Abstract

The worldwide increase in fluoroquinolone-resistant and extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae pathogens has led to doripenem and other carbapenems assuming a greater role in the treatment of serious infections. We analyzed data from 6 phase 3 multinational doripenem clinical trials on ciprofloxacin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates consisting of all genera (CIPRE) and ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates consisting of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., and Proteus spp. with ceftazidime MICs of ≥2 μg/ml (ESBLE) for prevalence by geographic region and disease type, in vitro activities of doripenem and comparator agents, and clinical or microbiologic outcomes in doripenem- and comparator-treated patients across disease types (complicated intra-abdominal infection [cIAI], complicated urinary tract infection [cUTI], and nosocomial pneumonia [NP]). Of 1,830 baseline Enterobacteriaceae isolates, 88 (4.8%) were ESBLE and 238 (13.0%) were CIPRE. The incidence of ESBLE was greatest in Europe (7.8%); that of CIPRE was higher in South America (15.9%) and Europe (14.4%). ESBLE incidence was highest in NP (12.9%) cases; that of CIPRE was higher in cUTI (18.3%) and NP (14.9%) cases. Against ESBLE and CIPRE, carbapenems appeared more active than other antibiotic classes. Among carbapenems, doripenem and meropenem were most potent. Doripenem had low MIC90s for CIPRE (0.5 μg/ml) and ESBLE (0.25 μg/ml). Doripenem and comparators were highly clinically effective in infections caused by Enterobacteriaceae, irrespective of their ESBL statuses. The overall cure rates were the same for doripenem (82%; 564/685) and the comparators (82%; 535/652) and similar for ESBLE (73% [16/22] versus 72% [21/29]) and CIPRE (68% [47/69] versus 52% [33/64]). These findings indicate that doripenem is an important therapeutic option for treating serious infections caused by ESBLE and CIPRE.

Antibacterial agents of the carbapenem class are assuming a greater role in the treatment of serious infections, due in part to the worldwide increases in the prevalences of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates (ESBLE) and fluoroquinolone-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates, including ciprofloxacin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates (CIPRE). Carbapenems are an important therapeutic option for treating serious infections due to ESBLE and CIPRE, including intra-abdominal infections, urinary tract infections, and pneumonia, because of their broad spectrum of activity and their stability in the presence of a wide range of β-lactamases (3, 9).

Doripenem, a new parenteral carbapenem, has been recognized as a valuable addition to the currently available carbapenems in the treatment of serious bacterial infections (3, 4, 9, 15). Doripenem has a broad spectrum of in vitro activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria, including ESBLE and anaerobic pathogens (6). It has a low propensity for selection for resistance and is stable in solution, which provides an option for administration as a prolonged infusion that enhances achievable pharmacodynamic/pharmacokinetic targets for bactericidal activity (and therefore presumed efficacy) against more resistant pathogens (4, 8). Doripenem has been approved for use in the United States and Europe for the treatment of adults with complicated urinary tract infections (cUTIs), including pyelonephritis, and for the treatment of complicated intra-abdominal infections (cIAIs). It has also been approved in Europe for the treatment of nosocomial pneumonia (NP), including ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP).

Recent studies evaluated the in vitro activities of doripenem and comparators against clinical isolates, including resistant phenotypes, collected at multiple medical centers (6, 10). A study examined the in vitro activities against 12,581 clinical isolates collected in the United States between 2005 and 2006. Overall, the potency of doripenem was equal or superior in activity to the potency of other carbapenems (imipenem and meropenem) against Enterobacteriaceae, including β-lactam-nonsusceptible isolates (10). Another study evaluated the in vitro potency against 36,614 isolates collected worldwide between 2000 and 2007. The results confirm previous reports showing that the activity of doripenem is similar to that of meropenem and superior to that of imipenem against Enterobacteriaceae (including ESBL-producing and stably derepressed AmpC producers) (6).

Although carbapenems demonstrate good in vitro activity against β-lactamase-producing organisms, evidence of clinical efficacy of carbapenem therapy for infections caused by ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae is needed (12). Pitout and Laupland reviewed antimicrobial therapy of ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae infections and identified only 10 studies that had specific outcome details for ESBL-producing organisms. These studies reported outcomes for carbapenems and other antimicrobial agents to which the organism was susceptible in vitro; the majority of infections were bacteremias, and data were available for only a small number of subjects (12).

