Abstract

Objective

Free radical-mediated reactions have been implicated as contributors in a number of autoimmune disease (ADs) including SLE. However, potential of oxidative/nitrosative stress in eliciting an autoimmune response, or in disease prognosis and pathogenesis in humans remains largely unexplored. This study investigates the status and contribution of oxidative/nitrosative stress in SLE.

Methods

Sera from 72 SLE patients with various SLE scores [SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI)] and 36 age- and gender-matched controls were evaluated for oxidative/nitrosative stress markers, such as anti-malondialdehyde (MDA)- and anti-4-hydroxynonenal (HNE)-protein adduct antibodies, MDA-/HNE-protein adducts, superoxide dismutase (SOD), nitrotyrosine and iNOS.

Results

Serum analysis showed significantly higher levels of both anti-MDA-/anti-HNE-protein adduct antibodies and MDA-/HNE-protein adducts in SLE patients. Interestingly, our data showed not only increased number of subjects positive for anti-MDA- or anti-HNE-protein antibodies, but also greater increases in both these antibodies in SLE patients with greater SLEDAI (≥ 6), which were significantly higher than the lower SLEDAI group (<6). Data also showed a significant correlation between anti-MDA or anti-HNE antibodies and SLEDAI (r = 0.734 and 0.647 for anti-MDA and anti-HNE antibodies, respectively) suggesting a possible causal relationship between these antibodies and SLE. Furthermore, sera from SLE patients had lower levels of SOD, and higher levels of iNOS and nitrotyrosine.

Conclusion

Our findings support an association between oxidative/nitrosative stress and SLE. Stronger response in samples with higher SLEDAI suggests that oxidative/nitrosative stress markers may be useful in evaluating the progression of SLE as well as in elucidating the mechanisms of disease pathogenesis.

Keywords: SLE, Anti-MDA antibodies, Anti-HNE antibodies, SOD, iNOS, Nitrotyrosine

INTRODUCTION

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is a multifactorial autoimmune disease (AD), characterized by several clinical manifestations and appearance of multiple autoantibodies (1–3). Approximately 70–90% of SLE patients are females, and this chronic life-threatening disorder which affects a large population, has been associated with higher risk of cardiovascular disease (1,4). Although it is believed that the etiology of SLE is multifactorial, including genetic, hormonal and environmental triggers, the molecular mechanisms underlying this systemic autoimmune response remain largely unknown. In recent years, free radical-mediated reactions have drawn considerable attention as the potential mechanism in the pathogenesis of SLE (2–5). Studies using an autoimmune-prone MRL+/+ mouse model also suggested an association between oxidative/nitrosative stress and autoimmunity (5–8). However, relevance of oxidative/nitrosative stress in the pathogenesis and progress of SLE in humans is not fully understood.

Excessive generation of reactive oxygen species (ROS), i.e., superoxide anion (O2˙−) and/or hydroxyl radicals (˙OH), have the potential to initiate damage to lipids, proteins and DNA (9,10). Antioxidant defense systems, such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and catalase, keep ROS production in check thereby maintaining an appropriate cellular redox balance. Alterations in this redox balance resulting from elevated ROS and/or decreased antioxidant levels lead to oxidative stress (10,11). Lipid peroxidation (LPO), an oxidative degeneration of polyunsaturated fatty acids set into motion by ROS, leads to formation of highly reactive aldehydes such as malondialdehyde (MDA) and 4-hydroxynonenal (4-HNE), which can bind covalently to proteins resulting in their structural modifications and affecting biological functions (12–15). Increases in oxidative stress (12,16–18) and formation of MDA- and HNE-modified proteins (4,7,12,19–21) are associated with SLE/ADs. However, potential role of oxidative stress, especially the consequences of oxidative modification of proteins by MDA and HNE in the pathogenesis and progression of SLE remains unresolved.

Like ROS, reactive nitrogen species (RNS) could also play a significant role in the pathogenesis of SLE, and have drawn significant attention in recent years. Nitric oxide (˙NO), generated by the enzyme inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS), is one of the most important and widely studied RNS. The potential of ˙NO in disease pathogenesis lies largely to the extent of its production and generation of O2˙−, leading to formation of peroxynitrite (ONOO−). ONOO− is a potent nitrating and oxidizing agent which can react with tyrosine residues to form nitrotyrosine (NT; 22–24). In addition, ONOO−-mediated modifications of endogenous proteins and DNA may enhance their immunogenicity, leading to a break in immune tolerance (2,25,26). Accumulating evidence in murine lupus shows increasing iNOS activity with the development and progression of ADs, and studies using competitive inhibitors suggest that iNOS could play a pathogenic role in murine ADs (8,22,23,27). Also elevated NT, a stable end product of increased RNS production, has been identified in many disease conditions including ADs (8,18,25,28,29). Growing observational data in humans also suggest that overexpression of iNOS and increased production of ONOO− may contribute to glomerular and vascular pathology and in the pathogenesis of many other ADs (18,30–32).

