Abstract

Objective

PR (PRDI-BF1 and RIZ) domain proteins (PRDM) are a subfamily of the kruppel-like zinc finger gene products and play key roles during cell differentiation and malignant transformation. PRDM5 (PR domain containing 5 PFM2) is a new PR-domain-containing gene. The purpose of the present study was to examine the expression of PRDM5 and evaluate its carcinogenesis in cervical cancer. The relationship between DNA methylation and transcriptional silencing of PRDM5 was investigated in cervical cancer.

Methods

PRDM5 expression was examined in cervical cancer cell lines and cervical tissues (12 normal and 42 cancerous) by using RT polymerase chain reaction (PCR). Methylation status of the PRDM5 promoter was studied using methylation-specific PCR (MSP).

Results

PRDM5 expression is reduced or lost in cervical cancers, compared with normal cervical tissues (P < 0.05). The current study results also showed that loss of PRDM5 is mediated by aberrant cytosine methylation of the PRDM5 promoter. There were 40.5% of carcinomas methylated, while none of normal tissues were methylated. PRDM5 mRNA expression was significantly higher (P = 0.000) in unmethylated (0.2634 ± 0.0674, mean ± SD), compared with methylated tissues (0.1007 ± 0.0993, mean ± SD). Last, treatment with a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor led to reactivation of PRDM5 expression in cell lines that had negligible PRDM5 expression at baseline.

Conclusions

Reduced expression of PRDM5 may play an important role in the pathogenesis and/or development of cervical cancer, and is considered to be caused in part by aberrant DNA methylation.

Keywords: PRDM5, Cervical cancer, Methylation

Introduction

PR (PRDI-BF1 and RIZ) domain proteins (PRDM) are a subfamily of the kruppel-like zinc finger gene products and play key roles during cell differentiation and malignant transformation. Seventeen family members are known, yet most remain uncharacterized. PRDM1/BLIMP1 was originally identified as a transcript that was rapidly induced during the differentiation of B lymphocytes into immunoglobulin secretory cells; its expression is characteristic of late B and plasma cell lines (Huang 1994; Turner et al. 1994), and it is mutated in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (Pasqualucci et al. 2006). PRDM2/RIZ1 has histone methyltransferase activity (Kim et al. 2003; Huang et al. 1998; Du et al. 2001), and its aberrant methylation has been reported in various types of cancers (Oshimo et al. 2004; Takahashi et al. 2004; Hasegawa et al. 2007; Lal et al. 2006). Both PRDM2 and PRDM1 have growth arrest and proapoptotic activities (He et al. 1998; Jiang et al. 1999; Jiang and Huang 2001; Lin et al. 1997). PRDM5 (PR domain containing 5 PFM2) is a new PR-domain-containing gene. A PRDM5 cDNA was isolated based on its homology to the PR domain of RIZ1 (PRDM2). The gene encodes an open reading frame of 630 amino acids and contains a PR domain in the NH-terminal region followed by 16 zinc finger motifs. Radiation hybrid analysis mapped PRDM5 to human chromosome 4q25-q26, a region thought to harbor tumor suppressor genes for breast, ovarian, liver, lung, colon, and other cancers (Arribas et al. 1999; Chou et al. 1998; Piao et al. 1997; Schwendel et al. 1998; Shivapurkar et al. 1999; Sonoda et al. 1997; Tirkkonen et al. 1997; Wang et al. 1999). The gene has a CpG island promoter and is silenced in human breast, ovarian, and liver cancers. A recombinant adenovirus expressing PRDM5 caused G2/M arrest and apoptosis upon infection of tumor cells (Deng and Huang 2004). These results suggest that PRDM5 is a potential tumor suppressor gene, and transcriptional silencing of this gene may play a role in carcinogenesis.

Epigenetic phenomena such as DNA methylation and alterations in the chromatin structure are increasingly recognized as important mechanisms that are responsible for tumor suppressor inactivation. Recent studies have shown that promoter hypermethylation is an important mechanism in transcriptional silencing of genes during cervical carcinogenesis. Investigations by various authors have demonstrated that expression levels of p16, RASSF1A, DNMT3L, FHIT, COX-2, and DAPK are altered by promoter hypermethylation in cervical cancers (Yu et al. 2003; Gokul et al. 2007; Wu et al. 2006; Jo et al. 2007; Jeong et al. 2006). Promoter hypermethylation has been shown to be associated with reduced PRDM5 expression in solid tumors, such as breast, liver, and gastrointestinal cancers. Treatment with a DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-aza-2′deoxycytidine (5-aza-dC) has been shown to activate PRDM5 mRNA expression in carcinoma cell lines that have reduced PRDM5 expression at baseline (Deng and Huang 2004; Watanabe et al. 2007).

