telmisartan 80 mg/HCT 12.5 mg) did significantly improve BP in patients both previously treatment naïve and in those on treatment with 1, 2 or 3 BP-lowering drugs. This indicates that telmisartan, with or without HCT, has a potent BP-lowering effect that can be useful in a substantial number of patients with arterial hypertension.

The treatment response in the current study is concordant with results from other series exploring the effect of telmisartan in a community setting.17,18 This applies also to the high tolerability and low incidence of side effects seen in our study. The observed inverse relation between treatment effect and number of previous BP drugs used is not surprising, as many patients with BP polypharmacy in fact do have a refractory hypertension which also could apply to telmisartan.

As anticipated, the proportion of patients treated to target at study entry was low (2%), however a substantial number had had their disease for many years (37% >5 years, 24% 1 to 5 years) and 62% were receiving 1 to 4 BP-lowering drugs. Although the observed treatment effects of switching to telmisartan, with or without HCT, for those already on 1 to 3 BP-lowering drugs in most cases were reassuring, a substantial number of patients (55%) still was not at target after 8 weeks. Generic limitations of observational studies such as a relatively short treatment period and lack of a predefined treatment algorithm including provision of guidelines for dose escalation may have contributed to this. However, clinical experience indicates that target values for BP may be difficult to reach for a substantial number of patients also in the “real world”.12,13

24-hour AMBP measurements as a means for more optimal BP control are probably underused in clinical practice. In the current study we found it feasible to apply this method in a GP setting, and other trials have shown an educational value of this procedure even for the patient.19 Furthermore, 24-hour AMBP, and especially 24-hour systolic BP, has been shown to have prognostic information above and beyond that of office BP.20 Thus, a more liberal use of this method in primary care should be advocated.21

The observed underuse of statins is in accordance with several surveys indicating that in the general community probably as much as 75% of patients are not treated according to clinical guidelines.12

Limitations of the study, apart for generic limitations with any observational study, include the question whether the cohort is representative of the general hypertensive population. The baseline characteristics including co-morbidity indicate that this is true. Another limitation is that we can not rule out whether similar results could have been obtained by conducting this study with another design or by dose escalating the current used drugs or by add-on of other drugs, since we have no control group; we also did not assess treatment response based on what type of BP-lowering drug(s) were used (eg, calcium channel blockers, angiotensin receptor blockers, angiotensin conververting enzyme inhibtors) prior to the switch. Other limiting factors include the relatively small sample size, although this was fairly large for a 24-hour AMBP study. Further, an aspect that could limit the treatment response is that among included subjects, some were already at or near BP treatment targets at study entry. On the other hand, this “underevaluation” probably are balanced with the phenomenona of the open nature of the study, which was unavoidable, that could potentially lead to an impact on patients’ motivation to “do well” (the Hawthorne effect), thereby overestimating the treatment effect.

In conclusion, in this observational study, 8 weeks treatment with telmisartan 40 to 80 mg or the fixed-dose combination telmisartan 80 mg/HCT 12.5 mg significantly reduced BP in patients with hypertension being either treatment naïve or switching from 1 to 3 other BP-lowering drugs. The proportion of patients reaching target BP < 140/90 mmHg was also significantly increased with telmisartan, with or without HCT, therapy. BP-lowering effects were sustained for 24 hours and treatment tolerability was high.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr Merete Dahl, Ms Anne-Lise Evensen, Ms Mona Irene Andersen and Mr Jorge Lizano for their contribution in data collection and management, and the study patients for participation.

Footnotes

TELMIMORE study investigators

Bakken J, Baloch SM, Berz A, Blatter-Krog Strømme M, Bye A, D’Angelo GE, Folven A, Gorski Z, Humborstad BJ, Karsten DO, Langaker KE, Landmark NE, Leraand N, Lunde S, Nicolaisen B, Onsum H, Parvaiz R, Risanger T, Råheim GA, Storvand E, Ulvan M, Walaas K, Wear-Hansen HG, Wessel-Aas T, Aaserud E.

Disclosures

F Kontny: Advisory Board fees from AstraZeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim. Consulting fees from Astra-Zeneca, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Sanofi-Aventis. Grant support from Merck Sharp and Dohme, Perseus Proteomics Inc. Lecture fees from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Eli-Lilly, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis.

T Risanger: Study investigator fees from Boehringer Ingelheim.

A Bye: Advisory Board fees from Astra-Zeneca. Study investigator fees from Merck Sharp and Dohme, Glaxo-Smith Kline and Boehringer Ingelheim.

