Abstract

Homohexameric ring AAA+ ATPases are found in all kingdoms of life and are involved in all cellular processes. To accommodate the large spectrum of substrates, the conserved AAA+ core has become specialized through the insertion of specific substrate-binding motifs. Given their critical roles in cellular function, understanding the nucleotide-driven mechanisms of action is of wide importance. For one type of member AAA+ protein (phage shock protein F, PspF), we identified and established the functional significance of strategically placed arginine and glutamate residues that form interacting pairs in response to nucleotide binding. We show that these interactions are critical for “cis” and “trans” subunit communication, which support coordination between subunits for nucleotide-dependent substrate remodeling. Using an allele-specific suppression approach for ATPase and substrate remodeling, we demonstrate that the targeted residues directly interact and are unlikely to make any other pairwise critical interactions. We then propose a mechanistic rationale by which the nucleotide-bound state of adjacent subunits can be sensed without direct involvement of R-finger residues. As the structural AAA+ core is conserved, we propose that the functional networks established here could serve as a template to identify similar residue pairs in other AAA+ proteins.

Keywords: ATPases, Bacterial Transcription, Protein Motifs, Protein/Protein Interactions, Transcription Enhancers, AAA+ ATPase, PspF, Protein Interface, Residue Swapping, Subunit Communication

Introduction

Hexameric AAA+ ATPases (ATPases associated with various cellular activities) are involved in multiple cellular processes and are present in all kingdoms of life. Mutations in these proteins have been reported in several human diseases, including fronto-temporal dementia with inclusion body myopathy and Paget disease of bone, hereditary spastic paraparesis, dystonia, and prostate cancer (1–8). However, the underlying mechanisms by which these mutations affect the AAA+ ATPase (resulting in these diseases) are largely unknown, reducing drastically the possibility of treatment. Understanding the conserved mechanism by which AAA+ ATPases achieve their functionality is then of prime importance in the search for therapeutics.

AAA+ ATPase molecular machines require nucleotide hydrolysis to remodel their substrate. They share a structural core (containing Walker A and B motifs, the sensor I sequence and the second region of homology) usually made more elaborate by inserted motif(s) (defining them as subclade) to establish the specialized functionality needed for substrate interaction specificity (reviewed in Refs. 9–11). Some AAA+ ATPases have evolved complexity through formation of heteromeric assemblies (e.g. m-AAA protease Yta10–12 or AAA helicase MCM2–7), strongly suggesting differential contributions of subunits to hexamer activity (12–15).

Sensing the adjacent subunit functional state is expected to be critical for hexameric ring activity. Conserved arginine residues, so-called arginine finger residues (R-finger), have been shown to play a crucial role in the hexameric ring ATPase activity by acting in trans, stabilizing the nucleotide in the adjacent nucleotide binding pocket (16–18). Nevertheless, the mechanism(s) allowing coordination between subunits remains poorly understood. We speculate that other residues sensitive to the nucleotide-bound state will support the coordinated conformational changes. Defining the functional networks between residues of the common structural AAA+ core is crucial to fully understand how these molecular machines work.

Studying the molecular communication pathway operating between the different subunits of the AAA+ oligomeric ring requires use of an established tractable system. Here, we used the AAA+ domain of PspF (PspF1–275), a bacterial enhancer binding protein involved in bacterial pathogenicity (19) and an archetypal member of subclade 6 of the AAA+ protein family (which includes HslU, ClpX, MCM, RuvB, and Ltag) as a model of the conserved AAA+ core (9, 20). Extensive studies using PspF as an σ54-transcriptional activator, functionally analogous to eukaryotic RNA polymerase II TFIIH ATPase (21, 22), allow us to use a range of assays to measure the different activities needed for full AAA+ ring functionality, including the following: (i) its homo-oligomerization, (ii) substrate interaction, and (iii) nucleotide hydrolysis-dependent substrate remodeling.

In PspF the conserved AAA+ core is refined by two inserted structural motifs: loop 1 (L1, inserted in α-helix 3) and loop 2 (L2 or presensor I, inserted in α-helix 4). L1 presents the substrate-interacting “GAFTGA motif,” allowing docking of σ54 (the substrate), and L2 is proposed to coordinate L1 in a nucleotide-dependent manner (23–27).

Previous studies with clade 6 AAA+ ATPases, including MCM, ClpX, and PspF, indicated that functional cross-talk operates between the subunits of the hexamer (25, 28–33). Indeed, the mixed nucleotide occupancy and stimulation of ATPase activity by ADP described for PspF suggested that communication and coordination between subunits were required for optimal activity (33). In addition, structural studies showed that all six of the substrate-interacting motifs (L1) do not contact σ54 (the target) at the same time, further inferring coordination between subunits (25, 34).

Here, we provide functional evidence for new communication networks used to establish substrate binding and remodeling activities, suggesting how subunits communicate the local effects of nucleotide binding and hydrolysis to support coordination of subunit activities in the hexamer.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids

Plasmid pPB1 encodes the AAA+ domain of Escherichia coli PspF, called PspF1–275, with an amino-terminal His6 tag in pET28b+ (23). Variants of PspF1–275 were generated from plasmid pPB1 mutagenized to yield variants as pNJs (supplemental Table 1S). pNJ37 was constructed by subcloning the NdeI/HindIII Klebsiella pneumoniae rpoN containing fragment from pET28 construct to pET33b cut with NdeI/HindIII. Constructs were verified by DNA sequencing.