Even though reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) have been implicated in the pathogenesis of SLE, the potential of RONS in eliciting an autoimmune response and contribution to disease progression and pathogenesis remains largely unexplored. We hypothesize that overproduction of RONS, such as O2˙−,˙OH, ˙NO and ONOO− leads to a variety of RONS-mediated modifications of the endogenous proteins, such as increased formation of MDA-, HNE- and NO2-protein adducts, and thus generation of neoantigens. After antigen processing, these neoantigens can elicit autoimmune responses by stimulating T and B lymphocytes. To assess this hypothesis and establish a link between RONS and SLE, we examined the levels of anti-MDA-/HNE-protein adduct antibodies, MDA-/HNE-protein adducts, SOD, NT and iNOS in serum of SLE patients, and analyzed their relationship with SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI). Our results not only support an association between oxidative/nitrosative stress and SLE, but also suggest that oxidative/nitrosative stress markers may be important in the evaluation of SLE progression as well as elucidation of the mechanisms in disease pathogenesis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients and Serum Preparation

The study group included 72 SLE patients (62 females and 10 males), as defined by the American College of Rheumatology 1997 revised criteria (33), and the age range 22–65 years (47.2 ± 10.8). The SLE disease activity index (SLEDAI) was determined using the SLE Disease Activity Measure (34,35), and the SLEDAI scores among SLE patients ranged from 0–38 (10.7 ± 10.0). These SLE patients were divided into two groups based on the SLEDAI: low SLEDAI group comprised 28 SLE patients (24 females and 4 males) with SLEDAI < 6, age range 22–65 years (48.5 ± 12.1), and high SLEDAI group comprised 44 SLE patients (38 females and 6 males) with SLEDAI ≥ 6, age range 23–64 years (46.4 ± 9.9). The control group comprised 36 healthy subjects (31 females and 5 males) age range 21–74 years (43.1 ± 13.7). Mean ages of the two SLE subgroups and the normal control group were not statistically different. The racial/ethnic and gender composition of the SLE groups were comparable to the control group. The study was approved by UTMB Institutional Review Board (IRB). Venous blood samples from controls and SLE patients were collected and serum from individual subjects was stored in small aliquots at −80°C until further analysis.

ELISAs for anti-MDA- and anti-HNE-protein adduct specific antibodies in the serum

Anti-MDA- and anti-HNE-protein adduct antibodies in the sera of SLE patients and controls were analyzed by ELISA methods established in our laboratory (5–7). Briefly, flat-bottomed 96-well microtiter plates were coated with MDA-/HNE-ovalbumin adducts or ovalbumin (0.5 µg/well) overnight at 4 °C. The plates were washed with tris-buffered saline-Tween 20 (TBST) and the non-specific binding sites were blocked with TBS containing 1% BSA (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) at room temperature (RT) for 1 hr. After washing extensively with TBST, 50 µl of 1:100 diluted serum samples were added to duplicate wells of the coated plates and incubated at RT for 2 hr. The plates were washed 5 times with TBST and then 50 µl goat anti-human IgG-HRP (1:15000 in TBS; Chemicon, Temecula, CA) was added and incubated at RT for 1 hr. After washing, 100 µl of TMB peroxidase substrate (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) was added to each well. The reaction was stopped after 10 min by adding 100 µl 2 M H2SO4 and the OD was read at 450 nm on a Bio-Rad Benchmark plus microplate spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Quantitation of MDA- and HNE-protein adducts in the serum

For the quantitation of MDA- and HNE-protein adducts in the sera of SLE patients and controls, competitive ELISAs were preformed as described earlier (36–38). Briefly, flat bottomed 96-well microtiter plates were coated with MDA-/HNE-ovalbumin adducts or ovalbumin (0.5 µg/well) overnight at 4 °C. For the competitive ELISA, rabbit antisera [anti-MDA (1:2000 diluted) or anti-HNE (1:3000 diluted), Alpha Diagnostics, San Antonio, TX] were incubated with test samples (standards or unknown) at 4 °C overnight. The coated plates were blocked with a blocking buffer (Sigma) for 2 h at RT, then a 50 µl aliquot of each of the above mentioned incubation mixtures was added to duplicate wells and incubated for 2 h at RT. After washing, 50 µl of goat anti-rabbit IgG-HRP (1:2000 diluted, Millpore, Billerica, MA) was added and incubated for 1 h at RT. After washing, 100 µl of TMB peroxidase substrate (KPL) was added to each well. The reaction was stopped after 10 min by adding 100 µl 2 M H2SO4 and the absorbance was read at 450 nm on a Bio-Rad Benchmark plus microplate spectrophotometer (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Determination of Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase

Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (SOD) level in the serum was determined by using an ELISA kit (Bender MedSystems, Burlingame, CA).

Quantification of nitrotyrosine and iNOS in serum

Nitrotyrosine (NT) levels in the serum were quantitated by using an ELISA kit (Cell Sciences, Norwood, MA), whereas iNOS was detected by an ELISA developed in our laboratory (6).

Statistical analysis

The values are means ± SD. One-way ANOVA followed by Tukey-Kramer multiple comparisons test (GraphPad Instat 3 software, La Jolla, CA) was performed for the statistical analysis. A p value < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. Spearman’s rank correlation was used to calculate correlation coefficients between serum levels of anti-MDA-and anti-HNE-protein adduct antibodies and SLEDAI scores.