Ø Arnesen: Employee of Boehringer Ingelheim Norway KS.

OE Johansen: Employee of Boehringer Ingelheim Norway KS and associated post-doctoral researcher at Medical department, Vestre Viken, Asker and Baerum Hospital, Norway.

This study was funded by Boehringer Ingelheim Norway KS. The study sponsor was responsible for the data collection and analyses. All data were made available to the writing committee (FK, TR, AB, ØA, OEJ) that in collaboration developed the manuscript and jointly agreed to submit it for publication.

References

- 1.Selmer R. Blood pressure and twenty-year mortality in the City of Bergen, Norway. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:428–440. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Age-specific relevance of usual blood pressure to vascular mortality: a meta-analysis of individual data for one million adults in 61 prospective studies. Lancet. 2002;360:1903–1913. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(02)11911-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang TJ, Vasan RS. Epidemiology of uncontrolled hypertension in the United States. Circulation. 2005;112:1651–1662. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.490599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peterson JC, Adler S, Burkart JM, et al. Blood pressure control, proteinuria, and the progression of renal disease: The Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study. Ann Intern Med. 1995;123:754–762. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-123-10-199511150-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hajjar I, Kotchen TA. Trends in prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control of hypertension in the United States, 1988–2000. JAMA. 2003;290:199–206. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.2.199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fields LE, Burt VL, Cutler JA, et al. The burden of adult hypertension in the United States 1999 to 2000: A rising tide. Hypertension. 2004;44:398–404. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000142248.54761.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ostchega Y, Dillon CF, Hughes JP, et al. Trends in hypertension prevalence, awareness, treatment, and control in Older US Adults: Data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1988 to 2004. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55:1056–1065. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01215.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42:1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rosendorff C, Black HR, Cannon CP, et al. Treatment of hypertension in the prevention and management of ischemic heart disease: a scientific statement From the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research and the Councils on Clinical Cardiology and Epidemiology and Prevention. Circulation. 2007;115:2761–2788. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.183885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Task FM, Mancia G, De Backer G, et al. 2007 Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the Management of Arterial Hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension (ESH) and of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2007;28:1462–1536. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Psaty BM, Lumley T, Furberg CD, et al. Health outcomes associated with various antihypertensive therapies used as first-line agents: a network meta-analysis. JAMA. 2003;289:2534–2544. doi: 10.1001/jama.289.19.2534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Geller JC, Cassens S, Brosz M, et al. Achievement of guideline-defined treatment goals in primary care: the German Coronary Risk Management (CoRiMa) study. Eur Heart J. 2007;28:3051–3058. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nieto FJ, Alonso J, Chambless LE, et al. Population awareness and control of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities study. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:677–684. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka T, Okamura T, Yamagata Z, et al. Awareness and treatment of hypertension and hypercholesterolemia in Japanese Workers: The High-Risk and Population Strategy for Occupational Health Promotion (HIPOP-OHP) Study. Hypertens Res. 2007;30:921–928. doi: 10.1291/hypres.30.921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharpe M, Jarvis B, Goa KL. Telmisartan: a review of its use in hypertension. Drugs. 2001;61:1501–1529. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200161100-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O’Brien E, Asmar R, Beilin L, et al. European Society of Hypertension recommendations for conventional, ambulatory and home blood pressure measurement. J Hypertens. 2003;21:821–848. doi: 10.1097/00004872-200305000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michel MC, Bohner H, Köster J, et al. U. Safety of telmisartan in patients with arterial hypertension : an open-label observational study. Drug Saf. 2004;27:335–344. doi: 10.2165/00002018-200427050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.White WB, Weber MA, Davidai G, et al. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring in the primary care setting: assessment of therapy on the circadian variation of blood pressure from the MICCAT-2 Trial. Blood Press Monit. 2005;10:157–163. doi: 10.1097/00126097-200506000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mallion JM, de Gaudemaris R, Baguet JP, et al. Acceptability and tolerance of ambulatory blood pressure measurement in the hypertensive patient. Blood Press Monit. 1996;1:197–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Conen D, Bamberg F. Noninvasive 24-h ambulatory blood pressure and cardiovascular disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2008;26:1290–1299. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e3282f97854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Verdecchia P, Angeli F, Mazzotta G, et al. G. Home blood pressure measurements will not replace 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. Hypertension. 2009;54:188–195. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.122861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]