Protein Purification

PspF1–275 proteins were purified as described previously (33) and stored at −80 °C in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mm NaCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT,3 and 5% glycerol. σ54 and 32P-end-labeling heart muscle kinase-σ54 was purified and labeled as described previously (35, 36) and stored at −80 °C in 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 200 mm NaCl, 0.1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, and 50% glycerol. E. coli core RNA polymerase enzyme was purchased from Cambio. Protein concentration was estimated using the Lowry method (37).

ATPase Activity

The ATPase activity assays were performed in buffer containing final concentrations of 35 mm Tris acetate, pH 8.0, 70 mm potassium acetate, 15 mm magnesium acetate, 19 mm ammonium acetate, 0.7 mm DTT, and 3 μm PspF1–275. The mixture was preincubated at 37 °C for 10 min, and the reaction was started by adding 3 μl of an ATP solution containing 0.6 μCi/μl [α-32P]ATP (3000 Ci/mmol) plus 3.33 mm ATP and incubated for varying times at 37 °C. Reactions were quenched by addition of 5 volumes of 2 m formic acid. The [α-32P]ADP was separated from [α-32P]ATP by thin layer chromatography, and radiolabeled ADP and ATP were measured by PhosphorImager (Fuji Bas-1500) and analyzed using Aida software. Activity is expressed as a percentage of PspF1–275WT turnover value. All experiments were performed at least in triplicate, and fluctuations of turnover values were maximally 10%.

Native Gel Mobility Shift Assays

Gel mobility shift assays were conducted to detect protein-protein complexes. Assays were performed in a 10-μl final volume containing 10 mm Tris acetate, pH 8.0, 50 mm potassium acetate, 8 mm magnesium acetate, 0.1 mm DTT, 4 mm ADP, ± NaF (5 mm), ± 32P-heart muscle kinase-σ54 (1 μm). Where required, PspF1–275 WT or variant (5 μm) ± AlCl3 (0.4 mm) was added for a further 20 min at 37 °C. Complexes were analyzed on a native 4.5% polyacrylamide gel. Radiolabeled heart muscle kinase-σ54 was measured by PhosphorImager (Fuji Bas-1500) and analyzed using Aida software.

In Vitro Open Complex and Abortive Initiation Assay

Open complex formation assays were performed in a 10-μl volume containing 10 mm Tris acetate, pH 8.0, 50 mm potassium acetate, 8 mm magnesium acetate, 0.1 mm DTT, 4 mm dATP, 0.1 μm core RNA polymerase enzyme, 0.4 μm σ54, and 20 nm promoter DNA. The mixture was preincubated at 37 °C for 5 min, and the reaction was started by addition of 5 μm of PspF1–275 WT or variants and incubated for 5 min at 37 °C. Open complex formation was monitored following the synthesis of the short transcript (−1UpGGG+3) started by simultaneous addition of heparin (100 μg/ml), initiating dinucleotide UpG (0.5 mm), GTP (0.01 mm), and 4 μCi of [α-32P]GTP for a further 10 min. The reaction was quenched by addition of loading buffer and analyzed on a 20% denaturating gel. Radiolabeled RNA products were measured by PhosphorImager (Fuji Bas1500) and analyzed using Aida software.

In Vitro Full-length Transcription Assays

Full-length or abortive transcription assays were performed in a 10-μl volume containing 10 mm Tris acetate, pH 8.0, 50 mm potassium acetate, 8 mm magnesium acetate, 0.1 mm DTT, 4 mm dATP, 0.1 μm core RNA polymerase enzyme, 0.4 μm σ54, and 20 nm promoter DNA. The mixture was preincubated at 37 °C for 5 min, and the reaction was started by addition of 5 μm of PspF1–275 WT or variants and incubated for varying times at 37 °C. Full-length transcription (from the supercoiled Sinorhizobium meliloti nifH promoter) was initiated by adding a mixture containing 100 μg/ml heparin, 1 mm ATP, CTP, GTP, 0.5 mm UTP, and 3 μCi of [α-32P]UTP for a further 10 min. The reaction was stopped by addition of loading buffer and analyzed on 6% sequencing gels. Radiolabeled RNA products were measured by PhosphorImager (Fuji Bas-1500) and analyzed using Aida software.

Gel Filtration through Superdex 200

PspF1–275 WT and variants (at different concentrations) were incubated for 5 min at 4 °C in buffer containing 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mm NaCl, and 15 mm MgCl2 ± 0.5 mm ATP where indicated. 50-μl samples were then injected onto a Superdex 200 column (10 × 300 mm, 24 ml) (GE Healthcare) and equilibrated with the sample buffer ± nucleotide. Chromatography was performed at 4 °C at a flow rate of 0.5 ml/min, and columns were calibrated with globular proteins as follows: thyroglobulin (669 kDa), apoferritin (443 kDa), β-amylase (200 kDa), bovine serum albumin (66 kDa), and carbonic anhydrase (29 kDa). All experiments were repeated at least twice, and the elution profiles obtained were similar. Proteins were detected at a 280-nm wavelength.

