Abstract

Pulmonary cystic echinococosis, a zoonosis caused by the larvae of the dog tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus, is considered as a major public health problem in those countries where dogs are used to care for large herds because of the incapacitating effects produced in affected population. The ratio lung:liver involvement is higher in children than in adults. A higher proportion of lung cases are discovered incidentally on a routine x-ray evaluation; the majority of infected people remain asymptomatic until the cyst enlarges sufficiently to cause symptoms. The majority of symptoms are caused by mass effect from the cyst volume; the presence of complications caused by cysts broke changes the clinical presentation; the principal complication is cyst rupture, producing cough, chest pain, hemoptysis, or vomica. Diagnosis is obtained by imaging evaluation (Chest X-ray or CT scan), supported by serology in the majority of cases. Surgery is the main therapeutic approach, having as principal objective, the removal of the parasite, preventing intraoperative dissemination; the use of pre surgical chemotherapy reduces the chances of seeding and recurrence; treatment using benzimidazoles is the preferred treatment when surgery is not available, or complete removal is not feasible

Keywords: Cestodes, tapeworms, cystic echinococcosis, Echinococcus granulosus, immunodiagnosis, surgery

PULMONARY CYSTIC ECHINOCOCCOSIS

Invasion of the human lungs by the larvae of the dog tapeworm Echinococcus granulosus (pulmonary cystic echinococcosis, PCE) is an incapacitating disease frequently found across a wide geographic range involving Europe, Africa, America, Asia, Australia, and Europe.

LIFE CYCLE AND EPIDEMIOLOGY

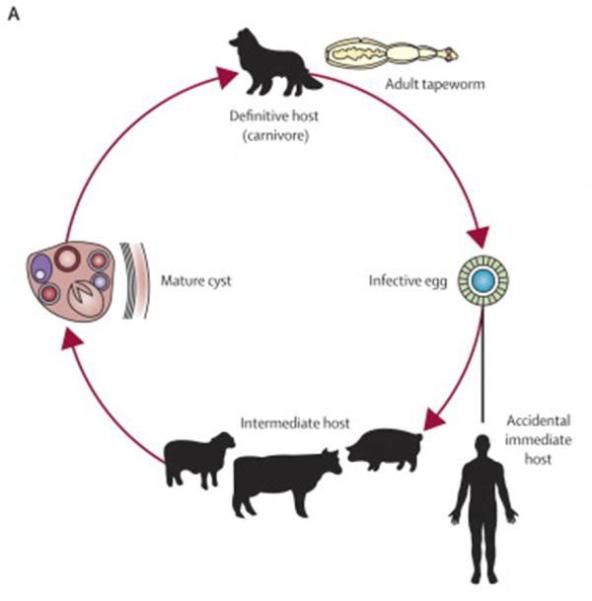

Cystic echinococosis (CE) is a zoonosis produced by the larval stage of the cestode Echinococcus granulosus. In the typical life cycle (figure 1), E. granulosus tapeworms live in the intestine of dogs or other canines (definitive host) and their eggs are passed out with the faeces, disperse widely and can survive for at least one year in the environment. Once ingested by a suitable intermediate host (usually herbivores such as sheep, cattle, goats, pigs, horses or camels), eggs hatch into embryos in the intestine, penetrate the intestinal lining, spread through the blood in the portal circulation, and lodge in tissues, most usually in the liver and lung as major filtering organs. Embryos then transform and develop into cystic metacestodes in which the infective protoscolices will be produced. When cysts in infected viscera are ingested by a dog, protoscoleces attach to the dog’s intestine, developing into mature adult tapeworms in about 40 – 45 days. Humans can act as intermediate hosts if they ingest the eggs, developing large cysts many years after the infection [1-3].

Figure 1.

Life cycle of E. granulosus, adapted from reference 3

CE infection is prevalent in regions of the world where dogs are used to care for large herds. CE infection is widely distributed in South America, the areas bordering the Mediterranean Sea, southern and central Russia, central Asia, Australia, and Africa. In South America, CE is endemic in Peru, Argentina, Chile, southern Brazil and Uruguay [3].