The doripenem clinical development program represents a broad worldwide clinical and microbiologic experience for subjects treated with doripenem and comparator agents for several indications in adults. We analyzed data on ESBLE and CIPRE from 6 large phase 3 multinational doripenem clinical trials with respect to (i) their prevalences by geographic region and by treatment indication, (ii) the in vitro activities of doripenem and comparator agents against these isolates, and (iii) the clinical or microbiologic outcomes obtained with doripenem or a comparator agent for infections caused by these isolates across several treatment indications: cIAI, cUTI (including pyelonephritis), and NP (including VAP).

(Some of the data in this study were presented at the 47th Interscience Conference on Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy, 17 to 20 September 2007, Chicago, IL.)

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Studies providing data.

Data were collected from 6 large phase 3 doripenem clinical studies that included a baseline screening visit, a treatment phase, a test-of-cure (TOC) visit occurring 7 to 14 days after the last dose of study drug therapy, and a follow-up visit. The subjects were 18 years or older, with signs and symptoms of the treatment indication. Approval was obtained from an institutional review board or ethics committee, and subjects provided informed consent to participate. All studies enrolled subjects from North America, South America, and Europe; the DORI-10 study also enrolled subjects from Australia and South Africa.

Subjects with cUTI were treated intravenously with 500 mg of doripenem infused over 1 h every 8 h (Doribax; manufactured by Shionogi & Co., Ltd., Osaka, Japan, and distributed by Ortho-McNeil Pharmaceutical, Inc., Raritan, NJ) in a randomized, double-blind, multicenter, levofloxacin-controlled study (DORI-05; n = 748) (7) and in a single-arm, multicenter study (DORI-06; n = 423). Levofloxacin (250 mg) was administered once daily intravenously (n = 372). Subjects with cIAI were treated with 500 mg of doripenem infused over 1 h every 8 h in two multicenter, randomized, double-blind, meropenem-controlled studies (DORI-07 [n = 471] and DORI-08 [n = 486]) (5). Meropenem was administered at 1 g every 8 h intravenously (n = 469). Subjects with NP, including early-onset VAP, were treated intravenously with 500 mg of doripenem infused over 1 h every 8 h in a randomized, multicenter, open-label, piperacillin-tazobactam-controlled study (DORI-09; n = 444) (14). Piperacillin-tazobactam (4.5 g) was administered intravenously every 6 h (n = 221). Additionally, subjects with VAP (DORI-10; n = 525), including both early- and late-onset cases, were treated with the same dose (500 mg) of doripenem (n = 262), administered as a 4-hour infusion every 8 h in a randomized, multicenter, open label, imipenem-controlled study (1). Imipenem-cilastatin (n = 263) was administered at 500 mg every 6 h or 1,000 mg every 8 h via 30- or 60-min intravenous infusions, respectively, as the control treatment.

Organism collection and susceptibility test methods.

Clean-catch urine specimens, intraoperative intra-abdominal specimens, and sputum specimens or other suitable specimens of lower respiratory tract secretions (including tracheal aspirates and bronchoscopically obtained secretions) were obtained at screening from all subjects with cUTI, cIAI, and NP, respectively. When appropriate, specimens were also collected at prespecified postbaseline visits according to the protocol. Specimens were sent to the local laboratory or regional laboratory for Gram staining, culture, and bacterial identification using the local laboratory's usual procedures. All cultured pathogens were then sent to a central laboratory for identification using the central laboratory's standard operating procedure and susceptibility testing.

A total of 1,830 baseline Enterobacteriaceae isolates were obtained and analyzed. All strains were tested by broth microdilution methods against doripenem and a variety of antimicrobial agents. MICs were determined using Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) broth microdilution methods (2). ESBLE were defined as isolates of Escherichia coli, Klebsiella spp., and Proteus spp. with ceftazidime MICs of ≥2 μg/ml. CIPRE were defined as isolates of any Enterobacteriaceae genera with ciprofloxacin MICs of ≥4 μg/ml. The primary purpose of susceptibility testing at the central laboratory was to provide consistent standardized CLSI-based susceptibility data.