RESULTS

Structural data from PspF, NtrC, RuvB, and Ltag in the presence of different bound nucleotides suggest that the side chains of several strategically placed and physically paired residues could move in a nucleotide-dependent manner (Fig. 1). The PspF “dimer” presented in Fig. 1 has some uncertainties as follows: (i) the crystal structure of PspF1–275 only defines a PspF1–275 monomer, and the interface structure of the dimer is therefore modeled; and (ii) the nucleotide-bound form of the monomeric structure was obtained by soaking the preformed apo-crystal with nucleotide, so movements observed for the residue side chains could be restricted due to crystal packing constraints. The structural model of the PspF dimer interface requires experimental validation. Based on this model, we identified two putative “networks” that might allow the coupling of the nucleotide-bound state to functional activities in the PspF hexamer, probably via the formation of differential salt bridges between compatible pair residues. The first network includes residues located in the same subunit as follows: Glu81, Arg91, Glu97, and Arg131, potentially associated with coordination between L1 and L2 in response to the nucleotide bound in the subunit (Fig. 1, A and B). The second is composed of residues located in two adjacent subunits (at their interface), transArg95, transArg98, and Glu130, potentially to establish coordination between subunits in the hexameric ring (Fig. 1, C and D). Residues of the two putative pathways are sufficiently close to each other to directly support a cross-talk between the two networks based on mutually exclusive but dynamic pairwise interactions.

FIGURE 1.

Structural basis for putative PspF dimer cis and trans communication. Center panel shows the overlay of a putative PspF1–275 dimer (extracted from the hexamer model (Rappas et al. (25)) bound with MgATP (in light red, Protein Data Bank 2C9C) or with ADP (light blue, Protein Data Bank 2C98). Residues Glu81, Arg95, Glu97, Arg98, Glu130, and Arg131 are shown as sticks. The six subunits of the hexamer are numbered from ”n“ to ”n + 5.“ L1n represents loop 1 in subunit n; L1n+1 loop 1 in subunit ”n + 1.“ L2n represents loop 2 in subunit n; L2n+1 loop 2 in subunit n + 1. Zoom in subunit n shows the side chain orientations of residues Glu81, Arg91, Glu97, and Arg131 in the presence of MgATP (A) or ADP (B). Zoom in at the level of the putative interface shows the side chains orientation of the residues Arg95, Arg98, and Glu130 in the presence of MgATP (C) or ADP (D). Clear side chain orientation differences dependent on the nucleotide present are observed. Figure was generated using PyMOL.

Rationale for Choice of Targeted Residues, Covariance and Conservation

We examined whether the two putative networks described above were conserved among bacterial enhancer binding proteins (supplemental Fig. 1S). The positions corresponding to Glu81/Arg131 and Glu97/Arg131 pairs in PspF are clearly conserved (supplemental Fig. 1S, A and B). The Arg95/Glu130 equivalent pair is most frequently Arg-Glu (salt bridge) and then Leu-Arg (hydrogen-bound) followed by Lys-Glu (salt bridge), suggesting a high degree of functional conservation (supplemental Fig. 1SC). In the case of Arg98/Glu130, two pairs are well represented, Leu-Glu and Arg-Glu, whereas a multitude of additional combinations are observed (supplemental Fig. 1SD).

We reasoned that if the paired amino acids are indeed simply directly interacting for hexameric ring functionality and are not directly involved in any other activities, we should be able to invert the residues of the same pair without major effects on protein activity (e.g. Arg-Glu is substituted by Glu-Arg, and allele specific suppression is assessed). To do so, we measured the effect of double substitutions on protein activity compared with WT and single substitution variants. A second substitution compensating for a negative effect of a single substitution would provide clear evidence that the residues act as a pair. We constructed single, double, and triple variants using alanine substitutions as a control for Glu to Arg and Arg to Glu substitutions (supplemental Table 1S) to address the following contributions: (i) Glu81, Arg91, Glu97, and Arg131 for intrasubunit communication, and (ii) Arg95, Arg98, and Glu130 for intersubunit communication.

Single Substitution Effects on AAA+ Activator Activities

After purification, we tested whether the above PspF1–275 variants were functional (as in Ref. 38) in the following: (i) substrate remodeling; (ii) substrate interaction; (iii) ATP hydrolysis; and (iv) oligomerization.

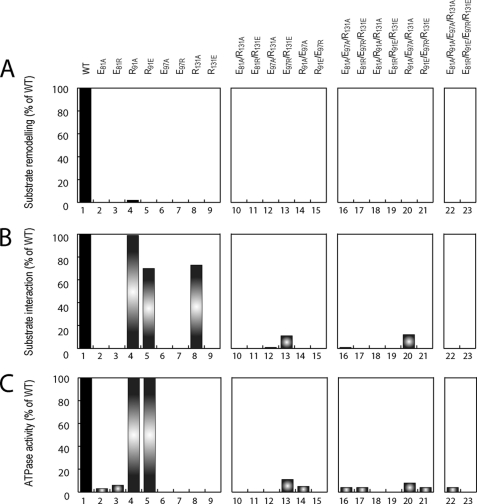

Each single substitution greatly reduced the ability of PspF1–275 to remodel its substrate, measured as a reduction in σ54-dependent transcription activation (Figs. 2A and 3A). Indeed, we were not able to detect any significant signal for the single substituted variants except for R91A (2% of WT, Fig. 2A, lane 4) and E130A (6% of WT, Fig. 3A, lane 6), suggesting that the substitutions used are targeting critical residues.

FIGURE 2.

cis variant functional activities. For each variant potentially involved in cis subunit communication, we tested the following: A, remodeling activity (transcription activation, as % of WT; maximal error is 14%); B, substrate interaction activity (binding to σ54 using ADP-AlFx, as % of WT; maximal error is 15%); and C, ATPase activity (as % of WT; maximal error is 10%).