RESULTS

Anti-MDA- and anti-HNE-protein adduct antibodies in the sera of SLE patients

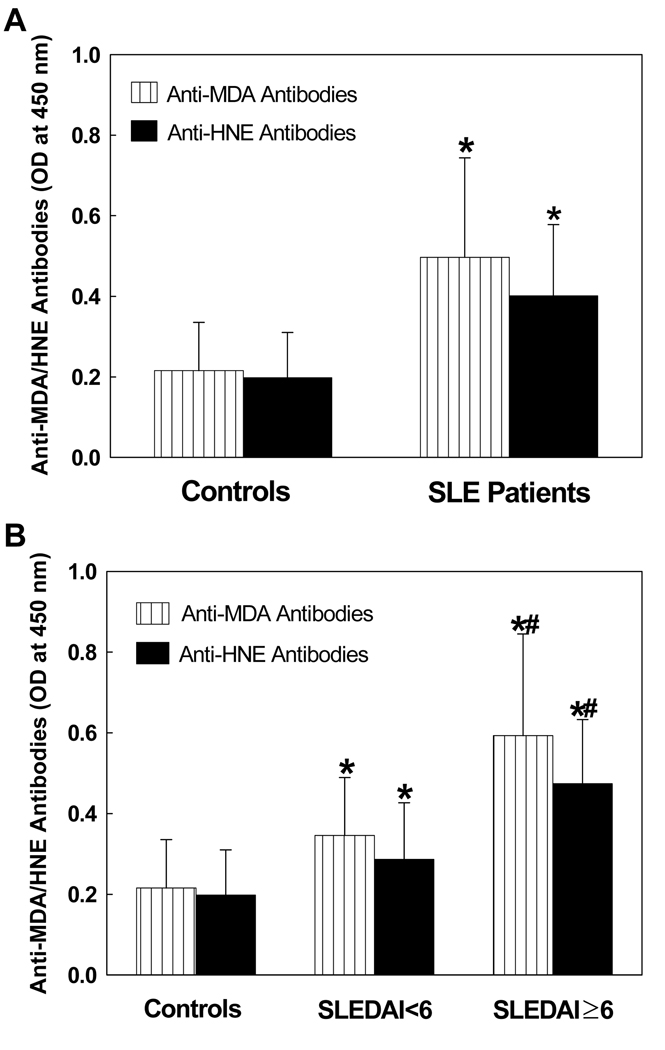

MDA and HNE are two major lipid peroxidation-derived aldehydes (LPDA) and generally represent as the biomarkers of oxidative stress (5–7,19,37,39). In an attempt to understand the role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of SLE, we first determined serum levels of MDA-and HNE- specific antibodies in patients with SLE vs. age- and gender-matched controls (Fig. 1A). As shown in Fig.1A, serum levels of anti-MDA-protein adduct antibodies in SLE patients were significantly higher in comparison to the controls. Similarly, the serum levels of anti-HNE-protein adduct antibodies also increased significantly in SLE patients. Since both MDA and HNE are highly reactive LPDAs and able to form adducts with proteins (37,40), the greater serum levels of anti-MDA-protein and anti-HNE-protein antibodies in SLE patients not only suggest increased LPO, but also a potential role of LPO in the pathogenesis of SLE through covalent modification of endogenous macromolecules.

Figure 1.

(A) Anti-MDA- and anti-HNE-protein adduct antibodies in the sera of SLE patients (n=72) and control subjects (n=36). The antibodies were determined by specific ELISAs. (B) Serum anti-MDA- and anti-HNE-protein adduct antibodies in SLE patients with SLEDAI < 6 (n=28) and SLEDAI ≥ 6 (n=44) vs. controls (n=36). The results are means ± SD. * p < 0.05 vs. controls; # p < 0.05 vs. SLEDAI < 6.

SLEDAI related increases of anti-MDA- and -HNE-protein adduct antibodies in the serum of SLE patients

To validate our hypothesis that oxidative stress may be involved in the SLE, we assessed the increases in serum anti-MDA and anti-HNE antibodies as a function of SLEDAI (Fig. 1B & Tables 1, 2). As evident from Fig.1B, the levels of anti-MDA-protein adduct antibodies in the SLE patients, both SLEDAI < 6 and SLEDAI ≥ 6, were significantly higher in comparison to the controls. Interestingly, the increases were significantly greater in patients with SLEDAI ≥ 6 vs. the patients with SLEDAI < 6 (Fig. 1B). Moreover, the percentage of samples positive (+) and highly positive (++) for anti-MDA-protein adduct antibodies were significantly higher in the SLE patients with SLEDAI < 6 (+ 37.5%, ++ 37.5 %, respectively) compared to the controls (+ 22.2%, ++ 5.6%, Table 1). Interestingly, the increases in these antibodies were even higher in the SLE patients with SLEDAI ≥ 6 [+ 18.2%, ++ 38.6%, +++ 38.6% (+++, strongly positive), respectively, Table 1]. Similarly, serum levels of anti-HNE-protein adduct antibodies, and the percentage of serum samples positive for anti-HNE-protein adduct antibodies (19.5% for controls vs. 60.7% for SLEDAI < 6 and 95.5% for SLEDAI ≥ 6) were also greater in SLE patients in both SLEDAI < 6 and SLEDAI ≥ 6 (Fig. 1B & Table 2). Significantly higher increases in the levels of serum anti-MDA-/anti-HNE-protein adduct antibodies and even higher percentage of highly positive or strongly positive anti-MDA-/anti-HNE-protein adduct antibodies in SLE patients with higher SLEDAI (≥ 6) [compared to SLE patients with lower SLEDAI (< 6) and/or controls] suggest that increased lipid peroxidation is associated with the progression of the disease activity. Our data also suggests that lipid peroxidation could play a potential role in the pathogenesis of SLE.

Table 1.

The number and percentage of anti-MDA-protein antibody positive sera in SLE patients and control subjects*

| Antibody Response | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | + | ++ | +++ | ||||||

| Total No. | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Controls | 36 | 26 | 72.2 | 8 | 22.2 | 2 | 5.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| SLEDAI < 6 | 28 | 8 | 28.6 | 10 | 35.7 | 10 | 35.7 | 0 | 0.0 |

| SLEDAI ≥ 6 | 44 | 2 | 4.5 | 8 | 18.2 | 17 | 38.6 | 17 | 38.6 |

−, negative; +, moderately positive; ++, highly positive; +++, strongly positive (see methods for details).