PATHOGENESIS

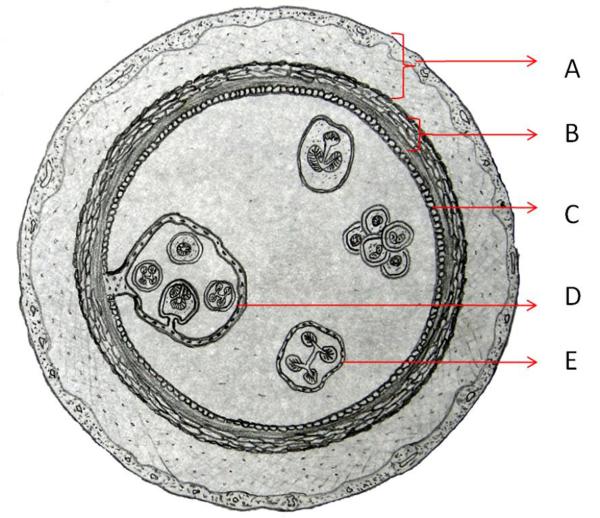

In adult humans, cysts occur more frequently in the liver, followed by the lungs [4]. On the other hand, in children, lung is the predominating site for cyst detection apparently by allowing faster growth of the cyst due to its compressible nature, vascularization, and negative pressure [5]. The majority of lung cysts are primary cyst formed by a filled cavity and comprise three layers: the pericyst, of host origin and consisting of compressed lung tissue with an associated inflammatory host reaction evoked by the parasite and fibrosis; ectocyst (laminated layer, or hyaline membrane); and endocyst (germinal layer). (Figure 2) Protoescolices located on the inner surface of the germinal layer deposit as a sediment (hydatid sand) or form daughter cysts. When cysts rupture, either by spontaneous trauma or during medical intervention, protoscolices contained in the cyst fluid may disseminate, developing secondary cysts in the surrounding tissues [1].

Figure 2.

Scheme of a hydatid cyst: A) pericyst membrane (inflammatory host reaction); B) laminated layer (parasite origin); C) germinal layer; D), E). Daughter cyst.

A high proportion of lung cases may be discovered incidentally on a routine x-ray evaluation. Apparently most individuals harboring small lung cysts often remain asymptomatic five to twenty years after infection until the cyst enlarges sufficiently to cause symptoms[6].

CLINICAL FEATURES

Most symptoms of pulmonary cystic echinococcosis are caused by mass effect from the cyst volume, which exerts pressure on the surrounding tissues. The most common symptoms described by the literature are: cough (53–62%), chest pain (49–91%), dyspnea (10–70%) and hemoptysis (12–21%). Other symptoms described less frequently include dyspnea, malaise, nausea, and vomiting and thoracic deformations [7].The majority of children and adolescents with lung lesions are asymptomatic despite having lesions of impressive size, assumedly because of a weaker immune response and the relatively higher elasticity of the lung parenchyma in children and teenagers [5,8].

Cysts can break or become infected with an aggregated bacterial infection. The presence of any of these complications changes the clinical presentation, either causing new symptoms or increasing the severity of those already existent. The principal complication is cyst rupture; lung cysts may break and cyst material containing fragments of larval tissue and protoscoleces spilled from the ruptured cyst may flow either into bronchial tree producing cough, chest pain, hemoptysis, or vomica; or into the pleural cavity, causing simple or tension pneumothorax, pleural effusion, or empyema. Another important complication is the infection of the cyst, manifesting as a pulmonary abscess with poorly defined margins [9,10].

Lung tissue adjacent tissue adjacent to a cyst is compressed and this may result in atelectasia. Cysts close to the pleural membranes can cause reactive inflammation, secondary bacterial infection, or as above mentioned pleural effusion from the rupture of a cyst. Secondary lesions may develop if cyst contents are spilled to the surrounding tissues, either by natural rupture, expansion and invasion from the lesion or by iatrogenic pleural infestation during surgery [7,10].

DIAGNOSIS

The primary diagnosis is obtained by imaging, with the role of serology mostly limited to case confirmation.

Radiological Diagnosis

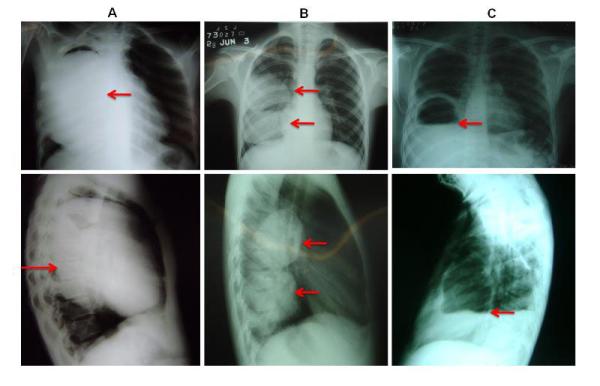

Radiological studies are the primary step in the detection and evaluation of pulmonary CE cysts. By reasons of cost and availability, chest X-rays are still the most used examination. In chest X-rays, cyst are well defined as a rounded mass of uniform density that occupies a part of one or of both hemithorax (figure 3). When a cyst is broken, endocyst detachment is seen as floating membranes within the cyst. This “water-lily” or “meniscus” sign denoting the entrance of air between the laminated membrane and the pericyst through a bronchiopericystic fistula is observed as a thin, radiolucent crescent in the upper part of the cyst on plain radiography (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Posteroanterior and lateral chest X rays showing lung cysts: A) Big cyst that is occupying the majority of right lung; B)Two cysts located in lower and middle lobe of right lung; C) Complicated (broken) cyst located in lower lobe, arrow indicates “camalote” or “water lily” sign ruptured cyst.