FIGURE 3.

trans variant functional activities. For each variant potentially involved in trans subunit communication, we tested the following: A, remodeling activity (transcription activation, as % of WT; maximal error is 14%); B, substrate interaction activity (binding to σ54 using ADP-AlFx, as % of WT; maximal error is 15%); and C, ATPase activity (as % of WT; maximal error is 10%).

We next addressed whether the lack of substrate remodeling activity was due to a lack of interaction between PspF and its primary target, σ54. Using the transition state nucleotide analogue ADP-AlFx, a stable PspF-σ54 complex can be formed (39). In the presence of radiolabeled σ54, we only observed (Figs. 2B and 3B) complexes between σ54 and PspF1–275 WT (100%), R91A (99%), R91E (70%), R131A (73%), and E130A (8%). As expected, the variants able to remodel their substrate (R91A and E130A) can interact with σ54. Strikingly, R91E and R131A, which are inactive for substrate remodeling can interact stably with σ54 at a similar level to WT. These results suggest that Arg91 and Arg131 are directly involved in a pathway supporting substrate remodeling after the initial nucleotide-dependent substrate interaction.

To investigate whether the lack of remodeling activity observed with the variants able to interact with σ54 was due to defective energy coupling or a loss of ATPase activity, we performed ATPase assays. Variants R91A and R91E retained 100% activity (Fig. 2C, lanes 4 and 5), establishing that R91E ATPase activity is uncoupled from substrate remodeling. All the other single substitutions caused drastic reductions in ATPase activity (Figs. 2C and 3C). These residues are remote from the site of ATP hydrolysis and not predicted to be directly involved in ATPase activity, rather they may indirectly impact on the active site architecture.

In conclusion, single substitutions of these residues affect to a similar extent the final output (i.e. decrease the substrate remodeling activity) but have distinct defects as follows: decreased ATPase and/or substrate binding and/or signal coupling between ATPase and substrate remodeling activities.

Single Residue Substitutions at the Interface Affect Oligomer Organization

Many of the targeted residues chosen for this study are anticipated to be involved in intrasubunit communication or to be at the interface between subunits. Hence, we addressed whether these substitutions affected formation of the hexamer and subsequently the organization of the catalytic interface (to potentially account for decreased ATPase activity). Gel filtration experiments were conducted to assess the oligomeric states of the PspF1–275 variants (as described previously (33). For all the single variants, the equilibrium between apparent dimer and hexamer forms is displaced in favor of the dimeric form, suggesting that each substituted residue is functionally important for oligomer formation (data not shown). We tested whether the presence of nucleotide could favor high order oligomer formation, as is the case for WT (33), and observed a similar increase in self-association with all the variants except E97A/E97R, R95A/R95E, and R98E (supplemental Figs. 2S and 3S). In conclusion, these residues (Arg95, Glu97, and Arg98) impact on nucleotide-dependent oligomerization, suggesting that they play an important role in nucleotide-dependent protein organization.

Swapping Pair Residues Glu97 and Arg131 Restores Substrate Binding but Not Substrate Remodeling Activity

Having established the major changes in activities associated with single substitutions, we tested whether formation of salt bridges between the paired residues identified was sufficient to support all, or some, of the nucleotide-dependent activities. Based on the likelihood of intrasubunit communication (Fig. 1), we investigated the roles of Glu81, Arg91, Glu97, and Arg131. Recall these residues might relay and amplify conformational changes in the nucleotide binding pocket to L1 and L2. We constructed double, triple, and quadruple alanine and “pair swapping” variants (supplemental Table I) and determined whether these variants retained remodeling activity (Fig. 2A, lanes 10–23) but did not detect any. These results suggest requirements beyond just simple pairwise interactions between these residues for remodeling activity. However, the swapping pair E97R/R131E is clearly able to interact with the substrate (σ54), much better than the corresponding single substitutions, implying that the interaction between Glu97 and Arg131 is critical for engagement of L1 with substrate (Fig. 2B, lanes 10–15).

Glu97 may have more than one interacting partner (e.g. Glu97 interacts with Arg131 in the presence of ATP and with Arg91 in the presence of ADP, Fig. 1, A and B) prompting analysis of triple and quadruple substitutions (supplemental Table I). Substrate interactions of the E81A/R91A/R131A (2% of WT) and R91A/E97A/R131A (12% of WT) triple alanine variants were detected, but no substrate remodeling activity was observed (Fig. 2, A and B, compare lane 16 with 10 and 12 and lane 20 with 12 and 14).

These data imply that the substrate interaction activity of L1 is tightly regulated. Indeed, the correct presentation of the σ54-interacting motif cannot only be explained by the release of repressive interactions maintaining L1 in an “off” state (see results with variant E81A/R91A/E97A/R131A) but is also an outcome of “positive” interactions leading to an L1 “on” state. We have shown the importance of the Glu97/Arg131 pair for substrate engagement with L1 (swapping variant E97R/R131E) demonstrating that L2 residue Arg131 plays an active role in controlling L1 exposure. In addition, these results suggest that these residues are not only involved in one protein activity but several, probably via different “pair interactions.” The failure to identify substitutions that restore full oligomer activity strongly suggests the requirement of more than one subunit in the process, subunits most likely harboring different interacting pairs (due to different nucleotides bound) at the same time.