Statistical analysis.

The incidences of ESBLE and CIPRE in baseline Enterobacteriaceae isolates were calculated for the main geographic regions (North America, South America, Europe, and other countries [Australia and South Africa]) and by treatment indication (cUTI, cIAI, and NP). The in vitro activities of doripenem and comparator antimicrobial agents tested against baseline Enterobacteriaceae isolates were computed, and the MIC distributions of baseline ESBLE and CIPRE were summarized for doripenem and comparators.

The clinical or microbiologic outcomes observed at TOC visits were evaluated in the 5 comparator-controlled studies for all Enterobacteriaceae isolates and for ESBLE and CIPRE. Separate analyses were conducted in the microbiologically modified intent-to-treat (mMITT) population and the microbiologically evaluable at TOC visit (METOC) population. The mMITT population included all randomized subjects who met the protocol definition of the infection under study, received at least one dose of the study drug, and had at least one bacterial pathogen identified at the baseline, regardless of its susceptibility to study drug therapies. The METOC population included all randomized subjects who met the protocol definition of the infection, received at least one dose of the study drug, were compliant with study drug therapy, had sufficient data available for determination of clinical outcome (microbiologic outcome for UTI) at the TOC visit without any confounding factors that would interfere with the outcome assessment, and had at least 1 baseline bacterial pathogen identified that was susceptible to the intravenous study drug therapy received. An expanded population (EMETOC) that included all subjects in the METOC population and those subjects who were excluded from the METOC analysis set only because of a resistant baseline pathogen for cIAI and NP was used. For patients with cUTI, the baseline pathogen was not required to be susceptible to either study drug, given the high concentrations of both doripenem and levofloxacin that are achieved in the urine.

The difference between doripenem and the comparator in the clinical or microbiologic outcome was assessed using a 2-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) using the normal approximation to the difference of two binomial proportions with continuity correction.

RESULTS

Prevalences of ESBLE and CIPRE.

A total of 1,830 baseline Enterobacteriaceae isolates were obtained and analyzed; 88 (4.8%) were ESBLE and 238 (13.0%) were CIPRE. Among the 88 ESBLE, 68.2% were also CIPRE.

The prevalences of ESBLE and CIPRE by geographic region and treatment indication are presented in Table 1. The geographic distribution of the 1,830 baseline Enterobacteriaceae isolates was as follows: 23.1% in North America, 44.2% in South America, 30.8% in Europe, and 1.9% in other countries. The relative incidence of ESBLE was highest in Europe (7.8%), and the CIPRE incidences were higher in South America (15.9%) and Europe (14.4%). The treatment indication with the highest incidence of ESBLE was NP (12.9%). The incidence of CIPRE was higher in subjects treated for cUTI (18.3%) or NP (14.9%).

TABLE 1.

Prevalences of baseline Enterobacteriaceae isolates by geographic region and treatment indication

| Characteristica | Value for: |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Geographic region |

Treatment indicationc |

||||||

| North America | South America | Europe | Otherb | cUTI | cIAI | NP | |

| No. of Enterobacteriaceae isolates | 422 | 810 | 564 | 34 | 863 | 658 | 309 |

| No. of ESBLE | 13 | 31 | 44 | 0 | 32 | 16 | 40 |

| ESBLE incidence (%) | 3.1 | 3.8 | 7.8 | 0 | 3.7 | 2.4 | 12.9 |

| No. of CIPRE | 28 | 129 | 81 | 0 | 158 | 34 | 46 |

| CIPRE incidence (%) | 6.6 | 15.9 | 14.4 | 0 | 18.3 | 5.2 | 14.9 |

ESBLE, extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates, including isolates of E. coli, Klebsiella spp., and Proteus spp., with ceftazidime MICs of ≥2 μg/ml; CIPRE, Enterobacteriaceae isolates with ciprofloxacin MICs of ≥4 μg/ml.

Includes Australia (29 isolates) and South Africa (5 isolates).

cUTI, complicated urinary tract infection; cIAI, complicated intra-abdominal infection; NP, nosocomial pneumonia.

In vitro activities against ESBLE and CIPRE.