Table 2.

The number and percentage of anti-HNE-protein antibody positive sera in SLE patients and control subjects*

| Antibody Response | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| − | + | ++ | +++ | ||||||

| Total No. | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Controls | 36 | 29 | 80.6 | 6 | 16.7 | 1 | 2.8 | 0 | 0.0 |

| SLEDAI < 6 | 28 | 11 | 39.3 | 12 | 42.9 | 4 | 14.3 | 1 | 3.6 |

| SLEDAI ≥ 6 | 44 | 2 | 4.5 | 13 | 29.5 | 21 | 47.7 | 8 | 18.2 |

−, negative; +, moderately positive; ++, highly positive; +++, strongly positive (see methods for details).

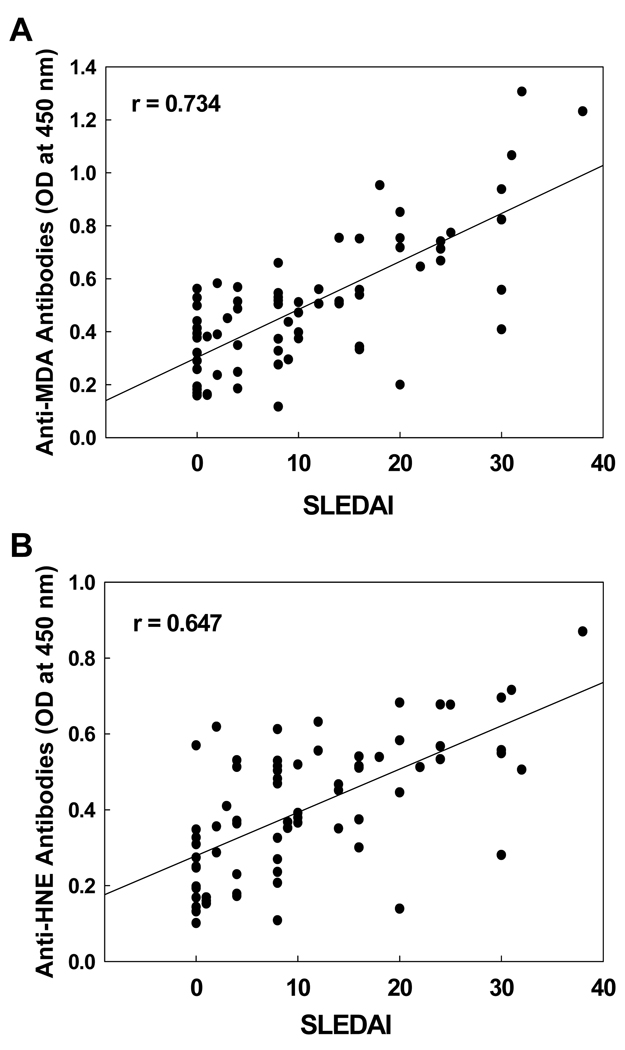

Correlation of serum anti-MDA and anti-HNE antibodies with SLEDAI

To further evaluate the significance of oxidative stress in SLE, the relationship of the increases in serum anti-MDA/anti-HNE antibodies with SLEDAI was analyzed (Fig. 2). A significant correlation was observed between anti-MDA-protein adduct antibodies and SLEDAI (r = 0.734, p < 0.01; Fig. 2A). Similarly, a significant correlation was also obtained between anti-HNE-protein adduct antibodies and SLEDAI (r = 0.647, p < 0.01; Fig. 2B). These results not only further support the potential role of lipid peroxidation in SLE, but also suggest that the serum anti-MDA- and anti-HNE-protein adduct antibodies may be useful in predicting the progression of SLE.

Figure 2.

Correlation of serum anti-MDA-protein antibodies (A) or anti-HNE-protein antibodies (B) with SLEDAI. The correlation was established by calculating correlation coefficients between anti-MDA-protein antibodies or anti-HNE-protein antibodies and SLEDAI.