Glu97 Is Acting in Cis on Arg131

We next addressed whether Glu97/Arg131 communication was occurring in the same subunit (in cis) or between adjacent subunits (in trans). If mixing the two single variants E97R and R131E yields a gain of activity (compared with the starting activity of the single variants), then the residues are involved in intersubunit communication (in trans), whereas no change in activity suggests intrasubunit communication (in cis). Using a fixed PspF1–275 total concentration, we mixed E97R and R131E and all the possible combinations with E97A/E97R and R131A/R131E at ratios from 6:0 to 0:6 and tested the substrate binding (Fig. 4A and data not shown), remodeling (Fig. 4B, black bars, and data not shown), and ATPase (Fig. 4B, gray bars, and data not shown) activities. This “doping” experiment did not reveal any changes in substrate interaction or remodeling when compared with the results obtained with the corresponding single substitutions. In contrast, a substrate interaction complex was observed with the double variant E97R/R131E. These results demonstrate that the complementary effect observed in E97R/R131E is due to a “cis” complementation phenomenon (i.e. interactions are occurring in the same subunit). As expected, all the other combinations that were tried failed to change the activities tested (data not shown). In addition, a similar experiment was performed with combinations of single and double variants to try to mimic E81A/R91A/R131A and R91A/E97A/R131A, but no gain of function was observed (data not shown), again suggesting that the increased activities observed in the triple variants are due to in cis communication between these residues. We conclude that the functionally significant communication between Glu81, Glu97, Arg91, and Arg131 occurs via direct interactions in the same subunit (in cis) to control L1 use.

FIGURE 4.

E97R complements R131E activity in cis. Doping experiments using E97R and R131E are shown. A, native gel autoradiograph shows in lane 1 ADP-AlFx-dependent formation of a stable complex between PspF and 32P-σ54. Lanes 2–8 show the absence of this complex with σ54 using different E97R:R131E ratios as indicated. Lane 9 shows the signal obtained with the double variant E97R/R131E. Radioactivity was quantified, and the quantity of complex formed for each mixture is expressed as percent of complex formed with WT. B, same protein mixtures were used in substrate remodeling activities (black bars, transcription activation, as % of WT; maximal error is 14%) and ATPase activity (gray bars, as % of WT; maximal error is 10%).

Swapping Pair Residues Arg95/Glu130 or Arg98/Glu130 Support PspF Activity

Having shown that Glu97 and Arg131 in cis interaction is directly involved in coordinating L1-L2, we investigated the role of Arg95, Arg98, and Glu130 residues located at the subunit interface. To investigate this putative “in trans communication pathway,” we constructed double and triple alanine and pair swapping variants.

Consistent with the single alanine substitutions (Fig. 3), the double alanine variants are completely unable to stably interact with, or remodel, their substrate. In contrast, the “swapping” variants have significant remodeling activity (34% of WT for R95E/E130R and 45% of WT for R98E/E130R) also reflected by their substrate binding ability (Fig. 3B), whereas the corresponding single substitutions were inactive (Fig. 3A, compare lane 9 with 3 and 7, and lane 11 with 5 and 7). The role of Arg95/Glu130 and Arg98/Glu130 pairs seems to be similar in terms of substrate remodeling activity. Nevertheless, these two pairs can be differentiated based on the intrinsic protein activities (ATPase and oligomerization activities (Fig. 3C and supplemental Fig. 3S)). R95E/E130R can form an apparent constitutive hexamer, although R98E/E130R oligomerization is dependent on protein concentration and is nucleotide-sensitive (as is WT, see supplemental Fig. 3S). This result suggests that, in contrast to Arg95/Glu130, the Arg98/Glu130 interaction is crucial for oligomeric ring organization. The differential ATPase activities of R95E/E130R (42% of WT activity) and R98E/E130R (100% of WT activity) further demonstrate an unequal contribution of these two pairs in the global activity of the hexamer (Fig. 3C). The lack of activity observed with R95E/R98E/E130R seems to be due to a major defect in self-assembly (no oligomer detected in gel filtration, see supplemental Fig. 3S). In contrast, R95A/R98A/E130A, although unable to interact with and remodel its substrate, exhibited full ATPase activity (Fig. 3C, lane 13). Taken together, these data suggest important roles for the Arg95, Arg98, and Glu130 side chains in establishing productive interactions to allow the optimal hexamer activity, potentially acting in trans as explored below.

Arg95 and Arg98 Are Acting in Trans on Glu130

We established the importance of Arg95/Glu130 and Arg98/Glu130 pairs without knowing whether any direct interactions between these residues involved one or several subunits. As our initial hypothesis was that Glu130 could interact with transArg95 and/or transArg98, we tested whether the effect observed in the pair swapping variants was due to the communication between residues from adjacent subunits (in trans) or in the same subunit (in cis). We performed “doping experiments by mixing two single variants at different ratios. If residues are involved in intersubunit communication (trans) we should observe a gain of activity compared with the starting activity of the single variants. The single substitutions R95E, R98E, and E130R are inactive for substrate binding and remodeling, facilitating detection of any gain of function upon mixing. At a fixed PspF1–275 total concentration, we mixed R95E and E130R or R98E and E130R at varying ratios and analyzed their substrate binding (Fig. 5, A–C), remodeling (Fig. 5, B–D, black bars), and ATPase (Fig. 5, B–D, gray bars) activities. For both R95E and E130R or R98E and E130R pairs, we observed a gain of activity in the mixing experiments, compared with the single substitution alone, maximal at a ratio of 3:3, demonstrating that the interaction between these residues are critical for oligomeric ring activity. Mixing R95A and E130A or R98A and E130A or all the combinations possible with R95A/R95E, R98A/R98E, and E130A/E130R gave no gain of activity (data not shown). We conclude that the functional interaction between transArg95/Glu130 and transArg98/Glu130 occurs between two adjacent subunits probably via the interaction (formation of a salt bridge) between the side chains of Glu130 and either transArg95 or transArg98.