The in vitro activities of doripenem and other antimicrobial agents tested against all baseline Enterobacteriaceae isolates, ESBLE, and CIPRE are indicated in Table 2. The lowest MIC90 values among Enterobacteriaceae overall were for doripenem, meropenem, ertapenem, and ceftazidime. For ESBLE and CIPRE, doripenem and meropenem had the lowest MIC50 (≤0.06 μg/ml) and MIC90 (≤0.25 μg/ml) values among all agents tested. Similarly, doripenem and meropenem had the lowest MIC50 (≤0.03 μg/ml) and MIC90 (≤0.5 μg/ml) values among CIPRE.

TABLE 2.

In vitro activities of doripenem and other antimicrobial agents tested against baseline Enterobacteriaceae isolates

| Organism groupa | Antibacterial agent | N | MIC (μg/ml) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Range | MIC50 | MIC90 | |||

| All Enterobacteriaceae | Doripenem | 1,830 | ≤0.03-32b | ≤0.03 | 0.12 |

| Imipenem | 1,830 | ≤0.03-32b | 0.12 | 1 | |

| Meropenem | 1,830 | ≤0.03-64b | ≤0.03 | 0.06 | |

| Ertapenem | 1,830 | ≤0.03->32b | ≤0.03 | ≤0.03 | |

| Levofloxacin | 1,830 | ≤0.03->512 | ≤0.03 | 8 | |

| Ceftazidime | 1,830 | ≤0.03->32 | 0.12 | 0.5 | |

| Amikacin | 1,830 | ≤0.25->64 | 2 | 8 | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 1,830 | ≤0.5->128 | 2 | 8 | |

| ESBLE | Doripenem | 88 | ≤0.03-32 | 0.06 | 0.25 |

| Imipenem | 88 | 0.06-32 | 0.12 | 0.5 | |

| Meropenem | 88 | ≤0.03-64 | ≤0.03 | 0.12 | |

| Ertapenem | 88 | ≤0.03->32 | 0.12 | 1 | |

| Levofloxacin | 88 | ≤0.03-256 | 8 | 32 | |

| Ceftazidime | 88 | 2->32 | 32 | >32 | |

| Amikacin | 88 | 0.5->64 | 8 | >64 | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 88 | 1->128 | 64 | >128 | |

| CIPRE | Doripenem | 238 | ≤0.03-32 | 0.03 | 0.5 |

| Imipenem | 238 | 0.06-32 | 0.12 | 1 | |

| Meropenem | 238 | ≤0.03-64 | 0.03 | 0.25 | |

| Ertapenem | 238 | ≤0.03->32 | ≤0.03 | 4 | |

| Levofloxacin | 238 | 1->512 | 16 | 64 | |

| Ceftazidime | 238 | ≤0.03->32 | 1 | >32 | |

| Amikacin | 238 | ≤0.25->64 | 4 | >64 | |

| Piperacillin-tazobactam | 238 | ≤0.5->128 | 4 | >128 | |

ESBLE, extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates, including isolates of E. coli, Klebsiella spp., and Proteus spp., with ceftazidime MICs of ≥2 μg/ml; CIPRE, Enterobacteriaceae isolates with ciprofloxacin MICs of ≥4 μg/ml.

A single Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate, a putative Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) producer, showed resistance to all carbapenems, with MICs of ≥32 μg/ml, and was also resistant to all comparators tested.

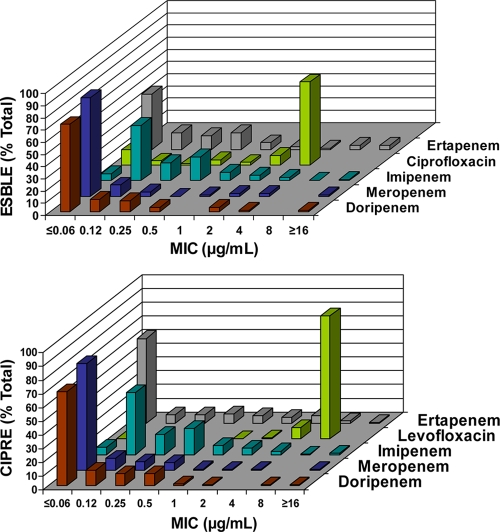

The MIC distribution of ESBLE and CIPRE for doripenem and comparator agents is presented in Fig. 1. Among ESBLE, 68% had ciprofloxacin MICs of ≥4 μg/ml but only 2% had doripenem MICs of >2 μg/ml (top panel). Among CIPRE, 99% had carbapenem MICs of ≤4 μg/ml.