The expression and role of PRDM5 have not been examined in cervical cancers. We hypothesized that loss of PRDM5 expression is important in cervical tumorigenesis and that this is mediated by hypermethylation (which can be inhibited by 5-aza-dC). Because promoter hypermethylation is strongly associated with loss of mRNA expression, we then examine the promoter methylation status of PRDM5 in cervical cancer cells and tissues. Our results show that PRDM5 mRNA expression is reduced or lost in cervical cancer and associated with promoter methylation. These results suggest that epigenetic silencing of PRDM5 (e.g., methylation of its 5-CpG island) plays an important role in the progression of cervical cancer and may be a useful molecular target for diagnosis and therapy.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and tissues

We obtained cancer cell lines from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA). All cell lines were grown in DMEM (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) plus 10% FCS (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 37°C and 5% CO2. Twelve normal cervix and forty-two cervical cancer tissues (two adenocarcinomas and 40 squamous cell carcinomas) were obtained from the Tumor Hospital of Harbin Medical University. The tissues were harvested and frozen in liquid nitrogen at the time of operation. The samples were stored at −70°C until further use. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants.

Drug treatment

Cancer cells (5 × 106 cells) were grown for 4 days in the presence of various concentrations of 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5-aza-dC; Sigma, St. Louis, Mo, USA), a known DNA methyltransferase inhibitor. Total RNA was isolated and used for RT-PCR analysis as described later. Genomic DNAs were isolated from treated and nontreated cells and used for MSP assays as described later.

Reverse transcription and Semi-Quantitative RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cervical tissues and cell lines using TRIzol (Invitrogen Carlsbad, CA). Reverse transcription was performed using M-MLV reverse transcriptase and random oligonucleotide. The first-strand cDNA sample was then amplified using previously published primer sets 5′-GGTGAAAAGTTCGGACCCTT T-3′ and 5′-TGCCCGCTGTTGATTGTCTTC-3′ (Deng and Huang 2004). The primers for amplification of human β-actin are 5′-GTGGGGCGCCCCAGGCACCA-3′ and 5′-CTCCTTAATG TCACGCACG ATTTC-3′. PCR reactions were run for 30 cycles. The PCR products were analyzed by gel electrophoresis followed by ethidium bromide staining.

DNA extraction and methylation analysis

Genomic DNAs from tumor tissues and cell lines were extracted using Universal Genomic DNA Extraction Kit Ver 3.0 (Takara, Tokyo, Japan). The quality and integrity of the DNA was determined by the A260/280 ratios. Genomic DNA (1 μg) was modified with sodium bisulfite using EZ-DNA methylation kit (Zymo research, Orange, Calif). Bisulfite-treated DNA was used for methylation-specific PCR by using previously published primer sets (Deng and Huang 2004) to distinguish between methylated and unmethylated DNA. The PCR products were electrophoresed on a 2% agarose gel.

Statistical Analysis

Gene expression levels are reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD). PRDM5 mRNA expression levels were normal distribution and equal variances, which were compared by using t-Test. The correlation between methylation frequencies and clinicopathological characteristics was compared with the Fisher exact test. All statistical tests were two-sided and performed at the 5% level of significance using the SPSS10.0 software package.