FIGURE 5.

R95E or R98E complement E130R activity in trans. Doping experiments using R95E and E130R or R98E and E130R are shown. The native gel autoradiograph shows the formation of a stable complex between PspF and 32P-σ54 in the presence of ADP-AlFx. Lane 1 is the positive control showing the complex formed with WT. Lanes 2–8 show the complex formation using different R95E:E130R (A) or R98E:E130R (C) ratios (as indicated). Lane 9 shows the signal obtained with the double variant corresponding to R95E/E130R or R98E/E130R. Radioactivity was quantified, and the quantity of complex formed for each mixture is expressed as percentage of complex formed with WT. The same protein mixtures for R95E/E130R (B) or R98E/E130R (D) were used in substrate remodeling activities (black bars, transcription activation, as % of WT; maximal error is 14%) and ATPase activity (gray bars, as % of WT; maximal error is 10%).

Differential Role of Arg95/Glu130 and Arg98/Glu130 Pairs in ATPase Activity

As the pair swapping variants R95E/E130R and R98E/E130R exhibit different ATPase activities (42 and 100% of WT, respectively) to evaluate in cis and in trans effects, we examined the extent to which mixing of the corresponding single variants impacted upon ATPase activities. Strikingly, we observed when mixing R95E and E130R from a 1:5 to 5:1 ratio, the apparent ATPase activity remains constant (about 50% of WT) and similar to the double variant R95E/E130R (Figs. 5B and 2D, gray bars). In contrast, when mixing R98E and E130R, we observed the ATPase activity changes with the protein ratios, with an optimal activity observed when using the ratio 3:3 (Fig. 5, B-2D, gray bars). These results clearly demonstrate that Arg95 and Arg98 have distinct roles and contributions to the hexameric ring activity.

We conclude that the Arg98/Glu130 interaction is necessary and sufficient to allow full ATPase activity, whereas the Arg95/Glu130 interaction seems to negatively impact on the hexamer ATPase active site. We propose that the 50% ATPase activity observed with R95E/E130R is due to a lack of communication caused by the inability of Arg98 to interact with Glu130 from which we infer the following: (i) there is communication between subunits, and (ii) all catalytic sites are not independent. These outcomes further emphasize the importance of subunit-subunit communication for the ATPase and remodeling activities of the ring.

DISCUSSION

The conserved AAA+ protein core has become specialized by the insertion of structural motifs allowing nucleotide-dependent specific substrate binding and remodeling. Understanding the nucleotide-driven mechanisms of action is of basic interest and practical importance. For one type member AAA+ protein (PspF), we have now established the functional significance of strategically placed residues for “cis” and “trans” subunit communication in supporting coordination between subunits for nucleotide-dependent substrate remodeling (Fig. 6). Our data establish that subunits of the hexameric ring are not independent for activity and that at least two adjacent subunits need to be coordinated in their function (by transArg95–transArg98–Glu130 residues) to allow optimal substrate binding and remodeling.

FIGURE 6.

Model of cis and trans communication pathways for coordinated activity. From our experimental data and the previous structural model of the interface between PspF subunits, we propose a mechanism where cis and trans communication pathways are linked together. When ATP is bound in subunit n, Glu97 interacts with Arg131 (in L2n) and Glu130 (just adjacent to Arg131 in L2n) with transArg98 (adjacent to Glu97n+1) allowing the exposure of L1n. These interactions will fully change in the presence of bound ADP. At this point, Glu97 interacts with Arg91 (L1n), whereas Glu81 interacts with Arg131 (L2n), which is expected to change the presentation of L1n from an exposed to a more buried conformation. At the same time the bound nucleotide signal will be propagated to the adjacent subunit by the new interaction made between Glu130 and transArg95.

An “in Cis” Pathway for L1-L2 Coordination

In this study, we investigated the roles of Glu81, Glu97, Arg91, and Arg131 in the putative signaling pathway used for establishing PspF substrate binding and remodeling activities. Glu81, Glu97, and Arg131 were suggested to take part in such a pathway but remained without functional characterization (24–26). Here, we have identified a key residue (Arg91) with a crucial and unexpected role in the coordination of L1 and L2. The location of these residues (Fig. 1) and their conservation (supplemental Fig. 1S) suggested roles in an L1-L2 coordination regulatory pathway. Residues Glu81 and Arg91 are located at the extremities of L1, Arg131 at the beginning of L2 (and adjacent to Glu130), and Glu97 in the second part of helix 3 between the conserved Arg95 and Arg98 residues involved in the “trans” communication pathway.

Substitutions of Arg91 had (i) no effect on ATPase activity (Fig. 2C, lanes 4 and 5) and (ii) only moderately decreased substrate interaction when the charge was inverted (R91E, Fig. 2B, lanes 4 and 5) but had (iii) a very drastic negative effect on substrate remodeling. This last observation establishes that the role of this residue is crucial in coupling ATPase activity and substrate remodeling after the initial substrate interaction.