FIG. 1.

MIC distributions of ESBLE (top panel) and CIPRE (bottom panel) for doripenem and comparator agents. ESBLE, extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates; CIPRE, ciprofloxacin-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates.

Clinical or microbiologic outcome observed at the TOC visit.

In the 5 comparative studies, the clinical or microbiologic outcomes observed at TOC visits for doripenem and the comparator agent were determined for all infections associated with Enterobacteriaceae isolates and subgroups with ESBLE and CIPRE organisms by use of the METOC/EMETOC population (Table 3) and the mMITT population (Table 4). The mMITT population included more subjects and consistently showed a slightly lower cure rate than the METOC/EMETOC population, as would be expected given the difference in the criteria for including subjects (e.g., susceptibility to study drug therapies, severity of disease and other clinical conditions, and presumption of failure when outcome data were missing). The overall patterns of results were similar for both analysis sets, and therefore, the review of findings below focuses on the METOC/EMETOC population.

TABLE 3.

Favorable outcomes observed at TOC visits for ESBLE and CIPRE for doripenem and comparators (METOC/EMETOC analysis)a

| Study(ies) or organism groupc | Doripenem |

Comparatorb |

Diff | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n | % | N | n | % | |||

| All studies with comparator | ||||||||

| All Enterobacteriaceae isolates | 685 | 564 | 82.3 | 652 | 535 | 82.1 | 0.3 | −4.0-4.5 |

| ESBLE | 22 | 16 | 72.7 | 29 | 21 | 72.4 | 0.3 | −28.4-29.0 |

| CIPRE | 69 | 47 | 68.1 | 64 | 33 | 51.6 | 16.6 | −1.4-34.5 |

| DORI-05 (complicated urinary tract infection) | ||||||||

| All Enterobacteriaceae isolates | 260 | 217 | 83.5 | 254 | 217 | 85.4 | −2.0 | −8.6-4.7 |

| ESBLE | 5 | 3 | 60.0 | 5 | 1 | 20.0 | 40.0 | −35.4-100.0 |

| CIPRE | 40 | 24 | 60.0 | 32 | 7 | 21.9 | 38.1 | 14.4-61.8 |

| DORI-07 and DORI-08 (complicated intra-abdominal infection) | ||||||||

| All Enterobacteriaceae isolates | 315 | 266 | 84.4 | 274 | 233 | 85.0 | −0.6 | −6.8-5.6 |

| ESBLE | 7 | 5 | 71.4 | 5 | 5 | 100.0 | −28.6 | −79.2-22.0 |

| CIPRE | 17 | 14 | 82.4 | 12 | 11 | 91.7 | −9.3 | −40.4-21.7 |

| DORI-09 (nosocomial pneumonia) | ||||||||

| All Enterobacteriaceae isolates | 42 | 34 | 81.0 | 51 | 38 | 74.5 | 6.4 | −12.6-25.5 |

| ESBLE | 8 | 6 | 75.0 | 17 | 13 | 76.5 | −1.5 | −46.8-43.9 |

| CIPRE | 10 | 7 | 70.0 | 16 | 11 | 68.8 | 1.2 | −43.2-45.7 |

| DORI-10 (nosocomial pneumonia) | ||||||||

| All Enterobacteriaceae isolates | 68 | 47 | 69.1 | 73 | 47 | 64.4 | 4.7 | −12.2-21.7 |

| ESBLE | 2 | 2 | 100.0 | 2 | 2 | 100.0 | 0.0 | −50.0-50.0 |

| CIPRE | 2 | 2 | 100.0 | 4 | 4 | 100.0 | 0.0 | −37.5-37.5 |

Shown are clinical outcomes for complicated intra-abdominal infection and nosocomial pneumonia (EMETOC) and microbiological outcomes for complicated urinary tract infection (METOC). N, number of subjects in each treatment group; n, number cured (microbiologically or clinically); Diff, doripenem value minus comparator value; 95% CI, 2-sided 95% confidence interval using the normal approximation to the difference of two binomial proportions with continuity correction.