Results

PRDM5 mRNA expression in cervical cancer cell lines and primary tumors

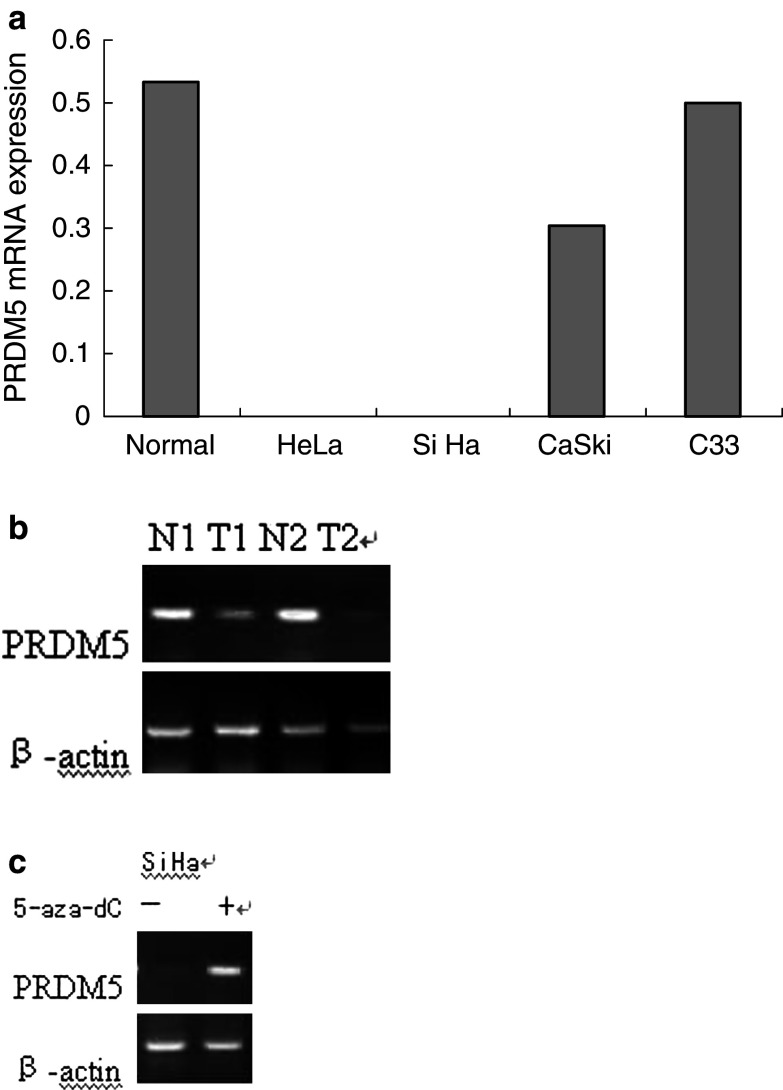

To study the expression of PRDM5 gene in cervical cancer, we performed RT-PCR analysis. PRDM5 expression was reduced or lost in three of four cervical cancer cell lines (Fig. 1a). PRDM5 mRNA expression levels in normal and primary tumor tissues are shown in Fig. 1b and Table 1. PRDM5 mRNA expression in cervical cancer tissues was significantly lower than that in normal tissues (P = 0.000).

Fig. 1.

a PRDM5 mRNA in cervical cancer cell lines relative to normal tissues (n = 12). PRDM5 mRNA expression was absent in two of four cervical cancer cell lines. b PRDM5 mRNA expression in normal tissues (N) and match tumor tissues (T). PRDM5 mRNA expression in cervical cancer tissues was reduced or lost. c Reactivation of PRDM5 expression by inhibitor of DNA methylation in SiHa cells

Table 1.

PRDM5 mRNA expression levels in normal cervical tissues and tumors

| n | Mean | SD | SE | t | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Normal | 12 | 0.5326 | 0.0364 | 0.105 | 0.961 | 0 |

| Malignant | 42 | 0.1976 | 0.1142 | 0.0176 |

SD, standard deviation; SE, standard error

P < 0.05

To determine whether DNA methylation plays a role in silencing PRDM5 gene expression, we investigated whether PRDM5 expression can be activated by 5-aza-dC, an inhibitor of DNA methylation. SiHa cells were treated with 1 uM of 5-aza-dC for 4 days. By RT-PCR analysis, 5-aza-dC treatment reactivated PRDM5 expression (Fig. 1c). This result suggests a probable role of DNA methylation in silencing PRDM5 gene expression.

PRDM5 promoter methylation status in cervical cancer cell lines and primary tumors

As shown in Fig. 2a, methylation of PRDM5 promoter CpG island was found in HeLa and SiHa cancer cells. In contrast, the promoter was unmethylated in C33 cell line, which had retained PRDM5 expression. Both methylated and unmethylated products were observed in the CaSki cell line, which displayed decreased (but detectable) amounts of PRDM5 expression.