In this study, we also directly demonstrate the importance of the conserved pair Glu97/Arg131 on protein activity by restoring some activity in the swapping variant E97R/R131E (Fig. 2, lane 13). The Glu97 and Arg131 single substitutions completely abolish ATPase activity and substrate interaction activity (Fig. 2, lanes 6–9) except for R131A, which retained significant substrate interaction activity but no ATPase (Fig. 2, lane 8). This last result suggests more than one role of the Glu97/Arg131 pair and the involvement of Glu97 and Arg131 in interactions with other residues. We propose that Glu97 could have two roles during substrate remodeling. The first role will be to coordinate L1-L2 (via Arg131 interaction) to allow L1 to interact with the substrate, and the second will be to permit the coupling of ATPase to substrate remodeling after the initial binding event (via Arg91 interaction). Unfortunately, because Glu97 affects the initial substrate-binding interaction (R91E/E97R, Fig. 2, lane 15), subsequent roles are difficult to assay. Nevertheless, our functional data strongly suggest that Glu97 is pivotal in different interaction pairs for the L1-L2 coordination needed for substrate interaction and remodeling.

Roles of Arg95 and Arg98 in Fine-tuning of the Hexameric Ring Activity

Structural data obtained by nucleotide soaking (26) suggested that the Glu130 side chain orientation might change to allow the transArg98/Glu130 interaction to occur in the ATP-bound state and the alternative transArg95/Glu130 interaction in the ADP-bound state (with the limitations discussed before concerning the model in Fig. 1). Here, we revealed that transArg95/Glu130 and transArg98/Glu130 pairs are involved in nucleotide-dependent subunit coordination, which is necessary for both substrate binding and remodeling. The results obtained studying the “trans” pathway, which involves residues distant from the substrate interaction motif (contained in L1), demonstrate that more than one subunit is involved in substrate binding and remodeling. Indeed, we established that productive L1 exposure is regulated by the coordination between adjacent subunits.

One question of major interest is the nature of the ATPase cycle taking place in the AAA+ oligomeric ring. Four possibilities have been described as follows: stochastic, synchronized, sequential, and rotational ATPase mechanisms (11). The identification and characterization of Arg95, Arg98, and Glu130 variants are of special interest because they provide evidence that the PspF ATPase cycle is unlikely to be stochastic (and so different to the proposed mechanism for ClpX (40), a member of the same AAA+ clade). This is consistent with our previous observations with PspF, showing stimulation of ATPase activity by ADP and inhibition of ATPase by excess ATP (33).

In addition, and not obvious from the structural model, the contributions of paired residues are different at the level of ATPase activity: Arg98/Glu130 (R98E/E130R 100% of WT) seems crucial for ATPase activity, whereas Arg95/Glu130 (R95E/E130R 42% of WT) seems more dispensable, consistent with a concerted ATPase mechanism where R95A (giving a locked Arg98/Glu130 interaction) and R98A (giving a locked Arg95/Glu130 interaction) are almost inactive for ATP hydrolysis.

We propose that switching between the transArg98/Glu130(ATP) and transArg95/Glu130(ADP) interactions is central to achieving coordination between adjacent subunits in the hexamer and is required for full ring activities, further demonstrating the subunit coordination requirement for ATPase, substrate interaction, and substrate remodeling activities.

Identification of a New Class of Uncoupling Variant

Two uncoupling variants, R91A and R95A/R98A/E130A, were identified, retaining full ATPase activity but failing to couple nucleotide binding to either substrate remodeling or substrate binding, respectively, although retaining an intact substrate-interacting L1 motif (distinct from all of the other reported uncoupling variants). Despite both failing to remodel their substrate, these two variants affect distinct steps in the remodeling pathway.

Arg91 is located at the end of L1 and is proposed (in this study) to contribute to controlling L1 exposure. We established that the uncoupling phenotype observed with this variant is due the lack of a productive “movement” of L1 after the initial contact with the target, probably because of the absence of Arg91/Glu97 interaction (Fig. 6). The lack of Arg95, Arg98, and Glu130 side chains (R95A/R98A/E130A) leads to a full but completely unproductive ATPase activity. Interestingly, this variant was not expected to fail to interact with the substrate because the substituted residues are located far from the substrate-interacting motif. This observation fully supports the proposal that nucleotide-dependent coordination between subunits is important for substrate binding, implying that more than one subunit of the oligomeric ring is required for substrate interaction and remodeling. Importantly, and for the first time, we uncovered a class of variants unable to remodel the target σ54 but that retained self-association and ATPase activities. This class of mutant is most probably defective in the coordination of conformational change between subunits. Below, we propose that communication pathways like those described for PspF exist and operate in many AAA+ proteins.

An Underlying Pathway

Due to the different locations of the particular substrate-associated interaction insertions (L1 and L2 in this study) and because of their different amino acid sequences, it is not anticipated that the exact pairs of residues identified here will be universally found across the AAA+ protein family. Nevertheless, the current insights obtained with PspF could more generally support investigation into subunit organization and communication within AAA+ ring assemblies. Inspection of some AAA+ protein structures (PspF, NtrC1, NtrC4, Cdc6P, ZraR, ClpX, FtsH, BChi, Vps4, LTag, RuvB, and ClpA) revealed sets of interacting amino acid pairs likely to be functionally equivalent to the pairs studied in PspF (supplemental Fig. 4S). The absence of sufficiently high resolution or appropriate nucleotide-bound structures precludes an exhaustive search for other examples, which are anticipated to exist.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. P. C. Burrows, Dr. J. Guergnon, Dr. J. Morvan, Dr. J. Schumacher, and Dr. S. R. Wigneshweraraj for valuable comments on the manuscript. We are grateful to L. H. Chung for contributions in in vivo preliminary screening. We also thank the members of the Buck laboratory for helpful discussions and friendly support.