The comparators were levofloxacin (DORI-05), meropenem (DORI-07 and DORI-08), piperacillin-tazobactam (DORI-09), and imipenem (DORI-10).

ESBLE, extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates, including isolates of E. coli, Klebsiella spp., and Proteus spp., with ceftazidime MICs of ≥2 μg/ml; CIPRE, Enterobacteriaceae isolates with ciprofloxacin MICs of ≥4 μg/ml.

TABLE 4.

Favorable outcomes observed at TOC visits for ESBLE and CIPRE for doripenem and comparators (mMITT analysis)a

| Study(ies) or organism groupb | Doripenem |

Comparatorc |

Diff | 95% CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | n | % | N | n | % | |||

| All studies with comparator | ||||||||

| All Enterobacteriaceae isolates | 852 | 627 | 73.6 | 811 | 597 | 73.6 | −0.0 | −4.4-4.3 |

| ESBLE | 30 | 20 | 66.7 | 39 | 24 | 61.5 | 5.1 | −20.6-30.8 |

| CIPRE | 84 | 52 | 61.9 | 84 | 40 | 47.6 | 14.3 | −1.8-30.4 |

| DORI-05 (complicated urinary tract infection) | ||||||||

| All Enterobacteriaceae isolates | 304 | 226 | 74.3 | 303 | 228 | 75.2 | −0.9 | −8.1-6.3 |

| ESBLE | 6 | 3 | 50.0 | 7 | 1 | 14.3 | 35.7 | −27.4-98.9 |

| CIPRE | 45 | 24 | 53.3 | 42 | 10 | 23.8 | 29.5 | 7.8-51.3 |

| DORI-07 and DORI-08 (complicated intra-abdominal infection) | ||||||||

| All Enterobacteriaceae isolates | 374 | 289 | 77.3 | 330 | 257 | 77.9 | −0.6 | −7.1-5.9 |

| ESBLE | 8 | 6 | 75.0 | 8 | 5 | 62.5 | 12.5 | −45.0-70.0 |

| CIPRE | 18 | 15 | 83.3 | 16 | 13 | 81.3 | 2.1 | −29.6-33.7 |

| DORI-09 (nosocomial pneumonia) | ||||||||

| All Enterobacteriaceae isolates | 60 | 44 | 73.3 | 64 | 42 | 65.6 | 7.7 | −10.0-25.5 |

| ESBLE | 14 | 9 | 64.3 | 21 | 15 | 71.4 | −7.1 | −44.8-30.5 |

| CIPRE | 16 | 10 | 62.5 | 20 | 12 | 60.0 | 2.5 | −35.1-40.1 |

| DORI-10 (nosocomial pneumonia) | ||||||||

| All Enterobacteriaceae isolates | 114 | 68 | 59.6 | 114 | 70 | 61.4 | −1.8 | −15.3-11.8 |

| ESBLE | 2 | 2 | 100.0 | 3 | 3 | 100.0 | 0.0 | −41.7-41.7 |

| CIPRE | 5 | 3 | 60.0 | 6 | 5 | 83.3 | −23.3 | −93.9-47.3 |

N, number of subjects in each treatment group; n, number cured (microbiologically or clinically); Diff, doripenem value minus comparator value; 95% CI, 2-sided 95% confidence interval using the normal approximation to the difference of two binomial proportions with continuity correction.

ESBLE, extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae isolates, including isolates of E. coli, Klebsiella spp., and Proteus spp., with ceftazidime MICs of ≥2 μg/ml; CIPRE, Enterobacteriaceae isolates with ciprofloxacin MICs of ≥4 μg/ml.

The comparators were levofloxacin (DORI-05), meropenem (DORI-07 and DORI-08), piperacillin-tazobactam (DORI-09), and imipenem (DORI-10).

For all studies combined, doripenem and the comparators were effective against Enterobacteriaceae, irrespective of their ESBL statuses. For all Enterobacteriaceae isolates, the cure rates were the same for doripenem (82%; 564/685) and the comparators (82%; 535/652). For ESBLE, the cure rates were similar for doripenem (73%; 16/22) and the comparators (72%; 21/29). For CIPRE, the cure rate was greater for doripenem (68%; 47/69) than for the comparators (52% [33/64]; 95% CI, −1.4 to 34.5). These results were weighted by the larger number of CIPRE seen in cUTI.