Fig. 2.

a Methylation-specific PCR analysis of various cervical cancer cell lines and all of primary tumors and normal tissues. Bisulfite-treated DNA was used as a template for methylation-specific PCR by using previously described primers. M primers specific to methylated template DNA, U primers specific to unmethylated template DNA, T tumor, N normal. b Methylation status of SiHa cell line before and after treatment with the DNA methyltransferase-inhibiting agent, 5-aza-dC

PRDM5 promoter methylation frequency was also examined in normal and primary cervical cancer tissues by methylation-specific PCR. Seventeen of forty-two (40.5%) carcinomas showed evidence of PRDM5 promoter methylation, i.e., a band was detected by using primers specific for the methylated product. Only, unmethylated band was detected in all normal cervical tissues (Fig. 2a). To determine whether transcriptional silencing of PRDM5 is significantly associated with promoter hypermethylation in cervical cancer tissues, we assessed the correlation between methylation status and PRDM5 mRNA expression. PRDM5 mRNA expression was significantly higher (P = 0.000) in unmethylated (0.2634 ± 0.0674, mean ± SD), compared with methylated tissues (0.1007 ± 0.0993, mean ± SD). No significant correlation was detected between methylation status and clinicopathological characteristics, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Correlation between PRDM5 methylation and clinicopathological parameters in cervical cancer

| Factor | Methylationa | |

|---|---|---|

| % (Me/total) | P-value | |

| Tumor size (cm) | ||

| <4 | 38.5 (10/26) | 0.757 |

| ≥4 | 43.8 (7/16) | |

| Tumor grade | ||

| G1 + G2 | 32.0 (8/25) | 0.212 |

| G3 | 52.9 (9/17) | |

| Tumor stage | ||

| I | 46.7 (7/17) | 1.000 |

| II + III | 40.0 (10/25) | |

| Pelvic lymph nodes | ||

| Negative | 34.5 (10/29) | 0.314 |

| Positive | 53.8 (7/13) | |

aSamples that showed partial methylation are included

We also used MSP assay to test whether demethylation might be induced by 5-aza-dC treatment, which may correlate with reactivation of PRDM5 expression in SiHa cell. As shown in Fig. 2b, 5-aza-dC treatment led to an increase in the proportion of unmethylated DNA versus methylated DNA.

Discussion

The protein encoded by PRDM5 is a transcription factor of the PR domain protein family. It contains a PR domain and multiple zinc finger motifs. Transcription factors of the PR domain family are known to be involved in cell differentiation and tumorigenesis. PRDM5 has been reported to possess tumor suppressor activity (Jiang and Huang 2000; Huang 2002; Kim and Huang 2003), and its expression is lost in many carcinoma cell lines and primary tumors (Deng and Huang 2004; Watanabe et al. 2007). In our study, the PRDM5 mRNA expression in cervical cancer tissues was significantly lower than that in normal cervical tissues (P < 0.05) PRDM5 expression was reduced or lost in three of four cervical cancer cell lines. These results suggest that PRDM5 may function as a potential tumor suppressor gene in cervical cancer, as in other malignant tumors.

The PRDM5 promoter has been demonstrated to have the characteristics of a CpG island, which suggests that PRDM5 is a target of inactivation by epigenetic mechanisms. DNA methylation was a common mechanism of gene silencing. Methylation of PRDM5 was detected in 6.6% (4 of 61) of primary colorectal and 50.0% (39 of 78) of primary gastric cancers (Watanabe et al. 2007). Methylation was found for 21 of 40 (53%) breast cancer tissues and 19 of 36 (53%) liver cancer tissues but was not found in three matched normal breast tissues and three matched normal liver tissues (Deng and Huang 2004). In the present study, the PRDM5 mRNA expression was low or undetected in cervical cancer tissues and cell lines. The SiHa cell line was treated with 5-aza-dC (methyltransferase inhibitor), in order to determine whether DNA methylation was the cause of transcriptional silencing of PRDM5. In the SiHa cell line, the mRNA expression of PRDM5 was recovered after treatment with 5-aza-dC, indicating that aberrant DNA methylation is likely to cause transcriptional silencing. Methylation was found in 40.5% (17/42) of cervical cancer tissues and none of normal cervical tissues. The difference reached statistical significance (P < 0.05). Furthermore, in the cervical cancer tissues, the PRDM5 mRNA expression was obviously higher in the unmethylated than that in the methylated (P < 0.05), which suggests that methylation of the PRDM5 promoter may contribute to cervical carcinogenesis. We found no correlation between methylation and any of the clinicopathological characteristics of the patients. Future studies will be required to address whether PRDM5 gene may be involved in the development and metastasis of cervical cancer.