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council Grant BB/G001278/1.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table I, Figs. S1–S4, and additional references.

- DTT

- dithiothreitol

- WT

- wild type.

REFERENCES

- 1.Konakova M., Pulst S. M. (2005) J. Mol. Neurosci. 25, 105–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guinto J. B., Ritson G. P., Taylor J. P., Forman M. S. (2007) Acta Neuropathol. 114, 55–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kimonis V. E., Watts G. D. (2005) Alzheimer Dis. Assoc. Disord. 19, S44–S47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watts G. D., Mehta S. G., Zhao C., Ramdeen S., Hamilton S. J., Novack D. V., Mumm S., Whyte M. P., Mc Gillivray B., Kimonis V. E. (2005) Hum. Genet. 118, 508–514 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Watts G. D., Thomasova D., Ramdeen S. K., Fulchiero E. C., Mehta S. G., Drachman D. A., Weihl C. C., Jamrozik Z., Kwiecinski H., Kaminska A., Kimonis V. E. (2007) Clin. Genet. 72, 420–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Watts G. D., Wymer J., Kovach M. J., Mehta S. G., Mumm S., Darvish D., Pestronk A., Whyte M. P., Kimonis V. E. (2004) Nat. Genet. 36, 377–381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weihl C. C., Dalal S., Pestronk A., Hanson P. I. (2006) Hum. Mol. Genet. 15, 189–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zou J. X., Guo L., Revenko A. S., Tepper C. G., Gemo A. T., Kung H. J., Chen H. W. (2009) Cancer Res. 69, 3339–3346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iyer L. M., Leipe D. D., Koonin E. V., Aravind L. (2004) J. Struct. Biol. 146, 11–31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogura T., Matsushita-Ishiodori Y., Johjima A., Nishizono M., Nishikori S., Esaki M., Yamanaka K. (2008) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 36, 68–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ogura T., Wilkinson A. J. (2001) Genes Cells 6, 575–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Augustin S., Gerdes F., Lee S., Tsai F. T., Langer T., Tatsuta T. (2009) Mol. Cell 35, 574–585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bell S. P., Dutta A. (2002) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 71, 333–374 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Forsburg S. L. (2004) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 109–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bochman M. L., Schwacha A. (2008) Mol. Cell 31, 287–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Briggs L. C., Baldwin G. S., Miyata N., Kondo H., Zhang X., Freemont P. S. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13745–13752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Greenleaf W. B., Shen J., Gai D., Chen X. S. (2008) J. Virol. 82, 6017–6023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang X., Chaney M., Wigneshweraraj S. R., Schumacher J., Bordes P., Cannon W., Buck M. (2002) Mol. Microbiol. 45, 895–903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Darwin A. J. (2005) Mol. Microbiol. 57, 621–628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhang X., Wigley D. B. (2008) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 1223–1227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kim T. K., Ebright R. H., Reinberg D. (2000) Science 288, 1418–1422 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin Y. C., Choi W. S., Gralla J. D. (2005) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 603–607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bordes P., Wigneshweraraj S. R., Schumacher J., Zhang X., Chaney M., Buck M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 2278–2283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burrows P. C., Schumacher J., Amartey S., Ghosh T., Burgis T. A., Zhang X., Nixon B. T., Buck M. (2009) Mol. Microbiol. 73, 519–533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rappas M., Schumacher J., Beuron F., Niwa H., Bordes P., Wigneshweraraj S., Keetch C. A., Robinson C. V., Buck M., Zhang X. (2005) Science 307, 1972–1975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rappas M., Schumacher J., Niwa H., Buck M., Zhang X. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 357, 481–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rappas M., Bose D., Zhang X. (2007) Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 17, 110–116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Martin A., Baker T. A., Sauer R. T. (2008) Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 15, 1147–1151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martin A., Baker T. A., Sauer R. T. (2008) Mol. Cell 29, 441–450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mott M. L., Erzberger J. P., Coons M. M., Berger J. M. (2008) Cell 135, 623–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hersch G. L., Burton R. E., Bolon D. N., Baker T. A., Sauer R. T. (2005) Cell 121, 1017–1027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moreau M. J., McGeoch A. T., Lowe A. R., Itzhaki L. S., Bell S. D. (2007) Mol. Cell 28, 304–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joly N., Schumacher J., Buck M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 34997–35007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bose D., Pape T., Burrows P. C., Rappas M., Wigneshweraraj S. R., Buck M., Zhang X. (2008) Mol. Cell 32, 337–346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wigneshweraraj S. R., Nechaev S., Bordes P., Jones S., Cannon W., Severinov K., Buck M. (2003) Methods Enzymol. 370, 646–657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cannon W. V., Gallegos M. T., Buck M. (2000) Nat. Struct. Biol. 7, 594–601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lowry O. H., Rosebrough N. J., Farr A. L., Randall R. J. (1951) J. Biol. Chem. 193, 265–275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Joly N., Burrows P. C., Buck M. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 13725–13735 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chaney M., Grande R., Wigneshweraraj S. R., Cannon W., Casaz P., Gallegos M. T., Schumacher J., Jones S., Elderkin S., Dago A. E., Morett E., Buck M. (2001) Genes Dev. 15, 2282–2294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Martin A., Baker T. A., Sauer R. T. (2005) Nature 437, 1115–1120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]