For the treatment of cUTI (DORI-05), doripenem and the comparator (levofloxacin) were very effective against Enterobacteriaceae overall, with microbiological cure rates of 83% (217/260) and 85% (217/254), respectively. For ESBLE and CIPRE, the microbiological cure rates were numerically higher for doripenem than for the comparator (60% [3/5] versus 20% [1/5] and 60% [24/40] versus 22% [7/32], respectively), although the numbers are small and the differences are not statistically significant.

For treatment of cIAI (DORI-07 and 08), doripenem and the comparator (meropenem) were very effective against Enterobacteriaceae overall, with clinical cure rates of 84% (266/315) and 85% (233/274), respectively. The clinical cure rate rates were 71% (5/7) and 82% (14/17) for doripenem and 100% (5/5) and 92% (11/12) for the comparator for ESBLE and CIPRE, respectively. Given the small sample sizes, these differences are not statistically significant.

For subjects with NP treated with doripenem or piperacillin-tazobactam (DORI-09), the clinical cure rates were similar for the two agents across all Enterobacteriaceae isolates (81% and 74%), ESBLE (75% and 76%), and CIPRE (70% and 69%). In the other NP study, involving only subjects with ventilator-associated pneumonia (DORI-10), the clinical cure rates were similar for doripenem and imipenem for Enterobacteriaceae overall (69% and 64%), with 100% cure rates for 4 subjects with ESBLE and the 6 subjects with CIPRE.

DISCUSSION

Enterobacteriaceae, including ESBL-producing strains, are among the most important causes of serious nosocomial and community onset bacterial infections in humans. Resistance to antimicrobial agents in these species has become an increasingly relevant problem for health care providers (11, 13). The doripenem clinical development program provided substantial data on the prevalences of ESBLE and CIPRE for different geographic regions and treatment indications, the in vitro activities of doripenem and other antibacterial agents against these potentially resistant pathogens, and the clinical efficacies of doripenem and comparators in treating infections caused by these organisms.

ESBLE rates were relatively low across geographic regions in our studies, and for CIPRE, rates were twice as high in Europe and South America as they were in North America. Against ESBLE and CIPRE, carbapenems were more active in vitro than other classes of antimicrobial agents. Among the carbapenems, doripenem and meropenem were generally more potent than imipenem and ertapenem. Doripenem generally had very low MICs for ESBLE and CIPRE. The reported findings are consistent with a study showing that doripenem activity is similar to that of meropenem and superior to that of imipenem against Enterobacteriaceae (including ESBL and stably derepressed AmpC producers) (6). Furthermore, the similarity of the overall doripenem activity observed in the study and earlier reports suggests that there is no overall trend toward decreased carbapenem susceptibility.

Practical challenges exist regarding the ability of prospective randomized clinical trials to compare the efficacies of different agents for the treatment of infections caused by ESBL-producing Enterobacteriaceae, and there are only a limited number of studies reporting specific outcome details for ESBL-producing organisms treated with carbapenems. Studies have shown that carbapenem agents (doripenem, meropenem, and imipenem) are very effective against Enterobacteriaceae, irrespective of their ESBL statuses. In this report, data combined across the applicable studies (DORI-07, DORI-08, and DORI-10) show that the overall clinical cure rates observed at TOC visits were similar between doripenem and the comparators, meropenem and imipenem, for all Enterobacteriaceae isolates (81% and 74%, respectively), ESBLE (75% and 76%, respectively), and CIPRE (70% and 69%, respectively). For treatment of cUTI, doripenem and levofloxacin were very effective against Enterobacteriaceae overall. However, cure rates were higher for doripenem for ESBL and CIPRE, suggesting that as fluoroquinolone resistance increases, doripenem may become a more important option for successful treatment of cUTIs (7).