In the present study, the unmethylated form of the PRDM5 promoter was detected in tumor and normal samples. It is not surprising because the samples were not separated using laser-capture microdissection, and thus they can be expected to contain both normal and tumor tissues. Several cases demonstrated relatively low levels of PRDM5 expression in the absence of PRDM5 promoter methylation. We speculate that there may be other mechanisms that are involved in PRDM5 gene silencing. Such mechanisms may include histone methylation, mutations in promoter sequences, and DNA methylation in other promoter regions not covered by our present PCR primer set.

The present results suggest that PRDM5 is a potential tumor suppressor gene and transcriptional silencing of this gene is caused in part by DNA promoter methylation in cervical cancer. Infection with oncogenic HPV is the most significant risk factor in cervical cancer. Transcriptional inactivation of the PRDM5 gene may be induced by oncogenic HPV. The association between the PRDM5 methylation and HPV genotypes will be investigated in the future.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

References

- Arribas R, Risques RA, Gonzalez-Garcia I, Masramon L, Aiza G, Ribas M, Capellà G, Peinado MA (1999) Tracking recurrent quantitative genomic alterations in colorectal cancer: allelic losses in chromosome 4 correlate with tumor aggressiveness. Lab Invest 79(2):111–122 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou YH, Chung KC, Jeng LB et al (1998) Frequent allelic loss on chromosomes 4q and 16q associated with human hepatocellular carcinoma in Taiwan. Cancer Lett 123(1):1–6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Q, Huang S (2004) PRDM5 is silenced in human cancers and has growth suppressive activities. Oncogene 23:4903–4910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y, Carling T, Fang W, Piao Z, Sheu JG, Huang S (2001) Hypermethylation in human cancers of the RIZ1 tumor suppressor gene, a member of a histone/protein methyltransferase superfamily. Cancer Res 61(22):8094–8099 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gokul G, Gautami B, Malathi S, Sowjanya AP, Poli UR, Jain M, Ramakrishna G, Khosla S (2007) DNA methylation profile at the DNMT3L promoter: a potential biomarker for cervical cancer. Epigenetics 2(2):80–85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasegawa Y, Matsubara A, Teishima J, Seki M, Mita K, Usui T, Oue N, Yasui W (2007) DNA methylation of the RIZ1 gene is associated with nuclear accumulation of p53 in prostate cancer. Cancer Sci 98(1):32–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Yu JX, Liu L, Buyse IM, Wang MS, Yang QC, Nakagawara A, Brodeur GM, Shi YE, Huang S (1998) RIZ1, but not the alternative RIZ2 product of the same gene, is underexpressed in breast cancer, and forced RIZ1 expression causes G2-M cell cycle arrest and/or apoptosis. Cancer Res 58(19):4238–4244 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S (1994) Blimp-1 is the murine homolog of the human transcriptional repressor PRDI-BF1. Cell 78:9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S (2002) Histone methyltransferases, diet nutrients and tumour suppressors. Nat Rev Cancer 2(6):469–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang S, Shao G, Liu L (1998) The PR domain of the Rb-binding zinc finger protein RIZ1 is a protein binding interface and is related to the SET domain functioning in chromatin mediated gene expression. J Biol Chem 273:15933–15939 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong DH, Youm MY, Kim YN, Lee KB, Sung MS, Yoon HK, Kim KT (2006) Promoter methylation of p16, DAPK, CDH1, and TIMP-3 genes in cervical cancer: correlation with clinicopathologic characteristics. Int J Gynecol Cancer 16(3):1234–1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang GL, Huang S (2000) The yin-yang of PR-domain family genes in tumorigenesis. Histol Histopathol 15(1):109–117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang GL, Huang S (2001) Adenovirus expressing RIZ1 in tumor suppressor gene therapy of microsatellite-unstable colorectal cancers. Cancer Res 61(5):1796–1798 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang GL, Liu L, Buyse IM, Simon D, Huang S (1999) Decreased RIZ1 expression but not RIZ2 in hepatoma and suppression of hepatoma tumorigenicity by RIZ1. Int J Cancer 83(4):541–547 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo H, Kang S, Kim JW, Kang