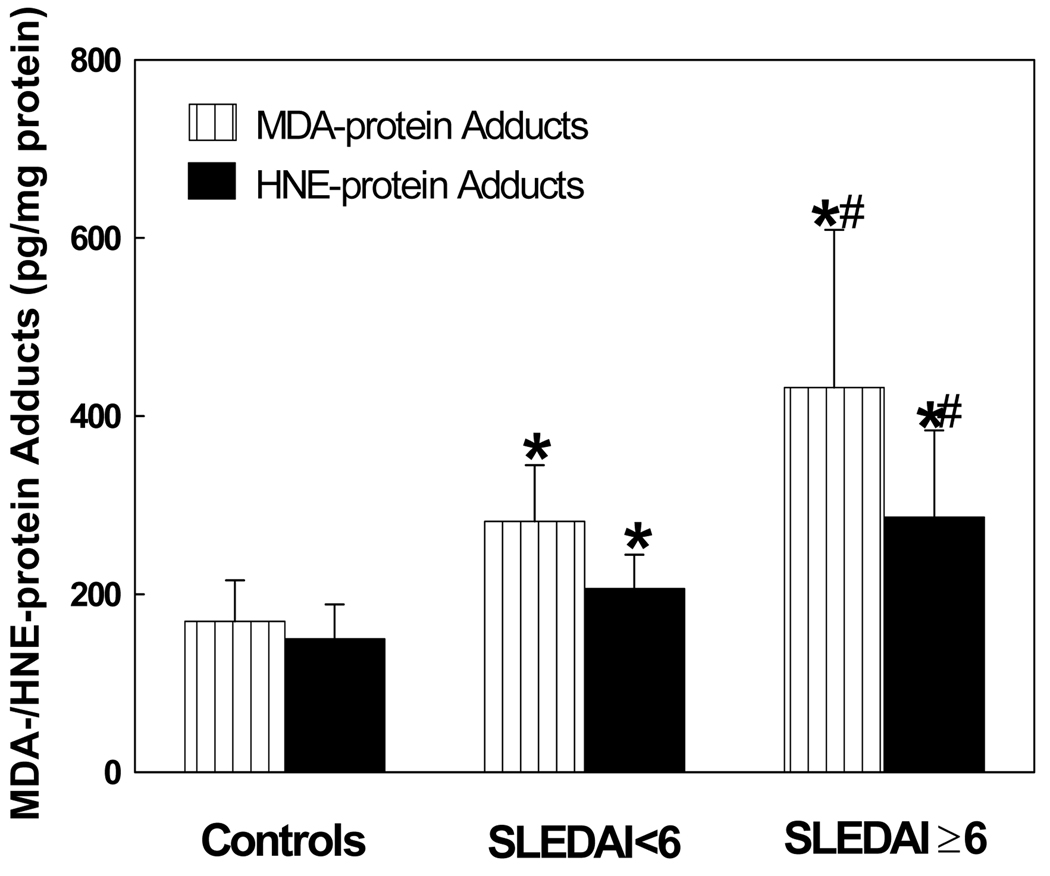

MDA- and HNE-protein adducts in the sera of SLE patients

To provide further support to our hypothesis and assess the contribution of LPDA in SLE, MDA- and HNE-protein adducts were also analyzed in the serum. As evident from Fig. 3, the levels of MDA- and HNE-protein adducts in SLE patients (in both SLEDAI < 6 and SLEDAI ≥ 6 groups) were significantly higher than controls. Remarkably, increases in the MDA- and HNE-protein adducts in the patients with SLEDAI ≥ 6 were greater in comparison to the patients with SLEDAI < 6, suggesting a positive association between the increased LPDAs and SLE disease activity. Interestingly, there was also a significant correlation between the formation of MDA-protein adducts and anti-MDA-protein antibodies (r = 0.682, p < 0.01), and HNE-protein adducts and anti-HNE-protein antibodies (r = 0.546, p < 0.01).

Figure 3.

MDA-protein adducts and HNE-protein adducts in the sera of SLE patients with SLEDAI < 6 (n=28) and SLEDAI ≥ 6 (n=44) vs. controls (n=36). The results are means ± SD. * p < 0.05 vs. controls; # p < 0.05 vs. SLEDAI < 6.

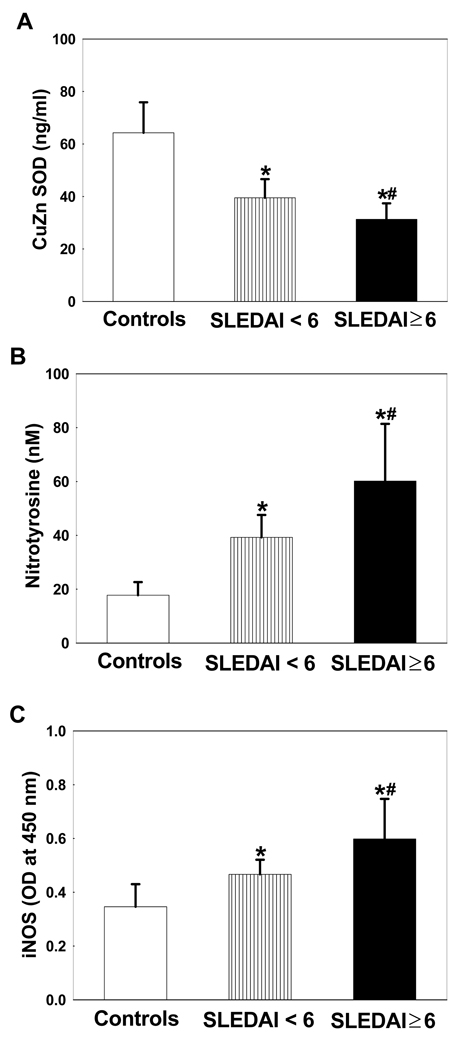

Cu/Zn SOD levels in the serum of SLE patients

In an attempt to understand the state of oxidative stress, we evaluated the serum levels of superoxide dismutase (SOD), an antioxidant enzyme. There was a significant decrease in SOD levels in the SLE patients, both with SLEDAI < 6 and SLEDAI ≥ 6, compared to the controls. Interestingly, even lower SOD activity was found in the SLE patients with SLEDAI ≥ 6 compared to the SLE patients with SLEDAI < 6 (Fig. 4A). The decreases in serum Cu/Zn SOD levels suggest a compromised antioxidant balance.

Figure 4.

CuZn SOD (A), nitrotyrosine (B) and iNOS (C) levels in the sera of SLE patients with SLEDAI < 6 (n=28) and SLEDAI ≥ 6 (n=44) vs. controls (n=36). Values are means ± SD. * p < 0.05 vs. controls; # p < 0.05 vs. SLEDAI < 6.