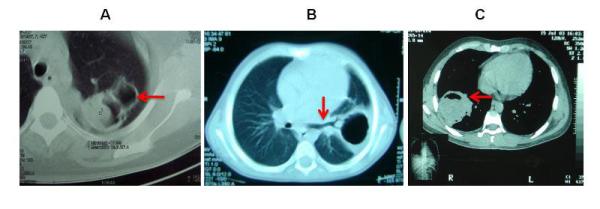

While CT is not required to establish a presumptive diagnosis, it better recognizes certain details of the lesions and their surrounding structures, helping to exclude alternative differential diagnoses (figure 4) and can also uncover additional smaller cysts that were not detected by conventional chest X-ray. The better imaging definition of CT is particularly useful in the case of complicated cysts, for example to identify a cyst wall defect in a ruptured cyst (fig 5). Infected cysts show in CT as poorly defined masses with an increased internal density and contrast enhancement around the cyst wall (ring enhancement sign) after the injection of contrast substance [9,11].

Figure 4.

CT imaging in lung cystic Echinococcosis: A) Complicated cysts located posteriorly in the superior segment of the superior lobe with “mass within a cavity” sign. B) Complicated (broken) cyst located posteriorly in left lung, arrow indicates the communication between cyst cavity and bronchial tree. C) Complicated cyst located in the superior segment of inferior lobe in right lung, arrow indicates the appearance of “mass within a cavity” sign with air and air-fluid level.

The use of ultrasound in lung lesions is quite limited. It may provide good imaging in lesions close to the thoracic wall. Most importantly, however, ultrasound examination of the liver may reveal concomitant liver involvement in up to 15% of individuals with lung CE[7,12].

Serological Diagnosis

Immunodiagnostic tests are used to support the clinical diagnosis of CE. The hydatid larval cysts isolate their contents from the immune system by developing a very thick collagen layer, leading to minimal or nil antigen release and minimal or nil subesquent antibody responses. The principal factor related to a positive serology is the presence or absence of complications (rupture and infection/abscess) because of the release of parasite antigens [13]. Most of the literature describes lower sensitivity of serology in lung CE compared to liver CE, but more recent studies with more sensitive assays seem to find similar proportions of seropositive individuals [14].

TREATMENT

Most patients with lung CE come to be treated after many years of infection and close to 50% of them present with complications, mainly infection. Surgery is the main theraputic approach. Surgical treatment of CE has 2 goals: to safely remove the parasite, preventing intraoperative dissemination and to treat the bronchipericyst pathology and other associated lesions [15-17].

Surgery may involve excision of the cyst or resection of the cyst and the immediate surrounding parenchyma. Despite the lack of consensus, the currently most accepted surgical treatment for lung CE is complete excision using parenchyma-preserving methods, such as cystostomy, intact cyst enucleation or removal after needle aspiration preserving as much lung parenchyma as possible [18,19]. Resection techniques such as pneumonectomy, segmentectomy should be reserved to cysts involving whole hemithorax or the whole segment respectively; and lobectomy should be performed only in large abscessed cysts. To avoid recurrences, the use of pre surgical chemotherapy reduces the chances of seeding and recurrence [10]. Most surgeons use pads soaked in hypertonic saline to protect the operatory field from spillage and subsequent seeding of new cysts.

After removal of the cyst removal, the cavity should be managed by closure of fistulas either by marsupialisation, or by leaving a drain in situ to allow re-expansion of the lung into, and thus cavity obliteration. Available data suggests that marsupialization results in lower frequency o residual abscesses.

WHO guidelines for hydatid disease state that chemotherapy using benzimidazoles is the preferred treatment when surgery is not available, or complete removal is not feasible. Medical treatment can result in reduction of the cyst size. Long courses (several months) of albendazole given at 400 mg twice a day is somewhat efficacious for pulmonary cysts. The related compound mebendazole was initially used but ABZ has better bioavailability [15,20]. A newer benzimidazole compound, oxfendazole, has been studied in animal models and preliminary data suggest it may be more effective [21]. The combination of ABZ and PZQ may provide synergistic effect and better efficacy. Response to chemotherapy is poor in big lesions [22,23]. Side effects benzimidazoles include mild hepatotoxicity, leukopenia, hair loss, and gastric disturbances.

PROGNOSIS

About the prognosis using surgical treatment, it has changed during the last few years, and results are currently commonly satisfactory. The most frequent complications are pleural infection and prolonged air leakage, and Operative mortality rate does not exceed 1% to 2% [10,24].