GH, Park NH, Song YS, Park SY, Kang SB, Lee HP (2007) Hypermethylation of the COX-2 gene is a potential prognostic marker for cervical cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 33(3):236–241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KC, Huang S (2003) Histone methyltransferases in tumor suppression. Cancer Biol Ther 2(5):491–499 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim KC, Geng L, Huang S (2003) Inactivation of a histone methyltransferase by mutations in human cancers. Cancer Res 63:7619–7623 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lal G, Padmanabha L, Smith BJ et al (2006) RIZ1 is epigenetically inactivated by promoter hypermethylation in thyroid carcinoma. Cancer 107(12):2752–2759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Wong K, Calame K (1997) Repression of c-myc transcription by Blimp-1, an inducer of terminal B cell differentiation. Science 276(5312):596–599 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oshimo Y, Oue N, Mitani Y, Mitani Y, Nakayama H, Kitadai Y, Yoshida K, Chayama K, Yasui W (2004) Frequent epigenetic inactivation of RIZ1 by promoter hypermethylation in human gastric carcinoma. Int J Cancer 110(2):212–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasqualucci L, Compagno M, Houldsworth J et al (2006) Inactivation of the PRDM1/BLIMP1 gene in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. J Exp Med 203:311–317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piao Z, Choi Y, Park C et al (1997) Deletion of the M6P/IGF2r gene in primary hepatocellular carcinoma. Cancer Lett 120(1):39–43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwendel A, Richard F, Langreck H, Kaufmann O, Lage H, Winzer KJ, Petersen I, Dietel M (1998) Chromosome alterations in breast carcinomas: frequent involvement of DNA losses including chromosomes 4q and 21q. Br J Cancer 78(6):806–811 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shivapurkar N, Virmani AK, Wistuba II, Milchgrub S, Mackay B, Minna JD, Gazdar AF (1999) Deletions of chromosome 4 at multiple sites are frequent in malignant mesothelioma and small cell lung carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 5(1):17–23 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonoda G, Palazzo J, du Manoir S, Godwin AK, Feder M, Yakushiji M, Testa JR (1997) Comparative genomic hybridization detects frequent overrepresentation of chromosomal material from 3q26, 8q24, and 20q13 in human ovarian carcinomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer 20(4):320–328 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Shivapurkar N, Riquelme E, Shigematsu H, Reddy J, Suzuki M, Miyajima K, Zhou X, Bekele BN, Gazdar AF, Wistuba II (2004) Aberrant promoter hypermethylation of multiple genes in gallbladder carcinoma and chronic cholecystitis. Clin Cancer Res 10(18 Pt 1):6126–6133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tirkkonen M, Johannsson O, Agnarsson BA, Olsson H, Ingvarsson S, Karhu R, Tanner M, Isola J, Barkardottir RB, Borg A, Kallioniemi OP (1997) Distinct somatic genetic changes associated with tumor progression in carriers of BRCA1 and BRCA2 germ-line mutations. Cancer Res 57(7):1222–1227 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner CA Jr, Mack DH, Davis MM (1994) Blimp-1, a novel zinc finger-containing protein that can drive the maturation of B lymphocytes into immunoglobulin-secreting cells. Cell 77:297–306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang XL, Uzawa K, Imai FL, Tanzawa H (1999) Localization of a novel tumor suppressor gene associated with human oral cancer on chromosome 4q25. Oncogene 18(3):823–825 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Toyota M, Kondo Y et al (2007) PRDM5 Identified as a Target of Epigenetic Silencing in Colorectal and Gastric Cancer. Clin Cancer Res 13(16):4786–4794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y, Meng L, Wang H, Xu Q, Wang S, Wu S, Xi L, Zhao Y, Zhou J, Xu G, Lu Y, Ma D (2006) Regulation of DNA methylation on the expression of the FHIT gene contributes to cervical carcinoma cell tumorigenesis. Oncol Rep 16(3):625–629 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu MY, Tong JH, Chan PK, Lee TL, Chan MW, Chan AW, Lo KW, To KF (2003) Hypermethylation of the tumor suppressor gene RASSFIA and frequent concomitant loss of heterozygosity at 3p21 in cervical cancers. Int J Cancer 105(2):204–209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]