Nitrotyrosine and iNOS levels in the serum

Since oxidative and nitrosative stress could occur simultaneously, we assessed the potential role for nitrosative stress in SLE by measuring the serum levels of nitrotyrosine and iNOS in SLE patients and controls. As evident from Fig. 4B, NT formation was significantly higher in the SLE patients, both in SLEDAI < 6 and SLEDAI ≥ 6 groups, in comparison to the controls. However, the increases in NT levels were much greater in the SLEDAI ≥ 6 group and also significantly higher than the SLEDAI <6 group. Similarly, the iNOS protein expression was also significantly higher in the sera of SLE patients in comparison to the controls (Fig. 4C). More importantly, when the two SLE patient groups were compared, the increases in iNOS expression were much higher in the SLE patients with SLEDAI ≥ 6 in comparison to patients with SLEDAI < 6 (p<0.05, Fig. 4C).

DISCUSSION

SLE is a potentially fatal chronic autoimmune disease characterized by increased production of autoantibodies, but the initial immunizing antigens that drive the development of SLE are largely unknown. MDA and HNE, two major LPDAs, have extensively been used as the biomarkers of oxidative stress (5,19,37,39,41,42). These LPDAs are highly reactive and can form adducts with proteins, making them highly immunogenic (3,36,37,43,44). Increased formation and subsequent accumulation of such aldehyde-modified protein adducts were found in various pathological states including ADs like SLE and arthritis (3,9,12,19,45). To validate our central hypothesis that initiation of autoimmunity may be mediated by increased formation of MDA/HNE-modified protein adducts following excessive ROS generation and oxidative stress, anti-MDA- and HNE-protein adduct antibodies were quantitated in the serum of SLE patients vs. age- and gender-matched control subjects. Our results show significantly increased prevalence of both MDA-/HNE-protein adducts and their antibodies in SLE patients. Increased prevalence of these LPDAs and their antibodies in SLE patients not only suggest an increased lipid peroxidation, but also a potential role of lipid peroxidation in the pathogenesis and/or progression of SLE.

Increased lipid peroxidation has previously been detected in SLE, but the significance of lipid peroxidation in the initiation and development of SLE remains largely unexplored. In this study, when the SLE patients were divided into two groups based on their SLEDAI (<6 and ≥ 6), both groups showed higher serum MDA-/HNE-protein adducts and anti-LPDA-protein antibodies than the controls, but the levels were much greater in the high SLEDAI (≥ 6) group, suggesting an ongoing involvement of lipid peroxidation in SLE. In addition, significant increases in the number and percentage of anti-MDA-/HNE-protein adduct antibody-positive samples, and even greater increases in the high SLEDAI (≥ 6) group, indicate a close association between the serum anti-MDA-/anti-HNE-protein antibodies and SLEDAI. A highly positive correlation between serum anti-MDA-/anti-HNE-protein adduct antibodies and SLEDAI observed in the current study further suggests a strong association among lipid peroxidation, formation of MDA/HNE-protein antibodies and SLE disease activity, i.e. the greater the oxidative stress, the higher the SLEDAI. These results apart from linking lipid peroxidation with SLE disease pathogenesis, suggest that these antibodies could also be valuable in evaluating the progression of the disease. Therefore, further characterization of the biological consequence of the production of these antibodies is important and deserves attention.

Human cells have both enzymatic and non-enzymatic antioxidant defense systems. SOD, a major enzyme and first line of defense against oxygen-derived free radicals, controls ROS production by catalyzing the dismutation of the O2˙− into hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) which is further converted into water by catalase, and thereby maintaining an appropriate cellular redox balance. Alterations of this normal balance as a result of elevated ROS production and/or decreased antioxidant levels lead to a state of oxidative stress (10,11). The enhanced lipid peroxidation in SLE patients observed in this study drew our attention in evaluating the SOD levels in these subjects. Clearly, SOD levels were significantly lower in the SLE patients, with SLEDAI ≥ 6 group showing much reduced levels compared to the controls as well as SLEDAI < 6 group. The decreased serum Cu/Zn SOD suggests a compromised antioxidant balance, which may lead to increased ROS levels and, thus, contribute to increased oxidative stress.

Nitrotyrosine, a modification product of ONOO−, in generally considered a biochemical marker for peroxynitrite and/or nitric oxide production, and elevated level of NT has been found in ADs (29,46,47). Moreover, ONOO− -modified proteins may trigger an immunogenic response to these self antigens, leading to a break in immune tolerance (2,3,25,46). The current study demonstrated that the NT formation in the serum was significantly increased in patients of both SLEDAI groups. More importantly, the increases were much greater in patients with SLEDAI ≥ 6 and also significantly higher than SLEDAI < 6. These findings indicate that the formation of nitrated proteins is increased in SLE and is associated with increased SLE disease activity. Increased formation of nitrated protein, thus, presents another important potential mechanism in the pathogenesis of SLE. Furthermore, excessive ˙NO production as a result of activation of iNOS, is assumed to contribute to SLE and other ADs mainly via reaction with superoxide to form ONOO− (22,23,32,48,49). There is growing evidence that overexpression of iNOS is associated with the development and progression of ADs in experimental animals (22,23,27). Increased levels of iNOS observed in SLE patients together with significant increases in NT formation in this study provide further evidence for the involvement of nitrosative stress in SLE.