The reported findings support the view that doripenem is an important therapeutic option for treating serious infections, such as cIAI, cUTI, and NP, caused by ESBLE and CIPRE. Other considerations favoring doripenem as a viable alternative for broad-spectrum coverage of common Enterobacteriaceae pathogens include its longer duration of stability in solution, providing an option to administer it as an extended (4-h) infusion to target pathogens with higher MICs, and its lower propensity for inducing seizures than the levels obtained with other carbapenems (1, 5).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC. Each of us is now or was an employee of Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development. The 6 doripenem clinical phase 3 studies providing data for the manuscript are registered at http://www.clinicaltrials.gov/: DORI-05 (NCT00229021), DORI-06 (NCT00210990), DORI-07 (NCT00210938), DORI-08 (NCT00229060), DORI-09 (NCT00211003), and DORI-10 (NCT00211016).

We acknowledge Bradford Challis, an employee of Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, LLC, for providing writing assistance for the manuscript. Each of us met ICMJE authorship criteria, and no person not named as an author qualified for authorship of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 8 March 2010.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chastre, J., R. Wunderink, P. Prokocimer, M. Lee, K. Kaniga, and I. Friedland. 2008. Efficacy and safety of intravenous infusion of doripenem versus imipenem in ventilator-associated pneumonia: a multicenter, randomized study. Crit. Care Med. 36:1089-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 2006. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; 16th informational supplement, 19087-1898. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA.

- 3.Kattan, J. N., M. V. Villegas, and J. P. Quinn. 2008. New developments in carbapenems. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 14:1102-1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keam, S. J. 2008. Doripenem: a review of its use in the treatment of bacterial infections. Drugs 68:2021-2057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lucasti, C., A. Jasovich, O. Umeh, J. Jiang, K. Kaniga, and I. Friedland. 2008. Efficacy and tolerability of IV doripenem versus meropenem in adults with complicated intra-abdominal infection: a phase III, prospective, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, noninferiority study. Clin. Ther. 30:868-883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mendes, R. E., P. R. Rhomberg, J. M. Bell, J. D. Turnidge, and H. S. Sader. 2009. Doripenem activity tested against a global collection of Enterobacteriaceae, including isolates resistant to other extended-spectrum agents. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 63:415-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Naber, K. G., L. Llorens, K. Kaniga, P. Kotey, D. Hedrich, and R. Redman. 2009. Intravenous doripenem at 500 milligrams versus levofloxacin at 250 milligrams, with an option to switch to oral therapy, for treatment of complicated lower urinary tract infection and pyelonephritis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 53:3782-3792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamura, T., C. Shimizu, M. Kasahara, K. Okuda, C. Nakata, H. Fujimoto, H. Okura, M. Komatsu, K. Shimakawa, N. Sueyoshi, T. Ura, K. Satoh, M. Toyokawa, Y. Wada, T. Orita, T. Kofuku, K. Yamasaki, M. Sakamoto, H. Nishio, S. Kinoshita, and H. Takahashi. 2009. Monte Carlo simulation for evaluation of the efficacy of carbapenems and new quinolones against ESBL-producing Escherichia coli. J. Infect. Chemother. 15:13-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nicolau, D. P. 2008. Carbapenems: a potent class of antibiotics. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 9:23-37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pillar, C. M., M. K. Torres, N. P. Brown, D. Shah, and D. F. Sahm. 2008. In vitro activity of doripenem, a carbapenem for the treatment of challenging infections caused by gram-negative bacteria, against recent clinical isolates from the United States. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 52:4388-4399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pitout, J. D. 2008. Multiresistant Enterobacteriaceae: new threat of an old problem. Expert Rev. Anti Infect. Ther. 6:657-669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pitout, J. D., and K. B. Laupland. 2008. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae: an emerging public-health concern. Lancet Infect. Dis. 8:159-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pitout, J. D., P. Nordmann, K. B. Laupland, and L. Poirel. 2005. Emergence of Enterobacteriaceae producing extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) in the community. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 56:52-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rea-Neto, A., M. Niederman, S. M. Lobo, E. Schroeder, M. Lee, K. Kaniga, N. Ketter, P. Prokocimer, and I. Friedland. 2008. Efficacy and safety of doripenem versus piperacillin/tazobactam in nosocomial pneumonia: a randomized, open-label, multicenter study. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 24:2113-2126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhanel, G. G., R. Wiebe, L. Dilay, K. Thomson, E. Rubinstein, D. J. Hoban, A. M. Noreddin, and J. A. Karlowsky. 2007. Comparative review of the carbapenems. Drugs 67:1027-1052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]