Recurrence of lung CE is observed in those cases where cyst content was spillage during the surgery; to reduce the number of recurrent cases, it is recommendable the adequate use of scolicidal agents during cyst evacuation in all CE cases, and the concomitant use (pretreatment or post treatment) of benzimidazole compounds in complicated/giant cases[25].

REFERENCES

- 1.Moro P, Schantz PM. Echinococcosis: a review. Int J Infect Dis. 2009;13:125–133. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2008.03.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garcia HH, Moro PL, Schantz PM. Zoonotic helminth infections of humans: echinococcosis, cysticercosis and fascioliasis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2007;20:489–494. doi: 10.1097/QCO.0b013e3282a95e39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Craig PS, McManus DP, Lightowlers MW, et al. Prevention and control of cystic echinococcosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:385–394. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70134-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Siracusano A, Teggi A, Ortona E. Human cystic echinococcosis: old problems and new perspectives. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2009;2009:474368. doi: 10.1155/2009/474368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arroud M, Afifi MA, El Ghazi K, et al. Lung hydatic cysts in children: comparison study between giant and non-giant cysts. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25:37–40. doi: 10.1007/s00383-008-2256-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Torgerson PR, Deplazes P. Echinococcosis: diagnosis and diagnostic interpretation in population studies. Trends Parasitol. 2009;25:164–170. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2008.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arinc S, Kosif A, Ertugrul M, et al. Evaluation of pulmonary hydatid cyst cases. Int J Surg. 2009;7:192–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2008.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dopchiz MC, Elissondo MC, Andresiuk MV, et al. Pediatric hydatidosis in the south-east of the Buenos Aires province, Argentina. Rev Argent Microbiol. 2009;41:105–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Turgut AT, Altinok T, Topcu S, Kosar U. Local complications of hydatid disease involving thoracic cavity: imaging findings. Eur J Radiol. 2009;70:49–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2008.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dziri C, Haouet K, Fingerhut A, Zaouche A. Management of cystic echinococcosis complications and dissemination: where is the evidence? World J Surg. 2009;33:1266–1273. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-9982-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zeyrek D, Savas R, Gulen F, et al. “Air-bubble” signs in the CT diagnosis of perforated pulmonary hydatid cyst: three case reports. Minerva Pediatr. 2008;60:361–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ahmadi NA, Hamidi M. A retrospective analysis of human cystic echinococcosis in Hamedan province, an endemic region of Iran. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 2008;102:603–609. doi: 10.1179/136485908X337517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Santivanez SJ, Sotomayor AE, Vasquez JC, et al. Absence of brain involvement and factors related to positive serology in a prospective series of 61 cases with pulmonary hydatid disease. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:84–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hernandez-Gonzalez A, Muro A, Barrera I, et al. Usefulness of four different Echinococcus granulosus recombinant antigens for serodiagnosis of unilocular hydatid disease (UHD) and postsurgical follow-up of patients treated for UHD. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2008;15:147–153. doi: 10.1128/CVI.00363-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA. Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tatar D, Senol G, Gunes E, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of pulmonary cystic hydatidosis. Indian J Pediatr. 2008;75:1003–1007. doi: 10.1007/s12098-008-0165-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Junghanss T, da Silva AM, Horton J, et al. Clinical management of cystic echinococcosis: state of the art, problems, and perspectives. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;79:301–311. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vasquez JC, Montesinos E, Peralta J, et al. Need for lung resection in patients with intact or ruptured hydatid cysts. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;57:295–302. doi: 10.1055/s-0029-1185604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dakak M, Caylak H, Kavakli K, et al. Parenchyma-saving surgical treatment of giant pulmonary hydatid cysts. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2009;57:165–168. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1039210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stamatakos M, Sargedi C, Stefanaki C, et al. Anthelminthic treatment: an adjuvant therapeutic strategy against Echinococcus granulosus. Parasitol Int. 2009;58:115–120. doi: 10.1016/j.parint.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gavidia CM, Gonzalez AE, Lopera L, et al. Evaluation of nitazoxanide and oxfendazole efficacy against cystic echinococcosis in naturally infected sheep. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2009;80:367–372. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bygott JM, Chiodini PL. Praziquantel: neglected drug? Ineffective treatment? Or therapeutic choice in cystic hydatid disease? Acta Trop. 2009;111:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haralabidis S, Diakou A, Frydas S, et al. Long-term evaluation of patients with hydatidosis treated with albendazole and praziquantel. Int J Immunopathol Pharmacol. 2008;21:429–435. doi: 10.1177/039463200802100223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shehatha J, Alizzi A, Alward M, Konstantinov I. Thoracic hydatid disease; a review of 763 cases. Heart Lung Circ. 2008;17:502–504. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arinc S, Alpay L, Okur E, et al. Recurrent pulmonary hydatid disease: analysis of ten cases. Surg Today. 2008;38:983–986. doi: 10.1007/s00595-008-3759-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]