In conclusion, our results clearly show significant increases in oxidative/nitrosative stress in SLE patients, suggesting an imbalance between RONS production and antioxidant defense mechanisms in SLE. The increased formation of antibodies to LPDAs and greater NT levels observed in this study also suggest that oxidative modification of endogenous proteins due to MDA, HNE or ONOO− could elicit an autoimmune response by stimulating T and/or B lymphocytes. More importantly, the results of this study, for the first time, provide an evidence for a strong association between serum anti-MDA- and anti-HNE-protein adduct antibodies and SLE disease activity, suggesting that oxidative/nitrosative stress markers may be useful in evaluating SLE disease activity and thus, progression of the disease. Longitudial studies in SLE patients are necessary to further establish the role of oxidative/nitrosative stress as a contributing pathogenic mechanism in SLE, and to assess the usefulness of anti-MDA-/anti-HNE-protein adduct antibodies in evaluating progression and severity of the disease, as well as in developing an effective therapy for SLE.

AKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by Grant ES016302 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS), NIH, and its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIEHS, NIH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Danchenko N, Satia JA, Anthony MS. Epidemiology of systemic lupus erythematosus: a comparison of worldwide disease burden. Lupus. 2006;15:308–318. doi: 10.1191/0961203306lu2305xx. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurien BT, Hensley K, Bachmann M, Scofield RH. Oxidatively modified autoantigens in autoimmune diseases. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;41:549–556. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2006.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kurien BT, Scofield RH. Autoimmunity and oxidatively modified autoantigens. Autoimmun Rev. 2008;7:567–573. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2008.04.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frostegard J, Svenungsson E, Wu R, Gunnarsson I, Lundberg IE, Klareskog L, et al. Lipid peroxidation is enhanced in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and is associated with arterial and renal disease manifestations. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:192–200. doi: 10.1002/art.20780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khan MF, Wu X, Ansari GA. Anti-malondialdehyde antibodies in MRL+/+ mice treated with trichloroethene and dichloroacetyl chloride: possible role of lipid peroxidation in autoimmunity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2001;170:88–92. doi: 10.1006/taap.2000.9086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang G, Cai P, Ansari GA, Khan MF. Oxidative and nitrosative stress in trichloroethene-mediated autoimmune response. Toxicology. 2007;229:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2006.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang G, König R, Ansari GAS, Khan MF. Lipid peroxidation-derived aldehyde-protein adducts contribute to trichloroethene-mediated autoimmunity via activation of CD4+ T cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:1475–1482. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wang G, Wang J, Ma H, Khan MF. Increased nitration and carbonylation of proteins in MRL+/+ mice exposed to trichloroethene: potential role of protein oxidation in autoimmunity. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2009;237:188–195. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shacter E. Quantification and significance of protein oxidation in biological samples. Drug Metab Rev. 2000;32:307–326. doi: 10.1081/dmr-100102336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Grimsrud PA, Xie H, Griffin TJ, Bernlohr DA. Oxidative stress and covalent modification of protein with bioactive aldehydes. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:21837–21841. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R700019200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ozkan Y, Yardým-Akaydýn S, Sepici A, Keskin E, Sepici V, Simsek B. Oxidative status in rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 2007;26:64–68. doi: 10.1007/s10067-006-0244-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grune T, Michel P, Sitte N, Eggert W, Albrecht-Nebe H, Esterbauer H, et al. Increased levels of 4-hydroxynonenal modified proteins in plasma of children with autoimmune diseases. Free Radic Biol Med. 1997;23:357–360. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00586-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khan MF, Wu X, Ansari GA, Boor PJ. Malondialdehyde-protein adducts in the spleens of aniline-treated rats: immunochemical detection and localization. J Toxicol Environ Health Part A. 2003;66:93–102. doi: 10.1080/15287390306464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kamanli A, Naziroglu M, Aydilek N, Hacievliyagil C. Plasma lipid peroxidation and antioxidant levels in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Cell Biochem Funct. 2004;22:53–57. doi: 10.1002/cbf.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Januszewski AS, Alderson NL, Jenkins AJ, Thorpe SR, Baynes JW. Chemical modification of proteins during peroxidation of phospholipids. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:1440–1449. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400442-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nuttall SL, Heaton S, Piper MK, Martin U, Gordon C. Cardiovascular risk in systemic lupus erythematosus--evidence of increased oxidative stress and dyslipidaemia. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2003;42:758–762. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keg212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Matsuura E, Lopez LR. Autoimmune-mediated atherothrombosis. Lupus. 2008;17:878–887. doi: 10.1177/0961203308093553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan PE, Sturgess AD, Davies MJ. Evidence for chronically elevated serum protein oxidation in systemic lupus erythematosus patients. Free Radic Res. 2009;43:117–127. doi: 10.1080/10715760802623896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kurien BT, Scofield RH. Free radical mediated peroxidative damage in systemic lupus erythematosus. Life Sci. 2003;73:1655–1666. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(03)00475-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sampey BP, Korourian S, Ronis MJ, Badger TM, Petersen DR. Immunohistochemical characterization of hepatic malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal modified proteins during early stages of ethanol-induced liver injury. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27:1015–1022. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000071928.16732.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ramakrishna V, Jailkhani R. Oxidative stress in non-insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus (NIDDM) patients. Acta Diabetol. 2008;45:41–46. doi: 10.1007/s00592-007-0018-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weinberg JB, Granger DL, Pisetsky DS, Seldin MF, Misukonis MA, Mason SN, et al. The role of nitric oxide in the pathogenesis of spontaneous murine autoimmune disease: increased nitric oxide production and nitric oxide synthase expression in MRL-lpr/lpr mice, and reduction of spontaneous glomerulonephritis and arthritis by orally administered NG-monomethyl-L-arginine. J Exp Med. 1994;179:651–660. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.2.651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xia Y, Zweier JL. Superoxide and peroxynitrite generation from inducible nitric oxide synthase in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:6954–6958. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.13.6954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khan MF, Wu X, Kaphalia BS, Boor PJ, Ansari GA. Nitrotyrosine formation in splenic toxicity of aniline. Toxicology. 2003;194:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2003.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ohmori H, Kanayama N. Immunogenicity of an inflammation-associated product, tyrosine nitrated self-proteins. Autoimmun Rev. 2005;4:224–229. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2004.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Habib S, Moinuddin, Ali R. Peroxynitrite-modified DNA: a better antigen for systemic lupus erythematosus anti-DNA autoantibodies. Biotech Appl Biochem. 2006;43:65–70. doi: 10.1042/BA20050156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karpuzoglu E, Ahmed SA. Estrogen regulation of nitric oxide and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) in immune cells: implications for immunity, autoimmune diseases, and apoptosis. Nitric Oxide. 2006;15:177–186. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2006.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Morgan PE, Sturgess AD, Davies MJ. Increased levels of serum protein oxidation and correlation with disease activity in systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:2069–2079. doi: 10.1002/art.21130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Khan F, Siddiqui AA, Ali R. Measurement and significance of 3-nitrotyrosine in systemic lupus erythematosus. Scand J Immunol. 2006;64:507–514. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2006.01794.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Belmont HM, Levartovsky D, Goel A, Amin A, Giorno R, Rediske J, et al. Increased nitric oxide production accompanied by the up-regulation of inducible nitric oxide synthase in vascular endothelium from patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1810–1816. doi: 10.1002/art.1780401013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wanchu A, Khullar M, Deodhar SD, Bambery P, Sud A. Nitric oxide synthesis is increased in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol Int. 1998;18:41–43. doi: 10.1007/s002960050055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nagy G, Clark JM, Buzás EI, Gorman CL, Cope AP. Nitric oxide, chronic inflammation and autoimmunity. Immunol Lett. 2007;111:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hochberg MC. Updating the American College of Rheumatology revised criteria for the classification of systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 1997;40:1725. doi: 10.1002/art.1780400928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bombardier C, Gladman DD, Urowitz MB, Caron D, Chang CH. Derivation of the SLEDAI. A disease activity index for lupus patients. The Committee on Prognosis Studies in SLE. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:630–640. doi: 10.1002/art.1780350606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urquizu-Padilla M, Balada E, Cortés F, Pérez EH, Vilardell-Tarrés M, Ordi-Ros J. Serum levels of soluble CD40 ligand at flare and at remission in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol. 2009;36:953–960. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.080978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan MF, Wu X, Kaphalia BS, Boor PJ, Ansari GA. Acute hematopoietic toxicity of aniline in rats. Toxicol Lett. 1997;92:31–37. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4274(97)00032-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Khan MF, Wu X, Tipnis UR, Ansari GA, Boor PJ. Protein adducts of malondialdehyde and 4-hydroxynonenal in livers of iron loaded rats: quantitation and localization. Toxicology. 2002;173:193–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang G, Ansari GA, Khan MF. Involvement of lipid peroxidation-derived aldehyde-protein adducts in autoimmunity mediated by trichloroethene. J Toxicol Environ Health A. 2007;70:1977–1985. doi: 10.1080/15287390701550888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Uchida K, Szweda LI, Chae HZ, Stadtman ER. Immunochemical detection of 4-hydroxynonenal protein adducts in oxidized hepatocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8742–8746. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Esterbauer H, Schaur RJ, Zollner H. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;11:81–128. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tuma DJ. Role of malondialdehyde-acetaldehyde adducts in liver injury. Free Radic Biol Med. 2002;32:303–308. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(01)00742-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Devaraj S, Leonard S, Traber MG, Jialal I. Gamma-tocopherol supplementation alone and in combination with alpha-tocopherol alters biomarkers of oxidative stress and inflammation in subjects with metabolic syndrome. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008;44:1203–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.12.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fenaille F, Tabet JC, Guy PA. Identification of 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal-modified peptides within unfractionated digests using matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Anal Chem. 2004;76:867–873. doi: 10.1021/ac0303822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Toyoda K, Nagae R, Akagawa M, Ishino K, Shibata T, Ito S, et al. Protein-bound 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal: an endogenous triggering antigen of anti-DNA response. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:25769–25778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703039200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Iborra A, Palacio JR, Martinez P. Oxidative stress and autoimmune response in the infertile woman. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2005;88:150–162. doi: 10.1159/000087832. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Khan F, Ali R. Antibodies against nitric oxide damaged poly L-tyrosine and 3-nitrotyrosine levels in systemic lupus erythematosus. J Biochem Mol Biol. 2006;39:189–196. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2006.39.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nemirovskiy OV, Radabaugh MR, Aggarwal P, Funckes-Shippy CL, Mnich SJ, Meyer DM, et al. Plasma 3-nitrotyrosine is a biomarker in animal models of arthritis: Pharmacological dissection of iNOS' role in disease. Nitric Oxide. 2009;20:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.niox.2008.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Djordjevic VB, Stanković T, Cosić V, Zvezdanović L, Kamenov B, Tasić-Dimov D, et al. Immune system-mediated endothelial damage is associated with NO and antioxidant system disorders. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2004;42:1117–1121. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2004.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cuzzocrea S. Role of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen species in arthritis. Curr Pharm Des. 2006;12:3551–3570. doi: 10.2174/138161206778343082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]